ВЕРХОВНЫЙ СОВЕТ РСФСР

ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ

от 22 ноября 1991 г. N 1920-I

О ДЕКЛАРАЦИИ ПРАВ И СВОБОД ЧЕЛОВЕКА И ГРАЖДАНИНА

Рассмотрев представленный Президентом РСФСР проект Декларации прав и свобод человека и гражданина, Верховный Совет РСФСР постановляет:

1. Принять Декларацию прав и свобод человека и гражданина.

2. Комитету Верховного Совета РСФСР по законодательству, Комитету Верховного Совета РСФСР по правам человека, Комитету Верховного Совета РСФСР по вопросам законности, правопорядка и борьбы с преступностью подготовить предложения по приведению законодательства РСФСР в соответствие с положениями настоящей Декларации и внести их на рассмотрение Верховного Совета РСФСР.

3. Президиуму Верховного Совета РСФСР:

включить намеченные к разработке законы в план законопроектных работ;

поручить соответствующим комиссиям палат и комитетам Верховного Совета РСФСР подготовку указанных законопроектов.

Председатель

Верховного Совета РСФСР

Р.И.ХАСБУЛАТОВ

Принята

Верховным Советом РСФСР

22 ноября 1991 года

ДЕКЛАРАЦИЯ

ПРАВ И СВОБОД ЧЕЛОВЕКА И ГРАЖДАНИНА

Утверждая права и свободы человека, его честь и достоинство как высшую ценность общества и государства, отмечая необходимость приведения законодательства РСФСР в соответствие с общепризнанными международным сообществом стандартами прав и свобод человека, Верховный Совет РСФСР принимает настоящую Декларацию.

Статья 1

(1) Права и свободы человека принадлежат ему от рождения.

(2) Общепризнанные международные нормы, относящиеся к правам человека, имеют преимущество перед законами РСФСР и непосредственно порождают права и обязанности граждан РСФСР.

Статья 2

(1) Перечень прав и свобод, закрепленных настоящей Декларацией, не является исчерпывающим и не умаляет других прав и свобод человека и гражданина.

(2) Права и свободы человека и гражданина могут быть ограничены законом только в той мере, в какой это необходимо в целях защиты конституционного строя, нравственности, здоровья, законных прав и интересов других людей в демократическом обществе.

Статья 3

(1) Все равны перед законом и судом.

(2) Равенство прав и свобод гарантируется государством независимо от расы, национальности, языка, социального происхождения, имущественного и должностного положения, места жительства, отношения к религии, убеждений, принадлежности к общественным объединениям, а также других обстоятельств.

(3) Мужчина и женщина имеют равные права и свободы.

(4) Лица, виновные в нарушении равноправия граждан, привлекаются к ответственности на основании закона.

Статья 4

(1) Осуществление человеком своих прав и свобод не должно нарушать права и свободы других лиц.

(2) Запрещается использование прав и свобод для насильственного изменения конституционного строя, разжигания расовой, национальной, классовой, религиозной ненависти, для пропаганды насилия и войны.

Статья 5

(1) Каждый имеет право на приобретение и прекращение гражданства в соответствии с законом РСФСР.

(2) Гражданин РСФСР не может быть лишен гражданства Российской Федерации или выслан за ее пределы.

(3) Гражданин РСФСР не может быть выдан другому государству иначе как на основании закона или международного договора РСФСР или СССР.

(4) Российская Федерация гарантирует своим гражданам защиту и покровительство за ее пределами.

Статья 6

Лица, не являющиеся гражданами РСФСР и законно находящиеся на ее территории, пользуются правами и свободами, а также несут обязанности граждан РСФСР, за изъятиями, установленными Конституцией, законами и международными договорами РСФСР или СССР. Лицо не может быть лишено почетного гражданства либо предоставленного политического убежища на территории РСФСР без согласия Верховного Совета РСФСР.

Статья 7

Каждый имеет право на жизнь. Никто не может быть произвольно лишен жизни. Государство стремится к полной отмене смертной казни. Смертная казнь впредь до ее отмены может применяться в качестве исключительной меры наказания за особо тяжкие преступления только по приговору суда с участием присяжных.

Статья 8

(1) Каждый имеет право на свободу и личную неприкосновенность.

(2) Задержание может быть обжаловано в судебном порядке.

(3) Заключение под стражу и лишение свободы допускаются исключительно на основании судебного решения в порядке, предусмотренном законом.

(4) Никто не может быть подвергнут пыткам, насилию, другому жестокому или унижающему человеческое достоинство обращению или наказанию. Никто не может быть без его добровольного согласия подвергнут медицинским, научным или иным опытам.

Статья 9

(1) Каждый имеет право на неприкосновенность его частной жизни, на тайну переписки, телефонных переговоров, телеграфных и иных сообщений. Ограничение этого права допускается только в соответствии с законом на основании судебного решения.

(2) Каждый имеет право на уважение и защиту его чести и достоинства.

(3) Сбор, хранение, использование и распространение информации о частной жизни лица без его согласия не допускаются, за исключением случаев, указанных в законе.

Статья 10

(1) Каждый имеет право на жилище. Никто не может быть произвольно лишен жилища.

(2) Государство поощряет жилищное строительство, содействует реализации права на жилище.

(3) Жилье малоимущим гражданам предоставляется бесплатно или на льготных условиях из государственных и муниципальных жилищных фондов.

Статья 11

(1) Жилище неприкосновенно. Никто не имеет права проникать в жилище против воли проживающих в нем лиц.

(2) Обыск и иные действия, совершаемые с проникновением в жилище, допускаются на основании судебного решения. В случаях, не терпящих отлагательств, возможен иной, установленный законом порядок, предусматривающий обязательную последующую проверку судом законности этих действий.

Статья 12

(1) Каждый имеет право на свободу передвижения, выбор места пребывания и жительства в пределах Российской Федерации.

(2) Гражданин РСФСР имеет право свободно выезжать за ее пределы и беспрепятственно возвращаться.

(3) Ограничение этих прав допускается только на основании закона.

Статья 13

(1) Каждый имеет право на свободу мысли, слова, а также на беспрепятственное выражение своих мнений и убеждений. Никто не может быть принужден к выражению своих мнений и убеждений.

(2) Каждый имеет право искать, получать и свободно распространять информацию. Ограничения этого права могут устанавливаться законом только в целях охраны личной, семейной, профессиональной, коммерческой и государственной тайны, а также нравственности. Перечень сведений, составляющих государственную тайну, устанавливается законом.

Статья 14

Каждому гарантируется свобода совести, вероисповедания, религиозной или атеистической деятельности. Каждый вправе свободно исповедовать любую религию или не исповедовать никакой, выбирать, иметь и распространять религиозные либо атеистические убеждения и действовать в соответствии с ними при условии соблюдения закона.

Статья 15

Каждый гражданин РСФСР, убеждениям которого противоречит несение военной службы, имеет право на ее замену выполнением альтернативных гражданских обязанностей в порядке, установленном законом.

Статья 16

(1) Каждый вправе свободно определять свою национальную принадлежность. Никто не должен быть принужден к определению и указанию его национальной принадлежности.

(2) Каждый имеет право на пользование родным языком, включая обучение и воспитание на родном языке.

(3) Оскорбление национального достоинства человека преследуется по закону.

Статья 17

Граждане РСФСР имеют право участвовать в управлении делами общества и государства как непосредственно, так и через своих представителей, свободно избираемых на основе всеобщего равного избирательного права при тайном голосовании.

Статья 18

Граждане РСФСР имеют равное право доступа к любым должностям в государственных органах в соответствии со своей профессиональной подготовкой и без какой-либо дискриминации. Требования, предъявляемые к кандидату на должность государственного служащего, обуславливаются исключительно характером должностных обязанностей.

Статья 19

Граждане РСФСР вправе собираться мирно и без оружия, проводить митинги, уличные шествия, демонстрации и пикетирование при условии предварительного уведомления властей.

Статья 20

Граждане РСФСР имеют право на объединение. Ограничение этого права может быть установлено только решением суда на основании закона.

Статья 21

Граждане РСФСР имеют право направлять личные и коллективные обращения в государственные органы и должностным лицам, которые в пределах своей компетенции обязаны рассмотреть эти обращения, принять по ним решения и дать мотивированный ответ в установленный законом срок.

Статья 22

(1) Каждый имеет право быть собственником, то есть имеет право владеть, пользоваться и распоряжаться своим имуществом и другими объектами собственности как индивидуально, так и совместно с другими лицами. Право наследования гарантируется законом.

(2) Каждый имеет право на предпринимательскую деятельность, не запрещенную законом.

Статья 23

(1) Каждый имеет право на труд, который он свободно выбирает или на который свободно соглашается, а также право распоряжаться своими способностями к труду и выбирать профессию и род занятий.

(2) Каждый имеет право на условия труда, отвечающие требованиям безопасности и гигиены, на равное вознаграждение за равный труд без какой бы то ни было дискриминации и не ниже установленного законом минимального размера.

(3) Каждый имеет право на защиту от безработицы.

(4) Принудительный труд запрещен.

Статья 24

(1) Каждый работник имеет право на отдых.

(2) Работающим по найму гарантируются установленные законом продолжительность рабочего времени, еженедельные выходные дни, праздничные дни, оплачиваемый ежегодный отпуск, сокращенный рабочий день для ряда профессий и работ.

Статья 25

(1) Каждый имеет право на квалифицированную медицинскую помощь в государственной системе здравоохранения. Государство принимает меры, направленные на развитие всех форм оказания медицинских услуг, включая бесплатное и платное медицинское обслуживание, а также медицинское страхование; поощряет деятельность, способствующую экологическому благополучию, укреплению здоровья каждого, развитию физической культуры и спорта.

(2) Сокрытие государственными должностными лицами фактов и обстоятельств, создающих угрозу жизни и здоровью людей, преследуется по закону.

Статья 26

(1) Каждый имеет право на социальное обеспечение по возрасту, в случае утраты трудоспособности, потери кормильца и в иных, установленных законом случаях.

(2) Пенсии, пособия и другие виды социальной помощи должны обеспечивать уровень жизни не ниже установленного законом прожиточного минимума.

(3) Государство развивает систему социального страхования и обеспечения.

(4) Поощряется создание общественных фондов социального обеспечения и благотворительность.

Статья 27

(1) Каждый имеет право на образование.

(2) Гарантируется общедоступность и бесплатность образования в пределах государственного образовательного стандарта. Основное образование обязательно.

Статья 28

Государство обеспечивает защиту материнства и младенчества, права детей, инвалидов, умственно отсталых лиц, а также граждан, отбывших наказание в местах лишения свободы и нуждающихся в социальной поддержке.

Статья 29

(1) Свобода художественного, научного и технического творчества, исследований и преподавания, а также интеллектуальная собственность охраняются законом.

(2) Признается право каждого на участие в культурной жизни и пользование учреждениями культуры.

Статья 30

Каждый вправе защищать свои права, свободы и законные интересы всеми способами, не противоречащими закону.

Статья 31

Государственные органы, учреждения и должностные лица обязаны обеспечить каждому возможность ознакомления с документами и материалами, непосредственно затрагивающими его права и свободы, если иное не предусмотрено законом.

Статья 32

Каждому гарантируется судебная защита его прав и свобод. Решения и деяния должностных лиц, государственных органов и общественных организаций, повлекшие за собой нарушение закона или превышение полномочий, а также ущемляющие права граждан, могут быть обжалованы в суд.

Статья 33

Права жертв преступлений и злоупотреблений властью охраняются законом. Государство обеспечивает им доступ к правосудию и скорейшую компенсацию за причиненный ущерб.

Статья 34

(1) Каждый обвиняемый в уголовном преступлении считается невиновным, пока его виновность не будет доказана в предусмотренном законом порядке и установлена вступившим в законную силу приговором компетентного, независимого и беспристрастного суда. Обвиняемый не обязан доказывать свою невиновность. Неустранимые сомнения в виновности лица толкуются в пользу обвиняемого.

(2) Каждый осужденный за уголовное преступление имеет право на пересмотр приговора вышестоящей судебной инстанцией в порядке, установленном законом, а также право просить о помиловании или смягчении наказания.

(3) Никто не должен дважды нести уголовную или иную ответственность за одно и то же правонарушение.

(4) Признаются не имеющими юридической силы доказательства, полученные с нарушением закона.

Статья 35

(1) Закон, устанавливающий или отягчающий ответственность лица, обратной силы не имеет. Никто не может нести ответственность за действия, которые в момент их совершения не признавались правонарушением. Если после совершения правонарушения ответственность за него устранена или смягчена, применяется новый закон.

(2) Закон, предусматривающий наказание граждан или ограничение их прав, вступает в силу только после его опубликования в официальном порядке.

Статья 36

Никто не обязан свидетельствовать против себя самого, своего супруга или близких родственников, круг которых определяется законом. Законом могут устанавливаться и иные случаи освобождения от обязанности давать показания.

Статья 37

(1) Каждому гарантируется право на пользование квалифицированной юридической помощью. В случаях, предусмотренных законом, эта помощь оказывается бесплатно.

(2) Каждое задержанное, заключенное под стражу или обвиняемое в совершении преступления лицо имеет право пользоваться помощью адвоката (защитника) с момента соответственно задержания, заключения под стражу или предъявления обвинения.

Статья 38

Каждый имеет право на возмещение государством всякого вреда, причиненного незаконными действиями государственных органов и их должностных лиц при исполнении служебных обязанностей.

Статья 39

Временное ограничение прав и свобод человека и гражданина допускается в случае введения чрезвычайного положения на основаниях и в пределах, устанавливаемых законом РСФСР.

Статья 40

(1) Парламентский контроль за соблюдением прав и свобод человека и гражданина в Российской Федерации возлагается на Парламентского уполномоченного по правам человека.

(2) Парламентский уполномоченный по правам человека назначается Верховным Советом РСФСР сроком на 5 лет, подотчетен ему и обладает той же неприкосновенностью, что и народный депутат РСФСР.

(3) Полномочия Парламентского уполномоченного по правам человека и порядок их осуществления устанавливаются законом.

\

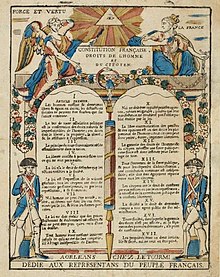

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789), set by France’s National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolution.[1] Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a major impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.[2]

The Declaration was originally drafted by the Marquis de Lafayette, but the majority of the final draft came from the Abbé Sieyès.[3] Influenced by the doctrine of natural right, the rights of man are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included in the beginning of the constitutions of both the Fourth French Republic (1946) and Fifth Republic (1958), and is considered valid as constitutional law.

History[edit]

The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment.[4]

The principal drafts were prepared by Lafayette in consultation with his close friend Thomas Jefferson.[5][6] In August 1789, the Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[7][8]

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives on the basis of a 24 article draft proposed by the sixth bureau[clarify],[9][10] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.[11]

Philosophical and theoretical context[edit]

The concepts in the Declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of the Enlightenment, such as individualism, the social contract as theorized by the Genevan philosopher Rousseau, and the separation of powers espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence which preceded it (4 July 1776).

The declaration defines a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, «Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.»[12] They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.[13]

At the time it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.[14]

Substance[edit]

The Declaration is introduced by a preamble describing the fundamental characteristics of the rights which are qualified as being «natural, unalienable and sacred» and consisting of «simple and incontestable principles» on which citizens could base their demands. In the second article, «the natural and imprescriptible rights of man» are defined as «liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression». It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end to feudalism and to exemptions from taxation, freedom and equal rights for all «Men», and access to public office based on talent. The monarchy was restricted, and all citizens were to have the right to take part in the legislative process. Freedom of speech and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests outlawed.[15]

The Declaration also asserted the principles of popular sovereignty, in contrast to the divine right of kings that characterized the French monarchy, and social equality among citizens, «All the citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents,» eliminating the special rights of the nobility and clergy.[16]

Articles[edit]

Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III – The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disquieted for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Active and passive citizenship[edit]

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens. Active citizenship was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants.[17] This meant that at the time of the Declaration only male property owners held these rights.[18] The deputies in the National Assembly believed that only those who held tangible interests in the nation could make informed political decisions.[19] This distinction directly affects articles 6, 12, 14, and 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen as each of these rights is related to the right to vote and to participate actively in the government. With the decree of 29 October 1789, the term active citizen became embedded in French politics.[20]

The concept of passive citizens was created to encompass those populations that had been excluded from political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Because of the requirements set down for active citizens, the vote was granted to approximately 4.3 million Frenchmen[20] out of a population of around 29 million.[citation needed] These omitted groups included women, slaves, children, and foreigners. As these measures were voted upon by the General Assembly, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the new French Republic (1792–1804).[19] This legislation, passed in 1789, was amended by the creators of the Constitution of the Year III in order to eliminate the label of active citizen.[21] The power to vote was then, however, to be granted solely to substantial property owners.[21]

Tensions arose between active and passive citizens throughout the Revolution. This happened when passive citizens started to call for more rights, or when they openly refused to listen to the ideals set forth by active citizens. This cartoon clearly demonstrates the difference that existed between the active and passive citizens along with the tensions associated with such differences.[22] In the cartoon, an active citizen is holding a spade and a passive citizen (on the right) says «Take care that my patience does not escape me».

Women, in particular, were strong passive citizens who played a significant role in the Revolution. Olympe de Gouges penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality.[23] By supporting the ideals of the French Revolution and wishing to expand them to women, she represented herself as a revolutionary citizen. Madame Roland also established herself as an influential figure throughout the Revolution. She saw women of the French Revolution as holding three roles; «inciting revolutionary action, formulating policy, and informing others of revolutionary events.»[24] By working with men, as opposed to working apart from men, she may have been able to further the fight of revolutionary women. As players in the French Revolution, women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political power.[25]

Women’s rights[edit]

The Declaration recognized many rights as belonging to citizens (who could only be male). This was despite the fact that after The March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, women presented the Women’s Petition to the National Assembly in which they proposed a decree giving women equal rights.[26] In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d’Aelders unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.[27] Condorcet declared that «he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth abjured his own».[28] The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women’s rights and this prompted Olympe de Gouges to publish the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in September 1791.[29]

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen is modeled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality. It states that:

This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights, they have lost in society.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as «almost a parody… of the original document». The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that «Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.» The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied: «Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility».

De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights, declaring «Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker’s rostrum».[30]

Slavery[edit]

The declaration did not revoke the institution of slavery, as lobbied for by Jacques-Pierre Brissot’s Les Amis des Noirs and defended by the group of colonial planters called the Club Massiac because they met at the Hôtel Massiac.[31] Despite the lack of explicit mention of slavery in the Declaration, slave uprisings in Saint-Domingue in the Haitian Revolution were inspired by it, as discussed in C. L. R. James’ history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins.[32] In Louisiana, the organizers of the Pointe Coupée Slave Conspiracy of 1795 also drew information from the declaration.[33]

Deplorable conditions for the thousands of slaves in Saint-Domingue, the most profitable slave colony in the world, led to the uprisings which would be known as the first successful slave revolt in the New World. Free persons of color were part of the first wave of revolt, but later former slaves took control. In 1794 the Convention dominated by the Jacobins abolished slavery, including in the colonies of Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe. However, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802 and attempted to regain control of Saint-Domingue by sending in thousands of troops. After suffering the losses of two-thirds of the men, many to yellow fever, the French withdrew from Saint-Domingue in 1803. Napoleon gave up on North America and agreed to the Louisiana Purchase by the United States. In 1804, the leaders of Saint-Domingue declared it as an independent state, the Republic of Haiti, the second republic of the New World. Napoleon abolished the slave trade in 1815.[34] Slavery in France was finally abolished in 1848.

Homosexuality[edit]

The wide amount of personal freedom given to citizens by the document created a situation where homosexuality was decriminalized by the French Penal Code of 1791, which covered felonies; the law simply failed to mention sodomy as a crime, and thus no one could be prosecuted for it.[35] The 1791 Code of Municipal Police did provide misdemeanor penalties for «gross public indecency,» which the police could use to punish anyone having sex in public places or otherwise violating social norms. This approach to punishing homosexual conduct was reiterated in the French Penal Code of 1810.

See also[edit]

- Bill of rights

- Human rights in France

- Rights of Man

- Universality

Other early declarations of rights[edit]

- The decreta of León[36][37] (Kingdom of León (Modern Spain) 1188)

- Magna Carta (England, 1215)

- Statute of Kalisz (Poland, 1264)

- Henrician Articles and Pacta conventa (Poland, 1573)

- Petition of Right (England, 1628)

- Bill of Rights (England, 1689)

- Claim of Right (Scotland, 1689)

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Bill of Rights (United States, 1789)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of Franchimont (modern-day Belgium, 16 September 1789)

- «Belgian» Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (exiled Belgian and Liégeois revolutionaries in Paris, 23 April 1792)

- Proclamation of Połaniec (Poland, 7 May 1794)

- «Batavian» Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (Batavian Republic, The Hague, 31 January 1795)

Citations[edit]

- ^ The French title can be also translated in the modern era as «Declaration of Human and Civic Rights».

- ^ Kopstein Kopstein (2000). Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge UP. p. 72. ISBN 9780521633567.

- ^ Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood. p. 190. ISBN 9780313049514.

- ^ Lefebvre, Georges (2005). The Coming of the French Revolution. Princeton UP. p. 212. ISBN 0691121885.

- ^ George Athan Billias, ed. (2009). American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776–1989: A Global Perspective. NYU Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780814791394.

- ^ Susan Dunn, Sister Revolutions: French Lightning, American Light (1999) pp. 143–45

- ^ Fremont-Barnes 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Keith Baker, «The Idea of a Declaration of Rights» in Dale Van Kley, ed. The French Idea of Freedom: The Old Regime and the Declaration of Rights of 1789 (1997) pp. 154–96.

- ^ The original draft is an annex to the 12 August report (Archives parlementaires, 1,e série, tome VIII, débats du 12 août 1789, p. 431).

- ^ Archives parlementaires, 1e série, tome VIII, débats du 19 août 1789, p. 459.

- ^ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 159 vol 1. ISBN 9780313334450.

- ^ First Article, Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- ^ Merryman, John Henry; Rogelierdomo (2007). The civil law tradition: an introduction to the legal system of Europe and Latin America. Stanford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0804755696.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0812218541.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2008). Western Civilization: 1300 to 1815. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-495-50289-0.

- ^ von Guttner, Darius (2015). The French Revolution. Nelson Cengage. pp. 85–88.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Thouret ‘Report on the Basis of Political Eligibility’ (29 September 1789) · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOUTION». revolution.chnm.org. 29 September 1789. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Censer and Hunt 2001, p. 55.

- ^ a b Popkin 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 124.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 420.

- ^ «Active Citizen/Passive Citizen · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOUTION». revolution.chnm.org. 1791. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ De Gouges, «Declaration of the Rights of Women», 1791.

- ^ Dalton 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Levy and Applewhite 2002, pp. 319–20, 324.

- ^ «Women’s Petition to the National Assembly». Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat; Susan Sniader Lanser; David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-55111-255-8.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ The club of reactionary colonial proprietors meeting since July 1789 were opposed to representation in the Assemblée of France’s overseas dominions, for fear «that this would expose delicate colonial issues to the hazards of debate in the Assembly», as Robin Blackburn expressed it (Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 [1988:174f]); see also the speech of Jean-Baptiste Belley

- ^ Cf. Heinrich August Winkler (2012), Geschichte des Westens. Von den Anfängen in der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, Third Edition, Munich (Germany), p. 386

- ^ Rasmussen, Daniel (2011). American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt. Harper Collins. p. 89.

- ^ «Napoleon’s Decree Abolishing the Slave Trade 29 March 1815». The Napoleon Series. September 2000. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Merrick, Jeffrey; Ragan, Brant T. Jr. (1996). Homosexuality in Modern France. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 82 ff. ISBN 0195357671. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ «The Decreta of León of 1188 – The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system». www.unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ «Versión española de los Decreta de León de 1188» (PDF). www.mecd.gob.es. Spanish Mimisterio de Educació, Cultura y Deporte. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

General references[edit]

- Jack Censer and Lynn Hunt, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

- Susan Dalton, «Gender and the Shifting Ground of Revolutionary Politics: The Case of Madame Roland», Canadian Journal of History, 36, no. 2 (2001): 259–83. doi:10.3138/cjh.36.2.259. PMID 18711850.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Darline Levy and Harriet Applewhite, A Political Revolution for Women? The Case of Paris, in The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. 5th ed. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. Co., 2002. 317–46.

- Jeremy Popkin, A History of Modern France, Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, 2006.

- «Active Citizen/Passive Citizen», Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution (accessed 30 October 2011). Project History.

Further reading[edit]

- Gérard Conac, Marc Debene, Gérard Teboul, eds, La Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789; histoire, analyse et commentaires (in French), Economica, Paris, 1993, ISBN 978-2-7178-2483-4.

- McLean, Iain. «Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen» in The Future of Liberal Democracy: Thomas Jefferson and the Contemporary World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

External links[edit]

- «Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen de 1789». Conseil constitutionnel (in French). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- «Declaration of human and civic rights of 26 August 1789» (PDF). Conseil constitutionnel. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789), set by France’s National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolution.[1] Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a major impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.[2]

The Declaration was originally drafted by the Marquis de Lafayette, but the majority of the final draft came from the Abbé Sieyès.[3] Influenced by the doctrine of natural right, the rights of man are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included in the beginning of the constitutions of both the Fourth French Republic (1946) and Fifth Republic (1958), and is considered valid as constitutional law.

History[edit]

The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment.[4]

The principal drafts were prepared by Lafayette in consultation with his close friend Thomas Jefferson.[5][6] In August 1789, the Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[7][8]

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives on the basis of a 24 article draft proposed by the sixth bureau[clarify],[9][10] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.[11]

Philosophical and theoretical context[edit]

The concepts in the Declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of the Enlightenment, such as individualism, the social contract as theorized by the Genevan philosopher Rousseau, and the separation of powers espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence which preceded it (4 July 1776).

The declaration defines a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, «Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.»[12] They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.[13]

At the time it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.[14]

Substance[edit]

The Declaration is introduced by a preamble describing the fundamental characteristics of the rights which are qualified as being «natural, unalienable and sacred» and consisting of «simple and incontestable principles» on which citizens could base their demands. In the second article, «the natural and imprescriptible rights of man» are defined as «liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression». It called for the destruction of aristocratic privileges by proclaiming an end to feudalism and to exemptions from taxation, freedom and equal rights for all «Men», and access to public office based on talent. The monarchy was restricted, and all citizens were to have the right to take part in the legislative process. Freedom of speech and press were declared, and arbitrary arrests outlawed.[15]

The Declaration also asserted the principles of popular sovereignty, in contrast to the divine right of kings that characterized the French monarchy, and social equality among citizens, «All the citizens, being equal in the eyes of the law, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents,» eliminating the special rights of the nobility and clergy.[16]

Articles[edit]

Article I – Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

Article II – The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

Article III – The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation. No body, no individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.

Article IV – Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the fruition of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

Article V – The law has the right to forbid only actions harmful to society. Anything which is not forbidden by the law cannot be impeded, and no one can be constrained to do what it does not order.

Article VI – The law is the expression of the general will. All the citizens have the right of contributing personally or through their representatives to its formation. It must be the same for all, either that it protects, or that it punishes. All the citizens, being equal in its eyes, are equally admissible to all public dignities, places, and employments, according to their capacity and without distinction other than that of their virtues and of their talents.

Article VII – No man can be accused, arrested nor detained but in the cases determined by the law, and according to the forms which it has prescribed. Those who solicit, dispatch, carry out or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders, must be punished; but any citizen called or seized under the terms of the law must obey at once; he renders himself culpable by resistance.

Article VIII – The law should establish only penalties that are strictly and evidently necessary, and no one can be punished but under a law established and promulgated before the offense and legally applied.

Article IX – Any man being presumed innocent until he is declared culpable if it is judged indispensable to arrest him, any rigor which would not be necessary for the securing of his person must be severely reprimanded by the law.

Article X – No one may be disquieted for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their manifestation does not trouble the public order established by the law.

Article XI – The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

Article XII – The guarantee of the rights of man and of the citizen necessitates a public force: this force is thus instituted for the advantage of all and not for the particular utility of those in whom it is trusted.

Article XIII – For the maintenance of the public force and for the expenditures of administration, a common contribution is indispensable; it must be equally distributed to all the citizens, according to their ability to pay.

Article XIV – Each citizen has the right to ascertain, by himself or through his representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to know the uses to which it is put, and of determining the proportion, basis, collection, and duration.

Article XV – The society has the right of requesting an account from any public agent of its administration.

Article XVI – Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not assured, nor the separation of powers determined, has no Constitution.

Article XVII – Property being an inviolable and sacred right, no one can be deprived of private usage, if it is not when the public necessity, legally noted, evidently requires it, and under the condition of a just and prior indemnity.

Active and passive citizenship[edit]

While the French Revolution provided rights to a larger portion of the population, there remained a distinction between those who obtained the political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and those who did not. Those who were deemed to hold these political rights were called active citizens. Active citizenship was granted to men who were French, at least 25 years old, paid taxes equal to three days work, and could not be defined as servants.[17] This meant that at the time of the Declaration only male property owners held these rights.[18] The deputies in the National Assembly believed that only those who held tangible interests in the nation could make informed political decisions.[19] This distinction directly affects articles 6, 12, 14, and 15 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen as each of these rights is related to the right to vote and to participate actively in the government. With the decree of 29 October 1789, the term active citizen became embedded in French politics.[20]

The concept of passive citizens was created to encompass those populations that had been excluded from political rights in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Because of the requirements set down for active citizens, the vote was granted to approximately 4.3 million Frenchmen[20] out of a population of around 29 million.[citation needed] These omitted groups included women, slaves, children, and foreigners. As these measures were voted upon by the General Assembly, they limited the rights of certain groups of citizens while implementing the democratic process of the new French Republic (1792–1804).[19] This legislation, passed in 1789, was amended by the creators of the Constitution of the Year III in order to eliminate the label of active citizen.[21] The power to vote was then, however, to be granted solely to substantial property owners.[21]

Tensions arose between active and passive citizens throughout the Revolution. This happened when passive citizens started to call for more rights, or when they openly refused to listen to the ideals set forth by active citizens. This cartoon clearly demonstrates the difference that existed between the active and passive citizens along with the tensions associated with such differences.[22] In the cartoon, an active citizen is holding a spade and a passive citizen (on the right) says «Take care that my patience does not escape me».

Women, in particular, were strong passive citizens who played a significant role in the Revolution. Olympe de Gouges penned her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in 1791 and drew attention to the need for gender equality.[23] By supporting the ideals of the French Revolution and wishing to expand them to women, she represented herself as a revolutionary citizen. Madame Roland also established herself as an influential figure throughout the Revolution. She saw women of the French Revolution as holding three roles; «inciting revolutionary action, formulating policy, and informing others of revolutionary events.»[24] By working with men, as opposed to working apart from men, she may have been able to further the fight of revolutionary women. As players in the French Revolution, women occupied a significant role in the civic sphere by forming social movements and participating in popular clubs, allowing them societal influence, despite their lack of direct political power.[25]

Women’s rights[edit]

The Declaration recognized many rights as belonging to citizens (who could only be male). This was despite the fact that after The March on Versailles on 5 October 1789, women presented the Women’s Petition to the National Assembly in which they proposed a decree giving women equal rights.[26] In 1790, Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d’Aelders unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.[27] Condorcet declared that «he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth abjured his own».[28] The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women’s rights and this prompted Olympe de Gouges to publish the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen in September 1791.[29]

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen is modeled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to equality. It states that:

This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights, they have lost in society.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as «almost a parody… of the original document». The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that «Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.» The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied: «Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility».

De Gouges also draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights, declaring «Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker’s rostrum».[30]

Slavery[edit]

The declaration did not revoke the institution of slavery, as lobbied for by Jacques-Pierre Brissot’s Les Amis des Noirs and defended by the group of colonial planters called the Club Massiac because they met at the Hôtel Massiac.[31] Despite the lack of explicit mention of slavery in the Declaration, slave uprisings in Saint-Domingue in the Haitian Revolution were inspired by it, as discussed in C. L. R. James’ history of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins.[32] In Louisiana, the organizers of the Pointe Coupée Slave Conspiracy of 1795 also drew information from the declaration.[33]

Deplorable conditions for the thousands of slaves in Saint-Domingue, the most profitable slave colony in the world, led to the uprisings which would be known as the first successful slave revolt in the New World. Free persons of color were part of the first wave of revolt, but later former slaves took control. In 1794 the Convention dominated by the Jacobins abolished slavery, including in the colonies of Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe. However, Napoleon reinstated it in 1802 and attempted to regain control of Saint-Domingue by sending in thousands of troops. After suffering the losses of two-thirds of the men, many to yellow fever, the French withdrew from Saint-Domingue in 1803. Napoleon gave up on North America and agreed to the Louisiana Purchase by the United States. In 1804, the leaders of Saint-Domingue declared it as an independent state, the Republic of Haiti, the second republic of the New World. Napoleon abolished the slave trade in 1815.[34] Slavery in France was finally abolished in 1848.

Homosexuality[edit]

The wide amount of personal freedom given to citizens by the document created a situation where homosexuality was decriminalized by the French Penal Code of 1791, which covered felonies; the law simply failed to mention sodomy as a crime, and thus no one could be prosecuted for it.[35] The 1791 Code of Municipal Police did provide misdemeanor penalties for «gross public indecency,» which the police could use to punish anyone having sex in public places or otherwise violating social norms. This approach to punishing homosexual conduct was reiterated in the French Penal Code of 1810.

See also[edit]

- Bill of rights

- Human rights in France

- Rights of Man

- Universality

Other early declarations of rights[edit]

- The decreta of León[36][37] (Kingdom of León (Modern Spain) 1188)

- Magna Carta (England, 1215)

- Statute of Kalisz (Poland, 1264)

- Henrician Articles and Pacta conventa (Poland, 1573)

- Petition of Right (England, 1628)

- Bill of Rights (England, 1689)

- Claim of Right (Scotland, 1689)

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights (United States, 1776)

- Bill of Rights (United States, 1789)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of Franchimont (modern-day Belgium, 16 September 1789)

- «Belgian» Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (exiled Belgian and Liégeois revolutionaries in Paris, 23 April 1792)

- Proclamation of Połaniec (Poland, 7 May 1794)

- «Batavian» Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (Batavian Republic, The Hague, 31 January 1795)

Citations[edit]

- ^ The French title can be also translated in the modern era as «Declaration of Human and Civic Rights».

- ^ Kopstein Kopstein (2000). Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge UP. p. 72. ISBN 9780521633567.

- ^ Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood. p. 190. ISBN 9780313049514.

- ^ Lefebvre, Georges (2005). The Coming of the French Revolution. Princeton UP. p. 212. ISBN 0691121885.

- ^ George Athan Billias, ed. (2009). American Constitutionalism Heard Round the World, 1776–1989: A Global Perspective. NYU Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780814791394.

- ^ Susan Dunn, Sister Revolutions: French Lightning, American Light (1999) pp. 143–45

- ^ Fremont-Barnes 2007, p. 190.

- ^ Keith Baker, «The Idea of a Declaration of Rights» in Dale Van Kley, ed. The French Idea of Freedom: The Old Regime and the Declaration of Rights of 1789 (1997) pp. 154–96.

- ^ The original draft is an annex to the 12 August report (Archives parlementaires, 1,e série, tome VIII, débats du 12 août 1789, p. 431).

- ^ Archives parlementaires, 1e série, tome VIII, débats du 19 août 1789, p. 459.

- ^ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 159 vol 1. ISBN 9780313334450.

- ^ First Article, Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- ^ Merryman, John Henry; Rogelierdomo (2007). The civil law tradition: an introduction to the legal system of Europe and Latin America. Stanford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0804755696.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights: visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0812218541.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2008). Western Civilization: 1300 to 1815. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 580. ISBN 978-0-495-50289-0.

- ^ von Guttner, Darius (2015). The French Revolution. Nelson Cengage. pp. 85–88.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Thouret ‘Report on the Basis of Political Eligibility’ (29 September 1789) · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOUTION». revolution.chnm.org. 29 September 1789. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Censer and Hunt 2001, p. 55.

- ^ a b Popkin 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 124.

- ^ a b Doyle 1989, p. 420.

- ^ «Active Citizen/Passive Citizen · LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOUTION». revolution.chnm.org. 1791. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ De Gouges, «Declaration of the Rights of Women», 1791.

- ^ Dalton 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Levy and Applewhite 2002, pp. 319–20, 324.

- ^ «Women’s Petition to the National Assembly». Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat; Susan Sniader Lanser; David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-55111-255-8.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-05585-7.

- ^ The club of reactionary colonial proprietors meeting since July 1789 were opposed to representation in the Assemblée of France’s overseas dominions, for fear «that this would expose delicate colonial issues to the hazards of debate in the Assembly», as Robin Blackburn expressed it (Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 [1988:174f]); see also the speech of Jean-Baptiste Belley

- ^ Cf. Heinrich August Winkler (2012), Geschichte des Westens. Von den Anfängen in der Antike bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, Third Edition, Munich (Germany), p. 386

- ^ Rasmussen, Daniel (2011). American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt. Harper Collins. p. 89.

- ^ «Napoleon’s Decree Abolishing the Slave Trade 29 March 1815». The Napoleon Series. September 2000. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Merrick, Jeffrey; Ragan, Brant T. Jr. (1996). Homosexuality in Modern France. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 82 ff. ISBN 0195357671. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ «The Decreta of León of 1188 – The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system». www.unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ «Versión española de los Decreta de León de 1188» (PDF). www.mecd.gob.es. Spanish Mimisterio de Educació, Cultura y Deporte. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

General references[edit]

- Jack Censer and Lynn Hunt, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

- Susan Dalton, «Gender and the Shifting Ground of Revolutionary Politics: The Case of Madame Roland», Canadian Journal of History, 36, no. 2 (2001): 259–83. doi:10.3138/cjh.36.2.259. PMID 18711850.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Darline Levy and Harriet Applewhite, A Political Revolution for Women? The Case of Paris, in The French Revolution: Conflicting Interpretations. 5th ed. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger Pub. Co., 2002. 317–46.

- Jeremy Popkin, A History of Modern France, Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education, 2006.

- «Active Citizen/Passive Citizen», Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution (accessed 30 October 2011). Project History.

Further reading[edit]

- Gérard Conac, Marc Debene, Gérard Teboul, eds, La Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen de 1789; histoire, analyse et commentaires (in French), Economica, Paris, 1993, ISBN 978-2-7178-2483-4.

- McLean, Iain. «Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen» in The Future of Liberal Democracy: Thomas Jefferson and the Contemporary World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004)

External links[edit]

- «Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen de 1789». Conseil constitutionnel (in French). Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- «Declaration of human and civic rights of 26 August 1789» (PDF). Conseil constitutionnel. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

Принята

Генеральной Ассамблеей ООН

10 декабря 1948 г.

ВСЕОБЩАЯ ДЕКЛАРАЦИЯ ПРАВ ЧЕЛОВЕКА

ПРЕАМБУЛА

Принимая во внимание, что признание достоинства, присущего всем членам человеческой семьи, и равных и неотъемлемых прав их является основой свободы, справедливости и всеобщего мира; и

принимая во внимание, что пренебрежение и презрение к правам человека привели к варварским актам, которые возмущают совесть человечества, и что создание такого мира, в котором люди будут иметь свободу слова и убеждений и будут свободны от страха и нужды, провозглашено как высокое стремление людей; и

принимая во внимание, что необходимо, чтобы права человека охранялись властью закона в целях обеспечения того, чтобы человек не был вынужден прибегать, в качестве последнего средства, к восстанию против тирании и угнетения; и

принимая во внимание, что необходимо содействовать развитию дружественных отношений между народами; и

принимая во внимание, что народы Объединенных Наций подтвердили в Уставе свою веру в основные права человека, в достоинство и ценность человеческой личности и в равноправие мужчин и женщин и решили содействовать социальному прогрессу и улучшению условий жизни при большей свободе; и

принимая во внимание, что государства-члены обязались содействовать, в сотрудничестве с Организацией Объединенных Наций, всеобщему уважению и соблюдению прав человека и основных свобод; и

принимая во внимание, что всеобщее понимание характера этих прав и свобод имеет огромное значение для полного выполнения этого обязательства,

Генеральная Ассамблея провозглашает настоящую Всеобщую декларацию прав человека в качестве задачи, к выполнению которой должны стремиться все народы и все государства с тем, чтобы каждый человек и каждый орган общества, постоянно имея в виду настоящую Декларацию, стремились путем просвещения и образования содействовать уважению этих прав и свобод и обеспечению, путем национальных и международных прогрессивных мероприятий, всеобщего и эффективного признания и осуществления их как среди народов государств — членов Организации, так и среди народов территорий, находящихся под их юрисдикцией.

Статья 1

Все люди рождаются свободными и равными в своем достоинстве и правах. Они наделены разумом и совестью и должны поступать в отношении друг друга в духе братства.

Статья 2

Каждый человек должен обладать всеми правами и всеми свободами, провозглашенными настоящей Декларацией, без какого бы то ни было различия, как-то: в отношении расы, цвета кожи, пола, языка, религии, политических или иных убеждений, национального или социального происхождения, имущественного, сословного или иного положения.

Кроме того, не должно проводиться никакого различия на основе политического, правового или международного статуса страны или территории, к которой человек принадлежит, независимо от того, является ли эта территория независимой, подопечной, несамоуправляющейся, или как-либо иначе ограниченной в своем суверенитете.

Статья 3

Каждый человек имеет право на жизнь, на свободу и на личную неприкосновенность.

Статья 4

Никто не должен содержаться в рабстве или подневольном состоянии; рабство и работорговля запрещаются во всех их видах.

Статья 5

Никто не должен подвергаться пыткам или жестоким, бесчеловечным или унижающим достоинство обращению и наказанию.

Статья 6

Каждый человек, где бы он ни находился, имеет право на признание его правосубъектности.

Статья 7

Все люди равны перед законом и имеют право, без всякого различия, на равную защиту закона. Все люди имеют право на равную защиту от какой бы то ни было дискриминации, нарушающей настоящую Декларацию, и от какого бы то ни было подстрекательства к такой дискриминации.

Статья 8

Каждый человек имеет право на эффективное восстановление в правах компетентными национальными судами в случае нарушения его основных прав, предоставленных ему конституцией или законом.

Статья 9

Никто не может быть подвергнут произвольному аресту, задержанию или изгнанию.

Статья 10

Каждый человек для определения его прав и обязанностей и для установления обоснованности предъявленного ему уголовного обвинения имеет право, на основе полного равенства, на то, чтобы его дело было рассмотрено гласно и с соблюдением всех требований справедливости независимым и беспристрастным судом.

Статья 11

1. Каждый человек, обвиняемый в совершении преступления, имеет право считаться невиновным до тех пор, пока его виновность не будет установлена законным порядком путем гласного судебного разбирательства, при котором ему обеспечиваются все возможности для защиты.

2. Никто не может быть осужден за преступление на основании совершения какого-либо деяния или за бездействие, которые во время их совершения не составляли преступления по национальным законам или по международному праву. Не может также налагаться наказание более тяжкое, нежели то, которое могло быть применено в то время, когда преступление было совершено.

Статья 12

Никто не может подвергаться произвольному вмешательству в его личную и семейную жизнь, произвольным посягательствам на неприкосновенность его жилища, тайну его корреспонденции или на его честь и репутацию. Каждый человек имеет право на защиту закона от такого вмешательства или таких посягательств.

Статья 13

1. Каждый человек имеет право свободно передвигаться и выбирать себе местожительство в пределах каждого государства.

2. Каждый человек имеет право покидать любую страну, включая свою собственную, и возвращаться в свою страну.

Статья 14

1. Каждый человек имеет право искать убежище от преследования в других странах и пользоваться этим убежищем.

2. Это право не может быть использовано в случае преследования, в действительности основанного на совершении неполитического преступления или деяния, противоречащего целям и принципам Организации Объединенных Наций.

Статья 15

1. Каждый человек имеет право на гражданство.

2. Никто не может быть произвольно лишен своего гражданства или права изменить свое гражданство.

Статья 16

1. Мужчины и женщины, достигшие совершеннолетия, имеют право без всяких ограничений по признаку расы, национальности или религии вступать в брак и основывать семью. Они пользуются одинаковыми правами в отношении вступления в брак, во время состояния в браке и во время его расторжения.

2. Брак может быть заключен только при свободном и полном согласии обеих вступающих в брак сторон.

3. Семья является естественной и основной ячейкой общества и имеет право на защиту со стороны общества и государства.

Статья 17

1. Каждый человек имеет право владеть имуществом как единолично, так и совместно с другими.

2. Никто не должен быть произвольно лишен своего имущества.

Статья 18

Каждый человек имеет право на свободу мысли, совести и религии; это включает свободу менять свою религию или убеждения и свободу исповедовать свою религию или убеждения как единолично, так и сообща с другими, публичным или частным порядком в учении, богослужении и выполнении религиозных и ритуальных порядков.

Статья 19

Каждый человек имеет право на свободу убеждений и на свободное выражение их; это право включает свободу беспрепятственно придерживаться своих убеждений и свободу искать, получать и распространять информацию и идеи любыми средствами и независимо от государственных границ.

Статья 20

1. Каждый человек имеет право на свободу мирных собраний и ассоциаций.

2. Никто не может быть принуждаем вступать в какую-либо ассоциацию.

Статья 21

1. Каждый человек имеет право принимать участие в управлении своей страной непосредственно или через посредство свободно избранных представителей.

2. Каждый человек имеет право равного доступа к государственной службе в своей стране.

3. Воля народа должна быть основой власти правительства; эта воля должна находить себе выражение в периодических и нефальсифицированных выборах, которые должны проводиться при всеобщем и равном избирательном праве, путем тайного голосования или же посредством других равнозначных форм, обеспечивающих свободу голосования.

Статья 22

Каждый человек, как член общества, имеет право на социальное обеспечение и на осуществление необходимых для поддержания его достоинства и для свободного развития его личности прав в экономической, социальной и культурной областях через посредство национальных усилий и международного сотрудничества и в соответствии со структурой и ресурсами каждого государства.

Статья 23

1. Каждый человек имеет право на труд, на свободный выбор работы, на справедливые и благоприятные условия труда и на защиту от безработицы.

2. Каждый человек, без какой-либо дискриминации, имеет право на равную оплату за равный труд.

3. Каждый работающий имеет право на справедливое и удовлетворительное вознаграждение, обеспечивающее достойное человека существование для него самого и его семьи, и дополняемое, при необходимости, другими средствами социального обеспечения.

4. Каждый человек имеет право создавать профессиональные союзы и входить в профессиональные союзы для защиты своих интересов.

Статья 24

Каждый человек имеет право на отдых и досуг, включая право на разумное ограничение рабочего дня и на оплачиваемый периодический отпуск.

Статья 25

1. Каждый человек имеет право на такой жизненный уровень, включая пищу, одежду, жилище, медицинский уход и необходимое социальное обслуживание, который необходим для поддержания здоровья и благосостояния его самого и его семьи, и право на обеспечение на случай безработицы, болезни, инвалидности, вдовства, наступления старости или иного случая утраты средств к существованию по не зависящим от него обстоятельствам.

2. Материнство и младенчество дают право на особое попечение и помощь. Все дети, родившиеся в браке или вне брака, должны пользоваться одинаковой социальной защитой.

Статья 26

1. Каждый человек имеет право на образование. Образование должно быть бесплатным по меньшей мере в том, что касается начального и общего образования. Начальное образование должно быть обязательным. Техническое и профессиональное образование должно быть общедоступным, и высшее образование должно быть одинаково доступным для всех на основе способностей каждого.

2. Образование должно быть направлено к полному развитию человеческой личности и к увеличению уважения к правам человека и основным свободам. Образование должно содействовать взаимопониманию, терпимости и дружбе между всеми народами, расовыми и религиозными группами и должно содействовать деятельности Организации Объединенных Наций по поддержанию мира.

3. Родители имеют право приоритета в выборе вида образования для своих малолетних детей.

Статья 27

1. Каждый человек имеет право свободно участвовать в культурной жизни общества, наслаждаться искусством, участвовать в научном прогрессе и пользоваться его благами.

2. Каждый человек имеет право на защиту его моральных и материальных интересов, являющихся результатом научных, литературных или художественных трудов, автором которых он является.

Статья 28

Каждый человек имеет право на социальный и международный порядок, при котором права и свободы, изложенные в настоящей Декларации, могут быть полностью осуществлены.

Статья 29

1. Каждый человек имеет обязанности перед обществом, в котором только и возможно свободное и полное развитие его личности.

2. При осуществлении своих прав и свобод каждый человек должен подвергаться только таким ограничениям, какие установлены законом исключительно с целью обеспечения должного признания и уважения прав и свобод других и удовлетворения справедливых требований морали, общественного порядка и общего благосостояния в демократическом обществе.

3. Осуществление этих прав и свобод ни в коем случае не должно противоречить целям и принципам Организации Объединенных Наций.

Статья 30

Ничто в настоящей Декларации не может быть истолковано как предоставление какому-либо государству, группе лиц или отдельным лицам права заниматься какой-либо деятельностью или совершать действия, направленные к уничтожению прав и свобод, изложенных в настоящей Декларации.

[27]

Представители Французского Народа, составляющие Национальное Собрание, принимая во внимание, что неведение, забвение или презрение прав человека суть единственные причины общественных бедствий и порчи правительств, решили изложить в торжественном объявлении естественные, неотчуждаемые и священные права человека, дабы это объявление, будучи постоянно пред глазами всех членов общественного союза, непрестанно напоминало им их права и обязанности; дабы акты законодательной и исполнительной власти, при возможности во всякий момент сличить их с целью всякого политического учреждения, были тем более уважаемы; дабы требования граждан, основываясь отныне на простых и неоспоримых началах, обращались всегда к поддержанию Конституции и к всеобщему благополучию. — Вследствие сего Национальное Собрание признает и объявляет, пред лицом и под покровительством Верховного Существа, следующие права человека и гражданина.

Ст. 1. Люди рождаются и пребывают свободными и равными в правах. Общественные отличия могут быть основаны только на общей пользе.

2. Цель всякого политического союза есть охрана естественных и неотъемлемых прав человека. Эти права суть свобода, собственность, безопасность и сопротивление угнетению.

3. Начало всякого суверенитета заключается, по существу, [28]

в народе. Никакое лицо, ни совокупность лиц не может осуществлять власти, которая бы не проистекала, положительным образом, от народа.

4. Свобода состоит в возможности делать все, что не вредит другому: таким образом осуществление естественных прав каждого человека ограничено лишь теми пределами, которые обеспечивают другим членам общества пользование теми же самыми правами. Эти пределы могут быть установлены лишь Законом.

5. Закон имеет право запрещать только вредные для общества действия. Что не запрещено Законом, тому нельзя препятствовать, и никого нельзя принуждать делать того, чего Закон не предписывает.