Мифология Древней Греции позволяет нам погрузиться в уникальный, необыкновенный мир, где над событиями, людьми и даже чувствами властвовали всесильные боги Олимпа. Среди всех богинь особенно ярко выделяется Афродита, которой воспевали хвалу влюблённые.

Покровительница самого прекрасного и мучительного чувства, любви, она воплощала романтический образ в совершенном его воплощении. Древние греки слагали легенды о её рождении, помощи или гневе на людей. Сегодня этими преданиями мы зачитываемся не меньше, чем прошлые поколения. Какой же эллины видели свою прекрасную повелительницу – Афродиту?

Рождение Афродиты

Одно только имя Афродиты указывает на самую распространённую версию о её происхождении. В переводе с греческого “афрос” значит “пена”. Однако о рождении богини любви известно целых два варианта мифа.

В «Теогонии» говорится, что во время противостояния богов и титанов детородный орган оскоплённого Урана упал в море у острова Кифера. Взбив воду и превратив её в пену, он дал жизнь прекрасной Афродите.

Впрочем, более популярным стал миф о появлении Афродиты у берегов Кипра, из-за чего богиню называли Кипридой. Согласно ему, у берегов острова появилось скопление пены, из которой на поверхность всплыла прекрасная раковина. Раскрывшись, она подарила миру покровительницу любви.

Внешность и деятельность богини

Среди красавиц Олимпа Афродита выделялась особенным очарованием. Греки описывали её как прекрасную юную девушку с золотыми локонами, уложенными в подобие венка. Черты лица богини были нежными и мягкими.

Рядом с нею всегда были верные Оры и Хариты, что прислуживали богине, помогали ей облачаться в свои наряды. Когда она спускалась на землю, её встречали птицы и звери, собираясь у ног богини. Каждый шаг Афродиты дарил земле весну и радость, а вокруг неё распускались цветы.

© – G I I H – / giih.artstation.com

Греки считали Афродиту одной из самых могущественных обитательниц Олимпа. Не только люди, но и боги подчинялись её воле, ведь над силой любви никто не властен. Пожалуй, единственными богинями, кто мог противостоять власти Афины, были три покровительницы, отрицавшие всякие любовные отношения – Артемида, Афина и Гестия.

А вот боги-олимпийцы, напротив, мечтали о благосклонности прекрасной властительницы чувств. Несмотря на это, брак Афродиты был спланирован совсем не ею. По решению царицы богов, Геры, супругом красавицы стал хромой бог-кузнец Гефест.

Любовные похождения

Несмотря на многочисленные таланты, стать примерной женой Афродита не смогла. Любвеобильная богиня не пыталась противостоять соблазнам, тем более, на Олимпе у неё было множество поклонников. Поразительным и страстным стал союз Афродиты и Ареса, бога войны.

Такое противоречивое сочетание дало жизнь пяти юным богам. Среди детей Ареса и богини любви называют Фобоса и Деймоса (Страх и Ужас), а также ловкого Эроса. Последний стал постоянным помощником матери, умело пуская стрелы любви или ненависти в сердца людей.

Почитателем красоты Афродиты стал и хитрый Гермес, покровитель торговцев и ораторов. От него богиня родила сына Гермафродита, что имел как мужские, так и женские черты. Кроме олимпийцев, возлюбленными Афродиты становились и смертные мужчины, но сама богиня никогда не позволяла им распоряжаться своей судьбой.

В любви она не проявляла постоянства, была открыта новым отношениям и сама выбирала возлюбленного. На мой взгляд, именно такие качества с приходом христианства “превратили” некогда почитаемую покровительницу чувств в блудницу, поклонение которой осуждалось. Если в Древней Греции поведение Афродиты, описанное в мифах, было вполне обычным для богини, то в христианском мире противоречило многим принципам и моральным аспектам.

Гнев Афродиты

Афродита легко управляла судьбами и жизнями людей, нимф и богов. Одна из самых известных историй с её участием рассказывает нам о прекрасном юноше Нарциссе. Он был настолько красив, что считал, будто ни одна девушка не может быть достойной его.

Нарцисс отверг нимфу Эхо и прочих красавиц, без памяти влюбившихся в него. Это разгневало Афродиту, ведь его красота была даром богини. Кара её была поистине ужасной. Во время очередной прогулки по лесу Нарцисс решил попить воды из реки.

Склонившись, он увидел собственное отражение и потерял голову от любви к себе. Он не мог сделать и шагу прочь, чтобы не оставлять объект своей любви, что видел в отражении воды. Даже осознавая, что гибнет от голода и жажды, Нарцисс не мог отвести взгляда от своего облика на глади реки. Он умер, а вскоре на этом месте появился нежный и прекрасный цветок с тонким ароматом. Его люди назвали нарциссом.

Местонахождение: Галерея Уокера, Ливерпуль, Великобритания

Любовь богини

Однако Афродите пришлось и самой познать страдания любви. Однажды богиня влюбилась в красавца Адониса, что был прославленным охотником Греции. Нередко Адонис вместе со своей божественной возлюбленной выходил на охоту, но в один и дней решил не тревожить Афродиту.

В одиночку вступив в противостояние с диким вепрем, Адонис получил смертельную рану. Напрасно рвалась к любимому мужчине Афродита, раня свои руки зарослями кустарника – спасти Адониса она не могла.

В тех местах, где на белые цветы падала её кровь, начинали розоветь лепестки. Именно поэтому цветущий шиповник отличается такой нежной окраской. Воскресить возлюбленного Афродита не смогла, но, видя её страдания, Зевс вернул Адониса на землю – в облике весеннего цветка, символа влюблённых.

Местонахождение: Музей искусств, Иерусалим, Израиль

Афродита в Древней Греции была не просто одной из богинь Олимпа. Она воплощала силу и красоту любви, молодости, нежности. Неспроста люди считали её своей доброй покровительницей. Несмотря на суровый нрав Афродиты, она очень часто помогала влюблённым обрести счастье.

| Aphrodite | |

|---|---|

|

Goddess of love, beauty, and sexuality |

|

| Member of the Twelve Olympians | |

Aphrodite Pudica (Roman copy of 2nd century AD), National Archaeological Museum, Athens |

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Planet | Venus |

| Animals | dolphin, sparrow, dove, swan, hare, goose, bee, fish, butterfly |

| Symbol | rose, seashell, pearl, mirror, girdle, anemone, lettuce, narcissus |

| Tree | myrrh, myrtle, apple, pomegranate |

| Day | Friday (hēméra Aphrodítēs) |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Zeus and Dione (according to Homer)[1] Uranus (according to Hesiod)[2] |

| Siblings | The Titans, the Hecatoncheires, the Cyclopes, The Meliae, the Erinyes, the Giants (as daughter of Uranus) or Aeacus, Angelos, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai (as daughter of Zeus) |

| Consort | Hephaestus (divorced) Ares (unmarried consort) |

| Children | Eros, Phobos, Deimos, Harmonia, Pothos, Anteros, Himeros, Hermaphroditus, Rhodos, Eryx, Peitho, The Graces, Priapus, Aeneas |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Venus |

| Norse equivalent | Freyja |

| Etruscan equivalent | Turan |

| Hinduism equivalent | Rati |

| Canaanite equivalent | Astarte |

| Babylonian equivalent | Ishtar |

| Sumerian equivalent | Inanna |

| Zoroastrian equivalent | Anahita |

| Egyptian equivalent | Hathor |

Aphrodite ( AF-rə-DY-tee; Greek: Ἀφροδίτη, translit. Aphrodítē; Attic Greek pronunciation: [a.pʰro.dǐː.tɛː], Koine Greek: [a.ɸroˈdi.te̝], Modern Greek: [a.froˈði.ti]) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess Venus. Aphrodite’s major symbols include myrtles, roses, doves, sparrows, and swans. The cult of Aphrodite was largely derived from that of the Phoenician goddess Astarte, a cognate of the East Semitic goddess Ishtar, whose cult was based on the Sumerian cult of Inanna. Aphrodite’s main cult centers were Cythera, Cyprus, Corinth, and Athens. Her main festival was the Aphrodisia, which was celebrated annually in midsummer. In Laconia, Aphrodite was worshipped as a warrior goddess. She was also the patron goddess of prostitutes, an association which led early scholars to propose the concept of «sacred prostitution» in Greco-Roman culture, an idea which is now generally seen as erroneous.

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Aphrodite is born off the coast of Cythera from the foam (ἀφρός, aphrós) produced by Uranus’s genitals, which his son Cronus had severed and thrown into the sea. In Homer’s Iliad, however, she is the daughter of Zeus and Dione. Plato, in his Symposium, asserts that these two origins actually belong to separate entities: Aphrodite Ourania (a transcendent, «Heavenly» Aphrodite) and Aphrodite Pandemos (Aphrodite common to «all the people»).[3] Aphrodite had many other epithets, each emphasizing a different aspect of the same goddess, or used by a different local cult. Thus she was also known as Cytherea (Lady of Cythera) and Cypris (Lady of Cyprus), because both locations claimed to be the place of her birth.

In Greek mythology, Aphrodite was married to Hephaestus, the god of fire, blacksmiths and metalworking. Aphrodite was frequently unfaithful to him and had many lovers; in the Odyssey, she is caught in the act of adultery with Ares, the god of war. In the First Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, she seduces the mortal shepherd Anchises. Aphrodite was also the surrogate mother and lover of the mortal shepherd Adonis, who was killed by a wild boar. Along with Athena and Hera, Aphrodite was one of the three goddesses whose feud resulted in the beginning of the Trojan War and she plays a major role throughout the Iliad. Aphrodite has been featured in Western art as a symbol of female beauty and has appeared in numerous works of Western literature. She is a major deity in modern Neopagan religions, including the Church of Aphrodite, Wicca, and Hellenismos.

Etymology

Hesiod derives Aphrodite from aphrós (ἀφρός) «sea-foam»,[4] interpreting the name as «risen from the foam»,[5][4] but most modern scholars regard this as a spurious folk etymology.[4][6] Early modern scholars of classical mythology attempted to argue that Aphrodite’s name was of Greek or Indo-European origin, but these efforts have now been mostly abandoned.[6] Aphrodite’s name is generally accepted to be of non-Greek, probably Semitic, origin, but its exact derivation cannot be determined.[6][7]

Scholars in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, accepting Hesiod’s «foam» etymology as genuine, analyzed the second part of Aphrodite’s name as *-odítē «wanderer»[8] or *-dítē «bright».[9][10] More recently, Michael Janda, also accepting Hesiod’s etymology, has argued in favor of the latter of these interpretations and claims the story of a birth from the foam as an Indo-European mytheme.[11][12] Similarly, Krzysztof Tomasz Witczak proposes an Indo-European compound *abʰor- «very» and *dʰei- «to shine», also referring to Eos,[13] and Daniel Kölligan has interpreted her name as «shining up from the mist/foam».[14] Other scholars have argued that these hypotheses are unlikely since Aphrodite’s attributes are entirely different from those of both Eos and the Vedic deity Ushas.[15][16]

A number of improbable non-Greek etymologies have also been suggested. One Semitic etymology compares Aphrodite to the Assyrian barīrītu, the name of a female demon that appears in Middle Babylonian and Late Babylonian texts.[17] Hammarström[18] looks to Etruscan, comparing (e)prθni «lord», an Etruscan honorific loaned into Greek as πρύτανις.[19][7][20] This would make the theonym in origin an honorific, «the lady».[19][7] Most scholars reject this etymology as implausible,[19][7][20] especially since Aphrodite actually appears in Etruscan in the borrowed form Apru (from Greek Aphrō, clipped form of Aphrodite).[7] The medieval Etymologicum Magnum (c. 1150) offers a highly contrived etymology, deriving Aphrodite from the compound habrodíaitos (ἁβροδίαιτος), «she who lives delicately», from habrós and díaita. The alteration from b to ph is explained as a «familiar» characteristic of Greek «obvious from the Macedonians».[21]

Origins

Near Eastern love goddess

Late second-millennium BC nude figurine of Ishtar from Susa, showing her wearing a crown and clutching her breasts

Early fifth-century BC statue of Aphrodite from Cyprus, showing her wearing a cylinder crown and holding a dove

The cult of Aphrodite in Greece was imported from, or at least influenced by, the cult of Astarte in Phoenicia,[22][23][24][25] which, in turn, was influenced by the cult of the Mesopotamian goddess known as «Ishtar» to the East Semitic peoples and as «Inanna» to the Sumerians.[26][24][25] Pausanias states that the first to establish a cult of Aphrodite were the Assyrians, followed by the Paphians of Cyprus and then the Phoenicians at Ascalon. The Phoenicians, in turn, taught her worship to the people of Cythera.[27]

Aphrodite took on Inanna-Ishtar’s associations with sexuality and procreation.[28] Furthermore, she was known as Ourania (Οὐρανία), which means «heavenly»,[29] a title corresponding to Inanna’s role as the Queen of Heaven.[29][30] Early artistic and literary portrayals of Aphrodite are extremely similar on Inanna-Ishtar.[28] Like Inanna-Ishtar, Aphrodite was also a warrior goddess;[28][23][31] the second-century AD Greek geographer Pausanias records that, in Sparta, Aphrodite was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia, which means «warlike».[32][33] He also mentions that Aphrodite’s most ancient cult statues in Sparta and on Cythera showed her bearing arms.[32][33][34][28] Modern scholars note that Aphrodite’s warrior-goddess aspects appear in the oldest strata of her worship[35] and see it as an indication of her Near Eastern origins.[35][36]

Nineteenth century classical scholars had a general aversion to the idea that ancient Greek religion was at all influenced by the cultures of the Near East,[37] but, even Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker, who argued that Near Eastern influence on Greek culture was largely confined to material culture,[37] admitted that Aphrodite was clearly of Phoenician origin.[37] The significant influence of Near Eastern culture on early Greek religion in general, and on the cult of Aphrodite in particular,[38] is now widely recognized as dating to a period of orientalization during the eighth century BC,[38] when archaic Greece was on the fringes of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[39]

Indo-European dawn goddess

Some early comparative mythologists opposed to the idea of a Near Eastern origin argued that Aphrodite originated as an aspect of the Greek dawn goddess Eos[40][41] and that she was therefore ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European dawn goddess *Haéusōs (properly Greek Eos, Latin Aurora, Sanskrit Ushas).[40][41] Most modern scholars have now rejected the notion of a purely Indo-European Aphrodite,[6][42][16][43] but it is possible that Aphrodite, originally a Semitic deity, may have been influenced by the Indo-European dawn goddess.[43] Both Aphrodite and Eos were known for their erotic beauty and aggressive sexuality[41] and both had relationships with mortal lovers.[41] Both goddesses were associated with the colors red, white, and gold.[41] Michael Janda etymologizes Aphrodite’s name as an epithet of Eos meaning «she who rises from the foam [of the ocean]»[12] and points to Hesiod’s Theogony account of Aphrodite’s birth as an archaic reflex of Indo-European myth.[12] Aphrodite rising out of the waters after Cronus defeats Uranus as a mytheme would then be directly cognate to the Rigvedic myth of Indra defeating Vrtra, liberating Ushas.[11][12] Another key similarity between Aphrodite and the Indo-European dawn goddess is her close kinship to the Greek sky deity,[43] since both of the main claimants to her paternity (Zeus and Uranus) are sky deities.[44]

Forms and epithets

Aphrodite’s most common cultic epithet was Ourania, meaning «heavenly»,[48][49] but this epithet almost never occurs in literary texts, indicating a purely cultic significance.[50] Another common name for Aphrodite was Pandemos («For All the Folk»).[51] In her role as Aphrodite Pandemos, Aphrodite was associated with Peithō (Πείθω), meaning «persuasion»,[52] and could be prayed to for aid in seduction.[52] The character of Pausanias in Plato’s Symposium, takes differing cult-practices associated with different epithets of the goddess to claim that Ourania and Pandemos are, in fact, separate goddesses. He asserts that Aphrodite Ourania is the celestial Aphrodite, born from the sea foam after Cronus castrated Uranus, and the older of the two goddesses. According to the Symposium, Aphrodite Ourania is the inspiration of male homosexual desire, specifically the ephebic eros, and pederasty. Aphrodite Pandemos, by contrast, is the younger of the two goddesses: the common Aphrodite, born from the union of Zeus and Dione, and the inspiration of heterosexual desire and sexual promiscuity, the «lesser» of the two loves.[53][54] Paphian (Παφία), was one of her epithets, after the Paphos in Cyprus where she had emerged from the sea at her birth.[55]

Among the Neoplatonists and, later, their Christian interpreters, Ourania is associated with spiritual love, and Pandemos with physical love (desire). A representation of Ourania with her foot resting on a tortoise came to be seen as emblematic of discretion in conjugal love; it was the subject of a chryselephantine sculpture by Phidias for Elis, known only from a parenthetical comment by the geographer Pausanias.[56]

One of Aphrodite’s most common literary epithets is Philommeidḗs (φιλομμειδής),[57] which means «smile-loving»,[57] but is sometimes mistranslated as «laughter-loving».[57] This epithet occurs throughout both of the Homeric epics and the First Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite.[57] Hesiod references it once in his Theogony in the context of Aphrodite’s birth,[58] but interprets it as «genital-loving» rather than «smile-loving».[58] Monica Cyrino notes that the epithet may relate to the fact that, in many artistic depictions of Aphrodite, she is shown smiling.[58] Other common literary epithets are Cypris and Cythereia,[59] which derive from her associations with the islands of Cyprus and Cythera respectively.[59]

On Cyprus, Aphrodite was sometimes called Eleemon («the merciful»).[49] In Athens, she was known as Aphrodite en kopois («Aphrodite of the Gardens»).[49] At Cape Colias, a town along the Attic coast, she was venerated as Genetyllis «Mother».[49] The Spartans worshipped her as Potnia «Mistress», Enoplios «Armed», Morpho «Shapely», Ambologera «She who Postpones Old Age».[49] Across the Greek world, she was known under epithets such as Melainis «Black One», Skotia «Dark One», Androphonos «Killer of Men», Anosia «Unholy», and Tymborychos «Gravedigger»,[47] all of which indicate her darker, more violent nature.[47]

She had the epithet Automata because, according to Servius, she was the source of spontaneous love.[60]

A male version of Aphrodite known as Aphroditus was worshipped in the city of Amathus on Cyprus.[45][46][47] Aphroditus was depicted with the figure and dress of a woman,[45][46] but had a beard,[45][46] and was shown lifting his dress to reveal an erect phallus.[45][46] This gesture was believed to be an apotropaic symbol,[61] and was thought to convey good fortune upon the viewer.[61] Eventually, the popularity of Aphroditus waned as the mainstream, fully feminine version of Aphrodite became more popular,[46] but traces of his cult are preserved in the later legends of Hermaphroditus.[46]

Worship

Classical period

Aphrodite’s main festival, the Aphrodisia, was celebrated across Greece, but particularly in Athens and Corinth. In Athens, the Aphrodisia was celebrated on the fourth day of the month of Hekatombaion in honor of Aphrodite’s role in the unification of Attica.[62][63] During this festival, the priests of Aphrodite would purify the temple of Aphrodite Pandemos on the southwestern slope of the Acropolis with the blood of a sacrificed dove.[64] Next, the altars would be anointed[64] and the cult statues of Aphrodite Pandemos and Peitho would be escorted in a majestic procession to a place where they would be ritually bathed.[65] Aphrodite was also honored in Athens as part of the Arrhephoria festival.[66] The fourth day of every month was sacred to Aphrodite.[67]

Pausanias records that, in Sparta, Aphrodite was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia, which means «warlike».[32][33] This epithet stresses Aphrodite’s connections to Ares, with whom she had extramarital relations.[32][33] Pausanias also records that, in Sparta[32][33] and on Cythera, a number of extremely ancient cult statues of Aphrodite portrayed her bearing arms.[34][49] Other cult statues showed her bound in chains.[49]

Aphrodite was the patron goddess of prostitutes of all varieties,[68][49] ranging from pornai (cheap street prostitutes typically owned as slaves by wealthy pimps) to hetairai (expensive, well-educated hired companions, who were usually self-employed and sometimes provided sex to their customers).[69] The city of Corinth was renowned throughout the ancient world for its many hetairai,[70] who had a widespread reputation for being among the most skilled, but also the most expensive, prostitutes in the Greek world.[70] Corinth also had a major temple to Aphrodite located on the Acrocorinth[70] and was one of the main centers of her cult.[70] Records of numerous dedications to Aphrodite made by successful courtesans have survived in poems and in pottery inscriptions.[69] References to Aphrodite in association with prostitution are found in Corinth as well as on the islands of Cyprus, Cythera, and Sicily.[71] Aphrodite’s Mesopotamian precursor Inanna-Ishtar was also closely associated with prostitution.[72][73][71]

Scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries believed that the cult of Aphrodite may have involved ritual prostitution,[73][71] an assumption based on ambiguous passages in certain ancient texts, particularly a fragment of a skolion by the Boeotian poet Pindar,[74] which mentions prostitutes in Corinth in association with Aphrodite.[74] Modern scholars now dismiss the notion of ritual prostitution in Greece as a «historiographic myth» with no factual basis.[75]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

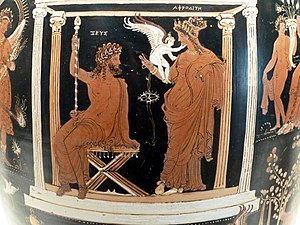

Greek relief from Aphrodisias, depicting a Roman-influenced Aphrodite sitting on a throne holding an infant while the shepherd Anchises stands beside her.

During the Hellenistic period, the Greeks identified Aphrodite with the ancient Egyptian goddesses Hathor and Isis.[76][77][78] Aphrodite was the patron goddess of the Lagid queens[79] and Queen Arsinoe II was identified as her mortal incarnation.[79] Aphrodite was worshipped in Alexandria[79] and had numerous temples in and around the city.[79] Arsinoe II introduced the cult of Adonis to Alexandria and many of the women there partook in it.[79] The Tessarakonteres, a gigantic catamaran galley designed by Archimedes for Ptolemy IV Philopator, had a circular temple to Aphrodite on it with a marble statue of the goddess herself.[79] In the second century BC, Ptolemy VIII Physcon and his wives Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III dedicated a temple to Aphrodite Hathor at Philae.[79] Statuettes of Aphrodite for personal devotion became common in Egypt starting in the early Ptolemaic times and extending until long after Egypt became a Roman province.[79]

The ancient Romans identified Aphrodite with their goddess Venus,[80] who was originally a goddess of agricultural fertility, vegetation, and springtime.[80] According to the Roman historian Livy, Aphrodite and Venus were officially identified in the third century BC[81] when the cult of Venus Erycina was introduced to Rome from the Greek sanctuary of Aphrodite on Mount Eryx in Sicily.[81] After this point, Romans adopted Aphrodite’s iconography and myths and applied them to Venus.[81] Because Aphrodite was the mother of the Trojan hero Aeneas in Greek mythology[81] and Roman tradition claimed Aeneas as the founder of Rome,[81] Venus became venerated as Venus Genetrix, the mother of the entire Roman nation.[81] Julius Caesar claimed to be directly descended from Aeneas’s son Iulus[82] and became a strong proponent of the cult of Venus.[82] This precedent was later followed by his nephew Augustus and the later emperors claiming succession from him.[82]

This syncretism greatly impacted Greek worship of Aphrodite.[83] During the Roman era, the cults of Aphrodite in many Greek cities began to emphasize her relationship with Troy and Aeneas.[83] They also began to adopt distinctively Roman elements,[83] portraying Aphrodite as more maternal, more militaristic, and more concerned with administrative bureaucracy.[83] She was claimed as a divine guardian by many political magistrates.[83] Appearances of Aphrodite in Greek literature also vastly proliferated, usually showing Aphrodite in a characteristically Roman manner.[84]

Mythology

Birth

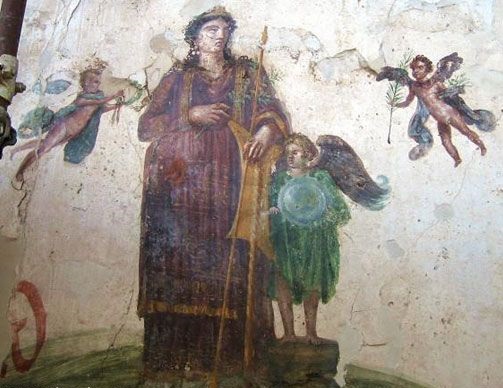

Birth of Venus from a shell, c. 50–79 AD, fresco from Pompeii

Aphrodite is usually said to have been born near her chief center of worship, Paphos, on the island of Cyprus, which is why she is sometimes called «Cyprian», especially in the poetic works of Sappho. The Sanctuary of Aphrodite Paphia, marking her birthplace, was a place of pilgrimage in the ancient world for centuries.[85] Other versions of her myth have her born near the island of Cythera, hence another of her names, «Cytherea».[86] Cythera was a stopping place for trade and culture between Crete and the Peloponesus,[87] so these stories may preserve traces of the migration of Aphrodite’s cult from the Middle East to mainland Greece.[88]

According to the version of her birth recounted by Hesiod in his Theogony,[89][90] Cronus severed Uranus’ genitals and threw them behind him into the sea.[90][91][92] The foam from his genitals gave rise to Aphrodite[4] (hence her name, which Hesiod interprets as «foam-arisen»),[4] while the Giants, the Erinyes (furies), and the Meliae emerged from the drops of his blood.[90][91] Hesiod states that the genitals «were carried over the sea a long time, and white foam arose from the immortal flesh; with it a girl grew.» Hesiod’s account of Aphrodite’s birth following Uranus’s castration is probably derived from The Song of Kumarbi,[93][94] an ancient Hittite epic poem in which the god Kumarbi overthrows his father Anu, the god of the sky, and bites off his genitals, causing him to become pregnant and give birth to Anu’s children, which include Ishtar and her brother Teshub, the Hittite storm god.[93][94]

In the Iliad,[95] Aphrodite is described as the daughter of Zeus and Dione.[4] Dione’s name appears to be a feminine cognate to Dios and Dion,[4] which are oblique forms of the name Zeus.[4] Zeus and Dione shared a cult at Dodona in northwestern Greece.[4] In Theogony, Hesiod describes Dione as an Oceanid,[96] but Apollodorus makes her the thirteenth Titan, child of Gaia and Uranus.[97]

Marriage

First-century AD Roman fresco of Mars and Venus from Pompeii

Aphrodite is consistently portrayed as a nubile, infinitely desirable adult, having had no childhood.[98] She is often depicted nude.[99] In the Iliad, Aphrodite is the apparently unmarried consort of Ares, the god of war,[100] and the wife of Hephaestus is a different goddess named Charis.[101] Likewise, in Hesiod’s Theogony, Aphrodite is unmarried and the wife of Hephaestus is Aglaea, the youngest of the three Charites.[101]

In Book Eight of the Odyssey,[102] however, the blind singer Demodocus describes Aphrodite as the wife of Hephaestus and tells how she committed adultery with Ares during the Trojan War.[101][103] The sun-god Helios saw Aphrodite and Ares having sex in Hephaestus’s bed and warned Hephaestus, who fashioned a net of gold.[103] The next time Ares and Aphrodite had sex together, the net trapped them both.[103] Hephaestus brought all the gods into the bedchamber to laugh at the captured adulterers,[104] but Apollo, Hermes, and Poseidon had sympathy for Ares[105] and Poseidon agreed to pay Hephaestus for Ares’s release.[106] Humiliated, Aphrodite returned to Cyprus, where she was attended by the Charites.[106] This narrative probably originated as a Greek folk tale, originally independent of the Odyssey.[107] In a much later interpolated detail, Ares put the young soldier Alectryon, by their door to warn them of Helios’s arrival as Helios would tell Hephaestus of Aphrodite’s infidelity if the two were discovered, but Alectryon fell asleep on guard duty.[108] Helios discovered the two and alerted Hephaestus, as Ares in rage turned Alectryon into a rooster, which always crows at dawn when the sun is about to rise announcing its arrival.[109]

After exposing them, Hephaestus asks Zeus for his wedding gifts and dowry to be returned to him;[110] by the time of the Trojan War, he is married to Charis/Aglaea, one of the Graces, apparently divorced from Aphrodite.[101][111] Afterwards, it was generally Ares who was regarded as the husband or official consort of the goddess; on the François Vase, the two arrive at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis on the same chariot, as do Zeus with Hera and Poseidon with Amphitrite; moreover poets such as Pindar and Aeschylus explicitly refer to Ares as Aphrodite’s husband.[112]

Later stories were invented to explain Aphrodite’s marriage to Hephaestus. In the most famous story, Zeus hastily married Aphrodite to Hephaestus in order to prevent the other gods from fighting over her.[113] In another version of the myth, Hephaestus gave his mother Hera a golden throne, but when she sat on it, she became trapped and he refused to let her go until she agreed to give him Aphrodite’s hand in marriage.[114] Hephaestus was overjoyed to be married to the goddess of beauty, and forged her beautiful jewelry, including a strophion (στρόφιον) known as the kestos himas (κεστὸς ἱμάς),[115] a saltire-shaped undergarment (usually translated as «girdle»),[116] which accentuated her breasts[117] and made her even more irresistible to men.[116] Such strophia were commonly used in depictions of the Near Eastern goddesses Ishtar and Atargatis.[116]

Attendants

Aphrodite is almost always accompanied by Eros, the god of lust and sexual desire.[120] In his Theogony, Hesiod describes Eros as one of the four original primeval forces born at the beginning of time,[120] but, after the birth of Aphrodite from the sea foam, he is joined by Himeros and, together, they become Aphrodite’s constant companions.[121] In early Greek art, Eros and Himeros are both shown as idealized handsome youths with wings.[122] The Greek lyric poets regarded the power of Eros and Himeros as dangerous, compulsive, and impossible for anyone to resist.[123] In modern times, Eros is often seen as Aphrodite’s son,[124] but this is actually a comparatively late innovation.[125] A scholion on Theocritus’s Idylls remarks that the sixth-century BC poet Sappho had described Eros as the son of Aphrodite and Uranus,[126] but the first surviving reference to Eros as Aphrodite’s son comes from Apollonius of Rhodes’s Argonautica, written in the third century BC, which makes him the son of Aphrodite and Ares.[127] Later, the Romans, who saw Venus as a mother goddess, seized on this idea of Eros as Aphrodite’s son and popularized it,[127] making it the predominant portrayal in works on mythology until the present day.[127]

Aphrodite’s main attendants were the three Charites, whom Hesiod identifies as the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome and names as Aglaea («Splendor»), Euphrosyne («Good Cheer»), and Thalia («Abundance»).[128] The Charites had been worshipped as goddesses in Greece since the beginning of Greek history, long before Aphrodite was introduced to the pantheon.[101] Aphrodite’s other set of attendants was the three Horae (the «Hours»),[101] whom Hesiod identifies as the daughters of Zeus and Themis and names as Eunomia («Good Order»), Dike («Justice»), and Eirene («Peace»).[129] Aphrodite was also sometimes accompanied by Harmonia, her daughter by Ares, and Hebe, the daughter of Zeus and Hera.[130]

The fertility god Priapus was usually considered to be Aphrodite’s son by Dionysus,[131][132] but he was sometimes also described as her son by Hermes, Adonis, or even Zeus.[131] A scholion on Apollonius of Rhodes’s Argonautica[133] states that, while Aphrodite was pregnant with Priapus, Hera envied her and applied an evil potion to her belly while she was sleeping to ensure that the child would be hideous.[131] In another version, Hera cursed Aphrodite’s unborn son because he had been fathered by Zeus.[134] When Aphrodite gave birth, she was horrified to see that the child had a massive, permanently erect penis, a potbelly, and a huge tongue.[131] Aphrodite abandoned the infant to die in the wilderness, but a herdsman found him and raised him, later discovering that Priapus could use his massive penis to aid in the growth of plants.[131]

Anchises

The First Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (Hymn 5), which was probably composed sometime in the mid-seventh century BC,[135] describes how Zeus once became annoyed with Aphrodite for causing deities to fall in love with mortals,[135] so he caused her to fall in love with Anchises, a handsome mortal shepherd who lived in the foothills beneath Mount Ida near the city of Troy.[135] Aphrodite appears to Anchises in the form of a tall, beautiful, mortal virgin while he is alone in his home.[136] Anchises sees her dressed in bright clothing and gleaming jewelry, with her breasts shining with divine radiance.[137] He asks her if she is Aphrodite and promises to build her an altar on top of the mountain if she will bless him and his family.[138]

Aphrodite lies and tells him that she is not a goddess, but the daughter of one of the noble families of Phrygia.[138] She claims to be able to understand the Trojan language because she had a Trojan nurse as a child and says that she found herself on the mountainside after she was snatched up by Hermes while dancing in a celebration in honor of Artemis, the goddess of virginity.[138] Aphrodite tells Anchises that she is still a virgin[138] and begs him to take her to his parents.[138] Anchises immediately becomes overcome with mad lust for Aphrodite and swears that he will have sex with her.[138] Anchises takes Aphrodite, with her eyes cast downwards, to his bed, which is covered in the furs of lions and bears.[139] He then strips her naked and makes love to her.[139]

After the lovemaking is complete, Aphrodite reveals her true divine form.[140] Anchises is terrified, but Aphrodite consoles him and promises that she will bear him a son.[140] She prophesies that their son will be the demigod Aeneas, who will be raised by the nymphs of the wilderness for five years before going to Troy to become a nobleman like his father.[141] The story of Aeneas’s conception is also mentioned in Hesiod’s Theogony and in Book II of Homer’s Iliad.[141][142]

Adonis

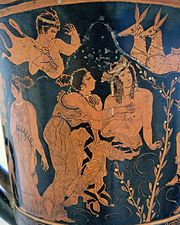

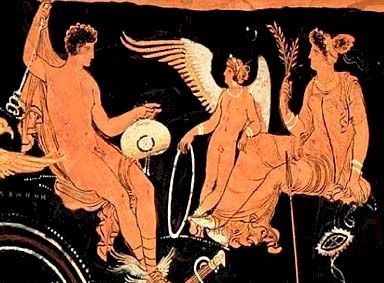

Attic red-figure aryballos by Aison (c. 410 BC) showing Aphrodite consorting with Adonis, who is seated and playing the lyre, while Eros stands behind him

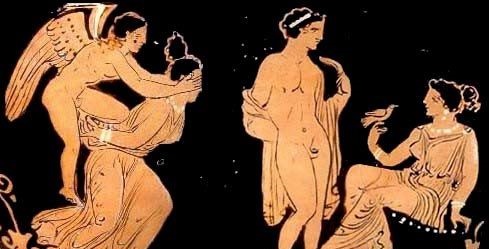

Fragment of an Attic red-figure wedding vase (c. 430–420 BC), showing women climbing ladders up to the roofs of their houses carrying «gardens of Adonis»

The myth of Aphrodite and Adonis is probably derived from the ancient Sumerian legend of Inanna and Dumuzid.[143][144][145] The Greek name Ἄδωνις (Adōnis, Greek pronunciation: [ádɔːnis]) is derived from the Canaanite word ʼadōn, meaning «lord».[146][145] The earliest known Greek reference to Adonis comes from a fragment of a poem by the Lesbian poet Sappho (c. 630 – c. 570 BC), in which a chorus of young girls asks Aphrodite what they can do to mourn Adonis’s death.[147] Aphrodite replies that they must beat their breasts and tear their tunics.[147] Later references flesh out the story with more details.[148] According to the retelling of the story found in the poem Metamorphoses by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BC – 17/18 AD), Adonis was the son of Myrrha, who was cursed by Aphrodite with insatiable lust for her own father, King Cinyras of Cyprus, after Myrrha’s mother bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the goddess.[149] Driven out after becoming pregnant, Myrrha was changed into a myrrh tree, but still gave birth to Adonis.[150]

Aphrodite found the baby and took him to the underworld to be fostered by Persephone.[151] She returned for him once he was grown and discovered him to be strikingly handsome.[151] Persephone wanted to keep Adonis, resulting in a custody battle between the two goddesses over whom should rightly possess Adonis.[151] Zeus settled the dispute by decreeing that Adonis would spend one third of the year with Aphrodite, one third with Persephone, and one third with whomever he chose.[151] Adonis chose to spend that time with Aphrodite.[151] Then, one day, while Adonis was hunting, he was wounded by a wild boar and bled to death in Aphrodite’s arms.[151] In a semi-mocking work, the Dialogues of the Gods, the satirical author Lucian comedically relates how a frustrated Aphrodite complains to the moon goddess Selene about her son Eros making Persephone fall in love with Adonis and now she has to share him with her.[152]

In different versions of the story, the boar was either sent by Ares, who was jealous that Aphrodite was spending so much time with Adonis, or by Artemis, who wanted revenge against Aphrodite for having killed her devoted follower Hippolytus.[153] In another version, Apollo in fury changed himself into a boar and killed Adonis because Aphrodite had blinded his son Erymanthus when he stumbled upon Aphrodite naked as she was bathing after intercourse with Adonis.[154] The story also provides an etiology for Aphrodite’s associations with certain flowers.[153] Reportedly, as she mourned Adonis’s death, she caused anemones to grow wherever his blood fell and declared a festival on the anniversary of his death.[151] In one version of the story, Aphrodite injured herself on a thorn from a rose bush and the rose, which had previously been white, was stained red by her blood.[153] According to Lucian’s On the Syrian Goddess,[102] each year during the festival of Adonis, the Adonis River in Lebanon (now known as the Abraham River) ran red with blood.[151]

The myth of Adonis is associated with the festival of the Adonia, which was celebrated by Greek women every year in midsummer.[145] The festival, which was evidently already celebrated in Lesbos by Sappho’s time, seems to have first become popular in Athens in the mid-fifth century BC.[145] At the start of the festival, the women would plant a «garden of Adonis», a small garden planted inside a small basket or a shallow piece of broken pottery containing a variety of quick-growing plants, such as lettuce and fennel, or even quick-sprouting grains such as wheat and barley.[145] The women would then climb ladders to the roofs of their houses, where they would place the gardens out under the heat of the summer sun.[145] The plants would sprout in the sunlight but wither quickly in the heat.[155] Then the women would mourn and lament loudly over the death of Adonis,[156] tearing their clothes and beating their breasts in a public display of grief.[156]

Divine favoritism

Pygmalion and Galatea (1717) by Jean Raoux, showing Aphrodite bringing the statue to life

In Hesiod’s Works and Days, Zeus orders Aphrodite to make Pandora, the first woman, physically beautiful and sexually attractive,[157] so that she may become «an evil men will love to embrace».[158] Aphrodite «spills grace» over Pandora’s head[157] and equips her with «painful desire and knee-weakening anguish», thus making her the perfect vessel for evil to enter the world.[159] Aphrodite’s attendants, Peitho, the Charites, and the Horae, adorn Pandora with gold and jewelry.[160]

According to one myth, Aphrodite aided Hippomenes, a noble youth who wished to marry Atalanta, a maiden who was renowned throughout the land for her beauty, but who refused to marry any man unless he could outrun her in a footrace.[161][162] Atalanta was an exceedingly swift runner and she beheaded all of the men who lost to her.[161][162] Aphrodite gave Hippomenes three golden apples from the Garden of the Hesperides and instructed him to toss them in front of Atalanta as he raced her.[161][163] Hippomenes obeyed Aphrodite’s order[161] and Atalanta, seeing the beautiful, golden fruits, bent down to pick up each one, allowing Hippomenes to outrun her.[161][163] In the version of the story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Hippomenes forgets to repay Aphrodite for her aid,[164][161] so she causes the couple to become inflamed with lust while they are staying at the temple of Cybele.[161] The couple desecrate the temple by having sex in it, leading Cybele to turn them into lions as punishment.[164][161]

The myth of Pygmalion is first mentioned by the third-century BC Greek writer Philostephanus of Cyrene,[165][166] but is first recounted in detail in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.[165] According to Ovid, Pygmalion was an exceedingly handsome sculptor from the island of Cyprus, who was so sickened by the immorality of women that he refused to marry.[167][168] He fell madly and passionately in love with the ivory cult statue he was carving of Aphrodite and longed to marry it.[167][169] Because Pygmalion was extremely pious and devoted to Aphrodite,[167][170] the goddess brought the statue to life.[167][170] Pygmalion married the girl the statue became and they had a son named Paphos, after whom the capital of Cyprus received its name.[167][170] Pseudo-Apollodorus later mentions «Metharme, daughter of Pygmalion, king of Cyprus».[171]

Anger myths

First-century AD Roman fresco from Pompeii showing the virgin Hippolytus spurning the advances of his stepmother Phaedra, whom Aphrodite caused to fall in love with him in order to bring about his tragic death.[172]

Aphrodite generously rewarded those who honored her, but also punished those who disrespected her, often quite brutally.[173] A myth described in Apollonius of Rhodes’s Argonautica and later summarized in the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus tells how, when the women of the island of Lemnos refused to sacrifice to Aphrodite, the goddess cursed them to stink horribly so that their husbands would never have sex with them.[174] Instead, their husbands started having sex with their Thracian slave-girls.[174] In anger, the women of Lemnos murdered the entire male population of the island, as well as all the Thracian slaves.[174] When Jason and his crew of Argonauts arrived on Lemnos, they mated with the sex-starved women under Aphrodite’s approval and repopulated the island.[174] From then on, the women of Lemnos never disrespected Aphrodite again.[174]

In Euripides’s tragedy Hippolytus, which was first performed at the City Dionysia in 428 BC, Theseus’s son Hippolytus worships only Artemis, the goddess of virginity, and refuses to engage in any form of sexual contact.[174] Aphrodite is infuriated by his prideful behavior[175] and, in the prologue to the play, she declares that, by honoring only Artemis and refusing to venerate her, Hippolytus has directly challenged her authority.[176] Aphrodite therefore causes Hippolytus’s stepmother, Phaedra, to fall in love with him, knowing Hippolytus will reject her.[177] After being rejected, Phaedra commits suicide and leaves a suicide note to Theseus telling him that she killed herself because Hippolytus attempted to rape her.[177] Theseus prays to Poseidon to kill Hippolytus for his transgression.[178] Poseidon sends a wild bull to scare Hippolytus’s horses as he is riding by the sea in his chariot, causing the horses to bolt and smash the chariot against the cliffs, dragging Hippolytus to a bloody death across the rocky shoreline.[178] The play concludes with Artemis vowing to kill Aphrodite’s own mortal beloved (presumably Adonis) in revenge.[179]

Glaucus of Corinth angered Aphrodite by refusing to let his horses for chariot racing mate, since doing so would hinder their speed.[180] During the chariot race at the funeral games of King Pelias, Aphrodite drove his horses mad and they tore him apart.[181] Polyphonte was a young woman who chose a virginal life with Artemis instead of marriage and children, as favoured by Aphrodite. Aphrodite cursed her, causing her to have children by a bear. The resulting offspring, Agrius and Oreius, were wild cannibals who incurred the hatred of Zeus. Ultimately, he transformed all the members of the family into birds of ill omen.[182]

According to Apollodorus, a jealous Aphrodite cursed Eos, the goddess of dawn, to be perpetually in love and have insatiable sexual desire because Eos once had lain with Aphrodite’s sweetheart Ares, the god of war.[183]

According to Ovid in his Metamorphoses (book 10.238 ff.), Propoetides who are the daughters of Propoetus from the city of Amathus on the island of Cyprus denied Aphrodite’s divinity and failed to worship her properly. Therefore, Aphrodite turned them into the world’s first prostitutes.[184] According to Diodorus Siculus, when the Rhodian sea nymphe Halia’s six sons by Poseidon arrogantly refused to let Aphrodite land upon their shore, the goddess cursed them with insanity. In their madness, they raped Halia. As punishment, Poseidon buried them in the island’s sea-caverns.[185]

Xanthius, a descendent of Bellerophon, had two children: Leucippus and an unnamed daughter. Through the wrath of Aphrodite (reasons unknown), Leucippus fell in love with his own sister. They started a secret relationship but the girl was already betrothed to another man and he went on to inform her father Xanthius, without telling him the name of the seducer. Xanthius went straight to his daughter’s chamber, where she was together with Leucippus right at the moment. On hearing him enter, she tried to escape, but Xanthius hit her with a dagger, thinking that he was slaying the seducer, and killed her. Leucippus, failing to recognize his father at first, slew him. When the truth was revealed, he had to leave the country and took part in colonization of Crete and the lands in Asia Minor.[186]

Queen Cenchreis of Cyprus, wife of King Cinyras, bragged that her daughter Myrrha was more beautiful than Aphrodite. Therefore, Myrrha was cursed by Aphrodite with insatiable lust for her own father, King Cinyras of Cyprus and he slept with her unknowingly in the dark. she eventually transformed into the myrrh tree and gave birth to Adonis in this form.[187][149][150][188] Cinyras also had three other daughters: Braesia, Laogora, and Orsedice. These girls by the wrath of Aphrodite (reasons unknown) cohabited with foreigners and ended their life in Egypt.[189]

The Muse Clio derided the goddess’ own love for Adonis. Therefore, Clio fell in love with Pierus, son of Magnes and bore Hyacinth.[190]

Aegiale was a daughter of Adrastus and Amphithea and was married to Diomedes. Because of anger of Aphrodite, whom Diomedes had wounded in the war against Troy, she had multiple lovers, including a certain Hippolytus.[191][192] when Aegiale went so far as to threaten his life, he fled to Italy.[192][193] According to Stesichorus and Hesiod while Tyndareus sacrificing to the gods he forgot Aphrodite, therefore goddess made his daughters twice and thrice wed and deserters of their husbands. Timandra deserted Echemus and went and came to Phyleus and Clytaemnestra deserted Agamemnon and lay with Aegisthus who was a worse mate for her and eventually killed her husband with her lover and finally, Helen of Troy deserted Menelaus under the influence of Aphrodite for Paris and her unfaitfulness eventually causes the War of Troy.[194]

In one of the versions of the legend, Pasiphae did not make offerings to the goddess Venus [Aphrodite]. Because of this Venus [Aphrodite] inspired in her an unnatural love for a bull[195] or she cursed her because she was Helios’s daughter who revealed her adultery to Hephaestus.[196][197] For Helios’ own tale-telling, she cursed him with uncontrollable lust over the mortal princess Leucothoe, which led to him abandoning his then-lover Clytie, leaving her heartbroken.[198]

Lysippe was the mother of Tanais by Berossos. Her son only venerated Ares and was fully devoted to war, neglecting love and marriage. Aphrodite cursed him with falling in love with his own mother. Preferring to die rather than give up his chastity, he threw himself into the river Amazonius, which was subsequently renamed Tanais.[199]

According to Hyginus, At the behest of Zeus, Orpheus’s mother, the Muse Calliope, judged the dispute between the goddesses Aphrodite and Persephone over Adonis and decided that both shall possess him half of the year. This enraged Venus [Aphrodite], because she had not been granted what she thought was her right. Therefore, Venus [Aphrodite] inspired love for Orpheus in the women of Thrace, causing them to tear him apart as each of them sought Orpheus for herself.[200]

Judgment of Paris and Trojan War

The myth of the Judgement of Paris is mentioned briefly in the Iliad,[201] but is described in depth in an epitome of the Cypria, a lost poem of the Epic Cycle,[202] which records that all the gods and goddesses as well as various mortals were invited to the marriage of Peleus and Thetis (the eventual parents of Achilles).[201] Only Eris, goddess of discord, was not invited.[202] She was annoyed at this, so she arrived with a golden apple inscribed with the word καλλίστῃ (kallistēi, «for the fairest»), which she threw among the goddesses.[203] Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena all claimed to be the fairest, and thus the rightful owner of the apple.[203]

The goddesses chose to place the matter before Zeus, who, not wanting to favor one of the goddesses, put the choice into the hands of Paris, a Trojan prince.[203] After bathing in the spring of Mount Ida where Troy was situated, the goddesses appeared before Paris for his decision.[203] In the extant ancient depictions of the Judgement of Paris, Aphrodite is only occasionally represented nude, and Athena and Hera are always fully clothed.[204] Since the Renaissance, however, Western paintings have typically portrayed all three goddesses as completely naked.[204]

All three goddesses were ideally beautiful and Paris could not decide between them, so they resorted to bribes.[203] Hera tried to bribe Paris with power over all Asia and Europe,[203] and Athena offered wisdom, fame and glory in battle,[203] but Aphrodite promised Paris that, if he were to choose her as the fairest, she would let him marry the most beautiful woman on earth.[205] This woman was Helen, who was already married to King Menelaus of Sparta.[205] Paris selected Aphrodite and awarded her the apple.[205] The other two goddesses were enraged and, as a direct result, sided with the Greeks in the Trojan War.[205]

Aphrodite plays an important and active role throughout the entirety of Homer’s Iliad.[206] In Book III, she rescues Paris from Menelaus after he foolishly challenges him to a one-on-one duel.[207] She then appears to Helen in the form of an old woman and attempts to persuade her to have sex with Paris,[208] reminding her of his physical beauty and athletic prowess.[209] Helen immediately recognizes Aphrodite by her beautiful neck, perfect breasts, and flashing eyes[210] and chides the goddess, addressing her as her equal.[211] Aphrodite sharply rebukes Helen, reminding her that, if she vexes her, she will punish her just as much as she has favored her already.[212] Helen demurely obeys Aphrodite’s command.[212]

In Book V, Aphrodite charges into battle to rescue her son Aeneas from the Greek hero Diomedes.[213] Diomedes recognizes Aphrodite as a «weakling» goddess[213] and, thrusting his spear, nicks her wrist through her «ambrosial robe».[214] Aphrodite borrows Ares’s chariot to ride back to Mount Olympus.[215] Zeus chides her for putting herself in danger,[215][216] reminding her that «her specialty is love, not war.»[215] According to Walter Burkert, this scene directly parallels a scene from Tablet VI of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which Ishtar, Aphrodite’s Akkadian precursor, cries to her mother Antu after the hero Gilgamesh rejects her sexual advances, but is mildly rebuked by her father Anu.[217] In Book XIV of the Iliad, during the Dios Apate episode, Aphrodite lends her kestos himas to Hera for the purpose of seducing Zeus and distracting him from the combat while Poseidon aids the Greek forces on the beach.[218] In the Theomachia in Book XXI, Aphrodite again enters the battlefield to carry Ares away after he is wounded.[215][219]

Offspring

Sometimes poets and dramatists recounted ancient traditions, which varied, and sometimes they invented new details; later scholiasts might draw on either or simply guess.[220][221] Thus while Aeneas and Phobos were regularly described as offspring of Aphrodite, others listed here such as Priapus and Eros were sometimes said to be children of Aphrodite but with varying fathers and sometimes given other mothers or none at all.

| Offspring | Father |

|---|---|

| Aeneas, Lyrus/Lyrnus[222] | Anchises |

| Phobos,[223] Deimos,[223] Harmonia,[130][223] the Erotes (Eros,[224][121] Anteros,[b] Himeros,[121] Pothos)[223] | Ares[101][223] |

| Hymenaios, Iacchus, Priapus,[131] the Charites (Graces: Aglaea, Euphrosyne, Thalia) | Dionysus |

| Hermaphroditos,[225] Priapus[131] | Hermes |

| Rhodos[226] | Poseidon |

| Beroe, Golgos,[227] Priapus (rarely)[131] | Adonis[151][153] |

| Eryx,[228] Meligounis and several more unnamed daughters[229] | Butes[230][231] |

| Astynous[232] | Phaethon[233] |

| Priapus[134] | Zeus |

| Peitho[234] | unknown |

Iconography

Symbols

Rich-throned immortal Aphrodite,

scheming daughter of Zeus, I pray you,

with pain and sickness, Queen, crush not my heart,

but come, if ever in the past you heard my voice from afar and hearkened,

and left your father’s halls and came, with gold

chariot yoked; and pretty sparrows

brought you swiftly across the dark earth

fluttering wings from heaven through the air.

Aphrodite’s most prominent avian symbol was the dove,[236] which was originally an important symbol of her Near Eastern precursor Inanna-Ishtar.[237][238] (In fact, the ancient Greek word for «dove», peristerá, may be derived from a Semitic phrase peraḥ Ištar, meaning «bird of Ishtar».[237][238]) Aphrodite frequently appears with doves in ancient Greek pottery[236] and the temple of Aphrodite Pandemos on the southwest slope of the Athenian Acropolis was decorated with relief sculptures of doves with knotted fillets in their beaks.[239] Votive offerings of small, white, marble doves were also discovered in the temple of Aphrodite at Daphni.[239] In addition to her associations with doves, Aphrodite was also closely linked with sparrows[236] and she is described riding in a chariot pulled by sparrows in Sappho’s «Ode to Aphrodite».[239] According to myth, the dove was originally a nymph named Peristera who helped Aphrodite win in a flower-picking contest over her son Eros; for this Eros turned her into a dove, but Aphrodite took the dove under her wing and made it her sacred bird.[240][241]

Because of her connections to the sea, Aphrodite was associated with a number of different types of water fowl,[242] including swans, geese, and ducks.[242] Aphrodite’s other symbols included the sea, conch shells, and roses.[243] The rose and myrtle flowers were both sacred to Aphrodite.[244] A myth explaining the origin of Aphrodite’s connection to myrtle goes that originally the myrtle was a maiden, Myrina, a dedicated priestess of Aphrodite. When her previous betrothed carried her away from the temple to marry her, Myrina killed him, and Aphrodite turned her into a myrtle, forever under her protection.[245] Her most important fruit emblem was the apple,[246] and in myth, she turned Melus, childhood friend and kin-in-law to Adonis, into an apple after he took his own life, mourning over Adonis’ death. Likewise, Melus’s wife Pelia was turned into a dove.[247] She was also associated with pomegranates,[248] possibly because the red seeds suggested sexuality[249] or because Greek women sometimes used pomegranates as a method of birth control.[249] In Greek art, Aphrodite is often also accompanied by dolphins and Nereids.[250]

In classical art

A scene of Aphrodite rising from the sea appears on the back of the Ludovisi Throne (c. 460 BC),[253] which was probably originally part of a massive altar that was constructed as part of the Ionic temple to Aphrodite in the Greek polis of Locri Epizephyrii in Magna Graecia in southern Italy.[253] The throne shows Aphrodite rising from the sea, clad in a diaphanous garment, which is drenched with seawater and clinging to her body, revealing her upturned breasts and the outline of her navel.[254] Her hair hangs dripping as she reaches to two attendants standing barefoot on the rocky shore on either side of her, lifting her out of the water.[254] Scenes with Aphrodite appear in works of classical Greek pottery,[255] including a famous white-ground kylix by the Pistoxenos Painter dating the between c. 470 and 460 BC, showing her riding on a swan or goose.[255]

In c. 364/361 BC, the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles carved the marble statue Aphrodite of Knidos,[256][252] which Pliny the Elder later praised as the greatest sculpture ever made.[256] The statue showed a nude Aphrodite modestly covering her pubic region while resting against a water pot with her robe draped over it for support.[257][258] The Aphrodite of Knidos was the first full-sized statue to depict Aphrodite completely naked[259] and one of the first sculptures that was intended to be viewed from all sides.[260][259] The statue was purchased by the people of Knidos in around 350 BC[259] and proved to be tremendously influential on later depictions of Aphrodite.[260] The original sculpture has been lost,[256][258] but written descriptions of it as well several depictions of it on coins are still extant[261][256][258] and over sixty copies, small-scale models, and fragments of it have been identified.[261]

The Greek painter Apelles of Kos, a contemporary of Praxiteles, produced the panel painting Aphrodite Anadyomene (Aphrodite Rising from the Sea).[251] According to Athenaeus, Apelles was inspired to paint the painting after watching the courtesan Phryne take off her clothes, untie her hair, and bathe naked in the sea at Eleusis.[251] The painting was displayed in the Asclepeion on the island of Kos.[251] The Aphrodite Anadyomene went unnoticed for centuries,[251] but Pliny the Elder records that, in his own time, it was regarded as Apelles’s most famous work.[251]

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, statues depicting Aphrodite proliferated;[262] many of these statues were modeled at least to some extent on Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos.[262] Some statues show Aphrodite crouching naked;[263] others show her wringing water out of her hair as she rises from the sea.[263] Another common type of statue is known as Aphrodite Kallipygos, the name of which is Greek for «Aphrodite of the Beautiful Buttocks»;[263] this type of sculpture shows Aphrodite lifting her peplos to display her buttocks to the viewer while looking back at them from over her shoulder.[263] The ancient Romans produced massive numbers of copies of Greek sculptures of Aphrodite[262] and more sculptures of Aphrodite have survived from antiquity than of any other deity.[263]

-

The Ludovisi Throne (possibly c. 460 BC) is believed to be a classical Greek bas-relief, although it has also been alleged to be a 19th-century forgery.

-

Attic white-ground red-figured kylix of Aphrodite riding a swan (c. 46-470) found at Kameiros (Rhodes)

-

Red-figure vase painting of Aphrodite and Phaon (c. 420-400 BC)

-

Apuleian vase painting of Zeus plotting with Aphrodite to seduce Leda while Eros sits on her arm (c. 330 BC)

-

Aphrodite Leaning Against a Pillar (third century BC)

-

Aphrodite Binding Her Hair (second century BC)

-

Greek sculpture group of Aphrodite, Eros, and Pan (c. 100 BC)

-

-

-

Post-classical culture

Fifteenth century manuscript illumination of Venus, sitting on a rainbow, with her devotees offering her their hearts

Middle Ages

Early Christians frequently adapted pagan iconography to suit Christian purposes.[264][265][266] In the Early Middle Ages, Christians adapted elements of Aphrodite/Venus’s iconography and applied them to Eve and prostitutes,[265] but also female saints and even the Virgin Mary.[265] Christians in the east reinterpreted the story of Aphrodite’s birth as a metaphor for baptism;[267] in a Coptic stele from the sixth century AD, a female orant is shown wearing Aphrodite’s conch shell as a sign that she is newly baptized.[267] Throughout the Middle Ages, villages and communities across Europe still maintained folk tales and traditions about Aphrodite/Venus[268] and travelers reported a wide variety of stories.[268] Numerous Roman mosaics of Venus survived in Britain, preserving memory of the pagan past.[243] In North Africa in the late fifth century AD, Fulgentius of Ruspe encountered mosaics of Aphrodite[243] and reinterpreted her as a symbol of the sin of Lust,[243] arguing that she was shown naked because «the sin of lust is never cloaked»[243] and that she was often shown «swimming» because «all lust suffers shipwreck of its affairs.»[243] He also argued that she was associated with doves and conchs because these are symbols of copulation,[243] and that she was associated with roses because «as the rose gives pleasure, but is swept away by the swift movement of the seasons, so lust is pleasant for a moment, but is swept away forever.»[243]

While Fulgentius had appropriated Aphrodite as a symbol of Lust,[269] Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) interpreted her as a symbol of marital procreative sex[269] and declared that the moral of the story of Aphrodite’s birth is that sex can only be holy in the presence of semen, blood, and heat, which he regarded as all being necessary for procreation.[269] Meanwhile, Isidore denigrated Aphrodite/Venus’s son Eros/Cupid as a «demon of fornication» (daemon fornicationis).[269] Aphrodite/Venus was best known to Western European scholars through her appearances in Virgil’s Aeneid and Ovid’s Metamorphoses.[270] Venus is mentioned in the Latin poem Pervigilium Veneris («The Eve of Saint Venus»), written in the third or fourth century AD,[271] and in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Genealogia Deorum Gentilium.[272]

Since the Late Middle Ages. the myth of the Venusberg (German; French Mont de Vénus, «Mountain of Venus») – a subterranean realm ruled by Venus, hidden underneath Christian Europe – became a motif of European folklore rendered in various legends and epics. In German folklore of the 16th century, the narrative becomes associated with the minnesinger Tannhäuser, and in that form the myth was taken up in later literature and opera.

Art

Aphrodite is the central figure in Sandro Botticelli’s painting Primavera, which has been described as «one of the most written about, and most controversial paintings in the world»,[273] and «one of the most popular paintings in Western art».[274] The story of Aphrodite’s birth from the foam was a popular subject matter for painters during the Italian Renaissance,[275] who were attempting to consciously reconstruct Apelles of Kos’s lost masterpiece Aphrodite Anadyomene based on the literary ekphrasis of it preserved by Cicero and Pliny the Elder.[276] Artists also drew inspiration from Ovid’s description of the birth of Venus in his Metamorphoses.[276] Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1485) was also partially inspired by a description by Poliziano of a relief on the subject.[276] Later Italian renditions of the same scene include Titian’s Venus Anadyomene (c. 1525)[276] and Raphael’s painting in the Stufetta del cardinal Bibbiena (1516).[276] Titian’s biographer Giorgio Vasari identified all of Titian’s paintings of naked women as paintings of «Venus»,[277] including an erotic painting from c. 1534, which he called the Venus of Urbino, even though the painting does not contain any of Aphrodite/Venus’s traditional iconography and the woman in it is clearly shown in a contemporary setting, not a classical one.[277]

Jacques-Louis David’s final work was his 1824 magnum opus, Mars Being Disarmed by Venus,[279] which combines elements of classical, Renaissance, traditional French art, and contemporary artistic styles.[279] While he was working on the painting, David described it, saying, «This is the last picture I want to paint, but I want to surpass myself in it. I will put the date of my seventy-five years on it and afterwards I will never again pick up my brush.»[280] The painting was exhibited first in Brussels and then in Paris, where over 10,000 people came to see it.[280] Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s painting Venus Anadyomene was one of his major works.[281] Louis Geofroy described it as a «dream of youth realized with the power of maturity, a happiness that few obtain, artists or others.»[281] Théophile Gautier declared: «Nothing remains of the marvelous painting of the Greeks, but surely if anything could give the idea of antique painting as it was conceived following the statues of Phidias and the poems of Homer, it is M. Ingres’s painting: the Venus Anadyomene of Apelles has been found.»[281] Other critics dismissed it as a piece of unimaginative, sentimental kitsch,[281] but Ingres himself considered it to be among his greatest works and used the same figure as the model for his later 1856 painting La Source.[281]

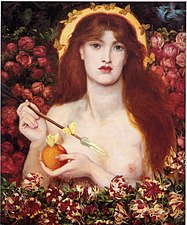

Paintings of Venus were favorites of the late nineteenth-century Academic artists in France.[282][283] In 1863, Alexandre Cabanel won widespread critical acclaim at the Paris Salon for his painting The Birth of Venus, which the French emperor Napoleon III immediately purchased for his own personal art collection.[284] Édouard Manet’s 1865 painting Olympia parodied the nude Venuses of the Academic painters, particularly Cabanel’s Birth of Venus.[285] In 1867, the English Academic painter Frederic Leighton displayed his Venus Disrobing for the Bath at the academy.[286] The art critic J. B. Atkinson praised it, declaring that «Mr Leighton, instead of adopting corrupt Roman notions regarding Venus such as Rubens embodied, has wisely reverted to the Greek idea of Aphrodite, a goddess worshipped, and by artists painted, as the perfection of female grace and beauty.»[287] A year later, the English painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, painted Venus Verticordia (Latin for «Aphrodite, the Changer of Hearts»), showing Aphrodite as a nude red-headed woman in a garden of roses.[286] Though he was reproached for his outré subject matter,[286] Rossetti refused to alter the painting and it was soon purchased by J. Mitchell of Bradford.[287] In 1879, William Adolphe Bouguereau exhibited at the Paris Salon his own Birth of Venus,[284] which imitated the classical tradition of contrapposto and was met with widespread critical acclaim, rivalling the popularity of Cabanel’s version from nearly two decades prior.[284]

-

-

Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan (1827) by Alexandre Charles Guillemot

-

-

-

Literature

William Shakespeare’s erotic narrative poem Venus and Adonis (1593), a retelling of the courtship of Aphrodite and Adonis from Ovid’s Metamorphoses,[288][289] was the most popular of all his works published within his own lifetime.[290][291] Six editions of it were published before Shakespeare’s death (more than any of his other works)[291] and it enjoyed particularly strong popularity among young adults.[290] In 1605, Richard Barnfield lauded it,[291] declaring that the poem had placed Shakespeare’s name «in fames immortall Booke».[291] Despite this, the poem has received mixed reception from modern critics;[290] Samuel Taylor Coleridge defended it,[290] but Samuel Butler complained that it bored him[290] and C. S. Lewis described an attempted reading of it as «suffocating».[290]

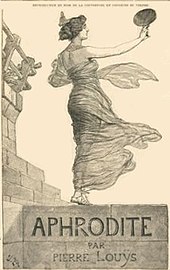

Aphrodite appears in Richard Garnett’s short story collection The Twilight of the Gods and Other Tales (1888),[292] in which the gods’ temples have been destroyed by Christians.[293] Stories revolving around sculptures of Aphrodite were common in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[294] Examples of such works of literature include the novel The Tinted Venus: A Farcical Romance (1885) by Thomas Anstey Guthrie and the short story The Venus of Ille (1887) by Prosper Mérimée,[295] both of which are about statues of Aphrodite that come to life.[295] Another noteworthy example is Aphrodite in Aulis by the Anglo-Irish writer George Moore,[296] which revolves around an ancient Greek family who moves to Aulis.[297] The French writer Pierre Louÿs titled his erotic historical novel Aphrodite: mœurs antiques (1896) after the Greek goddess.[298] The novel enjoyed widespread commercial success,[298] but scandalized French audiences due to its sensuality and its decadent portrayal of Greek society.[298]

In the early twentieth century, stories of Aphrodite were used by feminist poets,[299] such as Amy Lowell and Alicia Ostriker.[300] Many of these poems dealt with Aphrodite’s legendary birth from the foam of the sea.[299] Other feminist writers, including Claude Cahun, Thit Jensen, and Anaïs Nin also made use of the myth of Aphrodite in their writings.[301] Ever since the publication of Isabel Allende’s book Aphrodite: A Memoir of the Senses in 1998, the name «Aphrodite» has been used as a title for dozens of books dealing with all topics even superficially connected to her domain.[302] Frequently these books do not even mention Aphrodite,[302] or mention her only briefly, but make use of her name as a selling point.[303]

Modern worship

In 1938, Gleb Botkin, a Russian immigrant to the United States, founded the Church of Aphrodite, a neopagan religion centered around the worship of a mother goddess, whom its practitioners identified as Aphrodite.[304][305] The Church of Aphrodite’s theology was laid out in the book In Search of Reality, published in 1969, two years before Botkin’s death.[306] The book portrayed Aphrodite in a drastically different light than the one in which the Greeks envisioned her,[306] instead casting her as «the sole Goddess of a somewhat Neoplatonic Pagan monotheism».[306] It claimed that the worship of Aphrodite had been brought to Greece by the mystic teacher Orpheus,[306] but that the Greeks had misunderstood Orpheus’s teachings and had not realized the importance of worshipping Aphrodite alone.[306]

Aphrodite is a major deity in Wicca,[307][308] a contemporary nature-based syncretic Neopagan religion.[309] Wiccans regard Aphrodite as one aspect of the Goddess[308] and she is frequently invoked by name during enchantments dealing with love and romance.[310][311] Wiccans regard Aphrodite as the ruler of human emotions, erotic spirituality, creativity, and art.[307] As one of the twelve Olympians, Aphrodite is a major deity within Hellenismos (Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism),[312][313] a Neopagan religion which seeks to authentically revive and recreate the religion of ancient Greece in the modern world.[314][better source needed] Unlike Wiccans, Hellenists are usually strictly polytheistic or pantheistic.[315][better source needed] Hellenists venerate Aphrodite primarily as the goddess of romantic love,[313][better source needed] but also as a goddess of sexuality, the sea, and war.[313][better source needed] Her many epithets include «Sea Born», «Killer of Men», «She upon the Graves», «Fair Sailing», and «Ally in War».[313][better source needed]

Genealogy

| Aphrodite’s family tree [316] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

See also

- Anchises

- Cupid

- Girdle of Aphrodite

- History of nude art

- Lakshmi, rose from the ocean like Aphrodite and has 8-pointed star like Ishtar

Notes

- ^ Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Napoli). «so-called Venus in a bikini.» Cir.campania.beniculturali.it.

The statuette portrays Aphrodite on the point of untying the laces of the sandal on her left foot, under which a small Eros squats, touching the sole of her shoe with his right hand. The Goddess is leaning with her left arm (the hand is missing) against a figure of Priapus standing, naked and bearded, positioned on a small cylindrical altar while, next to her left thigh, there is a tree trunk over which the garment of the Goddess is folded. Aphrodite, almost completely naked, wears only a sort of costume, consisting of a corset held up by two pairs of straps and two short sleeves on the upper part of her arm, from which a long chain leads to her hips and forms a star-shaped motif at the level of her navel. The ‘bikini’, for which the statuette is famous, is obtained by the masterly use of the technique of gilding, also employed on her groin, in the pendant necklace and in the armilla on Aphrodite’s right wrist, as well as on Priapus’ phallus. Traces of the red paint are evident on the tree trunk, on the short curly hair gathered back in a bun and on the lips of the Goddess, as well as on the heads of Priapus and the Eros. Aphrodite’s eyes are made of glass paste, while the presence of holes at the level of the ear-lobes suggest the existence of precious metal ear-rings which have since been lost. An interesting insight into the female ornaments of Roman times, the statuette, probably imported from the area of Alexandria, reproduces with a few modifications the statuary type of Aphrodite untying her sandal, known from copies in bronze and terracotta.

For extensive research and a bibliography on the subject, see: de Franciscis 1963, p. 78, tav. XCI; Kraus 1973, nn. 270–71, pp. 194–95; Pompei 1973, n. 132; Pompeji 1973, n. 199, pp. 142 e 144; Pompeji 1974, n. 281, pp. 148–49; Pompeii A.D. 79 1976, p. 83 e n. 218; Pompeii A.D. 79 1978, I, n. 208, pp. 64–65, II, n. 208, p. 189; Döhl, Zanker 1979, p. 202, tav. Va; Pompeii A.D. 79 1980, p. 79 e n. 198; Pompeya 1981, n. 198, p. 107; Pompeii lives 1984, fig. 10, p. 46; Collezioni Museo 1989, I, 2, n. 254, pp. 146–47; PPM II, 1990, n. 7, p. 532; Armitt 1993, p. 240; Vésuve 1995, n. 53, pp. 162–63; Vulkan 1995, n. 53, pp. 162–63; LIMC VIII, 1, 1997, p. 210, s.v. Venus, n. 182; LIMC VIII, 2, 1997, p. 144; LIMC VIII, 1, 1997, p. 1031, s.v. Priapos, n. 15; LIMC VIII, 2, 1997, p. 680; Romana Pictura 1998, n. 153, p. 317 e tav. a p. 245; Cantarella 1999, p. 128; De Caro 1999, pp. 100–01; De Caro 2000, p. 46 e tav. a p. 62; Pompeii 2000, n. 1, p. 62.

- ^ Anteros was originally born from the sea alongside Aphrodite; only later became her son.

References

- ^ Homer, Iliad 5.370.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, 188–90.

- ^ This claim is made at Symposium 180e. It is hard to interpret the role of the various speeches in the dialogue and their relationship to what Plato actually thought; therefore, it is controversial whether Plato, in fact, believed this claim about Aphrodite. See Frisbee Sheffield, «The Role of the Earlier Speeches in the «Symposium»: Plato’s Endoxic Method?» in J. H. Lesher, Debra Nails & Frisbee C. C. Sheffield (eds.), Plato’s Symposium: Issues in Interpretation and Reception. Harvard University Press (2006).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cyrino 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, 190–97.

- ^ a b c d West 2000, pp. 134–38.

- ^ a b c d e Beekes 2009, p. 179.

- ^ Paul Kretschmer, «Zum pamphylischen Dialekt», Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiet der Indogermanischen Sprachen 33 (1895): 267.

- ^ Ernst Maaß, «Aphrodite und die hl. Pelagia», Neue Jahrbücher für das klassische Altertum 27 (1911): 457–68.

- ^ Vittore Pisani, «Akmon e Dieus», Archivio glottologico italiano 24 (1930): 65–73.

- ^ a b Janda 2005, pp. 349–60.

- ^ a b c d Janda 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Witczak 1993, pp. 115–23.