The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

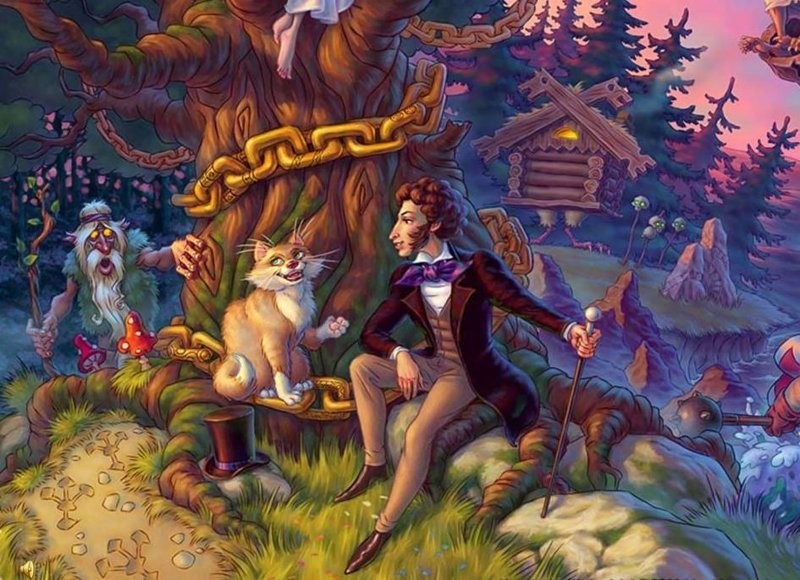

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

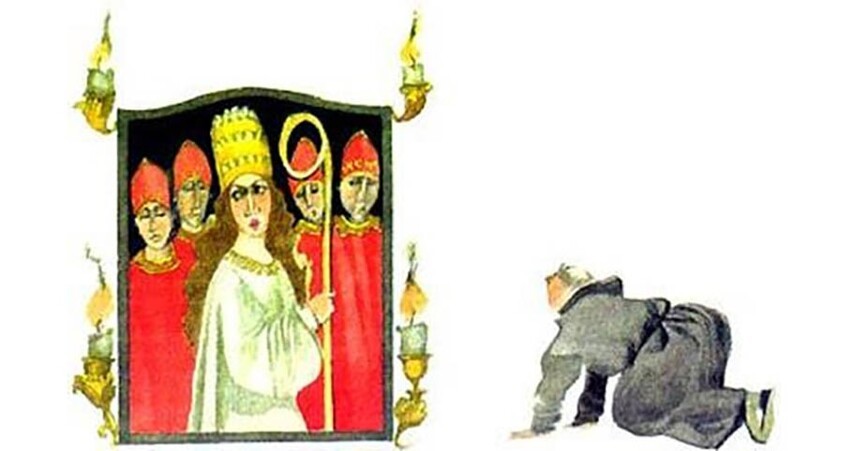

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395

External links[edit]

The fairy tale commemorated on a Soviet Union stamp

The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Russian: «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке», romanized: Skazka o rybake i rybke) is a fairy tale in verse by Alexander Pushkin, published 1835.

The tale is about a fisherman who manages to catch a «Golden Fish» which promises to fulfill any wish of his in exchange for its freedom.

Textual notes[edit]

Pushkin wrote the tale in autumn 1833[1] and it was first published in the literary magazine Biblioteka dlya chteniya in May 1835.

English translations[edit]

Robert Chandler has published an English translation, «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish» (2012).[2][3]

Grimms’ Tales[edit]

It has been believed that Pushkin’s is an original tale based on the Grimms’ tale,[4] «The Fisherman and his Wife».[a]

Azadovsky wrote monumental articles on Pushkin’s sources, his nurse «Arina Rodionovna», and the «Brothers Grimm» demonstrating that tales recited to Pushkin in his youth were often recent translations propagated «word of mouth to a largely unlettered peasantry», rather than tales passed down in Russia, as John Bayley explains.[6]

Still, Bayley»s estimation, the derivative nature does not not diminish the reader’s ability to appreciate «The Fisherman and the Fish» as «pure folklore», though at a lesser scale than other masterpieces.[6] In a similar vein, Sergei Mikhailovich Bondi [ru] emphatically accepted Azadovsky’s verdict on Pushkin’s use of Grimm material, but emphasized that Pushkin still crafted Russian fairy tales out of them.[7]

In a draft version, Pushkin has the fisherman’s wife wishing to be the Roman Pope,[8] thus betraying his influence from the Brother Grimms’ telling, where the wife also aspires to be a she-Pope.[9]

Afanasyev’s collection[edit]

The tale is also very similar in plot and motif to the folktale «The Goldfish» Russian: Золотая рыбка which is No. 75 in Alexander Afanasyev’s collection (1855–1867), which is obscure as to its collected source.[7]

Russian scholarship abounds in discussion of the interrelationship between Pushkin’s verse and Afanasyev’s skazka.[7] Pushkin had been shown Vladimir Dal’s collection of folktales.[7] He seriously studied genuine folktales, and literary style was spawned from absorbing them, but conversely, popular tellings were influenced by Pushkin’s published versions also.[7]

At any rate, after Norbert Guterman’s English translation of Asfaneyev’s «The Goldfish» (1945) appeared,[10] Stith Thompson included it in his One Hundred Favorite Folktales, so this version became the referential Russian variant for the ATU 555 tale type.[11]

Plot summary[edit]

In Pushkin’s poem, an old man and woman have been living poorly for many years. They have a small hut, and every day the man goes out to fish. One day, he throws in his net and pulls out seaweed two times in succession, but on the third time he pulls out a golden fish. The fish pleads for its life, promising any wish in return. However, the old man is scared by the fact that a fish can speak; he says he does not want anything, and lets the fish go.

When he returns and tells his wife about the golden fish, she gets angry and tells her husband to go ask the fish for a new trough, as theirs is broken, and the fish happily grants this small request. The next day, the wife asks for a new house, and the fish grants this also. Then, in succession, the wife asks for a palace, to become a noble lady, to become the ruler of her province, to become the tsarina, and finally to become the Ruler of the Sea and to subjugate the golden fish completely to her boundless will. As the man goes to ask for each item, the sea becomes more and more stormy, until the last request, where the man can hardly hear himself think. When he asks that his wife be made the Ruler of the Sea, the fish cures her greed by putting everything back to the way it was before, including the broken trough.

Analysis[edit]

The Afanasiev version «The Goldfish» is catalogued as type ATU 555, «(The) Fisherman and his Wife», the type title deriving from the representative tale, Brothers Grimm’s tale The Fisherman and His Wife.[11][12][13]

The tale exhibits the «function» of «lack» to use the terminology of Vladimir Propp’s structural analysis, but even while the typical fairy tale is supposed to «liquidate’ the lack with a happy ending, this tale type breaches the rule by reducing the Russian couple back to their original state of dire poverty, hence it is a case of «lack not liquidated».[13] The Poppovian structural analysis sets up «The Goldfish» tale for comparison with a similar Russian fairy tale, «The Greedy Old Woman (Wife)».[13]

Adaptations[edit]

- 1866 — Le Poisson doré (The Golden Fish), «fantastic ballet», choreography by Arthur Saint-Léon, the music by Ludwig Minkus.

- 1917 — The Fisherman and the Fish by Nikolai Tcherepnin, op. 41 for orchestra

- 1937 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, animated film by Aleksandr Ptushko.[14]

- 1950 — The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish, USSR, classic traditionally animated film by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky.,[15]

- 2002 — About the Fisherman and the Goldfish, Russia, stop-motion film by Nataliya Dabizha.[16]

See also[edit]

- Odnoklassniki.ru: Click for luck, comedy film (2013)

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ D. N. Medrish [ru] also opining that «we have folklore texts that arose under the indisputable Pushkin influence».[5]

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction.

- ^ Chandler (2012).

- ^ Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Chandler (2012), Alexander Pushkin, introduction and Pilinovsky (2014), pp. 396–397.

- ^ Medrish, D. N. (1980) Literatura i fol’klornaya traditsiya. Voprosy poetiki Литература и фольклорная традиция. Вопросы поэтики [Literature and folklore tradition. Questions of poetics]. Saratov University p. 97. apud Sugino (2019), p. 8

- ^ a b Bayley, John (1971). «2. Early Poems». Pushkin: A Comparative Commentary. Cambridge: CUP Archive. p. 53. ISBN 0521079543.

- ^ a b c d e Sugino (2019), p. 8.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna Andreevna (1997). Meyer, Ronald (ed.). My Half Century: Selected Prose. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 387, n38. ISBN 0810114852.

- ^ Sugino (2019), p. 10.

- ^ Guterman (2013). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish» pp. 528–532.

- ^ a b Thompson (1974). Title page (pub. years). «The Goldfish». pp. 241–243. Endnote, p. 437 «Type 555».

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The types of international folktales. Vol. 1. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. p. 273. ISBN 9789514109638.

- ^ a b c Somoff, Victoria (2019), Canepa, Nancy L. (ed.), «Morals and Miracles: The Case of ATU 555 ‘The Fisherman and His Wife’«, Teaching Fairy Tales, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0814339360

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1937)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «The Tale About the Fisherman and the Fish (1950)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ «About the Fisherman and the Fish (2002)». Animation.ru. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Bibliography

- Briggs, A. D. P. (1982). Alexander Pushkin: A Critical Study. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Chandler, Robert, ed. (2012). «A Tale about a Fisherman and a Fish». Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. Penguin UK. ISBN 0141392541.

- Guterman, Norbert, tr., ed. (2013) [1945]. «The Goldfish». Russian Fairy Tales. The Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library. Aleksandr Afanas’ev (orig. ed.). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 528–532. ISBN 0307829766.

- Sugino, Yuri (2019), «Pushkinskaya «Skazka o rybake i rybke» v kontekste Vtoroy boldinskoy oseni» Пушкинская «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» в контексте Второй болдинской осени [Pushkin’s“The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”in the Context of the Second Boldin Autumn], Japanese Slavic and East European Studies, 39: 2–25, doi:10.5823/jsees.39.0_2

- Thompson, Stith, ed. (1974) [1968]. «51. The Goldfish». One Hundred Favorite Folktales. Indiana University Press. pp. 241–243, endnote p. 437. ISBN 0253201721.

- Pilinovsky, Helen (2014), «(Review): Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov by Robert Chandler», Marvels & Tales, 28 (2): 395–397, doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.2.0395

External links[edit]

Сказка Пушкина «О рыбаке и рыбке». От немецкой до русской

Кто из нас не знает великолепное поэтическое произведение Александра Сергеевича Пушкина «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке»!? Кто ее не слышал в детстве!? Кто ее не читал своим детям на ночь!? Кто не видел старого советского мультфильма!? Именно со сказок А.С.Пушкина начинается у многих большая любовь к классической русской поэзии. Написанные в народном духе и стихотворной форме, они всегда вызывают восхищение.

Но какова была первооснова этой замечательной сказки? Откуда Пушкин позаимствовал сюжет для своего произведения? Недавно прочитал что «Сказка о рыбаке и рыбке» написана была по мотивам русских народных сказок. А это не так. Конечно, подобные сказки присутствуют в народном фольклоре многих народов. В русском есть подобная сказка «Жадная старуха». Правда действие там разворачивается в лесу, а желания старика исполняет Волшебное дерево. Эту сказку маленькому Саше рассказывала его няня Арина Родионовна. Есть и более древняя версия сюжета — индийская сказка «Золотая рыба», с местным национальным колоритом, здесь Золотая рыба — могущественный златоликий подводный дух Джала Камани. Вполне возможно эрудит Пушкин был знаком и с этой сказкой.

Какое-то время считалось, что основой произведения Пушкина была аналогичная сказка, отраженная в сборнике русских народных сказок А. Афанасьева. Но сказки Афанасьева были опубликованы в 1855 году, тогда как Пушкин написал свое произведение в 1832, а опубликовал в 1835-м. Кроме того сказка в сборнике настолько похожа на вариант Пушкина, что наверняка мы имеем дело с обратным заимствованием, когда авторское произведение уходит в народ (также произошло и с «Коньком-Горбунком» Ершова).

Пушкин никогда не скрывал, что главный сюжет его произведения основан на померанской сказке «О рыбаке и его жене» из сборника сказок братьев Гримм. Поэт читал эти сказки и высоко ценил братьев Гримм. Немудрено, что и взял эту сказку за основу. Но естественно переделал под мотив русских народных сказок, использовав особенности народного стиха. И народная немецкая сказка под гениальным пером Пушкина превращается в исконно русскую.

Во первых у братьев Гримм волшебная рыба это камбала, которая к тому же заколдованный принц. Пушкин заменяет малопоэтическую и малоизвестную для русских крестьян морскую камбалу на просто золотую рыбку без родословной.

У братьев Гримм меркантильная старуха не мелочится, сразу требует новый дом. У Пушкина – новое корыто. Кстати весьма удачная находка поэта – выражение «остаться у разбитого корыта» стало расхожим популярным и хрестоматийным.

Была в немецкой сказке и сцена, где старуха требует сделать её самим… римским папой! Столь забавная просьба брала свои истоки в средневековой европейской истории о том, что одно время в Риме действительно правила женщина под именем Иоанна VIII. В сохранившемся первоначальном варианте Пушкина эта сцена тоже есть:

«Воротился старик к старухе.

Перед ним монастырь латынский

На стенах монахи

Поют латынскую обедню.

Перед ним вавилонская башня.

На самой на верхней на макушке

Сидит его старая старуха,

На старухе сорочинская шапка,

На шапке венец латынский,

На венце тонкая спица,

На спице Строфилус птица».

Но все-таки «латынская обедня» лишала сказку русского колорита и Александр Сергеевич убрал сцену в Ватикане, превратив старуху в вольную царицу:

Старичок к старухе воротился.

Что ж? пред ним царские палаты.

В палатах видит свою старуху,

За столом сидит она царицей,

Служат ей бояре да дворяне,

Наливают ей заморские вины;

Заедает она пряником печатным;

Вкруг ее стоит грозная стража,

На плечах топорики держат.

Изменил Пушкин и концовку сказки. У братьев Гримм вконец оборзевшая старуха хочет стать ни много ни мало, стать Богом. У Пушкина же поначалу старушенция хотела стать «владычицей солнца», но потом поэт изменил просьбу на «владычицу морскую». Это сразу же усилило наглость притязаний бабки — ведь теперь она хотела обрести власть над самой благодетельницей («…Чтоб служила мне рыбка золотая / И была б у меня на посылках»).

Но самое главное это то что Пушкин изменил идейный смысл народных сказок. Как у немецкой, так у русской и индийской. Во всех этих сказках старик тоже поднимается по карьерной лестнице вместе со старухой. Становится владельцем нового дома, дворянином, а затем царем и так далее. За это они оба наказываются: в одних вариантах они превращены в медведей (или в свиней), в других — возвращаются к прежней нищете. Смысл сказки в ее народных вариантах (у всех народов) — «всяк сверчок знай свой шесток».

В пушкинской сказке судьба старика отделена от судьбы старухи; он так и остается простым крестьянином-рыбаком, и чем выше старуха поднимается по «социальной лестнице», тем тяжелее становится гнет, испытываемый стариком. Старуха начинает относиться к старику как к своему рабу, и даже не пускает на порог. То есть Пушкин делает упор не на жадность, а на черную неблагодарность.

Долго у моря ждал он ответа,

Не дождался, к старухе воротился —

Глядь: опять перед ним землянка;

На пороге сидит его старуха,

А пред нею разбитое корыто.

Источник:

Ссылки по теме:

Новости партнёров

реклама