|

Donetsk People’s Republic Донецкая Народная Республика |

|

|---|---|

|

Military occupation and annexation |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Государственный Гимн Донецкой Народной Республики Gosudarstvennyy Gimn Donetskoy Narodnoy Respubliki «State Anthem of the Donetsk People’s Republic»[4][5] |

|

|

|

| Occupied country | Ukraine |

| Occupying power | Russia |

| Breakaway state[a] | Donetsk People’s Republic (2014–2022) |

| Disputed republic of Russia | Donetsk People’s Republic (2022–present) |

| Entity established | 7 April 2014[8] |

| Eastern Ukraine offensive | 24 February 2022 |

| Annexation by Russia | 30 September 2022 |

| Administrative centre | Donetsk |

| Government | |

| • Body | People’s Council |

| • Head of the DPR | Denis Pushilin |

| Population

(2019)[9] |

|

| • Total | 2,220,500[b] |

The Donetsk People’s Republic (Russian: Донецкая Народная Республика, tr. Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, IPA: [dɐˈnʲetskəjə nɐˈrodnəjə rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə]; abbreviated as DPR or DNR, Russian: ДНР) is a disputed entity created by Russian-backed separatists[10][11] in eastern Ukraine, which claims Donetsk Oblast. It began as a breakaway state (2014–2022) and was then annexed by Russia in 2022. The city of Donetsk is the claimed capital city.

Pro-Russian unrest erupted in the Donbas region in response to the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity. In April 2014, armed pro-Russian separatists seized government buildings and declared the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) as independent states, which received no international recognition prior to 2022. Ukraine and others viewed them as Russian puppet states[1][2][3] and as terrorist organisations.[12] This sparked the War in Donbas, part of the wider Russo-Ukrainian War which also saw the Russian occupation and annexation of Crimea. The Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Militias occupied almost half of the two oblasts and were at war with the Ukrainian military for the next eight years.

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognised the DPR and LPR as sovereign states. According to some observers, this made the DPR a partially recognized state.[13][14] Three days later, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, partially under the pretext of protecting the republics. Russian forces captured more of Donetsk Oblast, which became part of the DPR. In September 2022, Russia announced the annexation of the DPR and other occupied territories, following disputed referendums. The United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling on countries not to recognise what it called the «attempted illegal annexation» and demanded that Russia «immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw».[15][16]

The Head of the Donetsk People’s Republic is Denis Pushilin, and its parliament is the People’s Council. The ideology of the DPR is said to combine various strands of Russian nationalism: Fascist, Orthodox, neo-imperialist and neo-Soviet.[17][18] Russian far-right groups played an important role in the DPR, especially in its early days.[17][18] Organizations such as the United Nations Human Rights Office and Human Rights Watch have reported human rights abuses in the DPR, including internment, torture, extrajudicial killings, forced conscription, as well as political and media repression. The Donetsk People’s Militia has also been held responsible for war crimes, among them the shootdown of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17.[19]

History

Ukrainian riot police guarding the entrance to the RSA building on 7 March 2014

Ukrainian military roadblocks in Donetsk oblast on 8 May 2014

The Luhansk and Donetsk Peoples Republics are located in the historical Donbas region of Eastern Ukraine. Since Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Eastern and Western Ukraine typically have voted for different candidates in presidential elections. Viktor Yanukovych, a Donetsk native, was elected as President of Ukraine in 2010. Eastern Ukrainian dissatisfaction with the government can also be attributed to the Euromaidan Protests which began in November 2013,[20] as well as Russian support[21] due to tension in Russia–Ukraine relations over Ukraine’s geopolitical orientation.[22] President Yanukovych’s overthrow in the 2014 Ukrainian revolution led to protests in Eastern Ukraine, which gradually escalated into an armed conflict between the newly formed Ukrainian government and the local armed militias.[23] The pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine was originally characterised by riots and protests which had eventually escalated into the storming of government offices.[24]

Formation (2014–2015)

Foundations

Pro-Russian separatists occupying the Donetsk RSA building on 7 April 2014

Sloviansk city council under the control of heavily armed men on 14 April 2014

On 7 April 2014, between 1,000 and 2,000[25] pro-Russian rebels attended a rally in Donetsk pushing for a Crimea-style referendum on independence from Ukraine. Ukrainian media claimed that the proposed referendum had no status-quo option.[26] Afterwards, 200–1000 separatists[27][25] stormed and took control of the first two floors of the government headquarters of the Regional State Administration (RSA), breaking down doors and smashing windows. The separatists demanded a referendum to join Russia, and said they would otherwise take unilateral control and dismiss the elected government.[28][29][30] When the session was not held, the unelected separatists held a vote within the RSA building and overwhelmingly backed the declaration of a Donetsk People’s Republic.[31] According to the Russian ITAR-TASS, the declaration was voted by some regional legislators, while Ukrainian media claimed that neither the Donetsk city council nor district councils of the city delegated any representatives to the session.[32][33]

The political leadership initially consisted of Denis Pushilin, self-appointed as chairman of the government,[34][35] while Igor Kakidzyanov was named as the commander of the People’s Army.[36] Vyacheslav Ponomarev became the self-proclaimed mayor of the city of Sloviansk.[37] Ukrainian-born pro-Russian activist Pavel Gubarev,[38][39] an Anti-Maidan activist, a former member of the neo-Nazi Russian National Unity paramilitary group in 1999–2001 and former member of the left-wing populist Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine, proclaimed himself the People’s Governor of the Donetsk Region.[40][41][42][43] He was arrested on charges of separatism and illegal seizure of power but released in a hostage swap.[44][45] Alexander Borodai, a Russian citizen claiming to be involved in the Russian annexation of Crimea, was appointed as Prime Minister, while Igor Girkin was made Defence Minister. Borodai had a past working for an openly anti-semitic and fascist Russian newspaper Zavtra which had called for pogroms against Jews.[46][47]

On 6 April, the group’s leaders announced that a referendum on whether Donetsk Oblast should «join the Russian Federation», would take place «no later than May 11th, 2014.»[48] Additionally, the group’s leaders appealed to Russian President Vladimir Putin to send Russian peacekeeping forces to the region.[48][49]

On the morning of 8 April, the ‘Patriotic Forces of Donbas’, a pro-Kyiv group that was formed on 15 March earlier that year by 13 pro-Kyiv NGOs, political parties and individuals,[50][51] issued a statement «cancelling» the other group’s declaration of independence, citing complaints from locals.[52][53][54]

The Donetsk Republic organisation continued to occupy the RSA and upheld all previous calls for a referendum and the release of their leader Pavel Gubarev.[55][c] On 8 April, about a thousand people rallied in front of the RSA listening to speeches about the Donetsk People’s Republic and to Soviet and Russian music.[56] Ukrainian media stated that a number of Russian citizens, including one leader of a far-right militant group, had also taken part in the events.[57] The OSCE reported that all the main institutions of the city observed by the Monitoring Mission seemed to be working normally as of 16 April.[58] On 22 April, separatists agreed to release the session hall of the building along with two floors to state officials.[59] The ninth and tenth floors were later released on 24 April.[60] On the second day of the Republic, organisers decided to pour all of their alcohol out and announce a prohibition law after issues arose due to excessive drinking in the building.[61]

People carrying the DPR flag in Donetsk, 9 May 2014

On 7 May, Russian president Vladimir Putin asked the separatists to postpone the proposed referendum to create the necessary conditions for dialogue. Despite Putin’s comments, the Donetsk Republic group said they would still carry out the referendum.[62] The same day, Ukraine’s security service (SBU) released an alleged audio recording of a phone call between a Donetsk separatist leader and leader of one of the splinter groups of former Russian National Unity Alexander Barkashov.[63] In the call, the voice said to be Barkashov insisted on falsifying the results of the referendum.[64] SBU stated that this tape is a definitive proof of the direct involvement of Russian government with preparations for the referendum.[63]

Polling during this period indicated that around 18 per cent of Donetsk Oblast residents supported the seizures of administrative buildings while 72 per cent disapproved. Twelve per cent were in favour of Ukraine and Russia uniting into a single state, a quarter were in favour of regional secession to join Russia, 38.4 per cent supported federalisation, 41.1 per cent supported a unitary Ukraine with decentralisatised power, and 10.6 per cent supported the status quo.[65][66] In an August 2015 poll, with 6500 respondents from 19 cities of Donetsk Oblast, 29 per cent supported the DPR and 10 per cent considered themselves to be Russian patriots.[67]

Ukrainian authorities released separatist leader Pavel Gubarev and two others in exchange for three people detained by the Donetsk Republic.[68]

On 15 April 2014, acting Ukrainian President Olexander Turchynov announced the start of a military counteroffensive to confront the pro-Russian militants, and on 17 April, tensions de-escalated as Russia, the US, and the EU agreed on a roadmap to eventually end the crisis.[69][70] However, officials of the People’s Republic ignored the agreement and vowed to continue their occupations until a referendum was accepted or the government in Kyiv resigned.[71]

11 May independence referendum

The planned referendum was held on 11 May, disregarding Vladimir Putin’s appeal to delay it.[72] The organisers claimed that 89% voted in favour of self-rule, with 10% against, on a turnout of nearly 75%. The results of the referendums were not officially recognised by any government;[73] Germany and the United States also stated that the referendums had «no democratic legitimacy»,[74] while the Russian government expressed respect for the results and urged a civilised implementation.[75]

On the day after the referendum, the People’s Soviet of the DPR proclaimed Donetsk to be a sovereign state with an indefinite border and asked Russia «to consider the issue of our republic’s accession into the Russian Federation».[citation needed] It also announced that it would not participate in the Ukrainian presidential election which took place on 25 May.[76]

The first full Government of the DPR was appointed on 16 May 2014.[77] It consisted of several ministers who were previously Donetsk functionaries, a member of the Makiivka City Council, a former Donetsk prosecutor, a former member of the special police Alpha Group, a member of the Party of Regions (who allegedly coordinated «Titushky» (Viktor Yanukovych supporters) during Euromaidan) and Russian citizens.[77] This government imposed martial law on 16 July.[78]

Elections in the DPR and LPR were held on 2 November 2014, after the territories had boycotted the 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election on 26 October.[79] The results were not recognised by any country.[80][81]

The DPR adopted a memorandum on 5 February 2015, declaring itself the successor to the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic and Bolshevik revolutionary Fyodor Sergeyev—better known by his alias «Artyom»—as the country’s founding father.[82]

Static war period (2015–2022) | Peace proposals and stalemate

On 12 February 2015, the DPR and LPR leaders, Alexander Zakharchenko and Igor Plotnitsky, signed the Minsk II agreement.[83] According to the agreement, amendments to the Ukrainian constitution should be introduced, including «the key element of which is decentralisation» and the holding of elections in the LPR and DPR within the lines of the Minsk Memorandum. In return, the rebel-held territory would be reintegrated into Ukraine.[83][84] In an effort to stabilise the ceasefire in the region, particularly the disputed and strategically important town of Debaltseve, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko called for a UN-led peacekeeping operation in February 2015 to monitor compliance with the Minsk agreement.[85] The Verkhovna Rada did not ratify the changes in the constitution needed for the Minsk agreement.[86][87][88]

On 20 May 2015, the leadership of the Federal State of Novorossiya, a proposed confederation of the DPR and LPR, announced the termination of the confederation project.[89][90]

On 15 June 2015, several hundred people protested in the centre of Donetsk against the presence of BM-21 «Grad» launchers in a residential area. The launchers had been used to fire at Ukrainian positions, provoking return fire and causing civilian casualties.[91] A DPR leader said that its forces were indeed shelling from residential areas (mentioning school 41 specifically), but that «the punishment of the enemy is everyone’s shared responsibility».[92]

Issuance of the first DPR passports in March 2016 by DPR leader Alexander Zakharchenko. Zakharchenko was assassinated in 2018.[93]

On 2 July 2015, DPR leader Aleksandr Zakharchenko ordered local elections to be held on 18 October 2015 «in accordance with the Minsk II agreements».[94] The 2015 Ukrainian local elections were set for 25 October 2015.[95] This was condemned by Ukraine.[94]

On 4 September 2015, there was a sudden change in the DPR government, where Denis Pushilin replaced Andrey Purgin in the role of speaker of the People’s Council and, in his first decision, fired Aleksey Aleksandrov, the council’s chief of staff, Purgin’s close ally. This happened in absence of Purgin and Aleksandrov who were held at the border between Russia and DPR, preventing their return to the republic. Aleksandrov was accused of «destructive activities» and an «attempt to illegally cross the border» by the republic’s Ministry of Public Security. Russian and Ukrainian media commented on these events as yet another coup in the republic’s authorities.[96][97]

After a Normandy four meeting in which the participants agreed that elections in territories controlled by DPR and LPR should be held according to Minsk II rules, both postponed their planned elections to 21 February 2016.[98] Vladimir Putin used his influence to reach this delay.[99] The elections were then postponed to 20 April 2016 and again to 24 July 2016.[100] On 22 July the elections were again postponed to 6 November.[101]

In July 2016, over a thousand people, mainly small business owners, protested in Horlivka against corruption and taxes, which included charging customs fees on imported goods.[102]

On 2 October 2016, the DPR and LPR held primaries in were voters voted to nominate candidates for participation in the 6 November 2016 elections.[103] Ukraine denounced these primaries as illegal.[103] The DPR finally held elections on 11 November 2018. These were described as «predetermined and without alternative candidates»[104] and not recognised externally.[105]

On 16 October 2016, a prominent Russian citizen and DPR military leader Arsen Pavlov was killed by an improvised explosive device in his Donetsk apartment’s elevator.[106] Another DPR military commander, Mikhail Tolstykh, was killed by an explosion while working in his Donetsk office on 8 February 2017.[107] On 31 August 2018, Head and Prime Minister Alexander Zakharchenko was killed in an explosion in a cafe in Donetsk.[108] After his death Dmitry Trapeznikov was appointed as head of the government until September 2019 when he was nominated mayor of Elista, capital of Kalmyk Republic in Russia.[109] According to Ukrainian authorities, 50 Ukrainian soldiers were killed in clashes with Donbas separatists in 2020.[110]

In January 2021, the DPR and LPR stated in a «doctrine Russian Donbas» that they aimed to seize all of the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblast under control by the Ukrainian government «in the near future.»[111] The document did not specifically state the intention of DPR and LPR to be annexed by Russia.[111]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

The general mobilization in the Donetsk People’s Republic began on 19 February 2022 – 5 days before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Tens of thousands of local residents were forcibly mobilized for the war. According to the Eastern Human Rights Group, as of mid-June, about 140,000 people were forcibly mobilized in the DPR and LPR, of which from 48,000 to 96,000 were sent to the front and the rest to logistics support.[112][113]

On 21 February 2022, Russia recognised the independence of the DPR and LPR.[114] The next day, the Federation Council of Russia authorised the use of military force, and Russian forces openly advanced into the separatist territories.[115] Russian president Vladimir Putin declared that the Minsk agreements «no longer existed», and that Ukraine, not Russia, was to blame for their collapse.[116] A Russian military attack into Ukrainian government-controlled territory began on the morning of 24 February,[117] when Putin announced a «special military operation» to «demilitarise and denazify» Ukraine.[118][119]

In the course of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, around 55% of Donetsk Oblast came under the control of Russia and the DPR by June 2022.[120] In the south of Donetsk Oblast, the Russian Armed Forces laid siege to Mariupol for almost three months.[121] According to Ukrainian sources, an estimated 22,000 civilians were killed[122] and 20,000 to 50,000 were illegally deported to Russia by June 2022.[123][124][125] A vehicle convoy of 82 ethnic Greeks was able to leave the city via a humanitarian corridor.[126][127]

On 19 April 2022, a town hall assembly was reportedly organized in Russian-occupied Rozivka, where a majority of attendees (mainly seniors) voted by hand to join the Donetsk People’s Republic. This came despite two hurdles: the raion was outside the borders claimed by the DPR, and the raion had not existed since 18 July 2020. The vote was claimed to be rigged, and organizers threatened anyone voting against it with arrest.[128][129]

On 21 May 2022, the town of Oskil in the Kharkiv Oblast was declared part of the DPR. [130] The town was later recaptured by Ukrainian forces during the Kharkiv Counteroffensive.

Dmitry Medvedev, the former Russian president and as of July 2022 vice chairman of the Russian Security Council, in July 2022 shared a map of Ukraine where most of Ukraine, including DPR, had been absorbed by Russia.[131]

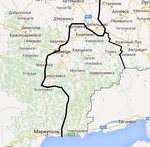

A map of Russia (including illegally annexed territories), with the Donetsk People’s Republic highlighted

Der Spiegel reported that forcibly recruited men from Donbas were used as cannon fodder. According to DPR officials, more than 3,000 were killed and over 13,000 wounded, «a casualty rate of 80 percent of the initial fighting force.»[132] Human rights activists reported a huge – up to 30,000 people as of August 2022 – death toll among mobilized recruits in clashes with the well-trained Armed Forces of Ukraine.[112][113] On 16 August 2022, Vladimir Putin stated that «the objectives of this operation are clearly defined – ensuring the security of Russia and our citizens, protecting the residents of Donbass from genocide.»[133]

Annexation by Russia

On 20 September 2022, the People’s Council of the Donetsk People’s Republic scheduled a «referendum» on the republic’s entry into Russia as a federal subject for 23–27 September.[134] On 21 September, Russian President Putin announced a partial mobilization in Russia. He said that «in order to protect our motherland, its sovereignty and territorial integrity, and to ensure the safety of our people and people in the liberated territories», he decided to declare a partial mobilization.[135] On 12 October 2022, the United Nations General Assembly voted in Resolution ES-11/4 to condemn the annexation. The resolution received a vast majority of 143 countries in support of condemning Russia’s annexation, 35 abstaining, and only 5 against condemning Russia’s annexation.[16]

Government and politics

In early April 2014, a Donetsk People’s Council was formed out of protesters who occupied the building of the Donetsk Regional Council on 6 April 2014.[28][29][136] The New York Times described the self-proclaimed state as neo-Soviet,[137] while Al Jazeera described it as neo-Stalinist and a «totalitarian, North Korea-like statelet».[138] Administration proper in DPR territories is performed by those authorities which performed these functions prior to the war in Donbas.[139] The DPR leadership has also appointed mayors.[140][141] Some sources described the «Donetsk People’s Republic» during this period as a Russian puppet government.[142][143][144]

On 5 February 2020, Denis Pushilin unexpectedly appointed Vladimir Pashkov, a Russian citizen and former deputy governor of Russia’s Irkutsk Oblast, as the chairman of the government.[145] This appointment was received in Ukraine as a demonstration of direct control over DPR by Russia.[146]

Several Russian officials were appointed to cabinet posts and prime ministership of the DPR in June and July 2022.[147]

Legislature

The parliament of the Donetsk People’s Republic is the People’s Council[148] and has 100 deputies.[79]

Political parties

Political rally in the DPR, 20 December 2014

|

|

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: No mention of 2018 elections. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (February 2022) |

Political parties active in the DPR include Donetsk Republic, the Communist Party of the Donetsk People’s Republic, Free Donbas, and the New Russia Party. Donetsk Republic and the Communists endorsed Prime Minister Alexander Zakharchenko’s candidature for the premiership in 2014.[149][150][better source needed] In the ensuing 2014 elections, the Communists were banned from participating independently because they had «made too many mistakes» in their submitted documents.[151] Donetsk Republic gained a majority in the DPR People’s Soviet with 68.53% of the vote and 68 seats. Free Donbas, including candidates from the Russian-nationalist extremist New Russia Party, won 31.65% of the vote and 32 seats.

Passports and citizenship

In March 2016, the DPR began to issue passports[152] despite a 2015 statement by Zakharchenko that, without at least partial recognition of DPR, local passports would be a «waste of resources».[152] In November 2016 the DPR announced that all of its citizens had dual Ukrainian/Donetsk People’s Republic citizenship.[153]

In June 2019, Russia started giving Russian passports to the inhabitants of the DPR and Luhansk People’s Republic under a simplified procedure allegedly on «humanitarian grounds» (such as enabling international travel for eastern Ukrainian residents whose passports have expired).[154] Since December 2019 Ukrainian passports are no longer considered a valid identifying document in the DPR and Ukrainian licence plates were declared illegal.[155] Meanwhile, the previous favourable view of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in the DPR press was replaced with personal accusations of genocide and «crimes against Donbas», and proposals of organising a tribunal against him in absentia.[155] In March 2020 Russian was declared to be the only state language of the DPR;[156][unreliable source?] previously in its May 2014 constitution, the DPR had declared both Russian and Ukrainian its official languages.[77]

According to the Ukrainian press, by mid-2021, local residents received half a million Russian passports.[157] Deputy Kremlin Chief of Staff Dmitry Kozak stated in a July 2021 interview with Politique internationale that 470,000 local residents had received Russian passports; he added that «as soon as the situation in Donbass is resolved ….The general procedure for granting citizenship will be restored.»[158]

Military

Banner of the Ministry of Defence

The Donbas People’s Militia was formed by Pavel Gubarev, who was elected People’s Governor of Donetsk Oblast and Igor Girkin, appointed the Minister of Defence of the Donetsk People’s Republic.[159]

The People’s Militia of the DPR (Russian: Вооружённые силы ДНР) comprise the Russian separatist forces in the DPR.

On 10 January 2020 president of the non-recognised pro-Russian Abkhazia accused DPR of staging a coup in his country. DPR commander Akhra Avidzba was commanding on the spot.[160] Unlike South Ossetia, Abkhazia had not then recognised DPR.[161]

Problems of governance

Police in Donetsk wearing insignia related to the Donetsk People’s Republic, 20 September 2014

DPR military parade in Donetsk, 9 May 2018

OSCE monitors met with the self-proclaimed mayor of Sloviansk, Volodymyr Pavlenko, on 20 June 2014.[162] According to him, sewage systems in Sloviansk had collapsed, resulting in the release of least 10,000 litres of untreated sewage into the river Sukhyi Torets [uk], a tributary of the Seversky Donets. He called this an «environmental catastrophe», and said that it had the potential to affect both Russia and Ukraine.[162]

As of May 2014, the Ukrainian Government was paying wages and pensions for the inhabitants of the DPR.[163][164][165] The closing of bank branches led to problems in receiving these,[166][167][168] especially since the National Bank of Ukraine ordered banks to suspend financial transactions in places which are not controlled by the Ukrainian authorities on 7 August 2014.[169] Only the Oschadbank (State Savings Bank of Ukraine) continued to function in territories controlled by the DPR, but it also closed its branches there on 1 December 2014.[169][170] In response, tens of thousands of pensioners have registered their address as being in Ukrainian-controlled areas while still living in separatist-controlled areas, and must travel outside of separatist areas to collect their pensions on a monthly basis.[171]

In October 2014, the DPR announced the creation of its own central bank and tax office, obliging residents to register to the DPR and pay taxes to it.[172] Some local entrepreneurs refused to register.[172]

According to the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine a number of local mutinies have taken place due to unpaid wages and pensions, the council claims that on 24 November 2014, the local «Women Resistance Battalion» presented to Zakharchenko an ultimatum to get out of Donetsk in two months.[173]

Since April 2015, the DPR has been issuing its own vehicle number plates.[174]

The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine reported that in the DPR, «parallel ‘justice systems’ have begun operating».[175] They found this new judiciary to be «non-transparent, subject to constant change, seriously under-resourced and, in many instances, completely non-functional».[175]

Law and order

The Ministry of Internal Affairs is the DPR’s agency responsible for implementing law and order.[176]

In 2014, the DPR introduced the death penalty for cases of treason, espionage, and assassination of political leaders. There had already been accusations of extrajudicial execution.[177] After 2015 a number of DPR and LPR field commanders and other significant figures were killed or otherwise removed from power.[178][179] This included Cossack commander Pavel Dryomov, commander of Private Military Company (ЧВК) Dmitry Utkin («Wagner»), Alexander Bednov («Batman»), Aleksey Mozgovoy, Yevgeny Ishchenko, Andrei Purgin and Dmitry Lyamin (the last two arrested).[180][181] In August 2016 Igor Plotnitsky, head of LPR, was seriously injured in a car bombing attack in Luhansk.[182] In September 2016 Evgeny Zhilin (Yevhen Zhylin), leader of the separatist «Oplot» unit, was killed in a restaurant near Moscow.[183][184] In October 2016 military commander Arseniy Pavlov («Motorola») was killed by an IED planted at his house.[185] In February 2017 a bomb planted in an office killed Mikhail Tolstykh («Givi»).[186] On 31 August 2018 DPR leader Alexander Zakharchenko was killed by a bomb in a restaurant in Donetsk.[187] The DPR and Russia blamed the Security Service of Ukraine; Ukraine rejected these accusations, stating that Zakharchenko’s death was the result of civil strife in the DPR.[179]

In May 2015, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed four laws concerning decommunisation in Ukraine. Various cities and many villages in Donbas were renamed. The Ukrainian decommunisation laws were condemned by the DPR.[188]

In addition to Ukrainian prisoners of war there are reports of «thousands» of prisoners who were arrested as part of internal fighting between various militant groups inside DPR.[189]

Aiden Aslin, Shaun Pinner, Brahim Saadoune have been sentenced to death. The DPR lifted the death penalty moratorium. [190]

Right-wing nationalism

According to a 2016 report by the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI), Russian ethnic and imperialist nationalism has shaped the official ideology of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.[18] During the War in Donbas, especially at the beginning, far-right groups played an important role on the pro-Russian side, arguably more so than on the Ukrainian side.[18][17] Afterward, the pro-Russian far-right groups gradually became less important in Donbas as the need for Russian radical nationalists started to disappear.[18]

According to Marlène Laruelle, separatist ideologues in Donbas produced an ideology composed of three strands of Russian nationalism: Fascist, Orthodox, and Soviet.[17]

Members and former members of Russian National Unity (RNU), the National Bolshevik Party, Eurasian Youth Union, and Cossack groups formed branches to recruit volunteers to join the separatists.[18][191][192][193] A former RNU member, Pavel Gubarev, was founder of the Donbas People’s Militia and first «governor» of the Donetsk People’s Republic.[18][194] RNU is particularly linked to the Russian Orthodox Army,[18] one of a number of separatist units described as «pro-Tsarist» and «extremist» Orthodox nationalists.[195][18] Neo-Nazi unit ‘Rusich’[18] is part of the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary group in Ukraine which has been linked to far-right extremism.[196][197]

Some of the most influential far-right nationalists among the Russian separatists are neo-imperialists, who seek to revive the Russian Empire.[18] These included Igor ‘Strelkov’ Girkin, the minister of defence of the Donetsk People’s Republic, who espouses Russian neo-imperialism and ethno-nationalism.[18] The Russian Imperial Movement, a white supremacist militant group,[196] has recruited thousands of volunteers to join the separatists.[195] Some separatists have flown the black-yellow-white Russian imperial flag,[18] such as the Sparta Battalion. In 2014, volunteers from the National Liberation Movement joined the Donetsk People’s Militia bearing portraits of Tsar Nicholas II.[191]

Other Russian nationalist volunteers involved in separatist militias included members of the Eurasian Youth Union, and of banned groups such as the Slavic Union and Movement Against Illegal Immigration.[192] Another Russian separatist paramilitary unit, the Interbrigades, is made up of activists from the National Bolshevik (Nazbol) group Other Russia.[18] An article in Dissent noted that «despite their neo-Stalinist paraphernalia, many of the Russian-speaking nationalists Russia supports in the Donbass are just as right-wing as their counterparts from the Azov Battalion».[198]

In July 2015, the head of the Donetsk People’s Republic, Alexander Zakharchenko, said at a press conference that he respected Ukraine’s far-right party Right Sector «when they beat up the gays in Kyiv and when they tried to depose Poroshenko».[199]

While far-right activists played a part in the early days of the conflict, their importance was often exaggerated, and their importance on both sides of the conflict declined over time. The political climate in Donetsk further pushed far-right groups into the margins.[18]

In April 2022, news outlets noted that a video posted on Donetsk People’s Republic’s website showed Denis Pushilin awarding a medal to Lieutenant Roman Vorobyov (Somalia Battalion) while Vorobyov was wearing patches affiliated with neo-Nazism: the Totenkopf used by the 3rd SS Panzer Division, and the valknut. However, the video did not show Vorobyov getting his medal when it was posted on Pushilin’s website.[200][201]

Recognition and international relations

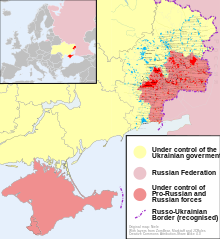

Crimea, which Russia annexed in 2014, is shown in pink. Pink in the Donbas region represents areas held by the DPR/LPR in September 2014 (cities in red)

The Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) initially sought recognition as a sovereign state following its declaration of independence in April 2014. Subsequently, the DPR willingly acceded to the Russian Federation as a Russian federal subject in September–October 2022, effectively ceasing to exist as a sovereign state in any capacity and revoking its status as such in the eyes of the international community. The DPR claims direct succession to Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast.

From 2014 to 2022, Ukraine, the United Nations, and most of the international community regarded the DPR as an illegal entity occupying a portion of Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast (see: International sanctions during the Russo-Ukrainian War). The Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), which had a similar backstory, was regarded in the exact same way. Crimea’s status was treated slightly differently since Russia annexed that territory immediately after its declaration of independence in March 2014.

Up until February 2022, Russia did not recognise the DPR, although it maintained informal relations with the DPR. On 21 February 2022, Russia officially recognised the DPR and the LPR at the same time,[202] marking a major escalation in the 2021–2022 diplomatic crisis between Russia and Ukraine. Three days later, on 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of the entire country of Ukraine, partially under the pretext of protecting the DPR and the LPR. The war had wide-reaching repercussions for Ukraine, Russia, and the international community as a whole (see: War crimes, Humanitarian impact, Environmental impact, Economic impact, and Ukrainian cultural heritage). In September 2022, Russia made moves to consolidate the territories that it had occupied in Ukraine, including Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts. Russia officially annexed these four territories in September–October 2022.

Between February 2022 and October 2022, in addition to receiving Russian recognition, the DPR was recognised by North Korea (13 July 2022)[203] and Syria (29 June 2022).[204][205] This means that three United Nations member states recognised the DPR in total throughout its period of de facto independence. The DPR was also recognised by three other breakaway entities: the LPR, South Ossetia (19 June 2014),[206] and Abkhazia (25 February 2022).[207]

Relations with Ukraine

The Ukrainian government passed the «Law on the special status of Donbas [uk]» on 16 September 2014, which designated a special status within Ukraine on certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions (CADLR), in line with the Minsk agreements.[citation needed] The status lasted for three years, and then was extended annually several times.[208]

In January 2015, Ukraine declared the Russia-backed separatist republics in Donbas to be terrorist organizations.[209]

Relations with Russia

Russia has recognised identity documents, diplomas, birth, and marriage certificates and vehicle registration plates as issued by the DPR and the LPR since 18 February 2017,[210] enabling people living in DPR-controlled territories to travel, work, or study in Russia.[210] According to the decree, it was signed «to protect human rights and freedoms» in accordance with «the widely recognised principles of international humanitarian law».[211]

On February 21, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed agreements on friendship, cooperation, and assistance with DPR and the LPR, coinciding with Russia’s official recognition of the two quasi-states.[202] The Russian State Duma had approved a draft resolution appealing for him to recognize both quasi-states on 15 February.[212] Shortly afterwards, Abkhazia also recognized the independence of the DPR.

Relations with extremist groups in Europe

According to the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, a number of European politicians from extreme-right and extreme-left have received all-expenses-paid trips to the Donetsk People’s Republic.[213]

Far-right

As well as Russian far-right groups (see #Right-wing nationalism), the DPR has cultivated relations with other European far-right groups and activists. The Lansing Institute for Global Threats and Democracies Studies acquired a memorandum of cooperation between the DPR and the far-right Russian Imperial Movement, which trains foreign volunteers; including members of the neo-Nazi Atomwaffen Division and Der Dritte Weg.[214][215][216][217][218][219] Professor Anton Shekhovtsov, an expert on far-right movements in Russia and abroad, reported in 2014 that Polish neo-fascist group «Falanga», Italian far-right group «Millennium» and French Eurasianists had joined the Donbas separatists.[220][221][222] Members of Serbian Action have also joined the Donbas separatists.[223]

According to Italian newspaper la Repubblica, well-known Italian neo-fascist Andrea Palmeri (former member of the far-right New Force party) has been fighting for the DPR since 2014, and was hailed by DPR leader Gubarev as a «real fascist».[224] Other far-right activists with links to the DPR include French far-right MEP Jean-Luc Schaffhauser, Italian nationalist Alessandro Musolino, German neo-Nazi journalist Manuel Ochsenreiter, and Emmanuel Leroy, a far-right adviser to Marine Le Pen, former leader of the National Rally.[225][226]

Finnish neo-Nazis have been recruited for pro-Russian forces by Johan Bäckman and Janus Putkonen, who are aligned with the local far-right pro-Russian party Power Belongs to the People.[227][228][229][230] Putkonen also runs the Russian-funded DONi (Donbass International News Agency) and MV-media, which publish pro-Russian propaganda about the DPR.[231][232]

Far-left

The DPR has also cultivated relations with various far-left groups. A small number of Spanish socialists travelled to Ukraine to fight for the separatists, with some explaining they were «repaying the favour» to Russia for the USSR’s support to Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.[233] Spanish fighters founded the ‘Carlos Palomino International Brigade’, which flew the flag of the Second Spanish Republic. In 2015, it reportedly had less than ten members, and was later disbanded.[234]

A female member of the Israeli Communist Party also reportedly fought for the separatists in 2015.[235] Other examples of far-left groups fighting for the separatists were the ‘DKO’ (Volunteer Communist Unit) and the Interunit, which has been inactive since 2017.[236][237]

The Italian communist ska punk group Banda Bassotti has also been active in support of the DPR and has organized trips to Donetsk, one of which saw the participation of Eleonora Forenza, a member of the European Parliament for the Communist Refoundation Party.[238] Andrej Hunko, a member of the German parliament for the far-left party Die Linke, also travelled to Donetsk to support the separatists.[239]

Economy

The DPR has its own central bank, the Donetsk Republican Bank. The republic’s economy is frequently described as dependent on contraband and gunrunning,[240] with some labelling it a mafia state. Joining DPR military formations or its civil services has become one of the few guarantees for a stable income in the DPR.[139]

By late October 2014, many banks and other businesses in the DPR were shut, and people were often left without social benefits payments.[172] Sources (who declined to be identified, citing security concerns) inside the DPR administration have told Bloomberg News that Russia transfers 2.5 billion Russian rubles ($37 million) for pensions every month.[241] By mid-February 2016 Russia had sent 48 humanitarian convoys to rebel-held territory that were said to have delivered more than 58,000 tons of cargo including food, medicines, construction materials, diesel generators and fuel and lubricants.[242] President Poroshenko called this a «flagrant violation of international law» and Valentyn Nalyvaychenko said it was a «direct invasion».[243]

Reuters in late October 2014 reported long lines at soup kitchens.[172] In the same month in at least one factory, workers no longer received wages, only food rations.[244]

By June 2015, due to logistical and transport problems, prices in DPR-controlled territory are significantly higher than in territory controlled by Ukraine.[139] This led to an increase of supplies (of more expensive products and those of lower quality) from Russia.[139] Mines and heavy-industry facilities damaged by shelling were forced to close, undermining the wider chain of economic ties in the region.[244] Three industrial facilities were under DPR «temporary management» by late October 2014.[244] By early June 2015, 80% of companies physically located in the Donetsk People’s Republic had re-registered on territory under Ukrainian control.[240]

The new ruling elites of the DPR have displaced the previous oligarchic structures in the region.[245] The new powerholders expropriated profitable businesses. For instance, Rinat Akhmetov lost control over his assets in the region after they were nationalised. Under Russia’s guidance, the republic set up trade and production monopolies through which the trade in coal and steel is organised. Lacking private banks, its own currency, and direct access to the Black Sea, DPR’s survival depends exclusively on Russia’s economic support and trade through the common border.[246]

Marketplace in Donetsk in 2015

A DPR official often promised financial support from Russia without giving specific details.[172] Prime Minister Aleksandr Zakharchenko in late October 2014 stated that «We have the Russian Federation’s agreement in principle on granting us special conditions on gas (deliveries)».[172] Zakharchenko also claimed that «And, finally, we managed to link up with the financial and banking structure of the Russian Federation».[172] When Reuters tried to get more details from a source close to Zakharchenko the only reply was «Money likes silence».[172] Early October 2014 Zakharchenko stated, «The economy will be complete, if possible, oriented towards the Russian market. We consider Russia our strategic partner». According to Zakharchenko this would «secure our economy from impacts from outside, including from Ukraine».[247] According to Yury Makohon, from the Ukrainian National Institute for Strategic Studies, «Trade volume between Russia and Donetsk Oblast has seen a massive slump since the beginning of 2014».[248] Since Russia did not recognise the legal status of the self-proclaimed republic, all the trade it did with it was on the basis of Ukrainian law.[240]

DPR authorities have created a multi-currency zone in which both the rouble (Russia’s currency) and the hryvnia (Ukraine’s currency) can be used, and also the Euro and U.S. Dollar.[139][247] Cash shortages are widespread and, due to a lack of roubles, the hryvnia is the most-used currency.[139] According to Ukraine’s security services in May 2016 alone the Russian government has passed US$19 million in cash to fund the DPR administration as well as 35,000 blank Russian passports.[249]

Since late February 2015, DPR-controlled territories receive their natural gas directly from Russia.[250] According to Russia, Ukraine should pay for these deliveries; Ukraine claims it does not receive payments for the supplies from DPR-controlled territory.[250][251] On 2 July 2015, Ukrainian Energy Minister Volodymyr Demchyshyn announced that he «did not expect» that Ukraine would supply natural gas to territory controlled by separatist troops in the 2015–2016 heating season.[252] Since 25 November 2015 Ukraine has halted all its imports of (and payments for) natural gas from Russia.[253]

Products from the factory in Chystiakove at the trade fair in Donetsk in 2018

The DPR set up its own mobile network operator called Feniks, which was to be fully operational by the end of the summer of 2015.[254] On 5 February 2015, Kyivstar claimed that Feniks illegally used equipment that they officially gave up in territories controlled by pro-Russian separatists.[254] On 18 April 2015, Prime Minister Zakharchenk issued a decree stating that all equipment given up by Kyivstar fell under the control of the separatists in order to «meet the needs of the population in the communication services».[254] The SIM cards of Feniks display the slogan «Connection for the victory».[255]

In June 2015, the DPR authorities announced the start of military pension payments in US dollars.[256]

In mid-March 2017, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a temporary ban on the movement of goods to and from territory controlled by DPR and LPR. Ukraine has not bought coal from the Donets Black Coal Basin since then.[257]

Anthracite mines under DPR control reportedly supply coal to Poland through Russian shell companies to disguise its real origin.[258]

According to Ukrainian and Russian media, the coal export company Vneshtorgservis, owned by Serhiy Kurchenko, owes massive debts to coal mines located in separatist-controlled territory and other local companies.[259]

Sergey Zdrilyuk («Abwehr»), former deputy of DPR militia, stated in an interview in 2020 that large-scale disassembly of mining equipment for scrap metal and other forms of looting took place routinely during Igor Girkin’s time as a militia commander, and that Girkin took significant amounts of money with him to Moscow. Militia groups such as «Vostok» and «Oplot» as well as various «Cossack formations», were involved in looting on systematic basis.[260][261]

Human rights

An early March 2016 United Nations OHCHR report stated that people that lived in separatist-controlled areas were experiencing «complete absence of rule of law, reports of arbitrary detention, torture and incommunicado detention, and no access to real redress mechanisms».[262]

Freedom House evaluates the eastern Donbas territories controlled by the DPR and LPR as «not free», scoring 4 out of 100 in its 2022 Freedom in the World index, noting issues with severe political and media repression, numerous reports of torture, and arbitrary detention.[263] The Guardian noted on 17 February 2022 «Public opposition in the DPR is virtually non-existent.»[246]

War crimes

Protest in Donetsk against OSCE’s inaction in Donbas, 23 October 2021

An 18 November 2014 United Nations report on eastern Ukraine stated that the DPR was in a state of «total breakdown of law and order».[264] The report noted «cases of serious human rights abuses by the armed groups continued to be reported, including torture, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, summary executions, forced labour, sexual violence, as well as the destruction and illegal seizure of property may amount to crimes against humanity».[264] The November report also stated «the HRMMU continued to receive allegations of sexual and gender-based violence in the eastern regions. In one reported incident, members of the pro-Russian Vostok Battalion «arrested» a woman for violating a curfew and beat her with metal sticks for three hours. The woman was also raped by several pro-Russian rebels from the battalion. The report also states that the UN mission «continued to receive reports of torture and ill-treatment by the Ukrainian law enforcement agencies and volunteer battalions and by the (pro-Russian separatist) armed groups, including beating, death threats, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, and lack of access to medical assistance».[265] In a 15 December 2014 press conference in Kyiv, UN Assistant Secretary-General for human rights Ivan Šimonović stated that the majority of human rights violations were committed in areas controlled by pro-Russian rebels.[266]

The United Nations report also accused the Ukrainian Army and Ukrainian (volunteer) territorial defence battalions, including the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion,[267][268] of human rights abuses such as illegal detention, torture and ill-treatment of DPR and LPR supporters, noting official denials.[264][269] Amnesty International reported on 24 December 2014 that pro-government volunteer battalions were blocking Ukrainian aid convoys from entering separatist-controlled territory.[270]

On 24 July, Human Rights Watch accused the pro-Russian fighters of not taking measures to avoid encamping in densely populated civilian areas.»[271][272] It also accused Ukrainian government forces and pro-government volunteer battalions of indiscriminate attacks on civilian areas, stating that «The use of indiscriminate rockets in populated areas violates international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, and may amount to war crimes.»[271][272]

A report by the OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights that was released on 2 March 2015 described media postings and online videos which indicated that the pro-Russian armed groups of the DPR carried out «summary, extrajudicial or arbitrary executions» of captured Ukrainian soldiers. In one incident, corpses of Ukrainian servicemen were found with «their hands tied with white electrical cable» after the pro-Russian rebel groups captured Donetsk International Airport. In January a DPR leader claimed that the rebel forces were detaining up to five «subversives» between the ages of 18 and 35 per day. A number of captured prisoners of war were forced to march in Donetsk while being assaulted by rebel soldiers and onlookers. The report also said that Ukrainian law enforcement agencies had engaged in a «pattern of enforced disappearances, secret detention and ill-treatment» of people suspected of «separatism» and «terrorism».[273] The report also mentions videos of members of one particular pro-Russian unit talking about running a torture facility in the basement of a Luhansk library. The head of the unit in question was the pro-Russian separatist commander Aleksandr Biednov, known as «Batman» (who was later killed) and the «head» of the torture chamber was a rebel called «Maniac» who «allegedly used a hammer to torture prisoners and surgery kit to scare and extract confessions from prisoners».[273][274]

In September 2015, OSCE published a report on the testimonies of victims held in places of illegal detention in Donbas.[275] In December 2015, a team led by Małgorzata Gosiewska published a comprehensive report on war crimes in Donbas.[276]

Allegations of anti-semitism

Alleged members of the Donetsk Republic carrying the flag of the Russian Federation,[277] passed out a leaflet to Jews that informed all Jews over the age of 16 that they would have to report to the Commissioner for Nationalities in the Donetsk Regional Administration building and register their property and religion. It also claimed that Jews would be charged a $50 ‘registration fee’.[278] If they did not comply, they would have their citizenship revoked, face ‘forceful expulsion’ and see their assets confiscated. The leaflet stated the purpose of registration was because «Jewish community of Ukraine supported Bandera Junta,» and «oppose the pro-Slavic People’s Republic of Donetsk».[277] The authenticity of the leaflet could not be independently verified.[279] The New York Times, Haaretz, and The New Republic said the fliers were «most likely a hoax».[280][281][282] France 24 also reported on the questionable authenticity of the leaflets.[283] According to Efraim Zuroff of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the leaflets looked like some sort of provocation, and an attempt to paint the pro-Russian forces as anti-semitic.[284] The chief rabbi of Donetsk Pinchas Vishedski stated that the flyer was a fake meant to discredit the self-proclaimed republic,[285] and saying that anti-Semitic incidents in eastern Ukraine are «rare, unlike in Kiev and western Ukraine»[286] and believes the men were ‘trying to use the Jewish community in Donetsk as an instrument in the conflict;’[287] however, he also called the DPR Press Secretary Aleksander Kriakov «the most famous anti-Semite in the region» and questioned DPR’s decision to appoint him.[288]

Religion

Religion in Donbas (Donetsk + Luhansk) (2016)[289]

Other religions (16.1%)

At first the DPR adopted a constitution which stated that the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was the official religion of the self-declared state.[290][291] This was changed with the promulgation of a law «on freedom of conscience and religious organisation» in November 2015, backed by three deputies professing Rodnovery (Slavic native faith), whose members organised the Svarozhich Battalion (of the Vostok Brigade) and the Rusich Company.[292][293] The new law caused the dissatisfaction of Metropolitan Hilarion of Donetsk and Mariupol of the Moscow Patriarchate church.[294]

Donetsk separatists consider Christian denominations such as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate, Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and wider Roman Catholic Church, and Protestantism, as all being anti-Russian and see them as obstacles in the path of the separatist goal of uniting the region with Russia.[291] To complement this emphasis on Orthodoxy against churches deemed «heretical» and anti-Russian, the separatists have been successful in enlisting the widespread support of many people in Donetsk belonging to the indigenous Greek Orthodox community. These are mainly Pontic Greeks settled in Donetsk and elsewhere in southern Russia and Ukraine since the Middle Ages, and are in the main descendants of refugees from the Pontic Alps, Eastern Anatolia, and the Crimea, dating to the Ottoman conquests of these regions in the late 15th century. There have been widespread media reports of these ethnic Greeks and those with roots in southern Ukraine now living mainly in Northern Greece fighting with Donetsk separatist forces on the justification that their war represents a struggle for Christian Orthodoxy against the forces of what they often describe as «schismatics» and «fascists».[citation needed]

Romani people

Hundreds of Romani families fled Donbas in 2014.[295] The News of Donbas reported that members of the Donbas People’s Militia engaged in assaults and robbery on the Romani (also known as gypsies) population of Sloviansk. The armed separatists beat women and children, looted homes, and carried off the stolen goods in trucks, according to eyewitnesses.[296][better source needed][297][298][299] Romani fled en masse to live with relatives in other parts of the country, fearing ethnic cleansing, displacement and murder. Some men who decided to remain formed militia groups to protect their families and homes.[298] DPR Mayor Ponomarev said the attacks were only against gypsies who were involved in drug trafficking, and that he was ‘cleaning the city from drugs.’[300] The US mission to the OSCE and Ukrainian Prime Minister Yatsenyuk condemned these actions.[296][297][301]

On 8 June 2014, it was reported that armed militants from the Donetsk Republic attacked a gay club in the capital of Donetsk, injuring several. Witnesses said 20 people forced their way into the club, stealing jewellery and other valuables; the assailants fired shots in the club, and several people were hurt.[302] In July 2015, a DPR Ministry of Information spokesperson stated «there are no gays in Donetsk, as they all went to Kyiv».[303] In 2015, the Deputy Minister of Political Affairs of the Donetsk People’s Republic stated: «A culture of homosexuality is spreading … This is why we must kill anyone who is involved in this.»[304]

Prejudice against Ukrainian speakers

On 18 April 2014, Vyacheslav Ponomarev asked local residents of Sloviansk to report all suspicious persons, especially if they were speaking Ukrainian. He also promised that the local media would publish a phone number to report them.[305]

An 18 November 2014 United Nations report on eastern Ukraine stated that the DPR violated the rights of Ukrainian-speaking children because schools in rebel-controlled areas teach only in Russian and forbid pupils to speak Ukrainian.[264] In its May 2014 constitution, the DPR regime declared Russian and Ukrainian its official languages.[77] However, in March 2020, Russian was declared to be the sole official language of the DPR.[156]

Abductions

The Committee to Protect Journalists said that separatists had seized up to ten foreign reporters during the week following the shooting down of the Malaysian aircraft.[306] On 22 July 2014, armed men from the DPR abducted Ukrainian freelance journalist Anton Skiba as he arrived with a CNN crew at a hotel in Donetsk.[306] The DPR often counters such accusations by pointing towards non-governmental organisations, such as Amnesty International’s reporting that pro-Ukrainian volunteer paramilitary battalions, such as the Aidar Battalion, Donbas Battalion, Azov Battalion often acted like «renegade gangs», and were implicated in torture, abductions, and summary executions.[270][307] Amnesty International and the (OHCHR) also raised similar concerns about Radical Party leader and Ukrainian MP Oleh Lyashko and his militia.[308]

Donetsk has also observed significant rise in violent crime (homicide, rape, including underage victims) under the control of separatist forces.[309] In July 2015 local authorities of Druzhkovka, previously occupied by separatist forces, exposed a previous torture site in one of the town’s cellars.[310]

On 2 June 2017 the freelance journalist Stanislav Aseyev was abducted. Firstly the DPR «government» denied knowing his whereabouts but on 16 July, an agent of the DPR’s Ministry of State Security confirmed that Aseyev was in their custody and that he was suspected of espionage. Independent media is not allowed to report from the DPR-controlled territory.[311] Amnesty International, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the European Federation of Journalists, Human Rights Watch, the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, PEN International, Reporters Without Borders and the United States Mission to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe have called for the immediate release of Aseyev.[312][313][314][315][316][317] He was released as part of a prison exchange and handed over to Ukrainian authorities on 29 December 2019.[318]

Sergey Zdrilyuk («Abwehr»), former deputy of DPR militia, confirmed in 2020 that Igor Girkin personally executed prisoners of war he considered «traitors» or «spies».[260][261] This statement was first made in Girkin’s interview earlier that year, although Girkin insisted the executions were part of his «military tribunal based on laws of war». Girkin also confessed that he was involved in the murder of Volodymyr Ivanovych Rybak, a representative of Horlivka who was abducted on 17 April 2014 after trying to raise a Ukrainian flag: «Naturally, Rybak, as a person who actively opposed the «militias», was an enemy in my eyes. And his death, probably, is to some extent also under my responsibility».[319]

Education

Jewish-Russian singer Joseph Kobzon meets with school children in Donetsk, 28 May 2015

By the start of the 2015–2016 school-year DPR’s authorities had overhauled the curriculum.[320] Ukrainian language lessons were decreased from around eight hours a week to two hours; while the time devoted to Russian language and literature lessons were increased.[320] The history classes were changed to give greater emphasis to the history of Donbas.[320] The grading system was changed from (Ukraine’s) 12-point scheme to the five-point grading system that is also used in Russia.[320] According to the director of a college in Donetsk «We give students the choice between the two but the Russian one is taken into greater account».[320] School graduates will receive a Russian certificate, allowing them to enter both local universities and institutions in Russia.[320]

In April 2016 DPR authorities designed «statehood awareness lessons» were introduced in schools (in territory controlled by them).[321]

On 25 September 2017 a new law on education was signed by Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko (draft approved by Verkhovna Rada on 5 September 2017) which says that Ukrainian language is the language of education at all levels.[322]

Culture and sports

A Donetsk People’s Republic national football team has represented the country in international games organised by ConIFA,[323][non-primary source needed] although as of August 2022, it is not listed as a member on the organization’s website.

See also

- List of states with limited recognition

- Malaysia Airlines Flight 17

- Russian occupation of Donetsk Oblast

Notes

- ^ Alleged Russian puppet state[1][2][3]

- ^ The population of the entire Donetsk Oblast in 2019 was estimated to be 4,165,900, while 2,220,500 resided in areas under the control of the Donetsk People’s Republic. Figures are from before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- ^ The group stated they:

1) do not recognise the Ukrainian government;

2) consider themselves the legitimate authority;

3) «dismiss» of all law enforcement officials appointed by the central government and Governor Serhiy Taruta;

4) «appoint» on the 11 May referendum about self-determinat Donetsk;

5) require the extradition of their leader Pavel Gubarev and other already detained separatists;

6) require Ukraine to withdrawal its troops and paramilitary forces;

7) start the process of finding mechanisms of cooperation with the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia (since 2015, the Eurasian Economic Union, also including Armenia and Kyrgyzstan) and other separatist groups (in Kharkiv and Luhansk).[55]

References

- ^ a b Johnson, Jamie; Parekh, Marcus; White, Josh; Vasilyeva, Nataliya (4 August 2022). «Officer who ‘boasted’ of killing civilians becomes Russia’s first female commander to die». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b Bershidsky, Leonid (13 November 2018). «Eastern Ukraine: Why Putin Encouraged Sham Elections in Donbass». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b «Russian Analytical Digest No 214: The Armed Conflict in Eastern Ukraine». css.ethz.ch. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ National Anthem of Donetsk People’s Republic – Славься республика, наша народная (도네츠크 인민 공화국의 국가) (YouTube). Donetsk. 17 November 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ^ «Symbols and Anthem of the Donetsk People’s Republic». DPR Official Website. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ «Institute for the Study of War».

- ^ «Путин: Россия признала ДНР и ЛНР в границах Донецкой и Луганской областей». BBC Russia. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ «Ukraine crisis: Protesters declare Donetsk ‘republic’«. BBC News. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ «Donetsk oblast». Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ^ MATSUZATO, KIMITAKA (2022). «The First Four Years of the Donetsk People’s Republic». The War in Ukraine’s Donbas. Central European University Press. pp. 43–66. doi:10.7829/j.ctv26jp68t.7. ISBN 9789633864203. S2CID 245630627.

This state was born as a result of the extreme polarization of Ukrainian society, has survived the military conflict with its former suzerain (Ukraine), and, at a certain stage of state building, began to enjoy Russia’s support.

- ^ Toal, Gerard (2017). Near Abroad : Putin, the West, and the contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus. New York, NY. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-19-025331-8. OCLC 965543300.

this does not mean that the Kremlin was behind all forms of protest against Euromaidan— this is clearly not the case— or that the Kremlin controlled the actions of all secessionist leaders, also clearly not so. Secessionist leaders and later rebel fighters had their own motivations. Having said that, there is considerable evidence to indicate that Russian state security structures worked in partnership with ostensibly private but functionally extended state networks of influence—oligarchic groups, veteran organizations, nationalist movements, biker gangs, and organized criminal networks— to encourage, support, and sustain separatist rebellion in eastern Ukraine from the very outset.

- ^ «Ukraine’s prosecutor general classifies self-declared Donetsk and Lugansk republics as terrorist organizations». Kyiv Post. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ Владимир Соловьев, Елена Черненко, Ксения Веретенникова (22 February 2022). «У Донбасса собственная гордость» [Donbass has its own pride]. Коммерсантъ (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

After Russian President Vladimir Putin’s speech, Russian state television channels showed him meeting with leaders of the now partially recognized DPR and LPR, Denis Pushilin and Leonid Pasechnik

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adam Potočňák, Miroslav Mares (2022). «Donbas Conflict: How Russia’s Trojan Horse Failed and Forced Moscow to Alter Its Strategy». 0 (0) (Problems of Post-Communism ed.): 1–11. doi:10.1080/10758216.2022.2066005. ISSN 1075-8216. CS1 maint: date and year (link) — «The second option proved to be the one chosen on February 21, 2022, when Russia formally recognized the independence of the DNR and LNR and immediately sent its troops to their territories. This move proved that Moscow had completely abandoned the original Trojan Horse strategy, thus killing the entire Minsk peace process and enacting one of its already „tested“ strategic approaches. Unfortunately, the Russian Federation then went a long way further and launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, sparking the most significant security crisis in Europe since the end of World War II. At the time of completion of this article (first half of April 2022), the war was entering its second phase, with Russian forces concentrating on advances in eastern and southern Ukraine after they failed to conquer Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other population centers. Therefore, it was impossible to draw any more or less probable scenarios for further developments and the future of the two, now partially recognized, people’s republics in Donbas, beyond stating two preliminary conclusions. First, the Trojan Horse strategy was an original but ultimately unsuccessful Russian attempt to approach a specific frozen conflict and the two de facto states by a new, hitherto unknown, strategic approach. Second, the case of Donbas confirmed the presumption by Kopeček and Hoch that any de facto state eventually ends up being reincorporated into its maternal state, being annexed by its patron, or gaining (at least partial) international recognition»

- ^ «Ukraine: UN General Assembly demands Russia reverse course on ‘attempted illegal annexation’«. The United Nations. 12 October 2022.

- ^ a b «Ukraine war: UN General Assembly condemns Russia annexation». BBC News. 13 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Averre, Derek; Wolczuk, Kataryna, eds. (2018). The Ukraine Conflict: Security, Identity and Politics in the Wider Europe. Routledge. pp. 90–91.

Separatist ideologues in the Donbas, such as they are, have therefore produced a strange melange since 2014. Of what Marlène Laruelle (2016) has called the ‘three colours’ of Russian nationalism designed for export—red (Soviet), white (Orthodox) and brown (fascist) … there are arguably more real fascists on the rebel side than the Ukrainian side

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Likhachev, Vyacheslav (July 2016). «The Far Right in the Conflict between Russia and Ukraine» (PDF). Russie.NEI.Visions in English. pp. 18–28. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ «3 convicted in 2014 downing of Malaysian jet over Ukraine». Associated Press. 18 November 2022.

- ^ «Fight For Dignity: Remembering The Ukrainian Revolution». RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (20 April 2016). «The Donbas in 2014: Explaining Civil Conflict Perhaps, but not Civil War». Europe-Asia Studies. 68 (4): 631–652. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1176994. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 148334453.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (22 September 2013). «Ukraine’s EU trade deal will be catastrophic, says Russia». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ Petro, Nicolai N., Understanding the Other Ukraine: Identity and Allegiance in Russophone Ukraine (1 March 2015). Richard Sakwa and Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska, eds., Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, Bristol, United Kingdom: E-International Relations Edited Collections, 2015, pp. 19–35. Available at SSRN 2574762

- ^ «Pro-Russia Protesters Storm Donetsk Offices». NBC News. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ a b Kendall, Bridget (7 April 2014). «Ukraine: Pro-Russians storm offices in Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv». BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ «Pro-Russians fortify barricade of gubernatorial building in Donetsk». Kyiv Post. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014.

- ^ Протестующие в Донецке требуют провести референдум о вхождении в РФ [Protesters in Donetsk want to hold a referendum on joining the Russian Federation] (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b Воскресный штурм ДонОГА в фотографиях. novosti.dn.ua (in Russian). 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b Донецькі сепаратисти готуються сформувати «народну облраду» та приєднатися до РФ [Donetsk separatists are preparing to form a «people’s regional council» and join Russia]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Сепаратисты выставили ультиматум: референдум о вхождении Донецкой области в состав РФ. Donbas News (in Russian). 6 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ «Ukraine crisis: Protesters declare Donetsk ‘republic’«. BBC News. 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Донецька міськрада просить громадян не брати участь у протиправних діях [Donetsk city council asks citizens not to participate in unlawful activities]. NGO.Donetsk.ua (in Ukrainian). 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014.

- ^ «Donetsk City Council urges leaders of protests held in the city to hold talks, lay down arms immediately – statement». Interfax-Ukraine. 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ «Donetsk’s pro-Russian activists prepare referendum for ‘new republic’«. The Guardian. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ «Donetsk separatists hold oblast government headquarters». Kyiv Post. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ «Demonstrators in Donetsk plan to create ‘people’s army’«. Information Telegraph Agency of Russia. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ «Pro-Russian mayor of Slavyansk sacked and arrested Archived 3 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine». The Guardian. 12 June 2014.

- ^ «Pro-Russian Gubarev, a symbol of east Ukraine separatism». GlobalPost. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ ««Donetsk Republic» while there is still and wants the Customs Union». Ukrayinska Pravda. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

require the release of its leader Paul Gubarev and other detained separatists;

- ^ Coynash, Halya (18 March 2014). «Far-Right Recruited as Crimea Poll Observers». Institute for War and Peace Reporting. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

Pavel Gubarev, a former member of the neo-Nazi, Russian chauvinist Russian National Unity movement

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (17 March 2014). «Far-Right Forces are Influencing Russia’s Actions in Crimea». The New Republic. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

In Donetsk Gubarov was known as a neo-Nazi and as a member of the fascist organization Russian National Unity.

- ^ «Russia’s deep ties to Donetsk’s Kremlin collaborators». Kyiv Post. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014.

In Donetsk, Pavel Gubarev, a Ukrainian citizen and former member of the Russian National Unity movement, attempted to head the protest.

- ^ «Kremlin turns a blind eye to the rampant Nazism in the country». TSN. 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

It is worth noting that Gubarev was recently an activist of the Russian radical nationalist organization – Russian National Unity, which is included in the International Union of National Socialists.

- ^ Digital Journal Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Pro-Russian Gubarev, a symbol of east Ukraine separatism, by Germain Moyon, 9 March 2014.

- ^ «Russian Gubarev, a symbol of east Ukraine separatism». Global Post. 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

- ^ «Russian neo-Nazi stabs prominent Jew». the Guardian. 14 July 1999.

- ^ «From The Fringes Toward Mainstream: Russian Nationalist Broadsheet Basks In Ukraine Conflict». RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ^ a b «Regional legislators proclaim industrial center Donetsk People’s Republic». ITAR-TASS. 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ «обращение народа Донбасса к Путину В.В.» Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ «Патриотические силы Донбасса организовались и скоординировались. Манифест». OstroV. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ В Донецке отменили создание Донецкой республики [The creation of the «Donetsk Republic» was cancelled in Donetsk] (in Russian). News.bigmir.net. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ Донецкая республика не продержалась и дня? [Donestk Republic did not last a day?]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Russian). 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ «Решение о создании «Донецкой народной республики» отменено» [Decision to establish a «people’s republic of Donetsk» canceled]. Gazeta.ru. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ «Ukraine forces retake Kharkiv building, pro-Russians hold out elsewhere». Euronews. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014.

- ^ a b ««Donetsk Republic» while there is still and wants the Customs Union». Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ «Pro-Russian terrorists build barricades at Donetsk city hall». BBC News. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ «Граждане России продолжают митинговать в Донецке за отделение Донбасса» [Russian citizens continue to rally in Donetsk Donbas secession]. Novosti Donetsk. 8 March 2014. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ «Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine – Monday, 14 April 2014». Archived from the original on 16 April 2014.

- ^ «Separatists in Donetsk decided to release several floors». Ukrainska Pravda. 22 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Сепаратисты освободили 9 и 10 этажи Донецкой ОГА ФОТОФАКТ [Separatists give up floors 9 and 10 of the Donetsk Regional Administration offices, in pictures]. Novosti Donetsk. 24 April 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014.

- ^ Ostrovsky, Simon (12 April 2014). «Russian Roulette: The Invasion of Ukraine (Dispatch Twenty Three)». VICE News. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

It’s day 2 of the People’s Republic of Donetsk, and it smells like there was a huge frat party here because earlier today they decided to pour all their alcohol out onto the barricades out front because apparently there’s been a problem with a little bit too much drinking inside the building.

- ^ Leonard, Peter (7 May 2014). «Putin: Troops have pulled back from Ukraine border». Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ a b «Баркашов советует «впарить» Донецку итоги референдума». BBC Russian. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014.

- ^ «SBU Audio Links Donetsk Republic to Russian Involvement». Ukrainian Policy. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Babiak, Mat (19 April 2014). «Southeast Statistics». Ukrainian Policy. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.