Not to be confused with Amine.

Anime (Japanese: アニメ, IPA: [aɲime] (listen)) is hand-drawn and computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside of Japan and in English, anime refers specifically to animation produced in Japan.[1] However, in Japan and in Japanese, anime (a term derived from a shortening of the English word animation) describes all animated works, regardless of style or origin. Animation produced outside of Japan with similar style to Japanese animation is commonly referred to as anime-influenced animation.

The earliest commercial Japanese animations date to 1917. A characteristic art style emerged in the 1960s with the works of cartoonist Osamu Tezuka and spread in following decades, developing a large domestic audience. Anime is distributed theatrically, through television broadcasts, directly to home media, and over the Internet. In addition to original works, anime are often adaptations of Japanese comics (manga), light novels, or video games. It is classified into numerous genres targeting various broad and niche audiences.

Anime is a diverse medium with distinctive production methods that have adapted in response to emergent technologies. It combines graphic art, characterization, cinematography, and other forms of imaginative and individualistic techniques.[2] Compared to Western animation, anime production generally focuses less on movement, and more on the detail of settings and use of «camera effects», such as panning, zooming, and angle shots.[2] Diverse art styles are used, and character proportions and features can be quite varied, with a common characteristic feature being large and emotive eyes.[3]

The anime industry consists of over 430 production companies, including major studios such as Studio Ghibli, Kyoto Animation, Sunrise, Bones, Ufotable, MAPPA, Wit Studio, CoMix Wave Films, Production I.G and Toei Animation. Since the 1980s, the medium has also seen widespread international success with the rise of foreign dubbed, subtitled programming, and since the 2010s its increasing distribution through streaming services and a widening demographic embrace of anime culture, both within Japan and worldwide.[4] As of 2016, Japanese animation accounted for 60% of the world’s animated television shows.[5]

Etymology

As a type of animation, anime is an art form that comprises many genres found in other mediums; it is sometimes mistakenly classified as a genre itself.[6] In Japanese, the term anime is used to refer to all animated works, regardless of style or origin.[7] English-language dictionaries typically define anime ()[8] as «a style of Japanese animation»[9] or as «a style of animation originating in Japan».[10] Other definitions are based on origin, making production in Japan a requisite for a work to be considered «anime».[11]

The etymology of the term anime is disputed. The English word «animation» is written in Japanese katakana as アニメーション (animēshon) and as アニメ (anime, pronounced [a.ɲi.me] (listen)) in its shortened form.[11] Some sources claim that the term is derived from the French term for animation dessin animé («cartoon», literally ‘animated drawing’),[12] but others believe this to be a myth derived from the popularity of anime in France in the late 1970s and 1980s.[11]

In English, anime—when used as a common noun—normally functions as a mass noun. (For example: «Do you watch anime?» or «How much anime have you collected?»)[13][14] As with a few other Japanese words, such as saké and Pokémon, English texts sometimes spell anime as animé (as in French), with an acute accent over the final e, to cue the reader to pronounce the letter, not to leave it silent as English orthography may suggest. Prior to the widespread use of anime, the term Japanimation was prevalent throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In the mid-1980s, the term anime began to supplant Japanimation;[15] in general, the latter term now only appears in period works where it is used to distinguish and identify Japanese animation.[16]

History

Precursors

Emakimono and kagee are considered precursors of Japanese animation.[17] Emakimono was common in the eleventh century. Traveling storytellers narrated legends and anecdotes while the emakimono was unrolled from the right to left with chronological order, as a moving panorama.[17] Kagee was popular during the Edo period and originated from the shadows play of China.[17] Magic lanterns from the Netherlands were also popular in the eighteenth century.[17] The paper play called Kamishibai surged in the twelfth century and remained popular in the street theater until the 1930s.[17] Puppets of the bunraku theater and ukiyo-e prints are considered ancestors of characters of most Japanese animations.[17] Finally, mangas were a heavy inspiration for anime. Cartoonists Kitzawa Rakuten and Okamoto Ippei used film elements in their strips.[17]

Pioneers

A frame from Namakura Gatana (1917), the oldest surviving Japanese animated short film made for cinemas

Animation in Japan began in the early 20th century, when filmmakers started to experiment with techniques pioneered in France, Germany, the United States, and Russia.[12] A claim for the earliest Japanese animation is Katsudō Shashin (c. 1907),[18] a private work by an unknown creator.[19] In 1917, the first professional and publicly displayed works began to appear; animators such as Ōten Shimokawa, Seitarō Kitayama, and Jun’ichi Kōuchi (considered the «fathers of anime») produced numerous films, the oldest surviving of which is Kōuchi’s Namakura Gatana.[20] Many early works were lost with the destruction of Shimokawa’s warehouse in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.[21]

By the mid-1930s, animation was well-established in Japan as an alternative format to the live-action industry. It suffered competition from foreign producers, such as Disney, and many animators, including Noburō Ōfuji and Yasuji Murata, continued to work with cheaper cutout animation rather than cel animation.[22] Other creators, including Kenzō Masaoka and Mitsuyo Seo, nevertheless made great strides in technique, benefiting from the patronage of the government, which employed animators to produce educational shorts and propaganda.[23] In 1940, the government dissolved several artists’ organizations to form the Shin Nippon Mangaka Kyōkai.[a][24] The first talkie anime was Chikara to Onna no Yo no Naka (1933), a short film produced by Masaoka.[25][26] The first feature-length anime film was Momotaro: Sacred Sailors (1945), produced by Seo with a sponsorship from the Imperial Japanese Navy.[27] The 1950s saw a proliferation of short, animated advertisements created for television.[28]

Modern era

Frame from the opening sequence of Tezuka’s 1963 TV series Astro Boy

In the 1960s, manga artist and animator Osamu Tezuka adapted and simplified Disney animation techniques to reduce costs and limit frame counts in his productions.[29] Originally intended as temporary measures to allow him to produce material on a tight schedule with an inexperienced staff, many of his limited animation practices came to define the medium’s style.[30] Three Tales (1960) was the first anime film broadcast on television;[31] the first anime television series was Instant History (1961–64).[32] An early and influential success was Astro Boy (1963–66), a television series directed by Tezuka based on his manga of the same name. Many animators at Tezuka’s Mushi Production later established major anime studios (including Madhouse, Sunrise, and Pierrot).

The 1970s saw growth in the popularity of manga, many of which were later animated. Tezuka’s work—and that of other pioneers in the field—inspired characteristics and genres that remain fundamental elements of anime today. The giant robot genre (also known as «mecha»), for instance, took shape under Tezuka, developed into the super robot genre under Go Nagai and others, and was revolutionized at the end of the decade by Yoshiyuki Tomino, who developed the real robot genre.[33] Robot anime series such as Gundam and Super Dimension Fortress Macross became instant classics in the 1980s, and the genre remained one of the most popular in the following decades.[34] The bubble economy of the 1980s spurred a new era of high-budget and experimental anime films, including Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (1987), and Akira (1988).[35]

Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), a television series produced by Gainax and directed by Hideaki Anno, began another era of experimental anime titles, such as Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Cowboy Bebop (1998). In the 1990s, anime also began attracting greater interest in Western countries; major international successes include Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z, both of which were dubbed into more than a dozen languages worldwide. In 2003, Spirited Away, a Studio Ghibli feature film directed by Hayao Miyazaki, won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards. It later became the highest-grossing anime film,[b] earning more than $355 million. Since the 2000s, an increased number of anime works have been adaptations of light novels and visual novels; successful examples include The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya and Fate/stay night (both 2006). Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train became the highest-grossing Japanese film and one of the world’s highest-grossing films of 2020.[36] It also became the fastest grossing film in Japanese cinema, because in 10 days it made 10 billion yen ($95.3m; £72m).[36] It beat the previous record of Spirited Away which took 25 days.[36]

Attributes

Anime differs from other forms of animation by its art styles, methods of animation, its production, and its process. Visually, anime works exhibit a wide variety of art styles, differing between creators, artists, and studios.[37] While no single art style predominates anime as a whole, they do share some similar attributes in terms of animation technique and character design.

Anime is fundamentally characterized by the use of limited animation, flat expression, the suspension of time, its thematic range, the presence of historical figures, its complex narrative line and, above all, a peculiar drawing style, with characters characterized by large and oval eyes, with very defined lines, bright colors and reduced movement of the lips.[38][39]

Technique

Modern anime follows a typical animation production process, involving storyboarding, voice acting, character design, and cel production. Since the 1990s, animators have increasingly used computer animation to improve the efficiency of the production process. Early anime works were experimental, and consisted of images drawn on blackboards, stop motion animation of paper cutouts, and silhouette animation.[40][41] Cel animation grew in popularity until it came to dominate the medium. In the 21st century, the use of other animation techniques is mostly limited to independent short films,[42] including the stop motion puppet animation work produced by Tadahito Mochinaga, Kihachirō Kawamoto and Tomoyasu Murata.[43][44] Computers were integrated into the animation process in the 1990s, with works such as Ghost in the Shell and Princess Mononoke mixing cel animation with computer-generated images.[45] Fuji Film, a major cel production company, announced it would stop cel production, producing an industry panic to procure cel imports and hastening the switch to digital processes.[45]

Prior to the digital era, anime was produced with traditional animation methods using a pose to pose approach.[40] The majority of mainstream anime uses fewer expressive key frames and more in-between animation.[46]

Japanese animation studios were pioneers of many limited animation techniques, and have given anime a distinct set of conventions. Unlike Disney animation, where the emphasis is on the movement, anime emphasizes the art quality and let limited animation techniques make up for the lack of time spent on movement. Such techniques are often used not only to meet deadlines but also as artistic devices.[47] Anime scenes place emphasis on achieving three-dimensional views, and backgrounds are instrumental in creating the atmosphere of the work.[12] The backgrounds are not always invented and are occasionally based on real locations, as exemplified in Howl’s Moving Castle and The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya.[48][49] Oppliger stated that anime is one of the rare mediums where putting together an all-star cast usually comes out looking «tremendously impressive».[50]

The cinematic effects of anime differentiates itself from the stage plays found in American animation. Anime is cinematically shot as if by camera, including panning, zooming, distance and angle shots to more complex dynamic shots that would be difficult to produce in reality.[51][52][53] In anime, the animation is produced before the voice acting, contrary to American animation which does the voice acting first.[54]

Characters

The body proportions of human anime characters tend to accurately reflect the proportions of the human body in reality. The height of the head is considered by the artist as the base unit of proportion. Head heights can vary, but most anime characters are about seven to eight heads tall.[55] Anime artists occasionally make deliberate modifications to body proportions to produce super deformed characters that feature a disproportionately small body compared to the head; many super deformed characters are two to four heads tall. Some anime works like Crayon Shin-chan completely disregard these proportions, in such a way that they resemble caricatured Western cartoons.

A common anime character design convention is exaggerated eye size. The animation of characters with large eyes in anime can be traced back to Osamu Tezuka, who was deeply influenced by such early animation characters as Betty Boop, who was drawn with disproportionately large eyes.[56] Tezuka is a central figure in anime and manga history, whose iconic art style and character designs allowed for the entire range of human emotions to be depicted solely through the eyes.[57] The artist adds variable color shading to the eyes and particularly to the cornea to give them greater depth. Generally, a mixture of a light shade, the tone color, and a dark shade is used.[58][59] Cultural anthropologist Matt Thorn argues that Japanese animators and audiences do not perceive such stylized eyes as inherently more or less foreign.[60] However, not all anime characters have large eyes. For example, the works of Hayao Miyazaki are known for having realistically proportioned eyes, as well as realistic hair colors on their characters.[61]

Hair in anime is often unnaturally lively and colorful or uniquely styled. The movement of hair in anime is exaggerated and «hair action» is used to emphasize the action and emotions of characters for added visual effect.[62] Poitras traces hairstyle color to cover illustrations on manga, where eye-catching artwork and colorful tones are attractive for children’s manga.[62] Despite being produced for a domestic market, anime features characters whose race or nationality is not always defined, and this is often a deliberate decision, such as in the Pokémon animated series.[63]

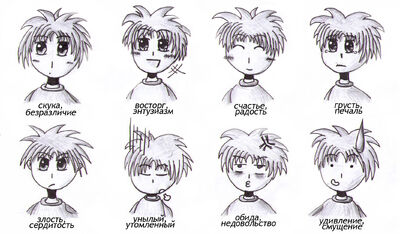

Anime and manga artists often draw from a shared iconography to represent particular emotions.

Anime and manga artists often draw from a common canon of iconic facial expression illustrations to denote particular moods and thoughts.[64] These techniques are often different in form than their counterparts in Western animation, and they include a fixed iconography that is used as shorthand for certain emotions and moods.[65] For example, a male character may develop a nosebleed when aroused.[65] A variety of visual symbols are employed, including sweat drops to depict nervousness, visible blushing for embarrassment, or glowing eyes for an intense glare.[66] Another recurring sight gag is the use of chibi (deformed, simplified character designs) figures to comedically punctuate emotions like confusion or embarrassment.[65]

Music

The opening and credits sequences of most anime television series are accompanied by J-pop or J-rock songs, often by reputed bands—as written with the series in mind—but are also aimed at the general music market, therefore they often allude only vaguely or not at all, to the thematic settings or plot of the series. Also, they are often used as incidental music («insert songs») in an episode, in order to highlight particularly important scenes.[67][better source needed]

Genres

Anime are often classified by target demographic, including children’s (子供, kodomo), girls’ (少女, shōjo), boys’ (少年, shōnen) and a diverse range of genres targeting an adult audience. Shoujo and shounen anime sometimes contain elements popular with children of both sexes in an attempt to gain crossover appeal. Adult anime may feature a slower pace or greater plot complexity that younger audiences may typically find unappealing, as well as adult themes and situations.[68] A subset of adult anime works featuring pornographic elements are labeled «R18» in Japan, and are internationally known as hentai (originating from pervert (変態, hentai)). By contrast, some anime subgenres incorporate ecchi, sexual themes or undertones without depictions of sexual intercourse, as typified in the comedic or harem genres; due to its popularity among adolescent and adult anime enthusiasts, the inclusion of such elements is considered a form of fan service.[69][70] Some genres explore homosexual romances, such as yaoi (male homosexuality) and yuri (female homosexuality). While often used in a pornographic context, the terms yaoi and yuri can also be used broadly in a wider context to describe or focus on the themes or the development of the relationships themselves.[71]

Anime’s genre classification differs from other types of animation and does not lend itself to simple classification.[72] Gilles Poitras compared the labeling Gundam 0080 and its complex depiction of war as a «giant robot» anime akin to simply labeling War and Peace a «war novel».[72] Science fiction is a major anime genre and includes important historical works like Tezuka’s Astro Boy and Yokoyama’s Tetsujin 28-go. A major subgenre of science fiction is mecha, with the Gundam metaseries being iconic.[73] The diverse fantasy genre includes works based on Asian and Western traditions and folklore; examples include the Japanese feudal fairytale InuYasha, and the depiction of Scandinavian goddesses who move to Japan to maintain a computer called Yggdrasil in Ah! My Goddess.[74] Genre crossing in anime is also prevalent, such as the blend of fantasy and comedy in Dragon Half, and the incorporation of slapstick humor in the crime anime film Castle of Cagliostro.[75] Other subgenres found in anime include magical girl, harem, sports, martial arts, literary adaptations, medievalism,[76] and war.[77]

Formats

Early anime works were made for theatrical viewing, and required played musical components before sound and vocal components were added to the production. In 1958, Nippon Television aired Mogura no Abanchūru («Mole’s Adventure»), both the first televised and first color anime to debut.[78] It was not until the 1960s when the first televised series were broadcast and it has remained a popular medium since.[79] Works released in a direct-to-video format are called «original video animation» (OVA) or «original animation video» (OAV); and are typically not released theatrically or televised prior to home media release.[80][81][better source needed] The emergence of the Internet has led some animators to distribute works online in a format called «original net animation» (ONA).[82][better source needed]

The home distribution of anime releases were popularized in the 1980s with the VHS and LaserDisc formats.[80] The VHS NTSC video format used in both Japan and the United States is credited as aiding the rising popularity of anime in the 1990s.[80] The LaserDisc and VHS formats were transcended by the DVD format which offered the unique advantages; including multiple subtitling and dubbing tracks on the same disc.[83] The DVD format also has its drawbacks in its usage of region coding; adopted by the industry to solve licensing, piracy and export problems and restricted region indicated on the DVD player.[83] The Video CD (VCD) format was popular in Hong Kong and Taiwan, but became only a minor format in the United States that was closely associated with bootleg copies.[83]

A key characteristic of many anime television shows is serialization, where a continuous story arc stretches over multiple episodes or seasons. Traditional American television had an episodic format, with each episode typically consisting of a self-contained story. In contrast, anime shows such as Dragon Ball Z had a serialization format, where continuous story arcs stretch over multiple episodes or seasons, which distinguished them from traditional American television shows; serialization has since also become a common characteristic of American streaming television shows during the «Peak TV» era.[84]

Industry

Akihabara district of Tokyo is popular with anime and manga fans as well as otaku subculture in Japan.

The animation industry consists of more than 430 production companies with some of the major studios including Toei Animation, Gainax, Madhouse, Gonzo, Sunrise, Bones, TMS Entertainment, Nippon Animation, P.A.Works, Studio Pierrot, Production I.G, Ufotable and Studio Ghibli.[85] Many of the studios are organized into a trade association, The Association of Japanese Animations. There is also a labor union for workers in the industry, the Japanese Animation Creators Association. Studios will often work together to produce more complex and costly projects, as done with Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away.[85] An anime episode can cost between US$100,000 and US$300,000 to produce.[86] In 2001, animation accounted for 7% of the Japanese film market, above the 4.6% market share for live-action works.[85] The popularity and success of anime is seen through the profitability of the DVD market, contributing nearly 70% of total sales.[85] According to a 2016 article on Nikkei Asian Review, Japanese television stations have bought over ¥60 billion worth of anime from production companies «over the past few years», compared with under ¥20 billion from overseas.[87] There has been a rise in sales of shows to television stations in Japan, caused by late night anime with adults as the target demographic.[87] This type of anime is less popular outside Japan, being considered «more of a niche product».[87] Spirited Away (2001) is the all-time highest-grossing film in Japan.[88][89] It was also the highest-grossing anime film worldwide until it was overtaken by Makoto Shinkai’s 2016 film Your Name.[90] Anime films represent a large part of the highest-grossing Japanese films yearly in Japan, with 6 out of the top 10 in 2014, in 2015 and also in 2016.

Anime has to be licensed by companies in other countries in order to be legally released. While anime has been licensed by its Japanese owners for use outside Japan since at least the 1960s, the practice became well-established in the United States in the late 1970s to early 1980s, when such TV series as Gatchaman and Captain Harlock were licensed from their Japanese parent companies for distribution in the US market. The trend towards American distribution of anime continued into the 1980s with the licensing of titles such as Voltron and the ‘creation’ of new series such as Robotech through use of source material from several original series.[91]

In the early 1990s, several companies began to experiment with the licensing of less children-oriented material. Some, such as A.D. Vision, and Central Park Media and its imprints, achieved fairly substantial commercial success and went on to become major players in the now very lucrative American anime market. Others, such as AnimEigo, achieved limited success. Many companies created directly by Japanese parent companies did not do as well, most releasing only one or two titles before completing their American operations.

Licenses are expensive, often hundreds of thousands of dollars for one series and tens of thousands for one movie.[92] The prices vary widely; for example, Jinki: Extend cost only $91,000 to license while Kurau Phantom Memory cost $960,000.[92] Simulcast Internet streaming rights can be cheaper, with prices around $1,000-$2,000 an episode,[93] but can also be more expensive, with some series costing more than US$200,000 per episode.[94]

The anime market for the United States was worth approximately $2.74 billion in 2009, today in 2022 the anime market for the United States is worth approximately $25 billion.[95] Dubbed animation began airing in the United States in 2000 on networks like The WB and Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim.[96] In 2005, this resulted in five of the top ten anime titles having previously aired on Cartoon Network.[96] As a part of localization, some editing of cultural references may occur to better follow the references of the non-Japanese culture.[97] The cost of English localization averages US$10,000 per episode.[98]

The industry has been subject to both praise and condemnation for fansubs, the addition of unlicensed and unauthorized subtitled translations of anime series or films.[99] Fansubs, which were originally distributed on VHS bootlegged cassettes in the 1980s, have been freely available and disseminated online since the 1990s.[99] Since this practice raises concerns for copyright and piracy issues, fansubbers tend to adhere to an unwritten moral code to destroy or no longer distribute an anime once an official translated or subtitled version becomes licensed. They also try to encourage viewers to buy an official copy of the release once it comes out in English, although fansubs typically continue to circulate through file-sharing networks.[100] Even so, the laid back regulations of the Japanese animation industry tend to overlook these issues, allowing it to grow underground and thus increasing the popularity until there is a demand for official high-quality releases for animation companies. This has led to an increase in global popularity with Japanese animations, reaching $40 million in sales in 2004.[101]

Since the 2010s anime has become a global multibillion industry setting a sales record in 2017 of ¥2.15 trillion ($19.8 billion), driven largely by demand from overseas audiences.[102] In 2019, Japan’s anime industry was valued at $24 billion a year with 48% of that revenue coming from overseas (which is now its largest industry sector).[103] By 2025 the anime industry is expected to reach a value of $30 billion with over 60% of that revenue to come from

overseas.[104]

Markets

Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) valued the domestic anime market in Japan at ¥2.4 trillion ($24 billion), including ¥2 trillion from licensed products, in 2005.[105] JETRO reported sales of overseas anime exports in 2004 to be ¥2 trillion ($18 billion).[106] JETRO valued the anime market in the United States at ¥520 billion ($5.2 billion),[105] including $500 million in home video sales and over $4 billion from licensed products, in 2005.[107] JETRO projected in 2005 that the worldwide anime market, including sales of licensed products, would grow to ¥10 trillion ($100 billion).[105][107] The anime market in China was valued at $21 billion in 2017,[108] and is projected to reach $31 billion by 2020.[109] By 2030 the global anime market is expected to reach a value of $48.3 Billion with the largest contributors to this growth being North America, Europe, China and The Middle East.[110]

In 2019, the annual overseas exports of Japanese animation exceeded $10 billion for the first time in history.[111]

Awards

The anime industry has several annual awards that honor the year’s best works. Major annual awards in Japan include the Ōfuji Noburō Award, the Mainichi Film Award for Best Animation Film, the Animation Kobe Awards, the Japan Media Arts Festival animation awards, the Tokyo Anime Award and the Japan Academy Prize for Animation of the Year. In the United States, anime films compete in the Crunchyroll Anime Awards. There were also the American Anime Awards, which were designed to recognize excellence in anime titles nominated by the industry, and were held only once in 2006.[112] Anime productions have also been nominated and won awards not exclusively for anime, like the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature or the Golden Bear.

Working conditions

In recent years, the anime industry has been accused by both Japanese and foreign media for underpaying and overworking its animators.[113][114][115] In response the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida promised to improve the working conditions and salary of all animators and creators working in the industry.[116] A few anime studios such as MAPPA have taken actions to improve the working conditions of their employees.[117] There has also been a slight increase in production costs and animator pays during the COVID-19 pandemic.[118]

Globalization and cultural impact

Anime has become commercially profitable in Western countries, as demonstrated by early commercially successful Western adaptations of anime, such as Astro Boy and Speed Racer. Early American adaptions in the 1960s made Japan expand into the continental European market, first with productions aimed at European and Japanese children, such as Heidi, Vicky the Viking and Barbapapa, which aired in various countries. Italy, Spain, and France grew a particular interest into Japan’s output, due to its cheap selling price and productive output. In fact, Italy imported the most anime outside of Japan.[120] These mass imports influenced anime popularity in South American, Arabic and German markets.[121]

The beginning of 1980 saw the introduction of Japanese anime series into the American culture. In the 1990s, Japanese animation slowly gained popularity in America. Media companies such as Viz and Mixx began publishing and releasing animation into the American market.[122] The 1988 film Akira is largely credited with popularizing anime in the Western world during the early 1990s, before anime was further popularized by television shows such as Pokémon and Dragon Ball Z in the late 1990s.[123][124] By 1997, Japanese anime was the fastest-growing genre in the American video industry.[125] The growth of the Internet later provided international audiences an easy way to access Japanese content.[101] Early on, online piracy played a major role in this, through over time many legal alternatives appeared. Since the 2010s various streaming services have become increasingly involved in the production and licensing of anime for the international markets.[126][127] This is especially the case with net services such as Netflix and Crunchyroll which have large catalogs in Western countries, although as of 2020 anime fans in many developing non-Western countries, such as India and Philippines, have fewer options of obtaining access to legal content, and therefore still turn to online piracy.[128][129] However beginning with the early 2020s anime has been experiencing yet another boom in global popularity and demand due to the COVID-19 pandemic and streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, HBO Max, Hulu and anime-only services like Crunchyroll, increasing the international availability of the amount of new licensed anime shows as well as the size of their catalogs.[130][131][132][133][134]

Netflix reported that, between October 2019 and September 2020, more than 100 million member households worldwide had watched at least one anime title on the platform. Anime titles appeared on the streaming platforms top 10 lists in almost 100 countries within the 1-year period.[135]

As of 2021, Japanese anime are the most demanded foreign language shows in the United States accounting for 30.5% of the market share(In comparison, Spanish and Korean shows account for 21% and 11% of the market share).[136] In 2021 more than half of Netflix’s global members watched anime.[137][138]

In 2022, the anime series Attack on Titan won the award of «Most In-Demand TV Series in the World 2021» in the Global TV Demand Awards. Attack on Titan became the first ever non-English language series to earn the title of «World’s Most In-Demand TV Show», previously held by only The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones.[139][140]

Rising interest in anime as well as Japanese video games has led to an increase of university students in the United Kingdom wanting to get a degree in the Japanese language.[141]

Various anime and manga series have influenced Hollywood in the making of numerous famous movies and characters.[142] Hollywood itself has produced live-action adaptations of various anime series such as Ghost in the Shell, Death Note, Dragon Ball Evolution and Cowboy Bebop. However most of these adaptations have been reviewed negatively by both the critics and the audience and have become box-office flops. The main reasons for the unsuccessfulness of Hollywood’s adaptions of anime being the often change of plot and characters from the original source material and the limited capabilities a live-action movie or series can do in comparison to an animated counterpart.[143][144] One particular exception however is Alita: Battle Angel, which has become a moderate commercial success, receiving generally positive reviews from both the critics and the audience for its visual effects and following the source material. The movie grossed $404 million worldwide, making it directors Robert Rodriguez’s highest-grossing film.[145][146]

Anime alongside many other parts of Japanese pop culture has helped Japan to gain a positive worldwide image and improve its relations with other countries.[147] In 2015, during remarks welcoming Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the White House, President Barack Obama thanked Japan for its cultural contributions to the United States by saying:

This visit is a celebration of the ties of friendship and family that bind our peoples. I first felt it when I was 6 years old when my mother took me to Japan. I felt it growing up in Hawaii, like communities across our country, home to so many proud Japanese Americans… Today is also a chance for Americans, especially our young people, to say thank you for all the things we love from Japan. Like karate and karaoke. Manga and anime. And, of course, emojis.[148]

In July 2020, after the approval of a Chilean government project in which citizens of Chile would be allowed to withdraw up to 10% of their privately held retirement savings, journalist Pamela Jiles celebrated by running through Congress with her arms spread out behind her, imitating the move of many characters of the anime and manga series Naruto.[149][150] In April 2021, Peruvian politicians Jorge Hugo Romero of the PPC and Milagros Juárez of the UPP cosplayed as anime characters to get the otaku vote.[151]

A 2018 survey conducted in 20 countries and territories using a sample consisting of 6,600 respondents held by Dentsu revealed that 34% of all surveyed people found excellency in anime and manga more than other Japanese cultural or technological aspects which makes this mass Japanese media the 3rd most liked «Japanese thing», below Japanese cuisine (34.6%) and Japanese robotics (35.1%). The advertisement company views anime as a profitable tool for marketing campaigns in foreign countries due its popularity and high reception.[152]

Anime plays a role in driving tourism to Japan. In surveys held by Statista between 2019 and 2020, 24.2% of tourists from the United States, 7.7% of tourists from China and 6.1% of tourists from South Korea said they were motivated to visit Japan because of Japanese popular culture.[153] In a 2021 survey held by Crunchyroll market research, 94% of Gen-Z’s and 73% of the general population said that they are familiar with anime.[154][155]

Fan response

Anime clubs gave rise to anime conventions in the 1990s with the «anime boom», a period marked by anime’s increased global popularity.[156] These conventions are dedicated to anime and manga and include elements like cosplay contests and industry talk panels.[157] Cosplay, a portmanteau of «costume play», is not unique to anime and has become popular in contests and masquerades at anime conventions.[158] Japanese culture and words have entered English usage through the popularity of the medium, including otaku, an unflattering Japanese term commonly used in English to denote an obsessive fan of anime and/or manga.[159] Another word that has arisen describing obsessive fans in the United States is wapanese meaning ‘white individuals who want to be Japanese’, or later known as weeaboo or weeb, individuals who demonstrate an obsession in Japanese anime subculture, a term that originated from abusive content posted on the website 4chan.org.[160] While originally derogatory, the terms «Otaku» and «Weeb» have been reappropriated by some in the anime fandom overtime and today are used by some fans to refer to themselves in a comedic and more positive way.[161]

Anime enthusiasts have produced fan fiction and fan art, including computer wallpapers and anime music videos (AMVs).[162]

Many fans will visit sites depicted in anime, games, manga and other forms of otaku culture, this behavior is known as Anime pilgrimage[163]

As of the 2020s, many anime fans use social media platforms like YouTube, Facebook, Reddit[164] and Twitter (which has added an entire «anime and manga» category of topics)[165][166]

with online communities and databases such as MyAnimeList to discuss anime, manga and track their progress watching respective series as well as using news outlets such as Anime News Network.[167][168]

Due to anime’s increased popularity in recent years, a large number of celebrities such as Elon Musk, BTS and Ariana Grande have come out as anime fans.[169]

Anime style

One of the key points that made anime different from a handful of Western cartoons is the potential for visceral content. Once the expectation that the aspects of visual intrigue or animation being just for children is put aside, the audience can realize that themes involving violence, suffering, sexuality, pain, and death can all be storytelling elements utilized in anime just as much as other media.[170] However, as anime itself became increasingly popular, its styling has been inevitably the subject of both satire and serious creative productions.[11] South Park‘s «Chinpokomon» and «Good Times with Weapons» episodes, Adult Swim’s Perfect Hair Forever, and Nickelodeon’s Kappa Mikey are examples of Western satirical depictions of Japanese culture and anime, but anime tropes have also been satirized by some anime such as KonoSuba.

Traditionally only Japanese works have been considered anime, but some works have sparked debate for blurring the lines between anime and cartoons, such as the American anime-style production Avatar: The Last Airbender.[171] These anime-styled works have become defined as anime-influenced animation, in an attempt to classify all anime styled works of non-Japanese origin.[172] Some creators of these works cite anime as a source of inspiration, for example the French production team for Ōban Star-Racers that moved to Tokyo to collaborate with a Japanese production team.[173][174][175] When anime is defined as a «style» rather than as a national product, it leaves open the possibility of anime being produced in other countries,[171] but this has been contentious amongst fans, with John Oppliger stating, «The insistence on referring to original American art as Japanese «anime» or «manga» robs the work of its cultural identity.»[11][176]

A U.A.E.-Filipino produced TV series called Torkaizer is dubbed as the «Middle East’s First Anime Show», and is currently in production[177] and looking for funding.[178] Netflix has produced multiple anime series in collaboration with Japanese animation studios,[179] and in doing so, has offered a more accessible channel for distribution to Western markets.[180]

The web-based series RWBY, produced by Texas-based company Rooster Teeth, is produced using an anime art style, and the series has been described as «anime» by multiple sources. For example, Adweek, in the headline to one of its articles, described the series as «American-made anime»,[181] and in another headline, The Huffington Post described it as simply «anime», without referencing its country of origin.[182] In 2013, Monty Oum, the creator of RWBY, said «Some believe just like Scotch needs to be made in Scotland, an American company can’t make anime. I think that’s a narrow way of seeing it. Anime is an art form, and to say only one country can make this art is wrong.»[183] RWBY has been released in Japan with a Japanese language dub;[184] the CEO of Rooster Teeth, Matt Hullum, commented «This is the first time any American-made anime has been marketed to Japan. It definitely usually works the other way around, and we’re really pleased about that.»[181]

Media franchises

In Japanese culture and entertainment, media mix is a strategy to disperse content across multiple representations: different broadcast media, gaming technologies, cell phones, toys, amusement parks, and other methods.[185] It is the Japanese term for a transmedia franchise.[186][187] The term gained its circulation in late 1980s, but the origins of the strategy can be traced back to the 1960s with the proliferation of anime, with its interconnection of media and commodity goods.[188]

A number of anime and manga media franchises such as Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, Dragon Ball and Gundam have gained considerable global popularity, and are among the world’s highest-grossing media franchises. Pokémon in particular is estimated to be the highest-grossing media franchise of all time.[189]

See also

- Animation director

- Chinese animation

- Aeni

- Cinema of Japan

- Cool Japan

- Culture of Japan

- History of anime

- Japanophilia

- Japanese language

- Japanese popular culture

- Lists of anime

- Manga

- Mechademia

- Otaku

- Vtuber

- Voice acting in Japan

Notes

- ^ Japanese: 新日本漫画家協会, lit. «New Japan Manga Artist Association»

- ^ Spirited Away was later surpassed as the highest-grossing anime film by Your Name (2016).

References

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (May 18, 2021). «What «Anime» Means». Kotaku. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Craig 2000, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (September 21, 2016). «A Serious Look at Big Anime Eyes». Kotaku. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ^ «Cannes: How Japanese Anime Became the World’s Most Bankable Genre». The Hollywood Reporter. May 16, 2022.

- ^ Napier, Susan J. (2016). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. St. Martin’s Press. p. 10. ISBN 9781250117724.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 7.

- ^ «Tezuka: The Marvel of Manga — Education Kit» (PDF). Art Gallery New South Wales. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- ^ «Anime — Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary». Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ «Anime». Lexico. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ «Anime». Merriam-Webster. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e «Lexicon — Anime». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Schodt 1997.

- ^ «Anime». American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.).

- ^ «Anime». Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1).

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c d e f g Novielli, Maria Roberta (2018). Floating worlds: a short history of Japanese animation. Boca Raton. ISBN 978-1-351-33482-2. OCLC 1020690005.

- ^ Litten, Frederick S. (June 29, 2014). «Japanese color animation from ca. 1907 to 1945» (PDF). p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 18, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Clements & McCarthy 2006, p. 169.

- ^ Litten, Frederick S. «Some remarks on the first Japanese animation films in 1917» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2013.

- ^ Clements & McCarthy 2006, p. 170.

- ^ Sharp, Jasper (September 23, 2004). «Pioneers of Japanese Animation (Part 1)». Midnight Eye. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Katsunori; Watanabe, Yasushi (1977). Nihon animēshon eigashi. Yūbunsha. pp. 26–37.

- ^ Kinsella 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Baricordi 2000, p. 12.

- ^ Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha. 1993. ISBN 978-4-06-206489-7.

- ^ Official booklet, The Roots of Japanese Anime (DVD). Zakka Films. 2009.

- ^ Douglass, Jason Cody (2019). Beyond Anime? Rethinking Japanese Animation Through Early Animated Television Commercials. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 213. ISBN 9783030279394.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 6.

- ^ Zagzoug, Marwa (April 2001). «The History of Anime & Manga». Northern Virginia Community College. Archived from the original on May 19, 2013. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Patten 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Patten 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Patten 2004, p. 264.

- ^ Patten 2004, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Le Blanc & Odell 2017, p. 56.

- ^ a b c «How a demon-slaying film is drawing Japan back to the cinemas». BBC. October 31, 2020. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 231.

- ^ Horno Lopez, Antonio (2012). «Controversia sobre el origen del anime. Una nueva perspectiva sobre el primer dibujo animado japonés». Con a de animación. Spain: Technical University of Valencia (2): 106–107. doi:10.4995/caa.2012.1055. ISSN 2173-3511.

- ^ Horno Lopez, Antonio (2014). Animación japonesa: análisis de series de anime actuales [Japanese Animation: Analysis of Current Anime Series»]. Doctoral Thesis (Thesis). University of Granada. p. 4. ISBN 9788490830222.

- ^ a b Jouvanceau, Pierre; Clare Kitson (translator) (2004). The Silhouette Film. Genoa: Le Mani. p. 103. ISBN 88-8012-299-1. Archived from the original on March 20, 2008. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ «Tribute to Noburō Ōfuji» (PDF). To the Source of Anime: Japanese Animation. Cinémathèque québécoise. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Sharp, Jasper (2003). «Beyond Anime: A Brief Guide to Experimental Japanese Animation». Midnight Eye. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Sharp, Jasper (2004). «Interview with Kihachirō Kawamoto». Midnight Eye. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Munroe Hotes, Catherine (2008). «Tomoyasu Murata and Company». Midnight Eye. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Poitras 2000, p. 29.

- ^ Dong, Bamboo; Brienza, Casey; Pocock, Sara (November 4, 2008). «A Look at Key Animation». Anime News Network. Chicks on Anime. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Dong, Bamboo; Brienza, Casey; Pocock, Sara; Sevakis, Robin (September 16, 2008). «Chicks on Anime — Sep 16th 2008». Anime News Network. Chicks on Anime. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Cavallaro 2006, pp. 157–171.

- ^ «Reference pictures to actual places». Archived from the original on January 26, 2007. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ Oppliger, John (October 1, 2012). «Ask John: What Determines a Show’s Animation Quality?». AnimeNation. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 58.

- ^ «Anime production process — feature film». PRODUCTION I.G. 2000. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ «Cinematography: Looping and Animetion Techniques». Understanding Anime. 1999. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 59.

- ^ «Body Proportion». Akemi’s Anime World. Archived from the original on August 5, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ Brenner 2007, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 60.

- ^ «Basic Anime Eye Tutorial». Centi, Biorust.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ Carlus (June 6, 2007). «How to color anime eye». YouTube. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «Do Manga Characters Look «White»?». Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2005.

- ^ Poitras 1998.

- ^ a b Poitras 2000, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Tobin 2004, p. 88.

- ^ «Manga Tutorials: Emotional Expressions». Rio. Archived from the original on July 29, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c University of Michigan Animae Project. «Emotional Iconography in Animae». Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 52.

- ^ «Original Soundtrack (OST)». Anime News Network. ANN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ Poitras 2000, pp. 44–48.

- ^ Ask John: Why Do Americans Hate Harem Anime? Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. animenation.net. May 20. 2005. Note: fan service and ecchi are often considered the same in wording.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 89.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 50.

- ^ a b Poitras 2000, p. 34.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Poitras 2000, pp. 37–40.

- ^ Poitras 2000, pp. 41–43.

- ^ E. L. Risden: «Miyazaki’s Medieval World: Japanese Medievalism and the Rise of Anime,» in Medievalism NOW[permanent dead link], ed. E.L. Risden, Karl Fugelso, and Richard Utz (special issue of The Year’s Work in Medievalism), 28 [2013]

- ^ Poitras 2000, pp. 45–49.

- ^ «Oldest TV Anime’s Color Screenshots Posted». Anime News Network. June 19, 2013. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Poitras 2000, p. 14.

- ^ «Original Animation Video (OAV/OVA)». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ «Original Net Anime (ONA)». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Poitras 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Ziegler, John R.; Richards, Leah (January 9, 2020). Representation in Steven Universe. Springer Nature. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-030-31881-9.

- ^ a b c d Brenner 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Justin Sevakis (March 5, 2012). «The Anime Economy — Part 1: Let’s Make An Anime!». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c Kobayashi, Akira (September 5, 2016). «Movie version of Osamu Tezuka’s ‘Black Jack’ coming to China». Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Gross

- «Spirited Away (2002) – International Box Office Results». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

-

- North American gross: $10,055,859

- Japanese gross: $229,607,878 (March 31, 2002)

- Other territories: $28,940,019

Japanese gross

- Schwarzacher, Lukas (February 17, 2002). «Japan box office ‘Spirited Away’«. Variety. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

-

- End of 2001: $227 million

- Schwarzacher, Lukas (February 16, 2003). «H’wood eclipses local fare». Variety. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2014.

-

- Across 2001 and 2002: $270 million

- Schilling, Mark (May 16, 2008). «Miyazaki’s animated pic to open this summer». Variety. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

-

- As of 2008: $290 million

- ^ «7 Animes». Archived from the original on January 31, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ «Shinkai’s ‘your name.’ Tops Spirited Away as Highest Grossing Anime Film Worldwide». Anime News Network. January 17, 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b ADV Court Documents Reveal Amounts Paid for 29 Anime Titles Archived April 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Anime Economy Part 3: Digital Pennies Archived May 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sevakis, Justin (September 9, 2016). «Why Are Funimation And Crunchyroll Getting Married?». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ «America’s 2009 Anime Market Pegged at US$2.741 Billion». Anime News Network. April 15, 2011. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Brenner 2007, p. 18.

- ^ «Pokemon Case Study». W3.salemstate.edu. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ^ Oppliger, John (February 24, 2012). «Ask John: Why Does Dubbing Cost So Much?». AnimeNation. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Brenner 2007, p. 206.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 207.

- ^ a b Wurm, Alicia (February 18, 2014). «Anime and the Internet: The Impact of Fansubbing». Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ «Japanese anime: From ‘Disney of the East’ to a global industry worth billions». CNN. July 29, 2019.

- ^ «Japan’s anime goes global:Sony’s new weapon to take on Netflix». Financial times. January 24, 2021.

- ^ «Is There Anything in the Way of Japanese Anime Becoming a Global $30B Market in the Next 5 Years?». Linkedin. May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c «Scanning the Media». J-Marketing. JMR生活総合研究所. February 15, 2005. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2005.

- ^ Kearns, John (2008). Translator and Interpreter Training: Issues, Methods and Debates. A & C Black. p. 159. ISBN 9781441140579. Archived from the original on February 11, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ a b «World-wide Anime Market Worth $100 Billion». Anime News Network. February 19, 2005. Archived from the original on May 26, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ «Anime a $21bn market – in China». Nikkei Asian Review. May 2, 2017. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Chen, Lulu Yilun (March 18, 2016). «Tencent taps ninja Naruto to chase China’s $31 billion anime market». The Japan Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ «Anime Market Size to Worth Around US$ 48.3 Billion by 2030». GlobeNewswire. October 22, 2021.

- ^ «The export value of anime has more than quadrupled «under the Abe administration» and reached the first trillion yen scale». Hatena Blog(In Japanese). December 15, 2019.

- ^ Brenner 2007, pp. 257–258.

- ^ «The dark side of Japan’s anime industry». Vox. July 2, 2019.

- ^ «Anime is Booming. So Why Are Animators Living in Poverty?». The New York Times. February 24, 2021. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- ^ «Despite global anime market’s explosive growth, Japan’s animators continue to live in poverty». Firstpost. March 2, 2021.

- ^ Liu, Narayan (October 3, 2021). «Japan’s New Prime Minister Is a Demon Slayer Fan, Plans to Support Manga and Anime». Comic Book Resources. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ «MAPPA Offers Chainsaw Man Animators Higher Pay, Better Benefits». CBR. August 19, 2021.

- ^ «Anime Industry Report 2020 Summary». 日本動画協会 (in Japanese). Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ «The 25 Biggest Geek Culture Conventions in the World». overmental.com. August 14, 2015.

- ^ Pellitteri, Marco (2014). «The Italian anime boom: The outstanding success of Japanese animation in Italy, 1978–1984». Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies. 2 (3): 363–381. doi:10.1386/jicms.2.3.363_1. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Bendazzi 2015, p. 363.

- ^ Leonard, Sean (September 1, 2005). «Progress against the law: Anime and fandom, with the key to the globalization of culture». International Journal of Cultural Studies. 8 (3): 281–305. doi:10.1177/1367877905055679. S2CID 154124888.

- ^ «How ‘Akira’ Has Influenced All Your Favourite TV, Film and Music». VICE. September 21, 2016. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ «‘Akira’ Is Frequently Cited as Influential. Why Is That?». Film School Rejects. April 3, 2017. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Phipps, Lang (October 6, 1997). «Is Amano the Best Artist You’ve Never Heard Of?». New York Magazine. Vol. 30, no. 38. pp. 45–48 (47). ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ «Netflix is Currently Funding 30 Original Anime Productions». Forbes.

- ^ «Anime is one of the biggest fronts in the streaming wars». The Verge. December 23, 2019.

- ^ Van der Sar, Ernesto (August 15, 2020). «Piracy Giants KissAnime and KissManga Shut Down». TorrentFreak. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Morrissy, Kim (August 19, 2020). «Southeast Asia, India Fans Disproportionately Affected by Pirate Site KissAnime Closure». Anime News Network. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ «The world is watching more anime and streaming services are buying». The Wall Street Journal. November 14, 2020.

- ^ «Streaming and covid-19 have entrenched anime’s global popularity». The Economist. June 5, 2021.

- ^ «Exploring the Anime and Manga Global Takeover». Brandwatch. August 24, 2021.

- ^ «Funimation Expands Streaming Service to Colombia, Chile, Peru». Anime News Network. June 19, 2021.

- ^ «Crunchyroll announces major One Piece catalog expansion across international regions». Crunchyroll. February 22, 2020.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (October 27, 2020). «Japanese Anime Is Growing Success Story for Netflix». Variety. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ «US audiences can’t get enough of Japan’s anime action shows». Bloomberg. May 12, 2021.

- ^ «‘Ghost in the Shell SAC_2045,’ ‘JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure’ Return as Netflix Reveals 40 Anime Titles for 2022″. Variety. March 28, 2022.

- ^ «Netflix: More Than Half of Members Globally Watched ‘Anime’ Last Year». Anime News Network. March 30, 2022.

- ^ «Anime and Asian series dominate 4th Annual Global TV Demand Awards, highlighting industry and consumer trends towards international content». WFMZ-TV. January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ «Anime and Asian series dominate 4th Annual Global TV Demand Awards, highlighting industry and consumer trends towards international content». Parrot Analytics. January 25, 2022.

- ^ «Anime and K-pop fuel language-learning boom». Taipei Times. December 30, 2021.

- ^ «10 Anime That Inspired The Making Of Movies In Hollywood». Screenrant. January 20, 2021.

- ^ «Why Hollywood adaptations of anime movies keep flopping». BusinessInsider. January 11, 2019.

- ^ «Why Hollywood should leave anime out of its live-action remake obsession». CNBC. August 10, 2019.

- ^ «Alita: Battle Angel Was (Just) A Box Office Success». Screenrant. March 12, 2019.

- ^ «Alita Wasn’t the Bomb Everyone Expected, a Sequel Is Very Possible». MovieWeb. April 2, 2019.

- ^ «How Japan’s global image morphed from military empire to eccentric pop-culture superpower». Quartz. May 27, 2020.

- ^ «President Obama thanks Japanese leader for karaoke, emoji». The Washington Post. April 28, 2015.

- ^ Laing, Aislinn (July 16, 2020). «Pink-caped Chilean deputy brings lawmakers to their feet to celebrate coronavirus bill». Reuters. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Quinteros, Paulo (July 15, 2020). «Hokage Jiles: La diputada celebró la aprobación del proyecto del 10% corriendo a lo Naruto». La Tercera. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ «Peruvian Politicians Cosplay Anime Characters to Score the «Otaku» Vote». Anime News Network. April 14, 2021.

- ^ «Harnessing the Power of Anime as an Outstanding Marketing Solution». Dentsu. March 1, 2019.

- ^ «Anime industry in Japan — statistics and facts». Statista. January 17, 2022.

- ^ «Crunchyroll Market Research: Only 6% of Gen Z Don’t Know What Anime Is». Anime News Network. July 9, 2021.

- ^ «Anime Poll Reveals How Popular It Has Become with Gen Z». CBR. July 11, 2021.

- ^ Poitras 2000, p. 73.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 211.

- ^ Brenner 2007, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Davis, Jesse Christian. «Japanese animation in America and its fans» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ «Otaku or Weeb: The Differences Between Anime Fandom’s Most Famous Insults». CBR. May 31, 2020.

- ^ Brenner 2007, p. 201–205.

- ^ Liu, Shang; Lai, Dan; Li, Zhiyong (March 1, 2022). «The identity construction of Chinese anime pilgrims». Annals of Tourism Research. 93: 103373. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2022.103373. ISSN 0160-7383. S2CID 246853441.

- ^ «/r/Anime». Reddit.

- ^ «Twitter trending topics: How they work and how to use them». Sprout Social. March 15, 2021.

- ^ «Jujutsu Kaisen Tops Squid Game, Wandavision in Social Media’s 2021 Discussions». CBR. December 9, 2021.

- ^ «Why Some Fans Watch Anime At Double Speed». Kotaku Australia. Gawker Media. January 11, 2018. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Orsini, Lauren. «MyAnimeList Passes Third Day Of Unexpected Downtime». Forbes. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ «BTS & 9 Other Celebrities Who Are Huge Anime Fans». CBR. March 13, 2021.

- ^ MacWilliams 2008, p. 307.

- ^ a b O’Brien, Chris (July 30, 2012). «Can Americans Make Anime?». The Escapist. The Escapist. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ «What is anime?». ANN. July 26, 2002. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ «Aaron McGruder — The Boondocks Interview». Troy Rogers. UnderGroundOnline. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

We looked at Samurai Champloo and Cowboy Bebop to make this work for black comedy and it would be a remarkable thing.

- ^ «Ten Minutes with «Megas XLR»«. October 13, 2004. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- ^ «STW company background summary». Archived from the original on August 13, 2007.

- ^ «How should the word Anime be defined?». AnimeNation. May 15, 2006. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- ^ Fakhruddin, Mufaddal (April 9, 2013). «‘Torkaizer’, Middle East’s First Anime Show». IGN. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ Green, Scott (December 26, 2013). «VIDEO: An Updated Look at «Middle East’s First Anime»«. Crunchyroll. Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ Schley, Matt (November 5, 2015). «Netflix May Produce Anime». OtakuUSA. OtakuUSA. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Barder, Ollie. «Netflix Is Interested In Producing Its Own Anime». Forbes. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Castillo, Michelle (August 15, 2014). «American-Made Anime From Rooster Teeth Gets Licensed In Japan». AdWeek. AdWeek. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ Lazar, Shira (August 7, 2013). «Roosterteeth Adds Anime RWBY To YouTube Slate (WATCH)». Huffingtonpost. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Rush, Amanda (July 12, 2013). «FEATURE: Inside Rooster Teeth’s «RWBY»«. Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ^ «海外3DCGアニメ『RWBY』吹き替え版BD・DVD販売決定! コミケで発表». KAI-YOU. August 16, 2014. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, p. 110

- ^ Marc Steinberg, Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan

- ^ Denison, Rayna. «Manga Movies Project Report 1 — Transmedia Japanese Franchising». Academia.edu. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- ^ Steinberg, p. vi Archived October 31, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hutchins, Robert (June 26, 2018). «‘Anime will only get stronger,’ as Pokémon beats Marvel as highest grossing franchise». Licensing.biz. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

Sources

- Baricordi, Andrea; de Giovanni, Massimiliano; Pietroni, Andrea; Rossi, Barbara; Tunesi, Sabrina (December 2000). Anime: A Guide to Japanese Animation (1958–1988). Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Protoculture Inc. ISBN 2-9805759-0-9.

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (October 23, 2015). Animation: A World History: Volume II: The Birth of a Style — The Three Markets. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-3175-1991-1.

- Brenner, Robin (2007). Understanding Manga and Anime. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-59158-332-5.

- Cavallaro, Dani (2006). The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2369-9.

- Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917. Berkeley, Calif: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-10-5.

- Craig, Timothy J. (2000). Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, NY [u.a.]: Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0561-0.

- Drazen, Patrick (2003). Anime Explosion!: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1611720136.

- Kinsella, Sharon (2000). Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824823184.

- Le Blanc, Michelle; Odell, Colin (2017). Akira. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1844578108.

- MacWilliams, Mark W. (2008). Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1602-9.

- Napier, Susan J. (2005). Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 1-4039-7051-3.

- Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- Poitras, Gilles (1998). Anime Companion. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-32-9.

- Poitras, Gilles (2000). Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-53-2.

- Ruh, Brian (2014). Stray Dog of Anime. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-35567-6.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (August 18, 1997). Manga! Manga!: The World of Japanese Comics (Reprint ed.). Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. ISBN 0-87011-752-1.

- Tobin, Joseph Jay (2004). Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3287-6.

- Green, Ronald S.; Beregeron, Susan J. (2021). «Teaching Cultural, Historical, and Religious Landscapes with the Anime». Education About ASIA. pp. 48–53.

- Chan, Yee-Han; wong, Ngan-Ling; Ng, Lee-Luan (2017). «Japanese Language Student’s Perception of Using Anime as a Teaching Tool». Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics 7.1. pp. 93–104.

- Han, Chan Yee; Ling, Wong Ngan (2017). «The Use of Anime in Teaching Japanese as a Foreign Language». Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Technology 5.2. pp. 66–78.

- Junjie, Shan; Nishihara, Yoko; Yamanishi, Ryosuke (2018). «A System for Japanese Listening Training Support With Watching Japanese Anime Scenes». Procedia Computer Science 126. Knowledge-Based and Intelligent Information & Engineering Systems: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference, KES-2018, Belgrade, Serbia. Vol. 126. pp. 947–956. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2018.08.029.

External links

- Anime at Curlie

Anime and manga in Japan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Not to be confused with Amine.

Anime (Japanese: アニメ, IPA: [aɲime] (listen)) is hand-drawn and computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside of Japan and in English, anime refers specifically to animation produced in Japan.[1] However, in Japan and in Japanese, anime (a term derived from a shortening of the English word animation) describes all animated works, regardless of style or origin. Animation produced outside of Japan with similar style to Japanese animation is commonly referred to as anime-influenced animation.

The earliest commercial Japanese animations date to 1917. A characteristic art style emerged in the 1960s with the works of cartoonist Osamu Tezuka and spread in following decades, developing a large domestic audience. Anime is distributed theatrically, through television broadcasts, directly to home media, and over the Internet. In addition to original works, anime are often adaptations of Japanese comics (manga), light novels, or video games. It is classified into numerous genres targeting various broad and niche audiences.

Anime is a diverse medium with distinctive production methods that have adapted in response to emergent technologies. It combines graphic art, characterization, cinematography, and other forms of imaginative and individualistic techniques.[2] Compared to Western animation, anime production generally focuses less on movement, and more on the detail of settings and use of «camera effects», such as panning, zooming, and angle shots.[2] Diverse art styles are used, and character proportions and features can be quite varied, with a common characteristic feature being large and emotive eyes.[3]

The anime industry consists of over 430 production companies, including major studios such as Studio Ghibli, Kyoto Animation, Sunrise, Bones, Ufotable, MAPPA, Wit Studio, CoMix Wave Films, Production I.G and Toei Animation. Since the 1980s, the medium has also seen widespread international success with the rise of foreign dubbed, subtitled programming, and since the 2010s its increasing distribution through streaming services and a widening demographic embrace of anime culture, both within Japan and worldwide.[4] As of 2016, Japanese animation accounted for 60% of the world’s animated television shows.[5]

Etymology

As a type of animation, anime is an art form that comprises many genres found in other mediums; it is sometimes mistakenly classified as a genre itself.[6] In Japanese, the term anime is used to refer to all animated works, regardless of style or origin.[7] English-language dictionaries typically define anime ()[8] as «a style of Japanese animation»[9] or as «a style of animation originating in Japan».[10] Other definitions are based on origin, making production in Japan a requisite for a work to be considered «anime».[11]

The etymology of the term anime is disputed. The English word «animation» is written in Japanese katakana as アニメーション (animēshon) and as アニメ (anime, pronounced [a.ɲi.me] (listen)) in its shortened form.[11] Some sources claim that the term is derived from the French term for animation dessin animé («cartoon», literally ‘animated drawing’),[12] but others believe this to be a myth derived from the popularity of anime in France in the late 1970s and 1980s.[11]

In English, anime—when used as a common noun—normally functions as a mass noun. (For example: «Do you watch anime?» or «How much anime have you collected?»)[13][14] As with a few other Japanese words, such as saké and Pokémon, English texts sometimes spell anime as animé (as in French), with an acute accent over the final e, to cue the reader to pronounce the letter, not to leave it silent as English orthography may suggest. Prior to the widespread use of anime, the term Japanimation was prevalent throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In the mid-1980s, the term anime began to supplant Japanimation;[15] in general, the latter term now only appears in period works where it is used to distinguish and identify Japanese animation.[16]

History

Precursors

Emakimono and kagee are considered precursors of Japanese animation.[17] Emakimono was common in the eleventh century. Traveling storytellers narrated legends and anecdotes while the emakimono was unrolled from the right to left with chronological order, as a moving panorama.[17] Kagee was popular during the Edo period and originated from the shadows play of China.[17] Magic lanterns from the Netherlands were also popular in the eighteenth century.[17] The paper play called Kamishibai surged in the twelfth century and remained popular in the street theater until the 1930s.[17] Puppets of the bunraku theater and ukiyo-e prints are considered ancestors of characters of most Japanese animations.[17] Finally, mangas were a heavy inspiration for anime. Cartoonists Kitzawa Rakuten and Okamoto Ippei used film elements in their strips.[17]

Pioneers

A frame from Namakura Gatana (1917), the oldest surviving Japanese animated short film made for cinemas

Animation in Japan began in the early 20th century, when filmmakers started to experiment with techniques pioneered in France, Germany, the United States, and Russia.[12] A claim for the earliest Japanese animation is Katsudō Shashin (c. 1907),[18] a private work by an unknown creator.[19] In 1917, the first professional and publicly displayed works began to appear; animators such as Ōten Shimokawa, Seitarō Kitayama, and Jun’ichi Kōuchi (considered the «fathers of anime») produced numerous films, the oldest surviving of which is Kōuchi’s Namakura Gatana.[20] Many early works were lost with the destruction of Shimokawa’s warehouse in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.[21]

By the mid-1930s, animation was well-established in Japan as an alternative format to the live-action industry. It suffered competition from foreign producers, such as Disney, and many animators, including Noburō Ōfuji and Yasuji Murata, continued to work with cheaper cutout animation rather than cel animation.[22] Other creators, including Kenzō Masaoka and Mitsuyo Seo, nevertheless made great strides in technique, benefiting from the patronage of the government, which employed animators to produce educational shorts and propaganda.[23] In 1940, the government dissolved several artists’ organizations to form the Shin Nippon Mangaka Kyōkai.[a][24] The first talkie anime was Chikara to Onna no Yo no Naka (1933), a short film produced by Masaoka.[25][26] The first feature-length anime film was Momotaro: Sacred Sailors (1945), produced by Seo with a sponsorship from the Imperial Japanese Navy.[27] The 1950s saw a proliferation of short, animated advertisements created for television.[28]

Modern era

Frame from the opening sequence of Tezuka’s 1963 TV series Astro Boy

In the 1960s, manga artist and animator Osamu Tezuka adapted and simplified Disney animation techniques to reduce costs and limit frame counts in his productions.[29] Originally intended as temporary measures to allow him to produce material on a tight schedule with an inexperienced staff, many of his limited animation practices came to define the medium’s style.[30] Three Tales (1960) was the first anime film broadcast on television;[31] the first anime television series was Instant History (1961–64).[32] An early and influential success was Astro Boy (1963–66), a television series directed by Tezuka based on his manga of the same name. Many animators at Tezuka’s Mushi Production later established major anime studios (including Madhouse, Sunrise, and Pierrot).

The 1970s saw growth in the popularity of manga, many of which were later animated. Tezuka’s work—and that of other pioneers in the field—inspired characteristics and genres that remain fundamental elements of anime today. The giant robot genre (also known as «mecha»), for instance, took shape under Tezuka, developed into the super robot genre under Go Nagai and others, and was revolutionized at the end of the decade by Yoshiyuki Tomino, who developed the real robot genre.[33] Robot anime series such as Gundam and Super Dimension Fortress Macross became instant classics in the 1980s, and the genre remained one of the most popular in the following decades.[34] The bubble economy of the 1980s spurred a new era of high-budget and experimental anime films, including Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (1987), and Akira (1988).[35]

Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995), a television series produced by Gainax and directed by Hideaki Anno, began another era of experimental anime titles, such as Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Cowboy Bebop (1998). In the 1990s, anime also began attracting greater interest in Western countries; major international successes include Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z, both of which were dubbed into more than a dozen languages worldwide. In 2003, Spirited Away, a Studio Ghibli feature film directed by Hayao Miyazaki, won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards. It later became the highest-grossing anime film,[b] earning more than $355 million. Since the 2000s, an increased number of anime works have been adaptations of light novels and visual novels; successful examples include The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya and Fate/stay night (both 2006). Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train became the highest-grossing Japanese film and one of the world’s highest-grossing films of 2020.[36] It also became the fastest grossing film in Japanese cinema, because in 10 days it made 10 billion yen ($95.3m; £72m).[36] It beat the previous record of Spirited Away which took 25 days.[36]

Attributes

Anime differs from other forms of animation by its art styles, methods of animation, its production, and its process. Visually, anime works exhibit a wide variety of art styles, differing between creators, artists, and studios.[37] While no single art style predominates anime as a whole, they do share some similar attributes in terms of animation technique and character design.