Гензель и Гретель (Гримм)

Материал из Народного Брифли

Перейти к:навигация, поиск

Гензель и Гретель

Hänsel und Gretel · 1812

Краткое содержание сказки

из цикла «Сказки братьев Гримм»

Микропересказ: Чтобы не умереть от голода, мачеха подговаривает отца оставить двоих детей в лесу. Брат и сестра пытаются вернуться, но сбиваются с пути. Блуждая по лесу, они обнаруживают пряничный домик, полный сладостей, набрасываются на лакомства и попадают в плен к ведьме, которая собирается их съесть. Хитростью победив злодейку, дети возвращаются домой.

Этот микропересказ слишком длинный: 344 зн. Оптимальный размер: 190—200 знаков.

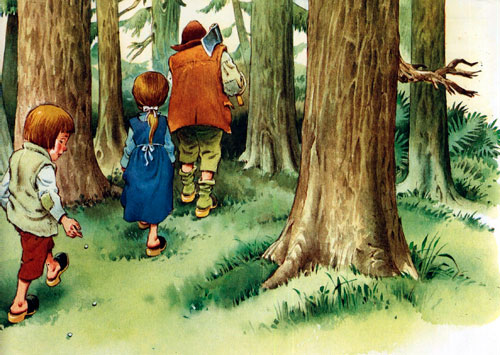

Гензель и Гретель — дети бедного дровосека, который живет в лесу со своей женой. Когда нужда становится нестерпимой, она уговаривает мужа обоих детей в лес и бросить их там. На следующий день дровосек отводит обоих детей в лес. Но Гензель — предусмотрителен: он разбрасывает по дороге белые камушки, и возвращется с сестрой по ним обратно домой. План матери не удается. Вторая попытка — удачливее. В этот раз у детей в руках только хлебные крошки, которые Гензель также разбрасывает по дороге. Их же съедают птицы. Дети тем самым не могут найти дорогу назад. На третий день они выходят к домику, состоящему из хлеба, пирогов и сахара. Часть его они съедают, чтобы утолить голод. В нем живет ведьма, являющаяся людоедкой.

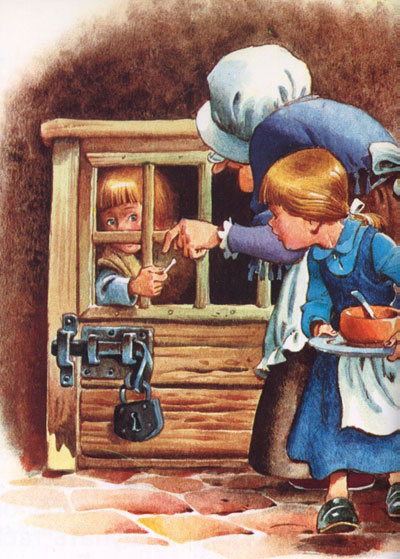

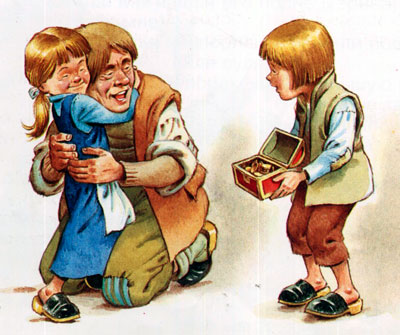

Она хватает детей, Гретель делает служанкой, а Гензеля сажает к клетку и начинает его откармливать, чтобы в последствии съесть. мальчик идет на хитрость. Чтобы проверить насколько он толст, полуслепая ведьма ощупывает его палец. мальчик же протягивает каждый раз кость, которую она принимает за руку. Когда ведьма понимает, что ее обманывают, то хочет немедленно скушать мальчика. Она приказывает Гретель растопить печь и залезть в нее, чтобы проверить насколько она горяча. Девочка говорить, что она еще слишком мала для этого и просит ведьму, чтобы та показала ей как это делается. Когда ведьма открывает печь, Гретель толкает ее туда и закрывает дверцу. Ведьма сгорает там, а дети берут сокровища из ее дома и находят путь к отцу. Мама их уже умерла. И они живут долго и счастливо.

| Hansel and Gretel | |

|---|---|

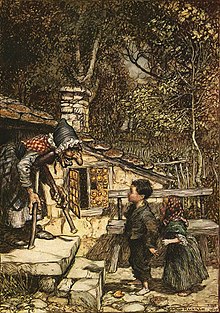

The witch welcomes Hansel and Gretel into her hut. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1909. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Hansel and Gretel |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 327A |

| Region | German |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm |

«Hansel and Gretel» (; German: Hänsel und Gretel [ˈhɛnzl̩ ʔʊnt ˈɡʁeːtl̩])[a] is a German fairy tale collected by the German Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm’s Fairy Tales (KHM 15).[1][2] It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel and Gretel are a brother and sister abandoned in a forest, where they fall into the hands of a witch who lives in a house made of gingerbread, cake, and candy. The cannibalistic witch intends to fatten Hansel before eventually eating him, but Gretel pushes the witch into her own oven and kills her. The two children then escape with their lives and return home with the witch’s treasure.[3]

«Hansel and Gretel» is a tale of Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 327A.[4][5] It also includes an episode of type 1121 (‘Burning the Witch in Her Own Oven’).[2][6] The story is set in medieval Germany. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck.[7][8]

Origin[edit]

Sources[edit]

Although Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm credited «various tales from Hesse» (the region where they lived) as their source, scholars have argued that the brothers heard the story in 1809 from the family of Wilhelm’s friend and future wife, Dortchen Wild, and partly from other sources.[9] A handwritten note in the Grimms’ personal copy of the first edition reveals that in 1813 Wild contributed to the children’s verse answer to the witch, «The wind, the wind,/ The heavenly child,» which rhymes in German: «Der Wind, der Wind,/ Das himmlische Kind.»[2]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale emerged in the Late Middle Ages Germany (1250–1500). Shortly after this period, close written variants like Martin Montanus’ Garten Gesellschaft (1590) began to appear.[3] Scholar Christine Goldberg argues that the episode of the paths marked with stones and crumbs, already found in the French «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697), represents «an elaboration of the motif of the thread that Ariadne gives Theseus to use to get out of the Minoan labyrinth».[10] A house made of confectionery is also found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[7]

Editions[edit]

From the pre-publication manuscript of 1810 (Das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen) to the sixth edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm’s Fairy Tales) in 1850, the Brothers Grimm made several alterations to the story, which progressively gained in length, psychological motivation, and visual imagery,[11] but also became more Christian in tone, shifting the blame for abandonment from a mother to a stepmother associated with the witch.[1][3]

In the original edition of the tale, the woodcutter’s wife is the children’s biological mother,[12] but she was also called «stepmother» from the 4th edition (1840).[5][13] The Brothers Grimm indeed introduced the word «stepmother», but retained «mother» in some passages. Even their final version in the 7th edition (1857) remains unclear about her role, for it refers to the woodcutter’s wife twice as «the mother» and once as «the stepmother».[2]

The sequence where the duck helps them across the river is also a later addition. In some later versions, the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story.[14] In the 1810 pre-publication manuscript, the children were called «Little Brother» and «Little Sister», then named Hänsel and Gretel in the first edition (1812).[11] Wilhelm Grimm also adulterated the text with Alsatian dialects, «re-appropriated» from August Ströber’s Alsatian version (1842) in order to give the tale a more «folksy» tone.[5][b]

Goldberg notes that although «there is no doubt that the Grimms’ Hänsel und Gretel was pieced together, it was, however, pieced together from traditional elements,» and its previous narrators themselves had been «piecing this little tale together with other traditional motifs for centuries.»[6] For instance, the duck helping the children cross the river may be the remnant of an old traditional motif in the folktale complex that was reintroduced by the Grimms in later editions.[6]

Plot[edit]

Hansel and Gretel are the young children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter’s second wife tells the woodcutter to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves, so that she and her husband do not starve to death. The woodcutter opposes the plan, but his wife claims that maybe a stranger will take the children in and provide for them, which the woodcutter and she simply cannot do. With the scheme seemingly justified, the woodcutter reluctantly is forced to submit to it. They are unaware that in the children’s bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the family walk deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, the children wait for the moon to rise and then follow the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother’s rage. Once again, provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children further into the woods and leave them there. Hansel and Gretel attempt to gather more pebbles, but find the front door locked.

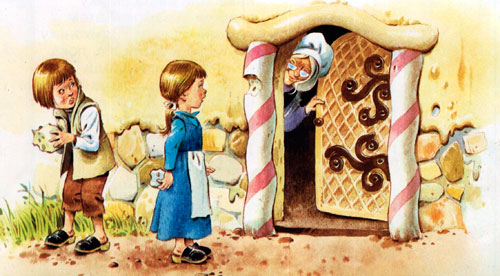

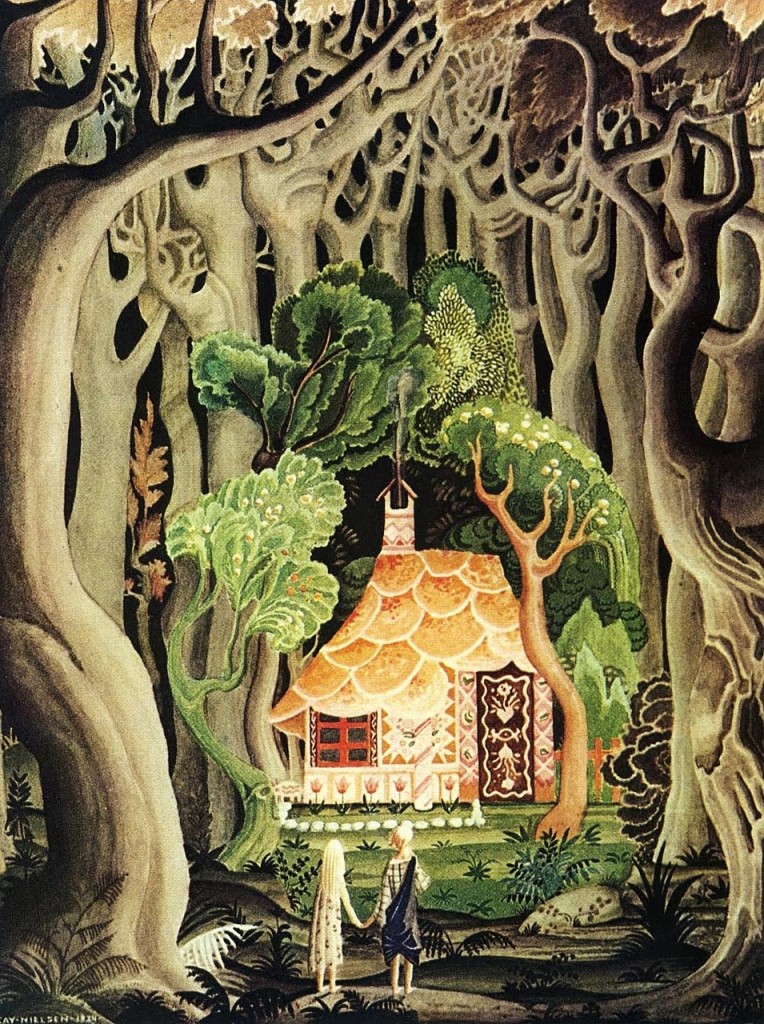

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs for them to follow to return back home. However, after they are once again abandoned, they find that the birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, and discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cookies, cakes, and candy, with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the house, when the door opens and a «very old woman» emerges and lures the children inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. They enter without realizing that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to waylay children to cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch locks Hansel in an iron cage in the garden and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but serves Gretel nothing but crab shells. The witch then tries to touch Hansel’s finger to see how fat he has become, but Hansel cleverly offers a thin bone he found in the cage. As the witch’s eyes are too weak to notice the deception, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel, «be he fat or lean«.

She prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel, too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and asks her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch’s intent, pretends she does not understand what the witch means. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel instantly shoves her into the hot oven, slams and bolts the door shut, and leaves «the ungodly witch to be burned in ashes«. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure, including precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home. A swan ferries them across an expanse of water, and at home they find only their father; his wife having died from an unknown cause. Their father had spent all his days lamenting the loss of his children, and is delighted to see them safe and sound. With the witch’s wealth, they all live happily ever after.

Variants[edit]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate that «Hansel and Gretel» belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen.[7]

ATU 327A tales[edit]

«Hansel and Gretel» is the prototype for the fairy tales of the type Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) 327A. In particular, Gretel’s pretense of not understanding how to test the oven («Show Me How») is characteristic of 327A, although it also appears traditionally in other sub-types of ATU 327.[15] As argued by Stith Thompson, the simplicity of the tale may explain its spread into several traditions all over the world.[16]

A closely similar version is «Finette Cendron», published by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in 1697, which depicts an impoverished king and queen deliberately losing their three daughters three times in the wilderness. The cleverest of the girls, Finette, initially manages to bring them home with a trail of thread, and then a trail of ashes, but her peas are eaten by pigeons during the third journey. The little girls then go to the mansion of a hag, who lives with her husband the ogre. Finette heats the oven and asks the ogre to test it with his tongue, so that he falls in and is incinerated. Thereafter, Finette cuts off the hag’s head. The sisters remain in the ogre’s house, and the rest of the tale relates the story of «Cinderella».[7][10]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with eating and with hurting children: The mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, and the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[17]

In a variant from Flanders, The Sugar-Candy House, siblings Jan and Jannette get lost in the woods and sight a hut made of confectionary in the distance. When they approach, a giant wolf named Garon jumps out of the window and chases them to a river bank. Sister and brother ask a pair of ducks to help them cross the river and escape the wolf. Garon threatens the ducks to carry him over, to no avail; he then tries to cross by swimming. He sinks and surfaces three times, but disappears in the water on the fourth try. The story seems to contain the «child/wind» rhyming scheme of the German tale.[18]

In a French fairy tale, La Cabane au Toit de Fromage («The Hut with the Roof made of Cheese»), the brother is the hero who deceives the witch and locks her up in the oven.[19]

In the first Puerto Rican variant of «The Orphaned Children,» the brother pushes the witch into the oven.[20]

Other folk tales of ATU 327A type include the French «The Lost Children», published by Antoinette Bon in 1887,[21][22] or the Moravian «Old Gruel», edited by Maria Kosch in 1899.[22]

The Children and the Ogre (ATU 327)[edit]

Structural comparisons can also be made with other tales of ATU 327 type («The Children and the Ogre»), which is not a simple fairy tale type but rather a «folktale complex with interconnected subdivisions» depicting a child (or children) falling under the power of an ogre, then escaping by their clever tricks.[23]

In ATU 327B («The Brothers and the Ogre»), a group of siblings come to an ogre’s house who intends to kill them in their beds, but the youngest of the children exchanges the visitors with the ogre’s offspring, and the villain kills his own children by mistake. They are chased by the ogre, but the siblings eventually manage to come back home safely.[24] Stith Thompson points the great similarity of the tales types ATU 327A and ATU 327B that «it is quite impossible to disentangle the two tales».[25]

ATU 327C («The Devil [Witch] Carries the Hero Home in a Sack») depicts a witch or an ogre catching a boy in a sack. As the villain’s daughter is preparing to kill him, the boy asks her to show him how he should arrange himself; when she does so, he kills her. Later on, he kills the witch and goes back home with her treasure. In ATU 327D («The Kiddlekaddlekar»), children are discovered by an ogre in his house. He intends to hang them, but the girl pretends not to understand how to do it, so the ogre hangs himself to show her. He promises his kiddlekaddlekar (a magic cart) and treasure in exchange for his liberation; they set him free, but the ogre chases them. The children eventually manage to kill him and escape safely. In ATU 327F («The Witch and the Fisher Boy»), a witch lures a boy and catches him. When the witch’s daughter tries to bake the child, he pushes her into the oven. The witch then returns home and eats her own daughter. She eventually tries to fell the tree in which the boy is hiding, but birds fly away with him.[24]

Further comparisons[edit]

The initial episode, which depicts children deliberately lost in the forest by their unloving parents, can be compared with many previous stories: Montanus’s «The Little Earth-Cow» (1557), Basile’s «Ninnillo and Nennella» (1635), Madame d’Aulnoy’s «Finette Cendron» (1697), or Perrault’s «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697). The motif of the trail that fails to lead the protagonists back home is also common to «Ninnillo and Nennella», «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb»,[26] and the Brothers Grimm identified the latter as a parallel story.[27]

Finally, ATU 327 tales share a similar structure with ATU 313 («Sweetheart Roland», «The Foundling», «Okerlo») in that one or more protagonists (specifically children in ATU 327) come into the domain of a malevolent supernatural figure and escape from it.[24] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, commenting on his reconstructed proto-form of the tale (Johnnie and Grizzle), noticed the «contamination» of the tale with the story of The Master Maid, later classified as ATU 313.[28] ATU 327A tales are also often combined with stories of ATU 450 («Little Brother and Sister»), in which children run away from an abusive stepmother.[3]

Analysis[edit]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale celebrates the symbolic order of the patriarchal home, seen as a haven protected from the dangerous characters that threaten the lives of children outside, while it systematically denigrates the adult female characters, which are seemingly intertwined between each other.[8][29] The mother or stepmother indeed dies just after the children kill the witch, suggesting that they may metaphorically be the same woman.[30] Zipes also argues that the importance of the tale in the European oral and literary tradition may be explained by the theme of child abandonment and abuse. Due to famines and lack of birth control, it was common in medieval Europe to abandon unwanted children in front of churches or in the forest. The death of the mother during childbirth sometimes led to tensions after remarriage, and Zipes proposes that it may have played a role in the emergence of the motif of the wicked stepmother.[29]

Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age, rite of passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[31][32] Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim argues that the main motif is about dependence, oral greed, and destructive desires that children must learn to overcome, after they arrive home «purged of their oral fixations». Others have stressed the satisfying psychological effects of the children vanquishing the witch or realizing the death of their wicked stepmother.[8]

Cultural legacy[edit]

Stage and musical theater[edit]

The fairy tale enjoyed a multitude of adaptations for the stage, among them the opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck—one of the most performed operas.[33] It is principally based upon the Grimm’s version, although it omits the deliberate abandonment of the children.[7][8]

A contemporary reimagining of the story, Mátti Kovler’s musical fairytale Ami & Tami, was produced in Israel and the United States and subsequently released as a symphonic album.[34][35]

Literature[edit]

Several writers have drawn inspiration from the tale, such as Robert Coover in «The Gingerbread House» (Pricks and Descants, 1970), Anne Sexton in Transformations (1971), Garrison Keillor in «My Stepmother, Myself» in «Happy to Be Here» (1982), and Emma Donoghue in «A Tale of the Cottage» (Kissing the Witch, 1997).[8] Adam Gidwitz’s 2010 children’s book A Tale Dark & Grimm and its sequels In a Glass Grimmly (2012), and The Grimm Conclusion (2013) are loosely based on the tale and show the siblings meeting characters from other fairy tales.

Terry Pratchett mentions gingerbread cottages in several of his books, mainly where a witch had turned wicked and ‘started to cackle’, with the gingerbread house being a stage in a person’s increasing levels of insanity. In The Light Fantastic the wizard Rincewind and Twoflower are led by a gnome into one such building after the death of the witch and warned to be careful of the doormat, as it is made of candy floss.

Film[edit]

- Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, a 1954 stop-motion animated theatrical feature film directed by John Paul and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

- A 1983 episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre starred Ricky Schroder as Hansel and Joan Collins as the stepmother/witch.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1983 TV special directed by Tim Burton.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1987 American/Israeli musical film directed by Len Talan with David Warner, Cloris Leachman, Hugh Pollard and Nicola Stapleton. Part of the 1980s film series Cannon Movie Tales.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1994 horror film Wes Craven’s New Nightmare for its climax.

- «Hänsel und Gretel»[36] by 2012 German Broadcaster RBB released as part of its series Der rbb macht Familienzeit.

- Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013) by Tommy Wirkola with Jeremy Renner and Gemma Arterton, (USA, Germany). The film follows the adventures of Hansel & Gretel who became adults.

- Gretel & Hansel, a 2020 American horror film directed by Oz Perkins in which Gretel is a teenager while Hansel is still a little boy.

- Secret Magic Control Agency (2021) is an animated retelling of the fairy tale by incorporating comedy and family genres[37]

Computer programming[edit]

Hansel and Gretel’s trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element «breadcrumbs» that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[38]

Video games[edit]

- Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle (1995) by Terraglyph Interactive Studios is an adventure and hidden object game. The player controls Hansel, tasked with finding Prin, a forest imp, who holds the key to saving Gretel from the witch.[39]

- Gretel and Hansel (2009) by Mako Pudding is a browser adventure game. Popular on Newgrounds for its gruesome reimagining of the story, it features hand painted watercolor backgrounds and characters animated by Flash.[40]

- Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition (2013) by Eipix Entertainment is a HOPA (hidden object puzzle adventure) game. The player, as Hansel and Gretel’s mother, searches the witch’s lair for clues.[41]

- In the online role-playing game Poptropica, the Candy Crazed mini-quest (2021) includes a short retelling of the story. The player is summoned to the witch’s castle to free the children, who have been imprisoned after eating some of the candy residents.[42]

See also[edit]

- «Brother and Sister»

- «Esben and the Witch»

- Gingerbread house

- «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (French fairy tale by Charles Perrault)

- «The Hut in the Forest»

- «Jorinde and Joringel»

- «Molly Whuppie»

- «Thirteenth»

- The Truth About Hansel and Gretel

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ In German, the names are diminutives of Johannes (John) and Margarete (Margaret).

- ^ Zipes words it as «re-appropriated» because Ströber’s Alsatian informant who provided «Das Eierkuchenhäuslein (The Little House of Pancakes)» had probably read Grimm’s «Hansel and Gretel».

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225.

- ^ a b c d Ashliman, D. L. (2011). «Hansel and Gretel». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ a b c d Zipes 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 440.

- ^ a b c Zipes 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2000, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e Wanning Harries 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236; Goldberg 2000, p. 42; Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225; Zipes 2013, p. 121

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 439.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Zipes (2014) tr. «Hansel and Gretel (The Complete First Edition)», pp. 43–48; Zipes (2013) tr., pp. 122–126; Brüder Grimm, ed. (1812). «15. Hänsel und Grethel» . Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (in German). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Realschulbuchhandlung. pp. 49–58 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 438: «in the fourth edition, the woodcutter’s wife (who had been the children’s own mother) was first called a stepmother.»

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 45

- ^ Goldberg 2008, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ^ Bosschère, Jean de. Folk tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead. 1918. pp. 91-94.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. Contes et légendes. 1ere partie. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company. 1895. pp. 64-67.

- ^ Ocasio, Rafael (2021). Folk stories from the hills of Puerto Rico = Cuentos folklóricos de las montañas de Puerto Rico. New Brunswick. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1978823013.

- ^ Delarue 1956, p. 365.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Thompson 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ^ Jacobs 1916, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ^ Vajda 2010

- ^ Vajda 2011

- ^ Upton, George Putnam (1897). The Standard Operas (Google book) (12th ed.). Chicago: McClurg. pp. 125–129. ISBN 1-60303-367-X. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ «Composer Matti Kovler realizes dream of reviving fairy-tale opera in Boston». The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Schwartz, Penny. «Boston goes into the woods with Israeli opera ‘Ami and Tami’«. Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ «Hänsel und Gretel | Der rbb macht Familienzeit — YouTube». www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2019-11-01). «Wizart Reveals ‘Hansel and Gretel’ Poster Art Ahead of AFM». Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Mark Levene (18 October 2010). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 221. ISBN 978-0470526842. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ «Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle for Windows (1995)».

- ^ «Gretel and Hansel».

- ^ «Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac & PC! Big Fish is the #1 place for the best FREE games».

- ^ «The Candy Crazed Mini Quest is NOW LIVE!! 🍬🏰 | poptropica».

Bibliography[edit]

- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Goldberg, Christine (2000). «Gretel’s Duck: The Escape from the Ogre in AaTh 327». Fabula. 41 (1–2): 42–51. doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.42. S2CID 163082145.

- Goldberg, Christine (2008). «Hansel and Gretel». In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04947-7.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). European Folk and Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 9780804425650.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03537-9.

- Vajda, Edward (2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World’s Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

- Wanning Harries, Elizabeth (2000). «Hansel and Gretel». In Zipel, Jack (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968982-8.

- Zipes, Jack (2013). «Abandoned Children ATU 327A―Hansel and Gretel». The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-624-66034-4.

Primary sources[edit]

- Zipes, Jack (2014). «Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)». The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (orig. eds.); Andrea Dezsö (illustr.) (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 43–48. ISBN 978-0-691-17322-1.

Further reading[edit]

- de Blécourt, Willem. «On the Origin of Hänsel und Gretel». In: Fabula 49, 1-2 (2008): 30-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/FABL.2008.004

- Böhm-Korff, Regina (1991). Deutung und Bedeutung von «Hänsel und Gretel»: eine Fallstudie (in German). P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-43703-2.

- Freudenburg, Rachel. «Illustrating Childhood—»Hansel and Gretel».» Marvels & Tales 12, no. 2 (1998): 263-318. www.jstor.org/stable/41388498.

- Gaudreau, Jean. «Handicap et sentiment d’abandon dans trois contes de fées: Le petit Poucet, Hansel et Gretel, Jean-mon-Hérisson». In: Enfance, tome 43, n°4, 1990. pp. 395–404. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/enfan.1990.1957]; www.persee.fr/doc/enfan_0013-7545_1990_num_43_4_1957

- Harshbarger, Scott. «Grimm and Grimmer: “Hansel and Gretel” and Fairy Tale Nationalism.» Style 47, no. 4 (2013): 490-508. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.47.4.490.

- Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). Hänsel und Gretel: das Märchen in Kunst, Musik, Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen (in German). Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0469-8.

- Taggart, James M. «»Hansel and Gretel» in Spain and Mexico.» The Journal of American Folklore 99, no. 394 (1986): 435-60. doi:10.2307/540047.

- Zipes, Jack (1997). «The rationalization of abandonment and abuse in fairy tales: The case of Hansel and Gretel». Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales, Children, and the Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25296-0.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Hansel and Gretel at Project Gutenberg

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including Hansel and Gretel at Standard Ebooks

- Hansel and Gretel fairy tale

- Original versions and psychological analysis of classic fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel

- The Story of Hansel and Gretel

- Collaboratively illustrated story on Project Bookses

- https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/hansel_and_gretel

| Hansel and Gretel | |

|---|---|

The witch welcomes Hansel and Gretel into her hut. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1909. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Hansel and Gretel |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 327A |

| Region | German |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm |

«Hansel and Gretel» (; German: Hänsel und Gretel [ˈhɛnzl̩ ʔʊnt ˈɡʁeːtl̩])[a] is a German fairy tale collected by the German Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm’s Fairy Tales (KHM 15).[1][2] It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel and Gretel are a brother and sister abandoned in a forest, where they fall into the hands of a witch who lives in a house made of gingerbread, cake, and candy. The cannibalistic witch intends to fatten Hansel before eventually eating him, but Gretel pushes the witch into her own oven and kills her. The two children then escape with their lives and return home with the witch’s treasure.[3]

«Hansel and Gretel» is a tale of Aarne–Thompson–Uther type 327A.[4][5] It also includes an episode of type 1121 (‘Burning the Witch in Her Own Oven’).[2][6] The story is set in medieval Germany. The tale has been adapted to various media, most notably the opera Hänsel und Gretel (1893) by Engelbert Humperdinck.[7][8]

Origin[edit]

Sources[edit]

Although Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm credited «various tales from Hesse» (the region where they lived) as their source, scholars have argued that the brothers heard the story in 1809 from the family of Wilhelm’s friend and future wife, Dortchen Wild, and partly from other sources.[9] A handwritten note in the Grimms’ personal copy of the first edition reveals that in 1813 Wild contributed to the children’s verse answer to the witch, «The wind, the wind,/ The heavenly child,» which rhymes in German: «Der Wind, der Wind,/ Das himmlische Kind.»[2]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale emerged in the Late Middle Ages Germany (1250–1500). Shortly after this period, close written variants like Martin Montanus’ Garten Gesellschaft (1590) began to appear.[3] Scholar Christine Goldberg argues that the episode of the paths marked with stones and crumbs, already found in the French «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697), represents «an elaboration of the motif of the thread that Ariadne gives Theseus to use to get out of the Minoan labyrinth».[10] A house made of confectionery is also found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[7]

Editions[edit]

From the pre-publication manuscript of 1810 (Das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen) to the sixth edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm’s Fairy Tales) in 1850, the Brothers Grimm made several alterations to the story, which progressively gained in length, psychological motivation, and visual imagery,[11] but also became more Christian in tone, shifting the blame for abandonment from a mother to a stepmother associated with the witch.[1][3]

In the original edition of the tale, the woodcutter’s wife is the children’s biological mother,[12] but she was also called «stepmother» from the 4th edition (1840).[5][13] The Brothers Grimm indeed introduced the word «stepmother», but retained «mother» in some passages. Even their final version in the 7th edition (1857) remains unclear about her role, for it refers to the woodcutter’s wife twice as «the mother» and once as «the stepmother».[2]

The sequence where the duck helps them across the river is also a later addition. In some later versions, the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story.[14] In the 1810 pre-publication manuscript, the children were called «Little Brother» and «Little Sister», then named Hänsel and Gretel in the first edition (1812).[11] Wilhelm Grimm also adulterated the text with Alsatian dialects, «re-appropriated» from August Ströber’s Alsatian version (1842) in order to give the tale a more «folksy» tone.[5][b]

Goldberg notes that although «there is no doubt that the Grimms’ Hänsel und Gretel was pieced together, it was, however, pieced together from traditional elements,» and its previous narrators themselves had been «piecing this little tale together with other traditional motifs for centuries.»[6] For instance, the duck helping the children cross the river may be the remnant of an old traditional motif in the folktale complex that was reintroduced by the Grimms in later editions.[6]

Plot[edit]

Hansel and Gretel are the young children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter’s second wife tells the woodcutter to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves, so that she and her husband do not starve to death. The woodcutter opposes the plan, but his wife claims that maybe a stranger will take the children in and provide for them, which the woodcutter and she simply cannot do. With the scheme seemingly justified, the woodcutter reluctantly is forced to submit to it. They are unaware that in the children’s bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the family walk deep into the woods and Hansel lays a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, the children wait for the moon to rise and then follow the pebbles back home. They return home safely, much to their stepmother’s rage. Once again, provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children further into the woods and leave them there. Hansel and Gretel attempt to gather more pebbles, but find the front door locked.

The following morning, the family treks into the woods. Hansel takes a slice of bread and leaves a trail of bread crumbs for them to follow to return back home. However, after they are once again abandoned, they find that the birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After days of wandering, they follow a beautiful white bird to a clearing in the woods, and discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cookies, cakes, and candy, with window panes of clear sugar. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the rooftop of the house, when the door opens and a «very old woman» emerges and lures the children inside with the promise of soft beds and delicious food. They enter without realizing that their hostess is a bloodthirsty witch who built the gingerbread house to waylay children to cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch locks Hansel in an iron cage in the garden and forces Gretel into becoming a slave. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but serves Gretel nothing but crab shells. The witch then tries to touch Hansel’s finger to see how fat he has become, but Hansel cleverly offers a thin bone he found in the cage. As the witch’s eyes are too weak to notice the deception, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin to eat. After weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel, «be he fat or lean«.

She prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel, too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and asks her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch’s intent, pretends she does not understand what the witch means. Infuriated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel instantly shoves her into the hot oven, slams and bolts the door shut, and leaves «the ungodly witch to be burned in ashes«. Gretel frees Hansel from the cage and the pair discover a vase full of treasure, including precious stones. Putting the jewels into their clothing, the children set off for home. A swan ferries them across an expanse of water, and at home they find only their father; his wife having died from an unknown cause. Their father had spent all his days lamenting the loss of his children, and is delighted to see them safe and sound. With the witch’s wealth, they all live happily ever after.

Variants[edit]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate that «Hansel and Gretel» belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen.[7]

ATU 327A tales[edit]

«Hansel and Gretel» is the prototype for the fairy tales of the type Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) 327A. In particular, Gretel’s pretense of not understanding how to test the oven («Show Me How») is characteristic of 327A, although it also appears traditionally in other sub-types of ATU 327.[15] As argued by Stith Thompson, the simplicity of the tale may explain its spread into several traditions all over the world.[16]

A closely similar version is «Finette Cendron», published by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in 1697, which depicts an impoverished king and queen deliberately losing their three daughters three times in the wilderness. The cleverest of the girls, Finette, initially manages to bring them home with a trail of thread, and then a trail of ashes, but her peas are eaten by pigeons during the third journey. The little girls then go to the mansion of a hag, who lives with her husband the ogre. Finette heats the oven and asks the ogre to test it with his tongue, so that he falls in and is incinerated. Thereafter, Finette cuts off the hag’s head. The sisters remain in the ogre’s house, and the rest of the tale relates the story of «Cinderella».[7][10]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with eating and with hurting children: The mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, and the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[17]

In a variant from Flanders, The Sugar-Candy House, siblings Jan and Jannette get lost in the woods and sight a hut made of confectionary in the distance. When they approach, a giant wolf named Garon jumps out of the window and chases them to a river bank. Sister and brother ask a pair of ducks to help them cross the river and escape the wolf. Garon threatens the ducks to carry him over, to no avail; he then tries to cross by swimming. He sinks and surfaces three times, but disappears in the water on the fourth try. The story seems to contain the «child/wind» rhyming scheme of the German tale.[18]

In a French fairy tale, La Cabane au Toit de Fromage («The Hut with the Roof made of Cheese»), the brother is the hero who deceives the witch and locks her up in the oven.[19]

In the first Puerto Rican variant of «The Orphaned Children,» the brother pushes the witch into the oven.[20]

Other folk tales of ATU 327A type include the French «The Lost Children», published by Antoinette Bon in 1887,[21][22] or the Moravian «Old Gruel», edited by Maria Kosch in 1899.[22]

The Children and the Ogre (ATU 327)[edit]

Structural comparisons can also be made with other tales of ATU 327 type («The Children and the Ogre»), which is not a simple fairy tale type but rather a «folktale complex with interconnected subdivisions» depicting a child (or children) falling under the power of an ogre, then escaping by their clever tricks.[23]

In ATU 327B («The Brothers and the Ogre»), a group of siblings come to an ogre’s house who intends to kill them in their beds, but the youngest of the children exchanges the visitors with the ogre’s offspring, and the villain kills his own children by mistake. They are chased by the ogre, but the siblings eventually manage to come back home safely.[24] Stith Thompson points the great similarity of the tales types ATU 327A and ATU 327B that «it is quite impossible to disentangle the two tales».[25]

ATU 327C («The Devil [Witch] Carries the Hero Home in a Sack») depicts a witch or an ogre catching a boy in a sack. As the villain’s daughter is preparing to kill him, the boy asks her to show him how he should arrange himself; when she does so, he kills her. Later on, he kills the witch and goes back home with her treasure. In ATU 327D («The Kiddlekaddlekar»), children are discovered by an ogre in his house. He intends to hang them, but the girl pretends not to understand how to do it, so the ogre hangs himself to show her. He promises his kiddlekaddlekar (a magic cart) and treasure in exchange for his liberation; they set him free, but the ogre chases them. The children eventually manage to kill him and escape safely. In ATU 327F («The Witch and the Fisher Boy»), a witch lures a boy and catches him. When the witch’s daughter tries to bake the child, he pushes her into the oven. The witch then returns home and eats her own daughter. She eventually tries to fell the tree in which the boy is hiding, but birds fly away with him.[24]

Further comparisons[edit]

The initial episode, which depicts children deliberately lost in the forest by their unloving parents, can be compared with many previous stories: Montanus’s «The Little Earth-Cow» (1557), Basile’s «Ninnillo and Nennella» (1635), Madame d’Aulnoy’s «Finette Cendron» (1697), or Perrault’s «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (1697). The motif of the trail that fails to lead the protagonists back home is also common to «Ninnillo and Nennella», «Finette Cendron» and «Hop-o’-My-Thumb»,[26] and the Brothers Grimm identified the latter as a parallel story.[27]

Finally, ATU 327 tales share a similar structure with ATU 313 («Sweetheart Roland», «The Foundling», «Okerlo») in that one or more protagonists (specifically children in ATU 327) come into the domain of a malevolent supernatural figure and escape from it.[24] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, commenting on his reconstructed proto-form of the tale (Johnnie and Grizzle), noticed the «contamination» of the tale with the story of The Master Maid, later classified as ATU 313.[28] ATU 327A tales are also often combined with stories of ATU 450 («Little Brother and Sister»), in which children run away from an abusive stepmother.[3]

Analysis[edit]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale celebrates the symbolic order of the patriarchal home, seen as a haven protected from the dangerous characters that threaten the lives of children outside, while it systematically denigrates the adult female characters, which are seemingly intertwined between each other.[8][29] The mother or stepmother indeed dies just after the children kill the witch, suggesting that they may metaphorically be the same woman.[30] Zipes also argues that the importance of the tale in the European oral and literary tradition may be explained by the theme of child abandonment and abuse. Due to famines and lack of birth control, it was common in medieval Europe to abandon unwanted children in front of churches or in the forest. The death of the mother during childbirth sometimes led to tensions after remarriage, and Zipes proposes that it may have played a role in the emergence of the motif of the wicked stepmother.[29]

Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age, rite of passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[31][32] Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim argues that the main motif is about dependence, oral greed, and destructive desires that children must learn to overcome, after they arrive home «purged of their oral fixations». Others have stressed the satisfying psychological effects of the children vanquishing the witch or realizing the death of their wicked stepmother.[8]

Cultural legacy[edit]

Stage and musical theater[edit]

The fairy tale enjoyed a multitude of adaptations for the stage, among them the opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck—one of the most performed operas.[33] It is principally based upon the Grimm’s version, although it omits the deliberate abandonment of the children.[7][8]

A contemporary reimagining of the story, Mátti Kovler’s musical fairytale Ami & Tami, was produced in Israel and the United States and subsequently released as a symphonic album.[34][35]

Literature[edit]

Several writers have drawn inspiration from the tale, such as Robert Coover in «The Gingerbread House» (Pricks and Descants, 1970), Anne Sexton in Transformations (1971), Garrison Keillor in «My Stepmother, Myself» in «Happy to Be Here» (1982), and Emma Donoghue in «A Tale of the Cottage» (Kissing the Witch, 1997).[8] Adam Gidwitz’s 2010 children’s book A Tale Dark & Grimm and its sequels In a Glass Grimmly (2012), and The Grimm Conclusion (2013) are loosely based on the tale and show the siblings meeting characters from other fairy tales.

Terry Pratchett mentions gingerbread cottages in several of his books, mainly where a witch had turned wicked and ‘started to cackle’, with the gingerbread house being a stage in a person’s increasing levels of insanity. In The Light Fantastic the wizard Rincewind and Twoflower are led by a gnome into one such building after the death of the witch and warned to be careful of the doormat, as it is made of candy floss.

Film[edit]

- Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, a 1954 stop-motion animated theatrical feature film directed by John Paul and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

- A 1983 episode of Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre starred Ricky Schroder as Hansel and Joan Collins as the stepmother/witch.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1983 TV special directed by Tim Burton.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1987 American/Israeli musical film directed by Len Talan with David Warner, Cloris Leachman, Hugh Pollard and Nicola Stapleton. Part of the 1980s film series Cannon Movie Tales.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1994 horror film Wes Craven’s New Nightmare for its climax.

- «Hänsel und Gretel»[36] by 2012 German Broadcaster RBB released as part of its series Der rbb macht Familienzeit.

- Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013) by Tommy Wirkola with Jeremy Renner and Gemma Arterton, (USA, Germany). The film follows the adventures of Hansel & Gretel who became adults.

- Gretel & Hansel, a 2020 American horror film directed by Oz Perkins in which Gretel is a teenager while Hansel is still a little boy.

- Secret Magic Control Agency (2021) is an animated retelling of the fairy tale by incorporating comedy and family genres[37]

Computer programming[edit]

Hansel and Gretel’s trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element «breadcrumbs» that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[38]

Video games[edit]

- Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle (1995) by Terraglyph Interactive Studios is an adventure and hidden object game. The player controls Hansel, tasked with finding Prin, a forest imp, who holds the key to saving Gretel from the witch.[39]

- Gretel and Hansel (2009) by Mako Pudding is a browser adventure game. Popular on Newgrounds for its gruesome reimagining of the story, it features hand painted watercolor backgrounds and characters animated by Flash.[40]

- Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition (2013) by Eipix Entertainment is a HOPA (hidden object puzzle adventure) game. The player, as Hansel and Gretel’s mother, searches the witch’s lair for clues.[41]

- In the online role-playing game Poptropica, the Candy Crazed mini-quest (2021) includes a short retelling of the story. The player is summoned to the witch’s castle to free the children, who have been imprisoned after eating some of the candy residents.[42]

See also[edit]

- «Brother and Sister»

- «Esben and the Witch»

- Gingerbread house

- «Hop-o’-My-Thumb» (French fairy tale by Charles Perrault)

- «The Hut in the Forest»

- «Jorinde and Joringel»

- «Molly Whuppie»

- «Thirteenth»

- The Truth About Hansel and Gretel

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ In German, the names are diminutives of Johannes (John) and Margarete (Margaret).

- ^ Zipes words it as «re-appropriated» because Ströber’s Alsatian informant who provided «Das Eierkuchenhäuslein (The Little House of Pancakes)» had probably read Grimm’s «Hansel and Gretel».

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225.

- ^ a b c d Ashliman, D. L. (2011). «Hansel and Gretel». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ a b c d Zipes 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 440.

- ^ a b c Zipes 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2000, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e Wanning Harries 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236; Goldberg 2000, p. 42; Wanning Harries 2000, p. 225; Zipes 2013, p. 121

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 439.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Zipes (2014) tr. «Hansel and Gretel (The Complete First Edition)», pp. 43–48; Zipes (2013) tr., pp. 122–126; Brüder Grimm, ed. (1812). «15. Hänsel und Grethel» . Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (in German). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Realschulbuchhandlung. pp. 49–58 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 438: «in the fourth edition, the woodcutter’s wife (who had been the children’s own mother) was first called a stepmother.»

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 45

- ^ Goldberg 2008, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ^ Bosschère, Jean de. Folk tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead. 1918. pp. 91-94.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. Contes et légendes. 1ere partie. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company. 1895. pp. 64-67.

- ^ Ocasio, Rafael (2021). Folk stories from the hills of Puerto Rico = Cuentos folklóricos de las montañas de Puerto Rico. New Brunswick. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1978823013.

- ^ Delarue 1956, p. 365.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Thompson 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ^ Jacobs 1916, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ^ Vajda 2010

- ^ Vajda 2011

- ^ Upton, George Putnam (1897). The Standard Operas (Google book) (12th ed.). Chicago: McClurg. pp. 125–129. ISBN 1-60303-367-X. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ «Composer Matti Kovler realizes dream of reviving fairy-tale opera in Boston». The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Schwartz, Penny. «Boston goes into the woods with Israeli opera ‘Ami and Tami’«. Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ «Hänsel und Gretel | Der rbb macht Familienzeit — YouTube». www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2019-11-01). «Wizart Reveals ‘Hansel and Gretel’ Poster Art Ahead of AFM». Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Mark Levene (18 October 2010). An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 221. ISBN 978-0470526842. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ «Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle for Windows (1995)».

- ^ «Gretel and Hansel».

- ^ «Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector’s Edition for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac & PC! Big Fish is the #1 place for the best FREE games».

- ^ «The Candy Crazed Mini Quest is NOW LIVE!! 🍬🏰 | poptropica».

Bibliography[edit]

- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Goldberg, Christine (2000). «Gretel’s Duck: The Escape from the Ogre in AaTh 327». Fabula. 41 (1–2): 42–51. doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.42. S2CID 163082145.

- Goldberg, Christine (2008). «Hansel and Gretel». In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04947-7.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). European Folk and Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam’s sons.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 9780804425650.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03537-9.

- Vajda, Edward (2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World’s Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

- Wanning Harries, Elizabeth (2000). «Hansel and Gretel». In Zipel, Jack (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968982-8.

- Zipes, Jack (2013). «Abandoned Children ATU 327A―Hansel and Gretel». The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-624-66034-4.

Primary sources[edit]

- Zipes, Jack (2014). «Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)». The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (orig. eds.); Andrea Dezsö (illustr.) (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 43–48. ISBN 978-0-691-17322-1.

Further reading[edit]

- de Blécourt, Willem. «On the Origin of Hänsel und Gretel». In: Fabula 49, 1-2 (2008): 30-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/FABL.2008.004

- Böhm-Korff, Regina (1991). Deutung und Bedeutung von «Hänsel und Gretel»: eine Fallstudie (in German). P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-43703-2.

- Freudenburg, Rachel. «Illustrating Childhood—»Hansel and Gretel».» Marvels & Tales 12, no. 2 (1998): 263-318. www.jstor.org/stable/41388498.

- Gaudreau, Jean. «Handicap et sentiment d’abandon dans trois contes de fées: Le petit Poucet, Hansel et Gretel, Jean-mon-Hérisson». In: Enfance, tome 43, n°4, 1990. pp. 395–404. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/enfan.1990.1957]; www.persee.fr/doc/enfan_0013-7545_1990_num_43_4_1957

- Harshbarger, Scott. «Grimm and Grimmer: “Hansel and Gretel” and Fairy Tale Nationalism.» Style 47, no. 4 (2013): 490-508. www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.47.4.490.

- Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). Hänsel und Gretel: das Märchen in Kunst, Musik, Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen (in German). Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0469-8.

- Taggart, James M. «»Hansel and Gretel» in Spain and Mexico.» The Journal of American Folklore 99, no. 394 (1986): 435-60. doi:10.2307/540047.

- Zipes, Jack (1997). «The rationalization of abandonment and abuse in fairy tales: The case of Hansel and Gretel». Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales, Children, and the Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25296-0.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Hansel and Gretel at Project Gutenberg

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including Hansel and Gretel at Standard Ebooks

- Hansel and Gretel fairy tale

- Original versions and psychological analysis of classic fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel

- The Story of Hansel and Gretel

- Collaboratively illustrated story on Project Bookses

- https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/hansel_and_gretel

Братья Гримм не нуждаются в особом представлении. Их творчество широко известно во многих странах и дети уже около полутора века с удовольствием читают их замечательные сказки. Предлагаем вам ближе познакомится со сказкой «Гензель и Гретель», которая будет интересна не только вашему ребёнку, а и, вполне вероятно, понравится и вам самим.

Творчество братьев Гримм

Якоб и Вильгельм ещё во время своей учёбы в Марбургском университете благодаря талантливому молодому исследователю фон Савиньи начали знакомиться с германской историей и фольклором.

Очень быстро новое увлечение переросло в настоящую страсть. По окончании учёбы братья начали сами собирать немецкие народные сказки, песни, легенды, предания. Накопленный материал они использовали для научных исследований по фольклористике. После литературной обработки в 1812 году братья Гримм выпустили сборник сказок. А через три года последовал второй сборник.

Якоб и Вильгельм очень ответственно относились к своему увлечению. Они максимально точно и подробно записывали фольклорные произведения, чтобы сохранить их колоритный язык и образность. Они старались больше общаться со стариками из простого народа, потому что они были настоящим кладезем народного творчества.

Кроме сказок Гриммы обработали и издали такие памятники народной немецкой литературы как «Песни старой Эдды», «Песнь о Роланде», «Бедный Хейнрих» и другие. Они также перевели на немецкий язык ряд ирландских, шотландских и датских народных сказок.

Обычно братья работали вместе, но есть у них и работы, написанные раздельно. Якоб Гримм выпустил «Немецкую грамматику». Это произведение невозможно переоценить, ведь оно фактические положило начало немецкой филологии. Среди известных работ Вильгельма — «Немецкие героические сказания».

В конце 1830 годов братья приступают к самому своему титаническому и глобальному труду — созданию «Немецкого словаря». Они были первопроходцами в этом деле и начинали работу практически с нуля. Собиранием и описанием слов родного языка они занимались до конца своих жизней.

Лучшие сказки братьев Гримм:

- «Белоснежка и семь гномов»;

- «Волк и семеро козлят»;

- «Красная Шапочка»;

- «Гензель и Гретель»;

- «Рапунцель»;

- «Бременские музыканты»;

- «Горшочек каши» и многие другие

Краткое содержание сказки «Гензель и Гретель»

Рано утром отец отводит брата и сестру в лес. Но Гензель смекалистый мальчик — по дороге в чащу леса он разбрасывает белые камешки, по которым дети позже возвращаются в родной дом.

Тогда жена опять заставляет дровосека отвести детей в чащобу. В этот раз у Гензеля с собой оказался лишь ломоть хлеба. Крошки, которые он бросал по дороге, склевали птицы, поэтому брат и сестра не могут найти путь домой.

Три дня бедолаги бродят по лесу, пока наконец не находят удивительный дом. Его стены сложены из пирогов, сахара и хлеба. Голодные дети начинают с жадностью объедать избушку. И тут их хватает старая злая колдунья, которая живёт здесь.

Гензеля старуха садит в клетку и начинает интенсивно откармливать, чтобы вскоре съесть. Гретель ведьма делает своей прислугой. Людоедка через некоторое время начинает проверять, насколько откормлен мальчик — подслеповатая карга засовывает в клетку руку, чтобы пощупать Гретеля, но он каждый раз подсовывает ей кость. Наконец старуха понимает, что её водят за нос.

Она начинает приготовления, чтобы как можно быстрее съесть мальчишку. Ведьма приказывает Гретель растопить печь и залезть в неё, чтобы узнать, достаточно ли та горяча. Девочка идёт на хитрость — говорит, что она неопытна в этом деле и чтобы старуха показала ей, как всё правильно сделать.

Злая старуха открывает печь и в этот момент Гретель толкает её внутрь и закрывает заслон. Ведьма погибает в огне, а брат с сестрой, забрав сокровища из пряничного домика, возвращаются домой, к отцу.

Читайте на нашем сайте самые интересные и поучительные сказки со всего мира!

Время чтения: 18 мин.

В большом лесу на опушке жил бедный дровосек со своею женою и двумя детьми: мальчишку-то звали Гензель, а девчоночку — Гретель.

У бедняка было в семье и скудно и голодно; а с той поры, как наступила большая дороговизна, у него и насущного хлеба иногда не бывало.

И вот однажды вечером лежал он в постели, раздумывая и ворочаясь с боку на бок от забот, и сказал своей жене со вздохом: «Не знаю, право, как нам и быть! Как будем мы детей питать, когда и самим-то есть нечего!»

— «А знаешь ли что, муженек, — отвечала жена, — завтра ранешенько выведем детей в самую чащу леса; там разведем им огонек и каждому дадим еще по кусочку хлеба в запас, а затем уйдем на работу и оставим их там одних. Они оттуда не найдут дороги домой, и мы от них избавимся».

— «Нет, женушка, — сказал муж, — этого я не сделаю. Невмоготу мне своих деток в лесу одних оставлять — еще, пожалуй, придут дикие звери да и растерзают».

— «Ох ты, дурак, дурак! — отвечала она. — Так разве же лучше будет, как мы все четверо станем дохнуть с голода, и ты знай строгай доски для гробов».

И до тех пор его пилила, что он наконец согласился. «А все же жалко мне бедных деток», — говорил он, даже и согласившись с женою.

А детки-то с голоду тоже заснуть не могли и слышали все, что мачеха говорила их отцу. Гретель плакала горькими слезами и говорила Гензелю: «Пропали наши головы!»

— «Полно, Гретель, — сказал Гензель, — не печалься! Я как-нибудь ухитрюсь помочь беде».

И когда отец с мачехой уснули, он поднялся с постели, надел свое платьишко, отворил дверку, да и выскользнул из дома.

Месяц светил ярко, и белые голыши, которых много валялось перед домом, блестели, словно монетки. Гензель наклонился и столько набрал их в карман своего платья, сколько влезть могло.

Потом вернулся домой и сказал сестре: «Успокойся и усни с Богом: он нас не оставит». И улегся в свою постельку.

Чуть только стало светать, еще и солнце не всходило — пришла к детям мачеха и стала их будить: «Ну, ну, подымайтесь, лентяи, пойдем в лес за дровами».

Затем она дала каждому по кусочку хлеба на обед и сказала: «Вот вам хлеб на обед, только смотрите, прежде обеда его не съешьте, ведь уж больше-то вы ничего не получите».

Гретель взяла хлеб к себе под фартук, потому что у Гензеля карман был полнехонек камней. И вот они все вместе направились в лес.

Пройдя немного, Гензель приостановился и оглянулся на дом, и потом еще и еще раз.

Отец спросил его: «Гензель, что ты там зеваешь и отстаешь? Изволь-ка прибавить шагу».

— «Ах, батюшка, — сказал Гензель, — я все посматриваю на свою белую кошечку: сидит она там на крыше, словно со мною прощается».

Мачеха сказала: «Дурень! Да это вовсе и не кошечка твоя, а белая труба блестит на солнце». А Гензель и не думал смотреть на кошечку, он все только потихонечку выбрасывал на дорогу из своего кармана по камешку.

Когда они пришли в чащу леса, отец сказал: «Ну, собирайте, детки, валежник, а я разведу вам огонек, чтобы вы не озябли».

Гензель и Гретель натаскали хворосту и навалили его гора-горой. Костер запалили, и когда огонь разгорелся, мачеха сказала: «Вот, прилягте к огоньку, детки, и отдохните; а мы пойдем в лес и нарубим дров. Когда мы закончим работу, то вернемся к вам и возьмем с собою».

Гензель и Гретель сидели у огня, и когда наступил час обеда, они съели свои кусочки хлеба. А так как им слышны были удары топора, то они и подумали, что их отец где-нибудь тут же, недалеко.

А постукивал-то вовсе не топор, а простой сук, который отец подвязал к сухому дереву: его ветром раскачивало и ударяло о дерево.

Сидели они, сидели, стали у них глаза слипаться от усталости, и они крепко уснули.

Когда же они проснулись, кругом была темная ночь. Гретель стала плакать и говорить: «Как мы из лесу выйдем?» Но Гензель ее утешал: «Погоди только немножко, пока месяц взойдет, тогда уж мы найдем дорогу».

И точно, как поднялся на небе полный месяц, Гензель взял сестричку за руку и пошел, отыскивая дорогу по голышам, которые блестели, как заново отчеканенные монеты, и указывали им путь.

Всю ночь напролет шли они и на рассвете пришли-таки к отцовскому дому. Постучались они в двери, и когда мачеха отперла и увидела, кто стучался, то сказала им: «Ах вы, дрянные детишки, что вы так долго заспались в лесу? Мы уж думали, что вы и совсем не вернетесь».

А отец очень им обрадовался: его и так уж совесть мучила, что он их одних покинул в лесу.

Вскоре после того нужда опять наступила страшная, и дети услышали, как мачеха однажды ночью еще раз стала говорить отцу: «Мы опять все съели; в запасе у нас всего-навсего полкаравая хлеба, а там уж и песне конец! Ребят надо спровадить; мы их еще дальше в лес заведем, чтобы они уж никак не могли разыскать дороги к дому. А то и нам пропадать вместе с ними придется».

Тяжело было на сердце у отца, и он подумал: «Лучше было бы, кабы ты и последние крохи разделил со своими детками». Но жена и слушать его не хотела, ругала его и высказывала ему всякие упреки.

«Назвался груздем, так и полезай в кузов!» — говорит пословица; так и он: уступил жене первый раз, должен был уступить и второй.

А дети не спали и к разговору прислушивались. Когда родители заснули, Гензель, как и в прошлый раз, поднялся с постели и хотел набрать голышей, но мачеха заперла дверь на замок, и мальчик никак не мог выйти из дома. Но он все же унимал сестричку и говорил ей: «Не плачь, Гретель, и спи спокойно. Бог нам поможет».

Рано утром пришла мачеха и подняла детей с постели. Они получили по куску хлеба — еще меньше того, который был им выдан прошлый раз.

По пути в лес Гензель искрошил свой кусок в кармане, часто приостанавливался и бросал крошки на землю.

«Гензель, что ты все останавливаешься и оглядываешься, — сказал ему отец, — ступай своей дорогой».

— «Я оглядываюсь на своего голубка, который сидит на крыше и прощается со мною», — отвечал Гензель. «Дурень! — сказала ему мачеха. — Это вовсе не голубок твой: это труба белеет на солнце».

Но Гензель все же мало-помалу успел разбросать все крошки по дороге.

Мачеха еще дальше завела детей в лес, туда, где они отродясь не бывали.

Опять был разведен большой костер, и мачеха сказала им: «Посидите-ка здесь, и коли умаетесь, то можете и поспать немного: мы пойдем в лес дрова рубить, а вечером, как кончим работу, зайдем за вами и возьмем вас с собою».

Когда наступил час обеда, Гретель поделилась своим куском хлеба с Гензелем, который свою порцию раскрошил по дороге.

Потом они уснули, и уж завечерело, а между тем никто не приходил за бедными детками.

Проснулись они уже тогда, когда наступила темная ночь, и Гензель, утешая свою сестричку, говорил: «Погоди, Гретель, вот взойдет месяц, тогда мы все хлебные крошечки увидим, которые я разбросал, по ним и отыщем дорогу домой».

Но вот и месяц взошел, и собрались они в путь-дорогу, а не могли отыскать ни одной крошки, потому что тысячи птиц, порхающих в лесу и в поле, давно уже те крошки поклевали.

Гензель сказал сестре: «Как-нибудь найдем дорогу», — но дороги не нашли.

Так шли они всю ночь и еще один день с утра до вечера и все же не могли выйти из леса и были страшно голодны, потому что должны были питаться одними ягодами, которые кое-где находили по дороге. И так как они притомились и от истомы уже еле на ногах держались, то легли они опять под деревом и заснули.

Настало третье утро с тех пор, как они покинули родительский дом. Пошли они опять по лесу, но сколько ни шли, все только глубже уходили в чащу его, и если бы не подоспела им помощь, пришлось бы им погибнуть.

В самый полдень увидели они перед собою прекрасную белоснежную птичку; сидела она на ветке и распевала так сладко, что они приостановились и стали к ее пению прислушиваться. Пропевши свою песенку, она расправила свои крылышки и полетела, и они пошли за нею следом, пока не пришли к избушке, на крышу которой птичка уселась.

Подойдя к избушке поближе, они увидели, что она вся из хлеба построена и печеньем покрыта, да окошки-то у нее были из чистого сахара.

«Вот мы за нее и примемся, — сказал Гензель, — и покушаем. Я вот съем кусок крыши, а ты, Гретель, можешь себе от окошка кусок отломить — оно, небось, сладкое». Гензель потянулся кверху и отломил себе кусочек крыши, чтобы отведать, какова она на вкус, а Гретель подошла к окошку и стала обгладывать его оконницы.

Тут из избушки вдруг раздался пискливый голосок:

Стуки-бряки под окном?

Кто ко мне стучится в дом?

А детки на это отвечали:

Ветер, ветер, ветерок.

Неба ясного сынок!

— и продолжали по-прежнему кушать.

Гензель, которому крыша пришлась очень по вкусу, отломил себе порядочный кусок от нее, а Гретель высадила себе целую круглую оконницу, тут же у избушки присела и лакомилась на досуге — и вдруг распахнулась настежь дверь в избушке, и старая-престарая старуха вышла из нее, опираясь на костыль.

Гензель и Гретель так перепугались, что даже выронили свои лакомые куски из рук. А старуха только покачала головой и сказала: «Э-э, детушки, кто это вас сюда привел? Войдите-ка ко мне и останьтесь у меня, зла от меня никакого вам не будет».

Она взяла деток за руку и ввела их в свою избушечку. Там на столе стояла уже обильная еда: молоко и сахарное печенье, яблоки и орехи. А затем деткам были постланы две чистенькие постельки, и Гензель с сестричкой, когда улеглись в них, подумали, что в самый рай попали.

Но старуха-то только прикинулась ласковой, а в сущности была она злою ведьмою, которая детей подстерегала и хлебную избушку свою для того только и построила, чтобы их приманивать.

Когда какой-нибудь ребенок попадался в ее лапы, она его убивала, варила его мясо и пожирала, и это было для нее праздником. Глаза у ведьм красные и не дальнозоркие, но чутье у них такое же тонкое, как у зверей, и они издалека чуют приближение человека. Когда Гензель и Гретель только еще подходили к ее избушке, она уже злобно посмеивалась и говорила насмешливо: «Эти уж попались — небось, не ускользнуть им от меня».

Рано утром, прежде нежели дети проснулись, она уже поднялась, и когда увидела, как они сладко спят и как румянец играет на их полных щечках, она пробормотала про себя: «Лакомый это будет кусочек!»

Тогда взяла она Гензеля в свои жесткие руки и снесла его в маленькую клетку, и приперла в ней решетчатой дверкой: он мог там кричать сколько душе угодно, — никто бы его и не услышал. Потом пришла она к сестричке, растолкала ее и крикнула: «Ну, поднимайся, лентяйка, натаскай воды, свари своему брату чего-нибудь повкуснее: я его посадила в особую клетку и стану его откармливать. Когда он ожиреет, я его съем».

Гретель стала было горько плакать, но только слезы даром тратила — пришлось ей все, то исполнить, чего от нее злая ведьма требовала.

Вот и стали бедному Гензелю варить самое вкусное кушанье, а сестричке его доставались одни только объедки.

Каждое утро пробиралась старуха к его клетке и кричала ему: «Гензель, протяни-ка мне палец, дай пощупаю, скоро ли ты откормишься?» А Гензель просовывал ей сквозь решетку косточку, и подслеповатая старуха не могла приметить его проделки и, принимая косточку за пальцы Гензеля, дивилась тому, что он совсем не жиреет.

Когда прошло недели четыре и Гензель все попрежнему не жирел, тогда старуху одолело нетерпенье, и она не захотела дольше ждать. «Эй ты, Гретель, — крикнула она сестричке, — проворней наноси воды: завтра хочу я Гензеля заколоть и сварить — каков он там ни на есть, худой или жирный!»

Ах, как сокрушалась бедная сестричка, когда пришлось ей воду носить, и какие крупные слезы катились у ней по щекам! «Боже милостивый! — воскликнула она. — Помоги же ты нам! Ведь если бы дикие звери растерзали нас в лесу, так мы бы, по крайней мере, оба вместе умерли!»

— «Перестань пустяки молоть! — крикнула на нее старуха. — Все равно ничто тебе не поможет!»

Рано утром Гретель уже должна была выйти из дома, повесить котелок с водою и развести под ним огонь.

«Сначала займемся печеньем, — сказала старуха, — я уж печь затопила и тесто вымесила».

И она толкнула бедную Гретель к печи, из которой пламя даже наружу выбивалось.

«Полезай туда, — сказала ведьма, — да посмотри, достаточно ли в ней жару и можно ли сажать в нее хлебы».

И когда Гретель наклонилась, чтобы заглянуть в печь, ведьма собиралась уже притворить печь заслонкой: «Пусть и она там испечется, тогда и ее тоже съем».

Однако же Гретель поняла, что у нее на уме, и сказала: «Да я и не знаю, как туда лезть, как попасть в нутро?»

— «Дурища! — сказала старуха. — Да ведь устье-то у печки настолько широко, что я бы и сама туда влезть могла», — да, подойдя к печке, и сунула в нее голову.

Тогда Гретель сзади так толкнула ведьму, что та разом очутилась в печке, да и захлопнула за ведьмой печную заслонку, и даже засовом задвинула.

Ух, как страшно взвыла тогда ведьма! Но Гретель от печки отбежала, и злая ведьма должна была там сгореть.

А Гретель тем временем прямехонько бросилась к Гензелю, отперла клетку и крикнула ему: «Гензель! Мы с тобой спасены — ведьмы нет более на свете!»

Тогда Гензель выпорхнул из клетки, как птичка, когда ей отворят дверку.

О, как они обрадовались, как обнимались, как прыгали кругом, как целовались! И так как им уж некого было бояться, то они пошли в избу ведьмы, в которой по всем углам стояли ящики с жемчугом и драгоценными каменьями. «Ну, эти камешки еще получше голышей», — сказал Гензель и набил ими свои карманы, сколько влезло; а там и Гретель сказала: «Я тоже хочу немножечко этих камешков захватить домой», — и насыпала их полный фартучек.

«Ну, а теперь пора в путь-дорогу, — сказал Гензель, — чтобы выйти из этого заколдованного леса».

И пошли — и после двух часов пути пришли к большому озеру. «Нам тут не перейти, — сказал Гензель, — не вижу я ни жердинки, ни мосточка». — «И кораблика никакого нет, — сказала сестричка. — А зато вон там плавает белая уточка. Коли я ее попрошу, она, конечно, поможет нам переправиться».

И крикнула уточке:

Уточка, красавица!

Помоги нам переправиться;

Ни мосточка, ни жердинки,

Перевези же нас на спинке.

Уточка тотчас к ним подплыла, и Гензель сел к ней на спинку и стал звать сестру, чтобы та села с ним рядышком. «Нет, — отвечала Гретель, — уточке будет тяжело; она нас обоих перевезет поочередно».

Так и поступила добрая уточка, и после того, как они благополучно переправились и некоторое время еще шли по лесу, лес стал им казаться все больше и больше знакомым, и наконец они увидели вдали дом отца своего.

Тогда они пустились бежать, добежали до дому, ворвались в него и бросились отцу на шею.

У бедняги не было ни часу радостного с тех пор, как он покинул детей своих в лесу; а мачеха тем временем умерла.

Гретель тотчас вытрясла весь свой фартучек — и жемчуг и драгоценные камни так и рассыпались по всей комнате, да и Гензель тоже стал их пригоршнями выкидывать из своего кармана.

Тут уж о пропитании не надо было думать, и стали они жить да поживать, да радоваться.

- Краткие содержания

- Гримм Братья

- Гензель и Гретель (Пряничный домик)

Краткое содержание Гензель и Гретель братьев Грим (Пряничный домик)

В дремучем лесу жил дровосек с двумя детьми и женой. Не любила мачеха детишек, поэтому когда настало голодное время, решила она завести детей в лес и там оставить. Не хотел отец соглашаться с женой — сердце не давало. Вскоре она все-таки уговорила его помочь. В то время в соседней комнате дети не спали и слышали все, о чем взрослые говорили. Залилась Гретель слезами, не хотела погибать в лесу. Недолго думая, Гензель незаметно вышел на улицу, насобирал белые камешки, которые блестели при свете луны. Вернувшись, он успокоил сестру и легли они спать.

Ни свет ни заря пришла мачеха будить детей, чтобы собирались с ними в лес за дровами. Всю дорогу Гензель медленно шел, останавливался и никто даже не заметил, как бросал камешки на тропинку. Придя в лес, развел отец костер и скрылся с женой в лесу, дети остались их ждать. Так долго они ждали, что уснули. Проснувшись уже глубокой ночью, пошли они по тропинке следуя камням. На рассвете они уже подходили к дому, там их и встретила злая мачеха. Отец обрадовался их появлению, но жена вновь его уговорила завести детей в лес, только на этот раз в более густой. Подслушав план, Гретель вновь загрустила. Гензель хотел опять насобирать камешков, но предусмотрительная мачеха заперла дверь.

Утром принялась она их опять будить в лес. Идя по лесной тропе Гензель, не придумал ничего другого, как бросать под ноги крошки хлеба, что ему дала мачеха. Дровосек вновь развел большой костер и удалился с женой в заросли. В ожидании дети опять заснули. Проснувшись от лесного шума, принялись искать путь домой, но столько птиц днем летало, что ни одной крошки не осталось.

Шли так три дня, пока не набрели на пряничный домик. Дети были так голодны, что начали его обгрызать. Немедля из дома вышла старуха, пригласила детей в дом, накормила, уложила спать. Никто не знал, что она ведьма, которая ест детей. Утром старуха заперла Гензель в хлеву, а Гретель использовала как служанку. Заставляла ее готовить блюда для брата, чтобы он отъедался. Лопнуло терпение ведьмы, решила сварить Гензель, но перед этим попросив Гретель полезть в печь, проверить жар. Сестра сделала вид, что не умеет, на что ведьма, ворча, сама полезла в печь. В тот самый момент Гретель затолкала ее внутрь и закрыла заслонку. Так и избавились дети от старухи. Решив, что пора им возвращаться домой пошли на поиски родных мест.

Вернувшись домой, встретили отца на пороге, а мачеха давно померла. Дети рассказали ему свое приключение, а также показали дары, которые забрали с ведьминых ларцов. Так и зажили они счастливо, и не знали больше бед.

Сказка учит нас тому, что надо любить своих детей и делиться с ними последним, а также поддерживать в тяжелых ситуациях.

Очень кратко