Толковый словарь русского языка. Поиск по слову, типу, синониму, антониму и описанию. Словарь ударений.

Найдено определений: 5

георгий победоносец

ПОПУЛЯРНЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Георгий Победоносец

Гео́ргия Победоно́сца, м.

В христианских и мусульманских преданиях: святой великомученик из военного сословия, считавшийся в народе покровителем земледелия и скотоводства и почитавшийся на Руси под именем Юрия или Егория Храброго.

Этимология:

Георгий — имя собственное, заимствованное древнерусским языком из книжного греческого, устным путем трансформированное в Юрий.

Энциклопедический комментарий:

Христианская житийная литература говорит о Георгии Победоносце как о современнике римского императора Диоклетиана. Уроженец восточной Малой Азии, принадлежащий к местной знати, он дослужился до высокого военного чина. Во время гонения на христиан его пытались истязаниями принудить к отречению от веры и в конце концов отрубили голову. Памятные праздничные дни — 23 апреля и 26 ноября.

Изображения святого Георгия встречаются издревле на великокняжеских монетах и печатях. С XIV в. он считается покровителем Москвы, а изображение всадника на коне становится эмблемой Москвы. Позднее изображение святого Георгия на вздыбившемся коне, поражающего копьем дракона, вошло в состав герба Российской империи. В 1769 г. в России был учрежден военный орден св. великомученика и победоносца Георгия, в 1913 г. — военный Георгиевский крест.

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — ГЕО́РГИЙ ПОБЕДОНО́СЕЦ (в России Егорий Храбрый), христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Каппадокии (на территории совр. Турции). Принял мученическую смерть в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане (см. ДИОКЛЕТИАН); день памяти в Православной церкви отмечается 23 апреля (6 мая), 26 ноября (9 декабря — Юрьев день (см. ЮРЬЕВ ДЕНЬ) ).

Древние легенды

Культ Георгия, по-видимому, распространился из города Лидда (Палестина), где в древности показывали гробницу святого. Древнейшие сведения о нем имеются во вьеннском палимпсесте (4-5 вв.). В христианской житийной литературе о нем говорится как о воине знатного происхождения, которого во время гонений Диоклетиана пытались принудить отречься от веры. Поэтому он вместе с Дмитрием Солунским, Феодором Стратилатом, Феодором Тироном (см. ФЕОДОР Тирон) и др. считается одним из «воинства небесного». Считается также и покровителем воинов на Западе и Востоке. Очень распространенная легенда повествует о победе Георгия над чудовищным змеем-драконом, пожиравшим молодых девушек. Георгий укрощает дракона силой божественного слова и приводит его в город, после чего горожане и правитель, пораженные силой веры, принимают крещение. В этом сказании явно видны отголоски языческих сюжетов (напр., Персей и Андромеда (см. ПЕРСЕЙ (в мифологии))), оно приводится обычно в редакции «Золотой легенды» Иакова Ворагинского (см. ИАКОВ из Варацце) .

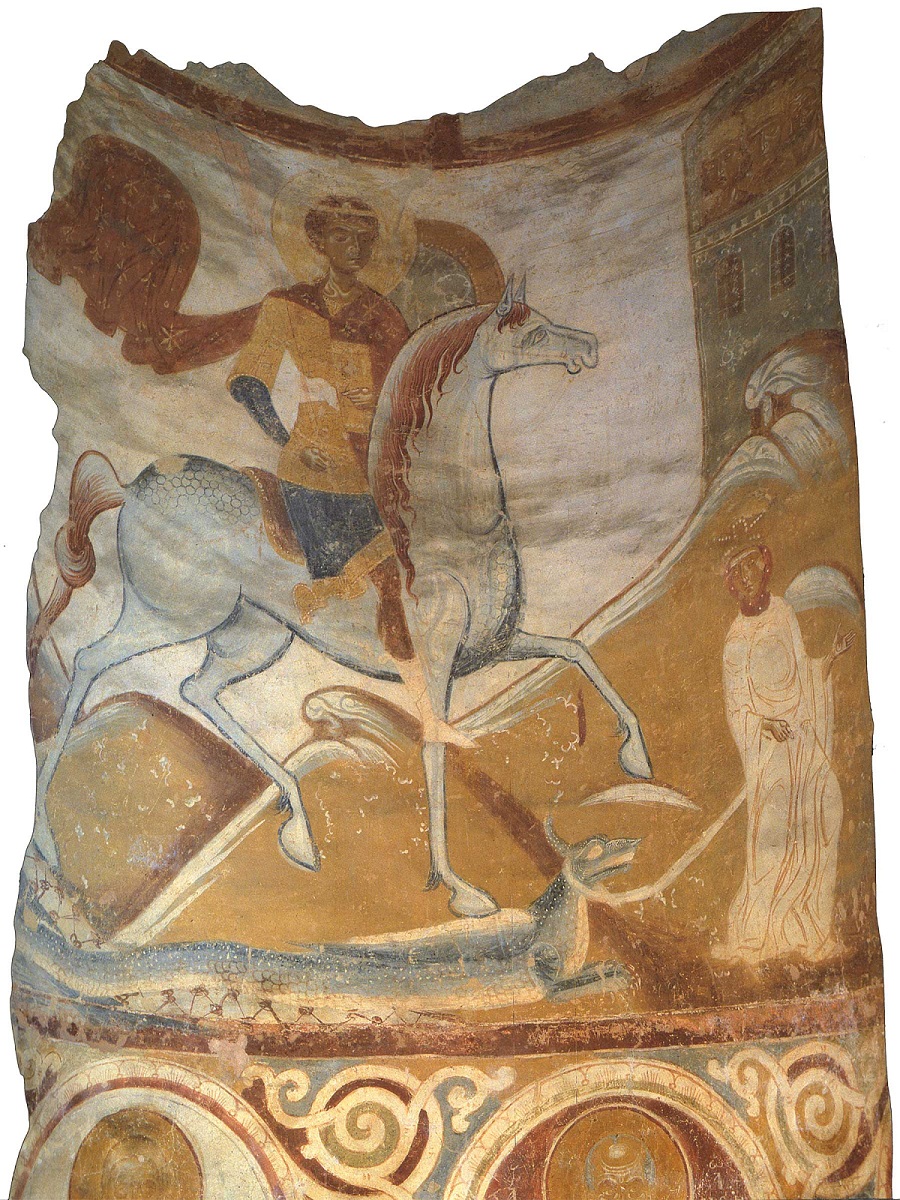

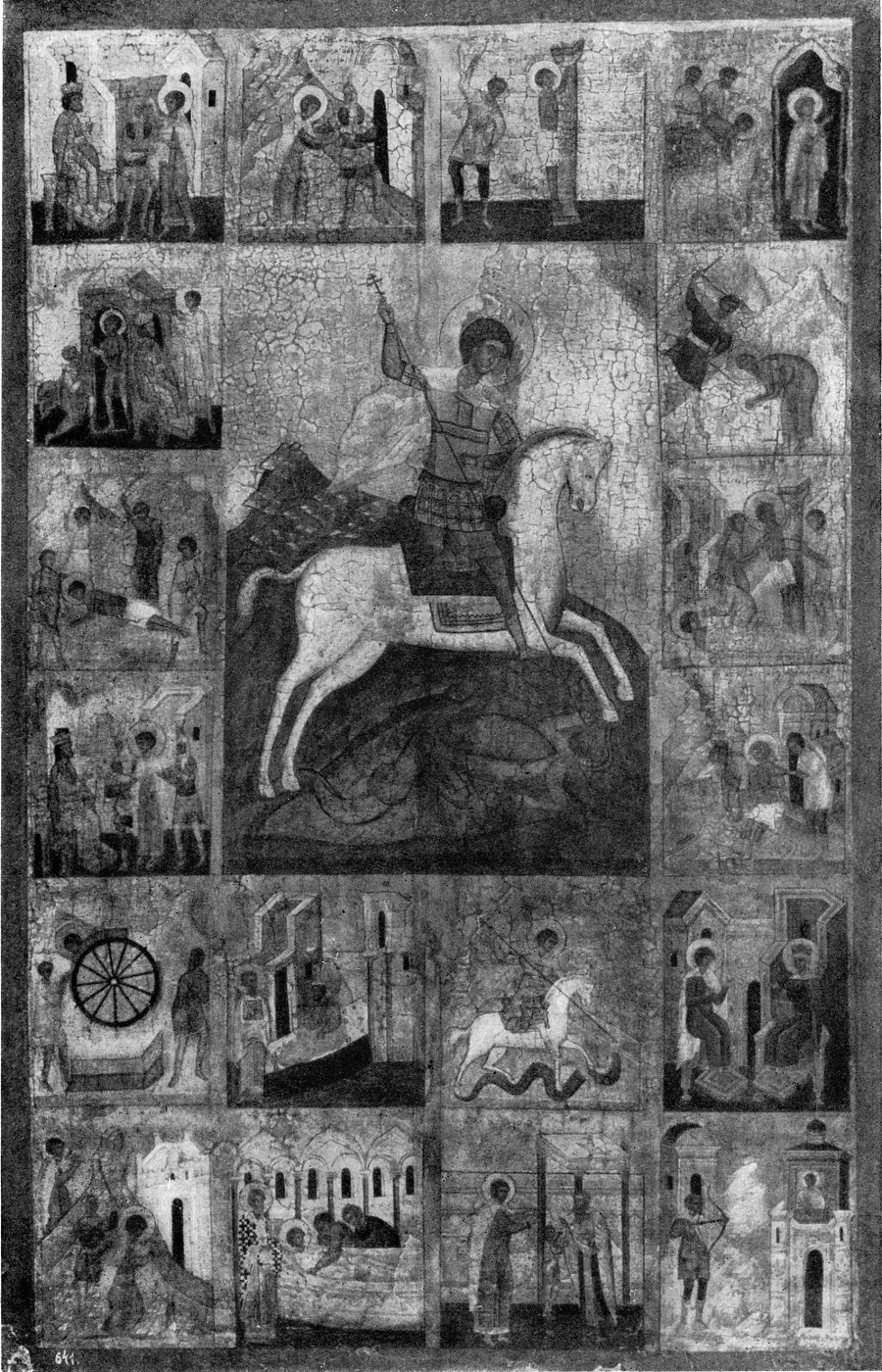

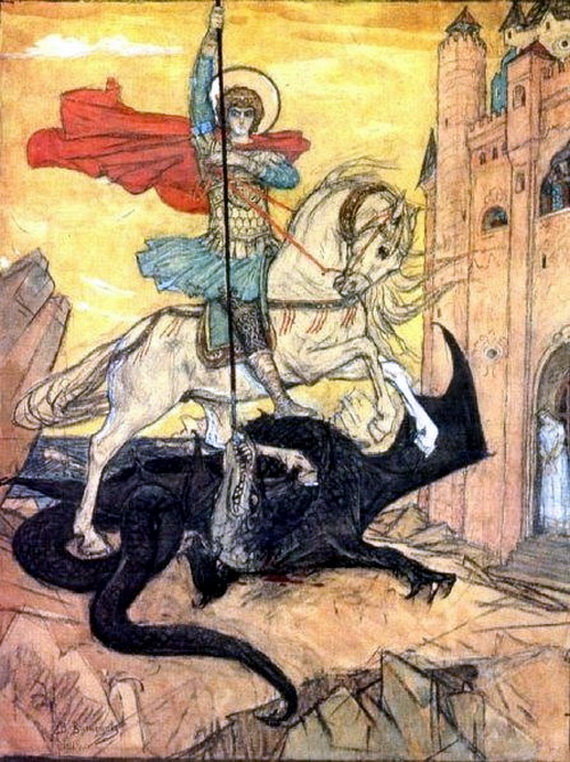

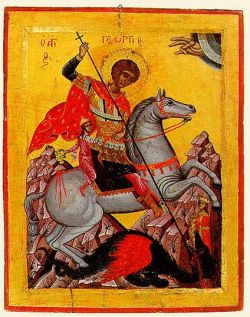

Иконография. Народные предания

Каноническое изображение Георгия, согласно легенде, — всадник, поражающий змия. В византийской иконографии известно его изображение на молитве с собственной отрубленной головой в руках. В русских духовных «стихах о Егории Храбром» мотив поединка со змеем отсутствует, а Георгий изображается крестителем Руси, побеждающем на богатырском поединке язычника «царища Демьянища». В русской народной традиции Георгий выступает также и как покровитель домашнего скота («Из-за леса из-за гор едет дедушка Егор. Сам на лошадке, жена на коровке…»). Как змееборец он отвращает змей и от людей. В славянских народных вариантах его имени (Юрий, Юра, Юрай) некоторые исследователи видят перенесение на Георгия черт весенних божеств плодородия (Ярило и Яровит). В весенний Юрьев день на пастбища выгоняли скотину. Кроме змей, Георгий отгоняет от скота и волков, которых нередко называют его собаками.

Георгий-рыцарь

Легенда о Георгии была особенно популярна на Западе в эпоху крестовых походов. Он считался образцовым рыцарем, победителем язычников (змей — символ язычества), заступником Прекрасной Дамы. Крест святого Георгия — красный на белом поле. Он считается патроном Англии, ему посвящен орден Подвязки (см. ПОДВЯЗКИ ОРДЕН), позднее в Англии был учрежден крест святого Георгия.

Георгий в России и на Востоке

В России Георгий считался покровителем князей. Изображение всадника было эмблемой Москвы с 14 века, позднее этого всадника стали отождествлять со святым Георгием, а еще позже его изображение было включено в состав герба Российской империи (см. Двуглавый орел (см. ДВУГЛАВЫЙ ОРЕЛ)). Георгию был посвящен военный орден (см. ОРДЕН ГЕОРГИЯ) .

В Грузии считается покровителем страны под именем Гиорги, особо почитается среди христиан Осетии. Георгий (Джирдис) — популярный герой мусульманских преданий, в которых особо подчеркивается мотив его троекратного умирания и воскресания во время пыток.

БОЛЬШОЙ ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Капиадокии (на территории совр. Турции). Замучен в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане; день памяти отмечается 23.4(6.5). Покровитель земледелия и скотоводства. На иконах, гербах и других предметах изображается в виде конного воина, поражающего копьем дракона («Чудо Георгия о змие»). Георгий Победоносец — герой многочисленных сказаний, песен, легенд у христиан (у русских под именем Егория или Юрия) и мусульманских народов.

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЯ КОЛЬЕРА

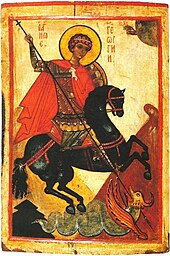

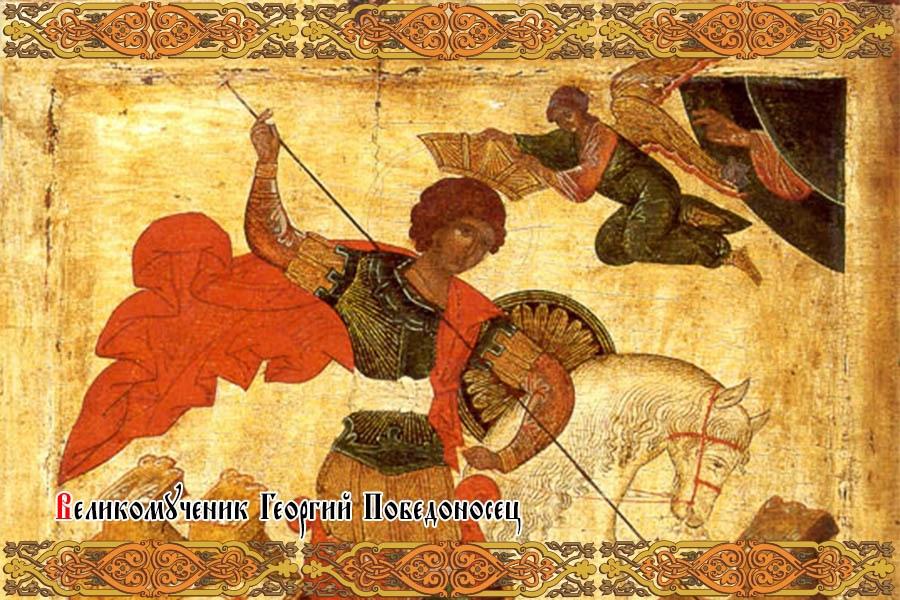

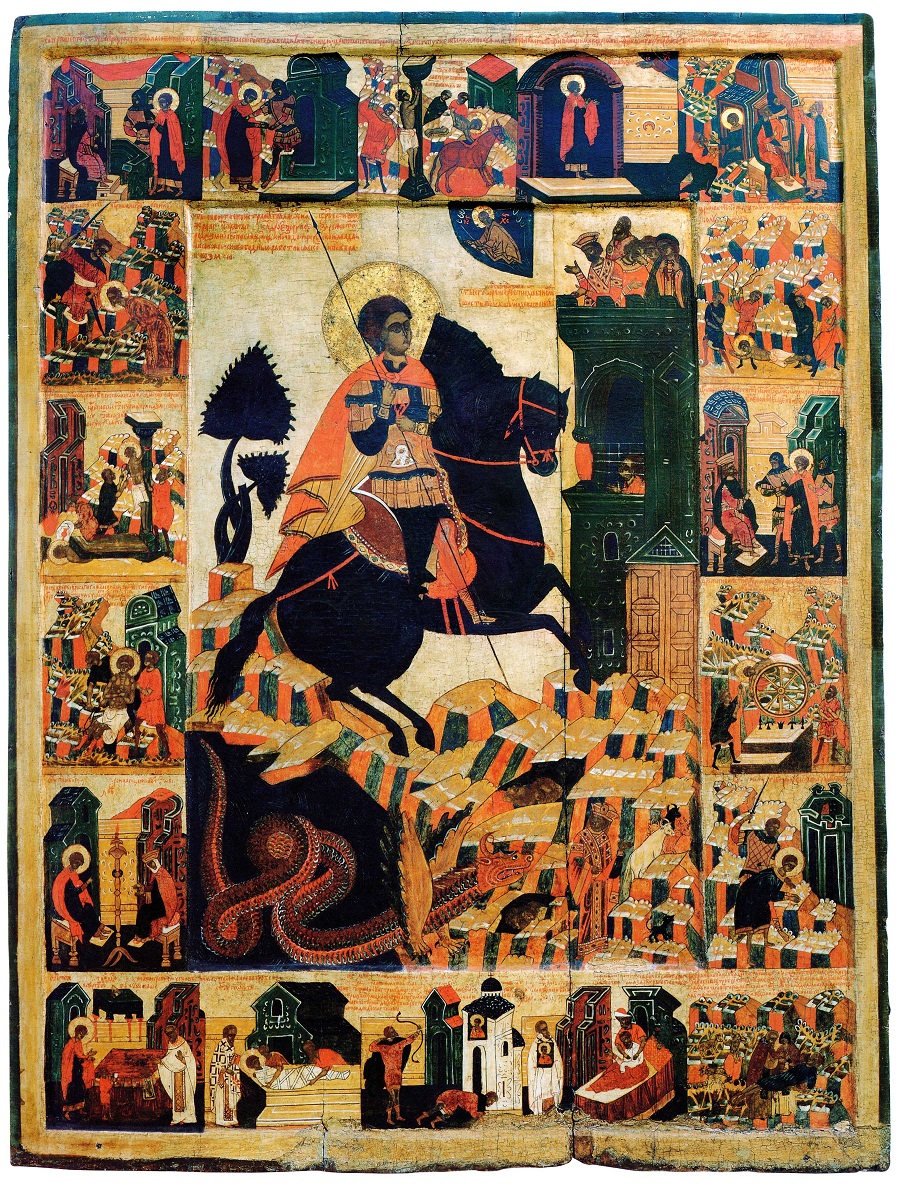

СВ. ГЕОРГИЙ поражает дракона. Икона 17 в.

СВ. (умер ок. 303), святой покровитель Англии, принял мученическую смерть в Лидде (Палестина), вероятно, до начала эпохи Константина Великого. За исключением факта мученичества, достоверных сведений о св. Георгии крайне мало. Однако его почитание возникает очень рано: впервые о нем упоминает уже папа Геласий в декрете «О принимаемых книгах» (De libris recipiendis, 494). Рассказ о победе св. Георгия над змеем (драконом) вошел в житие святого в 12 в. и получил известность главным образом благодаря Золотой легенде (Legenda Aurea) Якова Ворагинского. Согласно этой легенде, Георгий, воин из Каппадокии, прибыл в Селену в Ливии и узнал, что жители города живут в страхе перед драконом, которому вынуждены приносить человеческие жертвы. На этот раз жертвой должна была стать дочь самого царя. Георгий сразился с драконом и пронзил его копьем. После этого он обвязал шею чудовища поясом принцессы и, ведя его за собой, возвратился вместе с принцессой в город. Там он прикончил дракона, убедил горожан принять крещение и ускакал прочь, отказавшись от награды. Почитание св. Георгия в Англии восходит по крайней мере к 8 в. Приблизительно с 14 в. крест св. Георгия украшает английский флаг. В 1347 король Эдуард III основал «Орден Подвязки», главным покровителем которого был избран св. Георгий. В 1415 день памяти святого, 23 апреля, получил статус великого праздника, и св. Георгий был провозглашен покровителем Англии. В Русской православной церкви день памяти святого 23 апреля по старому стилю.

ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ

Георгий Победоносец

- Георгий Победоносец

-

Ге’оргий Победон’осец

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Смотреть что такое «Георгий Победоносец» в других словарях:

-

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — (в России Егорий Храбрый), христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Каппадокии (на территории совр. Турции). Принял мученическую смерть в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане (см … Энциклопедический словарь

-

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ, христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Каппадокии (на территории современной Турции). Замучен в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане; день памяти… … Современная энциклопедия

-

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Капиадокии (на территории совр. Турции). Замучен в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане; день памяти отмечается 23.4(6.5). Покровитель… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Георгий Победоносец — (в русском фольклоре Егорий Храбрый, мусульманском Джирджис) в христианстве и исламе воин мученик. Георгий жил в 3 в., уроженец Малой Азии (Каппадокия), дослужился до высокого военного чина. Во время гонений на христиан его пытались принудить… … Исторический словарь

-

Георгий Победоносец — (греч. , в рус. фольклоре Егорий Храбрый, мусульм. Д ж и р д ж и с), в христианских и мусульманских преданиях воин мученик, с именем которого фольклорная традиция связала реликтовую языческую обрядность весенних скотоводческих и отчасти… … Энциклопедия культурологии

-

Георгий Победоносец — (в России Егорий Храбрый) христианский святой, великомученик. Согласно христианскому преданию, уроженец Каппадокии (на территории совр. Турции). Принял мученическую смерть в 303 во время гонений на христиан при римском императоре Диоклетиане;… … Политология. Словарь.

-

Георгий Победоносец — Запрос «Святой Георгий» перенаправляется сюда; см. также другие значения. У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Георгий Победоносец (значения). Георгий Победоносец Γεώργιος … Википедия

-

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — Христианский святой великомученик, один из самых почитаемых Русской Православной Церковью. Дни памяти 23 апреля и 26 ноября (по старому стилю*). По преданию, римский воин, христианин, уроженец Каппадокии (территория современной Турции). Замучен в … Лингвострановедческий словарь

-

ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — великомученик (ск. 303), один из самых чтимых русских святых, покровитель Москвы и Русского государства. Не случайно своим покровителем его нарекли такие разные страны, как Россия, Англия и Грузия (официально последняя из них и именуется Страной… … Русская история

-

Георгий Победоносец (значения) — Георгий Победоносец может относиться с следующим статьям: Георгий Победоносец христианский святой воин, великомученик. Георгий Победоносец (броненосец) броненосец Российской Империи. Георгий Победоносец (монета) инвестиционная монета Банка России … Википедия

-

Георгий Победоносец. Символ Москвы и защитник православного воинства — Русская православная церковь отмечает 6 мая праздник cвятого великомученика Георгия Победоносца. В этот день Патриарх Московский и всея Руси Алексий II по традиции совершаетт праздничное богослужение в храме святого Георгия на Поклонной горе. По… … Энциклопедия ньюсмейкеров

|

Saint George |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Hans von Kulmbach (c. 1510) |

|

| Martyr, Patron of England | |

| Born | Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey) |

| Died | 23 April 303 Lydda, Syria Palaestina (modern-day Lod, Israel)[1][2] |

| Venerated in |

|

| Major shrine |

|

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Clothed as a crusader in plate armour or mail, often bearing a lance tipped by a cross, riding a white horse, often slaying a dragon. In the Greek East and Latin West he is shown with St George’s Cross emblazoned on his armour, or shield or banner. |

| Patronage | Many Patronages of Saint George exist around the world |

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος, translit. Geṓrgios, Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldier in the Roman army. Saint George was a soldier of Cappadocian Greek origin and member of the Praetorian Guard for Roman emperor Diocletian, who was sentenced to death for refusing to recant his Christian faith. He became one of the most venerated saints and megalomartyrs in Christianity, and he has been especially venerated as a military saint since the Crusades. He is respected by Christians, Druze, as well as some Muslims as a martyr of monotheistic faith.

In hagiography, as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers and one of the most prominent military saints, he is immortalized in the legend of Saint George and the Dragon. His memorial, Saint George’s Day, is traditionally celebrated on 23 April. Historically, the countries of England, Ukraine, Ethiopia, and Georgia, as well as Catalonia and Aragon in Spain, and Moscow in Russia, have claimed George as their patron saint, as have several other regions, cities, universities, professions, and organizations. The Church-Mosque of Saint George in Lod (Lydda), Israel, contains a sarcophagus believed by many Christians to contain St. George’s remains.[6]

Legend[edit]

Very little is known about George’s life, but it is thought he was a Roman officer of Greek descent who was martyred in one of the pre-Constantinian persecutions.[7] Beyond this, early sources give conflicting information.

The saint’s veneration dates to the 5th century with some certainty, and possibly even to the 4th. The addition of the dragon legend dates to the 11th century.

The earliest text which preserves fragments of George’s narrative is in a Greek hagiography which is identified by Hippolyte Delehaye of the scholarly Bollandists to be a palimpsest of the 5th century.[8] An earlier work by Eusebius, Church history, written in the 4th century, contributed to the legend but did not name George or provide significant detail.[9] The work of the Bollandists Daniel Papebroch, Jean Bolland, and Godfrey Henschen in the 17th century was one of the first pieces of scholarly research to establish the saint’s historicity, via their publications in Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca.[10] Pope Gelasius I stated in 494 that George was among those saints «whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are known only to God.»[11]

The most complete version, based upon the fifth-century Greek text but in a later form, survives in a translation into Syriac from about 600. From text fragments preserved in the British Library a translation into English was published in 1925.[12][13][14]

In the Greek tradition, George was born to Greek Christian parents, in Cappadocia. After his father died, his mother, who was originally from Lydda, in Syria Palaestina, returned with George to her hometown.[15] He went on to become a soldier for the Roman army, but, because of his Christian faith, he was arrested and tortured, «at or near Lydda, also called Diospolis»; on the following day, he was paraded and then beheaded, and his body was buried in Lydda.[15] According to other sources, after his mother’s death he travelled to the eastern imperial capital, Nicomedia,[16] where he was persecuted by one Dadianus. In later versions of the Greek legend, this name is rationalised to Diocletian, and George’s martyrdom is placed in the Diocletian persecution of AD 303. The setting in Nicomedia is also secondary, and inconsistent with the earliest cults of the saint being located in Diospolis.[17]

George was executed by decapitation on 23 April 303. A witness of his suffering convinced Empress Alexandra of Rome to become a Christian as well, so she joined George in martyrdom. His body was buried in Lydda, where Christians soon came to honour him as a martyr.[18][19]

George in the Acta Sanctorum, as collected in late 1600s and early 1700s. The Latin title De S Georgio Megalo-Martyre; Lyddae seu Diospoli in Palaestina translates as St. George Great-Martyr; [from] Lydda or Diospolis, in Palestine.

The Latin Passio Sancti Georgii (6th century) follows the general course of the Greek legend, but Diocletian here becomes Dacian, Emperor of the Persians. His martyrdom was greatly extended to more than twenty separate tortures over the course of seven years. Over the course of his martyrdom, 40,900 pagans were converted to Christianity, including the empress Alexandra. When George finally died, the wicked Dacian was carried away in a whirlwind of fire. In later Latin versions, the persecutor is the Roman emperor Decius, or a Roman judge named Dacian serving under Diocletian.[20]

Historicity[edit]

There is little information on the early life of George. Herbert Thurston in The Catholic Encyclopedia states that based upon an ancient cultus, narratives of the early pilgrims, and the early dedications of churches to George, going back to the fourth century, «there seems, therefore, no ground for doubting the historical existence of St. George», although no faith can be placed in either the details of his history or his alleged exploits.[21]

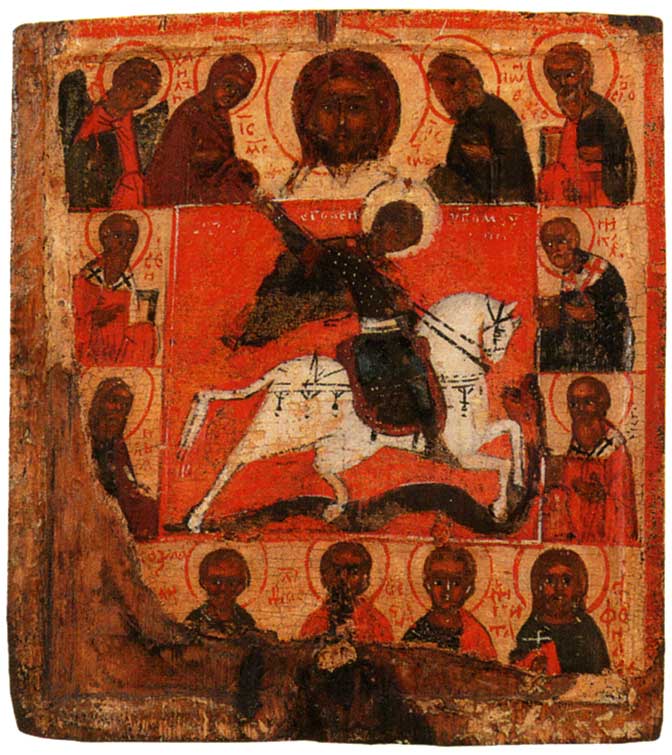

Russian icon (mid 14th century), Novgorod

The Diocletianic Persecution of 303, associated with military saints because the persecution was aimed at Christians among the professional soldiers of the Roman army, is of undisputed historicity. According to Donald Attwater,

No historical particulars of his life have survived, … The widespread veneration for St George as a soldier saint from early times had its centre in Palestine at Diospolis, now Lydda. St George was apparently martyred there, at the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century; that is all that can be reasonably surmised about him.[22]

Edward Gibbon[23][24] argued that George, or at least the legend from which the above is distilled, is based on George of Cappadocia,[25][17] a notorious 4th-century Arian bishop who was Athanasius of Alexandria’s most bitter rival, and that it was he who in time became George of England. This identification is seen as highly improbable. Bishop George was slain by Gentile Greeks for exacting onerous taxes, especially inheritance taxes. J. B. Bury, who edited the 1906 edition of Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall, wrote «this theory of Gibbon’s has nothing to be said for it». He adds that: «the connection of St. George with a dragon-slaying legend does not relegate him to the region of the myth».[21] Saint George in all likelihood was martyred before the year 290.[26]

St. George and the dragon[edit]

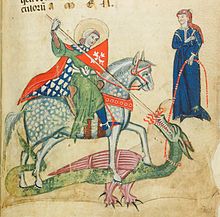

Miniature from a 13th-century Passio Sancti Georgii (Verona)

The legend of Saint George and the Dragon was first recorded in the 11th century, in a Georgian source.[27]

It reached Catholic Europe in the 12th century. In the Golden Legend, by 13th-century Archbishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine, George’s death was at the hands of Dacian, and about the year 287.[citation needed]

The tradition tells that a fierce dragon was causing panic at the city of Silene, Libya, at the time George arrived there. In order to prevent the dragon from devastating people from the city, they gave two sheep each day to the dragon, but when the sheep were not enough they were forced to sacrifice humans instead of the two sheep. The human to be sacrificed was elected by the city’s own people and one time the king’s daughter was chosen to be sacrificed but no one was willing to take her place. George saved the girl by slaying the dragon with a lance. The king was so grateful that he offered him treasures as a reward for saving his daughter’s life, but George refused it and instead he gave these to the poor. The people of the city were so amazed at what they had witnessed that they became Christians and were all baptized.[28]

The Golden Legend offered a narration of George’s encounter with a dragon.

This account was very influential and it remains the most familiar version in English owing to William Caxton’s 15th-century translation.[29]

In the medieval romances, the lance with which George slew the dragon was called Ascalon, after the Levantine city of Ashkelon, today in Israel. The name Ascalon was used by Winston Churchill for his personal aircraft during World War II, according to records at Bletchley Park.[30] Iconography of the horseman with spear overcoming evil was widespread throughout the Christian period.[31]

[edit]

George (Arabic: جرجس, Jirjis or Girgus) is included in some Muslim texts as a prophetic figure. The Islamic sources state that he lived among a group of believers who were in direct contact with the last apostles of Jesus. He is described as a rich merchant who opposed erection of Apollo’s statue by Mosul’s king Dadan. After confronting the king, George was tortured many times to no effect, was imprisoned and was aided by the angels. Eventually, he exposed that the idols were possessed by Satan, but was martyred when the city was destroyed by God in a rain of fire.[32]

Muslim scholars had tried to find a historical connection of the saint due to his popularity.[33] According to Muslim legend, he was martyred under the rule of Diocletian and was killed three times but resurrected every time. The legend is more developed in the Persian version of al-Tabari wherein he resurrects the dead, makes trees sprout and pillars bear flowers. After one of his deaths, the world is covered by darkness which is lifted only when he is resurrected. He is able to convert the queen but she is put to death. He then prays to God to allow him to die, which is granted.[34]

Al-Thaʿlabi states that he was from Palestine and lived in the times of some disciples of Jesus. He was killed many times by the king of Mosul, and resurrected each time. When the king tried to starve him, he touched a piece of dry wood brought by a woman and turned it green, with varieties of fruits and vegetables growing from it. After his fourth death, the city was burnt along with him. Ibn al-Athir’s account of one of his deaths is parallel to the crucifixion of Jesus, stating, «When he died, God sent stormy winds and thunder and lightning and dark clouds, so that darkness fell between heaven and earth, and people were in great wonderment.» The account adds that the darkness was lifted after his resurrection.[33]

Veneration[edit]

History[edit]

A titular church built in Lydda during the reign of Constantine the Great (reigned 306–337) was consecrated to «a man of the highest distinction», according to the church history of Eusebius; the name of the titulus «patron» was not disclosed, but later he was asserted[by whom?] to have been George.

The veneration of George spread from Syria Palaestina through Lebanon to the rest of the Byzantine Empire – though the martyr is not mentioned in the Syriac Breviarium[19] – and the region east of the Black Sea.

By the 5th century, the veneration of George had reached the Christian Western Roman Empire, as well: in 494, George was canonized as a saint by Pope Gelasius I, among those «whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to [God].»[citation needed]

The early cult of the saint was localized in Diospolis (Lydda), in Palestine.

The first description of Lydda as a pilgrimage site where George’s relics were venerated is De Situ Terrae Sanctae by

the archdeacon Theodosius, written between 518 and 530.

By the end of the 6th century, the center of his veneration appears to have shifted to Cappadocia.

The Life of Saint Theodore of Sykeon, written in the 7th century, mentions the veneration of the relics of the saint in Cappadocia.[35]

By the time of the early Muslim conquests of the mostly Christian and Zoroastrian Middle East, a basilica in Lydda dedicated to George existed.[36] A new church was erected in 1872 and is still standing, where the feast of the translation of the relics of Saint George to that location is celebrated on 3 November each year.[37] In England, he was mentioned among the martyrs by the 8th-century monk Bede. The Georgslied is an adaptation of his legend in Old High German, composed in the late 9th century. The earliest dedication to the saint in England is a church at Fordington, Dorset, that is mentioned in the will of Alfred the Great.[38] George did not rise to the position of «patron saint» of England, however, until the 14th century, and he was still obscured by Edward the Confessor, the traditional patron saint of England, until in 1552 during the reign of Edward VI all saints’ banners other than George’s were abolished in the English Reformation.[39][40]

Belief in an apparition of George heartened the Franks at the Battle of Antioch in 1098,[41] and a similar appearance occurred the following year at Jerusalem. The chivalric military Order of Sant Jordi d’Alfama was established by king Peter the Catholic from the Crown of Aragon in 1201, Republic of Genoa, Kingdom of Hungary (1326), and by Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor.[42] Edward III of England put his Order of the Garter under the banner of George, probably in 1348. The chronicler Jean Froissart observed the English invoking George as a battle cry on several occasions during the Hundred Years’ War. In his rise as a national saint, George was aided by the very fact that the saint had no legendary connection with England, and no specifically localized shrine, as that of Thomas Becket at Canterbury: «Consequently, numerous shrines were established during the late fifteenth century,» Muriel C. McClendon has written,[43] «and his did not become closely identified with a particular occupation or with the cure of a specific malady.»

In the wake of the Crusades, George became a model of chivalry in works of literature, including medieval romances. In the 13th century, Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, compiled the Legenda Sanctorum, (Readings of the Saints) also known as Legenda Aurea (the Golden Legend). Its 177 chapters (182 in some editions) include the story of George, among many others. After the invention of the printing press, the book became a bestseller.

The establishment of George as a popular saint and protective giant[44] in the West, that had captured the medieval imagination, was codified by the official elevation of his feast to a festum duplex[45] at a church council in 1415, on the date that had become associated with his martyrdom, 23 April. There was wide latitude from community to community in celebration of the day across late medieval and early modern England,[46] and no uniform «national» celebration elsewhere, a token of the popular and vernacular nature of George’s cultus and its local horizons, supported by a local guild or confraternity under George’s protection, or the dedication of a local church. When the English Reformation severely curtailed the saints’ days in the calendar, Saint George’s Day was among the holidays that continued to be observed.

In April 2019, the parish church of São Jorge, in São Jorge, Madeira Island, Portugal, solemnly received the relics of George, patron saint of the parish. During the celebrations the 504th anniversary of its foundation. the relics were brought by the new Bishop of Funchal, D. Nuno Brás.[47]

Veneration in the Levant[edit]

George is renowned throughout the Middle East, as both saint and prophet. His veneration by Christians and Muslims lies in his composite personality combining several biblical, Quranic and other ancient mythical heroes.[48] Saint George is the patron saint of Lebanese Christians,[49] Palestinian Christians,[50] and Syrian Christians.[51]

Saint George dragged through the streets (detail), by Bernat Martorell, 15th century

William Dalrymple, who reviewed the literature in 1999, tells us that J. E. Hanauer in his 1907 book Folklore of the Holy Land: Muslim, Christian and Jewish «mentioned a shrine in the village of Beit Jala, beside Bethlehem, which at the time was frequented by Christians who regarded it as the birthplace of George and some Jews who regarded it as the burial place of the Prophet Elias. According to Hanauer, in his day the monastery was «a sort of madhouse. Deranged persons of all the three faiths are taken thither and chained in the court of the chapel, where they are kept for forty days on bread and water, the Eastern Orthodox priest at the head of the establishment now and then reading the Gospel over them, or administering a whipping as the case demands.»[52] In the 1920s, according to Tawfiq Canaan’s Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine, nothing seemed to have changed, and all three communities were still visiting the shrine and praying together.»[53]

Dalrymple himself visited the place in 1995. «I asked around in the Christian Quarter in Jerusalem, and discovered that the place was very much alive. With all the greatest shrines in the Christian world to choose from, it seemed that when the local Arab Christians had a problem – an illness, or something more complicated – they preferred to seek the intercession of George in his grubby little shrine at Beit Jala rather than praying at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem or the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.»[53] He asked the priest at the shrine «Do you get many Muslims coming here?» The priest replied, «We get hundreds! Almost as many as the Christian pilgrims. Often, when I come in here, I find Muslims all over the floor, in the aisles, up and down.»[53][54]

The Encyclopædia Britannica quotes G. A. Smith in his Historic Geography of the Holy Land, p. 164, saying: «The Mahommedans who usually identify St. George with the prophet Elijah, at Lydda confound his legend with one about Christ himself. Their name for Antichrist is Dajjal, and they have a tradition that Jesus will slay Antichrist by the gate of Lydda. The notion sprang from an ancient bas-relief of George and the Dragon on the Lydda church. But Dajjal may be derived, by a very common confusion between n and l, from Dagon, whose name two neighbouring villages bear to this day, while one of the gates of Lydda used to be called the Gate of Dagon.»[55]

Veneration in the Muslim world[edit]

George is described as a prophetic figure in Islamic sources.[32] George is venerated by some Christians and Muslims because of his composite personality combining several biblical, Quranic and other ancient mythical heroes.[citation needed] In some sources he is identified with Elijah or Mar Elis, George or Mar Jirjus and in others as al-Khidr. The last epithet meaning the «green prophet», is common to Christian, Muslim, and Druze folk piety. Samuel Curtiss who visited an artificial cave dedicated to him where he is identified with Elijah, reports that childless Muslim women used to visit the shrine to pray for children. Per tradition, he was brought to his place of martyrdom in chains, thus priests of Church of St. George chain the sick especially the mentally ill to a chain for overnight or longer for healing. This is sought after by both Muslims and Christians.[48]

According to Elizabeth Anne Finn’s Home in the Holy land (1866):[57]

St George killed the dragon in this country; and the place is shown close to Beyroot. Many churches and convents are named after him. The church at Lydda is dedicated to George; so is a convent near Bethlehem, and another small one just opposite the Jaffa gate, and others beside. The Arabs believe that George can restore mad people to their senses, and to say a person has been sent to St. George’s is equivalent to saying he has been sent to a madhouse. It is singular that the Moslem Arabs adopted this veneration for St George, and send their mad people to be cured by him, as well as the Christians, but they commonly call him El Khudder – The Green

– according to their favourite manner of using epithets instead of names. Why he should be called green, however, I cannot tell – unless it is from the colour of his horse. Gray horses are called green in Arabic.

The mosque of Nabi Jurjis, which was restored by Timur in the 14th century, was located in Mosul and supposedly contained the tomb of George.[58] It was however destroyed in July 2014 by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, who also destroyed the Mosque of the Prophet Sheeth (Seth) and the Mosque of the Prophet Younis (Jonah). The militants claim such mosques have become places for apostasy instead of prayer.[59]

George or Hazrat Jurjays was the patron saint of Mosul. Along with Theodosius, he was revered by both Christian and Muslim communities of Jazira and Anatolia. The wall paintings of Kırk Dam Altı Kilise at Belisırma dedicated to him are dated between 1282 and 1304. These paintings depict him as a mounted knight appearing between donors including a Georgian lady called Thamar and her husband, the Emir and Consul Basil, while the Seljuk Sultan Mesud II and Byzantine Emperor Androncius II are also named in the inscriptions.[60]

A shrine attributed to prophet George can be found in Diyarbakir, Turkey. Evliya Çelebi states in his Seyahatname that he visited the tombs of prophet Jonah and prophet George in the city.[61][62]

Feast days[edit]

In the General Roman Calendar, the feast of George is on 23 April. In the Tridentine Calendar of 1568, it was given the rank of «Semidouble». In Pope Pius XII’s 1955 calendar this rank was reduced to «Simple», and in Pope John XXIII’s 1960 calendar to a «Commemoration». Since Pope Paul VI’s 1969 revision, it appears as an «optional memorial». In some countries such as England, the rank is higher – it is a Solemnity (Roman Catholic) or Feast (Church of England): if it falls between Palm Sunday and the Second Sunday of Easter inclusive, it is transferred to the Monday after the Second Sunday of Easter.[63]

George is very much honoured by the Eastern Orthodox Church, wherein he is referred to as a «Great Martyr», and in Oriental Orthodoxy overall. His major feast day is on 23 April (Julian calendar 23 April currently corresponds to Gregorian calendar 6 May). If, however, the feast occurs before Easter, it is celebrated on Easter Monday, instead. The Russian Orthodox Church also celebrates two additional feasts in honour of George. One is on 3 November, commemorating the consecration of a cathedral dedicated to him in Lydda during the reign of Constantine the Great (305–37). When the church was consecrated, the relics of George were transferred there. The other feast is on 26 November for a church dedicated to him in Kiev, c. 1054.

In Bulgaria, George’s day (Bulgarian: Гергьовден) is celebrated on 6 May, when it is customary to slaughter and roast a lamb. George’s day is also a public holiday.

In Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbian Orthodox Church refers to George as Sveti Djordje (Свети Ђорђе) or Sveti Georgije (Свети Георгије). George’s day (Đurđevdan) is celebrated on 6 May, and is a common slava (patron saint day) among ethnic Serbs.

In Egypt, the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria refers to George (Coptic: Ⲡⲓⲇⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲅⲉⲟⲣⲅⲓⲟⲥ or ⲅⲉⲱⲣⲅⲓⲟⲥ) as the «Prince of Martyrs» and celebrates his martyrdom on the 23rd of Paremhat of the Coptic calendar, equivalent to 1 May.[citation needed]

The Copts also celebrate the consecration of the first church dedicated to him on the seventh of the month of Hatour of the Coptic calendar usually equivalent to 17 November.

In India, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, one of the oriental catholic churches (Eastern Catholic Churches), and Malankara Orthodox Church venerate George. The main pilgrim centers of the saint in India are at Aruvithura and Puthuppally in Kottayam District, Edathua[64] in Alappuzha district, and Edappally[65] in Ernakulam district of the southern state of Kerala. The saint is commemorated each year from 27 April to 14 May at Edathua.[66] On 27 April after the flag hoisting ceremony by the parish priest, the statue of the saint is taken from one of the altars and placed at the extension of the church to be venerated by devotees till 14 May. The main feast day is 7 May, when the statue of the saint along with other saints is taken in procession around the church. Intercession to George of Edathua is believed to be efficacious in repelling snakes and in curing mental ailments. The sacred relics of George were brought to Antioch from Mardin in 900 and were taken to Kerala, India, from Antioch in 1912 by Mar Dionysius of Vattasseril and kept in the Orthodox seminary at Kundara, Kerala. H.H. Mathews II Catholicos had given the relics to St. George churches at Puthupally, Kottayam District, and Chandanappally, Pathanamthitta district.

George is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 23 April.[67]

Catholic Church feast days:

- 23 April – main commemoration,[68]

- 24 April – commemoration in Poland,[69] (23 April – commemoration of Saint Wojciech)[70]

- 7 May – martyrdom in Lydda,[71]

- 20 June – commemoration of translation of relics to Anchin Abbey,[72]

- 15 October – commemoration of translation of relics to Toulouse,[72]

Eastern Orthodox Church feast days:[73]

- 27 January – Commemoration of the Miracle (deliverance of the island of Zakynthos from the plague) of the Great Martyr George in Zakynthos in 1689/1688. (Greek Orthodox Church)[74]

- 12 April – Gerontius from Cappadocia, martyr, father of George, husband of Polychronia (c.290)[75]

- 23 April – Holy Glorious Great-martyr, Victory-bearer and Wonderworker George (303) [Death anniversary]

- 23 April – Polychronia from Cappadocia, martyr, mother of George, wife of Gerontius (303/304)[76]

- 6 May – George’s Day in Spring [BOC]

- 3 November – Dedication of the Church of the Great-martyr George in Lydda (4th century)

- 10 November – Commemoration of the torture of Great-martyr George in 303 [GOC][77][78]

- 23 November – Dedication of the Church of St. George at Kiev (1051)

Patronages[edit]

George is a highly celebrated saint in both the Western and Eastern Christian churches, and many Patronages of Saint George exist throughout the world.[79]

George is the patron saint of England. His cross forms the national flag of England, which also (through the structure of England and Wales) represents Wales within the Union Flag of the United Kingdom and other national flags containing the Union Flag, such as those of Australia and New Zealand. By the 14th century, the saint had been declared both the patron saint and the protector of the royal family.[80]

George has been the patron saint of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the medieval times until 26 August 1752, when he was replaced by Elijah at the request of a Bosnian Franciscan friar, Bishop Pavao Dragičević. The reasons for the replacement are unclear. It has been suggested that Elijah was chosen because of his importance to all three main religious groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina—Catholics, Muslims and Orthodox Christians. Pope Benedict XIV is said to have approved Bishop Dragičević’s request with the remark that «a wild nation deserved a wild patron».[81][82]

George is the patron saint of Ethiopia.[83] He is also the patron saint of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church; George slaying the dragon is one of the most frequently used subjects of icons in the church.[84]

Monument dedicated to St George in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi

The country of Georgia, where devotions to the saint date back to the fourth century, is not technically named after the saint, but is a well-attested back-formation of the English name. However, many towns and cities around the world are. George is one of the patron saints of Georgia. Exactly 365 Orthodox churches in Georgia are named after George according to the number of days in a year. According to legend, George was cut into 365 pieces after he fell in battle and every single piece was spread throughout the entire country.[85][86][87]

George is also one of the patron saints of the Mediterranean islands of Malta and Gozo.[88] In a battle between the Maltese and the Moors, George was alleged to have been seen with Saint Paul and Saint Agata, protecting the Maltese. George is the protector of the island of Gozo and the patron of Gozo’s largest city, Victoria. The St. George’s Basilica in Victoria is dedicated to him.[89]

English recruitment poster from World War I, featuring George and the Dragon

Devotions to George in Portugal date back to the 12th century. Nuno Álvares Pereira attributed the victory of the Portuguese in the battle of Aljubarrota in 1385 to George. During the reign of John I of Portugal (1357–1433), George became the patron saint of Portugal and the King ordered that the saint’s image on the horse be carried in the Corpus Christi procession. The flag of George (white with red cross) was also carried by the Portuguese troops and hoisted in the fortresses, during the 15th century. «Portugal and Saint George» became the battle cry of the Portuguese troops, being still today the battle cry of the Portuguese Army, with simply «Saint George» being the battle cry of the Portuguese Navy.[90]

Devotions to Saint George in Brazil was influenced by the Portuguese colonization. George is the unofficial patron saint of the city of Rio de Janeiro (title officially attributed to Saint Sebastian) and of the city of São Jorge dos Ilhéus (Saint George of Ilhéus). Additionally, George is the patron saint of Scouts and of the Cavalry of the Brazilian Army. In May 2019, he was made official as the patron saint of the State of Rio de Janeiro, next to Saint Sebastian.[91] George is also revered in several Afro-Brazilian religions, such as Umbanda, where it is syncretized in the form of Ogum. However, the connection of George with the Moon is purely Brazilian, with a strong influence of African culture, and in no way related to the European saint. Tradition says that the spots at the Moon’s surface represent the miraculous saint, his horse and his sword slaying the dragon and ready to defend those who seek his help.[92]

George, is also the patron saint of the region of Aragon, in Spain, where his feast day is celebrated on 23 April and is known as «Aragon Day», or ‘Día de Aragón’ in Spanish. He became the patron saint of the former Kingdom of Aragon and Crown of Aragon when King Pedro I of Aragon won the Battle of Alcoraz in 1096. Legend has it that victory eventually fell to the Christian armies when George appeared to them on the battlefield, helping them secure the reconquest of the city of Huesca which had been under the Muslim control of the Taifa of Zaragoza. The battle, which had begun two years earlier in 1094, was long and arduous, and had also taken the life of King Pedro’s own father, King Sancho Ramirez. With the Aragonese spirits flagging, it is said that George descending from heaven on his charger and bearing a dark red cross, appeared at the head of the Christian cavalry leading the knights into battle. Interpreting this as a sign of protection from God, the Christian militia returned emboldened to the battle field, more energized than ever, convinced theirs was the banner of the one true faith. Defeated, the moors rapidly abandoned the battlefield. After two years of being locked down under siege, Huesca was liberated and King Pedro made his triumphal entry into the city. To celebrate this victory, the cross of St. George was adopted as the personal coat of arms of Huesca and Aragon, in honour of their saviour. After the taking of Huesca, King Pedro aided the military leader and nobleman, Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, otherwise known as El Cid, with a coalition army from Aragon in the long reconquest of the Kingdom of Valencia.

Tales of King Pedro’s success at Huesca and in leading his expedition of armies with El Cid against the Moors, under the auspices of George on his standard, spread quickly throughout the realm and beyond the Crown of Aragon, and Christian armies throughout Europe quickly began adopting George as their protector and patron, during all subsequent Crusades to the Holy Lands. By 1117, the military order of Templars adopted the Cross of St. George as a simple, unifying sign for international Christian militia embroidered on the left hand side of their tunics, placed above the heart.

The Cross of St. George, also known in Aragon as The Cross of Alcoraz, continues to emblazon the flags of all of Aragon’s provinces.

The association of St. George with chivalry and noblemen in Aragon continued through the ages. Indeed, even the author Miguel de Cervantes, in his book on the adventures of Don Quixote, also mentions the jousting events that took place at the festival of St. George in Zaragoza in Aragon where one could gain international renown in winning a joust against any of the knights of Aragon.

In Valencia, Catalonia, the Balearics, Malta, Sicily and Sardinia, the origins of the veneration of St. George go back to their shared history as territories under the Crown of Aragon, thereby sharing the same legend.

One of the highest civil distinctions awarded in Catalonia is the St. George’s Cross (Creu de Sant Jordi). The Sant Jordi Awards have been awarded in Barcelona since 1957.

Saint George (Sant Jordi in Catalan) is also the patron saint of Catalonia. His cross appears in many buildings and local flags, including the flag of Barcelona, the Catalan capital. A Catalan variation to the traditional legend places George’s life story as having occurred in the town of Montblanc, near Tarragona.

In 1469, the Order of St. George (Habsburg-Lorraine) was founded in Rome by Emperor Friedrich III of Habsburg in the presence of Pope Paul II in honor of Saint George. The order was continued and promoted by his son, Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg. The later history of the order was eventful, in particular the order was dissolved by Nazi Germany. Only after the fall of the Iron Curtain and the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe was the order reactivated as a European association in association with Saint George by the Habsburg family.[93][94][95]

Arms and flag[edit]

It became fashionable in the 15th century, with the full development of classical heraldry, to provide attributed arms to saints and other historical characters from the pre-heraldic ages. The widespread attribution to George of the red cross on a white field in Western art – «Saint George’s Cross» – probably first arose in Genoa, which had adopted this image for their flag and George as their patron saint in the 12th century. A vexillum beati Georgii is mentioned in the Genovese annals for the year 1198, referring to a red flag with a depiction of George and the dragon. An illumination of this flag is shown in the annals for the year 1227. The Genoese flag with the red cross was used alongside this «George’s flag», from at least 1218, and was known as the insignia cruxata comunis Janue («cross ensign of the commune of Genoa»). The flag showing the saint himself was the city’s principal war flag, but the flag showing the plain cross was used alongside it in the 1240s.[96]

In 1348 Edward III of England chose George as the patron saint of his Order of the Garter, and also took to using a red-on-white cross in the hoist of his Royal Standard.

The term «Saint George’s cross» was at first associated with any plain Greek cross touching the edges of the field (not necessarily red on white).[97] Thomas Fuller in 1647 spoke of «the plain or St George’s cross» as «the mother of all the others» (that is, the other heraldic crosses).[98]

Iconography[edit]

George is most commonly depicted in early icons, mosaics, and frescos wearing armour contemporary with the depiction, executed in gilding and silver colour, intended to identify him as a Roman soldier. Particularly after the Fall of Constantinople and George’s association with the crusades, he is often portrayed mounted upon a white horse. Thus, a 2003 Vatican stamp (issued on the anniversary of the Saint’s death) depicts an armoured George atop a white horse, killing the dragon.[99]

Eastern Orthodox iconography also permits George to ride a black horse, as in a Russian icon in the British museum collection.[100]

In the south Lebanese village of Mieh Mieh, the Saint George Church for Melkite Catholics commissioned for its 75th jubilee in 2012 (under the guidance of Mgr Sassine Gregoire) the only icons in the world portraying the whole life of George, as well as the scenes of his torture and martyrdom (drawn in eastern iconographic style).[101]

George may also be portrayed with Saint Demetrius, another early soldier saint. When the two saintly warriors are together and mounted upon horses, they may resemble earthly manifestations of the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Eastern traditions distinguish the two as George rides a white horse and Demetrius a red horse (the red pigment may appear black if it has bituminized).

George can also be identified by his spearing a dragon, whereas Demetrius may be spearing a human figure, representing Maximian.

Gallery[edit]

- Eastern

-

Main icon of Yuriev Monastery in Novgorod (c. 1130)

-

A plaque, on which is represented George rescuing the emperor’s daughter (15th century)

- Western

-

George as a crusader knight, miniature from a ms. of Vies de Saints, c. 1340 (BNF Richelieu Manuscrits Français 185)

-

Miniature of George and the Dragon, ms. of the Legenda Aurea, dated 1348 (BNF Français 241, fol. 101v.)

-

Miniature of George and the Dragon, ms. of the Legenda Aurea, Paris, 1382 (BL Royal 19 B XVII, f. 109).

-

George on a small pavise (Nuremberg, c. 1480)

-

-

-

See also[edit]

- Saint George’s Day

- Saint Andrew

- «St. George and the Dragon», a 17th-century ballad comparing the myth of George to that of other heroes

- Dragon Hill, Uffington, English hill named due to a legend that George slew the dragon there

- Fort St George, an English-built fort in Chennai, India

- «Georgslied«, 9th-century Old High German poem about the life of George

- «Georgslegende«, 13th-century Middle High German poem about the martyrdom of George

- Ederlezi, song and Romani name for the Bulgarian, Macedonian and Serbian Feast of Saint George

- Knights of St George

- Uastyrdzhi, Ossetian name for George

- Tetri Giorgi, Georgian name for George

- Moors and Christians of Alcoy, an international historical festival dedicated to George in Alcoy (Alicante), Spain

- The Magic Sword, a 1962 film loosely based on the legend of St George and the Dragon

- Patrick Woodroffe, author of several poems about St George collated in a book called Hallelujah Anyway

- St George’s Church, churches dedicated to St George

- St George’s School, schools dedicated to St George

- St George’s College, colleges dedicated to St George

- St George’s Castle, castles dedicated to St George

- St George’s Hospital, hospitals dedicated to St George

- Ribbon of St. George, ribbon dedicated to St George

- George (given name)

- Joris en de Draak, a roller coaster in the theme park Efteling based on the legend of St George and the dragon

- Order of St. George (Habsburg-Lorraine)

References[edit]

- ^ «Saint George». Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ «St. George». Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome (2008). The Holy Land: An Oxford Archaeological Guide from Earliest Times to 1700. OUP Oxford. p. 205. ISBN 9780191647666.

- ^ Otto Friedrich August Meinardus, Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity (1999), p. 315 Archived 13 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Domar: the calendrical and liturgical cycle of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church, Armenian Orthodox Theological Research Institute, 2002, p. 504-5

- ^ G. Massiot. «Church of Saint George, Lod: Interior, view of the nave from the southeast end». CurateND. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ «Who was Saint George and why is he England’s patron saint?». The Independent. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Acta Sanctorum, Volume 12, as republished in 1866

- ^ Church History (Eusebius), book 8, chapter 5; Greek text here Archived 14 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine, and English text here Archived 14 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Eusebius’s full text as follows:

Immediately on the publication of the decree against the churches in Nicomedia, a certain man, not obscure but very highly honored with distinguished temporal dignities, moved with zeal toward God, and incited with ardent faith, seized the edict as it was posted openly and publicly, and tore it to pieces as a profane and impious thing; and this was done while two of the sovereigns were in the same city,—the oldest of all, and the one who held the fourth place in the government after him. But this man, first in that place, after distinguishing himself in such a manner suffered those things which were likely to follow such daring, and kept his spirit cheerful and undisturbed till death.

- ^ Walter, Christopher (2003), The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition, Ashgate Publishing, p. 110, ISBN 1-84014-694-X.

Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca 271, 272. - ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «George, Saint» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 737.

In the canon of Pope Gelasius (494) George is mentioned in a list of those ‘whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose acts are known only to God’

- ^ Cross, Frank; Livingstone, Elizabeth, eds. (1957). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2005 ed.). pp. 667–668.

- ^ Brooks, Ernest W. (1925). «Acts of S. George». Le Muséon. 38: 67–115. ISSN 0771-6494., online here.

- ^ Collins, Michael (2012). «3 The Greek and Latin traditions». St George and the dragons: the making of English identity. Fonthill. ISBN 978-1-78155-649-8.

- ^ a b Guiley, Rosemary (2001). The Encyclopedia of Saints. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4381-3026-2.

George was an historical figure. According to an account by Metaphrastes, he was born in Cappadocia (in modern Turkey) to a noble Christian family; his mother was Palestinian.

- ^ Heylin, A. (1862), The Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record, vol. 1, p. 244. Darch, John H (2006), Saints on Earth, Church House Press, p. 56, ISBN 978-0-7151-4036-9. Walter, Christopher (2003), The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition, Ashgate Publishing, p. 112, ISBN 1-84014-694-X.

- ^ a b «Saint George», Catholic Encyclopedia,

it is not improbable that the apocryphal Acts have borrowed some incidents from the story of the Arian bishop

. - ^ Hackwood, Fred (2003), Christ Lore the Legends, Traditions, Myths, Kessinger Publishing, p. 255, ISBN 0-7661-3656-6.

- ^ a b Butler, Alban (2008), Lives of the Saints, ISBN 978-1-4375-1281-6.: 166

- ^ Michael Collins, St George and the Dragons: The Making of English Identity (2018), p. 129 Archived 13 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Thurston, Herbert (1913). «St. George» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. «There seems, therefore, no ground for doubting the historical existence of St. George, even though he is not commemorated in the Syrian, or in the primitive Hieronymian Martyrologium, but no faith can be placed in the attempts that have been made to fill up any of the details of his history. For example, it is now generally admitted that St. George cannot safely be identified by the nameless martyr spoken of by Eusebius (Church History VIII.5), who tore down Diocletian’s edict of persecution at Nicomedia. The version of the legend in which Diocletian appears as persecutor is not primitive. Diocletian is only a rationalized form of the name Dadianus. Moreover, the connection of the saint’s name with Nicomedia is inconsistent with the early cultus at Diospolis. Still less is St. George to be considered, as suggested by Gibbon, Vetter, and others, a legendary double of the disreputable bishop, George of Cappadocia, the Arian opponent of St. Athanasius.»

- ^ Attwater, Donald (1995) [1965]. Dictionary of Saints (Third ed.). London: Penguin Reference. p. 152.

- ^ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 2:23:5

- ^ Richardson, Robert D.; Moser, Barry, eds. (1996), Emerson, p. 520,

George of Cappadocia … [held] the contract to supply the army with bacon … embraced Arianism … [and was] promoted … to the episcopal throne of Alexandria … When Julian came, George was dragged to prison, the prison was burst open by a mob, and George was lynched … [he] became in good time Saint George of England

. - ^ Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, 2:23:5

- ^ Hogg, John (1863), «Supplemental Notes on St George the Martyr, and on George the Arian Bishop», Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom, Royal Society of Literature: 106–136

- ^ «St. George and the Dragon: Introduction». Robbins Library Digital Projects. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Pirlo, Paolo O. (1997). «St. George». My first book of saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate – Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 83–85. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.

- ^ De Voragine, Jacobus (1995), The Golden Legend, Princeton University Press, p. 238, ISBN 978-0-691-00153-1.

- ^ «Getting There: Churchill’s Wartime Journeys». The International Churchill Society. 1 May 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ Charles Clermont-Ganneau, «Horus et Saint Georges, d’après un bas-relief inédit du Louvre». Revue archéologique, 1876

- ^ a b Scott B. Noegel, Brannon M. Wheeler (April 2010). The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-4617-1895-6.

- ^ a b H. S. Haddad (1968). «‘Georgic’ Cults and Saints of the Levant». Numen. Brill: 37.

- ^ Bernard Carra de Vaux. P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C. E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W. P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. I, Part 2 (Second ed.). Brill. p. 1047.

- ^ Christopher Walter, «The Origins of the Cult of Saint George», Revue des études byzantines 53 (1995), 295–326 (p. 296) (persee.fr Archived 28 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Pringle, Denys (1998), The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press, p. 25, ISBN 0-521-39037-0.

- ^ Eastern Christian Publications, Theosis: Calendar of Saints (2020), pp. 75-76.

- ^ Samantha Riches, St. George: Hero, Martyr and Myth (Sutton, 2000), ISBN 0750924527, p. 19.

- ^ McClendon 1999, p .6

- ^ Perrin, British Flags, 1922, p. 38.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1951–1952). A History of the Crusades I: The First Crusade. Penguin Classics. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-14-198550-3.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia 1913, s.v. «Orders of St. George» Archived 22 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine omits Genoa and Hungary: see David Scott Fox, Saint George: The Saint with Three Faces (1983:59–63, 98–123), noted by McClellan 999:6 note 13. Additional Orders of St. George were founded in the eighteenth century (Catholic Encyclopedia).

- ^ McClendon 1999:10.

- ^ Desiderius Erasmus, in The Praise of Folly (1509, printed 1511) remarked «The Christians have now their gigantic St. George, as well as the pagans had their Hercules.»

- ^ Only the most essential work might be done on a festum duplex

- ^ Muriel C. McClendon, «A Moveable Feast: Saint George’s Day Celebrations and Religious Change in Early Modern England» The Journal of British Studies 38.1 (January 1999:1–27).

- ^ Gonçalves, Luisa (29 April 2019). «D. Nuno Brás presidiu à Festa em honra de São Jorge». Jornal da Madeira (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ a b Religion and Culture in Medieval Islam by Richard G. Hovannisian, Georges Sabagh (2000) ISBN 0-521-62350-2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 109–110

- ^ History Project, Christian (2003). By this Sign: A.D. 250 to 350 : from the Decian Persecution to the Constantine Era. Christian History Project. p. 44. ISBN 9780968987322.

St. George is also the patron saint of Lebanese and Palestinian Christians.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2021). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. p. 334. ISBN 9781598842050.

He is also the patron saint of the Palestinian Christian community.

- ^ S. Hassan, Wail (2014). Immigrant Narratives: Orientalism and Cultural Translation in Arab American and Arab British Literature. Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780199354979.

There are several examples of this: “Besides being the patron saint of England and of the Christians of Syria.

- ^ Hanauer, JE (1907). «Folk-lore of the Holy Land, Moslem, Christian and Jewish». Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ a b c William Dalrymple (1999). From the Holy Mountain: a journey among the Christians of the Middle East. Owl Books.[ISBN missing]

- ^ H. S. Haddad (1969). ««Georgic» Cults and Saints of the Levant». Numen. 16 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1163/156852769X00029. JSTOR 3269569.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «George, Saint» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 737.

- ^ Ferg, Erica (2020). Geography, Religion, Gods, and Saints in the Eastern Mediterranean. Routledge. p. 197-200. ISBN 9780429594496.

- ^ Elizabeth Anne Finn (1866). Home in the Holyland. London: James Nisbet and Co. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. I.B. Tauris. 5 March 2014. p. 525. ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1.

- ^ «Islamic militants destroy historic 14th century mosque in Mosul». The Telegraph. 28 July 2014. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Teresa Fitzherbert (5 October 2006). «Religious Diversity Under Ilkhanid Rule». In Linda Komaroff (ed.). Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan. Brill. p. 402. ISBN 9789047418573.

- ^ «EVLİYA ÇELEBİ NİN SEYAHATNAME SİNDE DİYARBAKIR* DIYARBAKIR IN EVLIYA ÇELEBI S SEYAHATNAME — PDF Ücretsiz indirin». docplayer.biz.tr. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ EVLİYA ÇELEBİ DİYARBAKIR’DA (Turkish) Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine TigrisHaber. Posted 22 July 2014.

- ^ The Divine Office: Table of Liturgical Days, Section I (RC) and Calendar, Lectionary and Collects (Church House Publishing 1997) p. 12 (C of E)

- ^ B, Sathish (20 March 2008). «St. George forane church Edathua-689573». Edathuapalli. Sathish B. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ «St. George forane church Edappally». Edappally. St: George Church. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ «Arrangements for Edathua church fete». The Hindu. Alappuzha. 3 April 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ «The Calendar». The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ popadmin (25 March 2021). «23 April: Feast of Saint George — Prince of Peace Catholic Church & School». Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ «24 kwietnia: św. Jerzego, męczennika». ordo.pallotyni.pl. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ «23 kwietnia: św. Wojciecha, biskupa i męczennika, głównego patrona Polski». ordo.pallotyni.pl. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ «Georg der Märtyrer — Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon». www.heiligenlexikon.de (in German). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ a b «Georg der Märtyrer — Ökumenisches Heiligenlexikon». www.heiligenlexikon.de (in German). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ «ГЕОРГИЙ ПОБЕДОНОСЕЦ — Древо». drevo-info.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «Ο Τροπαιοφόρος και η πανούκλα». Εφημερίδα Ημέρα, Ζάκυνθος. (in Greek). 31 January 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «ГЕРОНТИЙ КАППАДОКИЙСКИЙ — Древо». drevo-info.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «ПОЛИХРОНИЯ КАППАДОКИЙСКАЯ — Древо». drevo-info.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «КОЛЕСОВАНИЕ ВЕЛИКОМУЧЕНИКА ГЕОРГИЯ — Древо». drevo-info.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ «Воспоминание колесования великомученика Георгия Победоносца (Груз.) — Храм великомученицы Ирины» (in Russian). Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ Seal, Graham (2001), Encyclopedia of folk heroes, p. 85, ISBN 1-57607-216-9.

- ^ Hinds, Kathryn (2001), Medieval England, Marshall Cavendish, p. 44, ISBN 0-7614-0308-6.

- ^ Skoko, Iko (21 August 2012). «Sveti Ilija – zaštitnik Bosne i Hercegovine» (in Serbo-Croatian). Večernji list.

- ^ Martić, Zvonko (2014). «Sveti Jure i sveti Ilija u pučkoj pobožnosti katolika u Bosni i Hercegovini» (in Serbo-Croatian). Svjetlo riječi. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ^ «Saint George, Patron Saint of Ethiopia». Horniman Museum and Gardens. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Fargher, Brian L. (1996). The Origins of the New Churches Movement in Southern Ethiopia: 1927–1944. Brill. ISBN 978-9004106611.

- ^ Gabidzashvili, Enriko (1991), Saint George: In Ancient Georgian Literature, Tbilisi, Georgia: Armazi – 89.

- ^ Foakes-Jackson, FJ (2005), A History of the Christian Church, Cosimo, p. 556, ISBN 1-59605-452-2.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (1998), Royal Imagery in Medieval Georgia, Penn State Press, p. 119, ISBN 0-271-01628-0.

- ^ Vella, George Francis. «St George, the patron saint of Gozo». Times of Malta. Times of Malta. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

«The patron saint and protector of Gozo». Times of Malta. Times of Malta. Retrieved 26 January 2017. - ^ de Bles, Arthur (2004), How to Distinguish the Saints in Art, p. 86, ISBN 1-4179-0870-X.

- ^ de Oliveira Marques, AH; André, Vítor; Wyatt, SS (1971), Daily Life in Portugal in the Late Middle Ages, University of Wisconsin Press, p. 216, ISBN 0-299-05584-1.

- ^ «Governador sanciona lei que torna São Jorge e São Sebastião padroeiros do estado».

- ^ Santos, Georgina Silva dos.Ofício e sangue: a Irmandade de São Jorge e a Inquisição na Lisboa moderna.Lisboa: Colibri; Portimão: Instituto de Cultura Ibero-Atlântica, 2005

- ^ Manfred Hollegger «Maximilian I.» (2005), p 150.

- ^ «History of the St. Georgs-Orden».

- ^ Roman Procházka «Österreichisches Ordenshandbuch» (1979), p 274.

- ^ Aldo Ziggioto, «Genova», in Vexilla Italica 1, XX (1993); Aldo Ziggioto, «Le Bandiere degli Stati Italiani», in Armi Antiche 1994, cited after Pier Paolo Lugli, 18 July 2000 Archived 29 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine on Flags of the World.

- ^ William Woo Seymour, The Cross in Tradition, History and Art, 1898, p. 363

- ^ Fuller, A Supplement tu the Historie of the Holy Warre (Book V), 1647, chapter 4.

- ^ «Vatican stamps». Vaticanstate.va. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ «Bobrov, Yury. «A catalogue of the Russian icons in the British Museum», The British Museum».

- ^ «احتفالات بمناسبة اليوبيل الماسي لبناء كنيسة مار جاورجيوس – المية ومية». Noursat. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Ælfric of Eynsham (1881). «Of Saint George» . Ælfric’s Lives of Saints. London, Pub. for the Early English text society, by N. Trübner & co.

- Brook, E.W., 1925. Acts of Saint George in series Analecta Gorgiana 8 (Gorgias Press).

- Burgoyne, Michael H. 1976. A Chronological Index to the Muslim Monuments of Jerusalem. In The Architecture of Islamic Jerusalem. Jerusalem: The British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Gabidzashvili, Enriko. 1991. Saint George: In Ancient Georgian Literature. Armazi – 89: Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Good, Jonathan, 2009. The Cult of Saint George in Medieval England (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press).

- Loomis, C. Grant, 1948. White Magic, An Introduction to the Folklore of Christian Legend (Cambridge: Medieval Society of America)

- Natsheh, Yusuf. 2000. «Architectural survey», in Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City 1517–1917. Edited by Sylvia Auld and Robert Hillenbrand (London: Altajir World of Islam Trust) pp. 893–899.

- Whatley, E. Gordon, editor, with Anne B. Thompson and Robert K. Upchurch, 2004. St. George and the Dragon in the South English Legendary (East Midland Revision, c. 1400) Originally published in Saints’ Lives in Middle English Collections (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications) (on-line introduction)

- George Menachery, Saint Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India. Vol.II Trichur – 73.

External links[edit]

- English translation of the 5th century Latin legend at Archive.org.

- St. George and the Dragon, free illustrated book based on ‘The Seven Champions’ by Richard Johnson (1596)

- Archnet

- Saint George and the Dragon links and pictures (more than 125), from Dragons in Art and on the Web

- Story of Saint George from The Golden Legends

- Saint George and the Boy Scouts, including a woodcut of a Scout on horseback slaying a dragon

- A prayer for St George’s Day

- St. George

- St. George and the Dragon: An Introduction

- Greatmartyr, Victory-bearer and Wonderworker George Orthodox icon and synaxarion for 23 April

- Dedication of the Church of the Greatmartyr George in Lydia Icon and synaxarion for 3 November

- Dedication of the Church of the Greatmartyr George at Kiev Icon and synaxarion for 26 November

- Saint George in the church in Plášťovce, (Palást) in Slovakia

- Famous Georgian Pilgrim Center in India St. George Orthodox Church Puthuppally, Kerala, India

- Hail George Radio webcast explains how Saint George came to be confused with some Afro-Brazilian deities

- Blog Article on the Feast of Saint George The feast of Saint George is 23 April – About that Dragon …

- St. George, Martyr at the Christian Iconography web site.

- Of St. George, Martyr from Caxton’s translation of the Golden Legend

|

Saint George |

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Hans von Kulmbach (c. 1510) |

|

| Martyr, Patron of England | |

| Born | Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey) |

| Died | 23 April 303 Lydda, Syria Palaestina (modern-day Lod, Israel)[1][2] |

| Venerated in |

|

| Major shrine |

|

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Clothed as a crusader in plate armour or mail, often bearing a lance tipped by a cross, riding a white horse, often slaying a dragon. In the Greek East and Latin West he is shown with St George’s Cross emblazoned on his armour, or shield or banner. |

| Patronage | Many Patronages of Saint George exist around the world |

Saint George (Greek: Γεώργιος, translit. Geṓrgios, Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldier in the Roman army. Saint George was a soldier of Cappadocian Greek origin and member of the Praetorian Guard for Roman emperor Diocletian, who was sentenced to death for refusing to recant his Christian faith. He became one of the most venerated saints and megalomartyrs in Christianity, and he has been especially venerated as a military saint since the Crusades. He is respected by Christians, Druze, as well as some Muslims as a martyr of monotheistic faith.

In hagiography, as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers and one of the most prominent military saints, he is immortalized in the legend of Saint George and the Dragon. His memorial, Saint George’s Day, is traditionally celebrated on 23 April. Historically, the countries of England, Ukraine, Ethiopia, and Georgia, as well as Catalonia and Aragon in Spain, and Moscow in Russia, have claimed George as their patron saint, as have several other regions, cities, universities, professions, and organizations. The Church-Mosque of Saint George in Lod (Lydda), Israel, contains a sarcophagus believed by many Christians to contain St. George’s remains.[6]

Legend[edit]

Very little is known about George’s life, but it is thought he was a Roman officer of Greek descent who was martyred in one of the pre-Constantinian persecutions.[7] Beyond this, early sources give conflicting information.

The saint’s veneration dates to the 5th century with some certainty, and possibly even to the 4th. The addition of the dragon legend dates to the 11th century.

The earliest text which preserves fragments of George’s narrative is in a Greek hagiography which is identified by Hippolyte Delehaye of the scholarly Bollandists to be a palimpsest of the 5th century.[8] An earlier work by Eusebius, Church history, written in the 4th century, contributed to the legend but did not name George or provide significant detail.[9] The work of the Bollandists Daniel Papebroch, Jean Bolland, and Godfrey Henschen in the 17th century was one of the first pieces of scholarly research to establish the saint’s historicity, via their publications in Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca.[10] Pope Gelasius I stated in 494 that George was among those saints «whose names are justly reverenced among men, but whose actions are known only to God.»[11]

The most complete version, based upon the fifth-century Greek text but in a later form, survives in a translation into Syriac from about 600. From text fragments preserved in the British Library a translation into English was published in 1925.[12][13][14]

In the Greek tradition, George was born to Greek Christian parents, in Cappadocia. After his father died, his mother, who was originally from Lydda, in Syria Palaestina, returned with George to her hometown.[15] He went on to become a soldier for the Roman army, but, because of his Christian faith, he was arrested and tortured, «at or near Lydda, also called Diospolis»; on the following day, he was paraded and then beheaded, and his body was buried in Lydda.[15] According to other sources, after his mother’s death he travelled to the eastern imperial capital, Nicomedia,[16] where he was persecuted by one Dadianus. In later versions of the Greek legend, this name is rationalised to Diocletian, and George’s martyrdom is placed in the Diocletian persecution of AD 303. The setting in Nicomedia is also secondary, and inconsistent with the earliest cults of the saint being located in Diospolis.[17]

George was executed by decapitation on 23 April 303. A witness of his suffering convinced Empress Alexandra of Rome to become a Christian as well, so she joined George in martyrdom. His body was buried in Lydda, where Christians soon came to honour him as a martyr.[18][19]

George in the Acta Sanctorum, as collected in late 1600s and early 1700s. The Latin title De S Georgio Megalo-Martyre; Lyddae seu Diospoli in Palaestina translates as St. George Great-Martyr; [from] Lydda or Diospolis, in Palestine.

The Latin Passio Sancti Georgii (6th century) follows the general course of the Greek legend, but Diocletian here becomes Dacian, Emperor of the Persians. His martyrdom was greatly extended to more than twenty separate tortures over the course of seven years. Over the course of his martyrdom, 40,900 pagans were converted to Christianity, including the empress Alexandra. When George finally died, the wicked Dacian was carried away in a whirlwind of fire. In later Latin versions, the persecutor is the Roman emperor Decius, or a Roman judge named Dacian serving under Diocletian.[20]

Historicity[edit]

There is little information on the early life of George. Herbert Thurston in The Catholic Encyclopedia states that based upon an ancient cultus, narratives of the early pilgrims, and the early dedications of churches to George, going back to the fourth century, «there seems, therefore, no ground for doubting the historical existence of St. George», although no faith can be placed in either the details of his history or his alleged exploits.[21]

Russian icon (mid 14th century), Novgorod

The Diocletianic Persecution of 303, associated with military saints because the persecution was aimed at Christians among the professional soldiers of the Roman army, is of undisputed historicity. According to Donald Attwater,

No historical particulars of his life have survived, … The widespread veneration for St George as a soldier saint from early times had its centre in Palestine at Diospolis, now Lydda. St George was apparently martyred there, at the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century; that is all that can be reasonably surmised about him.[22]

Edward Gibbon[23][24] argued that George, or at least the legend from which the above is distilled, is based on George of Cappadocia,[25][17] a notorious 4th-century Arian bishop who was Athanasius of Alexandria’s most bitter rival, and that it was he who in time became George of England. This identification is seen as highly improbable. Bishop George was slain by Gentile Greeks for exacting onerous taxes, especially inheritance taxes. J. B. Bury, who edited the 1906 edition of Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall, wrote «this theory of Gibbon’s has nothing to be said for it». He adds that: «the connection of St. George with a dragon-slaying legend does not relegate him to the region of the myth».[21] Saint George in all likelihood was martyred before the year 290.[26]

St. George and the dragon[edit]

Miniature from a 13th-century Passio Sancti Georgii (Verona)

The legend of Saint George and the Dragon was first recorded in the 11th century, in a Georgian source.[27]

It reached Catholic Europe in the 12th century. In the Golden Legend, by 13th-century Archbishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine, George’s death was at the hands of Dacian, and about the year 287.[citation needed]

The tradition tells that a fierce dragon was causing panic at the city of Silene, Libya, at the time George arrived there. In order to prevent the dragon from devastating people from the city, they gave two sheep each day to the dragon, but when the sheep were not enough they were forced to sacrifice humans instead of the two sheep. The human to be sacrificed was elected by the city’s own people and one time the king’s daughter was chosen to be sacrificed but no one was willing to take her place. George saved the girl by slaying the dragon with a lance. The king was so grateful that he offered him treasures as a reward for saving his daughter’s life, but George refused it and instead he gave these to the poor. The people of the city were so amazed at what they had witnessed that they became Christians and were all baptized.[28]

The Golden Legend offered a narration of George’s encounter with a dragon.

This account was very influential and it remains the most familiar version in English owing to William Caxton’s 15th-century translation.[29]

In the medieval romances, the lance with which George slew the dragon was called Ascalon, after the Levantine city of Ashkelon, today in Israel. The name Ascalon was used by Winston Churchill for his personal aircraft during World War II, according to records at Bletchley Park.[30] Iconography of the horseman with spear overcoming evil was widespread throughout the Christian period.[31]

[edit]