Как правильно пишется словосочетание «Екатерина Вторая»

Екатери́на Втора́я

Екатери́на Втора́я (Екатери́на II)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: выразитель — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «второе»

Синонимы к слову «екатерина»

Синонимы к слову «втора»

Предложения со словосочетанием «Екатерина Вторая»

- Они мне сказали то же самое. – Здорово! Так это ведь, Екатерина вторая!

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «Екатерина Вторая»

- — Возведи ее на трон, — воскликнул он, — та же Семирамида или Екатерина Вторая! Повиновение крестьян — образцовое… Воспитание детей — образцовое! Голова! Мозги!

- В истории знала только двенадцатый год, потому что mon oncle, prince Serge, [мой дядя, князь Серж (фр.).] служил в то время и делал кампанию, он рассказывал часто о нем; помнила, что была Екатерина Вторая, еще революция, от которой бежал monsieur de Querney, [господин де Керни (фр.).] а остальное все… там эти войны, греческие, римские, что-то про Фридриха Великого — все это у меня путалось.

- С тех пор как Екатерина Вторая построила на островской набережной Большой Невы храм свободным художествам, заведение это выпустило самое ограниченное число замечательных талантов и довольно значительное число посредственности, дававшей некогда какие-то задатки, а потом бесследно заглохшей.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «втора»

-

ВТО́РА, -ы, ж. Второй голос в музыкальной партии; вторая скрипка. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ВТОРА

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «втора»

- В поэзии есть два момента: первый — очарованность, влюбленность, одухотворенность; второй — сладострастие, чувственность.

- Отличие истинного поэта от ремесленника в том, что если первый приходит в сильное возбуждение только от действительных ценностей, то второй готов сочинительствовать по всякому поводу.

- Да когда же, во-первых, бывало, во все эти тысячелетия, чтоб человек действовал только из одной своей собственной выгоды? Что же делать с миллионами фактов, свидетельствующих об том, как люди зазнамо, то есть вполне понимая свои настоящие выгоды, отставляли их на второй план и бросались на другую дорогу, на риск, на авось, никем и ничем не принуждаемые к тому, а как будто именно только не желая указанной дороги, и упрямо, своевольно пробивали другую, трудную, нелепую, отыскивая ее чуть не в потемках. Ведь это значит, им действительно это упрямство и своеволие было приятнее всякой выгоды…

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

| Екатерина II Великая | |

|

|

|

8-я императрица всероссийская |

|

|---|---|

| 28 июня (9 июля) 1762 — 6 (17 ноября) 1796 | |

| Коронация: | 1 (12 сентября) 1762 |

| Предшественник: | Пётр III |

| Преемник: | Павел I |

| Рождение: | 21 апреля (2 мая) 1729 Штеттин, (Пруссия[1]). |

| Смерть: | 6 (17 ноября) 1796 Зимний дворец[2], Петербург |

| Похоронена: | Петропавловский собор, Петербург |

| Династия: | Аскании (по рождению)/ Романовы (по браку) |

| Отец: | Христиан-Август Ангальт-Цербстский |

| Мать: | Иоганна-Елизавета Гольштейн-Готторпская |

| Супруг: | Пётр III |

| Дети: | Павел I Петрович Анна Петровна Алексей Григорьевич Бобринский Елизавета Григорьевна Тёмкина |

| Автограф: |  |

|

Екатерина II Великая на Викискладе |

Екатери́на II Великая (Екатерина Алексе́евна, нем. Sophie Auguste Friederike von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg) — 21 апреля (2 мая) 1729, Штеттин, Пруссия — 6 (17) ноября 1796, Зимний дворец, Петербург) — императрица всероссийская (1762—1796). Период её правления часто считают «золотым веком» Российской империи.

Содержание

- 1 Происхождение

- 2 Детство, образование и воспитание

- 3 Брак с наследником российского престола

- 4 Переворот 28 июня 1762 года

- 5 Правление Екатерины II: общие сведения

- 6 Внутренняя политика

- 6.1 Уложенная комиссия

- 6.2 Императорский совет и преобразование Сената

- 6.3 Губернская реформа

- 6.4 Ликвидация Запорожской Сечи

- 6.5 Начало присоединения Калмыцкого ханства

- 6.6 Областная реформа в Эстляндии и Лифляндии

- 6.7 Губернская реформа в Сибири и Среднем Поволжье

- 6.8 Экономическая политика

- 6.9 Социальная политика

- 6.10 Национальная политика

- 6.11 Законодательство о сословиях

- 6.12 Религиозная политика

- 6.13 Внутриполитические проблемы

- 6.14 Крестьянская война 1773—1775 годов

- 6.15 Масонство, Дело Новикова, Дело Радищева

- 7 Внешняя политика России в царствование Екатерины II

- 7.1 Расширение пределов Российской империи

- 7.2 Разделы Польши

- 7.3 Русско-турецкие войны. Присоединение Крыма

- 7.4 Отношения с Грузией. Георгиевский трактат

- 7.5 Отношения со Швецией

- 7.6 Отношения с другими странами

- 8 Екатерина II как деятель Эпохи Просвещения

- 8.1 Екатерина — литератор и издатель

- 8.2 Екатерина — меценат и коллекционер

- 8.3 Развитие культуры и искусства

- 9 Двор времён Екатерины II

- 9.1 Особенности личной жизни

- 10 Знаменитые деятели екатерининской эпохи

- 11 Екатерина в искусстве

- 11.1 В кино

- 11.2 В театре

- 11.3 В литературе

- 11.4 В изобразительном искусстве

- 12 Память

- 13 Памятники

- 14 См. также

- 15 Ссылки

- 16 Литература

- 17 Примечания

Происхождение

Родилась София Фредерика Августа Ангальт-Цербстская 21 апреля (2 мая) 1729 года в немецком померанском городе Штеттин (ныне Щецин в Польше). Отец происходил из цербст-дорнбургской линии ангальтского дома и состоял на службе у прусского короля, был полковым командиром, комендантом, затем губернатором города Штеттина, баллотировался в Курляндские герцоги, но неудачно, службу закончил прусским фельдмаршалом. Мать — из рода Гольштейн-Готторп, приходилась двоюродной теткой будущему Петру III. Дядя по материнской линии Адольф-Фридрих (Адольф Фредрик) с 1751 года был королём Швеции (избран наследником в 1743 г.). Родословная матери Екатерины II восходит к Кристиану I, королю Дании, Норвегии и Швеции, первому герцогу Шлезвиг-Голштейнскому и основателю династии Ольденбургов.

Детство, образование и воспитание

Семья герцога Цербстского была небогатой, Екатерина получила домашнее образование. Обучалась немецкому и французскому языкам, танцам, музыке, основам истории, географии, богословия. Воспитывалась в строгости. Росла любознательной, склонной к подвижным играм, настойчивой.

В 1744 году российской императрицей Елизаветой Петровной вместе с матерью была приглашена в Россию для последующего сочетания браком с наследником престола великим князем Петром Фёдоровичем, будущим императором Петром III и её троюродным братом. Сразу после приезда в Россию стала изучать русский язык, историю, православие, русские традиции, так как стремилась наиболее полно ознакомиться с Россией, которую воспринимала как новую родину. Среди её учителей выделяют известного проповедника Симона Тодорского (учитель православия), автора первой русской грамматики Василия Ададурова (учитель русского языка) и балетмейстера Ланге (учитель танцев). Вскоре она заболела воспалением лёгких, и состояние её было столь тяжёлым, что её мать предложила привести лютеранского пастора. София, однако, отказалась и послала за Симоном Тодорским. Это обстоятельство прибавило ей популярности при русском дворе[3]. 28 июня (9 июля) 1744 София Фредерика Августа перешла из лютеранства в православие и получила имя Екатерины Алексеевны (то же имя и отчество, что и у матери Елизаветы — Екатерины I), а на следующий день была обручена с будущим императором.

Брак с наследником российского престола

Екатерина в молодости

21 августа (1 сентября) 1745 года в шестнадцатилетнем возрасте Екатерина была обвенчана с Петром Фёдоровичем, которому исполнилось 17 лет. Первые годы жизни Пётр совершенно не интересовался женой, и супружеских отношений между ними не существовало. Об этом Екатерина позже напишет:

Я очень хорошо видела, что великий князь меня совсем не любит; через две недели после свадьбы он мне сказал, что влюблен в девицу Карр, фрейлину императрицы. Он сказал графу Дивьеру, своему камергеру, что не было и сравнения между этой девицей и мною. Дивьер утверждал обратное, и он на него рассердился; эта сцена происходила почти в моем присутствии, и я видела эту ссору. Правду сказать, я говорила самой себе, что с этим человеком я непременно буду очень несчастной, если и поддамся чувству любви к нему, за которое так плохо платили, и что будет с чего умереть от ревности безо всякой для кого бы то ни было пользы.

Итак, я старалась из самолюбия заставить себя не ревновать к человеку, который меня не любит, но, чтобы не ревновать его, не было иного выбора, как не любить его. Если бы он хотел быть любимым, это было бы для меня нетрудно: я от природы была склонна и привычна исполнять свои обязанности, но для этого мне нужно было бы иметь мужа со здравым смыслом, а у моего этого не было. [4]

Екатерина продолжает заниматься самообразованием. Она читает книги по истории, философии, юриспруденции, сочинения Вольтера, Монтескье, Тацита, Бейля, большое количество другой литературы. Основным развлечением для неё стала охота, верховая езда, танцы и маскарады. Отсутствие супружеских отношений с великим князем способствовало появлению у Екатерины любовников. Между тем, императрица Елизавета высказывала недовольство отсутствием детей у супругов.

Наконец, после двух неудачных беременностей, 20 сентября (1 октября) 1754 году Екатерина родила сына, которого у неё сразу забирают, называют Павлом (будущий император Павел I) и лишают возможности воспитывать, а позволяют только изредка видеть. Ряд источников утверждает, что истинным отцом Павла был любовник Екатерины С. В. Салтыков. Другие — что такие слухи лишены оснований, и что Петру была сделана операция, устранившая дефект, делавший невозможным зачатие. Вопрос об отцовстве вызывал интерес и у общества.

Павел I Петрович, сын Екатерины (1777)

После рождения Павла отношения с Петром и Елизаветой Петровной окончательно испортились. Пётр открыто заводил любовниц, впрочем, не препятствуя делать это и Екатерине, у которой в этот период возникла связь с Станиславом Понятовским — будущим королём Польши. 9 (20) декабря 1758 года Екатерина родила дочь Анну, что вызвало сильное недовольство Петра, произнёсшего при известии о новой беременности: «Бог знает, откуда моя жена беременеет; я не знаю наверное, мой ли этот ребенок и должен ли я признавать его своим». В это время ухудшилось состояние Елизаветы Петровны. Всё это делало реальной перспективу высылки Екатерины из России или заключения её в монастырь[5]. Ситуацию усугубляло то, что вскрылась тайная переписка Екатерины с опальным фельдмаршалом Апраксиными и английским послом Вильямсом, посвящённая политическим вопросам. Её прежние фавориты были удалены, но начал формироваться круг новых: Григорий Орлов, Дашкова и другие.

Смерть Елизаветы Петровны (25 декабря 1761 (5 января 1762)) и восшествие на престол Петра Фёдоровича под именем Петра III ещё больше отдалили супругов. Пётр III стал открыто жить с любовницей Елизаветой Воронцовой, поселив жену в другом конце Зимнего дворца. Когда Екатерина забеременела от Орлова это уже нельзя было объяснить случайным зачатием от мужа, так как общение супругов прекратилось к тому времени совершенно. Беременность свою Екатерина скрывала, а когда пришло время рожать, её преданный камердинер Василий Григорьевич Шкурин поджёг свой дом. Любитель подобных зрелищ Пётр с двором ушли из дворца посмотреть на пожар; в это время Екатерина благополучно родила. Так появился на свет божий первый на Руси граф Бобринский — основатель известной фамилии.

Переворот 28 июня 1762 года

-

Основная статья: Переворот 28 июня 1762 года

Вступив на трон, Пётр III осуществил ряд действий, вызвавших отрицательное отношение к нему офицерского корпуса. Так, он заключил невыгодный для России договор с Пруссией (в то время, как русские войска взяли Берлин) и вернул ей захваченные русскими земли. Одновременно он намерился в союзе с Пруссией выступить против Дании (союзницы России), с целью вернуть отнятый ею у Гольштейна Шлезвиг, причём сам намеревался выступить в поход во главе гвардии. Сторонники переворота обвиняли Петра III также в невежестве, слабоумии, нелюбви к России, полной неспособности к правлению. На его фоне выгодно смотрелась Екатерина — умная, начитанная, благочестивая и доброжелательная супруга, подвергающаяся преследованиям мужа.

После того, как отношения с мужем окончательно испортились, и усилилось недовольство императором со стороны гвардии, Екатерина решилась участвовать в перевороте. Её соратники, основными из которых были братья Орловы, Потёмкин и Хитрово, занялись агитацией в гвардейских частях и склонили их на свою сторону. Непосредственной причиной начала переворота стали слухи об аресте Екатерины и раскрытие и арест одного из участников заговора — поручика Пассека.

Ранним утром 28 июня (9 июля) 1762 года, пока Пётр III находился в Ораниенбауме, Екатерина в сопровождении Алексея и Григория Орловых приехала из Петергофа в Санкт-Петербург, где ей присягнули на верность гвардейские части. Пётр III, видя безнадёжность сопротивления, на следующий день отрёкся от престола, был взят под стражу и в первых числах июля погиб при невыясненных обстоятельствах.

2 (13 сентября) 1762 года Екатерина Алексеевна была коронована в Москве и стала императрицей всероссийской с именем Екатерина II.

Правление Екатерины II: общие сведения

В своих мемуарах Екатерина так характеризовала состояние России в начале своего царствования:

Финансы были истощены. Армия не получала жалованья за 3 месяца. Торговля находилась в упадке, ибо многие ее отрасли были отданы в монополию. Не было правильной системы в государственном хозяйстве. Военное ведомство было погружено в долги; морское едва держалось, находясь в крайнем пренебрежении. Духовенство было недовольно отнятием у него земель. Правосудие продавалось с торгу, и законами руководствовались только в тех случаях, когда они благоприятствовали лицу сильному

Императрица так сформулировала задачи, стоящие перед российским монархом[6]:

- Нужно просвещать нацию, которой должно управлять.

- Нужно ввести добрый порядок в государстве, поддерживать общество и заставить его соблюдать законы.

- Нужно учредить в государстве хорошую и точную полицию.

- Нужно способствовать расцвету государства и сделать его изобильным.

- Нужно сделать государство грозным в самом себе и внушающим уважение соседям.

Политика Екатерины II характеризовалась поступательным, без резких колебаний, развитием. По восшествии на престол она провела ряд реформ (судебную, административную и др.). Территория Российского государства существенно возросла за счёт присоединения плодородных южных земель — Крыма, Причерноморья, а также восточной части Речи Посполитой и др. Население возросло с 23,2 млн (в 1763 г.) до 37,4 млн (в 1796 г.), Россия стала самой населённой европейской страной (на неё приходилось 20 % населения Европы). Как писал Ключевский, «Армия со 162 тыс. человек усилена до 312 тыс., флот, в 1757 г. состоявший из 21 линейного корабля и 6 фрегатов, в 1790 г. считал в своем составе 67 линейных кораблей и 40 фрегатов, сумма государственных доходов с 16 млн руб. поднялась до 69 млн, то есть увеличилась более чем вчетверо, успехи внешней торговли : балтийской; в увеличении ввоза и вывоза, с 9 млн до 44 млн руб., черноморской, Екатериной и созданной, — с 390 тыс. в 1776 г. до 1900 тыс. руб. в 1796 г., рост внутреннего оборота обозначился выпуском монеты в 34 года царствования на 148 млн руб., тогда как в 62 предшествовавших года ее выпущено было только на 97 млн»[7].

Экономика России продолжала оставаться аграрной. Доля городского населения в 1796 году составляла 6,3 %. Вместе с тем, был основан ряд городов (Тирасполь, Григориополь и др.), более, чем в 2 раза увеличилась выплавка чугуна (по которому Россия вышла на 1 место в мире), возросло число парусно-полотняных мануфактур. Всего к концу XVIII в. в стране насчитывалось 1200 крупных предприятий (в 1767 г. их было 663). Значительно увеличился экспорт российских товаров в европейские страны, в том числе через созданные черноморские порты.

Внутренняя политика

Приверженность Екатерины идеям Просвещения определила характер её внутренней политики и направления реформирования различных институтов российского государства. Для характеристики внутренней политики екатерининского времени часто используется термин «просвещённый абсолютизм». По мнению Екатерины, основанному на трудах французского философа Монтескье, обширные российские пространства и суровость климата обуславливают закономерность и необходимость самодержавия в России. Исходя из этого при Екатерине происходило укрепление самодержавия, усиление бюрократического аппарата, централизации страны и унификации системы управления.

Уложенная комиссия

Предпринята попытка созыва Уложенной Комиссии, которая бы систематизировала законы. Основная цель — выяснение народных нужд для проведения всесторонних реформ.

14 дек. 1766 г. Екатерина II опубликовала Манифест о созыве комиссии и указы о порядке выборов в депутаты. Дворянам разрешено избирать одного депутата от уезда, горожанам — одного депутата от города.

В комиссии приняло участие более 600 депутатов, 33 % из них было избрано от дворянства, 36 % — от горожан, куда также входили и дворяне, 20 % — от сельского населения (государственных крестьян). Интересы православного духовенства представлял депутат от Синода.

В качестве руководящего документа Комиссии 1767 г. императрица подготовила «Наказ» — теоретическое обоснование просвещенного абсолютизма.

Первое заседание прошло в Грановитой палате в Москве

Из-за консерватизма депутатов Комиссию пришлось распустить.

Императорский совет и преобразование Сената

Вскоре после переворота государственный деятель Н. И. Панин предложил создать Императорский совет: 6 или 8 высших сановников правят совместно с монархом (как кондиции 1730 г.). Екатерина отвергла этот проект.

По другому проекту Панина был преобразован Сенат — 15 дек. 1763 г. Он был разделён на 6 департаментов, возглавляемых обер-прокурорами, во главе становился генерал-прокурор. Каждый департамент имел определённые полномочия. Общие полномочия Сената были сокращены, в частности, он лишился законодательной инициативы и стал органом контроля за деятельностью государственного аппарата и высшей судебной инстанцией. Центр законотворческой деятельности переместился непосредственно к Екатерине и её кабинету со статс-секретарями.

Губернская реформа

7 нояб. 1775 г. было принято «Учреждение для управления губерний Всероссийской империи». Вместо трехзвенного административного деления — губерния, провинция, уезд, стало действовать двухзвенное — губерния, уезд (в основе которого лежал принцип численности податного населения). Из прежних 23 губерний образовано 50, в каждой из которых проживало 300—400 тыс. д.м.п. Губернии делились на 10-12 уездов, в каждом по 20-30 тыс. д.м.п.

Генерал-губернатор (наместник) — следил за порядком в местных центрах и ему подчинялись 2-3 губернии, объединенные под его властью. Имел обширные административные, финансовые и судебные полномочия, ему подчинялись все воинские части и команды, расположенные в губерниях.

Губернатор — стоял во главе губернии. Они подчинялись непосредственно императору. Губернаторов назначал Сенат. Губернаторам был подчинен губернский прокурор. Финансами в губернии занималась Казенная палата во главе с вице-губернатором. Землеустройством занимался губернский землемер. Исполнительным органом губернатора являлось губернское правление, осуществлявшее общий надзор за деятельностью учреждений и должностных лиц. В ведении Приказа общественного призрения находились школы, больницы и приюты (социальные функции), а также сословные судебные учреждения: Верхний земский суд для дворян, Губернский магистрат, рассматривавший тяжбы между горожанами, и Верхняя расправа для суда над государственными крестьянами. Палата уголовная и гражданская судила все сословия, были высшими судебными органами в губерниях

Капитан исправник — стоял во главе уезда, предводитель дворянства, избираемый им на три года. Он являлся исполнительным органом губернского правления. В уездах как и в губерниях есть сословные учреждения: для дворян (уездный суд), для горожан (городской магистрат) и для государственных крестьян (нижняя расправа). Существовали уездный казначей и уездный землемер. В судах заседали представители сословий.

Совестный суд — призван прекратить распри и мирить спорящих и ссорящихся. Этот суд был бессословным. Высшим судебным органом в стране становится Сенат.

Так как городов — центров уездов было явно недостаточно. Екатерина II переименовала в города многие крупные сельские поселения, сделав их административными центрами. Таким образом появилось 216 новых городов. население городов стали называть мещанами и купцами.

В отдельную административную единицу был выведен город. Во главе его вместо воевод был поставлен городничий, наделенный всеми правами и полномочиями. В городах вводился строгий полицейский контроль. Город разделялся на части (районы), находившиеся над надзором частного пристава, а части делились на кварталы, контролируемые квартальным надзирателем.

Ликвидация Запорожской Сечи

Проведение губернской реформы на Левобережной Украине в 1783—1785 гг. привело к изменению полкового устройства (бывших полков и сотен) на общее для Российской империи административное деление на губернии и уезды, окончательному установлению крепостного права и уравнению в правах казацкой старшины с российским дворянством. С заключением Кючук-Кайнарджийского договора (1774) Россия получила выход в Чёрное море и Крым. На западе ослабленная Речь Посполита была на грани разделов.

Таким образом, дальнейшая необходимость в сохранении присутствия Запорожских казаков на их исторической родине для охраны южных российских границ отпала. В то же время их традиционный образ жизни часто приводил к конфликтам с российскими властями. После неоднократных погромов сербских поселенцев, а также в связи с поддержкой казаками Пугачёвского восстания, Екатерина II приказала расформировать Запорожскую Сечь, что и было исполнено по приказу Григория Потёмкина об усмирении запорожских казаков генералом Петром Текели в июне 1775 года.

Сечь была бескровно расформирована, а потом сама крепость уничтожена. Большинство казаков было распущено, но через 15 лет о них вспомнили и создали Войско Верных Запорожцев, впоследствии Черноморское казачье войско, а в 1792 году Екатерина подписывает манифест, который дарит им Кубань на вечное пользование, куда казаки и переселились, основав город Екатеринодар.

Реформы на Дону создали войсковое гражданское правительство по образцу губернских администраций центральной России.

Начало присоединения Калмыцкого ханства

В результате общих административных реформ 70-х годов, направленных на укрепление государства, было принято решение о присоединении к Российской империи калмыцкого ханства.

Своим указом от 1771 г. Екатерина ликвидировала Калмыцкое ханство, тем самым начав процесс присоединения к России государства калмыков, ранее имевшее отношения вассалитета с Российским государством. Делами калмыков стала ведать особая Экспедиция калмыцких дел, учрежденная при канцелярии астраханского губернатора. При правителях же улусов были назначены приставы из числа русских чиновников. В 1772 г. при Экспедиции калмыцких дел был учрежден калмыцкий суд — Зарго, состоящий из трех членов — по одному представителю от трех главных улусов: торгоутов, дербетов и хошоутов.

Данному решению Екатерины предшествовала последовательная политика императрицы по ограничению ханской власти в Калмыцком ханстве. Так, в 60-х годах в ханстве усилились кризисные явления, связанные с колонизацией калмыцких земель русскими помещиками и крестьянами, сокращением пастбищных угодий, ущемлением прав местной феодальной верхушки, вмешательством царских чиновников в калмыцкие дела. После устройства укрепленной Царицынской линии в районе основных кочевий калмыков стали селиться тысячи семей донских казаков, по всей Нижней Волге стали строиться города и крепости. Под пашни и сенокосы отводились лучшие пастбищные земли. Район кочевий постоянно суживался, в свою очередь это обостряло внутренние отношения в ханстве. Местная феодальная верхушка также была недовольна миссионерской деятельностью русской православной церкви по христианизации кочевников, а также оттоком людей из улусов в города и села на заработки. В этих условиях в среде калмыцких нойонов и зайсангов, при поддержке буддийской церкви созрел заговор с целью ухода народа на историческую родину — в Джунгарию.

5 января 1771 г. калмыцкие феодалы, недовольные политикой императрицы, подняли улусы, кочевавшие по левобережью Волги, и отправились в опасный путь в Центральную Азию. Еще в ноябре 1770 года войско было собрано на левом берегу под предлогом отражения набегов казахов Младшего Жуза. Основная масса калмыцкого населения проживала в то время на луговой стороне Волги. Многие нойоны и зайсанги, понимая гибельность похода, желали остаться со своими улусами, но сзади идущее войско гнало всех вперед. Этот трагический поход обернулся для народа страшным бедствием. Небольшой по численности калмыцкий этнос потерял в пути погибшими в боях, от ран, холода, голода, болезней, а также пленными около 100 000 человек, лишился почти всего скота — основного богатства народа. [1], [2], [3].

Данные трагические события в истории калмыцкого народа нашли отражение в поэме Сергея Есенина «Пугачев».

Областная реформа в Эстляндии и Лифляндии

Прибалтика в результате проведения областной реформы в 1782—1783 гг. была разделена на 2 губернии — Рижскую и Ревельскую — с учреждениями, уже существовавшими в прочих губерниях России. В Эстляндии и Лифляндии был ликвидирован особый прибалтийский порядок, предусматривовший более обширные, чем у русских помещиков, права местных дворян на труд и личность крестьянина.

Губернская реформа в Сибири и Среднем Поволжье

Сибирь была разделена на три губернии: Тобольскую, Колыванскую и Иркутскую.

Реформа проводилась правительством без учета этнического состава населения: территория Мордовии была поделена между 4-мя губерниями: Пензенской, Симбирской, Томбовской и Нижегородской.

Экономическая политика

Правление Екатерины II характеризовалось развитием экономики и торговли. Указом 1780 года фабрики и промышленные заводы были признаны собственностью, распоряжение которой не требует особого дозволения начальства. В 1763 году был запрещён свободный обмен медных денег на серебряные, чтобы не провоцировать развитие инфляции. Развитию и оживлению торговли способствовало появление новых кредитных учреждений (государственного банка и ссудной кассы) и расширение банковских операций (с 1770 года введён приём вкладов на хранение). Был учреждён государственный банк и впервые налажен выпуск бумажных денег — ассигнаций.

Большое значение имело введённое императрицей государственное регулирование цен на соль, которая являлась одним из наиболее жизненно важных в стране товаров. Сенат законодательно установил цену на соль в размере 30 копеек за пуд (вместо 50 копеек) и 10 копеек за пуд в регионах массовой засолки рыбы. Не вводя государственную монополию на торговлю солью, Екатерина рассчитывала на усиление конкуренции и улучшение, в конечном итоге, качества товара.

Возросла роль России в мировой экономике — в Англию стало в больших количествах экспортироваться российское парусное полотно, в другие европейские страны увеличился экспорт чугуна и железа (потребление чугуна на внутрироссийском рынке также значительно возросло)[8]

По новому протекционистскому тарифу 1767 г. был полностью запрещен импорт тех товаров, которые производились или могли производиться внутри России. Пошлины от 100 до 200 % накладывались на предметы роскоши, вино, зерно, игрушки… Экспортные пошлины составляли 10-23 % стоимости ввозимых товаров.

В 1773 году Россия экспортировала товаров на сумму 12 миллионов рублей, что на 2,7 миллионов рублей превышало импорт. В 1781 году экспорт уже составлял 23,7 миллионов рублей против 17,9 миллионов рублей импорта. Российские торговые суда начали плавать и в Средиземном море[8]. Благодаря политике протекционизма в 1786 г. экспорт страны составил 67,7 млн руб., а импорт — 41,9 млн руб.

Вместе с тем, Россия при Екатерине пережила ряд финансовых кризисов и вынуждена была делать внешние займы, размер которых к концу правления императрицы превысил 200 миллионов рублей серебром.

Социальная политика

В 1768 году была создана сеть городских школ, основанных на классно-урочной системе. Активно стали открываться училища. При Екатерине началось системное развитие женского образования, в 1764 году были открыты Смольный институт благородных девиц, Воспитательное общество благородных девиц. Академия наук стала одной из ведущих в Европе научных баз. Были основаны обсерватория, физический кабинет, анатомический театр, ботанический сад, инструментальные мастерские, типография, библиотека, архив. В 1783 году основана Российская академия.

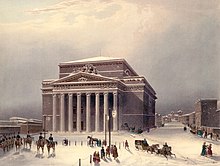

Московский Воспитательный дом

В губерниях были приказы общественного призрения. В Москве и Петербурге — Воспитательные дома для беспризорных детей (в настоящее время здания Московского Воспитательного дома занимает Военная академия им. Петра Великого), где они получали образование и воспитание. Для помощи вдовам была создана Вдовья казна.

Введено обязательное оспопрививание, причём Екатерина первой сделала такую прививку. При Екатерине II борьба с эпидемиями в России стала приобретать характер государственных мероприятий, непосредственно входивших в круг обязанностей императорского Совета, Сената. По указу Екатерины были созданы форпосты, размещенные не только на границах, но и на дорогах, ведущих в центр России. Был создан «Устав пограничных и портовых карантинов»[9].

Развивались новые для России направления медицины: были открыты больницы для лечения сифилиса, психиатрические больницы и приюты. Издан ряд фундаментальных трудов по вопросам медицины.

Национальная политика

После присоединения к Российской империи земель, прежде бывших в составе Речи Посполитой, в России оказалось около миллиона евреев — народа с иной религией, культурой, укладом и бытом. Для недопущения их переселения в центральные области России и прикрепления к своим общинам для удобства взимания государственных налогов, Екатерина II в 1791 году установила черту оседлости, за пределами которой евреи не имели права проживать. Черта оседлости была установлена там же, где евреи и проживали до этого — на присоединённых в результате трёх разделов Польши землях, а также в степных областях у Чёрного моря и малонаселенных территориях к востоку от Днепра. Переход евреев в православие снимал все ограничения на проживание. Отмечается, что черта оседлости способствовала сохранению еврейской национальной самобытности, формированию особой еврейской идентичности в рамках Российской империи[10].

В 1763—1764 году Екатериной были изданы два манифеста. Первый — «О дозволении всем иностранцам, в Россию въезжающим, поселяться в которых губерниях они пожелают и о дарованных им правах» призывал иностранных подданных переселяться в Россию, второй определял перечень льгот и привилегий переселенцам. Уже вскоре возникли первые немецкие поселения в Поволжье, отведённом для переселенцев. Наплыв немецких колонистов был столь велик, что уже в 1766 году пришлось временно приостановить приём новых переселенцев до обустройства уже въехавших. Создание колоний на Волге шло по нарастающей: в 1765 г. — 12 колоний, в 1766 г. — 21, в 1767 г. — 67. По данным переписи колонистов в 1769 г. в 105 колониях на Волге проживало 6,5 тысяч семей, что составляло 23,2 тыс. человек[11]. В будущем немецкая община будет играть заметную роль в жизни России.

В состав страны к 1786 г. вошли Северное Причерноморье, Приазовье, Крым, Правобережная Украина, земли между Днестром и Бугом, Белоруссия, Курляндия и Литва.

Население России в 1747 г. составляло 18 млн чел., к концу века — 36 млн чел.

В 1726 г. в стране было 336 городов, к нач. XIX века — 634 города. В кон. XVIII века в городах проживало ок 10 % населения. В сельской местности 54 % — частновладельческих и 40 % — государственных

Законодательство о сословиях

21 апр. 1785 г. были изданы две грамоты: «Грамота на права, вольности и преимущества благородного дворянства» и «Жалованная грамота городам».

Обе грамоты регулировали законодательство о правах и обязанностях сословий.

Жалованная грамота дворянству:

- Подтверждались уже существующие права.

- дворянство освобождалось от подушной подати

- от расквартирования войсковых частей и команд

- от телесных наказаний

- от обязательной службы

- подтверждено право неограниченного распоряжения имением

- право владеть домами в городах

- право заводить в имениях предприятия и заниматься торговлей

- право собственности на недра земли

- право иметь свои сословные учреждения

- изменилось наименование 1-ого сословия: не «дворянство», а «благородное дворянство».

- запрещалось производить конфискацию имений дворян за уголовные преступления; имения надлежало передавать законным наследникам.

- дворяне имеют исключительное право собственности на землю, но в «Грамоте» не говорится ни слова о монопольном праве иметь крепостных.

- украинская старшина была уравнена с русскими дворянами.

- дворянин, не имевший офицерского чина, лишался избирательного права.

- занимать выборные должности могли только дворяне, чей доход от имений превышает 100 руб.

Грамота на права и выгоды городам Российской империи:

- подтверждено право верхушки купечества не платить подушной подати.

- замена рекрутской повинности денежным взносом.

Разделение городского населения на 6 разрядов:

- дворяне, чиновники и духовенство («настоящие городские обыватели») — могут иметь в городах дома и землю, не занимаясь торговлей.

- купцы всех трех гильдий (низший размер капитала для купцов 3-й гильдии — 1000 руб.)

- ремесленники, записанные в цехи.

- иностранные и иногородние купцы.

- именитые граждане — купцы располагавшие капиталом свыше 50 тыс. руб., богатые банкиры (не менее 100 тыс. руб.), а также городская интеллигенция: архитекторы, живописцы, композиторы, ученые.

- посадские, которые «промыслом, рукоделием и работою кормятся» (не имеющие недвижимой собственности в городе).

Представителей 3-его и 6-ого разрядов называли «мещанами» (слово пришло из польского языка через Украину и Белоруссию, обозначало первоначально «жителя города» или «горожанина», от слова «место» — город и «местечко» — городок).

Купцы 1 и 2-й гильдии и именитые граждане были освобождены от телесных наказаний. Представителям 3-его поколения именитых граждан разрешалось возбуждать ходатайство о присвоении дворянства.

Крепостное крестьянство:

- Указ 1763 г. возлагал содержание войсковых команд, присланных на подавление крестьянских выступлений, на самих крестьян.

- По указу 1765 г. за открытое неповиновение помещик мог отправить крестьянина не только в ссылку, но и на каторгу, причем срок каторжных работ устанавливался им самим; помещикам представлялось и право в любое время вернуть сосланного с каторги.

- Указ 1767 г. запрещал крестьянам жаловаться на своего барина; ослушникам грозила ссылка в Нерчинск (но обращатся в суд они могли),

- Крестьяне не могли принимать присягу, брать откупа и подряды.

- Широких размеров достигла торговля крестьянами: их продавали на рынках, в объявлениях на станицах газет; их проигрывали в карты, обменивали, дарили, насильно женили.

- Указ от 3 мая 1783 г. запрещал крестьянам Левобережной Украины и Слободской Украины переходить от одного владельца к другому.

Распространенное представление о раздаче Екатериной государственных крестьян помещикам, как ныне доказано, является мифом [12] (для раздачи использовались крестьяне с земель приобретенных при разделах Польши, а также дворцовые крестьяне). Зона крепостничества при Екатерине распространилась на Украину. Вместе с тем, было облегчено положение монастырских крестьян, которые были переведены в ведение Коллегии экономии вместе с землями. Все их повинности заменялись денежным оброком, что представляло крестьянам больше самостоятельности и развивало их хозяйственную инициативу. В результате прекратились волнения монастырских крестьян.

Духовенство лишилось автономного существования вследствие секуляризации церковных земель (1764), дававших возможность существования без помощи государства и независимо от него. После реформы духовенство стало зависимо от финансировавшего его государства.

Религиозная политика

В целом в России при Екатерине II проводилась политика религиозной терпимости. Представители всех традиционных религий не испытывали давления и притеснения. Так, в 1773 г. издаётся закон о терпимости всех вероисповеданий, запрещающий православному духовенству вмешиваться в дела других конфессий[13]; светская власть оставляет за собой право решать вопрос об учреждении храмов любой веры[14].

Вступив на престол Екатерина отменила указ Петра III о секуляризации земель у церкви. Но уже в февр. 1764 г. вновь издала указ о лишении Церкви земельной собственности. Монастырские крестьяне числом ок 2 млн чел. обоего пола были изъяты из ведения духовенства и переданы в управление Коллегии экономии. В ведении государства вошли вотчины церквей, монастырей и архиереев.

На Украине секуляризация монастырских владений была проведена в 1786 г.

Тем самым духовенство попадало в зависимость от светской власти, так как не могло осуществлять самостоятельную экономическую деятельность.

Екатерина добилась от правительства Речи Посполитой уравнения в правах религиозных меньшинств — православных и протестантов.

При Екатерине II прекратились преследования старообрядцев. Императрица выступила инициатором возвращения из-за границы старообрядцев, экономически активного населения. Им было специально отведено место на Иргизе (современные Саратовская и Самарская области)[15]. Им было разрешено иметь священников[16].

Свободное переселение немцев в Россию привело к существенному увеличению числа протестантов (в основном лютеран) в России. Им также дозволялось строить кирхи, школы, свободно совершать богослужения. В конце XVIII века только в одном Петербурге насчитывалось более 20 тыс. лютеран.

За иудейской религией сохранялось право на публичное отправление веры. Религиозные дела и споры были оставлены в ведении еврейских судов.

По указу Екатерины II в 1787 г. в типографии Академии наук в Петербурге впервые в России был напечатан полный арабский текст исламской священной книги Корана для бесплатной раздачи «киргизам». Издание существенно отличалось от европейских прежде всего тем, что носило мусульманский характер: текст к печати был подготовлен муллой Усманом Ибрахимом. В Петербурге с 1789 по 1798 г. вышло 5 изданий Корана. В 1788 году был выпущен манифест, в котором императрица повелевала «учредить в Уфе духовное собрание Магометанского закона, которое имеет в ведомстве своем всех духовных чинов того закона, … исключая Таврической области»[17]. Таким образом, Екатерина начала встраивать мусульманское сообщество в систему государственного устройства империи. Мусульмане получали право строить и восстанавливать мечети.

Буддизм также получил государственную поддержку в регионах, где он традиционно исповедовался. В 1764 году Екатерина учредила пост хабо-ламы — главы буддистов Восточной Сибири и Забайкалья[18]. В 1766 бурятские ламы признали Екатерину воплощением Белой Тары за благожелательность к буддизму и гуманное правление.

Внутриполитические проблемы

Чумной бунт 1771

На момент взошествия на престол Екатерины II продолжал оставаться в живых в заключении в Шлиссельбургской крепости бывший российский император Иван VI. В 1764 году подпоручик В. Я. Мирович, несший караульную службу в Шлиссельбургской крепости, склонил на свою сторону часть гарнизона, чтобы освободить Ивана. Стражники, однако, в соотвествие с данными им инструкциями закололи узника, а сам Мирович был арестован и казнён.

В 1771 году в Москве произошла крупная эпидемия чумы, осложнённая народными волнениями в Москве, получившими название Чумной бунт. Восставшие разгромили Чудов монастырь в Кремле. На другой день толпа взяла приступом Донской монастырь, убила скрывавшегося в нем архиепископа Амвросия, принялась громить карантинные заставы и дома знати. На подавление восстания были направлены войска под командованием Г. Г. Орлова. После трехдневных боев бунт был подавлен.

Крестьянская война 1773—1775 годов

В 1773—1774 году произошло крестьянское восстание во главе с Емельяном Пугачёвым. Оно охватило земли Яицкого войска, Оренбургской губернии, Урал, Прикамье, Башкирию, часть Западной Сибири, Среднее и Нижнее Поволжье. В ходе восстания к казакам присоединились башкиры, татары, казахи, уральские заводские рабочие и многочисленные крепостные крестьяне всех губерний, где разворачивались военные действия. После подавления восстания были свёрнуты некоторые либеральные реформы и усилился консерватизм.

Основные этапы:

- сент. 1773 — март 1774

- март 1774 — июль 1774

- июль 1774—1775

17 сент. 1773 г. начинается восстание. Возле Яицкого городка на сторону 200 казаков переходят правительственные отряды, шедшие подавить мятеж. Не взяв городка восставшие идут к Оренбургу.

5 окт. — 22 марта 1773—1774 гг. — стояние под стенами Оренбурга.

Март — июль 1774 г. — восставшие захватывают заводы Урала и Башкирии. Под Троицкой крепостью восставшие терпят поражение. 12 июля захватывают Казань. 17 июля вновь терпят поражение и отступают на правый берег Волги.

12 сент. 1774 г. Пугачева схватили.

Масонство, Дело Новикова, Дело Радищева

Внешняя политика России в царствование Екатерины II

Внешняя политика Российского государства при Екатерине была направлена на укрепление роли России в мире и расширение её территории. Девиз её дипломатии заключался в следующем: «нужно быть в дружбе со всеми державами, чтобы всегда сохранять возможность стать на сторону более слабого… сохранять себе свободные руки… ни за кем хвостом не тащиться»[19].

Расширение пределов Российской империи

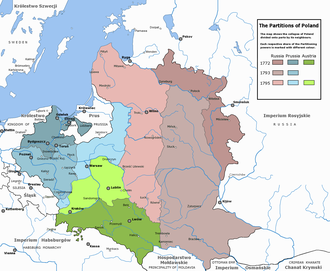

Разделы Польши

В состав федеративного государства Речь Посполитая входили Польша, Литва, Украина и Белоруссия.

Поводом для вмешательства в дела Речи Посполитой послужил вопрос о положении диссидентов (то есть некатолического меньшинства — православных и протестантов), чтобы те были уравнены с правами католиков. Екатерина оказывала сильное давление на шляхту с целью избрания на польский престол своего ставленника Станислава Августа Понятовского, который и был избран. Часть польской шляхты выступила против этих решений и организовала восстание, поднятое в Барской конфедерации. Оно было подавлено русскими войсками в союзе с польским королём. В 1772 году Пруссия и Австрия, опасаясь усиления российского влияния в Польше и её успехами в войне с Османской империей(Турция), предложили Екатерине провести раздел Речи Посполитой в обмен на прекращение войны, угрожая в противном случае войной против России. Россия, Австрия и Пруссия ввели свои войска.

В 1772 г. состоялся 1-ый раздел Речи Посполитой. Австрия получила всю Галицию с округами, Пруссия — Западную Пруссию (Поморье), Россия — восточную часть Белоруссии до Минска (губернии Витебская и Могилевская) и часть латвийских земель, входивших ранее в Ливонию.

Польский сейм был вынужден согласиться с разделом и отказаться от претензий на утраченные территории: ей было потеряно 3800 км² с населением в 4 млн человек.

Польские дворяне и промышленники содействовали принятию Конституции 1791 г. консервативная часть населения Тарговицкой конфедерации обратилась к России за помощью.

В 1793 г. состоялся 2-ой раздел Речи Посполитой, утверждённый на Гродненском сейме. Пруссия получила Гданьск, Торунь, Познань (часть земель по р. Варта и Висла), Россия — Центральную Белоруссию с Минском и Правобережную Украину.

В марте 1794 началось восстание под руководством Тадеуша Костюшко, целями которого было восстановление территориальной целостности, суверенитета и Конституции 3 мая, однако весной того же года оно было подавлено русской армией под командованием А. В. Суворова.

В 1795 г. состоялся 3-ий раздел Польши. Австрия получила Южную Польшу с Любаном и Краковом, Пруссия — Центральную Польшу с Варшавой, Россия — Литву, Курляндию, Волынь и Западную Белоруссию.

13 окт. 1795 г. — конференция трех держав о падении польского государства, оно потеряло государственность и суверенитет.

Русско-турецкие войны. Присоединение Крыма

Важным направлением внешней политики Екатерины || являлись также территории Крыма, Причерноморья и Северного Кавказа, находившиеся под турецким владычеством.

Когда вспыхнуло восстание Барской конфедерации, турецкий султан объявил войну России (Русско-турецкая война 1768—1774), используя как предлог то, что один из русских отрядов, преследуя поляков, вошёл на территорию Османской империи. Русские войска разбили конфедератов и стали одерживать одну за другой победы на юге. Добившись успеха в ряде сухопутных и морских битв (Сражение при Козлуджи, сражении при Рябой Могиле, Кагульское сражение, Ларгаское сражение, Чесменское сражение и др.), Россия заставила Турцию подписать Кючук-Кайнарджийский договор, в результате которого Крымское ханство формально обрело независимость, но де-факто стало зависеть от России. Турция выплатила России военные контрибуции в порядке 4,5 миллионов рублей, а также уступила северное побережье Чёрного моря вместе с двумя важными портами.

После окончания русско-турецкой войны 1768—1774, политика России в отношении Крымского ханства была направлена на установление в нём пророссийского правителя и присоединении к России. Под давлением русской дипломатии ханом был избран Шахин Гирей. Предыдущий хан — ставленник Турции Девлет IV Гирей — в начале 1777 года попытался оказать сопротивление, но оно было подавлено А. В. Суворовым, Девлет IV бежал в Турцию. Одновременно была недопущена высадка турецкого десанта в Крыму и тем самым предотвращена попытка развязывания новой войны, после чего Турция признала Шахина Гирея ханом. В 1782 году против него вспыхнуло восстание, которое подавили введённые на полуостров русские войска, а в 1783 году манифестом Екатерины II Крымское ханство было присоединено к России.

После победы императрица вместе с австрийским императором Иосифом II совершила триумфальную поездку по Крыму.

Следующая война с Турцией произошла в 1787—1792 годах и являлась безуспешной попыткой Османской империи вернуть себе земли, отошедшие к России в ходе Русско-турецкой войны 1768—1774, в том числе и Крым. Здесь также русские одержали ряд важнейших побед, как сухопутных — Кинбурнская баталия, Сражение при Рымнике, взятие Очакова, взятие Измаила, сражение под Фокшанами, отбиты походы турок на Бендеры и Аккерман и др., так и морских — сражение у Фидониси (1788), в Керченском морском сражении 1790, у Тендры (1790) и у мыса Калиакрия (1791). В итоге Османская империя в 1792 году была вынуждена подписать Ясский мирный договор, закрепляющий Крым и Очаков за Россией, а также отодвигавший границу между двумя империями до Днестра.

Войны с Турцией ознаменовались крупными военными победами Румянцева, Суворова, Потемкина, Кутузова, Ушакова, утверждением России на Чёрном море. В результате их к России отошло Северное Причерноморье, Крым, Прикубанье, усилились её политические позиции на Кавказе и Балканах, укреплён авторитет России на мировой арене.

Отношения с Грузией. Георгиевский трактат

Георгиевский трактат 1783 года

Екатерина II и грузинский царь Ираклий II в 1783 году заключили Георгиевский трактат, по которому Россия установила протекторат над Картли-Кахетинским царством. Договор был заключён в целях защиты православных грузин, поскольку мусульманские Иран и Турция угрожали национальному существованию Грузии. Российское правительство принимало Восточную Грузию под свое покровительство, гарантировало её автономию и защиту в случае войны, а при ведении мирных переговоров обязывалось настаивать на возвращении Картли-Кахетинскому царству владений, издавна ему принадлежавших, и незаконно отторгнутых Турцией.

Когда в 1795 году в Грузию вторглась персидская армия и разграбила Тбилиси, русские войска начали против неё боевые действия и, защищая грузин, в апреле 1796 года, взяли штурмом Дербент и подавили сопротивление персов на территории современного Азербайджана, включая крупные города (Баку, Шемаха, Ганджа).

Результатом грузинской политики Екатерины II было резкое ослабление позиций Ирана и Турции, формально уничтожившее их притязания на Восточную Грузию.

Отношения со Швецией

Пользуясь тем, что Россия вступила в войну с Турцией, Швеция, поддержанная Пруссией, Англией и Голландией развязала с ней войну за возвращение ранее утерянных территорий. Вступившие на территорию России войска были остановлены генерал-аншефом В. П. Мусиным-Пушкиным. После ряда морских сражений, не имевших решительного исхода, Россия разгромила линейный флот шведов в сражении под Выборгом, но из за налетевшего шторма потерпела тяжелое поражение в сражении гребных флотов при Роченсальме. Стороны подписали в 1790 году Верельский мирный договор, по которому граница между странами не изменилась.

Отношения с другими странами

В 1764 году нормализовались отношения между Россией и Пруссией и между странами был заключён союзный договор. Этот договор послужил основой образованию Северной системы — союзу России, Пруссии, Англии, Швеции, Дании и Речи Посполитой против Франции и Австрии. Русско-прусско-австрийское сотрудничество продолжилось и далее.

В третьей четверти XVIII в. шла борьба североамериканских колоний за независимость от Англии — буржуазная революция привела к созданию США. В 1780 г. русское правительство приняло «Декларацию о вооруженном нейтралитете», поддержанную большинством европейских стран (суда нейтральных стран имели право вооруженной защиты при нападении на них флота воюющей страны).

В европейских делах роль России возросла во время австро-прусской войны 1778—1779 годов, когда она выступила посредницей между воюющими сторонами на Тешенском конгрессе, где Екатерина по существу продиктовала свои условия примирения, восстанавливавшие равновесие в Европе[20]. После этого Россия часто выступала арбитром в спорах между германскими государствами, которые обращались за посредничеством непосредственно к Екатерине.

Одним из грандиозных планов Екатерины на внешнеполитической арене стал так называемый Греческий проект[21] — совместные планы России и Австрии по разделу турецких земель, изгнанию турок из Европы, возрождению Византийской империи и провозглашение её императором внука Екатерины — великого князя Константина Павловича. Согласно планам, на месте Бессарабии, Молдавии и Валахии создаётся буферное государство Дакия, а западная часть Балканского полуострова передаётся Австрии. Проект был разработан в начале 1780-х годов, однако осуществлён не был из-за противоречий союзников и отвоевания Россией значительных турецких территорий самостоятельно.

В октябре 1782 года подписан Договор о дружбе и торговле с Данией.

После Французской революции Екатерина выступила одним из инициаторов антифранцузской коалициии и установления принципа легитимизма. Она говорила: «Ослабление монархической власти во Франции подвергает опасности все другие монархии. С моей стороны я готова воспротивиться всеми силами. Пора действовать и приняться за оружие»[22]. Однако в реальности она устранилась от участия в боевых действиях против Франции. По распространённому мнению, одной из действительных причин создания антифранцузской коалиции было отвлечение внимания Пруссии и Австрии от польских дел[23]. Вместе с тем, Екатерина отказалась от всех заключённых с Францией договоров, приказала высылать всех подозреваемых в симпатиях к Французской революции из России, а в 1790 году выпустила указ о возвращении из Франции всех русских.

В царствование Екатерины Российская империя обрела статус «великой державы». В результате двух успешных для России русско-турецких войн 1768—1774 и 1787—1791 гг. к России был присоединен Крымский полуостров и вся территория Северного Причерноморья. В 1772—1795 гг. Россиия приняла участие в трех разделах Речи Посполитной, в результате которых присоединила к себе территории нынешней Белоруссии, Западной Украины, Литвы и Курляндии. В состав Российской империи вошла и Русская Америка — Аляска и Западное побережье Североамериканского континента (нынешний штат Калифорния).

Екатерина II как деятель Эпохи Просвещения

Екатерина — литератор и издатель

Екатерина принадлежала к немногочисленному числу монархов, которые столь интенсивно и непосредственно общались бы со своими подданными путём составления манифестов, инструкций, законов, полемических статей и косвенно в виде сатирических сочинений, исторических драм и педагогических опусов. В своих мемуарах она признавалась: «Я не могу видеть чистого пера без того, чтобы не испытывать желания немедленно окунуть его в чернила».

Она обладала незаурядным талантом литератора, оставив после себя большое собрание сочинений — записки, переводы, либретто, басни, сказки, комедии «О, время!», «Именины госпожи Ворчалкиной», «Передняя знатного боярина», «Госпожа Вестникова с семьею», «Невеста невидимка» (1771—1772), эссе и т. п., участвовала в еженедельном сатирическом журнале «Всякая всячина», издававшемся с 1769 г. Императрица обратилась к журналистике с целью воздействия на общественное мнение, поэтому главной идеей журнала была критика человеческих пороков и слабостей. Другими предметами иронии были суеверия населения. Сама Екатерина называла журнал: «Сатира в улыбательном духе».

Екатерина — меценат и коллекционер

Развитие культуры и искусства

Екатерина считала себя «философом на троне» и благосклонно относилась к европейскому Просвещению, состояла в переписке с Вольтером, Дидро, д’Аламбером.

При ней в Санкт-Петербурге появились Эрмитаж и Публичная библиотека. Она покровительствовала различным областям искусства — архитектуре, музыке, живописи.

Нельзя не упомянуть и о инициированном Екатериной массовом заселении немецких семей в различные регионы современной России, Украины, а также стран Прибалтики. Целью являлось «инфицирование» русской науки и культуры европейскими.

Двор времён Екатерины II

Особенности личной жизни

Екатерина была брюнеткой среднего роста. Она совмещала в себе высокий интеллект, образованность, государственную мудрость и приверженность к «свободной любви».

Екатерина известна своими связями с многочисленными любовниками, число которых (по списку авторитетного екатериноведа П. И. Бартенева) достигает 23. Самыми известными из них были Сергей Салтыков, Г. Г. Орлов (впоследствии граф), конной гвардии поручик Васильчиков, Г. А. Потёмкин (впоследствии князь), гусар Зорич, Ланской, последним фаворитом был корнет Платон Зубов, ставший графом Российской империи и генералом. С Потёмкиным, по некоторым данным, Екатерина была тайно обвенчана (1775). После 1762 она планировала брак с Орловым, однако по советам приближённых отказалась от этой идеи.

Стоит отметить, что «разврат» Екатерины был не таким уж скандальным явлением на фоне общей распущенности нравов XVIII столетия. Большинство королей (за исключением, пожалуй, Фридриха Великого, Людовика XVI и Карла XII) имели многочисленных любовниц. Фавориты Екатерины (за исключением Потёмкина, обладавшего государственными способностями) не оказывали влияния на политику. Тем не менее институт фаворитизма отрицательно действовал на высшее дворянство, которое искало выгод через лесть новому фавориту, пыталось провести в любовники к государыне «своего человека» и т. п.

У Екатерины было двое сыновей: Павел Петрович (1754) (подозревают, что его отцом был Сергей Салтыков) и Алексей Бобринский (1762 — сын Григория Орлова) и две дочери: умершая во младенчестве великая княжна Анна Петровна (1757—1759, возможно, дочь будущего короля Польши Станислава Понятовского) и Елизавета Григорьевна Тёмкина (1775 — дочь Потёмкина).

Серебряный рубль с профилем Екатерины II. 1774

Золотые 2 рубля для дворцового обихода с профилем Екатерины II, 1785. Обратите внимание на правдивость гравёра по изображению стареющей императрицы

Знаменитые деятели екатерининской эпохи

Правление Екатерины II характеризовалась плодотворной деятельностью выдающихся русских учёных, дипломатов, военных, государственных деятелей, деятелей культуры и искусства. В 1873 году в Санкт-Петербурге в сквере перед Александринским театром (ныне площадь Островского) был установлен внушительный многофигурный памятник Екатерине, выполненный по проекту М. О. Микешина скульпторами А. М. Опекушиным и М. А. Чижовым и архитекторами В. А. Шретером и Д. И. Гриммом. Подножье монумента состоит из скульптурной композиции, персонажи которой — выдающиеся личности екатерининской эпохи и сподвижники императрицы:

- Григорий Александрович Потёмкин-Таврический

- Александр Васильевич Суворов

- Петр Александрович Румянцев

- Александр Андреевич Безбородко

- Иван Иванович Бецкой

- Василий Яковлевич Чичагов

- Алексей Григорьевич Орлов

- Гавриил Романович Державин

- Екатерина Романовна Воронцова-Дашкова

События последних лет царствования Александра II — в частности, Русско-турецкая война 1877—1878 — помешали осуществлению замысла расширения мемориала Екатерининской эпохи. Д. И. Гримм разработал проект сооружения в сквере рядом с памятником Екатерине II бронзовых статуй и бюстов, изображающих деятелей славного царствования. Согласно окончательному списку, утвержденному за год до смерти Александра II, рядом с памятником Екатерине должны были разместиться шесть бронзовых скульптур и двадцать три бюста на гранитных постаментах.

В рост должны были быть изображены: граф Н. И. Панин, адмирал Г. А. Спиридов, писатель Д. И. Фонвизин, генерал-прокурор Сената князь А. А. Вяземский, фельдмаршал князь Н. В. Репнин и генерал А. И. Бибиков, бывший председателем Комиссии по уложению. В бюстах — издатель и журналист Н. И. Новиков, путешественник П. С. Паллас, драматург А. П. Сумароков, историки И. Н. Болтин и князь М. М. Щербатов, художники Д. Г. Левицкий и В. Л. Боровиковский, архитектор А. Ф. Кокоринов, фаворит Екатерины II граф Г. Г. Орлов, адмиралы Ф. Ф. Ушаков, С. К. Грейг, А. И. Круз, военачальники: граф З. Г. Чернышёв, князь В. М. Долгоруков-Крымский, граф И. Е. Ферзен, граф В. А. Зубов; московский генерал-губернатор князь М. Н. Волконский, новгородский губернатор граф Я. Е. Сиверс, дипломат Я. И. Булгаков, усмиритель «чумного бунта» 1771 года в Москве П. Д. Еропкин, подавившие пугачевский бунт граф П. И. Панин и И. И. Михельсон, герой взятия крепости Очаков И. И. Меллер-Закомельский.

Кроме перечисленных, отмечают таких известных деятелей эпохи, как:

- Михаил Васильевич Ломоносов

- Леонард Эйлер

- Джакомо Кваренги

- Василий Баженов

- Жан Батист Валлен-Деламот

- Н. А. Львов

- Иван Кулибин

- Матвей Казаков

Екатерина в искусстве

В кино

- «Catherine the Great», 2005. В роли Екатерины — Эмили Брун

- «Золотой век», 2003. В роли Екатерины — Вия Артмане

- «Русский ковчег», 2002. В роли Екатерины — Мария Кузнецова, Наталья Никуленко

- «Русский бунт», 2000. В роли Екатерины — Ольга Антонова

- «Catherine the Great», 1995. В роли Екатерины — Кэтрин Зета-Джонс

- «Молодая Екатерина» («Young Catherine»), 1991. В роли Екатерины — Джулия Ормонд

- «Виват, гардемарины!», 1991. В роли Екатерины — Кристина Орбакайте

- «Царская охота», 1990. В роли Екатерины — Светлана Крючкова.

звёзды черно-белого кино:

- «Great Catherine», 1968. В роли Екатерины — Жанна Моро

- «Вечера на хуторе близ Диканьки», 1961. В роли Екатерины — Зоя Василькова.

- «John Paul Jones», 1959. В роли Екатерины — Бэтт Дэвис

- «Корабли штурмуют бастионы», 1953. В роли Екатерины — Ольга Жизнева.

- «A Royal Scandal», 1945. В роли Екатерины — Таллула Бэнкхэд.

- «The Scarlet Empress», 1934. Гл. роль — Марлен Дитрих

- «Forbidden Paradise», 1924. В роли Екатерины — Пола Негри

В театре

- «Екатерина Великая. Музыкальные хроники времен империи», 2008. В роли Екатерины — народная артистка России Нина Шамбер

В литературе

- Б. Шоу. «Великая Екатерина»

- В. Н. Иванов. «Императрица Фике»

- В. С. Пикуль. «Фаворит»

- В. С. Пикуль. «Пером и шпагой»

- Борис Акунин. «Внеклассное чтение»

- Василий Аксёнов. «Вольтерьянцы и вольтерьянки»

- А. С. Пушкин. «Капитанская дочка»

- Анри Труайя. «Екатерина Великая»

В изобразительном искусстве

|

|

Портрет работы Лампи Старшего, 1793 |

|

|

Память

В 1778 году она составила для себя следующую эпитафию:

На Русский трон взойдя, желала она добра

И сильно желала дать своим подданным Счастье,Свободу и Благополучие.

Она легко прощала и никого не лишала свободы.

Она была снисходительна, не усложняла себе жизнь и была веселого нрава

Имела республиканскую душу и доброе сердце. У неё были друзья.

Работа была для неё легка, дружба и искусства несли ей радость.

Jan von Flocken— Katharina II- Verlag Neues Leben GmbH,Berlin,1991. ISBN 3-355-01215-7

Памятники

- В 1873 году памятник Екатерине II открыт на Александринской площади в Санкт-Петербурге (см. раздел Знаменитые деятели екатерининской эпохи)

- 8 сентября 2006 года памятник Екатерине II открыт в Краснодаре

- 27 октября 2007 года памятники Екатерине II были открыты в Одессе и Тирасполе

- 15 мая 2008 года открыт памятник Екатерине II в Севастополе[24]

См. также

- Русско-турецкие войны

- Территориальная экспансия России

- Дворцово-парковый ансамбль Царицыно

- Петербуржцы в Вальхалле

Ссылки

- Екатерина II. Вольное, но слабое переложение из Шакеспира, комедия Вот каково иметь корзину и белье

- Екатерина II Великая. История России екатерининской эпохи

- Мемуары Екатерины II

- Предки императрицы Екатерины II Великой

- Эпоха правления Екатерины II

- Сочинения Екатерины II на сайте Lib.ru: Классика

Литература

- Борзаковский П. К. «Императрица Екатерина Вторая Великая». — М.: Панорама, 1991. — 48 с.

- Брикнер А. Г. История Екатерины II. — М.: Современник, 1991.

- «Екатерина II и ее время: Современный взгляд». Философский век, альманах. № 11. СПб., 1999 (ideashistory.org.ru)

- Заичкин И. А., Почкаев И. Н. Русская история: От Екатерины Великой до Александра II. — М.: Мысль, 1994.

- Исабель де Мадариага. Россия в эпоху Екатерины Великой. М., 2002. 976 с — ISBN 5-86793-182-Х

- История России: В 2 т. Т. 1: С древнейших времен до конца XVIII в. / А. Н. Сахаров, Л. Е. Морозова, М. А. Рахматуллин и др.; Под редакцией А. Н. Сахарова. — М.: ООО «Издательство АСТ»: ЗАО НПП «Ермак»: ООО «Издательство Астрель», 2003. — 943 с.

- Каменский А. Б. Жизнь и судьба императрицы Екатерины Великой. М., 1997.

- Каменский А. Б. «Под сению Екатерины…»: Вторая половина XVIII века. СПб., 1992.

- Ключевский В. О. «Курс Русской Истории», часть V. — М.: Государственное Социально-Экономическое Издательство, 1937.

- Омельченко О. А. «Законная монархия» Екатерины Второй. М., 1993.

- Павленко Н. И. «Екатерина Великая». — М.: Мол. гвардия, 2000.

- Россия и Романовы: Россия под скипетром Романовых. Очерки из русской истории за время с 1613 по 1913 год / под.ред. П. Н. Жуковича. — М.: Россия; Ростов-на-Дону: Танаис, 1992 г.

- Улюра А. А. Исторические драмы Екатерины II «в подражание Шекспиру»

Примечания

- ↑ Каменский А. Б. Екатерина II //Вопросы истории — 1989 № 3

- ↑ http://www.history-gatchina.ru/article/smert_e2.htm Место смерти Екатерины II Великой

- ↑ http://www.hronos.km.ru/biograf/ekater2.html

- ↑ «Записки императрицы Екатерины Второй». М. 1989

- ↑ Шикман А. П. Деятели отечественной истории. Биографический справочник. Москва, 1997 г.

- ↑ http://nauka.relis.ru/10/0303/10303086.htm

- ↑ Ключевский В. О. Курс Русской Истории. Часть V. — М.: Государственное Социально-Экономическое Издательство, 1937.

- ↑ 1 2 Бердышев С. Н. Екатерина Великая. — М.: Мир книги, 2007. — 240 с.

- ↑ http://speclit.med-lib.ru/other/20.shtml

- ↑ «Царство разума» и «еврейский вопрос»: Как Екатерина Вторая вводила черту оседлости в Российской империи

- ↑ Поволжские немцы

- ↑ Де Мадриага И. Россия в эпоху Екатерины Великой

- ↑ Муравьева М. Веротерпимая императрица //Независимая газета от 03.11.2004

- ↑ Смахтина М. В. Правительственные ограничения предпринимательства старообрядцев в XVIII первой половине XIX в. // Материалы научно-практической конференции «Прохоровские чтения»

- ↑ Смахтина М. В. Правительственные ограничения предпринимательства старообрядцев в XVIII первой половине XIX в. // Материалы научно-практической конференции «Прохоровские чтения»

- ↑ Беглопоповщина //Словать Брокгауза и Ефрона

- ↑ ОМДС: цели создания и начальный этап деятельности

- ↑ Российские буддисты отмечают 240-летие утверждения Екатериной II института хамбо-ламы

- ↑ История дипломатии — М., 1959, с. 361

- ↑ О роли России в поддержании политического равновесия в Европе

- ↑ Греческий проект

- ↑ Манфред А. З. Великая французская революция. — М, 1983. — С.111.)

- ↑ О роли России в поддержании политического равновесия в Европе

- ↑ Взгляд

|

Эпоха Просвещения |

|

|---|---|

| Выдающиеся люди эпохи по странам | |

| Австрия | Иосиф II | Леопольд II | Мария Терезия |

| Франция | Пьер Бейль | Фонтенель | Шарль Луи Монтескьё | Франсуа Кёне | Вольтер | Жорж Луи Леклерк де Бюффон | Жан Жак Руссо | Дени Дидро | Гельвеций | Жан Д’Аламбер | Гольбах | Маркиз де Сад | Кондорсе | Лавуазье | Олимпия де Гугес | см. также: Французские энциклопедисты |

| Германия | Эрхард Вейгель | Готфрид Лейбниц | Фридрих II | Иммануил Кант | Готхольд Эфраим Лессинг | Томас Аббт | Иоганн Готфрид Гердер | Адам Вейсгаупт | Иоганн Вольфганг Гёте | Фридрих Шиллер | Карл Фридрих Гаусс | Мозес Мендельсон |

| Великобритания | Томас Гоббс | Джон Локк | Исаак Ньютон | Джозеф Аддисон | Ричард Стил | Сэмюэл Джонсон | Давид Юм | Адам Смит | Джон Уилкс | Эдмунд Бёрк | Эдуард Гиббон | Джеймс Босуэлл | Джереми Бентам | Мэри Уолстонкрафт | см. также: Шотландское Просвещение |

| Италия | Джамбаттиста Вико | Чезаре Беккариа |

| Нидерланды | Гуго Гроций | Бенедикт Спиноза |

| Польша | Станислав Конарский | Станислав Август Понятовский | Игнацы Красицкий | Гуго Коллонтай | Игнацы Потоцкий | Станислав Сташиц | Ян Снядецкий | Юлиан Урсын Немцевич | Анджей Снядецкий |

| Россия | Пётр I | Екатерина II | Екатерина Дашкова | Антиох Кантемир | Михаил Ломоносов | Николай Новиков | Александр Радищев | Иван Бецкой | Иван Шувалов | Михаил Щербатов |

| Испания | Гаспар Мельчор де Ховельянос | Николас Фернандес Моратин |

| США | Бенджамин Франклин | Дэвид Риттенхаус | Джон Адамс | Томас Пейн | Томас Джефферсон |

| Капитализм | Гражданские права | Критическое мышление | Деизм | Демократия | Эмпиризм | Просвещённый абсолютизм Свободные рынки | Гуманизм | Натурфилософия | Рациональность | Разум | Sapere aude | Наука | Секуляризация | Физиократия | Хаскала |

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

| Catherine the Great | ||

|---|---|---|

Portrait by Alexander Roslin, c. 1780s |

||

| Empress regnant of Russia | ||

| Reign | 9 July 1762 – 17 November 1796 | |

| Coronation | 22 September 1762 | |

| Predecessor | Peter III | |

| Successor | Paul I | |

| Empress consort of Russia | ||

| Tenure | 5 January – 9 July 1762 | |

| Born | Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst 2 May [O.S. 21 April] 1729 Stettin, Pomerania, Prussia, Holy Roman Empire (now Szczecin, Poland) |

|

| Died | 17 November [O.S. 6 November] 1796 (aged 67) Winter Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

|

| Burial |

Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg |

|

| Spouse |

Peter III of Russia (m. 1745; died 1762) |

|

| Issue among others… |

|

|

|

||

| House |

|

|

| Father | Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst | |

| Mother | Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp | |

| Religion |

|

|

| Signature |

Catherine II[a] (born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 1729 – 17 November 1796),[b] most commonly known as Catherine the Great,[c] was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power following the overthrow of her husband, Peter III. Under her long reign, inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment, Russia experienced a renaissance of culture and sciences, which led to the founding of many new cities, universities, and theatres; along with large-scale immigration from the rest of Europe, and the recognition of Russia as one of the great powers of Europe.

In her accession to power and her rule of the empire, Catherine often relied on her noble favourites, most notably Count Grigory Orlov and Grigory Potemkin. Assisted by highly successful generals such as Alexander Suvorov and Pyotr Rumyantsev, and admirals such as Samuel Greig and Fyodor Ushakov, she governed at a time when the Russian Empire was expanding rapidly by conquest and diplomacy. In the south, the Crimean Khanate was crushed following victories over the Bar Confederation and Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War. With the support of Great Britain, Russia colonised the territories of New Russia along the coasts of the Black and Azov Seas. In the west, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, ruled by Catherine’s former lover King Stanisław August Poniatowski, was eventually partitioned, with the Russian Empire gaining the largest share. In the east, Russians became the first Europeans to colonise Alaska, establishing Russian America.

Many cities and towns were founded on Catherine’s orders in the newly conquered lands, most notably Odessa, Yekaterinoslav (to-day known as Dnipro), Kherson, Nikolayev, and Sevastopol. An admirer of Peter the Great, Catherine continued to modernise Russia along Western European lines. However, military conscription and the economy continued to depend on serfdom, and the increasing demands of the state and of private landowners intensified the exploitation of serf labour. This was one of the chief reasons behind rebellions, including Pugachev’s Rebellion of Cossacks, nomads, peoples of the Volga, and peasants.

The period of Catherine the Great’s rule is also known as the Catherinian Era.[1] The Manifesto on Freedom of the Nobility, issued during the short reign of Peter III and confirmed by Catherine, freed Russian nobles from compulsory military or state service. Construction of many mansions of the nobility, in the classical style endorsed by the empress, changed the face of the country. She is often included in the ranks of the enlightened despots.[d] As a patron of the arts, she presided over the age of the Russian Enlightenment, including the establishment of the Smolny Institute of Noble Maidens, the first state-financed higher education institution for women in Europe.

Early life[edit]

Catherine was born in Stettin, Province of Pomerania, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire, as Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg. Her mother was Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp. Her father, Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, belonged to the ruling German family of Anhalt.[3] He failed to become the duke of Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and at the time of his daughter’s birth held the rank of a Prussian general in his capacity as governor of the city of Stettin. However, because her second cousin Peter III converted to Orthodox Christianity, her mother’s brother became the heir to the Swedish throne[4] and two of her first cousins, Gustav III and Charles XIII, later became Kings of Sweden.[5] In accordance with the custom then prevailing in the ruling dynasties of Germany, she received her education chiefly from a French governess and from tutors. According to her memoirs, Sophie was regarded as a tomboy, and trained herself to master a sword.

Sophie’s childhood was very uneventful. She once wrote to her correspondent Baron Grimm: «I see nothing of interest in it.»[6] Although Sophie was born a princess, her family had very little money. Her rise to power was supported by her mother Joanna’s wealthy relatives, who were both nobles and royal relations.[4] The more than 300 sovereign entities of the Holy Roman Empire, many of them quite small and powerless, made for a highly competitive political system as the various princely families fought for advantage over each other, often via political marriages.[7] For the smaller German princely families, an advantageous marriage was one of the best means of advancing their interests, and the young Sophie was groomed throughout her childhood to be the wife of some powerful ruler in order to improve the position of the reigning house of Anhalt. Besides her native German, Sophie became fluent in French, the lingua franca of European elites in the 18th century.[8] The young Sophie received the standard education for an 18th-century German princess, with a concentration upon learning the etiquette expected of a lady, French, and Lutheran theology.[9]

Sophie first met her future husband, who would become Peter III of Russia, at the age of 10. Peter was her second cousin. Based on her writings, she found Peter detestable upon meeting him. She disliked his pale complexion and his fondness for alcohol at such a young age. Peter also still played with toy soldiers. She later wrote that she stayed at one end of the castle, and Peter at the other.[10]

Marriage and reign of Peter III[edit]

Portrait of the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseyevna (the future Catherine the Great) around the time of her wedding, by Georg Christoph Grooth, 1745

The choice of Princess Sophie as wife of the future tsar was one result of the Lopukhina affair in which Count Jean Armand de Lestocq and King Frederick the Great of Prussia took an active part. The objective was to strengthen the friendship between Prussia and Russia, to weaken the influence of Austria, and to overthrow the chancellor Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin, a known partisan of the Austrian alliance on whom Russian Empress Elizabeth relied. The diplomatic intrigue failed, largely due to the intervention of Sophie’s mother, Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp. Historical accounts portray Joanna as a cold, abusive woman who loved gossip and court intrigues. Her hunger for fame centred on her daughter’s prospects of becoming empress of Russia, but she infuriated Empress Elizabeth, who eventually banned her from the country for spying for King Frederick. Empress Elizabeth knew the family well and had intended to marry Princess Joanna’s brother Charles Augustus (Karl August von Holstein); however, he died of smallpox in 1727 before the wedding could take place.[11] Despite Joanna’s interference, Empress Elizabeth took a strong liking to Sophie, and Sophie and Peter eventually married in 1745.

When Sophie arrived in Russia in 1744, she spared no effort to ingratiate herself not only with Empress Elizabeth but with her husband and with the Russian people as well. She applied herself to learning the Russian language with zeal, rising at night and walking about her bedroom barefoot, repeating her lessons. When she wrote her memoirs, she said she made the decision then to do whatever was necessary and to profess to believe whatever was required of her to become qualified to wear the crown. Although she mastered the language, she retained an accent.

Equestrian portrait of Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseyevna

Sophie recalled in her memoirs that as soon as she arrived in Russia, she fell ill with a pleuritis that almost killed her. She credited her survival to frequent bloodletting; in a single day, she had four phlebotomies. Her mother’s opposition to this practice brought her the empress’s disfavour. When Sophie’s situation looked desperate, her mother wanted her confessed by a Lutheran pastor. Awaking from her delirium, however, Sophie said, «I don’t want any Lutheran; I want my Orthodox father [clergyman]». This raised her in the empress’s esteem.

Princess Sophie’s father, a devout German Lutheran, opposed his daughter’s conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy. Despite his objections, on 28 June 1744, the Russian Orthodox Church received Princess Sophie as a member with the new name Catherine (Yekaterina or Ekaterina) and the (artificial) patronymic Алексеевна (Alekseyevna, daughter of Aleksey), so that she was in all respects the namesake of Catherine I, the mother of Elizabeth and the grandmother of Peter III. On the following day, the formal betrothal of Catherine and Peter took place and the long-planned dynastic marriage finally occurred on 21 August 1745 in Saint Petersburg. Sophie had turned 16. Her father did not travel to Russia for the wedding. The bridegroom, known as Peter von Holstein-Gottorp, had become Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (located in the north-west of present-day Germany near the border with Denmark) in 1739. The newlyweds settled in the palace of Oranienbaum, which remained the residence of the «young court» for many years. From there, they governed the duchy (which occupied less than a third of the current German state of Schleswig-Holstein, even including that part of Schleswig occupied by Denmark) to obtain experience to govern Russia.