Как правильно пишется слово «бизнес-модель»

би́знес-моде́ль

би́знес-моде́ль, -и

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: рюшка — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «бизнес-модель»

Предложения со словом «бизнес-модель»

- Появление новой бизнес-модели может затронуть компании и в других отраслях.

- Успешная инновационная бизнес-модель создаёт стоимоссть для клиентов и обеспечивает получение стоимости компанией.

- Поддерживающая инновация связана с исследованием возможностей, которые развивают существующие бизнес-модели компании, укрепляют их и сохраняют.

- (все предложения)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Бизнес-модель

- Бизнес-модель

- — совокупность стандартизированных способов ведения бизнеса организацией, правил ведения этого бизнеса, лежащих в основе стратегии компании, а также критериев оценки его деловых показателей. В бизнес-модель организации включаются все деловые функции и все функциональные взаимоотношения внутри организации.

В состав бизнес-модели входят: финансовая модель, организационная модель, маркетинговая модель, производственная модель и т.д. В бизнес-модели отражаются сложные взаимосвязи и взаимодействия между этими моделями и их внутренними компонентами.

Толковый словарь «Инновационная деятельность». Термины инновационного менеджмента и смежных областей (от А до Я). 2-е изд., доп. — Новосибирск: Сибирское научное издательство.

.

2008.

Смотреть что такое «Бизнес-модель» в других словарях:

-

Бизнес-модель — логически описывает, каким образом организация создаёт, поставляет клиентам и приобретает стоимость экономическую, социальную и другие формы стоимости[1]. Процесс разработки бизнес модели является частью стратегии бизнеса. В теории и… … Википедия

-

Бизнес-школа — Бизнес школа это организация, которая предлагает образование по управлению бизнесом. Обычно это включает себя такие темы как: Бухгалтерский учёт Финансы Менеджмент Информационные технологии Маркетинг Бизнес модель Кадровая служба Логистика… … Википедия

-

Бизнес-моделирование — (деловое моделирование) деятельность по формированию моделей организаций, включающая описание деловых объектов (подразделений, должностей, ресурсов, ролей, процессов, операций, информационных систем, носителей информации и т. д.) … Википедия

-

Модель — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Модель (значения). Для улучшения этой статьи желательно?: Найти и оформить в виде сносок ссылки на авторите … Википедия

-

Бизнес-процесс — Бизнес процесс это совокупность взаимосвязанных мероприятий или задач, направленных на создание определенного продукта или услуги для потребителей. Для наглядности бизнес процессы визуализируют при помощи блок схемы бизнес процессов.… … Википедия

-

Бизнес-симуляция — Бизнес симуляция интерактивная модель экономической системы, которая по своим внутренним условиям максимально приближена к соответствующей реальной экономической единице (подразделение предприятия, предприятие, отрасль, государство). Бизнес … Википедия

-

Бизнес-акселератор — Бизнес акселератор модель поддержки бизнесов на ранней стадии, которая предполагает интенсивное развитие проекта в кратчайшие сроки. Для быстрого выхода на рынок проекту обеспечиваются инвестирование, инфраструктура, экспертная и… … Википедия

-

Бизнес-архитектура — на основании миссии, стратегии развития и долгосрочных бизнес целей определяет необходимые организационную структуру, структуру каналов продаж и функциональную модель предприятия, документы, используемые в процессе разработки и реализации… … Википедия

-

модель бизнес-деятельности — (ITIL Service Strategy) Профиль рабочей нагрузки одной или нескольких бизнес деятельностей. Модель бизнес деятельности используется поставщиком ИТ услуг для понимания различных уровней активности бизнеса и планирования в соответствии с ними. См.… … Справочник технического переводчика

-

Бизнес-модели — Основные модели построения бизнеса: бизнес бизнес (B2B) и бизнес потребитель (B2C). B2B состоит из компаний, которые делают бизнес между собой, в то время как B2C подразумевает прямые продажи конечному потребителю. Когда только возник интернет… … Википедия

Всего найдено: 149

Здравствуйте. Подскажите правильное написание слова бизнес*сценарий. Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Пишется через дефис: бизнес-сценарий.

Добрый день. Корректно ли употребление слова «эконом» в предложении: Перечень услуг … должен предлагать пассажиру широкий выбор возможностей: от эконом до перевозок бизнес-класса. Спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Такое употребление некорректно, предложение следует перестроить, например: …широкий выбор возможностей от эконом- до бизнес-класса.

Добрый день! Подскажите, пожалуйста, какой вариант правильный? Время интеграции с приставкой -бизнес! ИЛИ Время интеграции с приставкой бизнес-! ИЛИ Время интеграции с приставкой -БИЗНЕС! ИЛИ Время интеграции с приставкой «-бизнес»! Подразумевается, что наступило время бизнес-интеграции. Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Поскольку бизнес— не является приставкой (это первая часть сложных слов), то мы не рекомендуем использовать эту фразу вовсе.

Бизнес-центр класса A — заключается ли буква в кавычки?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Кавычки не нужны.

Добрый день! Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно написать «Бизнес(-)Академия», если важно, чтобы слово «Академия» имела заглавную букву.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Если это название, то правильно: Бизнес-академия.

Здравствуйте! Скажите, пожалуйста, нужен ли дефис в словах «бизнес-онлайн» и «бизнес-бесплатно»? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Академическим орфографическим словарем рекомендуется писать часть бизнес через дефис. Поэтому предложенные Вами написания корректны.

Вопрос касается правильности употребления слов «эмиграция» и «иммиграция». Привожу заголовок текста, написанного в России для россиян:»Открываем бизнес в Европе: лучшие страны для бизнес-иммиграции». Мне кажется, что в этом случае нужно употребить словосочетание «бизнес-эмиграция», потому что относительно России россияне, выезжая из страны, эмигрируют. А вот в стране въезда они будут бизнес-иммигрантами. Так ли?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Может быть, в качестве компромисса, «бизнес-миграции»?

Правильно ли Я пишу слово бизнес-аналитика через дефис? Или нужно раздельно?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы написали правильно: бизнес-аналитика.

Как в этом предложении правильно расставить знаки препинания: Бизнес-леди творили историю(, или , —) и она, история, помнит их имена? Может второе слово «история» взять в скобки? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

По основному правилу между частями сложносочиненного предложения ставится запятая. Поставить вместо этой запятой тире тоже можно, так как вторая часть предложения имеет значение следствия, результата.

Слово история лучше выделить запятыми, а не заключать в скобки.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите, как правильно написать название с добавлением «PRO» в конце слова? БизнесPRO или Бизнес-PRO или Бизнес.PRO? Слово «бизнес» взяла для примера, нужно понять суть, как правильно писать? Спасибо заранее! С уважением, Наталья

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правила русского языка не регламентируют написание таких конструкций.

Встречаются два варианта написания: «бизнес консалтинг» и «бизнес-консалтинг». Какой вариант правильный?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Первая часть сложных слов бизнес- присоединяется дефисом: бизнес-консалтинг.

как правильно : бизнес идея, или бизнес-идея?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Первая часть сложных слов бизнес- присоединяется дефисом: бизнес-идея.

Как правильно писать «спектр бизнес тем» или «спектр бизнес-тем»? И в каких случаях ставится дефис, а в каких нет. Заранее спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Первая часть сложных слов бизнес- присоединяется дефисом: бизнес-тема, спектр бизнес-тем.

Добрый день!

Почему вы даете правильное написание «экономкласс» (без дефиса), но — «бизнес-класс»? Точно ли тут все правильно?

Ответьте, пожалуйста.

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

См. ответ на вопрос № 246836.

Добрый день. Прошу ответить, нужна ли запятая или иной знак препинания после слова «здесь» во фразе: Мы здесь в бизнес-центре «Промэнерго»!

Благодарю за ответ.

Наталия

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нужна запятая после слова здесь.

Бизнес-модель — это анализ и схематичное описание взаимосвязанных бизнес-процессов компании. Модель наглядно показывает: что, кому и как именно продавать, а также насколько это выгодно.

Это не глубинное исследование бизнеса, а скорее экспресс-анализ, который позволяет понять:

- как развивать компанию;

- как оптимизировать бизнес-процессы;

- какие ресурсы нужно привлечь для роста бизнеса.

Стартапам бизнес-модель помогает оценить нишу, увидеть перспективы и скрытые риски, протестировать идеи. Действующему бизнесу — нащупать слабые места и точки роста, чтобы скорректировать свою работу.

Структура бизнес-модели

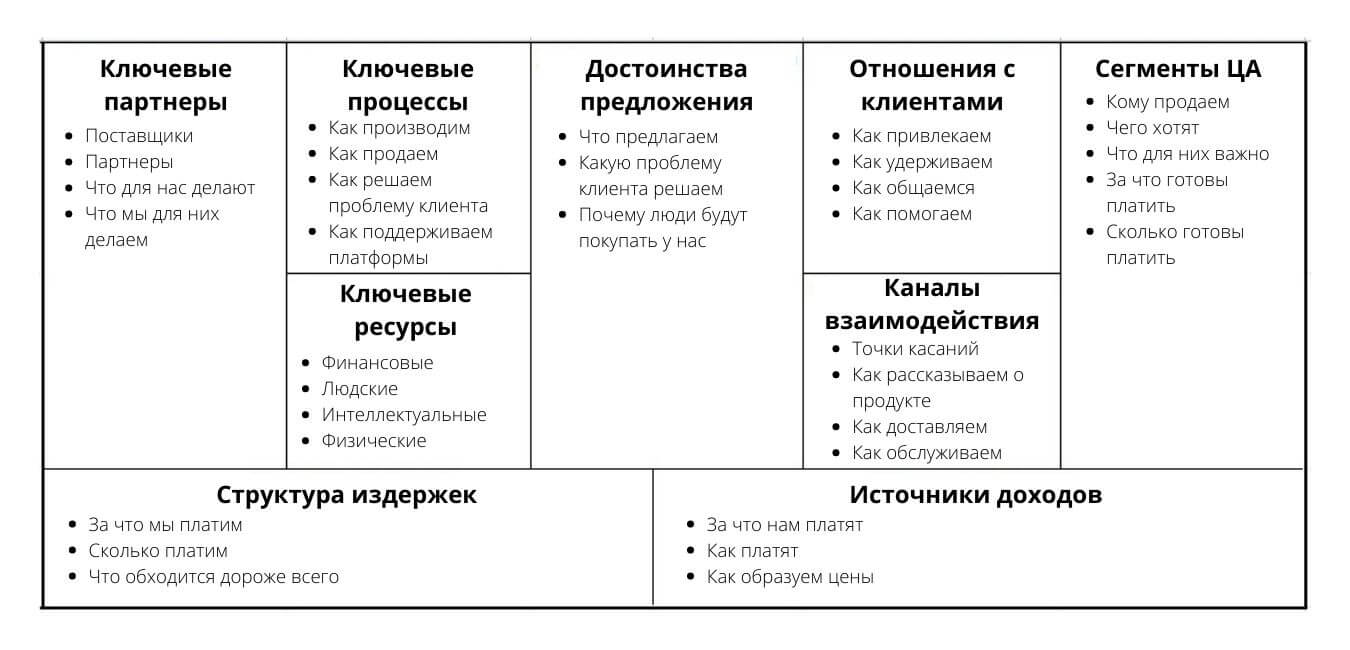

Самый популярный шаблон бизнес-модели предприятия (Business Model Canvas) разработали Александр Остервальдер и Ив Пинье. Он состоит из 9 блоков — ключевых элементов бизнеса.

Сегменты целевой аудитории (ЦА). Это ключевое место всей бизнес-модели. Нужно описать сегменты целевой аудитории, то есть людей, которые будут покупать ваши товары или услуги. Важно понять, кто ваши клиенты, какие качества продукта для них важны, сколько они готовы платить и за что.

Сегментов ЦА может быть несколько.Для каждого нужно сформировать отдельное предложение и взаимодействовать с его представителями, исходя из их потребностей и предпочтений. Чем лучше вы узнаете своих покупателей, тем эффективнее будут рекламные кампании и выше продажи.

Достоинства предложения (УТП). Опишите товары или услуги, которые планируете продавать. Проанализируйте: какую проблему покупателя решает продукт, почему человек будет его покупать у вас, а не у конкурентов.

Суть в том, чтобы построить бизнес-модель вокруг создания большей ценности для покупателя. Чем лучше вы удовлетворите его потребности, тем охотнее он купит продукт и тем с большей вероятностью вернется к вам снова.

Каналы взаимодействия (сбыта). Опишите, какими путями будете «касаться» клиента и рассказывать о продукте, как донесете ценность предложения, как будете доставлять продукт и обслуживать клиентов, как сформируете положительное впечатление от сотрудничества и будете напоминать о себе после продажи.

Отношения с клиентами. Решите, как вы будете привлекать и удерживать клиентов. Нужно понять, как лучше общаться с покупателями (например, лично или через автоматическую рассылку), нужно ли обучать их и чему именно, предполагает ли продукт самообслуживание или требуется ваша помощь.

Источники доходов. Перечислите откуда, за что и как именно вы будете получать деньги.

Деньги можно зарабатывать разными путями:

- продажа товаров и услуг;

- подписка;

- аренда/рента/лизинг;

- продажа лицензий;

- комиссия за посредничество;

- реклама.

Здесь же опишите принципы ценообразования и способы оплаты. Проанализируйте, сколько каждый из сегментов ЦА готов платить. В будущем это поможет посчитать доходность бизнес-модели.

Ключевые ресурсы. Перечислите, что вам нужно, чтобы запустить бизнес, обеспечить его дальнейшее функционирование и развитие. Это всё то, что поможет вам произвести продукт, рассказать о нём покупателям, обеспечить доставку, продажу, послепродажное обслуживание и так далее. Ресурсы могут быть финансовыми, людскими, интеллектуальными, физическими.

Ключевые процессы (активности). Опишите:

- что будете делать, чтобы произвести и продать продукт;

- как будете решать проблемы клиента и обслуживать его, чтобы он остался максимально доволен сотрудничеством;

- как будете поддерживать и развивать сети/CRM-систему/программное обеспечение и прочие платформы, через которые будете взаимодействовать с потребителем.

Ключевые партнеры. Перечислите поставщиков и партнеров, с которыми будете сотрудничать. Определите взаимные выгоды.

Структура издержек. Опишите, на что и сколько именно денег будете тратить. Этот блок поможет наглядно увидеть, какой объем инвестиций потребуется для старта, поддержания и развития бизнеса, какие статьи расходов самые затратные.

Как построить бизнес-модель: пример

Допустим, мы планируем запустить онлайн-курс по обучению ораторскому мастерству. Построить бизнес-модель можно в любой таблице или просто набросать на бумаге от руки.

Сегменты ЦА. Курс будет интересен тем, кто боится публичных выступлений, или публичным людям, которым приходится часто выступать и есть необходимость улучшить ораторские навыки.

УТП. Клиентам важно, чтобы курс вели признанные профессионалы и цена при этом была невысокой.

Каналы взаимодействия. Касаться клиентов будем через рекламу в интернете. Кроме того, проведем бесплатные вебинары, дадим тестовый доступ к обучающей платформе.

Отношения с клиентами. Предоставим несколько тарифов на выбор, бессрочный доступ к базе знаний, круглосуточную поддержку куратора.

Источники доходов. Продажа курса, дополнительные индивидуальные занятия.

Ключевые ресурсы. Для запуска надо будет сделать образовательную платформу, создать группы в соцсетях, нанять кураторов, запустить рекламные кампании.

Ключевые активности. Чтобы создать и поддерживать ценность продукта, надо будет постоянно актуализировать информацию в курсе, поддерживать и обновлять обучающую платформу, давать обратную связь студентам, собирать отзывы, привлекать новых спикеров, создавать новые услуги под потребности клиентов.

Партнеры. Будем привлекать маркетолога, специалиста по интернет-рекламе, блогеров.

Структура издержек. Будем платить спикерам, кураторам, привлеченным партнерам, вложимся в рекламные кампании, заплатим за разработку и поддержание обучающей платформы.

Анализ показал, что курсов по ораторскому мастерству немного, а спрос на них растет. Клиенты готовы платить за профессионализм спикеров и дополнительные услуги. Нам не нужно содержать постоянный штат работников, достаточно привлекать специалистов по мере необходимости. Больших вложений запуск курса не требует, при этом затраты окупятся достаточно быстро. Если содержание курса удовлетворит запросы ЦА, то, скорее всего, запуск будет успешным и принесет хорошую прибыль.

Конечно, это сильно упрощенный и утрированный пример, но он наглядно показывает, что такое бизнес-модель и как ее построить.

Популярные виды бизнес-моделей

В свое время перечисленные ниже бизнес-модели были инновационными. Они выстрелили и обогатили своих создателей. Сегодня ими уже никого не удивишь, и все же каждая продолжает приносить прибыль тысячам компаний.

Популярные виды бизнес-моделей, которые доказали свою эффективность:

- Брокерская. Когда предприниматель сводит продавцов и покупателей, за что взимает определенную комиссию или процент от суммы сделки. По этой бизнес-модели построены торговые биржи, биржи фриланса, маркетплейсы.

Пример: FL.ru, eBay.

- Рекламная. Когда бизнес получает прибыль от размещения рекламы на своем ресурсе.

Пример: Lenta.ru, YouTube.

- Модель краудсорсинга. Когда ресурс получает прибыль с рекламы, но контент там создают сами пользователи.

Пример: Diets.ru, Яндекс.Дзен.

- Модель производителя. Когда производитель продает свой продукт напрямую потребителю, отказываясь от посредников.

Пример: Avon, Кухня на районе.

- Модель дистрибьютора. Предприниматель закупает товар у производителей и реализует с собственной наценкой. Продавать он может по-разному: в розницу, специализироваться на нишевых товарах, предлагать один товар в день с максимальной скидкой, оформлять сделку на сайте с последующей выдачей товара в магазине или со склада.

Пример: Пятерочка, Etsy.

- Франчайзинг. Прибыль получают от продажи доступа к запуску успешной бизнес-модели.

Пример: McDonald’s, Додо Пицца.

- Бритва и лезвие. Основной товар продают дешево, а прибыль получают от реализации расходников. Обратный вариант: прибыль идет от продажи основного дорогого товара, а расходники продают дешево.

Пример: Gillette, HP (принтеры).

- Аренда. Когда отдают помещения или продукцию во временное пользование.

Пример: каршеринг, коворкинг.

- Подписка. Когда продают временный доступ к продукту.

Пример: Netflix, ЛитРес.

- Партнерский маркетинг. Предприниматель получает вознаграждение за продвижение чужих товаров и услуг.

Пример: Сравни.ру, Aviasales.

- Freemium. Когда доступ к основным функциям продукта для клиента бесплатный, а прибыль получают от продажи дополнительных опций.

Пример: Spotify, Lingualeo.

Бизнес-модель — это не бизнес-план. Построение модели не предполагает глубокого анализа и поэтому не может быть основанием для принятия стратегических решений. Но бизнес-модель идеально подходит для быстрой оценки гипотез и выявления текущих рисков для компании.

Главные мысли

Business model innovation is an iterative and potentially circular process[1]

A business model describes how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value,[2] in economic, social, cultural or other contexts. The process of business model construction and modification is also called business model innovation and forms a part of business strategy.[1]

In theory and practice, the term business model is used for a broad range of informal and formal descriptions to represent core aspects of an organization or business, including purpose, business process, target customers, offerings, strategies, infrastructure, organizational structures, sourcing, trading practices, and operational processes and policies including culture.

Context[edit]

The literature has provided very diverse interpretations and definitions of a business model. A systematic review and analysis of manager responses to a survey defines business models as the design of organizational structures to enact a commercial opportunity.[3] Further extensions to this design logic emphasize the use of narrative or coherence in business model descriptions as mechanisms by which entrepreneurs create extraordinarily successful growth firms.[4]

Business models are used to describe and classify businesses, especially in an entrepreneurial setting, but they are also used by managers inside companies to explore possibilities for future development. Well-known business models can operate as «recipes» for creative managers.[5] Business models are also referred to in some instances within the context of accounting for purposes of public reporting.

History[edit]

Over the years, business models have become much more sophisticated. The bait and hook business model (also referred to as the «razor and blades business model» or the «tied products business model») was introduced in the early 20th century. This involves offering a basic product at a very low cost, often at a loss (the «bait»), then charging compensatory recurring amounts for refills or associated products or services (the «hook»). Examples include: razor (bait) and blades (hook); cell phones (bait) and air time (hook); computer printers (bait) and ink cartridge refills (hook); and cameras (bait) and prints (hook). A variant of this model was employed by Adobe, a software developer that gave away its document reader free of charge but charged several hundred dollars for its document writer.

In the 1950s, new business models came from McDonald’s Restaurants and Toyota. In the 1960s, the innovators were Wal-Mart and Hypermarkets. The 1970s saw new business models from FedEx and Toys R Us; the 1980s from Blockbuster, Home Depot, Intel, and Dell Computer; the 1990s from Southwest Airlines, Netflix, eBay, Amazon.com, and Starbucks.

Today, the type of business models might depend on how technology is used. For example, entrepreneurs on the internet have also created new models that depend entirely on existing or emergent technology. Using technology, businesses can reach a large number of customers with minimal costs. In addition, the rise of outsourcing and globalization has meant that business models must also account for strategic sourcing, complex supply chains and moves to collaborative, relational contracting structures.[6]

Theoretical and empirical insights[edit]

Design logic and narrative coherence[edit]

Design logic views the business model as an outcome of creating new organizational structures or changing existing structures to pursue a new opportunity. Gerry George and Adam Bock (2011) conducted a comprehensive literature review and surveyed managers to understand how they perceived the components of a business model.[3] In that analysis these authors show that there is a design logic behind how entrepreneurs and managers perceive and explain their business model. In further extensions to the design logic, George and Bock (2012) use case studies and the IBM survey data on business models in large companies, to describe how CEOs and entrepreneurs create narratives or stories in a coherent manner to move the business from one opportunity to another.[4] They also show that when the narrative is incoherent or the components of the story are misaligned, that these businesses tend to fail. They recommend ways in which the entrepreneur or CEO can create strong narratives for change.

Complementarities between partnering firms[edit]

Berglund and Sandström (2013) argued that business models should be understood from an open systems perspective as opposed to being a firm-internal concern. Since innovating firms do not have executive control over their surrounding network, business model innovation tends to require soft power tactics with the goal of aligning heterogeneous interests.[7] As a result, open business models are created as firms increasingly rely on partners and suppliers to provide new activities that are outside their competence base.[8] In a study of collaborative research and external sourcing of technology, Hummel et al. (2010) similarly found that in deciding on business partners, it is important to make sure that both parties’ business models are complementary.[9] For example, they found that it was important to identify the value drivers of potential partners by analyzing their business models, and that it is beneficial to find partner firms that understand key aspects of one’s own firm’s business model.[10]

The University of Tennessee conducted research into highly collaborative business relationships. Researchers codified their research into a sourcing business model known as Vested Outsourcing), a hybrid sourcing business model in which buyers and suppliers in an outsourcing or business relationship focus on shared values and goals to create an arrangement that is highly collaborative and mutually beneficial to each.[11]

Categorization[edit]

From about 2012, some research and experimentation has theorized about a so-called «liquid business model».[12][13]

Shift from pipes to platforms[edit]

Sangeet Paul Choudary distinguishes between two broad families of business models in an article in Wired magazine.[14] Choudary contrasts pipes (linear business models) with platforms (networked business models). In the case of pipes, firms create goods and services, push them out and sell them to customers. Value is produced upstream and consumed downstream. There is a linear flow, much like water flowing through a pipe. Unlike pipes, platforms do not just create and push stuff out. They allow users to create and consume value.

Alex Moazed, founder and CEO of Applico, defines a platform as a business model that creates value by facilitating exchanges between two or more interdependent groups usually consumers and producers of a given value.[15] As a result of digital transformation, it is the predominant business model of the 21st century.

In an op-ed on MarketWatch,[16] Choudary, Van Alstyne and Parker further explain how business models are moving from pipes to platforms, leading to disruption of entire industries.

Platform[edit]

There are three elements to a successful platform business model.[17] The toolbox creates connection by making it easy for others to plug into the platform. This infrastructure enables interactions between participants. The magnet creates pull that attracts participants to the platform. For transaction platforms, both producers and consumers must be present to achieve critical mass. The matchmaker fosters the flow of value by making connections between producers and consumers. Data is at the heart of successful matchmaking, and distinguishes platforms from other business models.

Chen (2009) stated that the business model has to take into account the capabilities of Web 2.0, such as collective intelligence, network effects, user-generated content, and the possibility of self-improving systems. He suggested that the service industry such as the airline, traffic, transportation, hotel, restaurant, information and communications technology and online gaming industries will be able to benefit in adopting business models that take into account the characteristics of Web 2.0. He also emphasized that Business Model 2.0 has to take into account not just the technology effect of Web 2.0 but also the networking effect. He gave the example of the success story of Amazon in making huge revenues each year by developing an open platform that supports a community of companies that re-use Amazon’s on-demand commerce services.[18][need quotation to verify]

Impacts of platform business models[edit]

Jose van Dijck (2013) identifies three main ways that media platforms choose to monetize, which mark a change from traditional business models.[19] One is the subscription model, in which platforms charge users a small monthly fee in exchange for services. She notes that the model was ill-suited for those «accustomed to free content and services», leading to a variant, the freemium model. A second method is via advertising. Arguing that traditional advertising is no longer appealing to people used to «user-generated content and social networking», she states that companies now turn to strategies of customization and personalization in targeted advertising. Eric K. Clemons (2009) asserts that consumers no longer trust most commercial messages;[20] Van Dijck argues platforms are able to circumvent the issue through personal recommendations from friends or influencers on social media platforms, which can serve as a more subtle form of advertisement. Finally, a third common business model is monetization of data and metadata generated from the use of platforms.

Applications[edit]

Malone et al.[21] found that some business models, as defined by them, indeed performed better than others in a dataset consisting of the largest U.S. firms, in the period 1998 through 2002, while they did not prove whether the existence of a business model mattered.

In the healthcare space, and in particular in companies that leverage the power of Artificial Intelligence, the design of business models is particularly challenging as there are a multitude of value creation mechanisms and a multitude of possible stakeholders. An emerging categorization has identified seven archetypes.[22]

The concept of a business model has been incorporated into certain accounting standards. For example, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) utilizes an «entity’s business model for managing the financial assets» as a criterion for determining whether such assets should be measured at amortized cost or at fair value in its International Financial Reporting Standard, IFRS 9.[23][24][25][26] In their 2013 proposal for accounting for financial instruments, the Financial Accounting Standards Board also proposed a similar use of business model for classifying financial instruments.[27] The concept of business model has also been introduced into the accounting of deferred taxes under International Financial Reporting Standards with 2010 amendments to IAS 12 addressing deferred taxes related to investment property.[28][29][30]

Both IASB and FASB have proposed using the concept of business model in the context of reporting a lessor’s lease income and lease expense within their joint project on accounting for leases.[31][32][33][34][35] In its 2016 lease accounting model, IFRS 16, the IASB chose not to include a criterion of «stand alone utility» in its lease definition because «entities might reach different conclusions for contracts that contain the same rights of use, depending on differences between customers’ resources or suppliers’ business models.»[36] The concept has also been proposed as an approach for determining the measurement and classification when accounting for insurance contracts.[37][38] As a result of the increasing prominence the concept of business model has received in the context of financial reporting, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), which advises the European Union on endorsement of financial reporting standards, commenced a project on the «Role of the Business Model in Financial Reporting» in 2011.[39]

Design[edit]

Business model design generally refers to the activity of designing a company’s business model. It is part of the business development and business strategy process and involves design methods. Massa and Tucci (2014)[40] highlighted the difference between crafting a new business model when none is in place, as it is often the case with academic spinoffs and high technology entrepreneurship, and changing an existing business model, such as when the tooling company Hilti shifted from selling its tools to a leasing model. They suggested that the differences are so profound (for example, lack of resource in the former case and inertia and conflicts with existing configurations and organisational structures in the latter) that it could be worthwhile to adopt different terms for the two. They suggest business model design to refer to the process of crafting a business model when none is in place and business model reconfiguration for process of changing an existing business model, also highlighting that the two process are not mutually exclusive, meaning reconfiguration may involve steps which parallel those of designing a business model.

Economic consideration[edit]

Al-Debei and Avison (2010) consider value finance as one of the main dimensions of BM which depicts information related to costing, pricing methods, and revenue structure. Stewart and Zhao (2000) defined the business model as «a statement of how a firm will make money and sustain its profit stream over time.»[41]

Component consideration[edit]

Osterwalder et al. (2005) consider the Business Model as the blueprint of how a company does business.[42] Slywotzky (1996) regards the business model as «the totality of how a company selects its customers, defines and differentiates it offerings, defines the tasks it will perform itself and those it will outsource, configures its resources, goes to market, creates utility for customers and captures profits.»[43]

Strategic outcome[edit]

Mayo and Brown (1999) considered the business model as «the design of key interdependent systems that create and sustain a competitive business.»[44] Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2011) explain a business model as a set of «choices (policy, assets and governance)» and «consequences (flexible and rigid)» and underline the importance of considering «how it interacts with models of other players in the industry» instead of thinking of it in isolation.[45]

Definitions of design or development[edit]

Zott and Amit (2009) consider business model design from the perspectives of design themes and design content. Design themes refer to the system’s dominant value creation drivers and design content examines in greater detail the activities to be performed, the linking and sequencing of the activities and who will perform the activities.[46]

Design themes emphasis[edit]

Environment-strategy-structure-operations business model development

Developing a framework for business model development with an emphasis on design themes, Lim (2010) proposed the environment-strategy-structure-operations (ESSO) business model development which takes into consideration the alignment of the organization’s strategy with the organization’s structure, operations, and the environmental factors in achieving competitive advantage in varying combination of cost, quality, time, flexibility, innovation and affective.[47]

Design content emphasis[edit]

Business model design includes the modeling and description of a company’s:

- value propositions

- target customer segments

- distribution channels

- customer relationships

- value configurations

- core capabilities

- commercial network

- partner network

- cost structure

- revenue model

A business model design template can facilitate the process of designing and describing a company’s business model. In a paper published in 2017,[48] Johnson demonstrated how matrix methods may usefully be deployed to characterise the architecture of resources, costs, and revenues that a business uses to create and deliver value to customers which defines its business model. Systematisation of this technique (Johnson settles on a business genomic code of seven matrix elements of a business model) would support a taxonomical approach to empirical studies of business models in the same way that Linnaeus’ taxonomy revolutionised biology.

Daas et al. (2012) developed a decision support system (DSS) for business model design. In their study a decision support system (DSS) is developed to help SaaS in this process, based on a design approach consisting of a design process that is guided by various design methods.[49]

Examples[edit]

In the early history of business models it was very typical to define business model types such as bricks-and-mortar or e-broker. However, these types usually describe only one aspect of the business (most often the revenue model). Therefore, more recent literature on business models concentrate on describing a business model as a whole, instead of only the most visible aspects.

The following examples provide an overview for various business model types that have been in discussion since the invention of term business model:

- Bricks and clicks business model

- Business model by which a company integrates both offline (bricks) and online (clicks) presences. One example of the bricks-and-clicks model is when a chain of stores allows the user to order products online, but lets them pick up their order at a local store.

- Dual business models

- Contemporary companies increasingly respond to contradictory demands by transitioning from a single to a dual business model. For instance, stakeholders’ changing expectations motivate companies to combine their commercial businesses with social businesses. Globalization prompts companies to complement their premium business models with low-cost business models for emerging markets. Digitalization enables manufacturing companies to add advanced service business models to their product business models.[50]

- Collective business models

- Business system, organization or association typically composed of relatively large numbers of businesses, tradespersons or professionals in the same or related fields of endeavor, which pools resources, shares information or provides other benefits for their members. For example, a science park or high-tech campus provides shared resources (e.g. cleanrooms and other lab facilities) to the firms located on its premises, and in addition seeks to create an innovation community among these firms and their employees.[51]

- Cutting out the middleman model

- The removal of intermediaries in a supply chain: «cutting out the middleman». Instead of going through traditional distribution channels, which had some type of intermediate (such as a distributor, wholesaler, broker, or agent), companies may now deal with every customer directly, for example via the Internet.

- Direct sales model

- Direct selling is marketing and selling products to consumers directly, away from a fixed retail location. Sales are typically made through party plan, one-to-one demonstrations, and other personal contact arrangements. A text book definition is: «The direct personal presentation, demonstration, and sale of products and services to consumers, usually in their homes or at their jobs.»[52]

- Distribution business models, various

- Fee in, free out

- Business model which works by charging the first client a fee for a service, while offering that service free of charge to subsequent clients.

- Franchise

- Franchising is the practice of using another firm’s successful business model. For the franchisor, the franchise is an alternative to building ‘chain stores’ to distribute goods and avoid investment and liability over a chain. The franchisor’s success is the success of the franchisees. The franchisee is said to have a greater incentive than a direct employee because he or she has a direct stake in the business.

- Sourcing business model

- Sourcing Business Models are a systems-based approach to structuring supplier relationships. A sourcing business model is a type of business model that is applied to business relationships where more than one party needs to work with another party to be successful. There are seven sourcing business models that range from the transactional to investment-based. The seven models are: Basic Provider, Approved Provider, Preferred Provider, Performance-Based/Managed Services Model, Vested outsourcing Business Model, Shared Services Model, and Equity Partnership Model. Sourcing business models are targeted for procurement professionals who seek a modern approach to achieve the best fit between buyers and suppliers. Sourcing business model theory is based on a collaborative research effort by the University of Tennessee (UT), the Sourcing Industry Group (SIG), the Center for Outsourcing Research and Education (CORE), and the International Association for Contracts and Commercial Management (IACCM). This research formed the basis for the 2016 book, Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy: Harnessing the Potential of Sourcing Business Models in Modern Procurement.[53]

- Freemium business model

- Business model that works by offering basic Web services, or a basic downloadable digital product, for free, while charging a premium for advanced or special features.[54]

- Pay what you can (PWYC)

- A non-profit or for-profit business model which does not depend on set prices for its goods, but instead asks customers to pay what they feel the product or service is worth to them.[55][56] It is often used as a promotional tactic,[57] but can also be the regular method of doing business. It is a variation on the gift economy and cross-subsidization, in that it depends on reciprocity and trust to succeed.

- «Pay what you want» (PWYW) is sometimes used synonymously, but «pay what you can» is often more oriented to charity or socially oriented uses, based more on ability to pay, while «pay what you want» is often more broadly oriented to perceived value in combination with willingness and ability to pay.

- Value-added reseller model

- Value Added Reseller is a model where a business makes something which is resold by other businesses but with modifications which add value to the original product or service. These modifications or additions are mostly industry specific in nature and are essential for the distribution. Businesses going for a VAR model have to develop a VAR network. It is one of the latest collaborative business models which can help in faster development cycles and is adopted by many Technology companies especially software.

Other examples of business models are:

- Auction business model

- All-in-one business model

- Chemical leasing

- Low-cost carrier business model

- Loyalty business models

- Monopolistic business model

- Multi-level marketing business model

- Network effects business model

- Online auction business model

- Online content business model

- Premium business model

- Professional open-source model

- Pyramid scheme business model

- Razor and blades model

- Servitization of products business model

- Subscription business model

- Network Orchestrators Companies

- Virtual business model

Frameworks[edit]

Although Webvan failed in its goal of disintermediating the North American supermarket industry, several supermarket chains (like Safeway Inc.) have launched their own delivery services to target the niche market to which Webvan catered.

Technology centric communities have defined «frameworks» for business modeling. These frameworks attempt to define a rigorous approach to defining business value streams. It is not clear, however, to what extent such frameworks are actually important for business planning. Business model frameworks represent the core aspect of any company; they involve «the totality of how a company selects its customers defines and differentiates its offerings, defines the tasks it will perform itself and those it will outsource, configures its resource, goes to market, creates utility for customers, and captures profits».[58] A business framework involves internal factors (market analysis; products/services promotion; development of trust; social influence and knowledge sharing) and external factors (competitors and technological aspects).[59]

A review on business model frameworks can be found in Krumeich et al. (2012).[60] In the following some frameworks are introduced.

- Business reference model

- Business reference model is a reference model, concentrating on the architectural aspects of the core business of an enterprise, service organization or government agency.

- Component business model

- Technique developed by IBM to model and analyze an enterprise. It is a logical representation or map of business components or «building blocks» and can be depicted on a single page. It can be used to analyze the alignment of enterprise strategy with the organization’s capabilities and investments, identify redundant or overlapping business capabilities, etc.

- Industrialization of services business model

- Business model used in strategic management and services marketing that treats service provision as an industrial process, subject to industrial optimization procedures

- Business Model Canvas

- Developed by A. Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, Alan Smith, and 470 practitioners from 45 countries, the business model canvas[2][61] is one of the most used frameworks for describing the elements of business models.

- OGSM

- The OGSM is developed by Marc van Eck and Ellen van Zanten of Business Openers into the ‘Business plan on 1 page’. Translated in several languages all over the world. #1 Management book in The Netherlands in 2015. The foundation of Business plan on 1 page is the OGSM. Objectives, Goals, Strategies and Measures (dashboard and actions).

[edit]

The process of business model design is part of business strategy. Business model design and innovation refer to the way a firm (or a network of firms) defines its business logic at the strategic level.

In contrast, firms implement their business model at the operational level, through their business operations. This refers to their process-level activities, capabilities, functions and infrastructure (for example, their business processes and business process modeling), their organizational structures (e.g. organograms, workflows, human resources) and systems (e.g. information technology architecture, production lines).

The brand is a consequence of the business model and has a symbiotic relationship with it, because the business model determines the brand promise, and the brand equity becomes a feature of the model. Managing this is a task of integrated marketing.

The standard terminology and examples of business models do not apply to most nonprofit organizations, since their sources of income are generally not the same as the beneficiaries. The term ‘funding model’ is generally used instead.[62]

The model is defined by the organization’s vision, mission, and values, as well as sets of boundaries for the organization—what products or services it will deliver, what customers or markets it will target, and what supply and delivery channels it will use. Mission and vision together make part of the overall business purpose. While the business model includes high-level strategies and tactical direction for how the organization will implement the model, it also includes the annual goals that set the specific steps the organization intends to undertake in the next year and the measures for their expected accomplishment. Each of these is likely to be part of internal documentation that is available to the internal auditor.

Business model innovation[edit]

Business model innovation types[63]

When an organisation creates a new business model, the process is called business model innovation.[64][65] There is a range of reviews on the topic,[63][66][67] the latter of which defines business model innovation as «the conceptualisation and implementation of new business models». This can comprise the development of entirely new business models, the diversification into additional business models, the acquisition of new business models, or the transformation from one business model to another (see figure on the right). The transformation can affect the entire business model or individual or a combination of its value proposition, value creation and deliver, and value capture elements, the alignment between the elements.[68] The concept facilitates the analysis and planning of transformations from one business model to another.[67] Frequent and successful business model innovation can increase an organisation’s resilience to changes in its environment and if an organisation has the capability to do this, it can become a competitive advantage.[69]

Business Model Adaptation[edit]

As a specific instance of Business Model Dynamics, a research strand derived from the evolving changes in business models, BMA identifies an update of the current business model to changes derived from the context. BMA can be innovative or not, depending on the degree of novelty of the changes implemented. As a consequence of the new context, several business model elements are promoted to answer those challenges, pivoting the business model towards new models. Companies adapt their business model when someone or something such as COVID-19 has disrupted the market. BMA could fit any organization, but incumbents are more motivated to adapt their current BM than to change it radically or create a new one.[70]

See also[edit]

- Business plan

- Business rule

- Concept-driven strategy

- Enterprise architecture

- Growth platforms

- Institutional logic

- Market structure

- Marketing plan

- Marketing strategy

- Product differentiation

- Sensemaking

- Strategy dynamics

- Strategy Markup Language

- The Design of Business

- Value migration

- Viable system model

- Business model pattern

References[edit]

- ^ a b Geissdoerfer, Martin; Savaget, Paulo; Evans, Steve (2017). «The Cambridge Business Model Innovation Process». Procedia Manufacturing. 8: 262–269. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2017.02.033. ISSN 2351-9789.

- ^ a b Business Model Generation, Alexander Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur, Alan Smith, and 470 practitioners from 45 countries, self-published, 2010

- ^ a b George, G and Bock AJ. 2011. The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1): 83-111

- ^ a b George, G and Bock AJ. 2012. Models of opportunity: How entrepreneurs design firms to achieve the unexpected. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-17084-0

- ^ Baden-Fuller, Charles; Mary S. Morgan (2010). «Business Models as Models» (PDF). Long Range Planning. 43 (2/3): 156–171. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.005.

- ^ Unpacking Sourcing Business Models: 21st Century Solutions for Sourcing Services, The University of Tennessee, 2014

- ^ Berglund, Henrik; Sandström, C (2013). «Business model innovation from an open systems perspective: structural challenges and managerial solutions». International Journal of Product Development. 8 (3/4): 274–2845. doi:10.1504/IJPD.2013.055011. S2CID 293423.

- ^ Visnjic, Ivanka; Neely, Andy; Jovanovic, Marin (2018). «The path to outcome delivery: Interplay of service market strategy and open business models». Technovation. 72–73: 46–59. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2018.02.003. S2CID 158191717.

- ^ Karl M. Popp & Ralf Meyer (2010). Profit from Software Ecosystems: Business Models, Ecosystems and Partnerships in the Software Industry. Norderstedt, Germany: BOD. ISBN 978-3-8391-6983-4.

- ^ Hummel, E., G. Slowinski, S. Matthews, and E. Gilmont. 2010. Business models for collaborative research. Research Technology Management 53 (6) 51-54.

- ^ Vitasek, Kate. Vested Outsourcing: Five Rules that will Transform Outsourcing» (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) ISBN 978-1-137-29719-8

- ^

Pedersen, Kristian Bonde; Svarre, Kristoffer Rose; Slepniov, Dmitrij; Lindgren, Peter. «Global Business Model – a step into a liquid business model» (PDF). - ^

Henning, Dietmar (2012-02-11). «IBM launches new form of day-wage labour». World Socialist Web Site. International Committee of the Fourth International (ICFI). Retrieved 2015-02-24.The «liquid» model now being pursued is not limited to IBM. […] It is no accident that IBM is looking to Germany as the country to pilot this model. Since the Hartz welfare and labour «reforms» of the former Social Democratic Party-Green government (1998-2005), Germany is at the forefront in developing forms of precarious employment. […] The IBM model globalises the so-called employment contract, increasingly replacing agency working as the preferred form of low-wage labour. Companies assign key tasks to subcontractors, paying only for each project.

- ^ Choudary, Sangeet Paul (2013). «Why Business Models fail: Pipes vs. Platforms». Wired.

- ^ «What is a Platform» by Alex Moazed on May 1, 2016

- ^ «What Twitter knows that Blackberry didn’t», Choudary, Van Alstyne, Parker, MarketWatch

- ^ Choudary, Sangeet Paul (January 31, 2013). «Three elements of a successful platform». Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Chen, T. F. 2009. Building a platform of Business Model 2.0 to creating real business value with Web 2.0 for web information services industry. International Journal of Electronic Business Management 7 (3) 168-180.

- ^ Dijck, José van. (2013). The culture of connectivity : a critical history of social media. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997079-7. OCLC 839305263.

- ^ Clemons, Eric K. (2009). «Business Models for Monetizing Internet Applications and Web Sites: Experience, Theory, and Predictions». Journal of Management Information Systems. 26 (2): 15–41. doi:10.2753/MIS0742-1222260202. ISSN 0742-1222. S2CID 33373266.

- ^ «Do Some Business Models Perform Better than Others?», Malone et al., May 2006.

- ^ Garbuio, Massimo; Lin, Nidthida (2018). «Artificial Intelligence as a Growth Engine for Health Care Startups: Emerging Business Models». California Management Review. 61 (2): 59–83. doi:10.1177/0008125618811931. S2CID 158219917.

- ^ International Financial Reporting Standard 9: Financial Instruments. International Accounting Standards Board. October 2010. p. A312.

- ^ «The beginning of the end for IAS 39 — Issue of IFRS 9 regarding Classification and Measurement of Financial Assets». Deloitte & Touche. November 2009. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «Business Models Matter (for Accounting, That Is)». cfo.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «An optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty: is IFRS 9 an opportunity or a difficulty?». Ernst & Young. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-04-05. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «FASB Exposure Draft: Recognition and Measurement of Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities». Financial Accounting Standards Board. April 12, 2013. p. 174. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ^ International Accounting Standard 12: Income Taxes. International Accounting Standards Board. December 31, 2010. p. A508.

- ^ «IASB issues amendments to IAS 12» (PDF). Deloitte & Touche. January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-09. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «Amendments to IAS 12:Income Taxes» (PDF). Ernst & Young. December 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-20. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «Exposure Draft:Leases» (PDF). International Accounting Standards Board. August 2010. p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-05. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «Exposure Draft: Leases». Financial Accounting Standards Board. August 17, 2010. p. 29. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «Project Update: Leases—Joint Project of the FASB and the IASB». Financial Accounting Standards Board. August 1, 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- ^ «Exposure Draft: Leases» (PDF). International Accounting Standards Board. May 2013. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-26. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ^ «FASB Exposure Draft: Leases». Financial Accounting Standards Board. May 16, 2013. p. 82. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- ^ IFRS 16 Leases: Basis for Conclusions. International Accounting Standards Board. January 2016. p. 39.

- ^ «Application of business model to insurance contracts» (PDF). HUB global insurance group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «FASB Education Session — Insurance Contracts:PricewaterhouseCoopers Summary of the Meeting» (PDF). PricewaterhouseCoopers. February 9, 2010. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ «EFRAG calls for candidates for an Advisory Panel on the proactive project on the Role of the Business Model in Financial Reporting». European Financial Reporting Advisory Group. December 15, 2010. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- ^ Massa, L., & Tucci, C. L. 2014. Business model innovation. In M. Dodgson, D. M. Gann & N. Phillips (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation management: 420–441. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Lee, G. K. and R. E. Cole. 2003. Internet Marketing, Business Models and Public Policy. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 19 (Fall) 287-296.

- ^ Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and C. L. Tucci. 2005. Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 16 1-40.

- ^ Slywotzky, A. J. (1996). Value Migration: How to Think Several Moves Ahead of the Competition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- ^ Mayo, M. C. and G.S. Brown. 1999. Building a Competitive Business Model. Ivey Business Journal63 (3) 18-23.

- ^ «How to Design a Winning Business Model». Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ^ Zott, C. and R. Amit. 2009. Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective. Long Range Planning 43 216-226

- ^ Lim, M. 2010. Environment-Strategy-Structure-Operations (ESSO) Business Model. Knowledge Management Module at Bangor University, Wales. https://communities-innovation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ESSO-Business-Model-Michael-Lim-Bangor-University-iii.pdf

- ^ Johnson P. (December 2017). «Business Models: Formal Description and Economic Optimization». Managerial and Decision Economics. 38–8 (8): 1105–1115. doi:10.1002/mde.2849 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Daas, D., Hurkmans, T., Overbeek, S. and Bouwman, H. 2012. Developing a decision support system for business model design. Electronic Markets — The International Journal on Networked Business, published Online 29. Dec. 2012.

- ^ Visnjic, Ivanka; Jovanovic, Marin; Raisch, Sebastian (2021). «Managing the Transition to a Dual Business Model: Tradeoff, Paradox, and Routinized Practices». Organization Science. 33 (5): 1964–1989. doi:10.1287/orsc.2021.1519. S2CID 243793043.

- ^ Borgh, Michel; Cloodt, Myriam; Romme, A. Georges L. (2012). «Value creation by knowledge-based ecosystems: Evidence from a field study». R&D Management. 42 (2): 150–169. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9310.2011.00673.x. S2CID 154771621.

- ^ Michael A. Belch George E. Belch Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 7/e., McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2006

- ^ Keith, Bonnie; et al. (2016). Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy: Harnessing the Potential of Sourcing Business Models for Modern Procurement (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137552181.

- ^ JLM de la Iglesia, JEL Gayo, «Doing business by selling free services». Web 2.0: The Business Model, 2008. Springer

- ^ Gergen, Chris; Gregg Vanourek (December 3, 2008). «The ‘pay as you can’ cafe». The Washington Times. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh (October 1, 2007). «Radiohead Says: Pay What You Want». Time. Archived from the original on October 4, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ «Pay What You Can». Alley Theatre. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ^ Slywotzky, A. J. (1996). Value Migration: How to Think Several Moves Ahead of the Competition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- ^ Ferri Fernando, D’Andrea Alessia, Grifoni Patrizia (2012). IBF: An Integrated Business Framework for Virtual Communities in Journal of electronic commerce in organizations; IGI Global, Hershey (Stati Uniti d’America)

- ^ J. Krumeich, T. Burkhart, D. Werth, and P. Loos. «Towards a Component-based Description of Business Models: A State-of-the-Art Analysis». Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS 2012) Proceedings. Paper 19.

- ^ ‘The Business Model Ontology — A Proposition In A Design Science Approach

- ^ William Foster, Peter Kim, Barbara Christiansen. Ten Nonprofit Funding Models, Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2009-03-05.

- ^ a b Geissdoerfer, Martin; Vladimirova, Doroteya; Evans, Steve (2018). «Sustainable business model innovation: A review». Journal of Cleaner Production. 198: 401–416. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.240. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Tucci, C.L. (2005). «Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept». Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 16: 1–25. doi:10.17705/1CAIS.01601 – via Association for Information Systems.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chesbrough, Henry (2010). «Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers». Long Range Planning. 43 (2–3): 354–363. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.010. ISSN 0024-6301.

- ^ Foss, Nicolai J.; Saebi, Tina (2017). «Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation» (PDF). Journal of Management. 43 (1): 200–227. doi:10.1177/0149206316675927. ISSN 0149-2063. S2CID 56381168.

- ^ a b Schallmo, D. (2013). Geschäftsmodell-Innovation: Grundlagen, bestehende Ansätze, methodisches Vorgehen und B2B-Geschäftsmodelle. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- ^ Sjödin, David; Parida, Vinit; Jovanovic, Marin; Visnjic, Ivanka (2020). «Value creation and value capture alignment in business model innovation: A process view on outcome‐based business models». Journal of Product Innovation Management. 37 (2): 158–183. doi:10.1111/jpim.12516.

- ^ Mitchell, Donald W.; Bruckner Coles, Carol (2004). «Business model innovation breakthrough moves». Journal of Business Strategy. 25 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1108/02756660410515976. ISSN 0275-6668.

- ^ Penarroya-Farell, Montserrat; Miralles, Francesc (2022). «Business Model Adaptation to the COVID-19 Crisis: Strategic Response of the Spanish Cultural and Creative Firms». Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 1 (1): 39. doi:10.3390/joitmc8010039.

Further reading[edit]

- A. Afuah and C. Tucci, Internet Business Models and Strategies, Boston, McGraw Hill, 2003.

- T. Burkhart, J. Krumeich, D. Werth, and P. Loos, Analyzing the Business Model Concept — A Comprehensive Classification of Literature, Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2011). Paper 12. http://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2011/proceedings/generaltopics/12

- H. Chesbrough and R. S. Rosenbloom, The Role of the Business Model in capturing value from Innovation: Evidence from XEROX Corporation’s Technology Spinoff Companies., Boston, Massachusetts, Harvard Business School, 2002.

- Marc Fetscherin and Gerhard Knolmayer, Focus Theme Articles: Business Models for Content Delivery: An Empirical Analysis of the Newspaper and Magazine Industry, International Journal on Media Management, Volume 6, Issue 1 & 2 September 2004, pages 4 – 11, September 2004.

- George, G., Bock, AJ. Models of opportunity: How entrepreneurs design firms to achieve the unexpected. Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-521-17084-0.

- J. Gordijn, Value-based Requirements Engineering — Exploring Innovative e-Commerce Ideas, Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit, 2002.

- G. Hamel, Leading the revolution., Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 2000.

- J. Linder and S. Cantrell, Changing Business Models: Surveying the Landscape, Accenture Institute for Strategic Change, 2000.

- Lindgren, P. and Jørgensen, R., M.-S. Li, Y. Taran, K. F. Saghaug, «Towards a new generation of business model innovation model», presented at the 12th International CINet Conference: Practicing innovation in times of discontinuity, Aarhus, Denmark, 10–13 September 2011

- Long Range Planning, vol 43 April 2010, «Special Issue on Business Models,» includes 19 pieces by leading scholars on the nature of business models

- S. Muegge. Business Model Discovery by Technology Entrepreneurs. Technology Innovation Management Review, April 2012, pp. 5–16.

- S. Muegge, C. Haw, and Sir T. Matthews, Business Models for Entrepreneurs and Startups, Best of TIM Review, Book 2, Talent First Network, 2013.

- Alex Osterwalder et al. Business Model Generation, Co-authored with Yves Pigneur, Alan Smith, and 470 practitioners from 45 countries, self-published, 2009

- O. Peterovic and C. Kittl et al., Developing Business Models for eBusiness., International Conference on Electronic Commerce 2001, 2001.

- Alt, Rainer; Zimmermann, Hans-Dieter: Introduction to Special Section – Business Models. In: Electronic Markets Anniversary Edition, Vol. 11 (2001), No. 1. link

- Santiago Restrepo Barrera, Business model tool, Business life model, Colombia 2012, http://www.imaginatunegocio.com/#!business-life-model/c1o75 (Spanish)

- Paul Timmers. Business Models for Electronic Markets, Electronic Markets, Vol 8 (1998) No 2, pp. 3 – 8.

- Peter Weill and M. R. Vitale, Place to space: Migrating to eBusiness Models., Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 2001.

- C. Zott, R. Amit, & L.Massa. ‘The Business Model: Theoretical Roots, Recent Developments, and Future Research’, WP-862, IESE, June, 2010 — revised September 2010 (PDF)

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why Business Models Matter, Harvard Business Review, May: 86–92.

- Govindarajan, V. and Trimble, C. (2011). The CEO’s role in business model reinvention. Harvard Business Review, January–February: 108–114.

- van Zyl, Jay. (2011). Built to Thrive: using innovation to make your mark in a connected world. Chapter 7 Towards a universal service delivery platform. San Francisco.

External links[edit]

Media related to Business models at Wikimedia Commons

- Sustaining Digital Resources: An on-the-ground view of projects today, Ithaka, November 2009. Overview of the models being deployed and analysis on the effects of income generation and cost management.

Business model innovation is an iterative and potentially circular process[1]

A business model describes how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value,[2] in economic, social, cultural or other contexts. The process of business model construction and modification is also called business model innovation and forms a part of business strategy.[1]

In theory and practice, the term business model is used for a broad range of informal and formal descriptions to represent core aspects of an organization or business, including purpose, business process, target customers, offerings, strategies, infrastructure, organizational structures, sourcing, trading practices, and operational processes and policies including culture.

Context[edit]

The literature has provided very diverse interpretations and definitions of a business model. A systematic review and analysis of manager responses to a survey defines business models as the design of organizational structures to enact a commercial opportunity.[3] Further extensions to this design logic emphasize the use of narrative or coherence in business model descriptions as mechanisms by which entrepreneurs create extraordinarily successful growth firms.[4]

Business models are used to describe and classify businesses, especially in an entrepreneurial setting, but they are also used by managers inside companies to explore possibilities for future development. Well-known business models can operate as «recipes» for creative managers.[5] Business models are also referred to in some instances within the context of accounting for purposes of public reporting.

History[edit]

Over the years, business models have become much more sophisticated. The bait and hook business model (also referred to as the «razor and blades business model» or the «tied products business model») was introduced in the early 20th century. This involves offering a basic product at a very low cost, often at a loss (the «bait»), then charging compensatory recurring amounts for refills or associated products or services (the «hook»). Examples include: razor (bait) and blades (hook); cell phones (bait) and air time (hook); computer printers (bait) and ink cartridge refills (hook); and cameras (bait) and prints (hook). A variant of this model was employed by Adobe, a software developer that gave away its document reader free of charge but charged several hundred dollars for its document writer.

In the 1950s, new business models came from McDonald’s Restaurants and Toyota. In the 1960s, the innovators were Wal-Mart and Hypermarkets. The 1970s saw new business models from FedEx and Toys R Us; the 1980s from Blockbuster, Home Depot, Intel, and Dell Computer; the 1990s from Southwest Airlines, Netflix, eBay, Amazon.com, and Starbucks.

Today, the type of business models might depend on how technology is used. For example, entrepreneurs on the internet have also created new models that depend entirely on existing or emergent technology. Using technology, businesses can reach a large number of customers with minimal costs. In addition, the rise of outsourcing and globalization has meant that business models must also account for strategic sourcing, complex supply chains and moves to collaborative, relational contracting structures.[6]

Theoretical and empirical insights[edit]

Design logic and narrative coherence[edit]

Design logic views the business model as an outcome of creating new organizational structures or changing existing structures to pursue a new opportunity. Gerry George and Adam Bock (2011) conducted a comprehensive literature review and surveyed managers to understand how they perceived the components of a business model.[3] In that analysis these authors show that there is a design logic behind how entrepreneurs and managers perceive and explain their business model. In further extensions to the design logic, George and Bock (2012) use case studies and the IBM survey data on business models in large companies, to describe how CEOs and entrepreneurs create narratives or stories in a coherent manner to move the business from one opportunity to another.[4] They also show that when the narrative is incoherent or the components of the story are misaligned, that these businesses tend to fail. They recommend ways in which the entrepreneur or CEO can create strong narratives for change.

Complementarities between partnering firms[edit]

Berglund and Sandström (2013) argued that business models should be understood from an open systems perspective as opposed to being a firm-internal concern. Since innovating firms do not have executive control over their surrounding network, business model innovation tends to require soft power tactics with the goal of aligning heterogeneous interests.[7] As a result, open business models are created as firms increasingly rely on partners and suppliers to provide new activities that are outside their competence base.[8] In a study of collaborative research and external sourcing of technology, Hummel et al. (2010) similarly found that in deciding on business partners, it is important to make sure that both parties’ business models are complementary.[9] For example, they found that it was important to identify the value drivers of potential partners by analyzing their business models, and that it is beneficial to find partner firms that understand key aspects of one’s own firm’s business model.[10]

The University of Tennessee conducted research into highly collaborative business relationships. Researchers codified their research into a sourcing business model known as Vested Outsourcing), a hybrid sourcing business model in which buyers and suppliers in an outsourcing or business relationship focus on shared values and goals to create an arrangement that is highly collaborative and mutually beneficial to each.[11]

Categorization[edit]

From about 2012, some research and experimentation has theorized about a so-called «liquid business model».[12][13]

Shift from pipes to platforms[edit]

Sangeet Paul Choudary distinguishes between two broad families of business models in an article in Wired magazine.[14] Choudary contrasts pipes (linear business models) with platforms (networked business models). In the case of pipes, firms create goods and services, push them out and sell them to customers. Value is produced upstream and consumed downstream. There is a linear flow, much like water flowing through a pipe. Unlike pipes, platforms do not just create and push stuff out. They allow users to create and consume value.

Alex Moazed, founder and CEO of Applico, defines a platform as a business model that creates value by facilitating exchanges between two or more interdependent groups usually consumers and producers of a given value.[15] As a result of digital transformation, it is the predominant business model of the 21st century.

In an op-ed on MarketWatch,[16] Choudary, Van Alstyne and Parker further explain how business models are moving from pipes to platforms, leading to disruption of entire industries.

Platform[edit]

There are three elements to a successful platform business model.[17] The toolbox creates connection by making it easy for others to plug into the platform. This infrastructure enables interactions between participants. The magnet creates pull that attracts participants to the platform. For transaction platforms, both producers and consumers must be present to achieve critical mass. The matchmaker fosters the flow of value by making connections between producers and consumers. Data is at the heart of successful matchmaking, and distinguishes platforms from other business models.

Chen (2009) stated that the business model has to take into account the capabilities of Web 2.0, such as collective intelligence, network effects, user-generated content, and the possibility of self-improving systems. He suggested that the service industry such as the airline, traffic, transportation, hotel, restaurant, information and communications technology and online gaming industries will be able to benefit in adopting business models that take into account the characteristics of Web 2.0. He also emphasized that Business Model 2.0 has to take into account not just the technology effect of Web 2.0 but also the networking effect. He gave the example of the success story of Amazon in making huge revenues each year by developing an open platform that supports a community of companies that re-use Amazon’s on-demand commerce services.[18][need quotation to verify]

Impacts of platform business models[edit]

Jose van Dijck (2013) identifies three main ways that media platforms choose to monetize, which mark a change from traditional business models.[19] One is the subscription model, in which platforms charge users a small monthly fee in exchange for services. She notes that the model was ill-suited for those «accustomed to free content and services», leading to a variant, the freemium model. A second method is via advertising. Arguing that traditional advertising is no longer appealing to people used to «user-generated content and social networking», she states that companies now turn to strategies of customization and personalization in targeted advertising. Eric K. Clemons (2009) asserts that consumers no longer trust most commercial messages;[20] Van Dijck argues platforms are able to circumvent the issue through personal recommendations from friends or influencers on social media platforms, which can serve as a more subtle form of advertisement. Finally, a third common business model is monetization of data and metadata generated from the use of platforms.

Applications[edit]

Malone et al.[21] found that some business models, as defined by them, indeed performed better than others in a dataset consisting of the largest U.S. firms, in the period 1998 through 2002, while they did not prove whether the existence of a business model mattered.

In the healthcare space, and in particular in companies that leverage the power of Artificial Intelligence, the design of business models is particularly challenging as there are a multitude of value creation mechanisms and a multitude of possible stakeholders. An emerging categorization has identified seven archetypes.[22]

The concept of a business model has been incorporated into certain accounting standards. For example, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) utilizes an «entity’s business model for managing the financial assets» as a criterion for determining whether such assets should be measured at amortized cost or at fair value in its International Financial Reporting Standard, IFRS 9.[23][24][25][26] In their 2013 proposal for accounting for financial instruments, the Financial Accounting Standards Board also proposed a similar use of business model for classifying financial instruments.[27] The concept of business model has also been introduced into the accounting of deferred taxes under International Financial Reporting Standards with 2010 amendments to IAS 12 addressing deferred taxes related to investment property.[28][29][30]

Both IASB and FASB have proposed using the concept of business model in the context of reporting a lessor’s lease income and lease expense within their joint project on accounting for leases.[31][32][33][34][35] In its 2016 lease accounting model, IFRS 16, the IASB chose not to include a criterion of «stand alone utility» in its lease definition because «entities might reach different conclusions for contracts that contain the same rights of use, depending on differences between customers’ resources or suppliers’ business models.»[36] The concept has also been proposed as an approach for determining the measurement and classification when accounting for insurance contracts.[37][38] As a result of the increasing prominence the concept of business model has received in the context of financial reporting, the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), which advises the European Union on endorsement of financial reporting standards, commenced a project on the «Role of the Business Model in Financial Reporting» in 2011.[39]

Design[edit]

Business model design generally refers to the activity of designing a company’s business model. It is part of the business development and business strategy process and involves design methods. Massa and Tucci (2014)[40] highlighted the difference between crafting a new business model when none is in place, as it is often the case with academic spinoffs and high technology entrepreneurship, and changing an existing business model, such as when the tooling company Hilti shifted from selling its tools to a leasing model. They suggested that the differences are so profound (for example, lack of resource in the former case and inertia and conflicts with existing configurations and organisational structures in the latter) that it could be worthwhile to adopt different terms for the two. They suggest business model design to refer to the process of crafting a business model when none is in place and business model reconfiguration for process of changing an existing business model, also highlighting that the two process are not mutually exclusive, meaning reconfiguration may involve steps which parallel those of designing a business model.

Economic consideration[edit]

Al-Debei and Avison (2010) consider value finance as one of the main dimensions of BM which depicts information related to costing, pricing methods, and revenue structure. Stewart and Zhao (2000) defined the business model as «a statement of how a firm will make money and sustain its profit stream over time.»[41]

Component consideration[edit]