-

Эта статья о персонаже мультфильма 1951 года. О персонаже фильма 2010 года см. Таррант Цилиндр.

Болванщик (англ. Mad Hatter) — персонаж диснеевского полнометражного мультфильма 1951 года «Алиса в Стране Чудес».

О персонаже

Характер

Поведение в мультфильме полностью соответствует оригиналу.

Описание внешности

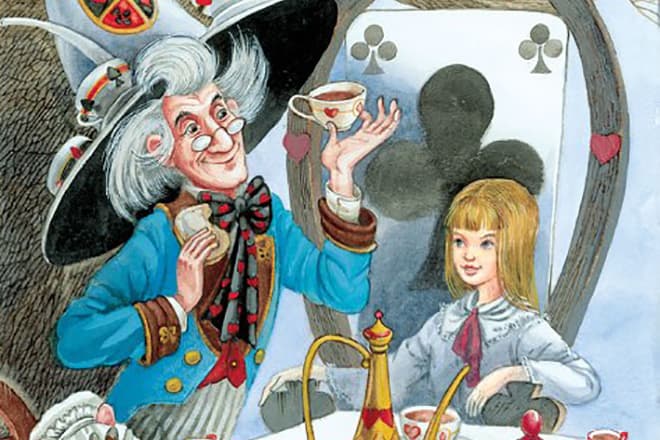

В мультфильме внешность Болванщика следующая — он выглядит как старичок (с пучками волос по бокам) в жёлтом костюме с синей бабочкой и зелёной шляпе с биркой.

Появления

Алиса в Стране Чудес

Алиса видит его и Зайца в саду. При этом они поют про неименины.

Чокнутый

Мышиный Дом

Как и все остальные персонажи мультфильма, он появлется среди гостей Микки.

Видеоигры

Disney Magic Kingdoms

Появлялся в игре во время акции «Алиса в Стране Чудес«.

Галерея

На Disney Wiki имеется коллекция изображений и медиафайлов, относящихся к статье Болванщик.

Прочее

- Часто Болванщика называют другом Алисы. Это видно в парках Диснея или рекламной продукции, но на самом деле они противоположны друг другу.

- Болванщик послужил визуальным вдохновением для Призрака из шляпной коробки, который, по предположениям некоторых фанатов, раньше был шляпником.

- Шляпу Болванщика можно увидеть в кабинетах Йен Сида на полке в Epic Mickey.

- Его шляпу так же можно использовать для Маленьких зелёных человечков в Toy Story 3: The Video Game.

»

| п — р — о

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

п — р — о |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| The (Mad) Hatter | |

|---|---|

| Alice character | |

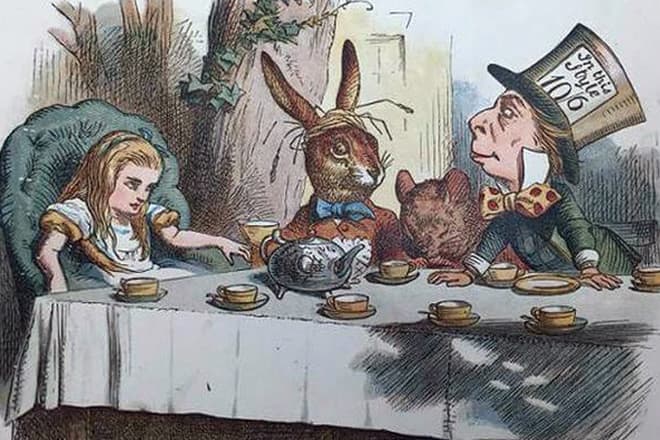

The Hatter as depicted by John Tenniel, reciting his nonsensical poem, «Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Bat» |

|

| First appearance | Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) |

| Last appearance | Through the Looking-Glass (1871) |

| Created by | Lewis Carroll |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Hatter Mad Hatter |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Messenger, hatter |

| Nationality | Wonderland, Looking-glass world |

| Other versions | Tarrant Hightopp |

The Hatter is a fictional character in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its 1871 sequel Through the Looking-Glass. He is very often referred to as the Mad Hatter, though this term was never used by Carroll. The phrase «mad as a hatter» pre-dates Carroll’s works. The Hatter and the March Hare are referred to as «both mad» by the Cheshire Cat, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in the sixth chapter titled «Pig and Pepper».

Fictional character biography[edit]

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland[edit]

The Hatter character, alongside all the other fictional beings, first appears in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In «Chapter Seven – A Mad Tea-Party», while exploring Wonderland, Alice comes across the Hatter having tea with the March Hare and the Dormouse. The Hatter explains to Alice that they are always having tea because when he tried to sing for the foul-tempered Queen of Hearts, she sentenced him to death for «murdering the time», but he escapes decapitation. In retaliation, Time (referred to as «he» by the Hatter) halts himself in respect to the Hatter, keeping him stuck at 6:00 pm (or 18:00) forever.

When Alice arrives at the tea party, the Hatter is characterised by switching places on the table at any given time, making short, personal remarks, asking unanswerable riddles, and reciting nonsensical poetry, all of which eventually drives Alice away. The Hatter appears again in «Chapter Eleven – Who Stole the Tarts?», as a witness at the Knave of Hearts’ trial, where the Queen appears to recognise him as the singer she sentenced to death, and the King of Hearts also cautions him not to be nervous or he will have him «executed on the spot».

Through the Looking-Glass[edit]

The character also appears briefly in Carroll’s 1871 Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Under the name of «Hatta,» the Hatter was in trouble with the law once again. He was, however, not necessarily guilty, as the White Queen explained that subjects were often punished before they commit a crime, rather than after, and sometimes they did not even commit one at all. He was also mentioned as one of the White King’s messengers along with March Hare, who went under the name of «Haigha.» Sir John Tenniel’s illustration depicts Hatta as sipping from a teacup as he did in the original novel. Alice does not comment on whether Hatta is the Hatter of her earlier dream.

Characterization[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Mercury was used in the manufacturing of felt hats during the 19th century, causing a high rate of mercury poisoning among those working in the hat industry.[1] Mercury poisoning causes neurological damage, including slurred speech, memory loss, and tremors, which led to the phrase «mad as a hatter».[1] In the Victorian age, many workers in the textile industry, including hatters, sometimes developed illnesses affecting the nervous system, such as central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis, which is portrayed in novels like Alton Locke by Charles Kingsley and North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell, which Lewis Carroll had read. Many such workers were sent to Pauper Lunatic Asylums, which were supervised by Lunacy Commissioners such as Samuel Gaskell and Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, Carroll’s uncle. Carroll was familiar with the conditions at asylums and visited at least one, the Surrey County Asylum, himself, which treated patients with so-called non-restraint methods and occupied them, amongst others, in gardening, farming and hat-making.[2] Besides staging theatre plays, dances and other amusements, such asylums also held tea-parties.[3]

Appearance[edit]

Although, during the trial of the Knave of Hearts, the King of Hearts remarks upon the Hatter’s headgear, Carroll does not describe the exact style of hat he wears. The character’s signature top hat comes from John Tenniel’s illustrations for the first edition, in which the character wears a large top hat with a hatband reading «In this style 10/6». This is further elaborated on in The Nursery «Alice», a shortened version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, adapted by the author himself for young children. Here it is stated that the character is wearing a hat on his head with a price tag containing the numbers 10 and 6, giving the price in pre-decimal British money as ten shillings and six pence (or half a guinea).[4]

Personality[edit]

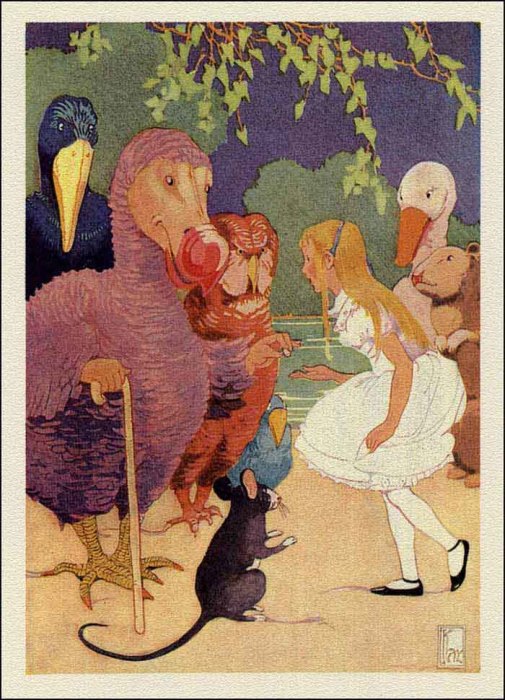

Illustration of the March Hare, one of the Hatter’s tea party friends, by Sir John Tenniel.

The Hatter and his tea party friend, the March Hare, are initially referred to as «both mad» by the distinctive Cheshire Cat. The first mention of both characters occurs in the sixth chapter of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, titled «Pig and Pepper», in a conversation between the child protagonist Alice and the Cheshire Cat, when she asks «what sort of people live about here?» to which the cat replies «in that direction lives a Hatter, and in that direction, lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad!» Both then subsequently make their actual debuts in the seventh chapter of the same book, which is titled «A Mad Tea-Party».

Hat making was the main trade in Stockport where Carroll grew up, and it was not unusual then for hatters to appear disturbed or confused; many died early as a result of mercury poisoning. However, the Hatter does not exhibit the symptoms of mercury poisoning, which include excessive timidity, diffidence, increasing shyness, loss of self-confidence, anxiety, and a desire to remain unobserved and unobtrusive.[5]

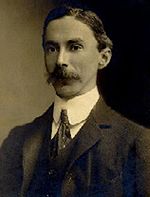

Resemblance to Theophilus Carter[edit]

It has often been claimed that the Hatter’s character may have been inspired by Theophilus Carter, an eccentric furniture dealer.[6][7] Carter was supposedly at one time a servitor at Christ Church, one of the University of Oxford’s colleges.[8] This is not substantiated by university records.[8] He later owned a furniture shop, and became known as the «Mad Hatter» from his habit of standing in the door of his shop wearing a top hat.[6][7] Sir John Tenniel is reported to have come to Oxford especially to sketch him for his illustrations.[6] There is no evidence for this claim, however, in either Carroll’s letters or diaries.[9]

Riddle[edit]

In the chapter «A Mad Tea Party», the Hatter asks a much-noted riddle: «Why is a raven like a writing desk?» When Alice gives up trying to figure out why, the Hatter admits «I haven’t the slightest idea!». Carroll originally intended the riddle to be without an answer, but after many requests from readers, he and others—including puzzle expert Sam Loyd—suggested possible answers; in his preface to the 1896 edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Carroll wrote:

Inquiries have been so often addressed to me, as to whether any answer to the Hatter’s riddle can be imagined, that I may as well put on record here what seems to me to be a fairly appropriate answer, «because it can produce a few notes, though they are very flat; and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front!» This, however, is merely an afterthought; the riddle as originally invented had no answer at all.[10][a]

Loyd proposed a number of alternative solutions to the riddle, including «because Poe wrote on both» (alluding to Poe’s 1845 narrative poem The Raven) and «because the notes for which they are noted are not noted for being musical notes». The April 2017 edition of Bandersnatch, the Newsletter of the Lewis Carroll Society [Issue 172, ISSN 0306-8404, Apr 2017], published the following solution, proposed by puzzle expert Rick Hosburn: «Why is a Raven like a Writing-desk?» «Because one is a crow with a bill, while the other is a bureau with a quill!» The RSPB, in its definition of Raven, states: «The raven […] is all black with a large bill, and long wings.» American author Stephen King provides an alternative answer to the Hatter’s riddle in his 1977 horror novel The Shining. Snowbound and isolated «ten thousand feet high» in the Rocky Mountains, five-year-old Danny hears whispers of the malign «voice of the [Overlook] hotel» inside his head, including this bit of mockery: «Why is a raven like a writing desk? The higher the fewer, of course! Have another cup of tea!»

In popular culture[edit]

The Hatter has been featured in nearly every adaptation of Alice in Wonderland to date; he is usually the male lead despite being a supporting character. The character has been portrayed in film by Norman Whitten, Edward Everett Horton, Sir Robert Helpmann, Martin Short, Peter Cook, Anthony Newley, Ed Wynn, Andrew-Lee Potts, and Johnny Depp. In music videos, the Hatter has been portrayed by Tom Petty, Dero Goi, and Steven Tyler. He has also been portrayed on stage by Nikki Snelson and Katherine Shindle, and on television by John Robert Hoffman, Pip Donaghy and Sebastian Stan. In ballet adaptations, Steven McRae also portrayed him as a mad ‘Tapper’.[11] In March 2019, Chelsy Meiss became the first female soloist to play the Mad Hatter for the National Ballet of Canada.[12]

Films[edit]

- In the 1951 Walt Disney animated feature Alice in Wonderland, the Hatter appears as a short, hyperactive man with grey hair, a large nose and a comical voice. He was voiced by Ed Wynn in 1951, and by Corey Burton in his later appearances (Bonkers, House of Mouse). Alice stumbles upon the Hatter and the March Hare having an «un-birthday» party for themselves. The Hatter asks her the infamous riddle «why is a raven like a writing desk?», but when she tries to answer the Hatter and the March Hare think she is «stark raving mad» and the Hatter completely forgot that he even asked her the riddle. Throughout the course of the film, the Hatter pulls numerous items out of his hat, such as cake and smaller hats. His personality is that of a child; angry one second, happy the next.

- The Hatter appears in Tim Burton’s 2010 version of Alice in Wonderland portrayed by Johnny Depp and given the name Tarrant Hightopp.[13] In the film, the Hatter takes Alice toward the White Queen’s castle and relates the terror of the Red Queen’s reign while commenting that Alice is not the same as she once was. The Hatter subsequently helps Alice avoid capture by the Red Queen’s guards by allowing himself to be seized instead. He is later saved from execution by the Cheshire Cat and calls for rebellion against the Red Queen. Near the end of the film, the Hatter unsuccessfully suggests to Alice that she could stay in Wonderland and consummate his feelings for her.Critical reception to Johnny Depp’s portrayal of the Hatter was generally positive. David Edelstein of New York Magazine remarked that while the elements of the character suggested by Depp don’t entirely come together, «Depp brings an infectious summer-stock zest to everything he does.»[14] Bill Goodykoontz of The Arizona Republic said that «Depp is exactly what you’d expect, which is a good thing. Gap-toothed and leering, at times he looks like Madonna after sticking a fork in a toaster. How he finds his characters is anybody’s guess, a sort of thrift-store warehouse of eccentricities, it seems like. But it works.»[15] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly had a more mixed opinion and commented that Depp as the Hatter is «a fantastic image, but once Depp opens his mouth, what comes out is a noisome Scottish brogue that makes everything he says sound more or less the same. The character offers no captivatingly skewed bat-house psychology. There isn’t much to him, really—he’s just a smiling Johnny one-note with a secret hip-hop dance move—and so we start to react to him the way that Alice does to everything else: by wondering when he’s going to stop making nonsense.»[16] Kenneth Turan of Los Angeles Times stated that «there’s no denying Depp’s gifts and abilities, but this performance feels both indulgent and something we’ve all seen before.»[17]

- The Hatter is played by Clarke Peters in the 2020 movie Come Away. He is depicted as the father of Captain Hook, the grandfather of Alice and Peter Pan, and the great-grandfather of Wendy Darling, John Darling, and Michael Darling.

Television[edit]

- The Hatter was also a semi-regular on the Disney Afternoon series Bonkers and one of the guests in House of Mouse, where he even made a cameo appearance in one of the featured cartoon shorts.

- The TV series Futurama has a robot named Mad Hatterbot who is based on the Hatter. Seen only in the HAL Institute (an asylum for criminally insane robots) the Mad Hatterbot only says one line: «Change places!», which all in the room comply with when spoken. The price tag on his hat reads «5/3», exactly half of 10/6. A minor character, he has been in the episodes «Insane in the Mainframe» and «Follow the Reader» as well as the film Futurama: Bender’s Game.

- In Syfy’s Alice, the Hatter (Andrew-Lee Potts) is portrayed as a smuggler who starts off working as a double agent for the Queen of Hearts and the Wonderland Resistance in the story; over the course of the story, he begins to side more and more with the Resistance, and ends up falling in love with Alice as he helps her along the way.

- In Once Upon a Time, the Mad Hatter is presented as possessing the unique ability to cross dimensions through his hat, and has a daughter, Grace, who lost her mother Priscilla[18] as a result of a past deal with the Evil Queen. When the Queen offers him enough wealth to set his daughter up for life, he agrees to help her travel to Wonderland, but when it is revealed that the goal was for the Queen to retrieve her captured father, the Hatter is left trapped in Wonderland instead, as the portal will only allow two people to pass through it in either direction. Trapped in Wonderland, he was then driven mad as he attempted to find another way back to his world to reunite with his daughter. In the first season, trapped in the Land Without Magic, the Mad Hatter- now known as ‘Jefferson’ as he lives in a mansion just on the outskirts of Storeybrooke- is one of the few who remembers his original life due to his insanity. His daughter has also been brought into Storeybrooke, but he has avoided making contact with her due to her new memories meaning that she would not recognise him. Unable to harness magic in this world, he attempts to recruit Emma to make a hat for him, but she is unable to harness her power, although Jefferson’s knowledge of the curse gives Emma further proof that Henry is telling the truth. Regina later recruits Jefferson to help her create a curse to use on Emma, but Regina’s efforts backfire and give Emma clear proof that the curse is real. In the second season, with the curse broken, Jefferson is eventually convinced to reunite with his daughter.

- In the Netflix’s Ever After High episode «Spring Unsprung», the Mad Hatter makes an appearance as Madeline Hatter’s father. In the 47-minute special, he runs the Mad Hatter’s Tea Shoppe in the town of Bookend, not far from Maddie’s school Ever After High. He also runs a shop by the same name in Wonderland, but it was abandoned after the Evil Queen (Raven Queen’s mother) cast a curse upon the land.

Video games[edit]

- In the 2000 video game American McGee’s Alice, The Mad Hatter is portrayed as psychotic, literally gone «mad» and obsessed with time and clockworks, and considers himself to be a genius. He invents mechanical devices, often evidently using the bodies of living organisms for the base of his inventions, as he plans to do to all of Wonderland’s inhabitants. He appears in the 2011 sequel Alice: Madness Returns in the same appearance, although this time, he requests Alice’s help in retrieving his lost limbs from his former compatriots the March Hare and Dormouse. The Hatter’s fixation on time might be based on the unseen character Time, which might explain why he replaced his body with cogs and gears as he sees Time as some type of god.

- The Hatter makes a cameo appearance in a painting in the Tea Party Garden in the 2002 video game Kingdom Hearts.

- The Mad Hatter appeared in the Sunsoft’s 2006 mobile game Alice’s Warped Wonderland (歪みの国のアリス, Yugami no kuni no Arisu, Alice in Distortion World). The Mad Hatter is portrayed as a middle-school age boy in oversized clothes and a large hat that covers his whole head. Unlike most Wonderland residents, he acts rather bratty and rude to Ariko (the «Alice» of the game). In one of the bad endings, Mad Hatter is killed by a twisted Cheshire Cat.[19][20]

- In Get Even, one of the asylum patients wearing the Pandora headsets dresses as the Hatter and has a tea party in his cell, he gives Cole Black a riddle to get the door open, there is a choice option to leave him in his room or set him free to which he’ll join the other inmates to kill Black, who they all believe is the «Puppet Master».

Music[edit]

- The song «Mad Hatter» by an American garage rock band Shag was inspired by the character. It appeared on their self-titled album in 1969.

- Sir John Tenniel’s drawing of the Hatter, combined with a montage of other images from Alice in Wonderland, were used as a logo by Charisma Records from 1972 onwards.

- A Burton’s inspired Mad Hatter appears in «The Man who became a Rabbit» music video, an Indian version of Alice in Wonderland by Valérian MacRabbit and Lalkrishnan. Mad Hatter becomes Mac Hatter and gives one riddle to the main character : «Spread blood on the birthday cake».[21]

- The Mad Hatter’s name is used in Elton John’s 1972 song Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters.

- The Mad Hatter is referenced to in the eponymous 2015 song by Melanie Martinez, next to a few other characters from Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.[2]

Live performance[edit]

- The Hatter is a greetable character at the Disneyland Resort, Walt Disney World Resort, Tokyo Disney Resort, Disneyland Paris Resort and Hong Kong Disneyland.

- Shrek The Musical, the Mad Hatter plays a small role as a fairytale creature (replacing the Gnome) and has two lines in songs including «They ridiculed my hat» and «I smell like sauerkraut».

- Frank Wildhorn composed the music to and co-wrote the music to Wonderland: A New Alice. In this adaption the Hatter is portrayed as a female, the villain of the story, and Alice’s alter-ego and is a mad woman who longs to be Queen. She was played by Nikki Snelson in the original Tampa, Florida production, and then by Kate Shindle in the Tampa/Houston Tour, and the production on Broadway.

Comic strips and books[edit]

- The Mad Hatter (also referred to as «Jervis Tetch») is a supervillain and enemy of the Batman in DC comic books, making his first appearance in the October 1948 (#49) release of Batman.[22] He is portrayed as a brilliant neurotechnician with considerable knowledge in how to dominate and control the human mind.[23] Jervis had a obsession over Lewis Carroll’s books that he believes himself to be the reincarnation of the Mad Hatter, including making his henchmen wear outfits based on the Wonderland characters and kidnapping women and force them to dress and named them Alice.

- A spin-off of the traditional Alice in Wonderland story, Frank Beddor’s The Looking Glass Wars features a character named Hatter Madigan, a member of an elite group of bodyguards known in Wonderland as the «Millinery» after the business of selling women’s hats. He acts as the bodyguard of the rightful Queen, and as guide/guardian to the protagonist, Alyss Heart.

- The Mad Hatter in Pandora Hearts manga series is a chain (creature from the Abyss) that was contracted by Xerxes Break. The hatter basically looks like a large top hat with flowery decorations (similar to Break’s top hat) and a tattered cape. When summoned, it can destroy all chains and objects from the Abyss within a large area.

- The Japanese manga Alice in the Country of Hearts has been translated into English. The Hatter role is played by Blood Dupre, a crime boss and leader of a street gang called The Hatters, which controls one of the four territories of Wonderland.

Toys[edit]

- The Hatter has a daughter named Madeline in Ever After High toy line.

See also[edit]

- March Hare

- Dormouse

Notes[edit]

- ^ Here, Caroll deliberately spelled the word «never» as «nevar», which is «raven» backward.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Myers 2003, p. 276.

- ^ a b Kohlt, Franziska (26 April 2016). «‘The Stupidest Tea-Party in All My Life’: Lewis Carroll and Victorian Psychiatric Practice». Journal of Victorian Culture. 22 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1080/13555502.2016.1167767.

- ^ Tuke, Samuel (1813). Description of the Retreat, an institution near York, for insane persons of the Society of Friends : containing an account of its origin and progress, the modes of treatment, and a statement of cases. York: Philadelphia : Published by Isaac Peirce … p. 111.

- ^ Lewis, Carroll. The Nursery ‘Alice’. Macmillan. p. 40. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Waldron, H. A. (24 December 1983). «Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning?». British Medical Journal. 287 (6409): 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1961. PMC 1550196. PMID 6418283.

- ^ a b c Hancher 1985, p. 101.

- ^ a b Millikan, Lauren (5 March 2011). «The Mad Hatter». Carleton University. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ a b Collingwood 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Maters, Kristin (27 January 2014). «Who Really Inspired Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ Characters?». Books Tell You Why. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ «The Mad Hatter’s riddle: why is a raven like a writing desk?». Alice in Wonderland Net. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: «Becoming The Mad Hatter: Steven McRae on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (The Royal Ballet)» (video). YouTube. 26 October 2017.

- ^ «The first woman to play the Mad Hatter!» (video). 7 March 2019.

- ^ «Alice in Wonderland – Glossary of Terms/Script (early draft)» (PDF). Walt Disney Pictures. JoBlo.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ David Edelstein (28 February 2010). «David Edelstein on ‘Alice in Wonderland’, ‘The Yellow Handkerchief’, and ‘The Art of the Steal’ — New York Magazine Movie Review». New York Magazine. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Bill Goodykoontz (3 March 2010). «Alice in Wonderland». The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman (3 March 2010). «Alice in Wonderland Review». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Kenneth Turan (4 March 2010). «Review: ‘Alice in Wonderland’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Her name is revealed in Once Upon a Time: Out of the Past («Tea Party in March»).

- ^ «Alice’s Warped Wonderland«. Sunsoft. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ «Alice’s Warped Wonderland ~Encore~». Sunsoft. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ «The Man who became a Rabbit», Lalkrishnan / Valérian MacRabbit, The Freak Parade (2018)

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane and Lew Sayre Schwartz (p), Charles Paris (i). «The Scoop of the Century» Batman 49 (1948), DC Comics

- ^ Fleisher, Michael L. (1976). The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, Volume 1: Batman. New York City: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-02-538700-6. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Collingwood, Stuart (2011). The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-1108033886.

- Hancher, Michael (1985). The Tenniel Illustrations to the «Alice» Books. Ohio State University. ISBN 978-0814204085.

- Myers, Richard (2003). The Basics of Chemistry. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313316647.

External links[edit]

- Alice in Wonderland — The Mad Hatter! on YouTube

| The (Mad) Hatter | |

|---|---|

| Alice character | |

The Hatter as depicted by John Tenniel, reciting his nonsensical poem, «Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Bat» |

|

| First appearance | Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) |

| Last appearance | Through the Looking-Glass (1871) |

| Created by | Lewis Carroll |

| In-universe information | |

| Alias | Hatter Mad Hatter |

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Messenger, hatter |

| Nationality | Wonderland, Looking-glass world |

| Other versions | Tarrant Hightopp |

The Hatter is a fictional character in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its 1871 sequel Through the Looking-Glass. He is very often referred to as the Mad Hatter, though this term was never used by Carroll. The phrase «mad as a hatter» pre-dates Carroll’s works. The Hatter and the March Hare are referred to as «both mad» by the Cheshire Cat, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in the sixth chapter titled «Pig and Pepper».

Fictional character biography[edit]

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland[edit]

The Hatter character, alongside all the other fictional beings, first appears in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. In «Chapter Seven – A Mad Tea-Party», while exploring Wonderland, Alice comes across the Hatter having tea with the March Hare and the Dormouse. The Hatter explains to Alice that they are always having tea because when he tried to sing for the foul-tempered Queen of Hearts, she sentenced him to death for «murdering the time», but he escapes decapitation. In retaliation, Time (referred to as «he» by the Hatter) halts himself in respect to the Hatter, keeping him stuck at 6:00 pm (or 18:00) forever.

When Alice arrives at the tea party, the Hatter is characterised by switching places on the table at any given time, making short, personal remarks, asking unanswerable riddles, and reciting nonsensical poetry, all of which eventually drives Alice away. The Hatter appears again in «Chapter Eleven – Who Stole the Tarts?», as a witness at the Knave of Hearts’ trial, where the Queen appears to recognise him as the singer she sentenced to death, and the King of Hearts also cautions him not to be nervous or he will have him «executed on the spot».

Through the Looking-Glass[edit]

The character also appears briefly in Carroll’s 1871 Through the Looking-Glass, the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Under the name of «Hatta,» the Hatter was in trouble with the law once again. He was, however, not necessarily guilty, as the White Queen explained that subjects were often punished before they commit a crime, rather than after, and sometimes they did not even commit one at all. He was also mentioned as one of the White King’s messengers along with March Hare, who went under the name of «Haigha.» Sir John Tenniel’s illustration depicts Hatta as sipping from a teacup as he did in the original novel. Alice does not comment on whether Hatta is the Hatter of her earlier dream.

Characterization[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Mercury was used in the manufacturing of felt hats during the 19th century, causing a high rate of mercury poisoning among those working in the hat industry.[1] Mercury poisoning causes neurological damage, including slurred speech, memory loss, and tremors, which led to the phrase «mad as a hatter».[1] In the Victorian age, many workers in the textile industry, including hatters, sometimes developed illnesses affecting the nervous system, such as central nervous system (CNS) tuberculosis, which is portrayed in novels like Alton Locke by Charles Kingsley and North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell, which Lewis Carroll had read. Many such workers were sent to Pauper Lunatic Asylums, which were supervised by Lunacy Commissioners such as Samuel Gaskell and Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, Carroll’s uncle. Carroll was familiar with the conditions at asylums and visited at least one, the Surrey County Asylum, himself, which treated patients with so-called non-restraint methods and occupied them, amongst others, in gardening, farming and hat-making.[2] Besides staging theatre plays, dances and other amusements, such asylums also held tea-parties.[3]

Appearance[edit]

Although, during the trial of the Knave of Hearts, the King of Hearts remarks upon the Hatter’s headgear, Carroll does not describe the exact style of hat he wears. The character’s signature top hat comes from John Tenniel’s illustrations for the first edition, in which the character wears a large top hat with a hatband reading «In this style 10/6». This is further elaborated on in The Nursery «Alice», a shortened version of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, adapted by the author himself for young children. Here it is stated that the character is wearing a hat on his head with a price tag containing the numbers 10 and 6, giving the price in pre-decimal British money as ten shillings and six pence (or half a guinea).[4]

Personality[edit]

Illustration of the March Hare, one of the Hatter’s tea party friends, by Sir John Tenniel.

The Hatter and his tea party friend, the March Hare, are initially referred to as «both mad» by the distinctive Cheshire Cat. The first mention of both characters occurs in the sixth chapter of Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, titled «Pig and Pepper», in a conversation between the child protagonist Alice and the Cheshire Cat, when she asks «what sort of people live about here?» to which the cat replies «in that direction lives a Hatter, and in that direction, lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad!» Both then subsequently make their actual debuts in the seventh chapter of the same book, which is titled «A Mad Tea-Party».

Hat making was the main trade in Stockport where Carroll grew up, and it was not unusual then for hatters to appear disturbed or confused; many died early as a result of mercury poisoning. However, the Hatter does not exhibit the symptoms of mercury poisoning, which include excessive timidity, diffidence, increasing shyness, loss of self-confidence, anxiety, and a desire to remain unobserved and unobtrusive.[5]

Resemblance to Theophilus Carter[edit]

It has often been claimed that the Hatter’s character may have been inspired by Theophilus Carter, an eccentric furniture dealer.[6][7] Carter was supposedly at one time a servitor at Christ Church, one of the University of Oxford’s colleges.[8] This is not substantiated by university records.[8] He later owned a furniture shop, and became known as the «Mad Hatter» from his habit of standing in the door of his shop wearing a top hat.[6][7] Sir John Tenniel is reported to have come to Oxford especially to sketch him for his illustrations.[6] There is no evidence for this claim, however, in either Carroll’s letters or diaries.[9]

Riddle[edit]

In the chapter «A Mad Tea Party», the Hatter asks a much-noted riddle: «Why is a raven like a writing desk?» When Alice gives up trying to figure out why, the Hatter admits «I haven’t the slightest idea!». Carroll originally intended the riddle to be without an answer, but after many requests from readers, he and others—including puzzle expert Sam Loyd—suggested possible answers; in his preface to the 1896 edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Carroll wrote:

Inquiries have been so often addressed to me, as to whether any answer to the Hatter’s riddle can be imagined, that I may as well put on record here what seems to me to be a fairly appropriate answer, «because it can produce a few notes, though they are very flat; and it is nevar put with the wrong end in front!» This, however, is merely an afterthought; the riddle as originally invented had no answer at all.[10][a]

Loyd proposed a number of alternative solutions to the riddle, including «because Poe wrote on both» (alluding to Poe’s 1845 narrative poem The Raven) and «because the notes for which they are noted are not noted for being musical notes». The April 2017 edition of Bandersnatch, the Newsletter of the Lewis Carroll Society [Issue 172, ISSN 0306-8404, Apr 2017], published the following solution, proposed by puzzle expert Rick Hosburn: «Why is a Raven like a Writing-desk?» «Because one is a crow with a bill, while the other is a bureau with a quill!» The RSPB, in its definition of Raven, states: «The raven […] is all black with a large bill, and long wings.» American author Stephen King provides an alternative answer to the Hatter’s riddle in his 1977 horror novel The Shining. Snowbound and isolated «ten thousand feet high» in the Rocky Mountains, five-year-old Danny hears whispers of the malign «voice of the [Overlook] hotel» inside his head, including this bit of mockery: «Why is a raven like a writing desk? The higher the fewer, of course! Have another cup of tea!»

In popular culture[edit]

The Hatter has been featured in nearly every adaptation of Alice in Wonderland to date; he is usually the male lead despite being a supporting character. The character has been portrayed in film by Norman Whitten, Edward Everett Horton, Sir Robert Helpmann, Martin Short, Peter Cook, Anthony Newley, Ed Wynn, Andrew-Lee Potts, and Johnny Depp. In music videos, the Hatter has been portrayed by Tom Petty, Dero Goi, and Steven Tyler. He has also been portrayed on stage by Nikki Snelson and Katherine Shindle, and on television by John Robert Hoffman, Pip Donaghy and Sebastian Stan. In ballet adaptations, Steven McRae also portrayed him as a mad ‘Tapper’.[11] In March 2019, Chelsy Meiss became the first female soloist to play the Mad Hatter for the National Ballet of Canada.[12]

Films[edit]

- In the 1951 Walt Disney animated feature Alice in Wonderland, the Hatter appears as a short, hyperactive man with grey hair, a large nose and a comical voice. He was voiced by Ed Wynn in 1951, and by Corey Burton in his later appearances (Bonkers, House of Mouse). Alice stumbles upon the Hatter and the March Hare having an «un-birthday» party for themselves. The Hatter asks her the infamous riddle «why is a raven like a writing desk?», but when she tries to answer the Hatter and the March Hare think she is «stark raving mad» and the Hatter completely forgot that he even asked her the riddle. Throughout the course of the film, the Hatter pulls numerous items out of his hat, such as cake and smaller hats. His personality is that of a child; angry one second, happy the next.

- The Hatter appears in Tim Burton’s 2010 version of Alice in Wonderland portrayed by Johnny Depp and given the name Tarrant Hightopp.[13] In the film, the Hatter takes Alice toward the White Queen’s castle and relates the terror of the Red Queen’s reign while commenting that Alice is not the same as she once was. The Hatter subsequently helps Alice avoid capture by the Red Queen’s guards by allowing himself to be seized instead. He is later saved from execution by the Cheshire Cat and calls for rebellion against the Red Queen. Near the end of the film, the Hatter unsuccessfully suggests to Alice that she could stay in Wonderland and consummate his feelings for her.Critical reception to Johnny Depp’s portrayal of the Hatter was generally positive. David Edelstein of New York Magazine remarked that while the elements of the character suggested by Depp don’t entirely come together, «Depp brings an infectious summer-stock zest to everything he does.»[14] Bill Goodykoontz of The Arizona Republic said that «Depp is exactly what you’d expect, which is a good thing. Gap-toothed and leering, at times he looks like Madonna after sticking a fork in a toaster. How he finds his characters is anybody’s guess, a sort of thrift-store warehouse of eccentricities, it seems like. But it works.»[15] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly had a more mixed opinion and commented that Depp as the Hatter is «a fantastic image, but once Depp opens his mouth, what comes out is a noisome Scottish brogue that makes everything he says sound more or less the same. The character offers no captivatingly skewed bat-house psychology. There isn’t much to him, really—he’s just a smiling Johnny one-note with a secret hip-hop dance move—and so we start to react to him the way that Alice does to everything else: by wondering when he’s going to stop making nonsense.»[16] Kenneth Turan of Los Angeles Times stated that «there’s no denying Depp’s gifts and abilities, but this performance feels both indulgent and something we’ve all seen before.»[17]

- The Hatter is played by Clarke Peters in the 2020 movie Come Away. He is depicted as the father of Captain Hook, the grandfather of Alice and Peter Pan, and the great-grandfather of Wendy Darling, John Darling, and Michael Darling.

Television[edit]

- The Hatter was also a semi-regular on the Disney Afternoon series Bonkers and one of the guests in House of Mouse, where he even made a cameo appearance in one of the featured cartoon shorts.

- The TV series Futurama has a robot named Mad Hatterbot who is based on the Hatter. Seen only in the HAL Institute (an asylum for criminally insane robots) the Mad Hatterbot only says one line: «Change places!», which all in the room comply with when spoken. The price tag on his hat reads «5/3», exactly half of 10/6. A minor character, he has been in the episodes «Insane in the Mainframe» and «Follow the Reader» as well as the film Futurama: Bender’s Game.

- In Syfy’s Alice, the Hatter (Andrew-Lee Potts) is portrayed as a smuggler who starts off working as a double agent for the Queen of Hearts and the Wonderland Resistance in the story; over the course of the story, he begins to side more and more with the Resistance, and ends up falling in love with Alice as he helps her along the way.

- In Once Upon a Time, the Mad Hatter is presented as possessing the unique ability to cross dimensions through his hat, and has a daughter, Grace, who lost her mother Priscilla[18] as a result of a past deal with the Evil Queen. When the Queen offers him enough wealth to set his daughter up for life, he agrees to help her travel to Wonderland, but when it is revealed that the goal was for the Queen to retrieve her captured father, the Hatter is left trapped in Wonderland instead, as the portal will only allow two people to pass through it in either direction. Trapped in Wonderland, he was then driven mad as he attempted to find another way back to his world to reunite with his daughter. In the first season, trapped in the Land Without Magic, the Mad Hatter- now known as ‘Jefferson’ as he lives in a mansion just on the outskirts of Storeybrooke- is one of the few who remembers his original life due to his insanity. His daughter has also been brought into Storeybrooke, but he has avoided making contact with her due to her new memories meaning that she would not recognise him. Unable to harness magic in this world, he attempts to recruit Emma to make a hat for him, but she is unable to harness her power, although Jefferson’s knowledge of the curse gives Emma further proof that Henry is telling the truth. Regina later recruits Jefferson to help her create a curse to use on Emma, but Regina’s efforts backfire and give Emma clear proof that the curse is real. In the second season, with the curse broken, Jefferson is eventually convinced to reunite with his daughter.

- In the Netflix’s Ever After High episode «Spring Unsprung», the Mad Hatter makes an appearance as Madeline Hatter’s father. In the 47-minute special, he runs the Mad Hatter’s Tea Shoppe in the town of Bookend, not far from Maddie’s school Ever After High. He also runs a shop by the same name in Wonderland, but it was abandoned after the Evil Queen (Raven Queen’s mother) cast a curse upon the land.

Video games[edit]

- In the 2000 video game American McGee’s Alice, The Mad Hatter is portrayed as psychotic, literally gone «mad» and obsessed with time and clockworks, and considers himself to be a genius. He invents mechanical devices, often evidently using the bodies of living organisms for the base of his inventions, as he plans to do to all of Wonderland’s inhabitants. He appears in the 2011 sequel Alice: Madness Returns in the same appearance, although this time, he requests Alice’s help in retrieving his lost limbs from his former compatriots the March Hare and Dormouse. The Hatter’s fixation on time might be based on the unseen character Time, which might explain why he replaced his body with cogs and gears as he sees Time as some type of god.

- The Hatter makes a cameo appearance in a painting in the Tea Party Garden in the 2002 video game Kingdom Hearts.

- The Mad Hatter appeared in the Sunsoft’s 2006 mobile game Alice’s Warped Wonderland (歪みの国のアリス, Yugami no kuni no Arisu, Alice in Distortion World). The Mad Hatter is portrayed as a middle-school age boy in oversized clothes and a large hat that covers his whole head. Unlike most Wonderland residents, he acts rather bratty and rude to Ariko (the «Alice» of the game). In one of the bad endings, Mad Hatter is killed by a twisted Cheshire Cat.[19][20]

- In Get Even, one of the asylum patients wearing the Pandora headsets dresses as the Hatter and has a tea party in his cell, he gives Cole Black a riddle to get the door open, there is a choice option to leave him in his room or set him free to which he’ll join the other inmates to kill Black, who they all believe is the «Puppet Master».

Music[edit]

- The song «Mad Hatter» by an American garage rock band Shag was inspired by the character. It appeared on their self-titled album in 1969.

- Sir John Tenniel’s drawing of the Hatter, combined with a montage of other images from Alice in Wonderland, were used as a logo by Charisma Records from 1972 onwards.

- A Burton’s inspired Mad Hatter appears in «The Man who became a Rabbit» music video, an Indian version of Alice in Wonderland by Valérian MacRabbit and Lalkrishnan. Mad Hatter becomes Mac Hatter and gives one riddle to the main character : «Spread blood on the birthday cake».[21]

- The Mad Hatter’s name is used in Elton John’s 1972 song Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters.

- The Mad Hatter is referenced to in the eponymous 2015 song by Melanie Martinez, next to a few other characters from Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.[2]

Live performance[edit]

- The Hatter is a greetable character at the Disneyland Resort, Walt Disney World Resort, Tokyo Disney Resort, Disneyland Paris Resort and Hong Kong Disneyland.

- Shrek The Musical, the Mad Hatter plays a small role as a fairytale creature (replacing the Gnome) and has two lines in songs including «They ridiculed my hat» and «I smell like sauerkraut».

- Frank Wildhorn composed the music to and co-wrote the music to Wonderland: A New Alice. In this adaption the Hatter is portrayed as a female, the villain of the story, and Alice’s alter-ego and is a mad woman who longs to be Queen. She was played by Nikki Snelson in the original Tampa, Florida production, and then by Kate Shindle in the Tampa/Houston Tour, and the production on Broadway.

Comic strips and books[edit]

- The Mad Hatter (also referred to as «Jervis Tetch») is a supervillain and enemy of the Batman in DC comic books, making his first appearance in the October 1948 (#49) release of Batman.[22] He is portrayed as a brilliant neurotechnician with considerable knowledge in how to dominate and control the human mind.[23] Jervis had a obsession over Lewis Carroll’s books that he believes himself to be the reincarnation of the Mad Hatter, including making his henchmen wear outfits based on the Wonderland characters and kidnapping women and force them to dress and named them Alice.

- A spin-off of the traditional Alice in Wonderland story, Frank Beddor’s The Looking Glass Wars features a character named Hatter Madigan, a member of an elite group of bodyguards known in Wonderland as the «Millinery» after the business of selling women’s hats. He acts as the bodyguard of the rightful Queen, and as guide/guardian to the protagonist, Alyss Heart.

- The Mad Hatter in Pandora Hearts manga series is a chain (creature from the Abyss) that was contracted by Xerxes Break. The hatter basically looks like a large top hat with flowery decorations (similar to Break’s top hat) and a tattered cape. When summoned, it can destroy all chains and objects from the Abyss within a large area.

- The Japanese manga Alice in the Country of Hearts has been translated into English. The Hatter role is played by Blood Dupre, a crime boss and leader of a street gang called The Hatters, which controls one of the four territories of Wonderland.

Toys[edit]

- The Hatter has a daughter named Madeline in Ever After High toy line.

See also[edit]

- March Hare

- Dormouse

Notes[edit]

- ^ Here, Caroll deliberately spelled the word «never» as «nevar», which is «raven» backward.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Myers 2003, p. 276.

- ^ a b Kohlt, Franziska (26 April 2016). «‘The Stupidest Tea-Party in All My Life’: Lewis Carroll and Victorian Psychiatric Practice». Journal of Victorian Culture. 22 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1080/13555502.2016.1167767.

- ^ Tuke, Samuel (1813). Description of the Retreat, an institution near York, for insane persons of the Society of Friends : containing an account of its origin and progress, the modes of treatment, and a statement of cases. York: Philadelphia : Published by Isaac Peirce … p. 111.

- ^ Lewis, Carroll. The Nursery ‘Alice’. Macmillan. p. 40. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Waldron, H. A. (24 December 1983). «Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning?». British Medical Journal. 287 (6409): 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1961. PMC 1550196. PMID 6418283.

- ^ a b c Hancher 1985, p. 101.

- ^ a b Millikan, Lauren (5 March 2011). «The Mad Hatter». Carleton University. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ a b Collingwood 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Maters, Kristin (27 January 2014). «Who Really Inspired Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ Characters?». Books Tell You Why. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ «The Mad Hatter’s riddle: why is a raven like a writing desk?». Alice in Wonderland Net. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: «Becoming The Mad Hatter: Steven McRae on Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (The Royal Ballet)» (video). YouTube. 26 October 2017.

- ^ «The first woman to play the Mad Hatter!» (video). 7 March 2019.

- ^ «Alice in Wonderland – Glossary of Terms/Script (early draft)» (PDF). Walt Disney Pictures. JoBlo.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ David Edelstein (28 February 2010). «David Edelstein on ‘Alice in Wonderland’, ‘The Yellow Handkerchief’, and ‘The Art of the Steal’ — New York Magazine Movie Review». New York Magazine. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Bill Goodykoontz (3 March 2010). «Alice in Wonderland». The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman (3 March 2010). «Alice in Wonderland Review». Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Kenneth Turan (4 March 2010). «Review: ‘Alice in Wonderland’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ Her name is revealed in Once Upon a Time: Out of the Past («Tea Party in March»).

- ^ «Alice’s Warped Wonderland«. Sunsoft. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ «Alice’s Warped Wonderland ~Encore~». Sunsoft. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ «The Man who became a Rabbit», Lalkrishnan / Valérian MacRabbit, The Freak Parade (2018)

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane and Lew Sayre Schwartz (p), Charles Paris (i). «The Scoop of the Century» Batman 49 (1948), DC Comics

- ^ Fleisher, Michael L. (1976). The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, Volume 1: Batman. New York City: Macmillan Publishing. pp. 268–269. ISBN 0-02-538700-6. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Sources[edit]

- Collingwood, Stuart (2011). The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. Cambridge University. ISBN 978-1108033886.

- Hancher, Michael (1985). The Tenniel Illustrations to the «Alice» Books. Ohio State University. ISBN 978-0814204085.

- Myers, Richard (2003). The Basics of Chemistry. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313316647.

External links[edit]

- Alice in Wonderland — The Mad Hatter! on YouTube

История персонажа

Английский математик и писатель Льюис Кэрролл придумал персонажа по имени Безумный Шляпник, работая над сказкой «Приключения Алисы в Стране чудес». В некоторых вариантах перевода герой получил имя Болванщик, но чаще его называют привычным аудитории прозвищем.

Чтобы понять, что персонаж не от мира сего, необязательно вчитываться в пояснения Чеширского кота и разбираться в философствованиях героев на темы безумия. Его поведение странно и оправдывает имя. В полном загадок произведении Кэрролла герой находит себе уютное место в повествовании и становится самостоятельным персонажем в веренице невероятных героев.

Льюис Кэрролл – обладатель незаурядной фантазии, позволившей совместить любовь к математике и талант писателя. В литературе автор реализовал себя в фантастическом жанре. Помимо «Алисы в Стране чудес» он написал книги «Алиса в Зазеркалье», «Логическая игра» и «Математические курьезы».

Сказка об Алисе, попавшей в Страну чудес, – не просто фантастическая история, а продуманная цепочка ребусов и головоломок. Математик, любивший метафоры и загадки, наполнил символичными изображениями свои произведения.

История создания

Безумный Шляпник стал персонажем, чей образ эксплуатируется в современных сюжетах и легендах. Впервые зритель видит героя в сцене чаепития в книге «Алиса в Стране чудес». В мире Зазеркалья Кэрролл выводит нового персонажа – Болванса Чика, похожего на использованного ранее героя. Он также предстает перед публикой в седьмой главе книги.

Прототип Шляпника, по легенде, – продавец мебели Теофил Картер, непредсказуемый и эксцентричный герой, который носил прозвище Безумный Шляпник. Он, во-первых, всегда носил шляпу, а во-вторых – придумывал сумасшедшие штуки вроде кровати-будильника, сбрасывающей спящего на пол.

Роджер Крэбб тоже мог стать прообразом героя. Это солдат, поступивший на службу в 1642 году и получивший контузию в атаке на шотландцев. Удар повлиял на разум, и после увольнения ставший шляпником служивый не раз удивлял окружающих своим поведением.

Загадка Безумного Шляпника кроется еще и в том, что его характер является визуальным воплощением редкого заболевания. Болезнь под названием меркуриализм описывает отравление ртутными парами. Поражение веществом фиксировалось в 19 веке у работников, производящих шляпы. Нитрат ртути применялся для размягчения шерстяной материи при изготовлении фетра.

В помещениях не хватало свежего воздуха, нервная система работников подвергалась поражению, и симптомы отравления становились очевидными. Люди испытывали галлюцинации, чрезмерную эмоциональность, проблемы со зрением и слухом. Окружающие воспринимали их как умалишенных или безумцев, что дало повод для появления поговорки «as mad as a hatter» – «безумен, как шляпник».

Безумный Шляпник в произведениях

Непосредственный и наивный герой привлекает внимание читателя с момента первого появления на страницах произведения. Безумный Шляпник, характер которого отличается благородством, смелостью, харизмой и некоторой стеснительностью, талантлив и незауряден.

Он творец и фантазер, улыбающийся жизненным невзгодам в лицо. В сказке Льюиса Кэрролла он пьет чай с Мартовским зайцем и рассказывает о том, как был обвинен Королевой червей в убийстве времени. Шляпнику грозит казнь. Время, обидевшись на героя, остановилось. Теперь вместе с приятелем Мартовским зайцем Шляпник живет в нескончаемом пятичасовом перерыве на чай.

Участники мероприятия меняются местами, делают друг другу замечания, философствуют, произносят бессмысленные фразы и абстрагируются от Алисы. Второе появление Безумного Шляпника происходит на суде с участием Валета червей. Герой волнуется, что королева узнает его, но избегает казни.

В продолжении сказки персонаж оказывается под прицелом местного законодательства, но в этот раз он виноват лишь в перспективе. Персонаж выступает королевским глашатаем.

Безумный Шляпник – яркий образ повествования. Его внешность примечательна. Это молодой человек, неопрятный, но галантный джентльмен. Мастер, знающий толк в шляпах и умеющий делать парики. Крохотную Алису он доставляет в королевский дворец в головном уборе.

Экранизации

Впервые «Алиса в Стране чудес» была экранизирована в 1903 году. Сесил Хэпуорт снял 12-минутное немое кино. В проекте он взял на себя несколько функций и выступил как режиссер, оператор, актер, сценарист и продюсер ленты.

Образ Безумного Шляпника неоднократно воплощали талантливые артисты, создавая неповторимый облик героя. В сериале 1999 года Мартин Шорт воплотил образ, описанный в книге, и полностью соответствовал характеристике героя.

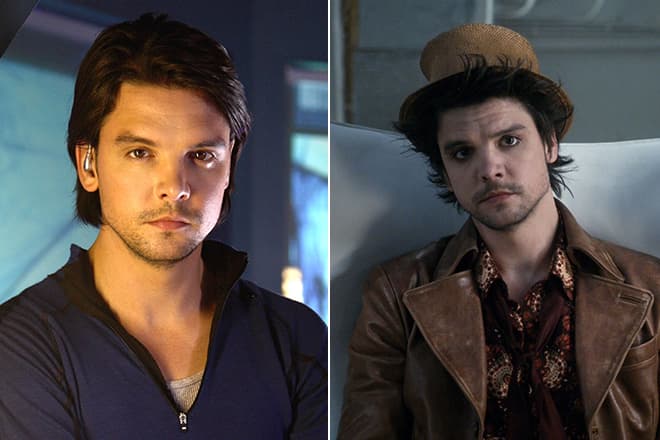

В мини-сериале «Алиса» представил образ Шляпника Эндрю Ли Поттс. Молодой человек в твидовой шляпе и кожаном пиджаке занимался благотворительностью, продавая эмоции. В ленте Шляпник становился возлюбленным Алисы.

Главным воплотителем образа Безумного Шляпника в последние десятилетия стал Джонни Депп. Неповторимый макияж персонажа в ленте Тима Бертона не оставил зрителей равнодушными. Мастер перевоплощения, Джонни Депп носил яркий рыжий парик и зеленые линзы, а его лицо было выбелено. Красочный костюм персонажа состоял из массы инструментов, пригодных для изготовления шляп. Он создавал впечатление безумца, отравившегося психотропным составом вроде клея.

По сюжету «Алисы в Стране чудес» снят сериал под названием «Однажды в сказке». Роль Шляпника в нем играет Себастиан Стэн, появляющийся на экране в первых трех сериях. Повествование гласит, что он живет в сказке о Белоснежке с дочкой Грейс. Они зарабатывают на жизнь продажей лесных грибов королеве и путешествуют от сказки к реальности в шляпе.

Цитаты

Льюис Кэрролл вложил в уста шляпника философские и юмористические цитаты, ставшие афоризмами.

«Нынче все ездят по железной дороге, но шляпные перевозки куда надежней и приятней».

Так говорит Шляпник, любезно предоставляя свой головной убор Алисе в качестве транспортного средства. Жизнеутверждающие реплики героя поддерживают героев и служат мотиватором для детской и взрослой читательской аудитории.

«Возможно, если ты в это веришь!»

Мечтательный сказочник провозглашает истины, актуальные для общества любого времени:

«Чем меньше знаешь, тем легче тобою управлять».

«Безумцы всех умней»

Это говорит отец Алисы, и эта фраза как нельзя лучше характеризует благородного и порядочного Шляпника. Он всегда выручит, неловко заявляя что-то вроде:

«А нужна причина, чтобы помочь очень милой девушке в очень мокром платье?»

Образ Шляпника романтизирован. Чтобы сделать его еще необычнее, Кэрролл подарил персонажу способность разговаривать на собственном языке, коверкая слова:

«Знаешь, Алиса, тебе стало не хватать гораздости…».

Не стоит забывать, что доля сумасшествия в образе Шляпника является неотъемлемой частью сущности, поэтому из его уст вырывается понятная одному ему тарабарщина:

«Ты думал лишь о собственном спасении, труснявый гадлый сверхноблохнущий брюхослизлый злыдный обжорст подлыймурк пахлорыбный?»

| Болва́нщик | |

| Mad Hatter | |

|

|

| Безумный Шляпник Джона Тенниела | |

| Создатель: | Льюис Кэрролл |

| Произведения: | Приключения Алисы в Стране Чудес, Алиса в Зазеркалье |

Болва́нщик (англ. Hatter, буквально Шляпник, в русских переводах также Шляпник (В. Набоков, Ю. Нестеренко, Н. Старилов), Шляпа (Б. Заходер), Шляпочник (А. Щербаков), Сапожник (А. Кононенко)) — персонаж из «Приключений Алисы в стране чудес» Льюиса Кэрролла; такое имя носит в переводе Н. Демуровой. Впервые встречается в сцене чаепития (глава 7, «Безумное чаепитие»). В продолжении, повести «Алиса в Зазеркалье», присутствует похожий персонаж по имени Болванс Чик (перевод Н. Демуровой, англ. Hatta) и впервые встречается также в седьмой главе. Его часто называют «Безумный Шляпник», но не в книге, хотя Чеширский кот предупреждает Алису о том, что тот безумен, подтверждением чему служит странное поведение Шляпника.

Содержание

- 1 Болванщик в повестях Кэрролла

- 2 «Безумен, как шляпник»

- 3 10/6

- 4 Прототип

- 5 Загадка Безумного Шляпника

- 6 Шляпник в кино

- 7 Видео-игры

- 8 Знаете ли вы что

- 9 Примечания

- 10 См. также

- 11 Литература

Болванщик в повестях Кэрролла

Болванщик объясняет Алисе, что он и Мартовский заяц всегда пьют чай потому, что во время исполнения Болванщиком песни на празднике Королевы червей она обвинила его в «убийстве времени» и приказала обезглавить. Вне себя от ярости за попытку убийства, Время (в отношении которого здесь употребляется одушевленное местоимение, что нехарактерно для английского языка) остановило себя для Болванщика, заставив его и Мартовского зайца всегда жить так, как будто сейчас 6 часов. Участники чаепития все время пересаживаются, делают друг другу бестактные замечания, загадывают неразрешимые загадки и цитируют бессмысленные стихи, и возмущенная Алиса в конце концов уходит. Болванщик появляется вновь в качестве свидетеля на суде по делу Валета червей. Королева, кажется Болванщику, узнает в нем певца, которого она приговорила к смерти, а Король предупреждает его, чтобы тот не нервничал, иначе будет «казнен на месте».

Болванс Чик попивает чай

В «Алисе в Зазеркалье» у Болванщика опять неприятности с законом. В этот раз он, однако, может быть и невиновен: Белая Королева объясняет, что часто осуждённых наказывают до того, как они совершат преступление, а не после, и иногда они его и вовсе не совершат. Он также упоминается в качестве одного из королевских гонцов, вместе с Мартовским зайцем, названным здесь Зай Атс. Король объясняет, что ему нужны два гонца, так как «один бежит туда, а другой — оттуда». На иллюстрации Тенниела Болванс Чик изображен потягивающим чай из чашки точно так же, как это делал Шляпник в первой повести, подтверждая авторские отсылки к этому персонажу.

«Безумен, как шляпник»

Имя Безумный шляпник (Mad Hatter), как иногда называют Болванщика, обязано своим происхождением, без сомнения, английской поговорке «безумен, как шляпник» («mad as a hatter»). Происхождение же самой поговорки, возможно, объясняется следующим образом. Поскольку в процессе выделки фетра, использовавшегося для изготовления шляп, применялась ртуть, шляпники вынуждены были вдыхать её пары. Шляпники и работники фабрик часто страдали от ртутного отравления, так как пары ртути вредили нервной системе, вызывая такие симптомы, как спутанная речь и искажение зрения. Часто это приводило к ранней смерти. Тем не менее, Безумный Шляпник не выказывает симптомов ртутного отравления, которые включают в себя «чрезмерную застенчивость, неуверенность, возрастающую стеснительность, потерю уверенности в себе, беспокойство и желание оставаться скромным и незаметным»[1].

Необходимо отметить, что перевод имени Шляпника словом «Болванщик» на русский язык с точки зрения спектра значений, сопоставляемых этому слову в русском языке, представляется наиболее удачным. Слово «шляпник», по всей видимости, вызывает в памяти англичан приведенную выше поговорку; таким образом, безумие является одной из коннотаций слова. В русском же языке слово «Болванщик» также обозначает и профессию, связанную с изготовлением болванок для чего-либо, в том числе и профессию шляпного мастера; и, с другой стороны, вызывает ассоциации со словом «болван», выполняя те же художественные задачи, что и слово «Hatter» в оригинале Кэрролла.

10/6

Безумное чаепитие

На иллюстрации Тенниела к сцене чаепития на шляпе Болванщика изображена карточка или ярлык с надписью «10/6 в этом стиле» (англ. In this style 10/6). Число «10/6» означает 10 шиллингов 6 пенсов, цену шляпы в английских деньгах до их перевода в десятичную систему, и служит ещё одним доказательством занятий Болванщика.

Прототип

Один из прототипов Болванщика, как считается, — Теофил Картер, бывший предположительно студентом Крайст-Чёрч (как и Кэрролл), одного из колледжей Оксфордского университета. Он изобрел кровать с будильником, выставлявшуюся на Всемирной выставке 1851 года: она скидывала спящего, когда нужно было вставать. Затем он стал владельцем магазина мебели и благодаря своей привычке стоять в дверях магазина в высокой шляпе получил прозвище Безумный Шляпник (Mad Hatter). По некоторым сведениям, Джон Тенниел приезжал в Оксфорд специально для того, чтобы сделать с Картера наброски для своих иллюстраций.

Другой прототип — Роджер Крэб из Чешэма, Бакингемшир. Он поступил в 1642 году на службу в армию, которая впоследствии стала Армией нового образца Оливера Кромвеля. Крэб был хорошим солдатом; в этом ему помогал рост в 2 метра, ужасавший противников. В течение последующих нескольких лет он вместе с «круглоголовыми» сокрушал восстания в Ирландии и Шотландии. Во время осады Кольчестера в 1648 году он получил сильный удар по голове от солдата-роялиста. В результате был уволен с военной службы раньше срока и вернулся в родной город Чешэм, где занялся шляпным делом.

Крэб был успешным предпринимателем, однако полученный удар давал о себе знать. Он продал бизнес и раздал деньги бедным. Вел уединенный образ жизни, жил в деревне недалеко от Аксбриджа и стал пацифистом. Затем переехал в глухую деревню Бетнал Грин (ныне район Лондона), где жил на 3 фартинга в неделю, ел траву, просвирник и листья щавеля. Затем у Крэба обнаружился талант предсказателя. Примечательно, что, согласно одному из его видений, монархия должна была быть восстановлена, и в 1660 году трон занял Карл II, сын казненного Карла I. Травяная диета не причинила Крэбу вреда, несмотря на почтенный возраст. Он умер в 1680 году, дожив до 79 лет. Эпитафия на его могиле на кладбище церкви Святого Данстана в лондонском районе Степни гласит: «Дурная, добрая молва — все миновало без следа; корим бывал, но признан под конец… всему благому друг».

Загадка Безумного Шляпника

В главе «Безумное чаепитие» (глава 7) Безумный Шляпник загадывает примечательную загадку: «Чем ворон похож на письменный стол?» («конторку» в переводе Н. Демуровой). Когда Алиса сдается, Болванщик признает, что сам не знает ответа. Кэрролл изначально задумывал, что это будет просто загадка без ответа, но после огромного количества вопросов от читателей он и другие, включая специалиста по головоломкам Сэма Лойда, стали придумывать возможные ответы. Один из них — «Poe wrote on both» [«По писал на/об обоих.»]. Имеется в виду известный поэт и писатель Эдгар По, который писал на столе и писал о Во́роне («Ворон» — название одного из его известнейших стихотворений); в обоих случаях перед существительным (в нашем примере — числительным) в английском языке стоит wrote on. Таким образом, разгадка становится возможной благодаря игре слов, основанной на предлоге on, который употребляется и как русский предлог «на», и как русский предлог «о». В предисловии к изданию 1896 года Кэрролл писал:

| Меня так часто спрашивают относительно того, можно ли придумать какой-либо ответ на загадку Болванщика, что я мог бы заявить здесь тот ответ, который кажется мне в достаточной степени подходящим, а именно: «Потому что он может служить источником звуков/заметок [игра слов: «notes» означает и «звуки», и «заметки»], хоть и достаточно низких/плоских [опять игра слов: «flat» означает и «более низкий» (в отношении ноты), и «плоский»], его никогда не ставят неправильно!» Это, тем не менее, всего лишь пришедшая задним числом мысль; первоначально загадка не имела ответа вообще». [2] |

Также есть довольно простой вариант ответа: «На обоих есть перья». «Обществом безумного чаепития» именовали сообщество философов Б. Рассела («Болванщик»),Дж. Мура и Дж. Мак-Таггарта. Прозвище было мотивировано внешним сходством с персонажами Тенниела (в наибольшей степени это касалось Рассела), а также интересом Рассела к языковым парадоксам.[источник не указан 757 дней]

Шляпник в кино

Киновоплощения Шляпника. Слева направо: версия Диснея, Мартин Шорт, Эндрю Ли-Поттс, Джонни Депп

Себастиан Стэн в роли Безумного Шляпника: слева — в сказке, справа — в реальном мире

- В диснеевском мультфильме Шляпник выглядит как старичок в жёлтом костюме и зелёной шляпе с биркой. Его характер соответствует книге.

- В сериале 1999 года Шляпник и внешностью, и поведением скопирован с книги. Его сыграл Мартин Шорт.

- В минисериале Алиса Шляпника играет Эндрю Ли Поттс. Он одет в твидовую шляпу, коричневый кожаный пиджак и цветастую рубашку. Он занимается благотворительностью, продавая наподобие лекарств человеческие эмоции, в чём ему помогает Соня. Алиса первое время ему не доверяет, и даже не раскрывает свои планы, пока он не спасает её от Безумного Марча (Мартовский Заяц, переделанный в наёмного убийцу). Алиса и Шляпник влюбляются в друг друга, и становятся партнёрами. В финале, когда Алиса возвращается на землю, Шляпник следует за ней и они остаются вместе.

- В фильме Тима Бёртона Шляпника играет Джонни Депп. Здесь его полное имя — Тэррант Хайттоп. Он очень предан Белой Королеве и также влюбляется в Алису, поэтому постоянно её защищает. У него косые ярко-зелёные глаза, ярко-рыжие волосы и весьма красочный костюм, в котором собраны разные инструменты для изготовления шляп. У Шляпника очень бледная кожа и цветные ногти, что является намеком на отравление шляпным клеем.

- В сериале Однажды в сказке Шляпник (в исполнении Себастиана Стэна) появляется в трёх сериях первого сезона, его имя — Джефферсон. В сериале выясняется, что он родом из мира Белоснежки и имеет дочь Грейс, вместе с которой живёт в лесу. Деньги зарабатывает от продажи грибов. Когда-то он торговал между мирами, используя для перемещения между ними свою волшебную шляпу. Реджина нанимает его помочь ей вернуть отца из Страны Чудес. Ради счастья дочери Джефферсон помогает ей, но она его обманывает и оставляет в Стране Чудес. Желая вернуться домой к дочери, Джефферсон сходит с ума и пытается собрать новую волшебную шляпу, но безуспешно. В реальном мире он помнит свою прошлую жизнь и по-прежнему мечтает вернуть дочь, поэтому помогает Эмме Свон снять с города Сторибрука проклятье и освобождает Белль из психиатрической клиники.

Видео-игры

Шляпник в играх Американа МакГи

- В игре American McGee’s Alice Шляпник, помешанный на часах и времени, предстает в качестве отрицательного персонажа. Он раздавил ударом ноги Белого Кролика, а также ставил опыты над мышью Соней и Мартовским Зайцем.

- В игре Alice: Madness Returns Шляпник меняет амплуа на положительного персонажа. Соня и Мартовский заяц сошли с ума и разобрали Шляпника на составные части, но Алиса собирает его заново. В обмен на помощь, Шляпник приносит Алису к месту, где был построен Адский поезд. Впоследствии прямо на месте сходит с ума.[3]

- В игре по фильму Бёртона Шляпник — один из играбельных персонажей. Способен совмещать предметы.

Знаете ли вы что

Известный математик Норберт Винер в своих воспоминаниях пишет о внешности философа Бертрана Рассела, как похожего на Болванщика:

- Бертрана Рассела можно описать одним-единственным способом, а именно — сказав, что он вылитый Болванщик… Рисунок Тенниела свидетельствует чуть ли не о провидении.

Примечания

- ↑ Waldron HA (1983). «Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning?». British Medical Journal 287 (6409): 1961. DOI:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1961. PMID 6418283.

- ↑ Trivia — Lenny’s Alice in Wonderland site

- ↑ Кирилл Волошин Alice: Madness Returns. Вердикт. Игромания (журнал) (01.07.2011). Архивировано из первоисточника 31 января 2012.

См. также

- Бертран Рассел

Литература

- Галинская И. Л. Льюис Кэрролл и загадки его текстов.

| |

|

|---|---|

| Персонажи «Страны чудес» |

Алиса • Белый кролик • Мышь • Додо • Робин-Гусь • Попугайчик Лори • Орлёнок Эд • Ящерка Билль • Гусеница • Герцогиня • Чеширский Кот • Болванщик • Мартовский заяц • Соня • Червонная Королева • Червонный Король • Червонный Валет • Грифон • Черепаха Квази • Пэт • Кухарка • Карточные стражи |

| Персонажи «Зазеркалья» |

Алиса • Чёрная Королева • Белая Королева • Чёрный Король • Белый Король • Рыцарь на Белом коне • Траляля и Труляля • Овца • Шалтай-Болтай • Бармаглот • Зай Атс • Болванс Чик • Лев и единорог |

| Фильмы |

Сесиля Хепуорта (1903) • Нормана Маклауда (1933) • Уильяма Стерлинга (1972) • Бада Таунсенда (1976) (порно) • Терри Гиллиама (1977) • Гарри Харриса (1985) • Яна Шванкмайера (1988) • Ника Уиллинга (1999 • 2009) • Тима Бёртона (2010) |

| Мультфильмы |

Уолта Диснея (1951) • Джонатана Миллера (1966) • Ефрема Пружанского (1981 • 1982) • аниме Nippon Animation (1983) • Рича Трублада (1988) • (1995) |

| Другое |

Радиопьеса (1976) • Альбом Тома Уэйтса (2002) • Аудиокнига (2007) • Морж и Плотник • Расположение персонажей на шахматной доске • Время в Зазеркалье • Гриб • Аннотированная Алиса • Игры: American McGee’s Alice • Alice: Madness Returns |

| Персоналии |

Алиса Лиддел • Джон Тенниел • Нина Демурова (переводчик) |

Безумный Шляпник – персонаж мультфильма «Алиса в Стране Чудес» 1951 года.

| Появления | Алиса в Стране Чудес

Вот твоя жизнь, Дональд Дак Чокнутый Всё о Микки Маусе Король Лев 1.5 Мышиный Дом |

| Вид | Человек |

| Род занятий | Шляпник |

| Цель | Веселиться |

| Союзники | Мартовский Заяц, Мышь-Соня, Алиса, Чокнутый, Гарри Сумка |

| Враги | Дама Червей |

| Способности | Может сломать что угодно |

| Судьба | Покинул сон Алисы и переселился в Лос-Анджелес |

| Цитата | «Мы тут празднуем не-именины!» |

Характер

Шляпник – один из самых шумных, эксцентричных и безумных обитателей Страны Чудес. С гостями, такими, как Алиса, он чуть более вежлив и тактичен, чем прямолинейный Мартовский Заяц.

И Шляпнику, и Зайцу нравится петь, но, по словам Шляпника, их пение никто не хвалит, скорее всего, потому, что никто, кроме них самих и Мыши-Сони, не ходит на их безумное чаепитие. Судя по сцене с часами Белого Кролика, они безумны даже по стандартам Страны Чудес и, возможно, являются изгоями в её обществе.

Появления

Алиса в Стране Чудес

Алиса пыталась рассказать, зачем она пришла, но Заяц и Шляпник всё время меняли темы разговора. Вскоре появился ещё один незваный гость: Белый Кролик, который куда-то опаздывал. Услышав об этом, Шляпник схватил его карманные часы и заявил: «Неудивительно – они же отстают на два дня!» Он попытался починить часы, но в итоге они окончательно спятили, и Мартовскому Зайцу пришлось разбить их молотком.

Безумный Шляпник был одним из свидетелем на суде над Алисой, который устроила Дама Червей. Когда его спросили, где он был, он честно ответил, что сидел дома, пил чай и праздновал не-именины. Тут Король Червей сообразил, что у его жены сегодня тоже не-именины. Шляпник и Заяц попытались устроить безумное чаепитие прямо в суде, однако его случайно сорвало появление Чеширского Кота. Услышав, что рядом кот, Соня перепугался; начался бардак, в котором незаслуженно обвинили Алису. Шляпник и Заяц сбежали из здания суда, а потом появились в мультфильме ещё один раз – когда Алиса удирала от солдат и пробегала мимо их очередного чаепития.

Вот твоя жизнь, Дональд Дак

Шляпник был в толпе диснеевских персонажей, поздравлявших Дональда в конце мультфильма.

Чокнутый

Позже Шляпник появился в сериале ещё несколько раз; самая заметная роль у него в эпизоде «В сумке». В нём он вызвал полицию после того, как у него и Мартовского Зайца украли чайный сервиз. Потом стали пропадать и другие вещи Шляпника, в том числе Мартовский Заяц. Наконец, исчез и сам Шляпник; в конце эпизода выяснилось, что всё это похитил клептоман Гарри Сумка, которому очень не хватало компании. Полицейские хотели арестовать вора, но Шляпник заявил, что теперь эта сумка – его друг.

Всё о Микки Маусе

Шляпник на короткое время появляется в эпизоде «Автомеханики», где говорит, что купил свой цилиндр в магазине шляп в Тунтауне (городе, где живёт Чокнутый).

Король Лев 1.5

В финальной сцене Безумный Шляпник пришёл в кинотеатр, чтобы посмотреть новый мультфильм про Тимона и Пумбу.

Мышиный Дом

Безумный Шляпник – частый гость Мышиного Дома. Обычно он пьёт чай за одним столом с Мартовским Зайцем или Алисой.

В эпизоде «Дональд шутит над Пумбой» Шляпник хохотал над старым мультфильмом про Дональда Дака.

В эпизоде «Отключённый клуб» Микки Маус сообщил, что кто-то в неположенном месте припарковал гигантскую чашку. Шляпник понял, что речь идёт о его транспорте, и пошёл её отогнать, после чего прошёл обратно в клуб между далматинцами и Зевсом. Впрочем, он снова ушёл, когда в клубе вырубился свет.

В эпизоде «Дебют Дейзи» Шляпник хотел получить роль Джинна в «Аладдине», но передумал, когда понял, что волшебная лампа не является чайником.

В эпизоде «Ужин от Гуфи» Безумный Шляпник позвонил по мобильному телефону Дейзи Дак и спросил, можно ли в Мышином Доме отпраздновать не-именины. Когда Гуфи на время заменил Дейзи, Шляпник был посажен за один стол с Клодом Фролло (который был, мягко говоря, не в восторге).

В эпизоде «Смущающее свидание Макса» у Безумного Шляпника было свидание с миссис Поттс.

В эпизоде «Спросите фон Дрейка» Шляпник пытался использовать рукав своей рубашки как фильтр, наливая чай для Алисы.

В эпизоде «Дом Скруджа» Безумному Шляпнику не понравилось, что большой экран заменили маленьким телевизором, но Мартовский Заяц придумал, как исправить положение: выпить уменьшающее зелье, чтобы экран опять казался большим. Когда Скрудж начал экономить на всём подряд и гостям это не понравилось, в клубе остались только Заяц и Шляпник, лишний раз подтвердив, что такой клуб может понравиться только сумасшедшим.

В эпизодах «Микки и волшебное Рождество» и «Микки против Шелби» Шляпник пел песню о том, почему ему нравятся шляпы.

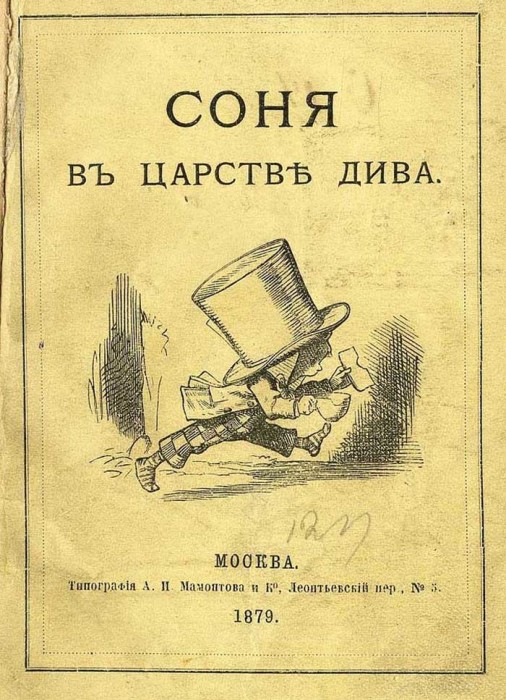

«В маленькой книжке, переполненной орфографическими ошибками и стоящей непомерно дорого, помещён какой-то утомительно скучнейший, путанейший болезненный бред злосчастной девочки Сони; описание бреда лишено и тени художественности; остроумия и какого-нибудь веселья нет и признаков.» — такой отзыв на сказку Льюиса Кэрролла появился в 1879 году в России в журнале «Народная и детская библиотека». В первом переводе на русский язык книга называлась «Соня в царстве дива». Надо сказать, что до сих пор сказка, существенной частью которой являются математические, лингвистические, философские шутки, пародии и аллюзии, не всегда бывает понятна читателям.

Первые отзывы на сказку в Англии тоже были негативными. В рецензии, появившейся в 1865 году, через несколько месяцев после выхода книги, историю охарактеризовали как «неестественную и перегруженную всякими странностями», от которой ребенок будет испытывать скорее недоумение, чем радость. Признание к Кэрроллу пришло только спустя десять лет. Зато с тех пор кажется, что популярность книги растет не переставая. Наверное, сегодня читатели и зрители гораздо больше готовы к восприятию абсурда, чем аккуратные и чопорные жители Англии XIX века. Но, к сожалению, большая часть шуток и пародий нам сегодня уже не очень понятна, так как основывались они на англоязычном материале, а часто и на местных слухах, историях и легендах.

Обложка «Алисы» в первом (анонимном) переводе на русский язык, 1879 год, издательство «А. И. Мамонтов и Ко»

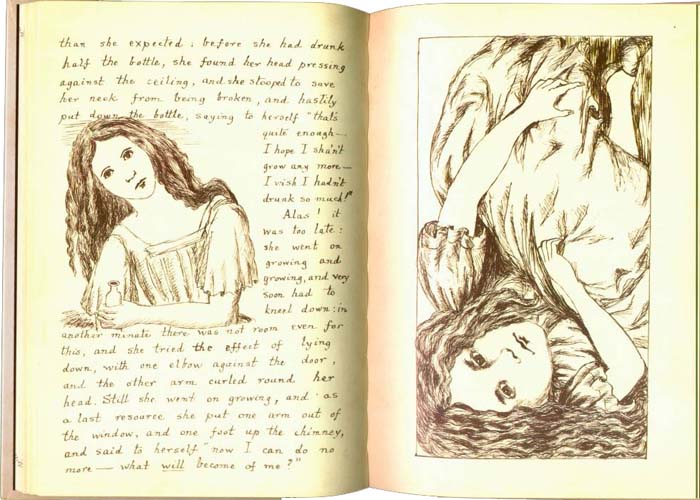

Уже в первой главе, во время длительного полета, скучающая Алиса задает вполне серьезные вопросы, скрытые за детской непосредственностью. Например, коверкая фразу о мышках (мошках) и кошках, она, как считают исследователи, играет в логический позитивизм: «Если некому ответить, то не все ли равно, о чем спрашивать, верно?». А пытаясь вспомнить таблицу умножения, она запутывается: «Значит так: четырежды пять — двенадцать, четырежды шесть — тринадцать, четырежды семь… Так я до двадцати никогда не дойду!». Математики уверены, что их коллега — Чарльз Доджсон, написавший эту сказку под псевдонимом Льюис Кэрролл, просто в данном примере для шутки поменял несколько раз систему счисления. В 18-ричной системе 4 на 5 действительно равняется 12, а в системе счисления с основанием 21, если 4 умножить на 6, то получится 13. Хотя лингвисты отвечают, что если перепутать похожие по звучанию английские слова twenty («двадцать») и twelve («двенадцать»), то получится тот же результат.

Страницы из первой рукописи Льюиса Кэрролла «Приключения Алисы под землей» с иллюстрациями автора

У большинства персонажей, которые встречаются с девочкой в сказочной стране, были в Викторианской Англии реальные прообразы. Это могла быть не обязательно конкретная историческая личность, а какое-нибудь понятие или расхожая шутка. Многие из них были связаны с Оксфордом, который был для Кэрролла важной вехой в жизни.

Шляпник