| Napoleon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries, by Jacques-Louis David, 1812 |

||||

| Emperor of the French

(more…) |

||||

| 1st reign | 18 May 1804 – 6 April 1814 | |||

| Coronation | 2 December 1804 Notre-Dame Cathedral |

|||

| Successor | Louis XVIII (as King of France) |

|||

| 2nd reign | 20 March 1815 – 22 June 1815 | |||

| Predecessor | Louis XVIII | |||

| Successor | Napoleon II (disputed) or Louis XVIII | |||

| King of Italy | ||||

| Reign | 17 March 1805 – 11 April 1814 | |||

| Coronation | 26 May 1805 Milan Cathedral |

|||

| First Consul of France | ||||

| In office 12 December 1799 – 18 May 1804 |

||||

| Co-Consuls | Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès Charles-François Lebrun |

|||

| Provisional Consul of France | ||||

| In office 10 November 1799 – 12 December 1799 |

||||

| Co-Consuls | Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès Roger Ducos |

|||

| President of the Italian Republic | ||||

| In office 26 January 1802 – 17 March 1805 |

||||

| Vice President | Francesco Melzi d’Eril | |||

| Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine | ||||

| In office 12 July 1806 – 4 November 1813 |

||||

| Prince-Primates | Karl von Dalberg Eugène de Beauharnais |

|||

| Born | Napoleone Buonaparte[1] 15 August 1769 Ajaccio, Corsica, Kingdom of France |

|||

| Died | 5 May 1821 (aged 51) Longwood, Saint Helena, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

|||

| Burial | 15 December 1840

Les Invalides, Paris, France |

|||

| Spouse |

Joséphine de Beauharnais (m. ; div. ) Marie Louise of Austria (m. ; separated 1814) |

|||

| Issue Detail |

|

|||

|

||||

| House | Bonaparte | |||

| Father | Carlo Buonaparte | |||

| Mother | Letizia Ramolino | |||

| Signature |

Rescale the fullscreen map to see Saint Helena

Napoleon Bonaparte[a] (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I,[b] was a French military commander and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars. He was the de facto leader of the French Republic as First Consul from 1799 to 1804, then Emperor of the French from 1804 until 1814 and again in 1815. Napoleon’s political and cultural legacy endures to this day, as a highly celebrated and controversial leader. He initiated many liberal reforms that have persisted in society, and is considered one of the greatest military commanders in history. His wars and campaigns are studied by militaries all over the world. Between three and six million civilians and soldiers perished in what became known as the Napoleonic Wars.[2][3]

Napoleon was born on the island of Corsica, not long after its annexation by France, to a native family descending from minor Italian nobility.[4][5] He supported the French Revolution in 1789 while serving in the French army, and tried to spread its ideals to his native Corsica. He rose rapidly in the Army after he saved the governing French Directory by firing on royalist insurgents. In 1796, he began a military campaign against the Austrians and their Italian allies, scoring decisive victories and becoming a national hero. Two years later, he led a military expedition to Egypt that served as a springboard to political power. He engineered a coup in November 1799 and became First Consul of the Republic.

Differences with the United Kingdom meant France faced the War of the Third Coalition by 1805. Napoleon shattered this coalition with victories in the Ulm campaign, and at the Battle of Austerlitz, which led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, the Fourth Coalition took up arms against him. Napoleon defeated Prussia at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt, marched the Grande Armée into Eastern Europe, and defeated the Russians in June 1807 at Friedland, forcing the defeated nations of the Fourth Coalition to accept the Treaties of Tilsit. Two years later, the Austrians challenged the French again during the War of the Fifth Coalition, but Napoleon solidified his grip over Europe after triumphing at the Battle of Wagram.

Hoping to extend the Continental System, his embargo against Britain, Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula and declared his brother Joseph the King of Spain in 1808. The Spanish and the Portuguese revolted in the Peninsular War aided by a British army, culminating in defeat for Napoleon’s marshals. Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia in the summer of 1812. The resulting campaign witnessed the catastrophic retreat of Napoleon’s Grande Armée. In 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a Sixth Coalition against France, resulting in a large coalition army defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig. The coalition invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the island of Elba, between Corsica and Italy. In France, the Bourbons were restored to power.

Napoleon escaped in February 1815 and took control of France.[6] The Allies responded by forming a Seventh Coalition, which defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. The British exiled him to the remote island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic, where he died in 1821 at the age of 51.

Napoleon had an extensive impact on the modern world, bringing liberal reforms to the lands he conquered, especially the regions of the Low Countries, Switzerland and parts of modern Italy and Germany. He implemented many liberal policies in France and Western Europe.[c]

Early life

Napoleon’s family was of Italian origin. His paternal ancestors, the Buonapartes, descended from a minor Tuscan noble family who emigrated to Corsica in the 16th century and his maternal ancestors, the Ramolinos, descended from a minor Genoese noble family.[13] The Buonapartes were also the relatives, by marriage and by birth, of the Pietrasentas, Costas, Paraviccinis, and Bonellis, all Corsican families of the interior.[14] His parents Carlo Maria di Buonaparte and Maria Letizia Ramolino maintained an ancestral home called «Casa Buonaparte» in Ajaccio. Napoleon was born there on 15 August 1769. He was the fourth child and third son of the family.[d] He had an elder brother, Joseph, and younger siblings Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline, and Jérôme. Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic, under the name Napoleone.[15] In his youth, his name was also spelled as Nabulione, Nabulio, Napolionne, and Napulione.[16]

Napoleon was born in the same year that the Republic of Genoa (former Italian state) ceded the region of Corsica to France.[17] The state sold sovereign rights a year before his birth and the island was conquered by France during the year of his birth. It was formally incorporated as a province in 1770, after 500 years under Genoese rule and 14 years of independence.[e] Napoleon’s parents joined the Corsican resistance and fought against the French to maintain independence, even when Maria was pregnant with him. His father Carlo was an attorney who had supported and actively collaborated with patriot Pasquale Paoli during the Corsican war of independence against France;[5] after the Corsican defeat at Ponte Novu in 1769 and Paoli’s exile in Britain, Carlo began working for the new French government and went on to be named representative of the island to the court of Louis XVI in 1777.[5][21]

The dominant influence of Napoleon’s childhood was his mother, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child.[21] Later in life, Napoleon stated, «The future destiny of the child is always the work of the mother.»[22] Napoleon’s maternal grandmother had married into the Swiss Fesch family in her second marriage, and Napoleon’s uncle, the cardinal Joseph Fesch, would fulfill a role as protector of the Bonaparte family for some years. Napoleon’s noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time.[23]

Statue of Napoleon as a schoolboy in Brienne, aged 15, by Louis Rochet [fr] (1853)

When he turned 9 years old,[24][25] he moved to the French mainland and enrolled at a religious school in Autun in January 1779. In May, he transferred with a scholarship to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château.[26] In his youth he was an outspoken Corsican nationalist and supported the state’s independence from France.[24][27] Like many Corsicans, Napoleon spoke and read Corsican (as his mother tongue) and Italian (as the official language of Corsica).[28][29][30][27] He began learning French in school at around age 10.[31] Although he became fluent in French, he spoke with a distinctive Corsican accent and never learned how to spell correctly in French.[32] Consequently, Napoleon was treated unfairly by his schoolmates.[27] He was, however, not an isolated case, as it was estimated in 1790 that fewer than 3 million people, out of France’s population of 28 million, were able to speak standard French, and those who could write it were even fewer.[33]

Napoleon was routinely bullied by his peers for his accent, birthplace, short stature, mannerisms and inability to speak French quickly.[29] He became reserved and melancholy, applying himself to reading. An examiner observed that Napoleon «has always been distinguished for his application in mathematics. He is fairly well acquainted with history and geography … This boy would make an excellent sailor».[f][35]

One story told of Napoleon at the school is that he led junior students to victory against senior students in a snowball fight, showing his leadership abilities.[36] In early adulthood, Napoleon briefly intended to become a writer; he authored a history of Corsica and a romantic novella.[24]

On completion of his studies at Brienne in 1784, Napoleon was admitted to the École Militaire in Paris. He trained to become an artillery officer and, when his father’s death reduced his income, was forced to complete the two-year course in one year.[37] He was the first Corsican to graduate from the École Militaire.[37] He was examined by the famed scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace.[38]

Early career

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment.[g][26] He served in Valence and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. Bonaparte was a fervent Corsican nationalist during this period.[40] He asked for leave to join his mentor Pasquale Paoli, when Paoli was allowed to return to Corsica by the National Assembly. Paoli had no sympathy for Napoleon, however, as he deemed his father a traitor for having deserted his cause for Corsican independence.[41]

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. Napoleon came to embrace the ideals of the Revolution, becoming a supporter of the Jacobins and joining the pro-French Corsican Republicans who opposed Paoli’s policy and his aspirations of secession.[42] He was given command over a battalion of volunteers and was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against French troops.[43]

When Corsica declared formal secession from France and requested the protection of the British government, Napoleon and his commitment to the French Revolution came into conflict with Paoli, who had decided to sabotage the Corsican contribution to the Expédition de Sardaigne, by preventing a French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena.[44] Bonaparte and his family were compelled to flee to Toulon on the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.[45]

Although he was born «Napoleone Buonaparte», it was after this that Napoleon began styling himself «Napoléon Bonaparte». His family did not drop the name Buonaparte until 1796. The first known record of him signing his name as Bonaparte was at the age of 27 (in 1796).[46][15][47]

Siege of Toulon

In July 1793, Bonaparte published a pro-republican pamphlet entitled Le souper de Beaucaire (Supper at Beaucaire) which gained him the support of Augustin Robespierre, the younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. With the help of his fellow Corsican Antoine Christophe Saliceti, Bonaparte was appointed senior gunner and artillery commander of the republican forces which arrived on 8 September at Toulon.[48][49]

He adopted a plan to capture a hill where republican guns could dominate the city’s harbour and force the British to evacuate. The assault on the position led to the capture of the city, and during it Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh on 16 December. Catching the attention of the Committee of Public Safety, he was put in charge of the artillery of France’s Army of Italy.[50] On 22 December he was on his way to his new post in Nice, promoted from the rank of colonel to brigadier general at the age of 24. He devised plans for attacking the Kingdom of Sardinia as part of France’s campaign against the First Coalition.

The French army carried out Bonaparte’s plan in the Battle of Saorgio in April 1794, and then advanced to seize Ormea in the mountains. From Ormea, they headed west to outflank the Austro-Sardinian positions around Saorge. After this campaign, Augustin Robespierre sent Bonaparte on a mission to the Republic of Genoa to determine that country’s intentions towards France.[51]

13 Vendémiaire

Some contemporaries alleged that Bonaparte was put under house arrest at Nice for his association with the Robespierres following their fall in the Thermidorian Reaction in July 1794. Napoleon’s secretary Bourrienne disputed the allegation in his memoirs. According to Bourrienne, jealousy was responsible, between the Army of the Alps and the Army of Italy, with whom Napoleon was seconded at the time.[52] Bonaparte dispatched an impassioned defence in a letter to the commissar Saliceti, and he was acquitted of any wrongdoing.[53] He was released within two weeks (on 20 August) and due to his technical skills, was asked to draw up plans to attack Italian positions in the context of France’s war with Austria. He also took part in an expedition to take back Corsica from the British, but the French were repulsed by the British Royal Navy.[54]

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary, daughter of François Clary. Désirée’s sister Julie Clary had married Bonaparte’s elder brother Joseph.[55] In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée—a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west-central France on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general—for which the army already had a full quota—and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.[56]

He was moved to the Bureau of Topography of the Committee of Public Safety. He sought unsuccessfully to be transferred to Constantinople in order to offer his services to the Sultan.[57] During this period, he wrote the romantic novella Clisson et Eugénie, about a soldier and his lover, in a clear parallel to Bonaparte’s own relationship with Désirée.[58] On 15 September, Bonaparte was removed from the list of generals in regular service for his refusal to serve in the Vendée campaign. He faced a difficult financial situation and reduced career prospects.[59]

On 3 October, royalists in Paris declared a rebellion against the National Convention.[60] Paul Barras, a leader of the Thermidorian Reaction, knew of Bonaparte’s military exploits at Toulon and gave him command of the improvised forces in defence of the convention in the Tuileries Palace. Napoleon had seen the massacre of the King’s Swiss Guard there three years earlier and realized that artillery would be the key to its defence.[26]

He ordered a young cavalry officer named Joachim Murat to seize large cannons and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795—13 Vendémiaire An IV in the French Republican Calendar. 1,400 royalists died and the rest fled.[60] He cleared the streets with «a whiff of grapeshot», according to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.[61][62]

The defeat of the royalist insurrection extinguished the threat to the Convention and earned Bonaparte sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new government, the Directory. Murat married one of Napoleon’s sisters, becoming his brother-in-law; he also served under Napoleon as one of his generals. Bonaparte was promoted to Commander of the Interior and given command of the Army of Italy.[45]

Within weeks, he was romantically involved with Joséphine de Beauharnais, the former mistress of Barras. The couple married on 9 March 1796 in a civil ceremony.[63]

First Italian campaign

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy. He immediately went on the offensive, hoping to defeat the forces of Piedmont before their Austrian allies could intervene. In a series of rapid victories during the Montenotte Campaign, he knocked Piedmont out of the war in two weeks. The French then focused on the Austrians for the remainder of the war, the highlight of which became the protracted struggle for Mantua. The Austrians launched a series of offensives against the French to break the siege, but Napoleon defeated every relief effort, scoring victories at the battles of Castiglione, Bassano, Arcole, and Rivoli. The decisive French triumph at Rivoli in January 1797 led to the collapse of the Austrian position in Italy. At Rivoli, the Austrians lost up to 14,000 men while the French lost about 5,000.[64]

The next phase of the campaign featured the French invasion of the Habsburg heartlands. French forces in Southern Germany had been defeated by the Archduke Charles in 1796, but the Archduke withdrew his forces to protect Vienna after learning about Napoleon’s assault. In the first encounter between the two commanders, Napoleon pushed back his opponent and advanced deep into Austrian territory after winning at the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797. The Austrians were alarmed by the French thrust that reached all the way to Leoben, about 100 km from Vienna, and decided to sue for peace.[65]

The Treaty of Leoben, followed by the more comprehensive Treaty of Campo Formio, gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of Venetian independence. He authorized the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark.[66]

On the journey, Bonaparte conversed much about the warriors of antiquity, especially Alexander, Caesar, Scipio and Hannibal. He studied their strategy and combined it with his own. In a question from Bourrienne, asking whether he gave his preference to Alexander or Caesar, Napoleon said that he places Alexander the Great in the first rank, the main reason being his campaign in Asia.[67]

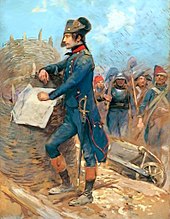

Bonaparte during the Italian campaign in 1797

His application of conventional military ideas to real-world situations enabled his military triumphs, such as creative use of artillery as a mobile force to support his infantry. He stated later in life:[when?] «I have fought sixty battles and I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last».[68]

Bonaparte could win battles by concealment of troop deployments and concentration of his forces on the «hinge» of an enemy’s weakened front. If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two co-operating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other.[69] In this Italian campaign, Bonaparte’s army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons, and 170 standards.[70] The French army fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battles through superior artillery technology and Bonaparte’s tactics.[71]

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France.[72] The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned that he might become a dictator.[73] Napoleon’s forces extracted an estimated $45 million in funds from Italy during their campaign there, another $12 million in precious metals and jewels. His forces confiscated more than 300 priceless paintings and sculptures.[74]

Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau to Paris to lead a coup d’état and purge the royalists on 4 September—the Coup of 18 Fructidor. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent upon Bonaparte, who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio. Bonaparte returned to Paris in December 1797 as a hero.[75] He met Talleyrand, France’s new Foreign Minister—who served in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon—and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.[45]

Egyptian expedition

After two months of planning, Bonaparte decided that France’s naval strength was not yet sufficient to confront the British Royal Navy. He decided on a military expedition to seize Egypt and thereby undermine Britain’s access to its trade interests in India.[45] Bonaparte wished to establish a French presence in the Middle East and join forces with Tipu Sultan, the Sultan of Mysore who was an enemy of the British.[76] Napoleon assured the Directory that «as soon as he had conquered Egypt, he will establish relations with the Indian princes and, together with them, attack the English in their possessions».[77] The Directory agreed in order to secure a trade route to the Indian subcontinent.[78]

In May 1798, Bonaparte was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences. His Egyptian expedition included a group of 167 scientists, with mathematicians, naturalists, chemists, and geodesists among them. Their discoveries included the Rosetta Stone, and their work was published in the Description de l’Égypte in 1809.[79]

En route to Egypt, Bonaparte reached Malta on 9 June 1798, then controlled by the Knights Hospitaller. Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim surrendered after token resistance, and Bonaparte captured an important naval base with the loss of only three men.[80]

Bonaparte and his expedition eluded pursuit by the Royal Navy and landed at Alexandria on 1 July.[45] He fought the Battle of Shubra Khit against the Mamluks, Egypt’s ruling military caste. This helped the French practise their defensive tactic for the Battle of the Pyramids, fought on 21 July, about 24 km (15 mi) from the pyramids. General Bonaparte’s forces of 25,000 roughly equalled those of the Mamluks’ Egyptian cavalry. Twenty-nine French[81] and approximately 2,000 Egyptians were killed. The victory boosted the morale of the French army.[82]

On 1 August 1798, the British fleet under Sir Horatio Nelson captured or destroyed all but two vessels of the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile, defeating Bonaparte’s goal to strengthen the French position in the Mediterranean.[83] His army had succeeded in a temporary increase of French power in Egypt, though it faced repeated uprisings.[84] In early 1799, he moved an army into the Ottoman province of Damascus (Syria and Galilee). Bonaparte led these 13,000 French soldiers in the conquest of the coastal towns of Arish, Gaza, Jaffa, and Haifa.[85] The attack on Jaffa was particularly brutal. Bonaparte discovered that many of the defenders were former prisoners of war, ostensibly on parole, so he ordered the garrison and some 1,500–2,000 prisoners to be executed by bayonet or drowning.[86] Men, women, and children were robbed and murdered for three days.[87]

Bonaparte began with an army of 13,000 men. 1,500 were reported missing, 1,200 died in combat, and thousands perished from disease—mostly bubonic plague. He failed to reduce the fortress of Acre, so he marched his army back to Egypt in May. To speed up the retreat, Bonaparte ordered plague-stricken men to be poisoned with opium. The number who died remains disputed, ranging from a low of 30 to a high of 580. He also brought out 1,000 wounded men.[88] Back in Egypt on 25 July, Bonaparte defeated an Ottoman amphibious invasion at Abukir.[89]

Ruler of France

General Bonaparte surrounded by members of the Council of Five Hundred during the Coup of 18 Brumaire, by François Bouchot

While in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs. He learned that France had suffered a series of defeats in the War of the Second Coalition.[90] On 24 August 1799, fearing that the Republic’s future was in doubt, he took advantage of the temporary departure of British ships from French coastal ports and set sail for France, despite the fact that he had received no explicit orders from Paris.[91] The army was left in the charge of Jean-Baptiste Kléber.[92]

Unknown to Bonaparte, the Directory had sent him orders to return to ward off possible invasions of French soil, but poor lines of communication prevented the delivery of these messages.[90] By the time that he reached Paris in October, France’s situation had been improved by a series of victories. The Republic, however, was bankrupt and the ineffective Directory was unpopular with the French population.[93] The Directory discussed Bonaparte’s «desertion» but was too weak to punish him.[90]

Despite the failures in Egypt, Napoleon returned to a hero’s welcome. He drew together an alliance with director Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, his brother Lucien, speaker of the Council of Five Hundred Roger Ducos, director Joseph Fouché, and Talleyrand, and they overthrew the Directory by a coup d’état on 9 November 1799 («the 18th Brumaire» according to the revolutionary calendar), closing down the Council of Five Hundred. Napoleon became «first consul» for ten years, with two consuls appointed by him who had consultative voices only. His power was confirmed by the new «Constitution of the Year VIII», originally devised by Sieyès to give Napoleon a minor role, but rewritten by Napoleon, and accepted by direct popular vote (3,000,000 in favour, 1,567 opposed). The constitution preserved the appearance of a republic but, in reality, established a dictatorship.[94][95]

French Consulate

Napoleon established a political system that historian Martyn Lyons called «dictatorship by plebiscite».[96] Worried by the democratic forces unleashed by the Revolution, but unwilling to ignore them entirely, Napoleon resorted to regular electoral consultations with the French people on his road to imperial power.[96] He drafted the Constitution of the Year VIII and secured his own election as First Consul, taking up residence at the Tuileries. The constitution was approved in a rigged plebiscite held the following January, with 99.94 percent officially listed as voting «yes».[97]

Napoleon’s brother, Lucien, had falsified the returns to show that 3 million people had participated in the plebiscite. The real number was 1.5 million.[96] Political observers at the time assumed the eligible French voting public numbered about 5 million people, so the regime artificially doubled the participation rate to indicate popular enthusiasm for the consulate.[96] In the first few months of the consulate, with war in Europe still raging and internal instability still plaguing the country, Napoleon’s grip on power remained very tenuous.[98]

In the spring of 1800, Napoleon and his troops crossed the Swiss Alps into Italy, aiming to surprise the Austrian armies that had reoccupied the peninsula when Napoleon was still in Egypt.[h] After a difficult crossing over the Alps, the French army entered the plains of Northern Italy virtually unopposed.[100] While one French army approached from the north, the Austrians were busy with another stationed in Genoa, which was besieged by a substantial force. The fierce resistance of this French army, under André Masséna, gave the northern force some time to carry out their operations with little interference.[101]

After spending several days looking for each other, the two armies collided at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June. General Melas had a numerical advantage, fielding about 30,000 Austrian soldiers while Napoleon commanded 24,000 French troops.[102] The battle began favourably for the Austrians as their initial attack surprised the French and gradually drove them back. Melas stated that he had won the battle and retired to his headquarters around 3 pm, leaving his subordinates in charge of pursuing the French.[103] The French lines never broke during their tactical retreat. Napoleon constantly rode out among the troops urging them to stand and fight.[104]

Late in the afternoon, a full division under Desaix arrived on the field and reversed the tide of the battle. A series of artillery barrages and cavalry charges decimated the Austrian army, which fled over the Bormida River back to Alessandria, leaving behind 14,000 casualties.[104] The following day, the Austrian army agreed to abandon Northern Italy once more with the Convention of Alessandria, which granted them safe passage to friendly soil in exchange for their fortresses throughout the region.[104]

Although critics have blamed Napoleon for several tactical mistakes preceding the battle, they have also praised his audacity for selecting a risky campaign strategy, choosing to invade the Italian peninsula from the north when the vast majority of French invasions came from the west, near or along the coastline.[105] As David G. Chandler points out, Napoleon spent almost a year getting the Austrians out of Italy in his first campaign. In 1800, it took him only a month to achieve the same goal.[105] German strategist and field marshal Alfred von Schlieffen concluded that «Bonaparte did not annihilate his enemy but eliminated him and rendered him harmless» while attaining «the object of the campaign: the conquest of North Italy».[106]

Napoleon’s triumph at Marengo secured his political authority and boosted his popularity back home, but it did not lead to an immediate peace. Bonaparte’s brother, Joseph, led the complex negotiations in Lunéville and reported that Austria, emboldened by British support, would not acknowledge the new territory that France had acquired. As negotiations became increasingly fractious, Bonaparte gave orders to his general Moreau to strike Austria once more. Moreau and the French swept through Bavaria and scored an overwhelming victory at Hohenlinden in December 1800. As a result, the Austrians capitulated and signed the Treaty of Lunéville in February 1801. The treaty reaffirmed and expanded earlier French gains at Campo Formio.[107]

Temporary peace in Europe

After a decade of constant warfare, France and Britain signed the Treaty of Amiens in March 1802, bringing the Revolutionary Wars to an end. Amiens called for the withdrawal of British troops from recently conquered colonial territories as well as for assurances to curtail the expansionary goals of the French Republic.[101] With Europe at peace and the economy recovering, Napoleon’s popularity soared to its highest levels under the consulate, both domestically and abroad.[108] In a new plebiscite during the spring of 1802, the French public came out in huge numbers to approve a constitution that made the Consulate permanent, essentially elevating Napoleon to dictator for life.[108]

Whereas the plebiscite two years earlier had brought out 1.5 million people to the polls, the new referendum enticed 3.6 million to go and vote (72 percent of all eligible voters).[109] There was no secret ballot in 1802 and few people wanted to openly defy the regime. The constitution gained approval with over 99% of the vote.[109] His broad powers were spelled out in the new constitution: Article 1. The French people name, and the Senate proclaims Napoleon-Bonaparte First Consul for Life.[110] After 1802, he was generally referred to as Napoleon rather than Bonaparte.[39]

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase totalled 2,144,480 square kilometres (827,987 square miles), doubling the size of the United States.

The brief peace in Europe allowed Napoleon to focus on French colonies abroad. Saint-Domingue had managed to acquire a high level of political autonomy during the Revolutionary Wars, with Toussaint L’Ouverture installing himself as de facto dictator by 1801. Napoleon saw a chance to reestablish control over the colony when he signed the Treaty of Amiens. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue had been France’s most profitable colony, producing more sugar than all the British West Indies colonies combined. However, during the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794.[111] Aware of the expenses required to fund his wars in Europe, Napoleon made the decision to reinstate slavery in all French Caribbean colonies. The 1794 decree had only affected the colonies of Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and Guiana, and did not take effect in Mauritius, Reunion and Martinique, the last of which had been captured by the British and as such remained unaffected by French law.[112]

In Guadeloupe slavery had been abolished (and its ban violently enforced) by Victor Hugues against opposition from slaveholders thanks to the 1794 law. However, when slavery was reinstated in 1802, a slave revolt broke out under the leadership of Louis Delgrès.[113] The resulting Law of 20 May had the express purpose of reinstating slavery in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and French Guiana, and restored slavery throughout most of the French colonial empire (excluding Saint-Domingue) for another half a century, while the French transatlantic slave trade continued for another twenty years.[114][115][116][117][118]

Napoleon sent an expedition under his brother-in-law General Leclerc to reassert control over Saint-Domingue. Although the French managed to capture Toussaint Louverture, the expedition failed when high rates of disease crippled the French army, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines won a string of victories, first against Leclerc, and when he died from yellow fever, then against Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau, whom Napoleon sent to relieve Leclerc with another 20,000 men. In May 1803, Napoleon acknowledged defeat, and the last 8,000 French troops left the island and the slaves proclaimed an independent republic that they called Haiti in 1804. In the process, Dessalines became arguably the most successful military commander in the struggle against Napoleonic France.[119][120] Seeing the failure of his efforts in Haiti, Napoleon decided in 1803 to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States, instantly doubling the size of the U.S. The selling price in the Louisiana Purchase was less than three cents per acre, a total of $15 million.[2][121]

The peace with Britain proved to be uneasy and controversial.[122] Britain did not evacuate Malta as promised and protested against Bonaparte’s annexation of Piedmont and his Act of Mediation, which established a new Swiss Confederation. Neither of these territories were covered by Amiens, but they inflamed tensions significantly.[123] The dispute culminated in a declaration of war by Britain in May 1803; Napoleon responded by reassembling the invasion camp at Boulogne and declaring that every British male between eighteen and sixty years old in France and its dependencies to be arrested as a prisoner of war.[124]

French Empire

During the consulate, Napoleon faced several royalist and Jacobin assassination plots, including the Conspiration des poignards (Dagger plot) in October 1800 and the Plot of the Rue Saint-Nicaise (also known as the Infernal Machine) two months later.[125] In January 1804, his police uncovered an assassination plot against him that involved Moreau and which was ostensibly sponsored by the Bourbon family, the former rulers of France. On the advice of Talleyrand, Napoleon ordered the kidnapping of the Duke of Enghien, violating the sovereignty of Baden. The Duke was quickly executed after a secret military trial, even though he had not been involved in the plot.[126] Enghien’s execution infuriated royal courts throughout Europe, becoming one of the contributing political factors for the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars.

To expand his power, Napoleon used these assassination plots to justify the creation of an imperial system based on the Roman model. He believed that a Bourbon restoration would be more difficult if his family’s succession was entrenched in the constitution.[127] Launching yet another referendum, Napoleon was elected as Emperor of the French by a tally exceeding 99%.[109] As with the Life Consulate two years earlier, this referendum produced heavy participation, bringing out almost 3.6 million voters to the polls.[109]

A keen observer of Bonaparte’s rise to absolute power, Madame de Rémusat, explains that «men worn out by the turmoil of the Revolution […] looked for the domination of an able ruler» and that «people believed quite sincerely that Bonaparte, whether as consul or emperor, would exert his authority and save [them] from the perils of anarchy.»[128]»

Napoleon’s throne room at Fontainebleau

Napoleon’s coronation, at which Pope Pius VII officiated, took place at Notre Dame de Paris, on 2 December 1804. Two separate crowns were brought for the ceremony: a golden laurel wreath recalling the Roman Empire, and a replica of Charlemagne’s crown.[129] Napoleon entered the ceremony wearing the laurel wreath and kept it on his head throughout the proceedings.[129] For the official coronation, he raised the Charlemagne crown over his own head in a symbolic gesture, but never placed it on top because he was already wearing the golden wreath.[129] Instead he placed the crown on Josephine’s head, the event commemorated in the officially sanctioned painting by Jacques-Louis David.[129] Napoleon was crowned King of Italy, with the Iron Crown of Lombardy, at the Cathedral of Milan on 26 May 1805. He created eighteen Marshals of the Empire from among his top generals to secure the allegiance of the army on 18 May 1804, the official start of the Empire.[130]

War of the Third Coalition

Great Britain had broken the Peace of Amiens by declaring war on France in May 1803.[131] In December 1804, an Anglo-Swedish agreement became the first step towards the creation of the Third Coalition. By April 1805, Britain had also signed an alliance with Russia.[132] Austria had been defeated by France twice in recent memory and wanted revenge, so it joined the coalition a few months later.[133]

Before the formation of the Third Coalition, Napoleon had assembled an invasion force, the Armée d’Angleterre, around six camps at Boulogne in Northern France. He intended to use this invasion force to strike at England. They never invaded, but Napoleon’s troops received careful and invaluable training for future military operations.[134] The men at Boulogne formed the core for what Napoleon later called La Grande Armée. At the start, this French army had about 200,000 men organized into seven corps, which were large field units that contained 36–40 cannons each and were capable of independent action until other corps could come to the rescue.[135]

A single corps properly situated in a strong defensive position could survive at least a day without support, giving the Grande Armée countless strategic and tactical options on every campaign. On top of these forces, Napoleon created a cavalry reserve of 22,000 organized into two cuirassier divisions, four mounted dragoon divisions, one division of dismounted dragoons, and one of light cavalry, all supported by 24 artillery pieces.[136] By 1805, the Grande Armée had grown to a force of 350,000 men,[136] who were well equipped, well trained, and led by competent officers.[137]

Napoleon knew that the French fleet could not defeat the Royal Navy in a head-to-head battle, so he planned to lure it away from the English Channel through diversionary tactics.[138] The main strategic idea involved the French Navy escaping from the British blockades of Toulon and Brest and threatening to attack the British West Indies. In the face of this attack, it was hoped, the British would weaken their defence of the Western Approaches by sending ships to the Caribbean, allowing a combined Franco-Spanish fleet to take control of the English channel long enough for French armies to cross and invade.[138] However, the plan unravelled after the British victory at the Battle of Cape Finisterre in July 1805. French Admiral Villeneuve then retreated to Cádiz instead of linking up with French naval forces at Brest for an attack on the English Channel.[139]

By August 1805, Napoleon had realized that the strategic situation had changed fundamentally. Facing a potential invasion from his continental enemies, he decided to strike first and turned his army’s sights from the English Channel to the Rhine. His basic objective was to destroy the isolated Austrian armies in Southern Germany before their Russian allies could arrive. On 25 September, after great secrecy and feverish marching, 200,000 French troops began to cross the Rhine on a front of 260 km (160 mi).[140][141]

Austrian commander Karl Mack had gathered the greater part of the Austrian army at the fortress of Ulm in Swabia. Napoleon swung his forces to the southeast and the Grande Armée performed an elaborate wheeling movement that outflanked the Austrian positions. The Ulm Maneuver completely surprised General Mack, who belatedly understood that his army had been cut off. After some minor engagements that culminated in the Battle of Ulm, Mack finally surrendered after realizing that there was no way to break out of the French encirclement. For just 2,000 French casualties, Napoleon had managed to capture a total of 60,000 Austrian soldiers through his army’s rapid marching.[142] Napoleon wrote after the conflict:

«I have accomplished my object, I have destroyed the Austrian army by simply marching.»[143]

The Ulm Campaign is generally regarded as a strategic masterpiece and was influential in the development of the Schlieffen Plan in the late 19th century.[144] For the French, this spectacular victory on land was soured by the decisive victory that the Royal Navy attained at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October. After Trafalgar, the Royal Navy was never again seriously challenged by a French fleet in a large-scale engagement for the duration of the Napoleonic Wars.[145]

Following the Ulm Campaign, French forces managed to capture Vienna in November. The fall of Vienna provided the French a huge bounty as they captured 100,000 muskets, 500 cannons, and the intact bridges across the Danube.[146] At this critical juncture, both Tsar Alexander I and Holy Roman Emperor Francis II decided to engage Napoleon in battle, despite reservations from some of their subordinates. Napoleon sent his army north in pursuit of the Allies but then ordered his forces to retreat so that he could feign a grave weakness.[147]

Desperate to lure the Allies into battle, Napoleon gave every indication in the days preceding the engagement that the French army was in a pitiful state, even abandoning the dominant Pratzen Heights, a sloping hill near the village of Austerlitz. At the Battle of Austerlitz, in Moravia on 2 December, he deployed the French army below the Pratzen Heights and deliberately weakened his right flank, enticing the Allies to launch a major assault there in the hopes of rolling up the whole French line. A forced march from Vienna by Marshal Davout and his III Corps plugged the gap left by Napoleon just in time.[147]

Meanwhile, the heavy Allied deployment against the French right flank weakened their center on the Pratzen Heights, which was viciously attacked by the IV Corps of Marshal Soult. With the Allied center demolished, the French swept through both enemy flanks and sent the Allies fleeing chaotically, capturing thousands of prisoners in the process. The battle is often seen as a tactical masterpiece because of the near-perfect execution of a calibrated but dangerous plan—of the same stature as Cannae, the celebrated triumph by Hannibal some 2,000 years before.[147]

The Allied disaster at Austerlitz significantly shook the faith of Emperor Francis in the British-led war effort. France and Austria agreed to an armistice immediately and the Treaty of Pressburg followed shortly after on 26 December. Pressburg took Austria out of both the war and the Coalition while reinforcing the earlier treaties of Campo Formio and of Lunéville between the two powers. The treaty confirmed the Austrian loss of lands to France in Italy and Bavaria, and lands in Germany to Napoleon’s German allies.[148]

It imposed an indemnity of 40 million francs on the defeated Habsburgs and allowed the fleeing Russian troops free passage through hostile territories and back to their home soil. Napoleon went on to say, «The battle of Austerlitz is the finest of all I have fought».[149] Frank McLynn suggests that Napoleon was so successful at Austerlitz that he lost touch with reality, and what used to be French foreign policy became a «personal Napoleonic one».[150] Vincent Cronin disagrees, stating that Napoleon was not overly ambitious for himself, «he embodied the ambitions of thirty million Frenchmen».[151]

Middle-Eastern alliances

Napoleon continued to entertain a grand scheme to establish a French presence in the Middle East in order to put pressure on Britain and Russia, and perhaps form an alliance with the Ottoman Empire.[76] In February 1806, Ottoman Emperor Selim III recognised Napoleon as Emperor. He also opted for an alliance with France, calling France «our sincere and natural ally».[152] That decision brought the Ottoman Empire into a losing war against Russia and Britain. A Franco-Persian alliance was formed between Napoleon and the Persian Empire of Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar. It collapsed in 1807 when France and Russia formed an unexpected alliance.[76] In the end, Napoleon had made no effective alliances in the Middle East.[153]

War of the Fourth Coalition and Tilsit

After Austerlitz, Napoleon established the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806. A collection of German states intended to serve as a buffer zone between France and Central Europe, the creation of the Confederation spelled the end of the Holy Roman Empire and significantly alarmed the Prussians. The brazen reorganization of German territory by the French risked threatening Prussian influence in the region, if not eliminating it outright. War fever in Berlin rose steadily throughout the summer of 1806. At the insistence of his court, especially his wife Queen Louise, Frederick William III decided to challenge the French domination of Central Europe by going to war.[154]

The initial military manoeuvres began in September 1806. In a letter to Marshal Soult detailing the plan for the campaign, Napoleon described the essential features of Napoleonic warfare and introduced the phrase le bataillon-carré («square battalion»).[155] In the bataillon-carré system, the various corps of the Grande Armée would march uniformly together in close supporting distance.[155] If any single corps was attacked, the others could quickly spring into action and arrive to help.[156]

Napoleon invaded Prussia with 180,000 troops, rapidly marching on the right bank of the River Saale. As in previous campaigns, his fundamental objective was to destroy one opponent before reinforcements from another could tip the balance of the war. Upon learning the whereabouts of the Prussian army, the French swung westwards and crossed the Saale with overwhelming force. At the twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt, fought on 14 October, the French convincingly defeated the Prussians and inflicted heavy casualties. With several major commanders dead or incapacitated, the Prussian king proved incapable of effectively commanding the army, which began to quickly disintegrate.[156]

In a vaunted pursuit that epitomized the «peak of Napoleonic warfare», according to historian Richard Brooks,[156] the French managed to capture 140,000 soldiers, over 2,000 cannons and hundreds of ammunition wagons, all in a single month. Historian David Chandler wrote of the Prussian forces: «Never has the morale of any army been more completely shattered».[155] Despite their overwhelming defeat, the Prussians refused to negotiate with the French until the Russians had an opportunity to enter the fight.

Following his triumph, Napoleon imposed the first elements of the Continental System through the Berlin Decree issued in November 1806. The Continental System, which prohibited European nations from trading with Britain, was widely violated throughout his reign.[157][158] In the next few months, Napoleon marched against the advancing Russian armies through Poland and was involved in the bloody stalemate at the Battle of Eylau in February 1807.[159] After a period of rest and consolidation on both sides, the war restarted in June with an initial struggle at Heilsberg that proved indecisive.[160]

On 14 June Napoleon obtained an overwhelming victory over the Russians at the Battle of Friedland, wiping out the majority of the Russian army in a very bloody struggle. The scale of their defeat convinced the Russians to make peace with the French. On 19 June, Tsar Alexander sent an envoy to seek an armistice with Napoleon. The latter assured the envoy that the Vistula River represented the natural borders between French and Russian influence in Europe. On that basis, the two emperors began peace negotiations at the town of Tilsit after meeting on an iconic raft on the River Niemen. The very first thing Alexander said to Napoleon was probably well-calibrated: «I hate the English as much as you do».[160] Their meeting lasted two hours. Despite waging wars against each other the two Emperors were very much impressed and fascinated by one another. “Never,” said Alexander afterward, “did I love any man as I loved that man.”[161]

Alexander faced pressure from his brother, Duke Constantine, to make peace with Napoleon. Given the victory he had just achieved, the French emperor offered the Russians relatively lenient terms—demanding that Russia join the Continental System, withdraw its forces from Wallachia and Moldavia, and hand over the Ionian Islands to France.[162] By contrast, Napoleon dictated very harsh peace terms for Prussia, despite the ceaseless exhortations of Queen Louise. Wiping out half of Prussian territories from the map, Napoleon created a new kingdom of 2,800 square kilometres (1,100 sq mi) called Westphalia and appointed his young brother Jérôme as its monarch.[163]

Prussia’s humiliating treatment at Tilsit caused a deep and bitter antagonism that festered as the Napoleonic era progressed. Moreover, Alexander’s pretensions at friendship with Napoleon led the latter to seriously misjudge the true intentions of his Russian counterpart, who would violate numerous provisions of the treaty in the next few years. Despite these problems, the Treaties of Tilsit at last gave Napoleon a respite from war and allowed him to return to France, which he had not seen in over 300 days.[163]

Peninsular War and Erfurt

The settlements at Tilsit gave Napoleon time to organize his empire. One of his major objectives became enforcing the Continental System against the British forces. He decided to focus his attention on the Kingdom of Portugal, which consistently violated his trade prohibitions. After defeat in the War of the Oranges in 1801, Portugal adopted a double-sided policy.

Unhappy with this change of policy by the Portuguese government, Napoleon negotiated a secret treaty with Charles IV of Spain and sent an army to invade Portugal.[164] On 17 October 1807, 24,000 French troops under General Junot crossed the Pyrenees with Spanish cooperation and headed towards Portugal to enforce Napoleon’s orders.[165] This attack was the first step in what would eventually become the Peninsular War, a six-year struggle that significantly sapped French strength. Throughout the winter of 1808, French agents became increasingly involved in Spanish internal affairs, attempting to incite discord between members of the Spanish royal family. On 16 February 1808, secret French machinations finally materialized when Napoleon announced that he would intervene to mediate between the rival political factions in the country.[166]

Marshal Murat led 120,000 troops into Spain. The French arrived in Madrid on 24 March,[167] where wild riots against the occupation erupted just a few weeks later. Napoleon appointed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as the new King of Spain in the summer of 1808. The appointment enraged a heavily religious and conservative Spanish population. Resistance to French aggression soon spread throughout Spain. The shocking French defeats at the Battle of Bailén and the Battle of Vimiero gave hope to Napoleon’s enemies and partly persuaded the French emperor to intervene in person.[168]

Before going to Iberia, Napoleon decided to address several lingering issues with the Russians. At the Congress of Erfurt in October 1808, Napoleon hoped to keep Russia on his side during the upcoming struggle in Spain and during any potential conflict against Austria. The two sides reached an agreement, the Erfurt Convention, that called upon Britain to cease its war against France, that recognized the Russian conquest of Finland from Sweden and made it an autonomous Grand Duchy,[169] and that affirmed Russian support for France in a possible war against Austria «to the best of its ability».[170]

Napoleon then returned to France and prepared for war. The Grande Armée, under the Emperor’s personal command, rapidly crossed the Ebro River in November 1808 and inflicted a series of crushing defeats against the Spanish forces. After clearing the last Spanish force guarding the capital at Somosierra, Napoleon entered Madrid on 4 December with 80,000 troops.[171] He then unleashed his soldiers against Moore and the British forces. The British were swiftly driven to the coast, and they withdrew from Spain entirely after a last stand at the Battle of Corunna in January 1809 and the death of Moore.[172]

Napoleon accepting the surrender of Madrid, 4 December 1808

Napoleon would end up leaving Iberia in order to deal with the Austrians in Central Europe, but the Peninsular War continued on long after his absence. He never returned to Spain after the 1808 campaign. Several months after Corunna, the British sent another army to the peninsula under Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. The war then settled into a complex and asymmetric strategic deadlock where all sides struggled to gain the upper hand. The highlight of the conflict became the brutal guerrilla warfare that engulfed much of the Spanish countryside. Both sides committed the worst atrocities of the Napoleonic Wars during this phase of the conflict.[173]

The vicious guerrilla fighting in Spain, largely absent from the French campaigns in Central Europe, severely disrupted the French lines of supply and communication. Although France maintained roughly 300,000 troops in Iberia during the Peninsular War, the vast majority were tied down to garrison duty and to intelligence operations.[173] The French were never able to concentrate all of their forces effectively, prolonging the war until events elsewhere in Europe finally turned the tide in favour of the Allies. After the invasion of Russia in 1812, the number of French troops in Spain vastly declined as Napoleon needed reinforcements to conserve his strategic position in Europe. By 1814 the Allies had pushed the French out of the peninsula.

The impact of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain and ousting of the Spanish Bourbon monarchy in favour of his brother Joseph had an enormous impact on the Spanish empire. In Spanish America many local elites formed juntas and set up mechanisms to rule in the name of Ferdinand VII of Spain, whom they considered the legitimate Spanish monarch. The outbreak of the Spanish American wars of independence in most of the empire was a result of Napoleon’s destabilizing actions in Spain and led to the rise of strongmen in the wake of these wars.[174]

War of the Fifth Coalition and Marie Louise

After four years on the sidelines, Austria sought another war with France to avenge its recent defeats. Austria could not count on Russian support because the latter was at war with Britain, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire in 1809. Frederick William of Prussia initially promised to help the Austrians but reneged before conflict began.[175] A report from the Austrian finance minister suggested that the treasury would run out of money by the middle of 1809 if the large army that the Austrians had formed since the Third Coalition remained mobilized.[175] Although Archduke Charles warned that the Austrians were not ready for another showdown with Napoleon, a stance that landed him in the so-called «peace party», he did not want to see the army demobilized either.[175] On 8 February 1809, the advocates for war finally succeeded when the Imperial Government secretly decided on another confrontation against the French.[176]

In the early morning of 10 April, leading elements of the Austrian army crossed the Inn River and invaded Bavaria. The early Austrian attack surprised the French; Napoleon himself was still in Paris when he heard about the invasion. He arrived at Donauwörth on the 17th to find the Grande Armée in a dangerous position, with its two wings separated by 120 km (75 mi) and joined by a thin cordon of Bavarian troops. Charles pressed the left wing of the French army and hurled his men towards the III Corps of Marshal Davout.[177]

In response, Napoleon came up with a plan to cut off the Austrians in the celebrated Landshut Maneuver.[178] He realigned the axis of his army and marched his soldiers towards the town of Eckmühl. The French scored a convincing win in the resulting Battle of Eckmühl, forcing Charles to withdraw his forces over the Danube and into Bohemia. On 13 May, Vienna fell for the second time in four years, although the war continued since most of the Austrian army had survived the initial engagements in Southern Germany.

On 21 May, the French made their first major effort to cross the Danube, precipitating the Battle of Aspern-Essling. The battle was characterized by a vicious back-and-forth struggle for the two villages of Aspern and Essling, the focal points of the French bridgehead. A sustained Austrian artillery bombardment eventually convinced Napoleon to withdraw his forces back onto Lobau Island. Both sides inflicted about 23,000 casualties on each other.[179] It was the first defeat Napoleon suffered in a major set-piece battle, and it caused excitement throughout many parts of Europe because it proved that he could be beaten on the battlefield.[180]

After the setback at Aspern-Essling, Napoleon took more than six weeks in planning and preparing for contingencies before he made another attempt at crossing the Danube.[181] From 30 June to the early days of July, the French recrossed the Danube in strength, with more than 180,000 troops marching across the Marchfeld towards the Austrians.[181] Charles received the French with 150,000 of his own men.[182] In the ensuing Battle of Wagram, which also lasted two days, Napoleon commanded his forces in what was the largest battle of his career up until then. Napoleon finished off the battle with a concentrated central thrust that punctured a hole in the Austrian army and forced Charles to retreat. Austrian losses were very heavy, reaching well over 40,000 casualties.[183] The French were too exhausted to pursue the Austrians immediately, but Napoleon eventually caught up with Charles at Znaim and the latter signed an armistice on 12 July.

In the Kingdom of Holland, the British launched the Walcheren Campaign to open up a second front in the war and to relieve the pressure on the Austrians. The British army only landed at Walcheren on 30 July, by which point the Austrians had already been defeated. The Walcheren Campaign was characterized by little fighting but heavy casualties thanks to the popularly dubbed «Walcheren Fever». Over 4,000 British troops were lost in a bungled campaign, and the rest withdrew in December 1809.[184] The main strategic result from the campaign became the delayed political settlement between the French and the Austrians. Emperor Francis waited to see how the British performed in their theatre before entering into negotiations with Napoleon. Once it became apparent the British were going nowhere, the Austrians agreed to peace talks.[citation needed]

The resulting Treaty of Schönbrunn in October 1809 was the harshest that France had imposed on Austria in recent memory. Metternich and Archduke Charles had the preservation of the Habsburg Empire as their fundamental goal, and to this end, they succeeded by making Napoleon seek more modest goals in return for promises of friendship between the two powers.[185] While most of the hereditary lands remained a part of the Habsburg realm, France received Carinthia, Carniola, and the Adriatic ports, while Galicia was given to the Poles and the Salzburg area of the Tyrol went to the Bavarians.[185] Austria lost over three million subjects, about one-fifth of her total population, as a result of these territorial changes.[186]

Napoleon turned his focus to domestic affairs after the war. Empress Joséphine had still not given birth to a child from Napoleon, who became worried about the future of his empire following his death. Desperate for a legitimate heir, Napoleon divorced Joséphine on 10 January 1810 and started looking for a new wife. Hoping to cement the recent alliance with Austria through a family connection, Napoleon married the 18-year-old Archduchess Marie Louise, daughter of Emperor Francis II. On 20 March 1811, Marie Louise gave birth to a baby boy, whom Napoleon made heir apparent and bestowed the title of King of Rome. His son never actually ruled the empire, but given his brief titular rule and cousin Louis-Napoléon’s subsequent naming himself Napoléon III, historians often refer to him as Napoleon II.[187]

Invasion of Russia

In 1808, Napoleon and Tsar Alexander met at the Congress of Erfurt to preserve the Russo-French alliance. The leaders had a friendly personal relationship after their first meeting at Tilsit in 1807.[188] By 1811, however, tensions had increased, a strain on the relationship became the regular violations of the Continental System by the Russians as their economy was failing, which led Napoleon to threaten Alexander with serious consequences if he formed an alliance with Britain.[189]

By 1812, advisers to Alexander suggested the possibility of an invasion of the French Empire and the recapture of Poland. On receipt of intelligence reports on Russia’s war preparations, Napoleon expanded his Grande Armée to more than 450,000 men.[190] He ignored repeated advice against an invasion of the Russian heartland and prepared for an offensive campaign; on 24 June 1812 the invasion commenced.[191]

In an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and patriots, Napoleon termed the war the Second Polish War—the First Polish War had been the Bar Confederation uprising by Polish nobles against Russia in 1768. Polish patriots wanted the Russian part of Poland to be joined with the Duchy of Warsaw and an independent Poland created. This was rejected by Napoleon, who stated he had promised his ally Austria this would not happen. Napoleon refused to manumit the Russian serfs because of concerns this might provoke a reaction in his army’s rear. The serfs later committed atrocities against French soldiers during France’s retreat.[192]

The Russians avoided Napoleon’s objective of a decisive engagement and instead retreated deeper into Russia. A brief attempt at resistance was made at Smolensk in August; the Russians were defeated in a series of battles, and Napoleon resumed his advance. The Russians again avoided battle, although in a few cases this was only achieved because Napoleon uncharacteristically hesitated to attack when the opportunity arose. Owing to the Russian army’s scorched earth tactics, the French found it increasingly difficult to forage food for themselves and their horses.[193]

The Russians eventually offered battle outside Moscow on 7 September: the Battle of Borodino resulted in approximately 44,000 Russian and 35,000 French dead, wounded or captured, and may have been the bloodiest day of battle in history up to that point in time.[194] Although the French had won, the Russian army had accepted, and withstood, the major battle Napoleon had hoped would be decisive. Napoleon’s own account was: «The most terrible of all my battles was the one before Moscow. The French showed themselves to be worthy of victory, but the Russians showed themselves worthy of being invincible».[195]

The Russian army withdrew and retreated past Moscow. Napoleon entered the city, assuming its fall would end the war and Alexander would negotiate peace. Moscow was burned, rather than surrendered, on the order of Moscow’s governor Feodor Rostopchin. After five weeks, Napoleon and his army left. In early November Napoleon became concerned about the loss of control back in France after the Malet coup of 1812. His army walked through snow up to their knees, and nearly 10,000 men and horses froze to death on the night of 8/9 November alone. After the Battle of Berezina Napoleon managed to escape but had to abandon much of the remaining artillery and baggage train. On 5 December, shortly before arriving in Vilnius, Napoleon left the army in a sledge.[196]

The French suffered in the course of a ruinous retreat, including from the harshness of the Russian Winter. The Armée had begun as over 400,000 frontline troops, with fewer than 40,000 crossing the Berezina River in November 1812.[197] The Russians had lost 150,000 soldiers in battle and hundreds of thousands of civilians.[198]

War of the Sixth Coalition

There was a lull in fighting over the winter of 1812–13 while both the Russians and the French rebuilt their forces; Napoleon was able to field 350,000 troops.[199] Heartened by France’s loss in Russia, Prussia joined with Austria, Sweden, Russia, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal in a new coalition. Napoleon assumed command in Germany and inflicted a series of defeats on the Coalition culminating in the Battle of Dresden in August 1813.[200]

Despite these successes, the numbers continued to mount against Napoleon, and the French army was pinned down by a force twice its size and lost at the Battle of Leipzig. This was by far the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars and cost more than 90,000 casualties in total.[201]

The Allies offered peace terms in the Frankfurt proposals in November 1813. Napoleon would remain as Emperor of the French, but it would be reduced to its «natural frontiers». That meant that France could retain control of Belgium, Savoy and the Rhineland (the west bank of the Rhine River), while giving up control of all the rest, including all of Spain and the Netherlands, and most of Italy and Germany. Metternich told Napoleon these were the best terms the Allies were likely to offer; after further victories, the terms would be harsher and harsher. Metternich’s motivation was to maintain France as a balance against Russian threats while ending the highly destabilizing series of wars.[202]

Napoleon, expecting to win the war, delayed too long and lost this opportunity; by December the Allies had withdrawn the offer. When his back was to the wall in 1814 he tried to reopen peace negotiations on the basis of accepting the Frankfurt proposals. The Allies now had new, harsher terms that included the retreat of France to its 1791 boundaries, which meant the loss of Belgium, but Napoleon would remain Emperor. However, he rejected the term. The British wanted Napoleon permanently removed, and they prevailed, though Napoleon adamantly refused.[202][203]

Napoleon after his abdication in Fontainebleau, 4 April 1814, by Paul Delaroche

Napoleon withdrew into France, his army reduced to 70,000 soldiers and little cavalry; he faced more than three times as many Allied troops.[204] Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s older brother, abdicated as king of Spain on 13 December 1813 and assumed the title of lieutenant general to save the collapsing empire. The French were surrounded: British armies pressed from the south, and other Coalition forces positioned to attack from the German states. By the middle of January 1814, the Coalition had already entered France’s borders and launched a two-pronged attack on Paris, with Prussia entering from the north, and Austria from the East, marching out of the capitulated Swiss confederation. The French Empire, however, would not go down so easily. Napoleon launched a series of victories in the Six Days’ Campaign. While they repulsed the coalition forces and delayed the capture of Paris by at least a full month, these were not significant enough to turn the tide. The coalitionaries camped on the outskirts of the capital on 29 March. A day later, they advanced onto the demoralised soldiers protecting the city. Joseph Bonaparte led a final battle at the gates of Paris. They were greatly outnumbered, as 30,000 French soldiers were pitted against a combined coalition force that was 5 times greater than theirs. They were defeated, and Joseph retreated out of the city. The leaders of Paris surrendered to the Coalition on the last day of March 1814.[205] On 1 April, Alexander addressed the Sénat conservateur. Long docile to Napoleon, under Talleyrand’s prodding it had turned against him. Alexander told the Sénat that the Allies were fighting against Napoleon, not France, and they were prepared to offer honourable peace terms if Napoleon were removed from power. The next day, the Sénat passed the Acte de déchéance de l’Empereur («Emperor’s Demise Act»), which declared Napoleon deposed.

Napoleon had advanced as far as Fontainebleau when he learned that Paris had fallen. When Napoleon proposed the army march on the capital, his senior officers and marshals mutinied.[206] On 4 April, led by Ney, the senior officers confronted Napoleon. When Napoleon asserted the army would follow him, Ney replied the army would follow its generals. While the ordinary soldiers and regimental officers wanted to fight on, the senior commanders were unwilling to continue. Without any senior officers or marshals, any prospective invasion of Paris would have been impossible. Bowing to the inevitable, on 4 April Napoleon abdicated in favour of his son, with Marie Louise as regent. However, the Allies refused to accept this under prodding from Alexander, who feared that Napoleon might find an excuse to retake the throne.[207][208] Napoleon was then forced to announce his unconditional abdication only two days later.[208]

In his farewell address to the soldiers of Old Guard in 20 April, Napoleon said:

«Soldiers of my Old Guard, I have come to bid you farewell. For twenty years you have accompanied me faithfully on the paths of honor and glory. …With men like you, our cause was [not] lost, but the war would have dragged on interminably, and it would have been a civil war. … So I am sacrificing our interests to those of our country. …Do not lament my fate; if I have agreed to live on, it is to serve our glory. I wish to write the history of the great deeds we have done together. Farewell, my children!»[209]

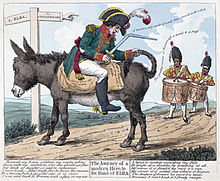

Exile to Elba

Napoleon leaving Elba on 26 February 1815, by Joseph Beaume (1836)

The Allied Powers having declared that Emperor Napoleon was the sole obstacle to the restoration of peace in Europe, Emperor Napoleon, faithful to his oath, declares that he renounces, for himself and his heirs, the thrones of France and Italy, and that there is no personal sacrifice, even that of his life, which he is not ready to make in the interests of France.

Done in the palace of Fontainebleau, 11 April 1814.— Act of abdication of Napoleon[210]

In the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the Allies exiled Napoleon to Elba, an island of 12,000 inhabitants in the Mediterranean, 10 km (6 mi) off the Tuscan coast. They gave him sovereignty over the island and allowed him to retain the title of Emperor. Napoleon attempted suicide with a pill he had carried after nearly being captured by the Russians during the retreat from Moscow. Its potency had weakened with age, however, and he survived to be exiled, while his wife and son took refuge in Austria.[211]

He was conveyed to the island on HMS Undaunted by Captain Thomas Ussher, and he arrived at Portoferraio on 30 May 1814. In the first few months on Elba he created a small navy and army, developed the iron mines, oversaw the construction of new roads, issued decrees on modern agricultural methods, and overhauled the island’s legal and educational system.[212][213]

A few months into his exile, Napoleon learned that his ex-wife Josephine had died in France. He was devastated by the news, locking himself in his room and refusing to leave for two days.[214]

Hundred Days

Separated from his wife and son, who had returned to Austria, cut off from the allowance guaranteed to him by the Treaty of Fontainebleau, and aware of rumours he was about to be banished to a remote island in the Atlantic Ocean,[215] Napoleon escaped from Elba in the brig Inconstant on 26 February 1815 with 700 men.[215] Two days later, he landed on the French mainland at Golfe-Juan and started heading north.[215]

The 5th Regiment was sent to intercept him and made contact just south of Grenoble on 7 March 1815. Napoleon approached the regiment alone, dismounted his horse and, when he was within gunshot range, shouted to the soldiers, «Here I am. Kill your Emperor, if you wish.»[216] The soldiers quickly responded with, «Vive L’Empereur!» Ney, who had boasted to the restored Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, that he would bring Napoleon to Paris in an iron cage, affectionately kissed his former emperor and forgot his oath of allegiance to the Bourbon monarch. The two then marched together toward Paris with a growing army. The unpopular Louis XVIII fled to Belgium after realizing that he had little political support. On 13 March, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw. Four days later, Great Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia each pledged to put 150,000 men into the field to end his rule.[217]

Napoleon arrived in Paris on 20 March and governed for a period now called the Hundred Days. By the start of June, the armed forces available to him had reached 200,000, and he decided to go on the offensive to attempt to drive a wedge between the oncoming British and Prussian armies. The French Army of the North crossed the frontier into the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in modern-day Belgium.[218]

Napoleon’s forces fought two Coalition armies, commanded by the British Duke of Wellington and the Prussian Prince Blücher, at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815. Wellington’s army withstood repeated attacks by the French and drove them from the field while the Prussians arrived in force and broke through Napoleon’s right flank.

Napoleon returned to Paris and found that both the legislature and the people had turned against him. Realizing that his position was untenable, he abdicated on 22 June in favour of his son. He left Paris three days later and settled at Josephine’s former palace in Malmaison (on the western bank of the Seine about 17 kilometres (11 mi) west of Paris). Even as Napoleon travelled to Paris, the Coalition forces swept through France (arriving in the vicinity of Paris on 29 June), with the stated intent of restoring Louis XVIII to the French throne.

When Napoleon heard that Prussian troops had orders to capture him dead or alive, he fled to Rochefort, considering an escape to the United States. British ships were blocking every port. Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland on HMS Bellerophon on 15 July 1815.[219]

Exile on Saint Helena

Napoleon on Saint Helena, watercolor by Franz Josef Sandmann, c. 1820

The British kept Napoleon on the island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, 1,870 km (1,162 mi) from the west coast of Africa. They also took the precaution of sending a small garrison of soldiers to both Saint Helena and the uninhabited Ascension Island, which lay between St. Helena and Europe, to prevent any escape from the island.[220]

Napoleon was moved to Longwood House on Saint Helena in December 1815; it had fallen into disrepair, and the location was damp, windswept and unhealthy.[221][222] The Times published articles insinuating the British government was trying to hasten his death. Napoleon often complained of the living conditions of Longwood House in letters to the island’s governor and his custodian, Hudson Lowe,[223] while his attendants complained of «colds, catarrhs, damp floors and poor provisions.»[224] Modern scientists have speculated that his later illness may have arisen from arsenic poisoning caused by copper arsenite in the wallpaper at Longwood House.[225]

With a small cadre of followers, Napoleon dictated his memoirs and grumbled about the living conditions. Lowe cut Napoleon’s expenditure, ruled that no gifts were allowed if they mentioned his imperial status, and made his supporters sign a guarantee they would stay with the prisoner indefinitely.[226] When he held a dinner party, men were expected to wear military dress and «women [appeared] in evening gowns and gems. It was an explicit denial of the circumstances of his captivity».[227]

While in exile, Napoleon wrote a book about Julius Caesar, one of his great heroes.[228] He also studied English under the tutelage of Count Emmanuel de Las Cases with the main aim of being able to read English newspapers and books, as access to French newspapers and books was heavily restricted to him on Saint Helena.[229] Napoleon also devoted himself to compiling a book «Mémorial de Ste-Hélène«, an account which reflected his self-depiction as a liberal, visionary ruler for European unification, deposed by reactionary elements of the Ancien Régime.[230]