|

|

|

|

| Author | J. K. Rowling |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Mary GrandPré |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Bloomsbury Publishing (UK) Scholastic Press (US) |

| Published | 26 June 1997 – 21 July 2007 (initial publication) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) Audiobook E-book |

| No. of books | 7 |

| Website | www.wizardingworld.com |

Harry Potter is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. The main story arc concerns Harry’s struggle against Lord Voldemort, a dark wizard who intends to become immortal, overthrow the wizard governing body known as the Ministry of Magic and subjugate all wizards and Muggles (non-magical people).

The series was originally published in English by Bloomsbury in the United Kingdom and Scholastic Press in the United States. All versions around the world are printed by Grafica Veneta in Italy.[1] A series of many genres, including fantasy, drama, coming-of-age fiction, and the British school story (which includes elements of mystery, thriller, adventure, horror, and romance), the world of Harry Potter explores numerous themes and includes many cultural meanings and references.[2] According to Rowling, the main theme is death.[3] Other major themes in the series include prejudice, corruption, and madness.[4]

Since the release of the first novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, on 26 June 1997, the books have found immense popularity, positive reviews, and commercial success worldwide. They have attracted a wide adult audience as well as younger readers and are often considered cornerstones of modern young adult literature.[5] As of February 2018, the books have sold more than 500 million copies worldwide, making them the best-selling book series in history, and have been translated into more than eighty languages.[6] The last four books consecutively set records as the fastest-selling books in history, with the final instalment selling roughly 2.7 million copies in the United Kingdom and 8.3 million copies in the United States within twenty-four hours of its release.

The original seven books were adapted into an eight-part namesake film series by Warner Bros. Pictures. In 2016, the total value of the Harry Potter franchise was estimated at $25 billion,[7] making Harry Potter one of the highest-grossing media franchises of all time. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child is a play based on a story co-written by Rowling.

The success of the books and films has allowed the Harry Potter franchise to expand with numerous derivative works, a travelling exhibition that premiered in Chicago in 2009, a studio tour in London that opened in 2012, a digital platform on which J. K. Rowling updates the series with new information and insight, and a pentalogy of spin-off films premiering in November 2016 with Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, among many other developments. Themed attractions, collectively known as The Wizarding World of Harry Potter, have been built at several Universal Parks & Resorts amusement parks around the world.

Plot

Early years

The series follows the life of a boy named Harry Potter. In the first book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Harry lives in a cupboard under the stairs in the house of the Dursleys, his aunt, uncle and cousin. The Dursleys consider themselves perfectly normal, but at the age of eleven, Harry discovers that he is a wizard. He meets a half-giant named Hagrid who invites him to attend the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Harry learns that as a baby, his parents were murdered by the dark wizard Lord Voldemort. When Voldemort attempted to kill Harry, his curse rebounded and Harry survived with a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead.

Harry becomes a student at Hogwarts and is sorted into Gryffindor House. He gains the friendship of Ron Weasley, a member of a large but poor wizarding family, and Hermione Granger, a witch of non-magical, or Muggle, parentage. Harry encounters the school’s potions master, Severus Snape, who displays a dislike for him; the rich pure-blood Draco Malfoy whom he develops an enmity with; and the Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Quirinus Quirrell, who turns out to be allied with Lord Voldemort. The first book concludes with Harry’s confrontation with Voldemort, who, in his quest to regain a body, yearns to gain the power of the Philosopher’s Stone, a substance that bestows everlasting life.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets describes Harry’s second year at Hogwarts. Students are attacked and petrified by an unknown creature; wizards of Muggle parentage are the primary targets. The attacks appear related to the Chamber of Secrets, a fifty-year-old mystery at the school. Harry discovers an ability to speak the snake language Parseltongue, which he learns is rare and associated with the Dark Arts. When Hermione is attacked, Harry and Ron uncover the chamber’s secrets and enter it. Harry discovers that the chamber was opened by Ron’s younger sister, Ginny Weasley, who was possessed by an old diary in her belongings. The memory of Tom Marvolo Riddle, Voldemort’s younger self, resided inside the diary and unleashed the basilisk, an ancient monster that kills those who make direct eye contact. Harry draws the Sword of Gryffindor from the Sorting Hat, slays the basilisk and destroys the diary.

In the third novel, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry learns that he is targeted by Sirius Black, an escaped convict who allegedly assisted in his parents’ murder. As Harry struggles with his reaction to the dementors – creatures guarding the school that feed on despair – he reaches out to Remus Lupin, a new professor who teaches him the Patronus charm. On a windy night, Ron is dragged by a black dog into the Shrieking Shack; Harry and Hermione follow. The dog is revealed to be Sirius Black. Lupin enters the shack and explains that Black was James Potter’s best friend; he was framed by Peter Pettigrew, who hides as Ron’s pet rat, Scabbers. As the full moon rises, Lupin transforms into a werewolf and bounds away; the group chase after him but are surrounded by dementors. They are saved by a mysterious figure who casts a stag Patronus. This is later revealed to be a future version of Harry, who traveled back in time with Hermione using the Time Turner. The duo help Sirius escape on a Hippogriff.

Voldemort returns

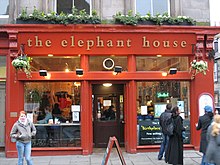

The former 1st floor Nicholson’s Cafe now renamed Spoon in Edinburgh where J. K. Rowling wrote the first few chapters of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

In Harry’s fourth year of school (detailed in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire), he is unwillingly entered in the Triwizard Tournament, a contest between schools of witchcraft and wizardry. Harry is Hogwarts’ second participant after Cedric Diggory, an unusual occurrence that causes his friends to distance themselves from him. He competes against schools Beauxbatons and Durmstrang with the help of the new Defence Against the Dark Arts professor, Alastor «Mad-Eye» Moody. Harry claims the Triwizard Cup with Cedric, but in doing so is teleported to a graveyard where Voldemort’s supporters convene. Moody reveals himself be to Barty Crouch, Jr, a Death Eater. Harry manages to escape, but Cedric is killed and Voldemort is resurrected using Harry’s blood.

In the fifth book, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the Ministry of Magic refuses to believe that Voldemort has returned. Dumbledore re-activates the Order of the Phoenix, a secret society to counter Voldemort; meanwhile, the Ministry appoints Dolores Umbridge as the High Inquisitor of Hogwarts. Umbridge bans the Defense Against the Dark Arts; in response, Hermione and Ron form «Dumbledore’s Army», a secret group where Harry teaches what Umbridge forbids. Harry is punished for disobeying Umbridge, and dreams of a dark corridor in the Ministry of Magic. Near the end of the book, Harry falsely dreams of Sirius being tortured; he races to the Ministry where he faces Death Eaters. The Order of the Phoenix saves the teenagers’ lives, but Sirius is killed. A prophecy concerning Harry and Voldemort is then revealed: one must die at the hands of the other.

In the sixth book, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Snape teaches Defense Against the Dark Arts while Horace Slughorn becomes the Potions master. Harry finds an old textbook with annotations by the Half-Blood Prince, due to which he achieves success in Potions class. Harry also takes lessons with Dumbledore, viewing memories about the early life of Voldemort in a device called a Pensieve. Harry learns from a drunken Slughorn that he used to teach Tom Riddle, and that Voldemort divided his soul into pieces, creating a series of Horcruxes. Harry and Dumbledore travel to a distant lake to destroy a Horcrux; they succeed, but Dumbledore weakens. On their return, they find Draco Malfoy and Death Eaters attacking the school. The book ends with the killing of Dumbledore by Professor Snape, the titular Half-Blood Prince.

In Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh novel in the series, Lord Voldemort gains control of the Ministry of Magic. Harry, Ron and Hermione learn about the Deathly Hallows, legendary items that lead to mastery over death. The group infiltrate the ministry, where they steal a locket Horcrux, and visit Godric’s Hollow, where they are attacked by Nagini. A silver doe Patronus leads them to the Sword of Gryffindor, with which they destroy the locket. They steal a Horcrux from Gringotts and travel to Hogwarts, culminating in a battle with Death Eaters. Snape is killed by Voldemort out of paranoia, but lends Harry his memories before he dies. Harry learns that Snape was always loyal to Dumbledore, and that he himself is a Horcrux. Harry surrenders to Voldemort and dies. The defenders of Hogwarts continue to fight on; Harry is resurrected, faces Voldemort and kills him.

An epilogue titled «Nineteen Years Later» describes the lives of the surviving characters and the impact of Voldemort’s death. Harry and Ginny are married with three children, and Ron and Hermione are married with two children.

Style and allusions

Genre and style

The novels fall into the genre of fantasy literature, and qualify as a type of fantasy called «urban fantasy», «contemporary fantasy», or «low fantasy». They are mainly dramas, and maintain a fairly serious and dark tone throughout, though they do contain some notable instances of tragicomedy and black humour. In many respects, they are also examples of the bildungsroman, or coming of age novel,[8] and contain elements of mystery, adventure, horror, thriller, and romance. The books are also, in the words of Stephen King, «shrewd mystery tales»,[9] and each book is constructed in the manner of a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery adventure. The stories are told from a third person limited point of view with very few exceptions (such as the opening chapters of Philosopher’s Stone, Goblet of Fire and Deathly Hallows and the first two chapters of Half-Blood Prince).

The series can be considered part of the British children’s boarding school genre, which includes Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky & Co., Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers, St. Clare’s and the Naughtiest Girl series, and Frank Richards’s Billy Bunter novels: the Harry Potter books are predominantly set in Hogwarts, a fictional British boarding school for wizards, where the curriculum includes the use of magic.[10] In this sense they are «in a direct line of descent from Thomas Hughes’s Tom Brown’s School Days and other Victorian and Edwardian novels of British public school life», though they are, as many note, more contemporary, grittier, darker, and more mature than the typical boarding school novel, addressing serious themes of death, love, loss, prejudice, coming-of-age, and the loss of innocence in a 1990s British setting.[11][12]

In Harry Potter, Rowling juxtaposes the extraordinary against the ordinary.[13] Her narrative features two worlds: a contemporary world inhabited by non-magical people called Muggles, and another featuring wizards. It differs from typical portal fantasy in that its magical elements stay grounded in the mundane.[14] Paintings move and talk; books bite readers; letters shout messages; and maps show live journeys, making the wizarding world both exotic and familiar.[13][15] This blend of realistic and romantic elements extends to Rowling’s characters. Their names are often onomatopoeic: Malfoy is difficult, Filch unpleasant and Lupin a werewolf.[16][17] Harry is ordinary and relatable, with down-to-earth features such as wearing broken glasses;[18] the scholar Roni Natov terms him an «everychild».[19] These elements serve to highlight Harry when he is heroic, making him both an everyman and a fairytale hero.[18][20]

Each of the seven books is set over the course of one school year. Harry struggles with the problems he encounters, and dealing with them often involves the need to violate some school rules. If students are caught breaking rules, they are often disciplined by Hogwarts professors. The stories reach their climax in the summer term, near or just after final exams, when events escalate far beyond in-school squabbles and struggles, and Harry must confront either Voldemort or one of his followers, the Death Eaters, with the stakes a matter of life and death – a point underlined, as the series progresses, by characters being killed in each of the final four books.[21][22] In the aftermath, he learns important lessons through exposition and discussions with head teacher and mentor Albus Dumbledore. The only exception to this school-centred setting is the final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, in which Harry and his friends spend most of their time away from Hogwarts, and only return there to face Voldemort at the dénouement.[21]

Allusions

The Harry Potter stories feature imagery and motifs drawn from Arthurian myth and fairytales. Harry’s ability to draw the Sword of Gryffindor from the Sorting Hat resembles the Arthurian sword in the stone legend.[23] His life with the Dursleys has been compared to Cinderella.[24] Hogwarts resembles a medieval university-cum-castle with several professors who belong to an Order of Merlin; Old Professor Binns still lectures about the International Warlock Convention of 1289; and a real historical person, a 14th-century scribe, Sir Nicolas Flamel, is described as a holder of the Philosopher’s Stone.[25] Other medieval elements in Hogwarts include coats-of-arms and medieval weapons on the walls, letters written on parchment and sealed with wax, the Great Hall of Hogwarts which is similar to the Great Hall of Camelot, the use of Latin phrases, the tents put up for Quidditch tournaments are similar to the «marvellous tents» put up for knightly tournaments, imaginary animals like dragons and unicorns which exist around Hogwarts, and the banners with heraldic animals for the four Houses of Hogwarts.[25]

Many of the motifs of the Potter stories such as the hero’s quest invoking objects that confer invisibility, magical animals and trees, a forest full of danger and the recognition of a character based upon scars are drawn from medieval French Arthurian romances.[25] Other aspects borrowed from French Arthurian romances include the use of owls as messengers, werewolves as characters, and white deer.[25] The American scholars Heather Arden and Kathrn Lorenz in particular argue that many aspects of the Potter stories are inspired by a 14th-century French Arthurian romance, Claris et Laris, writing of the «startling» similarities between the adventures of Potter and the knight Claris.[25] Arden and Lorenz noted that Rowling graduated from the University of Exeter in 1986 with a degree in French literature and spent a year living in France afterwards.[25]

Like C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, Harry Potter also contains Christian symbolism and allegory. The series has been viewed as a Christian moral fable in the psychomachia tradition, in which stand-ins for good and evil fight for supremacy over a person’s soul.[26] Children’s literature critic Joy Farmer sees parallels between Harry and Jesus Christ.[27] Comparing Rowling with Lewis, she argues that «magic is both authors’ way of talking about spiritual reality».[28] According to Maria Nikolajeva, Christian imagery is particularly strong in the final scenes of the series: Harry dies in self-sacrifice and Voldemort delivers an «ecce homo» speech, after which Harry is resurrected and defeats his enemy.[29]

Rowling stated that she did not reveal Harry Potter‘s religious parallels in the beginning because doing so would have «give[n] too much away to fans who might then see the parallels».[30] In the final book of the series Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Rowling makes the book’s Christian imagery more explicit, quoting both Matthew 6:21 and 1 Corinthians 15:26 (King James Version) when Harry visits his parents’ graves.[30] Hermione Granger teaches Harry Potter that the meaning of these verses from the Christian Bible are «living beyond death. Living after death», which Rowling states «epitomize the whole series».[30][31][32] Rowling also exhibits Christian values in developing Albus Dumbledore as a God-like character, the divine, trusted leader of the series, guiding the long-suffering hero along his quest. In the seventh novel, Harry speaks with and questions the deceased Dumbledore much like a person of faith would talk to and question God.[33]

Themes

Harry Potter‘s overarching theme is death.[34][35] In the first book, when Harry looks into the Mirror of Erised, he feels both joy and «a terrible sadness» at seeing his desire: his parents, alive and with him.[36] Confronting their loss is central to Harry’s character arc and manifests in different ways through the series, such as in his struggles with Dementors.[36][37] Other characters in Harry’s life die; he even faces his own death in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[38] The series has an existential perspective – Harry must grow mature enough to accept death.[39] In Harry’s world, death is not binary but mutable, a state that exists in degrees.[40] Unlike Voldemort, who evades death by separating and hiding his soul in seven parts, Harry’s soul is whole, nourished by friendship and love.[39]

Love distinguishes Harry and Voldemort. Harry is a hero because he loves others, even willing to accept death to save them; Voldemort is a villain because he does not.[41] Harry carries the protection of his mother’s sacrifice in his blood; Voldemort, who wants Harry’s blood and the protection it carries, does not understand that love vanquishes death.[27]

Rowling has spoken about thematising death and loss in the series. Soon after she started writing Philosopher’s Stone, her mother died; she said that «I really think from that moment on, death became a central, if not the central theme of the seven books».[42] Rowling has described Harry as «the prism through which I view death», and further stated that «all of my characters are defined by their attitude to death and the possibility of death».[43]

While Harry Potter can be viewed as a story about good vs. evil, its moral divisions are not absolute.[44][45] First impressions of characters are often misleading. Harry assumes in the first book that Quirrell is on the side of good because he opposes Snape, who appears to be malicious; in reality, Quirrell is an agent of Voldemort, while Snape is loyal to Dumbledore. This pattern later recurs with Moody and Snape.[44] In Rowling’s world, good and evil are choices rather than inherent attributes: second chances and the possibility of redemption are key themes of the series.[46][47] This is reflected in Harry’s self-doubts after learning his connections to Voldemort, such as Parseltongue;[46] and prominently in Snape’s characterisation, which has been described as complex and multifaceted.[48] In some scholars’ view, while Rowling’s narrative appears on the surface to be about Harry, her focus may actually be on Snape’s morality and character arc.[49][50]

Rowling said that, to her, the moral significance of the tales seems «blindingly obvious». In the fourth book, Dumbledore speaks of a «choice between what is right and what is easy»; Rowling views this as a key theme, «because that … is how tyranny is started, with people being apathetic and taking the easy route and suddenly finding themselves in deep trouble».[51]

Academics and journalists have developed many other interpretations of themes in the books, some more complex than others, and some including political subtexts. Themes such as normality, oppression, survival, and overcoming imposing odds have all been considered as prevalent throughout the series.[52] Similarly, the theme of making one’s way through adolescence and «going over one’s most harrowing ordeals – and thus coming to terms with them» has also been considered.[53] Rowling has stated that the books comprise «a prolonged argument for tolerance, a prolonged plea for an end to bigotry» and that they also pass on a message to «question authority and… not assume that the establishment or the press tells you all of the truth».[54]

Development history

In 1990, Rowling was on a crowded train from Manchester to London when the idea for Harry suddenly «fell into her head». Rowling gives an account of the experience on her website saying:

«I had been writing almost continuously since the age of six but I had never been so excited about an idea before. I simply sat and thought, for four (delayed train) hours, and all the details bubbled up in my brain, and this scrawny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who did not know he was a wizard became more and more real to me.»

Rowling completed Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 1995 and the manuscript was sent off to several prospective agents.[56] The second agent she tried, Christopher Little, offered to represent her and sent the manuscript to several publishers.[57]

Publishing history

The logo used in British, Australian, and Canadian editions before 2010, which uses the typeface Cochin Bold[58]

After twelve other publishers had rejected Philosopher’s Stone, Bloomsbury agreed to publish the book.[59] Despite Rowling’s statement that she did not have any particular age group in mind when beginning to write the Harry Potter books, the publishers initially targeted children aged nine to eleven.[60] On the eve of publishing, Rowling was asked by her publishers to adopt a more gender-neutral pen name in order to appeal to the male members of this age group, fearing that they would not be interested in reading a novel they knew to be written by a woman. She elected to use J. K. Rowling (Joanne Kathleen Rowling), using her grandmother’s name as her second name because she has no middle name.[61][62]

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was published by Bloomsbury, the publisher of all Harry Potter books in the United Kingdom, on 26 June 1997.[63] It was released in the United States on 1 September 1998 by Scholastic – the American publisher of the books – as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,[64] after the American rights sold for US$105,000 – a record amount for a children’s book by an unknown author.[65] Scholastic feared that American readers would not associate the word «philosopher» with magic, and Rowling suggested the title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone for the American market.[66] Rowling has later said that she regrets the change.[67]

The second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, was originally published in the UK on 2 July 1998 and in the US on 2 June 1999. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was published a year later in the UK on 8 July 1999 and in the US on 8 September 1999.[68] Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire was published on 8 July 2000 at the same time by Bloomsbury and Scholastic.[69] Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is the longest book in the series, at 766 pages in the UK version and 870 pages in the US version.[70] It was published worldwide in English on 21 June 2003.[71] Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was published on 16 July 2005.[72][73] The seventh and final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was published on 21 July 2007.[74] Rowling herself has stated that the last chapter of the final book (in fact, the epilogue) was completed «in something like 1990».[75]

Rowling retained rights to digital editions and released them on the Pottermore website in 2012. Vendors such as Amazon displayed the ebooks in the form of links to Pottermore, which controlled pricing.[76] All seven Harry Potter books have been released in unabridged audiobook versions, with Stephen Fry reading the UK editions and Jim Dale voicing the series for the American editions.[77][78]

Translations

The Russian translation of The Deathly Hallows goes on sale in Moscow, 2007.

The series has been translated into more than 80 languages,[6] placing Rowling among the most translated authors in history. The books have seen translations to diverse languages such as Korean, Armenian, Ukrainian, Arabic, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Bulgarian, Welsh, Afrikaans, Albanian, Latvian, Vietnamese and Hawaiian. The first volume has been translated into Latin and even Ancient Greek,[79] making it the longest published work in Ancient Greek since the novels of Heliodorus of Emesa in the 3rd century AD.[80] The second volume has also been translated into Latin.[81]

Some of the translators hired to work on the books were well-known authors before their work on Harry Potter, such as Viktor Golyshev, who oversaw the Russian translation of the series’ fifth book. The Turkish translation of books two to seven was undertaken by Sevin Okyay, a popular literary critic and cultural commentator.[82] For reasons of secrecy, translation on a given book could only start after it had been released in English, leading to a lag of several months before the translations were available. This led to more and more copies of the English editions being sold to impatient fans in non-English speaking countries; for example, such was the clamour to read the fifth book that its English language edition became the first English-language book ever to top the best-seller list in France.[83]

The United States editions were adapted into American English to make them more understandable to a young American audience.[84]

Cover art

For cover art, Bloomsbury chose painted art in a classic style of design, with the first cover a watercolour and pencil drawing by illustrator Thomas Taylor showing Harry boarding the Hogwarts Express, and a title in the font Cochin Bold.[85] The first releases of the successive books in the series followed in the same style but somewhat more realistic, illustrating scenes from the books. These covers were created by first Cliff Wright and then Jason Cockroft.[86]

Due to the appeal of the books among an adult audience, Bloomsbury commissioned a second line of editions in an ‘adult’ style. These initially used black-and-white photographic art for the covers showing objects from the books (including a very American Hogwarts Express) without depicting people, but later shifted to partial colourisation with a picture of Slytherin’s locket on the cover of the final book.[citation needed]

International and later editions have been created by a range of designers, including Mary GrandPré for U.S. audiences and Mika Launis in Finland.[87][88] For a later American release, Kazu Kibuishi created covers in a somewhat anime-influenced style.[89][90]

Reception

Commercial success

The popularity of the Harry Potter series has translated into substantial financial success for Rowling, her publishers, and other Harry Potter related license holders. This success has made Rowling the first and thus far only billionaire author.[91] The books have sold more than 500 million copies worldwide and have also given rise to the popular film adaptations produced by Warner Bros., all of which have been highly successful in their own right.[92][93] The total revenue from the book sales is estimated to be around $7.7 billion.[94] The first novel in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, has sold in excess of 120 million copies, making it one of the bestselling books in history.[95][96] The films have in turn spawned eight video games and have led to the licensing of more than 400 additional Harry Potter products. The Harry Potter brand has been estimated to be worth as much as $25 billion.[7]

The great demand for Harry Potter books motivated The New York Times to create a separate best-seller list for children’s literature in 2000, just before the release of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. By 24 June 2000, Rowling’s novels had been on the list for 79 straight weeks; the first three novels were each on the hardcover best-seller list.[97] On 12 April 2007, Barnes & Noble declared that Deathly Hallows had broken its pre-order record, with more than 500,000 copies pre-ordered through its site.[98] For the release of Goblet of Fire, 9,000 FedEx trucks were used with no other purpose than to deliver the book.[99] Together, Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble pre-sold more than 700,000 copies of the book.[99] In the United States, the book’s initial printing run was 3.8 million copies.[99] This record statistic was broken by Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, with 8.5 million, which was then shattered by Half-Blood Prince with 10.8 million copies.[100] Within the first 24 hours of its release, 6.9 million copies of Prince were sold in the U.S.; in the United Kingdom more than two million copies were sold on the first day.[101] The initial U.S. print run for Deathly Hallows was 12 million copies, and more than a million were pre-ordered through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.[102]

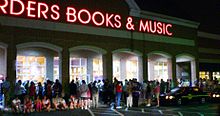

Fans of the series were so eager for the latest instalment that bookstores around the world began holding events to coincide with the midnight release of the books, beginning with the 2000 publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The events, commonly featuring mock sorting, games, face painting, and other live entertainment have achieved popularity with Potter fans and have been highly successful in attracting fans and selling books with nearly nine million of the 10.8 million initial print copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince sold in the first 24 hours.[103][104]

The final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows became the fastest selling book in history, moving 11 million units in the first twenty-four hours of release.[105] The book sold 2.7 million copies in the UK and 8.3 million in the US.[73] The series has also gathered adult fans, leading to the release of two editions of each Harry Potter book, identical in text but with one edition’s cover artwork aimed at children and the other aimed at adults.[106]

Literary criticism

Early in its history, Harry Potter received positive reviews. On publication, the first book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, attracted attention from the Scottish newspapers, such as The Scotsman, which said it had «all the makings of a classic»,[107] and The Glasgow Herald, which called it «Magic stuff».[107] Soon the English newspapers joined in, with The Sunday Times comparing it to Roald Dahl’s work («comparisons to Dahl are, this time, justified»),[107] while The Guardian called it «a richly textured novel given lift-off by an inventive wit».[107]

By the time of the release of the fifth book, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the books began to receive strong criticism from a number of literary scholars. Yale professor, literary scholar, and critic Harold Bloom raised criticisms of the books’ literary merits, saying, «Rowling’s mind is so governed by clichés and dead metaphors that she has no other style of writing.»[108] A. S. Byatt authored an op-ed article in The New York Times calling Rowling’s universe a «secondary secondary world, made up of intelligently patchworked derivative motifs from all sorts of children’s literature … written for people whose imaginative lives are confined to TV cartoons, and the exaggerated (more exciting, not threatening) mirror-worlds of soaps, reality TV and celebrity gossip.»[109]

Michael Rosen, a novelist and poet, advocated the books were not suited for children, as they would be unable to grasp the complex themes. Rosen also stated that «J. K. Rowling is more of an adult writer.»[110] The critic Anthony Holden wrote in The Observer on his experience of judging Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban for the 1999 Whitbread Awards. His overall view of the series was negative – «the Potter saga was essentially patronising, conservative, highly derivative, dispiritingly nostalgic for a bygone Britain,» and he speaks of «a pedestrian, ungrammatical prose style».[111] Ursula K. Le Guin said, «I have no great opinion of it […] it seemed a lively kid’s fantasy crossed with a ‘school novel,’ good fare for its age group, but stylistically ordinary, imaginatively derivative, and ethically rather mean-spirited.»[112] By contrast, author Fay Weldon, while admitting that the series is «not what the poets hoped for», nevertheless goes on to say, «but this is not poetry, it is readable, saleable, everyday, useful prose.»[113]

The literary critic A. N. Wilson praised the Harry Potter series in The Times, stating, «There are not many writers who have JK’s Dickensian ability to make us turn the pages, to weep – openly, with tears splashing – and a few pages later to laugh, at invariably good jokes … We have lived through a decade in which we have followed the publication of the liveliest, funniest, scariest and most moving children’s stories ever written.»[114] Charles Taylor of Salon.com, who is primarily a movie critic,[115] took issue with Byatt’s criticisms in particular. While he conceded that she may have «a valid cultural point – a teeny one – about the impulses that drive us to reassuring pop trash and away from the troubling complexities of art»,[116] he rejected her claims that the series is lacking in serious literary merit and that it owes its success merely to the childhood reassurances it offers.[116] Stephen King called the series «a feat of which only a superior imagination is capable», and declared «Rowling’s punning, one-eyebrow-cocked sense of humor» to be «remarkable». However, he wrote that he is «a little tired of discovering Harry at home with his horrible aunt and uncle», the formulaic beginning of all seven books.[9][117]

Sameer Rahim of The Daily Telegraph disagreed, saying «It depresses me to see 16- and 17-year-olds reading the series when they could be reading the great novels of childhood such as Oliver Twist or A House for Mr Biswas.»[118] The Washington Post book critic Ron Charles opined in July 2007 that «through no fault of Rowling’s», the cultural and marketing «hysteria» marked by the publication of the later books «trains children and adults to expect the roar of the coliseum, a mass-media experience that no other novel can possibly provide».[119] Jenny Sawyer wrote in The Christian Science Monitor on 25 July 2007 that Harry Potter neither faces a «moral struggle» nor undergoes any ethical growth, and is thus «no guide in circumstances in which right and wrong are anything less than black and white».[120] In contrast Emily Griesinger described Harry’s first passage through to Platform 9+3⁄4 as an application of faith and hope, and his encounter with the Sorting Hat as the first of many in which Harry is shaped by the choices he makes.[121]

In an 8 November 2002 Slate article, Chris Suellentrop likened Potter to a «trust-fund kid whose success at school is largely attributable to the gifts his friends and relatives lavish upon him».[122] In a 12 August 2007, review of Deathly Hallows in The New York Times, however, Christopher Hitchens praised Rowling for «unmooring» her «English school story» from literary precedents «bound up with dreams of wealth and class and snobbery», arguing that she had instead created «a world of youthful democracy and diversity».[123]

In 2016, an article written by Diana C. Mutz compares the politics of Harry Potter to the 2016 Donald Trump presidential campaign. She suggests that these themes are also present in the presidential election and it may play a significant role in how Americans have responded to the campaign.[124]

There is ongoing discussion regarding the extent to which the series was inspired by Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books.[125]

Thematic critique

The portrayal of women in Harry Potter has been described as complex and varied, but nonetheless conforming to stereotypical and patriarchal depictions of gender.[126] Gender divides are ostensibly absent in the books: Hogwarts is coeducational and women hold positions of power in wizarding society. However, this setting obscures the typecasting of female characters and the general depiction of conventional gender roles.[127] According to scholars Elizabeth Heilman and Trevor Donaldson, the subordination of female characters goes further early in the series. The final three books «showcase richer roles and more powerful females»: for instance, the series’ «most matriarchal character», Molly Weasley, engages substantially in the final battle of Deathly Hallows, while other women are shown as leaders.[128] Hermione Granger, in particular, becomes an active and independent character essential to the protagonists’ battle against evil.[129] Yet, even particularly capable female characters such as Hermione and Minerva McGonagall are placed in supporting roles,[130] and Hermione’s status as a feminist model is debated.[131] Girls and women are more frequently shown as emotional, more often defined by their appearance, and less often given agency in family settings.[127][132]

The social hierarchy of wizards in Rowling’s world has drawn debate among critics. «Purebloods» have two wizard parents; «half-bloods» have one; and «Muggle-born» wizards have magical abilities although neither of their parents is a wizard.[133] Lord Voldemort and his followers believe that blood purity is paramount and that Muggles are subhuman.[134] According to the literary scholar Andrew Blake, Harry Potter rejects blood purity as a basis for social division;[135] Suman Gupta agrees that Voldemort’s philosophy represents «absolute evil»;[136] and Nel and Eccleshare agree that advocates of racial or blood-based hierarchies are antagonists.[137][138] Gupta, following Blake,[139] suggests that the essential superiority of wizards over Muggles – wizards can use magic and Muggles cannot – means that the books cannot coherently reject anti-Muggle prejudice by appealing to equality between wizards and Muggles. Rather, according to Gupta, Harry Potter models a form of tolerance based on the «charity and altruism of those belonging to superior races» towards lesser races.[140]

Harry Potter‘s depiction of race, specifically the slavery of house-elves, has received varied responses. Scholars such as Brycchan Carey have praised the books’ abolitionist sentiments, viewing Hermione’s Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare as a model for younger readers’ political engagement.[141][142] Other critics including Farah Mendlesohn find the portrayal of house-elves «most difficult to accept»: the elves are denied the right to free themselves and rely on the benevolence of others like Hermione.[143][144] Pharr terms the house-elves a disharmonious element in the series, writing that Rowling leaves their fate hanging;[145] at the end of Deathly Hallows, the elves remain enslaved and cheerful.[146] The goblins of the world of Harry Potter have also been accused of perpetuating antisemitic caricatures – they are described by Rowling as a «secretive cabal of hook-nosed, greedy bankers», a description associated with Jewish stereotypes.[147][148][149]

Controversies

The books have been the subject of a number of legal proceedings, stemming from various conflicts over copyright and trademark infringements. The popularity and high market value of the series has led Rowling, her publishers, and film distributor Warner Bros. to take legal measures to protect their copyright, which have included banning the sale of Harry Potter imitations, targeting the owners of websites over the «Harry Potter» domain name, and suing author Nancy Stouffer to counter her accusations that Rowling had plagiarised her work.[150][151][152]

Various religious fundamentalists have claimed that the books promote witchcraft and religions such as Wicca and are therefore unsuitable for children,[153][154][155] while a number of critics have criticised the books for promoting various political agendas.[156][157] The series has landed the American Library Associations’ Top 10 Banned Book List in 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2019 with claims it was anti-family, discussed magic and witchcraft, contained actual spells and curses, referenced the occult/Satanism, violence, and had characters who used «nefarious means» to attain goals, as well as conflicts with religious viewpoints.[158]

The books also aroused controversies in the literary and publishing worlds. From 1997 to 1998, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone won almost all the UK awards judged by children, but none of the children’s book awards judged by adults,[159] and Sandra Beckett suggested the reason was intellectual snobbery towards books that were popular among children.[160] In 1999, the winner of the Whitbread Book of the Year award children’s division was entered for the first time on the shortlist for the main award, and one judge threatened to resign if Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was declared the overall winner; it finished second, very close behind the winner of the poetry prize, Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf.[160]

In 2000, shortly before the publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the previous three Harry Potter books topped The New York Times fiction best-seller list and a third of the entries were children’s books. The newspaper created a new children’s section covering children’s books, including both fiction and non-fiction, and initially counting only hardback sales. The move was supported by publishers and booksellers.[97] In 2004, The New York Times further split the children’s list, which was still dominated by Harry Potter books, into sections for series and individual books, and removed the Harry Potter books from the section for individual books.[161] The split in 2000 attracted condemnation, praise and some comments that presented both benefits and disadvantages of the move.[162] Time suggested that, on the same principle, Billboard should have created a separate «mop-tops» list in 1964 when the Beatles held the top five places in its list, and Nielsen should have created a separate game-show list when Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? dominated the ratings.[163]

Legacy

Influence on literature

Harry Potter transformed children’s literature.[164][165] In the 1970s, children’s books were generally realistic as opposed to fantastic,[166] while adult fantasy became popular because of the influence of The Lord of the Rings.[167] The next decade saw an increasing interest in grim, realist themes, with an outflow of fantasy readers and writers to adult works.[168][169]

The commercial success of Harry Potter in 1997 reversed this trend.[170] The scale of its growth had no precedent in the children’s market: within four years, it occupied 28% of that field by revenue.[171] Children’s literature rose in cultural status,[172] and fantasy became a dominant genre.[173] Older works in the genre, including Diana Wynne Jones’s Chrestomanci series and Diane Duane’s Young Wizards, were reprinted and rose in popularity; some authors re-established their careers.[174] In the following decades, many Harry Potter imitators and subversive responses grew popular.[175][176]

Rowling has been compared to Enid Blyton, who also wrote in simple language about groups of children and long held sway over the British children’s market.[177][178] She has also been described as an heir to Roald Dahl.[179] Some critics view Harry Potter‘s rise, along with the concurrent success of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, as part of a broader shift in reading tastes: a rejection of literary fiction in favour of plot and adventure.[180] This is reflected in the BBC’s 2003 «Big Read» survey of the UK’s favourite books, where Pullman and Rowling ranked at numbers 3 and 5, respectively, with very few British literary classics in the top 10.[181]

Cultural impact

Harry Potter has been described as a cultural phenomenon.[182][183] The word «Muggle» has spread beyond its origins in the books, entering the Oxford English Dictionary in 2003.[184]

A real-life version of the sport Quidditch was created in 2005 and featured as an exhibition tournament in the 2012 London Olympics.[185] Characters and elements from the series have inspired scientific names of several organisms, including the dinosaur Dracorex hogwartsia, the spider Eriovixia gryffindori, the wasp Ampulex dementor, and the crab Harryplax severus.[186]

Librarian Nancy Knapp pointed out the books’ potential to improve literacy by motivating children to read much more than they otherwise would.[187] The seven-book series has a word count of 1,083,594 (US edition). Agreeing about the motivating effects, Diane Penrod also praised the books’ blending of simple entertainment with «the qualities of highbrow literary fiction», but expressed concern about the distracting effect of the prolific merchandising that accompanies the book launches.[188] However, the assumption that Harry Potter books have increased literacy among young people is «largely a folk legend».[189]

Research by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has found no increase in reading among children coinciding with the Harry Potter publishing phenomenon, nor has the broader downward trend in reading among Americans been arrested during the rise in the popularity of the Harry Potter books.[189][190] The research also found that children who read Harry Potter books were not more likely to go on to read outside the fantasy and mystery genres.[189] NEA chairman Dana Gioia said the series, «got millions of kids to read a long and reasonably complex series of books. The trouble is that one Harry Potter novel every few years is not enough to reverse the decline in reading.»[191]

Many fan fiction and fan art works about Harry Potter have been made. In March 2007, «Harry Potter» was the most commonly searched fan fiction subject on the internet.[192]

Jennifer Conn used Snape’s and Quidditch coach Madam Hooch’s teaching methods as examples of what to avoid and what to emulate in clinical teaching,[193] and Joyce Fields wrote that the books illustrate four of the five main topics in a typical first-year sociology class: «sociological concepts including culture, society, and socialisation; stratification and social inequality; social institutions; and social theory».[194]

From the early 2000s onwards several news reports appeared in the UK of the Harry Potter book and movie series driving demand for pet owls[195] and even reports that after the end of the movie series these same pet owls were now being abandoned by their owners.[196] This led J. K. Rowling to issue several statements urging Harry Potter fans to refrain from purchasing pet owls.[197] Despite the media flurry, research into the popularity of Harry Potter and sales of owls in the UK failed to find any evidence that the Harry Potter franchise had influenced the buying of owls in the country or the number of owls reaching animal shelters and sanctuaries.[198]

Awards, honours, and recognition

The Harry Potter series has been recognised by a host of awards since the initial publication of Philosopher’s Stone including a platinum award from the Whitaker Gold and Platinum Book Awards ( 2001),[199][200] three Nestlé Smarties Book Prizes (1997–1999),[201] two Scottish Arts Council Book Awards (1999 and 2001),[202] the inaugural Whitbread children’s book of the year award (1999),[203] the WHSmith book of the year (2006),[204] among others. In 2000, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novel, and in 2001, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire won said award.[205] Honours include a commendation for the Carnegie Medal (1997),[206] a short listing for the Guardian Children’s Award (1998), and numerous listings on the notable books, editors’ Choices, and best books lists of the American Library Association, The New York Times, Chicago Public Library, and Publishers Weekly.[207]

In 2002, sociologist Andrew Blake named Harry Potter a British pop culture icon along with the likes of James Bond and Sherlock Holmes.[208] In 2003, four of the books were named in the top 24 of the BBC’s The Big Read survey of the best loved novels in the UK.[209] A 2004 study found that books in the series were commonly read aloud in elementary schools in San Diego County, California.[210] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Education Association listed the series in its «Teachers’ Top 100 Books for Children».[211] Time magazine named Rowling as a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year award, noting the social, moral, and political inspiration she has given her fandom.[212] Three of the books placed among the «Top 100 Chapter Books» of all time, or children’s novels, in a 2012 survey published by School Library Journal: Sorcerer’s Stone ranked number three, Prisoner of Azkaban 12th, and Goblet of Fire 98th.[213]

In 2007, the seven Harry Potter book covers were depicted on a series of UK postage stamps issued by Royal Mail.[214] In 2012, the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London featured a 100-foot tall rendition of Lord Voldemort in a segment designed to showcase the UK’s cultural icons.[215] In November 2019, the BBC listed the Harry Potter series on its list of the 100 most influential novels.[216]

Adaptations

Films

The locomotive that features as the «Hogwarts Express» in the film series

In 1999, Rowling sold the film rights for Harry Potter to Warner Bros. for a reported $1 million.[217][218]

Rowling had creative control on the film series, observing the filmmaking process of Philosopher’s Stone and serving as producer on the two-part Deathly Hallows, alongside David Heyman and David Barron.[219] Rowling demanded the principal cast be kept strictly British, nonetheless allowing for the inclusion of Irish or French and Eastern European actors where characters from the book are specified as such.[220]

Chris Columbus was selected as the director for Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (titled «Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone» in the United States).[221] Philosopher’s Stone was released on 14 November 2001. Just three days after the film’s release, production for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, also directed by Columbus, began and the film was released on 15 November 2002.[222] Columbus declined to direct Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, only acting as producer. Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón took over the job, and after shooting in 2003, the film was released on 4 June 2004. Due to the fourth film beginning its production before the third’s release, Mike Newell was chosen as the director for Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, released on 18 November 2005.[223] Newell became the first British director of the series, with television director David Yates following suit after he was chosen to helm Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Production began in January 2006 and the film was released the following year in July 2007.[224] Yates was selected to direct Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, which was released on 15 July 2009.[225][226] The final instalment in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was released in two cinematic parts: Part 1 on 19 November 2010 and Part 2 on 15 July 2011.[227][228]

Spin-off prequels

A new prequel series consisting of five films will take place before the main series.[229] The first film Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them was released in November 2016, followed by the second Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald in November 2018 and Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore in April 2022 with two more to be released. Rowling wrote the screenplay for the first three instalments,[230] marking her foray into screenwriting.

Games

A number of non-interactive media games and board games have been released such as Cluedo Harry Potter Edition, Scene It? Harry Potter and Lego Harry Potter models, which are influenced by the themes of both the novels and films.

There are thirteen Harry Potter video games, eight corresponding with the films and books and five spin-offs. The film/book-based games are produced by Electronic Arts (EA), as was Harry Potter: Quidditch World Cup, with the game version of the first entry in the series, Philosopher’s Stone, being released in November 2001. Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone went on to become one of the best-selling PlayStation games ever.[231] The video games were released to coincide with the films. Objectives usually occur in and around Hogwarts. The story and design of the games follow the selected film’s characterisation and plot; EA worked closely with Warner Bros. to include scenes from the films. The last game in the series, Deathly Hallows, was split, with Part 1 released in November 2010 and Part 2 debuting on consoles in July 2011.[232][233]

The spin-off games Lego Harry Potter: Years 1–4 and Lego Harry Potter: Years 5–7 were developed by Traveller’s Tales and published by Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment. The spin-off games Book of Spells and Book of Potions were developed by London Studio and use the Wonderbook, an augmented reality book designed to be used in conjunction with the PlayStation Move and PlayStation Eye.[234] The Harry Potter universe is also featured in Lego Dimensions, with the settings and side characters featured in the Harry Potter Adventure World, and Harry, Voldemort, and Hermione as playable characters. In 2017, Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment opened its own Harry Potter-themed game design studio, by the name of Portkey Games, before releasing Hogwarts Mystery in 2018, developed by Jam City.[235]

Stage production

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: Parts I and II is a play which serves as a sequel to the books, beginning nineteen years after the events of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. It was written by Jack Thorne based on an original new story by Thorne, Rowling and John Tiffany.[236] It has run at the Palace Theatre in London’s West End since previews began on 7 June 2016 with an official premiere on 30 June 2016.[237] The first four months of tickets for the June–September performances were sold out within several hours upon release.[238] Forthcoming productions are planned for Broadway[239] and Melbourne.[240]

The script was released as a book at the time of the premiere, with a revised version following the next year.

Television

On 25 January 2021, a live action television series was reported to have been in early development at HBO Max. Though it was noted that the series has «complicated rights issues», due to a seven-year rights deal with Warner Bros. Domestic TV Distribution that included U.S. broadcast, cable and streaming rights to the franchise, which ends in April 2025.[241]

Attractions

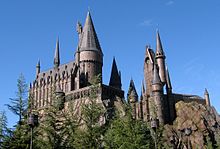

Hogwarts Castle as depicted in the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, located in Universal Orlando Resort’s Island of Adventure

Universal and Warner Brothers created The Wizarding World of Harry Potter, a Harry Potter-themed expansion to the Islands of Adventure theme park at Universal Orlando Resort in Florida. It opened to the public on 18 June 2010.[242] It includes a re-creation of Hogsmeade and several rides; its flagship attraction is Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey, which exists within a re-creation of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.[243]

In 2014 Universal opened a Harry Potter-themed area at the Universal Studios Florida theme park. It includes a re-creation of Diagon Alley.[244] The flagship attraction is the Harry Potter and the Escape from Gringotts roller coaster ride.[245] A completely functioning full-scale replica of the Hogwarts Express was created for the Diagon Alley expansion, connecting King’s Cross Station at Universal Studios to the Hogsmeade station at Islands of Adventure.[246][247] The Wizarding World of Harry Potter opened at the Universal Studios Hollywood theme park near Los Angeles, California in 2016,[248][249] and in Universal Studios Japan theme park in Osaka, Japan in 2014. The Osaka venue includes the village of Hogsmeade, Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey ride, and Flight of the Hippogriff roller coaster.[250][251]

The Making of Harry Potter is a behind-the-scenes walking tour in London featuring authentic sets, costumes and props from the film series. The attraction is located at Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden, where all eight of the Harry Potter films were made. Warner Bros. constructed two new sound stages to house and showcase the sets from each of the British-made productions, following a £100 million investment.[252] It opened to the public in March 2012.[253]

Supplementary works

Rowling expanded the Harry Potter universe with short books produced for charities.[254][255] In 2001, she released Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (a purported Hogwarts textbook) and Quidditch Through the Ages (a book Harry reads for fun). Proceeds from the sale of these two books benefited the charity Comic Relief.[256] In 2007, Rowling composed seven handwritten copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, a collection of fairy tales that is featured in the final novel, one of which was auctioned to raise money for the Children’s High Level Group, a fund for mentally disabled children in poor countries. The book was published internationally on 4 December 2008.[257][258] Rowling also wrote an 800-word prequel in 2008 as part of a fundraiser organised by the bookseller Waterstones.[259] All three of these books contain extra information about the wizarding world not included in the original novels.

In 2016, she released three new e-books: Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide, Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists

and Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies.[260]

Rowling’s website Pottermore was launched in 2012.[261] Pottermore allows users to be sorted, be chosen by their wand and play various minigames. The main purpose of the website was to allow the user to journey through the story with access to content not revealed by JK Rowling previously, with over 18,000 words of additional content.[262] The site was redesigned in 2015 as Wizardingworld.com and it mainly focuses on the information already available, rather than exploration.[263][verification needed]

See also

- The Worst Witch

- Mary Poppins

References

- ^ «In uscita l’ottavo Harry Potter, Grafica Veneta è ancora la tipografia di fiducia del maghetto». Padova Oggi (in Italian). 22 September 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Sources that refer to the many genres, cultural meanings and references of the series include:

- Fry, Stephen (10 December 2005). «Living with Harry Potter». BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2005.

- Jensen, Jeff (7 September 2000). «Why J.K. Rowling waited to read Harry Potter to her daughter». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Nancy Carpentier Brown (2007). «The Last Chapter» (PDF). Our Sunday Visitor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- J. K. Rowling. «J. K. Rowling at the Edinburgh Book Festival». Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Greig, Geordie (11 January 2006). «There would be so much to tell her…» The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Mzimba, Lizo (28 July 2008). «Interview with Steve Kloves and J.K. Rowling». Quick Quotes Quill. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

- ^ Allsobrook, Dr. Marian (18 June 2003). «Potter’s place in the literary canon». BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 January 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ a b «Harry Potter’s 25th anniversary». The Economist. 26 June 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ a b Meyer, Katie (6 April 2016). «Harry Potter’s $25 Billion Magic Spell». Money. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Anne Le Lievre, Kerrie (2003). «Wizards and wainscots: generic structures and genre themes in the Harry Potter series». CNET Networks. Retrieved 1 September 2008.[dead link]

- ^ a b King, Stephen (23 July 2000). «Wild About Harry». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

…the Harry Potter books are, at heart, satisfyingly shrewd mystery tales.

- ^ «Harry Potter makes boarding fashionable». BBC News. 13 December 1999. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Ellen Jones, Leslie (2003). JRR Tolkien: A Biography. Greenwood Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-313-32340-9.

- ^ A Whited, Lana (2004). The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon. University of Missouri Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8262-1549-9.

- ^ a b Natov 2002, p. 129.

- ^ Butler 2012, pp. 233–34.

- ^ Butler 2012, p. 234.

- ^ Park 2003, p. 183.

- ^ Natov 2002, p. 130.

- ^ a b Nikolajeva 2008, p. 233.

- ^ Ostry 2003, p. 97.

- ^ Ostry 2003, pp. 90, 97–98.

- ^ a b Grossman, Lev (28 June 2007). «Harry Potter’s Last Adventure». Time. Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ «Two characters to die in last ‘Harry Potter’ book: J.K. Rowling». CBC. 26 June 2006. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Alton 2008, p. 216.

- ^ Gallardo & Smith 2003, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d e f Arden, Heather; Lorenz, Kathryn (June 2003). «The Harry Potter Stories and French Arthurian Romance». Arthuriana. 13 (12): 54–68. doi:10.1353/art.2003.0005. JSTOR 27870516. S2CID 161603742.

- ^ Singer 2016, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Farmer 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Farmer 2001, p. 55.

- ^ Nikolajeva 2008, pp. 238–39.

- ^ a b c Adler, Shawn (17 October 2007). «‘Harry Potter’ Author J.K. Rowling Opens Up About Books’ Christian Imagery». MTV. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Sedlmayr, Gerold; Waller, Nicole (28 October 2014). Politics in Fantasy Media: Essays on Ideology and Gender in Fiction, Film, Television and Games. McFarland & Company. p. 132. ISBN 9781476617558.

During this press conference, Rowling stated that the Bible quotations in that novel «almost epitomize the whole series. I think they sum up all the themes in the whole series» (reported in Adler).

- ^ Falconer, Rachel (21 October 2008). The Crossover Novel: Contemporary Children’s Fiction and Its Adult Readership. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 9781135865016.

These New Testament verses (Matthew 6:19 and 1 Corinthians 15:26) together denote the promise of resurrection through the Son of God’s consent to die.52 In interview, Rowling has stressed that these two quotations ‘sum up – they almost epitomize the whole series’.

- ^ Cooke, Rachel. «ProQuest Ebook Central». CC Advisor. doi:10.5260/cca.199425.

- ^ Ciaccio 2008, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Groves 2017, pp. xxi–xxii, 135–136.

- ^ a b Natov 2002, pp. 134–36.

- ^ Taub & Servaty-Seib 2008, pp. 23–27.

- ^ Pharr 2016, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Los 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Stojilkov 2015, p. 135.

- ^ Pharr 2016, pp. 14–15, 20–21.

- ^ Groves 2017, p. 138.

- ^ Groves 2017, p. 135.

- ^ a b Shanoes 2003, pp. 131–32.

- ^ McEvoy 2016, p. 207.

- ^ a b Doughty 2002, pp. 247–49.

- ^ Berberich 2016, p. 153.

- ^ Birch 2008, pp. 110–13.

- ^ Nikolajeva 2016, p. 204.

- ^ Applebaum 2008, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Max, Wyman (26 October 2000). ««You can lead a fool to a book but you cannot make them think»: Author has frank words for the religious right». The Vancouver Sun. p. A3. ProQuest 242655908.

- ^ Greenwald, Janey; Greenwald, J (Fall 2005). «Understanding Harry Potter: Parallels to the Deaf World» (Free full text). The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 10 (4): 442–450. doi:10.1093/deafed/eni041. PMID 16000691.

- ^ Duffy, Edward (2002). «Sentences in Harry Potter, Students in Future Writing Classes». Rhetoric Review. 21 (2): 177. doi:10.1207/S15327981RR2102_03. S2CID 144654506.

- ^ «JK Rowling outs Dumbledore as gay». BBC News. 21 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ^ Rowling, JK (2006). «Biography». JKRowling.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 21 May 2006.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 73.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 156, 159–161.

- ^ «Harry Potter Books (UK Editions) Terms and Conditions for Use of Images for Book Promotion» (PDF). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Huler, Scott. «The magic years». The News & Observer. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Savill, Richard (21 June 2001). «Harry Potter and the mystery of J K’s lost initial». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ «Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone». Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ «Wild about Harry». NYP Holdings, Inc. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Rozhon, Tracie (21 April 2007). «A Brief Walk Through Time at Scholastic». The New York Times. p. C3. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ Errington 2017, p. 145.

- ^ Whited 2015, pp. 75.

- ^ «A Potter timeline for muggles». Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ «Speed-reading after lights out». London: Guardian News and Media Limited. 19 July 2000. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (14 July 2003). «Harry Potter and the Internet Pirates». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ Cassy, John (16 January 2003). «Harry Potter and the hottest day of summer». The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ «July date for Harry Potter book». BBC News. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ a b «Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m». BBC News. 23 July 2007. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ «Rowling unveils last Potter date». BBC News. 1 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ «Rowling to kill two in final book». BBC News. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ Clark & Phillips 2019, p. 47.

- ^ Rich, Mokoto (17 July 2007). «The Voice of Harry Potter Can Keep a Secret». The New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ «Harry Potter Audiobooks and E-Books». Mugglenet. Dose Media. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (2006). «Harry Potter in Greek». Andrew Wilson. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Castle, Tim (2 December 2004). «Harry Potter? It’s All Greek to Me». Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ LTD, Skyron. «Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Latin)». Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Güler, Emrah (2005). «Not lost in translation: Harry Potter in Turkish». The Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ «OOTP is best seller in France – in English!». BBC News. 1 July 2003. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ «Differences in the UK and US Versions of Four Harry Potter Books». FAST US-1. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Taylor, Thomas (26 July 2012). «Me and Harry Potter». Thomas Taylor (author site). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (20 January 2002). «Harry Potter beats Austen in sale rooms». The Observer. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows; American edition; Scholastic Corporation; 2007; Final credits page

- ^ «Illustrator puts a bit of herself on Potter cover: GrandPré feels pressure to create something special with each book». Today.com. Associated Press. 8 March 2005. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Liu, Jonathan H. (13 February 2013). «New Harry Potter Covers by Kazu Kibuishi». Wired. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Hall, April (15 August 2014). «5 Questions With… Kazu Kibuishi (Amulet series)». www.reading.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Watson, Julie (26 February 2004). «J. K. Rowling and the Billion-Dollar Empire». Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ «All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses». Box Office Mojo. 1998–2008. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Eyre, Charlotte (1 February 2018). «Harry Potter book sales top 500 million worldwide». The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018.

- ^ «The Billion Dollar Business Behind ‘Harry Potter’ Franchise». entrepreneur. 18 November 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ Chalton, Nicola; Macardle, Meredith (15 March 2017). 20th Century in Bite-Sized Chunks. Book Sales. ISBN 978-0-7858-3510-3.

- ^ «Burbank Public Library offering digital copies of first ‘Harry Potter’ novel to recognize the book’s 20th anniversary». Burbank Leader. 5 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ a b Smith, Dinitia (24 June 2000). «The Times Plans a Children’s Best-Seller List». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ «New Harry Potter breaks pre-order record». RTÉ.ie Entertainment. 13 April 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Fierman, Daniel (21 July 2000). «Wild About Harry». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

When I buy the books for my grandchildren, I have them all gift wrapped but one…that’s for me. And I have not been 12 for over 50 years.

- ^ «Harry Potter hits midnight frenzy». CNN. 15 July 2005. Archived from the original on 21 December 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ «Worksheet: Half-Blood Prince sets UK record». BBC News. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ «Record print run for final Potter». BBC News. 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ Freeman, Simon (18 July 2005). «Harry Potter casts spell at checkouts». The Times. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ «Potter book smashes sales records». BBC News. 18 July 2005. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ «‘Harry Potter’ tale is fastest-selling book in history». The New York Times. 23 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ «Harry Potter at Bloomsbury Publishing – Adult and Children Covers». Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d Eccleshare 2002, p. 10

- ^ Bloom, Harold (24 September 2003). «Dumbing down American readers». The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 17 June 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ^ Byatt, A. S. (7 July 2003). «Harry Potter and the Childish Adult». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ Sweeney, Charlene (19 May 2008). «Harry Potter ‘is too boring and grown-up for young readers’«. The Times. London. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (25 June 2000). «Why Harry Potter does not cast a spell over me». The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ «Chronicles of Earthsea». The Guardian. London. 9 February 2004. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Allison, Rebecca (11 July 2003). «Rowling books ‘for people with stunted imaginations’«. The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ Wilson, A. N. (29 July 2007). «Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by JK Rowling». The Times. London. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ «Salon Columnist». Salon.com. 2000. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ a b Taylor, Charles (8 July 2003). «A. S. Byatt and the goblet of bile». Salon.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ Fox, Killian (31 December 2006). «JK Rowling: The mistress of all she surveys». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Rahim, Sameer (13 April 2012). «The Casual Vacancy: why I’m dreading JK Rowling’s adult novel». The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Charles, Ron (15 July 2007). «Harry Potter and the Death of Reading». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Sawyer, Jenny (25 July 2007). «Missing from ‘Harry Potter» – a real moral struggle». The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Griesinger, E. (2002). «Harry Potter and the «deeper magic»: narrating hope in children’s literature». Christianity and Literature. 51 (3): 455–480. doi:10.1177/014833310205100308.

- ^ Suellentrop, Chris (8 November 2002). «Harry Potter: Fraud». Slate. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (12 August 2007). «The Boy Who Lived». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ C. Mutz, Diana (2016). «Harry Potter and the Deathly Donald». Elections in Focus. 49. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Wetherill, Louise. «Harry Potter: Merely Frodo Baggins with a Wand?», in Ampthill Literary Festival Yearbook 2015. Ampthill: Literary Festival Committee, 2015. ISBN 978-1-5175506-8-4, pp. 85–92.

- ^ Heilman & Donaldson 2008, pp. 139–41; Pugh & Wallace 2006; Eberhardt 2017.

- ^ a b Pugh & Wallace 2006.

- ^ Heilman & Donaldson 2008, pp. 139–41.

- ^ Berents 2012, pp. 144–49.

- ^ Heilman & Donaldson 2008, pp. 142–47.

- ^ Bell & Alexander 2012, pp. 1–8.

- ^ Heilman & Donaldson 2008, pp. 149–55.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Barratt 2012, pp. 63, 67.

- ^ Blake 2002, p. 103.

- ^ Gupta 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Nel 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Eccleshare 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Gupta 2009, p. 105.

- ^ Gupta 2009, pp. 108–10.

- ^ Carey 2003, pp. 105–107, 114.

- ^ Horne 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Mendlesohn 2002, pp. 178–181.

- ^ Horne 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Pharr 2016, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Levy, Marianne. «Is this picture of Harry Potter’s goblin bankers offensive?». The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Richer, Stephen (14 July 2011). «Debunking the Harry Potter Antisemitism Myth». Moment Magazine. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Berlatsky, Noah. «Opinion | Why most people still miss these antisemitic tropes in «Harry Potter»«. NBC News. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «Scholastic Inc, J.K. Rowling and Time Warner Entertainment Company, L.P, Plaintiffs/Counterclaim Defendants, -against- Nancy Stouffer: United States District Court for the Southern District of New York». ICQ. 17 September 2002. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- ^ McCarthy, Kieren (2000). «Warner Brothers bullying ruins Field family Xmas». The Register. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2007.

- ^ «Fake Harry Potter novel hits China». BBC News. 4 July 2002. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ O’Kane, Caitlin. Nashville school bans «Harry Potter» series, citing risk of «conjuring evil spirits». CBS News. Retrieved on 3 September 2019. «Rev. Reehil believes, ‘The curses and spells used in the books are actual curses and spells; which when read by a human being risk conjuring evil spirits into the presence of the person reading the text.’ It is unclear if the movies have been banned, since they don’t require children to read spells.» Archived from the original

- ^ Reading Harry Potter: critical essays – Page 54, Giselle Liza Anatol – 2003

- ^ Espinoza, Javier (16 December 2015). «Religious parents want Harry Potter banned from the classroom because it ‘glorifies witchcraft’«. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Bonta, Steve (28 January 2002). «Tolkien’s Timeless Tale». The New American. Vol. 18, no. 2.