Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter ( bee-ON-say;[4] born September 4, 1981)[5] is an American singer, songwriter, and dancer. Beyoncé’s boundary-pushing artistry and vocals have made her the most influential female musician of the 21st century, according to NPR.[6] Her success has led to her becoming a cultural icon and earning her the nickname «Queen Bey».[7]

|

Beyoncé |

|

|---|---|

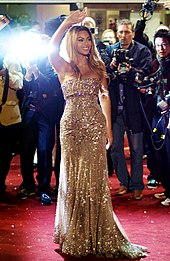

Beyoncé at The Lion King premiere in 2019 |

|

| Born |

Beyonce Giselle Knowles[a] September 4, 1981 (age 41) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1997–present |

| Organizations |

|

| Works |

|

| Spouse |

Jay-Z (m. ) |

| Children | 3, including Blue Ivy |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Solange Knowles (sister) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instrument(s) | Vocals |

| Labels |

|

| Member of | The Carters |

| Formerly of | Destiny’s Child |

| Website | beyonce.com |

| Signature | |

|

Beyoncé performed in various singing and dancing competitions as a child. She rose to fame in the late 1990s as a member of the R&B girl group Destiny’s Child, one of the best-selling girl groups of all time. Their hiatus saw the release of her debut album Dangerously in Love (2003), which featured the US Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles «Crazy in Love» and «Baby Boy». Following the 2006 disbanding of Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé released her second solo album, B’Day, which contained singles «Irreplaceable» and «Beautiful Liar». Beyoncé also starred in multiple films such as Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), The Pink Panther (2006), Dreamgirls (2006), Obsessed (2009), and The Lion King (2019). Her marriage to Jay-Z and her portrayal of Etta James in Cadillac Records (2008) influenced her third album, I Am… Sasha Fierce (2008), which earned a record-setting six Grammy Awards in 2010. It spawned the successful singles «If I Were a Boy», «Single Ladies», and «Halo». After professionally splitting from her manager and father Mathew Knowles in 2010, she released her musically diverse fourth album 4 in 2011.

Beyoncé later achieved universal acclaim for her sonically experimental visual albums, Beyoncé (2013) and Lemonade (2016), the latter of which was the world’s best-selling album of 2016 and the most acclaimed album of her career, exploring themes of infidelity, feminism, and womanism. In 2018, she released Everything Is Love, a collaborative album with her husband, Jay-Z, as the Carters. As a featured artist, Beyoncé topped the Billboard Hot 100 with the remixes of «Perfect» by Ed Sheeran in 2017 and «Savage» by Megan Thee Stallion in 2020. The same year, she released the musical film Black Is King with an accompanying visual album, with praise from critics. In 2022, Beyoncé received further critical acclaim for her seventh studio album Renaissance, which experimented with disco and house music and paid homage to LGBTQ+ ball culture. She obtained her first solo number-one since 2008 with the album’s lead single, «Break My Soul», with Renaissance being her first solo studio album since 2016.

She is one of the world’s best-selling recording artists, having sold over 200 million records worldwide.[8][9] Her success during the 2000s was recognized with the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA)’s Top Certified Artist of the Decade as well as Billboard‘s Top Female Artist of the Decade.[10] She is the first solo artist to have their first seven studio albums debut at number one on the Billboard 200.[11][12] Beyoncé’s accolades include 28 Grammy Awards, 26 MTV Video Music Awards (including the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award in 2014), 24 NAACP Image Awards, 31 BET Awards, and 17 Soul Train Music Awards; all of which are more than any other singer. In 2014, Billboard named her the highest-earning black musician of all time, while in 2020, she was included on Time‘s list of 100 women who defined the last century.[13]

Life and career

1981–1996: Early life and career beginnings

Beyonce Giselle Knowles[a] was born on September 4, 1981, in Houston, Texas, to Celestine «Tina» Knowles (née Beyonce), a hairdresser and salon owner, and Mathew Knowles, a Xerox sales manager;[14] Tina is Louisiana Creole, and Mathew is African American.[15][16][17][18] Beyoncé’s younger sister, Solange Knowles, is also a singer and a former backup dancer for Destiny’s Child. Solange and Beyoncé are the first sisters to have both had number one albums.[19]

Beyoncé’s maternal grandparents, Lumas Beyince, and Agnez Dereon (daughter of Odilia Broussard and Eugene DeRouen),[20] were French-speaking Louisiana Creoles, with roots in New Iberia.[21] Beyoncé is considered a Creole, passed on to her by her grandparents.[20][22] Through her mother, Beyoncé is a descendant of many French aristocrats from the southwest of France, including the family of the Viscounts de Béarn since the 9th century, and the Viscounts de Belzunce.[23] She is also a descendant of Acadian militia officer Joseph Broussard, who was exiled to French Louisiana after the expulsion of the Acadians.[16] Her fourth great-grandmother, Marie-Françoise Trahan, was born in 1774 in Bangor, located on Belle Île, France. Trahan was a daughter of Acadians who had taken refuge on Belle Île after the Acadian expulsion. The Estates of Brittany had divided the lands of Belle Île to distribute them among 78 other Acadian families and the already settled inhabitants. The Trahan family lived on Belle Île for over ten years before immigrating to Louisiana, where she married a Broussard descendant.[24] Beyoncé researched her ancestry and discovered that she is descended from a slave owner who married his slave.[25] Her mother is also of distant Jewish, Spanish, Chinese and Indonesian ancestry.[26][27][28]

Beyoncé was raised Catholic and attended St. Mary’s Montessori School in Houston, where she enrolled in dance classes.[29] Her singing was discovered when dance instructor Darlette Johnson began humming a song and she finished it, able to hit the high-pitched notes.[30] Beyoncé’s interest in music and performing continued after winning a school talent show at age seven, singing John Lennon’s «Imagine» to beat 15/16-year-olds.[31][32] In the fall of 1990, Beyoncé enrolled in Parker Elementary School, a music magnet school in Houston, where she would perform with the school’s choir.[33] She also attended the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts[34] and later Alief Elsik High School.[15][35] Beyoncé was also a member of the choir at St. John’s United Methodist Church as a soloist for two years.[36]

When Beyoncé was eight, she met LaTavia Roberson at an audition for an all-girl entertainment group.[37] They were placed into a group called Girl’s Tyme with three other girls, and rapped and danced on the talent show circuit in Houston.[38] After seeing the group, R&B producer Arne Frager brought them to his Northern California studio and placed them in Star Search, the largest talent show on national TV at the time. Girl’s Tyme failed to win, and Beyoncé later said the song they performed was not good.[39][40] In 1995, Beyoncé’s father resigned from his job to manage the group.[41] The move reduced Beyoncé’s family’s income by half, and her parents were forced to sell their house and cars and move into separated apartments.[15][42] Mathew cut the original line-up to four and the group continued performing as an opening act for other established R&B girl groups.[37] The girls auditioned before record labels and were finally signed to Elektra Records, moving to Atlanta Records briefly to work on their first recording, only to be cut by the company.[15] This put further strain on the family, and Beyoncé’s parents separated. On October 5, 1995, Dwayne Wiggins’s Grass Roots Entertainment signed the group. In 1996, the girls began recording their debut album under an agreement with Sony Music, the Knowles family reunited, and shortly after, the group got a contract with Columbia Records.[31]

1997–2002: Destiny’s Child

The group changed their name to Destiny’s Child in 1996, based upon a passage in the Book of Isaiah.[43] In 1997, Destiny’s Child released their major label debut song «Killing Time» on the soundtrack to the 1997 film Men in Black.[40] In November, the group released their debut single and first major hit, «No, No, No». They released their self-titled debut album in February 1998, which established the group as a viable act in the music industry, with moderate sales and winning the group three Soul Train Lady of Soul Awards for Best R&B/Soul Album of the Year, Best R&B/Soul or Rap New Artist, and Best R&B/Soul Single for «No, No, No». The group released their Multi-Platinum second album The Writing’s on the Wall in 1999. The record features some of the group’s most widely known songs such as «Bills, Bills, Bills», the group’s first number-one single, «Jumpin’ Jumpin’« and «Say My Name», which became their most successful song at the time, and would remain one of their signature songs. «Say My Name» won the Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals and the Best R&B Song at the 43rd Annual Grammy Awards.[37] The Writing’s on the Wall sold more than eight million copies worldwide.[39] During this time, Beyoncé recorded a duet with Marc Nelson, an original member of Boyz II Men, on the song «After All Is Said and Done» for the soundtrack to the 1999 film, The Best Man.[44]

LeToya Luckett and Roberson became unhappy with Mathew’s managing of the band and eventually were replaced by Farrah Franklin and Michelle Williams.[37] Beyoncé experienced depression following the split with Luckett and Roberson after being publicly blamed by the media, critics, and blogs for its cause.[45] Her long-standing boyfriend left her at this time.[46] The depression was so severe it lasted for a couple of years, during which she occasionally kept herself in her bedroom for days and refused to eat anything.[47] Beyoncé stated that she struggled to speak about her depression because Destiny’s Child had just won their first Grammy Award, and she feared no one would take her seriously.[48] Beyoncé would later speak of her mother as the person who helped her fight it.[47] Franklin was then dismissed, leaving just Beyoncé, Rowland, and Williams.[49]

The remaining band members recorded «Independent Women Part I», which appeared on the soundtrack to the 2000 film Charlie’s Angels. It became their best-charting single, topping the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart for eleven consecutive weeks.[37] In early 2001, while Destiny’s Child was completing their third album, Beyoncé landed a major role in the MTV made-for-television film, Carmen: A Hip Hopera, starring alongside American actor Mekhi Phifer. Set in Philadelphia, the film is a modern interpretation of the 19th-century opera Carmen by French composer Georges Bizet.[50] When the third album Survivor was released in May 2001, Luckett and Roberson filed a lawsuit claiming that the songs were aimed at them.[37] The album debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200, with first-week sales of 663,000 copies sold.[51] The album spawned other number-one hits, «Bootylicious» and the title track, «Survivor», the latter of which earned the group a Grammy Award for Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals.[52] After releasing their holiday album 8 Days of Christmas in October 2001, the group announced a hiatus to further pursue solo careers.[37]

In July 2002, Beyoncé made her theatrical film debut, playing Foxxy Cleopatra alongside Mike Myers in the comedy film Austin Powers in Goldmember,[53] which spent its first weekend atop the U.S. box office and grossed $73 million.[54] Beyoncé released «Work It Out» as the lead single from its soundtrack album which entered the top ten in the UK, Norway, and Belgium.[55] In 2003, Beyoncé starred opposite Cuba Gooding, Jr., in the musical comedy The Fighting Temptations as Lilly, a single mother with whom Gooding’s character falls in love.[56] The film received mixed reviews from critics but grossed $30 million in the U.S.[57][58] Beyoncé released «Fighting Temptation» as the lead single from the film’s soundtrack album, with Missy Elliott, MC Lyte, and Free which was also used to promote the film.[59] Another of Beyoncé’s contributions to the soundtrack, «Summertime», fared better on the U.S. charts.[60]

2003–2005: Dangerously in Love and Destiny Fulfilled

Beyoncé’s first solo recording was a feature on Jay-Z’s song «’03 Bonnie & Clyde» that was released in October 2002, peaking at number four on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart.[62] On June 14, 2003, Beyoncé premiered songs from her first solo album Dangerously in Love during her first solo concert and the pay-per-view television special, «Ford Presents Beyoncé Knowles, Friends & Family, Live From Ford’s 100th Anniversary Celebration in Dearborn, Michigan».[63] The album was released on June 24, 2003, after Michelle Williams and Kelly Rowland had released their solo efforts.[64] The album sold 317,000 copies in its first week, debuted atop the Billboard 200,[65] and has since sold 11 million copies worldwide.[66] The album’s lead single, «Crazy in Love», featuring Jay-Z, became Beyoncé’s first number-one single as a solo artist in the US.[67] The single «Baby Boy» also reached number one,[61] and singles, «Me, Myself and I» and «Naughty Girl», both reached the top-five.[68] The album earned Beyoncé a then record-tying five awards at the 46th Annual Grammy Awards; Best Contemporary R&B Album, Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for «Dangerously in Love 2», Best R&B Song and Best Rap/Sung Collaboration for «Crazy in Love», and Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals for «The Closer I Get to You» with Luther Vandross. During the ceremony, she performed with Prince.[69]

In November 2003, she embarked on the Dangerously in Love Tour in Europe and later toured alongside Missy Elliott and Alicia Keys for the Verizon Ladies First Tour in North America.[70] On February 1, 2004, Beyoncé performed the American national anthem at Super Bowl XXXVIII, at the Reliant Stadium in Houston, Texas.[71] After the release of Dangerously in Love, Beyoncé had planned to produce a follow-up album using several of the left-over tracks. However, this was put on hold so she could concentrate on recording Destiny Fulfilled, the final studio album by Destiny’s Child.[72] Released on November 15, 2004, in the US[73] and peaking at number two on the Billboard 200,[74][75] Destiny Fulfilled included the singles «Lose My Breath» and «Soldier», which reached the top five on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[76] Destiny’s Child embarked on a worldwide concert tour, Destiny Fulfilled… and Lovin’ It sponsored by McDonald’s Corporation,[77] and performed hits such as «No, No, No», «Survivor», «Say My Name», «Independent Women» and «Lose My Breath». In addition to renditions of the group’s recorded material, they also performed songs from each singer’s solo careers, most notably numbers from Dangerously in Love. and during the last stop of their European tour, in Barcelona on June 11, 2005, Rowland announced that Destiny’s Child would disband following the North American leg of the tour.[78] The group released their first compilation album Number 1’s on October 25, 2005, in the US[79] and accepted a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in March 2006.[80] The group has sold 60 million records worldwide.[81][82]

2006–2007: B’Day and Dreamgirls

Beyoncé’s second solo album B’Day was released on September 4, 2006, in the US, to coincide with her twenty-fifth birthday.[83] It sold 541,000 copies in its first week and debuted atop the Billboard 200, becoming Beyoncé’s second consecutive number-one album in the United States.[84] The album’s lead single «Déjà Vu», featuring Jay-Z, reached the top five on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[68] The second international single «Irreplaceable» was a commercial success worldwide, reaching number one in Australia, Hungary, Ireland, New Zealand and the United States.[68][85] B’Day also produced three other singles; «Ring the Alarm»,[86] «Get Me Bodied»,[87] and «Green Light» (released in the United Kingdom only).[88]

At the 49th Annual Grammy Awards (2007), B’Day was nominated for five Grammy Awards, including Best Contemporary R&B Album, Best Female R&B Vocal Performance for «Ring the Alarm» and Best R&B Song and Best Rap/Sung Collaboration»for «Déjà Vu»; the Freemasons club mix of «Déjà Vu» without the rap was put forward in the Best Remixed Recording, Non-Classical category. B’Day won the award for Best Contemporary R&B Album.[89] The following year, B’Day received two nominations – for Record of the Year for «Irreplaceable» and Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals for «Beautiful Liar» (with Shakira), also receiving a nomination for Best Compilation Soundtrack Album for Motion Pictures, Television or Other Visual Media for her appearance on Dreamgirls: Music from the Motion Picture (2006).[90]

Her first acting role of 2006 was in the comedy film The Pink Panther starring opposite Steve Martin,[91] grossing $158.8 million at the box office worldwide.[92] Her second film Dreamgirls, the film version of the 1981 Broadway musical[93] loosely based on The Supremes, received acclaim from critics and grossed $154 million internationally.[94][95][96] In it, she starred opposite Jennifer Hudson, Jamie Foxx, and Eddie Murphy playing a pop singer based on Diana Ross.[97] To promote the film, Beyoncé released «Listen» as the lead single from the soundtrack album.[98] In April 2007, Beyoncé embarked on The Beyoncé Experience, her first worldwide concert tour, visiting 97 venues[99] and grossed over $24 million.[note 1] Beyoncé conducted pre-concert food donation drives during six major stops in conjunction with her pastor at St. John’s and America’s Second Harvest. At the same time, B’Day was re-released with five additional songs, including her duet with Shakira «Beautiful Liar».[101]

2008–2010: I Am… Sasha Fierce

I Am… Sasha Fierce was released on November 18, 2008, in the United States.[102] The album formally introduces Beyoncé’s alter ego Sasha Fierce, conceived during the making of her 2003 single «Crazy in Love». It was met with generally mediocre reviews from critics,[103] but sold 482,000 copies in its first week, debuting atop the Billboard 200, and giving Beyoncé her third consecutive number-one album in the US.[104] The album featured the number-one song «Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)»[105] and the top-five songs «If I Were a Boy» and «Halo».[68][106] Achieving the accomplishment of becoming her longest-running Hot 100 single in her career,[107] «Halo«‘s success in the U.S. helped Beyoncé attain more top-ten singles on the list than any other woman during the 2000s.[108] It also included the successful «Sweet Dreams»,[109] and singles «Diva», «Ego», «Broken-Hearted Girl» and «Video Phone». The music video for «Single Ladies» has been parodied and imitated around the world, spawning the «first major dance craze» of the Internet age according to the Toronto Star.[110] The video has won several awards, including Best Video at the 2009 MTV Europe Music Awards,[111] the 2009 Scottish MOBO Awards,[112] and the 2009 BET Awards.[113] At the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, the video was nominated for nine awards, ultimately winning three including Video of the Year.[114] Its failure to win the Best Female Video category, which went to American singer-songwriter Taylor Swift’s «You Belong with Me», led to Kanye West interrupting the ceremony and Beyoncé improvising a re-presentation of Swift’s award during her own acceptance speech.[114] In March 2009, Beyoncé embarked on the I Am… World Tour, her second headlining worldwide concert tour, consisting of 108 shows, grossing $119.5 million.[115]

Beyoncé further expanded her acting career, starring as blues singer Etta James in the 2008 musical biopic Cadillac Records. Her performance in the film received praise from critics,[116] and she garnered several nominations for her portrayal of James, including a Satellite Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress, and a NAACP Image Award nomination for Outstanding Supporting Actress.[117][118] Beyoncé donated her entire salary from the film to Phoenix House, an organization of rehabilitation centers for heroin addicts around the country.[119] On January 20, 2009, Beyoncé performed James’ «At Last» at First Couple Barack and Michelle Obama’s first inaugural ball.[120] Beyoncé starred opposite Ali Larter and Idris Elba in the thriller, Obsessed. She played Sharon Charles, a mother and wife whose family is threatened by her husband’s stalker. Although the film received negative reviews from critics,[121] the movie did well at the U.S. box office, grossing $68 million – $60 million more than Cadillac Records[122] – on a budget of $20 million.[123] The fight scene finale between Sharon and the character played by Ali Larter also won the 2010 MTV Movie Award for Best Fight.[124]

At the 52nd Annual Grammy Awards, Beyoncé received ten nominations, including Album of the Year for I Am… Sasha Fierce, Record of the Year for «Halo», and Song of the Year for «Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)», among others.[125] She tied with Lauryn Hill for most Grammy nominations in a single year by a female artist.[126] Beyoncé went on to win six of those nominations, breaking a record she previously tied in 2004 for the most Grammy awards won in a single night by a female artist with six. In 2010, Beyoncé was featured on Lady Gaga’s single «Telephone» and appeared in its music video.[127][128] The song topped the U.S. Pop Songs chart, becoming the sixth number-one for both Beyoncé and Gaga, tying them with Mariah Carey for most number-ones since the Nielsen Top 40 airplay chart launched in 1992.[129] «Telephone» received a Grammy Award nomination for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals.[130]

Beyoncé announced a hiatus from her music career in January 2010, heeding her mother’s advice, «to live life, to be inspired by things again».[131][132] During the break she and her father parted ways as business partners.[133][134] Beyoncé’s musical break lasted nine months and saw her visit multiple European cities, the Great Wall of China, the Egyptian pyramids, Australia, English music festivals and various museums and ballet performances.[131][135]

2011–2013: 4 and Super Bowl XLVII halftime show

Beyoncé’s sound became mellower with 2011’s 4 which focused on traditional R&B styles. She performed the album during her 4 Intimate Nights with Beyoncé concert residency in August 2011

On June 26, 2011, she became the first solo female artist to headline the main Pyramid stage at the 2011 Glastonbury Festival in over twenty years.[136][137] Her fourth studio album 4 was released two days later in the US.[138] 4 sold 310,000 copies in its first week and debuted atop the Billboard 200 chart, giving Beyoncé her fourth consecutive number-one album in the US. The album was preceded by two of its singles «Run the World (Girls)» and «Best Thing I Never Had».[68][127][139] The fourth single «Love on Top» spent seven consecutive weeks at number one on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart, while peaking at number 20 on the Billboard Hot 100, the highest peak from the album.[140] 4 also produced four other singles; «Party», «Countdown», «I Care» and «End of Time». «Eat, Play, Love», a cover story written by Beyoncé for Essence that detailed her 2010 career break, won her a writing award from the New York Association of Black Journalists.[141] In late 2011, she took the stage at New York’s Roseland Ballroom for four nights of special performances:[142] the 4 Intimate Nights with Beyoncé concerts saw the performance of her 4 album to a standing room only.[142] On August 1, 2011, the album was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), having shipped 1 million copies to retail stores.[143] By December 2015, it reached sales of 1.5 million copies in the US.[144] The album reached one billion Spotify streams on February 5, 2018, making Beyoncé the first female artist to have three of their albums surpass one billion streams on the platform.[145]

In June 2012, she performed for four nights at Revel Atlantic City’s Ovation Hall to celebrate the resort’s opening, her first performances since giving birth to her daughter.[146][147]

In January 2013, Destiny’s Child released Love Songs, a compilation album of the romance-themed songs from their previous albums and a newly recorded track, «Nuclear».[148] Beyoncé performed the American national anthem singing along with a pre-recorded track at President Obama’s second inauguration in Washington, D.C.[149][150] The following month, Beyoncé performed at the Super Bowl XLVII halftime show, held at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome in New Orleans.[151] The performance stands as the second most tweeted about moment in history at 268,000 tweets per minute.[152] At the 55th Annual Grammy Awards, Beyoncé won for Best Traditional R&B Performance for «Love on Top».[153] Her feature-length documentary film, Life Is But a Dream, first aired on HBO on February 16, 2013.[154] The film was co-directed by Beyoncé herself.[155]

2013–2015: Beyoncé

Beyoncé performing during The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour in 2013. The tour is one of the highest grossing tours of the decade.

Beyoncé embarked on The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour on April 15 in Belgrade, Serbia; the tour included 132 dates that ran through to March 2014. It became the most successful tour of her career and one of the most successful tours of all time.[156] In May, Beyoncé’s cover of Amy Winehouse’s «Back to Black» with André 3000 on The Great Gatsby soundtrack was released.[157] Beyoncé voiced Queen Tara in the 3D CGI animated film, Epic, released by 20th Century Fox on May 24,[158] and recorded an original song for the film, «Rise Up», co-written with Sia.[159]

On December 13, 2013, Beyoncé unexpectedly released her eponymous fifth studio album on the iTunes Store without any prior announcement or promotion. The album debuted atop the Billboard 200 chart, giving Beyoncé her fifth consecutive number-one album in the US.[160] This made her the first woman in the chart’s history to have her first five studio albums debut at number one.[161] Beyoncé received critical acclaim[162] and commercial success, selling one million digital copies worldwide in six days;[163] Musically an electro-R&B album, it concerns darker themes previously unexplored in her work, such as «bulimia, postnatal depression [and] the fears and insecurities of marriage and motherhood».[164] The single «Drunk in Love», featuring Jay-Z, peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[165]

In April 2014, Beyoncé and Jay-Z officially announced their On the Run Tour. It served as the couple’s first co-headlining stadium tour together.[166] On August 24, 2014, she received the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards. Beyoncé also won home three competitive awards: Best Video with a Social Message and Best Cinematography for «Pretty Hurts», as well as best collaboration for «Drunk in Love».[167] In November, Forbes reported that Beyoncé was the top-earning woman in music for the second year in a row – earning $115 million in the year, more than double her earnings in 2013.[168] Beyoncé was reissued with new material in three forms: as an extended play, a box set, as well as a full platinum edition. According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), in the last 19 days of 2013, the album sold 2.3 million units worldwide, becoming the tenth best-selling album of 2013.[169] The album also went on to become the twentieth best-selling album of 2014.[170] As of November 2014, Beyoncé has sold over 5 million copies worldwide and has generated over 1 billion streams, as of March 2015.[171]

At the 57th Annual Grammy Awards in February 2015, Beyoncé was nominated for six awards, ultimately winning three: Best R&B Performance and Best R&B Song for «Drunk in Love», and Best Surround Sound Album for Beyoncé.[172][173] She was nominated for Album of the Year, but the award went to Beck for his album Morning Phase.[174]

2016–2018: Lemonade and Everything Is Love

On February 6, 2016, Beyoncé released «Formation» and its accompanying music video exclusively on the music streaming platform Tidal; the song was made available to download for free.[175] She performed «Formation» live for the first time during the NFL Super Bowl 50 halftime show. The appearance was considered controversial as it appeared to reference the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party and the NFL forbids political statements in its performances.[176][177][178] Immediately following the performance, Beyoncé announced The Formation World Tour, which highlighted stops in both North America and Europe.[179][180] It ended on October 7, with Beyoncé bringing out her husband Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar, and Serena Williams for the last show.[181] The tour went on to win Tour of the Year at the 44th American Music Awards.[182]

On April 16, 2016, Beyoncé released a teaser clip for a project called Lemonade. A one-hour film which aired on HBO on April 23, a corresponding album with the same title was released on the same day exclusively on Tidal.[183] Lemonade debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200, making Beyoncé the first act in Billboard history to have their first six studio albums debut atop the chart; she broke a record previously tied with DMX in 2013.[184] With all 12 tracks of Lemonade debuting on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, Beyoncé also became the first female act to chart 12 or more songs at the same time.[185] Additionally, Lemonade was streamed 115 million times through Tidal, setting a record for the most-streamed album in a single week by a female artist in history.[186] It was 2016’s third highest-selling album in the U.S. with 1.554 million copies sold in that time period within the country[187] as well as the best-selling album worldwide with global sales of 2.5 million throughout the year.[188] In June 2019, Lemonade was certified 3× Platinum, having sold up to 3 million album-equivalent units in the United States alone.[189]

Lemonade became her most critically acclaimed work to date, receiving universal acclaim according to Metacritic, a website collecting reviews from professional music critics.[190] Several music publications included the album among the best of 2016, including Rolling Stone, which listed Lemonade at number one.[191] The album’s visuals were nominated in 11 categories at the 2016 MTV Video Music Awards, the most ever received by Beyoncé in a single year, and went on to win 8 awards, including Video of the Year for «Formation».[192][193] The eight wins made Beyoncé the most-awarded artist in the history of the VMAs (24), surpassing Madonna (20).[194] Beyoncé occupied the sixth place for Time magazine’s 2016 Person of the Year.[195]

In January 2017, it was announced that Beyoncé would headline the Coachella Music and Arts Festival. This would make Beyoncé only the second female headliner of the festival since it was founded in 1999.[196] It was later announced on February 23, 2017, that Beyoncé would no longer be able to perform at the festival due to doctor’s concerns regarding her pregnancy. The festival owners announced that she will instead headline the 2018 festival.[197] Upon the announcement of Beyoncé’s departure from the festival lineup, ticket prices dropped by 12%.[198] At the 59th Grammy Awards in February 2017, Lemonade led the nominations with nine, including Album, Record, and Song of the Year for Lemonade and «Formation» respectively.[199] and ultimately won two, Best Urban Contemporary Album for Lemonade and Best Music Video for «Formation».[200] Adele, upon winning her Grammy for Album of the Year, stated Lemonade was monumental and more deserving.[201]

In September 2017, Beyoncé collaborated with J Balvin and Willy William, to release a remix of the song «Mi Gente». Beyoncé donated all proceeds from the song to hurricane charities for those affected by Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Irma in Texas, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean Islands.[202] On November 10, Eminem released «Walk on Water» featuring Beyoncé as the lead single from his album Revival. On November 30, Ed Sheeran announced that Beyoncé would feature on the remix to his song «Perfect».[203] «Perfect Duet» was released on December 1, 2017. The song reached number-one in the United States, becoming Beyoncé’s sixth song of her solo career to do so.[204]

On January 4, 2018, the music video of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s 4:44 collaboration, «Family Feud» was released.[205] It was directed by Ava DuVernay. On March 1, 2018, DJ Khaled released «Top Off» as the first single from his forthcoming album Father of Asahd featuring Beyoncé, husband Jay-Z, and Future.[206] On March 5, 2018, a joint tour with Knowles’s husband Jay-Z, was leaked on Facebook.[207] Information about the tour was later taken down. The couple announced the joint tour officially as On the Run II Tour on March 12[208] and simultaneously released a trailer for the tour on YouTube.[209]

On April 14, 2018, Beyoncé played the first of two weekends as the headlining act of the Coachella Music Festival. Her performance of April 14, attended by 125,000 festival-goers, was immediately praised, with multiple media outlets describing it as historic. The performance became the most-tweeted-about performance of weekend one, as well as the most-watched live Coachella performance and the most-watched live performance on YouTube of all time. The show paid tribute to black culture, specifically historically black colleges and universities and featured a live band with over 100 dancers. Destiny’s Child also reunited during the show.[210][211]

On June 6, 2018, Beyoncé and husband Jay-Z kicked-off the On the Run II Tour in Cardiff, United Kingdom. Ten days later, at their final London performance, the pair unveiled Everything Is Love, their joint studio album, credited under the name The Carters, and initially available exclusively on Tidal. The pair also released the video for the album’s lead single, «Apeshit», on Beyoncé’s official YouTube channel.[212][213] Everything Is Love received generally positive reviews,[214] and debuted at number two on the U.S. Billboard 200, with 123,000 album-equivalent units, of which 70,000 were pure album sales.[215] On December 2, 2018, Beyoncé alongside Jay-Z headlined the Global Citizen Festival: Mandela 100 which was held at FNB Stadium in Johannesburg, South Africa.[216] Their 2-hour performance had concepts similar to the On the Run II Tour and Beyoncé was praised for her outfits, which paid tribute to Africa’s diversity.[217]

2019–2021: Homecoming, The Lion King and Black Is King

Homecoming, a documentary and concert film focusing on Beyoncé’s historic 2018 Coachella performances, was released by Netflix on April 17, 2019.[218][219] The film was accompanied by the surprise live album Homecoming: The Live Album.[220] It was later reported that Beyoncé and Netflix had signed a $60 million deal to produce three different projects, one of which is Homecoming.[221] Homecoming received six nominations at the 71st Primetime Creative Arts Emmy Awards.[222]

Beyoncé starred as the voice of Nala in the remake The Lion King, which was released on July 19, 2019.[223] Beyoncé is featured on the film’s soundtrack, released on July 11, 2019, with a remake of the song «Can You Feel the Love Tonight» alongside Donald Glover, Billy Eichner and Seth Rogen, which was originally composed by Elton John.[224] Additionally, an original song from the film by Beyoncé, «Spirit», was released as the lead single from both the soundtrack and The Lion King: The Gift – a companion album released alongside the film, produced and curated by Beyoncé.[225][226] Beyoncé called The Lion King: The Gift a «sonic cinema». She also stated that the album is influenced by everything from R&B, pop, hip hop and Afro Beat.[225] The songs were additionally produced by African producers, which Beyoncé said was because «authenticity and heart were important to [her]», since the film is set in Africa.[225] In September of the same year, a documentary chronicling the development, production and early music video filming of The Lion King: The Gift entitled «Beyoncé Presents: Making The Gift» was aired on ABC.

On April 29, 2020, Beyoncé was featured on the remix of Megan Thee Stallion’s song «Savage», marking her first material of music for the year.[227] The song peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100, marking Beyoncé’s eleventh song to do so across all acts.[228] On June 19, 2020, Beyoncé released the nonprofit charity single «Black Parade».[229] On June 23, she followed up the release of its studio version with an a cappella version exclusively on Tidal.[230] Black Is King, a visual album based on the music of The Lion King: The Gift, premiered globally on Disney+ on July 31, 2020. Produced by Disney and Parkwood Entertainment, the film was written, directed and executive produced by Beyoncé. The film was described by Disney as «a celebratory memoir for the world on the Black experience».[231] Beyoncé received the most nominations (9) at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards and the most awards (4), which made her the most-awarded singer, most-awarded female artist, and second-most-awarded artist in Grammy history.[232]

Beyoncé wrote and recorded a song titled «Be Alive» for the biographical drama film King Richard.[233] She received her first Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song at the 94th Academy Awards for the song, alongside co-writer DIXSON.[234]

2022: Renaissance

On June 9, 2022, Beyoncé removed her profile pictures across various social media platforms causing speculation that she would be releasing new music.[235] Days later, Beyoncé caused further speculation via her nonprofit BeyGood’s Twitter account hinting at her upcoming seventh studio album.[236] On June 15, 2022, Beyoncé officially announced her seventh studio album, titled Renaissance. The album was released on July 29, 2022.[237][238] The first single from Renaissance, «Break My Soul», was released on June 20, 2022.[239] The song became Beyoncé’s 20th top ten single on the Billboard Hot 100, and in doing so, Beyoncé joined Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson as the only artists in Hot 100 history to achieve at least twenty top tens as a solo artist and ten as a member of a group.[240] Upon release, Renaissance received universal acclaim from critics.[241] Renaissance debuted at number one on the Billboard 200 chart, and in doing so, Beyoncé became the first female artist to have her first seven studio albums debut at number one in the United States.[12] «Break My Soul» concurrently rose to number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming the twelfth song to do so across her career discography.[242]

Artistry

Voice and musical style

With «Single Ladies», clearly I’d just gotten married, and people want to get married every day – then there was the whole Justin Timberlake thing [recreating the video] on Saturday Night Live, and it was also the year YouTube blew up. With «Irreplaceable», the aggressive lyrics, the acoustic guitar, and the 808 drum machine – those things don’t typically go together, and it sounded fresh. «Crazy in Love» was another one of those classic moments in pop culture that none of us expected. I asked Jay to get on the song the night before I had to turn my album in – thank God he did. It still never gets old, no matter how many times I sing it.

—Beyoncé[243]

Beyoncé’s voice type is classified as Coloratura mezzo-soprano.[244][245] Jody Rosen highlights her tone and timbre as particularly distinctive, describing her voice as «one of the most compelling instruments in popular music».[246] Her vocal abilities mean she is identified as the centerpiece of Destiny’s Child.[247] Jon Pareles of The New York Times commented that her voice is «velvety yet tart, with an insistent flutter and reserves of soul belting».[248] Rosen notes that the hip hop era highly influenced Beyoncé’s unique rhythmic vocal style, but also finds her quite traditionalist in her use of balladry, gospel and falsetto.[246] Other critics praise her range and power, with Chris Richards of The Washington Post saying she was «capable of punctuating any beat with goose-bump-inducing whispers or full-bore diva-roars.»[249] On the 2023 Rolling Stone’s list of the 200 Greatest Singers of all time, Beyoncé ranked at number 8.[250]

Beyoncé’s music is generally R&B,[251][252] pop[251][253] and hip hop[254] but she also incorporates soul and funk into her songs. 4 demonstrated Beyoncé’s exploration of 1990s-style R&B, as well as further use of soul and hip hop than compared to previous releases.[243] While she almost exclusively releases English songs, Beyoncé recorded several Spanish songs for Irreemplazable (re-recordings of songs from B’Day for a Spanish-language audience), and the re-release of B’Day. To record these, Beyoncé was coached phonetically by American record producer Rudy Perez.[255]

Songwriting

Beyoncé has received co-writing credits for most of her songs.[256] In regards to the way she approaches collaborative songwriting, Beyoncé explained: «I love being around great writers because I’m finding that a lot of the things I want to say, I don’t articulate as good as maybe Amanda Ghost, so I want to keep collaborating with writers, and I love classics and I want to make sure years from now the song is still something that’s relevant.»[257] Her early songs with Destiny’s Child were personally driven and female-empowerment themed compositions like «Independent Women» and «Survivor», but after the start of her relationship with Jay-Z, she transitioned to more man-tending anthems such as «Cater 2 U».[258]

In 2001, she became the first Black woman and second female lyricist to win the Pop Songwriter of the Year award at the ASCAP Pop Music Awards.[15][259] Beyoncé was the third woman to have writing credits on three number-one songs («Irreplaceable», «Grillz» and «Check on It») in the same year, after Carole King in 1971 and Mariah Carey in 1991. She is tied with American lyricist Diane Warren at third with nine songwriting credits on number-one singles.[260] The latter wrote her 9/11-motivated song «I Was Here» for 4.[261] In May 2011, Billboard magazine listed Beyoncé at number 17 on their list of the Top 20 Hot 100 Songwriters for having co-written eight singles that hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. She was one of only three women on that list, along with Alicia Keys and Taylor Swift.[262]

Influences

Beyoncé names Michael Jackson as her major musical influence.[263] Aged five, Beyoncé attended her first ever concert where Jackson performed and she claims to have realized her purpose.[264] When she presented him with a tribute award at the World Music Awards in 2006, Beyoncé said, «if it wasn’t for Michael Jackson, I would never ever have performed.»[265] Beyoncé was heavily influenced by Tina Turner, who she said «Tina Turner is someone that I admire, because she made her strength feminine and sexy».[266] She admires Diana Ross as an «all-around entertainer»,[267] and Whitney Houston, who she said «inspired me to get up there and do what she did.»[268] Beyoncé cited Madonna as an influence «not only for her musical style, but also for her business sense»,[269] saying that she wanted to «follow in the footsteps of Madonna and be a powerhouse and have my own empire.»[270] She also credits Mariah Carey’s singing and her song «Vision of Love» as influencing her to begin practicing vocal runs as a child.[271][272] Her other musical influences include Prince,[273] Shakira,[274] Lauryn Hill,[267] Sade Adu,[275] Donna Summer,[276] Mary J. Blige,[277] Anita Baker, and Toni Braxton.[267]

The feminism and female empowerment themes on Beyoncé’s second solo album B’Day were inspired by her role in Dreamgirls[278] and by singer Josephine Baker.[279] Beyoncé paid homage to Baker by performing «Déjà Vu» at the 2006 Fashion Rocks concert wearing Baker’s trademark mini-hula skirt embellished with fake bananas.[280] Beyoncé’s third solo album, I Am… Sasha Fierce, was inspired by Jay-Z and especially by Etta James, whose «boldness» inspired Beyoncé to explore other musical genres and styles.[281] Her fourth solo album, 4, was inspired by Fela Kuti, 1990s R&B, Earth, Wind & Fire, DeBarge, Lionel Richie, Teena Marie, The Jackson 5, New Edition, Adele, Florence and the Machine, and Prince.[243]

Beyoncé has stated that she is personally inspired by Michelle Obama (the 44th First Lady of the United States), saying «she proves you can do it all»,[282] and has described Oprah Winfrey as «the definition of inspiration and a strong woman.»[267] She has also discussed how Jay-Z is a continuing inspiration to her, both with what she describes as his lyrical genius and in the obstacles he has overcome in his life.[283] Beyoncé has expressed admiration for the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, posting in a letter «what I find in the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, I search for in every day in music … he is lyrical and raw».[284][285] Beyoncé also cited Cher as a fashion inspiration.[286]

Music videos and stage

In 2006, Beyoncé introduced her all-female tour band Suga Mama (also the name of a song on B’Day) which includes bassists, drummers, guitarists, horn players, keyboardists and percussionists.[287] Her background singers, The Mamas, consist of Montina Cooper-Donnell, Crystal Collins and Tiffany Moniqué Riddick. They made their debut appearance at the 2006 BET Awards and re-appeared in the music videos for «Irreplaceable» and «Green Light».[255] The band have supported Beyoncé in most subsequent live performances, including her 2007 concert tour The Beyoncé Experience, I Am… World Tour (2009–2010), The Mrs. Carter Show World Tour (2013–2014) and The Formation World Tour (2016).

Beyoncé has received praise for her stage presence and voice during live performances. Jarett Wieselman of the New York Post placed her at number one on her list of the Five Best Singer/Dancers.[288] According to Barbara Ellen of The Guardian Beyoncé is the most in-charge female artist she’s seen onstage,[289] while Alice Jones of The Independent wrote she «takes her role as entertainer so seriously she’s almost too good.»[290] The ex-President of Def Jam L.A. Reid has described Beyoncé as the greatest entertainer alive.[291] Jim Farber of the Daily News and Stephanie Classen of The StarPhoenix both praised her strong voice and her stage presence.[292][293] Beyoncé’s stage outfits have been met with criticism from many countries, such as Malaysia, where she has postponed or cancelled performances due to the country’s strict laws banning revealing costumes.[294]

Beyoncé has worked with numerous directors for her music videos throughout her career, including Melina Matsoukas, Jonas Åkerlund, and Jake Nava. Bill Condon, director of Beauty and the Beast, stated that the Lemonade visuals in particular served as inspiration for his film, commenting, «You look at Beyoncé’s brilliant movie Lemonade, this genre is taking on so many different forms … I do think that this very old-school break-out-into-song traditional musical is something that people understand again and really want.»[295]

Alter ego

Described as being «sexy, seductive and provocative» when performing on stage, Beyoncé has said that she originally created the alter ego «Sasha Fierce» to keep that stage persona separate from who she really is. She described Sasha as being «too aggressive, too strong, too sassy [and] too sexy», stating, «I’m not like her in real life at all.»[47] Sasha was conceived during the making of «Crazy in Love», and Beyoncé introduced her with the release of her 2008 album, I Am… Sasha Fierce. In February 2010, she announced in an interview with Allure magazine that she was comfortable enough with herself to no longer need Sasha Fierce.[296] However, Beyoncé announced in May 2012 that she would bring her back for her Revel Presents: Beyoncé Live shows later that month.[297]

Public image

Beyoncé at the premiere of her 2006 film Dreamgirls

Beyoncé has been described as having a wide-ranging sex appeal, with music journalist Touré writing that since the release of Dangerously in Love, she has «become a crossover sex symbol».[298] Offstage Beyoncé says that while she likes to dress sexily, her onstage dress «is absolutely for the stage».[299] Due to her curves and the term’s catchiness, in the 2000s, the media often used the term «bootylicious» (a portmanteau of the words «booty» and «delicious») to describe Beyoncé,[300][301] the term popularized by Destiny’s Child’s single of the same name. In 2006, it was added to the Oxford English Dictionary.[302]

In September 2010, Beyoncé made her runway modelling debut at Tom Ford’s Spring/Summer 2011 fashion show.[303] She was named the «World’s Most Beautiful Woman» by People[304] and the «Hottest Female Singer of All Time» by Complex in 2012.[305] In January 2013, GQ placed her on its cover, featuring her atop its «100 Sexiest Women of the 21st Century» list.[306][307] VH1 listed her at number 1 on its 100 Sexiest Artists list.[308] Several wax figures of Beyoncé are found at Madame Tussauds Wax Museums in major cities around the world, including New York,[309] Washington, D.C.,[310] Amsterdam,[311] Bangkok,[312] Hollywood[313] and Sydney.[314]

According to Italian fashion designer Roberto Cavalli, Beyoncé uses different fashion styles to work with her music while performing.[315] Her mother co-wrote a book, published in 2002, titled Destiny’s Style,[316] an account of how fashion affected the trio’s success.[317] The B’Day Anthology Video Album showed many instances of fashion-oriented footage, depicting classic to contemporary wardrobe styles.[318] In 2007, Beyoncé was featured on the cover of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, becoming the second African American woman after Tyra Banks,[319] and People magazine recognized Beyoncé as the best-dressed celebrity.[320]

Beyoncé has been named «Queen Bey» from publications over the years. The term is a reference to the common phrase «queen bee», a term used for the leader of a group of females. The nickname also refers to the queen of a beehive, with her fan base being named «The BeyHive». The BeyHive was previously titled «The Beyontourage», (a portmanteau of Beyoncé and entourage), but was changed after online petitions on Twitter and online news reports during competitions.[321] The BeyHive has been named one of the most loyal and defensive fan bases and has achieved notoriety for being fiercely protective of Beyoncé.[322]

In 2006, the animal rights organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), criticized Beyoncé for wearing and using fur in her clothing line House of Deréon.[323] In 2011, she appeared on the cover of French fashion magazine L’Officiel, in «blackface» and tribal makeup that drew criticism from the media. A statement released from a spokesperson for the magazine said that Beyoncé’s look was «far from the glamorous Sasha Fierce» and that it was «a return to her African roots».[324]

Beyoncé’s lighter skin color and costuming has drawn criticism from some in the African-American community.[325] Emmett Price, a professor of music at Northeastern University, wrote in 2007 that he thinks race plays a role in many of these criticisms, saying white celebrities who dress similarly do not attract as many comments.[325] In 2008, L’Oréal was accused of whitening her skin in their Feria hair color advertisements, responding that «it is categorically untrue»,[326][327] and in 2013, Beyoncé herself criticized H&M for their proposed «retouching» of promotional images of her, and according to Vogue requested that only «natural pictures be used».[328]

Beyoncé has been a vocal advocate for the Black Lives Matter movement. The release of «Formation» on February 6, 2016, saw her celebrate her heritage, with the song’s music video featuring pro-black imagery and most notably a shot of wall graffiti that says «Stop shooting us». The day after the song’s release she performed it at the 2016 Super Bowl halftime show with back up dancers dressed to represent the Black Panther Party. This incited criticism from politicians and police officers, with some police boycotting Beyoncé’s then upcoming Formation World Tour.[329] Beyoncé responded to the backlash by releasing tour merchandise that said «Boycott Beyoncé»,[330][331][332] and later clarified her sentiment, saying: «Anyone who perceives my message as anti-police is completely mistaken. I have so much admiration and respect for officers and the families of officers who sacrifice themselves to keep us safe,» Beyoncé said. «But let’s be clear: I am against police brutality and injustice. Those are two separate things.»[333]

Personal life

Marriage and children

Beyoncé started a relationship with Jay-Z after their collaboration on «’03 Bonnie & Clyde»,[334] which appeared on his seventh album The Blueprint 2: The Gift & The Curse (2002).[335] Beyoncé appeared as Jay-Z’s girlfriend in the music video for the song, fueling speculation about their relationship.[336] On April 4, 2008, Beyoncé and Jay-Z married without publicity.[337] As of April 2014, the couple had sold a combined 300 million records together.[166] They are known for their private relationship, although they have appeared to become more relaxed since 2013.[338] Both have acknowledged difficulty that arose in their marriage after Jay-Z had an affair.[339][340]

Beyoncé miscarried around 2010 or 2011, describing it as «the saddest thing» she had ever endured.[341] She returned to the studio and wrote music to cope with the loss. In April 2011, Beyoncé and Jay-Z traveled to Paris to shoot the album cover for 4, and she unexpectedly became pregnant in Paris.[342] In August, the couple attended the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards, at which Beyoncé performed «Love on Top» and ended the performance by revealing she was pregnant.[343] Her appearance helped that year’s MTV Video Music Awards become the most-watched broadcast in MTV history, pulling in 12.4 million viewers;[344] the announcement was listed in Guinness World Records for «most tweets per second recorded for a single event» on Twitter,[345] receiving 8,868 tweets per second[346] and «Beyonce pregnant» was the most Googled phrase the week of August 29, 2011.[347] On January 7, 2012, Beyoncé gave birth to a daughter, Blue Ivy, at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City.[348]

Following the release of Lemonade, which included the single «Sorry», in 2016, speculations arose about Jay-Z’s alleged infidelity with a mistress referred to as «Becky». Jon Pareles in The New York Times pointed out that many of the accusations were «aimed specifically and recognizably» at him.[349] Similarly, Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone magazine noted the lines «Suck on my balls, I’ve had enough» were an «unmistakable hint» that the lyrics revolve around Jay-Z.[350]

On February 1, 2017, she revealed on her Instagram account that she was expecting twins. Her announcement gained over 6.3 million likes within eight hours, breaking the world record for the most liked image on the website at the time.[351] On July 13, 2017, Beyoncé uploaded the first image of herself and the twins onto her Instagram account, confirming their birth date as a month prior, on June 13, 2017,[352] with the post becoming the second most liked on Instagram, behind her own pregnancy announcement.[353] The twins, a daughter named Rumi and a son named Sir, were born at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in California. She wrote of her pregnancy and its aftermath in the September 2018 issue of Vogue, in which she had full control of the cover, shot at Hammerwood Park by photographer Tyler Mitchell.[354][355]

Activism

Beyoncé performed «America the Beautiful» at President Barack Obama’s 2009 presidential inauguration, as well as «At Last» during the first inaugural dance at the Neighborhood Ball two days later.[356] The couple held a fundraiser at Jay-Z’s 40/40 Club in Manhattan for President Obama’s 2012 presidential campaign[357] which raised $4 million.[358] In the 2012 presidential election, the singer voted for President Obama.[359] She performed the American national anthem «The Star-Spangled Banner» at his second inauguration in January 2013.[149]

The Washington Post reported in May 2015, that Beyoncé attended a major celebrity fundraiser for 2016 presidential nominee Hillary Clinton.[360] She also headlined for Clinton in a concert held the weekend before Election Day the next year. In this performance, Beyoncé and her entourage of backup dancers wore pantsuits; a clear allusion to Clinton’s frequent dress-of-choice. The backup dancers also wore «I’m with her» tee shirts, the campaign slogan for Clinton. In a brief speech at this performance Beyoncé said, «I want my daughter to grow up seeing a woman lead our country and knowing that her possibilities are limitless.»[361] She endorsed the bid of Beto O’Rourke during the 2018 United States Senate election in Texas.[362]

Beyoncé has conducted several fundraising and donation campaigns during her tours

In 2013, Beyoncé stated in an interview in Vogue that she considered herself to be «a modern-day feminist».[363] She would later align herself more publicly with the movement, sampling «We should all be feminists», a speech delivered by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at a TEDx talk in April 2013, in her song «Flawless», released later that year.[364] The next year she performed live at the MTV Video Awards in front a giant backdrop reading «Feminist».[365] Her self-identification incited a circulation of opinions and debate about whether her feminism is aligned with older, more established feminist ideals. Annie Lennox, celebrated artist and feminist advocate, referred to Beyoncé’s use of her word feminist as ‘feminist lite’.[366] bell hooks critiqued Beyoncé, referring to her as a «terrorist» towards feminism, harmfully impacting her audience of young girls.[367] Adichie responded with «her type of feminism is not mine, as it is the kind that, at the same time, gives quite a lot of space to the necessity of men.»[368] Adichie expands upon what ‘feminist lite’ means to her, referring that «more troubling is the idea, in Feminism Lite, that men are naturally superior but should be expected to «treat women well» and «we judge powerful women more harshly than we judge powerful men. And Feminism Lite enables this.»[369] Beyoncé responded about her intent by utilizing the definition of feminist with her platform was to «give clarity to the true meaning» behind it.[370] She says to understand what being a feminist is, «it’s very simple. It’s someone who believes in equal rights for men and women.»[370] She advocated to provide equal opportunities for young boys and girls, men and women must begin to understand the double standards that remain persistent in our societies and the issue must be illuminated in effort to start making changes.[370]

She has also contributed to the Ban Bossy campaign, which uses TV and social media to encourage leadership in girls.[371] Following Beyoncé’s public identification as a feminist, the sexualized nature of her performances and the fact that she championed her marriage was questioned.[372]

In December 2012, Beyoncé along with a variety of other celebrities teamed up and produced a video campaign for «Demand A Plan», a bipartisan effort by a group of 950 U.S. mayors and others[373] designed to influence the federal government into rethinking its gun control laws, following the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.[374] Beyoncé publicly endorsed same-sex marriage on March 26, 2013, after the Supreme Court debate on California’s Proposition 8.[375] She spoke against North Carolina’s Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act, a bill passed (and later repealed) that discriminated against the LGBT community in public places in a statement during her concert in Raleigh as part of the Formation World Tour in 2016.[376] She has also condemned police brutality against black Americans. She and Jay-Z attended a rally in 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin.[377] The film for her sixth album Lemonade included the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner, holding pictures of their sons in the video for «Freedom».[378] In a 2016 interview with Elle, Beyoncé responded to the controversy surrounding her song «Formation» which was perceived to be critical of the police. She clarified, «I am against police brutality and injustice. Those are two separate things. If celebrating my roots and culture during Black History Month made anyone uncomfortable, those feelings were there long before a video and long before me».[379]

In February 2017, Beyoncé spoke out against the withdrawal of protections for transgender students in public schools by Donald Trump’s presidential administration. Posting a link to the 100 Days of Kindness campaign on her Facebook page, Beyoncé voiced her support for transgender youth and joined a roster of celebrities who spoke out against Trump’s decision.[380]

In November 2017, Beyoncé presented Colin Kaepernick with the 2017 Sports Illustrated Muhammad Ali Legacy Award, stating, «Thank you for your selfless heart and your conviction, thank you for your personal sacrifice», and that «Colin took action with no fear of consequence … To change perception, to change the way we treat each other, especially people of color. We’re still waiting for the world to catch up.» Muhammad Ali was heavily penalized in his career for protesting the status quo of US civil rights through opposition to the Vietnam War, by refusing to serve in the military. 40 years later, Kaepernick had already lost one professional year due to taking a much quieter and legal stand «for people that are oppressed».[381]

Wealth

Forbes magazine began reporting on Beyoncé’s earnings in 2008, calculating that the $80 million earned between June 2007 to June 2008, for her music, tour, films and clothing line made her the world’s best-paid music personality at the time, above Madonna and Celine Dion.[382][383] It placed her fourth on the Celebrity 100 list in 2009[384]

and ninth on the «Most Powerful Women in the World» list in 2010.[385] The following year, the magazine placed her eighth on the «Best-Paid Celebrities Under 30» list, having earned $35 million in the past year for her clothing line and endorsement deals. In 2012, Forbes placed Beyoncé at number 16 on the Celebrity 100 list, twelve places lower than three years ago yet still having earned $40 million in the past year for her album 4, clothing line and endorsement deals.[386][387] In the same year, Beyoncé and Jay-Z placed at number one on the «World’s Highest-Paid Celebrity Couples», for collectively earning $78 million.[388] The couple made it into the previous year’s Guinness World Records as the «highest-earning power couple» for collectively earning $122 million in 2009.[389] For the years 2009 to 2011, Beyoncé earned an average of $70 million per year, and earned $40 million in 2012.[390] In 2013, Beyoncé’s endorsements of Pepsi and H&M made her and Jay-Z the world’s first billion dollar couple in the music industry.[391] That year, Beyoncé was published as the fourth most-powerful celebrity in the Forbes rankings.[392]

MTV estimated that by the end of 2014, Beyoncé would become the highest-paid Black musician in history;[393] this became the case in April 2014.[394] In June 2014, Beyoncé ranked at number one on the Forbes Celebrity 100 list, earning an estimated $115 million throughout June 2013 – June 2014. This in turn was the first time she had topped the Celebrity 100 list as well as being her highest yearly earnings to date.[395] In 2016, Beyoncé ranked at number 34 on the Celebrity 100 list with earnings of $54 million. She and Jay-Z also topped the highest paid celebrity couple list, with combined earnings of $107.5 million.[396] As of 2018, Forbes calculated her net worth to be $355 million, and in June of the same year, ranked her as the 35th highest earning celebrity with annual earnings of $60 million. This tied Beyoncé with Madonna as the only two female artists to earn more than $100 million within a single year twice.[397][398] As a couple, Beyoncé and Jay-Z have a combined net worth of $1.16 billion.[399] In July 2017, Billboard announced that Beyoncé was the highest paid musician of 2016, with an estimated total of $62.1 million.[400]

Legacy

Beyoncé performing during her I Am… World Tour in 2009

Beyoncé’s success has led to her becoming a cultural icon and earning her the nickname «Queen Bey».[7] Constance Grady wrote for Vox, «The transformation of Beyoncé from well-liked pop star to cultural icon came in three phases, punctuated by the self-titled Beyoncé album of 2013, 2016’s Lemonade, and 2018’s Homecoming concert at Coachella.»[401] In The New Yorker, music critic Jody Rosen described Beyoncé as «the most important and compelling popular musician of the twenty-first century … the result, the logical end point, of a century-plus of pop.»[402] Author James Clear, in his book Atomic Habits (2018), draws a parallel between the singer’s success and the dramatic transformations in modern society: «In the last one hundred years, we have seen the rise of the car, the airplane, the television, the personal computer, the internet, the smartphone, and Beyoncé.»[403] The Observer named her Artist of the Decade (2000s) in 2009.[404]

Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Alex Suskind noticed how Beyoncé was the decade’s (2010s) defining pop star, stating that «no one dominated music in the 2010s like Queen Bey», explaining that her «songs, album rollouts, stage presence, social justice initiatives, and disruptive public relations strategy have influenced the way we’ve viewed music since 2010.»[405] British publication NME also shared similar thoughts on her impact in the 2010s, including Beyoncé on their list of the «10 Artists Who Defined The Decade».[406] In 2018, Rolling Stone included her on its Millennial 100 list.[407]

Music critics have often credited Beyoncé with the invention of the staccato rap-singing style that has since dominated pop, R&B and rap music. Lakin Starling of The Fader wrote that Beyoncé’s innovative implementation of the delivery style on Destiny’s Child’s 1999 album The Writing’s on the Wall invented a new form of R&B.[408] Beyoncé’s new style subsequently changed the nature of music, revolutionizing both singing in urban music and rapping in pop music, and becoming the dominant sound of both genres.[409][410] The style helped to redefine both the breadth of commercial R&B and the sound of hip hop, with artists such as Kanye West and Drake implementing Beyoncé’s cadence in the late 2000s and early 2010s.[411] The staccato rap-singing style continued to be used in the music industry in the late 2010s and early 2020s; Aaron Williams of Uproxx described Beyoncé as the «primary pioneer» of the rapping style that dominates the music industry today, with many contemporary rappers implementing Beyoncé’s rap-singing.[412] Michael Eric Dyson agrees, saying that Beyoncé «changed the whole genre» and has become the «godmother» of mumble rappers, who use the staccato rap-singing cadence. Dyson added: «She doesn’t get credit for the remarkable way in which she changed the musical vocabulary of contemporary art.»[413]

Beyoncé has been credited with reviving the album as an art form in an era dominated by singles and streaming. This started with her 2011 album 4; while mainstream R&B artists were forgoing albums-led R&B in favor of singles-led EDM, Beyoncé aimed to place the focus back on albums as an artform and re-establish R&B as a mainstream concern.[414] This remained a focus of Beyoncé’s, and in 2013, she made her eponymous album only available to purchase as a full album on iTunes, rather than being able to purchase individual tracks or consume the album via streaming. Kaitlin Menza of Marie Claire wrote that this made listeners «experience the album as one whole sonic experience, the way people used to, noting the musical and lyrical themes».[415] Jamieson Cox for The Verge described how Beyoncé’s 2013 album initiated a gradual trend of albums becoming more cohesive and self-referential, and this phenomenon reached its endpoint with Lemonade, which set «a new standard for pop storytelling at the highest possible scale».[416] Megan Carpentier of The Guardian wrote that with Lemonade, Beyoncé has «almost revived the album format» by releasing an album that can only be listened to in its entirety.[417] Myf Warhurst on Double J‘s «Lunch With Myf» explained that while most artists’ albums consist of a few singles plus filler songs, Beyoncé «brought the album back», changing the art form of the album «to a narrative with an arc and a story and you have to listen to the entire thing to get the concept».[418]

She is known for coining popular phrases such as «put a ring on it», a euphemism for marriage proposal, «I woke up like this», which started a trend of posting morning selfies with the hashtag #iwokeuplikethis, and «boy, bye», which was used as part of the Democratic National Committee’s campaign for the 2020 election.[419][420] Similarly, she also came up with the phrase «visual album» following the release of her fifth studio album, which had a video for every song. This has been recreated by many other artists since, such as Frank Ocean and Melanie Martinez.[421] The album also popularized surprise releases, with many artists releasing songs, videos or albums with no prior announcement, such as Taylor Swift, Nicki Minaj, Eminem, Frank Ocean, Jay-Z and Drake.[422]

In January 2012, research scientist Bryan Lessard named Scaptia beyonceae, a species of horse-fly found in Northern Queensland, Australia after Beyoncé due to the fly’s unique golden hairs on its abdomen.[423] In 2018, the City of Columbia, South Carolina declared August 21 the Beyoncé Knowles-Carter Day in the city after presenting her with the keys to Columbia.[424]

Influence on other artists

Various recording artists and celebrities have cited Beyoncé as their influence. Lady Gaga explained how Beyoncé gave her the determination to become a musician, recalling seeing her in a Destiny’s Child music video and saying: «Oh, she’s a star. I want that.»[425] Rihanna was similarly inspired to start her singing career after watching Beyoncé, telling etalk that after Beyoncé released Dangerously In Love (2003), «I was like ‘wow, I want to be just like that.’ She’s huge and just an inspiration.»[426] Lizzo was also first inspired by Beyoncé to start singing after watching her perform at a Destiny’s Child concert.[427] Lizzo also taught herself to sing by copying Beyoncé’s B’Day (2006).[428] Similarly, Ariana Grande said she learned to sing by mimicking Beyoncé.[429] Adele cited Beyoncé as her inspiration and favorite artist, telling Vogue: «She’s been a huge and constant part of my life as an artist since I was about ten or eleven … I think she’s really inspiring. She’s beautiful. She’s ridiculously talented, and she is one of the kindest people I’ve ever met … She makes me want to do things with my life.»[430] Both Paul McCartney and Garth Brooks said they watch Beyoncé’s performances to get inspiration for their own shows, with Brooks saying that when watching one of her performances, «take out your notebook and take notes. No matter how long you’ve been on the stage – take notes on that one.»[431][432] Other artists to cite influence from Beyoncé include Britney Spears,[433][434] Little Mix,[435] Sam Smith,[436] Nicki Minaj,[437] Cardi B,[438] Anitta,[439] Ava Max,[440] Tini Stoessel,[441] Christina Aguilera,[442] Dami Im[443] Azealia Banks,[444] Doja Cat,[445] Kendrick Lamar,[446] Kesha,[447] Megan Thee Stallion,[448] Normani,[449] Camila Cabello,[450] Dua Lipa,[451] Jazmine Sullivan,[452] Rosalía,[453] SZA,[454] Tinashe,[455] Zara Larsson,[456] Addison Rae,[457] Alexandra Burke,[458] Alexis Jordan,[459] Amber Riley,[460] Bebe Rexha,[461] Brandy,[462] Bridgit Mendler,[463] Chris Martin,[464] Ciara,[465] Demi Lovato,[466] Ellie Goulding,[467] Faith Hill,[468] Fergie,[469] Gal Gadot,[470] Grimes,[471] Gwyneth Paltrow,[472] Haim,[473] Harry Styles,[474] Hayley Williams,[475] J Balvin,[476] Jess Glynne,[477] Jessie J,[478] Jessie Ware,[479][480] JoJo,[481] Kelly Rowland,[482] Kim Petras,[483] Leona Lewis,[484] Meghan Trainor,[485] Miley Cyrus,[486] Miranda Lambert,[487] Nicole Scherzinger,[488] One Direction,[489] Rina Sawayama,[490] Rita Ora,[491] Rosalía,[492] Selena Gomez,[493] Stormzy,[494] Sevyn Streeter,[495] Tori Kelly,[496] Whitney Houston,[497] and Zendaya.[498]

Achievements

Beyoncé has received numerous awards, and is the most-awarded female artist of all time.[499] Having sold over 200 million records worldwide (a further 60 million additionally with Destiny’s Child), Beyoncé is one of the best-selling music artists of all time.[500] The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) listed Beyoncé as the top certified artist of the 2000s decade, with a total of 64 certifications.[501][502] Her songs «Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)», «Halo», and «Irreplaceable» are some of the best-selling singles of all time worldwide. In 2009, Billboard named her the Top Female Artist and Top Radio Songs Artist of the Decade.[503][504][505] In 2010, Billboard named her in their Top 50 R&B/Hip-Hop Artists of the Past 25 Years list at number 15.[506] In 2012, VH1 ranked her third on their list of the «100 Greatest Women in Music», behind Mariah Carey and Madonna.[507] In 2002, she received Songwriter of the Year from American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers becoming the First African American woman to win the award. In 2004 and 2019, she received NAACP Image Award for Entertainer of the Year and the Soul Train Music Award for Sammy Davis Jr. – Entertainer of the Year.

In 2005, she also received APEX Award at the Trumpet Award honoring achievements of Black African Americans. In 2007, Beyoncé received the International Artist of Excellence award by the American Music Awards. She also received Honorary Otto at the Bravo Otto. The following year, she received the Legend Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Arts at the World Music Awards and Career Achievement Award at the LOS40 Music Awards. In 2010, she received Award of Honor for Artist of the Decade at the NRJ Music Award and at the 2011 Billboard Music Awards, Beyoncé received the inaugural Billboard Millennium Award. Beyoncé received the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards and was honored as Honorary Mother of the Year at the Australian Mother of the Year Award in Barnardo’s Australia for her Humanitarian Effort in the region and the Council of Fashion Designers of America Fashion Icon Award in 2016. In 2019, alongside Jay-Z, she received GLAAD Vanguard Award that is presented to a member of the entertainment community who does not identify as LGBT but who has made a significant difference in promoting equal rights for LGBT people. In 2020, she was awarded the BET Humanitarian Award. Consequence of Sound named her the 30th best singer of all time.[508]

Beyoncé has won 28 Grammy Awards, both as a solo artist and member of Destiny’s Child and The Carters, making her the most honored singer, male or female, by the Grammys.[509][510] She is also the most nominated artist in Grammy Award history with a total of 88 nominations. «Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)» won Song of the Year in 2010 while «Say My Name»,[37] «Crazy in Love» and «Drunk in Love» have each won Best R&B Song. Dangerously in Love, B’Day and I Am… Sasha Fierce have all won Best Contemporary R&B Album, while Lemonade has won Best Urban Contemporary Album. Beyoncé set the record for the most Grammy awards won by a female artist in one night in 2010 when she won six awards, breaking the tie she previously held with Alicia Keys, Norah Jones, Alison Krauss, and Amy Winehouse, with Adele equaling this in 2012.[511]

Beyoncé has won 29 MTV Video Music Awards, making her the most-awarded artist in Video Music Award history. She won two awards each with The Carters and Destiny’s Child making her lifetime total of 29 VMAs. «Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)» and «Formation» won Video of the Year in 2009 and 2016 respectively. Beyoncé tied the record set by Lady Gaga in 2010 for the most VMAs won in one night for a female artist with eight in 2016.[194] She is also the most-awarded and nominated artist in BET Award history, winning 29 awards from a total of 60 nominations,[512] the most-awarded person at the Soul Train Music Awards with 17 awards as a solo artist, and the most-awarded person at the NAACP Image Awards with 24 awards as a solo artist.

Additionally, Beyoncé is the most-awarded artist at the NAACP Image Awards with 22 awards,[513] the BET Awards with 32 awards,[514] and the Soul Train Music Awards with 21 awards.

Following her role in Dreamgirls, Beyoncé was nominated for Best Original Song for «Listen» and Best Actress at the Golden Globe Awards,[515] and Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture at the NAACP Image Awards.[516] Beyoncé won two awards at the Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards 2006; Best Song for «Listen» and Best Original Soundtrack for Dreamgirls: Music from the Motion Picture.[517] According to Fuse in 2014, Beyoncé is the second-most award-winning artist of all time, after Michael Jackson.[518][519] Lemonade won a Peabody Award in 2017.[520] In 2022, «Be Alive» was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song,[521] the Critics’ Choice Movie Award for Best Song,[522] and the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song.[523]

She was named on the 2016 BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Power List as one of seven women judged to have had the biggest impact on women’s lives over the past 70 years, alongside Margaret Thatcher, Barbara Castle, Helen Brook, Germaine Greer, Jayaben Desai and Bridget Jones,[524] She was named the Most Powerful Woman in Music on the same list in 2020.[525] In the same year, Billboard named her with Destiny’s Child the third Greatest Music Video artists of all time, behind Madonna and Michael Jackson.[526]

On June 16, 2021, Beyoncé was among several celebrities at the Pollstar Awards where she won the award of «top touring artist» of the decade (2010s).[527] On June 17, 2021, Beyoncé was inducted into the Black Music & Entertainment Walk of Fame as a member of the inaugural class.[528]

Business and ventures