|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Silver | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | lustrous white metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ag) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Silver in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 4d10 5s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1234.93 K (961.78 °C, 1763.2 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2435 K (2162 °C, 3924 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 10.49 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 9.320 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 11.28 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | 254 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.350 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0,[2] +1, +2, +3 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.93 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 144 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 145±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 172 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of silver |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centred cubic (fcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2680 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 18.9 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 429 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal diffusivity | 174 mm2/s (at 300 K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 15.87 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −19.5×10−6 cm3/mol (296 K)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 83 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 30 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 100 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.37 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 251 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 206–250 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-22-4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | before 5000 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Ag»: from Latin argentum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of silver

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

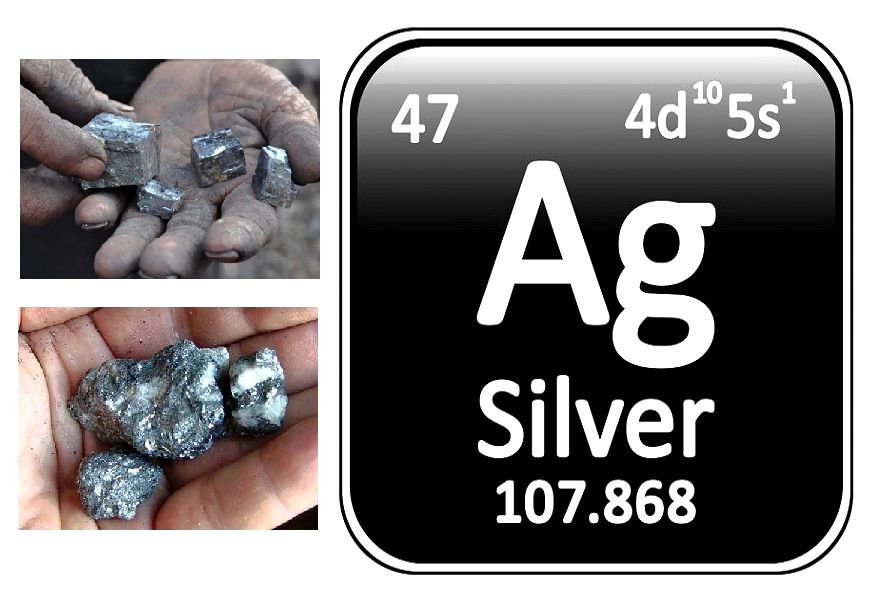

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin argentum, derived from the Proto-Indo-European h₂erǵ: «shiny» or «white») and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal.[5] The metal is found in the Earth’s crust in the pure, free elemental form («native silver»), as an alloy with gold and other metals, and in minerals such as argentite and chlorargyrite. Most silver is produced as a byproduct of copper, gold, lead, and zinc refining.

Silver has long been valued as a precious metal. Silver metal is used in many bullion coins, sometimes alongside gold:[6] while it is more abundant than gold, it is much less abundant as a native metal.[7] Its purity is typically measured on a per-mille basis; a 94%-pure alloy is described as «0.940 fine». As one of the seven metals of antiquity, silver has had an enduring role in most human cultures.

Other than in currency and as an investment medium (coins and bullion), silver is used in solar panels, water filtration, jewellery, ornaments, high-value tableware and utensils (hence the term «silverware»), in electrical contacts and conductors, in specialized mirrors, window coatings, in catalysis of chemical reactions, as a colorant in stained glass, and in specialized confectionery. Its compounds are used in photographic and X-ray film. Dilute solutions of silver nitrate and other silver compounds are used as disinfectants and microbiocides (oligodynamic effect), added to bandages, wound-dressings, catheters, and other medical instruments.

Characteristics

Silver is extremely ductile, and can be drawn into a wire one atom wide.[8]

Silver is similar in its physical and chemical properties to its two vertical neighbours in group 11 of the periodic table: copper, and gold. Its 47 electrons are arranged in the configuration [Kr]4d105s1, similarly to copper ([Ar]3d104s1) and gold ([Xe]4f145d106s1); group 11 is one of the few groups in the d-block which has a completely consistent set of electron configurations.[9] This distinctive electron configuration, with a single electron in the highest occupied s subshell over a filled d subshell, accounts for many of the singular properties of metallic silver.[10]

Silver is a relatively soft and extremely ductile and malleable transition metal, though it is slightly less malleable than gold. Silver crystallizes in a face-centered cubic lattice with bulk coordination number 12, where only the single 5s electron is delocalized, similarly to copper and gold.[11] Unlike metals with incomplete d-shells, metallic bonds in silver are lacking a covalent character and are relatively weak. This observation explains the low hardness and high ductility of single crystals of silver.[12]

Silver has a brilliant, white, metallic luster that can take a high polish,[13] and which is so characteristic that the name of the metal itself has become a colour name.[10] Protected silver has greater optical reflectivity than aluminium at all wavelengths longer than ~450 nm.[14] At wavelengths shorter than 450 nm, silver’s reflectivity is inferior to that of aluminium and drops to zero near 310 nm.[15]

Very high electrical and thermal conductivity are common to the elements in group 11, because their single s electron is free and does not interact with the filled d subshell, as such interactions (which occur in the preceding transition metals) lower electron mobility.[16] The thermal conductivity of silver is among the highest of all materials, although the thermal conductivity of carbon (in the diamond allotrope) and superfluid helium-4 are higher.[9] The electrical conductivity of silver is the highest of all metals, greater even than copper. Silver also has the lowest contact resistance of any metal.[9] Silver is rarely used for its electrical conductivity, due to its high cost, although an exception is in radio-frequency engineering, particularly at VHF and higher frequencies where silver plating improves electrical conductivity because those currents tend to flow on the surface of conductors rather than through the interior. During World War II in the US, 13540 tons of silver were used for the electromagnets in calutrons for enriching uranium, mainly because of the wartime shortage of copper.[17][18][19]

Silver readily forms alloys with copper, gold, and zinc. Zinc-silver alloys with low zinc concentration may be considered as face-centred cubic solid solutions of zinc in silver, as the structure of the silver is largely unchanged while the electron concentration rises as more zinc is added. Increasing the electron concentration further leads to body-centred cubic (electron concentration 1.5), complex cubic (1.615), and hexagonal close-packed phases (1.75).[11]

Isotopes

Naturally occurring silver is composed of two stable isotopes, 107Ag and 109Ag, with 107Ag being slightly more abundant (51.839% natural abundance). This almost equal abundance is rare in the periodic table. The atomic weight is 107.8682(2) u;[20][21] this value is very important because of the importance of silver compounds, particularly halides, in gravimetric analysis.[20] Both isotopes of silver are produced in stars via the s-process (slow neutron capture), as well as in supernovas via the r-process (rapid neutron capture).[22]

Twenty-eight radioisotopes have been characterized, the most stable being 105Ag with a half-life of 41.29 days, 111Ag with a half-life of 7.45 days, and 112Ag with a half-life of 3.13 hours. Silver has numerous nuclear isomers, the most stable being 108mAg (t1/2 = 418 years), 110mAg (t1/2 = 249.79 days) and 106mAg (t1/2 = 8.28 days). All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives of less than an hour, and the majority of these have half-lives of less than three minutes.[23]

Isotopes of silver range in relative atomic mass from 92.950 u (93Ag) to 129.950 u (130Ag);[24] the primary decay mode before the most abundant stable isotope, 107Ag, is electron capture and the primary mode after is beta decay. The primary decay products before 107Ag are palladium (element 46) isotopes, and the primary products after are cadmium (element 48) isotopes.[23]

The palladium isotope 107Pd decays by beta emission to 107Ag with a half-life of 6.5 million years. Iron meteorites are the only objects with a high-enough palladium-to-silver ratio to yield measurable variations in 107Ag abundance. Radiogenic 107Ag was first discovered in the Santa Clara meteorite in 1978.[25] 107Pd–107Ag correlations observed in bodies that have clearly been melted since the accretion of the Solar System must reflect the presence of unstable nuclides in the early Solar System.[26]

Chemistry

| Oxidation state |

Coordination number |

Stereochemistry | Representative compound |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (d10s1) | 3 | Planar | Ag(CO)3 |

| 1 (d10) | 2 | Linear | [Ag(CN)2]− |

| 3 | Trigonal planar | AgI(PEt2Ar)2 | |

| 4 | Tetrahedral | [Ag(diars)2]+ | |

| 6 | Octahedral | AgF, AgCl, AgBr | |

| 2 (d9) | 4 | Square planar | [Ag(py)4]2+ |

| 3 (d8) | 4 | Square planar | [AgF4]− |

| 6 | Octahedral | [AgF6]3− |

Silver is a rather unreactive metal. This is because its filled 4d shell is not very effective in shielding the electrostatic forces of attraction from the nucleus to the outermost 5s electron, and hence silver is near the bottom of the electrochemical series (E0(Ag+/Ag) = +0.799 V).[10] In group 11, silver has the lowest first ionization energy (showing the instability of the 5s orbital), but has higher second and third ionization energies than copper and gold (showing the stability of the 4d orbitals), so that the chemistry of silver is predominantly that of the +1 oxidation state, reflecting the increasingly limited range of oxidation states along the transition series as the d-orbitals fill and stabilize.[28] Unlike copper, for which the larger hydration energy of Cu2+ as compared to Cu+ is the reason why the former is the more stable in aqueous solution and solids despite lacking the stable filled d-subshell of the latter, with silver this effect is swamped by its larger second ionisation energy. Hence, Ag+ is the stable species in aqueous solution and solids, with Ag2+ being much less stable as it oxidizes water.[28]

Most silver compounds have significant covalent character due to the small size and high first ionization energy (730.8 kJ/mol) of silver.[10] Furthermore, silver’s Pauling electronegativity of 1.93 is higher than that of lead (1.87), and its electron affinity of 125.6 kJ/mol is much higher than that of hydrogen (72.8 kJ/mol) and not much less than that of oxygen (141.0 kJ/mol).[29] Due to its full d-subshell, silver in its main +1 oxidation state exhibits relatively few properties of the transition metals proper from groups 4 to 10, forming rather unstable organometallic compounds, forming linear complexes showing very low coordination numbers like 2, and forming an amphoteric oxide[30] as well as Zintl phases like the post-transition metals.[31] Unlike the preceding transition metals, the +1 oxidation state of silver is stable even in the absence of π-acceptor ligands.[28]

Silver does not react with air, even at red heat, and thus was considered by alchemists as a noble metal, along with gold. Its reactivity is intermediate between that of copper (which forms copper(I) oxide when heated in air to red heat) and gold. Like copper, silver reacts with sulfur and its compounds; in their presence, silver tarnishes in air to form the black silver sulfide (copper forms the green sulfate instead, while gold does not react). Unlike copper, silver will not react with the halogens, with the exception of fluorine gas, with which it forms the difluoride. While silver is not attacked by non-oxidizing acids, the metal dissolves readily in hot concentrated sulfuric acid, as well as dilute or concentrated nitric acid. In the presence of air, and especially in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, silver dissolves readily in aqueous solutions of cyanide.[27]

The three main forms of deterioration in historical silver artifacts are tarnishing, formation of silver chloride due to long-term immersion in salt water, as well as reaction with nitrate ions or oxygen. Fresh silver chloride is pale yellow, becoming purplish on exposure to light; it projects slightly from the surface of the artifact or coin. The precipitation of copper in ancient silver can be used to date artifacts, as copper is nearly always a constituent of silver alloys.[32]

Silver metal is attacked by strong oxidizers such as potassium permanganate (KMnO

4) and potassium dichromate (K

2Cr

2O

7), and in the presence of potassium bromide (KBr). These compounds are used in photography to bleach silver images, converting them to silver bromide that can either be fixed with thiosulfate or redeveloped to intensify the original image. Silver forms cyanide complexes (silver cyanide) that are soluble in water in the presence of an excess of cyanide ions. Silver cyanide solutions are used in electroplating of silver.[33]

The common oxidation states of silver are (in order of commonness): +1 (the most stable state; for example, silver nitrate, AgNO3); +2 (highly oxidising; for example, silver(II) fluoride, AgF2); and even very rarely +3 (extreme oxidising; for example, potassium tetrafluoroargentate(III), KAgF4).[34] The +3 state requires very strong oxidising agents to attain, such as fluorine or peroxodisulfate, and some silver(III) compounds react with atmospheric moisture and attack glass.[35] Indeed, silver(III) fluoride is usually obtained by reacting silver or silver monofluoride with the strongest known oxidizing agent, krypton difluoride.[36]

Compounds

Oxides and chalcogenides

Silver and gold have rather low chemical affinities for oxygen, lower than copper, and it is therefore expected that silver oxides are thermally quite unstable. Soluble silver(I) salts precipitate dark-brown silver(I) oxide, Ag2O, upon the addition of alkali. (The hydroxide AgOH exists only in solution; otherwise it spontaneously decomposes to the oxide.) Silver(I) oxide is very easily reduced to metallic silver, and decomposes to silver and oxygen above 160 °C.[37] This and other silver(I) compounds may be oxidized by the strong oxidizing agent peroxodisulfate to black AgO, a mixed silver(I,III) oxide of formula AgIAgIIIO2. Some other mixed oxides with silver in non-integral oxidation states, namely Ag2O3 and Ag3O4, are also known, as is Ag3O which behaves as a metallic conductor.[37]

Silver(I) sulfide, Ag2S, is very readily formed from its constituent elements and is the cause of the black tarnish on some old silver objects. It may also be formed from the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with silver metal or aqueous Ag+ ions. Many non-stoichiometric selenides and tellurides are known; in particular, AgTe~3 is a low-temperature superconductor.[37]

Halides

The only known dihalide of silver is the difluoride, AgF2, which can be obtained from the elements under heat. A strong yet thermally stable and therefore safe fluorinating agent, silver(II) fluoride is often used to synthesize hydrofluorocarbons.[38]

In stark contrast to this, all four silver(I) halides are known. The fluoride, chloride, and bromide have the sodium chloride structure, but the iodide has three known stable forms at different temperatures; that at room temperature is the cubic zinc blende structure. They can all be obtained by the direct reaction of their respective elements.[38] As the halogen group is descended, the silver halide gains more and more covalent character, solubility decreases, and the color changes from the white chloride to the yellow iodide as the energy required for ligand-metal charge transfer (X−Ag+ → XAg) decreases.[38] The fluoride is anomalous, as the fluoride ion is so small that it has a considerable solvation energy and hence is highly water-soluble and forms di- and tetrahydrates.[38] The other three silver halides are highly insoluble in aqueous solutions and are very commonly used in gravimetric analytical methods.[20] All four are photosensitive (though the monofluoride is so only to ultraviolet light), especially the bromide and iodide which photodecompose to silver metal, and thus were used in traditional photography.[38] The reaction involved is:[39]

- X− + hν → X + e− (excitation of the halide ion, which gives up its extra electron into the conduction band)

- Ag+ + e− → Ag (liberation of a silver ion, which gains an electron to become a silver atom)

The process is not reversible because the silver atom liberated is typically found at a crystal defect or an impurity site, so that the electron’s energy is lowered enough that it is «trapped».[39]

Other inorganic compounds

Silver crystals forming on a copper surface in a silver nitrate solution. Video by Maxim Bilovitskiy

Crystals of silver nitrate

White silver nitrate, AgNO3, is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, especially the halides, and is much less sensitive to light. It was once called lunar caustic because silver was called luna by the ancient alchemists, who believed that silver was associated with the Moon.[40][41] It is often used for gravimetric analysis, exploiting the insolubility of the heavier silver halides which it is a common precursor to.[20] Silver nitrate is used in many ways in organic synthesis, e.g. for deprotection and oxidations. Ag+ binds alkenes reversibly, and silver nitrate has been used to separate mixtures of alkenes by selective absorption. The resulting adduct can be decomposed with ammonia to release the free alkene.[42]

Yellow silver carbonate, Ag2CO3 can be easily prepared by reacting aqueous solutions of sodium carbonate with a deficiency of silver nitrate.[43] Its principal use is for the production of silver powder for use in microelectronics. It is reduced with formaldehyde, producing silver free of alkali metals:[44]

- Ag2CO3 + CH2O → 2 Ag + 2 CO2 + H2

Silver carbonate is also used as a reagent in organic synthesis such as the Koenigs-Knorr reaction. In the Fétizon oxidation, silver carbonate on celite acts as an oxidising agent to form lactones from diols. It is also employed to convert alkyl bromides into alcohols.[43]

Silver fulminate, AgCNO, a powerful, touch-sensitive explosive used in percussion caps, is made by reaction of silver metal with nitric acid in the presence of ethanol. Other dangerously explosive silver compounds are silver azide, AgN3, formed by reaction of silver nitrate with sodium azide,[45] and silver acetylide, Ag2C2, formed when silver reacts with acetylene gas in ammonia solution.[28] In its most characteristic reaction, silver azide decomposes explosively, releasing nitrogen gas: given the photosensitivity of silver salts, this behaviour may be induced by shining a light on its crystals.[28]

- 2 AgN

3 (s) → 3 N

2 (g) + 2 Ag (s)

Coordination compounds

Structure of the diamminesilver(I) complex, [Ag(NH3)2]+

Silver complexes tend to be similar to those of its lighter homologue copper. Silver(III) complexes tend to be rare and very easily reduced to the more stable lower oxidation states, though they are slightly more stable than those of copper(III). For instance, the square planar periodate [Ag(IO5OH)2]5− and tellurate [Ag{TeO4(OH)2}2]5− complexes may be prepared by oxidising silver(I) with alkaline peroxodisulfate. The yellow diamagnetic [AgF4]− is much less stable, fuming in moist air and reacting with glass.[35]

Silver(II) complexes are more common. Like the valence isoelectronic copper(II) complexes, they are usually square planar and paramagnetic, which is increased by the greater field splitting for 4d electrons than for 3d electrons. Aqueous Ag2+, produced by oxidation of Ag+ by ozone, is a very strong oxidising agent, even in acidic solutions: it is stabilized in phosphoric acid due to complex formation. Peroxodisulfate oxidation is generally necessary to give the more stable complexes with heterocyclic amines, such as [Ag(py)4]2+ and [Ag(bipy)2]2+: these are stable provided the counterion cannot reduce the silver back to the +1 oxidation state. [AgF4]2− is also known in its violet barium salt, as are some silver(II) complexes with N— or O-donor ligands such as pyridine carboxylates.[46]

By far the most important oxidation state for silver in complexes is +1. The Ag+ cation is diamagnetic, like its homologues Cu+ and Au+, as all three have closed-shell electron configurations with no unpaired electrons: its complexes are colourless provided the ligands are not too easily polarized such as I−. Ag+ forms salts with most anions, but it is reluctant to coordinate to oxygen and thus most of these salts are insoluble in water: the exceptions are the nitrate, perchlorate, and fluoride. The tetracoordinate tetrahedral aqueous ion [Ag(H2O)4]+ is known, but the characteristic geometry for the Ag+ cation is 2-coordinate linear. For example, silver chloride dissolves readily in excess aqueous ammonia to form [Ag(NH3)2]+; silver salts are dissolved in photography due to the formation of the thiosulfate complex [Ag(S2O3)2]3−; and cyanide extraction for silver (and gold) works by the formation of the complex [Ag(CN)2]−. Silver cyanide forms the linear polymer {Ag–C≡N→Ag–C≡N→}; silver thiocyanate has a similar structure, but forms a zigzag instead because of the sp3-hybridized sulfur atom. Chelating ligands are unable to form linear complexes and thus silver(I) complexes with them tend to form polymers; a few exceptions exist, such as the near-tetrahedral diphosphine and diarsine complexes [Ag(L–L)2]+.[47]

Organometallic

Under standard conditions, silver does not form simple carbonyls, due to the weakness of the Ag–C bond. A few are known at very low temperatures around 6–15 K, such as the green, planar paramagnetic Ag(CO)3, which dimerizes at 25–30 K, probably by forming Ag–Ag bonds. Additionally, the silver carbonyl [Ag(CO)] [B(OTeF5)4] is known. Polymeric AgLX complexes with alkenes and alkynes are known, but their bonds are thermodynamically weaker than even those of the platinum complexes (though they are formed more readily than those of the analogous gold complexes): they are also quite unsymmetrical, showing the weak π bonding in group 11. Ag–C σ bonds may also be formed by silver(I), like copper(I) and gold(I), but the simple alkyls and aryls of silver(I) are even less stable than those of copper(I) (which tend to explode under ambient conditions). For example, poor thermal stability is reflected in the relative decomposition temperatures of AgMe (−50 °C) and CuMe (−15 °C) as well as those of PhAg (74 °C) and PhCu (100 °C).[48]

The C–Ag bond is stabilized by perfluoroalkyl ligands, for example in AgCF(CF3)2.[49] Alkenylsilver compounds are also more stable than their alkylsilver counterparts.[50] Silver-NHC complexes are easily prepared, and are commonly used to prepare other NHC complexes by displacing labile ligands. For example, the reaction of the bis(NHC)silver(I) complex with bis(acetonitrile)palladium dichloride or chlorido(dimethyl sulfide)gold(I):[51]

Intermetallic

Different colors of silver–copper–gold alloys

Silver forms alloys with most other elements on the periodic table. The elements from groups 1–3, except for hydrogen, lithium, and beryllium, are very miscible with silver in the condensed phase and form intermetallic compounds; those from groups 4–9 are only poorly miscible; the elements in groups 10–14 (except boron and carbon) have very complex Ag–M phase diagrams and form the most commercially important alloys; and the remaining elements on the periodic table have no consistency in their Ag–M phase diagrams. By far the most important such alloys are those with copper: most silver used for coinage and jewellery is in reality a silver–copper alloy, and the eutectic mixture is used in vacuum brazing. The two metals are completely miscible as liquids but not as solids; their importance in industry comes from the fact that their properties tend to be suitable over a wide range of variation in silver and copper concentration, although most useful alloys tend to be richer in silver than the eutectic mixture (71.9% silver and 28.1% copper by weight, and 60.1% silver and 28.1% copper by atom).[52]

Most other binary alloys are of little use: for example, silver–gold alloys are too soft and silver–cadmium alloys too toxic. Ternary alloys have much greater importance: dental amalgams are usually silver–tin–mercury alloys, silver–copper–gold alloys are very important in jewellery (usually on the gold-rich side) and have a vast range of hardnesses and colours, silver–copper–zinc alloys are useful as low-melting brazing alloys, and silver–cadmium–indium (involving three adjacent elements on the periodic table) is useful in nuclear reactors because of its high thermal neutron capture cross-section, good conduction of heat, mechanical stability, and resistance to corrosion in hot water.[52]

Etymology

The word «silver» appears in Old English in various spellings, such as seolfor and siolfor. It is cognate with Old High German silabar; Gothic silubr; or Old Norse silfr, all ultimately deriving from Proto-Germanic *silubra. The Balto-Slavic words for silver are rather similar to the Germanic ones (e.g. Russian серебро [serebró], Polish srebro, Lithuanian sidãbras), as is the Celtiberian form silabur. They may have a common Indo-European origin, although their morphology rather suggest a non-Indo-European Wanderwort.[53][54] Some scholars have thus proposed a Paleo-Hispanic origin, pointing to the Basque form zilharr as an evidence.[55]

The chemical symbol Ag is from the Latin word for «silver», argentum (compare Ancient Greek ἄργυρος, árgyros), from the Proto-Indo-European root *h₂erǵ- (formerly reconstructed as *arǵ-), meaning «white» or «shining». This was the usual Proto-Indo-European word for the metal, whose reflexes are missing in Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[54]

History

Silver vase, circa 2400 BC

Silver was one of the seven metals of antiquity that were known to prehistoric humans and whose discovery is thus lost to history.[56] In particular, the three metals of group 11, copper, silver, and gold, occur in the elemental form in nature and were probably used as the first primitive forms of money as opposed to simple bartering.[57] However, unlike copper, silver did not lead to the growth of metallurgy on account of its low structural strength, and was more often used ornamentally or as money.[58] Since silver is more reactive than gold, supplies of native silver were much more limited than those of gold.[57] For example, silver was more expensive than gold in Egypt until around the fifteenth century BC:[59] the Egyptians are thought to have separated gold from silver by heating the metals with salt, and then reducing the silver chloride produced to the metal.[60]

The situation changed with the discovery of cupellation, a technique that allowed silver metal to be extracted from its ores. While slag heaps found in Asia Minor and on the islands of the Aegean Sea indicate that silver was being separated from lead as early as the 4th millennium BC,[9] and one of the earliest silver extraction centres in Europe was Sardinia in the early Chalcolithic period,[61] these techniques did not spread widely until later,

when it spread throughout the region and beyond.[59] The origins of silver production in India, China, and Japan were almost certainly equally ancient, but are not well-documented due to their great age.[60]

Silver mining and processing in Kutná Hora, Bohemia, 1490s

When the Phoenicians first came to what is now Spain, they obtained so much silver that they could not fit it all on their ships, and as a result used silver to weight their anchors instead of lead.[59] By the time of the Greek and Roman civilizations, silver coins were a staple of the economy:[57] the Greeks were already extracting silver from galena by the 7th century BC,[59] and the rise of Athens was partly made possible by the nearby silver mines at Laurium, from which they extracted about 30 tonnes a year from 600 to 300 BC.[62] The stability of the Roman currency relied to a high degree on the supply of silver bullion, mostly from Spain, which Roman miners produced on a scale unparalleled before the discovery of the New World. Reaching a peak production of 200 tonnes per year, an estimated silver stock of 10,000 tonnes circulated in the Roman economy in the middle of the second century AD, five to ten times larger than the combined amount of silver available to medieval Europe and the Abbasid Caliphate around AD 800.[63][64] The Romans also recorded the extraction of silver in central and northern Europe in the same time period. This production came to a nearly complete halt with the fall of the Roman Empire, not to resume until the time of Charlemagne: by then, tens of thousands of tonnes of silver had already been extracted.[60]

Central Europe became the centre of silver production during the Middle Ages, as the Mediterranean deposits exploited by the ancient civilisations had been exhausted. Silver mines were opened in Bohemia, Saxony, Erzgebirge, Alsace, the Lahn region, Siegerland, Silesia, Hungary, Norway, Steiermark, Schwaz, and the southern Black Forest. Most of these ores were quite rich in silver and could simply be separated by hand from the remaining rock and then smelted; some deposits of native silver were also encountered. Many of these mines were soon exhausted, but a few of them remained active until the Industrial Revolution, before which the world production of silver was around a meagre 50 tonnes per year.[60] In the Americas, high temperature silver-lead cupellation technology was developed by pre-Inca civilizations as early as AD 60–120; silver deposits in India, China, Japan, and pre-Columbian America continued to be mined during this time.[60][65]

With the discovery of America and the plundering of silver by the Spanish conquistadors, Central and South America became the dominant producers of silver until around the beginning of the 18th century, particularly Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina:[60] the last of these countries later took its name from that of the metal that composed so much of its mineral wealth.[62] The silver trade gave way to a global network of exchange. As one historian put it, silver «went round the world and made the world go round.»[66] Much of this silver ended up in the hands of the Chinese. A Portuguese merchant in 1621 noted that silver «wanders throughout all the world… before flocking to China, where it remains as if at its natural center.»[67] Still, much of it went to Spain, allowing Spanish rulers to pursue military and political ambitions in both Europe and the Americas. «New World mines,» concluded several historians, «supported the Spanish empire.»[68]

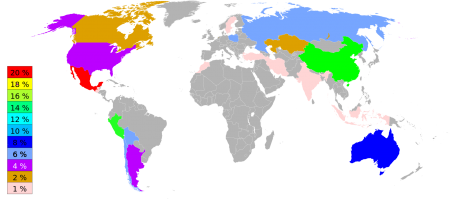

In the 19th century, primary production of silver moved to North America, particularly Canada, Mexico, and Nevada in the United States: some secondary production from lead and zinc ores also took place in Europe, and deposits in Siberia and the Russian Far East as well as in Australia were mined.[60] Poland emerged as an important producer during the 1970s after the discovery of copper deposits that were rich in silver, before the centre of production returned to the Americas the following decade. Today, Peru and Mexico are still among the primary silver producers, but the distribution of silver production around the world is quite balanced and about one-fifth of the silver supply comes from recycling instead of new production.[60]

-

Ancient Greek gilded bowl; 2nd–1st century BC; height: 7.6 cm, dimeter: 14.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Roman plate; 1st–2nd century AD; height: 0.1 cm, diameter: 12.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Roman bust of Serapis; 2nd century; 15.6 x 9.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Rococo tureen; 1749; height: 26.3 cm, width: 39 cm, depth: 24 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Rococo coffeepot; 1757; height: 29.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Neoclassical ewer; 1784–1785; height: 32.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Art Nouveau jardinière; circa 1905–1910; height: 22 cm, width: 47 cm, depth: 22.5 cm; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

-

Symbolic role

16th-century fresco painting of Judas being paid thirty pieces of silver for his betrayal of Jesus

Silver plays a certain role in mythology and has found various usage as a metaphor and in folklore. The Greek poet Hesiod’s Works and Days (lines 109–201) lists different ages of man named after metals like gold, silver, bronze and iron to account for successive ages of humanity.[69] Ovid’s Metamorphoses contains another retelling of the story, containing an illustration of silver’s metaphorical use of signifying the second-best in a series, better than bronze but worse than gold:

But when good Saturn, banish’d from above,

Was driv’n to Hell, the world was under Jove.

Succeeding times a silver age behold,

Excelling brass, but more excell’d by gold.

In folklore, silver was commonly thought to have mystic powers: for example, a bullet cast from silver is often supposed in such folklore the only weapon that is effective against a werewolf, witch, or other monsters.[70][71][72] From this the idiom of a silver bullet developed into figuratively referring to any simple solution with very high effectiveness or almost miraculous results, as in the widely discussed software engineering paper No Silver Bullet.[73] Other powers attributed to silver include detection of poison and facilitation of passage into the mythical realm of fairies.[72]

Silver production has also inspired figurative language. Clear references to cupellation occur throughout the Old Testament of the Bible, such as in Jeremiah’s rebuke to Judah: «The bellows are burned, the lead is consumed of the fire; the founder melteth in vain: for the wicked are not plucked away. Reprobate silver shall men call them, because the Lord hath rejected them.» (Jeremiah 6:19–20) Jeremiah was also aware of sheet silver, exemplifying the malleability and ductility of the metal: «Silver spread into plates is brought from Tarshish, and gold from Uphaz, the work of the workman, and of the hands of the founder: blue and purple is their clothing: they are all the work of cunning men.» (Jeremiah 10:9)[59]

Silver also has more negative cultural meanings: the idiom thirty pieces of silver, referring to a reward for betrayal, references the bribe Judas Iscariot is said in the New Testament to have taken from Jewish leaders in Jerusalem to turn Jesus of Nazareth over to soldiers of the high priest Caiaphas.[74] Ethically, silver also symbolizes greed and degradation of consciousness; this is the negative aspect, the perverting of its value.[75]

Occurrence and production

The abundance of silver in the Earth’s crust is 0.08 parts per million, almost exactly the same as that of mercury. It mostly occurs in sulfide ores, especially acanthite and argentite, Ag2S. Argentite deposits sometimes also contain native silver when they occur in reducing environments, and when in contact with salt water they are converted to chlorargyrite (including horn silver), AgCl, which is prevalent in Chile and New South Wales.[76] Most other silver minerals are silver pnictides or chalcogenides; they are generally lustrous semiconductors. Most true silver deposits, as opposed to argentiferous deposits of other metals, came from Tertiary period vulcanism.[77]

The principal sources of silver are the ores of copper, copper-nickel, lead, and lead-zinc obtained from Peru, Bolivia, Mexico, China, Australia, Chile, Poland and Serbia.[9] Peru, Bolivia and Mexico have been mining silver since 1546, and are still major world producers. Top silver-producing mines are Cannington (Australia), Fresnillo (Mexico), San Cristóbal (Bolivia), Antamina (Peru), Rudna (Poland), and Penasquito (Mexico).[78] Top near-term mine development projects through 2015 are Pascua Lama (Chile), Navidad (Argentina), Jaunicipio (Mexico), Malku Khota (Bolivia),[79] and Hackett River (Canada).[78] In Central Asia, Tajikistan is known to have some of the largest silver deposits in the world.[80]

Silver is usually found in nature combined with other metals, or in minerals that contain silver compounds, generally in the form of sulfides such as galena (lead sulfide) or cerussite (lead carbonate). So the primary production of silver requires the smelting and then cupellation of argentiferous lead ores, a historically important process.[81] Lead melts at 327 °C, lead oxide at 888 °C and silver melts at 960 °C. To separate the silver, the alloy is melted again at the high temperature of 960 °C to 1000 °C in an oxidizing environment. The lead oxidises to lead monoxide, then known as litharge, which captures the oxygen from the other metals present. The liquid lead oxide is removed or absorbed by capillary action into the hearth linings.[82][83][84]

- Ag(s) + 2Pb(s) + O

2(g) → 2PbO(absorbed) + Ag(l)

Today, silver metal is primarily produced instead as a secondary byproduct of electrolytic refining of copper, lead, and zinc, and by application of the Parkes process on lead bullion from ore that also contains silver.[85] In such processes, silver follows the non-ferrous metal in question through its concentration and smelting, and is later purified out. For example, in copper production, purified copper is electrolytically deposited on the cathode, while the less reactive precious metals such as silver and gold collect under the anode as the so-called «anode slime». This is then separated and purified of base metals by treatment with hot aerated dilute sulfuric acid and heating with lime or silica flux, before the silver is purified to over 99.9% purity via electrolysis in nitrate solution.[76]

Commercial-grade fine silver is at least 99.9% pure, and purities greater than 99.999% are available. In 2014, Mexico was the top producer of silver (5,000 tonnes or 18.7% of the world’s total of 26,800 t), followed by China (4,060 t) and Peru (3,780 t).[85]

In marine environments

Silver concentration is low in seawater (pmol/L). Levels vary by depth and between water bodies. Dissolved silver concentrations range from 0.3 pmol/L in coastal surface waters to 22.8 pmol/L in pelagic deep waters.[86] Analyzing the presence and dynamics of silver in marine environments is difficult due to these particularly low concentrations and complex interactions in the environment.[87] Although a rare trace metal, concentrations are greatly impacted by fluvial, aeolian, atmospheric, and upwelling inputs, as well as anthropogenic inputs via discharge, waste disposal, and emissions from industrial companies.[88][89] Other internal processes such as decomposition of organic matter may be a source of dissolved silver in deeper waters, which feeds into some surface waters through upwelling and vertical mixing.[89]

In the Atlantic and Pacific, silver concentrations are minimal at the surface but rise in deeper waters.[90] Silver is taken up by plankton in the photic zone, remobilized with depth, and enriched in deep waters. Silver is transported from the Atlantic to the other oceanic water masses.[88] In North Pacific waters, silver is remobilized at a slower rate and increasingly enriched compared to deep Atlantic waters. Silver has increasing concentrations that follow the major oceanic conveyor belt that cycles water and nutrients from the North Atlantic to the South Atlantic to the North Pacific.[91]

There is not an extensive amount of data focused on how marine life is affected by silver despite the likely deleterious effects it could have on organisms through bioaccumulation, association with particulate matters, and sorption.[86] Not until about 1984 did scientists begin to understand the chemical characteristics of silver and the potential toxicity. In fact, mercury is the only other trace metal that surpasses the toxic effects of silver; however, the full extent of silver toxicity is not expected in oceanic conditions because of its ability to transfer into nonreactive biological compounds.[92]

In one study, the presence of excess ionic silver and silver nanoparticles caused bioaccumulation effects on zebrafish organs and altered the chemical pathways within their gills.[93] In addition, very early experimental studies demonstrated how the toxic effects of silver fluctuate with salinity and other parameters, as well as between life stages and different species such as finfish, molluscs, and crustaceans.[94] Another study found raised concentrations of silver in the muscles and liver of dolphins and whales, indicating pollution of this metal within recent decades. Silver is not an easy metal for an organism to eliminate and elevated concentrations can cause death.[95]

Monetary use

The earliest known coins were minted in the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor around 600 BC.[96] The coins of Lydia were made of electrum, which is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, that was available within the territory of Lydia.[96] Since that time, silver standards, in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed weight of silver, have been widespread throughout the world until the 20th century. Notable silver coins through the centuries include the Greek drachma,[97] the Roman denarius,[98] the Islamic dirham,[99] the karshapana from ancient India and rupee from the time of the Mughal Empire (grouped with copper and gold coins to create a trimetallic standard),[100] and the Spanish dollar.[101][102]

The ratio between the amount of silver used for coinage and that used for other purposes has fluctuated greatly over time; for example, in wartime, more silver tends to have been used for coinage to finance the war.[103]

Today, silver bullion has the ISO 4217 currency code XAG, one of only four precious metals to have one (the others being palladium, platinum, and gold).[104] Silver coins are produced from cast rods or ingots, rolled to the correct thickness, heat-treated, and then used to cut blanks from. These blanks are then milled and minted in a coining press; modern coining presses can produce 8000 silver coins per hour.[103]

Price

Price of silver 1968-2022

Silver prices are normally quoted in troy ounces. One troy ounce is equal to 31.1034768 grams. The London silver fix is published every working day at noon London time.[105] This price is determined by several major international banks and is used by London bullion market members for trading that day. Prices are most commonly shown as the United States dollar (USD), the Pound sterling (GBP), and the Euro (EUR).

Applications

Jewellery and silverware

The major use of silver besides coinage throughout most of history was in the manufacture of jewellery and other general-use items, and this continues to be a major use today. Examples include table silver for cutlery, for which silver is highly suited due to its antibacterial properties. Western concert flutes are usually plated with or made out of sterling silver;[107] in fact, most silverware is only silver-plated rather than made out of pure silver; the silver is normally put in place by electroplating. Silver-plated glass (as opposed to metal) is used for mirrors, vacuum flasks, and Christmas tree decorations.[108]

Because pure silver is very soft, most silver used for these purposes is alloyed with copper, with finenesses of 925/1000, 835/1000, and 800/1000 being common. One drawback is the easy tarnishing of silver in the presence of hydrogen sulfide and its derivatives. Including precious metals such as palladium, platinum, and gold gives resistance to tarnishing but is quite costly; base metals like zinc, cadmium, silicon, and germanium do not totally prevent corrosion and tend to affect the lustre and colour of the alloy. Electrolytically refined pure silver plating is effective at increasing resistance to tarnishing. The usual solutions for restoring the lustre of tarnished silver are dipping baths that reduce the silver sulfide surface to metallic silver, and cleaning off the layer of tarnish with a paste; the latter approach also has the welcome side effect of polishing the silver concurrently.[107]

Medicine

In medicine, silver is incorporated into wound dressings and used as an antibiotic coating in medical devices. Wound dressings containing silver sulfadiazine or silver nanomaterials are used to treat external infections. Silver is also used in some medical applications, such as urinary catheters (where tentative evidence indicates it reduces catheter-related urinary tract infections) and in endotracheal breathing tubes (where evidence suggests it reduces ventilator-associated pneumonia).[109][110] The silver ion is bioactive and in sufficient concentration readily kills bacteria in vitro. Silver ions interfere with enzymes in the bacteria that transport nutrients, form structures, and synthesise cell walls; these ions also bond with the bacteria’s genetic material. Silver and silver nanoparticles are used as an antimicrobial in a variety of industrial, healthcare, and domestic application: for example, infusing clothing with nanosilver particles thus allows them to stay odourless for longer.[111][112] Bacteria can, however, develop resistance to the antimicrobial action of silver.[113] Silver compounds are taken up by the body like mercury compounds, but lack the toxicity of the latter. Silver and its alloys are used in cranial surgery to replace bone, and silver–tin–mercury amalgams are used in dentistry.[108] Silver diammine fluoride, the fluoride salt of a coordination complex with the formula [Ag(NH3)2]F, is a topical medicament (drug) used to treat and prevent dental caries (cavities) and relieve dentinal hypersensitivity.[114]

Electronics

Silver is very important in electronics for conductors and electrodes on account of its high electrical conductivity even when tarnished. Bulk silver and silver foils were used to make vacuum tubes, and continue to be used today in the manufacture of semiconductor devices, circuits, and their components. For example, silver is used in high quality connectors for RF, VHF, and higher frequencies, particularly in tuned circuits such as cavity filters where conductors cannot be scaled by more than 6%. Printed circuits and RFID antennas are made with silver paints,[9][115] Powdered silver and its alloys are used in paste preparations for conductor layers and electrodes, ceramic capacitors, and other ceramic components.[116]

Brazing alloys

Silver-containing brazing alloys are used for brazing metallic materials, mostly cobalt, nickel, and copper-based alloys, tool steels, and precious metals. The basic components are silver and copper, with other elements selected according to the specific application desired: examples include zinc, tin, cadmium, palladium, manganese, and phosphorus. Silver provides increased workability and corrosion resistance during usage.[117]

Chemical equipment

Silver is useful in the manufacture of chemical equipment on account of its low chemical reactivity, high thermal conductivity, and being easily workable. Silver crucibles (alloyed with 0.15% nickel to avoid recrystallisation of the metal at red heat) are used for carrying out alkaline fusion. Copper and silver are also used when doing chemistry with fluorine. Equipment made to work at high temperatures is often silver-plated. Silver and its alloys with gold are used as wire or ring seals for oxygen compressors and vacuum equipment.[118]

Catalysis

Silver metal is a good catalyst for oxidation reactions; in fact it is somewhat too good for most purposes, as finely divided silver tends to result in complete oxidation of organic substances to carbon dioxide and water, and hence coarser-grained silver tends to be used instead. For instance, 15% silver supported on α-Al2O3 or silicates is a catalyst for the oxidation of ethylene to ethylene oxide at 230–270 °C. Dehydrogenation of methanol to formaldehyde is conducted at 600–720 °C over silver gauze or crystals as the catalyst, as is dehydrogenation of isopropanol to acetone. In the gas phase, glycol yields glyoxal and ethanol yields acetaldehyde, while organic amines are dehydrated to nitriles.[118]

Photography

The photosensitivity of the silver halides allowed for their use in traditional photography, although digital photography, which does not use silver, is now dominant. The photosensitive emulsion used in black-and-white photography is a suspension of silver halide crystals in gelatin, possibly mixed in with some noble metal compounds for improved photosensitivity, developing, and tuning[clarify]. Colour photography requires the addition of special dye components and sensitisers, so that the initial black-and-white silver image couples with a different dye component. The original silver images are bleached off and the silver is then recovered and recycled. Silver nitrate is the starting material in all cases.[119]

The use of silver nitrate and silver halides in photography has rapidly declined with the advent of digital technology. From the peak global demand for photographic silver in 1999 (267,000,000 troy ounces or 8,304.6 tonnes) the market contracted almost 70% by 2013.[120]

Nanoparticles

Nanosilver particles, between 10 and 100 nanometres in size, are used in many applications. They are used in conductive inks for printed electronics, and have a much lower melting point than larger silver particles of micrometre size. They are also used medicinally in antibacterials and antifungals in much the same way as larger silver particles.[112] In addition, according to the European Union Observatory for Nanomaterials (EUON), silver nanoparticles are used both in pigments, as well as cosmetics.[121][122]

Miscellanea

Pure silver metal is used as a food colouring. It has the E174 designation and is approved in the European Union.[123] Traditional Indian and Pakistani dishes sometimes include decorative silver foil known as vark,[124] and in various other cultures, silver dragée are used to decorate cakes, cookies, and other dessert items.[125]

Photochromic lenses include silver halides, so that ultraviolet light in natural daylight liberates metallic silver, darkening the lenses. The silver halides are reformed in lower light intensities. Colourless silver chloride films are used in radiation detectors. Zeolite sieves incorporating Ag+ ions are used to desalinate seawater during rescues, using silver ions to precipitate chloride as silver chloride. Silver is also used for its antibacterial properties for water sanitisation, but the application of this is limited by limits on silver consumption. Colloidal silver is similarly used to disinfect closed swimming pools; while it has the advantage of not giving off a smell like hypochlorite treatments do, colloidal silver is not effective enough for more contaminated open swimming pools. Small silver iodide crystals are used in cloud seeding to cause rain.[112]

The Texas Legislature designated silver the official precious metal of Texas in 2007.[126]

Precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Warning |

|

Hazard statements |

H410 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P273, P391, P501[127] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

0 0 0 |

Silver compounds have low toxicity compared to those of most other heavy metals, as they are poorly absorbed by the human body when ingested, and that which does get absorbed is rapidly converted to insoluble silver compounds or complexed by metallothionein. However, silver fluoride and silver nitrate are caustic and can cause tissue damage, resulting in gastroenteritis, diarrhoea, falling blood pressure, cramps, paralysis, and respiratory arrest. Animals repeatedly dosed with silver salts have been observed to experience anaemia, slowed growth, necrosis of the liver, and fatty degeneration of the liver and kidneys; rats implanted with silver foil or injected with colloidal silver have been observed to develop localised tumours. Parenterally admistered colloidal silver causes acute silver poisoning.[128] Some waterborne species are particularly sensitive to silver salts and those of the other precious metals; in most situations, however, silver does not pose serious environmental hazards.[128]

In large doses, silver and compounds containing it can be absorbed into the circulatory system and become deposited in various body tissues, leading to argyria, which results in a blue-grayish pigmentation of the skin, eyes, and mucous membranes. Argyria is rare, and so far as is known, does not otherwise harm a person’s health, though it is disfiguring and usually permanent. Mild forms of argyria are sometimes mistaken for cyanosis, a blue tint on skin, caused by lack of oxygen.[128][9]

Metallic silver, like copper, is an antibacterial agent, which was known to the ancients and first scientifically investigated and named the oligodynamic effect by Carl Nägeli. Silver ions damage the metabolism of bacteria even at such low concentrations as 0.01–0.1 milligrams per litre; metallic silver has a similar effect due to the formation of silver oxide. This effect is lost in the presence of sulfur due to the extreme insolubility of silver sulfide.[128]

Some silver compounds are very explosive, such as the nitrogen compounds silver azide, silver amide, and silver fulminate, as well as silver acetylide, silver oxalate, and silver(II) oxide. They can explode on heating, force, drying, illumination, or sometimes spontaneously. To avoid the formation of such compounds, ammonia and acetylene should be kept away from silver equipment. Salts of silver with strongly oxidising acids such as silver chlorate and silver nitrate can explode on contact with materials that can be readily oxidised, such as organic compounds, sulfur and soot.[128]

See also

- Silver coin

- Silver medal

- Free silver

- List of countries by silver production

- List of silver compounds

- Silver as an investment

- Silverpoint drawing

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Silver». CIAAW. 1985.

- ^ Ag(0) has been observed in carbonyl complexes in low-temperature matrices: see McIntosh, D.; Ozin, G. A. (1976). «Synthesis using metal vapors. Silver carbonyls. Matrix infrared, ultraviolet-visible, and electron spin resonance spectra, structures, and bonding of silver tricarbonyl, silver dicarbonyl, silver monocarbonyl, and disilver hexacarbonyl». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 (11): 3167–75. doi:10.1021/ja00427a018.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Poole, Charles P. Jr. (11 March 2004). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Condensed Matter Physics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-054523-3.

- ^ «Bullion vs. Numismatic Coins: Difference between Bullion and Numismatic Coins». providentmetals.com. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ «‘World has 5 times more gold than silver’ | Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis». dna. 3 March 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Masuda, Hideki (2016). «Combined Transmission Electron Microscopy – In situ Observation of the Formation Process and Measurement of Physical Properties for Single Atomic-Sized Metallic Wires». In Janecek, Milos; Kral, Robert (eds.). Modern Electron Microscopy in Physical and Life Sciences. InTech. doi:10.5772/62288. ISBN 978-953-51-2252-4. S2CID 58893669.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hammond, C. R. (2004). The Elements, in Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1177

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1178

- ^ George L. Trigg; Edmund H. Immergut (1992). Encyclopedia of applied physics. Vol. 4: Combustion to Diamagnetism. VCH Publishers. pp. 267–72. ISBN 978-3-527-28126-8. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Alex Austin (2007). The Craft of Silversmithing: Techniques, Projects, Inspiration. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-60059-131-0.

- ^ Edwards, H.W.; Petersen, R.P. (1936). «Reflectivity of evaporated silver films». Physical Review. 50 (9): 871. Bibcode:1936PhRv…50..871E. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.50.871.

- ^ «Silver vs. Aluminum». Gemini Observatory. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Russell AM & Lee KL 2005, Structure-property relations in nonferrous metals Archived 14 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Wiley-Interscience, New York, ISBN 0-471-64952-X. p. 302.

- ^ Nichols, Kenneth D. (1987). The Road to Trinity. Morrow, NY: Morrow. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-688-06910-0.

- ^ Young, Howard (11 September 2002). «Eastman at Oak Ridge During World War II». Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

- ^ Oman, H. (1992). «Not invented here? Check your history». Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine. 7 (1): 51–53. doi:10.1109/62.127132. S2CID 22674885.

- ^ a b c d «Atomic Weights of the Elements 2007 (IUPAC)». Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ «Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for All Elements (NIST)». Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Cameron, A.G.W. (1973). «Abundance of the Elements in the Solar System» (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 15 (1): 121–46. Bibcode:1973SSRv…15..121C. doi:10.1007/BF00172440. S2CID 120201972.

- ^ a b Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ «Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Silver (NIST)». Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ Kelly, William R.; Wasserburg, G. J. (1978). «Evidence for the existence of 107Pd in the early solar system» (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 5 (12): 1079–82. Bibcode:1978GeoRL…5.1079K. doi:10.1029/GL005i012p01079.

- ^ Russell, Sara S.; Gounelle, Matthieu; Hutchison, Robert (2001). «Origin of Short-Lived Radionuclides». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 359 (1787): 1991–2004. Bibcode:2001RSPTA.359.1991R. doi:10.1098/rsta.2001.0893. JSTOR 3066270. S2CID 120355895.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1179

- ^ a b c d e Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1180

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1176

- ^ Lidin RA 1996, Inorganic substances handbook, Begell House, New York, ISBN 1-56700-065-7. p. 5

- ^ Goodwin F, Guruswamy S, Kainer KU, Kammer C, Knabl W, Koethe A, Leichtfreid G, Schlamp G, Stickler R & Warlimont H 2005, ‘Noble metals and noble metal alloys’, in Springer Handbook of Condensed Matter and Materials Data, W Martienssen & H Warlimont (eds), Springer, Berlin, pp. 329–406, ISBN 3-540-44376-2. p. 341

- ^ «Silver Artifacts» in Corrosion – Artifacts. NACE Resource Center

- ^ Bjelkhagen, Hans I. (1995). Silver-halide recording materials: for holography and their processing. Springer. pp. 156–66. ISBN 978-3-540-58619-7.

- ^ Riedel, Sebastian; Kaupp, Martin (2009). «The highest oxidation states of the transition metal elements». Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 253 (5–6): 606–24. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.014.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1188

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 903

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1181–82

- ^ a b c d e Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1183–85

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1185–87

- ^ Abbri, Ferdinando (30 August 2019). «Gold and silver: perfection of metals in medieval and early modern alchemy». Substantia: 39–44. doi:10.13128/Substantia-603. ISSN 2532-3997. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ «Definition of Lunar Caustic». dictionary.die.net. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Cope, A. C.; Bach, R. D. (1973). «trans-Cyclooctene». Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 5, p. 315 - ^ a b McCloskey C.M.; Coleman, G.H. (1955). «β-d-Glucose-2,3,4,6-Tetraacetate». Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 3, p. 434 - ^ Andreas Brumby et al. «Silver, Silver Compounds, and Silver Alloys» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008. doi:10.1002/14356007.a24_107.pub2

- ^ Meyer, Rudolf; Köhler, Josef & Homburg, Axel (2007). Explosives. Wiley–VCH. p. 284. ISBN 978-3-527-31656-4.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 1189

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1195–96

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1199–200

- ^ Miller, W.T.; Burnard, R.J. (1968). «Perfluoroalkylsilver compounds». J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90 (26): 7367–68. doi:10.1021/ja01028a047.

- ^ Holliday, A.; Pendlebury, R.E. (1967). «Vinyllead compounds I. Cleavage of vinyl groups from tetravinyllead». J. Organomet. Chem. 7 (2): 281–84. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91078-7.

- ^ Wang, Harrison M.J.; Lin, Ivan J.B. (1998). «Facile Synthesis of Silver(I)−Carbene Complexes. Useful Carbene Transfer Agents». Organometallics. 17 (5): 972–75. doi:10.1021/om9709704.

- ^ a b Ullmann, pp. 54–61

- ^ Kroonen, Guus (2013). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Brill. p. 436. ISBN 978-90-04-18340-7.

- ^ a b Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-19-928791-8.

- ^ Boutkan, Dirk; Kossmann, Maarten (2001). «On the Etymology of «Silver»«. NOWELE: North-Western European Language Evolution. 38 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1075/nowele.38.01bou. ISSN 0108-8416.

- ^ Weeks, p. 4

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1173–74

- ^ Readon, Arthur C. (2011). Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist. ASM International. pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-1-61503-821-3.

- ^ a b c d e Weeks, pp. 14–19

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ullmann, pp. 16–19

- ^ Maria Grazia Melis. «Silver in Neolithic and Eneolithic Sardinia, in H. Meller/R. Risch/E. Pernicka (eds.), Metalle der Macht – Frühes Gold und Silber. 6. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 17. bis 19. Oktober 2013 in Halle (Saale), Tagungen des Landesmuseums für».

- ^ a b Emsley, John (2011). Nature’s building blocks: an A-Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 492–98. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ Patterson, C.C. (1972). «Silver Stocks and Losses in Ancient and Medieval Times». The Economic History Review. 25 (2): 205235 (216, table 2, 228, table 6). doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1972.tb02173.x.

- ^ de Callataÿ, François (2005). «The Greco-Roman Economy in the Super Long-Run: Lead, Copper, and Shipwrecks». Journal of Roman Archaeology. 18: 361–72 [365ff]. doi:10.1017/s104775940000742x. S2CID 232346123.

- ^ Carol A. Schultze; Charles Stanish; David A. Scott; Thilo Rehren; Scott Kuehner; James K. Feathers (2009). «Direct evidence of 1,900 years of indigenous silver production in the Lake Titicaca Basin of Southern Peru». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (41): 17280–83. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10617280S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907733106. PMC 2754926. PMID 19805127.

- ^ Frank, Andre Gunder (1998). ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 131.

- ^ von Glahn, Richard (1996). «Myth and Reality of China’s Seventeenth Century Monetary Crisis». Journal of Economic History. 2: 132.

- ^ Flynn, Dennis O.; Giraldez, Arturo (1995). «Born with a «Silver Spoon»«. Journal of World History. 2: 210.

- ^ Joseph Eddy Fontenrose: Work, Justice, and Hesiod’s Five Ages. In: Classical Philology. V. 69, Nr. 1, 1974, p. 1–16.

- ^ Jackson, Robert (1995). Witchcraft and the Occult. Devizes, Quintet Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-85348-888-7.

- ^ Стойкова, Стефана. «Дельо хайдутин». Българска народна поезия и проза в седем тома (in Bulgarian). Vol. Т. III. Хайдушки и исторически песни. Варна: ЕИ «LiterNet». ISBN 978-954-304-232-6.

- ^ a b St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 49. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ Brooks, Frederick. P. Jr. (1987). «No Silver Bullet – Essence and Accident in Software Engineering» (PDF). Computer. 20 (4): 10–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.117.315. doi:10.1109/MC.1987.1663532. S2CID 372277.

- ^ Matthew 26:15

- ^ Chevalier, Jean; Gheerbrant, Alain (2009). Dicționar de Simboluri. Mituri, Vise, Obiceiuri, Gesturi, Forme, Figuri, Culori, Numere [Dictionary of Symbols. Myths, Dreams, Habits, Gestures, Shapes, Figures, Colors, Numbers] (in Romanian). Polirom. 105. ISBN 978-973-46-1286-4.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1174–67

- ^ Ullmann, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b CPM Group (2011). CPM Silver Yearbook. New York: Euromoney Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-9826741-4-7.

- ^ «Preliminary Economic Assessment Technical Report 43-101» (PDF). South American Silver Corp. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

- ^ «Why Are Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan So Split on Foreign Mining?». EurasiaNet.org. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Kassianidou, V. 2003. Early Extraction of Silver from Complex Polymetallic Ores, in Craddock, P.T. and Lang, J (eds) Mining and Metal production through the Ages. London, British Museum Press: 198–206

- ^ Craddock, P.T. (1995). Early metal mining and production. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 223

- ^

Bayley, J., Crossley, D. and Ponting, M. (eds). 2008. «Metals and Metalworking. A research framework for archaeometallurgy». Historical Metallurgy Society 6. - ^ Pernicka, E., Rehren, Th., Schmitt-Strecker, S. 1998. Late Uruk silver production by cupellation at Habuba Kabira, Syria in Metallurgica Antiqua : in honour of Hans-Gert Bachmann and Robert Maddin by Bachmann, H.G, Maddin, Robert, Rehren, Thilo, Hauptmann, Andreas, Muhly, James David, Deutsches Bergbau-Museum: 123–34.

- ^ a b Hilliard, Henry E. «Silver». USGS.

- ^ a b Barriada, Jose L.; Tappin, Alan D.; Evans, E. Hywel; Achterberg, Eric P. (2007). «Dissolved silver measurements in seawater». TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 26 (8): 809–817. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2007.06.004. ISSN 0165-9936.

- ^ Fischer, Lisa; Smith, Geoffrey; Hann, Stephan; Bruland, Kenneth W. (2018). «Ultra-trace analysis of silver and platinum in seawater by ICP-SFMS after off-line matrix separation and pre-concentration». Marine Chemistry. 199: 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.marchem.2018.01.006. ISSN 0304-4203.

- ^ a b Ndung’u, K.; Thomas, M.A.; Flegal, A.R. (2001). «Silver in the western equatorial and South Atlantic Ocean». Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 48 (13): 2933–2945. Bibcode:2001DSRII..48.2933N. doi:10.1016/S0967-0645(01)00025-X. ISSN 0967-0645.

- ^ a b Zhang, Yan; Amakawa, Hiroshi; Nozaki, Yoshiyuki (2001). «Oceanic profiles of dissolved silver: precise measurements in the basins of western North Pacific, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Japan Sea». Marine Chemistry. 75 (1–2): 151–163. doi:10.1016/S0304-4203(01)00035-4. ISSN 0304-4203.

- ^ Flegal, A.R.; Sañudo-Wilhelmy, S.A.; Scelfo, G.M. (1995). «Silver in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean». Marine Chemistry. 49 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1016/0304-4203(95)00021-I. ISSN 0304-4203.

- ^ Ranville, Mara A.; Flegal, A. Russell (2005). «Silver in the North Pacific Ocean». Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 6 (3): n/a. Bibcode:2005GGG…..6.3M01R. doi:10.1029/2004GC000770. ISSN 1525-2027.

- ^ Ratte, Hans Toni (1999). «Bioaccumulation and toxicity of silver compounds: A review». Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 18 (1): 89–108. doi:10.1002/etc.5620180112. ISSN 0730-7268. S2CID 129765758.

- ^ Lacave, José María; Vicario-Parés, Unai; Bilbao, Eider; Gilliland, Douglas; Mura, Francesco; Dini, Luciana; Cajaraville, Miren P.; Orbea, Amaia (2018). «Waterborne exposure of adult zebrafish to silver nanoparticles and to ionic silver results in differential silver accumulation and effects at cellular and molecular levels». Science of the Total Environment. 642: 1209–1220. Bibcode:2018ScTEn.642.1209L. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.128. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 30045502. S2CID 51719111.

- ^ Calabrese, A., Thurberg, F.P., Gould, E. (1977). Effects of Cadmium, Mercury, and Silver on Marine Animals. Marine Fisheries Review, 39(4):5-11.

https://fliphtml5.com/hzci/lbsc/basic Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Chen, Meng-Hsien; Zhuang, Ming-Feng; Chou, Lien-Siang; Liu, Jean-Yi; Shih, Chieh-Chih; Chen, Chiee-Young (2017). «Tissue concentrations of four Taiwanese toothed cetaceans indicating the silver and cadmium pollution in the western Pacific Ocean». Marine Pollution Bulletin. 124 (2): 993–1000. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.03.028. ISSN 0025-326X. PMID 28442199.

- ^ a b «The origins of coinage». britishmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ «Tetradrachm». Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ Crawford, Michael H. (1974). Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, 2 Volumes. ISBN 0-521-07492-4

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st edition, s.v. ‘dirhem’ Archived 9 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ etymonline.com (20 September 2008). «Etymology of rupee». Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Ray Woodcock (1 May 2009). Globalization from Genesis to Geneva: A Confluence of Humanity. Trafford Publishing. pp. 104–05. ISBN 978-1-4251-8853-5. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ Thomas J. Osborne (2012). Pacific Eldorado: A History of Greater California. John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-118-29217-4. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b Ullmann, pp. 63–65

- ^ «Current currency & funds code list – ISO Currency». SNV. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ «LBMA Silver Price». LBMA. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Marcin Latka. «Silver sarcophagus of Saint Stanislaus». artinpl. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b Ullmann, pp. 65–67

- ^ a b Ullmann, pp. 67–71

- ^ Beattie, M.; Taylor, J. (2011). «Silver alloy vs. Uncoated urinary catheters: A systematic review of the literature». Journal of Clinical Nursing. 20 (15–16): 2098–108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03561.x. PMID 21418360.

- ^ Bouadma, L.; Wolff, M.; Lucet, J.C. (August 2012). «Ventilator-associated pneumonia and its prevention». Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 25 (4): 395–404. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328355a835. PMID 22744316. S2CID 41051853.

- ^ Maillard, Jean-Yves; Hartemann, Philippe (2012). «Silver as an antimicrobial: Facts and gaps in knowledge». Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 39 (4): 373–83. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2012.713323. PMID 22928774. S2CID 27527124.

- ^ a b c Ullmann, pp. 83–84

- ^