|

Внимание!

Информация в этой статье (или разделе) содержит спойлеры из пьесы «Гарри Поттер и Проклятое дитя»! |

[Просмотр]

Волан-де-Морт и Гарри Поттер[3]

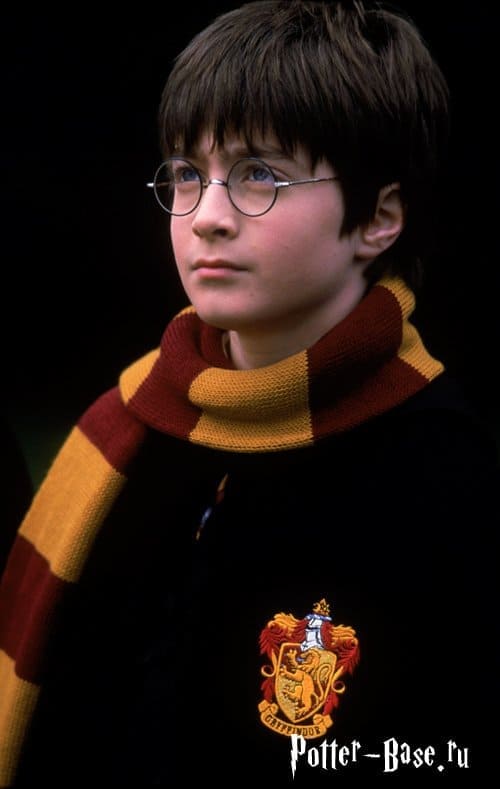

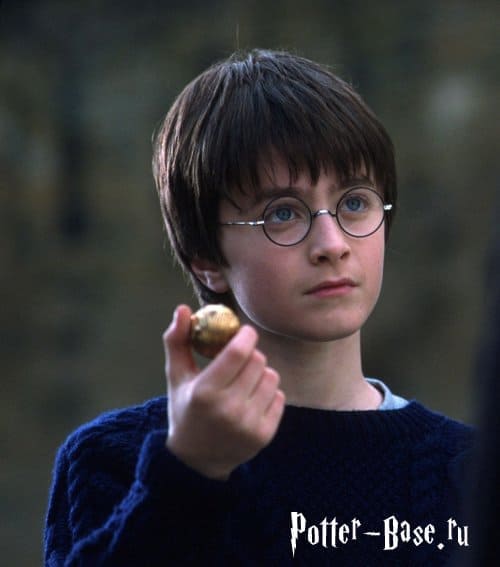

Гарри Джеймс Поттер (англ. Harry James Potter) — главный герой Поттерианы, одноклассник и лучший друг Рона Уизли и Гермионы Грейнджер, член Золотого Трио. Самый знаменитый студент Хогвартса за последние сто лет. Первый волшебник, которому удалось противостоять смертельному проклятью «Авада Кедавра», благодаря чему он стал знаменитым и получил прозвище «Мальчик, Который Выжил». Героически сражался с лордом Волан-де-Мортом и его последователями Пожирателями смерти. Единственный, кому удалось дважды остаться живым после шести поединков с Тёмным Лордом и кто, в конце концов, победил его. Обладатель специальной награды Хогвартса «За заслуги перед школой», полученной в 1993 году за спасение школы от чудовища Тайной комнаты — василиска.

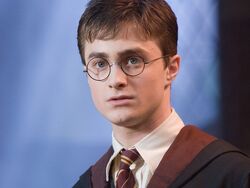

Внешний вид

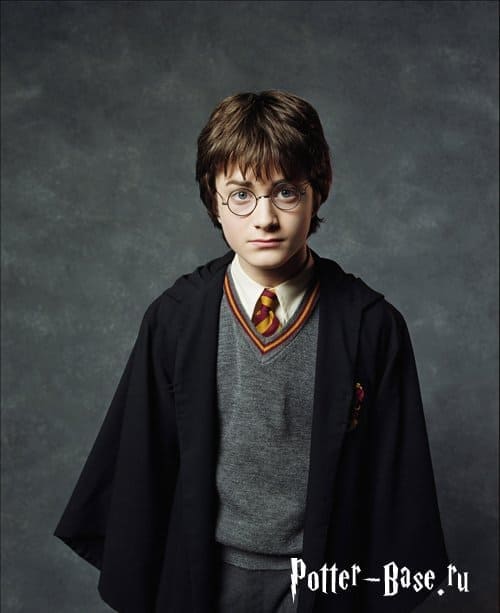

Гарри Поттер внешне — вылитый отец (для Сириуса словно воскресший друг), лишь его зелёные глаза похожи на глаза матери (в фильме у исполнителя роли Гарри Поттера Дэниела Рэдклиффа глаза голубые). Гарри маленький и худой, он выглядит чуть младше своего возраста, с чёрными, вечно взъерошенными волосами, худощавым лицом и торчащими коленками. Он носит очки с круглой оправой. На лбу Гарри находится знаменитый шрам в виде молнии[4], который у него остался от проклятия «Авада Кедавра».

Характер

Гарри Поттер

В начале повествования Гарри — одинокий, замкнутый ребёнок, который постоянно подвергается унижениям в семье и в школе. Сложная жизнь у Дурслей формирует у него такую черту, как недоверчивость. Когда в его жизни появляется Хагрид, мальчик до последнего сомневается в происходящем.

В первый год обучения в Хогвартсе, где Гарри наконец-таки ощущает себя полноценным человеком, определяются основные черты его характера, как положительные, так и отрицательные.

Гарри добр, серьёзно относится к любым человеческим отношениям, никогда не предаст близкого человека, с уважением относится ко взрослым, которые, конечно, это уважение заслужили. Он никогда не нападает первым, напротив, ему самому часто приходится отбиваться от нападок. Гарри по своей натуре лидер, и если ему приходится чем-либо руководить (быть капитаном квиддичной команды или руководителем Отряда Дамблдора), у него это вполне прилично получается. Гарри никогда не кичится своей известностью, наоборот, собственная слава его раздражает. Он малообщителен, и несмотря на то, что ему поневоле приходится контактировать с большим количеством людей, близкие отношения его связывают лишь с несколькими. Гарри достаточно скрытен, он никогда не делится со своими чувствами и переживаниями даже с близкими друзьями.

Гарри Поттер — «человек первого впечатления». Если кто-либо не понравился (или наоборот, понравился) ему с первого взгляда, он очень неохотно пересматривает своё к нему отношение. Правда, он всегда легко и даже с радостью прощает обидчика, если только он скажет: «Извини, Гарри, я был глубоко не прав». Так произошло с Роном[5], так случилось год спустя с Симусом, это повторилось с Дадли[6]… Гарри не может абстрагироваться от собственных эмоций и опираться только на факты как Римус Люпин, он не умеет цепко замечать детали как Гермиона Грейнджер, он не умеет относиться ко всему с юмором как близнецы Уизли. Но зато он способен глубоко и сильно любить людей и предчувствовать то, что невозможно объяснить словами. «Следуй всегда своей интуиции, — говорит ему однажды Люпин[6], — она тебя почти никогда не обманывает».

Биография

Происхождение

Гарри Поттер — потомок Певереллов, старинной магической семьи, к которой имеет отношение и Том Реддл. Впрочем, кровь братьев Певереллов, по словам самой Джоан Роулинг, течёт в каждом, кто обладает магическими способностями. Сам Гарри узнал о том, что он потомок Игнотуса Певерелла, когда понял, что Мантия-невидимка, доставшаяся ему от отца, на самом деле насчитывает несколько веков истории и является одним из Даров Смерти. Также известно, что Том Реддл — потомок Кадма Певерелла по линии Мраксов, владевших другой реликвией — Воскрешающим камнем. Таким образом, сам Гарри и Волан-де-Морт имеют общие древние корни.

Гарри Поттер с отцовской стороны состоит в родстве с семейством Блэков, а через них — с половиной магических семейств Англии. С материнской стороны состоит в родстве с магловским семейством Дурслей.

Начало жизни

Мальчик, который выжил

Гарри Джеймс Поттер родился 31 июля 1980 года у волшебников Джеймса и Лили Поттеров. После рождения сына семья жила в укрытии, поскольку стало известно, что лорд Волан-де-Морт охотится за Гарри (см. «Пророчество»). Они жили в Годриковой впадине под защитой заклинания Фиделиус. Лучший друг Джеймса Поттера Сириус Блэк являлся крёстным отцом Гарри, и вначале планировали сделать хранителем его, но, по совету самого Сириуса, в последний момент и тайком ото всех сделали им Питера Петтигрю, который, как они считали, мог вызвать меньше подозрений. В этом была их фатальная ошибка, так как Петтигрю к этому моменту переметнулся к Волан-де-Морту. Он выдал место, где прятались Джеймс и Лили, Тёмному Лорду и тем обрёк их на смерть, а заодно и подставил Сириуса Блэка, который стал в глазах всех предателем.

Вечером 31 октября 1981 года Тёмный Лорд появился в Годриковой впадине, чтобы убить Гарри. Джеймс пытался защитить семью, но погиб. Когда Волан-де-Морт уже собрался убить ребёнка, Лили встала на его пути, закрывая своим телом кроватку малыша. Безоружная, она кричала, что пусть лучше Тёмный Лорд убьёт её, а не сына. Волан-де-Морт, который сначала собирался оставить Лили в живых по просьбе Северуса Снегга, убил её, устраняя препятствие. Как он думал. Но магический контракт был произнесён и заключён, (убив Лили, Тёмный Лорд согласился с условиями этого контракта) и подписан материнской кровью, которую он пролил. Своею смертью Лили создала несокрушимый барьер для своего сына. И когда Волан-де-Морт применил убивающее заклятие к ребёнку, оно отразилось от него, и Волан-де-Морт потерял всю свою силу и исчез. Так Гарри стал единственным, кому удалось испытать на себе заклятье Авада Кедавра и выжить после этого. На память о событиях в Годриковой Впадине ему остался только шрам в виде молнии.

Гарри вечером 31 октября 1981 года

Гарри стал знаменит в магическом мире именно тем, что нанёс поражение Волан-де-Морту, когда ему был всего лишь год. То есть, сделал то, что не удавалось на протяжении нескольких лет самым разным, в том числе и выдающимся волшебникам. В результате схватки дом в Годриковой Впадине был разрушен. Рубеус Хагрид вынес малютку Поттера из руин и по распоряжению Альбуса Дамблдора доставил его в дом Дурслей, тёти Петунии и дяди Вернона, родственников Гарри со стороны матери. Дамблдор оставил письмо, в котором объяснял Дурслям обстоятельства, при которых их племянник оказался сиротой. Но они никогда не обсуждали это с мальчиком. Супруги Дурсль договорились между собой, что попытаются оградить племянника от «всей этой опасной чепухи» и, полагая, что утаивание правды как-то защитит Гарри, ничего ему не говорили о родителях. Более того, они считали, что чем меньше мальчик получает удовольствий, тем лучше и «правильней» он вырастет. Так Гарри провёл десять несчастливых лет в строгом доме дяди и тёти, ничего не зная о своих родителях, будучи уверен, что они погибли в автокатастрофе (так ему сказали) и даже не догадываясь, что он сын волшебников.

Жизнь вместе с Дурслями была ужасной. Ну, по крайней мере, так её воспринимает Гарри. Нет, Поттера не морили голодом, не избивали каждый день и даже позволяли иногда смотреть телевизор. Но всё же мальчик чувствовал себя в доме дяди и тёти так, будто был грязной вонючей собакой, неизвестно зачем забредшей в этот чистенький дом.

При всём этом Дурсли до безумия любили и всячески баловали своего сына Дадли. Гарри был вынужден донашивать вещи после него, а так как Дадли был слишком большим и толстым, Поттер всегда носил мешковатую одежду. Хотя младший Дурсль имел целых две спальни (одну он использовал как кладовку для поломанных игрушек), Гарри проводил ночи под лестницей в крохотном чулане. Чувствуя отношение родителей к кузену, Дадли регулярно задирал его, при каждом удобном случае бил мальчика и науськивал на него своих дружков.

Позже Гарри узнал, что нахождение в этом «доме-тюрьме» было необходимо. Его мать перед смертью дала ему непреодолимую защиту. Защиту собственной, материнской крови. И тётя Петуния, которая была её родной сестрой, приняв сироту в свой дом, поддержала эту защиту. Таким образом для Волан-де-Морта и его приспешников Гарри был недоступен, но эта защита могла действовать либо до наступления совершеннолетия, либо до того момента, когда Поттер перестанет считать дом на Тисовой улице своим домом.

За Гарри в Литтл Уингинге приглядывала соседка, миссис Фигг. Когда Дурслям надо было всей семьёй уехать из дома, мальчика оставляли на её попечении. Каково же было удивление Гарри, когда он узнал, что эта сумасшедшая кошатница — сквиб, и что она работает на Орден Феникса.

Ты волшебник, Гарри

Письма из камина

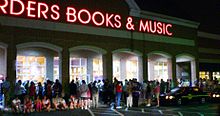

Дни рождения Гарри в доме Дурслей никогда не отмечали, но незадолго до одиннадцатилетия ему прислали письмо из Хогвартса, которое сильно напугало его дядю и тётю. На конверте стоял подозрительно точный адрес: «чулан под лестницей», и Дурсли поспешили переселить племянника в самую маленькую спальню. Письмо они ему не отдали, надеясь, что всё утрясётся как-нибудь само собой. Но письма продолжали приходить, и чем дальше, тем их было больше. Пытаясь скрыться от неизвестного, который так жаждет пообщаться с маленьким Поттером, дядя Вернон, в конце концов, укрылся со всем семейством на скалистом острове в утлой хижине.

Рубеус Хагрид принёс Гарри письмо. Теперь Дурсли не смогут помешать прочесть его

Это происходило как раз накануне 31 июля, дня рождения Гарри. Ровно в полночь, в грозу в хижину явился Рубеус Хагрид и лично принёс письмо из Хогвартса. Он рассказал мальчику о том, как умерли его родители на самом деле, и что он с рождения зачислен в Школу чародейства и волшебства, а наутро забрал Гарри с собой в Лондон, чтобы купить всё необходимое для учёбы.

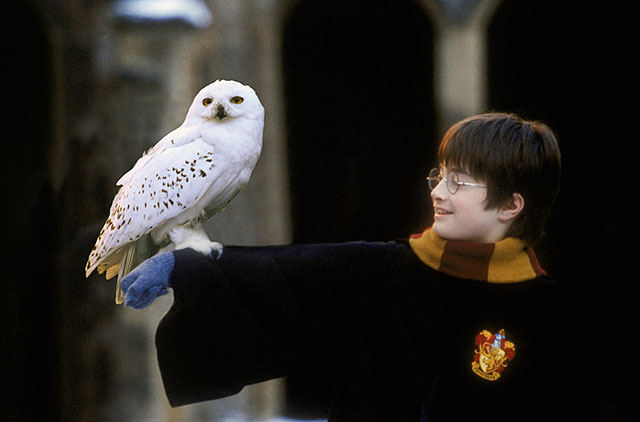

Это был первый день рождения, когда Гарри получил настоящие подарки. Хагрид специально для мальчика испёк торт и позже купил ему сову, которой Гарри дал имя Букля. В Косом Переулке Гарри убедился, что знаменит среди магического сообщества. Также он познакомился с Драко Малфоем и с первой же встречи невзлюбил его, так как своей заносчивостью и спесивостью он очень напоминал кузена Дадли, а кроме того, оскорбил Хагрида (не зная, что Гарри знаком с ним) — первого и единственного на тот момент друга Поттера. Ещё Гарри узнал, что родители оставили ему приличное состояние, которое хранится в ячейке магического банка Гринготтс.

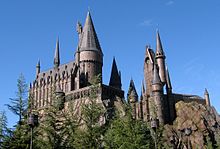

Первый год в Хогвартсе

Первый год Гарри в Хогвартсе

Месяц спустя — 1 сентября, перед самым отъездом в Хогвартс, Гарри встретился с Молли Уизли и её детьми — Джинни, Фредом, Джорджем, Перси и Роном. Когда Гарри сел на Хогвартс-экспресс, к нему в купе присоединился Рон со своим питомцем — крысой Коростой. Позже к ребятам заглянули Гермиона Грейнджер и Невилл Долгопупс. С ними в дальнейшем Гарри Поттер подружился на всю жизнь.

В Хогвартсе первокурсников встретила декан факультета Гриффиндор — Минерва Макгонагалл. Гарри, Рона, Гермиону, Невилла и некоторых других первокурсников Распределяющая шляпа определила в Гриффиндор. По завершении пира в честь начала нового учебного года, ученики спели гимн Хогвартса, после чего старосты отвели первокурсников своих факультетов в их гостиные.

Босой Гарри и Букля на подоконнике в Хогвартсе, ночь с 1 на 2 сентября 1991 года

Гарри неплохо освоился в школе, а в умении летать на метле проявил такие способности, что его приняли в команду Гриффиндора по квиддичу. Так он стал самым юным ловцом за последние сто лет.

На Хэллоуин в Хогвартс проник тролль. Перед этим Гермиона, обиженная Роном, не пошла на пир, а заперлась в туалете, куда в итоге и забрёл монстр. Гарри и Рон бросились спасать Гермиону и одолели тролля. Этот случай скрепил их дружбу навек. А впереди у них было ещё немало интересных и опасных приключений…

Рон, Гарри и Гермиона Гарри и Рон на первом курсе

Между тем, давно исчезнувший лорд Волан-де-Морт, как выяснится в дальнейшем, тайно возвратился в Хогвартс. Для этого он использовал тело профессора защиты от Тёмных искусств Квиринуса Квиррелла, в которое вселился как паразит. Хозяин и его слуга пытались заполучить Философский камень, решив с его помощью восстановить тело Тёмного Лорда. Однако, в самом конце учебного года планы Волан-де-Морта были расстроены Гарри Поттером, которому помогли друзья — Рон и Гермиона. Общими усилиями им удалось отсрочить возвращение сил тьмы.

Второй год в Хогвартсе

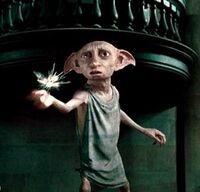

Добби шпионит за Гарри

В свой двенадцатый день рождения, в доме дяди и тёти, Гарри неожиданно встретился со странным существом по имени Добби, сообщившем мальчику о том, что в Хогвартсе в новом учебном году ему будет угрожать большая опасность и настаивавшем на том, что Поттер не должен возвращаться в школу. Гарри ответил решительным отказом, после чего новый знакомый навлёк на него крупные неприятности, и кто знает, чем бы всё закончилось, если бы в одну прекрасную ночь за Поттером не прибыли на летающем автомобиле братья Уизли, забравшие друга к себе в «Нору», где он и провёл остаток каникул.

В Хогвартсе преподавателем по ЗОТИ стал Златопуст Локонс, известный многочисленными подвигами, описанными в его собственных книгах. Между тем, слова Добби начали подтверждаться. В Хогвартсе стали происходить страшные события: объявился некий «наследник Слизерина», который открыл Тайную комнату и выпустил оттуда ужас Слизерина, чтобы «очистить школу от грязнокровок». Вначале кошка Филча, а потом несколько учеников и даже привидение Гриффиндора оказались на больничной койке в парализованном состоянии.

Неожиданно для всех, в том числе и для самого Гарри, стало известно, что Поттер говорит на Парселтанге, змеином языке. Большинство учеников начало подозревать мальчика в том, что он и есть наследник Слизерина, а Гарри, Рон и Гермиона в свою очередь заподозрили Драко Малфоя и даже перевоплотились с помощью оборотного зелья в его друзей, чтобы всё выяснить. Однако оказалось, что Драко не являлся наследником Слизерина. Вскоре одной из жертв очередного нападения стала сама Гермиона. Министерство магии возложило вину на Рубеуса Хагрида, отправив его в Азкабан. Но лесничий успел дать Гарри и Рону подсказку; воспользовавшись ей, мальчики попали в логово акромантулов и узнали от Арагога, что Хагрид не открывал Тайную комнату. (Правда, спастись оттуда им удалось лишь чудом: Арагог запретил паукам нападать на Хагрида, но на его друзей это не распространялось.)

В действительности происходившие события имели совсем иную подоплёку: сестра Рона Джинни Уизли попала под влияние дневника Тома Реддла (он был подброшен ей Люциусом Малфоем в книжном магазине). Часть души Реддла, заключённая в дневнике, заставляла девочку выпускать из Комнаты василиска, натравливать его на учеников, писать кровью послания на стене и делать всякие другие, мягко говоря, нехорошие вещи. При этом Джинни не осознавала, что делает: целые часы жизни просто вылетали у неё из памяти («Кто-то перебил всех петухов, а кровь и перья почему-то на моей мантии»)…

В результате поисков, Гарри, при поддержке Рона и Гермионы, удалось найти Тайную комнату и проникнуть туда, использовав змеиный язык. Попутно Рон и Гарри выяснили, что Локонс на самом деле не совершал никаких подвигов, а лишь присваивал заслуги других волшебников. Гарри узнал что встреченный им в Тайной комнате призрачный Том Реддл и Волан-де-Морт это одно и тоже лицо, и именно он является наследником Слизерина. Реддл попытался прикончить мальчика, напустив на него василиска. Но Гарри с помощью меча Годрика Гриффиндора и феникса Фоукса смог победить монстра и, воспользовавшись его же ядовитым клыком, уничтожить дневник Тома. Это спасло едва не погибшую Джинни, призрак же Реддла бесследно исчез. В заключение Поттер, прибегнув к хитрости, ещё и освободил домашнего эльфа Добби от его деспотичного хозяина Люциуса Малфоя.

Третий год в Хогвартсе

Гарри получает Карту Мародёров

С Римусом в кабинете ЗОТИ

В пабе «Три метлы» под мантией невидимкой

Гарри и Сириус без сознания

В 1993 году Сириусу Блэку удалось сбежать из Азкабана. Все считали, что именно Гарри Поттер является его целью, что Блэк жаждет отомстить ему за падение Тёмного лорда. В связи с этим Министерство магии усилило охрану Хогвартса и выставило вокруг замка посты дементоров.

С этого года Гарри мог бы ходить в Хогсмид, деревню рядом с Хогвартсом, населённую исключительно магами, если бы Дурсли подписали ему письменное разрешение. Но те так и не подписали и не подпишут уже никогда… К счастью, Гарри получил в подарок от Фреда и Джорджа Уизли «карту Мародёров» — магическую карту Хогвартса, где показаны все закоулки замка и окрестностей и на которой видно, кто и куда перемещается. Используя мантию-невидимку и показанный на Карте потайной ход, Гарри несколько раз пробирался в Хогсмид.

Во время матча «Гриффиндор-Пуффендуй» у Гарри сломалась его старая метла, «Нимбус-2000», но на Рождество мальчик получил от кого-то в подарок «Молнию», последнюю модель гоночной метлы международного класса. Гермиона Грейнджер заподозрила, что метла прислана Сириусом Блэком, желающим погубить мальчика, но, как оказалось, она не содержит в себе ничего опасного. В это время Гарри узнал, что Сириус — не только его крёстный, он ещё и был лучшим другом его отца. И то, что Блэк попал в Азкабан за выдачу секретного убежища Поттеров врагу и убийство их общего друга Питера, потрясло его до глубины души. Гарри жаждал мести. Однако спустя время он узнал правду: Сириус невиновен, а Поттеров предал Петтигрю, который подставил Сириуса. Являясь незарегистрированным анимагом, Питер все эти годы скрывался в виде крысы Коросты в семье Уизли. После того, как всё всплыло наружу, Питер сбежал, а в это время Гарри оказался вынужден спасать Сириуса от нападения дементоров, вызвав патронуса, а затем организовывать его побег. В итоге, не без помощи Гарри и Гермионы, Сириусу удалось покинуть Хогвартс, хотя он по-прежнему был вынужден скрываться от Министерства магии.

Четвёртый год в Хогвартсе

Гарри пытается уйти от венгерской хвостороги во время первого задания на Турнире трёх волшебников

В 1994 году Хогвартс принимал возобновлённый Турнир Трёх Волшебников, для участия в котором прибыли ученики Шармбатона и Дурмстранга. Кубок Огня должен был выбрать трёх Чемпионов — по одному от каждой школы, но, по неизвестным причинам, он выбрал ещё и Гарри, которому пришлось участвовать наравне со всеми. С этого момента его жизнь изменилась в худшую сторону: все обвиняли его в мошенничестве, и даже Рон разделял это мнение. Положение изменилось только после первого испытания, когда всем стало ясно: тот, кто подкинул имя Гарри в Кубок, хотел его смерти.

Гарри и Парвати на Святочном балу

В финальном состязании Гарри и Седрик Диггори прошли лабиринт практически одновременно. Поэтому вместе взялись за Кубок Турнира, думая, что это конец Турнира. Но кубок оказался порталом, который переместил мальчиков на большое расстояние от Хогвартса — на кладбище. Там их уже поджидали Волан-де-Морт и Питер Петтигрю, по приказу своего хозяина убивший Седрика. Оказалось, что Гарри был нужен Тёмному Лорду для тёмного ритуала возрождения, в котором Волан-де-Морт хотел использовать его кровь. На зов восставшего господина на кладбище явились Пожиратели смерти, которые поклялись ему в своей вечной верности. Чтобы доказать, что события в Годриковой впадине были случайностью, Волан-де-Морт принудил Гарри к дуэли. Во время схватки их палочки неожиданно блокировали друг друга, вызвав тем самым эффект, называемый Приори Инкантатем. Это позволило Гарри еще раз использовать портал и вместе с телом Седрика переместиться обратно в Хогвартс.

В конце концов, выяснилось, что в Хогвартсе действовал шпион Волан-де-Морта Барти Крауч-младший, принявший вид бывшего мракоборца Аластора Грюма, приглашённого преподавать защиту от Тёмных искусств. Именно он бросил имя Гарри в Кубок, он содействовал победе Поттера в турнире, он же превратил Кубок Турнира в портал. Когда обман вскрылся, Министерство магии прислало дементора для казни Барти Крауча-младшего, отказавшись признать то, что Тёмный Лорд вернулся в мир.

Пятый год в Хогвартсе

Гарри чувствует присутствие Волан-де-Морта

Летом Гарри тяжело переживал гибель Седрика Диггори. А тут ещё Долорес Амбридж, помощник министра магии, послала в Литтл Уингинг дементоров, чтобы они напали на Гарри. Гарри пришлось вызвать Патронуса, чтобы спасти себя и Дадли. За применение магии вне школы его вызвали на дисциплинарное слушание в Визенгамот. Но, благодаря помощи Альбуса Дамблдора, Гарри выиграл дело.

Настоящий Аластор Грюм и команда мракоборцев доставили Гарри в штаб-квартиру Ордена Феникса на Площадь Гриммо, 12, расположенную в доме Сириуса Блэка.

Гарри показывает ребятам Заклинание

Корнелиус Фадж назначил Долорес Амбридж преподавателем защиты от Тёмных искусств, чтобы иметь в Хогвартсе своего человека. Позже он сделал её Генеральным инспектором, наделив полномочиями единолично устанавливать школьные порядки. Кроме скучных рассуждений, Амбридж ничего не давала ученикам на своих уроках. Поэтому Гермиона убедила Гарри в необходимости создать «кружок по обучению защите от Тёмных искусств». Так был создан Отряд Дамблдора.

Члены Отряда Дамблдора, слева направо: Рон, Полумна, Невилл, Гермиона, Гарри и Джинни

Волан-де-Морт хотел заполучить «секретное оружие» против Поттера. Этим оружием он считал Пророчество, хранящееся в Министерстве магии. В конце концов, ему удалось заманить туда Гарри. Вместе с членами ОД Роном Уизли, Гермионой Грейнджер, Джинни Уизли, Невиллом Долгопупсом и Полумной Лавгуд, Поттер отправился в министерство, чтобы спасти Сириуса, которого, как Гарри увидел в ложном видении, пытал Волан-де-Морт. Там, в отделе тайн, ребят встретили Пожиратели смерти. Завязалось неравное сражение. К счастью, на помощь юным волшебникам подоспели члены Ордена Феникса. В жаркой схватке на глазах у Гарри погиб Сириус Блэк. Чувствуя, что Пожиратели не справляются с задачей, Лорд Волан-де-Морт самолично явился в Министерство. Так Гарри уже в четвёртый раз столкнулся лицом к лицу со своим заклятым врагом. Но в это время появился Дамблдор, чем спас Гарри: сил пятнадцатилетнего чародея явно не хватило бы на победу над самым могущественным тёмным магом современности. Тёмный Лорд оказался вынужден скрыться, но его успели увидеть прибывшие в Министерство Корнелиус Фадж и многие другие работники. Отрицать возвращение Волан-де-Морта после этого стало невозможно.

Шестой год в Хогвартсе

Гарри Поттер — лучший ученик курса

Слухи о появлении Волан-де-Морта в Министерстве магии и сражении с ним Гарри поползли среди волшебников. Теперь многие стали называть Поттера «Избранным», и новый министр Руфус Скримджер попытался заполучить в свой штат «мальчика для рекламы». Известность уже давно встала Гарри поперёк горла. Он всё ещё не успокоился после смерти Сириуса, и наследование всего имущества крёстного оказалось только лишним напоминанием об утрате.

В Хогвартсе наметились кадровые перестановки. И дело не только в том, что Поттер стал капитаном гриффиндорской команды по квиддичу. Намного важнее то, что Северус Снегг получил долгожданное место профессора Защиты от Тёмных искусств, а освободившееся место преподавателя зельеварения занял Гораций Слизнорт. С этим назначением у Гарри появилась возможность стать мракоборцем: необходимую подготовку по зельеварению к ЖАБА профессор Слизнорт, в отличие от Снегга, был согласен проводить и с учениками, которые набрали на СОВ только «выше ожидаемого». У Гарри, который поставил было крест на зельеварении, не оказалось учебника, и профессор Слизнорт дал ему какой-то старый экземпляр до получения новой книги из «Флориш и Блоттс». Старый учебник принадлежал когда-то некоему «Принцу-полукровке», и предыдущий владелец оставил на полях многочисленные пометки: советы, заклинания, уточнения к рецептам, благодаря которым Гарри стал преуспевать в зельеварении и даже выиграл на первом же занятии флакон с Феликс Фелицис.

Дамблдор начал персонально заниматься с Гарри. Они просматривали воспоминания различных людей, касающиеся детства и юности Волан-де-Морта. Дамблдор подозревал, что, охваченный манией бессмертия, Волан-де-Морт расколол свою душу на несколько (предположительно семь) фрагментов и упрятал их в предметы, которые называются Крестражами. Директор подсказал Гарри, в какие артефакты Тёмный Лорд вложил куски своей души. Два крестража к этому моменту уже были уничтожены: дневник Тома Реддла и кольцо Марволо Мракса. Гарри и Дамблдор отправились вместе на поиски очередного крестража в пещеру у берега моря, где Дамблдор, чтобы добыть крестраж, выпил смертельный напиток.

Когда они вернулись, то застали в Хогвартсе пожирателей смерти. В эту ночь Драко Малфой, недруг Гарри ещё с первого курса, провёл их в замок. Они должны были помочь юноше выполнить волю Волан-де-Морта: убить Альбуса Дамблдора. Однако Драко не хватило воли сделать это, и директора убил Северус Снегг. Перед тем, как покинуть школу вместе с Драко Малфоем, Снегг заявил Гарри, что это он в школьные годы называл себя «Принцем-полукровкой». Гарри подобрал возле тела Дамблдора медальон, взятый в пещере. В выпавшей из медальона записке, подписанной неким «Р.А.Б.» говорилось о том, что истинный крестраж похищен. Выходило так, что смерть Дамблдора была напрасной.

Охота за Крестражами

- Более подробно см. статьи: Гарри Поттер и Дары Смерти, раздел «Сюжет книги», Медальон Слизерина, Чаша Пенелопы Пуффендуй, Диадема Кандиды Когтевран

Гарри разговаривает с Элфиасом

После смерти Альбуса Дамблдора Гарри осознал, что только ему, Рону и Гермионе известна страшная тайна Тёмного Лорда. Лишь они втроём могли найти и уничтожить четыре оставшихся крестража: артефакты, которые делают Волан-де-Морта бессмертным. Гарри знал наверняка, что три из них — это Медальон Слизерина, Чаша Пуффендуй и змея Волан-де-Морта Нагайна. И ещё один предмет, который принадлежал ранее либо Кандиде Когтевран, либо Годрику Гриффиндору… Максимально обезопасив свои семьи от преследования Пожирателями смерти и решив, что учёба в Хогвартсе им только помешает, ребята отправились на поиски.

НЕЖЕЛАТЕЛЬНОЕ ЛИЦО №1 Гарри и Гермиона остро переживают уход Рона Добби спасает Гарри Поттера и его друзей из поместья Малфоев

Вначале они имели одну единственную зацепку — ложный крестраж-медальон с запиской некоего Р.А.Б. Друзьям повезло: они случайно узнали, что автор записки — Регулус Арктурус Блэк, младший брат Сириуса. Пытаясь узнать о давно умершем Регулусе и о настоящем крестраже, ребята расспросили домового эльфа семьи Блэков Кикимера. По его рассказу и с его помощью они вышли на Наземникуса Флетчера, из показаний которого стало ясно, что сейчас искомый Медальон находится у помощницы министра Долорес Амбридж. Гарри, Рон и Гермиона организовали очень рискованную операцию, сумев выкрасть Медальон Слизерина прямо из министерства магии. После этого в поисках возникла большая пауза: ребята не имели ни малейшего понятия, где надо искать другие крестражи, а тот, который они добыли, не могли уничтожить. Эту патовую ситуацию разрешило обретение меча Гриффиндора, к чему (как выяснится много позже) приложил руку ни кто иной, как Северус Снегг. Дальше дело пошло веселей. С помощью Меча Рон разбил Медальон. А когда ребят схватили охотники за головами и привели их в имение Малфоев, именно наличие меча Гриффиндора довело до белого каления Беллатрису Лестрейндж. И Гарри понял — она прятала в своём сейфе в Гринготтсе, вместе с древним Мечом (точнее, его копией, о чём Беллатриса не знала), ещё что-то весьма ценное для её ненаглядного Хозяина. Вырвавшись на свободу, Гарри, Рон и Гермиона, при поддержке гоблина Крюкохвата, организовали налёт на банк волшебников и похитили из сейфа Лестрейнджей Чашу Пуффендуй. Правда, при этом ребята лишились Меча Гриффиндора.

Серая Дама открыла свой секрет только двоим студентам Хогвартса: Тому Реддлу и Гарри Поттеру. Гарри Поттер пытается убить Тёмного Лорда

Из очередного видения Волан-де-Морта Гарри узнал, что следующий крестраж находится в Хогвартсе, куда друзья и устремились. Почувствовав, что и сам Тёмный Лорд собрался прибыть в Хогвартс, Поттер предупредил об опасности деканов факультетов. Сведя воедино рассказы когтевранцев, Серой Дамы и свои собственные наблюдения, Гарри догадался, что крестраж спрятан в Выручай-комнате.

Тем временем Рон и Гермиона спустились в Тайную комнату, где всё ещё лежали останки убитого василиска. Яд его клыков до сих пор сохранял свою смертоносную силу и вполне подходил для уничтожения крестражей. Чашу Гермиона проткнула прямо в Тайной комнате, и несколько клыков они с Роном забрали с собой.

Гарри и Джинни перед финальной битвой Второй магической войны

Диадему Кандиды Когтевран ребята действительно нашли в Выручай-комнате, но туда смогли зайти и Драко Малфой с Гойлом и Крэббом. В ходе сражения между тремя гриффиндорцами и тремя слизеринцами Крэбб вызывал Адское пламя, которое охватило всю Комнату и сожгло не только найденный крестраж, но и самого Крэбба. В последний момент остальные ребята успели вылететь наружу, при этом Гарри взял на свою метлу Драко, а Рон и Гермиона — бесчувственного Гойла.

Гарри сбивает Пожирателя

Тем временем на Хогвартс напали полчища приспешников Волан-де-Морта. Старшекурсники и преподаватели Хогвартса организовали сопротивление. Сам Волан-де-Морт убил Северуса Снегга, полагая, что это сделает его полноправным владельцем Бузинной палочки. Но перед самой смертью Снегг успел отдать Гарри свои воспоминания. Юноша, просмотрев воспоминания Снегга в Омуте памяти, узнал, что является седьмым крестражем, о существовании которого не знал даже сам Тёмный Лорд. Гарри понял, что если он хочет смерти Волан-де-Морта, то должен принять смерть от его руки. Тяжело умирать молодым. Вдвойне тяжелей пойти на эту смерть осознанно. Гарри шёл под мантией-невидимкой, сжав в руке палочку Драко Малфоя, которая вобрала в себя силу Бузинной палочки, и открыв завещанный Дамблдором снитч, в котором оказался Воскрешающий камень. В этот момент Гарри Поттер собрал воедино все три Дара Смерти, но не для того, чтобы стать Повелителем смерти, а для того, чтобы ему хватило душевных сил эту смерть принять. Возможно, ещё и поэтому ему в итоге удалось вернуться в мир живых. Но теперь уже — без куска души Волан-де-Морта внутри.

Тем, что Гарри добровольно принёс себя в жертву, он оградил от смерти всех защитников Хогвартса, подобно тому, как его мать оградила сына от убийцы, пожертвовав собой.

Тем временем Волан-де-Морт, ни капли не сомневающийся в своей окончательной победе, направился со своими приспешниками в Хогвартс, чтобы погасить последние очаги сопротивления. Ослеплённый видом поверженного противника, он не замечал, как ослабли его заклинания, как легко сбрасывали защитники замка его чары… Воспользовавшись суматохой, когда в битву вступили новые силы (на поле перед Хогвартсом появились фестралы с Клювокрылом и кентавры), Гарри (под мантией-невидимкой) вновь вступил в схватку, а Невилл Долгопупс убил Нагайну мечом Гриффиндора, который он вытащил из Распределяющей шляпы. Последний крестраж Волан-де-Морта оказался уничтожен.

В финальном бою с Волан-де-Мортом

Гарри появился в разгар схватки в Большом зале, где Волан-де-Морт и Беллатриса Лестрейндж, едва ли не последние из всего войска Тёмного Лорда, отчаянно сопротивлялись. Когда Молли Уизли убила Беллу, Гарри не дав Волан-де-Морту напасть на миссис Уизли, опустил между ними Щитовые чары и сбросил мантию-невидимку. По рядам защитников Хогвартса пронёсся вздох удивления. Начался самый главный поединок поттерианы: поединок между Томом Реддлом и Гарри Поттером. И когда Волан-де-Морт попытался наложить на Гарри убивающее заклятие, Бузинная палочка не пожелала подчиниться ему и убить своего истинного хозяина (Гарри), заклинание обернулось против самого Волан-де-Морта, и его не стало, на этот раз навсегда.

Законный хозяин и Бузинная палочка воссоединились

В результате всех этих событий Гарри Поттер стал владельцем всех Даров Смерти, из которых он оставил у себя только мантию-невидимку. Воскрешающий камень он выронил где-то в Запретном лесу и не собирался его искать, Бузинную палочку вернул обратно в гробницу Дамблдора.

С уничтожением Волан-де-Морта Гарри потерял способность говорить на змеином языке и понимать его.

Дальнейшая судьба

Гарри, его жена Джинни и их сын Альбус Северус

Идентификационная карта мракоборца Гарри Поттера

О том, как и когда Поттер завершил своё образование и сдал экзамен ЖАБА, в каноне ничего не говорится. По идее, как волшебник, ставший сотрудником Министерства Магии, он обязан был это сделать; с другой стороны, есть свидетельство (статья «Воссоединение Отряда Дамблдора на финале Чемпионата мира по квиддичу»), согласно которому, Гарри (вместе с Роном) поступил на службу в Министерство сразу после Битвы за Хогвартс.

Гарри Поттер стал мужем Джинни Уизли и отцом троих их детей: сыновей Джеймса Сириуса Поттера, Альбуса Северуса Поттера и дочери Лили Полумны Поттер.

В возрасте 27 лет он возглавил отдел мракоборцев. Гарри также добился, чтобы портрет профессора Снегга повесили в директорском кабинете. Каждый год Поттера приглашают в Хогвартс провести несколько лекций по защите от Тёмных искусств.

Гарри продолжил поддерживать тесные дружеские связи с Роном и Гермионой, с которыми он теперь, благодаря Джинни, породнился. Принял очень деятельное участие в судьбе крестника Тедди Люпина, навещал Хагрида и Невилла Долгопупса.

В 2014 году он посетил Чемпионат мира по квиддичу в Аргентине, вместе со своими сыновьями и друзьями. Гарри познакомил детей с Виктором Крамом и болел за Сборную Болгарии, ловцом который являлся его старый знакомый Виктор Крам.

До сих пор остаётся в силе предсказание профессора Трелони о том, что Гарри вовсе не умрёт в юном возрасте, а доживёт до преклонных лет и станет министром магии и отцом двенадцати детей («Гарри Поттер и Орден Феникса»). Первая его часть уже сбылась, но исполнится ли оно целиком, Джоан Роулинг пока не сообщает.

Гарри Поттер и Проклятое дитя

В августе 2020 года Гарри Поттер, глава Отдела магического правопорядка, изъял из дома Теодора Нотта, сына Пожирателя смерти, незарегистрированный маховик времени. Этот прототип позволял путешествовать очень далеко в прошлое и оставаться там до пяти минут. Такое устройство могло стать причиной катастрофических изменений во времени. Поэтому Теодора Нотта арестовывают.

Маховик Нотта спрятали со всеми магическими предосторожностями в кабинете Министра магии Гермионы Грейнджер. Но, несмотря на все эти меры, Альбус Поттер и Скорпиус Малфой украли артефакт, чтобы спасти Седрика Диггори и вернуть сына его отцу, Амосу. Мальчики раз за разом пытались переписать историю, чиня всяческие препятствия Седрику в 1994 году, чтобы он не смог дойти до третьего задания Турнира Трёх Волшебников и остался бы в живых. И раз за разом их старания приводили к «эффекту бабочки», весьма драматическим и даже трагическим образом изменявшему настоящее.

В одном из вариантов прошлого Диггори всё равно погиб, но судьба героев сильно изменилась самым причудливым образом: Рон женат на Падме Патил, Гермиона — противная училка в Хогвартсе. В следующем варианте, когда Седрик остался жив, он стал Пожирателем смерти и в Битве за Хогвартс убил Невилла Долгопупса, а значит, Нагайна не была уничтожена, Тёмный Лорд убил Гарри Поттера и остался у власти. Всё это привело к тому, что Альбус Поттер вообще не родился. Преодолев множество препятствий, герои в итоге возвратили реальность к исходному состоянию.

Однако, позже Дельфи Реддл (дочь Волан-де-Морта и Беллатрисы Лестрейндж) взяла Альбуса и Скорпиуса в плен и перенеслась вместе с ними сначала в 24 июня 1995 года, а потом и в 30 октября 1981 года, чтобы спасти своего отца. Там она уничтожила маховик времени, чтобы не вернуться в настоящее через пять минут.

А в настоящем времени Гарри получил сообщение от Альбуса, которое они со Скорпиусом послали довольно экзотическим способом: записав его на одеяльце маленького Гарри. С помощью усовершенствованного маховика, хранившегося у Люциуса Малфоя, Гарри с Роном, Гермионой, Джинни и Драко Малфоем (беда сплотила бывших недругов) отправились в 1981 год. Совместными усилиями двух поколений Дельфи была побеждена, и вся компания вернулась «назад в будущее».

Магическая сила и навыки

| навык/сила | |

|---|---|

| Способности к защите от Тёмных искусств | У Гарри Поттера особенный талант к защите от Тёмных искусств. |

| Талант к полётам | Врождённая способность подчинять полёт метлы малейшим своим желаниям не только сделала Гарри самым юным ловцом за последние сто лет, но и не раз спасала ему жизнь. |

| Заклинание «Патронус» | Гарри демонстрировал телесного Патронуса (Патронус в виде животного, а не серебристого облачка) уже в возрасте 13 лет. Многие волшебники не умеют этого и в зрелом возрасте. |

| Змеиный язык | Гарри мог разговаривать на змеином языке, способность к которому ассоциируется с тёмными волшебниками, он приобрёл эту способность вместе с осколком души лорда Волан-де-Морта. Гарри утратил этот дар после уничтожения осколка самим Волан-де-Мортом в битве за Хогвартс. |

| Хозяин Даров Смерти | Гарри удалось собрать все три старинных магических артефакта, называемых Дары Смерти, владелец которых мог стать хозяином Смерти. При этом юноша не стремился ими завладеть, а завладев, не стал избегать смерти, но принял её как данность, как неизбежный итог. Возможно, ещё и поэтому Смерть отпустила его обратно в мир живых. |

Имущество

| имущество | |

|---|---|

| Сбережения Поттеров | Когда родители Гарри трагически погибли, он унаследовал вполне достаточные сбережения, хранящиеся в ячейке 687 Гринготтса и благодаря которым Гарри не испытывал нужды во всех необходимых для учёбы в Хогвартсе принадлежностях, книгах, колдовской одежде и в карманных деньгах. |

| Волшебная палочка | Палочка, выбравшая Гарри, сделана из остролиста, дерева, отгоняющего силы зла. Намеренно противоположна палочке из тиса Волан-де-Морта. Сердцевиной обеих палочек послужили перья из хвоста феникса Фоукса. |

| Мантия-невидимка | Очень ценный артефакт, который Гарри получил как подарок на Рождество на первом году обучения в Хогвартсе. Позже он узнал, что мантия раньше принадлежала его отцу, а Альбус Дамблдор всего лишь передал её сыну. Несколько лет спустя Гарри узнал, что именно эта мантия-невидимка является одним из Даров Смерти. |

| Метла Нимбус-2000 | Была подарена Гарри администрацией Хогвартса (или лично профессором Макгонагалл) в сентябре 1991 года, как перспективному ловцу сборной Гриффиндора по квиддичу. Метла сломалась в бурю во время матча Гриффиндор-Пуффендуй в ноябре 1993 года (из-за вмешательства дементоров). |

| Метла Молния | Инкогнито подарена Гарри на Рождество 1993 года Сириусом Блэком. На тот момент — лучшая спортивная метла. Уничтожена во время операции «Семь Поттеров» в июле 1997 года. |

| Коммуникационное («сквозное») зеркало | Одно из двух зеркал, которое подарил Гарри его крёстный Сириус Блэк. При помощи одного зеркала можно переговариваться с обладателем другого. Даже посредством разбитого зеркала, Гарри удалось связаться с Аберфортом Дамблдором, когда он с друзьями был схвачен и заперт в особняке Малфоев. |

| Букля | Сова Гарри, которая составляла ему компанию и была жизненно необходима, чтобы доставлять сообщения для Гарри или от него, особенно в укрытие Сириуса. Букля была поражена убивающим заклятием при операции «Семь Поттеров». Её смерть была для Гарри тяжёлой утратой. |

| После смерти Сириуса Гарри унаследовал всё, что когда-то принадлежало его крёстному: | |

| Резиденция семьи Блэков | Расположенный на площади Гриммо, 12 дом и всё имущество, что находится внутри, включая Кикимера (фамильного домашнего эльфа). (Правда, достаточно много оттуда утащил Наземникус Флетчер, включая медальон Слизерина.) |

| Сбережения Блэков | Гарри унаследовал состояние Сириуса в ячейке Гринготтса. |

| Гарри Джеймс Поттер | |

|---|---|

| Информация о крестраже | |

| Тип |

защитное средство |

| Создатель |

Волан-де-Морт |

| Предназначение |

делать бессмертным |

| Характеристики |

человек |

| Уничтожитель |

Волан-де-Морт |

| Жертва для создания |

Лили Поттер |

| Обладатели |

Вещи, которые не совсем принадлежали Гарри:

- Карта Мародёров — подарена Поттеру близнецами Уизли, но сами близнецы стащили её из кабинета Филча, который, в свою очередь отобрал её у кого-то из Мародёров.

- Учебник Принца-полукровки — был взят изначально Гарри во временное пользование в кабинете Зельеварения, до того момента, как из магазина должен был придти заказанный новый учебник зельеварения Либациуса Бораго. Однако вместо старого учебника Гарри положил обратно в шкаф новенький экземпляр.

Палочка с пером феникса

Гарри и его палочка

Волшебная палочка Гарри Поттера длиной 28 сантиметров (11 дюймов) сделана из остролиста, с сердцевиной из пера феникса, её сделал мастер Олливандер. Палочка Поттера необычна: у неё есть палочка-близнец, сердцевина которой тоже содержит перо из хвоста того же феникса. Только вторая палочка сделана из тиса. Эта тисовая палочка выбрала своим хозяином Тома Марволо Реддла намного раньше, чем палочка из остролиста выбрала Поттера. То, что палочки-близнецы выбрали хозяевами двух непримиримых врагов, сыграло большую роль в их дальнейшей судьбе.

Семья

Кровные родственники:

Со стороны отца:

- Джеймс Поттер — отец.

- Флимонт Поттер — дед.

- Юфимия Поттер — бабушка.

- Игнотус Певерелл — предок.

- Мистер Певерелл — предок.

- Линфред Стинчкомбский — предок.

- Хардвин Поттер — предок.

- Генри Поттер — прадед.

- Карлус Поттер — неизвестно.

- Дорея Блэк (в замужестве Поттер) — неизвестно.

Со стороны матери:

- Лили Эванс (в замужестве Поттер) — мать.

- Петуния Эванс (в замужестве Дурсль) — тётя.

- Вернон Дурсль — дядя (муж Петунии).

- Дадли Дурсль — двоюродный брат (сын Петунии).

- Мистер Эванс — дед.

- Миссис Эванс — бабушка.

Собственные дети:

- Джеймс Сириус Поттер — сын.

- Альбус Северус Поттер — сын.

- Лили Полумна Поттер — дочь.

Некровные родственники:

Родственники со стороны жены:

- Джинни Уизли (в замужестве Поттер) — жена.

- Артур Уизли — тесть.

- Молли Уизли (урождённая Пруэтт) — тёща.

- Фабиан и Гидеон Пруэтт — братья Молли. На момент знакомства Гарри с семьёй Уизли были уже мертвы.

- Билл Уизли — шурин.

- Флёр Делакур — невестка/сноха (жена Билла).

- Мари-Виктуар Уизли — племянница.

- Доминик Уизли — племянница.

- Луи Уизли — племянник.

- Чарли Уизли — шурин.

- Перси Уизли — шурин.

- Одри Уизли — невестка/сноха (жена Перси).

- Люси Уизли — племянница.

- Молли Уизли (младшая) — племянница.

- Фред Уизли — шурин. На момент женитьбы Гарри на Джинни Уизли был уже мёртв.

- Джордж Уизли — шурин.

- Анджелина Джонсон — невестка/сноха (жена Джорджа).

- Фред Уизли (младший) — племянник.

- Роксана Уизли — племянница.

- Рон Уизли — шурин.

- Гермиона Грейнджер — невестка/сноха (жена Рона).

- Роза Грейнджер-Уизли — племянница.

- Хьюго Грейнджер-Уизли — племянник.

Духовные родственники:

- Сириус Блэк — крёстный отец.

- Тедди Люпин — крестник.

Многие персонажи Поттерианы приходятся некровными родственниками Гарри Поттеру. Так, к примеру, главный враг Гарри, Волан-де-Морт, имеет очень дальнее родство с ним через братьев Певереллов: Гарри является потомком Игнотуса, а Том Реддл, судя по всему, потомком Кадма.

Взаимоотношения

Родители

Танец родителей Гарри Поттера

Сам Гарри едва знал своих родителей (они умерли, когда малышу был всего лишь год с небольшим), но относился к ним с глубоким почтением и любовью. Каждый раз, когда кто-то говорил, что он похож на отца, Гарри испытывал прилив гордости. И любой, кто отзывался о родителях нелестно, возбуждал к себе ненависть мальчика. Естественно, что злобные отзывы профессора Снегга о Джеймсе не добавили теплоты в их отношения. Чувства к отцу поколебались, когда Гарри увидел в Омуте памяти беспричинное нападение Джеймса и Сириуса на безоружного Снегга. Он не перестал после этого любить отца, просто его отношение к нему утратило детскую восторженность.

Несколько раз Гарри предоставилась возможность увидеть своих родителей: на магических фотографиях (в альбоме, который собрал для него Рубеус Хагрид), в зеркале Еиналеж[7], во время действия Приори Инкантатем у могилы отца Тома Реддла[5], во время действия Воскрешающего камня[6].

Дадли

Дадли в окружении родителей

В детстве Дадли регулярно пытался побить Гарри. По многим причинам. Потому, что Гарри был слабее, потому, что Дадли прощалось всё, потому, что Гарри был совершенно не похож на Дадли, потому, что Дадли так пытался самоутвердиться… Продолжать? Но после того как Дадли узнал, что кузен у него волшебник, он стал относиться к нему с опаской. По крайней мере, задираться к нему Дадли перестал. Но вот, когда мальчишкам было по пятнадцать лет, Гарри спас Дадли от дементоров, несмотря на все их предыдущие отношения. Маглы не могут видеть дементоров, они только чувствуют их присутствие. И Дадли понадобилось два года, чтобы в полной мере осознать происшедшее. При расставании с двоюродным братом перед операцией «Семь Поттеров»,[6] Дадли первый «зарывает топор войны». На прощание они пожимают друг другу руки.

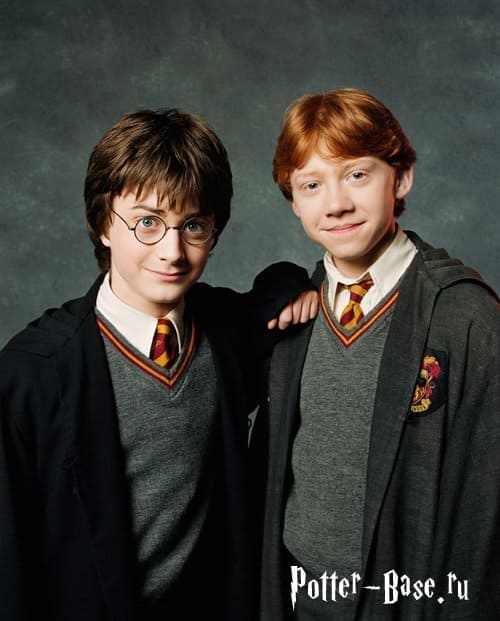

Рон Уизли

Рон и Гарри в Хогвартсе

Рон Уизли стал лучшим другом Гарри на первом же году обучения в Хогвартсе. Неконфликтный открытый Рон очень понравился Гарри, а знаменитый Гарри Поттер оказался обычным мальчишкой, что, в свою очередь, очень подходило Рону. Они всегда были словно братья, хотя, как и у всех нормальных людей, у них не обходилось без ссор. Их дружба подверглась испытанию в 1994 году[5], когда Гарри избрали Чемпионом на Турнире Трёх Волшебников. Ещё один раз они поссорились, когда на Рона нагнал депрессию Медальон Слизерина[6]. Тем не менее, все разногласия были разрешены, и ребята остались друзьями на всю жизнь.

Гермиона Грейнджер

На Четвертом курсе

Гермиона Грейнджер подружилась с Гарри и Роном, после того как они все вместе встретились лицом к лицу с горным троллем в 1991 году.[7]. С тех пор Гермиона, благодаря своим знаниям, нередко выпутывала неуёмную троицу друзей из неприятностей, в которые они все регулярно попадали.

Грейнджер завязала очень крепкую дружбу с Гарри и Роном, она всецело доверяла Гарри, как и он ей. Девушка была честна и душевна с ним, никогда не лгала Поттеру (кроме единственного раза, когда пыталась убедить не только его, но и саму себя в том, что ей плевать, с кем Рон целуется и проводит время), всегда помогала и поддерживала его. Гарри тоже поддерживал Гермиону, когда она была в ссоре с Роном или злилась на него, да и просто в трудные периоды. Во время поиска крестражей, когда Рон ушёл, Гарри всячески пытался поднять своей знакомой настроение.

Гермиона очень привязалась к Гарри за годы учёбы в Хогвартсе. Она не хотела терять Гарри, что проявилось во время Битвы за Хогвартс, когда Гарри отправился к Волан-де-Морту.

Несмотря на попытки разных людей приписать мистеру Поттеру и мисс Грейнджер романтические отношения (Рита Скитер, Чжоу Чанг и даже Рон Уизли), Гермиона никогда не затрагивала сердца Гарри. Она для него — друг и сестра[6] (если хотите, «названая сестра»), чувства между ними достаточно глубокие, но к влюблённости не имеющие ни малейшего отношения.

Альбус Дамблдор

Альбус Дамблдор

Отношения с Альбусом Дамблдором сначала напоминают отношения «Всё понимающий Учитель — несмышлёный Ученик». Совершенно незаметно они перетекают в «Великий полководец — верный Солдат». И хотя бывали случаи, когда Гарри не на шутку сердился на Дамблдора, так что был готов разнести всё вокруг[6][7], в конце концов, он принял старого учителя таким, каков он есть: зная о его недостатках, но высоко ценя его достоинства.

Северус Снегг

Профессор Снегг

В том, что отношения с профессором Снеггом не сложились с самого начала, виноват всецело Снегг и его давнишняя ненависть к Джеймсу Поттеру, на которого Гарри так похож внешне. Однако довольно быстро мальчик начал платить Мастеру Зелий той же монетой. И даже переплачивать. Он не замечал, что Снегг, как бы язвительно он ни отзывался о Поттере, никогда не делал ему действительного зла, а иногда даже спасал его. Лишь посмотрев воспоминания Снегга, которые тот успел отдать Гарри перед смертью во время Битвы за Хогвартс[6], юноша изменил своё отношение к этому человеку настолько, что своему младшему сыну дал второе имя в честь Северуса Снегга.

Сириус Блэк

Сириус

Сириус Блэк после появления в жизни Гарри был для мальчика, словно отец или старший брат, которому можно полностью довериться и спросить что угодно, не боясь показаться глупым. Для Сириуса же Гарри — будто оживший Джеймс. Он, как и Снегг, оказался введён в заблуждение внешним сходством отца и сына Поттеров. Только реакция у него на это сходство была другой. Во время беспредела Долорес Амбридж крёстный укрепил Гарри в решении организовать практические занятия по защите от Тёмных искусств, и добавил, что Джеймс сделал бы то же самое.

Когда Сириус был убит в Отделе тайн, Гарри всё никак не мог поверить в то, что они больше никогда не встретятся. Ему так отчаянно не хватало крёстного, что он пытался всеми способами наладить с ним связь. Сперва Гарри надеялся, что Сириус появится в сквозном зеркале, потом — что Сириус мог бы стать привидением… Но, в конце концов, Гарри пришлось смириться с тем, что Сириус ушёл и уже никогда не вернётся. В последний раз они с крёстным, вернее с его воспоминанием, встретились во время Битвы за Хогвартс, когда Сириус вместе с родителями Гарри и Люпином появился из воскрешающего камня.

Римус Люпин

Гарри и Римус на свадьбе Билла и Флер

Римус Люпин всегда со всеми предельно честен. И достаточно принципиален. Он сразу же завоевал уважение не только Гарри, но и его друзей. Однако именно его принципиальность, и ещё то, что первое знакомство состоялось тогда, когда Люпин был учителем Гарри, поставило между ними некоторую дистанцию в отношениях. И если был выбор, к кому обратиться за советом: к Блэку или к Люпину, Гарри выбирал поначалу Сириуса. В дальнейшем, поскольку Люпин и не думал отстраняться от Гарри, они сблизились. Настолько, что в один момент поменялись местами. Когда Римус поступил неправильно, бросив (как он думал, для её же блага) свою беременную жену, Гарри всего несколькими словами показал бывшему учителю всю его неправоту. Позже Люпин был благодарен Гарри за вовремя сделанное внушение. Недаром крёстным отцом своего новорождённого сына он попросил стать именно Поттера.

Рубеус Хагрид

Хагрид

Рубеус Хагрид — первый друг Гарри из волшебного мира и вообще первый друг. Можно сказать, что Хагрид дважды спас Гарри: один раз — когда вынес малыша Гарри из развалин дома; второй — когда забрал его от Дурслей и вернул в волшебный мир. Гарри всегда относился к Хагриду с особой теплотой, не допускал каких-либо нападок на него со стороны других учеников, и вообще был готов намылить шею тем, кто имел неосторожность как-то нелестно отозваться о полувеликане.

Со временем, (где-то уже с третьего курса) Гарри начал относиться к Хагриду не как к взрослому самостоятельному человеку, а как к такому взрослому, которого следует постоянно опекать, чтоб он не вляпался опять в неприятности. Мальчик не замечал, что при всей своей кажущейся наивности, Хагрид не так-то прост… По крайней мере, в истории с философским камнем Рубеус уж очень вовремя проговорился, наведя трёх друзей на нужные мысли и догадки. Вот чего у Хагрида никак не отнимешь: он действительно горячо любит Гарри Поттера. Хагрид вынес Гарри из Запретного леса, когда тот притворялся мёртвым, во время битвы за Хогвартс. И мальчику было крайне жаль, что он не мог хоть словом, хоть жестом намекнуть, что жив, и тем утешить полувеликана.

Чжоу Чанг

Гарри обратил внимание на Чжоу Чанг в 1994 году: она великолепно играла в квиддич за команду Когтеврана и была очень привлекательна. Примерно полгода спустя он долго не решался пригласить её на Святочный бал[5], а когда всё-таки набрался смелости, оказалось, что Чжоу уже приглашена Седриком Диггори.

На пятом году учёбы в Хогвартсе они начали встречаться, именно Чжоу подарила Гарри его первый поцелуй. Однако завязавшиеся было романтические отношения долго не продлились. Чжоу всё время возвращалась мыслями к погибшему Седрику и ревновала Гарри к Гермионе, что не добавляло молодым людям душевной близости. Предательство Отряда Дамблдора подружкой Чжоу Мариэттой и отказ девушки порвать отношения с предательницей поставили точку в романе Чанг и Поттера.

Накануне битвы за Хогвартс Чжоу снова появилась в повествовании, и стало понятно, что девушка не прочь «начать сначала». Вот только мысли Гарри в это время были заняты другим… или, точнее, другой.

Джинни Уизли

Джинни Уизли и Гарри впервые встретились на платформе 9¾ в 1991 году, когда маленькая девочка, провожавшая старших братьев в Хогвартс, была весьма заинтригована появлением «мальчика, который выжил». Когда же она впервые пошла в Хогвартс, всякий раз, встречая Гарри, Джинни робела и смущалась, не решаясь с ним заговорить. Даже то, что Гарри вызволил её из Тайной комнаты, не добавило девочке смелости. Гарри тоже не слишком обращал внимание на младшую сестричку Рона. Тем более что его мыслями всё более овладевала Чжоу Чанг. Джинни сдружилась с Гермионой, а позже — и с Полумной Лавгуд. Постепенно девочка стала самодостаточной личностью, научившейся в первую очередь уважать саму себя. Незаметно для всех Джинни превратилась в одну из самых популярных девушек Хогвартса. Это она выбирала, с кем ей встречаться, а кого бросить. При этом она искренне пыталась быть другом для Гарри Поттера. Другом, и никем более: она не навязывалась. Она не делала «маленьких женских гадостей» Чжоу, когда та встречалась с Гарри, и не злорадствовала, когда Гарри с ней порвал. Она была выше этого. И полагала, что у Гарри своя голова на плечах, а манипулировать любимым человеком было не в её характере. Постепенно Гарри начал проявлять интерес к Джинни, и весной 1997 года, на праздновании выигрыша Гриффиндором школьного кубка по квиддичу, вдруг, неожиданно даже для самого себя, поцеловал её на глазах всего факультета.[8] Но счастливый период свиданий с Джинни быстро был прерван самим Гарри: он побоялся, что своими чувствами сделает любимую девушку мишенью для Волан-де-Морта. Лишь после падения Тёмного Лорда ничто больше не мешало счастью влюблённых. Джинни стала женой Гарри Поттера и матерью их троих детей.

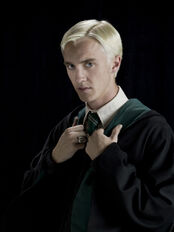

Драко Малфой

Драко Малфой

Драко Малфой познакомился с Гарри в магазине мадам Малкин в Косом Переулке[7]. При этом именно Драко раз за разом пытался разговорить стоящего рядом черноволосого мальчика. Чем-то Гарри ему очень понравился, и юный Малфой стремился произвести на нового знакомца как можно лучшее впечатление. Лучшее, в понимании Драко. Но вся его «крутизна» настраивала Гарри против него. Драко пренебрежительно отозвался о маглах, а Гарри вырос среди них и втайне побаивался, что окажется никудышным магом. Драко хвастался, как носились с ним его родители («отец выбирает мне сейчас метлу, а мать смотрит волшебные палочки»), а Гарри всё это ярко напомнило кузена Дадли. И в довершении всего, Драко презрительно отозвался о Хагриде, единственном друге Гарри, чем окончательно настроил Поттера против себя. Все дальнейшие отношения между мальчиками сводились к тому, что Драко постоянно придирался к Гарри. Именно упорное нежелание Поттера обратить внимание на такую «выдающуюся личность», как Малфой, толкало последнего на постоянные насмешки и оскорбления в адрес человека, с которым на самом деле Драко всегда хотел… дружить! Увы, Малфой был не в состоянии подавить свою спесь, а у Гарри хватало своих забот, чтобы разбираться ещё и в подтекстах поступков Драко. Некий перелом в их отношениях наступил лишь весной 1998 года. Во-первых, юный Малфой всячески пытался «не опознать» бывших сокурсников, когда они попали в лапы тётушки Беллатрисы, во-вторых, Гарри спас Драко во время пожара в Выручай-комнате и позже, когда на него, безоружного, напали Пожиратели смерти. Однако, хотя вражда и прекратилась, дружба между Драко и Гарри уже не возникла, да и не могла возникнуть: слишком много старых обид стояло между ними. И через 19 лет, случайно встретившись на платформе 9¾, Драко всего лишь слегка кивнул Гарри.

Добби

Добби

С самого начала знакомства с Добби Гарри узнаёт, что домашние эльфы — бесправные рабы в волшебных семьях. Действия домовика навели Поттера на мысль, что тот желает ему если не зла, то больших неприятностей — точно. Пытаясь узнать причину, по которой Добби, искренне восхищающийся Гарри Поттером, раз за разом устраивал ему неприятности, мальчик выяснил, что домовик пытался его таким образом… спасти. Мало того, Добби не мог выдать хозяйскую тайну, но дал понять Поттеру, что над Хогвартсом нависла смертельная опасность. Поттер поначалу испытывал злость к домовику, которую сменила жалость, когда мальчик узнал истинные мотивы поступков Добби. Видя, как эльф жаждет свободы, Гарри обманным путём заставил Люциуса Малфоя, хозяина Добби, освободить беднягу. С тех пор Добби не просто боготворил Гарри, но и стал ему преданным другом, по мере сил стараясь ему помогать.

Последней (и поистине неоценимой) услугой стало спасение Гарри, Рона, Гермионы, мистера Олливандера, Полумны Лавгуд, Дина Томаса и гоблина Крюкохвата из плена в поместье Малфоев. Этот поступок закончился для Добби трагично: он погиб от кинжала Беллатрисы Лестрейндж, который та бросила в эльфа в последний момент. Гарри был настолько потрясён гибелью Добби, что выкопал ему могилу вручную, без волшебства, с одной стороны, тяжёлым физическим трудом заглушая боль утраты, с другой — отдавая дань уважения самоотверженному и честному эльфу.

Семья Уизли

Отношение Гарри к членам этой семьи складывалось постепенно. Правда, не все Уизли, с которыми он сталкивался, относились к нему одинаково. Например, третий сын, Перси, менял своё мнение о Гарри вместе с переменой мнения своего босса. Но остальные Уизли для мальчика значили гораздо больше, чем, например, члены семьи Дурслей. А Молли вообще говорила, что относится к Гарри как к собственному сыну, и её боггарт — последовательные смерти всех членов семьи, включая Гарри.

Имена

В течение всего романа Гарри называли не только Гарри, но и другими именами. А именно (в хронологическом порядке):

- Мальчик-Который-Выжил — так назвало Гарри волшебное сообщество после ночи 31 октября 1981 года, когда мальчик оказался единственным, кто выжил из семьи Поттеров (и из всех жертв нападений Волан-де-Морта вообще).

- Кровавый Барон — Гарри выдал себя за него Пивзу, спрятавшись под мантией невидимкой на первом курсе.

- Грегори Гойл — Гарри откликался на это имя, пока был под действием оборотного зелья на втором курсе, изображая при этом Гойла.

- Невилл Долгопупс — Гарри выдал себя за него, чтобы не привлекать внимание в автобусе «Ночной рыцарь».

- Перкинс — так его назвал не различающий своих бывших и нынешних учеников Катберт Бинс.

- Потти — уничижительное имя, данное Поттеру Драко Малфоем и подхваченное Пивзом.

- Поттер-Обормоттер — Пивз.

- Маленький мальчик, пти гарсон — Флёр Делакур.

- Поттер-Смердоттер — последователи Седрика Диггори.

- Мальчик-Который-Лжёт — «Ежедневный пророк» в год травли Гарри и Дамблдора.

- Избранный — с лёгкой руки журналистов «Ежедневного Пророка» так стали называть Гарри после битвы в Отделе Тайн.

- ‘Арри — с акцентом называет его так Флёр Делакур (а заодно и пародирующая её Джинни Уизли).

- Парри Гроттер — выпивший Гораций Слизнорт.

- Рундил Уозлик — Гарри выдавал за своё прозвище перед Снеггом.

- Барни Уизли — это имя Гарри носил, пока был под действием Оборотного зелья на свадьбе Билла и Флёр.

- Барри Уизли — не расслышавшая имя «Барни» тётушка Мюриэль.

- Альберт Ранкорн — под действием Оборотного зелья Гарри приобрёл внешность этого человека во время вылазки в Министерство осенью 1997 года.

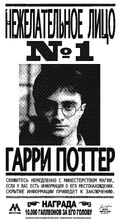

- Нежелательное лицо № 1 — эвфемизм, который использовался в официальных источниках после прихода к власти Волан-де-Морта, чтобы лишний раз не называть знаменитого Гарри Поттера по имени.

- Вернон Дадли — Гарри назвался вымышленным именем, взяв имена дяди и кузена, когда был схвачен егерями.

Этимология

Свою фамилию Поттер получил, благодаря другу детства Джоан Роулинг — Яну Поттеру.

Potter в английском языке имеет много значений, но примечательными из них являются:

- горшечник — на протяжении всех книг миссис Фигг является тайным хранителем Гарри.[9]

- работать кое-как, бездельничать — это явная ирония Роулинг.[10]

- лодырничать, слоняться — этим Гарри занимался, по мнению Дурслей и соседей, в пятой книге[11][12].

- фланирование — одно из значений: разгадка тайн, исследование городских легенд.

За кулисами

Билл Гейтс в роли Гарри Поттера

- Роль Гарри в фильмах исполнял Дэниел Рэдклифф, он его играл целых десять лет.

- У Гарри зелёные глаза, а у Рэдклиффа голубые.

- У Гарри чёрный цвет волос, тогда как у Дэниела каштановые.

- Гарри описывался как очень худой мальчик во всех книгах, при этом у Дэниела атлетическая фигура.

- Гарри был волшебником месяца на сайте Джоан Роулинг в октябре 2007 года[13].

- В первой книге упоминается 11-ый день рождения Гарри 31 июля во вторник. Но на самом деле эта дата приходилась на среду.

- На кладбище недалеко от Тель-Авива находится могила девятнадцатилетнего рядового Королевского полка Великобритании Гарри Поттера — полного тёзки литературного персонажа. Благодаря творчеству Джоан Роулинг, могила стала привлекать множество туристов. Могила Гарри Поттера добавлена в официальный список достопримечательностей[14].

- В 2002 году на открытии выставки Consumer Electronics Show, во время выступления Билла Гейтса, был показан видеоролик, в котором глава корпорации Microsoft предстал в роли Гарри Поттера[15]

- Во Флориде живёт полный тёзка Гарри Поттера[16].

- Начиная со второго фильма, Гарри Поттер в русском дубляже говорит голосом Николая Быстрова, который первоначально озвучивал Драко Малфоя[17].

- За время съемок Дэниел Рэдклифф сменил около 70 волшебных палочек и 160 пар очков. Неудивительно, ведь он предпочитал выполнять некоторые трюки, например, полёты на мётлах, самостоятельно[18].

Галерея

Заговор троицы против Малфоя

Перед отъездом из Хогвартса

Гарри и Рон летят в Хогвартс

Первый полёт Гарри на Клювокрыле

Гарри и Гермиона Грейнджер

Кингсли показывает Гарри информацию

Гарри и Найджел слышат приближение Амбридж и инспекционной дружины

Гарри и Гермиона на кладбище в Годриковой впадине

Гарри во время Битвы за Хогвартс

Гарри во время Битвы за Хогвартс

Гарри после Битвы за Хогвартс

ЛЕГО Гарри с Буклей

Смотрите также

- Дни рождения Гарри Поттера

- Подарки Гарри Поттера

- Палочка Гарри Поттера

Примечания

- ↑ 1,0 1,1 1,2 Статья «Семья Поттеров» на Pottermore.

- ↑ Гарри Поттер и Проклятое дитя (пьеса).

- ↑ «Гарри Поттер и Дары Смерти: Часть 2»

- ↑ Возможно из-за фигуры взмаха палочки при «Авада Кедавра»

- ↑ 5,0 5,1 5,2 5,3 «Гарри Поттер и Кубок Огня»

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 6,3 6,4 6,5 6,6 6,7 «Гарри Поттер и Дары Смерти»

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 7,2 7,3 «Гарри Поттер и Философский камень»

- ↑ «Гарри Поттер и Принц-полукровка»

- ↑ слово «Figulus» означает «гончар», т.е. то же, что и «Potter».

- ↑ «Гарри взял губку, вымыл окно, машину, потом постриг газон, унавозил клумбы, обрезал и полил розовые кусты».«Гарри Поттер и Тайная комната» — Глава 1. День рождения — хуже некуда

- ↑ «Гарри Поттер и узник Азкабана» — Глава 2. Большая ошибка тётушки Мардж

- ↑ «Гарри Поттер и Орден Феникса» — Глава 1. Дадли досталось

- ↑ Wizard of the Month Archive jkrowling.com

- ↑ Найдена могила Гарри Поттера Дни.Ру

- ↑ .Билл Гейтс снялся в роли Гарри Поттера Компьюлента

- ↑ Назван настоящий возраст Гарри Поттера Дни.ру

- ↑ Чьим голосом говорит Гарри Поттер по-русски kp.ru

- ↑ Волшебник на миллион Коммерсант.ru

Ссылки

|

п•о•р Карьера Гарри Поттера |

||

|---|---|---|

| Предшественник | Должность | ㅤПреемникㅤㅤ |

| Анджелина Джонсон | Капитан сборной факультета Гриффиндора по квиддичу 1996 — 1997 |

Неизвестен |

| Неизвестен | Глава мракоборческого центра с 2007 |

Неизвестен |

|

п•о•р Турнир Трёх Волшебников · 1994 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Коллегия судей | Альбус Дамблдор · Барти Крауч · Игорь Каркаров · Корнелиус Фадж · Людовик Бэгмен · Олимпия Максим |  |

| Школы | Дурмстранг · Хогвартс · Шармбатон | |

| Чемпионы | Виктор Крам · Гарри Поттер · Седрик Диггори · Флёр Делакур | |

| Турнир | Первый этап · Второй этап · Третий этап | |

| Существа | Акромантул · Боггарт · Василиск · Гриндилоу · Дементор · Драконы · Русалки и тритоны · Сфинкс | |

| Пленники второго этапа | Габриэль Делакур · Гермиона Грейнджер · Рон Уизли · Чжоу Чанг | |

| Объекты | Золотое яйцо · Кубок Огня · Кубок Турнира |

|

п•о•р Отряд Дамблдора |

|

|---|---|

| Основатели | Гарри Поттер · Гермиона Грейнджер · Рон Уизли |

| Лидеры | Гарри Поттер · Полумна Лавгуд · Невилл Долгопупс · Джинни Уизли |

| Участники |

|

| Сочувствовавшие и помогавшие |

|

|

п•о•р Британское Министерство магии |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Министры магии | |||

|

|||

| Работники Министерства магии Орфорд Амбридж · Долорес Амбридж · Миллисента Багнолд · Боб · Бродерик Боуд · Амелия Боунс · Кингсли Бруствер · Альберт Бут · Людовик Бэгмен · Бэзил · Ваканда · Улик Гамп · Гесфестус Гор · Гермиона Грейнджер · Аластор Грюм · Отталин Гэмбл · Уилки Двукрест · Юджина Дженкинс · Берта Джоркинс · Амос Диггори · Элдрич Диггори · Алиса Долгопупс · Фрэнк Долгопупс · Джон Долиш · Присцилла Дюпон · Максимилиан Крауди · Барти Крауч · Дирк Крессвелл · Венузия Крикерли · Сол Крокер · Реджинальд Кроткотт · Артемизия Лафкин · Радольфус Лестрейндж · Нобби Лич · Лайелл Люпин · Минерва Макгонагалл · Тиверий Маклагген · Лоркан МакЛайрд · Уолден Макнейр · Хамиш МакФерлeн · Дугалд Макфэйл · Септимус Малфой · Эрик Манч · Гризельда Марчбэнкс · Гортензия Миллифут · Мирафора Мина · Элоиз Минтамбл · Гарольд Минчум · Арнольд Миргуд · Катберт Мокридж · Левина Монкстэнли · Орабелла Наттли · Портеус Натчбулл · Боб Огден · Тиберий Огден · Уильям Олдертон · Эванджелина Орпингтон · Анктуоус Осберт · Персей Паркинсон · Перкинс · Джастус Пилливикл · Гарри Поттер · Праудфут · Альберт Ранкорн · Гавейн Робардс · Дамокл Роули · Август Руквуд · Мнемона Рэдфорд · Ньют Саламандер · Руфус Скримджер · Леонард Спенсер-Мун · Фэрис Спэвин · Гроган Стамп · Сэвидж · Вильгельмина Тафт · Игнатий Тафт · Пий Толстоватый · Нимфадора Тонкс · Демпстер Уигглсвэйд · Артур Уизли · Перси Уизли · Уильямсон · Мистер Уорлок · Элфинстоун Урхарт · Руфус Фадж · Корнелиус Фадж · Джозефина Флинт · Бэзил Флэк · Гектор Фоули · Муфалда Хмелкирк · Миссис Чанг · Арчер Эвермонд · Миссис Эджком · Корбан Яксли |

|||

| Структура Бюро по связям с кентаврами · Отдел выявления и конфискации поддельных защитных заклинаний и оберегов · Отдел магических игр и спорта · Отдел магических происшествий и катастроф · Отдел магического правопорядка · Отдел магического транспорта · Отдел магического хозяйства · Отдел международного магического сотрудничества · Сектор борьбы с незаконным использованием изобретений маглов · Отдел регулирования магических популяций и контроля над ними · Министр магии и обслуживающий персонал · Сектор борьбы с неправомерным использованием магии · Отдел тайн · Комиссия по учёту магловских выродков |

|||

| См. также: | Визенгамот · Международная конфедерация магов · Охрана Министерства магии · Волшебный патруль · Совет магического законодательства |

|

п•о•р Волшебник месяца |

|

|---|---|

| 2004 год | Феликс Саммерби · Гвеног Джонс · Донаган Тремлетт · Онория Наткомб · Урик Странный · Гленда Читток · Девлин Вайтхорн · Игнатия Уилдсмит |

| 2005 год | Дервент Шимплинг · Артемизия Лафкин · Мунго Бонам · Гондолина Олифант · Феликс Саммерби · Эльфрида Клагг · Чонси Олдридж · Бриджит Венлок · Гаспард Шинглтон · Фифи ЛаФолл · Шарлотта Пинкстоун · Боумен Райт |

| 2006 год | Джокунда Сайкс · Ярдли Платт · Дэйзи Доддеридж · Гроган Стамп · Фабиус Уоткинс · Дэйзи Хукам · Тарквин МакТавиш · Эрика Стейнрайт · Хамблдон Квинс · Идрис Оукби · Лоркан д`Эат · Лауренция Флетвок |

| 2007 год | Харви Риджбит · Мнемона Рэдфорд · Тилден Тутс · Магента Комсток · Пенелопа Пуффендуй · Салазар Слизерин · Годрик Гриффиндор · Кандида Когтевран · Альбус Дамблдор · Гарри Поттер |

|

п•о•р Карточки из шоколадных лягушек |

||

|---|---|---|

| Золотые | Аг Ненадежный · Бес малый · Бладвин Блад · Большая пурпурная жаба · Берти Ботт · Бран Кровожадный · Валлийский зелёный дракон · Венгерский хвосторог · Веретенница · Этельред Вспыльчивый · Гебридский чёрный дракон · Герпий Злостный · Гигантский кальмар · Гитраш · Глизень · Голиаф · Горный тролль · Гермиона Грейнджер · Гырг Грязный · Малодора Гримм · Годрик Гриффиндор · Альбус Дамблдор · Двупалый тритон · Дзю Йен · Армандо Диппет · Докси · Граф Влад Дракула · Единорог · Кельпи · Кандида Когтевран · Амарильо Лестат · Лукотрус · Мантикора · Корделия Мизерикордия · Моргольт · Монтегю Найтли · Норвежский горбатый дракон · Олгаф Отвратительный · Парацельс · Шарлотта Пинкстоун · Гарри Поттер · Пенелопа Пуффендуй · Румынский длиннорог · Леди Кармилла Сангвина · Руфус Скримджер · Летиция Сомноленс · Эдгар Струглер · Тролль · Сэр Герберт Уорней · Эаргит Безобразный · Фалько Эсалон · Феникс · Мамаша Хаббард · Циклоп · Энгист из Верхнего Барнтона · Баба-Яга |  |

| Серебрянные | Андрос Неуязвимый · Освальд Бимиш · Венделина Странная · Альберик Граннион · Григорий Льстивый · Гвеног Джонс · Дэйзи Доддеридж · Керли Дюк · Киприан Йодль · Клиодна · Эльфрида Клегг · Королева Маб · Криспин Кронк · Гидеон Крумб · Артемизия Лафкин · Лаверна де Монморанси · Мопсус · Дунбар Оглторп · Чонси Олдридж · Гондолина Олифант · Мирабелла Планкетт · Боумен Райт · Ксавье Растрик · Феликс Саммерби · Леопольдина Смезвик · Бленхейм Сток · Сахарисса Тагвуд · Донаган Тремлетт · Альберта Тутхилл · Игнатия Уилдсмит · Джоселинд Уэдкок · Семь сыновей Фаддеуса Феркла · Фаддеус Феркл · Фулберт Пугливый · Димфна Фурмаг · Моргана ле Фэй · Цирцея · Гленда Читток · Дервент Шимплинг · Гаспард Шинглтон | |

| Бронзовые | Корнелиус Агриппа · Арчибальд Алдертон · Хиткот Барбари · Мусидора Барквиз · Флавиус Белби · Балфур Блейн · Беатрис Блоксам · Мунго Бонам · Кассандра Ваблатски · Девлин Вайтхорн · Бриджит Венлок · Стоддарт Визерс · Герман Винтрингам · Ганхильда из Горсмура · Миранда Гуссокл · Доркас Очаровательная · Мервин Злобный · Роланд Кегг · Элладора Кеттеридж · Грета Кечлав · Бердок Малдун · Бомонт Марджорибэнкс · Мерлин · Мертон Грэйвз · Мирон Вогтэйл · Гиффорд Оллертон · Орсайно Фрастон · Гленмор Пикс · Джастус Пилливикл · Родерик Пламптон · Ярдли Платт · Квонг По · Гулливер Поукби · Джокунда Сайкс · Ньют Саламандер · Хевлок Свитинг · Алмерик Соубридж · Гроган Стамп · Геспер Старки · Эдгар Струглер · Норвел Твонк · Тилли Ток · Селестина Уорлок · Адальберт Уоффлинг · Перпетуа Фанкорт · Гловер Хипворт · Уилфред Элфик · Энгист из Вудкрофта |

|

п•о•р Владельцы «Даров Смерти» |

||

|---|---|---|

| Бузинная палочка | Смерть (создатель) · Антиох Певерелл · Эмерик Отъявленный · Эгберт Эгоист · Годелот · Геревард · Варнава Деверилл · Локсий · Аркус или Ливий · (нет точных данных кто именно) · Майкью Грегорович · Геллерт Грин-де-Вальд · Альбус Дамблдор · Драко Малфой · Лорд Волан-де-Морт (не подчинялась) · Гарри Поттер |  |

| Воскрешающий камень | Смерть (создатель) · Кадм Певерелл · Марволо Мракс · Морфин Мракс · Лорд Волан-де-Морт · Альбус Дамблдор · Гарри Поттер | |

| Мантия-невидимка | Смерть (создатель) · Игнотус Певерелл · Сын Игнотуса Певерелла · Иоланта Певерелл · (несколько поколений Поттеров) · Генри Поттер · Флимонт Поттер · Джеймс Поттер · Альбус Дамблдор · Гарри Поттер · Джеймс Сириус Поттер · Альбус Северус Поттер |

Гарри Поттер

Гарри Поттер — главный персонаж произведений про мальчика, который выжил после смертельного заклинания темного властелина, которого мир знал как Тома Редла младшего или как Волан-де-морта. Участник и победитель турнира трех волшебников. После победы над темным повелителем и его сторонниками стал мракоборцем.

Родители

Отцом мальчика был Джеймс Поттер, единственный сын Флимонта и Клавдии Поттер. Джеймс родился очень поздно, так как его родители не могли забеременеть, но после продажи компании главой семейства сразу родился сын Джеймс. Флимонт и Клавдия баловали мальчика и давали ему все самое лучшее — он рос в любви и довольстве, мальчик с детства рос наглым, но всю жизнь был против темных искусств.

Матерью мальчика была маглорожденная Лили Эванс, которая в первое время презирала Джеймса и его компанию за вечные издевательства над ее другом Северусом Снеггом. Однако, позже и сама разочаровалась в бывшем друге Северусе.

Джеймс и Лили начали встречаться на последних курсах и продолжили после окончания школы. Когда обоим родителям было 28 лет у них родился Гарри Поттер. Дед и бабка Гарри по отцовской линии не увидели своего внука.

Смерть родителей

Родители Гарри Поттера были противниками темного повелителя и являлись участниками организации «Орден Феникса» созванной для борьбы со сторонниками темного властелина. Одним из сторонников темного повелителя окажется бывший друг Лили Эванс, а именно Северус Снегг.

Находясь в трактире «Кабанья голова» Северус Снегг подслушает разговор Альбуса Дамблдора и Сивиллы Трелони, в котором прорицательница случайно предскажет падение темного лорда. Хозяин трактира Аберфорт Дамблдор обнаружит Северуса Снегга и выгонит его, тому так и не удалось узнать все пророчество, но все известные ему сведения были переданы темному повелителю. Из услышанного нельзя было сделать однозначный вывод о мальчике, которого Волан де морт отметит равным себе. Выбор был сделан самим Воландемортом между Гарри Поттером и Невиллом Долгопупсом. Именно темный властелин отметил мальчика как равного себе.

В дальнейшем темный властелин начал поиск мальчика и в этом ему помог лучший друг Джеймса Поттера — Питер Петтигрю, который и выдал местонахождение мальчика и его семьи лично темному повелителю.

Темный повелитель обнаружит дом Поттеров и снимет тайну хранителя, а затем убьет Джеймса Поттера, который попробует остановить Воландеморта без палочки. Лили Поттер не успеет убежать и начнет умолять темного мага не убивать ее сына. После того как Лили Эванс была убита темный властелин попробует убить мальчика, но заклинание отскочит в самого Тома Редла, и тот потеряет свои силы передав часть своей души в Гарри Поттера.

Сириус Блэк посоветовал Поттерам передать тайну Питеру Петтигрю надеясь, но то что пожиратели смерти продолжат искать его, так как никто не поверит, что Джеймс передал тайну хранителя Питеру. Сириус забеспокоится и наведается в жилище Питера Петтигрю, где не обнаружит хозяина, а потом побежит к дому Поттеров.

Сириус Блэк первым обнаружит уничтоженный дом и убитых друзей, а затем захочет стать опекуном мальчика. Однако, по требованию Альбуса Дамблдора мальчика заберет Рубеус Хагрид и передаст родственникам Лили …

Слухи среди волшебников

Пока Гарри рос среди маглов в семье своей тети Петунии и ее мужа Вернона в мире волшебников стали появляться странные слухи. Многие пожиратели смерти и даже обычные волшебники начали думать, что темный властелин пытался убить мальчика, потому что ему было предсказано, что Гарри Поттер станет его главным соперником, который смог бы стать более сильным и могущественным темным волшебником, чем сам темный властелин.

Многие пожиратели смерти начали думать, что именно Гарри Поттер возглавит их и станет новым темным властелином. Именно поэтому Драко Малфой со своей компанией и захочет подружиться с Гарри.

Однако, эти слухи не подтвердились.

Детство мальчика

Гарри рос болезненным и слабым. Ему часто приходилось недоедать, работать по дому и донашивать одежду своего брата. Несмотря на это он хорошо убегал от всех своих неприятностей, и даже мог ненароком применить случайную магию. Несколько раз он очень странно убегал от преследователей, среди которых был и его брат. Гарри имел проблемы со зрением, которые ему передались от отца.

Все это время он думал, что его родители погибли в автомобильной аварии и не знал о своей магической природе.

Письма от неизвестных

Незадолго до своего 11-го дня рождения Гарри случайно наткнулся на странное письмо адресованное ему и начал вскрывать его в компании дяди и брата. Дядя отобрал письмо и далее не давал Гарри прочитать ни одно такое письмо, которых было очень много.

Пытаясь отстранить мальчика от неизвестных дядя Вернон увозит семью на необитаемый остров и селится в непригодном для жилья острове.

На остров прибывает посланец Рубеус Хагрид, который рассказал мальчику правду о его родителях и о нем. Так, мальчик узнает о том, что он волшебник и его приглашают на обучение в школу магии.

Гарри без труда решает бросить беспросветный для себя мир ради школы Хогвартс, который становится для него домом.

Школа Хогвартс

Перед посещением школы Гарри Поттер знакомится с представителем одного из древнейших чистокровных семейств — Роном Уизли, а также с маглорожденной Гермионой Грейнджер. Ребята становятся лучшими друзьями!

В школе Гарри начинает постигать азы магии, больше узнает о себе и о других волшебниках. Так, Гарри узнает о живом, но слабом и лишенном всех сил темном волшебнике, который пьет кровь единорога чтобы вернуть свою силу с помощью философского камня.

Гарри удается одолеть прислужника темного властелина и он заканчивает обучение в школе став настоящим героем. Дальше Гарри и представить себе не может жизни без Хогвартса!

Противостояние с темным повелителем

Темный властелин потерял свою силу после попытки убить Гарри Поттера, но он выжил, и не оставлял попыток вернуться к прежнему могуществу.

В первый год своего обучения Гарри Поттеру удалось не дать темному властелину воскреснуть с помощью философского камня, и тогда тот практически перестал верить в свое возрождение.

На второй год Гарри Поттер обнаружил тайник темного властелина, где скрывалась сущность Тома Реддла, сущность о которой мальчик ничего не подозревал до последнего. Гарри уничтожил причину появления сущности — дневник Тома Реддла.