Перевод «Афины» на греческий

Αθήνα, αθήνα — самые популярные переводы слова «Афины» на греческий.

Пример переведенного предложения: Я поеду в Афины. ↔ Θα πάω στην Αθήνα.

Афины

proper

существительное pluralia tantum

грамматика

-

Я поеду в Афины.

Θα πάω στην Αθήνα.

-

αθήνα

Я поеду в Афины.

Θα πάω στην Αθήνα.

Жак Рогге, президент Международного олимпийского комитета (МОК), отметил: «Те, кто знал Афины до Игр и увидит их после Игр, не узнают город».

Ο Ζακ Ρογκ, πρόεδρος της Διεθνούς Ολυμπιακής Επιτροπής (ΔΟΕ), σχολίασε: «Όσοι ήξεραν την Αθήνα πριν από τους Αγώνες και θα τη δουν έπειτα από αυτούς δεν θα την αναγνωρίζουν».

Вы должны выяснить и затем объяснить нам причину, по которой Ким Хо Гюн вступил в контакт с » Афиной «.

Θα πρέπει να μας άφησετε να μάθουμε γιατί ο Στρατηγός Κιμ συνεργαζόταν με την ΑΘΗΝΑ.

Неудивительно, что один ученый пришел к следующему выводу: «По моему мнению, сообщение о пребывании Павла в Афинах отличается живостью, свойственной очевидцу тех событий».

Εύλογα, κάποιος λόγιος κατέληξε στο εξής συμπέρασμα: «Κατ’ εμέ, η αφήγηση της επίσκεψης του Παύλου στην Αθήνα δίνει την εντύπωση αφήγησης αυτόπτη μάρτυρα».

Несколько дней спустя он вернулся в Афины, не только с атрибутами эллинского православия, но и с самим Понтом, как написал тогдашний депутат правительства Венизэлу, Леонид Иасонидис (Λεωνίδας Iασωνίδης): «В Греции жили Понтийцы, но не жил Понт.

Λίγες μέρες αργότερα επέστρεφε στην Aθήνα όχι μόνο με τα σύμβολά μας, αλλά και με τον Πόντο, όπως είχε γράψει τότε ο υπουργός Προνοίας της κυβέρνησης του Eλευθερίου Bενιζέλου Λεωνίδας Iασωνίδης: «Eν Eλλάδι υπήρχαν οι Πόντιοι, αλλά δεν υπήρχεν ο Πόντος.

22 В I веке н. э. греческий город Афины был известным научным центром.

22 Τον πρώτο αιώνα της Κοινής μας Χρονολογίας, η Αθήνα ήταν διάσημο κέντρο μάθησης.

Также поступил апостол Павел в ареопаге или на Марсовом холме в Афинах (Деяния 2:22; 17:22, 23, 28).

Το ίδιο έκανε και ο απόστολος Παύλος στον Άρειο Πάγο των Αθηνών.—Πράξεις 2:22· 17:22, 23, 28.

НТС известно о существовании » Афины «.

Η NTS έχει μια αναφορά για την ΑΘΗΝΑ.

Пока я служил в Греции, мне удалось посетить незабываемые конгрессы в Афинах, Фессалониках, а также на островах Родос и Крит.

Ενώ υπηρετούσα στην Ελλάδα, μπόρεσα να παρακολουθήσω αξιομνημόνευτες συνελεύσεις στην Αθήνα, στη Θεσσαλονίκη, στη Ρόδο και στην Κρήτη.

Делосский союз был создан Афинами и многими городами-государствами бассейна Эгейского моря, чтобы продолжить войну с Персией после первого и второго персидских вторжений в Грецию (492—490 и 480—479 годы до н. э. соответственно).

Η Δηλιακή Συμμαχία συγκροτήθηκε μεταξύ της Αθήνας και πόλεων-κρατών του Αιγαίου, μετά την αποχώρηση των Σπαρτιατών από την προηγούμενη ελληνική συμμαχία, με κύριο σκοπό να συνεχιστεί ο πόλεμος κατά της Περσίας, ο οποίος ξεκίνησε με την πρώτη και συνεχίστηκε με τη δεύτερη περσική εισβολή στην Ελλάδα (492-490 π.Χ και 480-479 π.Χ αντίστοιχα).

Мне Афина поет колыбельные.

Почему Афина до сих пор хранила это диск в тайне?

Γιατι η Αθηνά κράτησε την πληροφορία στη δισκέτα μυστική;

Когда же Афины, Спарта и Эретрия с пренебрежением отвергли требования Персии, ранним летом 490 года до н. э. мощные войска персидской кавалерии и пехоты направились в Грецию.

Όταν η Αθήνα, η Σπάρτη και η Ερέτρια αρνήθηκαν με περιφρόνηση να ικανοποιήσουν τις απαιτήσεις της Περσίας, μια ισχυρή δύναμη περσικού ιππικού και πεζικού απέπλευσε για την Ελλάδα στις αρχές του καλοκαιριού του 490 Π.Κ.Χ.

Но одно событие особенно повлияло на творчество Аристофана — Пелопоннесская война между Афинами и Спартой.

Ένα συγκεκριμένο θέμα ενέπνευσε μεγάλο μέρος του έργου του Αριστοφάνη: ο Πελοποννησιακός Πόλεμος ανάμεσα στην Αθήνα και στην Σπάρτη.

Через некоторое время сама Византия стала подчиняться Афинам.

Έπειτα από μερικά χρόνια, περιήλθε και το Βυζάντιο στην κυριαρχία της Αθήνας.

Сохранившийся до наших дней Ареопаг в Афинах, или холм Ареса, где проповедовал Павел, безмолвно свидетельствует о достоверности книги Деяния (Де 17:19).

Μέχρι σήμερα ο Άρειος Πάγος, δηλαδή ο Λόφος του Άρη, στην Αθήνα, όπου κήρυξε ο Παύλος, επιβεβαιώνει σιωπηλά την αξιοπιστία των Πράξεων.

В отличие от массовых актов возмездия во Франции и Италии против сотрудников оккупантов, которые через несколько часов после Освобождения превратились в кровавую баню с 9.000 и 12.000-20.000 убитых соответственно, в Афинах ЭЛАС дал приказ не допустить актов насилия и самосуда.

Σε αντίθεση με τις μαζικές αντεκδικήσεις σε Ευρωπαϊκές χώρες όπως η Γαλλία και η Ιταλία που έγιναν εις βάρος των συνεργαζόμενων με τις Κατοχικές δυνάμεις ελάχιστες ώρες μετά την Απελευθέρωση τους όπου έγινε λουτρό αίματος με 9.000 και 12.000-20.000 νεκρούς αντίστοιχα, στην Αθήνα αντίθετα δίδεται από τον ΕΛΑΣ Αθηνών εντολή να μη υπάρξουν βίαια έκτροπα.

Она родилась в Афинах в 1956 году.

Γεννήθηκε στην Αθήνα το 1956.

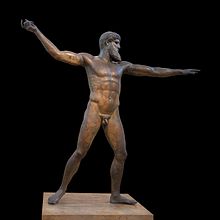

Статуя Афины исчезла из Пафенона в V веке н. э., а ее храмы превратились в развалины, из которых немногие сохранились до наших дней.

Το άγαλμα της Αθηνάς εξαφανίστηκε από τον Παρθενώνα τον πέμπτο αιώνα Κ.Χ., ενώ μόνο τα ερείπια λίγων ναών της υπάρχουν ακόμη.

ОЖИДАЯ в Афинах своих попутчиков, апостол Павел воспользовался этим временем, чтобы проповедовать неформально.

ΑΞΙΟΠΟΙΩΝΤΑΣ το χρόνο του ενώ περίμενε στην Αθήνα τους αδελφούς του που τον συντρόφευαν στο ταξίδι του, ο απόστολος Παύλος ασχολήθηκε με την ανεπίσημη μαρτυρία.

Павел не думал, что Бог непостижим, а подчеркивал, что люди, которые построили тот жертвенник в Афинах, а также многие другие среди его слушателей пока еще не знали Бога.

Ναι, αντί να υπονοήσει ότι δεν μπορούμε να γνωρίσουμε τον Θεό, ο Παύλος τόνισε ότι οι άνθρωποι που είχαν κατασκευάσει εκείνον το βωμό στην Αθήνα, καθώς και πολλοί άλλοι από το ακροατήριό του, δεν Τον είχαν γνωρίσει ακόμη.

Поскольку многие из приехавших в Афины пережили трудные времена, их часто волнуют вопросы о смысле жизни и виды на будущее.

Εφόσον πολλοί από αυτούς τους νεοφερμένους έχουν περάσει δύσκολες στιγμές, συνήθως έχουν ερωτήματα σχετικά με το νόημα της ζωής και τις προοπτικές που υπάρχουν για το μέλλον.

В 1843 году, жители этого района, малолюдного после освобождения от осман, Афин решили построить храм для удовлетворения своих религиозных потребностей, не имея на это однако необходимые средства, и вынужденных в силу этого проводить постоянно сбор пожертвований.

Το 1843, οι κάτοικοι της περιοχής αποφάσισαν να οικοδομήσουν ναό για να καλύψουν τις λατρευτικές τους ανάγκες, χωρίς όμως να έχουν τους απαραίτητους πόρους, με αποτέλεσμα να διενεργούν συνεχώς εράνους.

Так, в Афинах Библии подлежали конфискации.

Στην Αθήνα, λόγου χάρη, κατασχέθηκαν Γραφές.

Согласно одной из версий, вероятно для нападения на Афины с восточного побережья Аттики, персидская кавалерия переправилась туда на кораблях, поскольку таким образом можно было сразу захватить город после победы у Марафона, в которой персы были почти уверены.

Σύμφωνα με μια θεωρία, το περσικό ιππικό είχε επιβιβαστεί στα πλοία για μια πιθανή επίθεση στην Αθήνα από την ανατολική ακτή της Αττικής, έτσι ώστε να μπορέσει να καταλάβει την πόλη αμέσως μετά τη σχεδόν βέβαιη νίκη στο Μαραθώνα.

XXVIII Олимпийские игры — так официально называется Олимпиада-2004 — состоятся в Афинах с 13 по 29 августа.

Η 28η Ολυμπιάδα, όπως αποκαλούνται επίσημα οι Ολυμπιακοί Αγώνες του 2004, έχει προγραμματιστεί να λάβει χώρα στην Αθήνα από τις 13 ως τις 29 Αυγούστου.

|

Athens Αθήνα |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city |

|

|

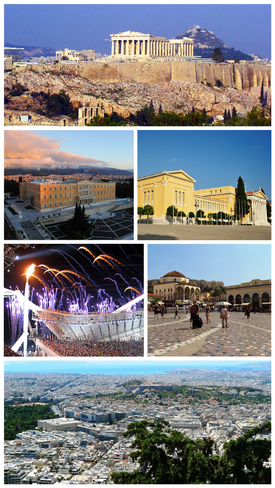

Clockwise from top: Acropolis of Athens, Zappeion Hall, Monastiraki, Aerial view from Lycabettus, Athens Olympic Sports Complex, and Hellenic Parliament |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nicknames:

τὸ κλεινὸν ἄστυ, tò kleinòn ásty («the glorious city») |

|

|

Athens Location within Greece Athens Location within Europe Athens Athens (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 37°59′03″N 23°43′41″E / 37.98417°N 23.72806°ECoordinates: 37°59′03″N 23°43′41″E / 37.98417°N 23.72806°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Geographic region | Central Greece |

| Administrative region | Attica |

| Regional unit | Central Athens |

| Districts | 7 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Mayor | Kostas Bakoyannis (New Democracy) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 38.964 km2 (15.044 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 412 km2 (159 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,928.717 km2 (1,130.784 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 338 m (1,109 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 70.1 m (230.0 ft) |

| Population

(2021)[3] |

|

| • Municipality | 637,798 |

| • Rank | 1st urban, 1st metro in Greece |

| • Urban | 3,041,131 |

| • Urban density | 7,400/km2 (19,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,722,544 |

| • Metro density | 1,300/km2 (3,300/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Athenian |

| GDP PPP (2016)

[4] |

|

| • Total | US$102,446 billion |

| • Per capita | US$ 32,461 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes |

10x xx, 11x xx, 120 xx |

| Telephone | 21 |

| Vehicle registration | Yxx, Zxx, Ixx |

| Patron saint | Dionysius the Areopagite (3 October) |

| Major airport(s) | Athens International Airport |

| Website | cityofathens.gr |

Athens ( ATH-inz;[5] Greek: Αθήνα, romanized: Athína [aˈθina] (listen); Ancient Greek: Ἀθῆναι, romanized: Athênai (pl.) [atʰɛ̂ːnai̯]) is a coastal city in the Mediterranean and is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates and is the capital of the Attica region and is one of the world’s oldest cities, with its recorded history spanning over 3,400 years[6] and its earliest human presence beginning somewhere between the 11th and 7th millennia BC.[7]

Classical Athens was a powerful city-state. It was a centre for the arts, learning and philosophy, and the home of Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum.[8][9] It is widely referred to as the cradle of Western civilization and the birthplace of democracy,[10][11] largely because of its cultural and political influence on the European continent—particularly Ancient Rome.[12] In modern times, Athens is a large cosmopolitan metropolis and central to economic, financial, industrial, maritime, political and cultural life in Greece. In 2021, Athens’ urban area hosted more than three and a half million people, which is around 35% of the entire population of Greece.[citation needed]

Athens is a Beta-status global city according to the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,[13] and is one of the biggest economic centers in Southeastern Europe. It also has a large financial sector, and its port Piraeus is both the largest passenger port in Europe,[14][15] and the third largest in the world.[16]

The Municipality of Athens (also City of Athens), which actually constitutes a small administrative unit of the entire city, had a population of 637,798 (in 2021)[3] within its official limits, and a land area of 38.96 km2 (15.04 sq mi).[17][18] The Athens Metropolitan Area or Greater Athens[19] extends beyond its administrative municipal city limits, with a population of 3,722,544 (in 2021)[3] over an area of 412 km2 (159 sq mi).[18] Athens is also the southernmost capital on the European mainland and the warmest major city in continental Europe with an average annual temperature of up to 19.8 °C (67.6 °F) locally.[20]

The heritage of the Classical Era is still evident in the city, represented by ancient monuments, and works of art, the most famous of all being the Parthenon, considered a key landmark of early Western civilization. The city also retains Roman, Byzantine and a smaller number of Ottoman monuments, while its historical urban core features elements of continuity through its millennia of history. Athens is home to two UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the Acropolis of Athens and the medieval Daphni Monastery. Landmarks of the modern era, dating back to the establishment of Athens as the capital of the independent Greek state in 1834, include the Hellenic Parliament and the so-called «Architectural Trilogy of Athens», consisting of the National Library of Greece, the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and the Academy of Athens. Athens is also home to several museums and cultural institutions, such as the National Archeological Museum, featuring the world’s largest collection of ancient Greek antiquities, the Acropolis Museum, the Museum of Cycladic Art, the Benaki Museum, and the Byzantine and Christian Museum. Athens was the host city of the first modern-day Olympic Games in 1896, and 108 years later it hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics, making it one of the few cities to have hosted the Olympics more than once.[21] Athens joined the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities in 2016.

Etymology and names[edit]

In Ancient Greek, the name of the city was Ἀθῆναι (Athênai, pronounced [atʰɛ̂ːnai̯] in Classical Attic) a plural. In earlier Greek, such as Homeric Greek, the name had been current in the singular form though, as Ἀθήνη (Athḗnē).[22] It was possibly rendered in the plural later on, like those of Θῆβαι (Thêbai) and Μυκῆναι (Μukênai). The root of the word is probably not of Greek or Indo-European origin,[23] and is possibly a remnant of the Pre-Greek substrate of Attica.[23] In antiquity, it was debated whether Athens took its name from its patron goddess Athena (Attic Ἀθηνᾶ, Athēnâ, Ionic Ἀθήνη, Athḗnē, and Doric Ἀθάνα, Athā́nā) or Athena took her name from the city.[24] Modern scholars now generally agree that the goddess takes her name from the city,[24] because the ending —ene is common in names of locations, but rare for personal names.[24]

According to the ancient Athenian founding myth, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, competed against Poseidon, the God of the Seas, for patronage of the yet-unnamed city;[25] they agreed that whoever gave the Athenians the better gift would become their patron[25] and appointed Cecrops, the king of Athens, as the judge.[25] According to the account given by Pseudo-Apollodorus, Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and a salt water spring welled up.[25] In an alternative version of the myth from Vergil’s poem Georgics, Poseidon instead gave the Athenians the first horse.[25] In both versions, Athena offered the Athenians the first domesticated olive tree.[25][26] Cecrops accepted this gift[25] and declared Athena the patron goddess of Athens.[25][26] Eight different etymologies, now commonly rejected, have been proposed since the 17th century. Christian Lobeck proposed as the root of the name the word ἄθος (áthos) or ἄνθος (ánthos) meaning «flower», to denote Athens as the «flowering city». Ludwig von Döderlein proposed the stem of the verb θάω, stem θη- (tháō, thē-, «to suck») to denote Athens as having fertile soil.[27] Athenians were called cicada-wearers (Ancient Greek: Τεττιγοφόροι) because they used to wear pins of golden cicadas. A symbol of being autochthonous (earth-born), because the legendary founder of Athens, Erechtheus was an autochthon or of being musicians, because the cicada is a «musician» insect.[28] In classical literature, the city was sometimes referred to as the City of the Violet Crown, first documented in Pindar’s ἰοστέφανοι Ἀθᾶναι (iostéphanoi Athânai), or as τὸ κλεινὸν ἄστυ (tò kleinòn ásty, «the glorious city»).

During the medieval period, the name of the city was rendered once again in the singular as Ἀθήνα. Variant names included Setines, Satine, and Astines, all derivations involving false splitting of prepositional phrases.[29] King Alphonse X of Castile gives the pseudo-etymology ‘the one without death/ignorance’.[30][page needed] In Ottoman Turkish, it was called آتينا Ātīnā,[31] and in modern Turkish, it is Atina.

After the establishment of the modern Greek state, and partly due to the conservatism of the written language, Ἀθῆναι [aˈθine] again became the official name of the city and remained so until the abandonment of Katharevousa in the 1970s, when Ἀθήνα, Athína, became the official name.[citation needed] Today, it is often simply called η πρωτεύουσα ī protévousa; ‘the capital’.

History[edit]

The oldest known human presence in Athens is the Cave of Schist, which has been dated to between the 11th and 7th millennia BC.[7] Athens has been continuously inhabited for at least 5,000 years (3000 BC).[32][33] By 1400 BC, the settlement had become an important centre of the Mycenaean civilization, and the Acropolis was the site of a major Mycenaean fortress, whose remains can be recognised from sections of the characteristic Cyclopean walls.[34] Unlike other Mycenaean centers, such as Mycenae and Pylos, it is not known whether Athens suffered destruction in about 1200 BC, an event often attributed to a Dorian invasion, and the Athenians always maintained that they were pure Ionians with no Dorian element. However, Athens, like many other Bronze Age settlements, went into economic decline for around 150 years afterwards.[citation needed]

Iron Age burials, in the Kerameikos and other locations, are often richly provided for and demonstrate that from 900 BC onwards Athens was one of the leading centres of trade and prosperity in the region.[35] The leading position of Athens may well have resulted from its central location in the Greek world, its secure stronghold on the Acropolis and its access to the sea, which gave it a natural advantage over inland rivals such as Thebes and Sparta.[citation needed]

By the sixth century BC, widespread social unrest led to the reforms of Solon. These would pave the way for the eventual introduction of democracy by Cleisthenes in 508 BC. Athens had by this time become a significant naval power with a large fleet, and helped the rebellion of the Ionian cities against Persian rule. In the ensuing Greco-Persian Wars Athens, together with Sparta, led the coalition of Greek states that would eventually repel the Persians, defeating them decisively at Marathon in 490 BC, and crucially at Salamis in 480 BC. However, this did not prevent Athens from being captured and sacked twice by the Persians within one year, after a heroic but ultimately failed resistance at Thermopylae by Spartans and other Greeks led by King Leonidas,[36] after both Boeotia and Attica fell to the Persians.

The decades that followed became known as the Golden Age of Athenian democracy, during which time Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece, with its cultural achievements laying the foundations for Western civilization.[citation needed] The playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides flourished in Athens during this time, as did the historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the physician Hippocrates, and the philosopher Socrates. Guided by Pericles, who promoted the arts and fostered democracy, Athens embarked on an ambitious building program that saw the construction of the Acropolis of Athens (including the Parthenon), as well as empire-building via the Delian League. Originally intended as an association of Greek city-states to continue the fight against the Persians, the league soon turned into a vehicle for Athens’s own imperial ambitions. The resulting tensions brought about the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), in which Athens was defeated by its rival Sparta.[citation needed]

By the mid-4th century BC, the northern Greek kingdom of Macedon was becoming dominant in Athenian affairs. In 338 BC the armies of Philip II defeated an alliance of some of the Greek city-states including Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea, effectively ending Athenian independence. Later, under Rome, Athens was given the status of a free city because of its widely admired schools. In the second century AD, The Roman emperor Hadrian, himself an Athenian citizen,[37] ordered the construction of a library, a gymnasium, an aqueduct which is still in use, several temples and sanctuaries, a bridge and financed the completion of the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

By the end of Late Antiquity, Athens had shrunk due to sacks by the Herulians, Visigoths, and Early Slavs which caused massive destruction in the city. In this era, the first Christian churches were built in Athens, and the Parthenon and other temples were converted into churches.[citation needed] Athens expanded its settlement in the second half of the Middle Byzantine Period, in the ninth to tenth centuries AD, and was relatively prosperous during the Crusades, benefiting from Italian trade. After the Fourth Crusade the Duchy of Athens was established. In 1458, it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire and entered a long period of decline.[citation needed]

Following the Greek War of Independence and the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, Athens was chosen as the capital of the newly independent Greek state in 1834, largely because of historical and sentimental reasons. At the time, after the extensive destruction it had suffered during the war of independence, it was reduced to a town of about 4,000 people (less than half its earlier population) in a loose swarm of houses along the foot of the Acropolis. The first King of Greece, Otto of Bavaria, commissioned the architects Stamatios Kleanthis and Eduard Schaubert to design a modern city plan fit for the capital of a state.[citation needed]

The first modern city plan consisted of a triangle defined by the Acropolis, the ancient cemetery of Kerameikos and the new palace of the Bavarian king (now housing the Greek Parliament), so as to highlight the continuity between modern and ancient Athens. Neoclassicism, the international style of this epoch, was the architectural style through which Bavarian, French and Greek architects such as Hansen, Klenze, Boulanger or Kaftantzoglou designed the first important public buildings of the new capital.[citation needed] In 1896, Athens hosted the first modern Olympic Games. During the 1920s a number of Greek refugees, expelled from Asia Minor after the Greco-Turkish War and Greek genocide, swelled Athens’s population; nevertheless it was most particularly following World War II, and from the 1950s and 1960s, that the population of the city exploded, and Athens experienced a gradual expansion.

In the 1980s it became evident that smog from factories and an ever-increasing fleet of automobiles, as well as a lack of adequate free space due to congestion, had evolved into the city’s most important challenge. A series of anti-pollution measures taken by the city’s authorities in the 1990s, combined with a substantial improvement of the city’s infrastructure (including the Attiki Odos motorway, the expansion of the Athens Metro, and the new Athens International Airport), considerably alleviated pollution and transformed Athens into a much more functional city. In 2004, Athens hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics.

-

Tondo of the Aison Cup, showing the victory of Theseus over the Minotaur in the presence of Athena. Theseus was responsible, according to the myth, for the synoikismos («dwelling together»)—the political unification of Attica under Athens.

-

The earliest coinage of Athens, c. 545–525/15 BC

-

-

Temporary accommodation for the Greek refugees from Asia Minor in tents in Thiseio. After the Asia Minor Catastrophe in 1922 thousands of families settled in Athens and the population of the city doubled.

Geography[edit]

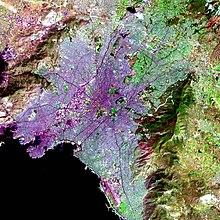

Athens sprawls across the central plain of Attica that is often referred to as the Athens Basin or the Attica Basin (Greek: Λεκανοπέδιο Αθηνών/Αττικής). The basin is bounded by four large mountains: Mount Aigaleo to the west, Mount Parnitha to the north, Mount Pentelicus to the northeast and Mount Hymettus to the east.[38] Beyond Mount Aegaleo lies the Thriasian plain, which forms an extension of the central plain to the west. The Saronic Gulf lies to the southwest. Mount Parnitha is the tallest of the four mountains (1,413 m (4,636 ft)),[39] and has been declared a national park. The Athens urban area spreads over 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Agios Stefanos in the north to Varkiza in the south. The city is located in the north temperate zone, 38 degrees north of the equator.

Athens is built around a number of hills. Lycabettus is one of the tallest hills of the city proper and provides a view of the entire Attica Basin. The meteorology of Athens is deemed to be one of the most complex in the world because its mountains cause a temperature inversion phenomenon which, along with the Greek government’s difficulties controlling industrial pollution, was responsible for the air pollution problems the city has faced.[33] This issue is not unique to Athens; for instance, Los Angeles and Mexico City also suffer from similar atmospheric inversion problems.[33]

The Cephissus river, the Ilisos and the Eridanos stream are the historical rivers of Athens.

Environment[edit]

By the late 1970s, the pollution of Athens had become so destructive that according to the then Greek Minister of Culture, Constantine Trypanis, «…the carved details on the five the caryatids of the Erechtheum had seriously degenerated, while the face of the horseman on the Parthenon’s west side was all but obliterated.»[40] A series of measures taken by the authorities of the city throughout the 1990s resulted in the improvement of air quality; the appearance of smog (or nefos as the Athenians used to call it) has become less common.

Measures taken by the Greek authorities throughout the 1990s have improved the quality of air over the Attica Basin. Nevertheless, air pollution still remains an issue for Athens, particularly during the hottest summer days. In late June 2007,[41] the Attica region experienced a number of brush fires,[41] including a blaze that burned a significant portion of a large forested national park in Mount Parnitha,[42] considered critical to maintaining a better air quality in Athens all year round.[41] Damage to the park has led to worries over a stalling in the improvement of air quality in the city.[41]

The major waste management efforts undertaken in the last decade (particularly the plant built on the small island of Psytalia) have greatly improved water quality in the Saronic Gulf, and the coastal waters of Athens are now accessible again to swimmers.

Safety[edit]

Athens ranks in the lowest percentage for the risk on frequency and severity of terrorist attacks according to the EU Global Terrorism Database (EIU 2007–2016 calculations). The city also ranked 35th in Digital Security, 21st on Health Security, 29th on Infrastructure Security and 41st on Personal Security globally in a 2017 The Economist Intelligence Unit report.[43] It also ranks as a very safe city (39th globally out of 162 cities overall) on the ranking of the safest and most dangerous countries.[44] As May 2022 the crime index from Numbeo places Athens at 56.33 (moderate), while its safety index is at 43.68.[1][45] According to a Mercer 2019 Quality of Living Survey, Athens ranks 89th on the Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranking.[46]

Climate[edit]

Athens has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa). Athens is the hottest city in mainland Europe

[47][48] and according to the Hellenic National Meteorological Service the Athens Basin is also the warmest area of Greece with an average annual temperature of 19.8 °C (67.6 °F).[20] The dominant feature of Athens’ climate is alternation between prolonged hot and dry summers and mild, wetter winters with moderate rainfall.[49] With an average of 433 millimetres (17.0 in) of yearly precipitation, rainfall occurs largely between the months of October and April. July and August are the driest months when thunderstorms occur sparsely. Furthermore, some coastal areas such as Piraeus in the Athens Riviera, have a hot semi-arid climate (BSh) according to the climate atlas published by the Hellenic National Meteorological Service.[50] However, places like Elliniko, which are classified as hot semi-arid (BSh) because of the low annual rainfall, have not recorded temperatures as high as other places in the city. This occurs due to the moderating influence of the sea, and lower levels of industrialisation compared to other regions of the city.[citation needed]

Owing to the rain shadow of the Pindus Mountains, annual precipitation of Athens is lower than most other parts of Greece, especially western Greece. As an example, Ioannina receives around 1,300 mm (51 in) per year, and Agrinio around 800 mm (31 in) per year. Daily average highs for July have been measured around 34 °C or 93 °F in downtown Athens, but some parts of the city may be even hotter for the higher density of buildings, and the lower density of vegetation, such as the center,[51] in particular, western areas due to a combination of industrialization and a number of natural factors, knowledge of which has existed since the mid-19th century.[52][53][54] Due to the large area covered by Athens Metropolitan Area, there are notable climatic differences between parts of the urban conglomeration. The northern suburbs tend to be wetter and cooler in winter, whereas the southern suburbs are some of the driest locations in Greece and record very high minimum temperatures in summer. Heavy snow fell in the Greater Athens area and Athens itself between 14–17 February 2021, when snow blanketed the entire city and its suburbs from the north to the furthest south, coastal suburbs,[55] with depth ranges up to 25 centimetres (9.8 in) in Central Athens.,[56][57] and with even the Acropolis of Athens completely covered with snow.[58] The National Meteorological Service (EMY) described it was one of the most intense snow storms over the past 40 years.[56] Heavy snow was also reported in Athens on January 24, 2022, with 40 centimetres (16 in) reported locally in the higher elevations.[59]

Snowfall in Athens on 16 February 2021

Athens is affected by the urban heat island effect in some areas which is caused by human activity,[60][61] altering its temperatures compared to the surrounding rural areas,[62][63][64][65] and leaving detrimental effects on energy usage, expenditure for cooling,[66][67] and health.[61] The urban heat island of the city has also been found to be partially responsible for alterations of the climatological temperature time-series of specific Athens meteorological stations, because of its effect on the temperatures and the temperature trends recorded by some meteorological stations.[68][69][70][71][72] On the other hand, specific meteorological stations, such as the National Garden station and Thiseio meteorological station, are less affected or do not experience the urban heat island.[62][73]

Athens holds the official World Meteorological Organization record for the highest temperature ever recorded in Europe, at 48 °C (118.4 °F), which was recorded in the Elefsina and Tatoi suburbs of Athens on 10 July 1977.[74] Furthermore, Metropolitan Athens has experienced temperatures of 47.5°C and over in four different locations.

| Climate data for Downtown Athens (1991–2020), Extremes (1890–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

44.8 (112.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

43.9 (111.0) |

38.7 (101.7) |

36.5 (97.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

44.8 (112.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16 (61) |

15.5 (59.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 55.6 (2.19) |

44.4 (1.75) |

45.6 (1.80) |

27.6 (1.09) |

20.7 (0.81) |

11.6 (0.46) |

10.7 (0.42) |

5.4 (0.21) |

25.8 (1.02) |

38.6 (1.52) |

70.8 (2.79) |

76.3 (3.00) |

433.1 (17.06) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.0 | 70.0 | 66.0 | 60.0 | 56.0 | 50.0 | 42.0 | 47.0 | 57.0 | 66.0 | 72.0 | 73.0 | 60.9 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: Cosmos, scientific magazine of the National Observatory of Athens[75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteoclub[76][77] |

| Climate data for Elliniko, Athens (1955–2010), Extremes (1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.6 (96.1) |

40.0 (104.0) |

42.0 (107.6) |

43.0 (109.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

35.2 (95.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 47.7 (1.88) |

38.5 (1.52) |

42.3 (1.67) |

25.5 (1.00) |

14.3 (0.56) |

5.4 (0.21) |

6.3 (0.25) |

6.2 (0.24) |

12.3 (0.48) |

45.9 (1.81) |

60.1 (2.37) |

62.0 (2.44) |

366.5 (14.43) |

| Average rainy days | 12.9 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 13.5 | 95.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.3 | 68.0 | 65.9 | 62.2 | 58.2 | 51.8 | 46.6 | 46.8 | 54.0 | 62.6 | 69.2 | 70.4 | 60.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.2 | 134.4 | 182.9 | 231.0 | 291.4 | 336.0 | 362.7 | 341.0 | 276.0 | 207.7 | 153.0 | 127.1 | 2,773.4 |

| Source 1: HNMS (1955–2010 normals)[78] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (Extremes 1961–1990),[79] Info Climat (Extremes 1991–present)[80][81] |

| Climate data for Nea Filadelfia, Athens (1955–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.6 (54.7) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

31.4 (88.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.1 (57.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.9 (2.12) |

43.0 (1.69) |

41.8 (1.65) |

28.5 (1.12) |

20.5 (0.81) |

9.1 (0.36) |

7.0 (0.28) |

6.7 (0.26) |

19.4 (0.76) |

48.8 (1.92) |

61.9 (2.44) |

71.2 (2.80) |

411.8 (16.21) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.0 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 8.3 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 4.1 | 7.4 | 10.1 | 12.5 | 87.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.4 | 72.0 | 68.4 | 61.7 | 53.4 | 45.7 | 42.9 | 45.4 | 54.6 | 66.1 | 74.5 | 76.2 | 61.3 |

| Source: HNMS[82] |

Locations[edit]

Neighbourhoods of the center of Athens (Municipality of Athens)[edit]

The Municipality of Athens, the City Centre of the Athens Urban Area, is divided into several districts: Omonoia, Syntagma, Exarcheia, Agios Nikolaos, Neapolis, Lykavittos, Lofos Strefi, Lofos Finopoulou, Lofos Filopappou, Pedion Areos, Metaxourgeio, Aghios Kostantinos, Larissa Station, Kerameikos, Psiri, Monastiraki, Gazi, Thission, Kapnikarea, Aghia Irini, Aerides, Anafiotika, Plaka, Acropolis, Pnyka, Makrygianni, Lofos Ardittou, Zappeion, Aghios Spyridon, Pangrati, Kolonaki, Dexameni, Evaggelismos, Gouva, Aghios Ioannis, Neos Kosmos, Koukaki, Kynosargous, Fix, Ano Petralona, Kato Petralona, Rouf, Votanikos, Profitis Daniil, Akadimia Platonos, Kolonos, Kolokynthou, Attikis Square, Lofos Skouze, Sepolia, Kypseli, Aghios Meletios, Nea Kypseli, Gyzi, Polygono, Ampelokipoi, Panormou-Gerokomeio, Pentagono, Ellinorosson, Nea Filothei, Ano Kypseli, Tourkovounia-Lofos Patatsou, Lofos Elikonos, Koliatsou, Thymarakia, Kato Patisia, Treis Gefyres, Aghios Eleftherios, Ano Patisia, Kypriadou, Menidi, Prompona, Aghios Panteleimonas, Pangrati, Goudi, Vyronas and Ilisia.

- Omonoia, Omonoia Square, (Greek: Πλατεία Ομονοίας) is the oldest square in Athens. It is surrounded by hotels and fast food outlets, and contains a metro station, named Omonia station. The square is the focus for celebration of sporting victories, as seen after the country’s winning of the Euro 2004 and the EuroBasket 2005 tournaments.

- Metaxourgeio (Greek: Μεταξουργείο) is a neighborhood of Athens. The neighborhood is located north of the historical centre of Athens, between Kolonos to the east and Kerameikos to the west, and north of Gazi. Metaxourgeio is frequently described as a transition neighborhood. After a long period of abandonment in the late 20th century, the area is acquiring a reputation as an artistic and fashionable neighborhood following the opening of art galleries, museums, restaurants and cafés. [1] Local efforts to beautify and invigorate the neighborhood have reinforced a sense of community and artistic expression. Anonymous art pieces containing quotes and statements in both English and Ancient Greek have sprung up throughout the neighborhood, bearing statements such as «Art for art’s sake» (Τέχνη τέχνης χάριν). Guerrilla gardening has also helped to beautify the area.

- Psiri – The reviving Psiri (Greek: Ψυρρή) neighbourhood – also known as Athens’s «meat packing district» – is dotted with renovated former mansions, artists’ spaces, and small gallery areas. A number of its renovated buildings also host fashionable bars, making it a hotspot for the city in the last decade, while live music restaurants known as «rebetadika», after rebetiko, a unique form of music that blossomed in Syros and Athens from the 1920s until the 1960s, are to be found. Rebetiko is admired by many, and as a result rebetadika are often crammed with people of all ages who will sing, dance and drink till dawn.

- The Gazi (Greek: Γκάζι) area, one of the latest in full redevelopment, is located around a historic gas factory, now converted into the Technopolis cultural multiplex, and also includes artists’ areas, active nightlife and night clubs, small clubs, cafeterias, bars and restaurants, as well as Athens’s «Gay village».[83] The metro’s expansion to the western suburbs of the city has brought easier access to the area since spring 2007, as the line 3 now stops at Gazi (Kerameikos station).

- Syntagma, Syntagma Square, (Greek: Σύνταγμα/Constitution Square), is the capital’s central and largest square, lying adjacent to the Greek Parliament (the former Royal Palace) and the city’s most notable hotels. Ermou Street, an approximately one-kilometre-long (5⁄8-mile) pedestrian road connecting Syntagma Square to Monastiraki, is a consumer paradise for both Athenians and tourists. Complete with fashion shops and shopping centres promoting most international brands, it now finds itself in the top five most expensive shopping streets in Europe, and the tenth most expensive retail street in the world.[84] Nearby, the renovated Army Fund building in Panepistimiou Street includes the «Attica» department store and several upmarket designer stores.

Neoclassical houses in the historical neighbourhood of Plaka.

- Plaka, Monastiraki, and Thission – Plaka (Greek: Πλάκα), lying just beneath the Acropolis, is famous for its plentiful neoclassical architecture, making up one of the most scenic districts of the city. It remains a prime tourist destination with tavernas, live performances and street salesmen. Nearby Monastiraki (Greek: Μοναστηράκι), for its part, is known for its string of small shops and markets, as well as its crowded flea market and tavernas specialising in souvlaki. Another district known for its student-crammed, stylish cafés is Theseum or Thission (Greek: Θησείο), lying just west of Monastiraki. Thission is home to the ancient Temple of Hephaestus, standing atop a small hill. This area also has a picturesque 11th-century Byzantine church, as well as a 15th-century Ottoman mosque.

- Exarcheia (Greek: Εξάρχεια), located north of Kolonaki, often regarded as the city’s anarchist scene and as a student quarter with night clubs, cafés, bars and bookshops.[85] Exarcheia is home to the Athens Polytechnic and the National Archaeological Museum; it also contains important buildings of several 20th-century styles: Neoclassicism, Art Deco and Early Modernism (including Bauhaus influences).[citation needed]

- Kolonaki (Greek: Κολωνάκι) is the area at the base of Lycabettus hill, full of boutiques catering to well-heeled customers by day, and bars and more fashionable restaurants by night, with galleries and museums.[86] This is often regarded as one of the more prestigious areas of the capital.

Parks and zoos[edit]

Parnitha National Park is punctuated by well-marked paths, gorges, springs, torrents and caves dotting the protected area. Hiking and mountain-biking in all four mountains are popular outdoor activities for residents of the city. The National Garden of Athens was completed in 1840 and is a green refuge of 15.5 hectares in the centre of the Greek capital. It is to be found between the Parliament and Zappeion buildings, the latter of which maintains its own garden of seven hectares.

Parts of the City Centre have been redeveloped under a masterplan called the Unification of Archeological Sites of Athens, which has also gathered funding from the EU to help enhance the project.[87][88] The landmark Dionysiou Areopagitou Street has been pedestrianised, forming a scenic route. The route starts from the Temple of Olympian Zeus at Vasilissis Olgas Avenue, continues under the southern slopes of the Acropolis near Plaka, and finishes just beyond the Temple of Hephaestus in Thiseio. The route in its entirety provides visitors with views of the Parthenon and the Agora (the meeting point of ancient Athenians), away from the busy City Centre.

The hills of Athens also provide green space. Lycabettus, Philopappos hill and the area around it, including Pnyx and Ardettos hill, are planted with pines and other trees, with the character of a small forest rather than typical metropolitan parkland. Also to be found is the Pedion tou Areos (Field of Mars) of 27.7 hectares, near the National Archaeological Museum.

Athens’ largest zoo is the Attica Zoological Park, a 20-hectare (49-acre) private zoo located in the suburb of Spata. The zoo is home to around 2000 animals representing 400 species, and is open 365 days a year. Smaller zoos exist within public gardens or parks, such as the zoo within the National Garden of Athens.

Urban and suburban municipalities[edit]

Beach in the southern suburb of Alimos, one of the many beaches in the southern coast of Athens

The Athens Metropolitan Area consists of 58[89] densely populated municipalities, sprawling around the Municipality of Athens (the City Centre) in virtually all directions. For the Athenians, all the urban municipalities surrounding the City Centre are called suburbs. According to their geographic location in relation to the City of Athens, the suburbs are divided into four zones; the northern suburbs (including Agios Stefanos, Dionysos, Ekali, Nea Erythraia, Kifissia, Kryoneri, Maroussi, Pefki, Lykovrysi, Metamorfosi, Nea Ionia, Nea Filadelfeia, Irakleio, Vrilissia, Melissia, Penteli, Chalandri, Agia Paraskevi, Gerakas, Pallini, Galatsi, Psychiko and Filothei); the southern suburbs (including Alimos, Nea Smyrni, Moschato, Tavros, Agios Ioannis Rentis, Kallithea, Piraeus, Agios Dimitrios, Palaio Faliro, Elliniko, Glyfada, Lagonisi, Saronida, Argyroupoli, Ilioupoli, Varkiza, Voula, Vari and Vouliagmeni); the eastern suburbs (including Zografou, Dafni, Vyronas, Kaisariani, Cholargos and Papagou); and the western suburbs (including Peristeri, Ilion, Egaleo, Koridallos, Agia Varvara, Keratsini, Perama, Nikaia, Drapetsona, Chaidari, Petroupoli, Agioi Anargyroi, Ano Liosia, Aspropyrgos, Eleusina, Acharnes and Kamatero).

The Athens city coastline, extending from the major commercial port of Piraeus to the southernmost suburb of Varkiza for some 25 km (20 mi),[90] is also connected to the City Centre by tram.

In the northern suburb of Maroussi, the upgraded main Olympic Complex (known by its Greek acronym OAKA) dominates the skyline. The area has been redeveloped according to a design by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, with steel arches, landscaped gardens, fountains, futuristic glass, and a landmark new blue glass roof which was added to the main stadium. A second Olympic complex, next to the sea at the beach of Palaio Faliro, also features modern stadia, shops and an elevated esplanade. Work is underway to transform the grounds of the old Athens Airport – named Elliniko – in the southern suburbs, into one of the largest landscaped parks in Europe, to be named the Hellenikon Metropolitan Park.[91]

Many of the southern suburbs (such as Alimos, Palaio Faliro, Elliniko, Glyfada, Voula, Vouliagmeni and Varkiza) known as the Athens Riviera, host a number of sandy beaches, most of which are operated by the Greek National Tourism Organisation and require an entrance fee. Casinos operate on both Mount Parnitha, some 25 km (16 mi)[92] from downtown Athens (accessible by car or cable car), and the nearby town of Loutraki (accessible by car via the Athens – Corinth National Highway, or the Athens Suburban Railway).

Administration[edit]

The large City Centre (Greek: Κέντρο της Αθήνας) of the Greek capital falls directly within the Municipality of Athens or Athens Municipality (Greek: Δήμος Αθηναίων)—also City of Athens. Athens Municipality is the largest in population size in Greece. Piraeus also forms a significant city centre on its own,[93] within the Athens Urban Area and it is the second largest in population size within it.

Athens Urban Area[edit]

The Athens Urban Area (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Αθηνών), also known as Urban Area of the Capital (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Πρωτεύουσας) or Greater Athens (Greek: Ευρύτερη Αθήνα),[94] today consists of 40 municipalities, 35 of which make up what was referred to as the former Athens Prefecture municipalities, located within 4 regional units (North Athens, West Athens, Central Athens, South Athens); and a further 5 municipalities, which make up the former Piraeus Prefecture municipalities, located within the regional unit of Piraeus as mentioned above.

The Athens Municipality forms the core and center of Greater Athens, which in its turn consists of the Athens Municipality and 40 more municipalities, divided in four regional units (Central, North, South and West Athens), accounting for 2,597,935 people (in 2021)[3] within an area of 361 km2 (139 sq mi).[18] Until 2010, which made up the abolished Athens Prefecture and the municipality of Piraeus, the historic Athenian port, with 4 other municipalities make up the regional unit of Piraeus.

The regional units of Central Athens, North Athens, South Athens, West Athens and Piraeus with part of East[95] and West Attica[96] regional units combined make up the continuous Athens Urban Area,[96][97][98] also called the «Urban Area of the Capital» or simply «Athens» (the most common use of the term), spanning over 412 km2 (159 sq mi),[99] with a population of 3,041,131 people as of 2021. The Athens Urban Area is considered to form the city of Athens as a whole, despite its administrative divisions, which is the largest in Greece and one of the most populated urban areas in Europe.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Athens metropolitan area[edit]

The Athens metropolitan area spans 2,928.717 km2 (1,131 sq mi) within the Attica region and includes a total of 58 municipalities, which are organized in seven regional units (those outlined above, along with East Attica and West Attica), having reached a population of 3,722,544 according to the 2021 census.[3] Athens and Piraeus municipalities serve as the two metropolitan centres of the Athens Metropolitan Area.[100] There are also some inter-municipal centres serving specific areas. For example, Kifissia and Glyfada serve as inter-municipal centres for northern and southern suburbs respectively.

Demographics[edit]

The Athens Urban Area within the Attica Basin from space

Athens population distribution

Population in modern times[edit]

The seven districts of the Athens Municipality

The Municipality of Athens has an official population of 637,798 people (in 2021).[3] The four regional units that make up what is referred to as Greater Athens have a combined population of 2,597,935. They together with the regional unit of Piraeus (Greater Piraeus) make up the dense Athens Urban Area which reaches a total population of 3,041,131 inhabitants (in 2021).[3] According to Eurostat, in 2013 the functional urban area of Athens had 3,828,434 inhabitants, being apparently decreasing compared with the pre-economic crisis date of 2009 (4,164,175).[citation needed]

The municipality (Center) of Athens is the most populous in Greece, with a population of 637,798 people (in 2021)[3] and an area of 38.96 km2 (15.04 sq mi),[17] forming the core of the Athens Urban Area within the Attica Basin. The incumbent Mayor of Athens is Kostas Bakoyannis of New Democracy. The municipality is divided into seven municipal districts which are mainly used for administrative purposes.

As of the 2011 census, the population for each of the seven municipal districts of Athens is as follows:[101]

- 1st: 75,810

- 2nd: 103,004

- 3rd: 46,508

- 4th: 85,629

- 5th: 98,665

- 6th: 130,582

- 7th: 123,848

For the Athenians the most popular way of dividing the downtown is through its neighbourhoods such as Pagkrati, Ambelokipi, Goudi, Exarcheia, Patissia, Ilissia, Petralona, Plaka, Anafiotika, Koukaki, Kolonaki and Kypseli, each with its own distinct history and characteristics.

Population of the Athens Metropolitan Area[edit]

The Athens Metropolitan Area, with an area of 2,928.717 km2 (1,131 sq mi) and inhabited by 3,722,544 people in 2021,[3] consists of the Athens Urban Area with the addition of the towns and villages of East and West Attica, which surround the dense urban area of the Greek capital. It actually sprawls over the whole peninsula of Attica, which is the best part of the region of Attica, excluding the islands.

| Classification of regional units within Greater Athens, Athens Urban Area and Athens Metropolitan Area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional unit | Population (2021)[3] | |||

| Central Athens | 996,283 | Greater Athens 2,597,935 |

Athens Urban Area 3,041,131 |

Athens Metropolitan Area 3,722,544 |

| North Athens | 598,847 | |||

| South Athens | 526,996 | |||

| West Athens | 475,809 | |||

| Piraeus | 443,195 | Greater Piraeus 443,196 |

||

| East Attica | 516,549 | |||

| West Attica | 164,864 |

Population in ancient times[edit]

Mycenean Athens in 1600–1100 BC could have equalled the size of Tiryns, with an estimated population of up to 10,000–15,000.[102] During the Greek Dark Ages the population of Athens was around 4,000 people, rising to an estimated 10,000 by 700 BC.[citation needed]

During the Classical period, Athens denotes both the urban area of the city proper and its subject territory (the Athenian city-state) extending across most of the modern Attica region except the territory of the city-state of Megaris and the island section. In 500 BC the Athenian territory probably contained around 200,000 people. Thucydides indicates a fifth-century total of 150,000-350,000 and up to 610,000. A census ordered by Demetrius of Phalerum in 317 BC is said to have recorded 21,000 free citizens, 10,000 resident aliens and 400,000 slaves, a total population of 431,000,[103] but this figure is highly suspect because of the improbably high number of slaves and does not include free women and children and resident foreigners. An estimate based on Thucydides is 40,000 male citizens, 100,000 family members, 70,000 metics (resident foreigners) and 150,000-400,000 slaves, though modern historians again hesitate to take such high numbers at face value, most estimates now preferring a total in the 200–350,000 range.[citation needed] The urban area of Athens proper (excluding the port of Piraeus) covered less than a thousandth of the area of the city-state, though its population density was of course far higher: modern estimates for the population of the built-up area tend to indicate around 35–45,000 inhabitants, though density of occupation, household size and whether there was a significant suburban population beyond the walls remain uncertain.[citation needed]

The ancient site of the main city is centred on the rocky hill of the acropolis. Many towns existed in the Athenian territory. Acharnae, Afidnes, Cytherus, Colonus, Corydallus, Cropia, Decelea, Euonymos, Vravron among others were important towns in the Athenian countryside. The new port of Piraeus was located in the site between the passenger section of the modern port (named Kantharos in antiquity) and Pasalimani harbour (named Zea in antiquity). The old port (Phaliro) was in the site of modern Palaio Faliro and gradually declined after the construction of the new port, but remained as a minor port and important settlement with historic significance in late Classical times.

Modern Expansion

The rapid expansion of the modern city, which continues to this day, took off with industrial growth in the 1950s and 1960s.[104] The expansion is now particularly toward the East and North East (a tendency greatly related to the new Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport and the Attiki Odos, the freeway that cuts across Attica). By this process Athens has engulfed many former suburbs and villages in Attica, and continues to do so. The table below shows the historical population of Athens in recent times.

The metropolitan population reached a peak around 2006 and since then has stabilised and even dropped slightly at around 3.7 million.

| Year | Municipality population | Metro population |

|---|---|---|

| 1833 | 4,000[105] | – |

| 1870 | 44,500[105] | – |

| 1896 | 123,000[105] | – |

| 1921 (Pre-Population exchange) | 473,000[33] | – |

| 1923 (Post-Population exchange) | 718,000[105] | – |

| 1971 | 867,023 | 2,540,241[106] |

| 1981 | 885,737 | 3,369,443 |

| 1991 | 772,072 | 3,523,407[107] |

| 2001 | 745,514[108] | 3,761,810[108] |

| 2011 | 664,046 | 3,753,783[89] |

| 2021 | 637,798 | 3,722,544[3] |

Government and politics[edit]

Athens became the capital of Greece in 1834, following Nafplion, which was the provisional capital from 1829. The municipality (City) of Athens is also the capital of the Attica region. The term Athens can refer either to the Municipality of Athens, to Greater Athens or urban area, or to the entire Athens Metropolitan Area.

-

-

-

The Athens City Hall in Kotzia Square was designed by Panagiotis Kolkas and completed in 1874.[109]

-

International relations and influence[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Athens is twinned with:[110]

Partnerships[edit]

Other locations named after Athens[edit]

United States

- Athens, Alabama (pop. 24,234)

- Athens, Arkansas[122]

- Athens, California

- West Athens, California (pop. 9,101)

- Athens, Georgia (pop. 114,983)

- Athens, Illinois (pop. 1,726)

- New Athens, Illinois (pop. 2,620)

- New Athens Township, St. Clair County, Illinois (pop. 2,620)

- Athens, Indiana

- Athens, Kentucky

- Athens, Louisiana (pop. 262)

- Athens Township, Jewell County, Kansas (pop. 74)

- Athens, Maine (pop. 847)

- Athens, Michigan (pop. 1,111)

- Athens Township, Michigan (pop. 2,571)

- Athens, Minnesota

- Athens Township, Minnesota (pop. 2,322)

- Athens, Mississippi

- Athens (town), New York (pop. 3,991)

- Athens (village), New York (pop. 1,695)

- Athens, Ohio (pop. 21,909)

- Athens County, Ohio (pop. 62,223)

- Athens Township, Athens County, Ohio (pop. 27,714)

- Athens Township, Harrison County, Ohio (pop. 520)

- New Athens, Ohio (pop. 342)

- Athena, Oregon (pop. 1,270)

- Athens, Pennsylvania (pop. 3,415)

- Athens Township, Bradford County, Pennsylvania (pop. 5,058)

- Athens Township, Crawford County, Pennsylvania (pop. 775)

- Athens, Tennessee (pop. 13,220)

- Athens, Texas (pop. 11,297)

- Athens, Vermont (pop. 340)

- Athens, West Virginia (pop. 1,102)

- Athens, Wisconsin (pop. 1,095)

Economy[edit]

Athens is the financial capital of Greece. According to data from 2014, Athens as a metropolitan economic area produced US$130 billion as GDP in PPP, which consists of nearly half of the production for the whole country. Athens was ranked 102nd in that year’s list of global economic metropolises, while GDP per capita for the same year was 32,000 US-dollars.[124]

Athens is one of the major economic centres in south-eastern Europe and is considered a regional economic power. The port of Piraeus, where big investments by COSCO have already been delivered during the recent decade, the completion of the new Cargo Centre in Thriasion,[125] the expansion of the Athens Metro and the Athens Tram, as well as the Hellenikon metropolitan park redevelopment in Elliniko and other urban projects, are the economic landmarks of the upcoming years.

Prominent Greek companies such as Hellas Sat, Hellenic Aerospace Industry, Mytilineos Holdings, Titan Cement, Hellenic Petroleum, Papadopoulos E.J., Folli Follie, Jumbo S.A., OPAP, and Cosmote have their headquarters in the metropolitan area of Athens. Multinational companies such as Ericsson, Sony, Siemens, Motorola, Samsung, Microsoft, Novartis, Mondelez and Coca-Cola also have their regional research and development headquarters in the city.

The 28-storey Athens Tower was completed in 1971, and in a city often bound by low-rise regulations to ensure good views of the Acropolis, is Greece’s tallest.

The banking sector is represented by National Bank of Greece, Alpha Bank, Eurobank, and Piraeus Bank, while the Bank of Greece is also situated in the City Centre. The Athens Stock Exchange was severely hit by the Greek government-debt crisis and the decision of the government to proceed into capital controls during summer 2015. As a whole the economy of Athens and Greece was strongly affected, while data showed a change from long recession to growth of 1.4% from 2017 onwards.[126]

Tourism is also a leading contributor to the economy of the city, as one of Europe’s top destinations for city-break tourism, and also the gateway for excursions to both the islands and other parts of the mainland. Greece attracted 26.5 million visitors in 2015, 30.1 million visitors in 2017, and over 33 million in 2018, making Greece one of the most visited countries in Europe and the world, and contributing 18% to the country’s GDP. Athens welcomed more than 5 million tourists in 2018, and 1.4 million were «city-breakers»; this was an increase by over a million city-breakers since 2013.[127]

Transport[edit]

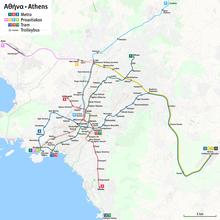

Athens railways network (Metro, Suburban Railway and Tram)

Athens is the country’s major transportation hub. The city has Greece’s largest airport and its largest port; Piraeus, too, is the largest container transport port in the Mediterranean, and the largest passenger port in Europe.

Athens is a major national hub for Intercity (Ktel) and international buses, as well as for domestic and international rail transport. Public transport is serviced by a variety of transportation means, making up the country’s largest mass transit system. The Athens Mass Transit System consists of a large bus and trolleybus fleet, the city’s Metro, a Suburban Railway service[128] and a tram network, connecting the southern suburbs to the city centre.[129]

Bus transport[edit]

OSY (Greek: ΟΣΥ) (Odikes Sygkoinonies S.A.), a subsidiary company of OASA (Athens urban transport organisation), is the main operator of buses and trolleybuses in Athens. As of 2017, its network consists of around 322 bus lines, spanning the Athens Metropolitan Area, and making up a fleet of 2,375 buses and trolleybuses. Of those 2,375, 619 buses run on compressed natural gas, making up the largest fleet of natural gas-powered buses in Europe, and 354 are electric-powered (trolleybuses). All of the 354 trolleybuses are equipped to run on diesel in case of power failure.[130]

International links are provided by a number of private companies. National and regional bus links are provided by KTEL from two InterCity Bus Terminals; Kifissos Bus Terminal A and Liosion Bus Terminal B, both located in the north-western part of the city. Kifissos provides connections towards Peloponnese, North Greece, West Greece and some Ionian Islands, whereas Liosion is used for most of Central Greece.

Athens Metro[edit]

The Athens Metro is operated by STASY S.A (Greek: ΣΤΑΣΥ) (Statheres Sygkoinonies S.A), a subsidiary company of OASA (Athens urban transport organisation), which provides public transport throughout the Athens Urban Area. While its main purpose is transport, it also houses Greek artifacts found during the construction of the system.[131] The Athens Metro runs three metro lines, namely Line 1 (Green Line), Line 2 (Red Line) and Line 3 (Blue Line) lines, of which the first was constructed in 1869, and the other two largely during the 1990s, with the initial new sections opened in January 2000. Line 1 mostly runs at ground level and the other two (Line 2 & 3) routes run entirely underground. A fleet of 42 trains, using 252 carriages, operates on the network,[132] with a daily occupancy of 1,353,000 passengers.[133]

Line 1 (Green Line) serves 24 stations, and is the oldest line of the Athens metro network. It runs from Piraeus station to Kifissia station and covers a distance of 25.6 km (15.9 mi). There are transfer connections with the Blue Line 3 at Monastiraki station and with the Red Line 2 at Omonia and Attiki stations.

Line 2 (Red Line) runs from Anthoupoli station to Elliniko station and covers a distance of 17.5 km (10.9 mi).[132] The line connects the western suburbs of Athens with the southeast suburbs, passing through the center of Athens. The Red Line has transfer connections with the Green Line 1 at Attiki and Omonia stations. There are also transfer connections with the Blue Line 3 at Syntagma station and with the tram at Syntagma, Syngrou Fix and Neos Kosmos stations.

Line 3 (Blue Line) runs from Nikaia station, through the central Monastiraki and Syntagma stations to Doukissis Plakentias avenue in the northeastern suburb of Halandri.[132] It then ascends to ground level and continues to Athens International Airport Eleftherios Venizelos using the suburban railway infrastructure, extending its total length to 39 km (24 mi).[132] The spring 2007 extension from Monastiraki westwards to Egaleo connected some of the main night life hubs of the city, namely those of Gazi (Kerameikos station) with Psirri (Monastiraki station) and the city centre (Syntagma station). Extensions are under construction to the western and southwestern suburbs of Athens, as far as the Port of Piraeus. The new stations will be Maniatika, Piraeus and Dimotiko Theatro, and the completed extension will be ready in 2022, connecting the biggest port of Greece, the Port of Piraeus, with Athens International Airport, the biggest airport of Greece.

Commuter/suburban rail (Proastiakos)[edit]

The Athens Suburban Railway, referred to as the Proastiakos, connects Athens International Airport to the city of Kiato, 106 km (66 mi)[134] west of Athens, via Larissa station, the city’s central rail station and the port of Piraeus. The length of Athens’s commuter rail network extends to 120 km (75 mi),[134] and is expected to stretch to 281 km (175 mi) by 2010.[134]

Tram[edit]

The Athens Tram is operated by STASY S.A (Statheres Sygkoinonies S.A), a subsidiary company of OASA (Athens urban transport organisation). It has a fleet of 35 Sirio type vehicles[135] which serve 48 stations,[135] employ 345 people with an average daily occupancy of 65,000 passengers.[135] The tram network spans a total length of 27 km (17 mi) and covers ten Athenian suburbs.[135] The network runs from Syntagma Square to the southwestern suburb of Palaio Faliro, where the line splits in two branches; the first runs along the Athens coastline toward the southern suburb of Voula, while the other heads toward Neo Faliro. The network covers the majority of the Athens coastline.[136] Further extension is under construction towards the major commercial port of Piraeus.[135] The expansion to Piraeus will include 12 new stations, increase the overall length of tram route by 5.4 km (3 mi), and increase the overall transportation network.[137]

Athens International Airport[edit]

Athens is served by the Athens International Airport (ATH), located near the town of Spata, in the eastern Messoghia plain, some 35 km (22 mi) east of center of Athens.[138] The airport, awarded the «European Airport of the Year 2004» Award,[139] is intended as an expandable hub for air travel in southeastern Europe and was constructed in 51 months, costing 2.2 billion euros. It employs a staff of 14,000.[139]

Railways and ferry connections[edit]

Athens is the hub of the country’s national railway system (OSE), connecting the capital with major cities across Greece and abroad (Istanbul, Sofia, Belgrade and Bucharest). The Port of Piraeus is the largest port in Greece and one of the largest in Europe.

Rafina and Lavrio act as alternative ports of Athens, connects the city with numerous Greek islands of the Aegean Sea, Evia and Çeşme in Turkey,[140][141] while also serving the cruise ships that arrive.

Motorways[edit]

View of Hymettus tangent (Periferiaki Imittou) from Kalogeros Hill

Two main motorways of Greece begin in Athens, namely the A1/E75, heading north towards Greece’s second largest city, Thessaloniki; and the border crossing of Evzones and the A8/E94 heading west, towards Greece’s third largest city, Patras, which incorporated the GR-8A. Before their completion much of the road traffic used the GR-1 and the GR-8.

Athens’ Metropolitan Area is served by the motorway network of the Attiki Odos toll-motorway (code: A6). Its main section extends from the western industrial suburb of Elefsina to Athens International Airport; while two beltways, namely the Aigaleo Beltway (A65) and the Hymettus Beltway (A64) serve parts of western and eastern Athens respectively. The span of the Attiki Odos in all its length is 65 km (40 mi),[142] making it the largest metropolitan motorway network in all of Greece.

- Motorways:

- A1/E75 N (Lamia, Larissa, Thessaloniki)

- A8 (GR-8A)/E94 W (Elefsina, Corinth, Patras)

- A6 W (Elefsina) E (Airport)

- National roads:

- GR-1 Ν (Lamia, Larissa, Thessaloniki)

- GR-8 W (Corinth, Patras)

- GR-3 N (Elefsina, Lamia, Larissa)

Education[edit]

Located on Panepistimiou Street, the old campus of the University of Athens, the National Library, and the Athens Academy form the «Athens Trilogy» built in the mid-19th century. The largest and oldest university in Athens is the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Most of the functions of NKUA have been transferred to a campus in the eastern suburb of Zografou. The National Technical University of Athens is located on Patision Street.

The University of West Attica is the second largest university in Athens. The seat of the university is located in the western area of Athens, where the philosophers of Ancient Athens delivered lectures. All the activities of UNIWA are carried out in the modern infrastructure of the three University Campuses within the metropolitan region of Athens (Egaleo Park, Ancient Olive Groove and Athens), which offer modern teaching and research spaces, entertainment and support facilities for all students.

Other universities that lie within Athens are the Athens University of Economics and Business, the Panteion University, the Agricultural University of Athens and the University of Piraeus. There are overall ten state-supported Institutions of Higher (or Tertiary) education located in the Athens Urban Area, these are by chronological order: Athens School of Fine Arts (1837), National Technical University of Athens (1837), National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (1837), Agricultural University of Athens (1920), Athens University of Economics and Business (1920), Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences (1927), University of Piraeus (1938), Harokopio University of Athens (1990), School of Pedagogical and Technological Education (2002), University of West Attica (2018). There are also several other private colleges, as they called formally in Greece, as the establishment of private universities is prohibited by the constitution. Many of them are accredited by a foreign state or university such as the American College of Greece and the Athens Campus of the University of Indianapolis.[143]

Culture[edit]

Archaeological hub[edit]

The city is a world centre of archaeological research. Alongside national academic institutions, such as the Athens University and the Archaeological Society, it is home to multiple archaeological museums, taking in the National Archaeological Museum, the Cycladic Museum, the Epigraphic Museum, the Byzantine & Christian Museum, as well as museums at the ancient Agora, Acropolis, Kerameikos, and the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum. The city is also the setting for the Demokritos laboratory for Archaeometry, alongside regional and national archaeological authorities forming part of the Greek Department of Culture.

Athens hosts 17 Foreign Archaeological Institutes which promote and facilitate research by scholars from their home countries. As a result, Athens has more than a dozen archaeological libraries and three specialized archaeological laboratories, and is the venue of several hundred specialized lectures, conferences and seminars, as well as dozens of archaeological exhibitions each year. At any given time, hundreds of international scholars and researchers in all disciplines of archaeology are to be found in the city.

Architecture[edit]

Two apartment buildings in central Athens. The left one is a modernist building of the 1930s, while the right one was built in the 1950s.

Athens incorporates architectural styles ranging from Greco-Roman and Neoclassical to Modern. They are often to be found in the same areas, as Athens is not marked by a uniformity of architectural style. A visitor will quickly notice the absence of tall buildings: Athens has very strict height restriction laws in order to ensure the Acropolis hill is visible throughout the city. Despite the variety in styles, there is evidence of continuity in elements of the architectural environment through the city’s history.[144]

For the greatest part of the 19th century Neoclassicism dominated Athens, as well as some deviations from it such as Eclecticism, especially in the early 20th century. Thus, the Old Royal Palace was the first important public building to be built, between 1836 and 1843. Later in the mid and late 19th century, Theophil Freiherr von Hansen and Ernst Ziller took part in the construction of many neoclassical buildings such as the Athens Academy and the Zappeion Hall. Ziller also designed many private mansions in the centre of Athens which gradually became public, usually through donations, such as Schliemann’s Iliou Melathron.

Beginning in the 1920s, modern architecture including Bauhaus and Art Deco began to exert an influence on almost all Greek architects, and buildings both public and private were constructed in accordance with these styles. Localities with a great number of such buildings include Kolonaki, and some areas of the centre of the city; neighbourhoods developed in this period include Kypseli.[145]

In the 1950s and 1960s during the extension and development of Athens, other modern movements such as the International style played an important role. The centre of Athens was largely rebuilt, leading to the demolition of a number of neoclassical buildings. The architects of this era employed materials such as glass, marble and aluminium, and many blended modern and classical elements.[146] After World War II, internationally known architects to have designed and built in the city included Walter Gropius, with his design for the US Embassy, and, among others, Eero Saarinen, in his postwar design for the east terminal of the Ellinikon Airport.

Urban sculpture[edit]

Across the city numerous statues or busts are to be found. Apart from the neoclassicals by Leonidas Drosis at the Academy of Athens (Plato, Socrates, Apollo and Athena), others in notable categories include the statue of Theseus by Georgios Fytalis at Thiseion; depictions of philhellenes such as Lord Byron, George Canning, and William Gladstone; the equestrian statue of Theodoros Kolokotronis by Lazaros Sochos in front of the Old Parliament; statues of Ioannis Kapodistrias, Rigas Feraios and Adamantios Korais at the University; of Evangelos Zappas and Konstantinos Zappas at the Zappeion; Ioannis Varvakis at the National Garden; the» Woodbreaker» by Dimitrios Filippotis; the equestrian statue of Alexandros Papagos in the Papagou district; and various busts of fighters of Greek independence at the Pedion tou Areos. A significant landmark is also the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Syntagma.

Museums[edit]

Athens’ most important museums include:

- the National Archaeological Museum, the largest archaeological museum in the country, and one of the most important internationally, as it contains a vast collection of antiquities. Its artefacts cover a period of more than 5,000 years, from late Neolithic Age to Roman Greece;

- the Benaki Museum with its several branches for each of its collections including ancient, Byzantine, Ottoman-era, Chinese art and beyond;

- the Byzantine and Christian Museum, one of the most important museums of Byzantine art;

- the National Art Gallery, the nation’s eponymous leading gallery, which reopened in 2021 after renovation;

- the National Museum of Contemporary Art, which opened in 2000 in a former brewery building;

- the Numismatic Museum, housing a major collection of ancient and modern coins;

- the Museum of Cycladic Art, home to an extensive collection of Cycladic art, including its famous figurines of white marble;

- the New Acropolis Museum, opened in 2009, and replacing the old museum on the Acropolis. The new museum has proved considerably popular; almost one million people visited during the summer period June–October 2009 alone. A number of smaller and privately owned museums focused on Greek culture and arts are also to be found.

- the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum, a museum which displays artifacts from the burial site of Kerameikos. Much of the pottery and other artifacts relate to Athenian attitudes towards death and the afterlife, throughout many ages.

- the Jewish Museum of Greece, a museum which describes the history and culture of the Greek Jewish community.

Tourism[edit]

Athens has been a destination for travellers since antiquity. Over the past decade, the city’s infrastructure and social amenities have improved, in part because of its successful bid to stage the 2004 Olympic Games. The Greek Government, aided by the EU, has funded major infrastructure projects such as the state-of-the-art Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport,[147] the expansion of the Athens Metro system,[87] and the new Attiki Odos Motorway.[87]

Entertainment and performing arts[edit]