Биография

Братья Гримм – немецкие сказочники, лингвисты, отцы-основатели германской филологии. Пожалуй, сложно будет найти человека, который ни разу не слышал сказок этих великих писателей. Но если не слышал, то непременно видел. По сюжетам произведений братьев Гримм сняты десятки фильмом и мультфильмов, поставлено немало спектаклей. А некоторые персонажи их сказок стали и вовсе именами нарицательными – Золушка, Рапунцель, Спящая красавица.

Детство и юность

Якоб Гримм родился 4 января 1785 года, а через год – 24 февраля 1786 года – на свет появился Вильгельм Гримм. Их отец Филипп Вильгельм Гримм работал адвокатом в Надворном суде города Ханау. В 1791 году его назначили на должность начальника округа Штайнау, куда и пришлось переехать всей его семье. Мужчина работал днями и ночами, в результате усталости и переутомления обыкновенная простуда переросла в пневмонию. В 1796 году он скончался, ему было 44 года.

Разумеется, для семьи Гримм это стало трагедией. Доротея Гримм – мать братьев – осталась одна с шестью детьми. В это время к ним переехала сестра отца – Шарлотта Шлеммер, именно она оказала финансовую помощь семье и спасла от выселения из дома.

Но к Гримм вновь пришла беда – тетушка Шлеммер неожиданно слегла и скоропостижно скончалась. Якоб и Вильгельм были старшими детьми, и им пришлось взять часть обязанностей матери на себя. Но Доротея понимала, что мальчики умны и талантливы, и единственное, что она может им дать, это образование.

В Касселе жила ее сестра – Генриетта Циммер, женщина согласилась принять любимых племянников у себя, чтобы они продолжили учебу в лицее высшей ступени. В гимназии ученики обучались 7-8 лет. Но братья были настолько трудолюбивы и усидчивы, что им удалось овладеть материалом в разы быстрее остальных. Поэтому лицей они закончили уже через четыре года.

В школе мальчики изучали естествознание, географию, этику, физику и философию, но основу преподавания составляли филологические и исторические дисциплины. Якобу все же учеба давалась проще, чем брату. Возможно, что причиной тому было его крепкое здоровье. Вильгельму же диагностировали астму.

В 1802 году Якоб поступил в Марбургский университет на юриста, а вот Вильгельму пришлось остаться, чтобы пройти лечение. На следующий год Якоб перевез брата в Марбург, и он тоже поступил в университет. Правда, ему требовалось регулярное врачебное наблюдение.

В свободное время братья любили рисовать, однажды картины увидел их младший брат Людвиг Эмиль, который так вдохновился этим делом, что свое будущее связал с художественным ремеслом, став популярным в Германии гравером и художником.

Литература

Братья Гримм всегда интересовались литературой. При всем при том, что окончили они юридический факультет, манила их немецкая поэзия, которую им открыл профессор Савиньи. Якоб и Вильгельм часами сидели за изучением старых фолиантов в его домашней библиотеке.

Вся дальнейшая деятельность братьев Гримм была связана непосредственно с немецкой словесностью, филологическими проблемами, проведением исследовательских работ. Сказки – лишь часть невероятного объема работ, который проделали братья в сфере литературы и лингвистики.

В 1808 году Якоб отправился в Париж помогать профессору Савиньи собирать материалы для научной работы. Вильгельм остался доучиваться в университете. С детства они были настолько близки с друг другом, что даже в этом возрасте испытывали небывалую тоску в разлуке, о чем свидетельствует их переписка.

В 1808 году умерла их мать, и все заботы о семье Гримм упали на плечи Якоба. Вернувшись из Франции, он долго искал работу с достойной оплатой труда и в итоге устроился в Кассельский замок, управляющим личной королевской библиотекой. У Вильгельма вновь ухудшилось состояние здоровья, и брат отправил его на курорт. Постоянного места работы на тот момент у него не было.

По возвращении Вильгельма с лечения братья взялись за работу – начали исследовать древнегерманскую литературу. Им удалось собрать, переработать и записать десятки народных легенд, которые передавались из уст в уста сотни лет.

В создании первого тома сказок участвовали многие женщины Касселя. Например, по соседству с Гримм жил состоятельный аптекарь — господин Вильд с женой и детьми. Фрау Вильд знала несчетное количество историй, которые с удовольствием рассказывала Вильгельму. Иногда к ним присоединялись и ее дочери – Гретхен и Дортхен. Пройдет немало лет, ни Дортхен станет женой Вильгельма.

В их доме жила экономка – Мария Мюллер. У пожилой женщины была феноменальная память, и знала она тысячи сказок. Мария рассказала братьям историю о прекрасной Спящей красавице и смелой Красной Шапочке. Но, вспоминая эти сказки, сразу на ум приходит Шарль Перро. Как оказалось, истинного автора сказки найти крайне сложно. По сути, это народные европейские сказки.

Каждый составитель, в том числе и Гримм, на свой лад интерпретировал эти рассказы. Вот, например, сказка о Золушке. В варианте Перро чудеса для девочки совершает ее крестная-фея. А у братьев Гримм – это дерево орешника на могилке ее матери. Позже по мотивам этой истории будет снято кино «Три орешка для Золушки».

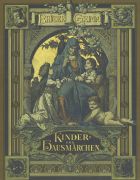

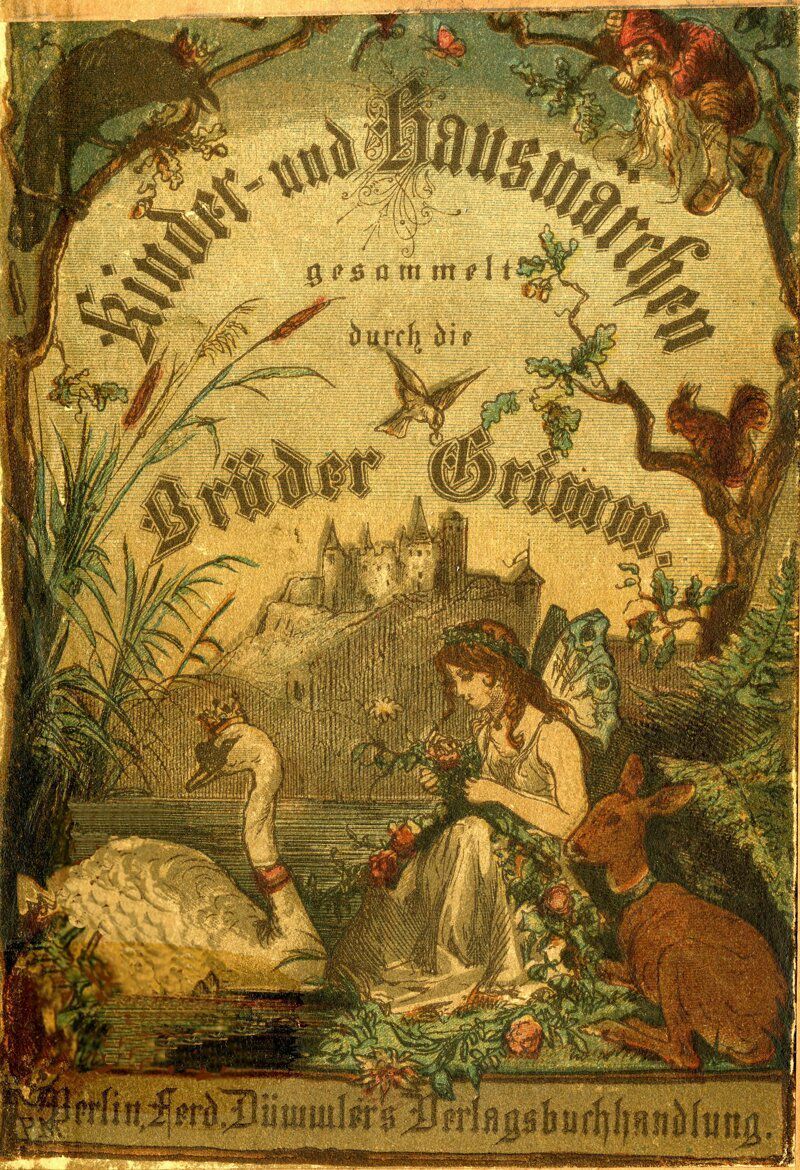

В 1812 году в жизни Якоба и Вильгельма Гримм случился первый успех – они издали сборник «Детские и семейные сказки», в который вошло 100 произведений. Писатели сразу же начали готовить материал для второй книги. В нее вошло немало сказок, услышанных и не самими братьями Гримм, а их друзьями. Как и прежде, писатели оставляли за собой право давать сказкам собственную языковую редакцию. Их вторая книга увидела свет в 1815 году. Правда, книги подвергались переизданиям.

Дело в том, что некоторые сказки были расценены неподходящими для детей. К примеру, был удален фрагмент, где Рапунцель невинно интересуется у крестной, почему платье так обтянуло ее округлившийся живот. Речь шла о ее беременности, наступившей после тайных встреч с принцем.

Первым переводчиком сказок братьев Гримм для русского читателя стал Василий Андреевич Жуковский.

В 1819 году братья издали том «Немецкой грамматики». Эта работа стала сенсацией в научном сообществе, писалась около 20 лет – именно она и стала основой для всех последующих исследований германских языков.

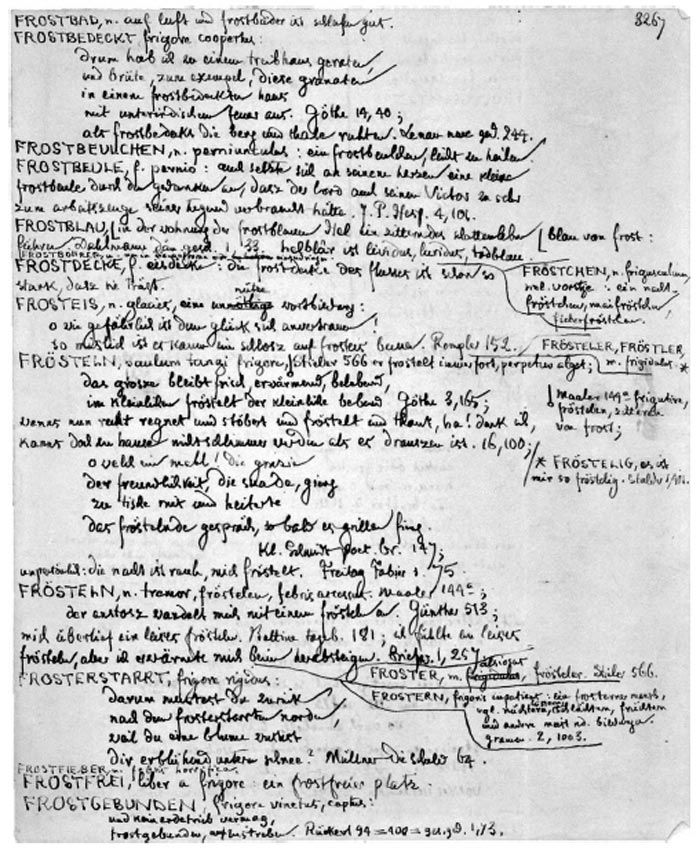

Но все же главным трудом братьев был «Немецкий словарь». Работать над ним они начали в 1838 году. Это была тяжелая и долгая работа. Через 100 лет Томас Манн назвал «Словарь» «героическим делом», «филологическим монументом». Вопреки названию, по сути это был сравнительно-исторический словарь германских языков. Так как писатели не успели закончить работу над словарем, их дело было продолжено следующими поколениями филологов. Таким образом, завершить работу удалось к 1960 году – через 120 лет после ее начала.

Личная жизнь

Вильгельм Гримм в доме аптекаря Вильда познакомился с его дочерью — Дортхен. На тот момент она была еще совсем крошкой. Разница между ними – 10 лет. Но, повзрослев, молодые люди сразу же нашли общий язык. Девушка его поддерживала во всех начинаниях, став в первую очередь для него другом. В 1825 году пара поженилась.

Вскоре девушка забеременела. В 1826 году Дортхен родила мальчика, которого назвали Якобом, а Якоб-старший стал его крестным отцом. Но через полгода малыш скончался от желтухи. В январе 1828 года у супругов родился второй сын – Герман. Позднее он выбрал профессию искусствоведа.

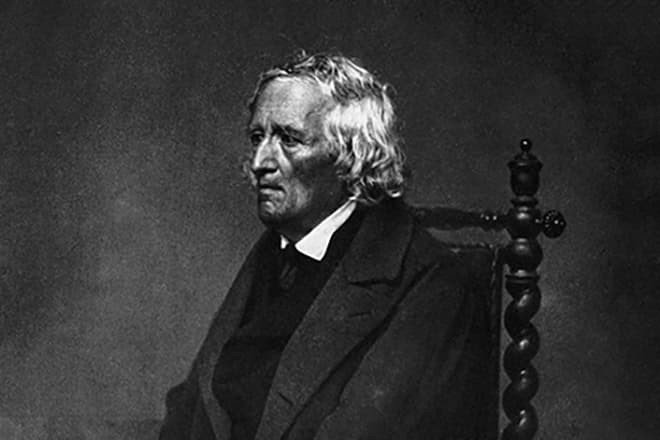

А вот Якоб Гримм так и остался холостяком, свою жизнь мужчина посвятил работе и семье брата.

Смерть

16 декабря 1859 года скончался Вильгельм Гримм. Смертельная болезнь была спровоцирована фурункулом на спине. Он и раньше не отличался крепким здоровьем, но никто в этот раз не ожидал такого печального исхода. С каждым днем Вильгельму становилось хуже. Операция не помогла. У мужчины поднялась температура. Его страдания прекратились от паралича легких через две недели. Якоб продолжал жить с вдовой Вильгельма и племянниками.

До конца жизни писатель работал над словарем. Последнее слово, которое он записал, было слово «Frucht» (плод). Мужчине стало плохо за письменным столом. Умер Якоб от инсульта 20 сентября 1863 года.

Сказочников, знаменитых на весь мир, похоронили на кладбище Святого Матфея в Берлине.

Библиография

- «Волк и семеро козлят»

- «Гензель и Гретель»

- «Красная шапочка»

- «Золушка»

- «Белоснежка и семь гномов»

- «Госпожа метелица»

- «Умная Эльза»

- «Рапунцель»

- «Король Дроздобород»

- «Сладкая каша»

- «Бременские музыканты»

- «Храбрый портняжка»

- «Заяц и еж»

- «Золотой гусь»

- «Спящая красавица»

The Brothers Grimm (die Brüder Grimm or die Gebrüder Grimm), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among the best-known storytellers of folk tales, popularizing stories such as «Cinderella» («Aschenputtel«), «The Frog Prince» («Der Froschkönig«), «Hansel and Gretel» («Hänsel und Gretel«), «Little Red Riding Hood» («Rotkäppchen«), «Rapunzel», «Rumpelstiltskin» («Rumpelstilzchen«), «Sleeping Beauty» («Dornröschen«), and «Snow White» («Schneewittchen«). Their first collection of folk tales, Children’s and Household Tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen), began publication in 1812.

The Brothers Grimm spent their formative years in the town of Hanau in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel. Their father’s death in 1796 (when Jacob was eleven and Wilhelm was ten) caused great poverty for the family and affected the brothers many years after. Both brothers attended the University of Marburg, where they developed a curiosity about German folklore, which grew into a lifelong dedication to collecting German folk tales.

The rise of Romanticism in 19th-century Europe revived interest in traditional folk stories, which to the Brothers Grimm represented a pure form of national literature and culture. With the goal of researching a scholarly treatise on folk tales, they established a methodology for collecting and recording folk stories that became the basis for folklore studies. Between 1812 and 1857 their first collection was revised and republished many times, growing from 86 stories to more than 200. In addition to writing and modifying folk tales, the brothers wrote collections of well-respected Germanic and Scandinavian mythologies, and in 1838 they began writing a definitive German dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch) which they were unable to finish during their lifetimes.

The popularity of the Grimms’ collected folk tales has endured well. The tales are available in more than 100 translations and have been adapted by renowned filmmakers, including Lotte Reiniger and Walt Disney, with films such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In the mid-20th century, the tales were used as propaganda by Nazi Germany; later in the 20th century, psychologists such as Bruno Bettelheim reaffirmed the value of the work in spite of the cruelty and violence in original versions of some of the tales, which were eventually sanitized by the Grimms themselves.

Biography[edit]

Early lives[edit]

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm lived in this house in Steinau from 1791 to 1796

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm were born on 4 January 1785 and 24 February 1786, respectively, in Hanau in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, within the Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany), to Philipp Wilhelm Grimm, a jurist, and Dorothea Grimm (née Zimmer), daughter of a Kassel city councilman.[1] They were the second- and third-eldest surviving siblings in a family of nine children, three of whom died in infancy.[2][a][3] In 1791 the family moved to the countryside town of Steinau during Philipp’s employment there as a district magistrate (Amtmann). The family became prominent members of the community, residing in a large home surrounded by fields. Biographer Jack Zipes writes that the brothers were happy in Steinau and «clearly fond of country life».[1] The children were educated at home by private tutors, receiving strict instruction as Lutherans, which instilled in both a lifelong religious faith.[4] Later, they attended local schools.[1]

In 1796 Philipp Grimm died of pneumonia, causing great poverty for the large family. Dorothea was forced to relinquish the brothers’ servants and large house, depending on financial support from her father and sister, who was then the first lady-in-waiting at the court of William I, Elector of Hesse. Jacob was the eldest living son, forced at age 11 to quickly assume adult responsibilities (shared with Wilhelm) for the next two years. The two brothers then followed the advice of their grandfather, who continually exhorted them to be industrious.[1]

The brothers left Steinau and their family in 1798 to attend the Friedrichsgymnasium in Kassel, which had been arranged and paid for by their aunt. By then they were without a male provider (their grandfather died that year), forcing them to rely entirely on each other and become exceptionally close. The two brothers differed in temperament—Jacob was introspective and Wilhelm was outgoing (although he often suffered from ill health)—but they shared a strong work ethic and excelled in their studies. In Kassel they became acutely aware of their inferior social status relative to «high-born» students who received more attention. Each brother graduated at the head of his class: Jacob in 1803 and Wilhelm in 1804 (he missed a year of school due to scarlet fever).[1][5]

Kassel[edit]

After graduation from the Friedrichsgymnasium, the brothers attended the University of Marburg. The university was small with about 200 students, and there they became painfully aware that students of lower social status were not treated equally. They were disqualified from admission because of their social standing and had to request dispensation to study law. Wealthier students received stipends, but the brothers were excluded even from tuition aid. Their poverty kept them from student activities or university social life. However, their outsider status worked in their favor and they pursued their studies with extra vigor.[5]

Inspired by their law professor, Friedrich von Savigny, who awakened in them an interest in history and philology, the brothers studied medieval German literature.[6] They shared Savigny’s desire to see the unification of the 200 German principalities into a single state. Through Savigny and his circle of friends—German romantics such as Clemens Brentano and Ludwig Achim von Arnim—the Grimms were introduced to the ideas of Johann Gottfried Herder, who thought that German literature should revert to simpler forms, which he defined as Volkspoesie (natural poetry)—as opposed to Kunstpoesie (artistic poetry).[7] The brothers dedicated themselves with great enthusiasm to their studies, about which Wilhelm wrote in his autobiography, «the ardor with which we studied Old German helped us overcome the spiritual depression of those days.»[8]

Jacob was still financially responsible for his mother, brother, and younger siblings in 1805, so he accepted a post in Paris as a research assistant to von Savigny. On his return to Marburg he was forced to abandon his studies to support the family, whose poverty was so extreme that food was often scarce, and take a job with the Hessian War Commission. In a letter written to his aunt at this time, Wilhelm wrote of their circumstances: «We five people eat only three portions and only once a day».[6]

Jacob found full-time employment in 1808 when he was appointed court librarian to the King of Westphalia and went on to become a librarian in Kassel.[2] After their mother’s death that year, he became fully responsible for his younger siblings. He arranged and paid for his brother Ludwig’s studies at art school and for Wilhelm’s extended visit to Halle to seek treatment for heart and respiratory ailments, following which Wilhelm joined Jacob as librarian in Kassel[1] At Brentano’s request, the brothers had begun collecting folk tales in a cursory manner in 1807.[9] According to Jack Zipes, at this point «the Grimms were unable to devote all their energies to their research and did not have a clear idea about the significance of collecting folk tales in this initial phase.»[1]

During their employment as librarians—which paid little but afforded them ample time for research—the brothers experienced a productive period of scholarship, publishing books between 1812 and 1830.[10] In 1812 they published their first volume of 86 folk tales, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, followed quickly by two volumes of German legends and a volume of early literary history.[2] They went on to publish works about Danish and Irish folk tales (and also Norse mythology), while continuing to edit the German folk tale collection. These works became so widely recognized that the brothers received honorary doctorates from universities in Marburg, Berlin, and Breslau (now Wrocław).[10]

Göttingen[edit]

On 15 May 1825 Wilhelm married Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, a pharmacist’s daughter and childhood friend who had given the brothers several tales.[11] Jacob never married but continued to live in the household with Wilhelm and Dortchen.[12] In 1830 both brothers were overlooked when the post of chief librarian came available, which disappointed them greatly.[10] They moved the household to Göttingen in the Kingdom of Hanover, where they took employment at the University of Göttingen—Jacob as a professor and head librarian and Wilhelm as a professor.[2]

During the next seven years the brothers continued to research, write, and publish. In 1835 Jacob published the well-regarded German Mythology (Deutsche Mythologie); Wilhelm continued to edit and prepare the third edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen for publication. The two brothers taught German studies at the university, becoming well-respected in the newly established discipline.[12]

In 1837 the brothers lost their university posts after joining the rest of the Göttingen Seven in protest. The 1830s were a period of political upheaval and peasant revolt in Germany, leading to the movement for democratic reform known as Young Germany. The brothers were not directly aligned with the Young Germans, but they and five of their colleagues reacted against the demands of Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, who in 1837 dissolved the parliament of Hanover and demanded oaths of allegiance from civil servants—including professors at the University of Göttingen. For refusing to sign the oath, the seven professors were dismissed and three were deported from Hanover—including Jacob, who went to Kassel. He was later joined there by Wilhelm, Dortchen, and their four children.[12]

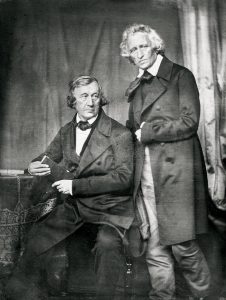

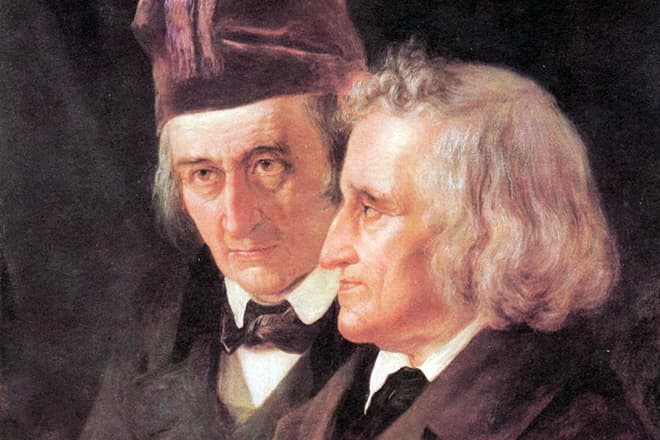

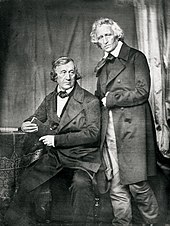

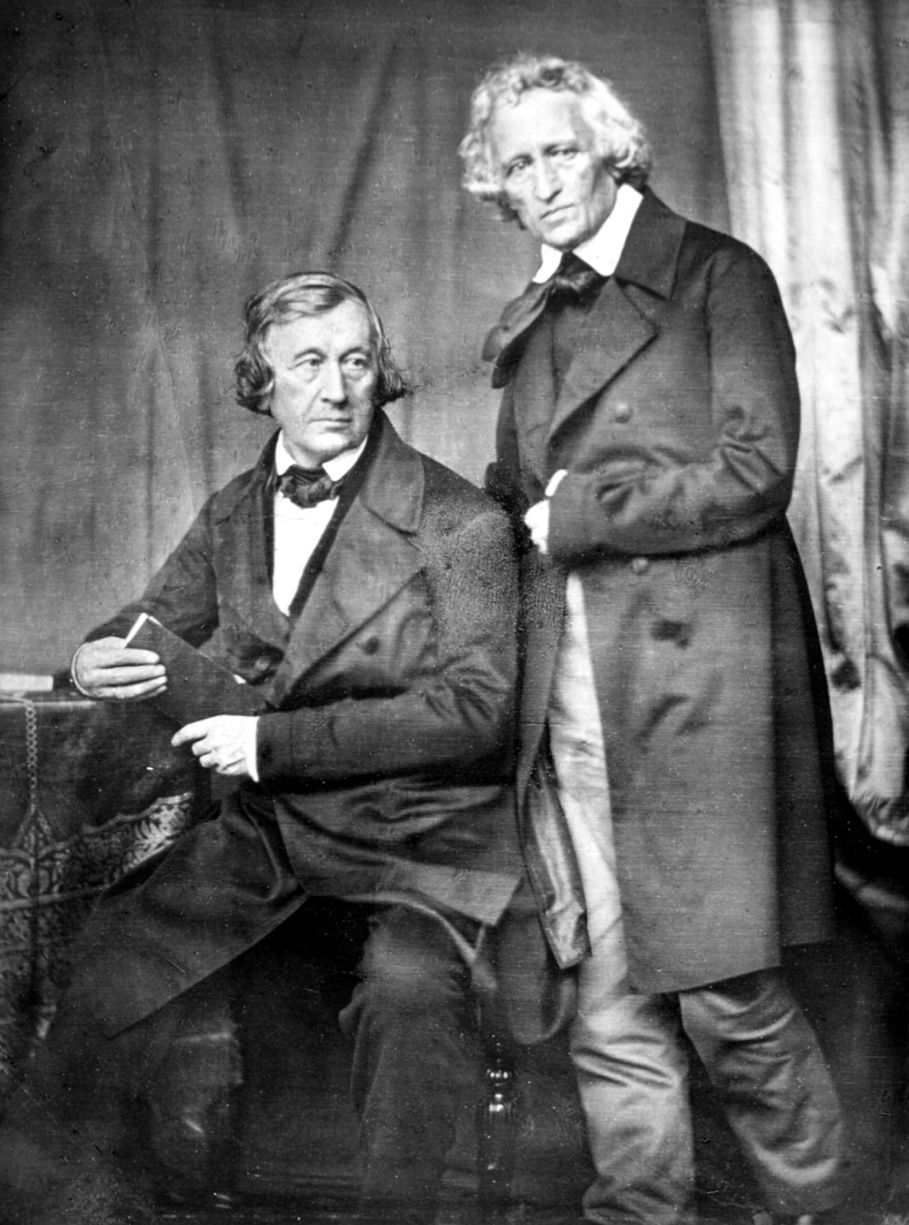

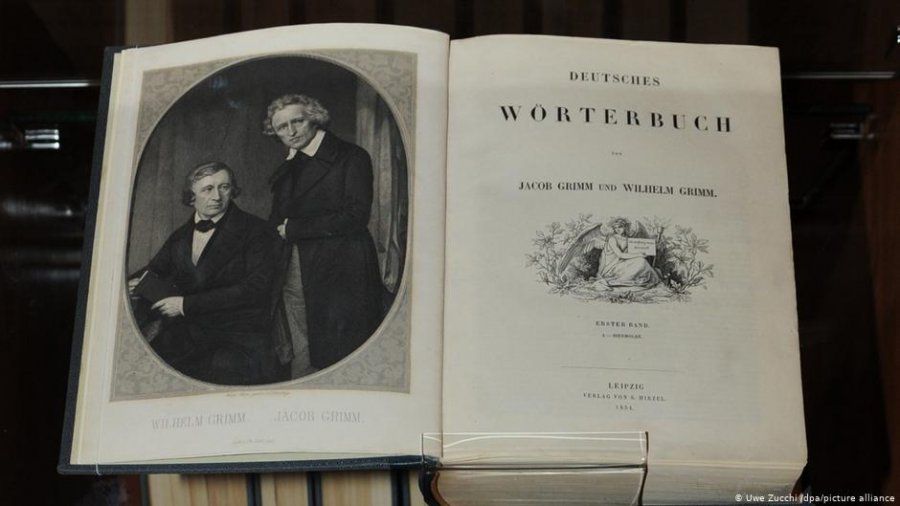

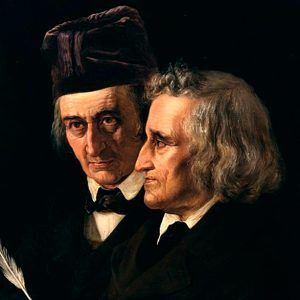

Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, c. 1837

The brothers were without income and again in extreme financial difficulty in 1838, so they began what would become a lifelong project—the writing of a definitive dictionary, the German Dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch)—whose first volume was not published until 1854. The brothers again depended on friends and supporters for financial assistance and influence in finding employment.[12]

Berlin and later years[edit]

In 1840, von Savigny and Bettina von Arnim appealed successfully to Frederick William IV of Prussia on behalf of the brothers, who were offered posts at the University of Berlin. In addition to teaching posts, the Academy of Sciences offered them stipends to continue their research. Once they had established their household in Berlin they directed their efforts towards the work on the German dictionary and continued to publish their research. Jacob turned his attention to researching German legal traditions and the history of the German language, which was published in the late 1840s and early 1850s; meanwhile Wilhelm began researching medieval literature while editing new editions of Hausmärchen.[10]

The graves of the Brothers Grimm in Schöneberg, Berlin (St. Matthäus Kirchhof Cemetery)

After the revolutions of 1848 in the German states the brothers were elected to the civil parliament. Jacob became a prominent member of the National Assembly at Mainz.[12] Their political activities were short-lived, however, as their hope for a unified Germany dwindled and their disenchantment grew. In the late 1840s Jacob resigned his university position and published The History of the German Language (Geschichte der deutschen Sprache). Wilhelm continued at his university post until 1852. After retiring from teaching the brothers devoted themselves to the German Dictionary for the rest of their lives.[12] Wilhelm died of an infection in Berlin on 16 December 1859,[13] and Jacob, deeply upset at his brother’s death, became increasingly reclusive. He continued working on the dictionary until his own death on 20 September 1863. Zipes writes of the Grimms’ dictionary, and of their very large body of work: «Symbolically the last word was Frucht (fruit).»[12]

Collaborations[edit]

Children’s and Household Tales[edit]

Background[edit]

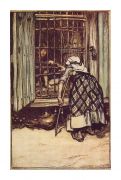

The Grimms defined «Little Red Riding Hood», shown here in an illustration by Arthur Rackham, as representative of a uniquely German tale, although it existed in various versions and regions[14]

The rise of romanticism, romantic nationalism, and trends in valuing popular culture in the early 19th century revived interest in fairy tales, which had declined since their late 17th-century peak.[15] Johann Karl August Musäus published a popular collection of tales called Volksmärchen der Deutschen between 1782 and 1787;[16] the Grimms aided the revival with their folklore collection, built on the conviction that a national identity could be found in popular culture and with the common folk (Volk). They collected and published their tales as a reflection of German cultural identity. In the first collection, though, they included Charles Perrault’s tales, published in Paris in 1697 and written for the literary salons of an aristocratic French audience. Scholar Lydie Jean says that Perrault created a myth that his tales came from the common people and reflected existing folklore to justify including them—even though many of them were original.[15]

The brothers were directly influenced by Brentano and von Arnim, who edited and adapted the folk songs of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn or cornucopia).[16] They began the collection with the purpose of creating a scholarly treatise of traditional stories, and of preserving the stories, as they had been handed from generation to generation—a practice that was threatened by increased industrialization.[17] Maria Tatar, professor of German studies at Harvard University, explains that it is precisely the handing from generation to generation and the genesis in the oral tradition that gives folk tales an important mutability. Versions of tales differ from region to region, «picking up bits and pieces of local culture and lore, drawing a turn of phrase from a song or another story, and fleshing out characters with features taken from the audience witnessing their performance.»[18]

However, as Tatar explains, the Grimms appropriated stories as being uniquely German, such as «Little Red Riding Hood», which had existed in many versions and regions throughout Europe, because they believed that such stories were reflections of Germanic culture.[14] Furthermore, the brothers saw fragments of old religions and faiths reflected in the stories, which they thought continued to exist and survive through the telling of stories.[19]

Methodology[edit]

When Jacob returned to Marburg from Paris in 1806, their friend Brentano sought the brothers’ help in adding to his collection of folk tales, at which time the brothers began to gather tales in an organized fashion.[1] By 1810 they had produced a manuscript collection of several dozen tales, written after inviting storytellers to their home and transcribing what they heard. These tales were heavily modified in transcription; many had roots in previously written sources.[20] At Brentano’s request, they printed and sent him copies of the 53 tales that they collected for inclusion in his third volume of Des Knaben Wunderhorn.[2] Brentano either ignored or forgot about the tales, leaving the copies in a church in Alsace where they were found in 1920 and became known as the Ölenberg manuscript. It is the earliest extant version of the Grimms’ collection and has become a valuable source to scholars studying the development of the Grimms’ collection from the time of its inception. The manuscript was published in 1927 and again in 1975.[21]

The brothers gained a reputation for collecting tales from peasants, although many tales came from middle-class or aristocratic acquaintances. Wilhelm’s wife, Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, and her family, with their nursery maid, told the brothers some of the more well-known tales, such as «Hansel and Gretel» and «Sleeping Beauty».[22] Wilhelm collected some tales after befriending August von Haxthausen, whom he visited in 1811 in Westphalia where he heard stories from von Haxthausen’s circle of friends.[23] Several of the storytellers were of Huguenot ancestry, telling tales of French origin such as those told to the Grimms by Marie Hassenpflug, an educated woman of French Huguenot ancestry,[20] and it is probable that these informants were familiar with Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé (Stories from Past Times).[15] Other tales were collected from Dorothea Viehmann, the wife of a middle-class tailor and also of French descent. Despite her middle-class background, in the first English translation she was characterized as a peasant and given the name Gammer Gretel.[17] At least one tale, Gevatter Tod (Grim Reaper), was provided by composer Wilhelmine Schwertzell,[24] with whom Wilhelm had a lengthy correspondence.[25]

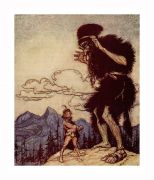

Stories such as «Sleeping Beauty», shown here in a Walter Crane illustration, had been previously published and were rewritten by the Brothers Grimm[15]

According to scholars such as Ruth Bottigheimer and Maria Tatar, some of the tales probably originated in written form during the medieval period with writers such as Straparola and Boccaccio, but were modified in the 17th century and again rewritten by the Grimms. Moreover, Tatar writes that the brothers’ goal of preserving and shaping the tales as something uniquely German at a time of French occupation was a form of «intellectual resistance», and in so doing they established a methodology for collecting and preserving folklore that set the model followed later by writers throughout Europe during periods of occupation.[17][26]

Writing[edit]

From 1807 onwards, the brothers added to the collection. Jacob established the framework, maintained through many iterations; from 1815 until his death, Wilhelm assumed sole responsibility for editing and rewriting the tales. He made the tales stylistically similar, added dialogue, removed pieces «that might detract from a rustic tone», improved the plots, and incorporated psychological motifs.[23] Ronald Murphy writes in The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove that the brothers, and in particular Wilhelm, also added religious and spiritual motifs to the tales. He believes that Wilhelm «gleaned» bits from old Germanic faiths, Norse mythology, Roman and Greek mythology, and biblical stories that he reshaped.[19]

Over the years, Wilhelm worked extensively on the prose; he expanded and added detail to the stories to the point that many of them grew to twice the length that they were in the earliest published editions.[27] In the later editions Wilhelm polished the language to make it more enticing to a bourgeois audience, eliminated sexual elements, and added Christian elements. After 1819 he began writing original tales for children (children were not initially considered the primary audience) and adding didactic elements to existing tales.[23]

Some changes were made in light of unfavorable reviews, particularly from those who objected that not all the tales were suitable for children because of scenes of violence and sexuality.[28] He worked to modify plots for many of the stories; for example, «Rapunzel» in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen clearly shows a sexual relationship between the prince and the girl in the tower, which he edited out in subsequent editions.[27] Tatar writes that morals were added (in the second edition a king’s regret was added to the scene in which his wife is to be burned at the stake) and often the characters in the tale were amended to appear more German: «every fairy (Fee), prince (Prinz) and princess (Prinzessin)—all words of French origin—was transformed into a more Teutonic-sounding enchantress (Zauberin) or wise woman (weise Frau), king’s son (Königssohn), king’s daughter (Königstochter).»[29]

Themes and analysis[edit]

The Grimms’ legacy contains legends, novellas, and folk stories, the vast majority of which were not intended as children’s tales. Von Armin was concerned about the content of some of the tales—such as those that showed children being eaten—and suggested adding a subtitle to warn parents of the content. Instead the brothers added an introduction with cautionary advice that parents steer children toward age-appropriate stories. Despite von Armin’s unease, none of the tales were eliminated from the collection in the brothers’ belief that all the tales were of value and reflected inherent cultural qualities. Furthermore, the stories were didactic in nature at a time when discipline relied on fear, according to scholar Linda Dégh, who explains that tales such as «Little Red Riding Hood» and «Hansel and Gretel» were written as «warning tales» for children.[30]

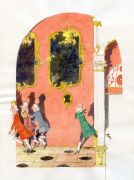

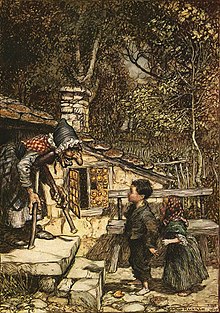

«Hansel and Gretel», illustrated by Arthur Rackham, was a «warning tale» for children[30]

The stories in Kinder- und Hausmärchen include scenes of violence that have since been sanitized. For example, in the Grimms’ original version of «Snow White», the Queen is Little Snow White’s mother, not her stepmother, yet even so she orders her Huntsman to kill Snow White (her biological daughter) and bring home the child’s lungs and liver so that she can eat them; the story ends with the Queen dancing at Snow White’s wedding, wearing a pair of red-hot iron shoes that kill her.[31] Another story («The Goose Girl») has a servant being stripped naked and pushed into a barrel «studded with sharp nails» pointing inwards and then rolled down the street.[13] The Grimms’ version of «The Frog Prince» describes the princess throwing the frog against a wall instead of kissing him. To some extent the cruelty and violence may have been a reflection of medieval culture from which the tales originated, such as scenes of witches burning, as described in «The Six Swans».[13]

Tales with a spinning motif are broadly represented in the collection. In her essay «Tale Spinners: Submerged Voices in Grimms’ Fairy Tales», children’s literature scholar Bottigheimer explains that these stories reflect the degree to which spinning was crucial in the life of women in the 19th century and earlier. Spinning, and particularly the spinning of flax, was commonly performed in the home by women. Many stories begin by describing the occupation of their main character, as in «There once was a miller», yet spinning is never mentioned as an occupation; this appears to be because the brothers did not consider it to be an occupation. Instead, spinning was a communal activity, frequently performed in a Spinnstube (spinning room), a place where women most likely kept the oral traditions alive by telling stories while engaged in tedious work.[32] In the stories, a woman’s personality is often represented by her attitude towards spinning; a wise woman might be a spinster and Bottigheimer explains that the spindle was the symbol of a «diligent, well-ordered womanhood».[33] In some stories, such as «Rumpelstiltskin», spinning is associated with a threat; in others, spinning might be avoided by a character who is either too lazy or not accustomed to spinning because of her high social status.[32]

The tales were also criticized for being insufficiently German, which influenced the tales that the brothers included and their use of language. Scholars such as Heinz Rölleke, however, say that the stories are an accurate depiction of German culture, showing «rustic simplicity [and] sexual modesty».[13] German culture is deeply rooted in the forest (wald), a dark dangerous place to be avoided, most particularly the old forests with large oak trees, and yet a place where Little Red Riding Hood’s mother sent her daughter to deliver food to her grandmother’s house.[13]

Some critics, such as Alistair Hauke, use Jungian analysis to say that the deaths of the brothers’ father and grandfather are the reason for the Grimms’ tendency to idealize and excuse fathers, as well as the predominance of female villains in the tales, such as the wicked stepmother and stepsisters in «Cinderella», but this disregards the fact that they were collectors, not authors of the tales.[34] Another possible influence is found in stories such as «The Twelve Brothers», which mirrors the brothers’ family structure of several brothers facing and overcoming opposition.[35] Autobiographical elements exist in some of the tales, and according to Zipes the work may have been a «quest» to replace the family life lost after their father died. The collection includes 41 tales about siblings, which Zipes says are representative of Jacob and Wilhelm. Many of the sibling stories follow a simple plot where the characters lose a home, work industriously at a specific task, and in the end find a new home.[36]

Editions[edit]

Between 1812 and 1864, Kinder- und Hausmärchen was published 17 times: seven of the «Large edition» (Große Ausgabe) and ten of the «Small edition» (Kleine Ausgabe). The Large editions contained all the tales collected to date, extensive annotations, and scholarly notes written by the brothers; the Small editions had only 50 tales and were intended for children. Emil Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm’s younger brother, illustrated the Small editions, adding Christian symbolism to the drawings, such as depicting Cinderella’s mother as an angel and adding a Bible to the bedside table of Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother.[10]

The first volume was published in 1812 with 86 folk tales,[22] and a second volume with 70 additional tales was published late in 1814 (dated 1815 on the title page); together the two volumes and their 156 tales are considered the first of the (annotated) Large editions.[37][38] A second expanded edition with 170 tales was published in 1819, followed in 1822 by a volume of scholarly commentary and annotations.[2][28] Five more Large editions were published in 1837, 1840, 1843, 1850, and 1857. The seventh and final edition of 1857 contained 211 tales—200 numbered folk tales and eleven legends.[2][28][38]

In Germany Kinder- und Hausmärchen, commonly Grimms’ Fairy Tales in English, was also released in a «popular poster-sized Bilderbogen (broadsides)»[38] format and in single story formats for the more popular tales such as «Hansel and Gretel». The stories were often added to collections by other authors without respect to copyright as the tales became a focus of interest for children’s book illustrators,[38] with well-known artists such as Arthur Rackham, Walter Crane, and Edmund Dulac illustrating the tales. Another popular edition that sold well released in the mid-19th century included elaborate etchings by George Cruikshank.[39] Upon the deaths of the brothers, the copyright went to Hermann Grimm (Wilhelm’s son), who continued the practice of printing the volumes in expensive and complete editions; however, after 1893 when copyright lapsed various publishers began to print the stories in many formats and editions.[38] In the 21st century, Kinder- und Hausmärchen is a universally recognized text. Jacob and Wilhelm’s collection of stories has been translated to more than 160 languages; 120 different editions of the text are available for sale in the US alone.[13]

Philology[edit]

While at the University of Marburg, the brothers came to see culture as tied to language and regarded the purest cultural expression in the grammar of a language. They moved away from Brentano’s practice—and that of the other romanticists—who frequently changed original oral styles of folk tale to a more literary style, which the brothers considered artificial. They thought that the style of the people (the volk) reflected a natural and divinely inspired poetry (naturpoesie)—as opposed to the kunstpoesie (art poetry), which they saw as artificially constructed.[40][41] As literary historians and scholars they delved into the origins of stories and attempted to retrieve them from the oral tradition without loss of the original traits of oral language.[40]

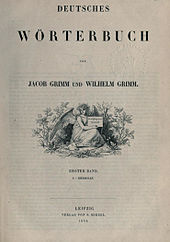

Frontispiece of 1854 edition of German Dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch)

The brothers strongly believed that the dream of national unity and independence relied on a full knowledge of the cultural past that was reflected in folklore.[41] They worked to discover and crystallize a kind of Germanness in the stories that they collected in the belief that folklore contained kernels of mythologies and legends, crucial to understanding the essence of German culture.[17] In examining culture from a philological point of view they sought to establish connections between German law, culture, and local beliefs.[40]

The Grimms considered the tales to have origins in traditional Germanic folklore, which they thought had been «contaminated» by later literary tradition.[17] In the shift from the oral tradition to the printed book, tales were translated from regional dialects to Standard German (Hochdeutsch or High German).[42] Over the course of the many modifications and revisions, however, the Grimms sought to reintroduce regionalisms, dialects, and Low German to the tales—to re-introduce the language of the original form of the oral tale.[43]

As early as 1812 they published Die beiden ältesten deutschen Gedichte aus dem achten Jahrhundert: Das Lied von Hildebrand und Hadubrand und das Weißenbrunner Gebet (The Two Oldest German Poems of the Eighth Century: The Song of Hildebrand and Hadubrand and the Wessobrunn Prayer); the Song of Hildebrand and Hadubrand is a ninth-century German heroic song, while the Wessobrunn Prayer is the earliest-known German heroic song.[44]

Between 1816 and 1818 the brothers published a two-volume work titled Deutsche Sagen (German Legends), consisting of 585 German legends.[37] Jacob undertook most of the work of collecting and editing the legends, which he organized according to region and historical (ancient) legends[45] and were about real people or events.[44] The brothers meant it as a scholarly work, yet the historical legends were often taken from secondary sources, interpreted, modified, and rewritten—resulting in works «that were regarded as trademarks».[45] Some scholars criticized the Grimms’ methodology in collecting and rewriting the legends, yet conceptually they set an example for legend collections that was followed by others throughout Europe. Unlike the collection of folk tales, Deutsche Sagen sold poorly,[45] but Zipes says that the collection, translated to French and Danish in the 19th century but not to English until 1981, is a «vital source for folklorists and critics alike».[46]

Less well known in the English-speaking world is the Grimms’ pioneering scholarly work on a German dictionary, the Deutsches Wörterbuch, which they began in 1838. Not until 1852 did they begin publishing the dictionary in installments.[45] The work on the dictionary was not finished in their lifetimes, because in it they gave a history and analysis of each word.[44]

Reception and legacy[edit]

Berlin memorial plaque, Brüder Grimm, Alte Potsdamer Straße 5, Berlin-Tiergarten, Germany

Design of the front of the 1992 1000 Deutsche Mark showing the Brothers Grimm[47]

Kinder- und Hausmärchen was not an immediate bestseller, but its popularity grew with each edition.[48] The early editions attracted lukewarm critical reviews, generally on the basis that the stories were unappealing to children. The brothers responded with modifications and rewrites to increase the book’s market appeal to that demographic.[17] By the 1870s the tales had increased greatly in popularity to the point that they were added to the teaching curriculum in Prussia. In the 20th century the work maintained status as second only to the Bible as the most popular book in Germany. Its sales generated a mini-industry of criticism, which analyzed the tales’ folkloric content in the context of literary history, socialism, and psychological elements often along Freudian and Jungian lines.[48]

In their research, the brothers made a science of the study of folklore (see folkloristics), generating a model of research that «launched general fieldwork in most European countries»,[49] and setting standards for research and analysis of stories and legends that made them pioneers in the field of folklore in the 19th century.[50]

In Nazi Germany the Grimms’ stories were used to foster nationalism as well as to promote antisemitic sentiments in an increasingly hostile time for Jewish people. Some examples of notable antisemitic works in the Grimms’ bibliography are «The Girl Who Was Killed by Jews», «The Jews’ Stone», «The Jew Among Thorns» and «The Good Bargain». “The Girl Who Was Killed by Jews” and “The Jews’ Stone” tell stories of blood libel by Jews against innocent children. In both stories the children are violently killed and mutilated.[51] The myth of blood libel was widely propagated during the Middle Ages and is still used to vilify Jews today.[52] The children in these two stories are also acquired in exchange for large sums of money. Jewish wealth and greed are also common antisemitic tropes.[53] These tropes appear in “The Jew Among Thorns” and “The Good Bargain”. In both stories a Jewish man is depicted as deceitful for the sake of money. In the former the man admits to stealing money and is executed instead of the protagonist. In the latter, the Jewish man is found to be deceitful in order to be rewarded a sum of money. The specific deceit is irrelevant and here too the protagonist triumphs over the Jew.[54] [55]All of these stories paint Jews as antagonists whether through murderous rites, deceit, or greed. Antisemitism in folklore has contributed to the popularization of antisemitic tropes and misconceptions about the Jewish faith, but the Nazi Party was particularly devoted to the Grimms’ collected stories. According to author Elizabeth Dalton, «Nazi ideologues enshrined the Kinder-und Hausmarchen as virtually a sacred text…» The Nazi Party decreed that every household should own a copy of Kinder- und Hausmärchen; later, officials of Allied-occupied Germany banned the book for a period.[56]

In the United States the 1937 release of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs shows the triumph of good over evil, innocence over oppression, according to Zipes.[57] The Grimms’ tales have provided much of the early foundation on which Disney built an empire.[13] In film, the Cinderella motif, the story of a poor girl finding love and success, has been repeated in movies such as Pretty Woman, Ever After, Maid in Manhattan, and Ella Enchanted.[58]

20th-century educators debated the value and influence of teaching stories that include brutality and violence, and some of the more gruesome details were sanitized.[48] Dégh writes that some educators, in the belief that children should be shielded from cruelty of any form, believe that stories with a happy ending are fine to teach, whereas those that are darker, particularly the legends, might pose more harm. On the other hand, some educators and psychologists believe that children easily discern the difference between what is a story and what is not and that the tales continue to have value for children.[59] The publication of Bruno Bettelheim’s 1976 The Uses of Enchantment brought a new wave of interest in the stories as children’s literature, with an emphasis on the «therapeutic value for children».[58] More popular stories, such as «Hansel and Gretel» and «Little Red Riding Hood», have become staples of modern childhood, presented in coloring books, puppet shows, and cartoons. Other stories, however, have been considered too gruesome and have not made a popular transition.[56]

Regardless of the debate, the Grimms’ stories have continued to be resilient and popular around the world,[59] although a recent study in England appears to suggest that parents consider the stories to be overly violent and inappropriate for young children, writes Libby Copeland for Slate.[60]

Nevertheless, children remain enamored of the Grimms’ fairy tales with the brothers themselves embraced as the creators of the stories and even as part of the stories themselves. The film Brothers Grimm imagines them as con-artists exploiting superstitious German peasants until they are asked to confront a genuine fairy-tale curse that calls them to finally be heroes. The movie Ever After shows the Grimms in their role as collectors of fairy tales, though they learn to their surprise that at least one of their stories (Cinderella) is actually true. Grimm follows a detective who discovers that he is a Grimm, the latest in a line of guardians who are sworn to keep the balance between humanity and mythological creatures. Ever After High imagines the Grimms (here called Milton and Giles) as the headmasters of the Ever After High boarding school, where they train the children of the previous generation of fairy tales to follow in their parents’ footsteps. The 10th Kingdom miniseries states that the brothers were trapped in the fairy tale world for years where they witnessed the events of their stories before finally making it back to the real world. The Sisters Grimm book series follows their descendants, Sabrina and Daphne, as they adapt to life in Ferryport Landing, a town in upstate New York populated by the fairy-tale people. Separate from the previous series are The Land of Stories and its Sisters Grimm, a self-described coven determined to track down and document creatures from the fairy-tale world that cross over to the real world. Their ancestors were, in fact, chosen by Mother Goose and others to tell fairy tales so that they might give hope to the human race.[citation needed]

The university library at the Humboldt University of Berlin is housed in the Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm Center (Jakob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum);[61] among its collections is a large portion of the Grimms’ private library.[62]

Collaborative works[edit]

- Die beiden ältesten deutschen Gedichte aus dem achten Jahrhundert: Das Lied von Hildebrand und Hadubrand und das Weißenbrunner Gebet, (The Two Oldest German Poems of the Eighth Century: The Song of Hildebrand and Hadubrand and the Wessobrunn Prayer)—ninth century heroic song, published 1812

- Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)—seven editions, between 1812 and 1857[63]

- Altdeutsche Wälder (Old German Forests)—three volumes between 1813 and 1816

- Der arme Heinrich von Hartmann von der Aue (Poor Heinrich by Hartmann von der Aue)—1815

- Lieder der alten Edda (Songs from the Elder Edda)—1815

- Deutsche Sagen (German Sagas)—published in two parts between 1816 and 1818

- Irische Elfenmärchen—Grimms’ translation of Thomas Crofton Croker’s Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, 1826

- Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary)—32 volumes published between 1852 and 1960[44]

Popular adaptations[edit]

The below includes adaptations from the work of the Brothers Grimm:

- Avengers Grimm, 2015 American film

- Grimm, 2011 fantasy crime television series about a Grimm descendant

- Once Upon a Time, American television series

- The 10th Kingdom, 2000 American television miniseries

- The Brothers Grimm, 2005 film starring Matt Damon and Heath Ledger

- The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, 1962 film starring Lawrence Harvey and Walter Slezak

- Simsala Grimm, children television series

- A Tale Dark & Grimm, children’s book by Adam Gidwitz

- The Family Guy episode entitled “Grimm Job” (Season 12, Episode 10), sees the show’s characters take on roles in three Grimm Brothers fairy tales: “Jack and the Beanstalk”, “Cinderella”, and “Little Red Riding Hood”.

See also[edit]

- Grimm Family Tree

- Hans Christian Andersen

- Alexander Afanasyev

- Charles Perrault

- Giambattista Basile

- Norwegian Folktales

- Russian fairy tale

Notes[edit]

- ^ Frederick Herman George (Friedrich Hermann Georg; 12 December 1783 – 16 March 1784), Jacob, Wilhelm, Carl Frederick (Carl Friedrich; 24 April 1787 – 25 May 1852), Ferdinand Philip (Ferdinand Philipp; 18 December 1788 – 6 January 1845), Louis Emil (Ludwig Emil; 14 March 1790 – 4 April 1863), Frederick (Friedrich; 15 June 1791 – 20 August 1792), Charlotte «Lotte» Amalie (10 May 1793 – 15 June 1833), and George Edward (Georg Eduard; 26 July 1794 – 19 April 1795).

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zipes 1988, pp. 2–5

- ^ a b c d e f g Ashliman, D.L. «Grimm Brothers Home Page». University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Michaelis-Jena 1970, p. 9

- ^ Herbert Scurla: Die Brüder Grimm, Berlin 1985, pp. 14–16

- ^ a b Zipes 1988, p. 31

- ^ a b qtd. in Zipes 1988, p. 35

- ^ Zipes 2002, pp. 7–8

- ^ qtd. in Zipes 2002, p. 7

- ^ Zipes 2014, p. xxiv

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 2000, pp. 218–219

- ^ See German (wikipedia.de) page on Wild (Familie) for more of Wilhelm’s in-laws.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zipes 1988, pp. 7–9

- ^ a b c d e f g O’Neill, Thomas. «Guardians of the Fairy Tale: The Brothers Grimm». National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b Tatar 2004, pp. xxxviii

- ^ a b c d Jean 2007, pp. 280–282

- ^ a b Haase 2008, p. 138

- ^ a b c d e f Tatar 2004, pp. xxxiv–xxxviii

- ^ Tatar 2004, pp. xxxvi

- ^ a b Murphy 2000, pp. 3–4

- ^ a b Haase 2008, p. 579

- ^ Zipes 2000, p. 62

- ^ a b Joosen 2006, pp. 177–179

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 11–14

- ^ Schnack, Ingeborg (1958). Lebensbilder aus Kurhessen und Waldeck 1830-1930 (in German). N.G. Elwert.

- ^ «29. Juli─01. September ¤ WTB: • Willingshäuser Malersymposium • — Künstlerkolonie Willingshausen». www.malerkolonie.de. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- ^ Bottigheimer 1982, pp. 175

- ^ a b Tatar 2004, pp. xi–xiii

- ^ a b c Tatar 1987, pp. 15–17

- ^ Tatar 1987, p. 31

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 91–93

- ^ Jack Zipes’ translation of the 1812 original edition of «Folk and Fairy Tales»

- ^ a b Bottigheimer 1982, pp. 142–146

- ^ Bottigheimer 1982, p. 143

- ^ Alister & Hauke 1998, pp. 216–219

- ^ Tatar 2004, p. 37

- ^ Zipes 1988, pp. 39–42

- ^ a b Michaelis-Jena 1970, p. 84

- ^ a b c d e Zipes 2000, pp. 276–278

- ^ Haase 2008, p. 73

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 32–35

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 84–85

- ^ Zipes 1994, p. 14

- ^ Robinson 2004, pp. 47–49

- ^ a b c d Hettinga 2001, pp. 154–155

- ^ a b c d Haase 2008, pp. 429–431

- ^ Zipes 1984, p. 162

- ^ Deutsche Bundesbank (Hrsg.): Von der Baumwolle zum Geldschein. Eine neue Banknotenserie entsteht. 2. Auflage. Verlag Fritz Knapp GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-611-00222-4, S. 103.

- ^ a b c Zipes 1988, pp. 15–17

- ^ Dégh 1979, p. 87

- ^ Zipes 1984, p. 163

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. (Trans.). (n.d.). Anti-Semitic Legends. From https://web.archive.org/web/20200217170908/http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/antisemitic.html#stone

- ^ TETER, M. (2020). Introduction. In Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth (pp. 1–13). Harvard University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvt1sj9x.6

- ^ Foxman, Abraham (2010). Jews and Money: The Story of a Stereotype. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- ^ The Brothers Grimm. (n.d.). The jew in the thorns. Grimm 110: The Jew in the Thorns. From https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm110.html

- ^ The Brothers Grimm. (n.d.). The good bargain. Grimm 007: The Good Bargain. From https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm007.html

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 94–96

- ^ Zipes 1988, p. 25

- ^ a b Tatar 2010

- ^ a b Dégh 1979, pp. 99–101

- ^ Copeland, Libby (29 February 2012). «Tales Out of Fashion?». Slate. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ «Jacob-und-Wilhelm-Grimm-Zentrum». Humboldt University of Berlin. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ «The Grimm Library». Humboldt University of Berlin. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ «Grimm Brothers’ Home Page».

Sources[edit]

- Alister, Ian; Hauke, Christopher, eds. (1998). Contemporary Jungian Analysis. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14166-6.

- Bottigheimer, Ruth (1982). «Tale Spinners: Submerged Voices in Grimms’ Fairy Tales». New German Critique. 27 (27): 141–150. doi:10.2307/487989. JSTOR 487989.

- Dégh, Linda (1979). «Grimm’s Household Tales and its Place in the Household». Western Folklore. 38 (2): 85–103. doi:10.2307/1498562. JSTOR 1498562.

- Haase, Donald (2008). «Literary Fairy Tales». In Donald Haase (ed.). The Greenwood encyclopedia of folktales and fairy tales. Vol. 2. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33441-2.

- Hettinga, Donald (2001). The Brothers Grimm. New York: Clarion. ISBN 978-0-618-05599-9.

- Jean, Lydie (2007). «Charles Perrault’s Paradox: How Aristocratic Fairy Tales became Synonymous with Folklore Conservation» (PDF). Trames. 11 (61): 276–283. doi:10.3176/tr.2007.3.03. S2CID 55129946. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Joosen, Vanessa (2006). The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Children’s Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514656-1.

- Michaelis-Jena, Ruth (1970). The Brothers Grimm. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-6449-3.

- Murphy, Ronald G. (2000). The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515169-5.

- Robinson, Orrin W. (2004). «Rhymes and Reasons in the Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen«. The German Quarterly. 77 (1): 47–58.

- Tatar, Maria (2004). The Annotated Brothers Grimm. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-05848-2.

- Tatar, Maria (1987). The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06722-3.

- Tatar, Maria (2010). «Why Fairy Tales Matter: The Performative and the Transformative». Western Folklore. 69 (1): 55–64.

- Zipes, Jack (1994). Myth as Fairy Tale. Kentucky University Press. ISBN 978-0-8131-1890-1.

- Zipes, Jack (1988). The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90081-2.

- Zipes, Jack (2002). The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-312-29380-2.

- Zipes, Jack (1984). «The Grimm German Legends in English». Children’s Literature. 12: 162–166. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0073.

- Zipes, Jack (2014). The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of The Brothers Grimm. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16059-7.

- Zipes, Jack (2000). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860115-9.

Further reading[edit]

- Carpenter, Humphrey; Prichard, Mari (1984). The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211582-0.

- Ihms, Schmidt M. (1975). «The Brothers Grimm and their collection of ‘Kinder und Hausmärchen». Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory. 45: 41–54.

- Pullman, Philip (2012). «Introduction». In Pullman, Philip (ed.). Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02497-1.

- Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2000). A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-210019-1.

- Ellis, John M. (1983). One Fairy Story Too Many: The Brothers Grimm and their Tales. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22-6205465.

External links[edit]

The Brothers Grimm (die Brüder Grimm or die Gebrüder Grimm), Jacob (1785–1863) and Wilhelm (1786–1859), were a brother duo of German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers, and authors who together collected and published folklore. They are among the best-known storytellers of folk tales, popularizing stories such as «Cinderella» («Aschenputtel«), «The Frog Prince» («Der Froschkönig«), «Hansel and Gretel» («Hänsel und Gretel«), «Little Red Riding Hood» («Rotkäppchen«), «Rapunzel», «Rumpelstiltskin» («Rumpelstilzchen«), «Sleeping Beauty» («Dornröschen«), and «Snow White» («Schneewittchen«). Their first collection of folk tales, Children’s and Household Tales (Kinder- und Hausmärchen), began publication in 1812.

The Brothers Grimm spent their formative years in the town of Hanau in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel. Their father’s death in 1796 (when Jacob was eleven and Wilhelm was ten) caused great poverty for the family and affected the brothers many years after. Both brothers attended the University of Marburg, where they developed a curiosity about German folklore, which grew into a lifelong dedication to collecting German folk tales.

The rise of Romanticism in 19th-century Europe revived interest in traditional folk stories, which to the Brothers Grimm represented a pure form of national literature and culture. With the goal of researching a scholarly treatise on folk tales, they established a methodology for collecting and recording folk stories that became the basis for folklore studies. Between 1812 and 1857 their first collection was revised and republished many times, growing from 86 stories to more than 200. In addition to writing and modifying folk tales, the brothers wrote collections of well-respected Germanic and Scandinavian mythologies, and in 1838 they began writing a definitive German dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch) which they were unable to finish during their lifetimes.

The popularity of the Grimms’ collected folk tales has endured well. The tales are available in more than 100 translations and have been adapted by renowned filmmakers, including Lotte Reiniger and Walt Disney, with films such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. In the mid-20th century, the tales were used as propaganda by Nazi Germany; later in the 20th century, psychologists such as Bruno Bettelheim reaffirmed the value of the work in spite of the cruelty and violence in original versions of some of the tales, which were eventually sanitized by the Grimms themselves.

Biography[edit]

Early lives[edit]

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm lived in this house in Steinau from 1791 to 1796

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm were born on 4 January 1785 and 24 February 1786, respectively, in Hanau in the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, within the Holy Roman Empire (present-day Germany), to Philipp Wilhelm Grimm, a jurist, and Dorothea Grimm (née Zimmer), daughter of a Kassel city councilman.[1] They were the second- and third-eldest surviving siblings in a family of nine children, three of whom died in infancy.[2][a][3] In 1791 the family moved to the countryside town of Steinau during Philipp’s employment there as a district magistrate (Amtmann). The family became prominent members of the community, residing in a large home surrounded by fields. Biographer Jack Zipes writes that the brothers were happy in Steinau and «clearly fond of country life».[1] The children were educated at home by private tutors, receiving strict instruction as Lutherans, which instilled in both a lifelong religious faith.[4] Later, they attended local schools.[1]

In 1796 Philipp Grimm died of pneumonia, causing great poverty for the large family. Dorothea was forced to relinquish the brothers’ servants and large house, depending on financial support from her father and sister, who was then the first lady-in-waiting at the court of William I, Elector of Hesse. Jacob was the eldest living son, forced at age 11 to quickly assume adult responsibilities (shared with Wilhelm) for the next two years. The two brothers then followed the advice of their grandfather, who continually exhorted them to be industrious.[1]

The brothers left Steinau and their family in 1798 to attend the Friedrichsgymnasium in Kassel, which had been arranged and paid for by their aunt. By then they were without a male provider (their grandfather died that year), forcing them to rely entirely on each other and become exceptionally close. The two brothers differed in temperament—Jacob was introspective and Wilhelm was outgoing (although he often suffered from ill health)—but they shared a strong work ethic and excelled in their studies. In Kassel they became acutely aware of their inferior social status relative to «high-born» students who received more attention. Each brother graduated at the head of his class: Jacob in 1803 and Wilhelm in 1804 (he missed a year of school due to scarlet fever).[1][5]

Kassel[edit]

After graduation from the Friedrichsgymnasium, the brothers attended the University of Marburg. The university was small with about 200 students, and there they became painfully aware that students of lower social status were not treated equally. They were disqualified from admission because of their social standing and had to request dispensation to study law. Wealthier students received stipends, but the brothers were excluded even from tuition aid. Their poverty kept them from student activities or university social life. However, their outsider status worked in their favor and they pursued their studies with extra vigor.[5]

Inspired by their law professor, Friedrich von Savigny, who awakened in them an interest in history and philology, the brothers studied medieval German literature.[6] They shared Savigny’s desire to see the unification of the 200 German principalities into a single state. Through Savigny and his circle of friends—German romantics such as Clemens Brentano and Ludwig Achim von Arnim—the Grimms were introduced to the ideas of Johann Gottfried Herder, who thought that German literature should revert to simpler forms, which he defined as Volkspoesie (natural poetry)—as opposed to Kunstpoesie (artistic poetry).[7] The brothers dedicated themselves with great enthusiasm to their studies, about which Wilhelm wrote in his autobiography, «the ardor with which we studied Old German helped us overcome the spiritual depression of those days.»[8]

Jacob was still financially responsible for his mother, brother, and younger siblings in 1805, so he accepted a post in Paris as a research assistant to von Savigny. On his return to Marburg he was forced to abandon his studies to support the family, whose poverty was so extreme that food was often scarce, and take a job with the Hessian War Commission. In a letter written to his aunt at this time, Wilhelm wrote of their circumstances: «We five people eat only three portions and only once a day».[6]

Jacob found full-time employment in 1808 when he was appointed court librarian to the King of Westphalia and went on to become a librarian in Kassel.[2] After their mother’s death that year, he became fully responsible for his younger siblings. He arranged and paid for his brother Ludwig’s studies at art school and for Wilhelm’s extended visit to Halle to seek treatment for heart and respiratory ailments, following which Wilhelm joined Jacob as librarian in Kassel[1] At Brentano’s request, the brothers had begun collecting folk tales in a cursory manner in 1807.[9] According to Jack Zipes, at this point «the Grimms were unable to devote all their energies to their research and did not have a clear idea about the significance of collecting folk tales in this initial phase.»[1]

During their employment as librarians—which paid little but afforded them ample time for research—the brothers experienced a productive period of scholarship, publishing books between 1812 and 1830.[10] In 1812 they published their first volume of 86 folk tales, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, followed quickly by two volumes of German legends and a volume of early literary history.[2] They went on to publish works about Danish and Irish folk tales (and also Norse mythology), while continuing to edit the German folk tale collection. These works became so widely recognized that the brothers received honorary doctorates from universities in Marburg, Berlin, and Breslau (now Wrocław).[10]

Göttingen[edit]

On 15 May 1825 Wilhelm married Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, a pharmacist’s daughter and childhood friend who had given the brothers several tales.[11] Jacob never married but continued to live in the household with Wilhelm and Dortchen.[12] In 1830 both brothers were overlooked when the post of chief librarian came available, which disappointed them greatly.[10] They moved the household to Göttingen in the Kingdom of Hanover, where they took employment at the University of Göttingen—Jacob as a professor and head librarian and Wilhelm as a professor.[2]

During the next seven years the brothers continued to research, write, and publish. In 1835 Jacob published the well-regarded German Mythology (Deutsche Mythologie); Wilhelm continued to edit and prepare the third edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen for publication. The two brothers taught German studies at the university, becoming well-respected in the newly established discipline.[12]

In 1837 the brothers lost their university posts after joining the rest of the Göttingen Seven in protest. The 1830s were a period of political upheaval and peasant revolt in Germany, leading to the movement for democratic reform known as Young Germany. The brothers were not directly aligned with the Young Germans, but they and five of their colleagues reacted against the demands of Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, who in 1837 dissolved the parliament of Hanover and demanded oaths of allegiance from civil servants—including professors at the University of Göttingen. For refusing to sign the oath, the seven professors were dismissed and three were deported from Hanover—including Jacob, who went to Kassel. He was later joined there by Wilhelm, Dortchen, and their four children.[12]

Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, c. 1837

The brothers were without income and again in extreme financial difficulty in 1838, so they began what would become a lifelong project—the writing of a definitive dictionary, the German Dictionary (Deutsches Wörterbuch)—whose first volume was not published until 1854. The brothers again depended on friends and supporters for financial assistance and influence in finding employment.[12]

Berlin and later years[edit]

In 1840, von Savigny and Bettina von Arnim appealed successfully to Frederick William IV of Prussia on behalf of the brothers, who were offered posts at the University of Berlin. In addition to teaching posts, the Academy of Sciences offered them stipends to continue their research. Once they had established their household in Berlin they directed their efforts towards the work on the German dictionary and continued to publish their research. Jacob turned his attention to researching German legal traditions and the history of the German language, which was published in the late 1840s and early 1850s; meanwhile Wilhelm began researching medieval literature while editing new editions of Hausmärchen.[10]

The graves of the Brothers Grimm in Schöneberg, Berlin (St. Matthäus Kirchhof Cemetery)

After the revolutions of 1848 in the German states the brothers were elected to the civil parliament. Jacob became a prominent member of the National Assembly at Mainz.[12] Their political activities were short-lived, however, as their hope for a unified Germany dwindled and their disenchantment grew. In the late 1840s Jacob resigned his university position and published The History of the German Language (Geschichte der deutschen Sprache). Wilhelm continued at his university post until 1852. After retiring from teaching the brothers devoted themselves to the German Dictionary for the rest of their lives.[12] Wilhelm died of an infection in Berlin on 16 December 1859,[13] and Jacob, deeply upset at his brother’s death, became increasingly reclusive. He continued working on the dictionary until his own death on 20 September 1863. Zipes writes of the Grimms’ dictionary, and of their very large body of work: «Symbolically the last word was Frucht (fruit).»[12]

Collaborations[edit]

Children’s and Household Tales[edit]

Background[edit]

The Grimms defined «Little Red Riding Hood», shown here in an illustration by Arthur Rackham, as representative of a uniquely German tale, although it existed in various versions and regions[14]

The rise of romanticism, romantic nationalism, and trends in valuing popular culture in the early 19th century revived interest in fairy tales, which had declined since their late 17th-century peak.[15] Johann Karl August Musäus published a popular collection of tales called Volksmärchen der Deutschen between 1782 and 1787;[16] the Grimms aided the revival with their folklore collection, built on the conviction that a national identity could be found in popular culture and with the common folk (Volk). They collected and published their tales as a reflection of German cultural identity. In the first collection, though, they included Charles Perrault’s tales, published in Paris in 1697 and written for the literary salons of an aristocratic French audience. Scholar Lydie Jean says that Perrault created a myth that his tales came from the common people and reflected existing folklore to justify including them—even though many of them were original.[15]

The brothers were directly influenced by Brentano and von Arnim, who edited and adapted the folk songs of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn or cornucopia).[16] They began the collection with the purpose of creating a scholarly treatise of traditional stories, and of preserving the stories, as they had been handed from generation to generation—a practice that was threatened by increased industrialization.[17] Maria Tatar, professor of German studies at Harvard University, explains that it is precisely the handing from generation to generation and the genesis in the oral tradition that gives folk tales an important mutability. Versions of tales differ from region to region, «picking up bits and pieces of local culture and lore, drawing a turn of phrase from a song or another story, and fleshing out characters with features taken from the audience witnessing their performance.»[18]

However, as Tatar explains, the Grimms appropriated stories as being uniquely German, such as «Little Red Riding Hood», which had existed in many versions and regions throughout Europe, because they believed that such stories were reflections of Germanic culture.[14] Furthermore, the brothers saw fragments of old religions and faiths reflected in the stories, which they thought continued to exist and survive through the telling of stories.[19]

Methodology[edit]

When Jacob returned to Marburg from Paris in 1806, their friend Brentano sought the brothers’ help in adding to his collection of folk tales, at which time the brothers began to gather tales in an organized fashion.[1] By 1810 they had produced a manuscript collection of several dozen tales, written after inviting storytellers to their home and transcribing what they heard. These tales were heavily modified in transcription; many had roots in previously written sources.[20] At Brentano’s request, they printed and sent him copies of the 53 tales that they collected for inclusion in his third volume of Des Knaben Wunderhorn.[2] Brentano either ignored or forgot about the tales, leaving the copies in a church in Alsace where they were found in 1920 and became known as the Ölenberg manuscript. It is the earliest extant version of the Grimms’ collection and has become a valuable source to scholars studying the development of the Grimms’ collection from the time of its inception. The manuscript was published in 1927 and again in 1975.[21]

The brothers gained a reputation for collecting tales from peasants, although many tales came from middle-class or aristocratic acquaintances. Wilhelm’s wife, Henriette Dorothea (Dortchen) Wild, and her family, with their nursery maid, told the brothers some of the more well-known tales, such as «Hansel and Gretel» and «Sleeping Beauty».[22] Wilhelm collected some tales after befriending August von Haxthausen, whom he visited in 1811 in Westphalia where he heard stories from von Haxthausen’s circle of friends.[23] Several of the storytellers were of Huguenot ancestry, telling tales of French origin such as those told to the Grimms by Marie Hassenpflug, an educated woman of French Huguenot ancestry,[20] and it is probable that these informants were familiar with Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé (Stories from Past Times).[15] Other tales were collected from Dorothea Viehmann, the wife of a middle-class tailor and also of French descent. Despite her middle-class background, in the first English translation she was characterized as a peasant and given the name Gammer Gretel.[17] At least one tale, Gevatter Tod (Grim Reaper), was provided by composer Wilhelmine Schwertzell,[24] with whom Wilhelm had a lengthy correspondence.[25]

Stories such as «Sleeping Beauty», shown here in a Walter Crane illustration, had been previously published and were rewritten by the Brothers Grimm[15]

According to scholars such as Ruth Bottigheimer and Maria Tatar, some of the tales probably originated in written form during the medieval period with writers such as Straparola and Boccaccio, but were modified in the 17th century and again rewritten by the Grimms. Moreover, Tatar writes that the brothers’ goal of preserving and shaping the tales as something uniquely German at a time of French occupation was a form of «intellectual resistance», and in so doing they established a methodology for collecting and preserving folklore that set the model followed later by writers throughout Europe during periods of occupation.[17][26]

Writing[edit]

From 1807 onwards, the brothers added to the collection. Jacob established the framework, maintained through many iterations; from 1815 until his death, Wilhelm assumed sole responsibility for editing and rewriting the tales. He made the tales stylistically similar, added dialogue, removed pieces «that might detract from a rustic tone», improved the plots, and incorporated psychological motifs.[23] Ronald Murphy writes in The Owl, the Raven, and the Dove that the brothers, and in particular Wilhelm, also added religious and spiritual motifs to the tales. He believes that Wilhelm «gleaned» bits from old Germanic faiths, Norse mythology, Roman and Greek mythology, and biblical stories that he reshaped.[19]

Over the years, Wilhelm worked extensively on the prose; he expanded and added detail to the stories to the point that many of them grew to twice the length that they were in the earliest published editions.[27] In the later editions Wilhelm polished the language to make it more enticing to a bourgeois audience, eliminated sexual elements, and added Christian elements. After 1819 he began writing original tales for children (children were not initially considered the primary audience) and adding didactic elements to existing tales.[23]

Some changes were made in light of unfavorable reviews, particularly from those who objected that not all the tales were suitable for children because of scenes of violence and sexuality.[28] He worked to modify plots for many of the stories; for example, «Rapunzel» in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen clearly shows a sexual relationship between the prince and the girl in the tower, which he edited out in subsequent editions.[27] Tatar writes that morals were added (in the second edition a king’s regret was added to the scene in which his wife is to be burned at the stake) and often the characters in the tale were amended to appear more German: «every fairy (Fee), prince (Prinz) and princess (Prinzessin)—all words of French origin—was transformed into a more Teutonic-sounding enchantress (Zauberin) or wise woman (weise Frau), king’s son (Königssohn), king’s daughter (Königstochter).»[29]

Themes and analysis[edit]

The Grimms’ legacy contains legends, novellas, and folk stories, the vast majority of which were not intended as children’s tales. Von Armin was concerned about the content of some of the tales—such as those that showed children being eaten—and suggested adding a subtitle to warn parents of the content. Instead the brothers added an introduction with cautionary advice that parents steer children toward age-appropriate stories. Despite von Armin’s unease, none of the tales were eliminated from the collection in the brothers’ belief that all the tales were of value and reflected inherent cultural qualities. Furthermore, the stories were didactic in nature at a time when discipline relied on fear, according to scholar Linda Dégh, who explains that tales such as «Little Red Riding Hood» and «Hansel and Gretel» were written as «warning tales» for children.[30]

«Hansel and Gretel», illustrated by Arthur Rackham, was a «warning tale» for children[30]

The stories in Kinder- und Hausmärchen include scenes of violence that have since been sanitized. For example, in the Grimms’ original version of «Snow White», the Queen is Little Snow White’s mother, not her stepmother, yet even so she orders her Huntsman to kill Snow White (her biological daughter) and bring home the child’s lungs and liver so that she can eat them; the story ends with the Queen dancing at Snow White’s wedding, wearing a pair of red-hot iron shoes that kill her.[31] Another story («The Goose Girl») has a servant being stripped naked and pushed into a barrel «studded with sharp nails» pointing inwards and then rolled down the street.[13] The Grimms’ version of «The Frog Prince» describes the princess throwing the frog against a wall instead of kissing him. To some extent the cruelty and violence may have been a reflection of medieval culture from which the tales originated, such as scenes of witches burning, as described in «The Six Swans».[13]