Артур Рэкхем (англ: Arthur Rackham; 19 сентября 1867 года, Лондон — 6 сентября 1939 года, Суррей). Известный английский иллюстратор, оформивший лучшие образцы детской литературы, а также произведения «Сон в летнюю ночь» Шекспира и «Песнь о Нибелунгах».

Особенности творчества художника Артура Рэкхема: Творчество Рэкхема сложно спутать с чем-либо другим. Помимо узнаваемых сюжетов, его рисунки невероятно графичны и детализированы. Художник заимствовал традиции немецкой и японской гравюр, выработав свой собственный стиль, обладающий аристократизмом и изяществом. Работы талантливого автора во все времена привлекали не только поклонников литературы, взрослых и детей, но также и художников. Его творчество вдохновляло Уолта Диснея, Гильермо дель Торо («Лабиринт Фавна») и Тима Бертона («Сонная лощина»), который даже купил дом иллюстратора.

Известные картины художника Артура Рэкхэма: «Алиса в стране чудес», «Кольцо нибелунгов», «Безумное чаепитие», «Ундина», «Гулливер в стране лилипутов».

От газет к книжной иллюстрации: ранее творчество Артура Рэкхема

Артур Рэкхем родился в Лондонском районе Луишем. Он был одним из 12 детей Альфреда Рэкхема и его жены Энни, которые смогли дать своим детям хорошее образование. Рисунок с самого детства был успешным «сопровождающим» Рэкхема: будущий мастер выиграл несколько призов за свои работы еще во время школьного обучения. В 17 лет Артур совершил свое первое заокеанское путешествие: сопровождаемый двумя тетушками, он отправился в Австралию поправлять слабое здоровье. Новые впечатления оказались полезным бонусом для его художественной натуры.

В 18 лет Артур сам зарабатывал себе на жизнь, будучи клерком Вестминстерской пожарной службы, которая спонсировала его занятия в школе искусств Lambeth.

Вскоре он оставил свое место работы и стал репортером и иллюстратором в британской газете Westminster Budget и других изданиях. Но это занятие было ему не по душе, он называл его «неприятной ручной работой». Искусствоведы считают иллюстрации Рэкхема этого периода весьма посредственными, мало отличающимися от общего потока. Отмечают разве что цветовую гамму, в которой уже тогда читалась будущая воздушность графики Рэкхема.

Первый книжный проект иллюстратора Рэкхема — оформление путеводителя по Лондону «To the Other Side», вышедшего в 1893 году. Следующая книга с его работами «Dolly Dialogues» была опубликованна в 1894 году.

Сборник фантастических сказок «Zankiwank и Bletherwitch» — это первая серьезная работа Артура Рэкхема, где он начинает проявлять свою индивидуальную манеру, демонстрируя легкость пластики и изящество линии, которые будут отличать все его работы в дальнейшем. Именно в применении к сказочным, приключенческим сюжетам автор разовьет свой талант в полную меру.

Артур Рэкхем и золотой век английской иллюстрации

Иллюстрация сказочного сборника стала началом яркого поворота в судьбе и карьере художинка. Но самое важное событие произойдет в 1900 году, когда Рэкхем встетит Эдит Старки — художницу, наставницу и свою будущую супругу, которая родит ему дочь Барбару. Жена стала его «самым вдохновляющим и суровым критиком». Именно Старки поможет Рэкхему уйти от простых колористических решений в рисунках и исследовать более глубокие градации цвета.

Творческий импульс подоспел как никогда вовремя. Технический прогресс в печатном деле позволил иллюстратору легко и быстро распространять свои рисунки, избежав работы в качестве простого гравера. Стало возможным качественно и аккуратно передавать всю ясность штриховых линий и богатство палитры художника. Уровень печатного производства иллюстраций заметно повысился, однако стоимость технологии была высокой, что, впрочем, никак не ухудшило положения художника. Появился совершенно новый формат подарочного издания, которым восхищались, которого ждали, о котором писали письма Санте в канун Рождества.

Первым образцом такого красочного издания была новелла Ирвинга «Рип ван Винкль», вышедшая в 1905 году. Рэкхем создал для нее 51 иллюстрацию и был назван критиками «ведущим декоративным иллюстратором эпохи Эдуарда».

Процесс создания работ был особенный, и в нем просматривается вся суть рэкхемской иллюстрации. Сначала мастер прорисовывал тонкие линии простым карандашом, а сверху покрывал рисунок более плотным слоем чернил. Легкая вуаль акварели в стиле ар-нуво покрывала лист и создавала еще большее ощущение воздушности и фантазийности.

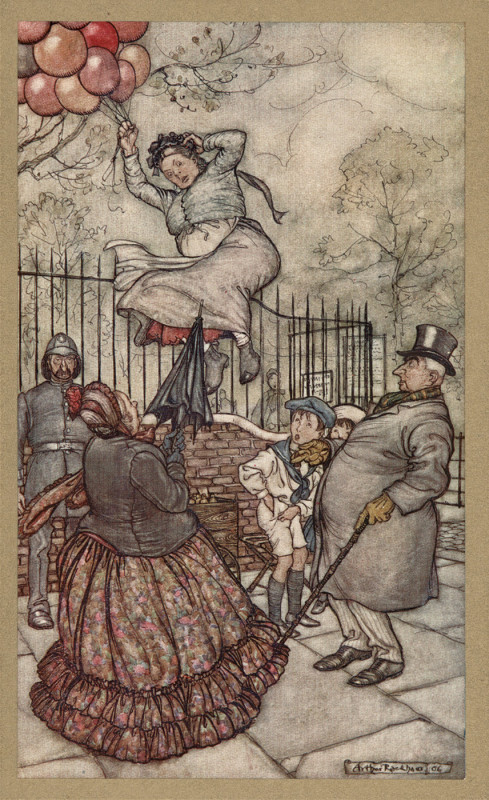

Джеймс Мэтью Барри — автор сказочной истории о Питере Пене, был в восторге от работ Рэкхема и попросил художника проиллюстрировать его самую первую повесть о невзрослеющем мальчике «Питер Пэн в Кенсингтонском саду». И это был невероятный не только творческий, но и коммерческий успех. Издание тут же стала «выдающейся рождественской подарочной книгой 1906 года» и просто самой любимой детской сказкой на все времена.

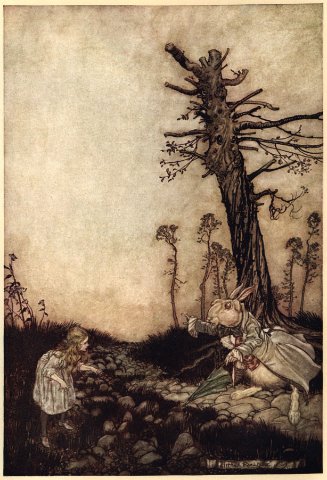

Следующим шагом стала «Алиса в стране чудес». Она вышла в 1907 году и сегодня находится на втором месте по количеству иллюстрированных переизданий культовой сказки. На первом все же стоит издание с классическими иллюстрациями Джона Тенниела.

Изданная в 1908 году The Arthur Rackham Fairy Book («Книга фей Артура Рэкхема») стала одним из наиболее известных его изданий, где «узловатые деревья и толпы фей превратили в реальность мечты тысячи читателей». Вообще, деревья — это отдельные персонажи мира Рэкхема. Эти извивающиеся и антропоморфные существа живут своей жизнью и сопровождают фантастические и пугающие сказки из книги в книгу. «Одушевленные деревья» не дают покоя и современным художникам.

В 1914 г. прошла персональная выставка Артура Рэкхема в Лувре. Это был пик популярности и востребованности Рэкхема, у него было столько заказов, что порой приходилось отказываться от новых задач. Об одном таком заказе он впоследствии искренне жалел. Это был самый первый выпуск сказочной повести Кеннета Грэма «Ветер в ивах», весьма заманчивый проект. И все же иллюстратор от него отказался в пользу другого заказа, не менее важного и значимого: Рэкхем должен был успеть закончить работу над шекспировской комедией «Сон в летнюю ночь».

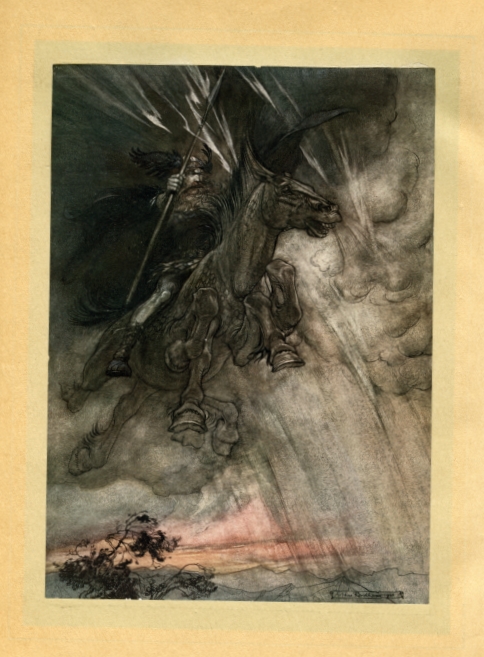

Многие критики сходятся во мнении, что самые яркие и необычные работы иллюстратора можно найти в изданиях сказочной повести о водном духе «Ундина» 1909 года немецкого романтика Фридриха де ла Мотт Фуке, «Рейнголд и Валькирия» Вагнера, сказки братьев Гримм. И без того таинственные и жутковатые истории благодаря рисункам Рэкхема видоизменились: они стали еще более притягательными и сверхъестественными, с отвратительными троллями и пленительными нимфами, будто сошедшими с картин прерафаэлитов, но без пошлого заимствования.

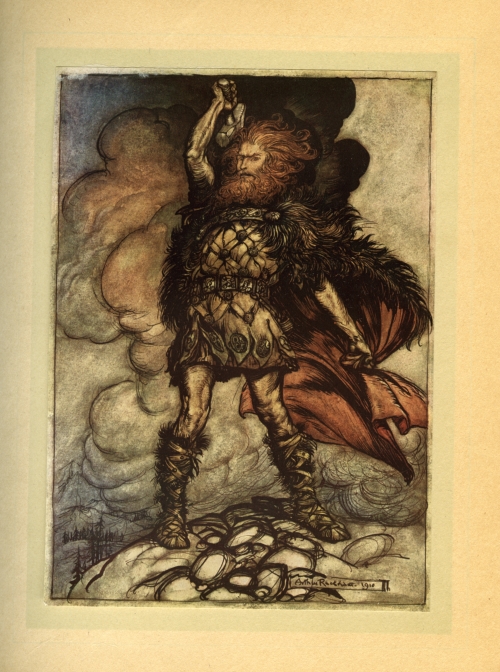

«Его картины представлялись мне ожившей музыкой, повергшей меня в глубины моего восторга. Я мало чего желал в своей жизни, как эту книгу» — напишет автор «Хроник Нарнии» К.С. Льюис о серии иллюстраций к «Кольцу Нибелунгов», созданной в 1910-1911 гг.

Зрелые годы. Вершина карьеры Артура Рэкхема

После Первой мировой войны слава Рэкхема стала распространяться за океаном, откуда хлынули новые заказы. Он оформил произведения Вашингтона Ирвинга, Кристофера Морли и Эдгара По.

Карьера Рэкхема продолжала идти в гору, автор не терял своей индивидуальности в иллюстрации и внимательности в деловых вопросах, продолжая трепетно и ответственно относиться к каждому заказу.

В 1936 году мастера ждал особенный успех. Отказавшись от работы над сказкой Кеннета Грэма в начале века в пользу Шекспира, во второй раз подобную возможность Рэкхем упустить не мог. Но если творческий запал художника не иссякал, то здоровье его шло на спад. Взявшись за долгожданный заказ, ослабевший и измученный, он с трудом его закончил. И все же художник много раз переделывал рисунки, стараясь добиться идеального результата, обращая внимание на мелочи, казавшиеся ничтожными окружающим. Книга «Ветер в ивах», оформленная рисунками Рэкхема, стала шедевром детской иллюстрации, символом чистоты и искренности викторианской сказки.

В 1939 году Артур Рэкхем скончался от рака в своем доме в Лимпсфилде в графстве Суррей.

Не только на бумаге: иллюстрации Рэкхема сегодня

Рэкхем стал одним из популярных и любимых английских иллюстраторов. Но его творчество не осталось лишь символичной вехой в истории искусства, а продолжает жить и развиваться в работах современных авторов. Это касается не просто художников и иллюстраторов, но также режиссеров и мультипликаторов.

Уолт Дисней, восхищавшийся акварелью Рэкхема и изяществом его линии, поручил своему главному иллюстратору Густаву Тренггрену (Gustaf Tenggren) при создании мультфильма «Белоснежка и семь гномов» адаптировать образы английского художника. Однако для анимации образы Рэкхема были слишком витиеваты и многозначны, они могли отвлечь от сюжета и главных персонажей. И Тенггрен создал свой, размеренный и всем знакомый диснеевский стиль рисунка. Однако же мотивы великого иллюстратора можно легко заметить в кадрах ночной сцены в лесу или во фрагменте жуткого перевоплощения королевы-мачехи. Узнаваемы ожившие деревья — любимые персонажи всех поклонников Рэкхема.

Фанаты находят рэкхемовские мотивы даже в «Гарри Поттере» и во «Властелине колец».

Известный американский кинорежиссер Тим Бертон в 2008 году, незадолго до начала работы над «Алисой в Стране чудес» (2010 г.), приобрел за 6 млн фунтов стерлингов готический особняк Артура Рэкхема в Лондоне. Атмосфера в доме была пропитана мистикой и тайнами. В своем интервью режиссер с юмором замечает, что «люди определенно верят, что слышат здесь по ночам странные звуки, и это хорошая атмосфера». Но не только недвижимость связывает этих двух авторов. Образы викторианского иллюстратора проникли в сериал «Сонная лощина» (1999 г.), созданный по произведению Ирвинга, которого, кстати, Рэкхем также иллюстрировал. Да и общий настрой картин Бертона, слегка сумасшедший и потусторонний, очень близок к Рэкхему.

Гильермо дель Торо — режиссер всемирно известного фильма «Лабринт Фавна» (2006 г.) создал свои фантастические образы благодаря сказкам Рэкхема. Невообразимые извивающиеся деревья, суровая первозданная природа и общий колорит будто перекочевали со страниц книг на телеэкран.

Автор: Людмила Лебедева

-

-

July 5 2014, 19:36

- Литература

- Искусство

- История

- Cancel

Артур Рэкхем родился в 1867 году в Лондоне. С 18 лет он работал клерком, одновременно посещая вечернюю школу изящных искусств. В 1888 году работы Рэкхема впервые появились на выставке в Королевской академии художеств. С 1891 года он начал сотрудничать с газетами «Вестминстер газет» и «Пэлл Мэлл Баджет», а в 1894 году получил первый заказ на рисунки для книги — это был путеводитель по Америке. До конца 1890-х годов художник проиллюстрировал еще несколько книг, в том числе «Легенды Инголдсби» Р. Барэма. Но по-настоящему его талант рисовальщика раскрылся лишь в первом десятилетии нового века.

Иллюстрации Рэкхема к вышедшему в 1900 году сборнику сказок братьев Гримм имели большой успех у читателей. Книга переиздавалась несколько раз, причем каждое новое издание выходило в новом оформлении и с новыми рисунками. В 1905 году Рэкхем создал серию рисунков к «Рип Ван Винклю» В. Ирвинга, в 1906 году он по просьбе Джеймса Барри проиллюстрировал его повесть «Питер Пэн в Кенсингтонском саду», а в 1907-м вышли в свет «Легенды Инголдсби» с обновленными рисунками. В том же 1907 году издатель Уильям Хейнеманн заказал художнику иллюстрации к «Алисе в Стране чудес» Л. Кэрролла. Рэкхем создал цикл из 13 цветных и 16 черно-белых рисунков, в которых первым из художников отказался от предложенного Кэрроллом и Тенниелом «викторианского» образа Алисы, предложив новую, современную трактовку, соответствующую мировосприятию эпохи модерна. С выходом в свет «Алисы» пришло признание Рэкхема одним из крупнейших мастеров «золотого века» английской книжной графики. Акварели художника выставлялись в самых престижных лондонских галереях, издательства наперебой предлагали ему оформление малотиражных подарочных изданий, которые сразу раскупались библиофилами. В 1908 году Рэкхем проиллюстрировал «Сон в летнюю ночь» У. Шекспира, а в 1909 году — «Ундину» Ф. де ла Мотт Фуке и новое издание «Волшебных сказок» братьев Гримм. В этих книгах он создал сказочный волшебный мир, населенный эльфами и троллями, драконами и гоблинами. В 1910–1911 годах Рэкхем нарисовал большую серию иллюстраций к «Кольцу Нибелунгов» Р. Вагнера и получил золотую медаль на международной выставке в Барселоне. Наконец, в 1914 году Рэкхем удостоился выставки в парижском Лувре.

После Первой Мировой войны две выставки в Нью-Йорке принесли Рэкхему заказы американских издателей. Неустанно работая, мастер проиллюстрировал «Басни» Эзопа, «Сказки» Ш. Перро, «Бурю» У. Шекспира, «Английские волшебные сказки» Ф. Стил и множество других книг. Большинство из них — сказки для детей: Рэкхем говорил, что «поэтические образы, фантастические и шуточные рисунки и книги для детей играют величайшую стимулирующую и образовательную роль в годы, когда детское воображение наиболее восприимчиво». В 1939 году художник, уже прикованный к постели, завершил свою последнюю работу — иллюстрации к сказке К. Грэхема «Ветер в ивах». Рэкхем умер через несколько недель после того, как создал последнюю иллюстрацию к этой книге.

(В. Г. Зартайский)

Страна волшебства

Богиня Фрейя и золотые яблоки

Великаны-ётуны и Фрейя

Валькирия

Долгий сон Брунгильды

Один (Водан)-путешественник

Норны и нить судьбы

Норны и нить судьбы

Брунгильда целует кольцо

Брунгильда говорит «нет» Гудрун

Брунгильда и Гюнтер

Девы Рейна просят кольцо

Жертва Брунгильды

Король Артур

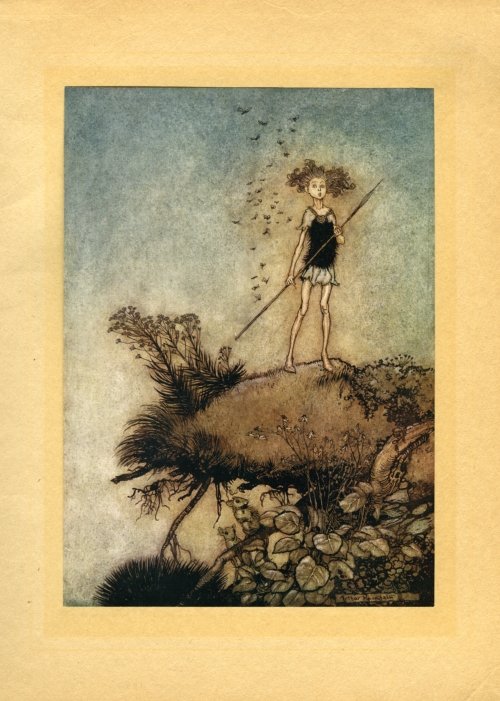

Иди к нам в хоровод

Сумеречные сны

Ундина

Гарет Беуманс побеждает зеленого рыцаря

Цезарина и дракон

Даная

Дракон Гесперид

Гоблины-воры

Спасение Гиневры

Сэр Галахад вытаскивает меч

Жена фэйри

Волшебная чаша

Боярышник

Левиафан

Розовый сад

Игра с опавшими листьями

Изящный танец

Танцующие фэйри

Ссора с птицами

Алиса

Алиса и Синяя Гусеница

Алиса и Грифон

Алиса за столом

Алиса и птицы

Ран — скандинавская богиня воды, великанша, штормовое божество моря

На мой взгляд, очень талантливый художник, один из немногих, кто умел рассказывать легенды и сказки с помощью изобразительного искусства…

Артур Рэкхем — известнейший английский иллюстратор «золотого века», представитель стиля модерн. Его наследие продолжает вдохновлять художников, мультипликаторов, режиссёров. На рубеже XIX–XX веков книги с его иллюстрациями завоевали сердца читателей не только в Великобритании, но и во Франции, Германии, США.

Проиллюстрировал практически всю классическую детскую литературу на английском языке. “Алиса в Стране чудес” с рисунками Рэкхема вышла в 1907 году и сейчас занимает второе место по числу переизданий после книги с каноническими иллюстрациями Джона Тенниела. Он неоднократно удостаивался золотых медалей на всемирных выставках. А в 1914 г. прошла его персональная выставка в Лувре. Книжную графику первой половины XX века можно без преувеличения назвать эпохой Артура Рэкхема!

Крупнейший английский художник-иллюстратор родился в 1867 году в Лондоне в семье высокопоставленного чиновника Адмиралтейства. Получил прекрасное домашнее образование и окончил престижную художественную школу. С 18 лет он работал клерком, одновременно посещая вечернюю школу изящных искусств. В 1888 году работы Рэкхема впервые появились на выставке в Королевской академии художеств. С 1891 года начал сотрудничать с газетами “Вестминстер газет” и “Пэлл Мэлл Баджет”, а в 1894 году получил первый заказ на книжную иллюстрацию для путеводителя по Америке. Далее началась его карьера плодотворного и успешного иллюстратора.

В 1910–1911 годах Рэкхем нарисовал большую серию иллюстраций к “Кольцу Нибелунгов” Рихарда Вагнера и получил золотую медаль на международной выставке в Барселоне. После Первой мировой войны две выставки в Нью-Йорке принесли Рэкхему заказы американских издателей. Неустанно работая, мастер проиллюстрировал “Басни” Эзопа, “Сказки” Ш. Перро, “Бурю” У. Шекспира, “Английские волшебные сказки” Ф. Стил и множество других книг, в основном, сказки для детей. Рэкхем говорил, что “поэтические образы, фантастические и шуточные рисунки и книги для детей играют величайшую стимулирующую и образовательную роль в годы, когда детское воображение наиболее восприимчиво”.

Иллюстрации Рэкхема к вышедшему в 1900 году сборнику сказок братьев Гримм имели большой успех у читателей. Книга переиздавалась несколько раз, причем каждое новое издание выходило в новом оформлении и с новыми рисунками. В 1905 году Рэкхем создал серию рисунков к “Рип Ван Винклю” В. Ирвинга, в 1906 году, по просьбе Джеймса Барри, проиллюстрировал его повесть “Питер Пэн в Кенсингтонском саду”, а в 1907 году вышли в свет “Легенды Инголдсби” с обновленными рисунками. В том же 1907 году издатель Уильям Хейнеманн заказал художнику иллюстрации к “Алисе в Стране чудес” Л. Кэрролла. Рэкхем создал цикл из 13 цветных и 16 черно-белых рисунков, в которых первым из художников отказался от предложенного Кэрроллом и Тенниелом “викторианского” образа Алисы, предложив новую, современную трактовку, соответствующую мировосприятию эпохи модерна. С выходом в свет “Алисы” пришло признание Рэкхема одним из крупнейших мастеров “золотого века” английской книжной графики. В это время творили знаменитые Рэндольф Кальдекотт, Уолтер Крейн, Кейт Гринуэй. Иллюстрации Рэкхема не соперничали с ними, они изначально отличались яркой своеобразной манерой, которой свойственна динамичность и упругость линий, изысканность цветовых решений и композиционное мастерство. Акварели художника выставлялись в самых престижных лондонских галереях, издательства наперебой предлагали ему оформление малотиражных подарочных изданий, которые сразу раскупались библиофилами.

Артур Рэкхем отстаивал высочайшее предназначение детской книги. Он много размышлял о принципах иллюстрирования, о роли художника-иллюстратора: “Чтобы иллюстрации получились стоящими, художник должен чувствовать себя партнёром, а не слугой. Иллюстрация может передавать то, как художник видит идеи автора, или его собственные независимые взгляды; но любая попытка превратить его в примитивное орудие в руках автора неизбежно приведёт к провалу. Иллюстрация столь же многозначна, как и литература. По-настоящему важно лишь взаимопонимание, которое исключало бы разногласия и противоречия. Иллюстратору иногда приходится договаривать то, что должен был, но не смог ясно выразить автор, а подчас и исправлять его промахи. Иногда от него требуется добавить свежести, чтобы оживить читательский интерес. Такое партнёрство весьма продуктивно. Но самая удивительная форма иллюстрирования – это когда художнику удаётся передать собственное восхищение и собственные эмоции от соответствующего отрывка текста”.

Рэкхем был, в первую очередь, блестящим рисовальщиком, отдавая предпочтение прихотливо извивающимся линиям переплетённых ветвей, пенящихся волн и человекообразных деревьев. В книгах он создал сказочный волшебный мир, населенный эльфами и троллями, драконами и гоблинами. Создавая чарующие сказочные иллюстрации, населённые фантастическими персонажами, Рэкхем был верен и правде жизни. Он обладал прекрасной зрительной памятью, в основе всех его волшебных пейзажей – реальные картины: холмы и долины любимой Англии, а моделями для сказочных героев – не только фей, эльфов и гоблинов, но и кротов, лягушек, кроликов и пр. – служили обычные дети. Дочь художника вспоминала, как много раз позировала отцу. Он просил дочь принять какую-нибудь замысловатую позу, девочка терпеливо исполняла задание, но на бумаге изображалась не она, а какой-нибудь зверёк или сказочный персонаж.

Читатели и критики ставили художнику в заслугу то, что его иллюстрации сберегли и удивительным образом преобразили хрупкий мир сказок и легенд. В ретроспективе становится очевидным спокойный и лёгкий юмор его рисунков. Они, кажется, проникнуты нежной радостью, которая, была призвана успокаивать и детей, и их родителей. Образы страшного в его рисунках не угрожающие, они передают острые ощущения и красоту, которая никоим образом не была откровенно сексуальной или непристойной. Техника Рэкхема была идеальной для викторианского времени, он нашёл свою нишу, и, похоже, получал от этого восторженное удовольствие.

В иллюстрациях Рэкхема всегда сохранялась радость и чувство удивления, любования жизнью. Со времени смерти королевы Виктории в 1901 году и до начала Первой мировой войны иллюстрации Рэкхема сохранили красоту образа и чувствительность, держась в стороне от витающих в обществе страхов за будущее. Его прекрасные тонкие рисунки были антитезой тем самым промышленным достижениям, которые позволяли печатать их по доступным ценам. Даже в тревожные двадцатые и тридцатые годы его искусство было постоянным напоминанием о чистоте и невинности, которые общество оставило позади. Мир стремительно менялся, становился всё более рациональным, устремлённым в будущее. Рэкхем же, оставаясь романтиком, вновь и вновь звал читателей оглянуться, вспомнить, сохранить веру в чудеса, почувствовать драгоценную значимость нереального мира фей и эльфов, мира детской фантазии.

Представитель стиля модерн, Рэкхем признавал влияние таких иллюстраторов, как Джордж Крукшенк и Обри Бердслей. В свою очередь, его влияние чувствуется в первых мультипликационных фильмах Диснея, в фильмах Тима Бёртона (который избрал своим лондонским офисом бывшую квартиру Рэкхема) и Гильермо дель Торо (который говорит, что вдохновлялся рисунками Рэкхема при создании “Лабиринта Фавна”).

В 1939 художник, уже прикованный к постели, завершил свою последнюю работу — иллюстрации к сказке Кеннета Грэма “Ветер в ивах”. Рэкхем умер через несколько недель после того, как создал последнюю иллюстрацию к этой книге.

Текст подготовила Валерия Ольховская

|

Arthur Rackham |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1934 |

|

| Born | 19 September 1867

London, England |

| Died | 6 September 1939 (aged 71)

Limpsfield, Surrey, England |

| Known for | Children’s literature, Illustration |

Arthur Rackham RWS (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator. He is recognised as one of the leading figures during the Golden Age of British book illustration. His work is noted for its robust pen and ink drawings, which were combined with the use of watercolour, a technique he developed due to his background as a journalistic illustrator.

Rackham’s 51 colour pieces for the early American tale Rip Van Winkle became a turning point in the production of books since – through colour-separated printing – it featured the accurate reproduction of colour artwork.[1] His best-known works also include the illustrations for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm.

Biography[edit]

Rackham was born at 210 South Lambeth Road, Vauxhall, London as one of 12 children. In 1884, at the age of 17, he was sent on an ocean voyage to Australia to improve his fragile health, accompanied by two aunts.[2] At the age of 18, he worked as an insurance clerk at the Westminster Fire Office and began studying part-time at the Lambeth School of Art.[3]

In 1892, he left his job and started working for the Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. His first book illustrations were published in 1893 in To the Other Side by Thomas Rhodes, but his first serious commission was in 1894 for The Dolly Dialogues, the collected sketches of Anthony Hope, who later went on to write The Prisoner of Zenda. Book illustrating then became Rackham’s career for the rest of his life.

By the turn of the century, Rackham had developed a reputation for pen and ink fantasy illustration with richly illustrated gift books such as The Ingoldsby Legends (1898), Gulliver’s Travels and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (both 1900). This was developed further through the austere years of the Boer War with regular contributions to children’s periodicals such as Little Folks and Cassell’s Magazine. In 1901 he moved to Wychcombe Studios near Haverstock Hill, and in 1903 married his neighbour Edyth Starkie.[4] Edyth suffered a miscarriage in 1904, but the couple had one daughter, Barbara, in 1908. Although acknowledged as an accomplished black-and-white book illustrator for some years, it was the publication of his full-colour plates to Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle by Heinemann in 1905 that particularly brought him into public attention, his reputation being confirmed the following year with J.M.Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, published by Hodder & Stoughton. Income from the books was greatly augmented by annual exhibitions of the artwork at the Leicester Galleries. Rackham won a gold medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and another one at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His works were included in numerous exhibitions, including one at the Louvre in Paris in 1914. Rackham was a member of the Art Workers’ Guild and was elected its Master in 1919.[5]

From 1906 the family lived in Chalcot Gardens, near Haverstock Hill,[6] until moving from London to Houghton, West Sussex in 1920. In 1929, the family settled into a newly built property in Limpsfield, Surrey.[7] Ten years later, Arthur Rackham died at home of cancer.

Significance[edit]

Arthur Rackham is widely regarded as one of the leading illustrators from the ‘Golden Age’ of British book illustration which roughly encompassed the years from 1890 until the end of the First World War. During that period, there was a strong market for high quality illustrated books which typically were given as Christmas gifts. Many of Rackham’s books were produced in a de luxe limited edition, often vellum bound and usually signed, as well as a smaller, less ornately bound quarto ‘trade’ edition. This was sometimes followed by a more modestly presented octavo edition in subsequent years for particularly popular books. The onset of the war in 1914 curtailed the market for such quality books, and the public’s taste for fantasy and fairies also declined in the 1920s.

Sutherland, referring to Rackham’s work in the 20th Century, states: «Rackman was, without doubt, one of the finest illustrators of the century.»[8] In his survey of British Book Illustration, Salaman stated: «Mr. Rackham stands apart from all the other illustrators of the day; his genius is so thoroughly original. Scores of others have depicted fairyland and wonderland, but who else has given us so absolutely individual and persuasively suggestive a vision of their marvels and allurements? Whose elves are so elfish, whose witches and gnomes are so convincingly of their kind, as Mr. Rackham’s?»[9]

Carpenter and Prichard noted that «For all the virtuosity of his work in colour, Rackham remained an artist in line, his mastery having its roots in his early work for periodicals, then breaking free to create the swirling intricate pictures of his prime, and finally reaching the economy and impressionism of his last work.» They also remarked on his decline: «Rackham made his name in a heyday of fairy literature and other fantasy which the First World War brought to an end.»[10] House stated that Rackham «concentrated on the illustration of books and particularly those of a mystical, magic or legendary background. He very soon established himself as one of the foremost Edwardian illustrators and was triumphant in the early 1900s when colour printing first enabled him to use subtle tints and muted tones to represent age and timelessness. Rackham’s imaginative eye saw all forms with the eyes of childhood and created a world that was half reassuring and half frightening.»[11]

Hamilton summarised his article on Rackham in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography thus: «Rackham brought a renewed sense of excitement to book illustration that coincided with the rapid developments in printing technology in the early twentieth century. Working with subtle colour and wiry line, he exploited the growing strengths of commercial printing to create imagery and characterizations that reinvigorated children’s literature, electrified young readers, and dominated the art of book illustration at the start of a new century.»[12]

Arthur Rackham’s works have become very popular since his death, both in North America and Britain. His images have been widely used by the greeting card industry and many of his books are still in print or have been recently available in both paperback and hardback editions. His original drawings and paintings are keenly sought at the major international art auction houses.

Technique[edit]

Cinderella silhouette illustration, 1919

Rackham’s illustrations were chiefly based on robust pen and India ink drawings. Rackham gradually perfected his own uniquely expressive line from his background in journalistic illustration, paired with subtle use of watercolour, a technique which he was able to exploit due to technological developments in photographic reproduction. With this development, Rackham’s illustrations no longer needed an engraver (lacking Rackham’s talent) to cut clean lines on a wood or metal plate for printing because the artist merely had his works photographed and mechanically reproduced.[13]

Rackham would first lightly block in shapes and details of the drawing with a soft pencil, for the more elaborate colour plates often utilising one of a small selection of compositional devices.[14] Over this, he would then carefully work in lines of pen and India ink, removing the pencil traces after the drawing had begun to take form. For colour pictures, Rackham preferred the 3-colour process or trichromatic printing, which reproduced the delicate half-tones of photography through letterpress printing.[15] He would begin painting by building up multiple thin washes of watercolour creating translucent tints. One of the disadvantages of the 3-colour (later 4-colour) printing process in the early years was that definition could be lost in the final print. Rackham would sometimes compensate for this by over-inking his drawings once more after painting.[16] He would also go on to expand the use of silhouette cuts in illustration work, particularly in the period after the First World War, as exemplified by his Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella.[17]

Typically, Rackham contributed both colour and monotone illustrations towards the works incorporating his images – and in the case of Hawthorne’s Wonder Book, he also provided a number of part-coloured block images similar in style to Meiji era Japanese woodblocks.

Rackham’s work is often described as a fusion of a northern European ‘Nordic’ style strongly influenced by the Japanese woodblock tradition of the early 19th century.

Notable works[edit]

Frontispiece of English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel, 1918

Memorial plaque to Arthur Rackham and Edyth Starkie Rackham, St. Michael’s Church, Amberley, West Sussex

- Sunrise-Land by Berlyn Annie (Jarrold, 1894)

- The Sketch Book by Washington Irving (Putnam, 1895)

- The Zankiwank and the Bletherwitch by Shafto Justin Adair Fitzgerald (40 line, 1896)

- Two Old Ladies, Two Foolish Fairies, and a Tom Cat by Maggie Browne (pseudonym of Margaret Hamer) (4 colour plates, 19 line, Cassel, London, 1897)

- Evelina by Fanny Burney (Newnes, London, 1898)

- Feats on the Fjord by Harriet Martineau (f/p colour, 11 line, 1899)[18]

- The Greek Heroes by Barthold Georg Niebuhr (4 colour plates, 8 line, 1903)

- Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving (51 colour plates, 3 line, William Heinemann, London, 1905)

- Puck of Pook’s Hill by Rudyard Kipling (4 colour plates; 1906, Doubleday, Page & Co. (one US ed.))

- Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by J.M. Barrie (49 colour plates, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1906)

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (13 colour plates, 15 line, William Heinemann, London, 1907)

- The Ingoldsby Legends by Thomas Ingoldsby (12 colour, 80 line 1898; reworked edition 23 colour plates, 73 line, J.M. Dent, London, 1907)

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (40 colour plates, 34 line, William Heinemann, London, 1908)

- Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb (colour F/P, 11 line 1899, reworked edition 12 colour plates, 37 line, 1909)

- Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm by the Brothers Grimm (95 line, 1900, reworked edition 40 colour plates, 62 line, 1909)

- Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (Colour F/P, 11 line 1900, reworked edition 12 colour plates, 34 line, 1909)

- Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué (15 colour plates, 41 line, William Heinemann, London, 1909)

- The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie by Richard Wagner (34 colour plates, 8 line, William Heinemann, London, 1910)

- Siegfried and Twilight of the Gods by Richard Wagner (32 colour plates, 8 line, William Heinemann, London, 1911)

- Aesop’s Fables by Aesop (13 colour plates, 82 line, William Heinemann, London, 1912)

- Arthur Rackham’s Book of Pictures (44 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1913)

- Mother Goose: The Old Nursery Rhymes by Charles Perrault (13 colour plates, mostly reprinted from the US monthly St. Nicholas Magazine, 78 line, 1913)

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (12 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1915)

- The Allies’ Fairy Book with an introduction by Edmund Gosse (12 colour plates, 23 line, William Heinemann, London, 1916)

- Little Brother and Little Sister and Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm (13 colour plates, 45 line, 1917)

- The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Alfred W. Pollard (23 colour and monotone plates, 16 line, 1917)

- English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel (16 colour plates, 43 line, 1918)

- The Springtide of Life: Poems of Childhood by Algernon Charles Swinburne (8 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1918)

- Some British Ballads (16 colour plates, 23 line, 1918)

- Cinderella by Charles Perrault, ed. Charles S. Evans (1 colour plate, 60 silhouettes, William Heinemann, London, 1919)

- The Sleeping Beauty by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, ed. Charles S. Evans (1 colour plate, 65 silhouettes, William Heinemann, London, 1920)

- Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens (16 colour plates, 20 line, 1920)

- Snowdrop and Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm (20 colour plates, 29 line, 1920)

- Comus by John Milton (22 colour plates, 35 line, 1921)

- A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys by Nathaniel Hawthorne (16 colour plates, 21 line, 1922)

- Poor Cecco by Margery Williams (7 colour plates, 12 line, 1925)

- The Tempest by William Shakespeare (20 colour plates, 20 line, William Heinemann, London, 1926)

- The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving (8 colour plates, 32 line, 1928)

- The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith (12 colour plates, 23 line, 1929)

- The Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton (12 colour plates, 22 line, 1931)

- The King of the Golden River by John Ruskin (4 colour plates, 13 line, T/P 2 colour, 1932)

- Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen (12 colour plates, 43 line, 9 silhouettes 1932)

- Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (4 colour plates, 19 line, E/P, 1933)

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning (4 colour plates, 15 line, 1 silhouette, E/P, 1934)

- Tales of Mystery & Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe (12 colour plates, 28 line, 1935)

- Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen (12 colour plates, 38 line, 1936)

- The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (16 colour plates; posthumous, 1940 US, 1950 UK)

Gallery[edit]

-

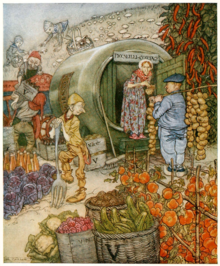

«The giant Galligantua and the wicked old magician transform the duke’s daughter into a white hind», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

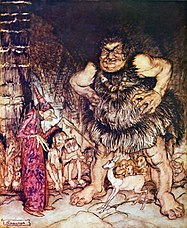

«The giant Cormoran was the terror of all the country-side», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

«The Three Bears», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

-

«The Rhinemaidens warn Siegfried», illustration to Richard Wagner’s The Ring

-

«The Rhinemaidens try to reclaim their gold», illustration to Richard Wagner’s The Ring

-

Influence[edit]

War memorial designed by Eugène Aernauts After the Illustration Unconquerable Belgium By Arthur Rackham. From King Albert’S Book, Published 1915.

Rackham’s work influenced a number of artists. These include Gustaf Tenggren, Brian Froud, William Stout, Tony DiTerlizzi, and Abigail Larson.[19] Froud cites the early influence of Rackham, «in particular, [Rackham’s] drawings of trees that had faces», as sparking his interest in illustrating fairy tales, and describes having had a love of nature from childhood that has informed his style.[20]

According to Arthur Rankin, the visual style of the 1977 film The Hobbit was based on early illustrations by Rackham.[21]

In one of the featurettes on the DVD of Pan’s Labyrinth, and in the commentary track for Hellboy, director Guillermo del Toro cites Rackham as an influence on the design of «The Faun» of Pan’s Labyrinth. He liked the dark tone of Rackham’s gritty realistic drawings and had decided to incorporate that into the film. In Hellboy, the design of the tree growing out of the altar in the ruined abbey off the coast of Scotland where Hellboy was brought over, is actually referred to as a «Rackham tree» by the director.

References[edit]

- ^ Rackham, Arthur; Menges, Jeff (2005). The Arthur Rackham Treasury: 86 Full-Color Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. v. ISBN 9780486446851.

- ^ Hudson, Derek, Arthur Rackham: His Life and Work, Heinemann London 1960

- ^ Silvey, 373

- ^ James Hamilton – Arthur Rackham, A Biography, Arcade Publishing NY 1990. p.65

- ^ Bury. S (2012). Benezit Dictionary of British Graphic Artists and Illustrators, Volume 1. ISBN 9780199923052.

- ^ Hamilton p.79

- ^ Hamilton p.119

- ^ Sutherland, John (1989). «The Illustrators: Rackham, Arthur». The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 342.

- ^ Salaman, M. C.; Holme, C. Geoffrey; Halton, Ernest G. (1894). «British Book Illustration». Modern Book Illustrators and their work. London: The Studio Ltd. p. 7.

- ^ Carpenter-440, Humphrey; Prichard, Mari (1984). «Rackham, Arthur (1867-1939)». The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 440.

- ^ Houfe, Simon (1978). «Rainey, William RBA RI 1852-1936». Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club. p. 426. ISBN 9780902028739. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, James Stanley (23 September 2004). «Rackham, Arthur, (1867-1939)». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35645. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Style, Subjects, Technique, and Technology | Central Michigan University». www.cmich.edu. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Gettings, Fred: Arthur Rackham (Studio Vista 1975, p.55-76)

- ^ Lupack, Barbara; Lupack, Alan (2008). Illustrating Camelot. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 9781843841838.

- ^ Gettings p.51

- ^ «Clarke Home | Central Michigan University». cmich.edu.

- ^ Project Gutenberg: Feats on the Fjord.

- ^ «About». 15 February 2020.

- ^ Barder, Ollie (13 September 2019). «Brian Froud On ‘The Dark Crystal’, ‘Labyrinth’ And His Love Of Nature». Forbes. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Culhan, John (27 November 1977). «Will the Video Version of Tolkien Be Hobbit Forming?». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

External links[edit]

- Works by Arthur Rackham at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Arthur Rackham at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Arthur Rackham at Internet Archive

- Little brother & little sister and other tales by the Brothers Grimm illustrated by Arthur Rackham, 1917

- Arthur Rackham’s illustrations for Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends

- Innovated Life Art Gallery: Select illustrations by Arthur Rackham, biography and contemporary reviews

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by Arthur Rackham

- Arthur Rackham art at Art Passions (free online gallery)

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Fairy Tale Illustrations of Arthur Rackham Archived 6 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Arthur Rackham artwork at American Art Archives web site

- Complete Arthur Rackham Collection for ‘The Ring of the Nibelung’

- Information about Arthur Rackham and his art

- Large Archive of Arthur Rackham’s Artwork at The Golden Age Children’s Book Illustrations Gallery

- Arthur Rackham Papers at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, NY

|

Arthur Rackham |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1934 |

|

| Born | 19 September 1867

London, England |

| Died | 6 September 1939 (aged 71)

Limpsfield, Surrey, England |

| Known for | Children’s literature, Illustration |

Arthur Rackham RWS (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator. He is recognised as one of the leading figures during the Golden Age of British book illustration. His work is noted for its robust pen and ink drawings, which were combined with the use of watercolour, a technique he developed due to his background as a journalistic illustrator.

Rackham’s 51 colour pieces for the early American tale Rip Van Winkle became a turning point in the production of books since – through colour-separated printing – it featured the accurate reproduction of colour artwork.[1] His best-known works also include the illustrations for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm.

Biography[edit]

Rackham was born at 210 South Lambeth Road, Vauxhall, London as one of 12 children. In 1884, at the age of 17, he was sent on an ocean voyage to Australia to improve his fragile health, accompanied by two aunts.[2] At the age of 18, he worked as an insurance clerk at the Westminster Fire Office and began studying part-time at the Lambeth School of Art.[3]

In 1892, he left his job and started working for the Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. His first book illustrations were published in 1893 in To the Other Side by Thomas Rhodes, but his first serious commission was in 1894 for The Dolly Dialogues, the collected sketches of Anthony Hope, who later went on to write The Prisoner of Zenda. Book illustrating then became Rackham’s career for the rest of his life.

By the turn of the century, Rackham had developed a reputation for pen and ink fantasy illustration with richly illustrated gift books such as The Ingoldsby Legends (1898), Gulliver’s Travels and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (both 1900). This was developed further through the austere years of the Boer War with regular contributions to children’s periodicals such as Little Folks and Cassell’s Magazine. In 1901 he moved to Wychcombe Studios near Haverstock Hill, and in 1903 married his neighbour Edyth Starkie.[4] Edyth suffered a miscarriage in 1904, but the couple had one daughter, Barbara, in 1908. Although acknowledged as an accomplished black-and-white book illustrator for some years, it was the publication of his full-colour plates to Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle by Heinemann in 1905 that particularly brought him into public attention, his reputation being confirmed the following year with J.M.Barrie’s Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, published by Hodder & Stoughton. Income from the books was greatly augmented by annual exhibitions of the artwork at the Leicester Galleries. Rackham won a gold medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and another one at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His works were included in numerous exhibitions, including one at the Louvre in Paris in 1914. Rackham was a member of the Art Workers’ Guild and was elected its Master in 1919.[5]

From 1906 the family lived in Chalcot Gardens, near Haverstock Hill,[6] until moving from London to Houghton, West Sussex in 1920. In 1929, the family settled into a newly built property in Limpsfield, Surrey.[7] Ten years later, Arthur Rackham died at home of cancer.

Significance[edit]

Arthur Rackham is widely regarded as one of the leading illustrators from the ‘Golden Age’ of British book illustration which roughly encompassed the years from 1890 until the end of the First World War. During that period, there was a strong market for high quality illustrated books which typically were given as Christmas gifts. Many of Rackham’s books were produced in a de luxe limited edition, often vellum bound and usually signed, as well as a smaller, less ornately bound quarto ‘trade’ edition. This was sometimes followed by a more modestly presented octavo edition in subsequent years for particularly popular books. The onset of the war in 1914 curtailed the market for such quality books, and the public’s taste for fantasy and fairies also declined in the 1920s.

Sutherland, referring to Rackham’s work in the 20th Century, states: «Rackman was, without doubt, one of the finest illustrators of the century.»[8] In his survey of British Book Illustration, Salaman stated: «Mr. Rackham stands apart from all the other illustrators of the day; his genius is so thoroughly original. Scores of others have depicted fairyland and wonderland, but who else has given us so absolutely individual and persuasively suggestive a vision of their marvels and allurements? Whose elves are so elfish, whose witches and gnomes are so convincingly of their kind, as Mr. Rackham’s?»[9]

Carpenter and Prichard noted that «For all the virtuosity of his work in colour, Rackham remained an artist in line, his mastery having its roots in his early work for periodicals, then breaking free to create the swirling intricate pictures of his prime, and finally reaching the economy and impressionism of his last work.» They also remarked on his decline: «Rackham made his name in a heyday of fairy literature and other fantasy which the First World War brought to an end.»[10] House stated that Rackham «concentrated on the illustration of books and particularly those of a mystical, magic or legendary background. He very soon established himself as one of the foremost Edwardian illustrators and was triumphant in the early 1900s when colour printing first enabled him to use subtle tints and muted tones to represent age and timelessness. Rackham’s imaginative eye saw all forms with the eyes of childhood and created a world that was half reassuring and half frightening.»[11]

Hamilton summarised his article on Rackham in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography thus: «Rackham brought a renewed sense of excitement to book illustration that coincided with the rapid developments in printing technology in the early twentieth century. Working with subtle colour and wiry line, he exploited the growing strengths of commercial printing to create imagery and characterizations that reinvigorated children’s literature, electrified young readers, and dominated the art of book illustration at the start of a new century.»[12]

Arthur Rackham’s works have become very popular since his death, both in North America and Britain. His images have been widely used by the greeting card industry and many of his books are still in print or have been recently available in both paperback and hardback editions. His original drawings and paintings are keenly sought at the major international art auction houses.

Technique[edit]

Cinderella silhouette illustration, 1919

Rackham’s illustrations were chiefly based on robust pen and India ink drawings. Rackham gradually perfected his own uniquely expressive line from his background in journalistic illustration, paired with subtle use of watercolour, a technique which he was able to exploit due to technological developments in photographic reproduction. With this development, Rackham’s illustrations no longer needed an engraver (lacking Rackham’s talent) to cut clean lines on a wood or metal plate for printing because the artist merely had his works photographed and mechanically reproduced.[13]

Rackham would first lightly block in shapes and details of the drawing with a soft pencil, for the more elaborate colour plates often utilising one of a small selection of compositional devices.[14] Over this, he would then carefully work in lines of pen and India ink, removing the pencil traces after the drawing had begun to take form. For colour pictures, Rackham preferred the 3-colour process or trichromatic printing, which reproduced the delicate half-tones of photography through letterpress printing.[15] He would begin painting by building up multiple thin washes of watercolour creating translucent tints. One of the disadvantages of the 3-colour (later 4-colour) printing process in the early years was that definition could be lost in the final print. Rackham would sometimes compensate for this by over-inking his drawings once more after painting.[16] He would also go on to expand the use of silhouette cuts in illustration work, particularly in the period after the First World War, as exemplified by his Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella.[17]

Typically, Rackham contributed both colour and monotone illustrations towards the works incorporating his images – and in the case of Hawthorne’s Wonder Book, he also provided a number of part-coloured block images similar in style to Meiji era Japanese woodblocks.

Rackham’s work is often described as a fusion of a northern European ‘Nordic’ style strongly influenced by the Japanese woodblock tradition of the early 19th century.

Notable works[edit]

Frontispiece of English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel, 1918

Memorial plaque to Arthur Rackham and Edyth Starkie Rackham, St. Michael’s Church, Amberley, West Sussex

- Sunrise-Land by Berlyn Annie (Jarrold, 1894)

- The Sketch Book by Washington Irving (Putnam, 1895)

- The Zankiwank and the Bletherwitch by Shafto Justin Adair Fitzgerald (40 line, 1896)

- Two Old Ladies, Two Foolish Fairies, and a Tom Cat by Maggie Browne (pseudonym of Margaret Hamer) (4 colour plates, 19 line, Cassel, London, 1897)

- Evelina by Fanny Burney (Newnes, London, 1898)

- Feats on the Fjord by Harriet Martineau (f/p colour, 11 line, 1899)[18]

- The Greek Heroes by Barthold Georg Niebuhr (4 colour plates, 8 line, 1903)

- Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving (51 colour plates, 3 line, William Heinemann, London, 1905)

- Puck of Pook’s Hill by Rudyard Kipling (4 colour plates; 1906, Doubleday, Page & Co. (one US ed.))

- Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens by J.M. Barrie (49 colour plates, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1906)

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (13 colour plates, 15 line, William Heinemann, London, 1907)

- The Ingoldsby Legends by Thomas Ingoldsby (12 colour, 80 line 1898; reworked edition 23 colour plates, 73 line, J.M. Dent, London, 1907)

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (40 colour plates, 34 line, William Heinemann, London, 1908)

- Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb (colour F/P, 11 line 1899, reworked edition 12 colour plates, 37 line, 1909)

- Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm by the Brothers Grimm (95 line, 1900, reworked edition 40 colour plates, 62 line, 1909)

- Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift (Colour F/P, 11 line 1900, reworked edition 12 colour plates, 34 line, 1909)

- Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué (15 colour plates, 41 line, William Heinemann, London, 1909)

- The Rhinegold and The Valkyrie by Richard Wagner (34 colour plates, 8 line, William Heinemann, London, 1910)

- Siegfried and Twilight of the Gods by Richard Wagner (32 colour plates, 8 line, William Heinemann, London, 1911)

- Aesop’s Fables by Aesop (13 colour plates, 82 line, William Heinemann, London, 1912)

- Arthur Rackham’s Book of Pictures (44 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1913)

- Mother Goose: The Old Nursery Rhymes by Charles Perrault (13 colour plates, mostly reprinted from the US monthly St. Nicholas Magazine, 78 line, 1913)

- A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (12 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1915)

- The Allies’ Fairy Book with an introduction by Edmund Gosse (12 colour plates, 23 line, William Heinemann, London, 1916)

- Little Brother and Little Sister and Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm (13 colour plates, 45 line, 1917)

- The Romance of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Alfred W. Pollard (23 colour and monotone plates, 16 line, 1917)

- English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel (16 colour plates, 43 line, 1918)

- The Springtide of Life: Poems of Childhood by Algernon Charles Swinburne (8 colour plates, William Heinemann, London, 1918)

- Some British Ballads (16 colour plates, 23 line, 1918)

- Cinderella by Charles Perrault, ed. Charles S. Evans (1 colour plate, 60 silhouettes, William Heinemann, London, 1919)

- The Sleeping Beauty by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm, ed. Charles S. Evans (1 colour plate, 65 silhouettes, William Heinemann, London, 1920)

- Irish Fairy Tales by James Stephens (16 colour plates, 20 line, 1920)

- Snowdrop and Other Tales by the Brothers Grimm (20 colour plates, 29 line, 1920)

- Comus by John Milton (22 colour plates, 35 line, 1921)

- A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys by Nathaniel Hawthorne (16 colour plates, 21 line, 1922)

- Poor Cecco by Margery Williams (7 colour plates, 12 line, 1925)

- The Tempest by William Shakespeare (20 colour plates, 20 line, William Heinemann, London, 1926)

- The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving (8 colour plates, 32 line, 1928)

- The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver Goldsmith (12 colour plates, 23 line, 1929)

- The Compleat Angler by Izaak Walton (12 colour plates, 22 line, 1931)

- The King of the Golden River by John Ruskin (4 colour plates, 13 line, T/P 2 colour, 1932)

- Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen (12 colour plates, 43 line, 9 silhouettes 1932)

- Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti (4 colour plates, 19 line, E/P, 1933)

- The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Robert Browning (4 colour plates, 15 line, 1 silhouette, E/P, 1934)

- Tales of Mystery & Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe (12 colour plates, 28 line, 1935)

- Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen (12 colour plates, 38 line, 1936)

- The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame (16 colour plates; posthumous, 1940 US, 1950 UK)

Gallery[edit]

-

«The giant Galligantua and the wicked old magician transform the duke’s daughter into a white hind», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

«The giant Cormoran was the terror of all the country-side», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

«The Three Bears», illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

-

-

«The Rhinemaidens warn Siegfried», illustration to Richard Wagner’s The Ring

-

«The Rhinemaidens try to reclaim their gold», illustration to Richard Wagner’s The Ring

-

Influence[edit]

War memorial designed by Eugène Aernauts After the Illustration Unconquerable Belgium By Arthur Rackham. From King Albert’S Book, Published 1915.

Rackham’s work influenced a number of artists. These include Gustaf Tenggren, Brian Froud, William Stout, Tony DiTerlizzi, and Abigail Larson.[19] Froud cites the early influence of Rackham, «in particular, [Rackham’s] drawings of trees that had faces», as sparking his interest in illustrating fairy tales, and describes having had a love of nature from childhood that has informed his style.[20]

According to Arthur Rankin, the visual style of the 1977 film The Hobbit was based on early illustrations by Rackham.[21]

In one of the featurettes on the DVD of Pan’s Labyrinth, and in the commentary track for Hellboy, director Guillermo del Toro cites Rackham as an influence on the design of «The Faun» of Pan’s Labyrinth. He liked the dark tone of Rackham’s gritty realistic drawings and had decided to incorporate that into the film. In Hellboy, the design of the tree growing out of the altar in the ruined abbey off the coast of Scotland where Hellboy was brought over, is actually referred to as a «Rackham tree» by the director.

References[edit]

- ^ Rackham, Arthur; Menges, Jeff (2005). The Arthur Rackham Treasury: 86 Full-Color Illustrations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. v. ISBN 9780486446851.

- ^ Hudson, Derek, Arthur Rackham: His Life and Work, Heinemann London 1960

- ^ Silvey, 373

- ^ James Hamilton – Arthur Rackham, A Biography, Arcade Publishing NY 1990. p.65

- ^ Bury. S (2012). Benezit Dictionary of British Graphic Artists and Illustrators, Volume 1. ISBN 9780199923052.

- ^ Hamilton p.79

- ^ Hamilton p.119

- ^ Sutherland, John (1989). «The Illustrators: Rackham, Arthur». The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 342.

- ^ Salaman, M. C.; Holme, C. Geoffrey; Halton, Ernest G. (1894). «British Book Illustration». Modern Book Illustrators and their work. London: The Studio Ltd. p. 7.

- ^ Carpenter-440, Humphrey; Prichard, Mari (1984). «Rackham, Arthur (1867-1939)». The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 440.

- ^ Houfe, Simon (1978). «Rainey, William RBA RI 1852-1936». Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club. p. 426. ISBN 9780902028739. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Hamilton, James Stanley (23 September 2004). «Rackham, Arthur, (1867-1939)». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35645. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ «Style, Subjects, Technique, and Technology | Central Michigan University». www.cmich.edu. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ Gettings, Fred: Arthur Rackham (Studio Vista 1975, p.55-76)

- ^ Lupack, Barbara; Lupack, Alan (2008). Illustrating Camelot. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 9781843841838.

- ^ Gettings p.51

- ^ «Clarke Home | Central Michigan University». cmich.edu.

- ^ Project Gutenberg: Feats on the Fjord.

- ^ «About». 15 February 2020.

- ^ Barder, Ollie (13 September 2019). «Brian Froud On ‘The Dark Crystal’, ‘Labyrinth’ And His Love Of Nature». Forbes. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ Culhan, John (27 November 1977). «Will the Video Version of Tolkien Be Hobbit Forming?». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

External links[edit]

- Works by Arthur Rackham at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Arthur Rackham at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Arthur Rackham at Internet Archive

- Little brother & little sister and other tales by the Brothers Grimm illustrated by Arthur Rackham, 1917

- Arthur Rackham’s illustrations for Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends

- Innovated Life Art Gallery: Select illustrations by Arthur Rackham, biography and contemporary reviews

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by Arthur Rackham

- Arthur Rackham art at Art Passions (free online gallery)

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Fairy Tale Illustrations of Arthur Rackham Archived 6 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Arthur Rackham artwork at American Art Archives web site

- Complete Arthur Rackham Collection for ‘The Ring of the Nibelung’

- Information about Arthur Rackham and his art

- Large Archive of Arthur Rackham’s Artwork at The Golden Age Children’s Book Illustrations Gallery

- Arthur Rackham Papers at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, NY