Not to be confused with Physis.

Physics is the natural science that studies matter,[a] its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force.[2] Physics is one of the most fundamental scientific disciplines, with its main goal being to understand how the universe behaves.[b][3][4][5] A scientist who specializes in the field of physics is called a physicist.

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines and, through its inclusion of astronomy, perhaps the oldest.[6] Over much of the past two millennia, physics, chemistry, biology, and certain branches of mathematics were a part of natural philosophy, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 17th century these natural sciences emerged as unique research endeavors in their own right.[c] Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics and quantum chemistry, and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms studied by other sciences[3] and suggest new avenues of research in these and other academic disciplines such as mathematics and philosophy.

Advances in physics often enable advances in new technologies. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism, solid-state physics, and nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products that have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons;[3] advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.

History

The word «physics» comes from Ancient Greek: φυσική (ἐπιστήμη), romanized: physikḗ (epistḗmē), meaning «knowledge of nature».[8][9][10]

Ancient astronomy

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences. Early civilizations dating back before 3000 BCE, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, and the Indus Valley Civilisation, had a predictive knowledge and a basic awareness of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars. The stars and planets, believed to represent gods, were often worshipped. While the explanations for the observed positions of the stars were often unscientific and lacking in evidence, these early observations laid the foundation for later astronomy, as the stars were found to traverse great circles across the sky,[6] which could not explain the positions of the planets.

According to Asger Aaboe, the origins of Western astronomy can be found in Mesopotamia, and all Western efforts in the exact sciences are descended from late Babylonian astronomy.[11] Egyptian astronomers left monuments showing knowledge of the constellations and the motions of the celestial bodies,[12] while Greek poet Homer wrote of various celestial objects in his Iliad and Odyssey; later Greek astronomers provided names, which are still used today, for most constellations visible from the Northern Hemisphere.[13]

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy has its origins in Greece during the Archaic period (650 BCE – 480 BCE), when pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales rejected non-naturalistic explanations for natural phenomena and proclaimed that every event had a natural cause.[14] They proposed ideas verified by reason and observation, and many of their hypotheses proved successful in experiment;[15] for example, atomism was found to be correct approximately 2000 years after it was proposed by Leucippus and his pupil Democritus.[16]

Medieval European and Islamic

The Western Roman Empire fell in the fifth century, and this resulted in a decline in intellectual pursuits in the western part of Europe. By contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) resisted the attacks from the barbarians, and continued to advance various fields of learning, including physics.[17]

In the sixth century, Isidore of Miletus created an important compilation of Archimedes’ works that are copied in the Archimedes Palimpsest.

Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965–c. 1040), Book of Optics Book I, [6.85], [6.86]. Book II, [3.80] describes his camera obscura experiments.[18]

In sixth-century Europe John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar, questioned Aristotle’s teaching of physics and noted its flaws. He introduced the theory of impetus. Aristotle’s physics was not scrutinized until Philoponus appeared; unlike Aristotle, who based his physics on verbal argument, Philoponus relied on observation. On Aristotle’s physics Philoponus wrote:

But this is completely erroneous, and our view may be corroborated by actual observation more effectively than by any sort of verbal argument. For if you let fall from the same height two weights of which one is many times as heavy as the other, you will see that the ratio of the times required for the motion does not depend on the ratio of the weights, but that the difference in time is a very small one. And so, if the difference in the weights is not considerable, that is, of one is, let us say, double the other, there will be no difference, or else an imperceptible difference, in time, though the difference in weight is by no means negligible, with one body weighing twice as much as the other[19]

Philoponus’ criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics served as an inspiration for Galileo Galilei ten centuries later,[20] during the Scientific Revolution. Galileo cited Philoponus substantially in his works when arguing that Aristotelian physics was flawed.[21][22] In the 1300s Jean Buridan, a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris, developed the concept of impetus. It was a step toward the modern ideas of inertia and momentum.[23]

Islamic scholarship inherited Aristotelian physics from the Greeks and during the Islamic Golden Age developed it further, especially placing emphasis on observation and a priori reasoning, developing early forms of the scientific method.

Although Aristotle’s principles of physics was criticized, it is important to identify his the evidence he based his views off of. When thinking of the history of science and math, it is notable to acknowledge the contributions made by older scientists. Aristotle’s science was the backbone of the science we learn in schools today. Aristotle published many biological works including The Parts of Animals, in which he discusses both biological science and natural science as well. It is also integral to mention the role Aristotle had in the progression of physics and metaphysics and how his beliefs and findings are still being taught in science classes to this day. The explanations that Aristotle gives for his findings are also very simple. When thinking of the elements, Aristotle believed that each element (earth, fire, water, air) had its own natural place. Meaning that because of the density of these elements, they will revert back to their own specific place in the atmosphere.[24] So, because of their weights, fire would be at the very top, air right underneath fire, then water, then lastly earth. He also stated that when a small amount of one element enters the natural place of another, the less abundant element will automatically go into its own natural place. For example, if there is a fire on the ground, if you pay attention, the flames go straight up into the air as an attempt to go back into its natural place where it belongs. Aristotle called his metaphysics “first philosophy” and characterized it as the study of “being as being”.[25] Aristotle defined the paradigm of motion as a being or entity encompassing different areas in the same body. [25]Meaning that if a person is at a certain location (A) they can move to a new location (B) and still take up the same amount of space. This is involved with Aristotle’s belief that motion is a continuum. In terms of matter, Aristotle believed that the change in category (ex. place) and quality (ex. color) of an object is defined as “alteration”. But, a change in substance is a change in matter. This is also very close to our idea of matter today.

He also devised his own laws of motion that include 1) heavier objects will fall faster, the speed being proportional to the weight and 2) the speed of the object that is falling depends inversely on the density object it is falling through (ex. density of air).[26] He also stated that, when it comes to violent motion (motion of an object when a force is applied to it by a second object) that the speed that object moves, will only be as fast or strong as the measure of force applied to it.[26] This is also seen in the rules of velocity and force that is taught in physics classes today. These rules are not necessarily what we see in our physics today but, they are very similar. It is evident that these rules were the backbone for other scientists to come revise and edit his beliefs.

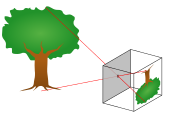

The basic way a pinhole camera works

The most notable innovations were in the field of optics and vision, which came from the works of many scientists like Ibn Sahl, Al-Kindi, Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Farisi and Avicenna. The most notable work was The Book of Optics (also known as Kitāb al-Manāẓir), written by Ibn al-Haytham, in which he conclusively disproved the ancient Greek idea about vision and came up with a new theory. In the book, he presented a study of the phenomenon of the camera obscura (his thousand-year-old version of the pinhole camera) and delved further into the way the eye itself works. Using dissections and the knowledge of previous scholars, he was able to begin to explain how light enters the eye. He asserted that the light ray is focused, but the actual explanation of how light projected to the back of the eye had to wait until 1604. His Treatise on Light explained the camera obscura, hundreds of years before the modern development of photography.[27]

The seven-volume Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manathir) hugely influenced thinking across disciplines from the theory of visual perception to the nature of perspective in medieval art, in both the East and the West, for more than 600 years. Many later European scholars and fellow polymaths, from Robert Grosseteste and Leonardo da Vinci to René Descartes, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, were in his debt. Indeed, the influence of Ibn al-Haytham’s Optics ranks alongside that of Newton’s work of the same title, published 700 years later.

The translation of The Book of Optics had a huge impact on Europe. From it, later European scholars were able to build devices that replicated those Ibn al-Haytham had built and understand the way light works. From this, important inventions such as eyeglasses, magnifying glasses, telescopes, and cameras were developed.

Classical

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) showed a modern appreciation for the proper relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics.

Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.[28][page needed]

Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo’s pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th Centuries, and Isaac Newton’s discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name).[29] Newton also developed calculus,[d] the mathematical study of continuous change, which provided new mathematical methods for solving physical problems.[30]

The discovery of new laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and electromagnetics resulted from research efforts during the Industrial Revolution as energy needs increased.[31] The laws comprising classical physics remain very widely used for objects on everyday scales travelling at non-relativistic speeds, since they provide a very close approximation in such situations, and theories such as quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity simplify to their classical equivalents at such scales. Inaccuracies in classical mechanics for very small objects and very high velocities led to the development of modern physics in the 20th century.

Modern

Modern physics began in the early 20th century with the work of Max Planck in quantum theory and Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Both of these theories came about due to inaccuracies in classical mechanics in certain situations. Classical mechanics predicted that the speed of light depends on the motion of the observer, which could not be resolved with the constant speed predicted by Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism. This discrepancy was corrected by Einstein’s theory of special relativity, which replaced classical mechanics for fast-moving bodies and allowed for a constant speed of light.[32] Black-body radiation provided another problem for classical physics, which was corrected when Planck proposed that the excitation of material oscillators is possible only in discrete steps proportional to their frequency. This, along with the photoelectric effect and a complete theory predicting discrete energy levels of electron orbitals, led to the theory of quantum mechanics improving on classical physics at very small scales.[33]

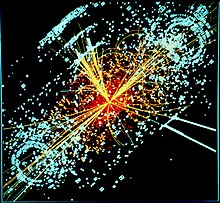

Quantum mechanics would come to be pioneered by Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger and Paul Dirac.[33] From this early work, and work in related fields, the Standard Model of particle physics was derived.[34] Following the discovery of a particle with properties consistent with the Higgs boson at CERN in 2012,[35] all fundamental particles predicted by the standard model, and no others, appear to exist; however, physics beyond the Standard Model, with theories such as supersymmetry, is an active area of research.[36] Areas of mathematics in general are important to this field, such as the study of probabilities and groups.

Philosophy

In many ways, physics stems from ancient Greek philosophy. From Thales’ first attempt to characterize matter, to Democritus’ deduction that matter ought to reduce to an invariant state the Ptolemaic astronomy of a crystalline firmament, and Aristotle’s book Physics (an early book on physics, which attempted to analyze and define motion from a philosophical point of view), various Greek philosophers advanced their own theories of nature. Physics was known as natural philosophy until the late 18th century.[e]

By the 19th century, physics was realized as a discipline distinct from philosophy and the other sciences. Physics, as with the rest of science, relies on philosophy of science and its «scientific method» to advance our knowledge of the physical world.[38] The scientific method employs a priori reasoning as well as a posteriori reasoning and the use of Bayesian inference to measure the validity of a given theory.[39]

The development of physics has answered many questions of early philosophers but has also raised new questions. Study of the philosophical issues surrounding physics, the philosophy of physics, involves issues such as the nature of space and time, determinism, and metaphysical outlooks such as empiricism, naturalism and realism.[40]

Many physicists have written about the philosophical implications of their work, for instance Laplace, who championed causal determinism,[41] and Erwin Schrödinger, who wrote on quantum mechanics.[42][43] The mathematical physicist Roger Penrose has been called a Platonist by Stephen Hawking,[44] a view Penrose discusses in his book, The Road to Reality.[45] Hawking referred to himself as an «unashamed reductionist» and took issue with Penrose’s views.[46]

Core theories

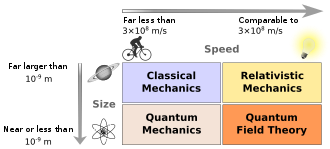

Though physics deals with a wide variety of systems, certain theories are used by all physicists. Each of these theories was experimentally tested numerous times and found to be an adequate approximation of nature. For instance, the theory of classical mechanics accurately describes the motion of objects, provided they are much larger than atoms and moving at a speed much less than the speed of light. These theories continue to be areas of active research today. Chaos theory, a remarkable aspect of classical mechanics, was discovered in the 20th century, three centuries after the original formulation of classical mechanics by Newton (1642–1727).

These central theories are important tools for research into more specialized topics, and any physicist, regardless of their specialization, is expected to be literate in them. These include classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, electromagnetism, and special relativity.

Classical

Classical physics includes the traditional branches and topics that were recognized and well-developed before the beginning of the 20th century—classical mechanics, acoustics, optics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism. Classical mechanics is concerned with bodies acted on by forces and bodies in motion and may be divided into statics (study of the forces on a body or bodies not subject to an acceleration), kinematics (study of motion without regard to its causes), and dynamics (study of motion and the forces that affect it); mechanics may also be divided into solid mechanics and fluid mechanics (known together as continuum mechanics), the latter include such branches as hydrostatics, hydrodynamics, aerodynamics, and pneumatics. Acoustics is the study of how sound is produced, controlled, transmitted and received.[47] Important modern branches of acoustics include ultrasonics, the study of sound waves of very high frequency beyond the range of human hearing; bioacoustics, the physics of animal calls and hearing,[48] and electroacoustics, the manipulation of audible sound waves using electronics.[49]

Optics, the study of light, is concerned not only with visible light but also with infrared and ultraviolet radiation, which exhibit all of the phenomena of visible light except visibility, e.g., reflection, refraction, interference, diffraction, dispersion, and polarization of light. Heat is a form of energy, the internal energy possessed by the particles of which a substance is composed; thermodynamics deals with the relationships between heat and other forms of energy. Electricity and magnetism have been studied as a single branch of physics since the intimate connection between them was discovered in the early 19th century; an electric current gives rise to a magnetic field, and a changing magnetic field induces an electric current. Electrostatics deals with electric charges at rest, electrodynamics with moving charges, and magnetostatics with magnetic poles at rest.

Modern

Classical physics is generally concerned with matter and energy on the normal scale of observation, while much of modern physics is concerned with the behavior of matter and energy under extreme conditions or on a very large or very small scale. For example, atomic and nuclear physics study matter on the smallest scale at which chemical elements can be identified. The physics of elementary particles is on an even smaller scale since it is concerned with the most basic units of matter; this branch of physics is also known as high-energy physics because of the extremely high energies necessary to produce many types of particles in particle accelerators. On this scale, ordinary, commonsensical notions of space, time, matter, and energy are no longer valid.[50]

The two chief theories of modern physics present a different picture of the concepts of space, time, and matter from that presented by classical physics. Classical mechanics approximates nature as continuous, while quantum theory is concerned with the discrete nature of many phenomena at the atomic and subatomic level and with the complementary aspects of particles and waves in the description of such phenomena. The theory of relativity is concerned with the description of phenomena that take place in a frame of reference that is in motion with respect to an observer; the special theory of relativity is concerned with motion in the absence of gravitational fields and the general theory of relativity with motion and its connection with gravitation. Both quantum theory and the theory of relativity find applications in many areas of modern physics.[51]

Fundamental concepts in modern physics

- Causality

- Covariance

- Action

- Physical field

- Symmetry

- Physical interaction

- Statistical ensemble

- Quantum

- Wave

- Particle

Difference

The basic domains of physics

While physics aims to discover universal laws, its theories lie in explicit domains of applicability.

Loosely speaking, the laws of classical physics accurately describe systems whose important length scales are greater than the atomic scale and whose motions are much slower than the speed of light. Outside of this domain, observations do not match predictions provided by classical mechanics. Einstein contributed the framework of special relativity, which replaced notions of absolute time and space with spacetime and allowed an accurate description of systems whose components have speeds approaching the speed of light. Planck, Schrödinger, and others introduced quantum mechanics, a probabilistic notion of particles and interactions that allowed an accurate description of atomic and subatomic scales. Later, quantum field theory unified quantum mechanics and special relativity. General relativity allowed for a dynamical, curved spacetime, with which highly massive systems and the large-scale structure of the universe can be well-described. General relativity has not yet been unified with the other fundamental descriptions; several candidate theories of quantum gravity are being developed.

Relation to other fields

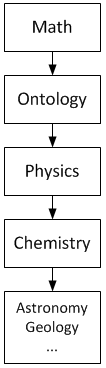

Mathematics and ontology are used in physics. Physics is used in chemistry and cosmology.

Prerequisites

Mathematics provides a compact and exact language used to describe the order in nature. This was noted and advocated by Pythagoras,[52] Plato,[53] Galileo,[54] and Newton.

Physics uses mathematics[55] to organise and formulate experimental results. From those results, precise or estimated solutions are obtained, or quantitative results, from which new predictions can be made and experimentally confirmed or negated. The results from physics experiments are numerical data, with their units of measure and estimates of the errors in the measurements. Technologies based on mathematics, like computation have made computational physics an active area of research.

The distinction between mathematics and physics is clear-cut, but not always obvious, especially in mathematical physics.

Ontology is a prerequisite for physics, but not for mathematics. It means physics is ultimately concerned with descriptions of the real world, while mathematics is concerned with abstract patterns, even beyond the real world. Thus physics statements are synthetic, while mathematical statements are analytic. Mathematics contains hypotheses, while physics contains theories. Mathematics statements have to be only logically true, while predictions of physics statements must match observed and experimental data.

The distinction is clear-cut, but not always obvious. For example, mathematical physics is the application of mathematics in physics. Its methods are mathematical, but its subject is physical.[56] The problems in this field start with a «mathematical model of a physical situation» (system) and a «mathematical description of a physical law» that will be applied to that system. Every mathematical statement used for solving has a hard-to-find physical meaning. The final mathematical solution has an easier-to-find meaning, because it is what the solver is looking for.[clarification needed]

Pure physics is a branch of fundamental science (also called basic science). Physics is also called «the fundamental science» because all branches of natural science like chemistry, astronomy, geology, and biology are constrained by laws of physics.[57] Similarly, chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in linking the physical sciences. For example, chemistry studies properties, structures, and reactions of matter (chemistry’s focus on the molecular and atomic scale distinguishes it from physics). Structures are formed because particles exert electrical forces on each other, properties include physical characteristics of given substances, and reactions are bound by laws of physics, like conservation of energy, mass, and charge. Physics is applied in industries like engineering and medicine.

Application and influence

Classical physics implemented in an acoustic engineering model of sound reflecting from an acoustic diffuser

Applied physics is a general term for physics research, which is intended for a particular use. An applied physics curriculum usually contains a few classes in an applied discipline, like geology or electrical engineering. It usually differs from engineering in that an applied physicist may not be designing something in particular, but rather is using physics or conducting physics research with the aim of developing new technologies or solving a problem.

The approach is similar to that of applied mathematics. Applied physicists use physics in scientific research. For instance, people working on accelerator physics might seek to build better particle detectors for research in theoretical physics.

Physics is used heavily in engineering. For example, statics, a subfield of mechanics, is used in the building of bridges and other static structures. The understanding and use of acoustics results in sound control and better concert halls; similarly, the use of optics creates better optical devices. An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.

With the standard consensus that the laws of physics are universal and do not change with time, physics can be used to study things that would ordinarily be mired in uncertainty. For example, in the study of the origin of the earth, one can reasonably model earth’s mass, temperature, and rate of rotation, as a function of time allowing one to extrapolate forward or backward in time and so predict future or prior events. It also allows for simulations in engineering that drastically speed up the development of a new technology.

But there is also considerable interdisciplinarity, so many other important fields are influenced by physics (e.g., the fields of econophysics and sociophysics).

Research

Scientific method

Physicists use the scientific method to test the validity of a physical theory. By using a methodical approach to compare the implications of a theory with the conclusions drawn from its related experiments and observations, physicists are better able to test the validity of a theory in a logical, unbiased, and repeatable way. To that end, experiments are performed and observations are made in order to determine the validity or invalidity of the theory.[58]

A scientific law is a concise verbal or mathematical statement of a relation that expresses a fundamental principle of some theory, such as Newton’s law of universal gravitation.[59]

Theory and experiment

Theorists seek to develop mathematical models that both agree with existing experiments and successfully predict future experimental results, while experimentalists devise and perform experiments to test theoretical predictions and explore new phenomena. Although theory and experiment are developed separately, they strongly affect and depend upon each other. Progress in physics frequently comes about when experimental results defy explanation by existing theories, prompting intense focus on applicable modelling, and when new theories generate experimentally testable predictions, which inspire the development of new experiments (and often related equipment).[60]

Physicists who work at the interplay of theory and experiment are called phenomenologists, who study complex phenomena observed in experiment and work to relate them to a fundamental theory.[61]

Theoretical physics has historically taken inspiration from philosophy; electromagnetism was unified this way.[f] Beyond the known universe, the field of theoretical physics also deals with hypothetical issues,[g] such as parallel universes, a multiverse, and higher dimensions. Theorists invoke these ideas in hopes of solving particular problems with existing theories; they then explore the consequences of these ideas and work toward making testable predictions.

Experimental physics expands, and is expanded by, engineering and technology. Experimental physicists who are involved in basic research design and perform experiments with equipment such as particle accelerators and lasers, whereas those involved in applied research often work in industry, developing technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transistors. Feynman has noted that experimentalists may seek areas that have not been explored well by theorists.[62]

Scope and aims

Physics involves modeling the natural world with theory, usually quantitative. Here, the path of a particle is modeled with the mathematics of calculus to explain its behavior: the purview of the branch of physics known as mechanics.

Physics covers a wide range of phenomena, from elementary particles (such as quarks, neutrinos, and electrons) to the largest superclusters of galaxies. Included in these phenomena are the most basic objects composing all other things. Therefore, physics is sometimes called the «fundamental science».[57] Physics aims to describe the various phenomena that occur in nature in terms of simpler phenomena. Thus, physics aims to both connect the things observable to humans to root causes, and then connect these causes together.

For example, the ancient Chinese observed that certain rocks (lodestone and magnetite) were attracted to one another by an invisible force. This effect was later called magnetism, which was first rigorously studied in the 17th century. But even before the Chinese discovered magnetism, the ancient Greeks knew of other objects such as amber, that when rubbed with fur would cause a similar invisible attraction between the two.[63] This was also first studied rigorously in the 17th century and came to be called electricity. Thus, physics had come to understand two observations of nature in terms of some root cause (electricity and magnetism). However, further work in the 19th century revealed that these two forces were just two different aspects of one force—electromagnetism. This process of «unifying» forces continues today, and electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are now considered to be two aspects of the electroweak interaction. Physics hopes to find an ultimate reason (theory of everything) for why nature is as it is (see section Current research below for more information).[64]

Research fields

Contemporary research in physics can be broadly divided into nuclear and particle physics; condensed matter physics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; astrophysics; and applied physics. Some physics departments also support physics education research and physics outreach.[65]

Since the 20th century, the individual fields of physics have become increasingly specialised, and today most physicists work in a single field for their entire careers. «Universalists» such as Einstein (1879–1955) and Lev Landau (1908–1968), who worked in multiple fields of physics, are now very rare.[h]

The major fields of physics, along with their subfields and the theories and concepts they employ, are shown in the following table.

| Field | Subfields | Major theories | Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear and particle physics | Nuclear physics, Nuclear astrophysics, Particle physics, Astroparticle physics, Particle physics phenomenology | Standard Model, Quantum field theory, Quantum electrodynamics, Quantum chromodynamics, Electroweak theory, Effective field theory, Lattice field theory, Gauge theory, Supersymmetry, Grand Unified Theory, Superstring theory, M-theory, AdS/CFT correspondence | Fundamental interaction (gravitational, electromagnetic, weak, strong), Elementary particle, Spin, Antimatter, Spontaneous symmetry breaking, Neutrino oscillation, Seesaw mechanism, Brane, String, Quantum gravity, Theory of everything, Vacuum energy |

| Atomic, molecular, and optical physics | Atomic physics, Molecular physics, Atomic and molecular astrophysics, Chemical physics, Optics, Photonics | Quantum optics, Quantum chemistry, Quantum information science | Photon, Atom, Molecule, Diffraction, Electromagnetic radiation, Laser, Polarization (waves), Spectral line, Casimir effect |

| Condensed matter physics | Solid-state physics, High-pressure physics, Low-temperature physics, Surface physics, Nanoscale and mesoscopic physics, Polymer physics | BCS theory, Bloch’s theorem, Density functional theory, Fermi gas, Fermi liquid theory, Many-body theory, Statistical mechanics | Phases (gas, liquid, solid), Bose–Einstein condensate, Electrical conduction, Phonon, Magnetism, Self-organization, Semiconductor, superconductor, superfluidity, Spin, |

| Astrophysics | Astronomy, Astrometry, Cosmology, Gravitation physics, High-energy astrophysics, Planetary astrophysics, Plasma physics, Solar physics, Space physics, Stellar astrophysics | Big Bang, Cosmic inflation, General relativity, Newton’s law of universal gravitation, Lambda-CDM model, Magnetohydrodynamics | Black hole, Cosmic background radiation, Cosmic string, Cosmos, Dark energy, Dark matter, Galaxy, Gravity, Gravitational radiation, Gravitational singularity, Planet, Solar System, Star, Supernova, Universe |

| Applied physics | Accelerator physics, Acoustics, Agrophysics, Atmospheric physics, Biophysics, Chemical physics, Communication physics, Econophysics, Engineering physics, Fluid dynamics, Geophysics, Laser physics, Materials physics, Medical physics, Nanotechnology, Optics, Optoelectronics, Photonics, Photovoltaics, Physical chemistry, Physical oceanography, Physics of computation, Plasma physics, Solid-state devices, Quantum chemistry, Quantum electronics, Quantum information science, Vehicle dynamics |

Nuclear and particle

Particle physics is the study of the elementary constituents of matter and energy and the interactions between them.[66] In addition, particle physicists design and develop the high-energy accelerators,[67] detectors,[68] and computer programs[69] necessary for this research. The field is also called «high-energy physics» because many elementary particles do not occur naturally but are created only during high-energy collisions of other particles.[70]

Currently, the interactions of elementary particles and fields are described by the Standard Model.[71] The model accounts for the 12 known particles of matter (quarks and leptons) that interact via the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental forces.[71] Dynamics are described in terms of matter particles exchanging gauge bosons (gluons, W and Z bosons, and photons, respectively).[72] The Standard Model also predicts a particle known as the Higgs boson.[71] In July 2012 CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, announced the detection of a particle consistent with the Higgs boson,[73] an integral part of the Higgs mechanism.

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies the constituents and interactions of atomic nuclei. The most commonly known applications of nuclear physics are nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons technology, but the research has provided application in many fields, including those in nuclear medicine and magnetic resonance imaging, ion implantation in materials engineering, and radiocarbon dating in geology and archaeology.

Atomic, molecular, and optical

Atomic, molecular, and optical physics (AMO) is the study of matter–matter and light–matter interactions on the scale of single atoms and molecules. The three areas are grouped together because of their interrelationships, the similarity of methods used, and the commonality of their relevant energy scales. All three areas include both classical, semi-classical and quantum treatments; they can treat their subject from a microscopic view (in contrast to a macroscopic view).

Atomic physics studies the electron shells of atoms. Current research focuses on activities in quantum control, cooling and trapping of atoms and ions,[74][75][76] low-temperature collision dynamics and the effects of electron correlation on structure and dynamics. Atomic physics is influenced by the nucleus (see hyperfine splitting), but intra-nuclear phenomena such as fission and fusion are considered part of nuclear physics.

Molecular physics focuses on multi-atomic structures and their internal and external interactions with matter and light. Optical physics is distinct from optics in that it tends to focus not on the control of classical light fields by macroscopic objects but on the fundamental properties of optical fields and their interactions with matter in the microscopic realm.

Condensed matter

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic physical properties of matter.[77][78] In particular, it is concerned with the «condensed» phases that appear whenever the number of particles in a system is extremely large and the interactions between them are strong.[79]

The most familiar examples of condensed phases are solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms.[80] More exotic condensed phases include the superfluid[81] and the Bose–Einstein condensate[82] found in certain atomic systems at very low temperature, the superconducting phase exhibited by conduction electrons in certain materials,[83] and the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic phases of spins on atomic lattices.[84]

Condensed matter physics is the largest field of contemporary physics. Historically, condensed matter physics grew out of solid-state physics, which is now considered one of its main subfields.[85] The term condensed matter physics was apparently coined by Philip Anderson when he renamed his research group—previously solid-state theory—in 1967.[86] In 1978, the Division of Solid State Physics of the American Physical Society was renamed as the Division of Condensed Matter Physics.[85] Condensed matter physics has a large overlap with chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and engineering.[79]

Astrophysics

Astrophysics and astronomy are the application of the theories and methods of physics to the study of stellar structure, stellar evolution, the origin of the Solar System, and related problems of cosmology. Because astrophysics is a broad subject, astrophysicists typically apply many disciplines of physics, including mechanics, electromagnetism, statistical mechanics, thermodynamics, quantum mechanics, relativity, nuclear and particle physics, and atomic and molecular physics.[87]

The discovery by Karl Jansky in 1931 that radio signals were emitted by celestial bodies initiated the science of radio astronomy. Most recently, the frontiers of astronomy have been expanded by space exploration. Perturbations and interference from the earth’s atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared, ultraviolet, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.

Physical cosmology is the study of the formation and evolution of the universe on its largest scales. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity plays a central role in all modern cosmological theories. In the early 20th century, Hubble’s discovery that the universe is expanding, as shown by the Hubble diagram, prompted rival explanations known as the steady state universe and the Big Bang.

The Big Bang was confirmed by the success of Big Bang nucleosynthesis and the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964. The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein’s general relativity and the cosmological principle. Cosmologists have recently established the ΛCDM model of the evolution of the universe, which includes cosmic inflation, dark energy, and dark matter.

Numerous possibilities and discoveries are anticipated to emerge from new data from the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope over the upcoming decade and vastly revise or clarify existing models of the universe.[88][89] In particular, the potential for a tremendous discovery surrounding dark matter is possible over the next several years.[90] Fermi will search for evidence that dark matter is composed of weakly interacting massive particles, complementing similar experiments with the Large Hadron Collider and other underground detectors.

IBEX is already yielding new astrophysical discoveries: «No one knows what is creating the ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon» along the termination shock of the solar wind, «but everyone agrees that it means the textbook picture of the heliosphere—in which the Solar System’s enveloping pocket filled with the solar wind’s charged particles is plowing through the onrushing ‘galactic wind’ of the interstellar medium in the shape of a comet—is wrong.»[91]

Current research

Research in physics is continually progressing on a large number of fronts.

In condensed matter physics, an important unsolved theoretical problem is that of high-temperature superconductivity.[92] Many condensed matter experiments are aiming to fabricate workable spintronics and quantum computers.[79][93]

In particle physics, the first pieces of experimental evidence for physics beyond the Standard Model have begun to appear. Foremost among these are indications that neutrinos have non-zero mass. These experimental results appear to have solved the long-standing solar neutrino problem, and the physics of massive neutrinos remains an area of active theoretical and experimental research. The Large Hadron Collider has already found the Higgs boson, but future research aims to prove or disprove the supersymmetry, which extends the Standard Model of particle physics. Research on the nature of the major mysteries of dark matter and dark energy is also currently ongoing.[94]

Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complexity,[95] chaos,[96] or turbulence[97] are still poorly understood. Complex problems that seem like they could be solved by a clever application of dynamics and mechanics remain unsolved; examples include the formation of sandpiles, nodes in trickling water, the shape of water droplets, mechanisms of surface tension catastrophes, and self-sorting in shaken heterogeneous collections.[i][98]

These complex phenomena have received growing attention since the 1970s for several reasons, including the availability of modern mathematical methods and computers, which enabled complex systems to be modeled in new ways. Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems. In the 1932 Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, Horace Lamb said:[99]

I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment. One is quantum electrodynamics, and the other is the turbulent motion of fluids. And about the former I am rather optimistic.

See also

- List of important publications in physics

- List of physicists

- Lists of physics equations

- Relationship between mathematics and physics

- Earth science

- Neurophysics

- Psychophysics

- Science tourism

Notes

- ^ At the start of The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Richard Feynman offers the atomic hypothesis as the single most prolific scientific concept.[1]

- ^ The term «universe» is defined as everything that physically exists: the entirety of space and time, all forms of matter, energy and momentum, and the physical laws and constants that govern them. However, the term «universe» may also be used in slightly different contextual senses, denoting concepts such as the cosmos or the philosophical world.

- ^ Francis Bacon’s 1620 Novum Organum was critical in the development of scientific method.[7]

- ^ Calculus was independently developed at around the same time by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz; while Leibniz was the first to publish his work and develop much of the notation used for calculus today, Newton was the first to develop calculus and apply it to physical problems. See also Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy

- ^ Noll notes that some universities still use this title.[37]

- ^ See, for example, the influence of Kant and Ritter on Ørsted.

- ^ Concepts which are denoted hypothetical can change with time. For example, the atom of nineteenth-century physics was denigrated by some, including Ernst Mach’s critique of Ludwig Boltzmann’s formulation of statistical mechanics. By the end of World War II, the atom was no longer deemed hypothetical.

- ^ Yet, universalism is encouraged in the culture of physics. For example, the World Wide Web, which was innovated at CERN by Tim Berners-Lee, was created in service to the computer infrastructure of CERN, and was/is intended for use by physicists worldwide. The same might be said for arXiv.org

- ^ See the work of Ilya Prigogine, on ‘systems far from equilibrium’, and others.

References

- ^ Feynman, Leighton & Sands 1963, p. I-2 «If, in some cataclysm, all [] scientific knowledge were to be destroyed [save] one sentence […] what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? I believe it is […] that all things are made up of atoms – little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another …»

- ^ Maxwell 1878, p. 9 «Physical science is that department of knowledge which relates to the order of nature, or, in other words, to the regular succession of events.»

- ^ a b c Young & Freedman 2014, p. 1 «Physics is one of the most fundamental of the sciences. Scientists of all disciplines use the ideas of physics, including chemists who study the structure of molecules, paleontologists who try to reconstruct how dinosaurs walked, and climatologists who study how human activities affect the atmosphere and oceans. Physics is also the foundation of all engineering and technology. No engineer could design a flat-screen TV, an interplanetary spacecraft, or even a better mousetrap without first understanding the basic laws of physics. (…) You will come to see physics as a towering achievement of the human intellect in its quest to understand our world and ourselves.»

- ^ Young & Freedman 2014, p. 2 «Physics is an experimental science. Physicists observe the phenomena of nature and try to find patterns that relate these phenomena.»

- ^ Holzner 2006, p. 7 «Physics is the study of your world and the world and universe around you.»

- ^ a b Krupp 2003

- ^ Cajori 1917, pp. 48–49

- ^ «physics». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ «physic». Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ φύσις, φυσική, ἐπιστήμη. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ Aaboe 1991

- ^ Clagett 1995

- ^ Thurston 1994

- ^ Singer 2008, p. 35

- ^ Lloyd 1970, pp. 108–109

- ^

Gill, N.S. «Atomism – Pre-Socratic Philosophy of Atomism». About Education. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014. - ^ Lindberg 1992, p. 363.

- ^ Smith 2001, Book I [6.85], [6.86], p. 379; Book II, [3.80], p. 453.

- ^ «John Philoponus, Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics». Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Galileo (1638). Two New Sciences.

in order to better understand just how conclusive Aristotle’s demonstration is, we may, in my opinion, deny both of his assumptions. And as to the first, I greatly doubt that Aristotle ever tested by experiment whether it be true that two stones, one weighing ten times as much as the other, if allowed to fall, at the same instant, from a height of, say, 100 cubits, would so differ in speed that when the heavier had reached the ground, the other would not have fallen more than 10 cubits.

Simp. — His language would seem to indicate that he had tried the experiment, because he says: We see the heavier; now the word see shows that he had made the experiment.

Sagr. — But I, Simplicio, who have made the test can assure[107] you that a cannon ball weighing one or two hundred pounds, or even more, will not reach the ground by as much as a span ahead of a musket ball weighing only half a pound, provided both are dropped from a height of 200 cubits. - ^ Lindberg 1992, p. 162.

- ^ «John Philoponus». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ «John Buridan». The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2018. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ tbcaldwe. «Natural Philosophy: Aristotle | Physics 139». Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ a b «Aristotle — Physics and metaphysics | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ a b «Aristotle». galileoandeinstein.phys.virginia.edu. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Howard & Rogers 1995, pp. 6–7

- ^ Ben-Chaim 2004

- ^ Guicciardini 1999

- ^ Allen 1997

- ^ «The Industrial Revolution». Schoolscience.org, Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ O’Connor & Robertson 1996a

- ^ a b O’Connor & Robertson 1996b

- ^ «The Standard Model». DONUT. Fermilab. 29 June 2001. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Cho 2012

- ^ Womersley, J. (February 2005). «Beyond the Standard Model» (PDF). Symmetry. Vol. 2, no. 1. pp. 22–25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Noll, Walter (23 June 2006). «On the Past and Future of Natural Philosophy» (PDF). Journal of Elasticity. 84 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10659-006-9068-y. S2CID 121957320. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 April 2016.

- ^ Rosenberg 2006, Chapter 1

- ^ Godfrey-Smith 2003, Chapter 14: «Bayesianism and Modern Theories of Evidence»

- ^ Godfrey-Smith 2003, Chapter 15: «Empiricism, Naturalism, and Scientific Realism?»

- ^ Laplace 1951

- ^ Schrödinger 1983

- ^ Schrödinger 1995

- ^ Hawking & Penrose 1996, p. 4 «I think that Roger is a Platonist at heart but he must answer for himself.»

- ^ Penrose 2004

- ^ Penrose et al. 1997

- ^ «acoustics». Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ «Bioacoustics – the International Journal of Animal Sound and its Recording». Taylor & Francis. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ «Acoustics and You (A Career in Acoustics?)». Acoustical Society of America. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Tipler & Llewellyn 2003, pp. 269, 477, 561

- ^ Tipler & Llewellyn 2003, pp. 1–4, 115, 185–187

- ^ Dijksterhuis 1986

- ^ Mastin 2010 «Although usually remembered today as a philosopher, Plato was also one of ancient Greece’s most important patrons of mathematics. Inspired by Pythagoras, he founded his Academy in Athens in 387 BC, where he stressed mathematics as a way of understanding more about reality. In particular, he was convinced that geometry was the key to unlocking the secrets of the universe. The sign above the Academy entrance read: ‘Let no-one ignorant of geometry enter here.'»

- ^ Toraldo Di Francia 1976, p. 10 ‘Philosophy is written in that great book which ever lies before our eyes. I mean the universe, but we cannot understand it if we do not first learn the language and grasp the symbols in which it is written. This book is written in the mathematical language, and the symbols are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures, without whose help it is humanly impossible to comprehend a single word of it, and without which one wanders in vain through a dark labyrinth.’ – Galileo (1623), The Assayer«

- ^ «Applications of Mathematics to the Sciences». 25 January 2000. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ «Journal of Mathematical Physics». Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

[Journal of Mathematical Physics] purpose is the publication of papers in mathematical physics — that is, the application of mathematics to problems in physics and the development of mathematical methods suitable for such applications and for the formulation of physical theories.

- ^ a b The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 3: The Relation of Physics to Other Sciences; see also reductionism and special sciences

- ^ Ellis, G.; Silk, J. (16 December 2014). «Scientific method: Defend the integrity of physics». Nature. 516 (7531): 321–323. Bibcode:2014Natur.516..321E. doi:10.1038/516321a. PMID 25519115.

- ^ Honderich 1995, pp. 474–476

- ^ «Has theoretical physics moved too far away from experiments? Is the field entering a crisis and, if so, what should we do about it?». Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ «Phenomenology». Max Planck Institute for Physics. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Feynman 1965, p. 157 «In fact experimenters have a certain individual character. They … very often do their experiments in a region in which people know the theorist has not made any guesses.»

- ^ Stewart, J. (2001). Intermediate Electromagnetic Theory. World Scientific. p. 50. ISBN 978-981-02-4471-2.

- ^ Weinberg, S. (1993). Dreams of a Final Theory: The Search for the Fundamental Laws of Nature. Hutchinson Radius. ISBN 978-0-09-177395-3.

- ^ Redish, E. «Science and Physics Education Homepages». University of Maryland Physics Education Research Group. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016.

- ^ «Division of Particles & Fields». American Physical Society. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Halpern 2010

- ^ Grupen 1999

- ^ Walsh 2012

- ^ «High Energy Particle Physics Group». Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Oerter 2006

- ^ Gribbin, Gribbin & Gribbin 1998

- ^ «CERN experiments observe particle consistent with long-sought Higgs boson». CERN. 4 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ «Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics». MIT Department of Physics. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ «Korea University, Physics AMO Group». Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ «Aarhus Universitet, AMO Group». Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Taylor & Heinonen 2002

- ^ Girvin, Steven M.; Yang, Kun (28 February 2019). Modern Condensed Matter Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-57347-4. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Cohen 2008

- ^ Moore 2011, pp. 255–258

- ^ Leggett 1999

- ^ Levy 2001

- ^ Stajic, Coontz & Osborne 2011

- ^ Mattis 2006

- ^ a b «History of Condensed Matter Physics». American Physical Society. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ «Philip Anderson». Princeton University, Department of Physics. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ «BS in Astrophysics». University of Hawaii at Manoa. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ «NASA – Q&A on the GLAST Mission». Nasa: Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. NASA. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ See also Nasa – Fermi Science Archived 3 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine and NASA – Scientists Predict Major Discoveries for GLAST Archived 2 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Dark Matter». NASA. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ Kerr 2009

- ^ Leggett, A.J. (2006). «What DO we know about high Tc?» (PDF). Nature Physics. 2 (3): 134–136. Bibcode:2006NatPh…2..134L. doi:10.1038/nphys254. S2CID 122055331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2010.

- ^ Wolf, S.A.; Chtchelkanova, A.Y.; Treger, D.M. (2006). «Spintronics—A retrospective and perspective» (PDF). IBM Journal of Research and Development. 50: 101–110. doi:10.1147/rd.501.0101. S2CID 41178069. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2020.

- ^ Gibney, E. (2015). «LHC 2.0: A new view of the Universe». Nature. 519 (7542): 142–143. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..142G. doi:10.1038/519142a. PMID 25762263.

- ^ National Research Council & Committee on Technology for Future Naval Forces 1997, p. 161

- ^ Kellert 1993, p. 32

- ^ Eames, I.; Flor, J.B. (2011). «New developments in understanding interfacial processes in turbulent flows». Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 369 (1937): 702–705. Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369..702E. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0332. PMID 21242127.

Richard Feynman said that ‘Turbulence is the most important unsolved problem of classical physics’

- ^ National Research Council (2007). «What happens far from equilibrium and why». Condensed-Matter and Materials Physics: the science of the world around us. pp. 91–110. doi:10.17226/11967. ISBN 978-0-309-10969-7. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016.

– Jaeger, Heinrich M.; Liu, Andrea J. (2010). «Far-From-Equilibrium Physics: An Overview». arXiv:1009.4874 [cond-mat.soft]. - ^ Goldstein 1969

Sources

- Aaboe, A. (1991). «Mesopotamian Mathematics, Astronomy, and Astrology». The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- Abazov, V.; et al. (DØ Collaboration) (12 June 2007). «Direct observation of the strange ‘b’ baryon

«. Physical Review Letters. 99 (5): 052001. arXiv:0706.1690v2. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99e2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.052001. PMID 17930744. S2CID 11568965.

- Allen, D. (10 April 1997). «Calculus». Texas A&M University. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Ben-Chaim, M. (2004). Experimental Philosophy and the Birth of Empirical Science: Boyle, Locke and Newton. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4091-2. OCLC 53887772.

- Cajori, Florian (1917). A History of Physics in Its Elementary Branches: Including the Evolution of Physical Laboratories. Macmillan.

- Cho, A. (13 July 2012). «Higgs Boson Makes Its Debut After Decades-Long Search». Science. 337 (6091): 141–143. Bibcode:2012Sci…337..141C. doi:10.1126/science.337.6091.141. PMID 22798574.

- Clagett, M. (1995). Ancient Egyptian Science. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Cohen, M.L. (2008). «Fifty Years of Condensed Matter Physics». Physical Review Letters. 101 (5): 25001–25006. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.101y0001C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.250001. PMID 19113681.

- Dijksterhuis, E.J. (1986). The mechanization of the world picture: Pythagoras to Newton. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08403-9. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011.

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. 1. ISBN 978-0-201-02116-5.

- Feynman, R.P. (1965). The Character of Physical Law. ISBN 978-0-262-56003-0.

- Godfrey-Smith, P. (2003). Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science. ISBN 978-0-226-30063-4.

- Goldstein, S. (1969). «Fluid Mechanics in the First Half of this Century». Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 1 (1): 1–28. Bibcode:1969AnRFM…1….1G. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.01.010169.000245.

- Gribbin, J.R.; Gribbin, M.; Gribbin, J. (1998). Q is for Quantum: An Encyclopedia of Particle Physics. Free Press. Bibcode:1999qqep.book…..G. ISBN 978-0-684-85578-3.

- Grupen, Klaus (10 July 1999). «Instrumentation in Elementary Particle Physics: VIII ICFA School». AIP Conference Proceedings. 536: 3–34. arXiv:physics/9906063. Bibcode:2000AIPC..536….3G. doi:10.1063/1.1361756. S2CID 119476972.

- Guicciardini, N. (1999). Reading the Principia: The Debate on Newton’s Methods for Natural Philosophy from 1687 to 1736. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521640664.

- Halpern, P. (2010). Collider: The Search for the World’s Smallest Particles. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-64391-4.

- Hawking, S.; Penrose, R. (1996). The Nature of Space and Time. ISBN 978-0-691-05084-3.

- Holzner, S. (2006). Physics for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. Bibcode:2005pfd..book…..H. ISBN 978-0-470-61841-7.

Physics is the study of your world and the world and universe around you.

- Honderich, T., ed. (1995). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (1 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 474–476. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0.

- Howard, Ian; Rogers, Brian (1995). Binocular Vision and Stereopsis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508476-4.

- Kellert, S.H. (1993). In the Wake of Chaos: Unpredictable Order in Dynamical Systems. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-42976-2.

- Kerr, R.A. (16 October 2009). «Tying Up the Solar System With a Ribbon of Charged Particles». Science. 326 (5951): 350–351. doi:10.1126/science.326_350a. PMID 19833930.

- Krupp, E.C. (2003). Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42882-6. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Laplace, P.S. (1951). A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Translated from the 6th French edition by Truscott, F.W. and Emory, F.L. New York: Dover Publications.

- Leggett, A.J. (1999). «Superfluidity». Reviews of Modern Physics. 71 (2): S318–S323. Bibcode:1999RvMPS..71..318L. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.71.S318.

- Levy, Barbara G. (December 2001). «Cornell, Ketterle, and Wieman Share Nobel Prize for Bose-Einstein Condensates». Physics Today. 54 (12): 14. Bibcode:2001PhT….54l..14L. doi:10.1063/1.1445529.

- Lindberg, David (1992). The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press.

- Lloyd, G.E.R. (1970). Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle. London; New York: Chatto and Windus; W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00583-7.

- Mattis, D.C. (2006). The Theory of Magnetism Made Simple. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-238-579-6.

- Maxwell, J.C. (1878). Matter and Motion. D. Van Nostrand. ISBN 978-0-486-66895-6.

matter and motion.

- Moore, J.T. (2011). Chemistry For Dummies (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-00730-3.

- National Research Council; Committee on Technology for Future Naval Forces (1997). Technology for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, 2000–2035 Becoming a 21st-Century Force: Volume 9: Modeling and Simulation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-05928-2.

- O’Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (February 1996a). «Special Relativity». MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- O’Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (May 1996b). «A History of Quantum Mechanics». MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- Oerter, R. (2006). The Theory of Almost Everything: The Standard Model, the Unsung Triumph of Modern Physics. Pi Press. ISBN 978-0-13-236678-6.

- Penrose, R.; Shimony, A.; Cartwright, N.; Hawking, S. (1997). The Large, the Small and the Human Mind. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78572-3.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality. ISBN 978-0-679-45443-4.

- Rosenberg, Alex (2006). Philosophy of Science. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34317-6.

- Schrödinger, E. (1983). My View of the World. Ox Bow Press. ISBN 978-0-918024-30-5.

- Schrödinger, E. (1995). The Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Ox Bow Press. ISBN 978-1-881987-09-3.

- Singer, C. (2008). A Short History of Science to the 19th Century. Streeter Press.

- Smith, A. Mark (2001). Alhacen’s Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen’s De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham’s Kitāb al-Manāẓir, 2 vols. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 91. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-914-5. OCLC 47168716.

- Smith, A. Mark (2001a). «Alhacen’s Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen’s «De aspectibus», the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham’s «Kitāb al-Manāẓir»: Volume One». Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 91 (4): i–clxxxi, 1–337. doi:10.2307/3657358. JSTOR 3657358.

- Smith, A. Mark (2001b). «Alhacen’s Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary, of the First Three Books of Alhacen’s «De aspectibus», the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham’s «Kitāb al-Manāẓir»: Volume Two». Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 91 (5): 339–819. doi:10.2307/3657357. JSTOR 3657357.

- Stajic, Jelena; Coontz, R.; Osborne, I. (8 April 2011). «Happy 100th, Superconductivity!». Science. 332 (6026): 189. Bibcode:2011Sci…332..189S. doi:10.1126/science.332.6026.189. PMID 21474747.

- Taylor, P.L.; Heinonen, O. (2002). A Quantum Approach to Condensed Matter Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77827-5.

- Thurston, H. (1994). Early Astronomy. Springer.

- Tipler, Paul; Llewellyn, Ralph (2003). Modern Physics. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4345-3.

- Toraldo Di Francia, G. (1976). The Investigation of the Physical World. ISBN 978-0-521-29925-1.

- Walsh, K.M. (1 June 2012). «Plotting the Future for Computing in High-Energy and Nuclear Physics». Brookhaven National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Young, H.D.; Freedman, R.A. (2014). Sears and Zemansky’s University Physics with Modern Physics Technology Update (13th ed.). Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1-292-02063-1.

External links

- Physics at Quanta Magazine

- Usenet Physics FAQ – FAQ compiled by sci.physics and other physics newsgroups

- Website of the Nobel Prize in physics – Award for outstanding contributions to the subject

- World of Physics – Online encyclopedic dictionary of physics

- Nature Physics – Academic journal

- Physics – Online magazine by the American Physical Society

- Physics/Publications at Curlie – Directory of physics related media

- The Vega Science Trust – Science videos, including physics

- HyperPhysics website – Physics and astronomy mind-map from Georgia State University

- Physics at MIT OpenCourseWare – Online course material from Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- The Feynman Lectures on Physics

Not to be confused with Physis.

Physics is the natural science that studies matter,[a] its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force.[2] Physics is one of the most fundamental scientific disciplines, with its main goal being to understand how the universe behaves.[b][3][4][5] A scientist who specializes in the field of physics is called a physicist.

Physics is one of the oldest academic disciplines and, through its inclusion of astronomy, perhaps the oldest.[6] Over much of the past two millennia, physics, chemistry, biology, and certain branches of mathematics were a part of natural philosophy, but during the Scientific Revolution in the 17th century these natural sciences emerged as unique research endeavors in their own right.[c] Physics intersects with many interdisciplinary areas of research, such as biophysics and quantum chemistry, and the boundaries of physics are not rigidly defined. New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms studied by other sciences[3] and suggest new avenues of research in these and other academic disciplines such as mathematics and philosophy.

Advances in physics often enable advances in new technologies. For example, advances in the understanding of electromagnetism, solid-state physics, and nuclear physics led directly to the development of new products that have dramatically transformed modern-day society, such as television, computers, domestic appliances, and nuclear weapons;[3] advances in thermodynamics led to the development of industrialization; and advances in mechanics inspired the development of calculus.

History

The word «physics» comes from Ancient Greek: φυσική (ἐπιστήμη), romanized: physikḗ (epistḗmē), meaning «knowledge of nature».[8][9][10]

Ancient astronomy

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences. Early civilizations dating back before 3000 BCE, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, and the Indus Valley Civilisation, had a predictive knowledge and a basic awareness of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars. The stars and planets, believed to represent gods, were often worshipped. While the explanations for the observed positions of the stars were often unscientific and lacking in evidence, these early observations laid the foundation for later astronomy, as the stars were found to traverse great circles across the sky,[6] which could not explain the positions of the planets.

According to Asger Aaboe, the origins of Western astronomy can be found in Mesopotamia, and all Western efforts in the exact sciences are descended from late Babylonian astronomy.[11] Egyptian astronomers left monuments showing knowledge of the constellations and the motions of the celestial bodies,[12] while Greek poet Homer wrote of various celestial objects in his Iliad and Odyssey; later Greek astronomers provided names, which are still used today, for most constellations visible from the Northern Hemisphere.[13]

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy has its origins in Greece during the Archaic period (650 BCE – 480 BCE), when pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales rejected non-naturalistic explanations for natural phenomena and proclaimed that every event had a natural cause.[14] They proposed ideas verified by reason and observation, and many of their hypotheses proved successful in experiment;[15] for example, atomism was found to be correct approximately 2000 years after it was proposed by Leucippus and his pupil Democritus.[16]

Medieval European and Islamic

The Western Roman Empire fell in the fifth century, and this resulted in a decline in intellectual pursuits in the western part of Europe. By contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) resisted the attacks from the barbarians, and continued to advance various fields of learning, including physics.[17]

In the sixth century, Isidore of Miletus created an important compilation of Archimedes’ works that are copied in the Archimedes Palimpsest.

Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965–c. 1040), Book of Optics Book I, [6.85], [6.86]. Book II, [3.80] describes his camera obscura experiments.[18]

In sixth-century Europe John Philoponus, a Byzantine scholar, questioned Aristotle’s teaching of physics and noted its flaws. He introduced the theory of impetus. Aristotle’s physics was not scrutinized until Philoponus appeared; unlike Aristotle, who based his physics on verbal argument, Philoponus relied on observation. On Aristotle’s physics Philoponus wrote:

But this is completely erroneous, and our view may be corroborated by actual observation more effectively than by any sort of verbal argument. For if you let fall from the same height two weights of which one is many times as heavy as the other, you will see that the ratio of the times required for the motion does not depend on the ratio of the weights, but that the difference in time is a very small one. And so, if the difference in the weights is not considerable, that is, of one is, let us say, double the other, there will be no difference, or else an imperceptible difference, in time, though the difference in weight is by no means negligible, with one body weighing twice as much as the other[19]

Philoponus’ criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics served as an inspiration for Galileo Galilei ten centuries later,[20] during the Scientific Revolution. Galileo cited Philoponus substantially in his works when arguing that Aristotelian physics was flawed.[21][22] In the 1300s Jean Buridan, a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris, developed the concept of impetus. It was a step toward the modern ideas of inertia and momentum.[23]

Islamic scholarship inherited Aristotelian physics from the Greeks and during the Islamic Golden Age developed it further, especially placing emphasis on observation and a priori reasoning, developing early forms of the scientific method.

Although Aristotle’s principles of physics was criticized, it is important to identify his the evidence he based his views off of. When thinking of the history of science and math, it is notable to acknowledge the contributions made by older scientists. Aristotle’s science was the backbone of the science we learn in schools today. Aristotle published many biological works including The Parts of Animals, in which he discusses both biological science and natural science as well. It is also integral to mention the role Aristotle had in the progression of physics and metaphysics and how his beliefs and findings are still being taught in science classes to this day. The explanations that Aristotle gives for his findings are also very simple. When thinking of the elements, Aristotle believed that each element (earth, fire, water, air) had its own natural place. Meaning that because of the density of these elements, they will revert back to their own specific place in the atmosphere.[24] So, because of their weights, fire would be at the very top, air right underneath fire, then water, then lastly earth. He also stated that when a small amount of one element enters the natural place of another, the less abundant element will automatically go into its own natural place. For example, if there is a fire on the ground, if you pay attention, the flames go straight up into the air as an attempt to go back into its natural place where it belongs. Aristotle called his metaphysics “first philosophy” and characterized it as the study of “being as being”.[25] Aristotle defined the paradigm of motion as a being or entity encompassing different areas in the same body. [25]Meaning that if a person is at a certain location (A) they can move to a new location (B) and still take up the same amount of space. This is involved with Aristotle’s belief that motion is a continuum. In terms of matter, Aristotle believed that the change in category (ex. place) and quality (ex. color) of an object is defined as “alteration”. But, a change in substance is a change in matter. This is also very close to our idea of matter today.

He also devised his own laws of motion that include 1) heavier objects will fall faster, the speed being proportional to the weight and 2) the speed of the object that is falling depends inversely on the density object it is falling through (ex. density of air).[26] He also stated that, when it comes to violent motion (motion of an object when a force is applied to it by a second object) that the speed that object moves, will only be as fast or strong as the measure of force applied to it.[26] This is also seen in the rules of velocity and force that is taught in physics classes today. These rules are not necessarily what we see in our physics today but, they are very similar. It is evident that these rules were the backbone for other scientists to come revise and edit his beliefs.

The basic way a pinhole camera works

The most notable innovations were in the field of optics and vision, which came from the works of many scientists like Ibn Sahl, Al-Kindi, Ibn al-Haytham, Al-Farisi and Avicenna. The most notable work was The Book of Optics (also known as Kitāb al-Manāẓir), written by Ibn al-Haytham, in which he conclusively disproved the ancient Greek idea about vision and came up with a new theory. In the book, he presented a study of the phenomenon of the camera obscura (his thousand-year-old version of the pinhole camera) and delved further into the way the eye itself works. Using dissections and the knowledge of previous scholars, he was able to begin to explain how light enters the eye. He asserted that the light ray is focused, but the actual explanation of how light projected to the back of the eye had to wait until 1604. His Treatise on Light explained the camera obscura, hundreds of years before the modern development of photography.[27]

The seven-volume Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manathir) hugely influenced thinking across disciplines from the theory of visual perception to the nature of perspective in medieval art, in both the East and the West, for more than 600 years. Many later European scholars and fellow polymaths, from Robert Grosseteste and Leonardo da Vinci to René Descartes, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton, were in his debt. Indeed, the influence of Ibn al-Haytham’s Optics ranks alongside that of Newton’s work of the same title, published 700 years later.

The translation of The Book of Optics had a huge impact on Europe. From it, later European scholars were able to build devices that replicated those Ibn al-Haytham had built and understand the way light works. From this, important inventions such as eyeglasses, magnifying glasses, telescopes, and cameras were developed.

Classical

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) showed a modern appreciation for the proper relationship between mathematics, theoretical physics, and experimental physics.