«Joseph Biden» and «Biden» redirect here. For his son Joseph Biden III, see Beau Biden. For other uses, see Biden (disambiguation).

|

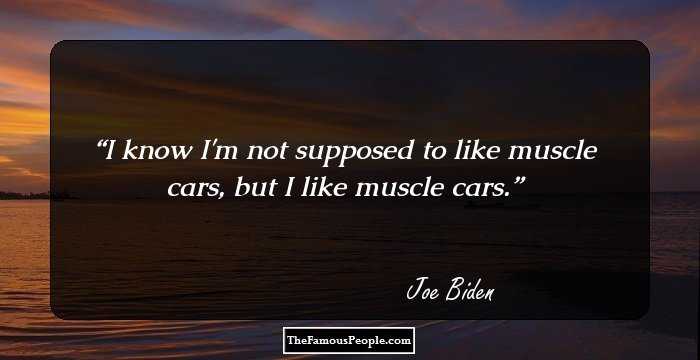

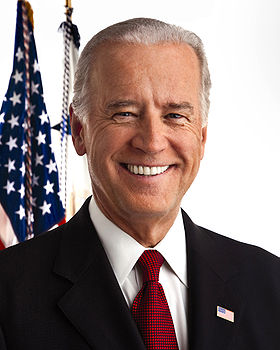

Joe Biden |

|

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2021 |

|

| 46th President of the United States | |

|

Incumbent |

|

| Assumed office January 20, 2021 |

|

| Vice President | Kamala Harris |

| Preceded by | Donald Trump |

| 47th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 2009 – January 20, 2017 |

|

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Dick Cheney |

| Succeeded by | Mike Pence |

| United States Senator from Delaware |

|

| In office January 3, 1973 – January 15, 2009 |

|

| Preceded by | J. Caleb Boggs |

| Succeeded by | Ted Kaufman |

| Member of the New Castle County Council from the 4th district |

|

| In office January 5, 1971 – January 3, 1973 |

|

| Preceded by | Lawrence T. Messick |

| Succeeded by | Francis R. Swift |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. November 20, 1942 (age 80) |

| Political party | Democratic (1969–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

Independent (before 1969) |

| Spouses |

Neilia Hunter (m. ; died ) Jill Jacobs (m. ) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Biden family |

| Residences |

|

| Education | Archmere Academy |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of honors and awards |

| Signature |  |

| Website |

|

|

Other offices

|

|

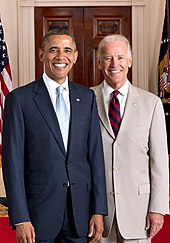

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. ( BY-dən; born November 20, 1942) is an American politician who is the 46th and current president of the United States. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 47th vice president from 2009 to 2017 under President Barack Obama, and represented Delaware in the United States Senate from 1973 to 2009.

Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Biden moved with his family to Delaware in 1953. He studied at the University of Delaware before earning his law degree from Syracuse University. He was elected to the New Castle County Council in 1970 and became the sixth-youngest senator in U.S. history after he was elected to the United States Senate from Delaware in 1972, at age 29. Biden was the chair or ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for 12 years. He chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee from 1987 to 1995; led the effort to pass the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act and the Violence Against Women Act; and oversaw six U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings, including the contentious hearings for Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas.

Biden ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1988 and 2008, before becoming Obama’s vice president after they won the 2008 presidential election. During his two terms as vice president, Biden frequently represented the administration in negotiations with congressional Republicans and was a close counselor to Obama.

Biden and his running mate, Kamala Harris, defeated incumbent Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election. He became the oldest president in U.S. history and the first to have a female vice president. Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act to address the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent recession; the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act; the Inflation Reduction Act covering deficit reduction, climate change, healthcare, and tax reform; and the Respect for Marriage Act, which codified protections for interracial and same-sex marriages. Biden appointed Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court. In foreign policy, he restored America’s membership in the Paris Agreement on climate change. He completed the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, during which the Afghan government collapsed and the Taliban seized control. He responded to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine by imposing sanctions on Russia and authorizing foreign aid and weapons shipments to Ukraine.

Early life (1942–1965)

Biden at Archmere Academy in the 1950s

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. was born on November 20, 1942,[1] at St. Mary’s Hospital in Scranton, Pennsylvania,[2] to Catherine Eugenia «Jean» Biden (née Finnegan) and Joseph Robinette Biden Sr.[3][4] The oldest child in a Catholic family, he has a sister, Valerie, and two brothers, Francis and James.[5] Jean was of Irish descent,[6][7][8] while Joseph Sr. had English, Irish, and French Huguenot ancestry.[9][10][8] Biden’s paternal line has been traced to stonemason William Biden, who was born in 1789 in Westbourne, England, and emigrated to Maryland in the United States by 1820.[11]

Biden’s father had been wealthy and the family purchased a home in the affluent Long Island suburb of Garden City in the fall of 1946,[12] but he suffered business setbacks around the time Biden was seven years old,[13][14][15] and for several years the family lived with Biden’s maternal grandparents in Scranton.[16] Scranton fell into economic decline during the 1950s and Biden’s father could not find steady work.[17] Beginning in 1953 when Biden was ten,[18] the family lived in an apartment in Claymont, Delaware, before moving to a house in nearby Mayfield.[19][20][14][16] Biden Sr. later became a successful used-car salesman, maintaining the family in a middle-class lifestyle.[16][17][21]

At Archmere Academy in Claymont,[22] Biden played baseball and was a standout halfback and wide receiver on the high school football team.[16][23] Though a poor student, he was class president in his junior and senior years.[24][25] He graduated in 1961.[24] At the University of Delaware in Newark, Biden briefly played freshman football,[26][27] and, as an unexceptional student,[28] earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1965 with a double major in history and political science and a minor in English.[29][30]

Biden has a stutter, which has improved since his early twenties.[31] He says he reduced it by reciting poetry before a mirror,[25][32] but some observers suggested it affected his performance in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential debates.[33][34][35]

Marriages, law school, and early career (1966–1973)

On August 27, 1966, Biden married Neilia Hunter (1942–1972), a student at Syracuse University,[29] after overcoming her parents’ reluctance for her to wed a Roman Catholic. Their wedding was held in a Catholic church in Skaneateles, New York.[36] They had three children: Joseph R. «Beau» Biden III (1969–2015), Robert Hunter Biden (born 1970), and Naomi Christina «Amy» Biden (1971–1972).[29]

Biden in the Syracuse 1968 yearbook

In 1968, Biden earned a Juris Doctor from Syracuse University College of Law, ranked 76th in his class of 85, after failing a course due to an acknowledged «mistake» when he plagiarized a law review article for a paper he wrote in his first year at law school.[28] He was admitted to the Delaware bar in 1969.[1]

Biden had not openly supported or opposed the Vietnam War until he ran for Senate and opposed Nixon’s conduct of the war.[37] While studying at the University of Delaware and Syracuse University, Biden obtained five student draft deferments, at a time when most draftees were sent to the Vietnam War. In 1968, based on a physical examination, he was given a conditional medical deferment; in 2008, a spokesperson for Biden said his having had «asthma as a teenager» was the reason for the deferment.[38]

In 1968, Biden clerked at a Wilmington law firm headed by prominent local Republican William Prickett and, he later said, «thought of myself as a Republican».[39][40] He disliked incumbent Democratic Delaware governor Charles L. Terry’s conservative racial politics and supported a more liberal Republican, Russell W. Peterson, who defeated Terry in 1968.[39] Biden was recruited by local Republicans but registered as an Independent because of his distaste for Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon.[39]

In 1969, Biden practiced law, first as a public defender and then at a firm headed by a locally active Democrat[41][39] who named him to the Democratic Forum, a group trying to reform and revitalize the state party;[42] Biden subsequently reregistered as a Democrat.[39] He and another attorney also formed a law firm.[41] Corporate law, however, did not appeal to him, and criminal law did not pay well.[16] He supplemented his income by managing properties.[43]

In 1970, Biden ran for the 4th district seat on the New Castle County Council on a liberal platform that included support for public housing in the suburbs.[44][41][45] The seat had been held by Republican Henry R. Folsom, who was running in the 5th District following a reapportionment of council districts.[46][47][48] Biden won the general election by defeating Republican Lawrence T. Messick, and took office on January 5, 1971.[49][50] He served until January 1, 1973, and was succeeded by Democrat Francis R. Swift.[51][52][53][54] During his time on the county council, Biden opposed large highway projects, which he argued might disrupt Wilmington neighborhoods.[55]

1972 U.S. Senate campaign in Delaware

Results of the 1972 U.S. Senate election in Delaware

In 1972, Biden defeated Republican incumbent J. Caleb Boggs to become the junior U.S. senator from Delaware. He was the only Democrat willing to challenge Boggs, and with minimal campaign funds, he was given no chance of winning.[41][16] Family members managed and staffed the campaign, which relied on meeting voters face-to-face and hand-distributing position papers,[56] an approach made feasible by Delaware’s small size.[43] He received help from the AFL–CIO and Democratic pollster Patrick Caddell.[41] His platform focused on the environment, withdrawal from Vietnam, civil rights, mass transit, equitable taxation, health care, and public dissatisfaction with «politics as usual».[41][56] A few months before the election, Biden trailed Boggs by almost thirty percentage points,[41] but his energy, attractive young family, and ability to connect with voters’ emotions worked to his advantage[21] and he won with 50.5 percent of the vote.[56]

Death of wife and daughter

On December 18, 1972, a few weeks after Biden was elected senator, his wife Neilia and one-year-old daughter Naomi were killed in an automobile accident while Christmas shopping in Hockessin, Delaware.[29][57] Neilia’s station wagon was hit by a semi-trailer truck as she pulled out from an intersection. Their sons Beau (aged 3) and Hunter (aged 2) were taken to the hospital in fair condition, Beau with a broken leg and other wounds and Hunter with a minor skull fracture and other head injuries.[58] Biden considered resigning to care for them,[21] but Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield persuaded him not to.[59] The accident filled Biden with anger and religious doubt. He wrote that he «felt God had played a horrible trick» on him,[60] and he had trouble focusing on work.[61][62]

After the truck driver passed away in 1999, Biden in 2001 and 2007 accused the truck driver of drinking before the crash, even though the truck driver was never charged, and the chief prosecutor investigating the case stated that there was no evidence of drunk driving.[63] In 2008, Biden’s spokesman said that Biden «fully accepts» that allegations of drunk driving were «false».[64] The truck driver’s daughter said that Biden called her after a 2009 media report to apologize «for hurting my family in any way».[65]

Second marriage

Biden and his second wife, Jill, met in 1975 and married in 1977.

Biden met the teacher Jill Tracy Jacobs in 1975 on a blind date.[66] They married at the United Nations chapel in New York on June 17, 1977.[67][68] They spent their honeymoon at Lake Balaton in the Hungarian People’s Republic.[69][70] Biden credits her with the renewal of his interest in politics and life.[71] They are Roman Catholics and attend Mass at St. Joseph’s on the Brandywine in Greenville, Delaware.[72] Their daughter Ashley Biden (born 1981)[29] is a social worker. She is married to physician Howard Krein.[73] Beau Biden became an Army Judge Advocate in Iraq and later Delaware Attorney General[74] before dying of brain cancer in 2015.[75][76] As of 2008, Hunter Biden was a Washington lobbyist and investment adviser.[77]

Teaching

From 1991 to 2008, as an adjunct professor, Biden co-taught a seminar on constitutional law at Widener University School of Law.[78][79] The seminar often had a waiting list. Biden sometimes flew back from overseas to teach the class.[80][81][82][83]

U.S. Senate (1973–2009)

Senate activities

In January 1973, secretary of the Senate Francis R. Valeo swore Biden in at the Delaware Division of the Wilmington Medical Center.[84][58] Present were his sons Beau (whose leg was still in traction from the automobile accident) and Hunter and other family members.[84][58] At 30, he was the sixth-youngest senator in U.S. history.[85] To see his sons, Biden traveled by train between his Delaware home and D.C.[86]—74 minutes each way—and maintained this habit throughout his 36 years in the Senate.[21]

Elected to the Senate in 1972, Biden was reelected in 1978, 1984, 1990, 1996, 2002, and 2008, regularly receiving about 60% of the vote.[87] He was junior senator to William Roth, who was first elected in 1970, until Roth was defeated in 2000.[88] As of 2022, he was the 19th-longest-serving senator in U.S. history.[89]

During his early years in the Senate, Biden focused on consumer protection and environmental issues and called for greater government accountability.[90] In a 1974 interview, he described himself as liberal on civil rights and liberties, senior citizens’ concerns and healthcare but conservative on other issues, including abortion and military conscription.[91] Biden also worked on arms control.[92][93] After Congress failed to ratify the SALT II Treaty signed in 1979 by Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and President Jimmy Carter, Biden met with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko to communicate American concerns and secured changes that addressed the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s objections.[94] He received considerable attention when he excoriated Secretary of State George Shultz at a Senate hearing for the Reagan administration’s support of South Africa despite its continued policy of apartheid.[39]

In the mid-1970s, Biden was one of the Senate’s strongest opponents of race-integration busing. His Delaware constituents strongly opposed it, and such opposition nationwide later led his party to mostly abandon school integration policies.[95] In his first Senate campaign, Biden had expressed support for busing to remedy de jure segregation, as in the South, but opposed its use to remedy de facto segregation arising from racial patterns of neighborhood residency, as in Delaware; he opposed a proposed constitutional amendment banning busing entirely.[96] Biden supported a measure[when?] forbidding the use of federal funds for transporting students beyond the school closest to them. In 1977, he co-sponsored an amendment closing loopholes in that measure, which President Carter signed into law in 1978.[97]

Biden became ranking minority member of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1981. In 1984, he was a Democratic floor manager for the successful passage of the Comprehensive Crime Control Act. His supporters praised him for modifying some of the law’s worst provisions, and it was his most important legislative accomplishment to that time.[98] In 1994, Biden helped pass the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which included a ban on assault weapons,[99][100] and the Violence Against Women Act,[101] which he has called his most significant legislation.[102] The 1994 crime law was unpopular among progressives and criticized for resulting in mass incarceration;[103][104] in 2019, Biden called his role in passing the bill a «big mistake», citing its policy on crack cocaine and saying that the bill «trapped an entire generation».[105]

In 1993, Biden voted for a provision that deemed homosexuality incompatible with military life, thereby banning gays from serving in the armed forces.[106][107] In 1996, he voted for the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages, thereby barring individuals in such marriages from equal protection under federal law and allowing states to do the same.[108] In 2015, the act was ruled unconstitutional in Obergefell v. Hodges.[109]

Biden was critical of Independent Counsel Ken Starr during the 1990s Whitewater controversy and Lewinsky scandal investigations, saying «it’s going to be a cold day in hell» before another independent counsel would be granted similar powers.[110] He voted to acquit during the impeachment of President Clinton.[111] During the 2000s, Biden sponsored bankruptcy legislation sought by credit card issuers.[21] Clinton vetoed the bill in 2000, but it passed in 2005 as the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act,[21] with Biden being one of only 18 Democrats to vote for it, while leading Democrats and consumer rights organizations opposed it.[112] As a senator, Biden strongly supported increased Amtrak funding and rail security.[87][113]

Brain surgeries

In February 1988, after several episodes of increasingly severe neck pain, Biden was taken by ambulance to Walter Reed Army Medical Center for surgery to correct a leaking intracranial berry aneurysm.[114][115] While recuperating, he suffered a pulmonary embolism, a serious complication.[115] After a second aneurysm was surgically repaired in May,[115][116] Biden’s recuperation kept him away from the Senate for seven months.[117]

Senate Judiciary Committee

Biden was a longtime member of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He chaired it from 1987 to 1995 and was a ranking minority member from 1981 to 1987 and again from 1995 to 1997.

As chair, Biden presided over two highly contentious U.S. Supreme Court confirmation hearings.[21] When Robert Bork was nominated in 1988, Biden reversed his approval—given in an interview the previous year—of a hypothetical Bork nomination. Conservatives were angered,[118] but at the hearings’ close Biden was praised for his fairness, humor, and courage.[118][119] Rejecting the arguments of some Bork opponents,[21] Biden framed his objections to Bork in terms of the conflict between Bork’s strong originalism and the view that the U.S. Constitution provides rights to liberty and privacy beyond those explicitly enumerated in its text.[119] Bork’s nomination was rejected in the committee by a 9–5 vote[119] and then in the full Senate, 58–42.[120]

During Clarence Thomas’s nomination hearings in 1991, Biden’s questions on constitutional issues were often convoluted to the point that Thomas sometimes lost track of them,[121] and Thomas later wrote that Biden’s questions were akin to «beanballs».[122] After the committee hearing closed, the public learned that Anita Hill, a University of Oklahoma law school professor, had accused Thomas of making unwelcome sexual comments when they had worked together.[123][124] Biden had known of some of these charges, but initially shared them only with the committee because Hill was then unwilling to testify.[21] The committee hearing was reopened and Hill testified, but Biden did not permit testimony from other witnesses, such as a woman who had made similar charges and experts on harassment.[125] The full Senate confirmed Thomas by a 52–48 vote, with Biden opposed.[21] Liberal legal advocates and women’s groups felt strongly that Biden had mishandled the hearings and not done enough to support Hill.[125] In 2019, he told Hill he regretted his treatment of her, but Hill said afterward she remained unsatisfied.[126]

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Biden was a longtime member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He became its ranking minority member in 1997 and chaired it from June 2001 to 2003 and 2007 to 2009.[127] His positions were generally liberal internationalist.[92][128] He collaborated effectively with Republicans and sometimes went against elements of his own party.[127][128] During this time he met with at least 150 leaders from 60 countries and international organizations, becoming a well-known Democratic voice on foreign policy.[129]

Biden voted against authorization for the Gulf War in 1991,[128] siding with 45 of the 55 Democratic senators; he said the U.S. was bearing almost all the burden in the anti-Iraq coalition.[130]

Biden became interested in the Yugoslav Wars after hearing about Serbian abuses during the Croatian War of Independence in 1991.[92] Once the Bosnian War broke out, Biden was among the first to call for the «lift and strike» policy.[92][127] The George H. W. Bush administration and Clinton administration were both reluctant to implement the policy, fearing Balkan entanglement.[92][128] In April 1993, Biden held a tense three-hour meeting with Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević.[131] Biden said he had told Milošević, «I think you’re a damn war criminal and you should be tried as one.»[131] Biden wrote an amendment in 1992 to compel the Bush administration to arm the Bosnian Muslims, but deferred in 1994 to a somewhat softer stance the Clinton administration preferred, before signing on the following year to a stronger measure sponsored by Bob Dole and Joe Lieberman.[131] The engagement led to a successful NATO peacekeeping effort.[92] Biden has called his role in affecting Balkans policy in the mid-1990s his «proudest moment in public life» related to foreign policy.[128] In 1999, during the Kosovo War, Biden supported the 1999 NATO bombing of FR Yugoslavia.[92] He and Senator John McCain co-sponsored the McCain-Biden Kosovo Resolution, which called on Clinton to use all necessary force, including ground troops, to confront Milošević over Yugoslav actions toward ethnic Albanians in Kosovo.[128][132]

Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

Biden addresses the press after meeting with Prime Minister Ayad Allawi in Baghdad in 2004.

Biden was a strong supporter of the War in Afghanistan, saying, «Whatever it takes, we should do it.»[133] As head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he said in 2002 that Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was a threat to national security and there was no other option than to «eliminate» that threat.[134] In October 2002, he voted in favor of the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq, approving the U.S. Invasion of Iraq.[128] As chair of the committee, he assembled a series of witnesses to testify in favor of the authorization. They gave testimony grossly misrepresenting the intent, history, and status of Saddam and his secular government, which was an avowed enemy of al-Qaeda, and touted Iraq’s fictional possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction.[135] Biden eventually became a critic of the war and viewed his vote and role as a «mistake», but did not push for withdrawal.[128][131] He supported the appropriations for the occupation, but argued that the war should be internationalized, that more soldiers were needed, and that the Bush administration should «level with the American people» about its cost and length.[127][132]

By late 2006, Biden’s stance had shifted considerably. He opposed the troop surge of 2007,[128][131] saying General David Petraeus was «dead, flat wrong» in believing the surge could work.[136] Biden instead advocated dividing Iraq into a loose federation of three ethnic states.[137] In November 2006, Biden and Leslie H. Gelb, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, released a comprehensive strategy to end sectarian violence in Iraq.[138] Rather than continue the existing approach or withdrawing, the plan called for «a third way»: federalizing Iraq and giving Kurds, Shiites, and Sunnis «breathing room» in their own regions.[139] In September 2007, a non-binding resolution endorsing the plan passed the Senate,[138] but the idea failed to gain traction.[136] In May 2008, Biden sharply criticized President George W. Bush’s speech to Israel’s Knesset in which Bush compared some Democrats to Western leaders who appeased Hitler before World War II; Biden called the speech «bullshit», «malarkey», and «outrageous».[140]

Presidential campaigns of 1988 and 2008

1988 campaign

Biden at the White House in 1987

Biden formally declared his candidacy for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination on June 9, 1987.[141] He was considered a strong candidate because of his moderate image, his speaking ability, his high profile as chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the upcoming Robert Bork Supreme Court nomination hearings, and his appeal to Baby Boomers; he would have been the second-youngest person elected president, after John F. Kennedy.[39][142][143] He raised more in the first quarter of 1987 than any other candidate.[142][143]

By August his campaign’s messaging had become confused due to staff rivalries,[144] and in September, he was accused of plagiarizing a speech by British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock.[145] Biden’s speech had similar lines about being the first person in his family to attend university. Biden had credited Kinnock with the formulation on previous occasions,[146][147] but did not on two occasions in late August.[148]: 230–232 [147] Kinnock himself was more forgiving; the two men met in 1988, forming an enduring friendship.[149]

Earlier that year he had also used passages from a 1967 speech by Robert F. Kennedy (for which his aides took blame) and a short phrase from John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address; two years earlier he had used a 1976 passage by Hubert Humphrey.[150] Biden responded that politicians often borrow from one another without giving credit, and that one of his rivals for the nomination, Jesse Jackson, had called him to point out that he (Jackson) had used the same material by Humphrey that Biden had used.[21][28]

A few days later, an incident in law school in which Biden drew text from a Fordham Law Review article with inadequate citations was publicized.[28] He was required to repeat the course and passed with high marks.[151] At Biden’s request the Delaware Supreme Court’s Board of Professional Responsibility reviewed the incident and concluded that he had violated no rules.[152]

Biden has made several false or exaggerated claims about his early life: that he had earned three degrees in college, that he attended law school on a full scholarship, that he had graduated in the top half of his class,[153][154] and that he had marched in the civil rights movement.[155] The limited amount of other news about the presidential race amplified these disclosures[156] and on September 23, 1987, Biden withdrew his candidacy, saying it had been overrun by «the exaggerated shadow» of his past mistakes.[157]

2008 campaign

After exploring the possibility of a run in several previous cycles, in January 2007, Biden declared his candidacy in the 2008 elections.[87][158][159] During his campaign, Biden focused on the Iraq War, his record as chairman of major Senate committees, and his foreign-policy experience. In mid-2007, Biden stressed his foreign policy expertise compared to Obama’s.[160] Biden was noted for his one-liners during the campaign; in one debate he said of Republican candidate Rudy Giuliani: «There’s only three things he mentions in a sentence: a noun, and a verb and 9/11.»[161]

Biden had difficulty raising funds, struggled to draw people to his rallies, and failed to gain traction against the high-profile candidacies of Obama and Senator Hillary Clinton.[162] He never rose above single digits in national polls of the Democratic candidates. In the first contest on January 3, 2008, Biden placed fifth in the Iowa caucuses, garnering slightly less than one percent of the state delegates.[163] He withdrew from the race that evening.[164]

Despite its lack of success, Biden’s 2008 campaign raised his stature in the political world.[165]: 336 In particular, it changed the relationship between Biden and Obama. Although they had served together on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, they had not been close: Biden resented Obama’s quick rise to political stardom,[136][166] while Obama viewed Biden as garrulous and patronizing.[165]: 28, 337–338 Having gotten to know each other during 2007, Obama appreciated Biden’s campaign style and appeal to working-class voters, and Biden said he became convinced Obama was «the real deal».[166][165]: 28, 337–338

2008 vice-presidential campaign

Shortly after Biden withdrew from the presidential race, Obama privately told him he was interested in finding an important place for Biden in his administration.[167] In early August, Obama and Biden met in secret to discuss the possibility,[167] and developed a strong personal rapport.[166] On August 22, 2008, Obama announced that Biden would be his running mate.[168] The New York Times reported that the strategy behind the choice reflected a desire to fill out the ticket with someone with foreign policy and national security experience.[169] Others pointed out Biden’s appeal to middle-class and blue-collar voters.[170][171] Biden was officially nominated for vice president on August 27 by voice vote at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver.[172]

Biden’s vice-presidential campaigning gained little media attention, as the press devoted far more coverage to the Republican nominee, Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[173][174] Under instructions from the campaign, Biden kept his speeches succinct and tried to avoid offhand remarks, such as one he made about Obama’s being tested by a foreign power soon after taking office, which had attracted negative attention.[175][176] Privately, Biden’s remarks frustrated Obama. «How many times is Biden gonna say something stupid?» he asked.[165]: 411–414, 419 Obama campaign staffers called Biden’s blunders «Joe bombs» and kept Biden uninformed about strategy discussions, which in turn irked Biden.[177] Relations between the two campaigns became strained for a month, until Biden apologized on a call to Obama and the two built a stronger partnership.[165]: 411–414 Publicly, Obama strategist David Axelrod said Biden’s high popularity ratings had outweighed any unexpected comments.[178]

As the financial crisis of 2007–2010 reached a peak with the liquidity crisis of September 2008 and the proposed bailout of the United States financial system became a major factor in the campaign, Biden voted for the $700 billion Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which passed in the Senate, 74–25.[179] On October 2, 2008, he participated in the vice-presidential debate with Palin at Washington University in St. Louis. Post-debate polls found that while Palin exceeded many voters’ expectations, Biden had won the debate overall.[180] Nationally, Biden had a 60% favorability rating in a Pew Research Center poll, compared to Palin’s 44%.[175]

On November 4, 2008, Obama and Biden were elected with 53% of the popular vote and 365 electoral votes to McCain–Palin’s 173.[181][182][183]

At the same time Biden was running for vice president, he was also running for reelection to the Senate,[184] as permitted by Delaware law.[87] On November 4, he was reelected to the Senate, defeating Republican Christine O’Donnell.[185] Having won both races, Biden made a point of waiting to resign from the Senate until he was sworn in for his seventh term on January 6, 2009.[186] Biden cast his last Senate vote on January 15, supporting the release of the second $350 billion for the Troubled Asset Relief Program,[187] and resigned from the Senate later that day.[n 2]

Vice presidency (2009–2017)

First term (2009–2013)

First official portrait of Joe Biden as Vice President of the United States, 2009

Biden said he intended to eliminate some explicit roles assumed by George W. Bush’s vice president, Dick Cheney, and did not intend to emulate any previous vice presidency.[191] He chaired Obama’s transition team[192] and headed an initiative to improve middle-class economic well-being.[193] In early January 2009, in his last act as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, he visited the leaders of Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan,[194] and on January 20 he was sworn in as the 47th vice president of the United States[195]—the first vice president from Delaware[196] and the first Roman Catholic vice president.[197][198]

Obama was soon comparing Biden to a basketball player «who does a bunch of things that don’t show up in the stat sheet».[199] In May, Biden visited Kosovo and affirmed the U.S. position that its «independence is irreversible».[200] Biden lost an internal debate to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton about sending 21,000 new troops to Afghanistan,[201][202] but his skepticism was valued,[203] and in 2009, Biden’s views gained more influence as Obama reconsidered his Afghanistan strategy.[204] Biden visited Iraq about every two months,[136] becoming the administration’s point man in delivering messages to Iraqi leadership about expected progress there.[203] More generally, overseeing Iraq policy became Biden’s responsibility: Obama was said to have said, «Joe, you do Iraq.»[205] By 2012, Biden had made eight trips there, but his oversight of U.S. policy in Iraq receded with the exit of U.S. troops in 2011.[206][207]

Biden oversaw infrastructure spending from the Obama stimulus package intended to help counteract the ongoing recession.[208] During this period, Biden was satisfied that no major instances of waste or corruption had occurred,[203] and when he completed that role in February 2011, he said the number of fraud incidents with stimulus monies had been less than one percent.[209]

In late April 2009, Biden’s off-message response to a question during the beginning of the swine flu outbreak led to a swift retraction by the White House.[210] The remark revived Biden’s reputation for gaffes.[211][204][212] Confronted with rising unemployment through July 2009, Biden acknowledged that the administration had «misread how bad the economy was» but maintained confidence the stimulus package would create many more jobs once the pace of expenditures picked up.[213] On March 23, 2010, a microphone picked up Biden telling the president that his signing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was «a big fucking deal» during live national news telecasts. Despite their different personalities, Obama and Biden formed a friendship, partly based around Obama’s daughter Sasha and Biden’s granddaughter Maisy, who attended Sidwell Friends School together.[177]

Members of the Obama administration said Biden’s role in the White House was to be a contrarian and force others to defend their positions.[214] Rahm Emanuel, White House chief of staff, said that Biden helped counter groupthink.[199] Obama said, «The best thing about Joe is that when we get everybody together, he really forces people to think and defend their positions, to look at things from every angle, and that is very valuable for me.»[203] The Bidens maintained a relaxed atmosphere at their official residence in Washington, often entertaining their grandchildren, and regularly returned to their home in Delaware.[215]

Biden campaigned heavily for Democrats in the 2010 midterm elections, maintaining an attitude of optimism in the face of predictions of large-scale losses for the party.[216] Following big Republican gains in the elections and the departure of White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, Biden’s past relationships with Republicans in Congress became more important.[217][218] He led the successful administration effort to gain Senate approval for the New START treaty.[217][218] In December 2010, Biden’s advocacy for a middle ground, followed by his negotiations with Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, were instrumental in producing the administration’s compromise tax package that included a temporary extension of the Bush tax cuts.[218][219] The package passed as the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010.

In March 2011, Obama delegated Biden to lead negotiations with Congress to resolve federal spending levels for the rest of the year and avoid a government shutdown.[220] The U.S. debt ceiling crisis developed over the next few months, but Biden’s relationship with McConnell again proved key in breaking a deadlock and bringing about a deal to resolve it, in the form of the Budget Control Act of 2011, signed on August 2, 2011, the same day an unprecedented U.S. default had loomed.[221][222][223] Some reports suggest that Biden opposed proceeding with the May 2011 U.S. mission to kill Osama bin Laden,[206][224] lest failure adversely affect Obama’s reelection prospects.[225][226]

Reelection

In October 2010, Biden said Obama had asked him to remain as his running mate for the 2012 presidential election,[216] but with Obama’s popularity on the decline, White House Chief of Staff William M. Daley conducted some secret polling and focus group research in late 2011 on the idea of replacing Biden on the ticket with Hillary Clinton.[227] The notion was dropped when the results showed no appreciable improvement for Obama,[227] and White House officials later said Obama himself had never entertained the idea.[228]

Biden and Obama, July 2012

Biden’s May 2012 statement that he was «absolutely comfortable» with same-sex marriage gained considerable public attention in comparison to Obama’s position, which had been described as «evolving».[229] Biden made his statement without administration consent, and Obama and his aides were quite irked, since Obama had planned to shift position several months later, in the build-up to the party convention.[177][230][231] Gay rights advocates seized upon Biden’s statement,[230] and within days, Obama announced that he too supported same-sex marriage, an action in part forced by Biden’s remarks.[232] Biden apologized to Obama in private for having spoken out,[233][234] while Obama acknowledged publicly it had been done from the heart.[230]

The Obama campaign valued Biden as a retail-level politician, and he had a heavy schedule of appearances in swing states as the reelection campaign began in earnest in spring 2012.[235][206] An August 2012 remark before a mixed-race audience that Republican proposals to relax Wall Street regulations would «put y’all back in chains» once again drew attention to Biden’s propensity for colorful remarks.[235][236][237] In the vice-presidential debate on October 11 with Republican nominee Paul Ryan, Biden defended the Obama administration’s record.[238][239] On November 6, Obama and Biden won reelection[240] over Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan with 332 of 538 Electoral College votes and 51% of the popular vote.[241]

In December 2012, Obama named Biden to head the Gun Violence Task Force, created to address the causes of school shootings and consider possible gun control to implement in the aftermath of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.[242] Later that month, during the final days before the United States fell off the «fiscal cliff», Biden’s relationship with McConnell again proved important as the two negotiated a deal that led to the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 being passed at the start of 2013.[243][244] It made many of the Bush tax cuts permanent but raised rates on upper income levels.[244]

Second term (2013–2017)

Official vice president portrait, 2013

Biden was inaugurated to a second term on January 20, 2013, at a small ceremony at Number One Observatory Circle, his official residence, with Justice Sonia Sotomayor presiding (a public ceremony took place on January 21).[245]

Biden played little part in discussions that led to the October 2013 passage of the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014, which resolved the federal government shutdown of 2013 and the debt-ceiling crisis of 2013. This was because Senate majority leader Harry Reid and other Democratic leaders cut him out of any direct talks with Congress, feeling Biden had given too much away during previous negotiations.[246][247][248]

Biden’s Violence Against Women Act was reauthorized again in 2013. The act led to related developments, such as the White House Council on Women and Girls, begun in the first term, as well as the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, begun in January 2014 with Biden and Valerie Jarrett as co-chairs.[249][250]

Biden favored arming Syria’s rebel fighters.[251] As Iraq fell apart during 2014, renewed attention was paid to the Biden-Gelb Iraqi federalization plan of 2006, with some observers suggesting Biden had been right all along.[252][253] Biden himself said the U.S. would follow ISIL «to the gates of hell».[254] Biden had close relationships with several Latin American leaders and was assigned a focus on the region during the administration; he visited the region 16 times during his vice presidency, the most of any president or vice president.[255] In August 2016, Biden visited Serbia, where he met with Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić and expressed his condolences for civilian victims of the bombing campaign during the Kosovo War.[256]

Biden never cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate, making him the longest-serving vice president with this distinction.[257]

Biden with Vice President-elect Mike Pence on November 10, 2016

Role in the 2016 presidential campaign

During his second term, Biden was often said to be preparing for a possible bid for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination.[258] With his family, many friends, and donors encouraging him in mid-2015 to enter the race, and with Hillary Clinton’s favorability ratings in decline at that time, Biden was reported to again be seriously considering the prospect and a «Draft Biden 2016» PAC was established.[258][259][260] By late 2015, Biden was still uncertain about running. He felt his son’s recent death had largely drained his emotional energy, and said, «nobody has a right … to seek that office unless they’re willing to give it 110% of who they are.»[261] On October 21, speaking from a podium in the Rose Garden with his wife and Obama by his side, Biden announced his decision not to run for president in 2016.[262][263][264] In January 2016, Biden affirmed that it was the right decision, but said he regretted not running for president «every day».[265]

Subsequent activities (2017–2019)

After leaving the vice presidency, Biden became an honorary professor at the University of Pennsylvania, developing the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement.[266] He also continued to lead efforts to find treatments for cancer.[267] In 2017, he wrote a memoir, Promise Me, Dad, and went on a book tour.[268] Biden earned $15.6 million from 2017 to 2018.[269] In 2018, he gave a eulogy for Senator John McCain, praising McCain’s embrace of American ideals and bipartisan friendships.[270] Biden was targeted by two pipe bombs that were mailed to him during the October 2018 mail bombing attempts.[271][272]

Biden remained in the public eye, endorsing candidates while continuing to comment on politics, climate change, and the presidency of Donald Trump.[273][274][275] He also continued to speak out in favor of LGBT rights, continuing advocacy on an issue he had become more closely associated with during his vice presidency.[276][277] By 2019, Biden and his wife reported that their assets had increased to[clarification needed] between $2.2 million and $8 million from speaking engagements and a contract to write a set of books.[278]

2020 presidential campaign

Speculation and announcement

Biden at his presidential kickoff rally in Philadelphia, May 2019

Between 2016 and 2019, media outlets often mentioned Biden as a likely candidate for president in 2020.[279] When asked if he would run, he gave varied and ambivalent answers, saying «never say never».[280] A political action committee known as Time for Biden was formed in January 2018, seeking Biden’s entry into the race.[281] He finally launched his campaign on April 25, 2019,[282] saying he was prompted to run, among other reasons, by his «sense of duty.»[283]

Campaign

In September 2019, it was reported that Trump had pressured Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy to investigate alleged wrongdoing by Biden and his son Hunter Biden.[284] Despite the allegations, no evidence was produced of any wrongdoing by the Bidens.[285][286][287] The media widely interpreted this pressure to investigate the Bidens as trying to hurt Biden’s chances of winning the presidency, resulting in a political scandal[288][289] and Trump’s impeachment by the House of Representatives.

In March 2019 and April 2019, eight women accused Biden of previous instances of inappropriate physical contact, such as embracing, touching or kissing.[290] Biden had previously called himself a «tactile politician» and admitted this behavior has caused trouble for him.[291] In April 2019, Biden pledged to be more «respectful of people’s personal space».[292]

Biden at a rally on the eve of the Iowa caucuses, February 2020

Throughout 2019, Biden stayed generally ahead of other Democrats in national polls.[293][294] Despite this, he finished fourth in the Iowa caucuses, and eight days later, fifth in the New Hampshire primary.[295][296] He performed better in the Nevada caucuses, reaching the 15% required for delegates, but still finished 21.6 percentage points behind Bernie Sanders.[297] Making strong appeals to Black voters on the campaign trail and in the South Carolina debate, Biden won the South Carolina primary by more than 28 points.[298] After the withdrawals and subsequent endorsements of candidates Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, he made large gains in the March 3 Super Tuesday primary elections. Biden won 18 of the next 26 contests, putting him in the lead overall.[299] Elizabeth Warren and Mike Bloomberg soon dropped out, and Biden expanded his lead with victories over Sanders in four states on March 10.[300]

In late March 2020, Tara Reade, one of the eight women who in 2019 had accused Biden of inappropriate physical contact, accused Biden of having sexually assaulted her in 1993.[301] There were inconsistencies between Reade’s 2019 and 2020 allegations.[301][302] Biden and his campaign denied the sexual assault allegation.[303][304]

When Sanders suspended his campaign on April 8, 2020, Biden became the Democratic Party’s presumptive nominee for president.[305] On April 13, Sanders endorsed Biden in a live-streamed discussion from their homes.[306] Former President Barack Obama endorsed Biden the next day.[307] On August 11, he announced U.S. Senator Kamala Harris of California as his running mate, making her the first African American and first South Asian American vice-presidential nominee on a major-party ticket.[308] On August 18, 2020, Biden was officially nominated at the 2020 Democratic National Convention as the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 2020 election.[309][310]

Presidential transition

Biden was elected the 46th president of the United States in November 2020. He defeated the incumbent, Donald Trump, becoming the first candidate to defeat a sitting president since Bill Clinton defeated George H. W. Bush in 1992. Trump refused to concede, insisting the election had been «stolen» from him through «voter fraud», challenging the results in court and promoting numerous conspiracy theories about the voting and vote-counting processes, in an attempt to overturn the election results.[311] Biden’s transition was delayed by several weeks as the White House ordered federal agencies not to cooperate.[312] On November 23, General Services Administrator Emily W. Murphy formally recognized Biden as the apparent winner of the 2020 election and authorized the start of a transition process to the Biden administration.[313]

On January 6, 2021, during Congress’ electoral vote count, Trump told supporters gathered in front of the White House to march to the Capitol, saying, «We will never give up. We will never concede. It doesn’t happen. You don’t concede when there’s theft involved.»[314] Soon after, they attacked the Capitol. During the insurrection at the Capitol, Biden addressed the nation, calling the events «an unprecedented assault unlike anything we’ve seen in modern times.»[315][316] After the Capitol was cleared, Congress resumed its joint session and officially certified the election results with Vice President Mike Pence, in his capacity as President of the Senate, declaring Biden and Harris the winners.[317]

Presidency (2021–present)

Inauguration

Biden was inaugurated as the 46th president of the United States on January 20, 2021.[318] At 78, he is the oldest person to have assumed the office.[318] He is the second Catholic president (after John F. Kennedy)[319] and the first president whose home state is Delaware.[320] He is also the first man since George H. W. Bush to have been both vice president and president, and the second non-incumbent vice president (after Richard Nixon in 1968) to be elected president.[321] He is also the first president from the Silent Generation.[322]

Biden’s inauguration was «a muted affair unlike any previous inauguration» due to COVID-19 precautions as well as massively increased security measures because of the January 6 United States Capitol attack. Trump did not attend, becoming the first outgoing president since 1869 to not attend his successor’s inauguration.[323]

2021

In his first two days as president, Biden signed 17 executive orders. By his third day, orders had included rejoining the Paris Climate Agreement, ending the state of national emergency at the border with Mexico, directing the government to rejoin the World Health Organization, face mask requirements on federal property, measures to combat hunger in the United States,[324][325][326][327] and revoking permits for the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline.[328][329][330] In his first two weeks in office, Biden signed more executive orders than any other president since Franklin D. Roosevelt had in their first month in office.[331]

On February 4, 2021, the Biden administration announced that the United States was ending its support for the Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen.[332]

On March 11, the first anniversary of COVID-19 being declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization, Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, a $1.9 trillion economic stimulus relief package he proposed and lobbied for that aimed to speed up the United States’ recovery from the economic and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing recession.[333] The package included direct payments to most Americans, an extension of increased unemployment benefits, funds for vaccine distribution and school reopenings, and expansions of health insurance subsidies and the child tax credit. Biden’s initial proposal included an increase of the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour, but after the Senate parliamentarian determined that including the increase in a budget reconciliation bill would violate Senate rules, Democrats declined to pursue overruling her and removed the increase from the package.[334][335][336]

Also in March, amid a rise in migrants entering the U.S. from Mexico, Biden told migrants, «Don’t come over.» In the meantime, migrant adults «are being sent back», Biden said, in reference to the continuation of the Trump administration’s Title 42 policy for quick deportations.[337] Biden earlier announced that his administration would not deport unaccompanied migrant children; the rise in arrivals of such children exceeded the capacity of facilities meant to shelter them (before they were sent to sponsors), leading the Biden administration in March to direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help.[338]

On April 14, Biden announced that the United States would delay the withdrawal of all troops from the war in Afghanistan until September 11, signaling an end to the country’s direct military involvement in Afghanistan after nearly 20 years.[339] In February 2020, the Trump administration had made a deal with the Taliban to completely withdraw U.S. forces by May 1, 2021.[340] Biden’s decision met with a wide range of reactions, from support and relief to trepidation at the possible collapse of the Afghan government without American support.[341] On April 22–23, Biden held an international climate summit at which he announced that the U.S. would cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 50%–52% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. Other countries also increased their pledges.[342][343] On April 28, the eve of his 100th day in office, Biden delivered his first address to a joint session of Congress.[344]

In May 2021, during a flareup in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Biden expressed his support for Israel, saying «my party still supports Israel».[345] In June 2021, Biden took his first trip abroad as president. In eight days he visited Belgium, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. He attended a G7 summit, a NATO summit, and an EU summit, and held one-on-one talks with Russian president Vladimir Putin.[346]

On June 17, Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act, which officially declared Juneteenth a federal holiday.[347] Juneteenth is the first new federal holiday since 1986.[348] In July 2021, amid a slowing of the COVID-19 vaccination rate in the country and the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, Biden said that the country has «a pandemic for those who haven’t gotten the vaccination» and that it was therefore «gigantically important» for Americans to be vaccinated.[349] In September 2021, Biden announced AUKUS, a security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, to ensure «peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific over the long term»; the deal included nuclear-powered submarines built for Australia’s use.[350]

By the end of 2021, 40 of Biden’s appointed judges to the federal judiciary had been confirmed, more than any president in their first year in office since Ronald Reagan.[351] Biden has prioritized diversity in his judicial appointments more than any president in U.S. history, with the majority of appointments being women and people of color.[352] Most of his appointments have been in blue states, making a limited impact since the courts in these states already traditionally lean liberal.[353]

In the first eight months of his presidency, Biden’s approval rating, according to Morning Consult polling, remained above 50%. In August, it began to decline and lowered into the low forties by December.[354] The decline in his approval is attributed to the Afghanistan withdrawal, increasing hospitalizations from the Delta variant, high inflation and gas prices, disarray within the Democratic Party, and a general decline in popularity customary in politics.[355][356][357][358]

Biden entered office nine months into a recovery from the COVID-19 recession and his first year in office was characterized by robust growth in real GDP, employment, wages and stock market returns, amid significantly elevated inflation. Real GDP grew 5.7%, the fastest rate in 37 years.[359] Amid record job creation, the unemployment rate fell at the fastest pace on record during the year.[360][361] By the end of 2021, inflation reached a nearly 40-year high of 7.1%, which was partially offset by the highest nominal wage and salary growth in at least 20 years.[362][363][364][365]

Withdrawal from Afghanistan

American forces began withdrawing from Afghanistan in 2020, under the provisions of a February 2020 US-Taliban agreement that set a May 1, 2021, deadline.[366] The Taliban began an offensive on May 1.[367][368] By early July, most American troops in Afghanistan had withdrawn.[340] Biden addressed the withdrawal in July, saying, «The likelihood there’s going to be the Taliban overrunning everything and owning the whole country is highly unlikely.»[340]

On August 15, the Afghan government collapsed under the Taliban offensive, and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country.[340][369] Biden reacted by ordering 6,000 American troops to assist in the evacuation of American personnel and Afghan allies.[370] He faced bipartisan criticism for the manner of the withdrawal,[371] with the evacuation of Americans and Afghan allies described as chaotic and botched.[372][373][374] On August 16, Biden addressed the «messy» situation, taking responsibility for it, and admitting that the situation «unfolded more quickly than we had anticipated».[369][375] He defended his decision to withdraw, saying that Americans should not be «dying in a war that Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves».[375][376]

On August 26, a suicide bombing at the Kabul airport killed 13 U.S. service members and 169 Afghans. On August 27, an American drone strike killed two ISIS-K targets, who were «planners and facilitators», according to a U.S. Army general.[377] On August 29, another American drone strike killed 10 civilians, including seven children; the Defense Department initially claimed the strike was conducted on an Islamic State suicide bomber threatening Kabul Airport, but admitted the mistake on September 17 and apologized.[378]

The U.S. military completed withdrawal from Afghanistan on August 30, with Biden saying that the evacuation effort was an «extraordinary success», by extracting over 120,000 Americans, Afghans and other allies.[379] He acknowledged that between «100 to 200» Americans who wanted to leave were left in Afghanistan, despite his August 18 pledge to stay in Afghanistan until all Americans who wanted to leave had left.[380]

Infrastructure and climate

As part of Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, in late March 2021, he proposed the American Jobs Plan, a $2 trillion package addressing issues including transport infrastructure, utilities infrastructure, broadband infrastructure, housing, schools, manufacturing, research and workforce development.[381][382] After months of negotiations among Biden and lawmakers, in August 2021 the Senate passed a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill called the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act,[383][384] while the House, also in a bipartisan manner, approved that bill in early November 2021, covering infrastructure related to transport, utilities, and broadband.[385] Biden signed the bill into law in mid-November 2021.[386]

The other core part of the Build Back Better agenda was the Build Back Better Act, a $3.5 trillion social spending bill that expands the social safety net and includes major provisions on climate change.[387][388] The bill did not have Republican support, so Democrats attempted to pass it on a party-line vote through budget reconciliation, but struggled to win the support of Senator Joe Manchin, even as the price was lowered to $2.2 trillion.[389] After Manchin rejected the bill,[390] the Build Back Better Act’s size was reduced and comprehensively reworked into the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, covering deficit reduction, climate change, healthcare, and tax reform.[391]

Before and during the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21), Biden promoted an agreement that the U.S. and the European Union cut methane emissions by a third by 2030 and tried to add dozens of other countries to the effort.[392] He tried to convince China[393] and Australia[394] to do more. He convened an online Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate Change to press other countries to strengthen their climate policy.[395][396] Biden pledged to double climate funding to developing countries by 2024.[397] Also at COP26, the U.S. and China reached a deal on greenhouse gas emission reduction. The two countries are responsible for 40% of global emissions.[398]

2022

In early 2022, Biden made efforts to change his public image after entering the year with low approval ratings due to inflation and high gas prices, which continued to fall to approximately 40% in aggregated polls by February.[399][400][401] He began the year by endorsing a change to the Senate filibuster to allow for the passing of the Freedom to Vote Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Act, on both of which the Senate had failed to invoke cloture.[402] The rules change failed when two Democratic senators, Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, joined Senate Republicans in opposing it.[403]

Nomination of Ketanji Brown Jackson

In January, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, a moderate liberal nominated by Bill Clinton, announced his intention to retire from the Supreme Court. During his 2020 campaign, Biden vowed to nominate the first Black woman to the Supreme Court if a vacancy occurred,[404] a promise he reiterated after the announcement of Breyer’s retirement.[405] On February 25, Biden nominated federal judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court.[406] She was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on April 7[407] and sworn in on June 30.[408]

Foreign policy

In early February, Biden ordered the counterterrorism raid in northern Syria that resulted in the death of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, the second leader of the Islamic State.[409] In late July, Biden approved the drone strike that killed Ayman al-Zawahiri, the second leader of Al-Qaeda, and an integral member in the planning of the September 11 attacks.[410]

Also in February, after warning for several weeks that an attack was imminent, Biden led the U.S. response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, imposing severe sanctions on Russia and authorizing over $8 billion in weapons shipments to Ukraine.[411][412][413] On April 29, Biden asked Congress for $33 billion for Ukraine,[414] but lawmakers later increased it to about $40 billion.[415] Biden blamed Vladimir Putin for the emerging energy and food crises,[416] saying, «Putin’s war has raised the price of food because Ukraine and Russia are two of the world’s major bread baskets for wheat and corn, the basic product for so many foods around the world.»[417]

China’s assertiveness, particularly in the Pacific, remained a challenge for Biden. The Solomon Islands-China security pact caused alarm, as China could build military bases across the South Pacific. Biden sought to strengthen ties with Australia and New Zealand in the wake of the deal, as Anthony Albanese succeeded to the premiership of Australia and Jacinda Ardern’s government took a firmer line on Chinese influence.[418][419][420] On September 18, 2022, Reuters reported that «Joe Biden said U.S. forces would defend Taiwan in the event of a Chinese invasion, his most explicit statement on the issue, drawing an angry response from China that said it sent the wrong signal to those seeking an independent Taiwan.» The policy was stated in contrast to Biden’s previous exclusion of boots-on-the-ground and planes-in-the-air for U.S. support for Ukraine in its conflict with Russia.[421] In late 2022, Biden issued several executive orders and federal rules designed to slow Chinese technological growth, and maintain U.S. leadership over computing, biotech, and clean energy.[422]

Biden with Arab leaders at the GCC+3 summit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on July 16, 2022

The 2022 OPEC+ oil production cut caused a diplomatic spat with Saudi Arabia, widening the rift between the two countries, and threatening a longstanding alliance.[423][424]

COVID-19 diagnosis

On July 21, 2022, Biden tested positive for COVID-19 with reportedly mild symptoms.[425] According to the White House, he was treated with Paxlovid.[426] He worked in isolation in the White House for five days[427] and returned to isolation when he tested positive again on July 30.[428]

Domestic policy

In April 2022, Biden signed into law the bipartisan Postal Service Reform Act of 2022 to revamp the finances and operations of the United States Postal Service agency.[429]

On July 28, 2022, the Biden administration announced it would fill four wide gaps on the Mexico–United States border in Arizona near Yuma, an area with some of the busiest corridors for illegal crossings. During his presidential campaign, Biden had pledged to cease all future border wall construction.[430] This occurred after both allies and critics of Biden criticized his administration’s management of the southern border.[431]

In the summer of 2022, several other pieces of legislation Biden supported passed Congress. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act aimed to address gun reform issues following the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas.[432] The gun control laws in the bill include extended background checks for gun purchasers under 21, clarification of Federal Firearms License requirements, funding for state red flag laws and other crisis intervention programs, further criminalization of arms trafficking and straw purchases, and partial closure of the boyfriend loophole.[433][434][435] Biden signed the bill on June 25, 2022.[436]

The Honoring our PACT Act of 2022 was introduced in 2021, and signed into law by Biden on August 10, 2022.[437] The act intends to significantly improve healthcare access and funding for veterans who were exposed to toxic substances during military service, including burn pits.[438] The bill gained significant media coverage due to the activism of comedian Jon Stewart.[439]

Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act into law on August 9, 2022.[440] The act provides billions of dollars in new funding to boost domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors in the United States, to compete economically with China.[441]

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was introduced by Senators Chuck Schumer and Joe Manchin, resulting from continuing negotiations on Biden’s initial Build Back Better agenda, which Manchin had blocked the previous year.[442][443] The package aimed to raise $739 billion and authorize $370 billion in spending on energy and climate change, $300 billion in deficit reduction, three years of Affordable Care Act subsidies, prescription drug reform to lower prices, and tax reform.[444] According to an analysis by the Rhodium Group, the bill will lower US greenhouse gas emissions between 31% and 44% below 2005 levels by 2030.[445] On August 7, 2022, the Senate passed the bill (as amended) on a 51–50 vote, with all Democrats voting in favor, all Republicans opposed, and Vice President Kamala Harris breaking the tie. The bill was passed by the House on August 12[445] and was signed by Biden on August 16.[446][447]

On October 6, 2022, Biden pardoned all Americans convicted of small amounts of marijuana possession under federal law.[448]

On December 13, 2022, Biden signed the Respect for Marriage Act, which repealed the Defense of Marriage Act and requires the federal government to recognize the validity of same-sex and interracial marriages in the United States.[449]

2022 elections

On September 2, 2022, in a nationally broadcast Philadelphia speech, Biden called for a «battle for the soul of the nation». Off camera, he called active Trump supporters «semi-fascists», which Republican commentators denounced.[450][451][452] A predicted Republican wave election did not materialize and the race for U.S. Congress control was much closer than expected, with Republicans securing a slim majority of 222 seats in the House of Representatives,[453][454][455][456] and Democrats keeping control of the U.S. Senate, with 51 seats, a gain of one seat from the last Congress.[457][n 3]

It was the first midterm election since 1986 in which the party of the incumbent president achieved a net gain in governorships, and the first since 1934 in which the president’s party lost no state legislative chambers.[459] Democrats credited Biden for their unexpectedly favorable performance,[460] and he celebrated the results as a strong day for democracy.[461]

Political positions

Mikhail Gorbachev (right) being introduced to President Obama by Joe Biden, March 2009. U.S. ambassador to Russia, Michael McFaul, is pictured in the background.

Biden is considered a moderate Democrat[462] and a centrist.[463][464] Throughout his long career, his positions have been aligned with the center of the Democratic Party.[465] In 2022, journalist Sasha Issenberg wrote that Biden’s «most valuable political skill» was «an innate compass for the ever-shifting mainstream of the Democratic party.»[466]

Biden has proposed partially reversing the corporate tax cuts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, saying that doing so would not hurt businesses’ ability to hire.[467][468] He voted for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)[469] and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[470] Biden is a staunch supporter of the Affordable Care Act (ACA).[471][472] He has promoted a plan to expand and build upon it, paid for by revenue gained from reversing some Trump administration tax cuts.[471] Biden’s plan aims to expand health insurance coverage to 97% of Americans, including by creating a public health insurance option.[473]

Biden has supported same-sex marriage since 2012[474][475] and also supports Roe v. Wade and repealing the Hyde Amendment.[476][477] He opposes drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.[478] As a senator, he forged deep relationships with police groups and was a chief proponent of a Police Officer’s Bill of Rights measure that police unions supported but police chiefs opposed.[479][480] In 2020, Biden also ran on decriminalizing cannabis,[481] after zealously advocating the War on Drugs as a U.S. senator.[482][better source needed]

Biden believes action must be taken on global warming. As a senator, he co-sponsored the Boxer–Sanders Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act, the most stringent climate bill in the United States Senate.[483] He wants to achieve a carbon-free power sector in the U.S. by 2035 and stop emissions completely by 2050.[484] His program includes reentering the Paris Agreement, nature conservation, and green building.[485]

Biden has said the U.S. needs to «get tough» on China, calling China the «most serious competitor» that poses challenges to the United States’ «prosperity, security, and democratic values».[486] Biden has spoken about human rights abuses in the Xinjiang region to the Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping, pledging to sanction and commercially restrict Chinese government officials and entities who carry out repression.[488][489]

Biden has said he is against regime change, but for providing non-military support to opposition movements.[490] He opposed direct U.S. intervention in Libya,[491][214] voted against U.S. participation in the Gulf War,[492] voted in favor of the Iraq War,[493] and supports a two-state solution in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[494] Biden has pledged to end U.S. support for the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen and to reevaluate the United States’ relationship with Saudi Arabia.[274] Biden supports extending the New START arms control treaty with Russia to limit the number of nuclear weapons deployed by both sides.[495][496] In 2021, Biden recognized the Armenian genocide, becoming the first U.S. president to do so.[497]

Reputation

Biden was consistently ranked one of the least wealthy members of the Senate,[498][499][500] which he attributed to his having been elected young.[501] Feeling that less-wealthy public officials may be tempted to accept contributions in exchange for political favors, he proposed campaign finance reform measures during his first term.[98] As of November 2009, Biden’s net worth was $27,012.[502] By November 2020, the Bidens were worth $9 million, largely due to sales of Biden’s books and speaking fees after his vice presidency.[503][504][505][506]

The political writer Howard Fineman has written, «Biden is not an academic, he’s not a theoretical thinker, he’s a great street pol. He comes from a long line of working people in Scranton—auto salesmen, car dealers, people who know how to make a sale. He has that great Irish gift.»[43] Political columnist David S. Broder wrote that Biden has grown over time: «He responds to real people—that’s been consistent throughout. And his ability to understand himself and deal with other politicians has gotten much much better.»[43] Journalist James Traub has written that «Biden is the kind of fundamentally happy person who can be as generous toward others as he is to himself.»[136]

In recent years, especially after the 2015 death of his elder son Beau, Biden has been noted for his empathetic nature and ability to communicate about grief.[507][508] In 2020, CNN wrote that his presidential campaign aimed to make him «healer-in-chief», while The New York Times described his extensive history of being called upon to give eulogies.[509]

Journalist and TV anchor Wolf Blitzer has described Biden as loquacious.[510] He often deviates from prepared remarks[511] and sometimes «puts his foot in his mouth.»[512][173][513][514] The New York Times wrote that Biden’s «weak filters make him capable of blurting out pretty much anything.»[173] In 2018, Biden called himself «a gaffe machine».[515] Some of his gaffes have been characterized as racially insensitive.[516][517][518][519]

According to The New York Times, Biden often embellishes elements of his life or exaggerates, a trait also noted by The New Yorker in 2014.[520][521] For instance, Biden has claimed to have been more active in the civil rights movement than he actually was, and has falsely recalled being an excellent student who earned three college degrees.[520] The Times wrote, «Mr. Biden’s folksiness can veer into folklore, with dates that don’t quite add up and details that are exaggerated or wrong, the factual edges shaved off to make them more powerful for audiences.»[521]

Electoral history

| Year | Office | Type | Party | Main opponent | Party | Votes for Biden | Result | Swing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | P. | ±% | |||||||||||

| 1970 | Councillor | General | Democratic | Lawrence T. Messick | Republican | 10,573 | 55.41% | 1st | N/A | Won | Gain | |||

| 1972 | U.S. senator | General | Democratic | J. Caleb Boggs (I) | Republican | 116,006 | 50.48% | 1st | +9.59% | Won | Gain | |||

| 1978 | General | Democratic | James H. Baxter Jr. | Republican | 93,930 | 57.96% | 1st | +7.48% | Won | Hold | ||||

| 1984 | General | Democratic | John M. Burris | Republican | 147,831 | 60.11% | 1st | +2.15% | Won | Hold | ||||

| 1988 | President | Primary | Democratic | Michael Dukakis | Democratic | Withdrew | Lost | N/A | ||||||

| 1990 | U.S. senator | General | Democratic | M. Jane Brady | Republican | 112,918 | 62.68% | 1st | +2.57% | Won | Hold | |||

| 1996 | General | Democratic | Raymond J. Clatworthy | Republican | 165,465 | 60.04% | 1st | −2.64% | Won | Hold | ||||

| 2002 | General | Democratic | Raymond J. Clatworthy | Republican | 135,253 | 58.22% | 1st | −1.82% | Won | Hold | ||||

| 2008 | General | Democratic | Christine O’Donnell | Republican | 257,539 | 64.69% | 1st | +6.47% | Won | Hold | ||||

| 2008 | President | Primary | Democratic | Barack Obama | Democratic | Withdrew | Lost | N/A | ||||||

| Vice president | General | Sarah Palin | Republican | 69,498,516 | 52.93% | 1st | +4.66% | Won | Gain | |||||

| Electoral | 365 E.V. | 67.84% | 1st | +21.19% | ||||||||||

| 2012 | General | Democratic | Paul Ryan | Republican | 65,915,795 | 51.06% | 1st | −1.87% | Won | Hold | ||||

| Electoral | 332 E.V. | 61.71% | 1st | −6.13% | ||||||||||

| 2020 | President | Primary | Democratic | Bernie Sanders | Democratic | 19,080,152 | 51.68% | 1st | N/A | Won | N/A | |||

| Convention | 3,558 D. | 74.92% | 1st | N/A | ||||||||||

| General | Donald Trump (I) | Republican | 81,268,924 | 51.31% | 1st | +3.13% | Won | Gain | ||||||

| Electoral | 306 E.V. | 56.88% | 1st | +14.69% |

Publications

See also

- 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries

- 2020 United States presidential debates

- Cabinet of Joe Biden

- List of honors and awards received by Joe Biden

- List of things named after Joe Biden

Notes

- ^ Biden held the chairmanship from January 3 to 20, then was succeeded by Jesse Helms until June 6, and thereafter held the position until 2003.

- ^ Delaware’s Democratic governor, Ruth Ann Minner, announced on November 24, 2008, that she would appoint Biden’s longtime senior adviser Ted Kaufman to succeed Biden in the Senate.[188] Kaufman said he would serve only two years, until Delaware’s special Senate election in 2010.[188] Biden’s son Beau ruled himself out of the 2008 selection process due to his impending tour in Iraq with the Delaware Army National Guard.[189] He was a possible candidate for the 2010 special election, but in early 2010 said he would not run for the seat.[190]

- ^ Kyrsten Sinema, whose seat was not up for election in 2022, left the Democratic Party and became an independent politician in December 2022, after the election but before the swearing in of the next Congress. As a result, 48 Democrats (rather than 49), plus Angus King and Bernie Sanders, independents who caucus with Democrats, were in the Senate upon commencement of the 118th United States Congress, on January 3, 2023. Sinema has ruled out caucusing with Republicans, and she has said she intends to align mostly with Democrats and keep her committee assignments.[458]

References

Citations

- ^ a b United States Congress. «Joseph R. Biden (id: b000444)». Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 5.

- ^ Chase, Randall (January 9, 2010). «Vice President Biden’s mother, Jean, dies at 92». WITN-TV. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (September 3, 2002). «Joseph Biden Sr., 86, father of the senator». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Witcover (2010), p. 9.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan (July 2, 2012). «Joe Biden’s Irish Roots». HuffPost. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^ «Number two Biden has a history over Irish debate». The Belfast Telegraph. November 9, 2008. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ a b Witcover (2010), p. 8.

- ^ «French town’s historic links to Joe Biden’s inauguration». Connexionfrance.com. January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2022.