История «Лебединого озера»

История «Лебединого озера»

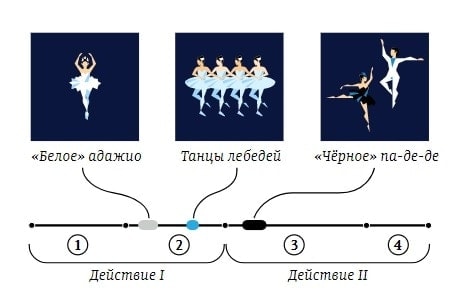

В 1877 году в московском Большом театре был впервые поставлен танцевальный спектакль, который сегодня знают все. На свет появился балет «Лебединое озеро». С тех пор так или иначе, но история мировой хореографии связана с волшебной «средневековой» сказкой о заколдованной девушке, влюбленном принце и злом волшебнике.

Считается, что Чайковского вдохновило посещение Баварии, где композитор увидел знаменитый Нойшванштайн — «лебединый замок» короля Людвига Второго. К слову, декорации к классическим постановкам до сих пор изображают готический замок в горах. В 1871 году композитор написал для своих родственников одноактный детский балет «Озеро лебедей». А поводом для создания бессмертной партитуры стал заказ Московской дирекции Императорских театров. Чайковский, часто — и, в принципе, охотно — сочинявший по заказам, взялся за этот труд, как он писал, «отчасти ради денег, в которых нуждаюсь, отчасти потому, что … давно хотелось попробовать себя в этом роде музыки». Для балета частично использовалась партитура уничтоженной композитором оперы «Ундина».

В истории балета партитура «Озера» революционна: Чайковский написал ритмически удобную для танцев музыку, но на место простоватых мелодий и незатейливых дивертисментов пришли высокие поэтические обобщения, сквозные лирические темы, что впоследствии позволило по-новому подойти к созданию хореографии.

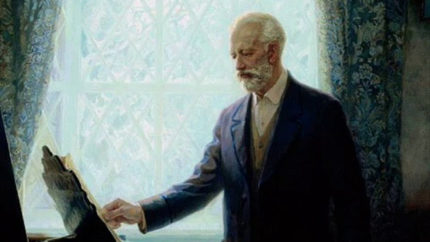

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Марина Семёнова в роли Одиллии. Ленинград, первая четверть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Константин Сергеев в роли Зигфрида. Ленинград, 1936 год

Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург / Фотография Евгения Рагузина

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Ольга Лепешинская в роли Одиллии. Москва, 1933 год

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Марина Семёнова в роли Одиллии. Ленинград, первая четверть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Константин Сергеев в роли Зигфрида. Ленинград, 1936 год

Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург / Фотография Евгения Рагузина

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Ольга Лепешинская в роли Одиллии. Москва, 1933 год

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Первое либретто «Озера», основанное на немецком колорите, написано как бы не всерьез, ирония часто направлена на балетные штампы, даже с примечанием «как это всегда бывает в балетах…».

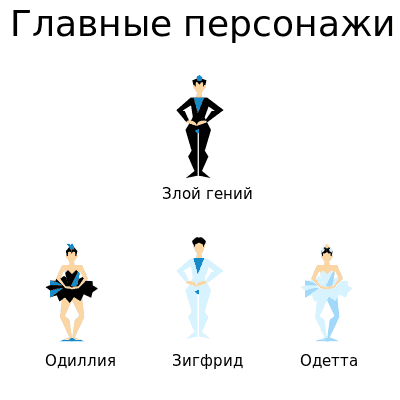

Первоначально сюжет был таким: принц Зигфрид празднует совершеннолетие. Друг принца, увидев пролетающих лебедей, зовет его на охоту. Юноша попадает в «гористую дикую местность» с озером. При свете луны заколдованные лебеди сбрасывают крылья, становясь девушками во главе с Одеттой. Принц влюбляется в нее. На балу во дворце для принца танцуют красавицы, но он полон воспоминаний об озере и не хочет выбрать себе невесту. Неожиданно прибывает «злой гений» фон Ротбарт с дочерью Одиллией. Коварная девица притворяется Одеттой и обольщает принца. Он дает клятву верности, тем самым предавая Одетту. «Сцена мгновенно темнеет, раздается крик совы, одежда спадает с фон Ротбарта, и он является в виде демона. Одиллия хохочет. Окно с шумом распахивается, и на окне показывается белая лебедь с короной на голове. Принц с ужасом бросает руку своей новой подруги и, хватаясь за сердце, бежит вон из замка».

Последнее действие во многом совпадает с тем, что мы видим сегодня. Герои, сопротивляясь козням Ротбарта, гибнут в волнах озера.

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Софья Головкина в роли Одетты. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Владимир Преображенский в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Юрий Жданов в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Софья Головкина в роли Одетты. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Владимир Преображенский в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Юрий Жданов в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

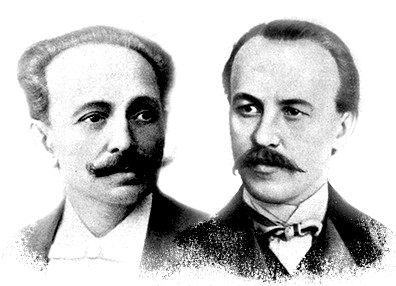

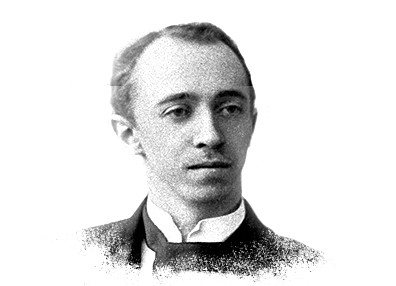

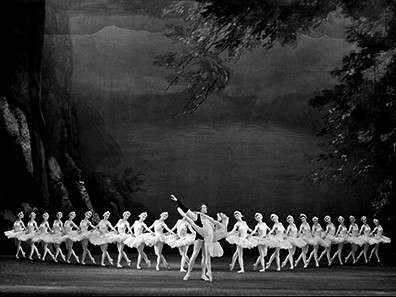

Первая постановка 1877 года, сделанная посредственным московским балетмейстером Рейзингером, имела плохую прессу и фактически провалилась. Второе рождение балета произошло в 1895 году в Петербурге. О партитуре вспомнили, желая почтить память умершего Чайковского. Брат композитора Модест Ильич переделал либретто. Из него исчезла сова, зато оставшийся Ротбарт приобрел — на долгие годы — птичьи черты (в тексте он назван филином). На этот раз музыка попала в талантливые руки — за балет взялись два выдающихся балетмейстера Императорских театров Мариус Петипа и Лев Иванов. Иванов, обладая редкой музыкальностью, поставил знаменитые «лебединые» сцены на озере — «симфонические» картины сражения с судьбой, в образах, полных зачарованной красоты и элегической прелести. Хореограф придал сценическим лебедям облик, близкий к современному — без бутафорских крыльев с наклеенными перьями. Взамен этого он ввел «танцы рук». В балете появились дуэт Одетты и Зигфрида, знаменитый Танец маленьких лебедей. Герои посмертно уплывали на золотой ладье. Спектакль, основанный на теме лебедей-двойников, конфликте неискушенности с коварством и пробе души на верность, уходил в невиданные ранее в балете психологические глубины.

Но первым делом постановщики нового «Лебединого озера» серьезно вторглись в музыку (обычное для балетных партитур дело). Дирижер Риккардо Дриго не только переставил местами музыкальные фрагменты, но и добавил новые. Спектакль прошел с успехом. Именно эта версия легла в основу многочисленных последующих переделок и редакций.

Агриппина Ваганова, бывшая танцовщица Императорского балета, а после 1917 года — признанный балетный педагог, стала автором всем известной ныне позы рук у лебедей и усилила «птичий» акцент во взмахах рук-крыльев: у нее в спектакле не было заколдованных девушек, а были именно птицы, прочее придумывает мечтатель Зигфрид.

Агриппина Ваганова в роли Одетты. Санкт-Петербург, 1912 год

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро»

Педагог и балетмейстер Агриппина Ваганова со своими ученицами. Ленинград, 1946 год

На десятилетия прижилась на сцене Кировского (бывшего Мариинского) театра редакция Константина Сергеева, в которой автор сам сочинил многое, но оставил лучшие фрагменты предшественников, прежде всего — лебединые сцены Иванова.

На десятилетия прижилась на сцене Кировского (бывшего Мариинского) театра редакция Константина Сергеева, в которой автор сам сочинил многое, но оставил лучшие фрагменты предшественников, прежде всего — лебединые сцены Иванова.

|

В 1953 году в Москве появилась оригинальная версия, которую и сегодня можно увидеть на сцене Музыкального театра имени Станиславского и Немировича-Данченко. Ее придумал хореограф Владимир Бурмейстер. В неприкосновенности был оставлен «белый» акт Льва Иванова с заколдованными лебедями на озере. Все прочее — авторская работа. Хореограф остановился на счастливой концовке (Лебедь расколдован) и поставил своеобразное «вступление»: на наших глазах девушку превращают в птицу, причем колдун с огромными крыльями оживает из скалы. |

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Виолетта Бовт в роли Одетты-Одиллии, Алексей Чичинадзе в роли принца, Алексей Клейн в роли Ротбарта. Хореограф Владимир Бурмейстер. Москва, 1953 год.

Московский академический Музыкальный театр имени К. С. Станиславского и В.И. Немировича-Данченко, Москва

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Виолетта Бовт в роли Одетты-Одиллии, Алексей Чичинадзе в роли принца, Алексей Клейн в роли Ротбарта. Хореограф Владимир Бурмейстер. Москва, 1953 год.

Московский академический Музыкальный театр имени К. С. Станиславского и В.И. Немировича-Данченко, Москва

В 1969 году Юрий Григорович создал свою версию «Лебединого озера». Он в спектакле Большого театра сохранил фрагменты Петипа, Иванова и Горского. Но не смог поставить желанный трагический финал: от него — по идеологическим причинам — потребовали хеппи-энда. Лишь много лет спустя хореограф осуществил изначальный замысел. Григорович мыслил мотивом двойников: Злой гений стал вторым «я» положительного героя, маячащим у принца за спиной.

20 декабря 1984 года Рудольф Нуреев поставил собственную версию балета в Париже. Во многом перекроил балет под себя, добавив Принцу много танцев, сосредоточив внимание именно на нем, а не на балерине, как традиционно было ранее. Хореограф, продолжая поиски ленинградских редакторов балета, увлекся идеей, которая в конце XX века стала особенно популярной: принц — чужой в своей семье и никому не нужный, мается во дворце, давая волю воображению и уходя в свои внутренние миры.

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Тамара Карсавина в роли Одетты. 1-я четверть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Галина Уланова в роли Одетты и Константин Сергеев в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург / Фотография Евгения Рагузина

Балет Петр Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Михаил Габович в роли Зигфрида. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Алла Шелест в роли Одиллии. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Анна Павлова в роли Одетты. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

Балет Петра Чайковского «Лебединое озеро». Галина Уланова в роли Одетты. 2-я треть XX века

Государственный мемориальный музыкальный музей-заповедник П.И. Чайковского, Клин, Московская область

В конце XX века на мировых сценах появились разные версии «Лебединого озера», не связанные ни с классическим танцем, ни с прежней постановочной традицией. В поисках новых смыслов хореографы отказывались от традиционного сюжета. Волшебная сказка становилась отправной точкой для разного рода рефлексий на жгучие проблемы современности. Балет нередко ставился с помощью разных техник танца-модерн и так называемого «актуального танца».

|

Джон Ноймайер в 1976 году в Балете Гамбурга сделал героем того самого баварского короля Людвига Второго, замок которого вдохновил Чайковского. Балет «Иллюзии как «Лебединое озеро», навеянный фильмом Лукино Висконти «Людвиг», повествовал о безумии венценосца, погруженного в эстетские грезы. |

Балет «Иллюзии как «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Джон Ноймайер

Гамбургский балет, Германия, 1976 год

Балет «Иллюзии как «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Джон Ноймайер

Гамбургский балет, Германия, 1976 год

Швед Матс Эк в своем «Лебедином озере» 1987 года искусно смешал черное и белое. Одиллия притворяется Одеттой, а злая женщина — злым волшебником. Принц становится жертвой клановых козней, история деспотичной матери, не дающей житья застенчивому ребенку, перерастает в гротескную психоаналитическую драму, а к эпатажному облику и пластике лысых лебедей-андрогинов публике в свое время пришлось привыкать.

Швед Матс Эк в своем «Лебедином озере» 1987 года искусно смешал черное и белое. Одиллия притворяется Одеттой, а злая женщина — злым волшебником. Принц становится жертвой клановых козней, история деспотичной матери, не дающей житья застенчивому ребенку, перерастает в гротескную психоаналитическую драму, а к эпатажному облику и пластике лысых лебедей-андрогинов публике в свое время пришлось привыкать.

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Матс Эк

Кульберг-балет, Швеция, 1987 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Матс Эк

Кульберг-балет, Швеция, 1987 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Матс Эк

Кульберг-балет, Швеция, 1987 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Матс Эк

Кульберг-балет, Швеция, 1987 год

Британский постановщик Мэтью Борн известен балетом, в котором все лебеди — мужчины. Но сделано это не для эпатажа. «Лебединое озеро» 1995 года — гуманистический и светлый спектакль с полностью оригинальной хореографией. Действие происходит в наши дни, а в визуальных реалиях балета многие узнали Великобританию. Это притча об одиночестве и о том, что против стаи идти невозможно и опасно, будь ты птица, обычный человек или особа королевских кровей.

Британский постановщик Мэтью Борн известен балетом, в котором все лебеди — мужчины. Но сделано это не для эпатажа. «Лебединое озеро» 1995 года — гуманистический и светлый спектакль с полностью оригинальной хореографией. Действие происходит в наши дни, а в визуальных реалиях балета многие узнали Великобританию. Это притча об одиночестве и о том, что против стаи идти невозможно и опасно, будь ты птица, обычный человек или особа королевских кровей.

В Балете Монте-Карло поставлен своеобразный по замыслу и пластике спектакль «Озеро» в хореографии Жана Кристофа Майо (премьера состоялась в декабре 2011 года). Вместо водоема здесь скалы, взамен Злого гения орудует Царица ночи, мстящая семье Принца и гипнотизирующая его. История принца — драматическая реализация его детских страхов, «борьба животных эротических инстинктов ночи против чистоты дневного света.

Хореограф Грэм Мерфи, как и Майо, вольно отнесся к партитуре Чайковского, когда в 2002 ставил балет, в котором находят намеки на конфликт между британским принцем Чарльзом и принцессой Дианой. По версии спектакля в Австралийском балете, Одетта вынуждена делить своего любимого с некоей баронессой фон Ротбарт, отчего нежная девушка попадает в сумасшедший дом.

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Грэм Мерфи

Австралийский балет, Сидней, Австралия, 2002 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Грэм Мерфи

Австралийский балет, Сидней, Австралия, 2002 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Грэм Мерфи

Австралийский балет, Сидней, Австралия, 2002 год

Балет «Лебединое озеро». Хореограф Грэм Мерфи

Австралийский балет, Сидней, Австралия, 2002 год

Приступая к авторскому «Лебединому озеру» в 2013 году, хореограф Раду Поклитару, артисты которого танцуют без пуантов, изменил главную коллизию балета — превращение девушки в лебедя. У него, наоборот, лебедь насильственно (как жертва научного эксперимента) становится мальчиком по имени Зигфрид. Одетта в этих условиях — светлая мечта несчастной жертвы науки, а грубая Одиллия — его реальность.

Приступая к авторскому «Лебединому озеру» в 2013 году, хореограф Раду Поклитару, артисты которого танцуют без пуантов, изменил главную коллизию балета — превращение девушки в лебедя. У него, наоборот, лебедь насильственно (как жертва научного эксперимента) становится мальчиком по имени Зигфрид. Одетта в этих условиях — светлая мечта несчастной жертвы науки, а грубая Одиллия — его реальность.

Александр Пепеляев в своей радикальной версии 2003 года исследовал, по его словам, социально-общественный статус самого популярного классического спектакля. Пластика возникает в куче железных бочек, ведер с жидкостью взамен озера, точечных фрагментов партитуры, пародии на геометрию построений классического кордебалета (и на физкультурный парад сталинских времен) и портретов Чайковского бородой вверх.

Одна из последних версий — «Лебединое озеро» 2014 года в Норвежском балете. Ее автор Александр Экман воспроизвел на сцене историю первой постановки балета в России (с драматическими актерами и словесным текстом) и создал на сцене настоящее озеро, для чего понадобилось 6000 литров воды. Кульминация — драка Черного и Белого лебедя в изысканных дизайнерских костюмах.

В последние годы наряду с постановочным радикализмом набирает силу противоположное, реставрационное направление, когда современные хореографы пытаются восстановить сценический облик первых представлений балета. В 2016 году одну из ретроверсий предложил Алексей Ратманский. Была сделана попытка не только восстановить утраченные или переделанные эпизоды «Лебединого озера», но и, по возможности, музыку, костюмы, даже грим. На свое место вернулись объемная пантомима, старинный крой балетных пачек и черные лебеди в кордебалете последнего акта. Был подхвачен подлинный стиль исполнения балета а-ля «сто лет назад», подлинная манера движений.

«Лебединое озеро» выдержало проверку временем. Этот балет, вечно востребованный, вечно изменчивый и вечно прекрасный, и есть само время. Музыка Чайковского, как и метафорическая схватка добра и зла — не только приманка для широкой публики, но и объект пристального интереса историков искусства: о балете написаны тома. Это социальный феномен, вышедший далеко за рамки чистой театральности. Символ и модель. Образец для восторженного подражания и предмет авангардного оспаривания. Неслучайно замечено, что «Лебединое озеро» для балета — то же самое, что чеховская «Чайка» для драматического театра. И великая гуманистическая идея: любовь сильнее смерти.

Юные воспитанницы Санкт-Петербургской академии танца Бориса Эйфмана рассказывают о своем восприятии балета «Лебединое озеро».

«Для меня возможность станцевать в «Лебедином озере» — это шанс показать себя с двух совершенно разных сторон: со стороны Одетты — романтичной, мечтательной, искренней, верящей в любовь девушки. И раскрыть в себе характер Одилии — коварной красавицы. Только самая достойная балерина способна рассказать зрителю эту волшебную историю любви».

воспитанница 4/8 Б класса Санкт-Петербургской

академии танца Бориса Эйфмана

«Балет — это как формула, когда без одного показателя уравнение не решится. Формула проста: труд плюс желание плюс педагог равно результат. Возможность выступать получает тот, кто заслужил своим трудом и своим желанием танцевать».

воспитанница 2/6 класса Санкт-Петербургской

академии танца Бориса Эйфмана

«Возможность выйти на сцену в «Лебедином озере» для меня будет значить, что я достигла не только технических высот, но и созрела эмоционально для выражения всех чувств, которые должна показать балерина как в партии Одетты, так и в партии Одилии».

воспитанница 3/7 класса Санкт-Петербургской

академии танца Бориса Эйфмана

«Это сложный, противоречивый балет с тяжелой технической и физической работой. Танцевать «Лебединое озеро» — значит уметь искусно перевоплощаться и иметь безупречное техническое мастерство. Пример для меня — Майя Плисецкая, которая никогда никого не копировала и имела свой собственный артистический почерк».

воспитанница 1/5 А класса Санкт-Петербургской

академии танца Бориса Эйфмана

«Станцевать в «Лебедином озере» — это мечта любого человека, решившего посвятить свою жизнь балету. «Лебединое озеро» — прекрасная классика, которая не выйдет из моды, не забудется. Это то, что люди узнавали, узнают и будут узнавать по всему миру».

воспитанница 4/8 А класса Санкт-Петербургской

академии танца Бориса Эйфмана

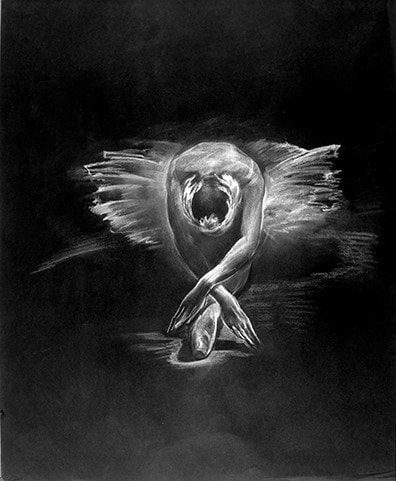

Главная фотография: балет «Лебединое озеро».

Хореограф Грэм Мерфи. Австралийский балет. 2002 год

Фотографии предоставлены

Государственным мемориальным музыкальным музеем-заповедником П.И. Чайковского

и Государственным академическим Мариинским театром

С юными балеринами беседовала Людмила Котлярова

Верстка: Кристина Мацевич

| Swan Lake | |

|---|---|

| Choreographer | Julius Reisinger |

| Music | Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky |

| Premiere | 4 March [O.S. 20 February] 1877 Moscow |

| Original ballet company | Bolshoi Ballet |

| Genre | Classical ballet |

Swan Lake (Russian: Лебеди́ное о́зеро, tr. Lebedínoye ózero, IPA: [lʲɪbʲɪˈdʲinəjə ˈozʲɪrə] listen (help·info)), Op. 20, is a ballet composed by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1875–76. Despite its initial failure, it is now one of the most popular ballets of all time.[1]

The scenario, initially in two acts, was fashioned from Russian and German folk tales and tells the story of Odette, a princess turned into a swan by an evil sorcerer’s curse. The choreographer of the original production was Julius Reisinger (Václav Reisinger). The ballet was premiered by the Bolshoi Ballet on 4 March [O.S. 20 February] 1877[2][3] at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Although it is presented in many different versions, most ballet companies base their stagings both choreographically and musically on the 1895 revival of Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, first staged for the Imperial Ballet on 15 January 1895, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. For this revival, Tchaikovsky’s score was revised by the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatre’s chief conductor and composer Riccardo Drigo.[4]

History[edit]

Design by F. Gaanen for the décor of act 2, Moscow 1877

Origins of the ballet[edit]

There is no evidence to prove who wrote the original libretto, or where the idea for the plot came from. Russian and German folk tales have been proposed as possible sources, including «The Stolen Veil» by Johann Karl August Musäus, but both those tales differ significantly from the ballet.[5]

One theory is that the original choreographer, Julius Reisinger, who was a Bohemian (and therefore likely to be familiar with The Stolen Veil), created the story.[6] Another theory is that it was written by Vladimir Petrovich Begichev, director of the Moscow Imperial Theatres at the time, possibly with Vasily Geltser, danseur of the Moscow Imperial Bolshoi Theatre (a surviving copy of the libretto bears his name). Since the first published libretto does not correspond with Tchaikovsky’s music in many places, one theory is that the first published version was written by a journalist after viewing initial rehearsals (new opera and ballet productions were always reported in the newspapers, along with their respective scenarios).

Some contemporaries of Tchaikovsky recalled the composer taking great interest in the life story of Bavarian King Ludwig II, whose life had supposedly been marked by the sign of Swan and could have been the prototype of the dreamer Prince Siegfried.[7]

Begichev commissioned the score of Swan Lake from Tchaikovsky in May 1875 for 800 rubles. Tchaikovsky worked with only a basic outline from Julius Reisinger of the requirements for each dance.[8] However, unlike the instructions for the scores of The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, no written instruction is known to have survived.

Tchaikovsky’s influences[edit]

From around the time of the turn of the 19th century until the beginning of the 1890s, scores for ballets were almost always written by composers known as «specialists» who were highly skilled at scoring the light, decorative, melodious, and rhythmically clear music that was at that time in vogue for ballet. Tchaikovsky studied the music of «specialists» such as the Italian Cesare Pugni and the Austrian Ludwig Minkus, before setting to work on Swan Lake.

Tchaikovsky had a rather negative opinion of the «specialist» ballet music until he studied it in detail, being impressed by the nearly limitless variety of infectious melodies their scores contained. Tchaikovsky most admired the ballet music of such composers as Léo Delibes, Adolphe Adam, and later, Riccardo Drigo. He would later write to his protégé, the composer Sergei Taneyev, «I listened to the Delibes ballet Sylvia … what charm, what elegance, what wealth of melody, rhythm, and harmony. I was ashamed, for if I had known of this music then, I would not have written Swan Lake.» Tchaikovsky most admired Adam’s 1844 score for Giselle, which used the Leitmotif technique: associating certain themes with certain characters or moods, a technique he would use in Swan Lake, and later, The Sleeping Beauty.

Tchaikovsky drew on previous compositions for his Swan Lake score. According to two of Tchaikovsky’s relatives – his nephew Yuri Lvovich Davydov and his niece Anna Meck-Davydova – the composer had earlier created a little ballet called The Lake of the Swans at their home in 1871. This ballet included the famous Leitmotif, the Swan’s Theme or Song of the Swans. He also made use of material from The Voyevoda, an opera he had abandoned in 1868. Another number which included a theme from The Voyevoda was the Entr’acte of the fourth scene and the opening of the Finale (Act IV, No. 29). The Grand adage (a.k.a. the Love Duet) from the second scene of Swan Lake was fashioned from the final love duet from his opera Undina (Tchaikovsky), abandoned in 1873.

By April 1876 the score was complete, and rehearsals began. Soon Reisinger began setting certain numbers aside that he dubbed «undanceable.» Reisinger even began choreographing dances to other composers’ music, but Tchaikovsky protested and his pieces were reinstated. Although the two artists were required to collaborate, each seemed to prefer working as independently of the other as possible.[9]

Composition process[edit]

Tchaikovsky’s excitement with Swan Lake is evident from the speed with which he composed: commissioned in the spring of 1875, the piece was created within one year. His letters to Sergei Taneyev from August 1875 indicate, however, that it was not only his excitement that compelled him to create it so quickly but his wish to finish it as soon as possible, so as to allow him to start on an opera. Respectively, he created scores of the first three numbers of the ballet, then the orchestration in the fall and winter, and was still struggling with the instrumentation in the spring. By April 1876, the work was complete. Tchaikovsky’s mention of a draft suggests the presence of some sort of abstract but no such draft has ever been seen. Tchaikovsky wrote various letters to friends expressing his longstanding desire to work with this type of music, and his excitement concerning his current stimulating, albeit laborious task.[10]

Performance history[edit]

Moscow première (world première)

- Date: 4 March (OS 20 February) 1877

- Place: Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow

- Balletmaster: Julius Reisinger

- Conductor: Stepan Ryabov

- Scene Designers: Karl Valts (acts 2 & 4), Ivan Shangin (act 1), Karl Groppius (act 3)

St. Petersburg première

- Date: 27 January 1895

- Place: Mariinsky Theatre, St. Petersburg

- Balletmaster: Marius Petipa (acts 1 & 3), Lev Ivanov (acts 2 & 4)

- Conductor: Riccardo Drigo

- Scene Designers: Ivan Andreyev, Mikhail Bocharov, Henrich Levogt

- Costume Designer: Yevgeni Ponomaryov[11]

Other notable productions

- 1880 and 1882, Moscow, Bolshoi Theatre, staged by Joseph Hansen after Reisinger, conductor and designers as in première

- 1901, Moscow, Bolshoi Theatre, staged by Aleksandr Gorsky, conducted by Andrey Arends, scenes by Aleksandr Golovin (act 1), Konstantin Korovin (acts 2 & 4), N. Klodt (act 3)

- 1911, London, Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev production, choreography by Michel Fokine after Petipa–Ivanov, scenes by Golovin and Korovin

Original interpreters

| Role | Moscow 1877 | Moscow 1880 | St. Petersburg 1895[11] | Moscow 1901 | London 1911 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen | Olga Nikolayeva | Giuseppina Cecchetti | |||

| Siegfried | Victor Gillert | Alfred Bekefi | Pavel Gerdt | Mikhail Mordkin | Vaslav Nijinsky |

| Benno | Sergey Nikitin | Aleksandr Oblakov | |||

| Wolfgang | Wilhelm Wanner | Gillert | |||

| Odette | Pelageya Karpakova | Yevdokiya Kalmїkova | Pierina Legnani | Adelaide Giuri | Mathilde Kschessinska |

| Von Rothbart | Sergey Sokolov | Aleksey Bulgakov | K. Kubakin | ||

| Odile | Pelageya Karpakova | Pierina Legnani | Mathilde Kschessinska |

Original production of 1877[edit]

The première on Friday, 4 March 1877, was given as a benefit performance for the ballerina Pelageya Karpakova (also known as Polina Karpakova), who performed the role of Odette, with première danseur Victor Gillert as Prince Siegfried. Karpakova may also have danced the part Odile, although it is believed the ballet originally called for two different dancers. It is now common practice for the same ballerina to dance both Odette and Odile.

The Russian ballerina Anna Sobeshchanskaya was originally cast as Odette, but was replaced when a governing official in Moscow complained about her, claiming she had accepted jewelry from him, only to then marry a fellow danseur and sell the pieces for cash.

The première was not well received. Though there were a few critics who recognised the virtues of the score, most considered it to be far too complicated for ballet. It was labelled «too noisy, too ‘Wagnerian’ and too symphonic.»[12] The critics also thought Reisinger’s choreography was «unimaginative and altogether unmemorable.»[12] The German origins of the story were «treated with suspicion while the tale itself was regarded as ‘stupid’ with unpronounceable surnames for its characters.»[12] Karpakova was a secondary soloist and «not particularly convincing.»[12]

The poverty of the production, meaning the décor and costumes, the absence of outstanding performers, the Balletmaster’s weakness of imagination, and, finally, the orchestra … all of this together permitted (Tchaikovsky) with good reason to cast the blame for the failure on others.

Yet the fact remains (and is too often omitted in accounts of this initial production) that this staging survived for six years with a total of 41 performances – many more than several other ballets from the repertoire of this theatre.[13]

Tchaikovsky pas de deux 1877[edit]

On 26 April 1877, Anna Sobeshchanskaya made her début as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake, and from the start, she was completely dissatisfied with the ballet. Sobeshchanskaya asked Marius Petipa—Premier Maître de Ballet of the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres—to choreograph a pas de deux to replace the pas de six in the third act (for a ballerina to request a supplemental pas or variation was standard practice in 19th-century ballet, and often these «custom-made» dances were the legal property of the ballerina they were composed for).

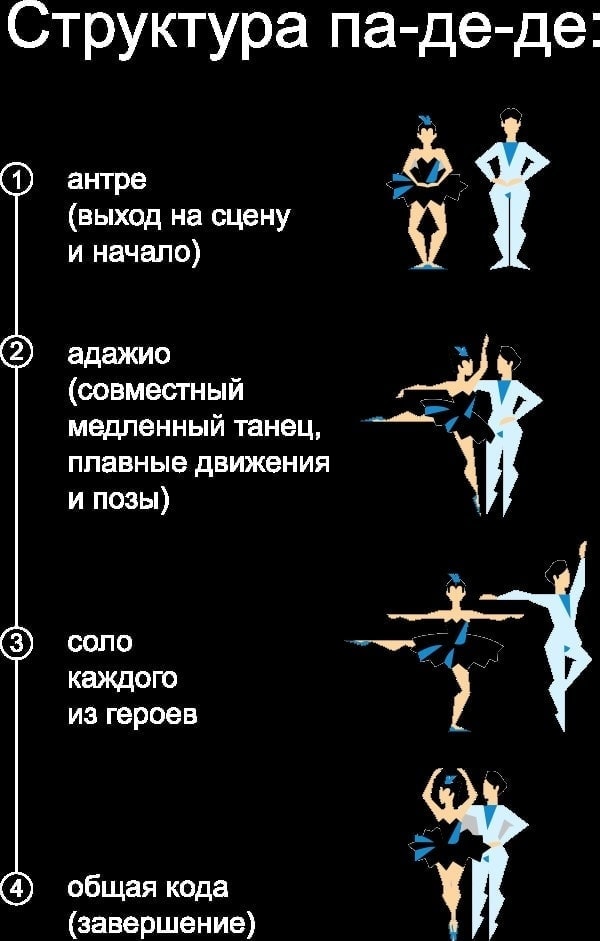

Petipa created the pas de deux to music by Ludwig Minkus, ballet composer to the St Petersburg Imperial Theatres. The piece was a standard pas de deux classique consisting of a short entrée, the grand adage, a variation for each dancer individually, and a coda.

Tchaikovsky was angered by this change, stating that whether the ballet was good or bad, he alone should be held responsible for its music. He agreed to compose a new pas de deux, but soon a problem arose: Sobeshchanskaya wanted to retain Petipa’s choreography. Tchaikovsky agreed to compose a pas de deux that would match to such a degree, the ballerina would not even be required to rehearse. Sobeshchanskaya was so pleased with Tchaikovsky’s new music, she requested he compose an additional variation, which he did.

Until 1953 this pas de deux was thought to be lost, until a repétiteur score was accidentally found in the archives of the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre, among orchestral parts for Alexander Gorsky’s revival of Le Corsaire (Gorsky had included the piece in his version of Le Corsaire staged in 1912). In 1960 George Balanchine choreographed a pas de deux to this music for Violette Verdy and Conrad Ludlow, performed at the City Center of Music and Drama in New York City as Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux,[14] as it is still known and performed today.

Subsequent productions 1879–1894[edit]

Julius Reisinger’s successor as balletmaster was Joseph Peter Hansen. Hansen made considerable efforts to salvage Swan Lake and on 13 January 1880 he presented a new production of the ballet for his own benefit performance. The part of Odette/Odile was danced by Evdokia Kalmykova, a student of the Moscow Imperial Ballet School, with Alfred Bekefi as Prince Siegfried. This production was better received than the original, but by no means a great success. Hansen presented another version of Swan Lake on 28 October 1882, again with Kalmykova as Odette/Odile. For this production Hansen arranged a Grand Pas for the ballroom scene which he titled La Cosmopolitana. This was taken from the European section of the Grand Pas d’action known as The Allegory of the Continents from Marius Petipa’s 1875 ballet The Bandits to the music of Ludwig Minkus. Hansen’s version of Swan Lake was given only four times, the final performance being on 2 January 1883, and soon the ballet was dropped from the repertory altogether.

In all, Swan Lake was performed 41 times between its première and the final performance of 1883 – a rather lengthy run for a ballet that was so poorly received upon its première. Hansen became Balletmaster to the Alhambra Theatre in London and on 1 December 1884 he presented a one-act ballet titled The Swans, which was inspired by the second scene of Swan Lake. The music was composed by the Alhambra Theatre’s chef d’orchestre Georges Jacoby.

The second scene of Swan Lake was then presented on 21 February in Prague by the Ballet of the National Theatre in a version mounted by the Balletmaster August Berger. The ballet was given during two concerts which were conducted by Tchaikovsky. The composer noted in his diary that he experienced «a moment of absolute happiness» when the ballet was performed. Berger’s production followed the 1877 libretto, though the names of Prince Siegfried and Benno were changed to Jaroslav and Zdeňek, with the rôle of Benno danced by a female dancer en travestie. The rôle of Prince Siegfried was danced by Berger himself with the ballerina Giulietta Paltriniera-Bergrova as Odette. Berger’s production was only given eight performances and was even planned for production at the Fantasia Garden in Moscow in 1893, but it never materialised.

Petipa–Ivanov–Drigo revival of 1895[edit]

During the late 1880s and early 1890s, Petipa and Vsevolozhsky discussed with Tchaikovsky the possibility of reviving Swan Lake.[15] However, Tchaikovsky died on 6 November 1893,[16] just when plans to revive Swan Lake were beginning to come to fruition. It remains uncertain whether Tchaikovsky was prepared to revise the music for this revival. Whatever the case, as a result of Tchaikovsky’s death, Drigo was forced to revise the score himself, after receiving approval from Tchaikovsky’s younger brother, Modest. There are major differences between Drigo’s and Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake score. Today, it is Riccardo Drigo’s revision of Tchaikovsky’s score, and not Tchaikovsky’s original score of 1877, that most ballet companies use.

Pavel Gerdt as Prince Siegfried (Mariinsky Theatre, 1895)

In February 1894, two memorial concerts planned by Vsevolozhsky were given in honor of Tchaikovsky. The production included the second act of Swan Lake, choreographed by Lev Ivanov, Second Balletmaster to the Imperial Ballet. Ivanov’s choreography for the memorial concert was unanimously hailed as wonderful.

The revival of Swan Lake was planned for Pierina Legnani’s benefit performance in the 1894–1895 season. The death of Tsar Alexander III on 1 November 1894 and the ensuing period of official mourning brought all ballet performances and rehearsals to a close for some time, and as a result all efforts could be concentrated on the pre-production of the full revival of Swan Lake. Ivanov and Petipa collaborated on the production, with Ivanov retaining his dances for the second act while choreographing the fourth, with Petipa staging the first and third acts.

Modest Tchaikovsky was called upon to make changes to the ballet’s libretto, including the character of Odette changing from a fairy swan-maiden into a cursed mortal woman, the ballet’s villain changing from Odette’s stepmother to the magician von Rothbart, and the ballet’s finale: instead of the lovers simply drowning at the hand of Odette’s stepmother as in the original 1877 scenario, Odette commits suicide by drowning herself, with Prince Siegfried choosing to die as well, rather than live without her, and soon the lovers’ spirits are reunited in an apotheosis.[17] Aside from the revision of the libretto the ballet was changed from four acts to three—with act 2 becoming act 1, scene 2.

All was ready by the beginning of 1895 and the ballet had its première on Friday, 27 January. Pierina Legnani danced Odette/Odile, with Pavel Gerdt as Prince Siegfried, Alexei Bulgakov as Rothbart, and Alexander Oblakov as Benno. Most of the reviews in the St. Petersburg newspapers were positive.

Unlike the première of The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake did not dominate the repertory of the Mariinsky Theatre in its first season. It was given only sixteen performances between the première and the 1895–1896 season, and was not performed at all in 1897. Even more surprising, the ballet was performed only four times in 1898 and 1899. The ballet belonged solely to Legnani until she left St. Petersburg for her native Italy in 1901. After her departure, the ballet was taken over by Mathilde Kschessinskaya, who was as much celebrated in the rôle as was her Italian predecessor.

Later productions[edit]

Throughout the performance history of Swan Lake, the 1895 edition has served as the version on which most stagings have been based. Nearly every balletmaster or choreographer who has re-staged Swan Lake has made modifications to the ballet’s scenario, while still maintaining much of the traditional choreography for the dances, which is regarded as virtually sacrosanct. Likewise, over time the rôle of Siegfried has become more prominent, due largely to the evolution of ballet technique.

In 1922, Finnish National Ballet was the first European company that staged a complete production of the ballet. By the time Swan Lake premiered in Helsinki Finland in 1922, it had only ever been performed by Russian and Czech ballet groups, and only visiting Russian ballet groups had brought it to Western Europe.[18]

In 1940, San Francisco Ballet became the first American company to stage a complete production of Swan Lake. The enormously successful production starred Lew Christensen as Prince Siegfried, Jacqueline Martin as Odette, and Janet Reed as Odile. Willam Christensen based his choreography on the Petipa–Ivanov production, turning to San Francisco’s large population of Russian émigrés, headed by Princess and Prince Vasili Alexandrovich of Russia, to help him ensure that the production succeeded in its goal of preserving Russian culture in San Francisco.[19]

Several notable productions have diverged from the original and its 1895 revival:

- In 1967, Eric Bruhn produced and danced in a new «Swan Lake» for the National Ballet of Canada, with striking largely black and white designs by Desmond Healey. Although substantial portions of the Petipa-Ivanov choreography were retained, Bruhn’s alterations were musical as well as choreographic. Most controversially, he recast Von Rothbart as the malevolent «Black Queen», adding psychological emphasis to the Prince’s difficult relationships with women, his domineering mother included.

- Illusions Like «Swan Lake» 1976: John Neumeier Hamburg Ballet, Neumeier interpolated the story of Ludwig II of Bavaria into the Swan Lake plot, via Ludwig’s fascination with swans. Much of the original score was used with additional Tchaikovsky material and the choreography combined the familiar Petipa/Ivanov material with new dances and scenes by Neumeier. The ballet finishes with Ludwig’s death by drowning while confined to an asylum, set to the dramatic music for the act 3 conclusion. With the theme of the unhappy royal being forced into heterosexual marriage for reasons of state and also the cross reference to the personal lives of actual royalty, this work anticipated both Bourne’s and Murphy’s interpretation. Illusions Like «Swan Lake» remains in the repertoire of major German ballet companies.

- Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake departed from the traditional ballet by replacing the female corps de ballet with male dancers and a plot focused on the psychological pressures of modern royalty on a prince struggling with his sexuality and a distant mother. It has been performed on extended tours in Greece, Israel, Turkey, Australia, Italy, Japan, Korea, Russia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, and Ireland in addition to the United Kingdom, and has won over 30 international awards to date.[20]

- The 2000 American Ballet Theatre version (taped for television in 2005), rather than having the curtain down as the slow introduction is played, used this music to accompany a new prologue in which the audience is shown how Rothbart first transforms Odette into a swan. This prologue is similar to Vladimir Burmeister’s production of «Swan Lake» (firstly staged in Stanislavsky Theatre in Moscow, 1953) but has some differences. Rothbart in this production is played by two dancers; one appears as a handsome young man who is easily able to lure Odette in the new prologue, and the other dancer is covered in sinister «monster makeup» which reveals the magician’s true self. (in the film Black Swan, Natalie Portman, as Nina, dreams this in the film’s opening sequence). About half-an-hour of the complete score is omitted from this production.[citation needed]

- Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake was first performed in 2002, and was loosely based on the breakdown of the marriage of Lady Diana to Prince Charles and his relationship with Camilla Parker Bowles. It combined the rôles of Rothbart and Odile into that of a Baroness, and the focus of the story is a love triangle.[21]

- In 2010, Black Swan, a film starring Natalie Portman and Mila Kunis, contained sequences from Swan Lake.[22]

- In 2010, South African choreographer and ballet dancer Dada Masilo, remade Tchaikovsky’s classic.[23] Her version was a mix of classic ballet and African dance. She also made a plot twist by presenting Odile (the black swan) as a gay male swan rather than a female swan.[24][25]

- A Swan Lake, choreographed by Alexander Ekman and composed by Mikael Karlsson, was created for the Norwegian National Ballet. The first act is part dance part theatre, about the original production of Swan Lake, which features two stage actors and a soprano. In the second act, the stage is filled in 5000 litres of water, and features the conflict between White Swan and Black Swan.[26][27]

Instrumentation[edit]

Swan Lake is scored for the typical late 19th-century large orchestra:

- Strings: violins I and II; violas, violoncellos; double basses, harp

- Woodwinds: piccolo; 2 flutes; 2 oboes; 2 clarinets in B♭, A and C; 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 French horns in F; 2 cornets in A and B♭; 2 trumpets in F, D, and E; 3 trombones (2 tenor, 1 bass); tuba

- Percussion: timpani; snare drum; cymbals; bass drum; triangle; tambourine; castanets; tam-tam; glockenspiel; chimes

Roles[edit]

- Princess Odette (the Swan Queen, the White Swan, the Swan Princess), a beautiful princess, who has been transformed into a white swan

- Prince Siegfried, a handsome Prince who falls in love with Odette

- Baron Von Rothbart, an evil sorcerer, who has enchanted Odette

- Odile (the Black Swan), Rothbart’s daughter

- Benno von Sommerstern, the Prince’s friend

- The Queen, Prince Siegfried’s mother

- Wolfgang, his tutor

- Baron von Stein

- The Baroness, his wife

- Freiherr von Schwarzfels

- His wife

- A herald

- A footman

- Court gentlemen and ladies, friends of the prince, heralds, guests, pages, villagers, servants, swans, cygnets

Variations to characters[edit]

By 1895, Benno von Sommerstern had become just «Benno», and Odette «Queen of the Swans.» Also Baron von Stein, his wife, and Freiherr von Schwarzfels and his wife were no longer identified on the program. The sovereign or ruling Princess is often rendered «Queen Mother.»

The character of Rothbart (sometimes spelled Rotbart) has been open to many interpretations. The reason for his curse upon Odette is unknown; several versions, including two feature films, have suggested reasons, but none is typically explained by the ballet. He is rarely portrayed in human form, except in act 3. He is usually shown as an owl-like creature. In most productions, the couple’s sacrifice results in his destruction. However, there are versions in which he is triumphant. Yury Grigorovich’s version, which has been danced for several decades by the Bolshoi Ballet, is noted for including both endings: Rothbart was defeated in the original 1969 version, in line with Soviet-era expectations of an upbeat conclusion,[28] but in the 2001 revision, Rothbart plays a wicked game of fate with Siegfried, which he wins at the end, causing Siegfried to lose everything. In the second American Ballet Theatre production of Swan Lake, he is portrayed by two dancers: a young, handsome one who lures Odette to her doom in the prologue, and a reptilian creature. In this version, the lovers’ suicide inspires the rest of Rothbart’s imprisoned swans to turn on him and overcome his spell.

Odile, Rothbart’s daughter usually wears jet black (though in the 1895 production, she did not), and appears only in act 3. In most modern productions, she is portrayed as Odette’s exact double (though the resemblance is because of Rothbart’s magic), and therefore Siegfried cannot be blamed for believing her to be Odette. There is a suggestion that in the original production, Odette and Odile were danced by two different ballerinas. This is also the case in some avant garde productions.

Synopsis[edit]

Swan Lake is generally presented in either four acts, four scenes (primarily outside Russia and Eastern Europe) or three acts, four scenes (primarily in Russia and Eastern Europe). The biggest difference of productions all over the world is that the ending, originally tragic, is now sometimes altered to a happy ending.

Prologue[edit]

Some productions include a prologue that shows how Odette first meets Rothbart, who turns Odette into a swan.

Act 1[edit]

A magnificent park before a palace

[Scène: Allegro giusto] Prince Siegfried is celebrating his birthday with his tutor, friends, and peasants [Waltz]. The revelries are interrupted by his mother, the Queen [Scène: Allegro moderato], who is concerned about his carefree lifestyle. She tells him that he must choose a bride at the royal ball the following evening (some productions include the presentation of some possible candidates). He is upset that he can’t marry for love. His friend, Benno, and the tutor try to lift his troubled mood. As evening falls [Sujet], Benno sees a flock of swans flying overhead and suggests they go on a hunt [Finale I]. Siegfried and his friends take their crossbows and set off in pursuit of the swans.

Act 2[edit]

A lakeside clearing in a forest by the ruins of a chapel. A moonlit night.

The «Valse des cygnes» from act 2 of the Ivanov/Petipa edition of Swan Lake

Siegfried has become separated from his friends. He arrives at the lakeside clearing, just as a flock of swans land [Scène. Moderato]. He aims his crossbow [Scène. Allegro moderato], but freezes when one of them transforms into a beautiful maiden named Odette [Scène. Moderato]. At first, she is terrified of him. When he promises not to harm her, she explains that she and her companions are victims of a spell cast by the evil owl-like sorcerer named Rothbart. By day they are turned into swans and only at night, by the side of the enchanted lake – created from the tears of Odette’s mother – do they return to human form. The spell can only be broken if one who has never loved before swears to love Odette forever. Rothbart suddenly appears [Scène. Allegro vivo]. Siegfried threatens to kill him but Odette intercedes – if he dies before the spell is broken, it can never be undone.

As Rothbart disappears, the swan maidens fill the clearing [Scène: Allegro, Moderato assai quasi andante]. Siegfried breaks his crossbow, and sets about winning Odette’s trust as they fall in love. But as dawn arrives, the evil spell draws Odette and her companions back to the lake and they are turned into swans again.

Act 3[edit]

An opulent hall in the palace

Guests arrive at the palace for a costume ball. Six princesses are presented to the prince [Entrance of the Guests and Waltz], as candidates for marriage. Rothbart arrives in disguise [Scène: Allegro, Allegro giusto] with his daughter, Odile, who is transformed to look like Odette. Though the princesses try to attract Siegfried with their dances [Pas de six], he has eyes only for Odile. [Scène: Allegro, Tempo di valse, Allegro vivo] Odette appears at the castle window and attempts to warn him, but he does not see her. He then proclaims to the court that he will marry Odile before Rothbart shows him a magical vision of Odette. Grief-stricken and realizing his mistake (he vowed only to love Odette), he hurries back to the lake.

Act 4[edit]

By the lakeside

Odette is distraught. The swan maidens try to comfort her. Siegfried returns to the lake and makes a passionate apology. She forgives him, but his betrayal can’t be undone. Rather than remain a swan forever, she chooses to die. He chooses to die with her and they leap into the lake, where they will stay together forever. This breaks Rothbart’s spell over the swan maidens, causing him to lose his power over them and he dies. In an apotheosis, they, who transform back into regular maidens, watch as Siegfried and Odette ascend into the Heavens together, forever united in love.

1877 libretto synopsis[edit]

Act 1

Prince Siegfried, his friends, and a group of peasants are celebrating his coming of age. His mother arrives to inform him she wishes for him to marry soon so she may make sure he does not disgrace their family line by his marriage. She has organized a ball where he is to choose his bride from among the daughters of the nobility. After the celebration, he and his friend, Benno, spot a flock of flying swans and decide to hunt them.

Act 2

Siegfried and Benno track the swans to a lake, but they vanish. A woman wearing a crown appears and meets them. She tells them her name is Odette and she was one of the swans they were hunting. She tells them her story: her mother, a good fairy, had married a knight, but she died and he remarried. Odette’s stepmother is a witch who wanted to kill her, but her grandfather saved her. He had cried so much over her mother’s death, he created the lake with his tears. She and her companions live in it with him, and can transform themselves into swans whenever they wish. Her stepmother still wants to kill her and stalks her in the form of an owl, but she has a crown which protects her from harm. When she gets married, her stepmother will lose the power to harm her. Siegfried falls in love with her but she fears her stepmother will ruin their happiness.

Act 3

Several young noblewomen dance at Siegfried’s ball, but he refuses to marry any of them. Baron von Rothbart and his daughter, Odile, arrive. Siegfried thinks Odile looks like Odette, but Benno doesn’t agree. He dances with her as he grows more and more enamored of her, and eventually agrees to marry her. At that moment, Rothbart transforms into a demon, Odile laughs, and a white swan wearing a crown appears in the window. Siegfried runs out of the castle.

Act 4

In tears, Odette tells her friends Siegfried did not keep his vow of love. Seeing him coming, they leave and urge her to go with them, but she wants to see him one last time. A storm begins. He enters and begs her for forgiveness. She refuses and attempts to leave. He snatches the crown from her head and throws it in the lake, saying, «Willing or unwilling, you will always remain with me!» The owl flies overhead, carrying the crown away. «What have you done? I am dying!» Odette says, and falls into his arms. The lake rises from the storm and drowns them. The storm quiets, and a group of swans appears on the lake.[29]

Alternative endings[edit]

Many different endings exist, ranging from romantic to tragic.

- In 1950, Konstantin Sergeyev staged a new Swan Lake for the Mariinsky Ballet (then the Kirov) after Petipa and Ivanov, but included some bits of Vaganova and Gorsky. Under the Soviet regime, the tragic ending was replaced with a happy one, so in the Mariinsky and Bolshoi versions, Odette and Siegfried lived happily ever after.

- In the version danced today by the Mariinsky Ballet, the ending is one of a «happily ever after» in which Siegfried fights Rothbart and tears off his wing, killing him. Odette is restored to human form and she and Siegfried are happily united. This version has often been used by Russian and Chinese ballet companies. A similar ending was used in The Swan Princess.

- In the 1986 version Rudolf Nureyev choreographed for the Paris Opera Ballet, Rothbart fights with Siegfried, who is overcome and dies, leaving Rothbart to take Odette triumphantly up to the Heavens.

- In the 1988 Dutch National Ballet production, choreographed by Rudi van Dantzig, Siegfried realized he can’t save Odette from the curse, so he drowns himself. His friend, Alexander, finds his body and carries him.[30]

- Although the 1969 Bolshoi Ballet production by Yuri Grigorovich contained a happy ending similar to the Mariinsky Ballet version, the 2001 revision changed the ending to a tragic one. Siegfried is defeated in a confrontation with the Evil Genius, who seizes Odette and takes her away to parts unknown before the lovers can unite, and Siegfried is left by himself at the lake. The major-key rendition of the main leitmotif and the remainder of the Apotheosis (retained in the 1969 production) are replaced with a modified, transposed repeat of the Introduction followed by the final few bars of No. 10/No. 14, closing the ballet on a downer.

- In a version which has an ending very close to the 1895 Mariinsky revival, danced by American Ballet Theatre starting in 2000 (with a video recording published in 2005), Siegfried’s mistaken pledge of fidelity to Odile consigns Odette to remain a swan forever. After realizing her last moment of humanity is at hand, Odette commits suicide by throwing herself into the lake. Siegfried follows her to his death. This act of sacrifice and love breaks Rothbart’s power, and he is destroyed. In the final tableau, the lovers are seen rising together to Heaven in apotheosis.

- In a version danced by New York City Ballet in 2006 (with choreography by Peter Martins after Lev Ivanov, Marius Petipa, and George Balanchine), Siegfried’s declaration he wishes to marry Odile constitutes a betrayal that condemns Odette to remain a swan forever. She is called away into swan form, and Siegfried is left alone in grief as the curtain falls.

- In the 2006 version by Stanton Welch for Houston Ballet, also based upon Petipa and Ivanov, the last scene has Siegfried attempting to kill Rothbart with his crossbow, but he misses and hits Odette instead. She falls, Rothbart’s spell now broken, and regains human form. Siegfried embraces her as she dies, then carries her body into the lake, where he also drowns himself.[31][32][33]

- In a version danced by San Francisco Ballet in 2009, Siegfried and Odette throw themselves into the lake, as in the 1895 Mariinsky revival, and Rothbart is destroyed. Two swans, implied to be the lovers, are then seen flying past the Moon.

- In a version danced by National Ballet of Canada in 2010, Odette forgives Siegfried for his betrayal and the promise of reconciliation shines momentarily before Rothbart summons forth a violent storm. He and Siegfried struggle. When the storm subsides, Odette is left alone to mourn the dead Siegfried.

- In the 2012 version performed at Blackpool Grand Theatre[34] by the Russian State Ballet of Siberia Siegfried drags Rothbart into the lake and they both drown. Odette is left as a swan.

- In the 2015 English National Ballet version My First Swan Lake,[35] specifically recreated for young children, the power of Siegfried and Odette’s love enables the other swans to rise up and defeat Rothbart, who falls to his death. This breaks the curse, and Siegfried and Odette live happily ever after. This is like the Mariinsky Ballet’s «Happily ever after» endings. In a new production in 2018, Odile helps Siegfried and Odette in the end. Rothbart, who is Odile’s brother in this production, is forgiven and he gives up his evil power. Odette and Siegfried live happily ever after and stay friends with Rothbart and Odile. This is actually the only production that grants a peaceful solution and a happily ever after even for Odile and Rothbart.

- In Hübbe and Schandorff’s 2015 and 2016 Royal Danish Ballet production, Siegfried is forced by Rothbart to marry Odile, after condemning Odette to her curse as a swan forever by mistakenly professing his love to Odile.

- In the 2018 Royal Ballet version, Siegfried rescued Odette from the lake, but she turns out to be dead, even though the spell is broken.[36]

Structure[edit]

Tchaikovsky’s original score (including additions for the original 1877 production),[37] which differs from the score as revised by Riccardo Drigo for the revival of Petipa and Ivanov that is still used by most ballet companies. The titles for each number are from the original published score. Some of the numbers are titled simply as musical indications, those that are not are translated from their original French titles.

Act 1[edit]

- Introduction: Moderato assai – Allegro non-troppo – Tempo I

Played by the Ballet Française Symphony Orchestra

- No. 1 Scène: Allegro giusto

- No. 2 Waltz: Tempo di valse

- No. 3 Scène: Allegro moderato

- No. 4 Pas de trois

- 1. Intrada (or Entrée): Allegro

- 2. Andante sostenuto

- 3. Allegro semplice, Presto

- 4. Moderato

- 5. Allegro

- 6. Coda: Allegro vivace

- No. 5 Pas de deux for Two Merry-makers (later fashioned into the Black Swan Pas de Deux)

- 1. Tempo di valse ma non troppo vivo, quasi moderato

- 2. Andante – Allegro

- 3. Tempo di valse

- 4. Coda: Allegro molto vivace

- No. 6 Pas d’action: Andantino quasi moderato – Allegro

- No. 7 Sujet (Introduction to the Dance with Goblets)

- No. 8 Dance with Goblets: Tempo di polacca

- No. 9 Finale: Sujet, Andante

Act 2[edit]

Played by the Ballet Française Symphony Orchestra

- No. 10 Scène: Moderato

- No. 11 Scène: Allegro moderato, Moderato, Allegro vivo

- No. 12 Scène: Allegro, Moderato assai quasi andante

- No. 13 Dances of the Swans

- 1. Tempo di valse

- 2. Moderato assai

- 3. Tempo di valse

- 4. Allegro moderato (later the famous Dance of the Little Swans)

- 5. Pas d’action: Andante, Andante non-troppo, Allegro (material borrowed from Undina)

- 6. Tempo di valse

- 7. Coda: Allegro vivo

- No. 14 Scène: Moderato

Act 3[edit]

Played by the Ballet Française Symphony Orchestra

- No. 15 Scène: March – Allegro giusto

- No. 16 Ballabile: Dance of the Corps de Ballet and the Dwarves: Moderato assai, Allegro vivo

- No. 17 Entrance of the Guests and Waltz: Allegro, Tempo di valse

- No. 18 Scène: Allegro, Allegro giusto

- No. 19 Pas de six

- 1. Intrada (or Entrée): Moderato assai

- 2. Variation 1: Allegro

- 3. Variation 2: Andante con moto (likely used as an adage after the Intrada but either composed inadvertently or published after the first variation)

- 4. Variation 3: Moderato

- 5. Variation 4: Allegro

- 6. Variation 5: Moderato, Allegro semplice

- 7. Grand Coda: Allegro molto

- Appendix I – Pas de deux pour Mme. Anna Sobeshchanskaya (from the original music by Ludwig Minkus and later choreographed by George Balanchine as the Tchaikovsky Pas de deux)

- # Intrada: Moderato – Andante

- # Variation 1: Allegro moderato

- # Variation 2: Allegro

- # Coda: Allegro molto vivace

- No. 20 Hungarian Dance: Czardas – Moderato assai, Allegro moderato, Vivace

- Appendix II – No. 20a Danse russe pour Mlle. Pelageya Karpakova: Moderato, Andante semplice, Allegro vivo, Presto

- No. 21 Danse Espagnole: Allegro non-troppo (Tempo di bolero)

- No. 22 Danse Napolitaine: Allegro moderato, Andantino quasi moderato, Presto

- No. 23 Mazurka: Tempo di mazurka

- No. 24 Scène: Allegro, Tempo di valse, Allegro vivo

Act 4[edit]

Played by the Ballet Française Symphony Orchestra

- No. 25 Entr’acte: Moderato

- No. 26 Scène: Allegro non-troppo

- No. 27 Dance of the Little Swans: Moderato

- No. 28 Scène: Allegro agitato, Molto meno mosso, Allegro vivace

- No. 29 Scène finale: Andante, Allegro, Alla breve, Moderato e maestoso, Moderato

Adaptations and references[edit]

Live-action film[edit]

- The opening credits for the first sound version of Dracula (1931) starring Bela Lugosi includes a modified version of the Swan Theme from act 2. The same piece was later used for the credits of The Mummy (1932) as well as Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) and is often used as a backing track for the silent film, Phantom of the Opera (1925).

- The film I Was an Adventuress (1940) includes a long sequence from the ballet.

- The plot of the 1965 British comedy film The Intelligence Men reaches its climax at a performance of the ballet, with an assassination attempt on the ballerina portraying Odette.

- The 1966 American political thriller film Torn Curtain directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Paul Newman and Julie Andrews contains a scene from the ballet Swan Lake. The lead couple of the film, played by Newman and Andrews, are escaping from East Berlin during the Cold War and attend a performance of the ballet as part of their escape plan. They are spotted and reported to the police by the lead ballerina (Tamara Toumanova) during the ballet performance. Their dramatic escape from the theatre during the ballet is a high point of the film.

- In 1968–69, the Kirov Ballet along with Lenfilm studios produced a filmed version of the ballet starring Yelena Yevteyeva as Odette.[38]

- In the film Funny Girl (1968), Barbra Streisand, playing Fanny Brice, dances in a comedic spoof of Swan Lake.

- The ballet is central to the plot of Étoile (1989).

- John Williams’ famous theme «The Imperial March» from the Music of Star Wars is notably reminiscent in harmonic progression, orchestration, and some melodic constructs to certain presentations of the Swan Theme.

- In Brain Donors (1992), the three main characters try and succeed in sabotaging a fictional production of the ballet.

- Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010) focuses on two characters from Swan Lake—the Princess Odette, sometimes called the White Swan, and her evil duplicate, the witch Odile (the Black Swan), and takes its inspiration from the ballet’s story, although it does not literally follow it. Clint Mansell’s score contains music from the ballet, with more elaborate restructuring to fit the horror tone of the film.

- In Of Gods and Men (2011), the climactic Swan Lake music is played at the monks’ Last Supper-reminiscent dinner.

- In the film T-34, music from Swan Lake could be heard while the main characters test-drive a captured T-34 for the Germans and pulling off ballet-style moves with the tank.

- As of August 2020, a live-action adaptation of the ballet is being produced by Universal Pictures, written by Olivier Award-winning playwright Jessica Swale and starring Felicity Jones.[39]

- The end of the ballet is in the film The Courier (2020).

Animated theatrical and direct-to-video productions[edit]

- Swan Lake (1981) is a feature-length anime produced by the Japanese company Toei Animation and directed by Koro Yabuki. The adaptation uses Tchaikovsky’s score and remains relatively faithful to the story. Two separate English dubs were made, one featuring regular voice actors, and one using celebrities as the main principals (Pam Dawber as Odette, Christopher Atkins as Siegfried, David Hemmings as Rothbart, and Kay Lenz as Odille). The second dub was recorded at Golden Sync Studios and aired on American Movie Classics in December 1990 and The Disney Channel in January 1994.[40] It was presently distributed in the United States by The Samuel Goldwyn Company. It was also distributed in France and the United Kingdom by Rouge Citron Production.[41]

- Swan Lake (1994) is a 28-minute traditional two-dimensional animation narrated by Dudley Moore. It is one of five animations in the Storyteller’s Classics series. Like the 1981 version, it also uses Tchaikovsky’s music throughout and is quite faithful to the original story. What sets it apart is the climactic scene, in which the prince swims across the lagoon towards Rothbart’s castle to rescue Odette, who is being held prisoner there. Rothbart points his finger at the prince and zaps him to turn him into a duck – but then, the narrator declares, «Sometimes, even magic can go very, very wrong.» After a moment, the duck turns into an eagle and flies into Rothbart’s castle, where the prince resumes his human form and engages Rothbart in battle. This animation was produced by Madman Movies for Castle Communications. The director was Chris Randall, the producer was Bob Burrows, the production co-ordinator was Lesley Evans and the executive producers were Terry Shand and Geoff Kempin. The music was performed by the Moscow State Orchestra. It was shown on TVOntario in December 1997 and was distributed on home video in North America by Castle Vision International, Orion Home Video and J.L. Bowerbank & Associates.

- The Swan Princess (1994) is a Nest Entertainment film based on the Swan Lake story. It stays fairly close to the original story, but does contain many differences. For example, instead of the Swan Maidens, we have the addition of sidekicks Puffin the puffin, Speed the tortoise, and Jean-Bob the frog. Several of the characters are renamed – Prince Derek instead of Siegfried, his friend Bromley instead of Benno and his tutor Rogers instead of Wolfgang; Derek’s mother is named Queen Uberta. Another difference is Odette and Derek knowing each other from when they were children, which introduces us to Odette’s father, King William and explains how and why Odette is kidnapped by Rothbart. The character Odile is replaced by an old hag (unnamed in this movie, but known as Bridget in the sequels), as Rothbart’s sidekick until the end. Also, this version contains a happy ending, allowing both Odette and Derek to survive as humans once Rothbart is defeated. It has nine sequels, The Swan Princess: Escape from Castle Mountain (1997), The Swan Princess: The Mystery of the Enchanted Kingdom (1998), The Swan Princess Christmas (2012), The Swan Princess: A Royal Family Tale (2014), The Swan Princess: Princess Tomorrow, Pirate Today (2016), The Swan Princess: Royally Undercover (2017), The Swan Princess: A Royal Myztery (2018), The Swan Princess: Kingdom of Music (2019), and The Swan Princess: A Royal Wedding (2020), which deviate even further from the ballet. None of the films contain Tchaikovsky’s music.

- Barbie of Swan Lake (2003) is a direct-to-video children’s movie featuring Tchaikovsky’s music and motion capture from the New York City Ballet and based on the Swan Lake story. The story deviates more from the original than The Swan Princess, although it does consist of similarities to the plot from The Swan Princess. In this version, Odette is not a princess by birth, but a baker’s daughter and instead of being kidnapped by Rothbart and taken to the lake against her will, she discovers the Enchanted Forest when she willingly follows a unicorn there. She is also made into a more dominant heroine in this version, as she is declared as being the one who is destined to save the forest from Rothbart’s clutches when she frees a magic crystal. Another difference is the addition of new characters, such as Rothbart’s cousin the Fairy Queen, Lila the unicorn, Erasmus the troll and the Fairy Queen’s fairies and elves, who have also been turned into animals by Rothbart. These fairies and elves replace the Swan Maidens from the ballet. Also, it is the Fairy Queen’s magic that allows Odette to return to her human form at night, not Rothbart’s spell, which until the Fairy Queen counters, appears to be permanent. Other changes include renaming the Prince Daniel and a happy ending, instead of the ballet’s tragic ending.

- Barbie in the Pink Shoes (2013) features an adaptation of Swan Lake amongst its many fairytales.

Computer/video games[edit]

- The 1988 NES video game Final Fantasy II used a minor portion of Swan Lake just before fighting the Lamia Queen boss. In the WonderSwan Color and later versions the portion is longer.

- The 1990 LucasArts adventure game Loom used a major portion of the Swan Lake suite for its audio track, as well as incorporating a major swan theme into the storyline. It otherwise bore no resemblance to the original ballet.

- The 1991 DMA Design puzzle game Lemmings used «Dance of the Little Swans» in its soundtrack.

- The 1993 Treasure platform game McDonald’s Treasure Land Adventure uses a portion of Swan Lake as background music for one of its levels.[42][better source needed]

- The 2008 Nintendo DS game Imagine Ballet Star contains a shortened version of Swan Lake. The main character, who is directly controlled by the player of the game, dances to three shortened musical pieces from Swan Lake. Two of the pieces are solos and the third piece is a pas de deux.

- The 2009 SEGA video game Mario & Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games includes Swan Lake in its figure skating competition.

- The 2015 game FNAF 3 contains a music box version of a piece from Swan Lake.

- The 2016 Blizzard Entertainment game Overwatch contains two unlockable costumes for the character Widowmaker based on Odette and Odile.

- The 2020 Nintendo Switch game Paper Mario: The Origami King features a comedic ballet production of the song, as well as a punk remix.

Dance[edit]

The Silent Violinist, a professional mime busker act, that references the «swan princess» concept.

- The Swedish dancer/choreographer Fredrik Rydman has produced a modern dance/street dance interpretation of the ballet entitled Swan Lake Reloaded. It depicts the «swans» as heroin addict prostitutes who are kept in place by Rothbart, their pimp. The production’s music uses themes and melodies from Tchaikovsky’s score and incorporates them into hip-hop and techno tunes.[43]

Literature[edit]

- Amiri & Odette (2009) is a verse retelling by Walter Dean Myers with illustrations by Javaka Steptoe.[44] Myers sets the story in the Swan Lake Projects of a large city. Amiri is a basketball-playing «Prince of the Night», a champion of the asphalt courts in the park. Odette belongs to Big Red, a dealer, a power on the streets.

- The Black Swan (1999) is a fantasy novel written by Mercedes Lackey that re-imagines the original story and focuses heavily on Odile. Rothbart’s daughter is a sorceress in her own right who comes to sympathise with Odette.

- The Sorcerer’s Daughter (2003) is a fantasy novel by Irina Izmailova, a retelling of the ballet’s plot. The boyish and careless Siegfried consciously prefers the gentle, equally childlike Odile, while the stern and proud Odette is from the very beginning attracted to Rothbart (who later turns out to be the kingdom’s rightful monarch in hiding).

- Swan Lake (1989) is a children’s novel written by Mark Helprin and illustrated by Chris Van Allsburg, which re-creates the original story as a tale about political strife in an unnamed Eastern European country. In it, Odette becomes a princess hidden from birth by the puppetmaster (and eventually usurper) behind the throne, with the story being retold to her child.

Music[edit]

- Japanese instrumental rock group Takeshi Terauchi & Bunnys recorded this on their 1967 album, Let’s Go Unmei.

- Belgian band Wallace Collection quote from Act 2 Scene 10 in their track «Daydream» (1969).

- British ska band Madness featured a ska version in 1979 on their debut album One Step Beyond…

- South Korean group Shinhwa re-imagines the main theme into a hip-hop k-pop song “T.O.P. (Twinkling of Paradise)” (1999)

- Los Angeles group Sweetbox uses the main theme for the chorus of their song «Superstar» from the 2001 album Classified.

- German singer Jeanette Biedermann uses the Swan Lake melody structure for her 2001 single release «How It’s Got To Be».

- Spanish symphonic metal band Dark Moor borrows elements on the song “Swan Lake”, the first track of their 2009 album Autumnal.

- A reggae version of the Swan Lake ballet appears on the 2017 album Classical Made Modern 3.[45]

- Canadian metal band The Agonist has made an a cappella version of act 2’s «Scène. Moderato», which is included in their second studio album, Lullabies for the Dormant Mind.

- Beyoncé uses the ballet’s famous theme in her «visual album» Lemonade, a reference that underscores the film’s meditation on infidelity.

- Scott Hamilton — Tenor Saxophone. Jazz interpretation — Scott Hamilton CLASSICS[46]

Musicals[edit]

- Odette – The Dark Side of Swan Lake, a musical written by Alexander S. Bermange and Murray Woodfield, was staged at the Bridewell Theatre, London in October 2007.

- In Radio City Christmas Spectacular, The Rockettes do a short homage to Swan Lake during the performance of the «Twelve Days of Christmas (Rock and Dance Version)», with the line «Seven Swans A-Swimming».

- Billy Elliot the Musical incorporates the most famous section of Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake in a dance number, in which the main character dances while shadowed by his future, adult self.

- The musical Anastasia includes a scene in which several of the main characters attend a performance of Swan Lake in Paris near the show’s climax. The four characters sing about their inner conflicts and desires as Tchaikovsky’s score blends into the musical’s melodies, the dancers onstage representing both the ballet’s characters and the thoughts of each singer in turn.

Television[edit]

- During the era of the Soviet Union, Soviet state television preempted large announcements with video recordings of Swan Lake on four infamous occasions. In 1982 state television broadcast recordings following the death of Leonid Brezhnev. In 1984 recordings preempted the announcement of the death of Yuri Andropov. In 1985, recordings preempted the announcement of the death of General Secretary Konstantin Chernenko.[47] The final and most oft-cited instance of the use of Swan Lake in this context was during the August 1991 Soviet coup attempt leading up to the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[48]

- When independent Russian news channel Dozhd (also known as «TV Rain») was forced to shut down due to censorship laws caused by the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the station chose to end its final newscast with Swan Lake in a reference to its use in 1991.[49][50]

- Princess Tutu (2002) is an anime television series whose heroine, Duck, wears a costume reminiscent of Odette’s. She is a duck transformed by a writer into a girl (rather than the other way around), while her antagonist, Rue, dressed as Odile, is a girl who had been raised to believe she is a raven. Other characters include Mytho in the role of Siegfried, who is even referred to by this name towards the end of the second act, and Drosselmeyer playing in the role of Rothbart. The score of Swan Lake, along with that of The Nutcracker, is used throughout, as is, occasionally, the Petipa choreography, most notably in episode 13, where Duck dances the climactic pas de deux alone, complete with failed lifts and catches.

- In the second season of the anime Kaleido Star, a circus adaptation of Swan Lake becomes one of the Kaleido Stage’s most important and successful shows. Main character Sora Naegino plays Princess Odette, with characters Leon Oswald as Prince Siegfried and May Wong as Odile.

- In episode 213 of The Muppet Show, Rudolf Nureyev performs Swine Lake with a giant ballerina pig.

- In episode 105 of Cagney and Lacey, Det. Chris Cagney went to this with her boyfriend and hated it so that she fell asleep in the second act.

- Swan Lake was heard in two episodes of the Playhouse Disney series Little Einsteins: «Quincy and the Magic Instruments» and «The Blue Footed Boobey Bird Ballet».

- In the Tiny Toon Adventures episode Loon Lake, Babs Bunny helps out Shirley the Loon after she was ridiculed by a group of snobbish swans in ballet class while preparing for a performance of Swan Lake.

- In Dexter’s Laboratory episode, Deedeemensional, Dexter, in order to deliver an important message to his future self, was forced to dance Swan Lake with Dee Dee and her future self.

- The Beavis and Butt-Head episode «A Very Special Episode» uses the same arrangement used in Dracula and The Mummy while Beavis is feeding the bird he saved.

- In the animated children’s show Wonder Pets, Linny, Tuck and Ming-Ming help encourage a baby swan to dance in his own way. The music of Swan Lake is used.

- A close arrangement of the waltz from act 1 appears in episodes 16, 23 and 78 of My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, «Sonic Rainboom» , «The Cutie Mark Chronicles» and «Simple Ways».

Selected discography[edit]

Audio[edit]

| Year | Conductor | Orchestra | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | Antal Doráti | Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra | first complete recording, late 1953, mastered originally in mono only; some mock-stereo issues released on LP |

| 1959 | Ernest Ansermet | Orchestre de la Suisse Romande | taped in stereo Oct–Nov. 1958, abridged |

| 1974 | Anatole Fistoulari | Radio Filharmonisch Orkest | with Ruggiero Ricci, violin |