Sergey Yesenin Autobiography

Sergey Yesenin was born to a peasant family September 21, 1895 in Konstantinovo, Ryazan, Russia. He spent most of his childhood with his grandparents, who essentially raised him. Yesenin began to write poetry at the age of nine. He is one of the most popular and well-known Russian poets of the 20th century.

In 1904 Yesenin joined the Konstantinovo zemstvo school. In 1909 he graduated it with an honorary certificate, and went on to study in the local secondary parochial school in Spas-Klepiki. From 1910 onwards, he started to write poetry systematically; In all, Yesenin wrote around thirty poems during his school years. He compiled them into what was supposed to be his first book which he titled «Bolnye Dumy» — Sick Thoughts — and tried to publish it in 1912 in Ryazan, but failed.

He left his village at 17 for Moscow and later Petrograd (subsequently Leningrad, now St. Petersburg). In the cities he became acquainted with Aleksandr Blok, the peasant poet Nikolay Klyuyev, and revolutionary politics.

Yesenin’s first marriage (which lasted three years) was in 1913 to Anna Izryadnova, a co-worker from the publishing house, with whom he had a son, Yuri. 1913 saw Yesenin becoming increasingly interested in Christianity, biblical motives became frequent in his poems. That was also the year when he became involved with the Moscow revolutionary circles: for several months his flat was under secret police surveillance and in September 1913 it was raided and searched.

In 1916 he published his first book, characteristically titled for a religious feast day, Radunitsa (“Ritual for the Dead”).

From 1916 to 1917, Yesenin was drafted into military duty

In August 1917 Yesenin married for a second time, to Zinaida Raikh. They had two children, a daughter Tatyana and a son Konstantin. Tatyana became a writer and journalist and Konstantin Yesenin would become a well-known soccer statistician.

Yesenin supported the February Revolution. Later he criticized the Bolshevik rule.

In 1920–21 he composed his long poetic drama Pugachyov, glorifying the 18th-century rebel .

He was soon the leading exponent of the school.

He also became a habitue of the literary cafes of Moscow, where he gave poetry recitals and drank excessively.

In 1922 he married the American dancer Isadora Duncan. They visited the United States, their quarrels duly observed in the world press. On their separation Yesenin returned to Russia.

Yesenin married again, a granddaughter of Tolstoy, but continued to drink heavily and to take cocaine.

In 1925 he was briefly hospitalized for a nervous breakdown.

Died December 27, 1925 in St. Petersburg, Russia. On 28th December 1925, Yesenin was found dead in the room in the Hotel Angleterre in St Petersburg. He was buried December 31, 1925, in Moscow’s Vagankovskoye Cemetery. His grave is marked by a white marble sculpture.

He was a prolific and somewhat uneven writer. His poignant short lyrics are full of striking imagery. He was very popular both during his lifetime and after his death.

Перевод

Сергей Есенин родился в крестьянской семье 21 сентября 1895 года в Константиново, Рязань, Россия. Он провел большую часть своего детства со своими бабушкой и дедушкой, которые по сути вырастили его. Есенин начал писать стихи в возрасте девяти лет. Он один из самых популярных и известных русских поэтов XX века.

В 1904 году Есенин вступил в Константиновское земское училище. В 1909 году закончил его с почетным дипломом и продолжил обучение в местной средней приходской школе в Спас-Клепики. С 1910 года начал писать стихи на постоянной основе. В целом, в школьные годы Есенин написал около тридцати стихотворений. Он собрал их в его первую книгу, которую назвал «Больные думы», пытался опубликовать книгу в 1912 году в Рязани, но потерпел неудачу.

В 17 лет он уехал из деревни в Москву, а затем в Петроград, впоследствии Ленинград, ныне Санкт-Петербург. Там он познакомился с Александром Блоком, крестьянином Николаем Клюевым и революционной политикой.

Первый брак Есенина, который длился три года, был в 1913 году с Анной Изрядновой, сотрудником издательства, с которой у него был сын Юрий. В 1913 году Есенин все больше интересовался христианством, в его стихах часто возникали библейские мотивы. Это был также год, когда он стал участвовать в московских революционных кругах: в течение нескольких месяцев его квартира находилась под наблюдением секретной полиции, а в сентябре 1913 года она подвергалась набегам и обыскам.

В 1916 году он опубликовал свою первую книгу, характерно названную для религиозного праздника Радуница — «Ритуал для мертвых».

С 1916 по 1917 год Есенин был призван в военную службу.

В августе 1917 года Есенин женился второй раз, на Зинаиде Райх. У них было двое детей, дочь Татьяна и сын Константин. Татьяна стала писателем и журналистом, а Константин Есенин станет известным футболистом-статистиком.

Есенин поддержал Февральскую революцию. Позже он подверг критике большевистское правление.

В 1920-21 годах он сочинил свою длинную поэтическую драму про Пугачева, прославляющую повстанца 18-го века.

Вскоре он стал ведущим лидером школы. Он стал завсегдатаем литературных кафе Москвы, где читал стихи и много пил.

В 1922 году он женился на американской танцовщице Айседоре Дункан. Они посетили Соединенные Штаты. Их ссоры отражались мировой прессой. После их развода Есенин вернулся в Россию.

Есенин женился в очередной раз на внучке Толстого, но продолжал сильно пить и принимать кокаин.

В 1925 году он был госпитализирован для лечения нервного срыва.

Умер 27 декабря 1925 года в Санкт-Петербурге, Россия. 28 декабря 1925 года Есенин был найден мертвым в комнате в гостинице «Англетер» в Санкт-Петербурге. Был похоронен 31 декабря 1925 года на Ваганьковском кладбище в Москве. На его могиле белая мраморная скульптура.

Он был одаренным и неоднозначным писателем. Его острая короткая лирика полна ярких образов. Он был очень популярен как во время его жизни, так и после его смерти.

Другие биографии:

- Биография А.С. Пушкина на английском с переводом

- Биография Сергея Безрукова на английском языке с переводом

|

Sergei Yesenin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 3, 1895

Konstantinovo, Rybnovsky District, Ryazan Governorate, Russian Empire[1] |

| Died | December 28, 1925 (aged 30)

Leningrad, Soviet Union (now St. Petersburg, Russia)[1] |

| Resting place | Vagankovo Cemetery, Moscow |

| Nationality |

|

| Occupation | Lyrical poet |

| Movement | Imaginism |

| Spouses |

|

Sergei Alexandrovich Yesenin (Russian: Сергей Александрович Есенин, IPA: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪtɕ jɪˈsʲenʲɪn]; (3 October [O.S. 21 September] 1895 – 28 December 1925), sometimes spelled as Esenin, was a Russian lyric poet. He is one of the most popular and well-known Russian poets of the 20th century, known for «his lyrical evocations of and nostalgia for the village life of his childhood – no idyll, presented in all its rawness, with an implied curse on urbanisation and industrialisation.»[2][3]

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Yesenin’s birth house in Konstantinovo

Sergei Yesenin was born in Konstantinovo in Ryazan Governorate of the Russian Empire to a peasant family. His father was Alexander Nikitich Yesenin (1873–1931), his mother’s name was Tatyana Fyodorovna (nee Titova, 1875–1955).[4]

Both his parents spent most of their time looking for work, father in Moscow, mother in Ryazan, so at age two Sergei was moved to the nearby village Matovo, to join Fyodor Alexeyevich and Natalya Yevtikhiyevna Titovs, his relatively well-off maternal grandparents, who essentially raised him.[5]

The Titovs had three grown-up sons, and it was they who were Yesenin’s early years’ companions. «My uncles taught me horse-riding and swimming, one of them… even employed me as hound-dog, when going out to the ponds hunting ducks,» he later remembered. He started to read aged five, and at nine began to write poetry, inspired originally by chastushkas and folklore,[6] provided mostly by the grandmother whom he also remembered as a highly religious woman who used to take him to every single monastery she chose to visit.[7] He had two younger sisters, Yekaterina (1905–1977), and Alexandra (1911–1981).[4]

In 1904 Yesenin joined the Konstantinovo zemstvo school. In 1909 he graduated from it with an honorary certificate, and went on to study in the local secondary parochial school in Spas-Klepiki. From 1910 onwards, he started to write poetry systematically; eight poems dated that year were later included in his 1925 Collected Works.[4] In all, Yesenin wrote around thirty poems during his school years. He compiled them into what was supposed to be his first book which he titled «Bolnye Dumy» (Sick Thoughts) and tried to publish it in 1912 in Ryazan, but failed.[8]

In 1912, with a teacher’s diploma, Yesenin moved to Moscow, where he supported himself working as a proofreader’s assistant at Sytin’s printing company. The following year he enrolled in Chanyavsky University to study history and philology as an external student, but had to leave it after eighteen months due to lack of funds.[7] In the University he became friends with several aspiring poets, among them Dmitry Semyonovsky, Vasily Nasedkin, Nikolai Kolokolov and Ivan Filipchenko.[5] Yesenin’s first marriage (which lasted three years) was in 1913 to Anna Izryadnova, a co-worker from the publishing house, with whom he had a son, Yuri.[9]

1913 saw Yesenin becoming increasingly interested in Christianity, biblical motives became frequent in his poems. «Grisha, what I am reading at the moment is the Gospel and find a lot of things which for me are new,»[10] he wrote to his close childhood friend G. Panfilov. That was also the year when he became involved with the Moscow revolutionary circles: for several months his flat was under secret police surveillance and in September 1913 it was raided and searched.[8]

Life and career[edit]

In January 1914, Yesenin’s first published poem «Beryoza» (The Birch Tree) appeared in the children’s magazine Mirok (Small World). More appearances followed in minor magazines such as Protalinka and Mlechny Put. In December 1914 Yesenin quit work «and gave himself to poetry, writing continually,» according to his wife.[11] Around this time he became a member of the Surikov Literary and Music circle.[4]

In 1915, exasperated with the lack of interest in his work in Moscow, Yesenin moved to Petrograd. He arrived at the city on 8 March and the next day met Alexander Blok at his home, to read him poetry. He received a warm welcome and soon became acquainted with fellow-poets Sergey Gorodetsky, Nikolai Klyuev and Andrei Bely and well known in literary circles. Blok was especially helpful in promoting Yesenin’s early literary career, describing him as «a gem of a peasant poet»[12] and his verse as «fresh, pure and resounding», even if «wordy».[13]

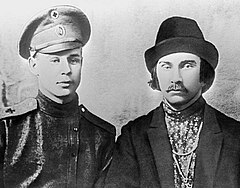

The same year he joined the Krasa (Beauty) group of peasant poets which included Klyuyev, Gorodetsky, Sergey Klychkov and Alexander Shiryayevets, among others.[8] In his 1925 autobiography Yesenin said that Bely gave him the meaning of form while Blok and Klyuev taught him lyricism.[14] It was Klyuyev who introduced Yesenin to the publisher Averyanov, who in early 1916 released his debut poetry collection Radunitsa which featured many of his early spiritual-themed verse. «I would have eagerly relinquished some of my religious poems, large and small, but they make sense as an illustration of poets’ progress towards the revolution,» he would later write.[8] Yesenin and Klyuyev maintained close and intimate[15] friendship which lasted several years.[6][16]

Later in 1915, Yesenin became a co-founder of the Krasa literary group and published numerous poems in the Petrograd magazines Russkaya Mysl, Ezhemesyachny Zhurnal, Novy Zhurnal Dlya Vsekh, Golos Zhizni and Niva.[7] Among the authors he met later in the year were Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Nikolai Gumilyov and Anna Akhmatova; he also visited painter Ilya Repin in his Penaty.[9] Yesenin’s rise to fame was meteoric; by the end of the year he became the star of St Petersburg’s literary circles and salons. «The city took to him with the delight a gourmet reserves for strawberries in winter. A barrage of praise hit him, excessive and often insincere,» Maxim Gorky wrote to Romain Rolland.[17]

On 25 March 1916, Yesenin was drafted for military duty and in April joined a medical train based in Tsarskoye Selo, under the command of colonel D.N. Loman. In 22 July 1916, at a special concert attended by the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna (the train’s patron) and her daughters, Yesenin recited his poems «Rus» and «In Scarlet Fireglow».[6] «The Empress told me my poems were beautiful, but sad. I replied, the same could be said about Russia as a whole,» he recalled later.[7] His relationships with Loman soon deteriorated. In October, Yesenin declined the colonel’s offer to write (with Klyuyev) and have published a book of pro-monarchist verses, and spent twenty days under arrest as a consequence.[9]

In March 1917, Yesenin was sent to the Warrant Officers School but soon deserted Kerensky’s army.[9] In August 1917 (having divorced Izryadnova a year earlier) Yesenin married for a second time, to Zinaida Raikh (later an actress and the wife of Vsevolod Meyerhold). They had two children, a daughter Tatyana and a son Konstantin.[4] The parents subsequently quarreled and lived separately for some time prior to their divorce in 1921. Tatyana became a writer and journalist and Konstantin Yesenin would become a well-known soccer statistician.

Yesenin supported the February Revolution. «If not for [it], I might have withered away on useless religious symbolism,» he wrote later.[8] He greeted the rise of the Bolsheviks too. «In the Revolution I was all on the side of the October, even if perceiving everything in my own peculiar way, from a peasant’s standpoint,» he remembered in his 1925 autobiography.[8] Later he criticized the Bolshevik rule, in such poems as «The Stern October Has Deceived Me». «I feel very sad now, for we are going through such a period in [our] history when human individuality is being destroyed, and the approaching socialism is totally different from the one I was dreaming of,» he wrote in an August 1920 letter to his friend Yevgeniya Livshits.[18] «I never joined the RKP, being further to the left than them,» he maintained in his 1922 autobiography.[6]

Artistically, the revolutionary years were exciting time for Yesenin. Among the important poems he wrote in 1917–1918 were «Prishestviye» (The Advent), «Preobrazheniye» (Transformation, which gave the title to the 1918 collection), and «Inoniya». In February 1918, after the Sovnarkom issued the «Socialist Homeland is in Danger!» decree-appeal, he joined the esers’ military unit. He actively participated in the magazine Nash Put (Our Way), as well as the almanacs Skify (Скифы) and Krasny Zvon (in February his large poem «Marfa Posadnitsa» appeared in one of the latter).[4] In September 1918 Yesenin co-founded (with Andrey Bely, Pyotr Oreshin, Lev Povitsky and Sergey Klychkov) the publishing house Трудовая Артель Художников Слова (the Labor Artel of the Artists of the Word) which reissued (in six books) all that he had written by this time.[19][9]

In September 1918, Yesenin became friends with Anatoly Marienhof, with whom he founded the Russian literary movement of imaginism. Describing their group’s general appeal, he wrote in 1922: «Prostitutes and bandits are our fans. With them, we are pals. Bolsheviks do not like us due to some kind of misunderstanding.»[6] In January 1919, Yesenin signed the Imaginists’ Manifest. In February he, Marienhof and Vadim Shershenevich, founded the Imaginists’ publishing house. Before that, Yesenin became a member of the Moscow Union of Professional Writers and several months later was elected a member of the All-Russian Union of Poets. Two of his books, Kobyliyu Korabli (Mare’s Ships) and Klyuchi Marii (The Keys of Mary) came out later that year.[9]

In July–August 1920, Yesenin toured the Russian South, starting in Rostov-on-Don and ending in Tiflis, Georgia. In November 1920, he met Galina Benislavskaya, his future secretary and close friend. Following an anonymous report, he and two of his Imaginist friends, brothers Alexander and Ruben Kusikovs, were arrested by the Cheka in October but released a week later on the solicitation of his friend Yakov Blumkin.[9] In the course of that year, the publication of three of Yesenin’s books were refused by publishing house Goslitizdat. His Triptych collection came out through the Skify Publishers in Berlin. Next year saw the collections Confessions of a Hooligan (January) and Treryaditsa (February) published. The drama in verse Pygachov came out in December 1921, to much acclaim.[4]

In May 1921, he visited a friend, the poet Alexander Shiryaevets, in Tashkent, giving poetry readings and making a short trip to Samarkand. In the fall of 1921, while visiting the studio of painter Georgi Yakulov, Yesenin met the Paris-based American dancer Isadora Duncan, a woman 18 years his senior. She knew only a dozen words in Russian, and he spoke no foreign languages. Nevertheless, they married on 2 May 1922. Yesenin accompanied his celebrity wife on a tour of Europe and the United States. His marriage to Duncan was brief and in May 1923, he returned to Moscow.[4]

In his 1922 autobiography, Yesenin wrote: «Russia’s recent nomadic past does not appeal to me, and I am all for civilization. But I dislike America intensely. America is a stinking place where not just art is being murdered, but with it, all the loftiest aspirations of humankind. If it’s America that we are looking up to, as [a model for our] future, then I’d rather stay under our greyish skies… We do not have those skyscrapers that’s managed to produce up to date nothing but Rockefeller and McCormick, but here Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Pushkin and Lermontov were born.»[7]

In 1923, Yesenin became romantically involved with the actress Augusta Miklashevskaya to whom he dedicated several poems, among them those of the Hooligan’s Love cycle. In the same year, he had a son by the poet Nadezhda Volpina. Alexander Esenin-Volpin grew up to become a poet and a prominent activist in the Soviet dissident movement of the 1960s. Since 1972, till his death in 2016, he lived in the United States as a famous mathematician and teacher.

As Yesenin’s popularity grew, stories began to circulate about his heavy drinking and consequent public outbursts. In autumn 1923, he was arrested in Moscow twice and underwent a series of enquiries from the OGPU secret police. Fellow poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, wrote that, after his return from America, Yesenin became more visible in newspaper police log sections than in poetry.[20]

More serious were the accusations of anti-Semitism against Yesenin and three of his close friends, fellow poets, Sergey Klytchkov, Alexei Ganin and Pyotr Oreshin, made by Lev Sosnovsky, a prominent journalist and close Trotsky associate. The foursome retorted with an open letter in Pravda and, in December, were cleared by the Writers’ Union burlaw court. It was later suggested, though, that Yesenin’s departure to the Caucasus in the summer of 1924 might have been a direct result of the harassment by the NKVD. Earlier that year, fourteen writers and poets, including his friend Ganin, were arrested as the alleged members of the (apparently fictitious) Order of the Russian Fascists, then tortured and executed in March without trial.[4]

In January–April 1924, Yesenin was arrested and interrogated four times. In February, he entered the Sheremetev hospital, then was moved into the Kremlin clinic in March. Nevertheless, he continued to make public recitals and released several books in the course of the year, including Moskva Kabatskaya. In August 1924 Yesenin and fellow poet Ivan Gruzinov published a letter in Pravda, announcing the end of the Imaginists.[9]

In early 1925, Yesenin met and married Sophia Andreyevna Tolstaya (1900–1957), a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. In May, what proved to be his final large poem Anna Snegina came out. During the year, he compiled and edited The Works by Yesenin in three volumes which was published by Gosizdat posthumously.[9]

Death[edit]

On 28 December 1925, Yesenin was found dead in his room in the Hotel Angleterre in Leningrad. His last poem Goodbye my friend, goodbye (До свиданья, друг мой, до свиданья) according to Wolf Ehrlich was written by him the day before he died. Yesenin complained that there was no ink in the room, and he was forced to write with his blood.

Yesenin’s corpse in his hotel room

Sergey Yesenin in his coffin. The second woman on the left, hand raised, is Zinaida Reich

|

До свиданья, друг мой, до свиданья. |

Farewell, my good friend, farewell. |

According to his biographers, the poet was in a state of depression and committed suicide by hanging.[21]

After the funeral in Leningrad, Yesenin’s body was transported by train to Moscow, where a farewell for relatives and friends of the deceased was also arranged. He was buried 31 December 1925, in Moscow’s Vagankovskoye Cemetery. His grave is marked by a white marble sculpture.

There is a theory that Yesenin’s death was actually a murder by OGPU agents who staged it to look like suicide. The novel Yesenin. Story of a Murder[22] by Vitali Bezrukov, is devoted to that version of Yesenin’s death. In 2005, a TV serial, Sergey Yesenin, based on the novel, was shown on Channel One Russia, with Sergey Bezrukov playing Yesenin.[23] Facts tending to support the assassination hypothesis were cited by Stanislav Kunyaev and Sergey Kunyaev in the final chapter of their biography of Yesenin.[24]

Enraged by his death, Mayakovsky composed a poem called To Sergei Yesenin, where the resigned ending of Yesenin’s death poem is countered by these verses: «in this life it is not hard to die, / to mold life is more difficult.» In a later lecture on Yesenin, he said that the revolution demanded «that we glorify life.» However, Mayakovsky himself would commit suicide in 1930.[25]

Cultural impact[edit]

Yesenin’s suicide triggered an epidemic of copycat suicides by his mostly female fans. For example, Galina Benislavskaya, his ex-girlfriend, killed herself by his graveside in December 1926. Although he was one of Russia’s most popular poets and had been given an elaborate state funeral, some of his writings were banned by the Kremlin during the reigns of Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev. Nikolai Bukharin’s criticism of Yesenin contributed significantly to the banning.

Only in 1966 were most of his works republished. Today Yesenin’s poems are taught to Russian schoolchildren; many have been set to music and recorded as popular songs. His early death, coupled with unsympathetic views by some of the literary elite, adoration by ordinary people, and sensational behavior, all contributed to the enduring and near mythical popular image of the Russian poet.

Ukrainian composer Tamara Maliukova Sidorenko (1919-2005) set several of Yesenin’s poems to music.[26]

Bernd Alois Zimmermann included his poetry in his Requiem für einen jungen Dichter (Requiem for a Young Poet), completed in 1969.

The Ryazan State University is named in his honor.[27]

Multilanguage editions[edit]

Anna Snegina (Yesenin’s poem translated into 12 languages; translated into English by Peter Tempest) ISBN 978-5-7380-0336-3

Works[edit]

- The Scarlet of the Dawn (1910)

- The high waters have licked (1910)

- The Birch Tree (1913)

- Autumn (1914)

- Russia (1914)

- A Song About a Dog/The B*tch (1915)

- I’ll glance in the field (1917)

- I left the native home (1918)

- Hooligan (1919)

- Hooligan’s Confession (1920) (Italian translation sung by Angelo Branduardi)

- I am the last poet of the village (1920)

- Prayer for the First Forty Days of the Dead (1920)

- I don’t pity, don’t call, don’t cry (1921)

- Pugachev (1921)

- Land of Scoundrels (1923)

- One joy I have left (1923)

- A Letter to Mother (1924)

- Tavern Moscow (1924)

- Confessions of a Hooligan (1924),

- A Letter to a Woman (1924),

- Desolate and Pale Moonlight (1925)

- The Black Man (1925)

- To Kachalov’s Dog (1925)

- Who Am I, What Am I (1925)

- Goodbye, my friend, goodbye (1925) (His farewell poem)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Sergey Aleksandrovich Yesenin. Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Inc (1995). Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster. pp. 1223–. ISBN 978-0-87779-042-6. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Kyle (9 January 2021). «In this accessible translation of the works of Sergei Esenin, Roger Pulvers shows why he remains Russia’s favourite poet». The Canberra Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i S.A. Yesenin. Life and Work Chronology Archived 18 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Хронологическая канва жизни и творчества Сергея Александровича Есенина (1895–1925) // Есенин С. А. Полное собрание сочинений: В 7 т. – Moscow. Nauka, 1995–2002.

- ^ a b 1924 autobiography Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Works by Sergey Yesenin in Three Volumes. Moscow: Pravda Publishers. Vol. III, p 183// Сергей Есенин. Собрание сочинений в трех томах. Библиотека «Огонек». Moscow: Pravda Publishers. 1970

- ^ a b c d e 1922 Autobiography Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Works by Sergey Yesenin in Three Volumes. Moscow. Pravda Publishers. Vol. III, pp 177-179// Сергей Есенин. Собрание сочинений в трех томах. Библиотека «Огонек». Издательство «Правда». Москва, 1970

- ^ a b c d e 1925 Autobiography Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Works by Sergey Yesenin in Three Volumes. Moscow. Pravda Publishers, vol. III, pp. 180–182 // Сергей Есенин. Собрание сочинений в трех томах. Библиотека «Огонек». Издательство «Правда». Москва, 1970

- ^ a b c d e f Zakharov, A.I. Sergey Yesenin’s biography at the Russian Writes Biobibliographical dictionary, 1990 // А. И. Захаров. «Русские писатели». Биобиблиографический словарь. Том 1. А-Л. Под редакцией П. А. Николаева. М., «Просвещение», 1990

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sergey Yesenin Timeline. – www.e-reading.club // Основные даты жизни и творчества С. А. Есенина

- ^ Гриша, в настоящее время я читаю Евангелие и нахожу очень много для меня нового

- ^ Anna Izryadnova’s Memoirs, 1965 // Изряднова А. Р. // Воспоминания о Сергее Есенине.— М., 1965.— С. 101

- ^ Alexander Blok. Notebooks // Блок А. Записные книжки. 1901–1920. М., 1965. С. 567

- ^ Alexander Blok. Collected Works in 8 Volumes. Vol.8, p. 441 // Блок А. Собр. соч.: В 8 т. – М.; Л., 1963. – Т. 8. – С. 441

- ^ 1925 Autobiography Archived 17 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Works by Sergey Yesenin in Three Volumes. Moscow. Pravda Publishers, vol. III, pp. 187–189 // Сергей Есенин. Собрание сочинений в трех томах. Библиотека «Огонек». Издательство «Правда». Москва, 1970

- ^ Между Лениным и Есениным at Izvestia.ru

- ^ Prokhushev, Yuri Sergey Yesenin. Biography. Detskaya Literatura, 1971 // Юрий Прокушев. Сергей Есенин. Москва, «Детская литература», 1971

- ^ The Collected Works by Maxim Gorky in 30 volumes. Vol. 29, p. 459 // Собр. соч.: В 30 т. – М., 1955.- Т. 29. С. 459

- ^ The Works by Sergey Yesenin in Three Volumes. Moscow. Pravda Publishers. Vol. III, p.242

- ^ Лев Повицкий, друг Сергея Есенина / Lev Povitsky, the Friend of Sergey Yesenin. – www.esenin.ru / Memoirs

- ^ V. Mayakovsky «How to Make Poems»

- ^ Royzman, M.D (1973). «26. Есенин в санаторном отделении клиники. Его побег из санатория. Доктор А. Я. Аронсон. Диагноз болезни Есенина. Его отъезд в Ленинград». Сергей Есенин Всё, что помню о Есенине (in Russian). Moscow: Sovetskaya Rossiya.

- ^ Bezrukov, Vitali (2005). Есенин. Moscow: Amfora. ISBN 5-94278-924-X.

- ^ Romanova, Natalia. «Сергей Есенин. Убийство Есенина – убийство совести русского народа коммунистическим режимом». The Epoch Times.

- ^ Kunyaev, Stanislav; Kunyaev, Sergey (2010). Сергей Есенин. Moscow: Molodaya gvardiya. ISBN 978-5-235-03363-4. (pp. 537-598). Among facts to support the assassination hypothesis were:

1) At the time of his death, Yesenin was actively working on his collected works. He was not drinking after his departure from Moscow and was enthusiastic about leaving the capital and working on other new texts. A project he was dreaming about was close to success: to start editing a literature magazine of his own. Most of his manuscripts were missing from his hotel room and had never been discovered (including his recently announced novella known under the work title When I was a boy… and his winter poems from the last months). Yesenin preferred to be well ordered in his work; but his hotel room was in extreme chaos, with his things scattered on the floor and with signs of a fight.

2) Yesenin had a fresh wound on his shoulder, one on his forehead and a bruise under one of his eyes. A few weeks before his death, many of his friends claimed that he had been carrying a revolver, but this weapon was never discovered. His jacket was missing, and he had to be covered with a sheet from the hotel. The ligature with which he purportedly hanged himself, made from a belt that later disappeared, was reportedly not a hanging one: it was only holding the body to one side, to the right. Nevertheless, no further investigations were documented to have been made in this direction. The room where he died was also not examined.

3) The photos of the hotel room and the body were not made by a police photographer. None of his close friends (e.g. Klyuev, Valerian Pravduhin, Ilya Sadofiev) was taken to see the room. Neither were they officially interrogated, while Ehrlich reportedly did not seem aggrieved by the events (Ehrlich was sentenced to death and shot in 1937). The work known as his last poem is sometimes considered as written in 1924 and dedicated to the fellow poet Viktor Manuilov.

4) The medical documentation does not include the supposed hour of death. Later experts considered it careless and point out that the language is uncharacteristic for an experienced doctor like the one involved, Alexander Gilyarevsky, who died in 1931.

5) The fact that Yesenin remained in the Hotel Angleterre, where there was a regular strong police presence, is still unexplained, given the poet’s late negativism towards the authorities and his persistent feeling that they were following him and threatening him, shared with friends on various occasions. Moreover, he was not registered in the hotel, as well as his friend, the writer Georgy Ustinov, which may be interpreted as a sign that the visit may have already been prepared and planned by others. (Georgy Ustinov also reportedly killed himself in 1932.)

- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (1975). Klop, Stikhi, Poėmy. Indiana University Press. pp. 28 (introduction by Patricia Blake). ISBN 0253201896.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International encyclopedia of women composers (Second edition, revised and enlarged ed.). New York. ISBN 0-9617485-2-4. OCLC 16714846.

- ^ «Кратко об университете». Ryazan State University. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

External links[edit]

Collection of Sergey Yesenin’s Poems in English:

- Sergey Yesenin. Collection of Poems

- Sergey Yesenin. Collection of Poems. Bilingual Version

- The Fugue Aesthetics of J.H. Stotts: Esenin, Footnotes for a Triptych at blogspot.com (Bio and English translation)

- Sergey Yesenin’s Autobiography. (English translation)

- Biography, photos and poetry (Russian)

- Yesenin’s poetry (Russian)

- Yesenin’s museum in Viazma (Russian)

- Alexander Novikov sings songs based on Yesenin’s poetry (10 songs in WMA format

- The Dark Man (English translation)

- Farewell My Friend (English translation)

- The Poems by Sergey Esenin (English)

- Works by or about Sergei Yesenin at Internet Archive

- Works by Sergei Yesenin at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Поэт – poet [ˈpoʊət]

Поэзия – poetry [ˈpoʊətri]

Стихи – verse [vɜːrs]

-Кто такой Сергей Есенин? Who is Sergey Yesenin?

-Это великий русский поэт! This is a great Russian poet.

Биография/Biography

Детство/childhood

Родился 21 сентября (3 октября) 1895 года в с. Константиново Рязанской губернии в семье крестьянина.

Образование в биографии Есенина было получено в местном земском училище(1904-1909), затем до 1912 года – в классе церковно-приходской школы. В 1913 году поступил в городской народный университет Шанявского в Москве.

Born on September 21 (October 3), 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo, Ryazan province in a peasant family.

Education in the biography of Yesenin was obtained in the local Zemstvo school (1904-1909), then until 1912 – in the class of the parish school. In 1913 he entered the city people’s University of Shanyavsky in Moscow.

Начало литературного пути/The beginning of the literary path

Впервые стихотворения Есенина были опубликованы в 1914 году.

После публикации сборников («Радуница»,1916 г.) поэт получил широкую известность.

В лирике Есенин мог психологически подойти к описанию пейзажей и крестьянской Руси.

Начиная с 1914 года Сергей Александрович печатается в детских изданиях, пишет стихи для детей (стихотворения «Сиротка»,1914г., «Побирушка»,1915г., повесть «Яр»,1916 г., «Сказка о пастушонке Пете…»,1925 г.).

В это время к Есенину приходит настоящая популярность, его приглашают на различные поэтические встречи.

Yesenin’s poems were first published in 1914.

After the publication of collections (“Radunitsa”,1916) the poet became widely known.

In the lyrics of Yesenin could psychologically approach to the description of the landscapes and peasants of Russia.

Since 1914 Sergey Alexandrovich has been published in children’s editions, writes poems for children (poems “orphan”, 1914., “Beggar”, 1915., the story “Yar”, 1916, ” the Tale of the shepherd Petya…”,1925).

At this time, Yesenin comes to real popularity, he was invited to various poetic meetings.

Последние годы жизни и смерть/ The last years of life and death

В дальнейшем творчестве Есенина очень критично были описаны российские лидеры.

Осенью 1925 года поэт женится на внучке Л. Толстого – Софье Андреевне. Депрессия, алкогольная зависимость, давление властей послужило причиной того, что новая жена поместила Сергея в психоневрологическую больницу.

Затем в биографии Сергея Есенина произошел побег в Ленинград. А 28 декабря 1925 года наступила смерть Есенина, его тело нашли повешенным в гостинице «Англетер».

In the future work of Esenina very critical has been described by Russian leaders.

In the autumn of 1925 he married the granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy – Sofya Andreyevna. Depression, alcohol dependence, the pressure of the authorities was the reason that the new wife placed Sergei in a neuropsychiatric hospital.

Then in the biography of Sergei Yesenin there was an escape to Leningrad. And on December 28, 1925, Yesenin died, his body was found hanged in the hotel “Angleterre”.

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

Сергей Есенин биография на английском

На чтение 2 мин Обновлено 20 июня, 2020

Биография Есенина на английском языке представлена в этой статье.

Сергей Есенин биография на английском

Sergei Aleksandrovich Esenin (his name also appears as Sergey Yesenin) was born into a Russian peasant family in 1895. Between 1909 and 1912 he attended the Spas-Klepiki church boarding school and it was during this time that he started to write poetry.

When he was 17, Esenin moved to Moscow wehre he joined a group of peasant and proletarian poets, the «Surikov» circle. His work was first published in the jounal Mirok in 1914 and a collection of verse, Radunitsa, followed in 1916. Esenin’s early work centred on traditional village life and the folk culture, as well as sometimes dealing with religious themes.

In 1916-17 Esenin was in military service in Tsarskoe Selo but deserted from the army after the 1917 February Revolution, rejecting the policies of the Bolshevik regime. After this he became a founding member of the Imaginist movement, advocating absolute independence for the artist. These new works shocked conservative critics with their avant-garde nature and playful blasphemy.

Amongst his most well known pieces are: Pugachev (1922),a verse tragedy concerning the peasant rebellion of 1773-75; Confessions of a Hooligan (1921), which revealed a darker and more tortured side to Esenin’s personality; and The Black Man, which is considered Esenin’s most ruthless analysis of his failures and alcoholic hallucinations.

With regards his personal life, Esenin had a son with Anna Izriadnova, with whom he lived from 1913 — 1915. He then married Zinaida Raikh in 1917 and they had two children together before divorcing in 1921. A year later he married famous American dancer Isadora Duncan, but they separated in 1924. It was also around this time that Esenin broke with the Imaginists and their style of writing. In 1925 he married a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy, but again the marriage was short lived.

Later in 1925, Esenin suffered a nervous breakdown. On 28th December that year, aged thirty, he committed suicide by hanging himself in his room in the Hotel d’Angleterre in Leningrad. Before his death, Esenin slashed his wrists and wrote with his own blood: «In this life it is not new to die, but neither it is new to be alive.»

«My Russia, wooden Russia! I am your only singer and herald»

Sergei Yesenin was born in the Ryazan region’s Konstantinovo village on October 3, 1895. From the window of his home he could see a church and the hilly banks of the Oka River, all of which he would recall in his poems.

He began writing poetry as a child and, when he left school, he moved to Moscow to conquer the literary world there. His first poems were published in Moscow.

Restlessly, in search of fame, Yesenin moved to St. Petersburg, where he became a well-known figure at literary salons, wearing traditional clothing; bast shoes or felt boots, with sheets of his poems wrapped in a rural headscarf.

The canny self-promotion in an era well before the advent of the PR industry worked brilliantly, and the self-taught village poet, with a mop of golden curls, became incredibly popular. In 1916, he got the opportunity to perform before the family of Tsar Nicholas II.

Konstantinovo, Ryazan Region. Source: Lori / Legion-Media

«Infamy has come to me, / That I am an abuser and scandalmonger»

Yesenin earned considerable notoriety as a troublemaker. Immersed in the national literary scene, he often teased other poets. His best-known literary duels were with another famous poet of the era, often considered his literary rival, Vladimir Mayakovsky.

With his love for the rural space, Yesenin did not accept his counterpart’s revolutionary and industrial poems. Mayakovsky, however, urged him not to waste his talent describing nature and dedicate his works instead to Bolshevism.

During a public reading of his poetry, Yesenin told Mayakovsky he would not give “his” Russia to him: «Russia is mine! And you are an American!» To that, Mayakovsky replied sarcastically: «Take it, here you are! Eat it with bread!»

«Many women loved me, and I loved more than one, too»

Love is the other major theme in Yesenin’s work. Quite the handsome ladies’ man, the poet had four children from various alliances and affairs. His first common-law wife, Anna, gave birth to a son, Yuri, in 1914, but Yesenin left his family and moved to St. Petersburg, rarely visiting the child.

In 1917, he married the beautiful actress Zinaida Reich, who gave birth to a daughter, Tatyana, and a son, Konstantin. The separated two years later, and Reich soon married the renowned director Vsevolod Meyerhold, becoming one of Moscow’s most famous actresses.

Yesenin’s second ‘official’ wife was the American dancer Isadora Duncan. She was 18 years older than him and neither spoke the other’s language. Their scandal-filled marriage lasted about two years. The poet accompanied Duncan on tour through Europe and America, where he would perform at parallel literary events.

Sofya, Yesenin’s third wife, was Leo Tolstoy’s granddaughter. The poet married her a few months before his death, and this was also an unhappy marriage. «Everything here is too filled with the ‘great old man,’ it is choking me,» Yesenin complained while living in Sofya’s home. It is Tolstaya who did a lot to preserve his legacy and left memoirs about him.

«Silly heart, don’t beat …»

Yesenin greeted the 1917 Revolution with enthusiasm and the hope that Russia would be transformed, but he soon saw the hunger, destruction and terror in the country, and began describing apocalyptic scenes: «the garden of skulls» and «rabid glow of corpses.»

In his long poem Pugachev – about the famous rebel and impostor who organized a mass revolt against Catherine II – Yesenin turns to the theme of confrontation between power and the people. The Land of Scoundrels, another long poem, would continue this theme.

In 1924, a year before his death, in the poem The Return Home, he describes a ravaged village with its poor wooden houses and a calendar portrait of Lenin hanging instead of an icon. Seeing Yesenin as an ideological and cultural danger, the authorities harassed the poet, bringing arbitrary court cases against him.

In 1925, nervous breakdowns, alcoholism and pressure from the authorities landed Yesenin in a mental hospital. A month later he was found hanging from a pipe in the Angleterre Hotel in Leningrad (as St. Petersburg was known in the Soviet Union). The previous day, Yesenin had composed his final poem, Goodbye, my Friend, Goodbye, in blood.

The official cause of death was suicide, but many alternative versions have been put forward in the last decade. The most common is that the troublesome poet was murdered by the Soviet authorities.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Get the week’s best stories straight to your inbox