В истории Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 годов хватает драматических, трагических страниц. Одним из самых страшных была блокада Ленинграда. Кратко говоря, это история настоящего геноцида горожан, который растянулся едва не до самого конца войны. 27 января 2019 года исполняется 75 лет снятия блокады. Давайте еще раз вспомним, как все это происходило.

Наступление на «город Ленина»

Наступление на Ленинград началось сразу же, в 1941 году. Группировка немецко-финских войск успешно продвигалась вперед, взламывая сопротивление советских частей. Несмотря на отчаянное, ожесточенное сопротивление защитников города, уже к августу того же года все железные дороги, которые связывали город со страной, были перерезаны, в результате чего основная часть снабжения оказалась нарушена. Так когда началась блокада Ленинграда? Кратко перечислять события, которые этому предшествовали, можно долго. Но официальной датой считается 8 сентября 1941 года. Несмотря на жесточайшие по своему накалу бои на подступах к городу, «с наскока» взять гитлеровцы его не смогли. А потому 13 сентября начался артиллерийский обстрел Ленинграда, который фактически продолжался всю войну.

У немцев был простой приказ относительно города: стереть с лица земли. Все защитники должны были быть уничтожены. По другим сведениям, Гитлер просто опасался того, что при массированном штурме потери немецких войск будут неоправданно высоки, а потому и отдал приказ о начале блокады. В общем, суть блокады Ленинграда сводилась к тому, чтобы “город сам упал в руки, подобно созревшему плоду”.

Сведения о населении

Нужно помнить, что в блокированном городе на тот момент оставалось не менее 2,5 миллиона жителей. Среди них было около 400 тысяч детей. Практически сразу начались проблемы с пропитанием. Постоянный стресс и страх от бомбежек и обстрелов, нехватка медикаментов и продовольствия вскоре привели к тому, что горожане стали умирать. Было подсчитано, что за все время блокады на головы жителей города было сброшено не менее сотни тысяч бомб и около 150 тысяч снарядов. Все это приводило как к массовым смертям мирного населения, так и к катастрофическим разрушениям ценнейшего архитектурного и исторического наследия.

Первый год блокады

Самым тяжелым оказался первый год: немецкой артиллерии удалось разбомбить продовольственные склады, в результате чего город оказался практически полностью лишенным запасов продуктов питания. Впрочем, существует и прямо противоположное мнение. Дело в том, что к 1941 году количество жителей (зарегистрированных и приезжих) насчитывало порядка трех миллионов человек. Разбомбленные бадаевские склады просто физически не могли вместить такое количество продуктов. Многие современные историки вполне убедительно доказывают, что стратегического запаса на тот момент вовсе не было. Так что даже если бы склады не пострадали от действий немецкой артиллерии, это отсрочило наступление голода в лучшем случае на неделю. Кроме того, буквально несколько лет назад были рассекречены некоторые документы из архивов НКВД, касающиеся предвоенного обследования стратегических запасов города. Сведения в них рисуют крайне неутешительную картину: “Сливочное масло покрыто слоем плесени, запасы муки, гороха и прочих круп поражены клещом, полы хранилищ покрыты слоем пыли и пометом грызунов”.

С 10 по 11 сентября ответственные органы произвели полный переучет всего имевшегося в городе продовольствия. К 12 сентября был опубликован полный отчет, согласно которому в городе имелось: зерна и готовой муки примерно на 35 дней, запасов круп и макаронных изделий хватало на месяц, на этот же срок можно было растянуть запасы мяса. Масел оставалось ровно на 45 дней, зато сахара и готовых кондитерских изделий было припасено сразу на два месяца. Картофеля и овощей практически не было. Чтобы хоть как-то растянуть запасы муки, к ней добавляли по 12% размолотого солода, овсяной и соевой муки. Впоследствии туда же начали класть жмыхи, отруби, опилки и размолотую кору деревьев.

Как решался продовольственный вопрос?

С первых же сентябрьских дней в городе были введены продовольственные карточки. Все столовые и рестораны были сразу же закрыты. Скот, имевшийся на местных предприятиях сельского хозяйства, был тут же забит и сдан в заготовительные пункты. Все корма зернового происхождения были свезены на мукомольные предприятия и перемолоты в муку, которую впоследствии использовали для производства хлеба. У граждан, которые во время блокады находились в больницах, из талонов вырезали пайки на этот период. Этот же порядок распространялся на детей, которые находились в детских домах и учреждениях дошкольного образования. Практически во всех школах были отменены занятия. Для детей прорыв блокады Ленинграда был ознаменован не столь возможностью наконец-то поесть, сколько долгожданным началом занятий.

В общем-то, эти карточки стоили жизней тысячам людей, так как в городе резко участились случаи воровства и даже убийств, совершаемых ради их получения. В Ленинграде тех лет были нередкими случаи налетов и вооруженных ограблений булочных и даже продовольственных складов. С лицами, которых уличали в чем-то подобном, особо не церемонились, расстреливая на месте. Судов не было. Это объяснялось тем, что каждая украденная карточка стоила кому-то жизни. Эти документы не восстанавливались (за редчайшими исключениями), а потому кража обрекала людей на верную смерть.

Настроение жителей

В первые дни войны мало кто верил в возможность полной блокады, но готовиться к такому повороту событий начали многие. В первые же дни начавшегося немецкого наступления с полок магазинов было сметено все мало-мальски ценное, люди снимали все свои сбережения из Сберкассы. Опустели даже ювелирные магазины. Впрочем, начавшийся голод резко перечеркнул старания многих людей: деньги и драгоценности тут же обесценились. Единственной валютой стали продовольственные карточки (которые добывались исключительно путем разбоя) и продукты питания. На городских рынках одним из самых ходовых товаров были котята и щенята. Документы НКВД свидетельствуют, что начавшаяся блокада Ленинграда (фото которой есть в статье) постепенно начала вселять в людей тревогу. Изымалось немало писем, в которых горожане сообщали о бедственном положении в Ленинграде. Они писали, что на полях не осталось даже капустных листьев, в городе уже нигде не достать старой мучной пыли, из которой раньше делали клей для обоев.

К слову говоря, в самую тяжелую зиму 1941 года в городе практически не осталось квартир, стены которых были бы оклеены обоями: голодные люди их попросту обрывали и ели, так как другой еды у них не было. Трудовой подвиг ленинградцев Несмотря на всю чудовищность сложившегося положения, мужественные люди продолжали работать. Причем работать на благо страны, выпуская немало образцов вооружения. Они даже умудрялись ремонтировать танки, делать пушки и пистолеты-пулеметы буквально из «подножного материала». Все полученное в столь сложных условиях вооружение тут же использовалось для боев на подступах к непокоренному городу. Но положение с продуктами питания и медикаментами осложнялось день ото дня. Вскоре стало очевидно, что только Ладожское озеро может спасти жителей. Как же связано оно и блокада Ленинграда? Кратко говоря, это знаменитая Дорога жизни, которая была открыта 22 ноября 1941 года. Как только на озере образовался слой льда, который теоретически мог выдержать груженные продуктами машины, началась их переправа .

Начало голода

Голод приближался неумолимо. Уже 20 ноября 1941 года норма хлебного довольствия составляла всего лишь 250 граммов в день для рабочих. Что же касается иждивенцев, женщин, детей и стариков, то им полагалось вдвое меньше. Сперва рабочие, которые видели состояние своих родных и близких, приносили свои пайки домой и делились с ними. Но вскоре этой практике был положен конец: людям было приказано съедать свою порцию хлеба непосредственно на предприятии, под присмотром. Вот так проходила блокада Ленинграда. Фото показывают, насколько же были истощены люди, которые на тот момент находились в городе. На каждую смерть от вражеского снаряда приходилась сотня людей, которые умерли от страшного голода. При этом нужно понимать, что под “хлебом” в этом случае понимался небольшой кусок клейкой массы, в которой было намного больше отрубей, опилок и прочих наполнителей, нежели самой муки. Соответственно, питательная ценность такой пищи была близка к нулевой. Когда был осуществлен прорыв блокады Ленинграда, люди, впервые за 900 дней получившие свежий хлеб, нередко от счастья падали в обморок. В довершение всех проблем полностью вышла из строя система городского водоснабжения, в результате чего горожанам приходилось носить воду из Невы. Кроме того, сама зима 1941 года выдалась на редкость суровой, так что медики просто не справлялись с наплывов обмороженных, простывших людей, иммунитет которых оказался неспособен противостоять инфекциям.

К началу зимы хлебная пайка была увеличена почти вдвое. Увы, но этот факт объяснялся не прорывом блокады и не восстановлением нормального снабжения: просто к тому времени половина всех иждивенцев уже погибла. Документы НКВД свидетельствуют о том факте, что голод принял совершенно невероятные формы. Начались случаи людоедства, причем многие исследователи считают, что официально было зафиксировано не более трети из них.

Особенно плохо в то время приходилось детям. Многие из них были вынуждены подолгу оставаться одни в пустых, холодных квартирах. Если их родители умирали от голода на производстве или же в случае их смерти при постоянных обстрелах, дети по 10-15 дней проводили в полном одиночестве. Чаще всего они также умирали. Таким образом, дети блокады Ленинграда многое вынесли на своих хрупких плечах. Фронтовики вспоминают, что среди толпы семи-восьмилетних подростков в эвакуации всегда выделялись именно ленинградцы: у них были жуткие, уставшие и слишком взрослые глаза.

Уже к середине зимы 1941 года на улицах Ленинграда не осталось кошек и собак, даже ворон и крыс практически не было. Животные уяснили, что от голодных людей лучше держаться подальше. Все деревья в городских скверах лишились большей части коры и молодых веток: их собирали, перемалывали и добавляли в муку, лишь бы хоть немного увеличить ее объем. Блокада Ленинграда длилась на тот момент меньше года, но при осенней уборке на улицах города было найдено 13 тысяч трупов.

Дорога Жизни

Конец этой смертельно опасной карусели положило только освобождение Ленинграда от блокады. Дорога номер 101, как тогда называли этот путь, позволила не только поддерживать хотя бы минимальную продовольственную норму, но и вывезти из блокированного города многие тысячи людей. Немцы постоянно старались прервать сообщение, не жалея для этого снарядов и горючего для самолетов. К счастью, им это не удалось, а на берегах Ладожского озера сегодня стоит монумент “Дорога Жизни”, а также открыт музей блокады Ленинграда, в котором собрано множество документальных свидетельств тех страшных дней. Во многом успех с организацией переправы объяснялся тем, что Советское командование быстро привлекло для обороны озера истребительную авиацию. В зимнее время зенитные батареи монтировались прямо на льду. Заметим, что принятые меры дали очень положительные результаты: так, уже 16 января в город было доставлено более 2,5 тысячи тонн продовольствия, хотя запланирована была доставка только двух тысяч тонн.

Так когда произошло долгожданное снятие блокады Ленинграда? Как только под Курском немецкой армии было нанесено первое крупное поражение, руководство страны стало думать о том, как освободить заточенный город. Непосредственно снятие блокады Ленинграда началось 14 января 1944 года. Задачей войск был прорыв немецкой обороны в самом тонком ее месте для восстановления сухопутного сообщения города с остальной территорией страны. К 27 января начались ожесточенные бои, в которых советские части постепенно одерживали верх. Это был год снятия блокады Ленинграда. Гитлеровцы были вынуждены начать отступление. Вскоре оборона была прорвана на участке длиной около 14 километров. По этому пути в город немедленно пошли колонны грузовиков с продовольствием. Так сколько длилась блокада Ленинграда? Официально считается, что она продолжалась 900 дней, но точная продолжительность — 871 день. Впрочем, этот факт ни в малейшей степени не умаляет решимости и невероятного мужества его защитников.

День освобождения

Сегодня день снятия блокады Ленинграда — это 27 января. Эта дата — не праздничная. Скорее, это постоянное напоминание о тех ужасающих событиях, через которые были вынуждены пройти жители города. Справедливости ради стоит сказать, что настоящий день снятия блокады Ленинграда — 18 января, так как коридор, о котором мы говорили, получилось пробить именно в тот день. Та блокада унесла более двух миллионов жизней, причем умирали там в основном женщины, дети и старики. Пока память о тех событиях жива, ничего подобного не должно повториться в мире! Вот вся блокада Ленинграда кратко. Конечно, описать то страшное время можно достаточно быстро, вот только блокадники, которые смогли его пережить, вспоминают те ужасающие события каждый день.

По материалам сайта SYL.ru

Блокада Ленинграда – военная блокада города Ленинграда (ныне Санкт-Петербург) немецкими, финскими и испанскими войсками с участием добровольцев из Северной Африки, Европы и военно-морских сил Италии в период Великой Отечественной войны (1941-1945).

Блокада Ленинграда – одна из самых трагичных и, в то же время, героических страниц в истории Великой Отечественной войны. Длилась с 8 сентября 1941 г. по 27 января 1944 г. (блокадное кольцо было прорвано 18 января 1943 г.) – 872 дня.

Накануне блокады в городе не было достаточного количества продовольствия и топлива для длительной осады. Это привело к тотальному голоду и как следствие к сотням тысяч смертей среди жителей.

Блокада Ленинграда проводилась не с целью капитуляции города, а для того, чтобы было проще уничтожить все находящееся в окружении население.

Блокада Ленинграда

Когда в 1941 г. фашистская Германия напала на СССР, советскому руководству стало ясно, что Ленинград рано или поздно окажется одной из ключевых фигур в немецко-советском противостоянии.

В связи с этим власти распорядились эвакуировать город, для чего требовалось вывезти всех его жителей, предприятия, военную технику и предметы искусства. Однако на блокаду Ленинграда никто не рассчитывал.

У Адольфа Гитлера, согласно свидетельству его приближенных, к оккупации Ленинграда был особый подход. Он не столько хотел его захватить, сколько просто стереть с лица земли. Таким образом он планировал сломить моральный дух всех советских граждан, для которых город был настоящей гордостью.

Накануне блокады

Согласно плану Барбаросса, немецкие войска должны были оккупировать Ленинград не позднее июля. Видя стремительное наступление противника советская армия спешно строила оборонительные сооружения и готовилась к эвакуации города.

Ленинградцы охотно помогали красноармейцам строить укрепления, а также активно записывались в ряды народного ополчения. Все люди в едином порыве сплотились вместе в борьбе с захватчиками. В результате, ленинградский округ пополнился еще примерно 80 000 бойцами.

Иосиф Сталин отдал приказ защищать Ленинград до последней капли крови. В связи с этим помимо наземных укреплений, проводилась и противовоздушная оборона. Для этого были задействованы зенитные орудия, авиация, прожектора и радиолокационные установки.

Интересен факт, что наспех организованное ПВО возымело большой успех. Буквально на 2-й день войны ни один немецкий истребитель не смог прорваться в воздушное пространство города.

В то первое лето было совершено 17 налетов, в которых фашисты задействовали свыше 1500 самолетов. К Ленинграду прорвались только 28 самолетов, а 232 из них были сбиты советскими солдатами. Тем не менее, 10 июля 1941 г. армия Гитлера уже находились в 200 км от города на Неве.

Первый этап эвакуации

Через неделю после начала войны, 29 июня 1941 г., из Ленинграда удалось эвакуировать около 15 000 детей. Однако это был только первый этап, поскольку правительство планировало вывезли из города до 390 000 ребят.

Большинство детей эвакуировали на юг ленинградской области. Но именно туда начали свое наступление фашисты. По этой причине, около 170 000 девочек и мальчиков пришлось отправить обратно в Ленинград.

Стоит заметить, что город должны были покинуть и сотни тысяч взрослых людей, параллельно с предприятиями. Жители неохотно покидали свои дома, сомневаясь в том, что война может затянуться надолго. Однако сотрудники специально образованных комитетов следили за тем, чтобы люди и техника вывозились как можно быстрее, посредством шоссе и железной дороги.

Если верить данным комиссии, до начала блокады Ленинграда, из города эвакуировали 488 000 человек, а также 147 500 прибывших в него беженцев. 27 августа 1941 г. железнодорожное сообщение между Ленинградом и остальной частью СССР было прервано, а 8 сентября было прекращено и сухопутное сообщение. Именно эта дата стала официальной точкой отсчета блокады города.

Первые дни блокады Ленинграда

По приказу Гитлера его войскам предстояло взять Ленинград в кольцо и регулярно подвергать его обстрелам из тяжелых орудий. Немцы планировали постепенно сжимать кольцо и тем самым лишить город любого снабжения.

Фюрер думал, что Ленинград не выдержит долгой осады и быстро капитулирует. Он и подумать не мог, что все его намеченные планы потерпят фиаско.

Известие о блокаде Ленинграда разочаровало немцев, которые не хотели находиться в холодных окопах. Чтобы как-то ободрить солдат, Гитлер объяснил свои действия нежеланием напрасно расходовать человеческие и технические ресурсы Германии. Он добавил, что вскоре в городе начнется голод, и жители просто вымрут.

Справедливо отметить, что в какой-то мере немцам была невыгодна капитуляция, поскольку им бы пришлось обеспечивать пленных продовольствием, пусть и в самом минимальном количестве. Гитлер, наоборот, побуждал воинов нещадно бомбить город, уничтожая гражданское население и всю его инфраструктуру.

С течением времени неизбежно возникали вопросы относительно того, можно ли было избежать тех катастрофических последствий, которые принесла блокада Ленинграда.

Сегодня, имея документы и свидетельства очевидцев, не вызывает сомнений тот факт, что у ленинградцев не было шансов выжить, если бы они согласились добровольно сдать город. Фашистам просто не нужны были пленники.

Жизнь блокадного Ленинграда

Советское правительство намеренно не раскрывало блокадникам реальную картину положения дел, чтобы не подорвать их дух и надежду на спасение. Информация о ходе войны подавалась максимально кратко.

В скором времени в городе наступил большой дефицит продуктов питания, вследствие чего наступил масштабный голод. Вскоре в Ленинграде пропало электричество, а затем вышли из строя и водопровод с канализацией.

Город бесконечно подвергался активным обстрелам. Люди находились в тяжелом физическом и моральном состоянии. Каждый как мог искал для себя пропитание, наблюдая за тем, как ежедневно от недоедания умирают десятки или сотни людей. Еще в самом начале фашисты смогли разбомбить Бадаевские склады, где в огне сгорели сахар, мука и масло.

Ленинградцы безусловно понимали, чего они лишились. На тот момент в Ленинграде проживало примерно 3 млн человек. Снабжение города всецело зависело от привозных продуктов, которые позже удалось поставлять по знаменитой Дороге жизни.

Люди получали хлеб и другие продукты по карточкам, выстаиваясь в огромные очереди. Тем не менее, ленинградцы продолжали трудиться на заводах, а дети ходить в школу. Позднее, пережившие блокаду очевидцы признаются, что выжить в основном смогли те, кто чем-то занимался. А те люди, которые хотели сэкономить силы, оставаясь дома, обычно умирали в своих домах.

Дорога жизни

Единственным дорожным сообщением между Ленинградом и остальным миром оказалось Ладожское озеро. Прямо вдоль побережья озера спешно разгружали доставленные продукты, поскольку Дорога жизни постоянно обстреливалась немцами.

Советским солдатам удавалось привести только незначительную часть продовольствия, однако если бы не это, смертность горожан оказалась бы в разы больше.

Зимой, когда судна не могли привозить товар, грузовые машины доставляли продовольствие прямо по льду. Интересен факт, что в город грузовики везли продукты, а обратно вывозили людей. При этом, немало машин проваливались под лед и шли на дно.

Детский вклад в освобождение Ленинграда

Дети с большим энтузиазмом откликнулись на призыв о помощи со стороны местной власти. Они собирали металлолом для изготовления военной техники и снарядов, емкости для горючих смесей, теплые вещи для красноармейцев, а также помогали медикам в больницах.

Ребята дежурили на крышах зданий, готовые в любой момент потушить падающие зажигательные бомбы и тем самым спасти постройки от возгорания. «Часовые ленинградских крыш» – такое прозвище они получили в народе.

Когда во время бомбежек все убегали в укрытия, «часовые», наоборот, поднимались на крыши, для тушения падающих снарядов. Кроме этого измучанные и обессиленные дети становились изготавливали на токарных станках боеприпасы, рыли окопы и строили различные укрепления.

За годы блокады Ленинграда погибло огромное количество детей, которые своими действиями воодушевляли взрослых и солдат.

Подготовка к решительным действиям

Летом 1942 г. Леонида Говорова назначили командующим всеми силами Ленинградского фронта. Он много времени изучал разные схемы и строил расчеты для улучшения обороны.

Говоров изменил месторасположение артиллерии, что повысило дальность стрельбы по позициям противника.

Также фашистам пришлось задействовать существенно больше боеприпасов для борьбы с советской артиллерией. В итоге на Ленинград примерно в 7 раз реже начали падать снаряды.

Командир очень скрупулезно разрабатывал план прорыва блокады Ленинграда, постепенно отводя с передовой линии отдельные части для тренировки бойцов.

Дело в том, что немцы расположились на 6-метровом берегу, который полностью залили водой. В результате, склоны стали похожи на ледяные возвышенности, взобраться на которые было очень непросто.

При этом до обозначенного места русским солдатам стоило преодолеть около 800 м по замерзшей реке.

Поскольку воины были обессилены от затянувшейся блокады, во время наступления Говоров приказал воздержаться от криков «Ура!!!», чтобы не сберечь силы. Вместо этого штурм красноармейцев проходил под музыку оркестра.

Прорыв и снятие блокады Ленинграда

Местное командование решило начать прорыв блокадного кольца 12 января 1943 г. Данную операцию назвали «Искрой». Атака русской армии началась с продолжительного обстрела немецких укреплений. После этого фашисты подверглись тотальным авиаобстрелам.

Тренировки, проходившие на протяжении нескольких месяцев, не прошли даром. Человеческие потери в рядах советских войск оказались минимальными. Добравшись до обозначенного места наши бойцы с помощью «кошек», багров и длинных лестниц, быстро взобрались по ледовой стене, вступив с противником в схватку.

Утром 18 января 1943 г. в северной области Ленинграда произошла встреча советских подразделений. Совместными усилиями они освободили Шлиссельбург и сняли блокаду с побережья Ладожского озера. Полное снятие блокады Ленинграда произошло 27 января 1944 г.

Итоги блокады

Согласно утверждению политического философа Майкла Уолцера, «в осаде Ленинграда погибло больше гражданских лиц, чем в аду Гамбурга, Дрездена, Токио, Хиросимы и Нагасаки, вместе взятых».

За годы блокады Ленинграда погибло, по разным данным, от 600 000 до 1,5 млн человек. Интересен факт, что только 3 % из них погибли от обстрелов, тогда как остальные 97 % умерли от голода.

По причине жуткого голода в городе фиксировались неоднократные случаи каннибализма, как умерших естественной смертью людей, так и в результате убийств.

Фото блокады Ленинграда

Теперь вы знаете что представляет собой Блокада Ленинграда. Если вам понравилась данная статья или вы вообще любите историю, – подписывайтесь на сайт interesnyefakty.org.

Понравился пост? Нажми любую кнопку:

Блокада Ленинграда — это период осады города Ленинграда в Великую отечественную войну, которая продолжалась почти 900 дней (872, если точнее).

Блокада началась 8 сентября 1941 года и была снята 27 января 1944 года. В планы Гитлера входило полностью уничтожить город и его жителей.

Ленинград был важным городом для СССР. В городе и его окрестностях в 1941 году проживало почти 3 миллиона человек. В нём были расположены военные заводы, которые производили снаряды, мины, танки, самолёты и др. Из Ленинграда в другие города России шли железные дороги.

В результате блокады и обороны города погибли 632 тысячи человек солдат и мирного населения.

Кратко об основных событиях до блокады

В соответствии с планом «Барбаросса» Гитлер намеревался провести молниеносную войну (блицкриг).

Армия Гитлера начала наступление на Северном направлении 10 июля 1941 года. Период этих военных действий называют Ленинградской битвой. Сюда входят все битвы в окрестностях Ленинграда, которые проходили с 10 июля 1941 года по 9 августа 1944 года.

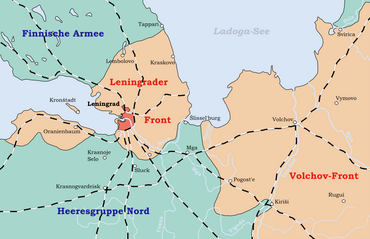

Источник: Hellerick, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Группа войск «Север», которой командовал генерал-фельдмаршал Вильгельм фон Лееб, должна была атаковать с востока и юго-востока.

Финская карельская и Юго-восточная армии должны были создать фронт на Карельском перешейке, к северу от Ленинграда, а также продвигаться к Петрозаводску (между Ладожским и Онежским озёрами). На подходе к Ленинграду они должны были объединиться с гитлеровской армией.

Со стороны Красной армии участие в Ленинградской битве принимали:

- Северный фронт (позже разделённый на Карельский и Ленинградский фронты),

- Северо-Западный фронт,

- Волховский фронт,

- Балтийский флот,

- военные флотилии на Чудском, Онежском и Ладожском озёрах.

10 июля началось одновременное наступление вражеских войск.

Красная армия вступила в бой с финскими войсками на Карельском перешейке 31 июля 1941 года. Но к 1 сентября врага на этом направлении удалось остановить. У Петрозаводска фашистская армия дошла до реки Свирь, где была остановлена советскими войсками.

В августе войска воевали уже на ближних подступах к Ленинграду. 16 августа был захвачен Кингисепп (115 км по прямой от Ленинграда).

30 августа 1941 года фашистские войска взяли под контроль железную дорогу, которая шла из Ленинграда в Москву.

8 сентября 1941 года враг захватил город Шлиссельбург (к востоку от Ленинграда). Таким образом, проход к Ленинграду по суше был полностью под контролем врага. Началась блокада Ленинграда.

Блокадный Ленинград

Фашисты уже с начала сентября начали активно обстреливать и бомбить Ленинград. Гитлер намеривался войти в пустой город: ни население, ни сам город фашистам был не нужен.

8 сентября одна из бомб упала на Бадаевские склады. В результате пожара тонны муки и сахара сгорели.

Зима 1941 года стала самой тяжёлой. Ударили сильные морозы, закончились запасы еды, перестало работать электричество, остановились трамваи и троллейбусы.

Люди жгли печки «буржуйки». На растопку шло всё — мебель, книги, деревянные дома. За водой с вёдрами ходили к реке.

Источник: RIA Novosti archive, image #907 / Boris Kudoyarov / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Ещё 17 июля в Ленинграде вводят карточки, с помощью которых можно было получить в магазинах еду. А с 1 сентября стало запрещено продавать товары: их можно было получить только по карточкам.

Причём норма дневного пайка постоянно снижалась. Так, к 20 ноября из еды ленинградцы могли получить только хлеб: 250 грамм хлеба в день для рабочих (а по некоторым данным — 200 гр.), остальным – 125 граммов.

Источник: RIA Novosti archive, image #46124 / Alexey Varfolomeev / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Из-за нехватки муки хлеб делали из жмыха, мучной пыли и целлюлозы. Ели и столярный клей, и цветы (из них получались лепёшки), ботву и корни растений. В еду шёл и корм для птиц.

Люди умирали от дистрофии, цинги, туберкулёза.

Источник: I, George Shuklin, CC BY 2.5 , via Wikimedia Commons

Сообщение с городом происходило только через воздушное пространство с помощью самолётов и по Ладожскому озеру. Путь по озеру называли «Дорогой жизни».

«Дорога жизни» блокадного Ленинграда

«Дорога жизни» была жизненно необходима осаждённому Ленинграду. В город доставляли боеприпасы, еду, топливо. По этой же дороге эвакуировали людей.

12 сентября приплыли первыми корабли с зерном и оружием. Навигация была очень сложной задачей: Ладожское озеро всегда было неблагоприятным местом для судоходства из-за сильного ветра и волн.

Когда пришла зима, навигация прекратилась. Нужно было дождаться сильных морозов, чтобы лёд замёрз.

Первым грузом стали санные упряжки с 63 тоннами муки, которые прошли по льду 21 ноября 1941 года. Доставка груза и эвакуация людей были крайне опасными занятиями. Фашистские войска постоянно бомбили и обстреливали этот путь. Второй проблемой был незамёрзший лёд, который не выдерживал веса груза.

Источник: Марков Сергей, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Для обеспечения города топливом и электричеством в июне 1942 года советская армия проложила трубу и кабель по дну Ладожского озера. Город стал получать горючее и электроэнергию.

Ленинград сопротивлялся, на заводах 75% рабочих составляли женщины. Мужчины сражались на фронте. Главной задачей по-прежнему было прорвать блокаду и отбросить врага.

Операция «Искра»

2 декабря 1942 года в Ставке Верховного Главнокомандующего принято решение прорвать фашистскую оборону и объединить два фронта — Ленинградский и Волховский.

Эту операцию назвали «Искра». За её проведение отвечали маршал К. Е. Ворошилов и генерал Г. К. Жуков. Операция проводилась с 12 по 30 января 1943 года.

Источник: Memnon335bc, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

12 января 1943 года советская армия начала наступление. 18 января двум фронтам удалось прорвать блокаду и объединиться. Тогда же враг был выбит из Шлиссельбурга и с южного берега Ладожского озера.

От Шлиссельбурга за 18 дней была построена железная дорога в Ленинград. Её назвали «Дорогой победы». В город стали поставлять топливо, электричество, продовольствие. Наладилась работа военных предприятий.

Полностью освободить город советским войскам удалось 27 января 1944 года после 872 дней блокады. В тот же день в городе был победный салют.

Почему так долго длилась блокада Ленинграда

На подступах к Ленинграду фашистская армия пыталась занять Пулковские высоты. Эти холмы расположены к югу от Ленинграда и должны были стать точкой для обстрела из артиллерии всего города с целью его полного уничтожения. Но яростное сопротивление советской армии не позволило фашистам занять эту выгодную точку.

Источник: RIA Novosti archive, image #765 / Boris Kudoyarov / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Героические действия советской обороны под Ленинградом (в Южном Приладожье) лишили фашистские войска значительной части боеприпасов, танков и солдат. Им пришлось срочно укреплять другие фронта. Часть войск из-под Ленинграда была перекинута на другие позиции. Дальнейшее наступление на город было прекращено.

Фашистские войска сфокусировались на фронтах южнее Ленинграда, а сам город был окружён и каждодневно подвергался мощнейшим артиллерийским обстрелам и бомбежке.

По плану Гитлера, следовало уничтожить город и всех его жителей. Это должно было лишить советскую армию военных заводов и подорвать геройский дух.

Несмотря на отсутствие электричества, нехватку продовольствия, жесточайший голод и холод, город продолжал функционировать и сопротивляться захватчикам. Заводы работали, люди устанавливали баррикады и препятствия для танков.

Осаждённый Ленинград героически продолжал производить боеприпасы для советской армии, ремонтировал технику и оружие для солдат.

Россия, Санкт-Петербург. Дом №13 на Глазовской улице (совр. ул. Константина Заслонова) после артобстрела.

Источник: RIA Novosti archive, image #95845 / Vsevolod Tarasevich / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Были сформированы народные ополчения — то есть группы жителей города. Они сооружали огневые точки для ответного обстрела, укрепляли оборону.

Работали и театры: без электричества, в мороз, иной раз при бомбёжках. В блокадном Ленинграде был снят легендарный фильм режиссёра Виктора Эйсымонта «Жила-была девочка» о судьбах двух детей 7 и 5 лет (уже после прорыва блокады некоторые сцены снимались в центре города). В осаждённом городе жила и творила поэтесса Ольга Бергольц.

«…Я говорю с тобой под свист снарядов,

угрюмым заревом озарена.

Я говорю с тобой из Ленинграда,

страна моя, печальная страна…».Ольга Бергольц

Наперекор планам фашистов, город не только не умер, он — жил. Жил и яростно сопротивлялся.

Интересные факты

- В Ленинграде были установлены громкоговорители. На улице или дома по радио люди могли узнать об обстановке в городе. Вещание шло круглосуточно, а когда дикторы молчали, то было слышно звук метронома. Жители города говорили, что этот звук —живое сердца Ленинграда, которое бьётся.

- На берегу Ладожского озера стоит копия «Полуторки» — машины, которую использовали для перевозки грузов в осаждённый город и эвакуации населения.

- На Пискарёвском кладбище в Санкт-Петербурге стоит стелла — памятник жителям и защитникам Ленинграда. На стелле высечен отрывок из стихотворения Ольги Бергольц:

«Здесь лежат ленинградцы.

Здесь горожане — мужчины, женщины, дети.

Рядом с ними солдаты-красноармейцы.

Всею жизнью своею

они защищали тебя, Ленинград,

колыбель революции.

Их имен благородных мы здесь перечислить не сможем,

так их много под вечной охраной гранита.

Но знай, внимающий этим камням,

никто не забыт и ничто не забыто».

- Начало своей седьмой симфонии советский композитор Дмитрий Шостакович написал в блокадном Ленинграде. А конец — уже в эвакуации. 9 августа 1942 года симфонию, которую композитор назвал «Ленинградской», исполнили в зале Ленинградской филармонии. Она передавалась также по громкоговорителям и радио всем ленинградцам.

- Многие жители блокадного Ленинграда, несмотря на жесточайшие условия, сдавали донорскую кровь. Она предназначалась для раненных солдат Советской армии.

- Одно из правил блокадного Ленинграда — «не ложиться». По воспоминаниям блокадников из-за дистрофии, цинги и обессилевшего организма те, кто ложился, уже не вставал.

- Цифры о количестве погибших разные. По данных некоторым историков, в Ленинграде погибли 632 тысячи человек. Из этого числа только 3% были убиты при артобстреле и бомбёжке, остальные умерли от голода.

- Самым известным воспоминанием о блокадном Ленинграде стал дневник Тани Савичевой. В нём всего 6 предложений: «Лека умер 17 марта в 5 час. утра 1942 г. Мама 13 мая в 7.30 утра 1942 г. Савичевы умерли все. Умерли. Все. Осталась одна Таня». Таня Савичева тоже умерла. От дистрофии и туберкулёза, но уже в больнице после того, как она была эвакуирована.

Читайте подробнее про Операцию «Барбаросса». Узнайте также про Сталинградскую битву.

8 сентября 2011 года исполняется 70 лет со дня начала блокады Ленинграда.

Блокада города Ленинграда (ныне Санкт‑Петербург) во время Великой Отечественной войны проводилась немецкими войсками с 8 сентября 1941 года по 27 января 1944 года с целью сломить сопротивление защитников города и овладеть им.

Наступление фашистских войск на Ленинград, захвату которого германское командование придавало важное стратегическое и политическое значение, началось 10 июля 1941 года. В августе тяжелые бои шли уже на подступах к городу. 30 августа немецкие войска перерезали железные дороги, связывавшие Ленинград со страной. 8 сентября 1941 года немецко‑фашистские войска овладели Шлиссельбургом и отрезали Ленинград от всей страны с суши. Началась почти 900‑дневная блокада города, сообщение с которым поддерживалось только по Ладожскому озеру и по воздуху.

Потерпев неудачу в попытках прорвать оборону советских войск внутри блокадного кольца, немцы решили взять город измором. По всем расчетам германского командования, Ленинград должен был быть стерт с лица земли, а население города умереть от голода и холода. Стремясь осуществить этот план, противник вел варварские бомбардировки и артиллерийские обстрелы Ленинграда: 8 сентября, в день начала блокады, произошла первая массированная бомбардировка города. Вспыхнуло около 200 пожаров, один из них уничтожил Бадаевские продовольственные склады. В сентябре‑октябре вражеская авиация совершала в день по несколько налетов. Целью противника было не только помешать деятельности важных предприятий, но и создать панику среди населения. Для этого в часы начала и окончания рабочего дня велся особенно интенсивный артобстрел. Всего за период блокады по городу было выпущено около 150 тысяч снарядов и сброшено свыше 107 тысяч зажигательных и фугасных бомб. Многие погибли во время обстрелов и бомбежек, множество зданий было разрушено.

Убежденность в том, что врагу не удастся захватить Ленинград, сдерживала темпы эвакуации людей. В блокированном городе оказалось более двух с половиной миллионов жителей, в том числе 400 тысяч детей. Продовольственных запасов было мало, пришлось использовать пищевые суррогаты. С начала введения карточной системы нормы выдачи продовольствия населению Ленинграда неоднократно сокращались. В ноябре‑декабре 1941 года рабочий мог получить лишь 250 граммов хлеба в день, а служащие, дети и старики ‑ всего 125 граммов. Когда 25 декабря 1941 года впервые была сделана прибавка хлебного пайка ‑ рабочим ‑ на 100 граммов, остальным ‑ на 75, истощенные, изможденные люди вышли на улицы, чтобы поделиться своей радостью. Это незначительное увеличение нормы выдачи хлеба давало пусть слабую, но надежду умирающим от голода людям.

Осень‑зима 1941‑1942 годов ‑ самое страшное время блокады. Ранняя зима принесла с собой холод ‑ отопления, горячей воды не было, и ленинградцы стали жечь мебель, книги, разбирали на дрова деревянные постройки. Транспорт стоял. От дистрофии и холода люди умирали тысячами. Но ленинградцы продолжали трудиться ‑ работали административные учреждения, типографии, поликлиники, детские сады, театры, публичная библиотека, продолжали работу ученые. Работали 13‑14‑летние подростки, заменившие ушедших на фронт отцов.

Борьба за Ленинград носила ожесточенный характер. Был разработан план, предусматривавший мероприятия по укреплению обороны Ленинграда, в том числе противовоздушной и противоартиллерийской. На территории города было сооружено свыше 4100 дотов и дзотов, в зданиях оборудовано 22 тысячи огневых точек, на улицах установлено свыше 35 километров баррикад и противотанковых препятствий. Триста тысяч ленинградцев участвовало в отрядах местной противовоздушной обороны города. Днем и ночью они несли свою вахту на предприятиях, во дворах домов, на крышах.

В тяжелых условиях блокады трудящиеся города давали фронту вооружение, снаряжение, обмундирование, боеприпасы. Из населения города было сформировано 10 дивизий народного ополчения, 7 из которых стали кадровыми.

(Военная энциклопедия. Председатель Главной редакционной комиссии С.Б. Иванов. Воениздат. Москва. в 8 томах ‑2004 г.г. ISBN 5 ‑ 203 01875 –

Осенью на Ладожском озере из‑за штормов движение судов было осложнено, но буксиры с баржами пробивались в обход ледяных полей до декабря 1941 года, некоторое количество продовольствия доставлялось самолетами. Твердый лед на Ладоге долго не устанавливался, нормы выдачи хлеба были вновь сокращены.

22 ноября началось движение автомашин по ледовой дороге. Эта транспортная магистраль получила название «Дорога жизни». В январе 1942 года движение по зимней дороге уже было постоянным. Немцы бомбили и обстреливали дорогу, но им не удалось остановить движение.

Зимой началась эвакуация населения. Первыми вывозили женщин, детей, больных, стариков. Всего эвакуировали около миллиона человек. Весной 1942 года, когда стало немного легче, ленинградцы начали очищать, убирать город. Нормы выдачи хлеба увеличились.

Летом 1942 года по дну Ладожского озера был проложен трубопровод для снабжения Ленинграда горючим, осенью — энергетический кабель.

Советские войска неоднократно пытались прорвать кольцо блокады, но добились этого лишь в январе 1943 года. Южнее Ладожского озера образовался коридор шириной 8‑11 километров. По южному берегу Ладоги за 18 дней была построена железная дорога протяженностью 33 километра и возведена переправа через Неву. В феврале 1943 года по ней в Ленинград пошли поезда с продовольствием, сырьем, боеприпасами.

Блокада Ленинграда была снята полностью в ходе Ленинградско‑Новгородской операции 1944 года. В результате мощного наступления советских войск немецкие войска были отброшены от Ленинграда на расстояние 60‑100 км.

27 января 1944 года стало днем полного освобождения Ленинграда от блокады. В этот день в Ленинграде был дан праздничный салют.

Блокада Ленинграда длилась почти 900 дней и стала самой кровопролитной блокадой в истории человечества: от голода и обстрелов погибло свыше 641 тысячи жителей (по другим данным, не менее одного миллиона человек).

Подвиг защитников города был высоко оценен: свыше 350 тысяч солдат, офицеров и генералов Ленинградского фронта были награждены орденами и медалями, 226 из них присвоено звание Героя Советского Союза. Медалью «За оборону Ленинграда», которая была учреждена в декабре 1942 года, было награждено около 1,5 миллиона человек.

За мужество, стойкость и невиданный героизм в дни тяжелой борьбы с немецко‑фашистскими захватчиками город Ленинград 20 января 1945 года был награжден орденом Ленина, а 8 мая 1965 года получил почетное звание «Город‑Герой».

Федеральным законом «О днях воинской славы и памятных дат России» от 13 марта 1995 года 27 января установлен как День воинской славы России ‑ День снятия блокады города Ленинграда (1944 год).

Памяти жертв блокады и погибших участников обороны Ленинграда посвящены мемориальные ансамбли Пискаревского кладбища и Серафимского кладбища, вокруг города по бывшему блокадному кольцу фронта создан Зеленый пояс Славы.

Материал подготовлен на основе информации открытых источников

Блокада Ленинграда началась 8 сентября 1941 года. В планах гитлеровских оккупантов было стереть с лица земли город и уничтожить всех ленинградцев. Осаждённый Ленинград 872 дня боролся за жизнь. Ежедневные бомбардировки и страшный голод не сломили его жителей, город продолжал жить и бороться. Оборона Ленинграда и блокада — урок беспримерного мужества всей стране, всему миру. Ленинград был окончательно освобождён от блокады 27 января 1944 года.

Планы нацистов

Сразу после начала вторжения в СССР гитлеровское командование объявило, что Ленинград необходимо стереть с лица земли. В конце сентября 1941 года А. Гитлер издал соответствующую директиву, где было сказано буквально следующее:

«1. Фюрер принял решение стереть город Петербург с лица земли. После разгрома советской армии существование этого города не будет иметь никакого смысла…

3. Предлагается плотно блокировать город и сровнять его с землёй с помощью артиллерии всех калибров и непрерывных бомбардировок с воздуха. Если в результате создавшейся в городе обстановки последуют заявления о сдаче города, они должны быть отклонены».

Из директивы «О будущем города Петербурга»

Население, которое, по мнению А. Гитлера, могло попытаться покинуть город, следовало с помощью оружия загонять обратно в кольцо блокады. По планам нацистов, Ленинград должен был погибнуть.

Начало блокады

До войны Ленинград был крупнейшим центром советской промышленности, средоточием культурных ценностей. В политическом смысле город считался «колыбелью революции». Все эти факторы предопределяли гитлеровский план первоочередного захвата Северной столицы. Финская армия должна была помочь немцам взять Ленинград и соединиться с войсками вермахта (группой армий «Север») у Финского залива и восточнее Ладожского озера. После того как группа армий «Север» вышла к Пскову, наступление на Карельском перешейке начали финские дивизии. Положение города на Неве стало критическим.

И хотя противнику не удалось взять Ленинград с ходу, город оказался отрезанным от Большой земли. Началась блокада. Снабжение могло осуществляться отныне только по воздуху или Ладожскому озеру. Немцы вошли практически в пригороды Ленинграда и могли рассматривать в бинокли Исаакиевский собор.

Организация обороны

Уже 1 июля 1941 года в Ленинграде была создана Комиссия по обороне, которую возглавил партийный деятель А. А. Жданов. К моменту окружения города эвакуация населения проводилась недостаточными темпами. Около двух с половиной миллионов горожан, к числу которых надо прибавить беженцев из Прибалтики, Ленинградской области, бойцов Ленинградского фронта, оказались в блокаде. Ежедневно враг обстреливал город из артиллерийских орудий, в результате бомбёжек сгорели продовольственные склады, в том числе крупнейшие — Бадаевские.

И. В. Сталин в срочном порядке назначил командующим Ленинградским фронтом генерала Г. К. Жукова, который жёсткими мерами укрепил оборону на ближних подступах к городу и предпринял ряд контрударов. В результате уже в конце сентября командующий группы армий «Север» докладывал, что своими силами немецким войскам Ленинград не взять. Однако и командованию Ленинградским фронтом прорвать блокаду не удалось.

Голод

До войны Ленинград в основном снабжался поставками продовольствия из других регионов страны. Уже в начале сентября 1941 года были понижены нормы выдачи хлеба рабочим и инженерам, служащим, иждивенцам (по 600, 400 и 300 граммов соответственно).

В середине сентября эту норму вновь уменьшили. Самую низкую норму выдачи хлеба по карточкам ввели 20 ноября 1941 года, когда рабочие стали получать всего 250, а служащие, иждивенцы и дети — 125 граммов хлеба в день.

«Сто двадцать пять блокадных грамм

С огнём и кровью пополам».

О. Берггольц

Голод стал соратником врага. Люди умирали на работе, в своих квартирах, падали на улицах от изнеможения и больше не поднимались. За годы блокады, по послевоенным подсчётам, в Ленинграде погибло от 800 тысысяч до более миллиона человек (прежде всего от голода). Это больше, чем все военные потери Великобритании и США за Вторую мировую войну вместе взятые. Вина за гибель ленинградцев целиком и полностью лежит на гитлеровском командовании и руководстве Финляндии, чья армия блокировала город со стороны Карельского перешейка.

Мама 13 мая в 7:30 утра… Умерли все. Осталась одна Таня».

Таня Савичева, ленинградская школьница.

Из блокадного дневника / РИА Новости

Борьба

В мировой истории трудно отыскать случай, когда столь большой мегаполис оказывался вместе с жителями во вражеском кольце. Но Ленинград жил, Ленинград боролся. На оставшихся в городе предприятиях трудились ленинградцы (мужчины, женщины, подростки), которые ремонтировали военную технику, выпускали оружие, восстанавливали производство электроэнергии. Руководство города и командование фронтом делало всё возможное, чтобы прорвать блокаду. Символом несгибаемого мужества защитников Ленинграда стал «Невский пятачок».

«Вы, живые, знайте, что с этой земли мы уйти не хотели и не ушли.

Мы стояли насмерть у тёмной Невы. Мы погибли, чтоб жили вы».

Надпись на памятнике «Рубежный камень» на «Невском пятачке»

Попытки прорыва блокады предпринимались в сентябре и октябре 1941 года, начиная с января 1942 года в период общего наступления Красной Армии, а затем в августе – октябре 1942 года в ходе Синявинской операции Ленинградского и Волховского фронтов. В ходе последней были обескровлены вражеские силы, которые перебросили специально под Ленинград, чтобы взять его штурмом. Командование Ленинградским фронтом вело успешную противобатарейную войну с немецкой тяжёлой артиллерией — количество снарядов, упавших на город, сократилось в несколько раз.

В Ленинграде, начиная с трагической зимы 1941–1942 годов, были организованы специальные стационары и столовые, где кормили людей. Руководству города удалось не только спасти население от варварских обстрелов и бомбёжек, но и предотвратить эпидемии, которые могли возникнуть в период блокады.

Дорога жизни

Единственной надеждой на спасение для сотен тысяч ленинградцев стала эвакуация и доставка продовольствия по Ладожскому озеру — летом по воде, зимой по льду. Эта трасса получила название «Дорога жизни». Доставка людей и грузов в период блокады по этой трассе по праву может сравниться с величайшими операциями Великой Отечественной войны. Как только в конце ноября 1941 года Ладога покрылась льдом, руководство Ленинграда организовало через озеро переброску продовольствия в город на грузовых машинах. Обратно эвакуировалось голодающее население. По «Дороге жизни» до весны 1943 года было доставлено 1,6 млн тонн грузов, эвакуировано 1,3 млн ленинградцев. Порой грузовики проваливались под лёд, но колонна продолжала движение, иногда под обстрелом. По дну Ладожского озера были уложены трубопровод и электрический кабель.

Я. Бродский / РИА Новости

В начале 1942 года нормы выдачи хлеба населению стали постепенно повышаться, но многие люди продолжали умирать от последствий голода — прежде всего от дистрофии. В декабре 1941 года умерли 53 тыс. человек, в январе 1942 года — более 100 тыс. человек.

Операция «Искра»

Прорыв блокады произошёл только в январе 1943 года в ходе операции «Искра» Ленинградского (командующий генерал‑полковник Л. А. Говоров) и Волховского (командующий генерал армии К. А. Мерецков) фронтов. Общую координацию наступления осуществлял Г. К. Жуков. Советские ударные группировки превосходили теперь врага на решающих направлениях в пять и более раз.

Блокаду прорвали 18 января 1943 года на узком участке южнее Ладоги, шириной всего 8—11 км. По этому коридору уже через несколько недель проложили железную дорогу, по которой доставляли в Ленинград продовольствие, вооружение, пополнение для защитников города.

во время операции по прорыву блокады Ленинграда.

Г. Чертов / РИА Новости

Конец блокады

Блокада Ленинграда продолжалась долгие 872 дня и была полностью снята только 27 января 1944 года в ходе Ленинградско‑Новгородской операции. В честь этого события впервые за всю войну был дан салют не в Москве, а в самом Ленинграде. Тысячи жителей вышли на улицы, чтобы увидеть салют и порадоваться столь желанной победе у стен своего родного города. 27 января стало Днём воинской славы России.

«Рыдают люди, и поют,

и лиц заплаканных не прячут.

Сегодня в городе —

САЛЮТ!

Сегодня ленинградцы

плачут…»

Ю. Воронов

Битва за Ленинград стала самой продолжительной в годы Великой Отечественной войны. Она длилась с 10 июля 1941 года по 9 августа 1944 года, когда финские части были отброшены от города к финской границе в ходе Выборгско‑Петрозаводской операции 1944 года.

8 мая 1965 года Ленинграду присвоено звание «Город‑герой».

Итоги обороны Ленинграда

Если враг взял город, все его жители были бы обречены на гибель, а немцы смогли бы перебросить значительные силы под Москву и Сталинград. В пригородах Ленинграда гитлеровцы и их пособники‑коллаборационисты из эсэсовских прибалтийских подразделений расстреливали и вешали ни в чём не повинных женщин, детей, стариков. Великолепные архитектурные ансамбли пригородов Ленинграда — Гатчины, Царского Села, Петергофа — были разграблены и уничтожены оккупантами.

Однако ленинградцы показали всему миру, на что они способны, защищая родной город. Сегодня в эти подвиги даже трудно поверить. Так сотрудники Всесоюзного института растениеводства голодали вместе со всеми ленинградцами, но из богатейшей и уникальной коллекции зерна они за время блокады не взяли ни одного зернышка. От голода на рабочем месте умер ленинградец Д. И. Кютинен. Он работал пекарем.

Великий композитор Д. Д. Шостакович начал писать свою знаменитую Седьмую «Ленинградскую» симфонию, находясь в блокадном городе и действуя в составе противопожарной команды во время налётов вражеской авиации. Впервые симфония прозвучала в марте 1942 года в Куйбышеве, а 9 августа 1942 года — в самом Ленинграде. В разгар блокады в Ленинграде прошла серия футбольных матчей. Немцы не могли поверить, что в мёртвом, как они считали, городе играют в футбол…

Ленинград выстоял и одержал великую победу над врагом — и военную, и моральную.

Б. Кудояров / ТАСС

На чтение 5 мин. Просмотров 19.6k. Опубликовано 29.03.2021

Блокадой Ленинграда называется военная осада города немецкими и финскими войсками, при участии испанской добровольческой дивизии, в 1941-1944 гг. Не сумев захватить Северную столицу СССР, агрессоры окружили её, отрезали от нормального снабжения и подвергли жестокой «войне на истощение».

Сколько длилась блокада Ленинграда? Без малого, девятьсот дней: с 8 сентября 1941 по 27 января 1944 г. В январе 1943-го советским войскам удалось частично освободить город от блокады, обеспечив ему связь с «Большой землёй» по узкому «коридору» шириною в 10 км, по южным берегам Ладоги. Но полностью эта проблема была решена только в конце января 1944 г.

Содержание:

- Начало блокады Ленинграда

- Ленинградская блокада – особенности

- Блокада Ленинграда – дата частичного снятия осады

- Блокада Ленинграда длилась 900 дней и была окончательно снята 27 января 1944 года

- Причины блокады Ленинграда и её последствия

Начало блокады Ленинграда

Захвату Ленинграда нацистское руководство придавало огромное стратегическое и политическое значение. Для решения этой задачи были выделены солидные силы – группа армий «Север», в авангарде которой шла мощная танковая группа. Наступление на Ленинград началось 10.07.1941 и, несмотря на ожесточённое сопротивление Красной Армии и серьёзные потери, развивалось оно успешно. Финские войска, наступавшие на Карельском перешейке, заблокировали город на Неве с севера.

В августе 41-го тяжёлые бои развернулись уже на самых подступах к городу. В конце августа вермахтом были перерезаны все железнодорожные ветки, что связывали Ленинград с остальной страной. 8 сентября гитлеровцы взяли Шлиссельбург и уже полностью отрезали город от «Большой земли» с суши.

Сообщение стало возможно поддерживать только по воздуху и через Ладожское озеро. На льду Ладоги зимой была проложена «Дорога жизни», по которой шло снабжение осаждённого города. Но её было, разумеется, недостаточно, и в Ленинграде свирепствовал голод.

Ленинградская блокада – особенности

Потеряв надежду захватить Ленинград, подавив оборону Красной Армии, немцы решили взять город на Неве измором. Они перешли к позиционной войне, построив мощные укрепрайоны, и стянули к Ленинграду огромное количество тяжёлой дальнобойной артиллерии.

Регулярные артобстрелы и авианалёты имели цели нарушить работу промышленных предприятий, которые продолжали функционировать даже в условиях блокады и деморализовать население непокорённого города. В часы окончания рабочего дня артиллерийский обстрел становился более интенсивным.

В перспективе планировалось город разрушить полностью. Для этого под Ленинград была свезена почти вся имевшаяся в распоряжении немцев тяжёлая дальнобойная артиллерия. В том числе и из оккупированных ими стран Европы.

Из-за проблем с продовольствием, уже с сентября 41-го нормы питания регулярно снижались как для военных, так и для гражданского населения. Своего минимума они достигли в ноябре – декабре 1941 года, после чего ситуация с нормами питания стала постепенно улучшаться.

Всё равно, паёк блокадников был мизерным. Люди голодали, и их страдания значительно усилились холодной зимой. Многие мирные жители попросту не пережили суровой зимы, умерев от истощения и лютого мороза. Централизованное отопление в городе было нарушено полностью. Чтобы согреться, в печках-буржуйках жгли всё, что только может гореть. Деревянные дома и заборы быстро разбирались на дрова.

Ситуация со снабжением начала постепенно меняться к лучшему весной 1942 года. Летом 42-го по дну Ладоги в Ленинград протянули трубопровод для снабжения города нефтепродуктами, а осенью – энергетический электрокабель.

Блокада Ленинграда – дата частичного снятия осады

Советские войска не раз предпринимали масштабные и настойчивые попытки снятия блокады Ленинграда, переходя в контрнаступление. Четыре крупных наступательных операции, организованных в 1941-1942 гг., проходили с ожесточёнными и кровопролитными боями, но так и не смогли прорвать кольцо вокруг города.

Блокада Ленинграда частично была снята благодаря наступлению в январе 1943 года. Красная Армия смогла вытеснить оккупантов с узкой полоски земли (шириной в 8-11 км) южнее Ладожского озера. По ней срочно, менее чем за три недели, протянули новую железнодорожную ветку и автодорогу параллельно ей – для бесперебойного снабжения города. Жителям города на Неве стало дышаться легче. Дата частичного снятия блокады Ленинграда – 18.01.1943.

Блокада Ленинграда длилась 900 дней и была окончательно снята 27 января 1944 года

Полностью блокаду Ленинграда советские войска сумели снять лишь в январе 1944 года, Ленинградско‑Новгородской операцией. Этим мощным наступлением они прорвали глубоко эшелонированную оборону гитлеровцев, и фронт оккупантов «посыпался». Гитлеровские войска были отброшены от Ленинграда на 60‑100 км.

Германская группа армий «Север» потерпела серьёзное поражение. Практически вся Ленинградская область и часть Калининской были очищены от оккупантов. Летом Красная Армия отбросила далеко от Ленинграда и финские войска.

Так была уже окончательно снята блокада Ленинграда. Сколько дней длилась она? 872 дня, если быть точным. Фактически же она началась ещё двумя неделями раньше: ведь уже 27 августа 1941 г. движение поездов из осаждённого города было остановлено.

Причины блокады Ленинграда и её последствия

Причинами установления блокады Ленинграда стали захватнические планы гитлеровской Германии. Не сумев взять город, руководство Третьего Рейха решило разрушить его блокадой, постоянными обстрелами и бомбёжками – уничтожить вместе с гражданским населением. Эти действия нацистской Германии во всех странах признаны чудовищным военным преступлением. Его жертвами стали, по разным оценкам, от 600 тыс. до 1 млн мирных жителей.

Для обеспечения блокады Ленинграда было стянуто огромное количество немецких войск. Однако, несмотря на все усилия, город остался непобеждённым и не был стёрт с лица Земли, как планировали нацисты.

Блокада Ленинграда стала беспримерным примером стойкости, мужества, самопожертвования. В канун 20-летия Победы Северная столица СССР получила почётное звание «Города-героя». День полного снятия блокады Ленинграда с 1995 года входит в список Дней воинской славы России.

«Siege of Petrograd» redirects here. Not to be confused with Battle of Petrograd.

| Siege of Leningrad | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | ||||||||

Soviet antiaircraft battery in Leningrad near Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, 1941 |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Naval support: |

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| Initial: 725,000 | Initial: 930,000 | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

1941: 85,371 total casualties[4] 1942: 267,327 total casualties[5] 1943: 205,937 total casualties[6] 1944: 21,350 total casualties[7] Total: 579,985 casualties |

Russian estimate of killed, captured or missing:[9] |

|||||||

|

Soviet civilians: 642,000 during the siege, 400,000 at evacuations[8] |

The Siege of Leningrad (Russian: Блокада Ленинграда, romanized: Blokada Leningrada; German: Leningrader Blockade; Finnish: Leningradin piiritys) was a prolonged military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the Soviet city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) on the Eastern Front of World War II. Germany’s Army Group North advanced from the south, while the German-allied Finnish army invaded from the north and completed the ring around the city.

The siege began on 8 September 1941, when the Wehrmacht severed the last road to the city. Although Soviet forces managed to open a narrow land corridor to the city on 18 January 1943, the Red Army did not lift the siege until 27 January 1944, 872 days after it began. The blockade became one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history, and it was possibly the costliest siege in history due to the number of casualties which were suffered throughout its duration. While not classed as a war crime at the time,[10]

in the 21st century, some historians have classified it as a genocide due to the systematic starvation and intentional destruction of the city’s civilian population.[11][12][13][14][15]

Background[edit]

German soldiers in front of burning houses and a church, near Leningrad in 1941

Leningrad’s capture was one of three strategic goals in the German Operation Barbarossa and the main target of Army Group North. The strategy was motivated by Leningrad’s political status as the former capital of Russia and the symbolic capital of the Russian Revolution and the hated Bolshevism, the city’s military importance as a main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet, and its industrial strength, housing numerous arms factories.[16] By 1939, the city was responsible for 11% of all Soviet industrial output.[17]

It has been reported that Adolf Hitler was so confident of capturing Leningrad that he had invitations printed to the victory celebrations to be held in the city’s Hotel Astoria.[18]

Although various theories have been put forward about Germany’s plans for Leningrad, including making it the capital of the new Ingermanland province of the Reich in Generalplan Ost, it is clear Hitler intended to utterly destroy the city and its population. According to a directive sent to Army Group North on 29 September:

After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban center. […] Following the city’s encirclement, requests for surrender negotiations shall be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, we can have no interest in maintaining even a part of this very large urban population.[19]

Hitler’s ultimate plan was to raze Leningrad and give areas north of the River Neva to the Finns.[20][21]

Preparations[edit]

German plans[edit]

Army Group North under Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb advanced to Leningrad, its primary objective. By early August, Army Group North was seriously over-extended, having advanced on a widening front and dispersed its forces on several axes of advance. Leeb estimated he needed 35 divisions for all of his tasks, while he only had 26.[22] The attack resumed on 10 August but immediately encountered strong opposition around Luga. Elsewhere, Leeb’s forces were able to take Kingisepp and Narva on 17 August. The army group reached Chudovo on 20 August, severing the rail link between Leningrad and Moscow. Tallinn fell on 28 August.[23]

Finnish military forces were north of Leningrad, while German forces occupied territories to the south.[24] Both German and Finnish forces had the goal of encircling Leningrad and maintaining the blockade perimeter, thus cutting off all communication with the city and preventing the defenders from receiving any supplies – although Finnish participation in the blockade mainly consisted of a recapture of lands lost in the Winter War. The Germans planned on lack of food being their chief weapon against the citizens; German scientists had calculated the city would reach starvation after only a few weeks.[1][2][25][26]

Leningrad fortified region[edit]

On Friday, 27 June 1941, the Council of Deputies of the Leningrad administration organised «First response groups» of civilians. In the next days, Leningrad’s civilian population was informed of the danger and over a million citizens were mobilised for the construction of fortifications. Several lines of defences were built along the city’s perimeter to repulse hostile forces approaching from north and south by means of civilian resistance.[2]

In the south, the fortified line ran from the mouth of the Luga River to Chudovo, Gatchina, Uritsk, Pulkovo and then through the Neva River. Another line of defence passed through Peterhof to Gatchina, Pulkovo, Kolpino and Koltushy. In the north the defensive line against the Finns, the Karelian Fortified Region, had been maintained in Leningrad’s northern suburbs since the 1930s, and was now returned to service. A total of 306 km (190 mi) of timber barricades, 635 km (395 mi) of wire entanglements, 700 km (430 mi) of anti-tank ditches, 5,000 earth-and-timber emplacements and reinforced concrete weapon emplacements and 25,000 km (16,000 mi)[27] of open trenches were constructed or excavated by civilians. Even the guns from the cruiser Aurora were removed from the ship to be used to defend Leningrad.[28]

Establishment[edit]

The 4th Panzer Group from East Prussia took Pskov following a swift advance and reached Novgorod by 16 August. After the capture of Novgorod, General Hoepner’s 4th Panzer Group continued its progress towards Leningrad.[29] However, the 18th Army – despite some 350,000 men lagging behind – forced its way to Ostrov and Pskov after the Soviet troops of the Northwestern Front retreated towards Leningrad. On 10 July, both Ostrov and Pskov were captured and the 18th Army reached Narva and Kingisepp, from where advance toward Leningrad continued from the Luga River line. This had the effect of creating siege positions from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, with the eventual aim of isolating Leningrad from all directions. The Finnish Army was then expected to advance along the eastern shore of Lake Ladoga.[30]

The last rail connection to Leningrad was cut on 30 August, when the German forces reached the River Neva. In early September, Leeb was confident Leningrad was about to fall. Having received reports on the evacuation of civilians and industrial goods, Leeb and the OKH believed the Red Army was preparing to abandon the city. Consequently, on 5 September, he received new orders, including the destruction of the Red Army forces around the city. By 15 September, Panzer Group 4 was to be transferred to Army Group Centre so it could participate in a renewed offensive towards Moscow. The expected surrender did not materialise although the renewed German offensive cut off the city by 8 September.[31] Lacking sufficient strength for major operations, Leeb had to accept the army group might not be able to take the city, although hard fighting continued along his front throughout October and November.[32]

Orders of battle[edit]

Germany[edit]

Map of Army Group North’s advance into the USSR in 1941. Coral up to 9 July, pink up to 1 September and green up to 5 December.

- Army Group North (Feldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb)[33]

- 18th Army (Georg von Küchler)

- XXXXII Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- XXVI Corps (3 infantry divisions)

- 16th Army (Ernst Busch)

- XXVIII Corps (Mauritz von Wiktorin) (2 infantry, 1 armoured divisions)

- I Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- X Corps (3 infantry divisions)

- II Corps (3 infantry divisions)

- (L Corps – Under 9th Army) (2 infantry divisions)

- 4th Panzer Group (Erich Hoepner)

- XXXVIII Corps (Friedrich-Wilhelm von Chappuis) (1 infantry division)

- XXXXI Motorized Corps (Georg-Hans Reinhardt) (1 infantry, 1 motorised, 1 armoured divisions)

- LVI Motorized Corps (Erich von Manstein) (1 infantry, 1 motorised, 1 armoured, 1 panzergrenadier divisions)

- 18th Army (Georg von Küchler)

Finland[edit]

- Finnish Defence Forces HQ (Finnish Marshal Mannerheim)[34]

- I Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- II Corps (2 infantry divisions)

- IV Corps (3 infantry divisions)

Italy[edit]

- XII Squadriglia MAS (Mezzi d’Assalto) (Italian for «12th Assault Vessel Squadron») (C.C. Giuseppe Bianchini) Regia Marina

Spain[edit]

- Blue Division, officially designated as 250. Infanterie-Division by the German Army and as the División Española de Voluntarios by the Spanish Army; General Esteban Infantes took command of this unit of Spanish volunteers at the Eastern Front during World War II.[35]

Soviet Union[edit]

- Northern Front (Lieutenant General Popov)[36]

- 7th Army (2 rifle, 1 militia divisions, 1 naval infantry brigade, 3 motorised rifle and 1 armoured regiments)

- 8th Army

- 10th Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions)

- 11th Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (3 rifle divisions)

- 14th Army

- 42nd Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (2 rifle divisions, 1 Fortified area, 1 motorised rifle regiment)

- 23rd Army

- 19th Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (2 rifle, 1 motorised divisions, 2 Fortified areas, 1 rifle regiment)

- Luga Operation Group

- 41st Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions)

- Separate Units (1 armoured brigade, 1 rifle regiment)

- Kingisepp Operation Group

- Separate Units (2 rifle, 2 militia, 1 armoured divisions, 1 Fortified area)

- Separate Units (3 rifle divisions, 4 guard militia divisions, 3 Fortified areas, 1 rifle brigade)

The 14th Army of the Soviet Red Army defended Murmansk and the 7th Army defended Ladoga Karelia; thus they did not participate in the initial stages of the siege. The 8th Army was initially part of the Northwestern Front and retreated through the Baltics. It was transferred to the Northern Front on 14 July when the Soviets evacuated Tallinn.

On 23 August, the Northern Front was divided into the Leningrad Front and the Karelian Front, as it became impossible for front headquarters to control everything between Murmansk and Leningrad.

Zhukov states, «Ten volunteer opolcheniye divisions were formed in Leningrad in the first three months of the war, as well as 16 separate artillery and machine-gun opolcheniye battalions.»[37]: 421, 438

Severing lines of communication[edit]

On 6 August, Hitler repeated his order: «Leningrad first, Donetsk Basin second, Moscow third.»[38] Arctic convoys using the Northern Sea Route delivered American Lend-Lease and British food and war materiel supplies to the Murmansk railhead (although the rail link to Leningrad was cut off by Finnish armies just north of the city), as well as several other locations in Lapland.[citation needed]

Encirclement of Leningrad[edit]

Map showing the Axis encirclement of Leningrad

Finnish intelligence had broken some of the Soviet military codes and read their low-level communications. This was particularly helpful for Hitler, who constantly requested intelligence information about Leningrad.[39] Finland’s role in Operation Barbarossa was laid out in Hitler’s Directive 21, «The mass of the Finnish army will have the task, in accordance with the advance made by the northern wing of the German armies, of tying up maximum Russian (sic – Soviet) strength by attacking to the west, or on both sides, of Lake Ladoga».[40] The last rail connection to Leningrad was severed on 30 August, when the Germans reached the Neva River. On 8 September, the road to the besieged city was severed when the Germans reached Lake Ladoga at Shlisselburg, leaving just a corridor of land between Lake Ladoga and Leningrad which remained unoccupied by Axis forces. Bombing on 8 September caused 178 fires.[41]

On 21 September, German High Command considered how to destroy Leningrad. Occupying the city was ruled out «because it would make us responsible for food supply».[42] The resolution was to lay the city under siege and bombardment, starving its population. «Early next year, we [will] enter the city (if the Finns do it first we do not object), lead those still alive into inner Russia or into captivity, wipe Leningrad from the face of the earth through demolitions, and hand the area north of the Neva to the Finns.»[43] On 7 October, Hitler sent a further directive signed by Alfred Jodl reminding Army Group North not to accept capitulation.[44]

Finnish participation[edit]

By August 1941, the Finns advanced to within 20 km (12 mi) of the northern suburbs of Leningrad at the 1939 Finnish-Soviet border, threatening the city from the north; they were also advancing through East Karelia, east of Lake Ladoga, and threatening the city from the east. The Finnish forces crossed the pre-Winter War border on the Karelian Isthmus by eliminating Soviet salients at Beloostrov and Kirjasalo, thus straightening the frontline so that it ran along the old border near the shores of Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, and those positions closest to Leningrad still lying on the pre-Winter War border.

According to Soviet claims, the Finnish advance was stopped in September through resistance by the Karelian Fortified Region;[45] however, Finnish troops had already earlier in August 1941 received orders to halt the advance after reaching their goals, some of which lay beyond the pre-Winter War border. After reaching their respective goals, the Finns halted their advance and started moving troops to East Karelia.[46][47]

For the next three years, the Finns did little to contribute to the battle for Leningrad, maintaining their lines.[48] Their headquarters rejected German pleas for aerial attacks against Leningrad[49] and did not advance farther south from the Svir River in occupied East Karelia (160 kilometres northeast of Leningrad), which they had reached on 7 September. In the southeast, the Germans captured Tikhvin on 8 November, but failed to complete their encirclement of Leningrad by advancing further north to join with the Finns at the Svir River. On 9 December, a counter-attack of the Volkhov Front forced the Wehrmacht to retreat from their Tikhvin positions in the Volkhov River line.[2]

On 6 September 1941, Germany’s Chief of Staff Alfred Jodl visited Helsinki. His main goal was to persuade Mannerheim to continue the offensive. In 1941, President Ryti declared to the Finnish Parliament that the aim of the war was to restore the territories lost during the Winter War and gain more territories in the east to create a «Greater Finland».[50][51][52] After the war, Ryti stated: «On August 24, 1941 I visited the headquarters of Marshal Mannerheim. The Germans aimed us at crossing the old border and continuing the offensive to Leningrad. I said that the capture of Leningrad was not our goal and that we should not take part in it. Mannerheim and Minister of Defense Walden agreed with me and refused the offers of the Germans. The result was a paradoxical situation: the Germans could not approach Leningrad from the north…» There was little or no systematic shelling or bombing from the Finnish positions.[24]

The proximity of the Finnish border – 33–35 km (21–22 mi) from downtown Leningrad – and the threat of a Finnish attack complicated the defence of the city. At one point, the defending Front Commander, Popov, could not release reserves opposing the Finnish forces to be deployed against the Wehrmacht because they were needed to bolster the 23rd Army’s defences on the Karelian Isthmus.[53] Mannerheim terminated the offensive on 31 August 1941, when the army had reached the 1939 border. Popov felt relieved, and redeployed two divisions to the German sector on 5 September.[54]

Subsequently, the Finnish forces reduced the salients of Beloostrov and Kirjasalo,[55] which had threatened their positions at the sea coast and south of the River Vuoksi.[55] Lieutenant General Paavo Talvela and Colonel Järvinen, the commander of the Finnish Coastal Brigade responsible for Ladoga, proposed to the German headquarters the blocking of Soviet convoys on Lake Ladoga. The idea was proposed to the Germans on their own behalf going past both Finnish Navy HQ and General HQ. Germans responded positively to the proposition and informed the slightly surprised Finns—who apart from Talvela and Järvinen had very little knowledge of the proposition—that transport of the equipment for the Ladoga operation was already arranged. The German command formed the ‘international’ naval detachment (which also included the Italian XII Squadriglia MAS) under Finnish command and the Einsatzstab Fähre Ost under German command. These naval units operated against the supply route in the summer and autumn of 1942, the only period the units were able to operate as freezing waters then forced the lightly equipped units to be moved away, and changes in front lines made it impractical to reestablish these units later in the war.[24][39][56][57]

Defensive operations[edit]

Two Soviet soldiers, one armed with a DP machine gun, in the trenches of the Leningrad Front on 1 September 1941

The Leningrad Front (initially the Leningrad Military District) was commanded by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov. It included the 23rd Army in the northern sector between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, and the 48th Army in the western sector between the Gulf of Finland and the Slutsk–Mga position. The Leningrad Fortified Region, the Leningrad garrison, the Baltic Fleet forces, and Koporye, Pulkovo, and Slutsk–Kolpino operational groups were also present.[citation needed]

Defence of civilian evacuees[edit]

According to Zhukov, «Before the war Leningrad had a population of 3,103,000 and 3,385,000 counting the suburbs. As many as 1,743,129, including 414,148 children were evacuated» between 29 June 1941 and 31 March 1943. They were moved to the Volga area, the Urals, Siberia and Kazakhstan.[37]: 439

By September 1941, the link with the Volkhov Front (commanded by Kirill Meretskov) was severed and the defensive sectors were held by four armies: 23rd Army in the northern sector, 42nd Army on the western sector, 55th Army on the southern sector, and the 67th Army on the eastern sector. The 8th Army of the Volkhov Front had the responsibility of maintaining the logistic route to the city in coordination with the Ladoga Flotilla. Air cover for the city was provided by the Leningrad military district PVO Corps and Baltic Fleet naval aviation units.[58][59]

The defensive operation to protect the 1,400,000 civilian evacuees was part of the Leningrad counter-siege operations under the command of Andrei Zhdanov, Kliment Voroshilov, and Aleksei Kuznetsov. Additional military operations were carried out in coordination with Baltic Fleet naval forces under the general command of Admiral Vladimir Tributs. The Ladoga Flotilla under the command of V. Baranovsky, S.V. Zemlyanichenko, P.A. Traynin, and B.V. Khoroshikhin also played a major military role in helping with evacuation of the civilians.[60]