Всего найдено: 6

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно склонять афганский топоним Сари-Пуль. В словарях его склонения не нашёл, в различных книгах склоняется как по мужскому, так и по женскому роду. Зависит ли склонение от того, какой из одноимённых объектов называется (река, город, район, провинция).

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Рекомендуем не склонять это название, поскольку оно не вполне освоено русским языком: подъехать к Сари-Пуль. Если речь идет о выборе формы определения, следует ориентироваться на род родового слова.

Добрый день, как правильно ставить ударение в имени и фамилии американского писателя афганского происхождения Халеда Хоссейни?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Халед Хоcсейни.

Здравствуйте!

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно: Афганская война или со строчной буквы? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: Афганская война. См.: Лопатин В. В., Нечаева И. В., Чельцова Л. К. Прописная или строчная? Орфографический словарь. М., 2011.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно писать вьетнамская война, афганская война — с прописной или строчной буквы? Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словари фиксируют: вьетнамская война; Афганская война.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите, можно ли оставить в данном предложении строчные буквы:

фильм не об этой войне, и не об а(А)фганской войне, и не о ч(Ч)еченской.

Или все же лучше сделать в обоих случаях прописные буквы?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Афганская война (с прописной), чеченская война (со строчной).

Просим уточнения к ответу № 202683. Подскажите, пожалуйста, каких правил следует придерживатся при написании конкретных военных действий, крисизов, войн. У нас в работе возникают проблемы при написании таких слов. Еще, в частности, как написать — венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис и т.п.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правило таково. В названиях исторических эпох и событий, в том числе войн, с большой буквы пишется первое слово и входящие в состав названия имена собственные. Например: _Семилетняя война, Вторая мировая война, Великая Отечественная война, Крымская война_. Так же пишем с прописной _Карибский кризис_ (как событие, имевшее общемировое значение). Но названия, если можно так выразиться, локальных военных конфликтов последних десятилетий пишутся с маленькой буквы: _корейская война, афганская война_. Корректно: _венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис_.

Тема 1. Выбор прописной/строчной буквы и кавычек в топонимике

Вопрос 1. Два названия театра (выбор прописной или строчной буквы)

Официальное название: Академический русский театр имени Евгения Вахтангова. Следует ли писать далее по тексту «русский театр» с заглавной?

Ответ

1. Современное название (с прописной буквы): Театр имени Евгения Вахтангова. Можно посмотреть: Афиша спектаклей на декабрь 2021, ст. м. Смоленская, г. Москва, Арбат, 26

2. Официальное название: Государственный академический театр имени Евгения Вахтангова (на официальном сайте) https://vakhtangov.ru/

Слово «театр» пишется со строчной буквы.

3. В настоящее время в названии театра нет слова «русский», в том числе в официальном.

Материалы по теме:

(1) Выпуск 21. Раздел 4, тема 2 (5)

Названия, организаций, предприятий и учреждений. Названия, имеющие две формы: полную и усеченную

(2) Академический справочник Лопатина, раздел «Орфография»:

§ 190. С прописной буквы пишется первое (или единственное) слово усеченного названия, если оно употребляется вместо полного, напр.: Государственная дума — Дума, Государственный литературный музей — Литературный музей, Центральный дом художника — Дом художника, Большой зал Московской консерватории — Большой зал Консерватории, Московский государственный институт международных отношений — Институт международных отношений.

Вопрос 2. Афганская война как пишется?

С прописной или строчной? На Грамоте разночтения…

Ответ

Обычно такие наименования пишутся со строчной буквы, но Афганская война — исключение и пишется с прописной.

Источник: Грамота.Ру со ссылкой на словарь-справочник.

Вопрос № 282738 Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно: Афганская война или со строчной буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: Афганская война. См.: Лопатин В. В., Нечаева И. В., Чельцова Л. К. Прописная или строчная? Орфографический словарь. М., 2011.

Комментарий

— А в словаре (или где-нибудь) не написано, почему это исключение?

— На Грамоте есть ранний ответ (очевидно, данный ещё до выхода словаря-справочника), где «афганская» упоминалась в ряду «локальных военных конфликтов последних десятилетий» и писалась со строчной буквы. Да и по Нацкорпусу если посмотреть — преимущественно со строчной буквы, но там источники в основном до 2004 примерно года. Зато много упоминаний Афганской войны в виде «Афган» — именно войны, а не государства (полагаю, можно считать метонимией). Возможно, это и повлияло на рекомендацию писать Афганскую войну с прописной.

Вопрос № 202716 (более ранний ответ)

Просим уточнения к ответу № 202683. Подскажите, пожалуйста, каких правил следует придерживаться при написании конкретных военных действий, кризисов, войн. У нас в работе возникают проблемы при написании таких слов. Еще, в частности, как написать — венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис и т.п.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правило таково. В названиях исторических эпох и событий, в том числе войн, с большой буквы пишется первое слово и входящие в состав названия имена собственные. Например: Семилетняя война, Вторая мировая война, Великая Отечественная война, Крымская война. Так же пишем с прописной Карибский кризис (как событие, имевшее общемировое значение). Но названия, если можно так выразиться, локальных военных конфликтов последних десятилетий пишутся с маленькой буквы: корейская война, афганская война. Корректно: венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис.

Сравнить: Раздел 5, тема 3.

В советское время писали гражданская война 1918-1920, сейчас первое слово пишется с прописной буквы, как конкретное историческое событие, имеющее индивидуальное название, например: Весной 1920 года Гражданская война в России казалась почти законченной.

Вопрос 3. Кавычки в названиях космодромов

Почему названия космодромов не берутся в кавычки? Ни «Роскосмос», ни «Грамота.ру» не пишут «Байконур» в кавычках, они везде пишут так: Космодром Байконур

Есть какое-то правило или исключение, зафиксированное словарями?

Ответ

Вопрос № 205174. Подскажите, пожалуйста, нужно ли брать в кавычки название космодрома Байконур?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка. Кавычки не нужны.

Вопрос № 279037. Подскажите пожалуйста, как следует писать название космодрома Восточный – в кавычках или без?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка. Верно без кавычек.

Вопрос № 283365 (дополнительно о склонении названия)

Подскажите пожалуйста, склоняется ли слово «Байконур» в словосочетаниях, употребляемых без кавычек: администрация города Байконур, подъезжать к городу Байконур и т.д. При это думаю следует учитывать, что название администрации города Байконур не склоняется в международном документе, согласно которому определены её полномочия (от 23.12.1995), а также с учетом общего правила, что склоняются только географические названия, представляющие собой давно заимствованные и освоенные наименования, коим Байконур по моему мнению не является. Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка. В сочетании город Байконур имя собственное склоняется: администрация города Байконура, подъезжать к городу Байконуру. Ср.: на космодроме Байконур, к космодрому Байконур.

Версия причины отсутствия кавычек такая. Без кавычек пишутся географические, астрономические и др.названия, а вот названия космодромов могли бы проходить как названия предприятий и фирм, где используются кавычки, например: московская швейная фабрика «Салют». Но космодром – это нечто среднее между географическим объектом и предприятием, тем более что географическое название для космодрома является исходным.

Но вот статья 2021 года ru.rbth.com/read/1813-russian-cosmodromes-space В названиях статей кавычек нет, а самих статьях названия космодромов в кавычках встречаются. Чем это объяснить? Можно предположить, что это некорректное решение.

Вопрос 4. С какой буквы писать слово «империя» или «королевство» в художественной литературе?

Я знаю, что официальные названия стран, которые существуют на сегодняшний день, пишутся с большой буквы: «Королевство Таиланд», «Королевство Дания» и т.д.

Но как писать эти слова, например, в вымышленном фэнтези-мире? В «Ведьмаке» Сапковского слово «империя» в русском переводе почему-то пишется с маленькой буквы (Нильфгаардская империя), хотя речь идёт про существующую империю. То же самое с королевствами: «королевство Реданское«.

Или эти правила касаются только реального мира? Как правильно писать в данных примерах?

Мы знаем, где находится Королевство Батут.

Мы знаем, где находится Сирская Империя.

Мы знаем, где находится Королевство Урское.

Ответ

Существительные «королевство», «империя» являются нарицательными (написание со строчной буквы), но могут входить в составные имена собственные и писаться с прописной буквы.

В реальности все слова в официальных названиях пишутся с прописной буквы, в других же случаях — только первое слово (например, Римская империя).

В мире фэнтези могут действовать такие же правила, хотя там, как мне кажется, чаще встречаются варианты с прописными буквами: Королевство Батут, Сирская Империя, Королевство Урское.

Написание «Нильфгаардская империя» возможно, это выбор автора, но вариант «королевство Реданское» лучше писать как «Королевство Реданское«, так как нарицательное существительное стоит на первом месте.

Вопрос 5. Почему Роспотребнадзор пишется без кавычек?

Почему Роспотребнадзор (Ростех, Роскомнадзор и т. д.) пишется без кавычек?

Ответ

1. Употребление кавычек при таких наименованиях определяется влиянием сразу трех факторов: типа аббревиатуры, семантики названия и наличия/отсутствия при названии родового слова.

Как правильно употреблять кавычки в аббревиатурных названиях http://new.gramota.ru/spravka/letters/76-kav3

В статье приводится подробная информация по конкретным названиям.

2. Федеральная служба по надзору в сфере защиты прав потребителей и благополучия человека (Роспотребнадзор)

Не заключаются в кавычки сокращенные наименования органов законодательной и исполнительной ВЛАСТИ (министерств, федеральных агентств, федеральных служб, комитетов и др.), например: Госдума, Мосгордума, Рособрнадзор, Центризбирком, Россотрудничество, Минэкономразвития, Москомнаследие.

Наименования государственных предприятий, учреждений, корпораций, акционерных обществ, а также крупнейших банков при употреблении без родового слова испытывают колебания: Рособоронэкспорт и «Рособоронэкспорт», Роскосмос и «Роскосмос»…

3. Аббревиатуры инициального типа, представляющие собой сокращение условного наименования, заключаемого в кавычки, последовательно пишутся в кавычках только при наличии родового слова: ОАО «РЖД» (ОАО «Российские железные дороги»).

Вопрос 6. Строчная или прописная?

Все-таки со строчной или прописной следует писать слово «филиал» в предложении «Справка Ф(ф)илиала Центрального архива Министерства обороны РФ (военно-медицинских документов)«? В работах историков мне встречаются оба варианта написания.

Ответ

Можно предположить, что в данном случае правильным будет написание с прописной буквы: Филиал Центрального архива Министерства обороны РФ (военно-медицинских документов). Дело в том, что такой филиал (военно-медицинских документов) только один.

А вот территориальных филиалов много, поэтому там больше подходит строчная буква, например: Адрес филиала Центрального архива Министерства Обороны РФ=ЦАМО в г. Пугачев: 413700, Саратовская область, г. Пугачев, в/ч 61220.

Пояснение (как применяется правило выбора буквы)

1. Если такой филиал единственный, то в состав имени собственного входит слово «филиал» и пишется с прописной буквы как первое слово названия.

2. Если филиалов с точно таким названием много, то следует считать слово «филиал» нарицательным и писать со строчной буквы, что обычно и делается в тексте (в справках, например).

Прописная буква пишется только в качестве начальной (в предложении, в перечне и т. д.).

3. Откуда берутся варианты письма? Статус документов (записей) может быть разный. В таких ситуациях специалист в конкретной области может иногда лучше сориентироваться, если он понимает разницу между нарицательными и собственными именами.

Также надо видеть официальное название конкретного учреждения. Не очень логично включать адрес в такое официальное название, но не учитывать такой вариант тоже нельзя.

https://otvet.mail.ru/question/40646719

Вопрос 7. Строчная или прописная?

«…грудь полковника украшал Рыцарский крест с дубовыми листьями...»

Награда — Рыцарский крест. С прописной буквы?

Ответ

Я думаю, что здесь нужно ориентироваться вот на это правило.

Названия орденов, медалей, наград, знаков отличия, не сочетающиеся синтаксически с родовым наименованием, заключаются в кавычки и в них пишутся с прописной буквы первое слово и собственные имена, напр.: орден «Мать-героиня», орден «За заслуги перед Отечеством»…

Все прочие названия наград и знаков отличия кавычками не выделяются и в них пишется с прописной буквы первое слово (кроме слов орден, медаль) и собственные имена, например: орден Дружбы, орден Отечественной войны I степени, орден Почетного легиона (Франция), орден Андрея Первозванного, орден Святого Георгия, медаль Материнства, Георгиевский крест; Государственная премия, Нобелевская премия.

Названия орденов, медалей, наград, знаков отличия (Лопатин)

Названия орденов и медалей (Розенталь)

Он сделал ещё одну попытку доказать свою правоту и получил высший орден Империи — Рыцарский крест с дубовыми листьями. [Василий Гроссман. Жизнь и судьба, часть 3 (1960)]

Вопрос 8. «Парад тюльпанов в ботсаду»

С большой буквы слово «парад»? Конкретный парад в Ялте. А парад цветов? Просто, без привязки к месту.

Ответ

Пишут по-разному, например:

В Никитском ботаническом саду открылось красочное мероприятие – 15-й по счёту парад тюльпанов. Сейчас в Никитском ботсаду в Ялте идет Парад тюльпанов. В Никитском ботсаду в Крыму стартовал «Парад тюльпанов«.

В принципе допустимы все варианты, но в разных ситуациях.

Парады тюльпанов проводятся в различных городах и странах, и тогда это нарицательное сочетание – парад тюльпанов.

Выражение 15-й по счёту парад тюльпанов тоже верно, здесь также нарицательный смысл.

Когда речь идет о конкретном мероприятии в данном городе и там уже есть определенные традиции и правила, то можно считать название праздника именем собственным.

Разные записи (с кавычками и без них) – это скорее авторский выбор. Парад тюльпанов – можно без кавычек, но чем длиннее название, тем кавычки уместнее: Парад тюльпанов, «Парад тюльпанов в ботсаду».

Вопрос 9. Написание названий покера

Лингвисты и картёжники, у меня вопрос в написании названий покера. О/омаха, Т/техасский Х/холдеми и Д/дро… Как вообще будет писаться? Нужны ли кавычки или дефис? Как будет правильно: «О/омаха(-)покер» и «Д/дро(-)покер»?

Ответ

Возможные варианты: Омаха, Омаха-покер, Техасский холдем, Дро-покер.

Написание в кавычках допускается, но используется нечасто. Родовое слово «покер» (приложение) ставится на второе место и пишется через дефис. В этом случае кавычки не используются: Омаха-покер, «Омаха», «Омаха-холдем».

Пояснение

В правописании составных имен собственных можно выделить тематическую группу названий, где возможны колебания в выборе формы письма. Сюда относятся некоторые топонимические имена, а также названия предметов (орденов и медалей, бытовой и промышленной техники, растений и животных, вин, продуктов и др). В эту же группу можно отнести и названия карточных игр.

Характерной особенностью этой группы является наличие вариантов письма:

Форма 1. Прописная буква, без кавычек (в специальной литературе).

Форма 2. Прописная буква с кавычками.

Форма 3. Строчная буква с кавычками.

Форма 4. Строчная буква без кавычек.

Форма 3 и форма 4 фактически относятся к нарицательным существительным. Наличие кавычек в форме 3 говорит о том, что данное слово не является общеизвестным термином.

Эти группы можно рассмотреть на примере названий для вина.

Форма 1: Десертное вино Цинандали. Форма 2. Вино «Солнечная долина», «Бычья кровь». Форма 3. «Бордо», «Бургундское». Форма 4. Кагор, мадера,

2. Эта же система просматривается в названии карточных игр. Если почитать литературу на эту тему, то видно, что варианты с прописными и строчными буквами могут быть разными. Слово «покер» это нарицательное существительное, но названия покеров могут считаться как именами собственными, так и нарицательными, причем разные написания иногда встречаются в одной статье.

В более официальных названиях первое слово пишется с прописной буквы, но эти же названия могут писаться со строчной буквы как нарицательные имена, и это будет авторский выбором.

Примеры предложений:

Техасский холдем (или просто холдем) – самая популярная разновидность спортивного покера в Северной Америке и Европе.

Дро-покер – это любой вариант покера, в котором каждый игрок получает полную руку перед первым раундом ставок, а затем развивает руку для последующих раундов, заменяя или «вытягивая» карты.

«Омаха» или «Омаха холдем» (англ. Omaha, Omaha hold ’em) – один из самых популярных видов покера. В отличие от семикарточного «техасского холдема», эта игра — 9-карточная.

Тема 2. Склонение имен собственных

Вопрос 1. Как склонять двойные мусульманские имена?

Встреча с председателем Международной исламской благотворительной организации Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матууком.

Как склонять такое имя: (1) Абдуллахом Матууком; (2Абдуллахом Матуук (3) Абдуллах Матуук. В каком справочнике дается ответ на этот вопрос?

Как-то на сайте «Корректор» было такое:

Друзья, склоняется ли первая часть имени Нур Мухаммед Тараки? Нур Мухаммеда Тараки или Нура Мухаммеда Тараки?

Мусульманские двойные имена обычно склоняют как единое имя. (Что это значит?)

Нет, склонять не надо. Это каприз орфографии, такие двойные имена раньше писали слитно.

Вопрос № 202995

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно написать на конверте следующие иностранные имена в дательном падеже (кому): Хассан Ахмад Хаммуда Рольф Карл Тео Деега Субрамония Айер Нарайанан Саад Кхалид Ахмад Манфред Франц Вильтнер.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка.

Корректно: _Хассану Ахмаду Хаммуде, Рольфу Карлу Тео Дееге, Субрамонии Айеру Нарайанану, Сааду Кхалиду Ахмаду, Манфреду Францу Вильтнеру.

Ответ 1

Если мне память не изменяет, то «Нур» — это не имя как таковое, а префикс-титул, поэтому он может не склоняться.

Кроме того, в разговорной речи односложные даже истинные имена имеют стойкую тенденцию не склоняться, если это имя известного лица, тесно связанное с фамилией («читал Жюль Верна«).

Поэтому рекомендация не склонять «Нур» объяснима, хотя и спорна. Но обобщать на имена типа Абдуллы никак нельзя.

Ответ 2

Увы, правил не приведу, лишь поясню данный Вами же ответ. Мусульманские двойные имена обычно склоняют как единое имя (т.е. меняется только окончание последней части имени/фамилии):

им.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матуук

род.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матуука

дат.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матууку

вин.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матуука

тв.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матууком

пр.п. — Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матууке

Да, если сомневаетесь, всегда можно построить предложение так, чтобы не приходилось склонять имя. Получается немного косноязычно, но точно не ошибетесь (часто использую при общении непосредственно с человеком, чтобы не дай Бог не оскорбить): На встрече, где присутствовал председатель Абдуллах Матуук Аль-Матуук, (…)

Комментарии

– Я не согласен. А на основании чего мусульманским именам надо предоставлять какое-то исключение?

– Имена собственные вообще очень сложно поддаются описанию правилами, насколько я помню из школьного курса. И с большим количеством исключений. Вот здесь про «восточные» имена: 5.2. В составных именах и фамилиях вьетнамских, корейских, китайских и др. склоняется последняя часть. Почему? Есть вполне осмысленный исчерпывающий набор правил. О нем спорят, обсуждают и корректируют… Но он есть. Просто не надо ограничиваться школьными знаниями.

Источники

http://www.gramota.ru/slovari/info/ag/sklon/

http://www.gramota.ru/class/istiny/istiny_8_familii/

Вопрос 2. Написать в родительном падеже:

Федерального государственного бюджетного учреждения профессиональная образовательная организация «ГУОР»?

Как написать в родительном падеже название: директор Федерального государственного бюджетного учреждения профессиональная образовательная организация «Государственное училище (техникум) олимпийского резерва»? Или директор Федерального государственного бюджетного учреждения профессиональной образовательной организации «Государственное училище (техникум) олимпийского резерва»?

Ответ

Я думаю, что верно так:

…директор Федерального государственного бюджетного учреждения профессиональной образовательной организации «Государственное училище (техникум) олимпийского резерва»

В этом случае имя собственное делится на две тематические группы (название по виду собственности и основное название по виду деятельности).

Основное название, заключенное в кавычки, не склоняется.

Первая же часть состоит их двух неоднородных названий, поэтому надо склонять обе части на равных основаниях.

Вопрос 3. Склонение топонима Адлер

«Крымскую столицу с краснодарским курортом Адлер(-ом) связал пассажирский поезд». Стоит ли склонять Адлер?

Ответ

Крымскую столицу с краснодарским курортом Адлером связал пассажирский поезд.

Географическое название, употребленное с родовыми наименованиями город, село, деревня, хутор, река и др., выступающее в функции приложения, согласуется с определяемым словом, то есть склоняется, если топоним русского, славянского происхождения или представляет собой давно заимствованное и освоенное наименование.

http://new.gramota.ru/spravka/letters?id=73

Адлер – известный курорт, его часто называют городом. Также при склонении название согласуется как с родовым словом, так и с отнесенным к нему определением.

Вопрос 10. Строчная или прописная (где пролегает грань между прозвищем, обзывательством и сравнением)

Существует правило, что имена, прозвища, клички, позывные, псевдонимы и т. п. пишутся с прописной буквы (в составных — соответственно все слова, кроме служебных, а-ля: Чучело; Чёрный Мечник; Тот, Кого Нельзя Называть и пр.). Но как отличить прозвище от обзывательства (то же Чучело) и сравнения, которые пишутся со строчной? Неужто на всё воля автора? А если переводим текст, например с корейского или японского, где вообще нет прописных букв? Сами решаем?

Скажем, в романе один человек постоянно называет другого пингвином: «О, пингвин наш идёт», «Ну ты и пингвин!»… Это прозвище, которое следует писать с большой буквы? А если бы он называл его дураком: «О, дурак наш идёт», «Ну ты и дурак!»… Теоретически же и «пингвин», и «дурак» могут являться ругательствами, которые просто часто повторяются в отношении одного человека. Но не будем же мы считать «дурака» за прозвище и писать с прописной? Причём «пингвин» ещё может считаться сравнением с животным (такой же тучный, неповоротливый и с короткой шеей) вроде «Ах ты лиса какая!», «Знаю я этого тюленя»…

Как же тогда принимать решение, считать подобное прозвищем и писать с прописной буквы (Пингвин) или же считать периодически повторяющимся ругательством/сравнением и писать со строчной (пингвин)? Могу лишь предположить, что эта грань порой настолько тонка, что редактор сам решает, как поступить в конкретном случае, ориентируясь на особенности

Ответ

С прописной буквы пишутся только прозвища, которые фактически заменяют имена (автор обычно называет настоящее имя героя, но в дальнейшем его редко употребляет). Все другие персонажи также используют прозвище в качестве имени собственного (в том числе обращаясь к нему, но не во всех случаях).

Все остальное — это нарицательные слова (как дразнилки, так и любые сравнения). Вот недавно мне попалась такая строка: «А эти тупые бакланы на звёзды смотреть не велят». Посмотрела информацию о бакланах — вроде бы их считают крикливыми, прожорливыми и не очень умными птицами. Хороший вариант для прозвища.

А это подходящая статья на тему «Прозвища героев художественных произведений». https://vuzlit.com/868351/prozvischa_geroev_hudozhestvennyh_proizvedeniy

У Платонова главного героя все звали Юшкой (а это тоже прозвище, а не имя).

Всего найдено: 29

С большой или маленькой буквы пишется «Гражданская война«?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: гражданская война (как родовое название, определяющее характер войны) и Гражданская война (в России 1918-1920, в США 1861-1865).

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста с какой буквы пишется «в/Вторая п/Пуническая война» — заглавной или прописной? Я нашла в энциклопедиях разные варианты (например БСЭ и Брокгауза и Эфрона).

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Вторая Пуническая война (см.: В. В. Лопатин, И. В. Нечаева, Л. К. Чельцова. Прописная или строчная? Орфографический словарь. М., 2007). Обратите внимание: заглавная и прописная буква – это одно и то же (большая буква). Маленькая буква называется строчной.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно писать вьетнамская война, афганская война — с прописной или строчной буквы? Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словари фиксируют: вьетнамская война; Афганская война.

Как правильно писать Пелопонесские войны

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Исторический термин: Пелопоннесская война.

Прописная или строчная: ближнее зарубежье, гражданская война, Великая отечественная война?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: ближнее зарубежье, Великая Отечественная война. Сочетание гражданская война пишется строчными как родовое название, определяющее характер войны. Однако как обозначение исторического события правильно: Гражданская война (в России 1918–1920; в США 1861–1865).

Еще раз с днем рождения!!!

Вопрос такой. со строчной или прописной буквы пишется Гражданская война? Я всегда думала, что со строчной, но недавно у вас (в одном из ответов) видела ее с прописной. Как правильно?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Спасибо!

Сочетание гражданская война пишется строчными как родовое название, определяющее характер войны. Однако как обозначение исторического события правильно: Гражданская война (в России 1918–1920; в США 1861–1865).

Здравствуйте! Нужна ваша помощь: меня интересует с какой буквы пишется название советско-финской и советско-японской войн, со строчной или с прописной? Контекст простой: И. И. Иванов участник советско-финской войны.

На какое правило можно ссылаться? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Советско-финляндская война (такой вариант фиксирует БСЭ). Что касается боевых действий против Японии, проводившихся в 1945 г., то они входили в число операций Второй мировой войны и не могут рассматриваться в качестве отдельного вооруженного конфликта.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите, можно ли оставить в данном предложении строчные буквы:

фильм не об этой войне, и не об а(А)фганской войне, и не о ч(Ч)еченской.

Или все же лучше сделать в обоих случаях прописные буквы?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Афганская война (с прописной), чеченская война (со строчной).

во время Гражданской войны …

Может ли все-таки гражданская война писаться с большой буквы, если имеется ввиду конкретная 1917-1923гг. ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, это сочетание пишется с прописной (большой) буквы.

Здравствуйте, уважаемая «Грамота»!

Срочно нужна ваша помощь! Подскажите, пожалуйста, правильно ли писать Вторая Пуническая война? Меня в частности интересуют прописные буквы в начале слов Вторая и Пуническая.

Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: _Вторая Пуническая война_.

Ответьте, пожалуйста, как называлась Финская кампания 1939-1940 гг. в советских учебниках истории. Очень-очень нужно!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Возможно, _советско-финская война_.

Какие из названий исторических событий пишутся с заглавной буквы и почему? Много разночтений.

— первая мировая война

— вторая мировая война

— гражданская война

— Русско-японская война

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Первая мировая война, Вторая мировая война, Гражданская война_ (в России 1918—1920; в США 1861—1865). В остальных случаях (как родовое название, определяющее характер войны) — _гражданская война; Русско-японская война_ (1904 — 1905).

Просим уточнения к ответу № 202683. Подскажите, пожалуйста, каких правил следует придерживатся при написании конкретных военных действий, крисизов, войн. У нас в работе возникают проблемы при написании таких слов. Еще, в частности, как написать — венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис и т.п.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правило таково. В названиях исторических эпох и событий, в том числе войн, с большой буквы пишется первое слово и входящие в состав названия имена собственные. Например: _Семилетняя война, Вторая мировая война, Великая Отечественная война, Крымская война_. Так же пишем с прописной _Карибский кризис_ (как событие, имевшее общемировое значение). Но названия, если можно так выразиться, локальных военных конфликтов последних десятилетий пишутся с маленькой буквы: _корейская война, афганская война_. Корректно: _венгерский кризис, чехословацкий кризис_.

Поскажите, пожалуйста, с какой буквы — прописной или строчно, надо писать карибский кризис 1962 г., ливанская война 1982 г., корейская война 1950-1953 гг., если речь идет о конкретной войне и они употребляются без дат?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Карибский кризис, корейская война, ливанская война_.

Афганская война — (Afgan War) После военного переворота в Афганистане в апреле 1978 г. к власти пришла прокоммунистическая Народно демократическая партия, раздираемая фракционными разногласиями. В декабре 1979 г. во внутренние дела страны вмешался СССР,… … Политология. Словарь.

АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА — АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА, гражданская война в Афганистане 1979 2001 гг., проходившая в условиях интервенции СССР. США, Пакистана и других стран. Кризис просоветского режима Кризис полуфеодального государства в Афганистане привел к нарастанию политических… … Энциклопедический словарь

Афганская война (значения) — «Афганская война» российский сериал (премьера в 2009 м году). Война в Афганистане Список значений слова или словосочетания со ссылками на соотве … Википедия

АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА 1979-89 — АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА 1979 89, военные действия советских войск в Афганистане. Ввод в страну т. н. ограниченного контингента советских войск (ОКСВ; 25 декабря 1979) мотивировался необходимостью оказания помощи в отражении внешней агрессии на основании… … Русская история

Афганская война (1979—1989) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Афганская война (значения). Афганская война (1979 1989) … Википедия

Афганская война (фильм) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Афганская война (значения). Для улучшения этой статьи желательно?: Обновить статью, актуализировать данные … Википедия

Афганская война — (Afghan War) Конфликт между мусульм. афган. партизанами с одной стороны и правительственными и советскими (с 1979) войсками, стремившимися сохранить комм. режим в Афганистане, с другой. После переворота в апр. 1978 левые военные передали власть… … Энциклопедия битв мировой истории

афганская война — (1979–1989) … Орфографический словарь русского языка

Первая англо-афганская война — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Англо афганские войны … Википедия

Вторая англо-афганская война — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Англо афганские войны … Википедия

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

афга́нский, (к афга́нцы и Афганиста́н)

Рядом по алфавиту:

афа́ги́я , -и

афа́зи́я , -и

афа́ки́я , -и

афали́на , -ы

афана́сьевский , (от Афана́сий и Афана́сьев; афана́сьевская культу́ра, археол.)

афанизи́я , -и

афа́тик , -а

афати́ческий

афга́н , -а (порода собак, сниж.)

Афга́н , -а (сниж. к Афганиста́н; о войне 1979–1989 в Афганистане)

афга́нец , -нца (ветер)

афгани́ , нескл., ж. и с. (ден. ед.)

афга́нка , -и, р. мн. -нок

афга́но-пакиста́нский

афга́но-таджи́кский

афга́нский , (к афга́нцы и Афганиста́н)

афга́нско-росси́йский

афга́нско-сове́тский

афга́нцы , -ев, ед. -нец, -нца, тв. -нцем

афедрона́льный

афе́лий , -я

афели́нус , -а

афе́ра , -ы

афери́ст , -а

афери́стка , -и, р. мн. -ток

афери́стский

афилли́я , -и

афиллофо́ровые , -ых

Афи́на , -ы (мифол.)

Афи́на Палла́да , Афи́ны Палла́ды

афи́нский , (от Афи́ны)

афга́нский

афга́нский (к афга́нцы и Афганиста́н)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова неканоничный:

Предложения со словом «афганский»

- Во время афганской войны SSG занимались в том числе и подготовкой боевиков.

- Начиная с 1955 г. советское вооружение и боевая техника стали достоянием афганской армии, а советские специалисты и советники – надёжными помощниками афганцев в деле их освоения.

- Я напротив, рассказываю об интернациональном долге и помощи афганскому народу.

- (все предложения)

Что (кто) бывает «афганским»

Основная статья: Афганская война (1979—1989)

В этой категории собираются все понятия, связанные с присутствием на территории Афганистана ограниченного контингента советских войск с 1979 по 1989 годы.

×òî òàêîå «Àôãàíñêàÿ âîéíà»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

Àôãàíñêàÿ âîéíà

ÀÔÃÀÍÑÊÀß ÂÎÉÍÀ

(Afgan War) Ïîñëå âîåííîãî ïåðåâîðîòà â Àôãàíèñòàíå â àïðåëå 1978 ã. ê âëàñòè ïðèøëà ïðîêîììóíèñòè÷åñêàÿ Íàðîäíî-äåìîêðàòè÷åñêàÿ ïàðòèÿ, ðàçäèðàåìàÿ ôðàêöèîííûìè ðàçíîãëàñèÿìè.  äåêàáðå 1979 ã. âî âíóòðåííèå äåëà ñòðàíû âìåøàëñÿ ÑÑÑÐ, ïîääåðæàâøèé Áàáðàêà Êàðìàëÿ, ïîçäíåå ïðîâîçãëàøåííîãî ïðåçèäåíòîì. Çàòåì ïîñëåäîâàëî âîåííîå ñòîëêíîâåíèå ìåæäó àôãàíñêîé àðìèåé è îïïîçèöèîííûìè ñèëàìè ìîäæàõåäîâ, ñðåäè êîòîðûõ òàêæå íå áûëî åäèíñòâà. ÑÑÑÐ ââåë â ñòðàíó ìíîãîòûñÿ÷íóþ ãðóïïèðîâêó âîéñê. Îäíàêî ýòî íå ñòàáèëèçèðîâàëî íîâûé êîììóíèñòè÷åñêèé ðåæèì è íå îáåñïå÷èëî áåçîïàñíîñòè çà ïðåäåëàìè áëèçëåæàùèõ ê Êàáóëó òåððèòîðèé. Ñîâåòñêîå âîåííîå âìåøàòåëüñòâî â äåëà Àôãàíèñòàíà ñòàëî ãëàâíîé ïðè÷èíîé êîíöà ïåðèîäà ðàçðÿäêè è óõóäøåíèÿ â ïåðâîé ïîëîâèíå 1980-õ ãã. îòíîøåíèé ìåæäó Ìîñêâîé è Âàøèíãòîíîì. Áîëüøèå ïîòåðè ÑÑÑÐ â ýòîé âîéíå îêàçàëè î÷åíü ñåðüåçíîå âëèÿíèå íà åãî âíóòðåííþþ ïîëèòèêó. Ïîñëå èçáðàíèÿ â ìàðòå 1985 ã. Ãåíåðàëüíûì ñåêðåòàðåì ÊÏÑÑ Ìèõàèëà Ãîðáà÷åâà, îáúÿâèâøåãî êóðñ «íîâîãî ïîëèòè÷åñêîãî ìûøëåíèÿ», ÑÑÑÐ íà÷àë ïîýòàïíûé âûâîä ñâîèõ âîéñê èç Àôãàíèñòàíà, çàâåðøèâøèéñÿ â 1989 ã. Àôãàíñêèé êîììóíèñòè÷åñêèé ðåæèì ïàë â 1992 ã.

афганская война

- афганская война

-

(1979–1989)

Орфографический словарь русского языка.

2006.

Смотреть что такое «афганская война» в других словарях:

-

Афганская война — (Afgan War) После военного переворота в Афганистане в апреле 1978 г. к власти пришла прокоммунистическая Народно демократическая партия, раздираемая фракционными разногласиями. В декабре 1979 г. во внутренние дела страны вмешался СССР,… … Политология. Словарь.

-

АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА — АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА, гражданская война в Афганистане 1979 2001 гг., проходившая в условиях интервенции СССР. США, Пакистана и других стран. Кризис просоветского режима Кризис полуфеодального государства в Афганистане привел к нарастанию политических… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Афганская война (значения) — «Афганская война» российский сериал (премьера в 2009 м году). Война в Афганистане Список значений слова или словосочетания со ссылками на соотве … Википедия

-

АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА 1979-89 — АФГАНСКАЯ ВОЙНА 1979 89, военные действия советских войск в Афганистане. Ввод в страну т. н. ограниченного контингента советских войск (ОКСВ; 25 декабря 1979) мотивировался необходимостью оказания помощи в отражении внешней агрессии на основании… … Русская история

-

Афганская война (1979—1989) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Афганская война (значения). Афганская война (1979 1989) … Википедия

-

Афганская война (фильм) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Афганская война (значения). Для улучшения этой статьи желательно?: Обновить статью, актуализировать данные … Википедия

-

Афганская война — … Википедия

-

Афганская война — (Afghan War) Конфликт между мусульм. афган. партизанами с одной стороны и правительственными и советскими (с 1979) войсками, стремившимися сохранить комм. режим в Афганистане, с другой. После переворота в апр. 1978 левые военные передали власть… … Энциклопедия битв мировой истории

-

Первая англо-афганская война — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Англо афганские войны … Википедия

-

Вторая англо-афганская война — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Англо афганские войны … Википедия

Сорок лет назад, 25 декабря 1979 года, СССР начал вводить войска в Афганистан. Предполагалось, что это будет молниеносная операция помощи дружественному режиму, однако война растянулась на десять лет. Ее называют одной из причин развала Советского Союза; через Кабул, Кандагар, Пули-Хумри, Панджшерское ущелье прошли около ста тысяч советских солдат, от 15 до 26 тысяч погибли. К годовщине начала ввода войск «Лента.ру» публикует монологи солдат и офицеров, воевавших в Афгане.

«Мы честно выполняли свой долг»

Алексей, Новосибирск:

Ни в Афгане, ни после я не встречал воинской части, находившейся в таких боевых условиях и при этом чуть ли не еженедельно подвергающейся обстрелам, и при всем при этом готовой выполнить любую поставленную перед ней задачу. Во время встреч на различных мероприятиях с ребятами, прошедшими дорогами Афгана, услышав в ответ на вопрос «Где служил?» — «Руха, Панджшер», они, как правило, выдавали такие тирады: «Нас Рухой пугали, мол, любой „залет“ — и поедете в Панджшер на воспитание». Вот такое мнение бытовало в ограниченном контингенте о нашем «бессмертном» рухинском гарнизоне!

Полк вошел в историю афганской войны как часть, понесшая самые большие потери в Панджшерской операции весной 1984 года. Наша часть (несмотря на то что находилась вдалеке от взора командования 108 МСД, и награды зачастую просто по какой-то нелепой сложившейся традиции с трудом доставались личному составу полка) тем не менее дала стране реальных героев Советского Союза В. Гринчака и А. Шахворостова. Невзирая на условия, в которых жил полк, мы честно выполняли свой долг. Пусть это звучит немного пафосно, но это так.

2884266 01.04.1988 Ограниченный контингент советских войск в Демократической Республике Афганистан (Исламская республики Афганистан).

Более 40 градусов по Цельсию в расположении парка боевой техники. В. Киселев / РИА Новости. Фото: В. Киселев / РИА Новости

Да простят меня ребята-саперы, если я поведаю о минной войне в Афганистане без свойственного им профессионализма. Попытаюсь доступным языком объяснить, что за устройства использовали моджахеды в этой необъявленной десятилетней войне.

Как мне рассказывали наши полковые саперы, многие мины итальянского производства были пневматического действия — то есть проезжала одна машина по мине, мина, соответственно, получала один уровень подкачки, затем вторая — еще один уровень, а вот третья или, скажем, шестая машина в колонне попадала под срабатывание взрывного механизма мины. Иначе говоря, механизм приводился в действие вот этим так называемым «подкачиванием», происходившим за счет нажатия колеса гусеницы нашей техники, и когда уровень доходил до критической точки — происходил взрыв.

Соответственно, когда в колонне, где до начала движения щупом был проверен каждый метр маршрута, происходил подрыв, это вызывало удивление и множество вопросов к саперам. Повторюсь, что, как мне объяснили саперы, по такой мине можно было проехать, если колесо машины не покрывало 3/4 площади мины, то есть проехал по ней, по 2/4 ее площади, — все равно, а вот следующая единица техники может запросто подорваться. Именно минная война принесла нам в Афганистане большое количество изувеченных ребят, особенно в Панджшерском ущелье.

«Там очень много грязи было»

Алексей Поспелов, 58 лет, служил в рембате с 1984-го по 1985 год, дважды ранен:

Честно говоря, все это уже стирается из памяти, только снится сейчас. Жара, пыль, болезни. У меня было осколочное ранение в голову и в ногу. Плюс к этому был тиф, паратиф, малярия и какая-то лихорадка. И гепатит. Болели гепатитом многие, процентов 90, если не больше.

Меня после распределения в 1982 году направили в Германию. Там я прослужил год и восемь месяцев, еще не женился к тому времени. Пришла разнарядка в Афганистан, меня вызвал командир и говорит: «Ты у нас единственный в батальоне холостой, неженатый. Как смотришь на это?»

Я говорю: «Командир, куда родина прикажет — туда и поеду». Он отвечает: «Тогда пиши рапорт». Я написал рапорт и поехал.

Various types of Soviet military helicopters, including a Mi-24 gunship, background center, are parked outside Kabul Airport, April 22, 1988. An estimated 115,000 Soviet troops still remain in Afghanistan but they will begin leaving May 15 under a U.N. mediated withdrawal agreement signed in Geneva on April 14. (AP Photo/Liu Heung-Shing). Фото: Liu Heung-Shing / AP

Сразу с пересылки мне дали направление в 58-ю бригаду матобеспечения, в населенный пункт Пули-Хумри, в 280 километрах от Кабула на север через перевал Саланг. Там я попал в рембат командиром ремонтно-восстановительного взвода. Скажешь, непыльная работа? Ну, а кто же технику с поля боя эвакуировал? И отстреливаться приходилось, конечно, не раз.

Я вспоминаю это время очень тепло, несмотря на все неприятности и трудности. У нас там люди разделились на тварей и нормальных — но это, наверное, всегда так бывает.

Вот, например, в 1986 году я получил направление в Забайкалье. Должен был в Венгрию ехать, но ротный мне всю жизнь испортил, перечеркнул, перековеркал.

К нам должен был начальник тыла приехать с инспекцией, и у нас решили в бане закопать треть от большой железнодорожной цистерны под нефть. А я в этот день как раз сменился с наряда, где-то часов в шесть. Вечернее построение, и ротный говорит Мироненко и еще одному парню: «Давайте быстро в баню».

Баня — это большая вырытая в земле яма, обложенная снарядными ящиками, заштукатуренная, приведенная в порядок. Там стояла здоровая чугунная труба — «поларис», как мы ее называли, в которую капала солярка, и она разогревалась добела. Она была обложена галькой. И там все парились. До того момента, как привезли эту цистерну, в холодную воду ныряли в резервный резиновый резервуар, двадцатипятикубовый.

И тут комбату приспичило закопать цистерну, чтобы прямо не выходя из бани можно было купаться в холодненькой. Все сделали, но у ротного появилась идея скрутить по ее краю трубу, наделать в ней дырок, чтобы фонтанчики были, и обеспечить таким образом подачу воды. Чтобы идиллия была — показать начальству: глядите, у нас все хорошо!

Но по времени это сделать не успевали. Ребята неделю этим занимались, практически не спали. А Мироненко, сварщик, был в моем взводе. На построении он из строя выходит ко мне и говорит: «Товарищ лейтенант, дайте мне хоть поспать, меня клинит!» Но ротный кричит Мироненко: «А ты что тут делаешь? А ну в баню, заканчивай все давай!»

PHOTO: WOJTEK LASKI/EAST NEWS Wyjscie wojsk radzieckich z Afganistanu. Afganistan, luty 1989 N/Z: sowieccy zolnierze pod prysznicem. Przygotowania do wycofania oddzialow z Afganistanu, po 9 latach militarnej obecnosci sowieckiej w tym kraju. The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. AFGHANISTAN — 02/1989 Pictured: The soviet soldiers taking a shower. The preparations to the Soviet military withdrawing from Afghanistan, ending nine years of Soviet presence in the country.. Фото: Wojtek Laski / East News

Как потом оказалось, Мироненко спустился на дно этой емкости, заснул и случайно затушил газовую горелку, которая продолжала работать. В этот момент его напарник, почувствовавший запах ацетилена от автогена, кричит ему туда: «Мирон, ты чего там делаешь, уснул? Ты не спи, я пойду баллон кислородный поменяю». И не перекрыл ацетилен. А Мироненко спросонья нашаривает в кармане коробок и чиркает спичкой. Понимаешь, какой объем взрывчатого вещества к тому времени там скопился? Разворотило все к чертовой матери.

Бахнуло, наверное, часов в 12. На следующий день начали разбор: чей подчиненный, кто дал команду… И ротный тут же все спихнул на меня — мол, это его подчиненный. И началось. Меня сразу же на гауптвахту засадили. Я на ней суток десять просидел, похудел на 18 килограммов. Камера была метр на метр, а в высоту — метр шестьдесят. Вот так я все это время сидел и почти не спал. А в углу камеры стоял такой же «поларис» и разогревался. Фактически я был вдавлен в стенку. Это ужасно — по-моему, даже фашисты такого не придумывали.

Когда было партсобрание, меня исключили из партии за ненадлежащий контроль над личным составом. Прокуратура на меня уголовное дело завела. Но всех опросили и выяснили, что я, наоборот, пытался не дать этому парню пойти работать, и, пополоскав меня, дело закрыли. Хрен бы с этим начальником тыла, купался бы в этой резиновой емкости, ничего страшного. Но ротному приспичило рвануть задницу, чтобы капитана получить…

А так — не только негатив был. Хорошие нормальные люди там как братья были. Некоторые афганцы, пуштуны, лучше к нам относились, чем многие наши командиры. Люди другие были. Там, в экстремальной обстановке, совершенно по-другому все воспринимается. Тот, с кем ты сейчас чай пьешь, возможно, через день-два тебе жизнь спасет. Или ты ему.

Но сейчас туда, конечно, ни за что бы не поехал. Бешеные деньги, которые там крутились, никому добра не принесли. Со мной несколько человек были, которые, я знаю, наркотой торговали. Бывает, попадут в БМП из гранатомета, от бойца фарш остается — ничего практически. Цинковый гроб отправлять вроде надо. И в этих гробах везли героин в Союз. Я не могу этого утверждать точно, но знакомые офицеры об этом много раз рассказывали, и в том, что это было, уверен на 99,9 (в периоде) процентов.

Там очень много грязи было. А я был идеалистом. Когда меня выгнали из партии, я стреляться собирался, не поверишь. Это я сейчас понимаю, какой был дурак, я воспитан так был. Мой отец всю жизнь был коммунистом, оба деда в Великую Отечественную были… Я сейчас понимаю, что это шоры были идеологические, нельзя было так думать.

В 90-е, когда Ельцин встал у власти, я написал заявление и сам вышел из партии. Ее разогнали через год или около того. Сказал в парткоме: я с вами ничего общего не хочу иметь. Почему? Да просто разложилось все, поменялось. Самым главным для людей стали деньги. У народной собственности появились хозяева. Нас просто очень долго обманывали. А может, и сейчас обманывают.

2884263 01.08.1988 Когда погибают мужчины, оружие в руки берут женщины.

Республика Афганистан (Исламская республика Афганистан). Афганская война (1979-1989г.г.) В. Киселев / РИА Новости. Фото: В. Киселев / РИА Новости

«Пить — пили, и пили много»

Юрий Жданов, майор мотострелковых войск, служил в Афганистане в 1988 году:

Я в 1980 году служил в Забайкалье лейтенантом, и там всеобщий порыв был: давай, мол, ребята, туда, в Афган! И все написали рапорты. Все мы — господа офицеры (которые тогда еще господами не назывались), так и так, изъявляем желание. Но тогда все эти рапорты положили под сукно.

Потом я поехал служить в Таманскую дивизию командиром батальона. Служил, служил, вроде хороший батальон, а потом, во второй половине 80-х, не пойми что твориться стало. Написал рапорт по новой — мол, хочу в Афган. Ну и поехал.

В наш полк специально прилетали вертушки из штаба армии за хлебом и за самогончиком. Гнали прекрасно — на чистейшей горной воде. Бывало, водку привозили из Союза, но это редкость была. Но не только из Союза водкой торговали, в дуканах можно было паленую купить, да и какую угодно. Я имел доступ к лучшему техническому спирту, который по службе ГСМ шел. Пили все — не так, конечно, чтобы все в перепитом состоянии были. Но пить — пили, и пили много.

Я в режимной зоне Баграма, будучи замкомандира полка, курировал вопросы тех подразделений, которые от полка там стояли: третий батальон, зенитно-ракетная батарея, третья артиллерийская батарея и батальон на трассе. Поскольку я находился близко от штаба дивизии, комдив Барынкин привлек меня к работе с местными, поставил мне задачу: мол, посмотри-послушай, чем они там дышат. И я на его совещаниях по этому вопросу присутствовал. Получить информацию о них иначе как вращаясь в их среде было никак невозможно. Вот этим я и занимался.

С «зелеными» — солдатами Наджибуллы, которые за нас воевали, — тоже приходилось работать. Ездили, с местными общались — есть фотографии, когда мы приезжаем, вокруг бородатые стоят, а мы броней идем — колонной. А они там со всякими «хренями и менями» в боевые действия не вступили, склонили на переговоры — тоже показывали свою силу.

Я таджиков-солдатиков из третьего батальона взял и туда, в совмещенный командный пункт, который в Баграме был, где их штаб находился, чтобы они с местными поговорили. На первый день послал одного, на второй — другого. Я специально с собой таджиков взял, причем не простых, а которые на фарси говорили, — большинство афганцев общается на этом наречии.

Taliban gunners clean 120mm tank shells Monday, Oct 8, 1996 before firing on enemy positions in the Panjshir valley. The Taliban continues to pursue the ex-government army following its capture of the Afghanistan capital, Kabul.(A P Photo/ John Moore). Фото: John Moore / AP

Один из этих моих солдатиков рассказывал, что они попытались его «заблатовать»: «Давай, мол, беги по-быстрому к нам в банду, мы тебя в Пакистан переправим, скоро шурави (русские) уходят. Тебя там в Пакистане поучат, а Союз-то скоро развалится. Ты придешь к себе в Таджикистан и будешь там большим человеком». Это 1988 год! Для меня, партийного и офицера, это звучало как бред сивой кобылы. Мысль о том, что Союз развалится, — вообще была из области фантастики.

Когда я приехал в Афган, дальние гарнизоны уже начали выходить. И я смысла не понимал: на хрена мне, ребята, туда ехать? На хрена вы меня туда послали? Война чем хороша? Когда идет движение, когда ты воюешь. А когда войска стоят на месте, они сами себя обсирают и портят все, что находится вокруг них. Но раз выходили — значит, была такая политическая необходимость, это тоже все понимали.

Афган на меня сильно повлиял тем не менее. Меняются отношения — на политическом уровне и на личном. И еще я помню, как офицеры клали на стол рапорты еще до расформирования подразделений. Там сидели кадры «оттуда» и просили их: да у тебя два ордена, ты что, куда? — Нет, я увольняюсь… Судьба и война приводят каждого к законному знаменателю.

А потом, уже после всего этого, я узнал, что Саша Лебедь, который был у нас в академии секретарем партийной организации курса, который разглагольствовал с партийной трибуны о социалистической Родине, вместе с Пашей Грачевым поддержал Борю Ельцина, когда развал СССР пошел. И я понял, что ловить здесь нечего. У нас тут предатели везде.

Пашу потом министром обороны сделали, Саша Лебедь вылез в политические деятели. Наш начальник разведки дивизии поначалу к нему прильнул и, так сказать, вскоре улетел в мир иной. А потом и Саша Лебедь вслед за ним отправился. Политика — дело сложное, интересное…

827905 31.08.1988 Республика Афганистан (Исламская республика Афганистан). Пребывание ограниченного контингента советских войск в Афганистане. Механизированное подразделение советских войск направляется в район Пагман. Андрей Соломонов / РИА Новости. Фото: Андрей Соломонов / РИА Новости

«У тех, кто войну прошел, правильное понимание вещей возникает»

Отец Валерий Ершов, служил в Афганистане заместителем командира роты в бригаде обеспечения в городе Пули-Хумри, отслужил 10 месяцев вплоть до вывода войск из Афганистана:

Шла уже вторая половина 80-х, и все мы знали, что это за место — Афганистан, общались с ребятами, которые там воевали. Я решил, что надо себя испытать. Человек ведь всегда проверяется в деле, хотя был и страх смерти, и страх попасть в плен, конечно. Потому я добровольцем отправился в Афганистан и о своем решении не жалею.

Рота у нас была большая и нестандартная — 150 человек. Называлась местной стрелковой. Я такого больше нигде не встречал. Подчинялась рота непосредственно начальнику штаба бригады, которого мы все звали «мама». Люди туда отбирались и хорошо оснащались.

Мы охраняли огромные склады 58-й армии. Оттуда уходили колонны в боевые подразделения Афганистана, порой приходилось участвовать в сопровождении этих колонн, поэтому мне довелось побывать и в Кабуле, и в Кундузе, и некоторых других местах.

Когда командир роты заболел, я три месяца исполнял его обязанности. Именно тогда, в августе 88-го, у нас произошло вошедшее в историю афганской войны ЧП — взрывы на артиллерийских складах.

Несколько часов мы провели под этой бомбежкой. Создалась мощная кумулятивная струя. Ветер, гарь от взрывов. Часть казарм сгорела подчистую. Запах был чудовищный. Ко мне в комнату влетела мина и не разорвалась. Упала рядом с койкой. Саперы потом ее вынесли.

Осколков было в воздухе столько, будто дождь шел. Я действовал на автомате, как на тренировках.

Помню, на командном пункте подошел прапорщик и попросил отпустить его, чтобы забрать бойца с поста. Я разрешил. Он надел бронежилет, каску, взял автомат и вышел. Смотрю, вокруг него все рвется, а он идет как заговоренный. Нужно было далеко идти. Два километра.

Часть дороги была видна. Обратно так же шел: не сгибаясь, спокойно. Я про себя думал: «Неужели так можно идти?» Но солдата прапорщик не нашел. Мы отправились с ним во второй раз уже на БРДМ. Машина почти сразу просела. Колеса нашпиговало осколками, включилась самоподкачка шин, так и доехали до места. Там пришлось выходить. Солдат нашелся, живой, прятался за камнем.

Fot. Wojtek Laski / East News Wyjscie wojsk radzieckich z Afganistanu. Afganistan, maj 1988. N/z: lozko radzieckiego zolnierza zabitego w Afganistanie — szeregowy Aleksandr Leonidowicz Frolow zginal w wieku 20 lat. Фото: Wojtek Laski / East News

Ни один человек у меня из подразделения в этом пекле не погиб. Как тут не поверить в то, что не все в жизни подчиняется законам физики и математики?

У меня у самого после прогулок под огнем — ни одного осколка на бронежилете, на каске, ни одной зацепки даже на форме не осталось. Тот день стал для меня в каком-то смысле поворотным.

В Бога я в ту пору еще не верил. Был таким человеком, который ищет справедливости во всем. С одной стороны, в этом есть своя чистота, а с другой — наивность. Среди подчиненных принципиально неверующих людей не было. По крайней мере у всех, когда выходили на утренний осмотр, были либо вырезанные крестики, либо пояски с 90-м псалмом. Такова военная традиция.

Я порой подтрунивал над солдатами: «Что это такое? Ведь вы же коммунисты, комсомольцы, а верите какой-то ерунде»… Но снимать кресты не просил.

На границе между жизнью и смертью, да еще и в чужой стране, отношения между солдатами были пропитаны абсолютным доверием. В Афгане я мог подойти к любому водителю и попросить, чтобы меня подбросили куда-то. Без вопросов. То же самое — на вертолете. Ни о каких деньгах, как вы понимаете, речи быть не могло.

При этом никакого панибратства, понимаете? Вот в чем штука. Я подчиненных называл по имени-отчеству, но это не отменяло постоянных тренировок и других методов поддержания подразделения в форме, чтобы люди были готовы ко всему. Приказы не надо было повторять дважды, не надо было даже проверять их исполнение. Единственное, насколько было можно, мы делали бойцам щадящие условия: три часа на сон вместо двух, потом — час бодрствования и еще два — в наряде.

Одна из главных проблем афганцев — это обида, что здесь, в Союзе, все не так, как было в Афгане. В первую очередь не хватало таких же теплых отношений между людьми.

Порой нас встречали даже с некоторой враждебностью. Так, по возвращении из Афгана мы с другим офицером хотели новые фуражки получить. Объяснили, что в командировке вся форма поистерлась и так далее, а нам ответили: «Мы вас туда не посылали». Я понимаю, что это расхожая фраза, но так действительно говорили и, разумеется, не все ветераны, а особенно те, что сражались на передовой, могли молча такое проглотить.

PHOTO: WOJTEK LASKI/EAST NEWS Wyjscie wojsk radzieckich z Afganistanu. Afganistan, luty 1989 N/Z: przygotowania do wycofania oddzialow z Afganistanu, po 9 latach militarnej obecnosci sowieckiej w tym kraju. The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. AFGHANISTAN — 02/1989 Pictured: the preparations to the Soviet military withdrawing from Afghanistan, ending nine years of Soviet presence in the country.. Фото: Wojtek Laski / East News

Сперва афганцы держались вместе. Помню, в первые годы ветераны создавали много патриотических обществ, а потом эти общества стали лопаться как мыльные пузыри.

Не стало той страны, за которую мы воевали. У людей, да и у нас тоже, уже были другие цели, задачи. Многим хотелось стать богаче. Льготы появились. С одной стороны, это хорошо, но с другой — начались какие-то трения: кто кому чего дал или не дал. Я встречал таких афганцев, которые озлоблялись на весь мир и друг на друга. Взрывы на Котляковском кладбище — это же были разборки между ними.

Мне повезло, вернее, Господь меня увел от таких проблем. Я нашел отношения, схожие с теми, какие были в Афгане, в среде верующих людей. У тех, кто войну прошел, правильное понимание вещей возникает. Часто ветераны к своим наградам относятся так: «Разве это мои ордена и медали? Это все товарищи мои боевые, а я тут ни при чем». Или даже так говорят: «Это Господь мне помог, это его заслуга».

| Soviet–Afghan War | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the Afghanistan conflict | ||||||

Top, bottom:

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

|

Paramilitaries:

Supported by:

|

Factions:

Supported by:

Factions:

Supported by:

Factions:

Supported by:

|

|||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Strength | ||||||

|

|

|||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||

|

|

|||||

|

Civilian casualties (Afghan):

562,000–2,000,000 killed[49][50][51] |

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen after the former militarily intervened in, or launched an invasion of,[nb 1] Afghanistan to support the local pro-Soviet government that had been installed during Operation Storm-333. Most combat operations against the mujahideen took place in the Afghan countryside, as the country’s urbanized areas were entirely under Soviet control.

While the mujahideen were backed by various countries and organizations, the majority of their support came from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United States, the United Kingdom, China, and Iran; the American pro-mujahideen stance coincided with a sharp increase in bilateral hostilities with the Soviets during the Cold War. The conflict led to the deaths of between 562,000[49] and 2,000,000 Afghans, while millions more fled from the country as refugees;[56][57][50][51] most externally displaced Afghans sought refuge in Pakistan and in Iran. Approximately 6.5% to 11.5% of Afghanistan’s erstwhile population of 13.5 million people (per the 1979 census) is estimated to have been killed over the course of the conflict. The Soviet–Afghan War caused grave destruction throughout Afghanistan, and has also been cited by scholars as a significant factor that contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union,[58][59] formally ending the Cold War.[59][60] It was the most violent phase of the Afghanistan conflict (1978–present).

The foundations of the conflict were laid by the Saur Revolution in 1978, which saw the nationwide seizure of power by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). After executing then-president Mohammed Daoud Khan and purging his supporters, the PDPA initiated a series of radical land reforms and modernization efforts throughout Afghanistan. These policies were deeply unpopular among much of the conservative rural population and established power structures, who saw the PDPA’s socialism as an ideologically disruptive force against Islamic conservatism.[61] Widespread dismay over the new policies was exacerbated by the repressive nature of the PDPA’s Democratic Republic government,[62] which vigorously suppressed all opposition and executed thousands of political prisoners, ultimately leading to the rise of many anti-government militant groups. By April 1979, large parts of Afghanistan had erupted in open rebellion.[63]

In addition to civil unrest across the country, the PDPA was experiencing deep internal turmoil due to factional rivalries between the Khalqists and the Parchamites; in September 1979, PDPA General-Secretary Nur Muhammad Taraki was assassinated on orders from the PDPA’s second-in-command, Hafizullah Amin. Amin’s supersession of Taraki put the Khalqists at an advantage against the Parchamites, while greatly souring Afghanistan’s relationship with the Soviet Union. With fears rising that Amin was planning to ally Afghanistan with the United States,[64] Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev led his government to deploy the 40th Army inside Afghanistan on 24 December 1979.[65] Arriving in the capital city of Kabul, the Soviet military contingent stormed the Tajbeg Palace and assassinated Amin,[66] subsequently installing Parchamite-affiliated Babrak Karmal as Afghanistan’s new pro-Soviet leader.[63] The decision by the Soviet Union to directly intervene in Afghanistan was based on the Brezhnev Doctrine.

In January 1980, foreign ministers from 34 countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation adopted a resolution demanding «the immediate, urgent and unconditional withdrawal of Soviet troops» from Afghanistan.[67] Simultaneously, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution protesting the Soviet military deployment by a vote of 104 (for) to 18 (against), with 18 abstentions and 12 absentees/non-participants.[67][68] Angola, East Germany, India, and Vietnam were the only countries that expressed support for the presence of Soviet troops in Afghanistan.[69]

Afghan insurgents began to receive general aid, financing, and military training in neighbouring Pakistan. The United States and the United Kingdom also provided an extensive amount of support to the mujahideen, routed through the Pakistani effort as part of Operation Cyclone.[70][71] Heavy financing for the insurgents also came from China and the Arab monarchies of the Persian Gulf.[72][16][73][74]

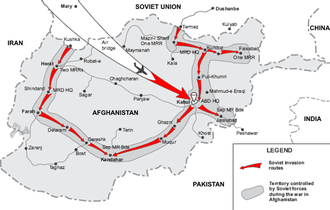

Soviet troops occupied Afghanistan’s cities and all main arteries of communication, whereas the mujahideen waged guerrilla warfare in small groups across the 80% of the country that was not subject to uncontested Soviet control—almost exclusively comprising the rugged, mountainous terrain of the countryside.[75][76][77] In addition to laying millions of landmines across Afghanistan, the Soviets used their aerial power to deal harshly with both rebels and civilians, levelling villages to deny safe haven to the mujahideen and destroying vital irrigation ditches.[78][79][80][81]

Numerous sanctions and embargoes were imposed on the Soviet Union by the international community following the deployment. As bilateral tensions increased, the United States initiated the 1980 Summer Olympics boycott, and the Soviet Union later initiated the 1984 Summer Olympics boycott, with both sides leading a number of countries to withdraw from participating in the events at Moscow and Los Angeles, respectively.[82]

The Soviet government had initially planned to swiftly secure Afghanistan’s towns and road networks, stabilize the PDPA government under loyalist Karmal, and withdraw all of their military forces in a span of six months to one year. However, they were met with fierce resistance from Afghan guerrillas[83] and experienced great operational difficulties on Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain.[84][85] By the mid-1980s, the Soviet military presence in Afghanistan had increased to approximately 115,000 troops, and fighting across the country intensified; the complication of the war effort gradually inflicted a high cost on the Soviet Union as military, economic, and political resources became increasingly exhausted.

By mid-1987, reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev announced that the Soviet military would begin a complete withdrawal from Afghanistan, following a series of meetings with the Afghan government that outlined a policy of «National Reconciliation» for the country.[10][11] The final wave of disengagement was initiated on 15 May 1988, and on 15 February 1989, the last Soviet military column occupying Afghanistan crossed into the Uzbek SSR. With continued external Soviet backing, the PDPA government pursued a solo war effort against the mujahideen, and the conflict evolved into the Afghan Civil War. However, the Afghan government lost all support as the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991, leading to the toppling of the PDPA’s Democratic Republic at the hands of the mujahideen in 1992.

Due to the length of the Soviet–Afghan War, it has sometimes been referred to as the «Soviet Union’s Vietnam War» or as the «Bear Trap» by sources from the Western world.[86][87][88] It has left a mixed legacy in the post-Soviet countries as well as in Afghanistan.[60] Additionally, American support for the mujahideen in Afghanistan during the conflict is thought to have contributed to a «blowback» of unintended consequences against American interests (e.g., the September 11 attacks), which ultimately led to the United States’ War in Afghanistan from 2001 until 2021.

Naming

In Afghanistan the war is usually called the Soviet war in Afghanistan (Pashto: په افغانستان کې شوروی جګړه Pah Afghanistan ke Shuravi Jagera, Dari: جنگ شوروی در افغانستان Jang-e Shuravi dar Afghanestan). In Russia and elsewhere in the former Soviet Union it is usually called the Afghan war (Russian: Афганская война, Ukrainian: Війна в Афганістані, Belarusian: Афганская вайна, Uzbek: Afgʻon urushi); it is sometimes simply referred to as «Afgan» (Russian: Афган), with the understanding that this refers to the war (just as the Vietnam War is often called «Vietnam» or just «‘Nam» in the United States).[89] It is also internationally known as the Afghan jihad, especially by the non-Afghan volunteers of the Mujahideen.

Background

Russian interest in Central Asia

In the 19th century, the British Empire was fearful that the Russian Empire would invade Afghanistan and use it to threaten the large British holdings in India. This regional rivalry was called the «Great Game». In 1885, Russian forces seized a disputed oasis south of the Oxus River from Afghan forces, which became known as the Panjdeh Incident and threatened war. The border was agreed by the joint Anglo-Russian Afghan Boundary Commission of 1885–87. The Russian interest in the region continued on through the Soviet era, with billions in economic and military aid sent to Afghanistan between 1955 and 1978.[90]

Following Amanullah Khan’s ascent to the throne in 1919 and the subsequent Third Anglo-Afghan War, the British conceded Afghanistan’s full independence. King Amanullah afterwards wrote to Moscow (now under Bolshevik control) desiring for permanent friendly relations. Vladimir Lenin replied by congratulating the Afghans for their defence against the British, and a treaty of friendship between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union was finalized in 1921. The Soviets saw possibilities in an alliance with Afghanistan against the United Kingdom, such as using it as a base for a revolutionary advance towards British-controlled India.[91][92]

The Red Army intervened in Afghanistan against the Basmachi movement in 1929 and 1930 to support the ousted king Amanullah, as part of the Afghan Civil War (1928–1929).[93][94] The Basmachi movement had originated in a 1916 Muslim revolt against Russian conscription during WWI, bolstered by exiled Turkish general Enver Pasha during the Russian Civil War. The Red Army consolidated Central Asia in a deployment (120,000–160,000) that resembled the peak strength of the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in size.[93] By 1926–1928 the Basmachis were mostly defeated by the Soviets and Central Asia incorporated into the Soviet Union.[93][95] In 1929, the Basmachi rebellion reappeared, associated with anti-collectivization riots,[93] while Basmachis crossed over into Afghanistan under Ibrahim Beg, which was a pretext for the Red Army operations in 1929 and 1930.[93][94]

Soviet–Afghan relations post-1920s

The Soviet Union (USSR) had been a major power broker and influential mentor in Afghan politics, its involvement ranging from civil-military infrastructure to Afghan society.[96] Since 1947, Afghanistan had been under the influence of the Soviet government and received large amounts of aid, economic assistance, military equipment training and military hardware from the Soviet Union. Economic assistance and aid had been provided to Afghanistan as early as 1919, shortly after the Russian Revolution and when the regime was facing the Russian Civil War. Provisions were given in the form of small arms, ammunition, a few aircraft, and (according to debated Soviet sources) a million gold rubles to support the resistance during the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919. In 1942, the USSR again moved to strengthen the Afghan Armed Forces by providing small arms and aircraft, and establishing training centers in Tashkent (Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic). Soviet-Afghan military cooperation began on a regular basis in 1956, and further agreements were made in the 1970s, which saw the USSR send advisers and specialists. The Soviets also had interests in the energy resources of Afghanistan, including exploring oil and natural gas from the 1950s and 1960s.[97] The USSR began to import Afghan gas from 1968 onward.[98]

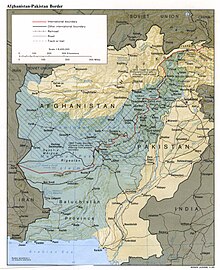

Afghanistan-Pakistan border

In the 19th century, with the Czarist Russian forces moving closer to the Pamir Mountains, near the border with British India, civil servant Mortimer Durand was sent to outline a border, likely in order to control the Khyber Pass. The demarcation of the mountainous region resulted in an agreement, signed with the Afghan Emir, Abdur Rahman Khan, in 1893. It became known as the Durand Line.[99]

In 1947, the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Afghanistan, Mohammed Daoud Khan, rejected the Durand Line, which was accepted as an international border by successive Afghan governments for over half a century.[100]

The British Raj also came to an end, and the Dominion of Pakistan gained independence from British India and inherited the Durand Line as its frontier with Afghanistan.

Under the regime of Daoud Khan, Afghanistan had hostile relations with both Pakistan and Iran.[101][102] Like all previous Afghan rulers since 1901, Daoud Khan also wanted to emulate Emir Abdur Rahman Khan and unite his divided country.

To do that, he needed a popular cause to unite the Afghan people divided along tribal lines, and a modern, well equipped Afghan army which would be used to suppress anyone who would oppose the Afghan government. His Pashtunistan policy was to annex Pashtun areas of Pakistan, and he used this policy for his own benefit.[102]

Daoud Khan’s irredentist foreign policy to reunite the Pashtun homeland caused much tension with Pakistan, a state that allied itself with the United States.[102] The policy had also angered the non-Pashtun population of Afghanistan,[103] and similarly, the Pashtun population in Pakistan were also not interested in having their areas being annexed by Afghanistan.[104] In 1951, the U.S. State Department urged Afghanistan to drop its claim against Pakistan and accept the Durand Line.[105]

1960s–1970s: Proxy war

The existing Afghanistan–Pakistan border and maximum extent of claimed territory

In 1954, the United States began selling arms to its ally Pakistan, while refusing an Afghan request to buy arms, out of fear that the Afghans would use the weapons against Pakistan.[105] As a consequence, Afghanistan, though officially neutral in the Cold War, drew closer to India and the Soviet Union, which were willing to sell them weapons.[105] In 1962, China defeated India in a border war, and as a result, China formed an alliance with Pakistan against their common enemy, India, pushing Afghanistan even closer to India and the Soviet Union.

In 1960 and 1961, the Afghan Army, on the orders of Daoud Khan following his policy of Pashtun irredentism, made two unsuccessful incursions into Pakistan’s Bajaur District. In both cases, the Afghan army was routed, suffering heavy casualties.[106] In response, Pakistan closed its consulate in Afghanistan and blocked all trade routes through the Pakistan–Afghanistan border. This damaged Afghanistan’s economy and Daoud’s regime was pushed towards closer alliance with the Soviet Union for trade. However, these stopgap measures were not enough to compensate the loss suffered by Afghanistan’s economy because of the border closure. As a result of continued resentment against Daoud’s autocratic rule, close ties with the Soviet Union and economic downturn, Daoud Khan was forced to resign by the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah. Following his resignation, the crisis between Pakistan and Afghanistan was resolved and Pakistan re-opened the trade routes.[106] After the removal of Daoud Khan, the King installed a new prime minister and started creating a balance in Afghanistan’s relation with the West and the Soviet Union,[106] which angered the Soviet Union.[104]

Ten years later, in 1973, Mohammed Daoud Khan, supported by Soviet-trained Afghan army officers, seized power from the King in a bloodless coup, and established the first Afghan republic.[106] Following his return to power, Daoud revived his Pashtunistan policy and for the first time started proxy warring against Pakistan[107] by supporting anti-Pakistani groups and providing them with arms, training and sanctuaries.[104] The Pakistani government of prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was alarmed by this.[108] The Soviet Union also supported Daoud Khan’s militancy against Pakistan[104] as they wanted to weaken Pakistan, which was an ally of both the United States and China. However, it did not openly try to create problems for Pakistan as that would damage the Soviet Union’s relations with other Islamic countries, hence it relied on Daoud Khan to weaken Pakistan. They had the same thought regarding Iran, another major U.S. ally. The Soviet Union also believed that the hostile behaviour of Afghanistan against Pakistan and Iran could alienate Afghanistan from the west, and Afghanistan would be forced into a closer relationship with the Soviet Union.[109] The pro-Soviet Afghans (such as the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA)) also supported Daoud Khan hostility towards Pakistan, as they believed that a conflict with Pakistan would promote Afghanistan to seek aid from the Soviet Union. As a result, the pro-Soviet Afghans would be able to establish their influence over Afghanistan.[110]

In response to Afghanistan’s proxy war, Pakistan started supporting Afghans who were critical of Daoud Khan’s policies. Bhutto authorized a covert operation under MI’s Major-General Naseerullah Babar.[111] In 1974, Bhutto authorized another secret operation in Kabul where the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and the Air Intelligence of Pakistan (AI) extradited Burhanuddin Rabbani, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Ahmad Shah Massoud to Peshawar, amid fear that Rabbani, Hekmatyar and Massoud might be assassinated by Daoud.[111] According to Baber, Bhutto’s operation was an excellent idea and it had hard-hitting impact on Daoud and his government, which forced Daoud to increase his desire to make peace with Bhutto.[111] Pakistan’s goal was to overthrow Daoud’s regime and establish an Islamist theocracy in its place.[112] The first ever ISI operation in Afghanistan took place in 1975,[113] supporting militants from the Jamiat-e Islami party, led by Ahmad Shah Massoud, attempting to overthrow the government. They started their rebellion in the Panjshir valley, but lack of support along with government forces easily defeating them made it a failure, and a sizable portion of the insurgents sought refuge in Pakistan where they enjoyed the support of Bhutto’s government.[108][110]