| Messiah | |

|---|---|

| Oratorio by George Frideric Handel | |

Title page of Handel’s autograph score |

|

| Text | Charles Jennens, from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer |

| Language | English |

| Composed | 22 August 1741 – 14 September 1741: London |

| Movements | 53 in three parts |

| Vocal | SATB choir and solo |

| Instrumental |

|

Messiah (HWV 56)[1][n 1] is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel. The text was compiled from the King James Bible and the Coverdale Psalter[n 2] by Charles Jennens. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742 and received its London premiere nearly a year later. After an initially modest public reception, the oratorio gained in popularity, eventually becoming one of the best-known and most frequently performed choral works in Western music.

Handel’s reputation in England, where he had lived since 1712, had been established through his compositions of Italian opera. He turned to English oratorio in the 1730s in response to changes in public taste; Messiah was his sixth work in this genre. Although its structure resembles that of opera, it is not in dramatic form; there are no impersonations of characters and no direct speech. Instead, Jennens’s text is an extended reflection on Jesus as the Messiah called Christ. The text begins in Part I with prophecies by Isaiah and others, and moves to the annunciation to the shepherds, the only «scene» taken from the Gospels. In Part II, Handel concentrates on the Passion of Jesus and ends with the Hallelujah chorus. In Part III he covers the resurrection of the dead and Christ’s glorification in Heaven.

Handel wrote Messiah for modest vocal and instrumental forces, with optional settings for many of the individual numbers. In the years after his death, the work was adapted for performance on a much larger scale, with giant orchestras and choirs. In other efforts to update it, its orchestration was revised and amplified, such as Mozart’s Der Messias. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the trend has been towards reproducing a greater fidelity to Handel’s original intentions, although «big Messiah» productions continue to be mounted. A near-complete version was issued on 78 rpm discs in 1928; since then the work has been recorded many times.

Background[edit]

The composer George Frideric Handel, born in Halle, Germany in 1685, took up permanent residence in London in 1712, and became a naturalised British subject in 1727.[3] By 1741 his pre-eminence in British music was evident from the honours he had accumulated, including a pension from the court of King George II, the office of Composer of Musick for the Chapel Royal, and—most unusually for a living person—a statue erected in his honour in Vauxhall Gardens.[4] Within a large and varied musical output, Handel was a vigorous champion of Italian opera, which he had introduced to London in 1711 with Rinaldo. He subsequently wrote and presented more than 40 such operas in London’s theatres.[3]

By the early 1730s public taste for Italian opera was beginning to fade. The popular success of John Gay and Johann Christoph Pepusch’s The Beggar’s Opera (first performed in 1728) had heralded a spate of English-language ballad-operas that mocked the pretensions of Italian opera.[5] With box-office receipts falling, Handel’s productions were increasingly reliant on private subsidies from the nobility. Such funding became harder to obtain after the launch in 1730 of the Opera of the Nobility, a rival company to his own. Handel overcame this challenge, but he spent large sums of his own money in doing so.[6]

Although prospects for Italian opera were declining, Handel remained committed to the genre, but as alternatives to his staged works he began to introduce English-language oratorios.[7] In Rome in 1707–08 he had written two Italian oratorios at a time when opera performances in the city were temporarily forbidden under papal decree.[8] His first venture into English oratorio had been Esther, which was written and performed for a private patron in about 1718.[7] In 1732 Handel brought a revised and expanded version of Esther to the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, where members of the royal family attended a glittering premiere on 6 May. Its success encouraged Handel to write two more oratorios (Deborah and Athalia). All three oratorios were performed to large and appreciative audiences at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford in mid-1733. Undergraduates reportedly sold their furniture to raise the money for the five-shilling tickets.[9]

In 1735 Handel received the text for a new oratorio named Saul from its librettist Charles Jennens, a wealthy landowner with musical and literary interests.[10] Because Handel’s main creative concern was still with opera, he did not write the music for Saul until 1738, in preparation for his 1738–39 theatrical season. The work, after opening at the King’s Theatre in January 1739 to a warm reception, was quickly followed by the less successful oratorio Israel in Egypt (which may also have come from Jennens).[11] Although Handel continued to write operas, the trend towards English-language productions became irresistible as the decade ended. After three performances of his last Italian opera Deidamia in January and February 1741, he abandoned the genre.[12] In July 1741 Jennens sent him a new libretto for an oratorio; in a letter dated 10 July to his friend Edward Holdsworth, Jennens wrote: «I hope [Handel] will lay out his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excell all his former Compositions, as the Subject excells every other subject. The Subject is Messiah».[13]

Synopsis[edit]

In Christian theology, the Messiah is the saviour of humankind. The Messiah (Māšîaḥ) is an Old Testament Hebrew word meaning «the Anointed One», which in New Testament Greek is Christ, a title given to Jesus of Nazareth, known by his followers as «Jesus Christ». Handel’s Messiah has been described by the early-music scholar Richard Luckett as «a commentary on [Jesus Christ’s] Nativity, Passion, Resurrection and Ascension», beginning with God’s promises as spoken by the prophets and ending with Christ’s glorification in heaven.[14] In contrast with most of Handel’s oratorios, the singers in Messiah do not assume dramatic roles; there is no single, dominant narrative voice; and very little use is made of quoted speech. In his libretto, Jennens’s intention was not to dramatise the life and teachings of Jesus, but to acclaim the «Mystery of Godliness»,[15] using a compilation of extracts from the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible, and from the Psalms included in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.[16]

The three-part structure of the work approximates to that of Handel’s three-act operas, with the «parts» subdivided by Jennens into «scenes». Each scene is a collection of individual numbers or «movements» which take the form of recitatives, arias and choruses.[15] There are two instrumental numbers, the opening Sinfony[n 3] in the style of a French overture, and the pastoral Pifa, often called the «pastoral symphony», at the mid-point of Part I.[18]

In Part I, the Messiah’s coming and the virgin birth are predicted by the Old Testament prophets. The annunciation to the shepherds of the birth of the Christ is represented in the words of Luke’s gospel. Part II covers Christ’s passion and his death, his resurrection and ascension, the first spreading of the gospel through the world, and a definitive statement of God’s glory summarised in the Hallelujah. Part III begins with the promise of redemption, followed by a prediction of the day of judgment and the «general resurrection», ending with the final victory over sin and death and the acclamation of Christ.[19] According to the musicologist Donald Burrows, much of the text is so allusive as to be largely incomprehensible to those ignorant of the biblical accounts.[15] For the benefit of his audiences Jennens printed and issued a pamphlet explaining the reasons for his choices of scriptural selections.[20]

Writing history[edit]

Libretto[edit]

Charles Jennens was born around 1700, into a prosperous landowning family whose lands and properties in Warwickshire and Leicestershire he eventually inherited.[21] His religious and political views—he opposed the Act of Settlement of 1701 which secured the accession to the British throne for the House of Hanover—prevented him from receiving his degree from Balliol College, Oxford, or from pursuing any form of public career. His family’s wealth enabled him to live a life of leisure while devoting himself to his literary and musical interests.[22] Although musicologist Watkins Shaw dismisses Jennens as «a conceited figure of no special ability»,[23] Burrows has written: «of Jennens’s musical literacy there can be no doubt». He was certainly devoted to Handel’s music, having helped to finance the publication of every Handel score since Rodelinda in 1725.[24] By 1741, after their collaboration on Saul, a warm friendship had developed between the two, and Handel was a frequent visitor to the Jennens family estate at Gopsall.[21]

Jennens’s letter to Holdsworth of 10 July 1741, in which he first mentions Messiah, suggests that the text was a recent work, probably assembled earlier that summer. As a devout Anglican and believer in scriptural authority, Jennens intended to challenge advocates of Deism, who rejected the doctrine of divine intervention in human affairs.[14] Shaw describes the text as «a meditation of our Lord as Messiah in Christian thought and belief», and despite his reservations on Jennens’s character, concedes that the finished wordbook «amounts to little short of a work of genius».[23] There is no evidence that Handel played any active role in the selection or preparation of the text, such as he did in the case of Saul; it seems, rather, that he saw no need to make any significant amendment to Jennens’s work.[13]

Composition[edit]

The music for Messiah was completed in 24 days of swift composition. Having received Jennens’s text some time after 10 July 1741, Handel began work on it on 22 August. His records show that he had completed Part I in outline by 28 August, Part II by 6 September and Part III by 12 September, followed by two days of «filling up» to produce the finished work on 14 September. This rapid pace was seen by Jennens not as a sign of ecstatic energy but rather as «careless negligence», and the relations between the two men would remain strained, since Jennens «urged Handel to make improvements» while the composer stubbornly refused.[25] The autograph score’s 259 pages show some signs of haste such as blots, scratchings-out, unfilled bars and other uncorrected errors, but according to the music scholar Richard Luckett the number of errors is remarkably small in a document of this length.[26] The original manuscript for Messiah is now held in the British Library’s music collection.[27] It is scored for two trumpets, timpani, two oboes, two violins, viola, and basso continuo.

At the end of his manuscript Handel wrote the letters «SDG»—Soli Deo Gloria, «To God alone the glory». This inscription, taken with the speed of composition, has encouraged belief in the apocryphal story that Handel wrote the music in a fervour of divine inspiration in which, as he wrote the Hallelujah chorus, «He saw all heaven before him».[26] Burrows points out that many of Handel’s operas of comparable length and structure to Messiah were composed within similar timescales between theatrical seasons. The effort of writing so much music in so short a time was not unusual for Handel and his contemporaries; Handel commenced his next oratorio, Samson, within a week of finishing Messiah, and completed his draft of this new work in a month.[28][29] In accordance with his practice when writing new works, Handel adapted existing compositions for use in Messiah, in this case drawing on two recently completed Italian duets and one written twenty years previously. Thus, Se tu non lasci amore HWV 193 from 1722 became the basis of «O Death, where is thy sting?»; «His yoke is easy» and «And he shall purify» were drawn from Quel fior che all’alba ride HWV 192 (July 1741), «Unto us a child is born» and «All we like sheep» from Nò, di voi non vo’ fidarmi HWV 189 (July 1741).[30][31] Handel’s instrumentation in the score is often imprecise, again in line with contemporary convention, where the use of certain instruments and combinations was assumed and did not need to be written down by the composer; later copyists would fill in the details.[32]

Before the first performance Handel made numerous revisions to his manuscript score, in part to match the forces available for the 1742 Dublin premiere; it is probable that his work was not performed as originally conceived in his lifetime.[33] Between 1742 and 1754 he continued to revise and recompose individual movements, sometimes to suit the requirements of particular singers.[34] The first published score of Messiah was issued in 1767, eight years after Handel’s death, though this was based on relatively early manuscripts and included none of Handel’s later revisions.[35]

Dublin, 1742[edit]

The Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin, where Messiah was first performed

Handel’s decision to give a season of concerts in Dublin in the winter of 1741–42 arose from an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire, then serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[36] A violinist friend of Handel’s, Matthew Dubourg, was in Dublin as the Lord Lieutenant’s bandmaster; he would look after the tour’s orchestral requirements.[37] Whether Handel originally intended to perform Messiah in Dublin is uncertain; he did not inform Jennens of any such plan, for the latter wrote to Holdsworth on 2 December 1741: «… it was some mortification to me to hear that instead of performing Messiah here he has gone into Ireland with it.»[38] After arriving in Dublin on 18 November 1741, Handel arranged a subscription series of six concerts, to be held between December 1741 and February 1742 at the Great Music Hall, Fishamble Street. The venue had been built in 1741 specifically to accommodate concerts for the benefit of The Charitable and Musical Society for the Release of Imprisoned Debtors, a charity for whom Handel had agreed to perform one benefit performance.[39] These concerts were so popular that a second series was quickly arranged; Messiah figured in neither series.[36]

In early March Handel began discussions with the appropriate committees for a charity concert, to be given in April, at which he intended to present Messiah. He sought and was given permission from St Patrick’s and Christ Church cathedrals to use their choirs for this occasion.[40][41] These forces amounted to sixteen men and sixteen boy choristers; several of the men were allocated solo parts. The women soloists were Christina Maria Avoglio, who had sung the main soprano roles in the two subscription series, and Susannah Cibber, an established stage actress and contralto who had sung in the second series.[41][42] To accommodate Cibber’s vocal range, the recitative «Then shall the eyes of the blind» and the aria «He shall feed his flock» were transposed down to F major.[33][43] The performance, also in the Fishamble Street hall, was originally announced for 12 April, but was deferred for a day «at the request of persons of Distinction».[36] The orchestra in Dublin comprised strings, two trumpets, and timpani; the number of players is unknown. Handel had his own organ shipped to Ireland for the performances; a harpsichord was probably also used.[44]

The three charities that were to benefit were prisoners’ debt relief, the Mercer’s Hospital, and the Charitable Infirmary.[41] In its report on a public rehearsal, the Dublin News-Letter described the oratorio as «… far surpass[ing] anything of that Nature which has been performed in this or any other Kingdom».[45] Seven hundred people attended the premiere on 13 April.[46] So that the largest possible audience could be admitted to the concert, gentlemen were requested to remove their swords, and ladies were asked not to wear hoops in their dresses.[41] The performance earned unanimous praise from the assembled press: «Words are wanting to express the exquisite delight it afforded to the admiring and crouded Audience».[46] A Dublin clergyman, Rev. Delaney, was so overcome by Susanna Cibber’s rendering of «He was despised» that reportedly he leapt to his feet and cried: «Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven thee!»[47][n 4] The takings amounted to around £400, providing about £127 to each of the three nominated charities and securing the release of 142 indebted prisoners.[37][46]

Handel remained in Dublin for four months after the premiere. He organised a second performance of Messiah on 3 June, which was announced as «the last Performance of Mr Handel’s during his Stay in this Kingdom». In this second Messiah, which was for Handel’s private financial benefit, Cibber reprised her role from the first performance, though Avoglio may have been replaced by a Mrs Maclaine;[49] details of other performers are not recorded.[50]

London, 1743–59[edit]

The warm reception accorded to Messiah in Dublin was not repeated in London. Indeed, even the announcement of the performance as a «new Sacred Oratorio» drew an anonymous commentator to ask if «the Playhouse is a fit Temple to perform it».[51] Handel introduced the work at the Covent Garden theatre on 23 March 1743. Avoglio and Cibber were again the chief soloists; they were joined by the tenor John Beard, a veteran of Handel’s operas, the bass Thomas Rheinhold and two other sopranos, Kitty Clive and Miss Edwards.[52] The first performance was overshadowed by views expressed in the press that the work’s subject matter was too exalted to be performed in a theatre, particularly by secular singer-actresses such as Cibber and Clive. In an attempt to deflect such sensibilities, in London Handel had avoided the name Messiah and presented the work as the «New Sacred Oratorio».[53] As was his custom, Handel rearranged the music to suit his singers. He wrote a new setting of «And lo, the angel of the Lord» for Clive, never used subsequently. He added a tenor song for Beard: «Their sound is gone out», which had appeared in Jennens’s original libretto but had not been in the Dublin performances.[54]

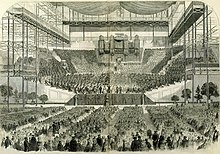

The chapel of London’s Foundling Hospital, the venue for regular charity performances of Messiah from 1750

The custom of standing for the Hallelujah chorus originates from a popular belief that, at the London premiere, King George II did so, which would have obliged all to stand. There is no convincing evidence that the king was present, or that he attended any subsequent performance of Messiah; the first reference to the practice of standing appears in a letter dated 1756, three years prior to Handel’s death.[55][56]

London’s initially cool reception of Messiah led Handel to reduce the season’s planned six performances to three, and not to present the work at all in 1744—to the considerable annoyance of Jennens, whose relations with the composer temporarily soured.[53] At Jennens’s request, Handel made several changes in the music for the 1745 revival: «Their sound is gone out» became a choral piece, the soprano song «Rejoice greatly» was recomposed in shortened form, and the transpositions for Cibber’s voice were restored to their original soprano range.[34] Jennens wrote to Holdsworth on 30 August 1745: «[Handel] has made a fine Entertainment of it, though not near so good as he might & ought to have done. I have with great difficulty made him correct some of the grosser faults in the composition …» Handel directed two performances at Covent Garden in 1745, on 9 and 11 April,[57] and then set the work aside for four years.[58]

Uncompleted admission ticket for the May 1750 performance, including the arms of the venue, the Foundling Hospital

The 1749 revival at Covent Garden, under the proper title of Messiah, saw the appearance of two female soloists who were henceforth closely associated with Handel’s music: Giulia Frasi and Caterina Galli. In the following year these were joined by the male alto Gaetano Guadagni, for whom Handel composed new versions of «But who may abide» and «Thou art gone up on high». The year 1750 also saw the institution of the annual charity performances of Messiah at London’s Foundling Hospital, which continued until Handel’s death and beyond.[59] The 1754 performance at the hospital is the first for which full details of the orchestral and vocal forces survive. The orchestra included fifteen violins, five violas, three cellos, two double basses, four bassoons, four oboes, two trumpets, two horns and drums. In the chorus of nineteen were six trebles from the Chapel Royal; the remainder, all men, were altos, tenors and basses. Frasi, Galli and Beard led the five soloists, who were required to assist the chorus.[60][n 5] For this performance the transposed Guadagni arias were restored to the soprano voice.[62] By 1754 Handel was severely afflicted by the onset of blindness, and in 1755 he turned over the direction of the Messiah hospital performance to his pupil, J. C. Smith.[63] He apparently resumed his duties in 1757 and may have continued thereafter.[64] The final performance of the work at which Handel was present was at Covent Garden on 6 April 1759, eight days before his death.[63]

Later performance history[edit]

18th century[edit]

During the 1750s Messiah was performed increasingly at festivals and cathedrals throughout the country.[65] Individual choruses and arias were occasionally extracted for use as anthems or motets in church services, or as concert pieces, a practice that grew in the 19th century and has continued ever since.[66] After Handel’s death, performances were given in Florence (1768), New York (excerpts, 1770), Hamburg (1772), and Mannheim (1777), where Mozart first heard it.[67] For the performances in Handel’s lifetime and in the decades following his death, the musical forces used in the Foundling Hospital performance of 1754 are thought by Burrows to be typical.[68] A fashion for large-scale performances began in 1784, in a series of commemorative concerts of Handel’s music given in Westminster Abbey under the patronage of King George III. A plaque on the Abbey wall records that «The Band consisting of DXXV [525] vocal & instrumental performers was conducted by Joah Bates Esqr.»[69] In a 1955 article, Sir Malcolm Sargent, a proponent of large-scale performances, wrote, «Mr Bates … had known Handel well and respected his wishes. The orchestra employed was two hundred and fifty strong, including twelve horns, twelve trumpets, six trombones and three pairs of timpani (some made especially large).»[70] In 1787 further performances were given at the Abbey; advertisements promised, «The Band will consist of Eight Hundred Performers».[71]

In continental Europe, performances of Messiah were departing from Handel’s practices in a different way: his score was being drastically reorchestrated to suit contemporary tastes. In 1786, Johann Adam Hiller presented Messiah with updated scoring in Berlin Cathedral.[72] In 1788 Hiller presented a performance of his revision with a choir of 259 and an orchestra of 87 strings, 10 bassoons, 11 oboes, 8 flutes, 8 horns, 4 clarinets, 4 trombones, 7 trumpets, timpani, harpsichord and organ.[72] In 1789, Mozart was commissioned by Baron Gottfried van Swieten and the Gesellschaft der Associierten to re-orchestrate several works by Handel, including Messiah (Der Messias).[73][n 6] Writing for a small-scale performance, he eliminated the organ continuo, added parts for flutes, clarinets, trombones and horns, recomposed some passages and rearranged others. The performance took place on 6 March 1789 in the rooms of Count Johann Esterházy, with four soloists and a choir of 12.[75][n 7] Mozart’s arrangement, with minor amendments from Hiller, was published in 1803, after his death.[n 8] The musical scholar Moritz Hauptmann described the Mozart additions as «stucco ornaments on a marble temple».[80] Mozart himself was reportedly circumspect about his changes, insisting that any alterations to Handel’s score should not be interpreted as an effort to improve the music.[81] Elements of this version later became familiar to British audiences, incorporated into editions of the score by editors including Ebenezer Prout.[75]

19th century[edit]

In the 19th century, approaches to Handel in German- and English-speaking countries diverged further. In Leipzig in 1856, the musicologist Friedrich Chrysander and the literary historian Georg Gottfried Gervinus founded the Deutsche Händel-Gesellschaft with the aim of publishing authentic editions of all Handel’s works.[67] At the same time, performances in Britain and the United States moved away from Handel’s performance practice with increasingly grandiose renditions. Messiah was presented in New York in 1853 with a chorus of 300 and in Boston in 1865 with more than 600.[82][83] In Britain a «Great Handel Festival» was held at the Crystal Palace in 1857, performing Messiah and other Handel oratorios, with a chorus of 2,000 singers and an orchestra of 500.[84]

In the 1860s and 1870s ever larger forces were assembled. Bernard Shaw, in his role as a music critic, commented, «The stale wonderment which the great chorus never fails to elicit has already been exhausted»;[85] he later wrote, «Why, instead of wasting huge sums on the multitudinous dullness of a Handel Festival does not somebody set up a thoroughly rehearsed and exhaustively studied performance of the Messiah in St James’s Hall with a chorus of twenty capable artists? Most of us would be glad to hear the work seriously performed once before we die.»[86] The employment of huge forces necessitated considerable augmentation of the orchestral parts. Many admirers of Handel believed that the composer would have made such additions, had the appropriate instruments been available in his day.[87] Shaw argued, largely unheeded, that «the composer may be spared from his friends, and the function of writing or selecting ‘additional orchestral accompaniments’ exercised with due discretion.»[88]

One reason for the popularity of huge-scale performances was the ubiquity of amateur choral societies. The conductor Sir Thomas Beecham wrote that for 200 years the chorus was «the national medium of musical utterance» in Britain. However, after the heyday of Victorian choral societies, he noted a «rapid and violent reaction against monumental performances … an appeal from several quarters that Handel should be played and heard as in the days between 1700 and 1750».[89] At the end of the century, Sir Frederick Bridge and T. W. Bourne pioneered revivals of Messiah in Handel’s orchestration, and Bourne’s work was the basis for further scholarly versions in the early 20th century.[90]

20th century and beyond[edit]

Although the huge-scale oratorio tradition was perpetuated by such large ensembles as the Royal Choral Society, the Tabernacle Choir and the Huddersfield Choral Society in the 20th century,[91] there were increasing calls for performances more faithful to Handel’s conception. At the turn of the century, The Musical Times wrote of the «additional accompaniments» of Mozart and others, «Is it not time that some of these ‘hangers on’ of Handel’s score were sent about their business?»[92] In 1902, Prout produced a new edition of the score, working from Handel’s original manuscripts rather than from corrupt printed versions with errors accumulated from one edition to another.[n 9] However, Prout started from the assumption that a faithful reproduction of Handel’s original score would not be practical:

[T]he attempts made from time to time by our musical societies to give Handel’s music as he meant it to be given must, however earnest the intention, and however careful the preparation, be foredoomed to failure from the very nature of the case. With our large choral societies, additional accompaniments of some kind are a necessity for an effective performance; and the question is not so much whether, as how they are to be written.[78]

Prout continued the practice of adding flutes, clarinets and trombones to Handel’s orchestration, but he restored Handel’s high trumpet parts, which Mozart had omitted (evidently because playing them was a lost art by 1789).[78] There was little dissent from Prout’s approach, and when Chrysander’s scholarly edition was published in the same year, it was received respectfully as «a volume for the study» rather than a performing edition, being an edited reproduction of various of Handel’s manuscript versions.[93] An authentic performance was thought impossible: The Musical Times correspondent wrote, «Handel’s orchestral instruments were all (excepting the trumpet) of a coarser quality than those at present in use; his harpsichords are gone for ever … the places in which he performed the ‘Messiah’ were mere drawing-rooms when compared with the Albert Hall, the Queen’s Hall and the Crystal Palace.[93] In Australia, The Register protested at the prospect of performances by «trumpery little church choirs of 20 voices or so».[94]

In Germany, Messiah was not so often performed as in Britain;[95] when it was given, medium-sized forces were the norm. At the Handel Festival held in 1922 in Handel’s native town, Halle, his choral works were given by a choir of 163 and an orchestra of 64.[96] In Britain, innovative broadcasting and recording contributed to reconsideration of Handelian performance. For example, in 1928, Beecham conducted a recording of Messiah with modestly sized forces and controversially brisk tempi, although the orchestration remained far from authentic.[97] In 1934 and 1935, the BBC broadcast performances of Messiah conducted by Adrian Boult with «a faithful adherence to Handel’s clear scoring.»[98] A performance with authentic scoring was given in Worcester Cathedral as part of the Three Choirs Festival in 1935.[99] In 1950 John Tobin conducted a performance of Messiah in St Paul’s Cathedral with the orchestral forces specified by the composer, a choir of 60, a countertenor alto soloist, and modest attempts at vocal elaboration of the printed notes, in the manner of Handel’s day.[100] The Prout version sung with many voices remained popular with British choral societies, but at the same time increasingly frequent performances were given by small professional ensembles in suitably sized venues, using authentic scoring. Recordings on LP and CD were preponderantly of the latter type, and the large scale Messiah came to seem old-fashioned.[101]

The cause of authentic performance was advanced in 1965 by the publication of a new edition of the score, edited by Watkins Shaw. In the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, David Scott writes, «the edition at first aroused suspicion on account of its attempts in several directions to break the crust of convention surrounding the work in the British Isles.»[102] By the time of Shaw’s death in 1996, The Times described his edition as «now in universal use».[103][n 10]

Messiah remains Handel’s best-known work, with performances particularly popular during the Advent season;[48] writing in December 1993, the music critic Alex Ross refers to that month’s 21 performances in New York alone as «numbing repetition».[105] Against the general trend towards authenticity, the work has been staged in opera houses, both in London (2009) and in Paris (2011).[106] The Mozart score is revived from time to time,[107] and in Anglophone countries «singalong» performances with many hundreds of performers are popular.[108] Although performances striving for authenticity are now usual, it is generally agreed that there can never be a definitive version of Messiah; the surviving manuscripts contain radically different settings of many numbers, and vocal and instrumental ornamentation of the written notes is a matter of personal judgment, even for the most historically informed performers.[109] The Handel scholar Winton Dean has written:

[T]here is still plenty for scholars to fight over, and more than ever for conductors to decide for themselves. Indeed if they are not prepared to grapple with the problems presented by the score they ought not to conduct it. This applies not only to the choice of versions, but to every aspect of baroque practice, and of course there are often no final answers.[104]

Music[edit]

Organisation and numbering of movements[edit]

The numbering of the movements shown here is in accordance with the Novello vocal score (1959), edited by Watkins Shaw, which adapts the numbering earlier devised by Ebenezer Prout. Other editions count the movements slightly differently; the Bärenreiter edition of 1965, for example, does not number all the recitatives and runs from 1 to 47.[110] The division into parts and scenes is based upon the 1743 word-book prepared for the first London performance.[111] The scene headings are given as Burrows summarised the scene headings by Jennens.[15]

Scene 1: Isaiah’s prophecy of salvation

Scene 2: The coming judgment

Scene 3: The prophecy of Christ’s birth

Scene 4: The annunciation to the shepherds

Scene 5: Christ’s healing and redemption

|

Scene 1: Christ’s Passion

Scene 2: Christ’s Death and Resurrection

Scene 3: Christ’s Ascension

Scene 4: Christ’s reception in Heaven

Scene 5: The beginnings of Gospel preaching

Scene 6: The world’s rejection of the Gospel

Scene 7: God’s ultimate victory

|

Scene 1: The promise of eternal life

Scene 2: The Day of Judgment

Scene 3: The final conquest of sin

Scene 4: The acclamation of the Messiah

|

Overview[edit]

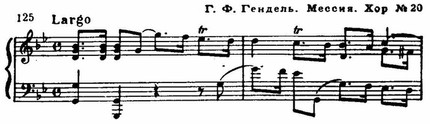

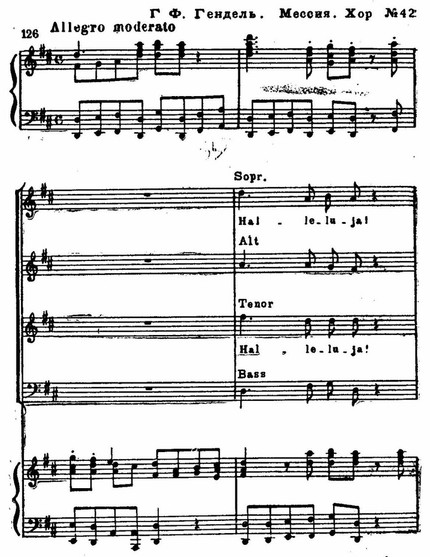

The final bars of the Hallelujah chorus, from Handel’s manuscript

Handel’s music for Messiah is distinguished from most of his other oratorios by an orchestral restraint—a quality which the musicologist Percy M. Young observes was not adopted by Mozart and other later arrangers of the music.[112] The work begins quietly, with instrumental and solo movements preceding the first appearance of the chorus, whose entry in the low alto register is muted.[43] A particular aspect of Handel’s restraint is his limited use of trumpets throughout the work. After their introduction in the Part I chorus «Glory to God», apart from the solo in «The trumpet shall sound» they are heard only in Hallelujah and the final chorus «Worthy is the Lamb».[112] It is this rarity, says Young, that makes these brass interpolations particularly effective: «Increase them and the thrill is diminished».[113] In «Glory to God», Handel marked the entry of the trumpets as da lontano e un poco piano, meaning «quietly, from afar»; his original intention had been to place the brass offstage (in disparte) at this point, to highlight the effect of distance.[31][114] In this initial appearance the trumpets lack the expected drum accompaniment, «a deliberate withholding of effect, leaving something in reserve for Parts II and III» according to Luckett.[115]

Although Messiah is not in any particular key, Handel’s tonal scheme has been summarised by the musicologist Anthony Hicks as «an aspiration towards D major», the key musically associated with light and glory. As the oratorio moves forward with various shifts in key to reflect changes in mood, D major emerges at significant points, primarily the «trumpet» movements with their uplifting messages. It is the key in which the work reaches its triumphant ending.[116] In the absence of a predominant key, other integrating elements have been proposed. For example, the musicologist Rudolf Steglich has suggested that Handel used the device of the «ascending fourth» as a unifying motif; this device most noticeably occurs in the first two notes of «I know that my Redeemer liveth» and on numerous other occasions. Nevertheless, Luckett finds this thesis implausible, and asserts that «the unity of Messiah is a consequence of nothing more arcane than the quality of Handel’s attention to his text, and the consistency of his musical imagination».[117] Allan Kozinn, The New York Times music critic, finds «a model marriage of music and text … From the gentle falling melody assigned to the opening words («Comfort ye») to the sheer ebullience of the Hallelujah chorus and the ornate celebratory counterpoint that supports the closing «Amen», hardly a line of text goes by that Handel does not amplify».[118]

Part I[edit]

The opening Sinfony is composed in E minor for strings, and is Handel’s first use in oratorio of the French overture form. Jennens commented that the Sinfony contains «passages far unworthy of Handel, but much more unworthy of the Messiah»;[117] Handel’s early biographer Charles Burney merely found it «dry and uninteresting».[43] A change of key to E major leads to the first prophecy, delivered by the tenor whose vocal line in the opening recitative «Comfort ye» is entirely independent of the strings accompaniment. The music proceeds through various key changes as the prophecies unfold, culminating in the G major chorus «For unto us a child is born», in which the choral exclamations (which include an ascending fourth in «the Mighty God») are imposed on material drawn from Handel’s Italian cantata Nò, di voi non-vo’fidarmi.[43] Such passages, says the music historian Donald Jay Grout, «reveal Handel the dramatist, the unerring master of dramatic effect».[119]

The pastoral interlude that follows begins with the short instrumental movement, the Pifa, which takes its name from the shepherd-bagpipers, or pifferari, who played their pipes in the streets of Rome at Christmas time.[114] Handel wrote the movement in both 11-bar and extended 32-bar forms; according to Burrows, either will work in performance.[34] The group of four short recitatives which follow it introduce the soprano soloist—although often the earlier aria «But who may abide» is sung by the soprano in its transposed G minor form.[120] The final recitative of this section is in D major and heralds the affirmative chorus «Glory to God». The remainder of Part I is largely carried by the soprano in B-flat, in what Burrows terms a rare instance of tonal stability.[121] The aria «He shall feed his flock» underwent several transformations by Handel, appearing at different times as a recitative, an alto aria and a duet for alto and soprano before the original soprano version was restored in 1754.[43] The appropriateness of the Italian source material for the setting of the solemn concluding chorus «His yoke is easy» has been questioned by the music scholar Sedley Taylor, who calls it «a piece of word-painting … grievously out of place», though he concedes that the four-part choral conclusion is a stroke of genius that combines beauty with dignity.[122]

Part II[edit]

The second Part begins in G minor, a key which, in Hogwood’s phrase, brings a mood of «tragic presentiment» to the long sequence of Passion numbers which follows.[47] The declamatory opening chorus «Behold the Lamb of God», in fugal form, is followed by the alto solo «He was despised» in E-flat major, the longest single item in the oratorio, in which some phrases are sung unaccompanied to emphasise Christ’s abandonment.[47] Luckett records Burney’s description of this number as «the highest idea of excellence in pathetic expression of any English song».[123] The subsequent series of mainly short choral movements cover Christ’s Passion, Crucifixion, Death and Resurrection, at first in F minor, with a brief F major respite in «All we like sheep». Here, Handel’s use of Nò, di voi non-vo’fidarmi has Sedley Taylor’s unqualified approval: «[Handel] bids the voices enter in solemn canonical sequence, and his chorus ends with a combination of grandeur and depth of feeling such as is at the command of consummate genius only».[124]

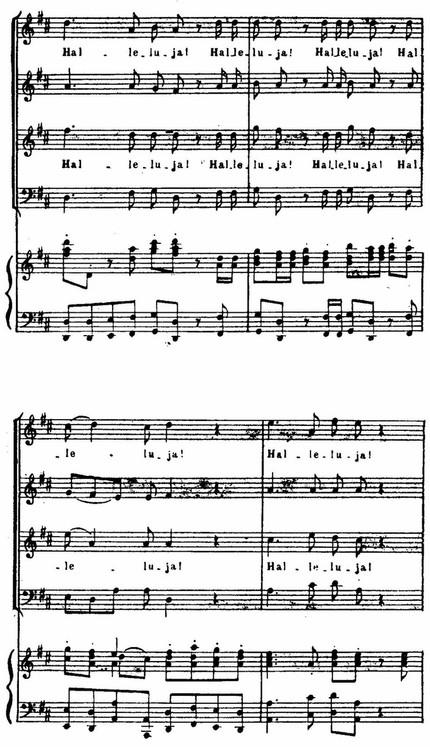

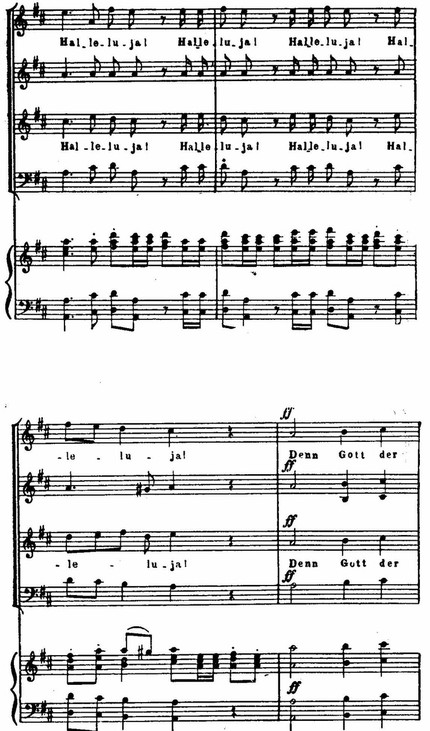

The sense of desolation returns, in what Hogwood calls the «remote and barbarous» key of B-flat minor, for the tenor recitative «All they that see him».[47][125] The sombre sequence finally ends with the Ascension chorus «Lift up your heads», which Handel initially divides between two choral groups, the altos serving both as the bass line to a soprano choir and the treble line to the tenors and basses.[126] For the 1754 Foundling Hospital performance Handel added two horns, which join in when the chorus unites towards the end of the number.[47] After the celebratory tone of Christ’s reception into heaven, marked by the choir’s D major acclamation «Let all the angels of God worship him», the «Whitsun» section proceeds through a series of contrasting moods—serene and pastoral in «How beautiful are the feet», theatrically operatic in «Why do the nations so furiously rage»—towards the Part II culmination of Hallelujah.

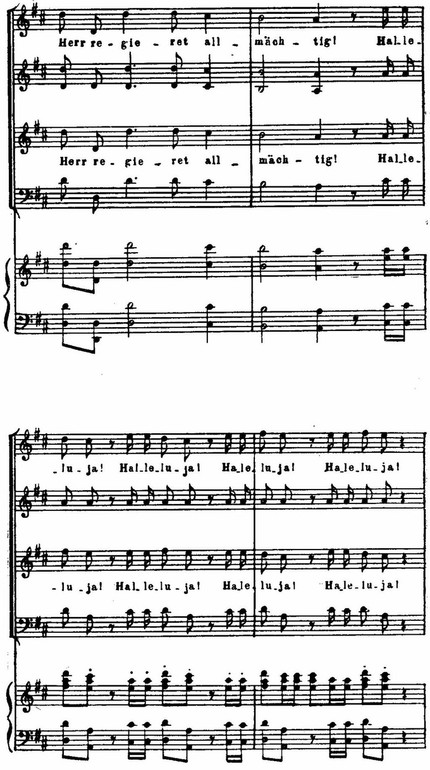

The Hallelujah chorus, as Young points out, is not the climactic chorus of the work, although one cannot escape its «contagious enthusiasm».[127] It builds from a deceptively light orchestral opening,[47] through a short, unison cantus firmus passage on the words «For the Lord God omnipotent reigneth», to the reappearance of the long-silent trumpets at «And He shall reign for ever and ever». Commentators have noted that the musical line for this third subject is based on Wachet auf,[Philipp Nicolai’s popular Lutheran chorale.[47][128]

Part III[edit]

First page of the concluding chorus «Worthy is the Lamb»: From Handel’s original manuscript in the British Library, London

The opening soprano solo in E major, «I know that my Redeemer liveth» is one of the few numbers in the oratorio that has remained unrevised from its original form.[129] Its simple unison violin accompaniment and its consoling rhythms apparently brought tears to Burney’s eyes.[130] It is followed by a quiet chorus that leads to the bass’s declamation in D major: «Behold, I tell you a mystery», then the long aria «The trumpet shall sound», marked pomposo ma non-allegro («dignified but not fast»).[129] Handel originally wrote this in da capo form, but shortened it to dal segno, probably before the first performance.[131] The extended, characteristic trumpet tune that precedes and accompanies the voice is the only significant instrumental solo in the entire oratorio. Handel’s awkward, repeated stressing of the fourth syllable of «incorruptible» may have been the source of the 18th-century poet William Shenstone’s comment that he «could observe some parts in Messiah wherein Handel’s judgements failed him; where the music was not equal, or was even opposite, to what the words required».[129][132] After a brief solo recitative, the alto is joined by the tenor for the only duet in Handel’s final version of the music, «O death, where is thy sting?» The melody is adapted from Handel’s 1722 cantata Se tu non-lasci amore, and is in Luckett’s view the most successful of the Italian borrowings.[130] The duet runs straight into the chorus «But thanks be to God».[129]

The reflective soprano solo «If God be for us» (originally written for alto) quotes Luther’s chorale Aus tiefer Not. It ushers in the D major choral finale: «Worthy is the Lamb», leading to the apocalyptic «Amen» in which, says Hogwood, «the entry of the trumpets marks the final storming of heaven».[129] Handel’s first biographer, John Mainwaring, wrote in 1760 that this conclusion revealed the composer «rising still higher» than in «that vast effort of genius, the Hallelujah chorus».[130] Young writes that the «Amen» should, in the manner of Palestrina, «be delivered as though through the aisles and ambulatories of some great church».[133]

Recordings[edit]

Many early recordings of individual choruses and arias from Messiah reflect the performance styles then fashionable—large forces, slow tempi and liberal reorchestration. Typical examples are choruses conducted by Sir Henry Wood, recorded in 1926 for Columbia with the 3,500-strong choir and orchestra of the Crystal Palace Handel Festival, and a contemporary rival disc from HMV featuring the Royal Choral Society under Sargent, recorded at the Royal Albert Hall.[134]

The first near-complete recording of the whole work (with the cuts then customary)[n 11] was conducted by Beecham in 1928. It represented an effort by Beecham to «provide an interpretation which, in his opinion, was nearer the composer’s intentions», with smaller forces and faster tempi than had become traditional.[97] His contralto soloist, Muriel Brunskill, later commented, «His tempi, which are now taken for granted, were revolutionary; he entirely revitalised it».[91] Nevertheless, Sargent retained the large-scale tradition in his four HMV recordings, the first in 1946 and three more in the 1950s and 1960s, all with the Huddersfield Choral Society and the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.[91] Beecham’s second recording of the work, in 1947, «led the way towards more truly Handelian rhythms and speeds», according to the critic Alan Blyth.[91] In a 1991 study of all 76 complete Messiahs recorded by that date, the writer Teri Noel Towe called this version of Beecham’s «one of a handful of truly stellar performances».[91]

In 1954 the first recording based on Handel’s original scoring was conducted by Hermann Scherchen for Nixa,[n 12] quickly followed by a version, judged scholarly at the time, under Sir Adrian Boult for Decca.[135] By the standards of 21st-century performance, however, Scherchen’s and Boult’s tempi were still slow, and there was no attempt at vocal ornamentation by the soloists.[135] In 1966 and 1967 two new recordings were regarded as great advances in scholarship and performance practice, conducted respectively by Colin Davis for Philips and Charles Mackerras for HMV. They inaugurated a new tradition of brisk, small-scale performances, with vocal embellishments by the solo singers.[n 13] A 1967 performance of Messiah by the Ambrosian Singers conducted by John McCarthy accompanying the English Chamber Orchestra conducted by Charles Mackerras was nominated for a Grammy Award.[138] Among recordings of older-style performances are Beecham’s 1959 recording with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, with orchestration commissioned from Sir Eugene Goossens and completed by the English composer Leonard Salzedo,[91] Karl Richter’s 1973 version for DG,[139] and David Willcocks’s 1995 performance based on Prout’s 1902 edition of the score, with a 325-voice choir and 90-piece orchestra.[140]

By the end of the 1970s the quest for authenticity had extended to the use of period instruments and historically correct styles of playing them. The first of such versions were conducted by the early music specialists Christopher Hogwood (1979) and John Eliot Gardiner (1982).[141] The use of period instruments quickly became the norm on record, although some conductors, among them Sir Georg Solti (1985), continued to favour modern instruments. Gramophone magazine and The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music highlighted two versions, conducted respectively by Trevor Pinnock (1988) and Richard Hickox (1992). The latter employs a chorus of 24 singers and an orchestra of 31 players; Handel is known to have used a chorus of 19 and an orchestra of 37.[142] Performances on an even smaller scale have followed.[n 14]

Several reconstructions of early performances have been recorded: the 1742 Dublin version by Scherchen in 1954, and again in 1959, and by Jean-Claude Malgoire in 1980.[145] In 1976, the London version of 1743 was recorded by Neville Marriner for Decca. It featured different music, alternative versions of numbers and different orchestration. There are several recordings of the 1754 Foundling Hospital version, including those under Hogwood (1979), Andrew Parrott (1989), and Paul McCreesh.[146][147] In 1973 David Willcocks conducted a set for HMV in which all the soprano arias were sung in unison by the boys of the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge,[148] and in 1974, for DG, Mackerras conducted a set of Mozart’s reorchestrated version, sung in German.[91]

Editions[edit]

The first published score of 1767, together with Handel’s documented adaptations and recompositions of various movements, has been the basis for many performing versions since the composer’s lifetime. Modern performances which seek authenticity tend to be based on one of three 20th-century performing editions.[110] These all use different methods of numbering movements:

- The Novello Edition, edited by Watkins Shaw, first published as a vocal score in 1959, revised and issued 1965. This uses the numbering first used in the Prout edition of 1902.[110]

- The Bärenreiter Edition, edited by John Tobin, published in 1965, which forms the basis of the Messiah numbering in Bernd Baselt’s catalogue (HWV) of Handel’s works, published in 1984.[110]

- The Peters Edition, edited by Donald Burrows, vocal score published 1972, which uses an adaptation of the numbering devised by Kurt Soldan.[110]

- The Van Camp Edition, edited by Leonard Van Camp, published by Roger Dean Publishing, 1993 rev. 1995 (now Lorenz pub.).

- The Oxford University Press edition by Clifford Bartlett, 1998.[149]

- The Carus-Verlag Edition, edited by Ton Koopman and Jan H. Siemons, published in 2009 (using the HWV numbering).

The edition edited by Chrysander and Max Seiffert for the Deutsche Händel-Gesellschaft (Berlin, 1902) is not a general performing edition, but has been used as a basis of scholarship and research.[110]

In addition to Mozart’s well-known reorchestration, arrangements for larger orchestral forces exist by Goossens and Andrew Davis; both have been recorded at least once, on the RCA[150] and Chandos[151] labels respectively.

See also[edit]

- Letters and writings of George Frideric Handel

- Scratch Messiah

Notes[edit]

- ^ Since its earliest performances, the work has often been referred to, incorrectly, as «The Messiah«. The article is absent from the proper title.[2]

- ^ Coverdale’s version of the Psalms was the one included with the Book of Common Prayer.

- ^ The description «Sinfony» is taken from Handel’s autograph score.[17]

- ^ It is possible that Delaney was alluding to the fact that Cibber was, at that time, involved in a scandalous divorce suit.[48]

- ^ Anthony Hicks gives a slightly different instrumentation: fourteen violins and six violas.[61]

- ^ Swieten provided Mozart with a London publication of Handel’s original orchestration (published by Randal & Abell), as well as a German translation of the English libretto, compiled and created by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and Christoph Daniel Ebeling.[74]

- ^ A repeat performance was given in the Esterháza court on 7 April 1789,[76] and between the year of Mozart’s death (1791) and 1800, there were four known performances of Mozart’s re-orchestrated Messiah in Vienna: 5 April 1795, 23 March 1799, 23 December 1799 and 24 December 1799.[77]

- ^ Hiller was long thought to have revised Mozart’s scoring substantially before the score was printed. Ebenezer Prout pointed out that the edition was published as «F. G. [sic] Händels Oratorium Der Messias, nach W. A. Mozarts Bearbeitung» – «nach» meaning after rather than in Mozart’s arrangement. Prout noted that a Mozart edition of another Handel work, Alexander’s Feast published in accordance with Mozart’s manuscript, was printed as «mit neuer Bearbeitung von W. A. Mozart» («with new arrangement by W. A. Mozart).»[78] When Mozart’s original manuscript subsequently came to light it was found that Hiller’s changes were not extensive.[79]

- ^ Many of the editions before 1902, including Mozart’s, derived from the earliest printed edition of the score, known as the Walsh Edition, published in 1767.[78]

- ^ In 1966 an edition by John Tobin was published.[104] More recent editions have included those edited by Donald Burrows (Edition Peters, 1987) and Clifford Bartlett (Oxford University Press, 1999).

- ^ The numbers customarily omitted were: from Part II, «Unto which of the angels»; «Let all the angels of God worship Him»; and «Thou art gone up on high»; and from Part III, «Then shall be brought to pass»; «O death, where is thy sting?», «But thanks be to God»; and «If God be for us».[135]

- ^ This recording was monophonic and issued on commercial CD by PRT in 1986; Scherchen re-recorded Messiah in stereo in 1959 using Vienna forces; this was issued on LP by Westminster and on commercial CD by Deutsche Grammophon in 2001. Both recordings have appeared on other labels in both LP and CD formats. A copyright-free transfer of the 1954 version (digitized from original vinyl discs by Nixa Records) is available on YouTube: part 1, part 2, part 3.

- ^ The Davis set uses a chorus of 40 singers and an orchestra of 39 players;[136] the Mackerras set uses similarly sized forces, but with fewer strings and more wind players.[137]

- ^ A 1997 recording under Harry Christophers employed a chorus of 19 and an orchestra of 20.[143] In 1993, the Scholars Baroque Ensemble released a version with 14 singers including soloists.[144]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Also catalogued as HG xlv; and HHA i/17.Hicks, Anthony (2001). «Kuzel, Zachary Frideric». In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. x (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 785.

- ^ Myers, Paul (Transcription of broadcast) (December 1999). «Handel’s Messiah». Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ a b Lynam, Peter (January 2011). Handel, George Frideric. Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ^ Luckett, p. 17

- ^ Steen, p. 55

- ^ Steen, pp. 57–58

- ^ a b Burrows (1991), p. 4

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 3

- ^ Luckett, p. 30

- ^ Luckett, p. 33

- ^ Luckett, pp. 38–41

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 6–7

- ^ a b Burrows (1991), pp. 10–11

- ^ a b Luckett, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b c d Burrows (1991), pp. 55–57

- ^ Luckett, p. 73

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 84

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 73–74

- ^ Luckett, pp. 79–80

- ^ Vickers, David. «Messiah, A Sacred Oratorio». GFHandel.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ a b «Mr Charles Jennens: the Compiler of Handel’s Messiah». The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. 43 (717): 726–27. 1 November 1902. doi:10.2307/3369540. JSTOR 3369540.

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 9–10

- ^ a b Shaw, p. 11

- ^ Smith, Ruth. «Jennens, Charles». Grove Music Online. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2011.(subscription)

- ^ Glover, p. 317

- ^ a b Luckett, p. 86

- ^ «Messiah by George Frideric Handel». British Library. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 8 and 12

- ^ Shaw, p. 18

- ^ Shaw, p. 13

- ^ a b Burrows (1991), pp. 61–62

- ^ Shaw, pp. 22–23

- ^ a b Burrows (1991), p. 22

- ^ a b c Burrows (1991), pp. 41–44

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 48

- ^ a b c Shaw, pp. 24–26

- ^ a b Cole, Hugo (Summer 1984). «Handel in Dublin». Irish Arts Review (1984–87). 1 (2): 28–30.

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 14

- ^ Bardon 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Luckett, pp. 117–19

- ^ a b c d Burrows (1991), pp. 17–19

- ^ Luckett, pp. 124–25

- ^ a b c d e Hogwood, pp. 17–21

- ^ Butt, John. Programme notes: Gloucester, Three Choirs Festival, 30 July 2013.

- ^ Luckett, p. 126

- ^ a b c Luckett, pp. 127–28

- ^ a b c d e f g Hogwood, pp. 22–25

- ^ a b Kandell, Jonathan (December 2009). «The Glorious History of Handel’s Messiah». Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ Shaw, p. 30

- ^ Luckett, p. 131

- ^ Glover, p. 318

- ^ Shaw, pp. 31–34

- ^ a b Burrows (1991), pp. 24–27

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 30–31

- ^ Luckett, p. 175

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 28–29

- ^ Luckett, p. 153

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 34–35

- ^ Shaw, pp. 42–47

- ^ Shaw, pp. 49–50

- ^ Hicks, p. 14

- ^ Hogwood, pp. 18 and 24

- ^ a b Shaw, pp. 51–52

- ^ Luckett, p. 176

- ^ Shaw, pp. 55–61

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 49

- ^ a b Leissa, Brad, and Vickers, David. «Chronology of George Frideric Handel’s Life, Compositions, and his Times: 1760 and Beyond». GFHandel.org. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ Burrows (1994), p. 304

- ^ «History: George Frederic Handel». Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Sargent, Malcolm (April 1955). «Messiah». Gramophone. p. 19. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ «Advertisement». The Daily Universal Register. 30 May 1787. p. 1.

- ^ a b Shedlock, J. S. (August 1918). «Mozart, Handel, and Johann Adam Hiller». The Musical Times. 59 (906): 370–71. doi:10.2307/908906. JSTOR 908906. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Steinberg, p. 152

- ^ Holschneider, Andreas (1962). «Händel-‐Bearbeitungen: Der Messias,Kritische Berichte». Neue Mozart Ausgabe, Series X, Werkgruppe 28, Band 2. Kassel: Bärenreiter: 40–42.

- ^ a b Robbins Landon, p. 338

- ^ Steinberg, p. 150

- ^ Link, Dorthea (1997). «Vienna’s Private Theatrical and Musical Life,1783–92, as reported by Count Karl Zinzendork». Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 12 (2): 209.

- ^ a b c d Prout, Ebenezer (May 1902). «Handel’s ‘Messiah’: Preface to the New Edition, I». The Musical Times. 43 (711): 311–13. doi:10.2307/3369304. JSTOR 3369304. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Towe, Teri Noel (1996). «George Frideric Handel – Messiah – Arranged by Mozart». Classical Net. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Cummings, William H. (10 May 1904). «The Mutilation of a Masterpiece». Proceedings of the Musical Association, 30th Session (1903–1904). 30: 113–27. doi:10.1093/jrma/30.1.113. JSTOR 765308. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Kandell, Jonathan (December 2009). «The Glorious History of Handel’s Messiah». Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ «Musical». The New York Times. 27 December 1853. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ «The Great Musical Festival in Boston». The New York Times. 4 June 1865. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ «Handel Festival, Crystal Palace». The Times. 15 June 1857. p. 6.

- ^ Laurence (Vol. 1), p. 151

- ^ Laurence (Vol. 2), pp. 245–46

- ^ Smither, Howard E. (August 1985). «‘Messiah’ and Progress in Victorian England». Early Music. 13 (3): 339–48. doi:10.1093/earlyj/13.3.339. JSTOR 3127559.(subscription required)

- ^ Laurence (Vol. 1), p, 95

- ^ Beecham, pp. 6–7

- ^ Armstrong, Thomas (2 April 1943). «Handel’s ‘Messiah’«. The Times. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Blyth, Alan (December 2003). «Handel’s Messiah – Music from Heaven». Gramophone. pp. 52–60. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ «The Sheffield Musical Festival». The Musical Times. 40 (681): 738. November 1899. doi:10.2307/3367781. JSTOR 3367781.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Cummings, William H. (January 1903). «The ‘Messiah’«. The Musical Times. 44 (719): 16–18. doi:10.2307/904855. JSTOR 904855. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ «Handel’s Messiah». The Register (Adelaide, S.A.): 4. 17 December 1908.

- ^ Brug, Manuel (14 April 2009). «Der ‘Messias’ ist hier immer noch unterschätzt». Die Welt. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2017. (German text)

- ^ van der Straeten, E. (July 1922). «The Handel Festival at Halle». The Musical Times. 63 (953): 487–89. doi:10.2307/908856. JSTOR 908856. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b «Messiah (Handel)». The Gramophone. January 1928. p. 21. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Dickinson, A. E. F. (March 1935). «The Revival of Handel’s ‘Messiah’«. The Musical Times. 76 (1105): 217–18. doi:10.2307/919222. JSTOR 919222. (subscription required)

- ^ «The Three Choirs Festival». The Manchester Guardian. 7 September 1935. p. 7.

- ^ «‘Messiah’ in First Version – Performance at St. Paul’s». The Times. 25 February 1950. p. 9. and «‘The Messiah’ in its Entirety – A Rare Performance». The Times. 20 March 1950. p. 8.

- ^ Larner, Gerald. «Which Messiah?», The Guardian, 18 December 1967, p. 5

- ^ Scott, David. «Shaw, Watkins». Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ «Harold Watkins Shaw – Obituary». The Times. 21 October 1996. p. 23.

- ^ a b Dean, Winton.; Handel; Shaw, Watkins; Tobin, John; Shaw, Watkins; Tobin, John (February 1967). «Two New ‘Messiah’ Editions». The Musical Times. 108 (1488): 157–58. doi:10.2307/953965. JSTOR 953965. (subscription required)

- ^ Ross, Alex (21 December 1993). «The Heavy Use (Good and Bad) of Handel’s Enduring Messiah«. The New York Times. pp. C10.

- ^ Maddocks, Fiona (6 December 2009). «Messiah; Falstaff From Glyndebourne». The Observer. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2011. and Bohlen, Celestine (20 April 2011). «Broadway in Paris? A Theater’s Big Experiment». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Ashley, Tim (11 December 2003). «Messiah». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ «History». The Really Big Chorus. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010. and «Do-It-Yourself Messiah 2011». International Music Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Mackerras, Charles; Lam, Basil (December 1966). «Messiah: Editions and Performances». The Musical Times. 107 (1486): 1056–57. doi:10.2307/952863. JSTOR 952863. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f Burrows (1991), pp. ix and 86–100

- ^ Burrows (1991), pp. 83–84

- ^ a b Young, p. 63

- ^ Young, p. 64

- ^ a b Luckett, p. 93

- ^ Luckett, p. 87

- ^ Hicks, pp. 10–11

- ^ a b Luckett, pp. 88–89

- ^ Kozinn, Allan (24 December 1997). «Messiah Mavens Find that its Ambiguities Reward All Comers». The New York Times. pp. E10.

- ^ Grout & Palisca, p. 445

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 87

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 63

- ^ Taylor, p. 41

- ^ Luckett, p. 95

- ^ Taylor, pp. 42–43

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 64

- ^ Luckett, p. 97

- ^ Young, p. 42

- ^ Luckett, pp. 102–04

- ^ a b c d e Hogwood, pp. 26–28

- ^ a b c Luckett, pp. 104–06

- ^ Burrows (1991), p. 99

- ^ Luckett, p. 191

- ^ Young, p. 45

- ^ Klein, Herman (August 1926). «Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 39. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Porter, Andrew, in Sackville West, pp. 337–45

- ^ Sadie, Stanley (November 1966). «Handel – Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 77. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ Fiske, Roger (March 1967). «Handel – Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 66. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ «Grammy Awards 1968». Awards and Shows. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Fiske, Roger (November 1973). «Handel – Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 125. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ George Frideric Handel’s Messiah (Liner notes). David Willcocks, Mormon Tabernacle Choir, NightPro Orchestra. Provo, Utah: NightPro. 1995. NP1001. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Vickers, David; Kemp, Lindsay (10 April 2016). «Classics revisited – Christopher Hogwood’s recording of Handel’s Messiah». Gramophone. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ George Frideric Handel: Messiah (PDF) (Notes). Richard Hickox, Collegium Music 90. Colchester, Essex: Chandos. 1992. 0522(2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Heighes, Simon. Notes to Hyperion CD CDD 22019 Archived 21 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine (1997)

- ^ Finch, Hilary (April 1993). «Handel – Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 109. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ «Handel: Messiah (arranged by Mozart)». Amazon. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ «Handel: Messiah. Röschmann, Gritton, Fink, C. Daniels, N. Davies; McCreesh». Amazon. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ «Handel: Messiah. All recordings». Presto Classical. Archived from the original on 13 January 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ Fiske, Roger (June 1973). «Handel – Messiah». The Gramophone. p. 84. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ^ George Frideric Handel: Messiah. Classic Choral Works. Oxford University Press. 10 September 1998. ISBN 978-0-19-336668-8. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ «Discogs.com discography». Discogs. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ «Andrew Davis website». Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

Sources[edit]

- Armstrong, Karen (1996). A History of Jerusalem. London, England: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-255522-0.

- Bardon, Jonathan (2015). Hallelujah — The Story of a Musical Genius and the City That Brought his Masterpiece to Life. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0717163540.

- Beecham, Sir Thomas (1959). Messiah – An Essay. London, England: RCA. OCLC 29047071. CD 09026-61266-2

- Burrows, Donald (1991). Handel: Messiah. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37620-3.

- Burrows, Donald (1994). Handel. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816470-X.

- Grout, Donald; Palisca, Claude V. (1981). A History of Western Music (3rd ed.). London, England: J M Dent & Sons. ISBN 0-460-04546-6.

- Glover, Jane (2018). Handel in London : the making of a genius. London, England: Picador. ISBN 9781509882083.

- Hicks, Anthony (1991). Handel: Messiah (CD). The Decca Recording Company Ltd. OCLC 25340549. (Origins and the present performance, Edition de L’Oiseau-Lyre 430 488–2)

- Hogwood, Christopher (1991). Handel: Messiah (CD). The Decca Recording Company Ltd. (Notes on the music, Edition de L’Oiseau-Lyre 430 488–2)

- Laurence, Dan H.; Shaw, Bernard, eds. (1981). Shaw’s Music – The Complete Musical Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volume 1 (1876–1890). London, England: The Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-31270-8.

- Laurence, Dan H.; Shaw, Bernard, eds. (1981). Shaw’s Music – The Complete Musical Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volume 2 (1890–1893). London, England: The Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-31271-6.

- Luckett, Richard (1992). Handel’s Messiah: A Celebration. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-05286-4.

- Landon, H. C. Robbins (1990). The Mozart compendium: a guide to Mozart’s life and music. London, England: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01481-7.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Shawe-Taylor, Desmond (1956). The Record Guide. London, England: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Shaw, Watkins (1963). The story of Handel’s «Messiah». London, England: Novello. OCLC 1357436.

- Steen, Michael (2009). The Lives and Times of the Great Composers. London, England: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-679-9.

- Steinberg, Michael (2005). Choral Masterworks: A Listener’s Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512644-0.

- Taylor, Sedley (1906). The Indebtedness of Handel to Works by other Composers. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 23474813.

- Young, Percy M. (1951). Messiah: A Study in Interpretation. London, England: Dennis Dobson. OCLC 643151100.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Messiah.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Messiah (Handel): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Handel’s Messiah at the Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities

- Der Messias, ed. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, K. 572: Score and critical report (in German) in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

| Messiah | |

|---|---|

| Oratorio by George Frideric Handel | |

Title page of Handel’s autograph score |

|

| Text | Charles Jennens, from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer |

| Language | English |

| Composed | 22 August 1741 – 14 September 1741: London |

| Movements | 53 in three parts |

| Vocal | SATB choir and solo |

| Instrumental |

|

Messiah (HWV 56)[1][n 1] is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel. The text was compiled from the King James Bible and the Coverdale Psalter[n 2] by Charles Jennens. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742 and received its London premiere nearly a year later. After an initially modest public reception, the oratorio gained in popularity, eventually becoming one of the best-known and most frequently performed choral works in Western music.

Handel’s reputation in England, where he had lived since 1712, had been established through his compositions of Italian opera. He turned to English oratorio in the 1730s in response to changes in public taste; Messiah was his sixth work in this genre. Although its structure resembles that of opera, it is not in dramatic form; there are no impersonations of characters and no direct speech. Instead, Jennens’s text is an extended reflection on Jesus as the Messiah called Christ. The text begins in Part I with prophecies by Isaiah and others, and moves to the annunciation to the shepherds, the only «scene» taken from the Gospels. In Part II, Handel concentrates on the Passion of Jesus and ends with the Hallelujah chorus. In Part III he covers the resurrection of the dead and Christ’s glorification in Heaven.

Handel wrote Messiah for modest vocal and instrumental forces, with optional settings for many of the individual numbers. In the years after his death, the work was adapted for performance on a much larger scale, with giant orchestras and choirs. In other efforts to update it, its orchestration was revised and amplified, such as Mozart’s Der Messias. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the trend has been towards reproducing a greater fidelity to Handel’s original intentions, although «big Messiah» productions continue to be mounted. A near-complete version was issued on 78 rpm discs in 1928; since then the work has been recorded many times.

Background[edit]

The composer George Frideric Handel, born in Halle, Germany in 1685, took up permanent residence in London in 1712, and became a naturalised British subject in 1727.[3] By 1741 his pre-eminence in British music was evident from the honours he had accumulated, including a pension from the court of King George II, the office of Composer of Musick for the Chapel Royal, and—most unusually for a living person—a statue erected in his honour in Vauxhall Gardens.[4] Within a large and varied musical output, Handel was a vigorous champion of Italian opera, which he had introduced to London in 1711 with Rinaldo. He subsequently wrote and presented more than 40 such operas in London’s theatres.[3]

By the early 1730s public taste for Italian opera was beginning to fade. The popular success of John Gay and Johann Christoph Pepusch’s The Beggar’s Opera (first performed in 1728) had heralded a spate of English-language ballad-operas that mocked the pretensions of Italian opera.[5] With box-office receipts falling, Handel’s productions were increasingly reliant on private subsidies from the nobility. Such funding became harder to obtain after the launch in 1730 of the Opera of the Nobility, a rival company to his own. Handel overcame this challenge, but he spent large sums of his own money in doing so.[6]

Although prospects for Italian opera were declining, Handel remained committed to the genre, but as alternatives to his staged works he began to introduce English-language oratorios.[7] In Rome in 1707–08 he had written two Italian oratorios at a time when opera performances in the city were temporarily forbidden under papal decree.[8] His first venture into English oratorio had been Esther, which was written and performed for a private patron in about 1718.[7] In 1732 Handel brought a revised and expanded version of Esther to the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, where members of the royal family attended a glittering premiere on 6 May. Its success encouraged Handel to write two more oratorios (Deborah and Athalia). All three oratorios were performed to large and appreciative audiences at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford in mid-1733. Undergraduates reportedly sold their furniture to raise the money for the five-shilling tickets.[9]

In 1735 Handel received the text for a new oratorio named Saul from its librettist Charles Jennens, a wealthy landowner with musical and literary interests.[10] Because Handel’s main creative concern was still with opera, he did not write the music for Saul until 1738, in preparation for his 1738–39 theatrical season. The work, after opening at the King’s Theatre in January 1739 to a warm reception, was quickly followed by the less successful oratorio Israel in Egypt (which may also have come from Jennens).[11] Although Handel continued to write operas, the trend towards English-language productions became irresistible as the decade ended. After three performances of his last Italian opera Deidamia in January and February 1741, he abandoned the genre.[12] In July 1741 Jennens sent him a new libretto for an oratorio; in a letter dated 10 July to his friend Edward Holdsworth, Jennens wrote: «I hope [Handel] will lay out his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excell all his former Compositions, as the Subject excells every other subject. The Subject is Messiah».[13]

Synopsis[edit]

In Christian theology, the Messiah is the saviour of humankind. The Messiah (Māšîaḥ) is an Old Testament Hebrew word meaning «the Anointed One», which in New Testament Greek is Christ, a title given to Jesus of Nazareth, known by his followers as «Jesus Christ». Handel’s Messiah has been described by the early-music scholar Richard Luckett as «a commentary on [Jesus Christ’s] Nativity, Passion, Resurrection and Ascension», beginning with God’s promises as spoken by the prophets and ending with Christ’s glorification in heaven.[14] In contrast with most of Handel’s oratorios, the singers in Messiah do not assume dramatic roles; there is no single, dominant narrative voice; and very little use is made of quoted speech. In his libretto, Jennens’s intention was not to dramatise the life and teachings of Jesus, but to acclaim the «Mystery of Godliness»,[15] using a compilation of extracts from the Authorized (King James) Version of the Bible, and from the Psalms included in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.[16]

The three-part structure of the work approximates to that of Handel’s three-act operas, with the «parts» subdivided by Jennens into «scenes». Each scene is a collection of individual numbers or «movements» which take the form of recitatives, arias and choruses.[15] There are two instrumental numbers, the opening Sinfony[n 3] in the style of a French overture, and the pastoral Pifa, often called the «pastoral symphony», at the mid-point of Part I.[18]

In Part I, the Messiah’s coming and the virgin birth are predicted by the Old Testament prophets. The annunciation to the shepherds of the birth of the Christ is represented in the words of Luke’s gospel. Part II covers Christ’s passion and his death, his resurrection and ascension, the first spreading of the gospel through the world, and a definitive statement of God’s glory summarised in the Hallelujah. Part III begins with the promise of redemption, followed by a prediction of the day of judgment and the «general resurrection», ending with the final victory over sin and death and the acclamation of Christ.[19] According to the musicologist Donald Burrows, much of the text is so allusive as to be largely incomprehensible to those ignorant of the biblical accounts.[15] For the benefit of his audiences Jennens printed and issued a pamphlet explaining the reasons for his choices of scriptural selections.[20]

Writing history[edit]

Libretto[edit]

Charles Jennens was born around 1700, into a prosperous landowning family whose lands and properties in Warwickshire and Leicestershire he eventually inherited.[21] His religious and political views—he opposed the Act of Settlement of 1701 which secured the accession to the British throne for the House of Hanover—prevented him from receiving his degree from Balliol College, Oxford, or from pursuing any form of public career. His family’s wealth enabled him to live a life of leisure while devoting himself to his literary and musical interests.[22] Although musicologist Watkins Shaw dismisses Jennens as «a conceited figure of no special ability»,[23] Burrows has written: «of Jennens’s musical literacy there can be no doubt». He was certainly devoted to Handel’s music, having helped to finance the publication of every Handel score since Rodelinda in 1725.[24] By 1741, after their collaboration on Saul, a warm friendship had developed between the two, and Handel was a frequent visitor to the Jennens family estate at Gopsall.[21]