Various examples of bronze artworks throughout history

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such as arsenic or silicon. These additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as strength, ductility, or machinability.

The archaeological period in which bronze was the hardest metal in widespread use is known as the Bronze Age. The beginning of the Bronze Age in western Eurasia and India is conventionally dated to the mid-4th millennium BCE (~3500 BCE), and to the early 2nd millennium BCE in China;[1] elsewhere it gradually spread across regions. The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age starting from about 1300 BCE and reaching most of Eurasia by about 500 BCE, although bronze continued to be much more widely used than it is in modern times.

Because historical artworks were often made of brasses (copper and zinc) and bronzes with different compositions, modern museum and scholarly descriptions of older artworks increasingly use the generalized term «copper alloy» instead.[2]

Etymology[edit]

The word bronze (1730–1740) is borrowed from Middle French bronze (1511), itself borrowed from Italian bronzo ‘bell metal, brass’ (13th century, transcribed in Medieval Latin as bronzium) from either:

- bróntion, back-formation from Byzantine Greek brontēsíon (βροντησίον, 11th century), perhaps from Brentḗsion (Βρεντήσιον, ‘Brindisi’, reputed for its bronze;[3][4] or originally:

- in its earliest form from Old Persian birinj, biranj (برنج, ‘brass’, modern berenj) and piring (پرنگ) ‘copper’,[5] from which also came Georgian brinǯi (ბრინჯი ), Turkish pirinç, and Armenian brinj (բրինձ), also meaning ‘bronze’.

History[edit]

Hoard of bronze socketed axes from the Bronze Age found in modern Germany. This was the top tool of the period, and also seems to have been used as a store of value.

Roman bronze nails with magical signs and inscriptions, 3rd-4th century AD.

The discovery of bronze enabled people to create metal objects that were harder and more durable than previously possible. Bronze tools, weapons, armor, and building materials such as decorative tiles were harder and more durable than their stone and copper («Chalcolithic») predecessors. Initially, bronze was made out of copper and arsenic, forming arsenic bronze, or from naturally or artificially mixed ores of copper and arsenic.[6]

The earliest artifacts so far known come from the Iranian plateau, in the 5th millennium BCE, and are smelted from native arsenical copper and copper-arsenides, such as algodonite and domeykite.[7] The earliest tin-copper-alloy artifact has been dated to c. 4650 BCE, in a Vinča culture site in Pločnik (Serbia), and believed to have been smelted from a natural tin-copper ore, stannite.[8] Other early examples date to the late 4th millennium BCE in Egypt, Susa (Iran) and some ancient sites in China, Luristan (Iran),[7] Tepe Sialk (Iran),[7] Mundigak (Afghanistan),[7] and Mesopotamia (Iraq).[citation needed]

Tin bronze was superior to arsenic bronze in that the alloying process could be more easily controlled, and the resulting alloy was stronger and easier to cast. Also, unlike arsenic, metallic tin and fumes from tin refining are not toxic.

Tin became the major non-copper ingredient of bronze in the late 3rd millennium BCE.[9]

Ores of copper and the far rarer tin are not often found together (exceptions include Cornwall in the United Kingdom, one ancient site in Thailand and one in Iran), so serious bronze work has always involved trade. Tin sources and trade in ancient times had a major influence on the development of cultures. In Europe, a major source of tin was the British deposits of ore in Cornwall, which were traded as far as Phoenicia in the eastern Mediterranean.

In many parts of the world, large hoards of bronze artifacts are found, suggesting that bronze also represented a store of value and an indicator of social status. In Europe, large hoards of bronze tools, typically socketed axes (illustrated above), are found, which mostly show no signs of wear. With Chinese ritual bronzes, which are documented in the inscriptions they carry and from other sources, the case is clear. These were made in enormous quantities for elite burials, and also used by the living for ritual offerings.

Transition to iron[edit]

Though bronze is generally harder than wrought iron, with Vickers hardness of 60–258 vs. 30–80,[10] the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age after a serious disruption of the tin trade: the population migrations of around 1200–1100 BCE reduced the shipping of tin around the Mediterranean and from Britain, limiting supplies and raising prices.[11] As the art of working in iron improved, iron became cheaper and improved in quality. As cultures advanced from hand-wrought iron to machine-forged iron (typically made with trip hammers powered by water), blacksmiths learned how to make steel. Steel is stronger than bronze and holds a sharper edge longer.[12]

Bronze was still used during the Iron Age, and has continued in use for many purposes to the modern day.

Composition[edit]

There are many different bronze alloys, but typically modern bronze is 88% copper and 12% tin.[13] Alpha bronze consists of the alpha solid solution of tin in copper. Alpha bronze alloys of 4–5% tin are used to make coins, springs, turbines and blades. Historical «bronzes» are highly variable in composition, as most metalworkers probably used whatever scrap was on hand; the metal of the 12th-century English Gloucester Candlestick is bronze containing a mixture of copper, zinc, tin, lead, nickel, iron, antimony, arsenic and an unusually large amount of silver – between 22.5% in the base and 5.76% in the pan below the candle. The proportions of this mixture suggest that the candlestick was made from a hoard of old coins. The 13th-century Benin Bronzes are in fact brass, and the 12th-century Romanesque Baptismal font at St Bartholomew’s Church, Liège is described as both bronze and brass.

In the Bronze Age, two forms of bronze were commonly used: «classic bronze», about 10% tin, was used in casting; and «mild bronze», about 6% tin, was hammered from ingots to make sheets. Bladed weapons were mostly cast from classic bronze, while helmets and armor were hammered from mild bronze.

Commercial bronze (90% copper and 10% zinc) and architectural bronze (57% copper, 3% lead, 40% zinc) are more properly regarded as brass alloys because they contain zinc as the main alloying ingredient. They are commonly used in architectural applications.[14][15]

Plastic bronze contains a significant quantity of lead, which makes for improved plasticity[16] possibly used by the ancient Greeks in their ship construction.[17]

Silicon bronze has a composition of Si: 2.80–3.80%, Mn: 0.50–1.30%, Fe: 0.80% max., Zn: 1.50% max., Pb: 0.05% max., Cu: balance.[18]

Other bronze alloys include aluminium bronze, phosphor bronze, manganese bronze, bell metal, arsenical bronze, speculum metal and cymbal alloys.

Properties[edit]

Bronzes are typically ductile alloys, considerably less brittle than cast iron. Typically bronze oxidizes only superficially; once a copper oxide (eventually becoming copper carbonate) layer is formed, the underlying metal is protected from further corrosion. This can be seen on statues from the Hellenistic period. However, if copper chlorides are formed, a corrosion-mode called «bronze disease» will eventually completely destroy it.[19] Copper-based alloys have lower melting points than steel or iron and are more readily produced from their constituent metals. They are generally about 10 percent denser than steel, although alloys using aluminum or silicon may be slightly less dense. Bronze is a better conductor of heat and electricity than most steels. The cost of copper-base alloys is generally higher than that of steels but lower than that of nickel-base alloys.

Copper and its alloys have a huge variety of uses that reflect their versatile physical, mechanical, and chemical properties. Some common examples are the high electrical conductivity of pure copper, low-friction properties of bearing bronze (bronze that has a high lead content— 6–8%), resonant qualities of bell bronze (20% tin, 80% copper), and resistance to corrosion by seawater of several bronze alloys.

The melting point of bronze varies depending on the ratio of the alloy components and is about 950 °C (1,742 °F). Bronze is usually nonmagnetic, but certain alloys containing iron or nickel may have magnetic properties.

Uses[edit]

Bronze weight with an inscribed imperial order, Qin dynasty

Industrial products of the Bunting Brass and Bronze Company, 1912

Bronze, or bronze-like alloys and mixtures, were used for coins over a longer period. Bronze was especially suitable for use in boat and ship fittings prior to the wide employment of stainless steel owing to its combination of toughness and resistance to salt water corrosion. Bronze is still commonly used in ship propellers and submerged bearings.

In the 20th century, silicon was introduced as the primary alloying element, creating an alloy with wide application in industry and the major form used in contemporary statuary. Sculptors may prefer silicon bronze because of the ready availability of silicon bronze brazing rod, which allows color-matched repair of defects in castings. Aluminum is also used for the structural metal aluminum bronze.

Bronze parts are tough and typically used for bearings, clips, electrical connectors and springs.

Bronze also has low friction against dissimilar metals, making it important for cannons prior to modern tolerancing, where iron cannonballs would otherwise stick in the barrel.[20] It is still widely used today for springs, bearings, bushings, automobile transmission pilot bearings, and similar fittings, and is particularly common in the bearings of small electric motors. Phosphor bronze is particularly suited to precision-grade bearings and springs. It is also used in guitar and piano strings.

Unlike steel, bronze struck against a hard surface will not generate sparks, so it (along with beryllium copper) is used to make hammers, mallets, wrenches and other durable tools to be used in explosive atmospheres or in the presence of flammable vapors. Bronze is used to make bronze wool for woodworking applications where steel wool would discolor oak.

Phosphor bronze is used for ships’ propellers, musical instruments, and electrical contacts.[21] Bearings are often made of bronze for its friction properties. It can be impregnated with oil to make the proprietary Oilite and similar material for bearings. Aluminum bronze is hard and wear-resistant, and is used for bearings and machine tool ways.[22]

Sculptures[edit]

Bronze is widely used for casting bronze sculptures. Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mould. Then, as the bronze cools, it shrinks a little, making it easier to separate from the mould.[23]

The Assyrian king Sennacherib (704–681 BCE) claims to have been the first to cast monumental bronze statues (of up to 30 tonnes) using two-part moulds instead of the lost-wax method.[24]

Bronze statues were regarded as the highest form of sculpture in Ancient Greek art, though survivals are few, as bronze was a valuable material in short supply in the Late Antique and medieval periods. Many of the most famous Greek bronze sculptures are known through Roman copies in marble, which were more likely to survive.

In India, bronze sculptures from the Kushana (Chausa hoard) and Gupta periods (Brahma from Mirpur-Khas, Akota Hoard, Sultanganj Buddha) and later periods (Hansi Hoard) have been found.[25] Indian Hindu artisans from the period of the Chola empire in Tamil Nadu used bronze to create intricate statues via the lost-wax casting method with ornate detailing depicting the deities of Hinduism. The art form survives to this day, with many silpis, craftsmen, working in the areas of Swamimalai and Chennai.

In antiquity other cultures also produced works of high art using bronze. For example: in Africa, the bronze heads of the Kingdom of Benin; in Europe, Grecian bronzes typically of figures from Greek mythology; in east Asia, Chinese ritual bronzes of the Shang and Zhou dynasty—more often ceremonial vessels but including some figurine examples.

Bronze continues into modern times as one of the materials of choice for monumental statuary.

-

Ancient Egyptian statuette of a Kushite pharaoh; 713–664 BCE; bronze, precious-metal leaf; height: 7.6 cm, width: 3.2 cm, depth: 3.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Etruscan tripod base for a thymiaterion (incense burner); 475-450 BCE; bronze; height: 11 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

-

Ancient Greek statue of Eros sleeping; 3rd–2nd century BCE; bronze; 41.9 × 35.6 × 85.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Gupta sculpture of Buddha offering protection; late 6th–early 7th century; copper alloy; height: 47 cm, width: 15.6 cm, diameter: 14.3 cm; from India (probably Bihar); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French or South Netherlandish Medieval caldron; 13th or 14th century; bronze and wrought iron; height: 37.5 cm, diameter: 34.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of French Rococo firedogs (chenets); circa 1750; gilt bronze; dimensions of the first: 52.7 x 48.3 x 26.7 cm, of the second: 45.1 x 49.1 x 24.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Neoclassical mantel clock (pendule de cheminée); 1757–1760; gilded and patinated bronze, oak veneered with ebony, white enamel with black numerals, and other materials; 48.3 × 69.9 × 27.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of French Chinoiserie firedogs; 1760–1770; gilt bronze; height (each): 41.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of Chinese vases with French Rococo mounts; the vases: early 18th century, the mounts: 1760–70; hard-paste porcelain with gilt-bronze mounts; 32.4 x 16.5 x 12.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Neoclassical mantel clock («Pendule Uranie»); 1764–1770; case: patinated bronze and gilded bronze, Dial: white enamel, movement: brass and steel; 71.1 × 52.1 × 26.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of mounted vases (vase à monter); 1765–70; soft-paste porcelain and French gilt bronze; 28.9 x 17.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Winter; by Jean-Antoine Houdon; 1787; bronze; 143.5 x 39.1 x 50.5 cm, height of the pedestal: 86.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mirrors[edit]

Before it became possible to produce glass with acceptably flat surfaces, bronze was a standard material for mirrors. Bronze was used for this purpose in many parts of the world, probably based on independent discoveries.

Bronze mirrors survive from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (2040–1750 BCE), and China from at least c. 550 BCE. In Europe, the Etruscans were making bronze mirrors in the sixth century BCE, and Greek and Roman mirrors followed the same pattern. Although other materials such as speculum metal had come into use, and Western glass mirrors had largely taken over, bronze mirrors were still being made in Japan and elsewhere in the eighteenth century, and are still made on a small scale in Kerala, India.

Musical instruments[edit]

Singing bowls from the 16th to 18th centuries. Annealed bronze continues to be made in the Himalayas

Bronze is the preferred metal for bells in the form of a high tin bronze alloy known as bell metal, which is typically about 23% tin.

Nearly all professional cymbals are made from bronze, which gives a desirable balance of durability and timbre. Several types of bronze are used, commonly B20 bronze, which is roughly 20% tin, 80% copper, with traces of silver, or the tougher B8 bronze made from 8% tin and 92% copper. As the tin content in a bell or cymbal rises, the timbre drops.[26]

Bronze is also used for the windings of steel and nylon strings of various stringed instruments such as the double bass, piano, harpsichord, and guitar. Bronze strings are commonly reserved on pianoforte for the lower pitch tones, as they possess a superior sustain quality to that of high-tensile steel.[27]

Bronzes of various metallurgical properties are widely used in struck idiophones around the world, notably bells, singing bowls, gongs, cymbals, and other idiophones from Asia. Examples include Tibetan singing bowls, temple bells of many sizes and shapes, Javanese gamelan, and other bronze musical instruments. The earliest bronze archeological finds in Indonesia date from 1–2 BCE, including flat plates probably suspended and struck by a wooden or bone mallet.[27][28] Ancient bronze drums from Thailand and Vietnam date back 2,000 years. Bronze bells from Thailand and Cambodia date back to 3,600 BCE.

Some companies are now making saxophones from phosphor bronze (3.5 to 10% tin and up to 1% phosphorus content).[29] Bell bronze/B20 is used to make the tone rings of many professional model banjos.[30] The tone ring is a heavy (usually 3 lb, 1.4 kg) folded or arched metal ring attached to a thick wood rim, over which a skin, or most often, a plastic membrane (or head) is stretched – it is the bell bronze that gives the banjo a crisp powerful lower register and clear bell-like treble register.[citation needed]

Biblical references[edit]

There are over 125 references to bronze (‘nehoshet’), which appears to be the Hebrew word used for copper and any of its alloys. However, the Old Testament era Hebrews are not thought to have had the capability to manufacture zinc (needed to make brass) and so it is likely that ‘nehoshet’ refers to copper and its alloys with tin, now called bronze.[31] In the King James Version, there is no use of the word ‘bronze’ and ‘nehoshet’ was translated as ‘brass’. Modern translations use ‘bronze’. Bronze (nehoshet) was used widely in the Tabernacle for items such as the bronze altar (Exodus Ch.27), bronze laver (Exodus Ch.30), utensils, and mirror (Exodus Ch.38). It was mentioned in the account of Moses holding up a bronze snake on a pole in Numbers Ch.21. In First Kings, it is mentioned that Hiram was very skilled in working with bronze, and he made many furnishings for Solomon’s Temple including pillars, capitals, stands, wheels, bowls, and plates, some of which were highly decorative (see I King 7:13-47). Bronze was also widely used as battle armor and helmet, as in the battle of David and Goliath in I Samuel 17:5-6;38 (also see II Chron. 12:10).

Coins and medals[edit]

Bronze has also been used in coins; most «copper» coins are actually bronze, with about 4 percent tin and 1 percent zinc.[32]

As with coins, bronze has been used in the manufacture of various types of medals for centuries, and «bronze medals» are known in contemporary times for being awarded for third place in sporting competitions and other events. The term is now often used for third place even when no actual bronze medal is awarded. The usage in part arose from the trio of gold, silver and bronze to represent the first three Ages of Man in Greek mythology: the Golden Age, when men lived among the gods; the Silver age, where youth lasted a hundred years; and the Bronze Age, the era of heroes. It was first adopted for a sports event at the 1904 Summer Olympics. At the 1896 event, silver was awarded to winners and bronze to runners-up, while at 1900 other prizes were given rather than medals.

Bronze is the normal material for the related form of the plaquette, normally a rectangular work of art with a scene in relief, for a collectors’ market.

See also[edit]

- Art object

- Bell founding

- Bronze and brass ornamental work

- Bronzing

- Chinese bronze inscriptions

- Dezincification resistant brass

- French Empire mantel clock

- List of copper alloys

- Ormolu

- Seagram Building, the first office building in the world to use extruded bronze on a facade

- UNS C69100 (Tungum), a bronze alloy of copper, aluminium, nickel, tin, and zinc

- Yoruba art

References[edit]

- ^ Thorp, Robert L. (2013). China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization. University of Pennsylvania Press.[page needed]

- ^ «British Museum, «Scope Note» for «copper alloy»«. British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Kahane, Henry; Kahane, Renée (1981). «Byzantium’s Impact on the West: The Linguistic Evidence». Illinois Classical Studies. 6 (2): 395.

- ^ Originally Berthelot, M.P.E. (1888). «Sur le nom du bronze chez les alchimistes grecs». Revue archéologique (in French): 294–98.

- ^ Originally Lokotsch, Karl (1927). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der europäischen Wörter orientalischen Ursprungs (in German). Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. p. 1657.

- ^

Tylecote, R.F. (1992). A History of Metallurgy, Second Edition. London: Maney Publishing, for the Institute of Materials. ISBN 978-1-902653-79-2. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. - ^ a b c d Thornton, C.; Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C.; Liezers, M.; Young, S.M.M. (2002). «On pins and needles: tracing the evolution of copper-based alloying at Tepe Yahya, Iran, via ICP-MS analysis of Common-place items». Journal of Archaeological Science. 29 (12): 1451–60. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0809.

- ^ Radivojević, Miljana; Rehren, Thilo (December 2013). «Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago». Antiquity Publications Ltd. Archived from the original on 2014-02-05.

- ^ Kaufman, Brett. «Metallurgy and Ecological Change in the Ancient Near East». Backdirt: Annual Review. 2011: 86.

- ^ Smithells Metals Reference Book, 8th Edition, ch. 22

- ^ Cramer, Clayton E. (10 December 1995). «What Caused The Iron Age?» (PDF). claytoncramer.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-28.

- ^ Sherby, O. D.; Wadsworth, J. (2000). «Ancient Blacksmiths, the Iron Age, Damascus Steels, and Modern Metallurgy» (PDF). Thermec 2000. Las Vegas, Nevada: U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-26. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Knapp, Brian. (1996) Copper, Silver and Gold. Reed Library, Australia.

- ^ «Copper alloys». Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «CDA UNS Standard Designations for Wrought and Cast Copper and Copper Alloys: Introduction». Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «plastic bronze». The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Adams, Jonathan R. (2012). «The Belgammel Ram, a Hellenistic-Roman BronzeProembolionFound off the Coast of Libya: test analysis of function, date and metallurgy, with a digital reference archive» (PDF). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 42 (1): 60–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.738.4024. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12001. S2CID 39339094. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-28.

- ^ ASTM B124 / B124M – 15. ASTM International. 2015.

- ^ «Bronze Disease, Archaeologies of the Greek Past». The Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology Classroom. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Alavudeen, A.; Venkateshwaran, N.; Winowlin Jappes, J. T. (1 January 2006). A Textbook of Engineering Materials and Metallurgy. Firewall Media. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-81-7008-957-5. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ «Resources: Standards & Properties – Copper & Copper Alloy Microstructures: Phosphor Bronze». Copper Development Association Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ «Resources: Standards & Properties – Copper & Copper Alloy Microstructures: Aluminum Bronzes». Copper Development Association Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Savage, George (1968). A Concise History of Bronzes. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. Publishers. p. 17.

- ^ for a translation of his inscription see the appendix in Dalley, Stephanie (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive World Wonder traced. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5.

- ^ Indian bronze masterpieces: the great tradition: specially published for the Festival of India, Asharani Mathur, Sonya Singh, Festival of India, Brijbasi Printers, Dec 1, 1988

- ^ Von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1993). Suspended Music: Chime-Bells in the Culture of Bronze Age China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-520-07378-4. Archived from the original on 2016-05-26.

- ^ a b McCreight, Tim (1992). Metals technic: a collection of techniques for metalsmiths. Brynmorgen Press. ISBN 0-9615984-3-3.[page needed]

- ^ LaPlantz, David (1991). Jewelry – Metalwork 1991 Survey: Visions – Concepts – Communication. S. LaPlantz. ISBN 0-942002-05-9.[page needed]

- ^ «www.sax.co.uk». Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Siminoff, Roger H. (2008). Siminoff’s Luthiers Glossary. New York: Hal Leonard. p. 13. ISBN 9781423442929.

- ^ Meschel, Susan V. «Nehoshet: Copper, Bronze or Brass? Which are Plausible in the Tanakh?». Jewish Bible Quarterly. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ «bronze | alloy». Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Archived from the original on 2016-07-30. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

External links[edit]

- Bronze at Curlie

- Bronze bells

- «Lost Wax, Found Bronze»: lost-wax casting explained

- «Flash animation of the lost-wax casting process». James Peniston Sculpture. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- Viking Bronze – Ancient and Early Medieval bronze casting

Various examples of bronze artworks throughout history

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such as arsenic or silicon. These additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as strength, ductility, or machinability.

The archaeological period in which bronze was the hardest metal in widespread use is known as the Bronze Age. The beginning of the Bronze Age in western Eurasia and India is conventionally dated to the mid-4th millennium BCE (~3500 BCE), and to the early 2nd millennium BCE in China;[1] elsewhere it gradually spread across regions. The Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age starting from about 1300 BCE and reaching most of Eurasia by about 500 BCE, although bronze continued to be much more widely used than it is in modern times.

Because historical artworks were often made of brasses (copper and zinc) and bronzes with different compositions, modern museum and scholarly descriptions of older artworks increasingly use the generalized term «copper alloy» instead.[2]

Etymology[edit]

The word bronze (1730–1740) is borrowed from Middle French bronze (1511), itself borrowed from Italian bronzo ‘bell metal, brass’ (13th century, transcribed in Medieval Latin as bronzium) from either:

- bróntion, back-formation from Byzantine Greek brontēsíon (βροντησίον, 11th century), perhaps from Brentḗsion (Βρεντήσιον, ‘Brindisi’, reputed for its bronze;[3][4] or originally:

- in its earliest form from Old Persian birinj, biranj (برنج, ‘brass’, modern berenj) and piring (پرنگ) ‘copper’,[5] from which also came Georgian brinǯi (ბრინჯი ), Turkish pirinç, and Armenian brinj (բրինձ), also meaning ‘bronze’.

History[edit]

Hoard of bronze socketed axes from the Bronze Age found in modern Germany. This was the top tool of the period, and also seems to have been used as a store of value.

Roman bronze nails with magical signs and inscriptions, 3rd-4th century AD.

The discovery of bronze enabled people to create metal objects that were harder and more durable than previously possible. Bronze tools, weapons, armor, and building materials such as decorative tiles were harder and more durable than their stone and copper («Chalcolithic») predecessors. Initially, bronze was made out of copper and arsenic, forming arsenic bronze, or from naturally or artificially mixed ores of copper and arsenic.[6]

The earliest artifacts so far known come from the Iranian plateau, in the 5th millennium BCE, and are smelted from native arsenical copper and copper-arsenides, such as algodonite and domeykite.[7] The earliest tin-copper-alloy artifact has been dated to c. 4650 BCE, in a Vinča culture site in Pločnik (Serbia), and believed to have been smelted from a natural tin-copper ore, stannite.[8] Other early examples date to the late 4th millennium BCE in Egypt, Susa (Iran) and some ancient sites in China, Luristan (Iran),[7] Tepe Sialk (Iran),[7] Mundigak (Afghanistan),[7] and Mesopotamia (Iraq).[citation needed]

Tin bronze was superior to arsenic bronze in that the alloying process could be more easily controlled, and the resulting alloy was stronger and easier to cast. Also, unlike arsenic, metallic tin and fumes from tin refining are not toxic.

Tin became the major non-copper ingredient of bronze in the late 3rd millennium BCE.[9]

Ores of copper and the far rarer tin are not often found together (exceptions include Cornwall in the United Kingdom, one ancient site in Thailand and one in Iran), so serious bronze work has always involved trade. Tin sources and trade in ancient times had a major influence on the development of cultures. In Europe, a major source of tin was the British deposits of ore in Cornwall, which were traded as far as Phoenicia in the eastern Mediterranean.

In many parts of the world, large hoards of bronze artifacts are found, suggesting that bronze also represented a store of value and an indicator of social status. In Europe, large hoards of bronze tools, typically socketed axes (illustrated above), are found, which mostly show no signs of wear. With Chinese ritual bronzes, which are documented in the inscriptions they carry and from other sources, the case is clear. These were made in enormous quantities for elite burials, and also used by the living for ritual offerings.

Transition to iron[edit]

Though bronze is generally harder than wrought iron, with Vickers hardness of 60–258 vs. 30–80,[10] the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age after a serious disruption of the tin trade: the population migrations of around 1200–1100 BCE reduced the shipping of tin around the Mediterranean and from Britain, limiting supplies and raising prices.[11] As the art of working in iron improved, iron became cheaper and improved in quality. As cultures advanced from hand-wrought iron to machine-forged iron (typically made with trip hammers powered by water), blacksmiths learned how to make steel. Steel is stronger than bronze and holds a sharper edge longer.[12]

Bronze was still used during the Iron Age, and has continued in use for many purposes to the modern day.

Composition[edit]

There are many different bronze alloys, but typically modern bronze is 88% copper and 12% tin.[13] Alpha bronze consists of the alpha solid solution of tin in copper. Alpha bronze alloys of 4–5% tin are used to make coins, springs, turbines and blades. Historical «bronzes» are highly variable in composition, as most metalworkers probably used whatever scrap was on hand; the metal of the 12th-century English Gloucester Candlestick is bronze containing a mixture of copper, zinc, tin, lead, nickel, iron, antimony, arsenic and an unusually large amount of silver – between 22.5% in the base and 5.76% in the pan below the candle. The proportions of this mixture suggest that the candlestick was made from a hoard of old coins. The 13th-century Benin Bronzes are in fact brass, and the 12th-century Romanesque Baptismal font at St Bartholomew’s Church, Liège is described as both bronze and brass.

In the Bronze Age, two forms of bronze were commonly used: «classic bronze», about 10% tin, was used in casting; and «mild bronze», about 6% tin, was hammered from ingots to make sheets. Bladed weapons were mostly cast from classic bronze, while helmets and armor were hammered from mild bronze.

Commercial bronze (90% copper and 10% zinc) and architectural bronze (57% copper, 3% lead, 40% zinc) are more properly regarded as brass alloys because they contain zinc as the main alloying ingredient. They are commonly used in architectural applications.[14][15]

Plastic bronze contains a significant quantity of lead, which makes for improved plasticity[16] possibly used by the ancient Greeks in their ship construction.[17]

Silicon bronze has a composition of Si: 2.80–3.80%, Mn: 0.50–1.30%, Fe: 0.80% max., Zn: 1.50% max., Pb: 0.05% max., Cu: balance.[18]

Other bronze alloys include aluminium bronze, phosphor bronze, manganese bronze, bell metal, arsenical bronze, speculum metal and cymbal alloys.

Properties[edit]

Bronzes are typically ductile alloys, considerably less brittle than cast iron. Typically bronze oxidizes only superficially; once a copper oxide (eventually becoming copper carbonate) layer is formed, the underlying metal is protected from further corrosion. This can be seen on statues from the Hellenistic period. However, if copper chlorides are formed, a corrosion-mode called «bronze disease» will eventually completely destroy it.[19] Copper-based alloys have lower melting points than steel or iron and are more readily produced from their constituent metals. They are generally about 10 percent denser than steel, although alloys using aluminum or silicon may be slightly less dense. Bronze is a better conductor of heat and electricity than most steels. The cost of copper-base alloys is generally higher than that of steels but lower than that of nickel-base alloys.

Copper and its alloys have a huge variety of uses that reflect their versatile physical, mechanical, and chemical properties. Some common examples are the high electrical conductivity of pure copper, low-friction properties of bearing bronze (bronze that has a high lead content— 6–8%), resonant qualities of bell bronze (20% tin, 80% copper), and resistance to corrosion by seawater of several bronze alloys.

The melting point of bronze varies depending on the ratio of the alloy components and is about 950 °C (1,742 °F). Bronze is usually nonmagnetic, but certain alloys containing iron or nickel may have magnetic properties.

Uses[edit]

Bronze weight with an inscribed imperial order, Qin dynasty

Industrial products of the Bunting Brass and Bronze Company, 1912

Bronze, or bronze-like alloys and mixtures, were used for coins over a longer period. Bronze was especially suitable for use in boat and ship fittings prior to the wide employment of stainless steel owing to its combination of toughness and resistance to salt water corrosion. Bronze is still commonly used in ship propellers and submerged bearings.

In the 20th century, silicon was introduced as the primary alloying element, creating an alloy with wide application in industry and the major form used in contemporary statuary. Sculptors may prefer silicon bronze because of the ready availability of silicon bronze brazing rod, which allows color-matched repair of defects in castings. Aluminum is also used for the structural metal aluminum bronze.

Bronze parts are tough and typically used for bearings, clips, electrical connectors and springs.

Bronze also has low friction against dissimilar metals, making it important for cannons prior to modern tolerancing, where iron cannonballs would otherwise stick in the barrel.[20] It is still widely used today for springs, bearings, bushings, automobile transmission pilot bearings, and similar fittings, and is particularly common in the bearings of small electric motors. Phosphor bronze is particularly suited to precision-grade bearings and springs. It is also used in guitar and piano strings.

Unlike steel, bronze struck against a hard surface will not generate sparks, so it (along with beryllium copper) is used to make hammers, mallets, wrenches and other durable tools to be used in explosive atmospheres or in the presence of flammable vapors. Bronze is used to make bronze wool for woodworking applications where steel wool would discolor oak.

Phosphor bronze is used for ships’ propellers, musical instruments, and electrical contacts.[21] Bearings are often made of bronze for its friction properties. It can be impregnated with oil to make the proprietary Oilite and similar material for bearings. Aluminum bronze is hard and wear-resistant, and is used for bearings and machine tool ways.[22]

Sculptures[edit]

Bronze is widely used for casting bronze sculptures. Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mould. Then, as the bronze cools, it shrinks a little, making it easier to separate from the mould.[23]

The Assyrian king Sennacherib (704–681 BCE) claims to have been the first to cast monumental bronze statues (of up to 30 tonnes) using two-part moulds instead of the lost-wax method.[24]

Bronze statues were regarded as the highest form of sculpture in Ancient Greek art, though survivals are few, as bronze was a valuable material in short supply in the Late Antique and medieval periods. Many of the most famous Greek bronze sculptures are known through Roman copies in marble, which were more likely to survive.

In India, bronze sculptures from the Kushana (Chausa hoard) and Gupta periods (Brahma from Mirpur-Khas, Akota Hoard, Sultanganj Buddha) and later periods (Hansi Hoard) have been found.[25] Indian Hindu artisans from the period of the Chola empire in Tamil Nadu used bronze to create intricate statues via the lost-wax casting method with ornate detailing depicting the deities of Hinduism. The art form survives to this day, with many silpis, craftsmen, working in the areas of Swamimalai and Chennai.

In antiquity other cultures also produced works of high art using bronze. For example: in Africa, the bronze heads of the Kingdom of Benin; in Europe, Grecian bronzes typically of figures from Greek mythology; in east Asia, Chinese ritual bronzes of the Shang and Zhou dynasty—more often ceremonial vessels but including some figurine examples.

Bronze continues into modern times as one of the materials of choice for monumental statuary.

-

Ancient Egyptian statuette of a Kushite pharaoh; 713–664 BCE; bronze, precious-metal leaf; height: 7.6 cm, width: 3.2 cm, depth: 3.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Etruscan tripod base for a thymiaterion (incense burner); 475-450 BCE; bronze; height: 11 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

-

Ancient Greek statue of Eros sleeping; 3rd–2nd century BCE; bronze; 41.9 × 35.6 × 85.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Gupta sculpture of Buddha offering protection; late 6th–early 7th century; copper alloy; height: 47 cm, width: 15.6 cm, diameter: 14.3 cm; from India (probably Bihar); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French or South Netherlandish Medieval caldron; 13th or 14th century; bronze and wrought iron; height: 37.5 cm, diameter: 34.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of French Rococo firedogs (chenets); circa 1750; gilt bronze; dimensions of the first: 52.7 x 48.3 x 26.7 cm, of the second: 45.1 x 49.1 x 24.8 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Neoclassical mantel clock (pendule de cheminée); 1757–1760; gilded and patinated bronze, oak veneered with ebony, white enamel with black numerals, and other materials; 48.3 × 69.9 × 27.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of French Chinoiserie firedogs; 1760–1770; gilt bronze; height (each): 41.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of Chinese vases with French Rococo mounts; the vases: early 18th century, the mounts: 1760–70; hard-paste porcelain with gilt-bronze mounts; 32.4 x 16.5 x 12.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

French Neoclassical mantel clock («Pendule Uranie»); 1764–1770; case: patinated bronze and gilded bronze, Dial: white enamel, movement: brass and steel; 71.1 × 52.1 × 26.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Pair of mounted vases (vase à monter); 1765–70; soft-paste porcelain and French gilt bronze; 28.9 x 17.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Winter; by Jean-Antoine Houdon; 1787; bronze; 143.5 x 39.1 x 50.5 cm, height of the pedestal: 86.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mirrors[edit]

Before it became possible to produce glass with acceptably flat surfaces, bronze was a standard material for mirrors. Bronze was used for this purpose in many parts of the world, probably based on independent discoveries.

Bronze mirrors survive from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (2040–1750 BCE), and China from at least c. 550 BCE. In Europe, the Etruscans were making bronze mirrors in the sixth century BCE, and Greek and Roman mirrors followed the same pattern. Although other materials such as speculum metal had come into use, and Western glass mirrors had largely taken over, bronze mirrors were still being made in Japan and elsewhere in the eighteenth century, and are still made on a small scale in Kerala, India.

Musical instruments[edit]

Singing bowls from the 16th to 18th centuries. Annealed bronze continues to be made in the Himalayas

Bronze is the preferred metal for bells in the form of a high tin bronze alloy known as bell metal, which is typically about 23% tin.

Nearly all professional cymbals are made from bronze, which gives a desirable balance of durability and timbre. Several types of bronze are used, commonly B20 bronze, which is roughly 20% tin, 80% copper, with traces of silver, or the tougher B8 bronze made from 8% tin and 92% copper. As the tin content in a bell or cymbal rises, the timbre drops.[26]

Bronze is also used for the windings of steel and nylon strings of various stringed instruments such as the double bass, piano, harpsichord, and guitar. Bronze strings are commonly reserved on pianoforte for the lower pitch tones, as they possess a superior sustain quality to that of high-tensile steel.[27]

Bronzes of various metallurgical properties are widely used in struck idiophones around the world, notably bells, singing bowls, gongs, cymbals, and other idiophones from Asia. Examples include Tibetan singing bowls, temple bells of many sizes and shapes, Javanese gamelan, and other bronze musical instruments. The earliest bronze archeological finds in Indonesia date from 1–2 BCE, including flat plates probably suspended and struck by a wooden or bone mallet.[27][28] Ancient bronze drums from Thailand and Vietnam date back 2,000 years. Bronze bells from Thailand and Cambodia date back to 3,600 BCE.

Some companies are now making saxophones from phosphor bronze (3.5 to 10% tin and up to 1% phosphorus content).[29] Bell bronze/B20 is used to make the tone rings of many professional model banjos.[30] The tone ring is a heavy (usually 3 lb, 1.4 kg) folded or arched metal ring attached to a thick wood rim, over which a skin, or most often, a plastic membrane (or head) is stretched – it is the bell bronze that gives the banjo a crisp powerful lower register and clear bell-like treble register.[citation needed]

Biblical references[edit]

There are over 125 references to bronze (‘nehoshet’), which appears to be the Hebrew word used for copper and any of its alloys. However, the Old Testament era Hebrews are not thought to have had the capability to manufacture zinc (needed to make brass) and so it is likely that ‘nehoshet’ refers to copper and its alloys with tin, now called bronze.[31] In the King James Version, there is no use of the word ‘bronze’ and ‘nehoshet’ was translated as ‘brass’. Modern translations use ‘bronze’. Bronze (nehoshet) was used widely in the Tabernacle for items such as the bronze altar (Exodus Ch.27), bronze laver (Exodus Ch.30), utensils, and mirror (Exodus Ch.38). It was mentioned in the account of Moses holding up a bronze snake on a pole in Numbers Ch.21. In First Kings, it is mentioned that Hiram was very skilled in working with bronze, and he made many furnishings for Solomon’s Temple including pillars, capitals, stands, wheels, bowls, and plates, some of which were highly decorative (see I King 7:13-47). Bronze was also widely used as battle armor and helmet, as in the battle of David and Goliath in I Samuel 17:5-6;38 (also see II Chron. 12:10).

Coins and medals[edit]

Bronze has also been used in coins; most «copper» coins are actually bronze, with about 4 percent tin and 1 percent zinc.[32]

As with coins, bronze has been used in the manufacture of various types of medals for centuries, and «bronze medals» are known in contemporary times for being awarded for third place in sporting competitions and other events. The term is now often used for third place even when no actual bronze medal is awarded. The usage in part arose from the trio of gold, silver and bronze to represent the first three Ages of Man in Greek mythology: the Golden Age, when men lived among the gods; the Silver age, where youth lasted a hundred years; and the Bronze Age, the era of heroes. It was first adopted for a sports event at the 1904 Summer Olympics. At the 1896 event, silver was awarded to winners and bronze to runners-up, while at 1900 other prizes were given rather than medals.

Bronze is the normal material for the related form of the plaquette, normally a rectangular work of art with a scene in relief, for a collectors’ market.

See also[edit]

- Art object

- Bell founding

- Bronze and brass ornamental work

- Bronzing

- Chinese bronze inscriptions

- Dezincification resistant brass

- French Empire mantel clock

- List of copper alloys

- Ormolu

- Seagram Building, the first office building in the world to use extruded bronze on a facade

- UNS C69100 (Tungum), a bronze alloy of copper, aluminium, nickel, tin, and zinc

- Yoruba art

References[edit]

- ^ Thorp, Robert L. (2013). China in the Early Bronze Age: Shang Civilization. University of Pennsylvania Press.[page needed]

- ^ «British Museum, «Scope Note» for «copper alloy»«. British Museum. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Kahane, Henry; Kahane, Renée (1981). «Byzantium’s Impact on the West: The Linguistic Evidence». Illinois Classical Studies. 6 (2): 395.

- ^ Originally Berthelot, M.P.E. (1888). «Sur le nom du bronze chez les alchimistes grecs». Revue archéologique (in French): 294–98.

- ^ Originally Lokotsch, Karl (1927). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der europäischen Wörter orientalischen Ursprungs (in German). Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. p. 1657.

- ^

Tylecote, R.F. (1992). A History of Metallurgy, Second Edition. London: Maney Publishing, for the Institute of Materials. ISBN 978-1-902653-79-2. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. - ^ a b c d Thornton, C.; Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C.; Liezers, M.; Young, S.M.M. (2002). «On pins and needles: tracing the evolution of copper-based alloying at Tepe Yahya, Iran, via ICP-MS analysis of Common-place items». Journal of Archaeological Science. 29 (12): 1451–60. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0809.

- ^ Radivojević, Miljana; Rehren, Thilo (December 2013). «Tainted ores and the rise of tin bronzes in Eurasia, c. 6500 years ago». Antiquity Publications Ltd. Archived from the original on 2014-02-05.

- ^ Kaufman, Brett. «Metallurgy and Ecological Change in the Ancient Near East». Backdirt: Annual Review. 2011: 86.

- ^ Smithells Metals Reference Book, 8th Edition, ch. 22

- ^ Cramer, Clayton E. (10 December 1995). «What Caused The Iron Age?» (PDF). claytoncramer.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-28.

- ^ Sherby, O. D.; Wadsworth, J. (2000). «Ancient Blacksmiths, the Iron Age, Damascus Steels, and Modern Metallurgy» (PDF). Thermec 2000. Las Vegas, Nevada: U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-26. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Knapp, Brian. (1996) Copper, Silver and Gold. Reed Library, Australia.

- ^ «Copper alloys». Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «CDA UNS Standard Designations for Wrought and Cast Copper and Copper Alloys: Introduction». Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ «plastic bronze». The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Adams, Jonathan R. (2012). «The Belgammel Ram, a Hellenistic-Roman BronzeProembolionFound off the Coast of Libya: test analysis of function, date and metallurgy, with a digital reference archive» (PDF). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 42 (1): 60–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.738.4024. doi:10.1111/1095-9270.12001. S2CID 39339094. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-28.

- ^ ASTM B124 / B124M – 15. ASTM International. 2015.

- ^ «Bronze Disease, Archaeologies of the Greek Past». The Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology Classroom. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Alavudeen, A.; Venkateshwaran, N.; Winowlin Jappes, J. T. (1 January 2006). A Textbook of Engineering Materials and Metallurgy. Firewall Media. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-81-7008-957-5. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ «Resources: Standards & Properties – Copper & Copper Alloy Microstructures: Phosphor Bronze». Copper Development Association Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ «Resources: Standards & Properties – Copper & Copper Alloy Microstructures: Aluminum Bronzes». Copper Development Association Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ Savage, George (1968). A Concise History of Bronzes. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. Publishers. p. 17.

- ^ for a translation of his inscription see the appendix in Dalley, Stephanie (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive World Wonder traced. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5.

- ^ Indian bronze masterpieces: the great tradition: specially published for the Festival of India, Asharani Mathur, Sonya Singh, Festival of India, Brijbasi Printers, Dec 1, 1988

- ^ Von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1993). Suspended Music: Chime-Bells in the Culture of Bronze Age China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-520-07378-4. Archived from the original on 2016-05-26.

- ^ a b McCreight, Tim (1992). Metals technic: a collection of techniques for metalsmiths. Brynmorgen Press. ISBN 0-9615984-3-3.[page needed]

- ^ LaPlantz, David (1991). Jewelry – Metalwork 1991 Survey: Visions – Concepts – Communication. S. LaPlantz. ISBN 0-942002-05-9.[page needed]

- ^ «www.sax.co.uk». Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Siminoff, Roger H. (2008). Siminoff’s Luthiers Glossary. New York: Hal Leonard. p. 13. ISBN 9781423442929.

- ^ Meschel, Susan V. «Nehoshet: Copper, Bronze or Brass? Which are Plausible in the Tanakh?». Jewish Bible Quarterly. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ «bronze | alloy». Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Archived from the original on 2016-07-30. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

External links[edit]

- Bronze at Curlie

- Bronze bells

- «Lost Wax, Found Bronze»: lost-wax casting explained

- «Flash animation of the lost-wax casting process». James Peniston Sculpture. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- Viking Bronze – Ancient and Early Medieval bronze casting

БРОНЗЫ

- БРОНЗЫ

-

(франц. ед. ч. bronze), сплавы на основе меди, в к-рых главным легирующим элементом м. б. любой хим. элемент, за исключением Zn и Ni. Различают оловянные Б. (до ~ 19% Sn), алюминиевые (4-11 % А1), бериллиевые (до ~ 2% Be) и др. Оловянная Б.-древнейший сплав, выплавленный человеком.

Б. получают сплавлением меди с легирующими элементами, обычно в электрич. индукционных печах. По способу обработки Б. подразделяют на деформируемые и литейные. Из первых отливают плоские или круглые слитки, к-рые подвергают горячей и затем холодной обработке давлением (прокатке, прессованию) для получения листов, лент, прутков и труб. Б. плавятся при более низких т-рах, чем медь; они хорошо заполняют литейную форму.

Легирующие элементы могут образовывать с медью твердый р-р или хим. соед. (напр., Cu31Sn8, Cu3P). Твердый раствор из-за искажения атомами легирующих элементов кристаллич. решетки меди тверже ее. Хим. соед. еще более тверды, но очень хрупки; их объемная доля в Б. значительно меньше, чем доля твердого р-ра. Для Б. характерны:

150-600МПа, относительное удлинение 3-10% (литейные) и 20-50% (деформируемые), твердость по Бринеллю 600-2000 МПа. Нек-рые Б. подвергают закалке и упрочняющему старению. Напр., при закалке в воде Б., содержащей 2% Be (от т-ры 780

Химическая энциклопедия. — М.: Советская энциклопедия.

.

1988.

Смотреть что такое «БРОНЗЫ» в других словарях:

-

Бронзы — Статуэтка, отлитая из бронзы Шлем из бронзы Бронза сплав меди, обычно с оловом как основным легирующим элементом, но применяются и сплавы с алюминием, кремнием, бериллием, свинцом и другими элементами, за исключением цинка и никеля. Название… … Википедия

-

бронзы — сплавы на основе меди, в которых легирующими добавками могут быть любые химические элементы, кроме цинка и никеля. Различают оловянные (до 19 % Sn), алюминиевые (4 12 % Аl), бериллиевые (до 2 % Be) и другие бронзы. Первая бронза, выплавленная… … Энциклопедия техники

-

БРОНЗЫ ИЗ РИАЧЕ — две бронзовые статуи обнаженных воинов несколько больше натуральной величины, подняты из моря близ Риаче (Юж. Италия). Вероятно, выполнены в Афинах в сер. 5 в. до н. э. Хранятся в Национальном археологическом музее г. Реджо ди Калабрия … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

БРОНЗЫ ИЗ РИАЧЕ — БРОНЗЫ ИЗ РИАЧЕ, две бронзовые статуи обнаженных воинов несколько больше натуральной величины, подняты из моря близ Риаче (Юж. Италия). Вероятно, выполнены в Афинах в сер. 5 в. до н. э. Хранятся в Национальном археологическом музее г. Реджо ди… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Бронзы эпоха — второй крупный период в археол. периодизации первобытной истории, характеризующийся массовым освоением металлургии бронзы, изготовлением из нее орудий труда, оружия и украшений, употреблявшихся наряду с каменными или вместо них. Точные… … Уральская историческая энциклопедия

-

Безоловянные бронзы — бронзы, не содержащие Sn и применяемые для литых полуфабрикатов и изделий. Для фасонных отливок применяют безоловянные бронзы следующих марок: БрА9Мц2Л, БрАl0Мц2Л, БрА9Ж3Л, БрАl0Ж3Мц2, БрАl0Ж4Н4Л, БрАl1Ж6Н6, БрА9Ж4НМц1, БрС30, БрА7Мц15Ж3Н2Ц2,… … Энциклопедический словарь по металлургии

-

Безоловянные бронзы в чушках — бронзы, предназначенной для изготовления отливок из безоловянных бронз. Существует три марки бронз: БрАЮЖЗр, БрАЮЖЗ, БрАl0ЖЗМц2. Буквы и цифры Смотри Безоловянные бронзы; буква р рафинированная. Масса чушек до 42 кг. ГОСТ 17328 78 Е … Энциклопедический словарь по металлургии

-

БЕЗОЛОВЯННЫЕ БРОНЗЫ — бронзы, не содержащие Sn и применяемые для литых полуфабрикатов и изделий. Для фасонных отливок применяют безоловянные бронзы следующих марок: БрА9Мц2Л, БрА10Мц2Л, БрА9Ж3Л, БрА10Ж3Мц2, БрА10Ж4Н4Л, БрА11Ж6Н6, БрА9Ж4НМц1, БрС30, БрА7Мц15Ж3Н2Ц2,… … Металлургический словарь

-

БЕЗОЛОВЯННЫЕ БРОНЗЫ В ЧУШКАХ — бронзы, предназначенные для изготовления отливок из безоловянных бронз. Существует три марки бронз: БрА10Ж3р, БрА10Ж3, БрА10Ж3Мц2. Буквы и цифры смотреть Безоловянные бронзы; буква р рафинированная. Масса чушек до 42 кг. ГОСТ 17328 78 Е … Металлургический словарь

-

БРОНЗЫ ОКСИДНЫЕ — нестехиометрич. соед. общей ф лы М х ЭО n, где М = Н, Н 3 О, NH4 или металл, чаще всего щелочной, Э переходной металл IV VIII гр. периодич. системы (Ti, V, Nb, Mo, W, Mn, Re, Pt или др.), 0<х 1. Кристаллич. в ва с металлич. блеском и… … Химическая энциклопедия

Бронза представляет собой материал, получаемый путем соединения олова и меди. Помимо данных компонентов, в состав бронзы могут быть добавлены цинк, свинец, марганец, алюминий. Однако содержание меди в таких случаях не меняется, вне зависимости от дополнительных компонентов.

По химическому составу бронза подразделяется на два вида:

- оловянные (в составе преобладает олово);

- безоловянные (данный металл имеется в небольших количествах).

Сплавы также дифференцируются по виду обработки:

- деформируемые (для производства деталей путем давления или штамповки).

- литейные (подходят в качестве литья).

Сплавов, в которые имеются дополнительные компоненты, насчитывается огромное множество. Бронзу можно определить по цвету, на который также влияет наличие примесей. Однако классифицировать бронзу можно благодаря обозначению, которое должно соответствовать принятому стандарту. В технической документации приводятся таблицы, где указываются буквенные обозначение. Таким образом, при проектировании или покупке материалов можно узнать, какой тип бронзы подойдет лучше всего.

В качестве примера рассмотрим обозначение, которое часто встречается в производстве – БрАЖ9-4. «Бр» говорит о том, что в составе справа имеется традиционная бронза. Буквы «А» и «Ж» свидетельствуют о том, что материал изготавливается с использованием алюминия и железа. Для других металлов применяются соответствующие буквенные обозначения.

Разновидности сплавов из бронзы, их применение

Получать бронзу начали еще наши предки. Опытным путем было выяснено, что при изменении компонентов происходит изменение характеристик сплава. В частности, за счет олова изменяется ковкость материала. Если повысить его содержание, то материал становится более твердым. Наибольшие значения этого показателя у бериллиевой бронзы. В процессе закалки она приобретает пластичность. Поэтому ее используют при изготовлении элементов, где требуется определенная упругость. Это мембраны, пружины и рессоры.

Алюминиевая бронза позволяет получать металлические трубы и ленты, которые подвергаются разрезанию. При этом получаемые изделия не подвержены ржавчине даже при воздействии соленой воды.

Бронза с добавлением свинца востребована при производстве подшипников, поскольку способна сопротивляться ударным нагрузкам.

Кремнецинковая бронза позволяет изготавливать детали сложной конфигурации. Этот материал обладает хорошими текучими свойствами, поэтому им можно заполнить различные формы. В то же время такой сплав не имеет склонности к образованию искр.

Её использовали как в военных целях — для изготовления холодного оружия, пушек и ядер для них, так и для создания прекрасных произведений искусства — ювелирных украшений и скульптур.

- История

- Состав бронзы

- Особенности бронзы и свойства

- Виды бронзы и характеристики

- Области применения и маркировка

История

Бронзовые артефакты, найденные в майкопских курганах, были изготовлены в основном из сплава меди и мышьяка, поэтому считается, что исторически первыми были именно такие сплавы, называемые мышьяковистыми бронзами.

Она ничем не уступала по своим свойствам сплавам меди с оловом или свинцом, и даже превосходила их по ряду характеристик. Она широко применялась в различных областях человеческой деятельности тех времён, начиная от изготовления ответственных деталей и заканчивая ювелирными изделиями.

Состав бронзы

Состав бронзы зависит от марки сплава и указывается в её обозначении. Например, в состав сплава, имеющего маркировку БрАМц7−1, входят 7% алюминия, 1% марганца и 92% меди.

Таким образом, основным компонентом этого металла является медь (от 35% до 90% и выше). Вторым же компонентом может являться либо мышьяк, либо олово или бериллий, свинец, алюминий, кремний и другие компоненты. Для придания особых свойств в сплав могут добавляться дополнительные компоненты — цинк, железо, никель, марганец, фосфор и другие.

Особенности бронзы и свойства

Так, золотистая бронза получится, если в составе сплава будет около 85% меди, а при уменьшении её количества до 50% получится сплав, имеющий серебристый цвет. Уменьшение же количества меди до 35% и ниже приведёт к получению на выходе серой и даже чёрной бронзы, а увеличение количества меди до 90% и выше приведёт к образованию красной бронзы.

Одной из старых марок бронзовых сплавов является колокольная бронза, применяемая и поныне для литья колоколов. Она содержит 20% олова и 80% меди. Её недостаток — повышенная хрупкость из-за наличия в сплаве большого содержания олова.

Как уже было упомянуто выше, наиболее используемыми являются сплавы меди и олова с добавлением небольшого количества других компонентов. Широкое применение таких сплавов обусловлено, прежде всего, исторически сложившимися причинами, которые привели к вытеснению мышьяковой бронзы из производства.

Такими причинами являются следующие:

- выработка за многие века месторождений теннантита и других блёклых руд, богатых медью и мышьяком. Такие руды были наиболее удобны для выделки мышьяковой бронзы, так как залегали не очень глубоко, что делало процесс производства более дешёвым по сравнению с другими источниками меди и мышьяка;

- высокая токсичность производства такой бронзы, вызванная наличием в месторождениях мышьяка, что с неизбежностью приводило к потере здоровья и дальнейшей способности трудиться у опытных металлургов и кузнецов;

- непригодность металлургического брака и сломанных изделий из мышьяковой бронзы для дальнейшей переплавки на сортовой металл. В лучшем случае такие изделия шли на изготовление бижутерии или неответственных деталей.

Пришедшие на смену мышьяковым бронзам сплавы меди и олова хоть и отличались большей дороговизной производства, но были экономически предпочтительны, так как развитие гужевого транспорта и налаживание вследствие этого торговых связей между городами и странами приводило к увеличению импорта немышьяковой бронзы.

Виды бронзы и характеристики

Таким образом, существуют следующие виды:

- безоловянная. К ней относят бронзу, в которой вторыми компонентами являются алюминий, кремний, бериллий и другие металлы и неметаллы. Каждый из этих компонентов придаёт ей особые свойства. Например, алюминий наделяет сплав повышенными антифрикционными свойствами и высокой коррозионной устойчивостью, бериллий повышает прочность и твёрдость, а кремний и цинк улучшают её текучесть и устойчивость к истиранию;

- оловянная. Медно-оловянный сплав, в котором медь преобладает. Является одним из первых, освоенных человеком. Обладает высокой, по сравнению с чистой медью, твёрдостью и прочностью, а также более легкоплавка. В таких сплавах олово всегда является вторым по количеству после меди и основным легирующим компонентом.

Третьими же по количеству являются такие дополнительные компоненты, как мышьяк, цинк и свинец. Этот металл из-за очень низкой усадки в основном предназначается для литья, так как с трудом поддаётся обработке давлением, резанию и заточке. Даже склонность к ликвации и низкая текучесть не мешают использовать этот сплав для изготовления конфигурационно-сложных отливок, в том числе и в художественном литье.

Бронза с добавлением цинка носит название «адмиралтейской» и используется для изготовления деталей, имеющих частый или постоянный контакт с морской водой (судостроение). Такая особенность связана с тем, что цинк придаёт сплаву повышенную коррозионную стойкость в указанной среде.

Однако, для придания бронзе коррозионной стойкости в солёной морской воде её всё чаще обогащают алюминием и никелем. Такие сплавы, часто называемые «морскими», идут на изготовление элементов нефтяных платформ, работающих на морских и океанских шельфах.

Чтобы придать бронзе дополнительные характеристики, в неё легируют небольшие количества фосфора, серебра, цинка, мышьяка, марганца и других компонентов. Так, внесение небольшого количества серебра повышает электропроводность бронзы и делает её сравнимой с электропроводностью меди.

Области применения и маркировка

По простой маркировке можно узнать их состав. Характерным её признаком в обозначении являются буквы «Бр», что означает «Бронза».

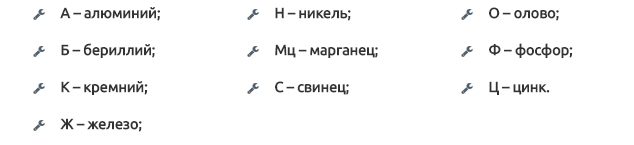

Далее за ними следуют буквы, обозначающие, помимо меди, наличие соответствующих компонентов. Эти буквенные обозначения, установленные нормативными документами, следующие: А — алюминий, Б — бериллий, К — кремний, Ж — железо, Н — никель, Мц — марганец, Мг — магний, С — свинец, О — олово, Т — титан, Ф — фосфор, Ц — цинк.

После буквенных обозначений через дефисы идут числа, обозначающие процентное содержание каждого компонента (после меди). А также применяются обозначения, в которых после каждой буквы указывается процентное содержание того или иного компонента. Чтобы узнать содержание меди, нужно из 100% вычесть процентное содержание всех компонентов.

Вот примеры маркировок и их расшифровок: БрО5Ц6С5 — бронзовый сплав, в котором содержание олова составляет 5%, цинка — 6%, свинца — 5%, меди — 84%; БрО3Ц8С4Н1 — содержание олова — 3%, цинка — 8%, свинца — 4%, никеля — 1%, меди — 84%; БрО10Ф1 — содержание олова — 10%, фосфора — 1%, меди — 89%; БрБ2 — содержание бериллия — 2%, меди — 98%; БрАЖМц10−3−1,5 — содержание алюминия — 10%, железа — 3%, марганца — 1,5%, меди — 85,5%; БрАЖН10−4−4 — содержание алюминия — 10%, железа — 4%, никеля — 4%, меди — 82%.

Благодаря своим разнообразным свойствам этот металл находит самое широкое применение в различных сферах. Из него изготавливают следующие изделия:

- элементы декора (светильники, статуэтки, подсвечники, пепельницы, решётки, украшения перил и прочие);

- различную фурнитуру (замки, ручки, накладные петли, краны, смесители и прочую сантехнику);

- детали машин и механизмов (втулки, уплотнители, шестерни, подшипники, части аппаратуры, работающие под водой);

- детали для высокоточной техники, навигационных приборов, схем автомобилей;

- многочисленные фитинги (отводы, углы, переходники, муфты, тройники и прочее);

- в незначительном количестве ювелирные украшения.

Бронза широко применяется в ракетной технике и машиностроении, авиации и судостроении. Из неё делают предметы высокохудожественного искусства для театров, залов и дворцов, отливают памятники и скульптуры.

Благодаря развитию металлургии, этот металл приобретает всё новые и необычные свойства, недоступные кузнецам и металлургам прошлого. Изобретённый древними, сплав продолжает исправно служить человечеству и прогрессу на протяжении многих и многих веков.

- Основные легирующие добавки

- Марки и сферы их применения

- Как производят бронзу

- Естественное и искусственное патинирование

Своей высокой популярностью бронза обязана не только своим декоративным характеристикам, но и целому ряду других свойств. Между тем немногие из тех, кто использует данный металл, могут назвать состав бронзы, а ведь именно он определяет характеристики этого медного сплава.

Бронза литейная БрОЗЦ8С4Н1 в чушках используется для производства антифрикционных деталей

Основные легирующие добавки

Бронза – это цветной сплав на основе меди, определяющей большую часть его характеристик. Производить и использовать бронзу для изделий различного назначения человек начал еще с древних времен, о чем свидетельствуют результаты археологических раскопок. Изначально использовалась бронза, состав которой был обогащен оловом. К сплавам данного типа относится, в частности, так называемая колокольная бронза (из нее на протяжении многих веков отливали колокола).

Кроме бронз, содержащих в своем составе олово, сегодня активно используются и сплавы меди, в которых данного химического элемента нет. Вместо олова в качестве основной легирующей добавки в таких медных сплавах применяются:

- бериллий, который придает бронзе повышенную прочность;

- кремний и цинк – элементы, благодаря которым поверхность бронзового изделия становится очень устойчивой к истиранию и улучшается текучесть бронзы, что особенно важно для выполнения литейных операций;

- свинец, придающий бронзе устойчивость к коррозии;

- алюминий, наделяющий бронзу достойными антифрикционными свойствами и высокой устойчивостью к коррозии.

На вопрос же о том, какой металл обязательно присутствует в любой бронзе, можно ответить однозначно: это медь.

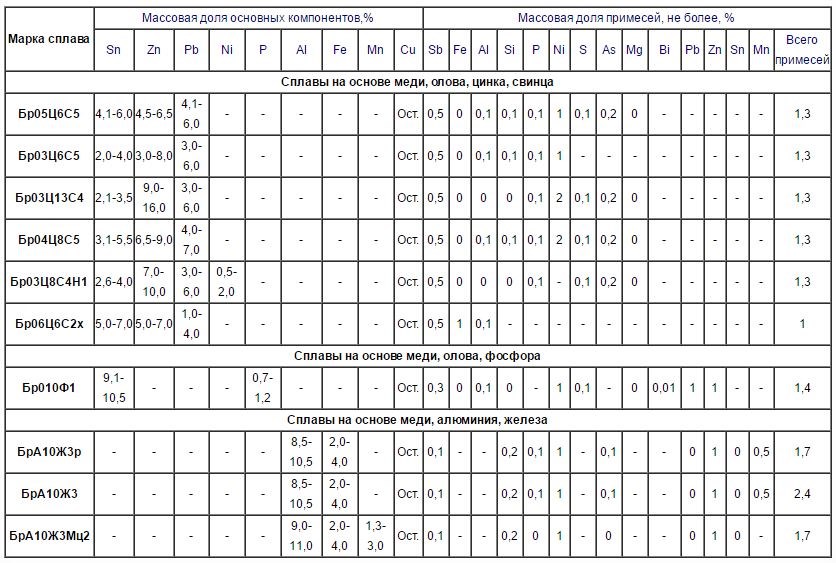

Химический состав различных марок бронзы (нажмите для увеличения)

Кроме разделения по химическому составу, существует классификация бронзовых сплавов по технологии обработки:

- деформируемые (используемые для производства изделий, которые обрабатывают методом пластической деформации);

- литейные (изделия из них производят методом литья).

Современная промышленность выпускает множество марок бронзы, отличающихся своим химическим составом и, соответственно, характеристиками и областью применения. Многие опытные мастера даже по цвету бронзы могут определить, к какому типу она относится. Однако далеко не все это умеют. Самым верным и наиболее простым способом получения информации о том, что содержится в составе бронзы определенной марки и к какому типу она относится, является расшифровка маркировки, которая включает в себя как буквенные, так и цифровые обозначения.

Струны для гитары: слева из обычной оловянной бронзы (20% олова), справа из фосфорной (7,7% олова, 0,3% фосфора)

Все марки бронзовых сплавов, выпускаемые современными предприятиями в строгом соответствии с требованиями нормативных документов (ГОСТов), перечислены в специальных таблицах, из которых можно получить информацию не только о химическом составе сплава определенной марки, но и о сферах его применения и характеристиках. Впрочем, даже не пользуясь такими таблицами, можно определить тип сплава и его химический состав, если знать, по какому принципу формируется его обозначение.

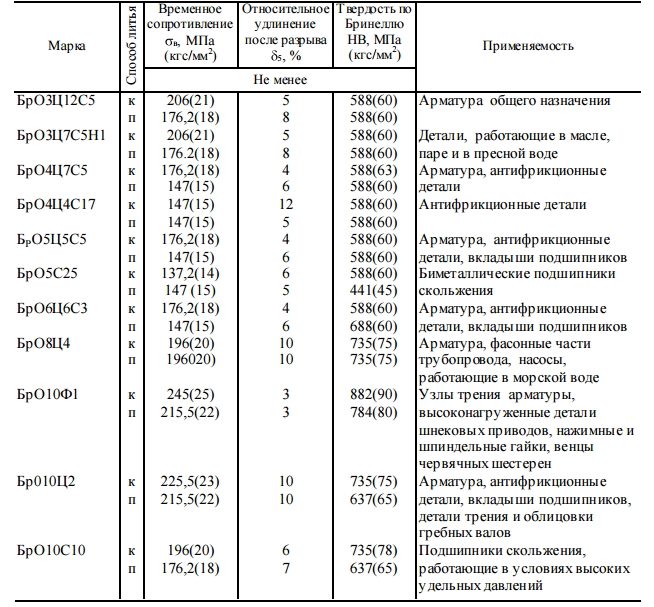

Механические свойства и применяемость оловянных бронз (к — литье в кокиль, п — литье в песчаную форму)

Понять, что перед вами бронза, сплав меди, можно по первым буквам «Бр», присутствующим в маркировке. После них ставятся буквы, по которым можно узнать, какие еще металлы, кроме меди, содержатся в химическом составе данного сплава. Нормативным документом установлены следующие правила обозначения химических элементов, присутствующих в составе бронзы:

Обозначение добавок в составе бронзы

Что характерно, в маркировке бронзы любой марки не указывается количество меди, содержащейся в ее химическом составе. При этом цифры, присутствующие в обозначении, указывают на количественное содержание (в целых долях процента) остальных элементов. Соответственно, количество меди, содержащееся в бронзе определенной марки, высчитывается как разность между 100% всего состава и количеством добавок. Например, в бронзе марки Бр АЖ 9-4, содержится 9% железа и 4% алюминия, остальные 87% составляет медь.

Бронзовый металлопрокат выпускается в виде ленты, проволоки, труб, втулок, плит и прутков

Количество чистой меди, содержащейся в составе бронзы, оказывает влияние не только на технологические и эксплуатационные характеристики изделия, но и на цвет его поверхности. Так, изделия из наиболее распространенных марок бронзовых сплавов, в составе которых около 85% меди, отличаются золотистым цветом. Если количество меди уменьшить до 50%, то на выходе может получиться белая бронза, очень похожая по своему цвету на серебро. При желании может быть получена серая и даже черная бронза – такого результата можно добиться, если уменьшить количество меди в составе сплава до 35% и ниже.

Многие старые бронзовые изделия, поверхность которых имеет практически черный цвет, приобрели его не из-за использования для их производства сплава определенного состава, а в результате воздействия времени и различных внешних факторов (пожары, длительное нахождение в сырой земле и др.). В древности просто не могло существовать технологий производства бронзы, состав которой дополняют редкоземельные металлы, придающие ей насыщенный черный цвет.

Марки и сферы их применения

Естественно, что различные химические элементы в состав любой бронзы вводят не бесцельно, а для того, чтобы улучшить ее свойства. Так, содержание в бронзе такого металла, как олово, оказывает влияние на ее пластичность. Чем больше в составе бронзы содержится данного металла, тем более твердым и, соответственно, более хрупким становится сплав. Однако самое значительное влияние на твердость и прочность бронзы оказывает такой химический элемент, как бериллий. Некоторые марки бронзовых сплавов, содержащие в своем химическом составе бериллий, превосходят по своим прочностным характеристикам высококачественные стали. Если подвергнуть бериллиевую бронзу процедуре закалки, то она наряду с высокой прочностью приобретает упругость, что позволяет изготавливать из такого материала пружины, рессоры и мембраны различного назначения.

Свойства и применение бериллиевых бронз (нажмите для увеличения)

Из бронзовых сплавов, химический состав которых обогащен алюминием, производят изделия, которые должны сочетать достаточно высокую прочность с исключительной коррозионной устойчивостью. Благодаря характеристикам бронзовых сплавов данного типа изделия из них успешно эксплуатируются в самых неблагоприятных условиях (повышенная влажность, воздействие морской воды и др.). В тех случаях, когда из бронзы необходимо изготовить изделие, которое в процессе эксплуатации будет подвергаться значительным ударным и фрикционным нагрузкам, лучше применять сплавы, содержащие в своем химическом составе свинец. Из такой бронзы, в частности, производятся подшипники, используемые в механизмах различного назначения.

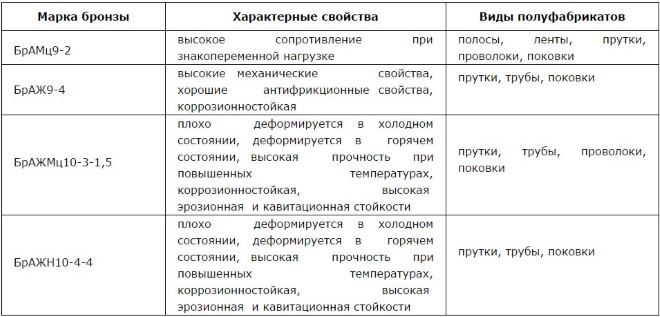

Особенности безоловянных алюминиевых бронз

Бронзы, в составе которых, кроме меди, содержится кремний и цинк, отличаются повышенной текучестью в расплавленном состоянии, поэтому их используют преимущественно для производства сложных деталей методом литья. Отличительным свойством бронз данного типа является и то, что при механическом воздействии на изделия, которые из них изготовлены, не образуются искры. Такое качество очень важно во многих случаях.

Относительно новым видом бронз, которые были разработаны в связи с развитием нефтедобывающей промышленности, являются медные сплавы, состав которых обогащен алюминием и никелем. Такие бронзы, отличающиеся исключительной коррозионной устойчивостью, часто называют морскими, потому что изделия из них способны сохранять все свои первоначальные характеристики даже после длительной эксплуатации в соленой морской воде. Получить такие сплавы, которые активно используются для производства элементов нефтяных платформ, устанавливаемых на морских и океанских шельфах, удалось благодаря развитию металлургической промышленности.

Большая часть марок бронзовых сплавов не магнитится, что дает возможность успешно использовать их для производства изделий электротехнического назначения.

Как производят бронзу

За длительный период существования технологии производства бронзы изменились только инструменты и оборудование, а суть осталась прежней. Как и в древние времена, в качестве сырья для получения этого медного сплава может выступать шихта или бронзовые отходы, а флюсом, который предотвращает слишком интенсивное окисление металла в расплавленном состоянии, является древесный уголь.

Эта установка центробежного литья позволят производить бронзовые заготовки весом до 50 кг

Сам процесс плавки, в результате которой и получают бронзу, выполняется в следующей последовательности.

- Тигель с исходным сырьем помещают в печь, предварительно разогретую до требуемой температуры.

- Чтобы металл после расплавления сильно не окислялся, к нему добавляют измельченный древесный уголь – флюс.

- После того как металл полностью расплавится и хорошо прогреется, в его состав вводят фосфористую медь, играющую роль кислотного катализатора.

- После некоторой выдержки в прогретом состоянии в расплавленный металл добавляют легирующие и связующие элементы (лигатуры), после чего полученный сплав тщательно перемешивается.

- Перед разливкой расплавленного металла в него вновь добавляют фосфористую медь, которая в данном случае необходима для снижения активности окислительных процессов.

На всех этапах производства надо очень тщательно следить за соблюдением правильного температурного режима в печи и самом сплаве. Следует также контролировать количество легирующих и связующих компонентов, добавляемых в расплавленный металл.

Естественное и искусственное патинирование

Многие наверняка задавались вопросом о том, почему старые бронзовые изделия выглядят не как обычная, а как зелено-белая бронза. Такой цвет появляется из-за образования пленки, которая называется патина. Фактором, который влияет на процесс образования такой пленки и интенсивность его протекания, является взаимодействие поверхности бронзового изделия с окружающим воздухом и содержащимися в нем компонентами (выхлопные газы, дым, водные пары и др.).

Патина, которая может быть оксидного или карбонатного происхождения, представляет собой защитную пленку. Ее наличие делает вид изделия более благородным (достаточно взглянуть на фото старых бронзовых предметов, чтобы понять это).

Сахарница из патинированной бронзы

На сегодняшний день разработаны технологии, которые позволяют не только снимать с поверхности бронзового изделия слой патины, но и выполнять искусственное патинирование, чтобы придать бронзовому предмету некоторую винтажность. Выполняют такое патинирование с помощью препаратов, содержащих в своем составе серу. После их нанесения на поверхность изделия его нагревают до определенной температуры.

Кроме искусственной патины, поверхность бронзовых изделий может покрываться слоем лака, позолоты, хрома или никеля.

Само название произошло от итальянского «bronzo». Впервые сплав начали использовать еще в 35-33 веке до н.э. (точные даты не установлены), когда начался бронзовый век, пришедший на смену медному. Благодаря улучшению обработки меди и олово удалось получить достаточно прочный и красивый сплав, который продержался почти до 11 века до н.э. Ее использовали для производства наконечников стрел и копий, кинжалов, ножей, мечей и другого холодного оружия, для производства деталей мебели, зеркал, посуды, ваз, кувшинов, украшений, статуй и монет.

В Средние века бронзу применяли для изготовления церковных колоколов и пушек, последние изготовлялись из специальной пушечной бронзы до XIX века.

Физические свойства