Главная » Новости » История написания сказки Пушкина о царе Салтане

История написания сказки Пушкина о царе Салтане

Кто-то мечтает стать космонавтом, кто-то певцом, кто-то ветеринаром, кто-то художником или инженером. А Александр Сергеевич Пушкин всегда хотел быть поэтом и писать стихи, трогающие душу и сердце. Его мечты сбылись! Он стал великим русским поэтом, стихи которого знают наизусть не только в России, но и во всем мире.

Первый вариант произведения значительно отличался от конечного результата.

Пушкин использовал за основу народную сказку «По колена ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре». Именно такими чудесными особенностями должен был обладать сын царя.

Пушкин продолжил работу над произведением уже в другой ссылке — в Михайловском селе с 1824 по 1826 год.

В это время сказка обрастает многочисленными подробностями. Появляется отрицательный персонаж, который препятствует царю увидеться с сыном — злая мачеха. Автор добавляет различные чудеса: лукоморье с золотыми цепями, дерущиеся боровы с сыплющимся золотом и 30 богатырей — братья князя.

В 1828 году Александр Пушкин вновь вернулся к работе над сказкой. Именно в этот период он решает написать произведение в стихотворной форме.

Летом 1831 года Пушкин жил в Царском селе: он недавно женился на Наталье Гончаровой, был вдохновлен и очень много работал. Именно в этот период (а точнее 29 августа) он закончил «Сказку о царе Салтане».

Следующие полгода сказка неоднократно дорабатывалась. Известно, что даже император Николай I ознакомился с ней перед публикацией.

В конечном варианте злая мачеха была заменена завистливыми сестрами, волшебные боровы — белочкой с золотыми орехами, богатыри стали морскими витязями. А главный герой стал выделяться не внешними признаками (золотые ноги и серебряные руки), а душевными и умственными качествами.

В 1832 году «Сказка о царе Салтане» была впервые опубликована в сборнике произведений «Стихотворения А. Пушкина». В 2022 году сказке исполнилось 190 лет.

История создания книги [Электронный ресурс]//История написания сказки Пушкина о царе Салтане (hronika.su)

Дата обращения: 11.08.2022

Низовских Т.Е. , библиотекарь Абалакского сельского филиала

Читать об истории создания других книг

Рейтинг пользователей 4.45 ( 13 голосов)

| The Tale of Tsar Saltan | |

|---|---|

The mythical island of Buyan (illustration by Ivan Bilibin). |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Tale of Tsar Saltan |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children» |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Сказка о царе Салтане (1831), by Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (Alexander Pushkin) |

| Related | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, and of the Beautiful Princess-Swan (Russian: «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди», tr. Skazka o tsare Saltane, o syne yevo slavnom i moguchem bogatyre knyaze Gvidone Saltanoviche i o prekrasnoy tsarevne Lebedi listen (help·info)) is an 1831 fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin. As a folk tale it is classified as Aarne–Thompson type 707, «The Three Golden Children», for it being a variation of The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.[1]

Synopsis[edit]

The story is about three sisters. The youngest is chosen by Tsar Saltan (Saltán) to be his wife. He orders the other two sisters to be his royal cook and weaver. They become jealous of their younger sister. When the tsar goes off to war, the tsaritsa gives birth to a son, Prince Gvidon (Gvidón). The older sisters arrange to have the tsaritsa and the child sealed in a barrel and thrown into the sea.

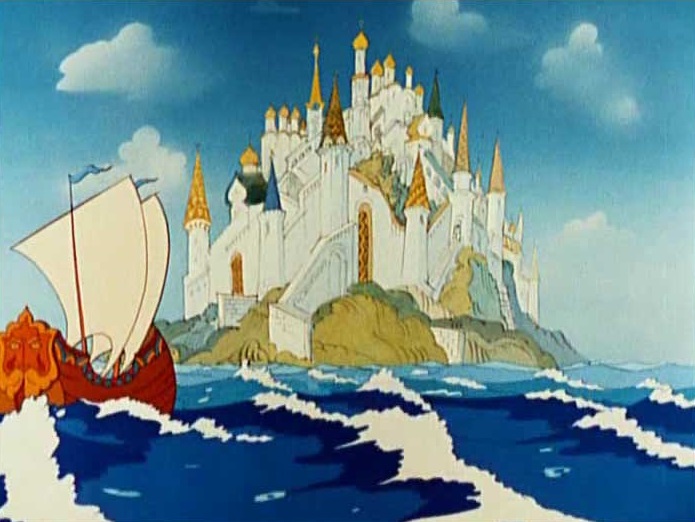

The sea takes pity on them and casts them on the shore of a remote island, Buyan. The son, having quickly grown while in the barrel, goes hunting. He ends up saving an enchanted swan from a kite bird.

The swan creates a city for Prince Gvidon to rule, which some merchants, on the way to Tsar Saltan’s court, admire and go to tell Tsar Saltan. Gvidon is homesick, so the swan turns him into a mosquito to help him. In this guise, he visits Tsar Saltan’s court. In his court, his middle aunt scoffs at the merchant’s narration about the city in Buyan, and describes a more interesting sight: in an oak lives a squirrel that sings songs and cracks nuts with a golden shell and kernel of emerald. Gvidon, as a mosquito, stings his aunt in the eye and escapes.

Back in his realm, the swan gives Gvidon the magical squirrel. But he continues to pine for home, so the swan transforms him again, this time into a fly. In this guise Prince Gvidon visits Saltan’s court again and overhears his elder aunt telling the merchants about an army of 33 men led by one Chernomor that march in the sea. Gvidon stings his older aunt in the eye and flies back to Buyan. He informs the swan of the 33 «sea-knights», and the swan tells him they are her brothers. They march out of the sea, promise to be guards and watchmen of Gvidon’s city, and vanish.

The third time, the Prince is transformed into a bumblebee and flies to his father’s court. There, his maternal grandmother tells the merchants about a beautiful princess that outshine both the sun in the morning and the moon at night, with crescent moons in her braids and a star on her brow. Gvidon stings her nose and flies back to Buyan.

Back to Buyan, he sighs over not having a bride. The swan inquires the reason, and Gvidon explains about the beautiful princess his grandmother described. The swan promises to find him the maiden and bids him await until the next day. The next day, the swan reveals she is the same princess his grandmother described and turns into a human princess. Gvidon takes her to his mother and introduces her as his bride. His mother gives her blessing to the couple and they are wed.

At the end of the tale, the merchants go to Tsar Saltan’s court and, impressed by their narration, decides to visit this fabled island kingdom at once, despite protests from his sisters- and mother-in-law. He and the court sail away to Buyan, and are welcomed by Gvidon. The prince guides Saltan to meet his lost Tsaritsa, Gvidon’s mother, and discovers her family’s ruse. He is overjoyed to find his newly married son and daughter-in-law.

Translation[edit]

The tale was given in prose form by American journalist Post Wheeler, in his book Russian Wonder Tales (1917).[2] It was translated in verse by Louis Zellikoff in the book The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan) (1981).[3]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

The versified fairy tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as tale type ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children». It is also the default form by which the ATU 707 is known in Russian and Eastern European academia.[4][5] Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of this tale type: a variation found «throughout Europe», with the quest for three magical items (as shown in The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird); «an East Slavic form», where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace; and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again.[6]

In a late 19th century article, Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin identified a group of Russian fairy tales with the following characteristics: three sisters boast about grand accomplishments, the youngest about giving birth to wondrous children; the king marries her and makes her his queen; the elder sisters replace their nephews for animals, and the queen is cast in the sea with her son in a barrel; mother and son survive and the son goes after strange and miraculous items; at the end of the tale, the deceit is revealed and the queen’s sisters are punished.[7]

French scholar Gédeon Huet considered this format as «the Slavic version» of Les soeurs jalouses and suggested that this format «penetrated into Siberia», brought by Russian migrants.[8]

Russian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[9]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva suggests that this format must have developed during the period of the Kievan Rus, a period where an intense fluvial trade network developed, since this «East Slavic format» emphasizes the presence of foreign merchants and traders. She also argues for the presence of the strange island full of marvels as another element.[10]

Rescue of brothers from transformation[edit]

In some variants of this format, the castaway boy sets a trap to rescue his brothers and release them from a transformation curse. For example, in Nád Péter («Schilf-Peter«), a Hungarian variant,[11] when the hero of the tale sees a flock of eleven swans flying, he recognizes them as their brothers, who have been transformed into birds due to divine intervention by Christ and St. Peter.

In another format, the boy asks his mother to prepare a meal with her «breast milk» and prepares to invade his brothers’ residence to confirm if they are indeed his siblings. This plot happens in a Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or «Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King»).[12] The mother gives birth to six sons with special traits who are sold to a devil by the old midwife. Some time later, their youngest brother enters the devil’s residence and succeeds in rescuing his siblings.

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva argues that the use of «mother’s milk» or «breast milk» as the key to the reversal of the transformation can be explained by the ancient belief that it has curse-breaking properties.[10] Likewise, scholarship points to an old belief connecting breastmilk and «natal blood», as observed in the works of Aristotle and Galen. Thus, the use of mother’s milk serves to reinforce the hero’s blood relation with his brothers.[13] Russian professor Khemlet Tatiana Yurievna describes that this is the version of the tale type in East Slavic, Scandinavian and Baltic variants,[14] although Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] claimed that this motif is «characteristic» of East Slavic folklore, not necessarily related to variants of tale type 707.[15]

Mythological parallels[edit]

This «Slavic» narrative (mother and child or children cast into a chest) recalls the motif of «The Floating Chest», which appears in narratives of Greek mythology about the legendary birth of heroes and gods.[16][17] The motif also appears in the Breton legend of saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[18]

Central Asian parallels[edit]

Following professor Marat Nurmukhamedov’s (ru) study on Pushkin’s verse fairy tale,[19] professor Karl Reichl (ky) argues that the dastan (a type of Central Asian oral epic poetry) titled Šaryar, from the Turkic Karakalpaks, is «closely related» to the tale type of the Calumniated Wife, and more specifically to The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[20][21]

Variants[edit]

Distribution[edit]

Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] attributed the diffusion of this format amongst the East Slavs to the popularity of Pushkin’s versified tale.[15]

Professor Jack Haney stated that the tale type registers 78 variants in Russia and 30 tales in Belarus.[22]

In Ukraine, a previous analysis by professor Nikolai Andrejev noted an amount between 11 and 15 variants of type «The Marvelous Children».[23] A later analysis by Haney gave 23 variants registered.[22]

Predecessors[edit]

The earliest version of tale type 707 in Russia was recorded in «Старая погудка на новый лад» (1794–1795), with the name «Сказка о Катерине Сатериме» (Skazka o Katyerinye Satyerimye; «The Tale of Katarina Saterima»).[24][25][26] In this tale, Katerina Saterima is the youngest princess, and promises to marry the Tsar of Burzhat and bear him two sons, their arms of gold to the elbow, their legs of silver to the knee, and pearls in their hair. The princess and her two sons are put in a barrel and thrown in the sea.

The same work collected a second variant: Сказка о Труде-королевне («The Tale of Princess Trude»), where the king and queen consult with a seer and learn of the prophecy that their daughter will give birth to the wonder-children: she is to give birth to nine sons in three gestations, and each of them shall have arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up to the knee, pearls in their hair, a shining moon on the front and a red sun on the back of the neck. This prediction catches the interest of a neighboring king, who wishes to marry the princess and father the wonder-children.[27][28]

Another compilation in the Russian language that precedes both The Tale of Tsar Saltan and Afanasyev’s tale collection was «Сказки моего дедушки» (1820), which recorded a variant titled «Сказка о говорящей птице, поющем дереве и золо[то]-желтой воде» (Skazka o govoryashchyey ptitse, poyushchyem dyeryevye i zolo[to]-zhyeltoy vodye).[26]

Early-20th century Russian scholarship also pointed that Arina Rodionovna, Pushkin’s nanny, may have been one of the sources of inspiration to his versified fairy tale Tsar Saltan. Rodionovna’s version, heard in 1824, contains the three sisters; the youngest’s promise to bear 33 children, and a 34th born «of a miracle» — all with silver legs up to the knee, golden arms up to the elbows, a star on the front, a moon on the back; the mother and sons cast in the water; the quest for the strange sights the sisters mention to the king in court. Rodionovna named the prince «Sultan Sultanovich», which may hint at a foreign origin for her tale.[29]

East Slavic languages[edit]

Russia[edit]

Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev collected seven variants, divided in two types: The Children with Calves of Gold and Forearms of Silver (in a more direct translation: Up to the Knee in Gold, Up to the Elbow in Silver),[30][31] and The Singing Tree and The Speaking Bird.[32][33] Two of his tales have been translated into English: The Singing-Tree and the Speaking-Bird[34] and The Wicked Sisters. In the later, the children are male triplets with astral motifs on their bodies, but there is no quest for the wondrous items.

Another Russian variant follows the format of The Brother Quests for a Bride. In this story, collected by Russian folklorist Ivan Khudyakov [ru] with the title «Иванъ Царевичъ и Марья Жолтый Цвѣтъ» or «Ivan Tsarevich and Maria the Yellow Flower», the tsaritsa is expelled from the imperial palace, after being accused of giving birth to puppies. In reality, her twin children (a boy and a girl) were cast in the sea in a barrel and found by a hermit. When they reach adulthood, their aunts send the brother on a quest for the lady Maria, the Yellow Flower, who acts as the speaking bird and reveals the truth during a banquet with the tsar.[35][36]

One variant of the tale type has been collected in «Priangarya» (Irkutsk Oblast), in East Siberia.[37]

In a tale collected in Western Dvina (Daugava), «Каровушка-Бялонюшка», the stepdaughter promises to give birth to «three times three children», all with arms of gold, legs of silver and stars on their heads. Later in the story, her stepmother dismisses her stepdaughter’s claims to the tsar, by telling him of strange and wondrous things in a distant kingdom.[38] This tale was also connected to Pushkin’s Tsar Saltan, along with other variants from Northwestern Russia.[39]

Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin gave the summary of variant collected by Romanov about a «Сын Хоробор» («Son Horobor»): a king has three daughters, the other has an only son, who wants to marry the youngest sister. The other two try to impress him by flaunting their abilities in weaving (sewing 30 shirts with only one «kuzhalinka», a fiber) and cooking (making 30 pies with only a bit of wheat), but he insists on marrying the third one, who promises to bear him 30 sons and a son named «Horobor», all with a star on the front, the moon on the back, with golden up to the waist and silver up to knees. The sisters replace the 30 sons for animals, exchange the prince’s letters and write a false order for the queen and Horobor to be cast into the sea in a barrel. Horobor (or Khyrobor) prays to god for the barrel to reach safe land. He and his mother build a palace on the island, which is visited by merchants. Horobor gives the merchants a cat that serves as his spy on the sisters’ extraordinary claims.[40]

Another version given by Potanin was collected in Biysk by Adrianov: a king listens to the conversations of three sisters, and marries the youngest, who promises to give birth to three golden-handed boys. However, a woman named Yagishna replaces the boys for a cat, a dog and a «korosta». The queen and the three animals are thrown in the sea in a barrel. The cat, the dog and the korosta spy on Yagishna telling about the three golden-handed boys hidden in a well and rescue them.[41]

In a Siberian tale collected by A. A. Makarenko in Kazachinskaya Volost, «О царевне и её трех сыновьях» («The Tsarevna and her three children»), two girls – a peasant’s daughter and Baba Yaga’s daughter – talk about what they would do to marry the king. The girl promises to give birth to three sons: one with legs of silver, the second with legs of gold, and the third with a red sun on the front, a bright moon on the neck, and stars braided in his hair. The king marries her. Near the sons’ delivery (in three consecutive pregnancies), Baba Yaga is brought to be the queen’s midwife. After each boy’s birth, she replaces them with a puppy, a kitten, and a block of wood. The queen is cast into the sea in a barrel with the animals and the object until they reach the shore. The puppy and the kitten act as the queen’s helper and rescue the three biological sons sitting on an oak tree.[42]

Another tale was collected from a 70-year-old teller named Elizaveta Ivanovna Sidorova, in Tersky District, Murmansk Oblast, in 1957, by Dimitri M. Balashov. In her tale, «Девять богатырей — по колен ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре» («Nine bogatyrs — up to the knees in gold, up to the elbows in silver»), a girl promises to give birth to 9 sons with arms of silver and legs of gold, and the sun, moon, stars and a «dawn» adorning their heads and hair. A witch named yaga-baba replaced the boys with animals and things to trick the king. The queen is thrown in the sea with the animals, which act as her helpers. When yaga-baba, on the third visit, tells the king of a place where there are nine boys just as the queen described, the animals decide to rescue them.[43]

In a tale collected from teller A. V. Chuprov with the title «Федор-царевич, Иван-царевич и их оклеветанная мать» («Fyodor Tsarevich, Ivan Tsarevich and their Calumniated Mother»), a king passes by three servants and inquires them about their skills: the first says she can work with silk, the second can bake and cook, and the third says whoever marries her, she will bear him two sons, one with hands covered in gold and legs in silver, a sun on the front, stars on the sides and a moon on the back, and another with arms of a golden color and legs with a silvery tint. The king takes the third servant as his wife. The queen writes a letter to be delivered to the king, but the messenger stops by a bath house and its contents are altered to tell the king his wife gave birth to two puppies. The children are baptized and given the named Fyodor and Ivan. Ivan is given to another king, while the mother is cast in a barrel with Fyodor; both wash ashore on Buyan. Fyodor tries to make contact with some merchants on a ship. Fyodor reaches his father’s kingdom and overhears the conversation about the wondrous sights: a talking squirrel on a tree that tells fairy tales and a similar looking youth (his brother Ivan) on a distant kingdom. Fyodor steals a magic carpet, rescues Ivan and flies back to Buyan with his brother, a princess and an old woman.[44] The tale was also classified as type 707, thus related to Russian tale «Tsar Saltan».[45]

In a tale collected by Chudjakov with the title Der weise Iwan («The Wise Ivan»), Ivan Tsarevich, the son of a tsar, pays a visit to a king and his three daughters. He listens to their conversation: the elder sister promises to weave trousers and shirts for the tsar’s son with a single flax; the middle one that she can weave the same with only a spool of thread, and the youngest that she can bear him six sons, the seventh a «wise Ivan», and all of them with arms of gold up to the elbow, legs of silver up the knee and pearls in their hair. The tsar’s son marries the youngest sister, to the jealousy of the elder sisters. While Ivan Tsarevich goes to war, the jealous sisters join with a sorceress to defame the queen, by taking the children as soon as they are born and replace them for animals. After the third pregnancy, the queen and her son, wise Ivan, are cast in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore on an island and they live there. Some time later, merchants come to the island and later visit Ivan Tsarevich’s court to tell of strange sights they have seen: exotic felines (sables and martens); singing birds of paradise from the jealous sisters’ aunt’s garden; and six sons with arms of gold, legs of silver and pearls in their hair. Wise Ivan returns to his mother and asks his mother to bake six cakes. Wise Ivan flies to the sorceress’s hut and rescues his brothers.[46]

Belarus[edit]

In a Belarusian tale collected by Evdokim Romanov (ru) with the name «Дуб Дорохвей» or «Дуб Дарахвей» («The Dorokhveï Oak») (fr), a widowed old man marries another woman, who detests his three daughters and orders her husband to dispose of them. The old man takes them to the swamp and abandons the girls there. They notice that their father is not with them, take refuge under a pine tree and begin to cry over their situation, their tears producing a river. The tsar, seeing the river, orders their servants to find its source.[a] They find the three maidens and take them to the king, who inquires about their origin: they say they were expelled from home. The tsar asks each maiden what they can do, and the youngest says she will give birth to 12 sons, their legs of gold, their waist of silver, the moon on the forehead and a small star on the back of the neck. The tsar chooses the third sister, and she bears the 12 sons while he is away. The sisters falsify a letter with a lie that she gave birth to animals and she should be thrown in the sea in a barrel. Eleven of her sons are put in a leather bag and thrown in the sea, but they wash ashore on an island where the Dorokhveï Oak lies. The oak is hollowed, so they make their residence there. Meanwhile, mother and her 12th son are thrown in the sea in a barrel, but leave the barrel as soon as it washes ashore on another island. The son tells her he will rescue his eleven brothers by asks her to bake cakes with her breastmilk. After the siblings are reunited, the son turns into an insect to spy on his aunts and eavesdrop on the conversation about the kingdom of wonders, one of them, a cat that walks and tells stories and tales [fr].[47]

Ukraine[edit]

In a Ukrainian tale, «Песинський, жабинський, сухинський і золотокудрії сини цариці» («Pesinsky, Zhabinsky, Sukhinsky[b] and the golden-haired sons of the queen»), three sisters are washing clothes in the river when they see in the distance a man rowing a boat. The oldest says it might be God, and if it is, may He take her, because she can feed many with a piece of bread. The second says it might be a prince, so she says she wants him to take her, because she will be able to weave clothes for a whole army with just a yarn. The third recognizes him as the tsar, and promises that, after they marry, she will give birth to twelve sons with golden curls. When the girl, now queen, gives birth, the old midwife takes the children, tosses them in a well and replaces them with animals. After the third birth, the tsar consults his ministers and they advise him to cast the queen and her animal children in the sea in a barrel. The barrel washes ashore an island and the three animals build a castle and a glass bridge to mainland. When some sailors visit the island, they visit the tsar to report on the strange sights on the island. The old midwife, however, interrupts their narration by revealing somewhere else there is something even more fantastical. Pesinsky, Zhabinsky and Sukhinsky spy on their audience and run away to fetch these things and bring them to their island. At last, the midwife reveals that there is a well with three golden-curled sons inside, and Pesinsky, Zhabinsky and Sukhinsky rescue them. The same sailors visit the strange island (this time the true sons of the tsar are there) and report their findings to the tsar, who discovers the truth and orders the midwife to be punished.[48][49] According to scholarship, professor Lev Grigorevich Barag noted that this sequence (dog helping the calumniated mother in finding the requested objects) appears as a variation of the tale type 707 only in Ukraine, Russia, Bashkir and Tuvan.[50]

In a tale summarized by folklorist Mykola Sumtsov with the title «Завистливая жена» («The Envious Wife»), the girl promises to bear a son with a golden star on the forehead and a moon on his navel. She is persecuted by her sister-in-law.[51][52]

In a South Russian (Ukrainian) variant collected by Ukrainian folklorist Ivan Rudchenko [ru], «Богатырь з бочки» («The Bogatyr in a barrel»), after the titular bogatyr is thrown in the sea with his mother, he spies on the false queen to search the objects she describes: a cat that walks on a chain, a golden bridge near a magical church and a stone-grinding windmill that produces milk and eight falcon-brothers with golden arms up to the elbow, silver legs up to the knees, golden crown, a moon on the front and stars on the temples.[53][54]

Baltic languages[edit]

Latvia[edit]

According to the Latvian Folktale Catalogue, tale type 707, «The Three Golden Children», is known in Latvia as Brīnuma bērni («Wonderful Children»), comprising 4 different redactions. Its first redaction registers the highest number of tales and follows The Tale of Tsar Saltan: the king marries the youngest of three sisters, because she promises to bear him many children with wonderful traits, her sisters replace the children for animals and their youngest is cast into the sea in a barrel with one of her sons; years later, her son seeks the strange wonders the sisters mention (a cat that dances and tells stories, and a group of male brothers that appear somewhere on a certain place).[55]

Lithuania[edit]

According to professor Bronislava Kerbelyte [lt], the tale type is reported to register 244 (two hundred and forty-four) Lithuanian variants, under the banner Three Extraordinary Babies, with and without contamination from other tale types.[56] However, only 39 variants in Lithuania contain the quest for the strange sights and animals described to the king. Kerbelytė also remarks that many Lithuanian versions of this format contain the motif of baking bread with the hero’s mother’s breastmilk to rescue the hero’s brothers.[57]

In a variant published by Fr. Richter in Zeitschrift für Volkskunde with the title Die drei Wünsche («The Three Wishes»), three sisters spend an evening talking and weaving, the youngest saying she would like to have a son, bravest of all and loyal to the king. The king appears, takes the sisters, and marries the youngest. Her son is born and grows up exceptionally fast, much to the king’s surprise. One day, he goes to war and sends a letter to his wife to send their son to the battlefield. The queen’s jealous sisters intercept the letter and send him a frog dressed in fine clothes. The king is enraged and replies with a written order to cast his wife in the water. The sisters throw the queen and her son in the sea in a barrel, but they wash ashore in an island. The prince saves a hare from a fox. The prince asks the hare about recent events. Later, the hare is disenchanted into a princess with golden eyes and silver hair, who marries the prince.[58]

Finnic languages[edit]

Estonia[edit]

The tale type is known in Estonia as Imelised lapsed («The Miraculous Children»). Estonian folklorists identified two opening episodes: either the king’s son finds the three sisters, or the three sisters are abandoned in the woods and cry so much their tears create a river that flows to the king’s palace.[a] The third sister promises to bear the wonder children with astronomical motifs on their bodies. The story segues into the Tale of Tsar Saltan format: the mother and the only child she rescued are thrown into the sea; the son grows up and seeks the wonders the evil aunts tell his father about: «a golden pig, a wonderous cat, miraculous children».[59]

Regional tales[edit]

Folklorist William Forsell Kirby translated an Estonian version first collected by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald,[60] with the name The Prince who rescued his brothers: a king with silver-coated legs and golden-coated arms marries a general’s daughter with the same attributes. When she gives birth to her sons, her elder sister sells eleven of her nephews to «Old Boy» (a devil-like character) while the queen is banished with her twelfth son and cast adrift into the sea in a barrel. At the end of the tale, the youngest prince releases his brothers from Old Boy and they transform into doves to reach their mother.[61]

In a tale from the Lutsi Estonians collected by linguist Oskar Kallas with the name Kuningaemand ja ta kakstõistkümmend poega («The Queen and her Twelve Sons»), a man remarries and, on orders of his new wife, takes his three daughters to the forest on the pretext of picking up berries, and abandons them there. The king’s bird flies through the woods and finds the girls. The animal inquires them about their skills: the elder one says she can feed the whole world with an ear of wheat; the middle one that she can clothe the whole world with a single linen thread, and the third that she will bear 12 sons, each with a moon on the head, the sun, and stars on their bodies. The bird carries each one to the king, who takes them in. Years later, the king marries the third girl, and she gives birth to three sons in her first pregnancy. Her elder sister takes the boys and drops them in a swamp, replacing them with kittens. This happens again with the next pregnancies: as soon as they are born, the triplets are replaced for animals (puppies in the second, piglets in the third, and lambs in the fourth). However, in the fourth pregnancy, the queen hides one of her sons with her. The king orders her to cast his wife in the sea in an iron boat with her son. The son begs for an island to receive them, and his mother blesses his prayer. After they wash ashore on the island, the boy wishes the island is filled with golden and silver trees, with apples with half of gold and half of silver. His mother blesses his wish, and it happens. He next wishes for a palace larger than his father’s, an army greater than his, and finally for a bridge to connect the island to the continent. Later, he asks his mother to bake 12 cakes with her breastmilk, for he intends to rescue his older brothers. He crosses the bridge and reaches a swamp, then finds a moss-covered hut. He enters the hut and places the 12 cakes on the table. His eleven brothers — everyone shining due to their birthmarks — come to the hut and eat the cakes. Their younger brother appears and convinces them to join their mother on the island. Later, the son wishes for instruments to play, which draws the attention of his father, the king. The king comes to the island and learns of the whole truth.[62]

Kallas published a homonymous variant from the Lutsi Estonians in abbreviated form. In this tale, a king meets three maidens on the road; the third promises to bear him 12 sons with the sun and the moon on the head, a star on their breast, hands of gold and feet of silver. The king and the maiden marry; the children are replaced by animals as soon as they are born, and the mother and her last son are cast into the sea in a sack. The first thing her son does is find his brothers. Later, after he rescues his brothers, he flies back to his father’s court to spy on him and the other maidens, and learns of the sights: a cat that lives in oak and provides clothes for its owner; a cow with a lake between its horns; and a boar that sows his own fields and bakes his own bread.[63]

In another tale from the Lutsi, published with the title Kolm õde («Three Sisters»), a tsar has three daughters and is a great musician. One day, he leaves home and does not return. His daughters go looking for him and find him dead. They begin to cry, their tears creating a river that flows to another kingdom. The son of another tsar orders his servant to discover its origin and finds the girls. The sisters are brought to the prince’s presence and are questioned about their skills: the elder promises to feed the entire country with one pea, the middle one that she can feed the country’s horses with one grain of oat, and the youngest promises to give birth to 12 sons. The prince marries the third sister. In time, she gives birth to 12 sons. A sequence of falsified letters lies that she gave birth to animal-headed children, and must be punished by being cast in the sea. The prince’s wife and a son are thrown into the sea in a barrel and wash ashore on an island. The son grows up and goes hunting around the island. He prepares to shoot at a swan, but the swan pleads to be spared, and helps the boy three times: the first, to pull a thread by the seashore (which guides his father’s ship to the island); secondly, to throw 11 pebbles on the sea (which summons his 11 brothers to the island); finally, to fish a goldfish (which leads his father’s ship again to the island).[64]

Karelia[edit]

Karelian researchers register that the tale type is «widely reported» in Karelia, with 55 variants collected,[65] apart from tales considered to be fragments or summaries of The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[66] According to their research, at least 50 of them follow the Russian redaction (see above), while 5 of them are closer to the Western European tales.[65]

According to Karelian scholarship, the witch Syöjätär is the recurrent antagonist in Karelian variants of tale type 707,[67] especially in tales from South Karelia.[68]

Regional tales[edit]

In a Karelian tale, «Девять золотых сыновей» («Nine Golden Sons»), the third sister promises to give birth to «three times three» children, their arms of gold up to the elbow, the legs of silver up to the knees, a moon on the temples, a sun on the front and stars in their hair. The king overhears their conversation and takes the woman as his wife. On their way, they meet a woman named Syöjätär, who insists to be the future queen’s midwife. She gives birth to triplets in three consecutive pregnancies, but Syöjätär replaces them for rats, crows and puppies. The queen saves one of her children and is cast into a sea in a barrel. The remaining son asks his mother to bake bread with her breastmilk to rescue his brothers.[69][70]

Author Eero Salmelainen collected a tale titled Veljiensä etsijät ja joutsenina lentäjät («One who seeks brothers flying as swans»), which poet Emmy Schreck translated as Die neun Söhne des Weibes («The woman’s nine children») and indicated a Russian-Karelian source for this tale. In this variant, three sisters walk in the forest and talk to each other, the youngest promising to bear nine children in three pregnancies. The king’s son overhears them and decides to marry the youngest, and she bears the wonder children with hands of gold, legs of silver, sunlight in their hair, moonlight shining around it, the «celestial chariot» (Himmelswagen, or Ursa Major) on their shoulder, and stars in their underarms. The king dispatches a servant to look for a washerwoman and a witch offers her services. The witch replaces the boys for animals, takes them to the woods and hides them under a white stone. After the third pregnancy, the mother hides two of her sons «on her sleeve» and is banished with them on a barrel cast in the sea. The barrel washes ashore on an island. Both boys grow up in days, and capture a talking pike that tells them to cut it open to find magical objects inside its entrails. They use the objects to build a grand house on the island for themselves and their mother. After a merchant visits the island and reports to their father, the king’s son arrives on the island and makes peace with his wife. Sometime later, both sons ask his mother to prepare some cakes with her breastmilk, so they can look for their remaining brothers, still missing. Both brothers spare a seagull who carries them across the sea to another country, where they find their seven brothers under an avian transformation curse.[71]

In a tale from Pudozh, collected in 1939 and published in 1982 with the title «Про кота-пахаря» («About the Pakharya Cat»), three sisters promise great things if they marry Ivan, the merchant’s son; the youngest sister, named Barbara (Varvara), promises to bear three sons with golden arms and a red sun on the front. She marries Ivan and bears three sons, in three consecutive pregnancies, but the sons are replaced for puppies and the third is cast in barrel along with his mother. The son grows up in hours, becomes a young man, and both wash ashore on a deserted island. Whatever he wishes for, his mother blesses him so that his prayers go «from his lips to God’s ears». And so appear a magical cat that sings poems and a bath house that rejuvenates people.[72]

In a Karelian tale collected in 1947 and published in 1963 with the title Yheksän kultaista poikua (Russian: Девять золотых сыновей, romanized: Devyat’ zolotikh synovei, lit. ‘Nine Golden Sons’), a woman has three daughters. One day, they talk among themselves: the elder promises to prepare food for the whole army with just one grain of barley, the middle one that she can weave clothes for the army with only a thread of linen; and the youngest promises to bear three sons with hands of gold, legs of silver, a moon on their temples, pearls in their eyes, the Ursa Major constellation on their shoulders and «heavenly stars» on their backs. The sisters repeat their conversation in a bath house, and the king’s son overhears them. The king’s son marries the youngest sister and takes her to his palace. On the way back, the couple finds a woman named Suyoatar and take her as their midwife. Suyoatar replaces the children with three wolfcubs and hides the children under a white stone. The same event happens with the next two pregnancies (three crows in the second, and three magpies in the third), but, on the third pregnancy, she hides on son with her. Mother and son are cast in the sea in a barrel, but the barrel washes ashore. They begin to live on an island, and the son asks his mother to sew 8 shirts and bake 8 koloboks with her breastmilk, for he intends to rescue his brothers.[73]

In a Karelian tale collected in 1937 and published in 1983 with the title Kolme sisäreštä (Russian: Три сестры, romanized: Tri sestry, lit. ‘Three Sisters’), an old couple have three daughters. One day, during the «vierista» holiday, they pay a visit to the Vierista akka (Old Woman Vierista), but hide in a cow’s hide. Vierista drags the girls to a forest and abandons them there. They climb a tree for shelter and the king’s on, during a hunt, finds them. The king’s son brings them to the palace, and the youngest sister strikes the king’s son’s fancy the most. While at the castle, the girls go to a bath house and talk to one another: the elder wants to marry the royal cook and promises to weave clothes for the whole army with a single thread; the middle one wants to marry the royal steward and promises to cook food for the whole army with a single grain; the youngest wants to marry the king’s son and promises to bear three children, the oldest a daughter, all with hands of gold, legs of silver, a moon on their temples; the Ursa Major on the shoulders and the stars in their back. The children are born, but the sisters replace them by animals and cast in the water. The children are saved by a gardener and, years later, are sent for a fountain of water of life, the ringing tree and the talking bird.[74]

Finland[edit]

Tale type 707 is known in Finland as Kolme kultaista poikaa («Three Golden Boys»).[75][76]

In a late 19th century article, Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne noted that the story was found «all over» Finland, but it was «especially common» in the eastern part of the country, namely, in Arkhangelsk and Olonets. Moreover, Finnish variants «always» («всегда») begin with the three sisters, and the youngest promising to bear children with marvelous qualities: golden hands and silver feet, or with astral birthmarks (moon on the forehead and sun on the crown). The number of promised children may vary between 3, 9, and 12, and, according to Aarne, nine is the number that appears in variants from Eastern Finland. Lastly, in all variants («всехъ вариантахъ»), the queen and one of her sons are cast in the sea in a barrel.[77]

According to the Finnish Folktale Catalogue, established by scholar Pirkko-Liisa Rausmaa, the type of redaction is the following; the third sister promises to bear either nine or three golden sons, the witch Syöjättar replaces the sons for crows, and the mother and the only son(s) she rescued are thrown in the sea in a barrel.[78]

Regional tales[edit]

Finnish author Eero Salmelainen [fi] collected three Finnish variants he grouped under the banner Naisen yhdeksän poikaa («The Woman’s Nine Children»).[79] In one of his tales, titled Tynnyrissä kaswanut Poika («The boy who grew in a barrel»), summarized by W. Henry Jones and Lajos Kropf, the king overhears three daughters of a peasant woman boasting about their abilities, the third sister promising to bear three sets of triplets with the moon on their temples, the sun on the top of their heads, hands of gold, and feet of silver. She marries the king, and her envious older sisters substitute the boys for animals. She manages to save her youngest child, but both are cast into the sea in a barrel. They reach an island; her son grows up at a fast rate and asks his mother to prepare nine cakes with her milk, so he can use them to rescue his brothers.[80]

In another tale, titled Saaressa eläjät and translated into German as Die auf der Insel Lebenden («Living on an island»), the third sister promises to bear three sons in each pregnancy and marries the king. The king sends for a midwife and a mysterious woman offers her services — the witch Syöjätär. The witch replaces the children with animals, but by the third time, the mother hides her latest son. The mother is cast in the sea in a barrel and washes ashore on an island. She and her son pray to God for a house, and He grants their prayer. The king marries another wife, the daughter of Syojatar, who tells him about wonder in a faraway place: three pigs, six stallions, and eight golden boys on a large stone. The son decides to find the eight boys and asks his mother to prepare cakes with her breastmilk. He brings his eight brothers back to their mother. The king decides to visit the island, meets his wife and nine sons, and discovers the truth.[81][82]

August Löwis de Menar translated a Finnish variant from Ingermanland, with the title Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne («Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King»): a pair of siblings, a boy and a girl, flee from home and live in the forest. One day, the king finds the girl, naked atop a tree, and asks if she is a baptized woman. They marry and she gives birth to two golden-haired sons in each pregnancy, but they are replaced for animals and given to a devil. The mother gives birth to a seventh son and she is banished in the sea in a barrel. They reach an island and God helps them by creating a grand palace. The seventh son asks his mother to prepare cakes with her breastmilk because he decides to find his six brothers. He reaches the house of the devil and takes his siblings back to his mother. One day, the king visits their island palace and wishes to be told a story. The seventh son tells the king, their father, the story of their family. The king recognizes his sons and reconciles with his wife.[83]

In a Finnish tale translated into English as Mielikki and her nine sons, three maidens go for a walk in the woods and talk to each other: the first promises to make bread for the whole army with three barley seeds; the second that she can weave clothes for the army with three stalks of flax, and the third, named Mielikki, that she will bear nine sons. A king named Aslo overhears their boasts and chooses Mielikki as his wife. The bards celebrate the occasion with a song that describes the royal children as having hands of gold, feet of silver, a «shining dawn» on their shoulders, a moonbeam on their chests, and «stars of heaven» on their foreheads. The king’s servants procure a midwife for the queen and find an old woman named Noita-Akka. Each time the queen bears three sons that are replaced by three crows by Noita-Akka and hidden near a white stone in the woods. The third time, however, Mielikki protects two sons from the midwife’s machinations, but she and her two children are cast in the sea in a barrel. Mother and children wash ashore on an island and live out their days there. One day, trade merchants come to King Aslo’s court and describe the two boys they saw on the island. King Aslo finds his wife and sons and takes them back. After the joyous reunion, the two remaining brothers decide to look for their missing siblings. At the end of the tale, they find an old woman’s house, and the old woman tells them their seven brothers become gulls by wearing feather robes, so, in order to lift their curse, the pair must burn the brothers’ feather robes.[84]

Veps people[edit]

Karelian scholarship reports 15 variants from Veps sources. Most of which also follow the Russian (or East Slavic) redaction of the tale type 707 (that is, «The Tale of Tsar Saltan»).[85]

At least one variant of type 707 was collected from a Veps source by linguist Paul Ariste and published in 1964.[86]

Mordvin people[edit]

Russian author Stepan V. Anikin [ru] published a tale from the Mordvin people titled «Двенадцать братьев» («Twelve Brothers»). In this tale, a czar’s son, still single, likes to overhear the conversation under people’s windows. In one house, he overhears three sisters who are spinning and talking: they each talk about marrying the czar’s son, but the elder promises to clothe an entire regiment with a single spool of thread; the middle one that she can bake a piece of bread so large to feed two regiments with a single bite, and the youngest promises to bear twelve sons, each with a sun on the front, a moon on the back of the head, stars in their hair. The czar’s son chooses the youngest as his wife and marries her. When she is pregnant for the first time, the czar’s son looks for a midwife, and finds a woman named Vedyava by the river and hires her. Vedyava takes the first son, hides him elsewhere, and replaces him with a kitten. This happens with the next ten pregnancies, until the czar’s son, fed up with the apparently false promises, orders his wife to be locked up in an iron barrel with her last son and cast in the sea. His order is carried out, and the pair sinks to the bottom of the ocean. Fifteen years pass, and son and mother pray to God for the barrel to wash ashore on any island. This happens, and they find themselves on land. The boy finds three men quarreling about an ax, a cloth, and a magic cudgel and steals them to build a house for him and his mother. Later, some fishermen come to the island and depart to visit the czar’s son, now the czar himself and married to Vedyava. The boy turns into a little mosquito and flies incognito to his father’s court. Vedyava mocks the fishermen’s report, and tells of other miraculous sights: first, a boar-pig that plows fields with its paws and sows with its snout; second, a mare that foals with each step; third, a tree with silver bells that ring with the wind, and a singing bird perched on it; lastly, about eleven boys that live somewhere, each with a sun on the front, a moon on the back of the head, and stars in their hair. After each visit, the boy finds the boar-pig, the mare and its foals, the bell-tree and the bird. As for the last sight, the boy recognizes it is about his brothers and asks his mother to bake eleven loaves of bread for the road, then goes on a quest for them. With the help of a magic bird, the boy is carried to the brothers’ hut and takes them back to their mother.[87]

Other regions[edit]

Zaonezh’ya[edit]

In a tale from Zaonezh’ya [fr] with the title «Про Ивана-царевича» («About Ivan-Tsarevich»), recorded in 1982, three sisters in a bath house talk among themselves, the youngest says she will bear nine sons with golden legs, silver arms and pearls in their hair. She marries Ivan-Tsarevich. A local witch named Yegibikha, who wants her daughter, Beautiful Nastasya, to marry Ivan, acts as the new queen’s midwife and replaces eight of her sons for animals. The last son and mother are thrown into the sea in a barrel and wash ashore on an island. The child grows up in days and asks his mother to prepare koluboks with her breastmilk. He rescues his brothers with the koluboks and takes them to the island. Finally, the son wishes that a bridge appears between the island and the continent, and that visitors come to their new home. As if granting his wish, an old beggar woman comes and visits the island, and later goes to Ivan-Tsarevich to tell him about it.[88]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1900 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in which the popular piece Flight of the Bumblebee is found.

- 1943 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, traditionally animated film directed by Brumberg sisters.[89]

- 1966 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, feature film directed by Aleksandr Ptushko.[90]

- 1984 – The Tale of Tsar Saltan, USSR, traditionally animated film directed by Ivan Ivanov-Vano and Lev Milchin.[91]

- 2012 — an Assyrian Aramaic poem by Malek Rama Lakhooma and Hannibal Alkhas, loosely based on the Pushkin fairy tale, was staged in San Jose, CA (USA). Edwin Elieh composed the music available on CD.

Gallery of illustrations[edit]

Ivan Bilibin made the following illustrations for Pushkin’s tale in 1905:

-

Tsar Saltan at the window

-

The Island of Buyan

-

Flight of the mosquito

-

The Merchants Visit Tsar Saltan

See also[edit]

This basic folktale has variants from many lands. Compare:

- «The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird»

- «Princess Belle-Etoile»

- «The Three Little Birds»

- Ancilotto, King of Provino

- «The Bird of Truth»

- «The Water of Life»

- The Wicked Sisters

- The Boys with the Golden Stars

- A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers

- The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead

- The Hedgehog, the Merchant, the King and the Poor Man

- Silver Hair and Golden Curls

- Sun, Moon and Morning Star

- The Golden-Haired Children

- Les Princes et la Princesse de Marinca

- Two Pieces of Nuts

- The Children with the Golden Locks (Georgian folktale)

- The Pretty Little Calf

- The Rich Khan Badma

- The Story of Arab-Zandiq

- The Bird that Spoke the Truth

- The Story of The Farmer’s Three Daughters

- The Golden Fish, The Wonder-working Tree and the Golden Bird

- King Ravohimena and the Magic Grains

- Zarlik and Munglik (Uzbek folktale)

- The Child with a Moon on his Chest (Sotho)

- The Story of Lalpila (Indian folktale)

References[edit]

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc. 2010. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ Wheeler, Post. Russian wonder tales: with a foreword on the Russian skazki. London: A. & C. Black. 1917. pp. 3-27.

- ^ The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan). Malysh Publishers. 1981.

- ^ Barag, Lev [ru]. Belorussische Volksmärchen. Akademie-Verlag, 1966. p. 603.

- ^ Власов, С. В. (2013). Некоторые Французские И ИталЬянскиЕ Параллели К «Сказке о Царе Салтане» А. С. ПушКИНа Во «Всеобщей Библиотеке Романов» (Bibliothèque Universelle des Romans) (1775–1789). Мир русского слова, (3), 67–74.

- ^ Goldberg, Christine. «Review: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume II. In: Journal of Folklore Research. Online publication: March 16, 2016.

- ^ «Восточные параллели к некоторым русским сказкам» [Eastern Parallels to Russian Fairy Tales]. In: Григорий Потанин. «Избранное». Томск. 2014. pp. 179–180.

- ^ Huet, Gédeon. «Le Conte des soeurs jalouses». In: Revue d’ethnographie et de sociologie. Deuxiême Volume. Paris: E. Leroux, 1910. Gr. in-8°, p. 195.

- ^ Johns, Andreas (2010). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 244–246. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- ^ a b Зуева, Т. В. «Древнеславянская версия сказки «Чудесные дети» («Перевоплощения светоносных близнецов»)». In: Русская речь. 2000. № 3, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Róna-Sklarek, Elisabet (1909). «5: Schilf-Peter». Ungarische Volksmärchen [Hungarian folktales] (in German). Vol. 2 (Neue Folge ed.). Leipzig: Dieterich. pp. 53–65.

- ^ Löwis of Menar, August von. (1922). «15. Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne». Finnische und estnische Volksmärchen [Finnish and Estonian folktales]. Die Märchen der Weltliteratur;[20] (in German). Jena: Eugen Diederichs. pp. 53–59.

- ^ Parkes, Peter. «Fosterage, Kinship, and Legend: When Milk Was Thicker than Blood?». In: Comparative Studies in Society and History 46, no. 3 (2004): 590 and footnote nr. 4. Accessed June 8, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3879474.

- ^ Хэмлет Татьяна Юрьевна (2015). Карельская народная сказка «Девять золотых сыновей». Финно-угорский мир, (2 (23)): 17-18. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/karelskaya-narodnaya-skazka-devyat-zolotyh-synovey (дата обращения: 27.08.2021).

- ^ a b c Barag, Lev. Belorussische Volksmärchen. Akademie-Verlag, 1966. p. 603.

- ^ Holley, N. M. “The Floating Chest”. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 69 (1949): 39–47. doi:10.2307/629461.

- ^ Beaulieu, Marie-Claire. «The Floating Chest: Maidens, Marriage, and the Sea». In: The Sea in the Greek Imagination. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. pp. 90–118. Accessed May 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt17xx5hc.7.

- ^ Milin, Gaël (1990). «La légende bretonne de Saint Azénor et les variantes medievales du conte de la femme calomniée: elements pour une archeologie du motif du bateau sans voiles et sans rames». In: Memoires de la Societé d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de Bretagne 67. pp. 303-320.

- ^ Нурмухамедов, Марат Коптлеуич. Сказки А. С. Пушкина и фольклор народов Средней Азии (сюжетные аналогии, перекличка образов). Ташкент. 1983.

- ^ Reichl, Karl. Turkic Oral Epic Poetry: Traditions, Forms, Poetic Structure. Routledge Revivals. Routledge. 1992. pp. 123, 235–249. ISBN 9780815357797.

- ^ Reichl, Karl. «Epos als Ereignis Bemerkungen zum Vortrag der zentralasiatischen Turkepen». In: Hesissig, W. (eds). Formen und Funktion mündlicher Tradition. Abhandlungen der Nordrhein-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, vol 95. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden. 1993. p. 162. ISBN 978-3-322-84033-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-84033-2_12

- ^ a b Haney, Jack V. The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev. Volume II: Black Art and the Neo-Ancestral Impulse. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 536–556. muse.jhu.edu/book/42506.

- ^ Andrejev, Nikolai P. «A Characterization of the Ukrainian Tale Corpus». In: Fabula 1, no. 2 (1958): 233. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1958.1.2.228

- ^ Старая погудка на новый лад (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Старая погудка на новый лад: Русская сказка в изданиях конца XVIII века». Б-ка Рос. акад. наук. Saint Petersburg: Тропа Троянова, 2003. pp. 96-99. Полное собрание русских сказок; Т. 8. Ранние собрания.

- ^ a b Власов Сергей Васильевич (2013). «Некоторые Французские И ИталЬянскиЕ Параллели К «Сказке о Царе Салтане» А. С. ПушКИНа Во «Всеобщей Библиотеке Романов» (Bibliothèque Universelle des Romans) (1775–1789)». Мир Русского Слова (Мир русского слова ed.) (3): 67–74.

- ^ Старая погудка на новый лад (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ «Старая погудка на новый лад: Русская сказка в изданиях конца XVIII века». Б-ка Рос. акад. наук. Saint Petersburg: Тропа Троянова, 2003. pp. 297-305. Полное собрание русских сказок; Т. 8. Ранние собрания.

- ^ Азадовский, М. К. «СКАЗКИ АРИНЫ РОДИОНОВНЫ». In: Литература и фольклор. Leningrad: Государственное издательство, «Художественная литература», 1938. pp. 273-278.

- ^ По колена ноги в золоте, по локоть руки в серебре. In: Alexander Afanasyev. Народные Русские Сказки. Vol. 2. Tale Numbers 283–287.

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume II, Volume 2. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 411–426. ISBN 978-1-62846-094-0

- ^ Поющее дерево и птица-говорунья. In: Alexander Afanasyev. Народные Русские Сказки. Vol. 2. Tale Numbers 288–289.

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume II, Volume 2. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2015. pp. 427–432. ISBN 978-1-62846-094-0

- ^ Alexander Afanasyev. Russian Folk-Tales. Edited and Translated by Leonard A. Magnus. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. 1915. pp. 264–273.

- ^ Khudi︠a︡kov, Ivan Aleksandrovich. «Великорусскія сказки» [Tales of Great Russia]. Vol. 3. Saint Petersburg: 1863. pp. 35-45.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 – Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2001. pp. 354–361. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ Матвеева, Р. П. (2011). Народные русские сказки Приангарья: локальная традиция [National Russian Fairytales of Angara Area: the Local Tradition]. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Педагогика. Филология. Философия, (10), 212-213. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/narodnye-russkie-skazki-priangarya-lokalnaya-traditsiya (дата обращения: 24.04.2021).

- ^ Agapkina, T.A. «Blagovernaia Tsaritsa Khitra Byla Mudra: on One Synonymous Pair in the Russian Folklore». In: Studia Litterarum, 2020, vol. 5, no 2, pp. 367-368. (In Russ.) DOI: 10.22455/2500-4247-2020-5-2-336-389. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/blagovernaya-tsaritsa-hitra-byla-mudra-ob-odnoy-sinonimicheskoy-pare-v-russkom-folklore (дата обращения: 27.08.2021).

- ^ Сказки в записях А. С. Пушкина и их варианты в фольклорных традициях Северо-Запада России (с экспедиционными материалами из фондов Фольклорно-этнографического центра имени А. М. Мехнецова Санкт-Петербургской государственной консерватории имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова). К 220-летию со дня рождения А. С. Пушкина: учебное пособие / Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова; составители Т. Г. Иванова, Г. В. Лобкова; вступительная статья и комментарии Т. Г. Ивановой; редактор И. В. Светличная.–СПб.: Скифия-принт, 2019. pp. 70-81. ISBN 978-5-98620-390-4.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. «Избранное». Томск. 2014. pp. 170–171.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. «Избранное». Томск. 2014. p. 171.

- ^ Записки Красноярского подотдела Восточно-Сибирского отдела Императорского Русского географического общества по этнографии. Т. 1, вып. 1: Русские сказки и песни в Сибири и другие материалы. Красноярск, 1902. pp. 24-27.

- ^ Балашов, Дмитрий Михайлович. «Сказки Терского берега Белого моря». Наука. Ленинградское отделение, 1970. pp. 155-160, 424.

- ^ «Русская сказка. Избранные мастера». Том 1. Moskva/Leningrad: Academia, 1934. pp. 104-121.

- ^ «Русская сказка. Избранные мастера». Том 1. Moskva/Leningrad: Academia, 1934. pp. 126-128.

- ^ Russische Volksmärchen. Edited by Julian Krzyżanowski, Gyula Ortuta and Wolfgang Steinitz. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2022 [1964]. pp. 233-240, 554. https://doi-org.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/9783112526682-038

- ^ Чарадзейныя казкі: У 2 ч. Ч 2 / [Склад. К. П. Кабашнікаў, Г. A. Барташэвіч; Рэд. тома В. К. Бандарчык]. 2-е выд., выпр. i дапрац. Мн.: Беларуская навука, 2003. pp. 291-297. (БНТ / НАН РБ, ІМЭФ).

- ^ Krushelnytsky, Antin. Ukraïnsky almanakh. Kyiv: 1921. pp. 3–10.

- ^ «Украинские народные сказки». Перевод Г. Петникова. Moskva: ГИХЛ, 1955. pp. 256-262.

- ^ Салова С.А., & Якубова Р.Х. (2016). Культурное взаимодействие восточнославянского фольклора и русской литературы как национальных явлений в научном наследии Л. Г. Барага. Российский гуманитарный журнал, 5 (6): 638. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/kulturnoe-vzaimodeystvie-vostochnoslavyanskogo-folklora-i-russkoy-literatury-kak-natsionalnyh-yavleniy-v-nauchnom-nasledii-l-g-baraga (дата обращения: 27.08.2021).

- ^ Сумцов, Николай Фёдорович. «Малорусскія сказки по сборникамь Кольберга і Мошинской» [Fairy Tales from Little Russia in the collections of Kolberg and Moshinskaya]. In: Этнографическое обозрени № 3, Год. 6-й, Кн. XXII. 1894. p. 101.

- ^ Coxwell, C. F. Siberian And Other Folk Tales. London: The C. W. Daniel Company, 1925. p. 558.

- ^ Rudchenko, Ivan. «Народные южнорусские сказки» [South-Russian Folk Tales]. Выпуск II [Volume II]. Kyiv: Fedorov, 1870. pp. 89-99.

- ^ Григорий Потанин. «Избранное». Томск. 2014. p. 172.

- ^ Arājs, Kārlis; Medne, A. Latviešu pasaku tipu rādītājs. Zinātne, 1977. p. 112.

- ^ Skabeikytė-Kazlauskienė, Gražina. Lithuanian Narrative Folklore: Didactical Guidelines. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University. 2013. p. 30. ISBN 978-9955-21-361-1.

- ^ Литовские народные сказки [Lithuanian Folk Tales]. Составитель [Compilation]: Б. Кербелите. Мoskva: ФОРУМ; НЕОЛИТ, 2015. p. 230. ISBN 978-5-91134-887-8; ISBN 978-5-9903746-8-3

- ^ Richter, Fr. «Lithauische Märchen IV». In: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde, 1. Jahrgang, 1888, pp. 356–358.

- ^ Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 2. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teaduskirjastus, 2014. pp. 689-691, 733-734. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Kreutzwald, Friedrich Reinhold. Ehstnische Märchen. Zweiter Hälfte. Halle: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses. 1881. pp. 142–152.

- ^ Kirby, William Forsell. The hero of Esthonia and other studies in the romantic literature of that country. Vol. 2. London: John C. Nimmo. 1895. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Kallas, Oskar. Kaheksakümmend Lutsi maarahva muinasjuttu, kogunud Oskar Kallas. Jurjevis (Tartus) Schmakenburg’i trükikojas, 1900. pp. 283-289 (tale nr. 22).

- ^ Kallas, Oskar. Kaheksakümmend Lutsi maarahva muinasjuttu, kogunud Oskar Kallas. Jurjevis (Tartus) Schmakenburg’i trükikojas, 1900. pp. 289-290 (tale nr. 23).

- ^ Vaese Mehe Õnn: Muinasjutte Lutsimaalt. Koostanud ja toimetanud Inge Annom, Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik ja Kärri Toomeos-Orglaan. Tartu: EKM TEADUSKIRJASTUS, 2018. pp. 157-161. ISBN 978-9949-586-82-0.

- ^ a b Карельские народные сказки [Karelian Folk Tales]. Репертуар Марии Ивановны Михеевой [Repertoire of Marii Ivanovy Mikheeva]. Петрозаводск: Карельский научный центр РАН, 2010. p. 44. ISBN 978-5-9274-0414-8.

- ^ «Русские Народные Сказки: Пудожского Края» [Russian Folk Tales: Pudozh Region]. Karelia, 1982. pp. 8, 288 (tales nr. 15 and 16), 317 (tales nr. 348 and 349), 326 (tale nr. 460).

- ^ «Карельские народные сказки» [Karelian Folk Tales]. Moskva, Leningrad: Издательства Академии наук СССР, 1963. pp. 514-515.

- ^ «Карельские народные сказки: Южная Карелия» [Karelian Folk Tales: South Karelia]. Leningrad: Издательства Академии наук СССР, 1967. pp. 502-503.

- ^ «Карельская сказка: Девять золотых сыновей». Карелия, 1984. Translator: A. Stepanova.

- ^ Хэмлет Татьяна Юрьевна (2015). Карельская народная сказка «Девять золотых сыновей». Финно-угорский мир, (2 (23)): 17-18. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/karelskaya-narodnaya-skazka-devyat-zolotyh-synovey (дата обращения: 24.01.2022).

- ^ Schrek, Emmy. Finnische Märchen. Weimar: Hermann Böhler. 1887. pp. 85–97.

- ^ «Русские Народные Сказки: Пудожского Края» [Russian Folk Tales: Pudozh Region]. Karelia, 1982. pp. 257-259.

- ^ «Карельские народные сказки» [Karelian Folk Tales]. Moskva, Leningrad: Издательства Академии наук СССР, 1963. pp. 320-323 (Karelian text), 323-326 (Russian translation), 514-515 (classification).

- ^ «Карельские народные сказки» [Karelian Folk Tales]. Moskva, Leningrad: Издательства Академии наук СССР, 1963. pp. 326-329 (Karelian text), 329-333 (Russian translation), 515 (classification).

- ^ Apo, Satu. «Ihmesatujen teemat ja niiden tulkinta». In: Sananjalka 22. Turku: 1980. p. 133.

- ^ Apo, Satu (1989). ”Kaksi Luokkaa, Kaksi satuperinnettä: Havaintoja 1800-Luvun Kansan-Ja Taidesaduista”. In: Sananjalka 31 (1): 149. https://doi.org/10.30673/sja.86520.

- ^ Аарне А. «Несколько параллелей финских сказок с русскими и прочими славянскими». In: «Живая старина [ru]«. Vol. 8, 1898, Tome 1. pp. 108-109.

- ^ Rausmaa, Pirkko-Liisa. Suomalaiset kansansadut: Ihmesadut. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1988. p. 501. ISBN 9789517175272

- ^ Salmelainen, Eero. Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita. Helsingissä: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. 1871. pp. 87–108.

- ^ Jones, W. Henry; Kropf, Lajos. The Folk-Tales of the Magyars. London: Published for the Folk-lore society by Elliot Stock. 1889. p. 337 (Notes on Folk-tale nr. 11).

- ^ Erman, George Adolf, ed. (1854). «Die auf der Insel Lebenden» [The Island People]. In: Archiv für Wissenschaftliche Kunde von Russland 13, pp. 580–586. (In German)

- ^ Jones, W. Henry; Kropf, Lajos. The Folk-Tales of the Magyars. London: Published for the Folk-lore society by Elliot Stock. 1889. p. 385 (Notes on tale nr. 25).

- ^ Löwis of Menar, August von. Finnische und estnische Volksmärchen. Jena: Eugen Diederichs. 1922. pp. 53–59, 292.

- ^ Bowman, James Cloyd and Bianco, Margery Williams. Tales from a Finnish tupa. Chicago: A. Whitman & Co., 1964 [1936]. pp. 161–170.

- ^ Онегина Н. Ф. «Русско-вепсско-карельские фольклорные связи на материале волшебной сказки». In: Межкультурные взаимодействия в полиэтничном пространстве пограничного региона: Сборник материалов международной научной конференции. Петрозаводск, 2005. pp. 194, 197. ISBN 5-9274-0188-0.

- ^ Salve, Kristi. «Paul Ariste and the Veps Folklore». In: Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 29 (2005). p. 183. doi:10.7592/FEJF2005.20.veps

- ^ Аникин, Степан Васильевич. «Мордовские народные сказки» [Mordvin Folktales]. С. Аникин. Санкт-Петербург: Род. мир, 1909. pp. 70-82.

- ^ «Сказка заонежья». Карелия. 1986. pp. 154-157, 212.

- ^ «Russian animation in letters and figures | Films | «THE TALE ABOUT TSAR SALTAN»«. www.animator.ru.

- ^ «The Tale of Tsar Saltan» – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ «Russian animation in letters and figures | Films | «A TALE OF TSAR SALTAN»«. www.animator.ru.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Russian folklorist Lev Barag stated that the motif of the sisters’ tears forming a river appears in the folklore of Asian peoples.[15]

- ^ Their names may be related to Ukrainian words for «dog» (pes) and «frog/toad» (žȁba).

Further reading[edit]

- Azadovsky, Mark, and McGavran, James. «The Sources of Pushkin’s Fairy Tales». In: Pushkin Review 20 (2018): 5-39. doi:10.1353/pnr.2018.0001.

- Mazon, André. «Le Tsar Saltan». In: Revue des études slaves, tome 17, fascicule 1–2, 1937. pp. 5–17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/slave.1937.7637; [www.persee.fr/doc/slave_0080-2557_1937_num_17_1_7637 persee.fr]

- Orlov, Janina. «Chapter 2. Orality and literacy, continued: Playful magic in Pushkin’s Tale of Tsar Saltan». In: Children’s Literature as Communication: The ChiLPA project. Edited by Roger D. Sell [Studies in Narrative 2]. John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2002. pp. 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.2.05orl

- Oranskij, I. M. «A Folk-Tale in the Indo-Aryan Parya Dialect (A Central Asian Variant of the Tale of Czar Saltan)». In: East and West 20, no. 1/2 (1970): 169–78. Accessed September 5, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29755508.

- Wachtel, Michael. «Pushkin’s Turn to Folklore». In: Pushkin Review 21 (2019): 107–154. doi:10.1353/pnr.2019.0006.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Russian Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- A. D. P. Briggs (January 1983). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20340-7.

- (in Russian) Сказка о царе Салтане available at Lib.ru

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan, transl. by Louis Zellikoff

| The Tale of Tsar Saltan | |

|---|---|

The mythical island of Buyan (illustration by Ivan Bilibin). |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Tale of Tsar Saltan |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children» |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Сказка о царе Салтане (1831), by Александр Сергеевич Пушкин (Alexander Pushkin) |

| Related | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

The Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, and of the Beautiful Princess-Swan (Russian: «Сказка о царе Салтане, о сыне его славном и могучем богатыре князе Гвидоне Салтановиче и о прекрасной царевне Лебеди», tr. Skazka o tsare Saltane, o syne yevo slavnom i moguchem bogatyre knyaze Gvidone Saltanoviche i o prekrasnoy tsarevne Lebedi listen (help·info)) is an 1831 fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin. As a folk tale it is classified as Aarne–Thompson type 707, «The Three Golden Children», for it being a variation of The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.[1]

Synopsis[edit]

The story is about three sisters. The youngest is chosen by Tsar Saltan (Saltán) to be his wife. He orders the other two sisters to be his royal cook and weaver. They become jealous of their younger sister. When the tsar goes off to war, the tsaritsa gives birth to a son, Prince Gvidon (Gvidón). The older sisters arrange to have the tsaritsa and the child sealed in a barrel and thrown into the sea.

The sea takes pity on them and casts them on the shore of a remote island, Buyan. The son, having quickly grown while in the barrel, goes hunting. He ends up saving an enchanted swan from a kite bird.

The swan creates a city for Prince Gvidon to rule, which some merchants, on the way to Tsar Saltan’s court, admire and go to tell Tsar Saltan. Gvidon is homesick, so the swan turns him into a mosquito to help him. In this guise, he visits Tsar Saltan’s court. In his court, his middle aunt scoffs at the merchant’s narration about the city in Buyan, and describes a more interesting sight: in an oak lives a squirrel that sings songs and cracks nuts with a golden shell and kernel of emerald. Gvidon, as a mosquito, stings his aunt in the eye and escapes.

Back in his realm, the swan gives Gvidon the magical squirrel. But he continues to pine for home, so the swan transforms him again, this time into a fly. In this guise Prince Gvidon visits Saltan’s court again and overhears his elder aunt telling the merchants about an army of 33 men led by one Chernomor that march in the sea. Gvidon stings his older aunt in the eye and flies back to Buyan. He informs the swan of the 33 «sea-knights», and the swan tells him they are her brothers. They march out of the sea, promise to be guards and watchmen of Gvidon’s city, and vanish.

The third time, the Prince is transformed into a bumblebee and flies to his father’s court. There, his maternal grandmother tells the merchants about a beautiful princess that outshine both the sun in the morning and the moon at night, with crescent moons in her braids and a star on her brow. Gvidon stings her nose and flies back to Buyan.

Back to Buyan, he sighs over not having a bride. The swan inquires the reason, and Gvidon explains about the beautiful princess his grandmother described. The swan promises to find him the maiden and bids him await until the next day. The next day, the swan reveals she is the same princess his grandmother described and turns into a human princess. Gvidon takes her to his mother and introduces her as his bride. His mother gives her blessing to the couple and they are wed.

At the end of the tale, the merchants go to Tsar Saltan’s court and, impressed by their narration, decides to visit this fabled island kingdom at once, despite protests from his sisters- and mother-in-law. He and the court sail away to Buyan, and are welcomed by Gvidon. The prince guides Saltan to meet his lost Tsaritsa, Gvidon’s mother, and discovers her family’s ruse. He is overjoyed to find his newly married son and daughter-in-law.

Translation[edit]

The tale was given in prose form by American journalist Post Wheeler, in his book Russian Wonder Tales (1917).[2] It was translated in verse by Louis Zellikoff in the book The Tales of Alexander Pushkin (The Tale of the Golden Cockerel & The Tale of Tsar Saltan) (1981).[3]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

The versified fairy tale is classified in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as tale type ATU 707, «The Three Golden Children». It is also the default form by which the ATU 707 is known in Russian and Eastern European academia.[4][5] Folklore scholar Christine Goldberg identifies three main forms of this tale type: a variation found «throughout Europe», with the quest for three magical items (as shown in The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird); «an East Slavic form», where mother and son are cast in a barrel and later the sons build a palace; and a third one, where the sons are buried and go through a transformation sequence, from trees to animals to humans again.[6]

In a late 19th century article, Russian ethnographer Grigory Potanin identified a group of Russian fairy tales with the following characteristics: three sisters boast about grand accomplishments, the youngest about giving birth to wondrous children; the king marries her and makes her his queen; the elder sisters replace their nephews for animals, and the queen is cast in the sea with her son in a barrel; mother and son survive and the son goes after strange and miraculous items; at the end of the tale, the deceit is revealed and the queen’s sisters are punished.[7]

French scholar Gédeon Huet considered this format as «the Slavic version» of Les soeurs jalouses and suggested that this format «penetrated into Siberia», brought by Russian migrants.[8]

Russian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[9]

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva suggests that this format must have developed during the period of the Kievan Rus, a period where an intense fluvial trade network developed, since this «East Slavic format» emphasizes the presence of foreign merchants and traders. She also argues for the presence of the strange island full of marvels as another element.[10]

Rescue of brothers from transformation[edit]

In some variants of this format, the castaway boy sets a trap to rescue his brothers and release them from a transformation curse. For example, in Nád Péter («Schilf-Peter«), a Hungarian variant,[11] when the hero of the tale sees a flock of eleven swans flying, he recognizes them as their brothers, who have been transformed into birds due to divine intervention by Christ and St. Peter.

In another format, the boy asks his mother to prepare a meal with her «breast milk» and prepares to invade his brothers’ residence to confirm if they are indeed his siblings. This plot happens in a Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or «Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King»).[12] The mother gives birth to six sons with special traits who are sold to a devil by the old midwife. Some time later, their youngest brother enters the devil’s residence and succeeds in rescuing his siblings.

Russian scholar T. V. Zueva argues that the use of «mother’s milk» or «breast milk» as the key to the reversal of the transformation can be explained by the ancient belief that it has curse-breaking properties.[10] Likewise, scholarship points to an old belief connecting breastmilk and «natal blood», as observed in the works of Aristotle and Galen. Thus, the use of mother’s milk serves to reinforce the hero’s blood relation with his brothers.[13] Russian professor Khemlet Tatiana Yurievna describes that this is the version of the tale type in East Slavic, Scandinavian and Baltic variants,[14] although Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] claimed that this motif is «characteristic» of East Slavic folklore, not necessarily related to variants of tale type 707.[15]

Mythological parallels[edit]

This «Slavic» narrative (mother and child or children cast into a chest) recalls the motif of «The Floating Chest», which appears in narratives of Greek mythology about the legendary birth of heroes and gods.[16][17] The motif also appears in the Breton legend of saint Budoc and his mother Azénor: Azénor was still pregnant when cast into the sea in a box by her husband, but an angel led her to safety and she gave birth to future Breton saint Budoc.[18]

Central Asian parallels[edit]

Following professor Marat Nurmukhamedov’s (ru) study on Pushkin’s verse fairy tale,[19] professor Karl Reichl (ky) argues that the dastan (a type of Central Asian oral epic poetry) titled Šaryar, from the Turkic Karakalpaks, is «closely related» to the tale type of the Calumniated Wife, and more specifically to The Tale of Tsar Saltan.[20][21]

Variants[edit]

Distribution[edit]