Брейк-данс – зрелищный танец, сочетающий в себе удивительную пластику и сложность акробатических трюков. Основные его свойства — импровизация, оригинальность и зажигательность.

Брейк-данс представляет танцевальное направление хип-хоп культуры и включает в себя множество стилей. Для его исполнения необходимы хорошая координация, физическая выносливость, чувство ритма и гибкость. В движениях, включающих импровизационные переходы от оригинальной пластики к акробатическим элементам с вращениями на голове, прыжками на руках и оборотами вокруг своего тела, танцор не только демонстрирует мастерство, но и выплескивает свои эмоции и энергию.

История возникновения танца

Существует интересная легенда, повествующая о том, что в начале 70-х годов в Америке выходцы из бедных кварталов Нью-Йорка, привыкшие с оружием в руках выяснять отношения, решили продемонстрировать свою силу и ловкость более оригинально. Противники выходили по очереди друг против друга и показывали свои умения и намерения на языке движений.

В основе любой легенды лежат реальные факты, поэтому можно однозначно сказать, что брейк-данс зародился как уличный танец и только в процессе своего развития стал исполнительным искусством. Танцоры брейк-данса редко пользуются этим названием, предпочитая «брейкинг» или «би-боинг». Термин «брейкдансинг» создан искусственно и использовался в СМИ. Необходимо это было, чтобы отделить разные направления, включающиеся в понятие брейкинга.

Брейк-данс преимущественно исполняют представители мужского пола, так как девушкам в силу физических особенностей обучаться ему сложно, хотя многие би-гёрлз (девушки, танцующие брейк-данс) также достигают поразительных успехов.

В своем прогрессе брейк-данс прошел несколько этапов, включающих как заимствование из других танцев, вошедших своими элементами в брейк-данс, так и собственно развитие би-боинга. Так можно упомянуть стиль Good Foot, в котором впервые появились ломаные движения и элементы вращения на земле. Не стоит забывать про влияние пуэрториканцев, разработавших и внедривших много акробатических трюков. «Участвовали» в формировании брейк-данса и элементы кунг фу, и ритмические составляющие, пришедшее от африканских иммигрантов и т.д.

Безусловно, развитию брейк-данса способствовали баттлы – состязания брейкеров, в которых очень важно было поразить противника как можно большей изощренностью комбинаций движений и трюков. Танцоры стали объединяться в команды, разрабатывая собственные стили и оригинальные движения.

В настоящее время брейк-данс распространен по всему миру, существуют многочисленные школы брейк-данса, проводятся чемпионаты и фестивали.

Стили

Условно брейк-данс делится на верхний и нижний. Деление это формальное, потому что танец включает комбинации элементов обоих уровней.

Элементы верхнего брейк-данса требуют больше пластики и импровизационных ходов, тогда как нижний – физической подготовки и акробатических навыков.

К верхнему брейк-дансу относят множество направлений, но основными являются:

Animation — cтиль, в котором танцоры имитируют прерывистые движения анимированных кукол.

Waving — движения тела, которые визуально напоминают волны.

King tut — танец, в котором движения конечностей должны осуществляться под прямым углом.

Slowmo — стиль, похожий на замедленное воспроизведение видеосъемки.

В свою очередь нижний брейк-данс включает следующие основные стили:

Флай (flare/delasal) — представляет собой передвижение ног по кругу со сменой рук.

Вращения на голове (headspin, drill)

Вращения на спине или лопатках (backspin, windmill)

Стилей брейк-данса множество, и чем больше их в арсенале танцора, тем больше у него возможностей для успешных выступлений на баттле.

Особенности брейк-данса

Брек-данс танцуют под быструю музыку с сильными ударными, чаще всего используются музыкальные жанры:

соул

фанк

рэп

Несмотря на распространение обучающих видеофильмов, учиться брейк-дансу лучше в школе под руководством опытного тренера.

История брейк-данса началась в конце 60-х годов в Нью-Йорке, в одном из самых бедных районов — Бронксе.

В это время электронная музыка обретала популярность среди молодых танцоров, которые использовали элементы вращения на земле

и называли это направление Good Foot.

Название Би-бои и Би-боинг появилось благодаря диджею Kool Herc, B-boys -сокращенное название

Break boys — танцоры ломаного бита.

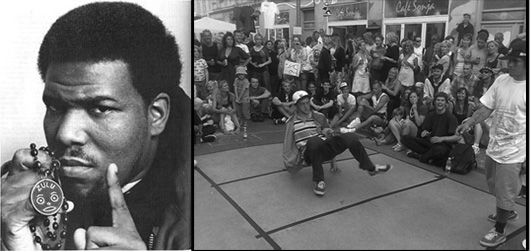

Dj Kool Herc

Чуть позже, в 70-е легендарный рэп-певец Afrika Bambaata впервые предложил устраивать соревнования между нью-йоркскими танцорами

на постеленном картонном покрытии.

Afrika Bambaata

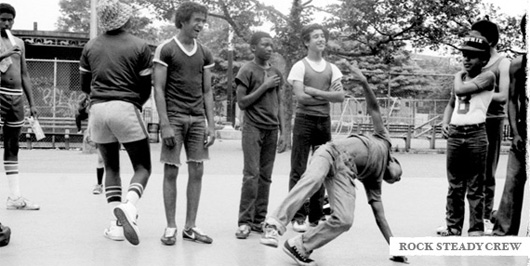

В 1977 организуется молодая команда Rock Steady Crew, участники которых сделали огромный вклад в виде новых движений

который сейчас стали базовыми в брейк дансе, а в 1980-х они в своем мировом турне показали новый стиль танца всему миру.

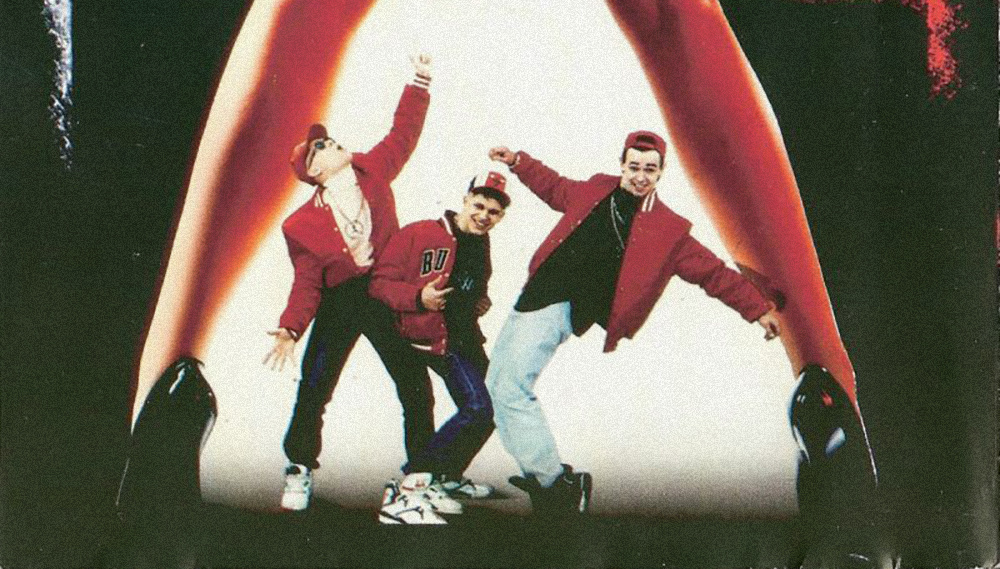

Rock Steady Crew, 1977

Брейк данс в СССР

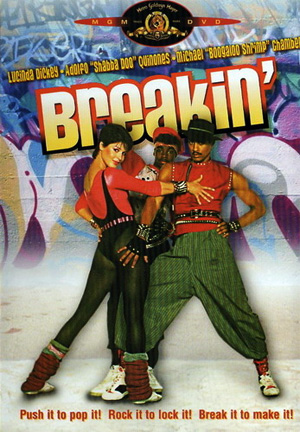

В 1985 году после фильма «Breakin’» брейк данс начинает своё восхождение в Советском союзке.

Обложка фильма Breakin’

Алексей Козлов является организатором первой постановки в стиле брейк данс на территории СССР, с этого момента начинается

танцевальный бум, молодые танцоры пытаются разучивать новый интересный стиль танца.

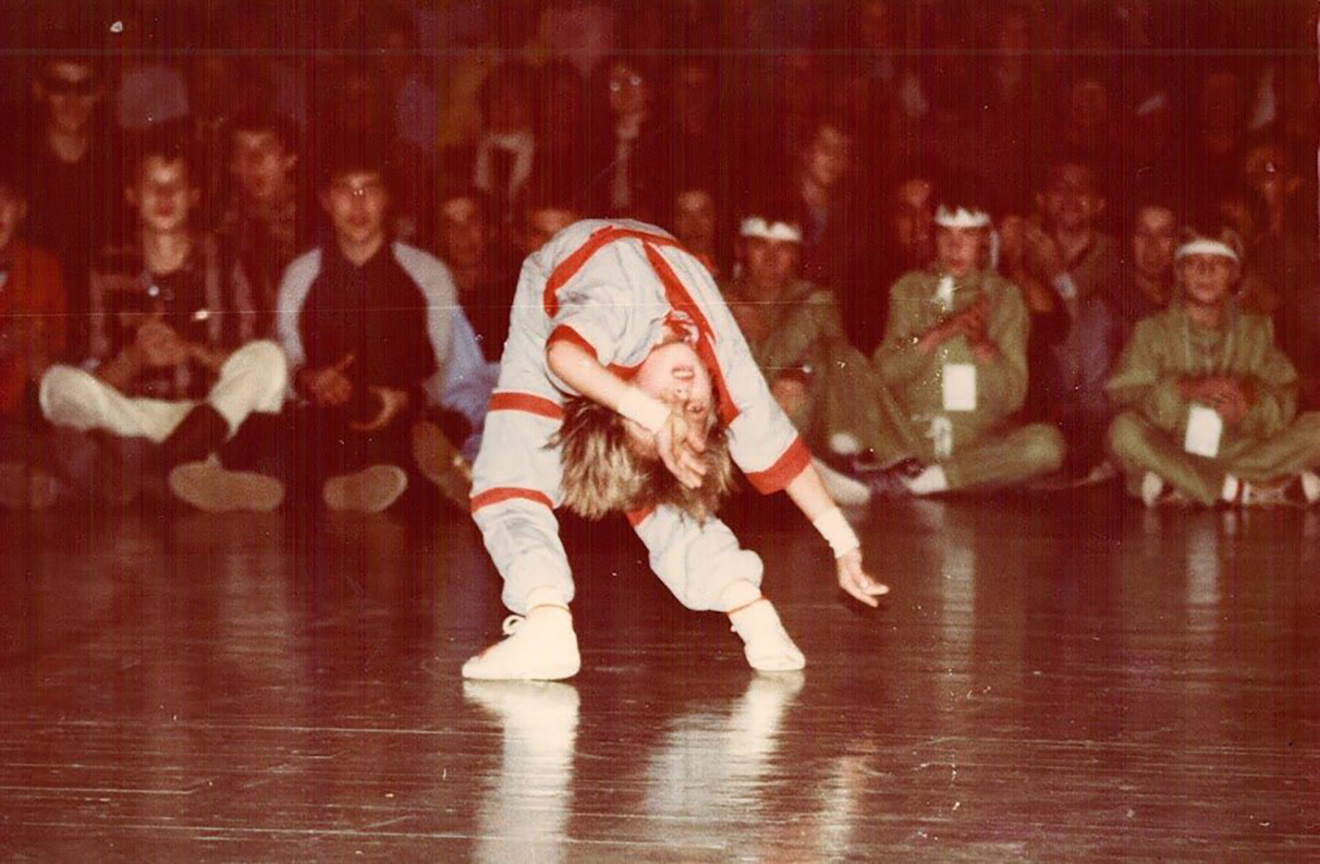

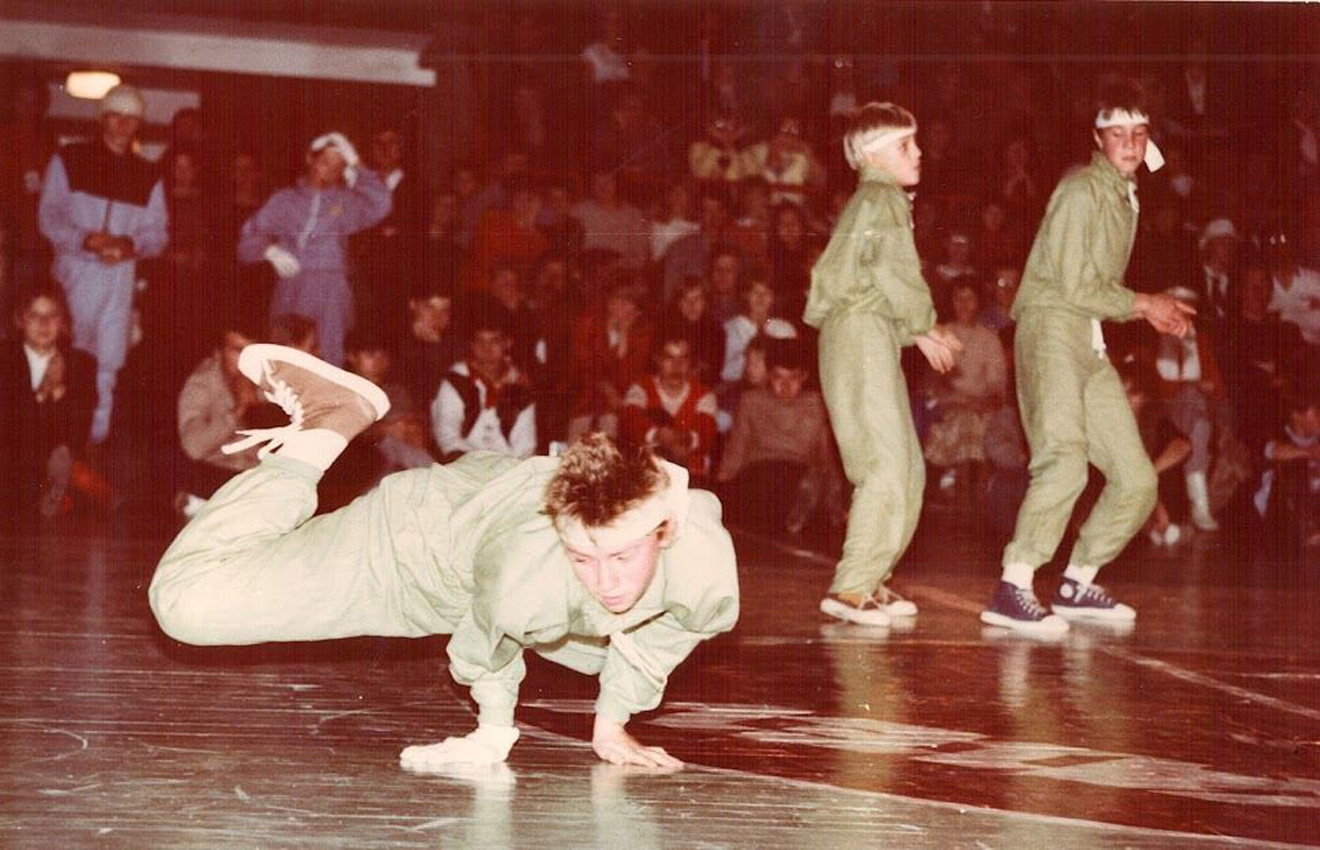

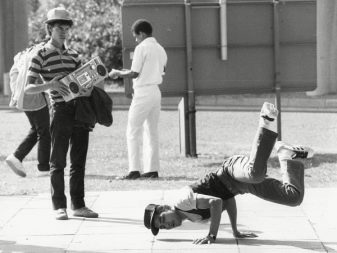

Первое выступление в стиле Брейк-данс — 1985 год, Москва

К 1987-88 брейк данс становится самым массовым танцевальным движением, но информационный вакуум тормозит развитие танцоров.

Таким образом только на территории СССР появились так называемые подстили «верхний брейк данс» и «нижний брейк данс».

В то время танцам учились самоучки исключительно на фильмах из зарубежья и заимствовали движения из других танцевальных направлений.

В 1986 году выходит популярный фильм «Курьер» с сценами танцев брейк-данса:

Сцена брейк-данса из фильма «Курьер»

90-е

Развал советского союза открывает возможности для получения новой информации с запада, но экономика и политические события значительно тормозит развитие танца.

В СНГ активно нарастает индустрия хип-хопа, и как следствие только к концу 90-х происходит повторное оживление брейк-данса.

Наше время

С 2004 года открывается масштабное ежегодное международное соревнование Red Bull BC One, в нем принимают

участие 16 лучших би-боев мира. Это мероприятие выводит уровень соревнований по брейк дансу на новый уровень —

специально организованная круглая сцена с камерами, которые снимают танцевальную баталию со всех ракурсов.

В 2011 году чемпионат мира по брейк дансу прибыл в Москву, поощряя развитие танцоров мастер-классами.

Red Bull BC One

8 июля 2022История, Антропология

Краткая история советского брейк-данса

Что такое советский брейк-данс и когда он появился? Как выглядели первые танцевальные баттлы? Почему в советское время стиль в итоге угас? И как он повлиял на зарождение русского рэпа? Рассказываем об истории советского брейк-данса

Уличный танец — это один из элементов хип-хоп-культуры, зародившейся в рабочей среде Нью-Йорка в 1970-х годах. Основополагающий стиль уличного хип-хоп-танца — брейкинг Диджей Лэнс Тейлор, более известный под псевдонимом Afrika Bambaataa, первым определил пять составляющих хип-хоп-культуры: эмсиинг (рэп), диджеинг, брейкинг, граффити и знание (философия).. Именно с него началась история развития жанра в СССР.

Брейкинг привезли в СССР в 1980-е годы, а пик популярности стиля пришелся на 1985–1990 годы. Этот период назовут первой волной брейкинга в России. Развитие танца совпало с перестройкой и было таким же стремительным. За короткое время брейкинг прошел путь от закрытых квартир до крупных фестивалей и кино.

Однако немногие прочили этому танцевальному стилю долгую жизнь: его считали привезенной модой, не имеющей под собой фундамента для дальнейшего развития. С распадом СССР интерес к стилю действительно угас. В Россию брейкинг вернулся только в 2000-х годах.

1980–1982

Олимпиада-80 и новая мода

Летние Олимпийские игры 1980 года приоткрыли железный занавес, и в Россию проникла американская культура: на прилавках появились пепси-кола, фанта, а в моду вошли кроссовки. Английский язык перестал быть профессиональным качеством и стал атрибутом хорошего гуманитарного образования. Все чаще появлялись переводные книжки и англицизмы в речи.

1983

Русский рок и первые видеокассеты

В некоторых домах появились зарубежные магнитофоны и видеокассеты. А голливудские боевики вроде «Рокки» стали альтернативой Центральному телевидению. 1983 год, помимо прочего, и время расцвета русского рока: в мае прошел первый фестиваль в Ленинградском рок-клубе, и неформальные объединения начали становиться нормой.

1984

Завезенный брейк-данс, крашеные кроссовки и аэробика

Это время циркового искусства и пластического театра. Основными героями 1984 года были театр клоунады «Лицедеи» и Вячеслав Полунин. Тогда же началось массовое производство первого отечественного магнитофона «Электроника ВМ-12» — он продавался повсеместно. Теперь видео можно было смотреть дома.

Брейкинг постепенно проникал в семьи дипломатов, работников посольств и Министерства внешней торговли: они знакомились с танцем за границей. Остальные копировали движения и трюки героев первых американских фильмов о брейк-дансе: «Breakin’» (1984), «Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo» (1984) и «Beat Street» (1984).

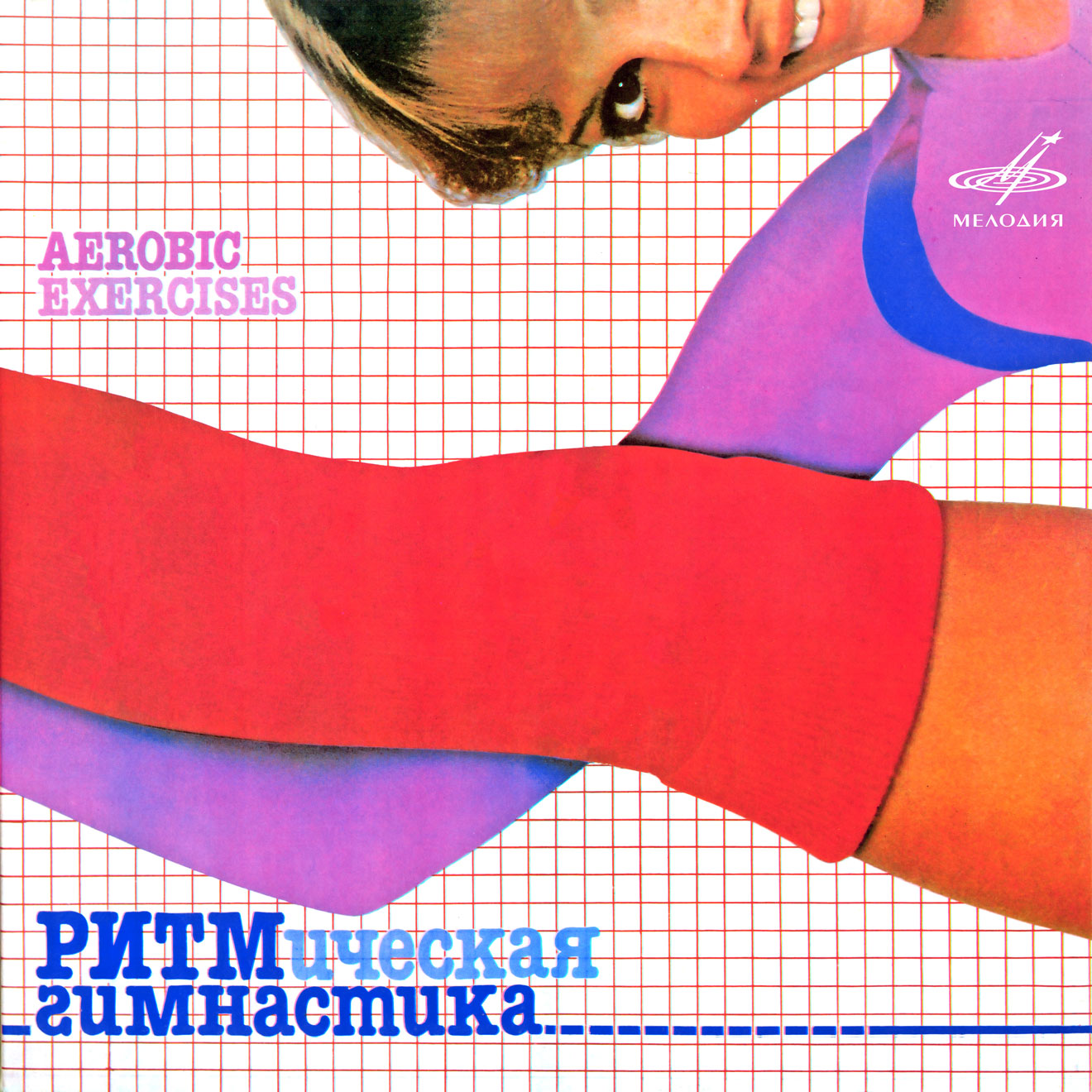

Также появился запрос на бытовые танцевальные практики: среди женщин стала невероятно популярна аэробика. Звукозаписывающая фирма «Мелодия» даже выпустила специальный саундтрек — виниловую пластинку для занятий ритмической гимнастикой. Так танец и телесная гимнастика стали нормой быта.

Молодое поколение стремилось к индивидуальности, начала развиваться подростковая мода. Те, у кого была возможность, получали одежду из-за границы — в основном это были дети обеспеченных родителей. Другие незаконно скупали ее у фарцовщиков Фарцовщики — частные торговцы, которые незаконно скупали у иностранцев вещи и валюту, а затем продавали их.. Те, у кого не было такой возможности, выкраивали и шили одежду из маминых халатов, кальсон и доступной ткани по лекалам западных образцов.

Самый важный атрибут уличных танцоров — это, конечно, кроссовки. В 1984 году в продаже были модели китайского производства, в основном черные и коричневые. Но для танца нужны яркие цвета, поэтому многие красили кроссовки сами, по аналогии с джинсами.

1985

Брейк-данс на Арбате и обживание домов культуры

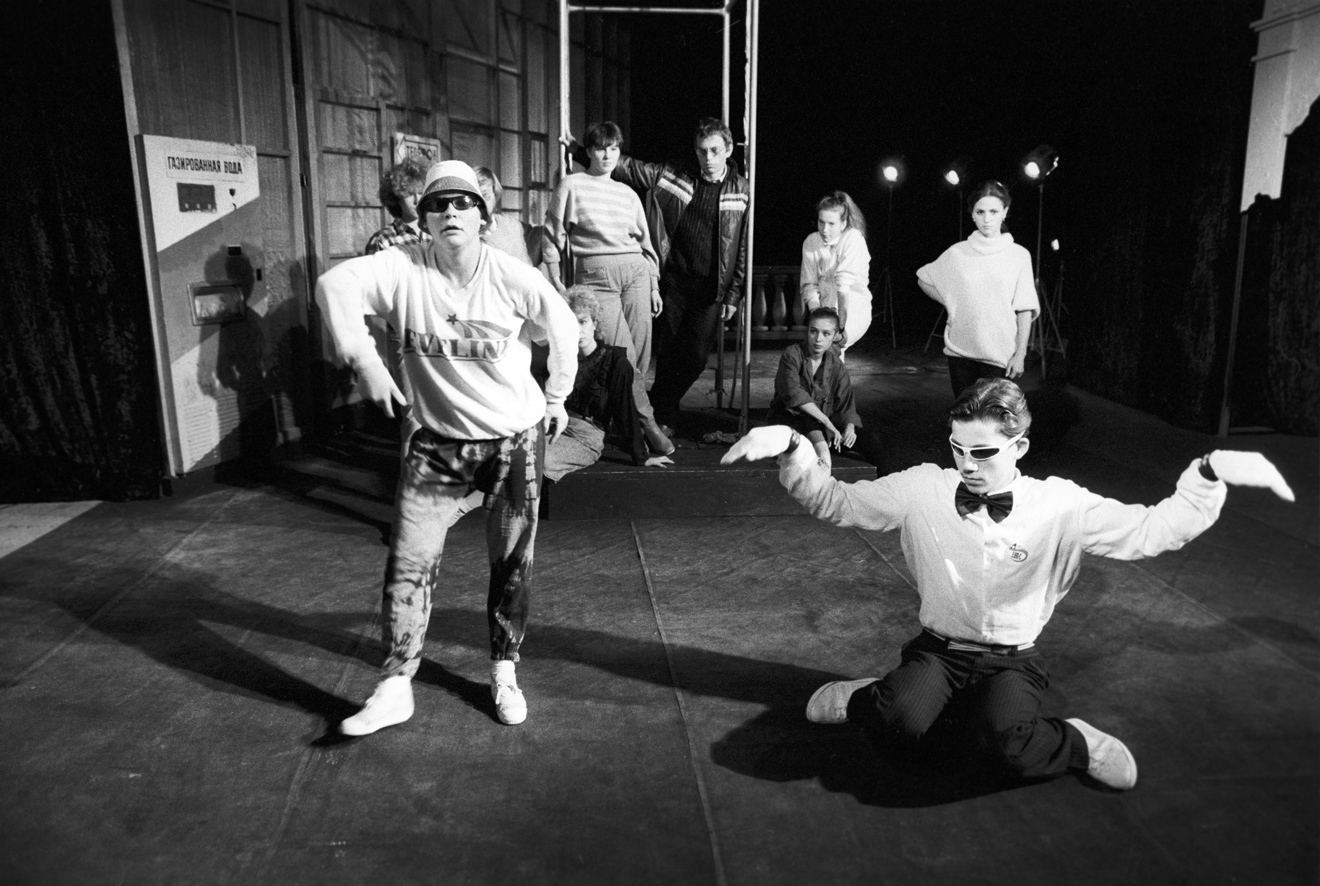

В 1985 году брейкинг перестал быть танцем привилегированной молодежи и вышел из квартир в спортзалы и на танцплощадки. Тогда же появились первые профессиональные танцевальные коллективы. Известный саксофонист и джазмен Алексей Козлов создал «Брейк-арсенал» — танцевальный коллектив, образовавшийся на основе музыкальной группы «Арсенал». «Брейк-арсенал» представил стиль публике и постепенно его популяризировал.

Помимо «Брейк-арсенала», к важным коллективам того времени можно отнести «Магический круг», «Меркурий», «Зеркало» и «Вектор».

Советских детей, читавших братьев Стругацких и Кира Булычева, очень привлекла эстетика афрофутуризма Афрофутуризм — направление в литературе и искусстве на пересечении культуры африканской диаспоры с наукой и технологиями., присущая фанку и брейк-дансу. Сказалось и влияние школы мимов, которая на тот момент была очень популярна. Публику завораживали странные футуристические движения танцоров: они двигались как роботы, делали волны и лунные дорожки. Некоторые пытались за ними повторять и искали возможность научиться танцевать так же.

Чтобы учиться брейк-дансу и отрабатывать движения, нужны большое пространство и зеркала. Танцоры постепенно обжили дворцы и дома культуры. Впервые курсы по брейкингу организовали в московском дворце культуры «Правда», ими руководил цирковой режиссер Валентин Гнеушев. Школа «Правда», названная в честь дворца культуры, в котором располагалась, стала одной из самых развитых: ее ученики в будущем представляли Россию на всесоюзных чемпионатах и показывали брейк-данс в кино.

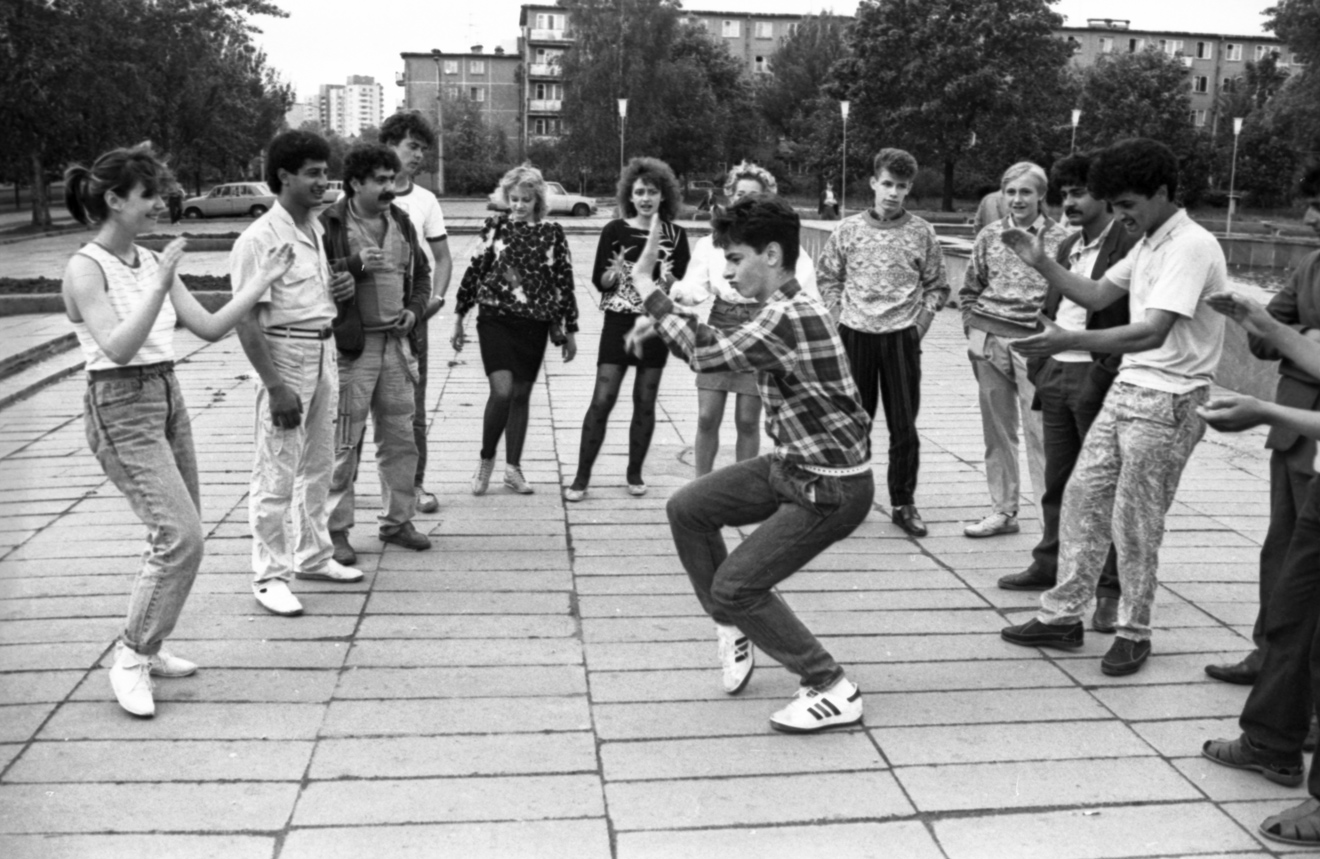

Первые брейк-тусовки, на которых танцовщики делились новыми движениями, собирались в молочном кафе В молочном кафе подавали блюда и напитки из молочных продуктов, например молочные коктейли и мороженое. «У фонтана» (его называли просто «Молоко»). Это было первое постоянно действующее молодежное кафе в столице.

«„Молоко“ было местом для действительно модного времяпровождения, где собирался широкий спектр молодежи: от утюгов-фарцовщиков до эстрадных исполнителей. Макаревич сидел там время от времени. Сергей Пенкин, Володя Пресняков давали там одни из первых своих концертов. Даже один из новогодних огоньков там снимали. Место было модным, и там мы впервые увидели выступление группы „Вектор“ Володи Рацкевича. То выступление произвело неизгладимое впечатление. Мысли „я тоже так хочу“ были не только у меня. С этого дня наши студийцы стали ломать свои тела под брейк» Фрагмент из интервью Милы Максимовой.

М. Бастер. Хулиганы-80. М., 2009..

Кроме того, в 1985 году брейкинг вышел на улицы. Этому способствовало открытие первой пешеходной улицы, так называемой «витрины перестройки», — Арбата. Его сразу оккупировали уличные музыканты, цирковые артисты и брейк-танцоры. На Арбате в том числе развивался и уникальный российский стиль — «верхний брейк-данс». Причина его появления — неправильная трактовка западных терминов. То, что у нас называли верхним брейком, по сути, являлось стилями electric boogie Электрик-буги — стиль, сочетающий плавность в движении и иллюзорность форм (имитация волн, движений робота), вдохновленный эстетикой афрофутуризма и музыкальной средой Нью-Йорка (фанком, электрофанком и другими жанрами). и locking Локинг — социальный танец с характерными яркими образами и авторской манерой группы The Lockers, исполняемый под фанк-музыку. Движения в танце прерываются остановками в определенных позициях, после которых танцовщик продолжает двигаться в своем темпе.. Российские танцоры рассуждали примерно так: если ты крутишься на полу, выполняешь элементы футворка От английского footwork — «движения ногами»., ты танцуешь нижний брейк-данс, как только ты поднимаешься вверх, пускаешь по рукам волны, имитируешь робота или фараона Тутанхамона (king-tut, или tutting), это уже верхний брейк-данс. Можно сказать, что термин «верхний брейк-данс» появился для удобства классификации и разделения стилей.

Поначалу верхний и нижний брейк-данс были тесно связаны друг с другом. Нередко исполнители нижнего стиля вставляли в свой танец элементы верхнего. Но по мере развития все усложнялось: появлялись люди, которых интересовал исключительно верхний или нижний стиль. Происходило постепенное разделение на так называемые «верха» и «низа». Верхний брейк-данс просуществовал в России до 2000-х годов. Его долголетие связано с тем, что первое поколение российских танцоров («олдскульщики») не захотело переучиваться и терять свой статус:

«Дело в том, что у нас страна была закрыта до 91–92 года, информация в Россию не втекала и не вытекала вообще. Поэтому, что до нас дошло в 86–87 годах — танцоры на том и начали расти, и вырос свой доморощенный поппинг, локинг — свои доморощенные верха. <…> Когда же они заинтересовались тем, что существует в мире, когда открылся занавес перед Западом, они увидели, что там все изменилось так, что надо начинать учиться с нуля, если хочешь танцевать так же. А у нас не было этих истоков, баз, корней — не знали, откуда дерево выросло. Вот и решили строить дом без фундамента. А дом без фундамента рушится от первого же ветра. Нужен глубокий фундамент: чем он глубже, тем больше и лучше баз ты сможешь на нем выстроить. А напрягаться с фундаментом — с нуля начинать — не хотелось, потому что тут дело статуса: они олдскульщики и их все уважают. И чтобы не терять престиж в глазах учеников, они не признавали западных тенденций. В результате остались там, в том веке, в том тысячелетии» «Я приезжаю в Россию, чтобы просвещать» // iDance.ru. 4 апреля 2007 года..

Сейчас феномен «верхнего брейка» осмысляют иначе:

«Вот это желание научиться танцевать с нуля — как раз свойство молодежи в государствах-перифериях. Ребята хотят научиться делать что-то как в центре (в нашем случае в США), делать „правильную“ и „одобряемую“ версию искусства. А ребята постарше понимают, что их искусство — это их мастерство, они не готовы отказываться от своих взглядов на движение. И многое из этих взглядов уже в конце десятых снова вызывало неподдельный интерес — тот же Савенков сейчас очень актуален.

Что произошло в середине 2000-х — появилась пассионарная молодежь (как мы с Лешей Буги и Андреем Слайдом), которая не смогла оценить самобытность нашей советской школы (в моем случае в погоне за западным „одобрением“ я не мог оценить нашу культуру, к сожалению, это приходит с годами).

Олдскульщики и были тем фундаментом. В Европе, которая не была страной периферии по культуре, „кассетные“ олдскульщики вполне выжили и развили свои стили, интегрировали в современную фанк-культуру. Ребята типа Нильса (b-boy Storm) и Стина (Steen) выступают в театрах и делают топовую хореографию и никто не говорит, что она „неверная“» Фрагмент из интервью Матвея Лебедева (Matt Fownk). Записала Ольга Крупник. Апрель 2022 года..

1986

Видеоклипы, баттлы и фильм «Курьер»

В декабре 1986 года вышел фильм Карена Шахназарова «Курьер». Он раскрывал тему конфликта поколений, а также пытался сформулировать новые идеалы и принципы молодых людей эпохи перестройки. «Курьер» стал одним из лидеров проката 1987 года, а позднее и лучшим фильмом по результатам опроса журнала «Советский экран». Это была легендарная картина для российского брейк-данс-сообщества. В финальной сцене «Курьера» уличные танцоры показывают свое мастерство на дворовой площадке. Звучит композиция «Rockit» B. T. & The City Slickers: аранжировка канонического трека американского композитора и пианиста Херби Хэнкока.

В фильме снялись ученики танцевальной школы «Правда» и другие известные танцоры, например, Олег Смолин и Константин Михайлов из группы «Меркурий». Затем «Меркурий» появился в фильмах «С роботами не шутят» (1987) из серии советских телеспектаклей «Этот фантастический мир», а позже в мюзикле «Гремучая дюжина» (1988) — в нем чечеточники соревнуются с брейк-данс-танцорами Также советский брейк-данс можно встретить в фильмах «Публикация» (1988) и «Меня зовут Арлекино» (1988) — в их эпизодах появляются московские танцоры..

В 1986 году стали выходить первые видеоклипы: помимо невероятного коллажа на песню Александра Градского, появились клипы групп «Браво» и «Машина времени». За год до этого вышли клипы Аллы Пугачевой, а также группы «Кино». Тогда же будущая поп-звезда Владимир Пресняков — младший выпустил клип на песню «Рыжий кот», в котором продемонстрировал технику брейк-данса. Видео показали в популярной передаче «Утренняя почта» на Первой программе Центрального телевидения. Еще один знаковый видеоклип — работа Александра Кальянова «Карабас-Барабас».

Фильмы и клипы популяризировали брейкинг и сделали его частью массовой культуры: аудитория, интересующаяся брейк-дансом, стремительно увеличилась. Такой ажиотаж не мог остаться незамеченным, и брейкинг получил государственную поддержку. Министерство по делам молодежи увидело в уличном танце один из способов оздоровления нации.

Первые брейк-данс-фестивали и баттлы проходили в Прибалтике, которая была на передовой советской поп-культуры: к примеру, в Юрмале проходил первый в стране регулярный музыкальный фестиваль. 26 апреля 1986 года в городе Винни (Эстонская ССР) прошел первый всесоюзный брейкинг-фестиваль под названием Modern Tants. А осенью этого же года в Таллине прошел всесоюзный финал, на который съехались лучшие российские брейк-танцоры:

«В 86 году состоялся всесоюзный конкурс по брейк-дэнсу в Таллине. Это делали местные комсомольцы, которые круто подготовились. Арендовали целиком гостиницу „Спорт“ и заселили ее делегатами из Минска, Киева, Риги, Питера, Харькова, ну и москвичи, само собой. Одних участников было человек 100. При этом все ехали с группами поддержки, прикинутыми и шумными. Когда вся эта толпа собралась в гостинице, обслуживающий персонал сошел с ума. Круглосуточно неслась громкая музыка. Во всех коридорах репетировали участники и шлялись поклонники; было ощущение полного счастья. Пьяных, кстати, не было, что для субкультуры, согласитесь, нетипично» Фрагмент из интервью Милы Максимовой.

М. Бастер. Хулиганы-80. М., 2009..

В основном брейкинг-фестивали проходили в формате баттлов. Баттл — это основной инструмент коммуникации уличных танцоров. Он представляет собой танец друг напротив друга, при этом исполнители окружены людьми. По сути, баттл — это продолжение фольклорной традиции, перенос сельских танцевальных практик в город. Танцоры по очереди делают выходы, показывая свою технику и рассказывая свою историю. Танец сам по себе — это средство коммуникации. Соответственно, баттл — это разговор двух танцоров, обмен танцевальной информацией.

Как в хорошем разговоре, на баттле может родиться совершенно новая танцевальная идея, движение или концепция. Важную роль играет также мастерство импровизации, то есть создание новых движений без подготовки. Уличные исполнители понимают танец как работу, требующую многочасовых тренировок для достижения результата: это сближает брейк-данс с академическим танцем.

Позднее баттлы стали для танцоров частью профессиональной деятельности. Участвуя в них, они остаются видимыми и продолжают функционировать в сообществе как педагоги или судьи. Несмотря на то что баттлы брейк-данс-танцоров могут выглядеть довольно агрессивно, участники считают их в первую очередь культурным обменом. Некоторые показательные баттлы так и называют — exchange (с английского — «обмен»).

1987

Любера, брейкеры и неформальная культура

К 1987 году брейк-данс обрел всесоюзный масштаб. Фестивали проводились не только в Прибалтике, но и в России, Беларуси и на Украине. Соревнования длились по несколько дней и транслировались по местному телевидению. Параллельно с рассветом брейкинг-культуры развивались и неформальные объединения: рокеры, хиппи, панки, металлисты, а также любера (или люберы) — агрессивные молодые ребята из подмосковного города Люберцы. Они активно пропагандировали здоровый образ жизни и враждовали с модными неформалами. Любера в основном не трогали брейкеров из-за уважения и любви к спорту. Однако доставалось тем, кто выглядел слишком модно или «утюжил» То есть был фарцовщиком. вещи:

«При этом, конечно же, по городу курсировали группы люберов и часто наблюдали за брейкерами, но особо не трогали. Видимо, сказывался родственный спортивный стайлинг и пренебрежительное отношение со стороны радикальных неформалов, с которыми у них началась настоящая война. Еще в 86 году я познакомился с парнем, жившем на Ждани, который поначалу тяготел к брейку, а потом, уже в 88 году, я встретил его же, но уже в бычьем костюме и с другими интересами в голове. Он же тогда мне обозначил, что брейкеров мы не трогаем, а гоняем только мажоров, утюгов и радикалов. При этом сами брейкера волей-неволей были вынуждены заниматься утюжкой, чтобы „держать стиль“ и „быть на инфе“» Фрагмент из интервью Ильи Пинчера.

М. Бастер. Хулиганы-80. М., 2009..

В 1987 году на экраны вышел фильм латвийского режиссера Юриса Подниекса «Легко ли быть молодым?». Фильм рассказывал о советской молодежи начала 1980-х: их желаниях, мечтах и непростых взаимоотношениях с родителями. В каком-то смысле он сформулировал значение неформальных объединений для молодых людей этой эпохи.

1988

Триумф русского рока

В 1988 году в прокат вышел фильм Сергея Соловьева «Асса». Он сразу утвердил безоговорочный триумф русского рока. Виниловая пластинка с песнями из «Ассы» стала одним из первых официальных изданий отечественной рок-музыки. В саундтреке звучали композиции Бориса Гребенщикова и группы «Аквариум», группы «Браво» с Жанной Агузаровой и группы «Кино»:

«Еще больше обломал меня Сергей Соловьев, который чуть было не пригласил меня на главную роль в свою „Ассу“. Мало кто знает, что сначала он хотел смешать художественную часть фильма с брейк-дэнсом. Мы ходили на „Мосфильм“, даже делали кинопробы. Но потом Соловьев поехал в Питер, и его там убедили, что брейк-дэнс уже сходит, а новая волна — это рок-музыка. Тогда он решил делать ставку на рок, выбрал по моему типажу на главную роль Африку, а музыкальную часть перенес на „Кино“, „Аквариум“ и другие питерские группы. Пока фильм созрел, эта волна и впрямь подошла» История брейк-данса российского // Школа брейк-данса «Волнорез». 2013 год..

Волна брейкинга действительно постепенно сходила на нет. Многих танцовщиков забирали в армию, остальные обзавелись семьями. Дворец культуры «Правда» закрылся, а брейк-данс начали танцевать нарядные детские коллективы. Так стиль угас.

Но самые увлеченные би-бои Би-бой/би-гёрл (англ. b-boy/b-girl) — человек, который танцует брейк-данс. продолжали выступать на Арбате и углубляться в историю стиля. Они начали понимать брейк-данс как часть хип-хоп-культуры, включающей в себя не только танец, и открыли для себя рэп:

«Еще в 88 году все знали, что есть не только брейк, но и рэп, так что попытки читать предпринимались неоднократно. Тимур Мамедов, помнится, на Арбате, на 1 апреля, когда люди танцевали на сцене и по каким-то причинам не работал магнитофон, на ходу сочинял и под отхлопывавшийся ритм читал такое… Типа: „Итак, друзья! Как видите вы, мы брейкера из города Москвы. Я этим вас не буду удивлять, я начинаю рэп читать…“» Фрагмент из интервью Ильи Пинчера.

М. Бастер. Хулиганы-80. М., 2009.

1989 и начало 1990-х

От брейк-данса к рэпу

В 1989 году появились первые рэп-коллективы. Танцевальный коллектив «Меркурий» трансформировался в рэп-группу DMJ, состоящую из двух солистов и трех танцоров. Хип-хоп-дуэт «Черное и белое» взял к себе брейкинг-танцоров из коллектива «Стоп».

1989-й — год основания команды Bad Balance: она сформировалась из брейк-данс-коллектива «Белые перчатки». В 1990 году к ней присоединился известный на тот момент музыкант и певец Михей. Позже они стали легендами локальной хип-хоп-культуры. Участники команды не только писали музыку и читали рэп, но и танцевали брейк-данс. А 1991 году появилась группа «Мальчишник», состоящая, по сути, из арбатских уличных танцоров.

Дальнейшее развитие брейкинга происходило уже внутри хип-хоп-культуры. Между танцем, музыкой и искусством (граффити) возникли прочные горизонтальные связи. Люди переходили из одного вида творчества в другой, вместе проводили время и организовывали мероприятия.

Первая волна брейк-данса отмечена протестом и улицей, которые позже компенсировалась спортивными (многочисленные чемпионаты) и культурными (совместные тусовки и мероприятия) проектами. Однако субкультура неразрывно связана с протестом: он дает энергию для развития и социального объединения, которую сложно чем-то заменить.

«Я начинал в конце 90-х, и для нас это тоже был протест. Мы протестовали против попыток школ, спортивных секций и родителей сделать из молодежи серую массу, которые должны были одеваться так, чтобы не выделяться, не слушать громко музыку и так далее. Это был протест против другого, нежели в 80-х, но он был сто процентов» Фрагмент из интервью Яна Немаловского. Записала Ольга Крупник. 2022 год..

В будущем брейкинг стал профессиональнее с точки зрения техники, упрочнился и межкультурный обмен. Однако в том виде, в котором этот стиль существовал до 1990 года, он уже не проявлялся.

Благодарим Алексея Крупника за помощь в написании материала, а также Яна Немаловского, Матвея Лебедева и Ольгу Щетинину за дополнения и комментарии.

Что такое современный танец

История, язык, открытия, герои и направления хореографии XX века — в аудиолекциях, видеороликах, таблицах и текстах

микрорубрики

Ежедневные короткие материалы, которые мы выпускали последние три года

Архив

A breakdancer performing outside Faneuil Hall, Boston, United States |

|

| Genre | Hip-hop dance |

|---|---|

| Inventor | Street dancers |

| Year | Early 1970s |

| Origin | New York City |

Breaking in the street, 2013

A breakdancer standing on his head in Cologne, Germany, 2017

Breakdancing, also called breaking or b-boying/b-girling, is an athletic style of street dance originating from the African American communities in the United States. While diverse in the amount of variation available in the dance, breakdancing mainly consists of four kinds of movement: toprock, downrock, power moves and freezes. Breakdancing is typically set to songs containing drum breaks, especially in hip-hop, funk, soul music and breakbeat music, although modern trends allow for much wider varieties of music along certain ranges of tempo and beat patterns.

The modern dance elements of breakdancing originated among the poor youth of New York during the early 1970s, where it was introduced as breaking.[1] It is closely attributed to the birth of hip-hop, as DJs developed rhythmic breaks for dancers.[2] The dance form has since expanded globally, with an array of organizations and independent competitions supporting its growth. Breaking will now be featured as an Olympic sport, making its debut in the 2024 Paris Summer Olympics.

A practitioner of this dance is called a b-boy, b-girl, breakdancer or breaker. Although the term «breakdance» is frequently used to refer to the dance in popular culture and in the mainstream entertainment industry, «b-boying» and «breaking» were the original terms and are preferred by the majority of the pioneers and most notable practitioners.[3][4]

Terminology[edit]

Instead of the original term «b-boying» («break-boying»), the mainstream media promoted the art form as «breakdancing», the term by which it came to be generally known. Some enthusiasts consider «breakdancing» an ignorant, and even pejorative, term, due to the media’s exploitation of the art form,[5] while others use it to derogatorily refer to studio-trained dancers that can perform the moves but who do not live a «b-boy lifestyle»,[6]: 61 and accuse the media of displaying a simplified[7] version of the dance that focused on «tricks» instead of culture.[8] The term «breakdancing» has become an umbrella term that includes California-based dance styles such as popping, locking, and electric boogaloo, in addition to the New York-based b-boying.[6]: 60 [9][10][11] The dance itself is called «breaking.»[12]

The terms «b-boy» («break-boy»), «b-girl» («break-girl»), and «breaker» were the original terms used to describe the dancers who performed to DJ Kool Herc’s breakbeats. The obvious connection of the term «breaking» is to the word «breakbeat».[citation needed] DJ Kool Herc has commented that the term «breaking» was 1970s slang for «getting excited», «acting energetically» or «causing a disturbance».[13] Most breakdancing pioneers and practitioners prefer the terms «b-boy», «b-girl», and/or «breaker» when referring to these dancers. For those immersed in hip-hop culture, the term «breakdancer» may be used to disparage those who learn the dance for personal gain rather than for commitment to the culture.[6]: 61 B-boy London of the New York City Breakers and filmmaker Michael Holman refer to these dancers as «breakers».[3] Frosty Freeze of the Rock Steady Crew says, «we were known as b-boys», and hip-hop pioneer Afrika Bambaataa says, «b-boys, [are] what you call break boys… or b-girls, what you call break girls.»[3] In addition, co-founder of Rock Steady Crew Santiago «Jo Jo» Torres, Rock Steady Crew member Marc «Mr. Freeze» Lemberger, hip-hop historian Fab 5 Freddy, and rappers Big Daddy Kane[14] and Tech N9ne[15] use the term «b-boy».[3]

| Source | Quote | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Richard «Crazy Legs» Colon; Rock Steady Crew |

«When I first learned about the dance in 1977 it was called b-boying… by the time the media got a hold of it in like ’81, ’82, it became ‘break-dancing’ and I even got caught up calling it break-dancing too.» | [3] |

| Michael Holman, New York City Breakers | «Maybe what Legs is doing is saying «I want to reeducate the marketplace and make them see that everything that came before was ‘breakdancing’ and what’s going on now is ‘b-boying.’ And it’s all under my control and auspices and whim and whatever.» And so it’s a cleansing; it’s like an etymological purging….But it’s smart, because it’s a paradigm shift in which he now is not just a player but is a kingmaker. A kingpin.» | [6]: 62 |

| Mandalit del Barco, journalist | «Breakdancing may have died, but the b-boy, one of four original elements of hip hop (also included: the MC, the DJ, and the graffiti artist) lives on. To those who knew it before it was tagged with the name breakdancing, to those still involved in the scene that they will always know as b-boying, the tradition is alive and, well, spinning.» | [16] |

| Foundation, by Joseph Schloss | «In addition to its general association with commercialism, the term breakdancing is also problematic on a more practical level. Unlike b-boying, which refers to a specific dance form that developed in New York City in the ’70s, breakdancing is often used as an umbrella term that includes not only b-boying, but also popping, locking, boogalooing, and other so-called funk-style dances that originated in California.» | [6]: 60 |

| The Electric Boogaloos | «In the 80’s when streetdancing [sic] blew up, the media often incorrectly used the term ‘breakdancing’ as an umbrella term for most the streetdancing [sic] styles that they saw. What many people didn’t know was [that] within these styles, other sub-cultures existed, each with their own identities. Breakdancing, or b-boying as it is more appropriately known as, is known to have its roots in the east coast and was heavily influenced by break beats and hip hop.» | [17] |

| Timothy «Popin’ Pete» Solomon; Electric Boogaloos |

«An important thing to clarify is that the term ‘Break dancing’ is wrong, I read that in many magazines but that is a media term. The correct term is ‘Breakin’, people who do it are B-Boys and B-Girls. The term ‘Break dancing’ has to be thrown out of the dance vocabulary.» | [18] |

| Hip-Hop Dance Conservatory | «Breaking or b-boying is generally misconstrued or incorrectly termed as ‘breakdancing’. Breakdancing is a term spawned from the loins of the media’s philistinism, sciolism, and naïveté at that time. With no true knowledge of the hip-hop diaspora but with an ineradicable need to define it for the nescient masses, the term breakdancing was born. Most breakers take great offense to the term.» | [19] |

| Jeff Chang | «During the 1970s, an array of dances practiced by black and Latino kids sprang up in the inner cities of New York and California. The styles had a dizzying list of names: ‘uprock’ in Brooklyn, ‘locking’ in Los Angeles, ‘boogaloo’ and ‘popping’ in Fresno, and ‘strutting’ in San Francisco and Oakland. When these dances gained notice in the mid-’80s outside of their geographic contexts, the diverse styles were lumped together under the tag ‘break dancing’. | [11] |

| American Heritage Dictionary |

|

[20][21][22] |

History[edit]

Many elements of breaking can be seen in other antecedent cultures prior to the 1970s. B-boy pioneers Richard «Crazy Legs» Colon and Kenneth «Ken Swift» Gabbert, both of Rock Steady Crew, cite James Brown and Kung Fu films (notably Bruce Lee films) as influences.[23][24][25] Many of the acrobatic moves, such as the flare, show clear connections to gymnastics. In the 1877 book ‘Rob Roy on the Baltic’ John MacGregor describes seeing near Norrköping a ‘…young man quite alone, who was practicing over and over the most inexplicable leap in the air…he swung himself up, and then round on his hand for a point, when his upper leg described a great circle…’. The engraving shows a young man apparently breakdancing. The dance was called the Giesse Harad Polska or ‘salmon district dance’. In 1894 Thomas Edison filmed Walter Wilkins, Denny Toliver and Joe Rastus dancing and performing a «breakdown».[26][27] Then in 1898 he filmed a young street dancer performing acrobatic headspins.[28] However, it was not until the 1970s that breakdancing developed as a defined dance style in the United States. There is also evidence of this style of dancing in Kaduna, Nigeria in 1959.[29]

These precursing elements began to take form in the early 1970s, as breaking began to grow at parties featuring DJs and instrumental records.[30] It was at these parties that DJ Kool Herc, a Bronx based DJ pioneer, developed rhythmic breakdown sections by simultaneously switching between two copies of the same record, creating “breaks”.[31] By looping the records and their simultaneous breaks, he was able to prolong the break and provide a rhythmic and improvisational base for dancers:[32] Herc tells Jeff Chang in his book Can’t Stop Won’t Stop (2005), “And once they heard that, that was it, wasn’t no turning back. They always wanted to hear breaks after breaks after breaks after breaks.»[33]

The onset of breaking prompted dance battles known as cyphers, competitive circles in which participants took turns dancing while surrounded by onlookers. The term cypher and its use in hip-hop culture originates from the Five-Percent Nation, who utilized the term “cypher” to denote circles of people. Cyphers are environments in which breakers battle for dancing reputation, express cultural pride, and integrate elements such as toprocking or floor work to innovate one’s set.[34] Crews including the Rock Steady Crew or Mighty Zulu Kingz began to form, in response to the growth of competitive cyphers which sometimes featured cash-prizes, titles, and bragging rights.[35]

Uprock[edit]

Breaking started as toprock, footwork-oriented dance moves performed standing up, but as dance crews began to experiment, a separate dance form known as uprock further influenced breaking.[36] Uprock, also known as Brooklyn uprock, is a more aggressive dance style commonly performed between two partners that feature intricate footwork and hitting motions, mimicking a fight.[33] As a separate dance style, it never gained the same widespread popularity as breakdancing, except for some very specific moves adopted by breakers who use it as a variation for their toprock.[33] Uprock is also stated to have roots in gangs, as an expressive medium used to settle turf disputes, with the winner deciding the location of a future battle.[37] Although some disagree that breakdancing ever played a part in mediating gang rivalry, the early growth of breaking still primarily served to assist the poor youth of the Bronx to stray away from gang violence and rather expel their time towards an artistic dance.[38] One example is former gang leader Afrika Bambaataa, who hosted hip-hop parties and vowed to specifically use hip-hop to support children away from gang violence. He would eventually form the Universal Zulu Nation to further his message.[39]

Some breakers argue that because uprock was originally a separate dance style it should never be mixed with breakdancing and that the uprock moves performed by breakers today are not the original moves but imitations that only show a small part of the original uprock style.[40] In the music video for 1985’s hit single «I Wonder If I Take You Home», Lisa Lisa and Cult Jam’s drummer Mike Hughes can be seen «rocking» (doing uprock) at 1:24 when viewed on YouTube.

Worldwide expansion[edit]

This section describes the development of breakdancing throughout the world. Countries are sorted alphabetically.

Brazil[edit]

Ismael Toledo was one of the first breakers in Brazil.[41] In 1984, he moved to the United States to study dance.[41] While in the U.S. he discovered breakdancing and ended up meeting breaker Crazy Legs who personally mentored him for the four years that followed.[41] After becoming proficient in breakdancing, he moved back to São Paulo and started to organize crews and enter international competitions.[41] He eventually opened a hip-hop dance studio called the Hip-Hop Street College.[41]

Cambodia[edit]

Born in Thailand and raised in the United States, Tuy «KK» Sobil started a community center called Tiny Toones in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in 2005 where he uses dancing, hip-hop music, and art to teach Cambodian youth language skills, computer skills, and life skills (hygiene, sex education, counseling). His organization helps roughly 5,000 youths each year. One of these youths include Diamond, who is regarded as Cambodia’s first b-girl.[42][43]

Canada[edit]

There are several ways breakdancing came to Canada. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, films such as Breakin‘ (1984), Beat Street (1984), and the immigration of people from Chicago, New York, Detroit, Seattle, and Los Angeles introduced dance styles from the United States. Breakdancing expanded in Canada from there, with crews like Canadian Floormasters taking over the 80’s scene, and New Energy opening for James Brown in 1984 at the Paladium in Montreal. Leading into the 90’s, crews like Bag of Trix, Rakunz, Intrikit, Contents Under Pressure, Supernaturalz, Boogie Brats, and Red Power Squad, led the scene throughout the rest of the past two decades and counting.

France[edit]

Breakdancing took off in France in the early 1980s with the creation of groups such as the Paris City Breakers (who styled themselves after the well-known New York City Breakers). In 1984, France became the first country in the world to have a regularly and nationally broadcast television show about Hip Hop—hosted by Sidney Duteil—with a focus on Hip Hop dance.[44] This show led to the explosion of Hip Hop dance in France, with many new crews appearing on the scene.[45]

Japan[edit]

Breakdancing in Japan was introduced in 1983 following the release of the movie Wild Style. The release of the movie was accompanied by a tour by the Rock Steady Crew and the Japanese were captivated. Other movies such as Flashdance followed and furthered the breakdance craze. Crazy-A, who currently is the leader of the Tokyo chapter of the Rock Steady Crew,[46] was dragged to see Flashdance by his then girlfriend and walked out captivated by the dance form and became one its earliest and one of the most influential breakers in Japanese history. Groups began to spring up as well, with early groups such as Tokyo B-Boys, Dynamic Rock Force (American kids from Yokota AB), B-5 Crew, and Mystic Movers popping up in Harajuku, a district in Tokyo. The breakdancing community in Japan found a home in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park[46] in Harajuku, which still remains an active area for breakdancers and hip-hop enthusiasts. As hip-hop continued to grow in Japan, so did breakdancing and the breakdancing communities. Following the introduction of international breakdancing competitions, Japan began to compete and were praised for their agility and precision, yet they were criticized in the beginning for lacking originality. The Japanese began to truly flourish on the international stage following the breakdancing career of Taisuke Nonaka, known simply as Taisuke. Taisuke began to dominate the international scene and led the Japanese team Floorriorz to win the BOTY in 2015 against crew Kienjuice from Belarus. Despite Taisuke’s successful career in group competitions, he failed to win the solo Red Bull BC One competition, an individual breakdancing championship that had continued to evade Japanese bboys. The first Japanese to win the BC One competition became Bboy Issei in 2016. Issei is widely regarded by many as the best Japanese breakdancer currently and in the eyes of some, the best worldwide. Female bboys, or «bgirls», are also prevalent in Japan and following the introduction of a female BC One competition in 2018, Japanese bgirl Ami Yuasa became the first female champion. Notable Japanese bboy crews include FoundNation, Body Carnival, and the Floorriorz. Notable Japanese bgirl crews include Queen of Queens, Body Carnival, and Nishikasai.

South Korea[edit]

Breakdancing was first introduced to South Korea by American soldiers shortly after its surge of popularity in the U.S. during the 1980s, but it was not until the late 1990s that the culture and dance took hold.[47] 1997 is known as the «Year Zero of Korean breaking».[11] A Korean-American hip hop promoter named John Jay Chon was visiting his family in Seoul and while he was there, he met a crew named Expression Crew in a club. He gave them a VHS tape of a Los Angeles breakdancing competition called Radiotron.[48] A year later when he returned, Chon found that his video and others like his had been copied and dubbed numerous times, and were feeding an ever-growing breaker community.

In 2002, Korea’s Expression Crew won the prestigious international breakdancing competition Battle of the Year, exposing the skill of the country’s breakers to the rest of the world. Since then, the Korean government has capitalized on the popularity of the dance and has promoted it alongside Korean culture. R-16 Korea is the most well-known government-sponsored breakdancing event, and is hosted by the Korea Tourism Organization and supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism.

Famous breakdancing crews from Korea include Morning of Owl, Jinjo Crew, Rivers Crew and Gamblerz.

Soviet Union[edit]

In the 1980s the Soviet Union was in a state of the Cold War with the countries of the Western Bloc. Soviet people lived behind the Iron Curtain, so they usually learned the new fashion trends emerging in the capitalist countries with some delay. The Soviet Union first learned of breakdancing in 1984, when videotapes of the films Breakin‘, Breakin’ 2 and Beat Street got into the country. In the USSR these movies were not released officially. They were brought home by Soviet citizens who had the opportunity to travel to Western countries (for example, by diplomats). Originally, the dance became popular in big cities: Moscow and Leningrad, as well as in the Baltic republics (some citizens of these Soviet republics had the opportunity to watch Western television). The attitude of the authorities to the new dance that came from the West was negative.[49]

The situation changed in 1985 with Mikhail Gorbachev who came to power and with the beginning of the Perestroika policy. The first to legalize the new dance were dancers from the Baltic republics. They presented this dance as the «protest against the arbitrariness of the capitalists», explaining that the dance was invented by Black Americans from poor neighborhoods. In 1985 the performance of Czech Jiří Korn was shown in the program «Morning Post», and became one of the first official demonstrations of breakdancing on Soviet television. With the support of the Leninist Young Communist League in 1986 breakdance festivals were held in the cities of the Baltic republics (Tallinn, Palanga, Riga). The next step was the spreading of the similar festivals to other Soviet republics. Festivals were held in Donetsk (Ukraine), Vitebsk (Belarus), Gorky (Russia). Breakdancing could be seen in Soviet cinema: Dancing on the Roof (1985), Courier (1986), Publication (1988). By the end of the decade the dance became almost ubiquitous. At almost any disco or school dance one could see a person dancing in the «robot» style.[49]

In the early 1990s the country experienced a severe economic and political crisis. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the breakdance craze was over and breakdancing became dated. The next wave of interest in breakdancing in Russia would only occur in the late 90s.[49]

China[edit]

Although social media such as YouTube cannot be used in China, breakdancing in China has been popular. Many people copy breakdancing videos from abroad and distribute them back to the mainland. Although it is still an underground culture in China because of some restrictions, breakdancing was reported to be a growing presence in 2013.[50]

Dance elements[edit]

There are four primary elements that form breakdancing: toprock, downrock, power moves, and freezes.

- Toprock generally refers to any string of steps performed from a standing position. It is usually the first and foremost opening display of style, though dancers often transition from other aspects of breakdancing to toprock and back. Toprock has a variety of steps which can each be varied according to the dancer’s expression (i.e. aggressive, calm, excited). A great deal of freedom is allowed in the definition of toprock: as long as the dancer maintains cleanliness, form, and attitude, theoretically anything can be toprock. Toprock can draw upon many other dance styles such as popping, locking, tap dance, Lindy hop, or house dance. Transitions from toprock to downrock and power moves are called «drops».[51]

- Downrock (also known as «footwork» or «floorwork») is used to describe any movement on the floor with the hands supporting the dancer as much as the feet. Downrock includes moves such as the foundational 6-step, and its variants such as the 3-step. The most basic of downrock is done entirely on feet and hands but more complex variations can involve the knees when threading limbs through each other.

- Power moves are acrobatic moves that require momentum, speed, endurance, strength, flexibility, and control to execute. The breaker is generally supported by his upper body while the rest of his body creates circular momentum. Some examples are the windmill, swipe, back spin, and head spin. Some power moves are borrowed from gymnastics and martial arts. An example of a power move taken from gymnastics is the Thomas Flair which is shortened and spelled flare in breakdancing.

- Freezes are stylish poses that require the breaker to suspend himself or herself off the ground using upper body strength in poses such as the pike. They are used to emphasize strong beats in the music and often signal the end of a set. Freezes can be linked into chains or «stacks» where breakers go from freeze to freeze to freeze in order to hit the beats of the music which displays musicality and physical strength.

Styles[edit]

Bboy DanceMachine at the Breakfast Jam finals in Kampala, Uganda on November 19, 2016

There are many individual styles used in breakdancing. Individual styles often stem from a dancer’s region of origin and influences. However, some people such as Jacob «Kujo» Lyons believe that the internet inhibits individual style. In a 2012 interview with B-Boy Magazine he expressed his frustration:

B-boys performing on San Francisco’s Powell Street in 2008

B-Boy performing hand hops in Washington D.C.

… because everybody watches the same videos online, everybody ends up looking very similar. The differences between individual b-boys, between crews, between cities/states/countries/continents, have largely disappeared. It used to be that you could tell what city a b-boy was from by the way he danced. Not anymore. But I’ve been saying these things for almost a decade, and most people don’t listen, but continue watching the same videos and dancing the same way. It’s what I call the «international style», or the «Youtube style».[52]

Luis «Alien Ness» Martinez, the president of Mighty Zulu Kings, expressed a similar frustration in a separate interview three years earlier with «The Super B-Beat Show» about the top five things he hates in breakdancing:

Oh yeah, the last thing I hate in breakin’… Yo, all y’all motherfuckin’ internet b-boys… I’m an internet b-boy too, but I’m real about my shit. Everybody knows who I am, I’m out at every fucking jam, I’m in a different country every week. I tell my story dancing… I’ve been all around the world, y’all been all around the world wide web… [my friend] Bebe once said that shit, and I co-sign that, Bebe said that. That wasn’t me but that’s the realist shit I ever heard anybody say. I’ve been all around the world, you’ve been all around the world wide web.[53]

Although there are some generalities in the styles that exist, many dancers combine elements of different styles with their own ideas and knowledge in order to create a unique style of their own. Breakers can therefore be categorized into a broad style which generally showcases the same types of techniques.

- Power: This style is what most members of the general public associate with the term «breakdancing». Power moves comprise full-body spins and rotations that give the illusion of defying gravity. Examples of power moves include head spins, back spins, windmills, flares, air tracks/air flares, 1990s, 2000s, jackhammers, crickets, turtles, hand glides, halos, and elbow spins. Those breakers who use «power moves» almost exclusively in their sets are referred to as «power heads».

- Abstract: A very broad style which may include the incorporation of «threading» footwork, freestyle movement to hit beats, house dance, and «circus» styles (tricks, contortion, etc.).

- Blow-up: A style which focuses on the «wow factor» of certain power moves, freezes, and circus styles. Blowups consist of performing a sequence of as many difficult trick combinations in as quick succession as possible in order to «smack» or exceed the virtuosity of the other breaker’s performance. The names of some of these moves are air baby, hollow backs, solar eclipse, and reverse air baby, among others. The main goal in blow-up style is the rapid transition through a sequence of power moves ending in a skillful freeze or «suicide». Like freezes, a suicide is used to emphasize a strong beat in the music and signal the end to a routine. While freezes draw attention to a controlled final position, suicides draw attention to the motion of falling or losing control. B-boys or b-girls will make it appear that they have lost control and fall onto their backs, stomachs, etc. The more painful the suicide appears, the more impressive it is, but breakers execute them in a way to minimize pain.

- Flavor: A style that is based more on elaborate toprock, downrock, and/or freezes. This style is focused more on the beat and musicality of the song than having to rely on power moves only. Breakers who base their dance on «flavor» or style are known as «style heads».

Downrock styles[edit]

In addition to the styles listed above, certain footwork styles have been associated with different areas which popularized them.[54]

- Traditional New York Style: The original style from the Bronx, based around the Ukrainian Tropak dance. This style of downrock focuses on kicks called «CCs» and foundational moves such as 6-steps and variations of it.[55]

- Euro Style: Created in the early 90s, this style is very circular, focusing not on steps but more on glide-type moves such as the pretzel, undersweeps and fluid sliding moves.[56]

- Toronto Style: Created in the mid 90s, also known as the ‘Toronto thread’ style. Similar to the Euro Style, except characterized by complex leg threads, legwork illusions, and footwork tricks. This style is attributed to three crews, Bag of Trix (Gizmo), Supernaturalz (Leg-O & Dyzee) and Boogie Brats (Megas).[57]

Music[edit]

The musical selection for breakdancing is not restricted to hip-hop music as long as the tempo and beat pattern conditions are met. Breakdancing can be readily adapted to different music genres with the aid of remixing. The original songs that popularized the dance form borrow significantly from progressive genres of funk, soul, disco, electro, and jazz funk. A musical canon of these traditional b-boy songs have since developed, songs that were once expected to be played at every b-boying event.[58] As the dance form grew, this standardization of classic songs prompted innovation of dance moves and break beats that reimagined the standard melodies. These songs include “Give It Up or Turn It a Loose” by James Brown, “Apache” by the Incredible Bongo Band, and «The Mexican» by Babe Ruth to name a few.[59][60]

The most common feature of breakdance music exists in musical breaks, or compilations formed from samples taken from different songs which are then looped and chained together by the DJ. The tempo generally ranges between 110 and 135 beats per minute with shuffled sixteenth and quarter beats in the percussive pattern. History credits DJ Kool Herc for the invention of this concept[33] later termed the break beat.

Major competitions[edit]

- Battle of the Year (BOTY) was founded in 1990 by Thomas Hergenröther in Germany.[61] It is the first and largest international breakdancing competition for breakdance crews.[62] BOTY holds regional qualifying tournaments in several countries such as Zimbabwe, Japan, Israel, Algeria, Indonesia, and the Balkans. Crews who win these tournaments go on to compete in the final championship in Montpellier, France.[61] BOTY was featured in the independent documentary Planet B-Boy (2007) that filmed five dance crews training for the 2005 championship. A 3D film Battle of the Year was released in January 2013. It was directed by Benson Lee who also directed Planet B-Boy.[63]

- The Notorious IBE is a Dutch-based breakdancing competition founded in 1998.[64] IBE (International Breakdance Event) is not a traditional competition because there are not any stages or judges. Instead, there are timed competitive events that take place in large multitiered ciphers—circular dance spaces surrounded by observers—where the winners are determined by audience approval.[64] There are several kinds of events such as the b-girl crew battle, the Seven 2 Smoke battle (eight top ranked breakers battle each other to determine the overall winner), the All vs. All continental battle (all the American breakers vs. all the European breakers vs. the Asian breakers vs. Mexican/Brazilian breakers), and the Circle Prinz IBE.[64] The Circle Prinz IBE is a knockout tournament that takes place in multiple smaller cipher battles until the last standing breaker is declared the winner.[64] IBE also hosts the European finals for the UK B-Boy Championships.[65]

- Chelles Battle Pro was created in 2001 and it is held every year in Chelles, France. There are two competitions. One is a kids competition for solo breakers who are 12 years old or younger. The other competition is a knock-out tournament for eight breaker crews. Some crews have to qualify at their country’s local tournament; others are invited straight to the finale.[66]

- Red Bull BC One was created in 2004 by Red Bull and is hosted in a different country every year.[67] The competition brings together the top 16 breakers from around the world.[67] Six spots are earned through six regional qualifying tournaments. The other 10 spots are reserved for last year’s winner, wild card selections, and recommendations from an international panel of experts. A past participant of the competition is world record holder Mauro «Cico» (pronounced CHEE-co) Peruzzi. B-boy Cico holds the world record in the 1990s. A 1990 is a move in which a breaker spins continuously on one hand—a hand spin rather than a head spin. Cico broke the record by spinning 27 times.[68][69] A documentary based on the competition called Turn It Loose (2009) profiled six breakdancs training for the 2007 championship in Johannesburg.[70] Two of these breakdancers were Ali «Lilou» Ramdani from Pockémon Crew and Omar «Roxrite» Delgado from Squadron.

A breakdancer does an air-flare in a cypher at R16 Korea 2014

- R16 Korea is a South Korean breakdancing competition founded in 2007 by Asian Americans Charlie Shin and John Jay Chon.[71] Like BOTY and Red Bull BC One put together, Respect16 is a competition for the top 16 ranked crews in the world.[72] What sets it apart from other competitions is that it is sponsored by the government and broadcast live on Korean television and in several countries in Europe.[71] In 2011, R16 instituted a new judging system that was created to eliminate bias and set a unified and fair standard for the way breakdance battles should be judged.[73] With the new system, breakers are judged against five criteria: foundation, dynamics (power moves), battle, originality, and execution. There is one judge for each category and the scores are shown on a large screen during battles so that the audience can see who is winning at any given moment.[74]

- The Youth Olympic Games incorporated breakdancing as part of its programme, starting with the 2018 Summer Youth Olympics in Buenos Aires. Breakdancing is eligible for inclusion as it is a discipline of dancesport, which is recognised by the International Olympic Committee. The competition features men’s, women’s and mixed-team events in a one-on-one battle format.[75]

- The 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris will see breakdancing make its Olympic debut. 16 male and 16 female breakdancers will compete in head-to-head matches.[76][77] IOC President Thomas Bach stated that they added breakdancing as part of an effort to draw more interest from young people in the Olympics.[78]

Female presence[edit]

Similar to other hip-hop subcultures, such as graffiti writing, rapping, and DJing, breakers are predominantly male, but this is not to say that women breakers, b-girls, are invisible or nonexistent. Female participants, such as Daisy Castro (also known as Baby Love of Rock Steady Crew), attest that females have been breakdancing since its inception.[79] Critics argue that it is unfair to make a sweeping generalization about these inequalities because women have begun to play a larger role in the breakdancing scene.[80][81]

Some people have pointed to a lack of promotion as a barrier, as full-time b-girl Firefly stated in a BBC piece: «It’s getting more popular. There are a lot more girls involved. The problem is that promoters are not putting on enough female-only battles.»[82][83] Growing interest is being shown in changing the traditional image of females in hip-hop culture (and by extension, breakdance culture) to a more positive, empowered role in the modern hip-hop scene.[84][85][86]

In 2018, Japan’s B-Girl Ami became the first B-Girl world champion of Red Bull BC One.[87] Although B-Girl Ayumi had been invited as a competitor for the 2017 championship, it was only until 2018 that a 16 B-Girl bracket was featured as part of the main event.

B-girls, such as Honey Rockwell, promote breakdancing through formal instruction ensuring a new generation of breakers.[88]

Media exposure[edit]

Film[edit]

In the past 50 years, various films have depicted the dance. 1975’s (filmed in 1974) Tommy included a breakdancing sequence during the «Sensation» number. Later, in the early 1980s, several films depicted breakdancing including Fame, Wild Style, Flashdance, Breakin’, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo, Delivery Boys, Krush Groove, and Beat Street. In 1985, at the height of breakdancing’s popularity, Donnie Yen starred in a Hong Kong film called Mismatched Couples in which he performed various b-boy and breakdancing moves.

The 2000s saw a resurgence of films and television series featuring breakdancing that continued into the early 2010s:

- The 2001 comedy film Zoolander depicts Zoolander (Ben Stiller) and Hansel (Owen Wilson) performing breakdance moves on a catwalk.

- The 2004 anime television series Samurai Champloo features one of the main characters, Mugen using a fighting style based on breakdancing.

- The Step Up films (2006–14) are dance movies that focus on the passion and love of dance. Breakdancing is featured in all five films, Step Up, Step Up 2: The Streets, Step Up 3D, and Step Up Revolution, and Step Up: All In, as well as the TV series Step Up: High Water.

- The 2007 comedy Kickin’ It Old Skool stars Jamie Kennedy as a breakdancer who hits his head during a talent show and wakes up from a coma in the year 2007, then plans to get his breakdancing team back together.

- The 2009 Thai martial arts film Raging Phoenix features a fictional martial art called meiraiyutth based on a combination of Muay Thai and breakdancing.

- The 2009 British drama film Fish Tank stars Katie Jarvis as a 15-year-old who regularly practices hip-hop dance, including breakdancing, in her council estate.

- The 2013 American 3D dance film Battle of the Year is a drama about the dance competition of the same name.

Several documentary films have been made about breakdancing:

- The 1983 PBS documentary Style Wars chronicled New York graffiti artists, but also includes some breakdancing.

- The 2002 documentary film The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy provides a comprehensive history of breakdancing including its evolution and its place within hip-hop culture.

- The 2007 documentary Planet B-Boy follows five crews from around the world in their journey to the international breakdancing competition Battle of the Year. The Planet B-Boy documentary was the inspiration for the 2013 American 3D dance film Battle of the Year, a drama about the competition of the same name.

- The award-winning (SXSW Film Festival audience award) 2007 documentary «Inside the Circle»[89] goes into the personal stories of three breakdancers (Omar Davila, Josh «Milky» Ayers and Romeo Navarro) and their struggle to keep dance at the center of their lives.

- The 2010 German documentary Neukölln Unlimited depicts the life of two breakdancing brothers in Berlin that try to use their dancing talents to secure a livelihood. Breakdancing moves are sometimes incorporated into the choreography of films featuring martial arts. This is due to the visually pleasing aspect of the dance, no matter how ridiculous or useless it would be in an actual fight.

Television[edit]

In the United States, Breakdancing is widely referenced in TV advertising, as well as news, travelogue, and documentary segments, as an indicator of youth/street culture. From a production point of view the style is visually arresting, instantly recognizable and adducible to fast-editing, while the ethos is multi-ethnic, energetic and edgy, but free from the gangster-laden overtones of much rap-culture imagery. Its usability as a visual cliché benefits sponsorship, despite the relatively small following of the genre itself beyond the circle of its practitioners. In 2005, a Volkswagen Golf GTi commercial featured a partly CGI version of Gene Kelly popping and breakdancing to a remix of «Singin’ in the Rain» by Mint Royale. The tagline was, «The original, updated.» The dance shows So You Think You Can Dance and America’s Best Dance Crew arguably brought breakdancing back to the forefront of pop culture in the United States, similar to the popularity it had enjoyed in the 1980s. The American drama television series Step Up: High Water, a series focused on breakdancing and other forms of hip-hop dance, premiered on March 20, 2019.

Since breakdancing’s popularity surge in South Korea, it has been featured in various TV dramas and commercials. Break is a 2006 South Korean miniseries about a breakdancing competition. Over the Rainbow is a 2006 South Korean drama series centered on different characters who are brought together by breakdancing. Showdown, a breakdancing competition game show hosted by Jay Park, premiered in South Korea on March 18, 2022.[90][91][92]

Literature[edit]

- In 1997, Kim Soo Yong began serialization of the first breakdancing themed comic, Hip Hop. The comic sold over 1.5 million books and it helped to introduce breakdancing and hip-hop culture to Korean youth.

- The first breakdancing themed novel, Kid B, was published by Houghton Mifflin in 2006. The author, Linden Dalecki, was an amateur breaker in high school and directed a short documentary film about Texas breakdancing culture before writing the novel. The novel was inspired by Dalecki’s short story The B-Boys of Beaumont, which won the 2004 Austin Chronicle short story contest.

- Breakin’ the city, a photo book by Nicolaus Schmidt, portrays breakers from the Bronx and Brooklyn wheeling around on subway cars, in city plazas, and on sidewalks in New York City.[93] Published in 2011, it features six New York based breakdance crews photographed between 2007 and 2009.[94]

- Breakdancing: Mr. Fresh and the Supreme Rockers Show You How (Avon Books, 1984) was an introductory reference for newcomers to the «breakin'» style of dance as it evolved in North America in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Cypher Circle, a breakdancing themed comic was published by Ricematic Studio in 2022 by author and illustrator Benny Ng. The comic focuses on the adventures of B-Girl Annabelle and her teammates from the 6 Diamonds Crew.

Video gaming[edit]

There have been only few video games created that focus on breakdancing. The main deterrence for attempting to create games like these is the difficulty of translating the dance into something entertaining and fun on a video game console. Most of these attempts had low to average success.

- Break Dance is an 8-bit computer game by Epyx released in 1984 at the height of breakdancing’s popularity.

- Break Street is a computer game in which the player receives points for performing complex dance moves using the joystick without exhausting the player character’s remaining energy.[95] It was released for the Commodore 64 in October 1984 at the height of breakdancing’s popularity.

- B-boy is a 2006 console game released for PS2 and PSP which aims at an unadulterated depiction of breakdancing.[96]

- Bust a Groove is a video game franchise whose character «Heat» specializes in breakdancing.

- Pump It Up is a Korean game that requires physical movement of the feet. The game involves breakdancing and people can accomplish this feat by memorizing the steps and creating dance moves to hit the arrows on time.

- Breakdance Champion Red Bull BC One is an iOS and Android rhythm game that focuses on the actual breakdancing competition Red Bull BC One.[97]

- Floor Kids is a Nintendo Switch game released in 2017 that scores your performance based on its musicality, originality, and style.[98] It received praise for its innovative controls and the Kid Koala soundtrack.[99][100]

- In the long running Yakuza video game franchise, Goro Majima’s Breaker fighting style heavily relies on movements and techniques derived from break dancing.

References[edit]

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2007). «It’s a Hip-Hop World». Foreign Policy (163): 58–65. ISSN 0015-7228.

- ^ «From the Bronx to the world: The birth and evolution of hip-hop». Red Bull. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Israel (director) (2002). The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy (DVD). USA: QD3 Entertainment.

- ^ Adam Mansbach (May 24, 2009). «The ascent of hip-hop: A historical, cultural, and aesthetic study of b-boying (book review of Joseph Schloss’ «Foundation»)». The Boston Globe.

- ^ Spot, The Bboy. «History of the word «Breakdancing» by Crazy Legs». Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Schloss, Joseph (2009). Foundation: B-boys, B-girls, And Hip-Hop Culture In New York. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Fuhrer, Margaret (2014). American Dance. Minneapolis: Voyageur. p. 253.

- ^ Fogarty, Mary (2008). What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?’: Transnational B-Boy/b-Girl Networks, Underground Video Magazines and Imagined Affinities. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ Rivera, Raquel (2003). «It’s Just Begun: The 1970s and Early 1980s». New York Ricans from the Hip Hop Zone. New York City: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 72. ISBN 1-4039-6043-7.

- ^ Freeman, Santiago (July 1, 2009). «Planet Funk». Dance Spirit Magazine. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c «The World’s Best Dance Crew :: How Korean B-Boys Conquered Planet Rock « Can’t Stop Won’t Stop». Cantstopwontstop.com. June 26, 2008. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ The Freshest Kids. youtube.com.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Kool Herc, in Israel (director), The Freshest Kids, QD3, 2002.

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 302

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 293.

- ^ «Breakdancing, Present at the Creation». NPR.org. National Public Radio. October 14, 2002. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ «‘Funk Styles’ History And Knowledge». ElectricBoogaloos.com. 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Klopman, Alan (January 1, 2007). «Interview with Popin Pete & Mr. Wiggles at Monsters of Hip Hop – July 7–9, 2006, Orlando, Fl». DancerUniverse.com. Dancer Publishing. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011.

- ^ «About HDC». HDCNY.com. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ «b-boy». AHDictionary.com. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ «b-boy». AHDictionary.com. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ «b-boy». AHDictionary.com. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Cook, Dave (2001). «Crazy Legs Speaks». DaveyD.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- ^ Delgado, Julie (September 26, 2007). «Capoeira and Break-Dancing: At the Roots of Resistance». Capoeira-Connection.com. WireTap Magazine. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Neal, Mark Anthony; Forman, Murray (2004). That’s the Joint!: The Hip-hop Studies Reader. Psychology Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-415-96919-2.

- ^ The Pickaninny Dance (MP4) (MP4). Edison Manufacturing Company. October 6, 1894. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ «The Pickaninny Dance, from the ‘Passing Show’«. IMDb.

- ^ A Street Arab (MPG) (MPG). Thomas A. Edison Inc. April 21, 1898. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ^ Celebratory Dancing, Kaduna, Northern Nigeria, 1959. Archive film 98275. Nigeria: Huntley Film Archives. 1959. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ^ «Don’t Call it Breakdancing: The Origin Story of Breaking In Milwaukee». Milwaukee Magazine. August 28, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2006). ««Like Old Folk Songs Handed Down from Generation to Generation»: History, Canon, and Community in B-Boy Culture». Ethnomusicology. 50 (3): 420. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ «Hip Hop is born at a birthday party in the Bronx — History.com This Day in History — 8/11/1973». web.archive.org. October 5, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Chang, Jeff (2005). Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York: St. Martin’s Press. p. 21.

- ^ Johnson, Imani Kai; ﺟﻮﻧﺴﻮﻥ, ﺇﻳﻤﺎﻧﻲ ﻛﺎﻱ (2011). «B-Boying and Battling in a Global Context: The Discursive Life of Difference in Hip Hop Dance / ﺍﻟﺮﻗﺺ ﺑﻮﺻﻔﻪ ﺻﺮﺍﻋﺎً ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺴﻴﺎﻕ ﺍﻟﻌﻮﻟﻤﻲ: ﺍﻟﺤﻴﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺨﻄﺎﺑﻴﺔ ﻟﻼﺧﺘﻼﻑ ﻓﻲ ﺭﻗﺺ ﺍﻟﻬﻴﺐ ﻫﻮﺏ». Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics (31): 173. ISSN 1110-8673.

- ^ Johnson, Imani Kai; ﺟﻮﻧﺴﻮﻥ, ﺇﻳﻤﺎﻧﻲ ﻛﺎﻱ (2011). «B-Boying and Battling in a Global Context: The Discursive Life of Difference in Hip Hop Dance / ﺍﻟﺮﻗﺺ ﺑﻮﺻﻔﻪ ﺻﺮﺍﻋﺎً ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﺴﻴﺎﻕ ﺍﻟﻌﻮﻟﻤﻲ: ﺍﻟﺤﻴﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺨﻄﺎﺑﻴﺔ ﻟﻼﺧﺘﻼﻑ ﻓﻲ ﺭﻗﺺ ﺍﻟﻬﻴﺐ ﻫﻮﺏ». Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics (31): 173–195. ISSN 1110-8673.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2006). ««Like Old Folk Songs Handed Down from Generation to Generation»: History, Canon, and Community in B-Boy Culture». Ethnomusicology. 50 (3): 411–432. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2006). ««Like Old Folk Songs Handed Down from Generation to Generation»: History, Canon, and Community in B-Boy Culture». Ethnomusicology. 50 (3): 411–432. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2007). «It’s a Hip-Hop World». Foreign Policy (163): 58–65. ISSN 0015-7228.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2007). «It’s a Hip-Hop World». Foreign Policy (163): 6. ISSN 0015-7228.

- ^ Coudntpickname (January 1, 2007). «Bboy/Bgirl Foundations: Toprock». YouTube. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jenkins, Greg (April 1, 2011). «São Paulo’s Original B-Boy». WeRClassic.com. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ Dwyer, Alex (February 19, 2012). «Samsonite Man: Breaking The Cycle With Cambodia, Crips & Education». HipHopDX.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ «History». TinyToones.org. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Meghelli, Samir (2012). Between New York and Paris: Hip Hop and the Transnational Politics of Race, Culture, and Citizenship. New York, NY: Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University.

- ^ Spady, James G.; Alim, H. Samy; Meghelli, Samir (2006). The Global Cipha: Hip Hop Culture and Consciousness. Philadelphia, PA: Black History Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-9671741-1-2.

- ^ a b Condry, Ian. «Japanese Hip-Hop». mit.edu. MIT. Archived from the original on April 22, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Usher, Charles (July 5, 2011). «South Korea: World breakdancing capital?». Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- ^ Rivera, Selene (November 10, 2022). «An immigrant’s dream makes an iconic Boyle Heights music venue flow with ‘body rhythm’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c «30-летие первой волны брейкданса в СССР (1986-2016)». DOZADO. January 5, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ «Growing presence of B-boys and B-girls in China is slowly emerging to the dance world». The World of Chinese. September 17, 2013. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2006). Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-Hop. New York City: BasicCivitas. p. 20. ISBN 0-465-00909-3.

The transition between top and floor rockin’ was also important and became known as the ‘drop’.

- ^ Lyons, Jacob «Kujo» (February 15, 2012). «Krazy Kujo Interview». B-Boy Magazine. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Luis «Alien Ness» Martinez (Interviewee) (March 2009). Alien Ness’s TOP 5 THINGS HE HATES IN BREAKIN. Mane One. Event occurs at 3:00. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- ^ Won, Profo., FLOOR GANGZ, «Footwork Styles»,

- ^ «Breakdance: Crazy Legs». www.hiphoparea.com. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ «Breakdancing/B-boying/Breaking». HistoryofHipHop. March 24, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Unknown (June 9, 2016). «b-boying /breakdancing». break dancing. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2006). ««Like Old Folk Songs Handed Down from Generation to Generation»: History, Canon, and Community in B-Boy Culture». Ethnomusicology. 50 (3): 411–432. ISSN 0014-1836.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. (2006). ««Like Old Folk Songs Handed Down from Generation to Generation»: History, Canon, and Community in B-Boy Culture». Ethnomusicology. 50 (3): 411–432. ISSN 0014-1836.