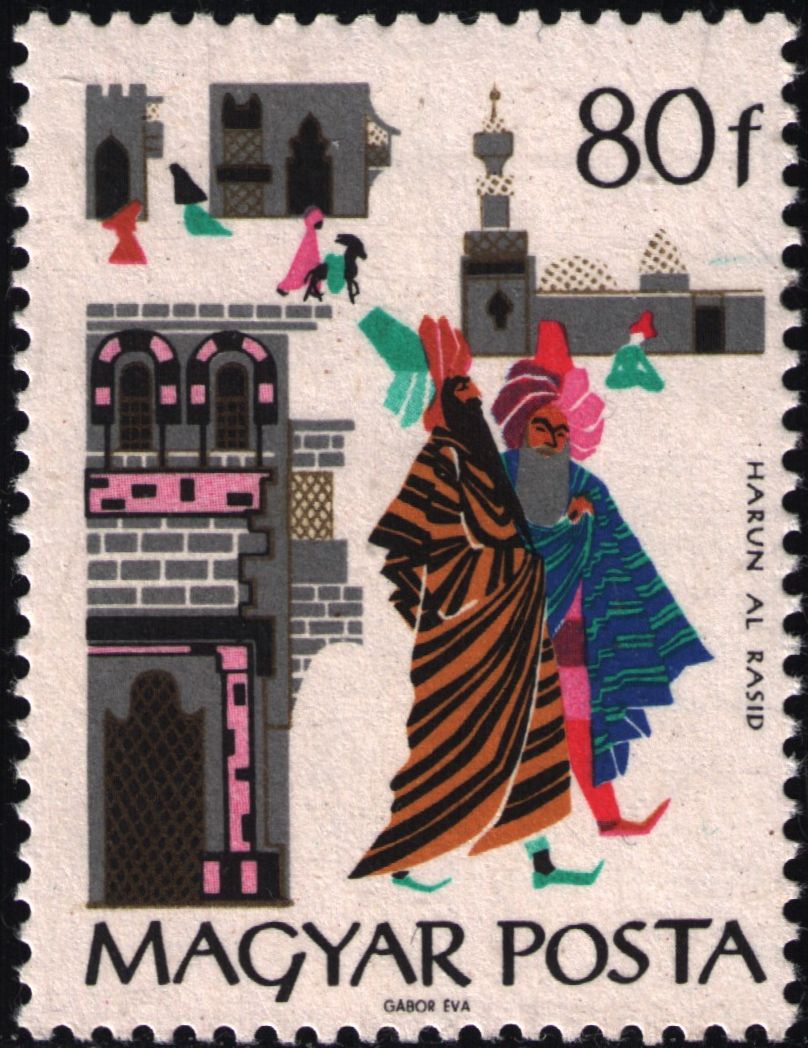

1230 лет назад, 14 сентября 786 года, правителем Абассидского халифата стал Харун ар-Рашид (Гарун аль-Рашид), или Справедливый (766-809), — пятый багдадский халиф из династии Аббасидов.

Харун превратил Багдад в блестящую и интеллектуальную столицу Востока. Он возвел для себя роскошный дворец, основал в Багдаде большой университет и библиотеку. Халиф строил школы и больницы, покровительствовал наукам и искусствам, поощрял занятия музыкой, привлекал ко двору ученых, поэтов, врачей и музыкантов, в том числе иностранцев. Сам увлекался наукой и писал стихи. При нём в Халифате достигли значительного развития сельское хозяйство, ремёсла, торговля и культура. Считается, что правление халифа Харуна ар-Рашида ознаменовалось экономическим и культурным расцветом и сохранилось в памяти мусульман как «золотой век» Багдадского халифата.

В результате фигура Харуна ар-Рашида была идеализирована в арабском фольклоре. Он стал одним из героев сказок «Тысячи и одной ночи», где предстает добрым, мудрым и справедливым правителем, защищающим простых людей от нечестных чиновников и судей. Притворяясь купцом, он бродил по ночным улицам Багдада, чтобы можно было общаться с простыми людьми и узнать об истинном положении дел в стране и нуждах своих подданных.

Правда, уже в правление Харуна наметились признаки кризиса халифата: произошли крупные антиправительственные восстания в Северной Африке, Дейлеме, Сирии, Средней Азии и других областях. Халиф стремился укрепить единство государства на базе официального ислама, делая ставку на духовенство и суннитское большинство населения, а против оппозиционных движений в исламе осуществлял репрессии и проводил политику ограничения прав немусульманского населения в халифате.

Из истории Арабского халифата

Арабская государственность зародилась на Аравийском полуострове. Наиболее развитой областью был Йемен. Более ранее по сравнению с остальной Аравией развитие Йемена было вызвано посреднической ролью, которую он играл в торговле Египта, Палестины и Сирии, а затем и всего Средиземноморья, с Эфиопией (Абиссинией) и Индией. Кроме того, в Аравии было ещё два крупных центра. На западе Аравии была расположена Мекка — важный перевалочный пункт на караванном пути из Йемена в Сирию, процветавший за счет транзитной торговли. Другим крупным городом Аравии была Медина (Ясриб), которая была центром земледельческого оазиса, но здесь были и торговцы и ремесленники. Так, если к началу VII в. большая часть арабов, проживавших в центральных и северных областях, оставалась кочевниками (бедуины-степняки); то в этой части Аравии шел интенсивный процесс разложения родоплеменного строя и начали складываться раннефеодальные отношения.

Кроме того, старая религиозная идеология (многобожие) переживала кризис. В Аравию проникло христианство (из Сирии и Эфиопии) и иудаизм. В VI в. в Аравии возникло движение ханифов, признававших только единого бога и заимствовавших у христианства и иудейства некоторые установки и обряды. Это движение было направлено против племенных и городских культов, за создание единой религии, признающей единого бога (аллаха, арабское ал — илах). Новое учение возникло в самых развитых центрах полуострова, где феодальные отношения получили большее развитие, — в Йемене и городе Ясрибе. Движением была захвачена и Мекка. Одним из представителей его был купец Мухаммед, который и стал основателем новой религии — ислама (от слова «покорность»).

В Мекке это учение встретило оппозицию со стороны знати, в результате чего Мухаммед и его последователи вынуждены были в 622 г. бежать в Ясриб. От этого года ведется мусульманское летоисчисление. Ясриб получил название Медины, т. е. города Пророка (так стали называть Мухаммеда). Здесь была основана мусульманская община как религиозно-военная организация, которая вскоре превратилась в крупную военно-политическую силу и стала центром объединения арабских племен в единое государство. Ислам с его проповедью братства всех мусульман, независимо от племенного деления, был принят прежде всего простыми людьми, которые страдали от притеснений племенной знати и давно потерял веру в могущество племенных божков, не защитивших их от кровавой родоплеменной резни, бедствий и нищеты. Сначала племенная знать и богатые торговцы выступали против ислама, но затем признала его пользу. Ислам признавал рабство, защищал частную собственность. Кроме того, создание сильного государства было и в интересах знати, можно было начать внешнюю экспансию.

В 630 г. между противоборствующими силами было достигнуто соглашение, по которому Мухаммед был признан пророком и главой Аравии, а ислам новой религией. К концу 630 г. значительная часть Аравийского полуострова признала власть Мухаммеда, что означало образование Арабского государства (халифата). Так были созданы условия для объединения оседлых и кочевых арабских племен, и начала внешней экспансии против соседей, которые погрязли во внутренних проблемах и не ожидали появления нового сильного и единого врага.

После смерти Мухаммеда в 632 г. устанавливается система правления халифов (заместителей пророка). Первые халифы были сподвижниками пророка и при них началась широкая внешняя экспансия. К 640 г. арабы завоевали почти всю Палестину и Сирию. При этом многие города так устали от репрессий и налогового гнета ромеев (византийцев), что практически не оказывали сопротивления. Арабы в первый период были довольно терпимы к другим религиям и иноземцам. Так, такие крупнейшие центры как Антиохия, Дамаск и другие сдались завоевателям лишь при условии сохранения личной свободы, свободы для христиан и иудеев их религии. Вскоре арабы завоевали Египет и Иран. В результате этих и дальнейших завоеваний было создано огромное государство. Дальнейшая феодализация, сопровождавшаяся ростом власти крупных феодалов в их владениях, и ослабление центральной власти, привели к распаду халифата. Наместники халифов — эмиры постепенно добились полной независимости от центральной власти и превратились в суверенных правителей.

Историю Арабского государства делят на три периода по названию правящих династий или месту нахождения столицы: 1) Мекканский период (622 — 661 гг.) — это время правления Мухаммеда и близких его сподвижников; 2) Дамасский (661-750 гг.) — правление Омейядов; 3) Багдадский (750 — 1055 гг.) — правление династии Аббасидов. Аббас — дядя пророка Мохаммеда. Его сын Абдалла стал основателем династии Аббасидов, которая в лице внука Абдаллы, Абул-Аббаса, в 750 г. заняла трон багдадских халифов.

Арабский халифат в правление Харуна

Правление Харуна ар-Рашида

Харун ар-Рашид родился в 763 г. и был третьим сыном халифа аль-Махди (775-785). Его отец был более склонен к жизненным удовольствиям, чем к государственным делам. Халиф являлся большим любителем поэзии и музыки. Именно в период его правления стал складываться тот образ двора арабского халифа, славный своей роскошью, утончённостью и высокой культурой, которые позднее прославился в мире по сказкам «Тысячи и одной ночи».

В 785 году трон занял Муса аль-Хади — сын халифа аль-Махди, старший брат халифа Харуна ар-Рашида. Однако он правил всего год с небольшим. Судя по всему, его отравила собственная мать — Хайзуран. Она поддерживала младшего сына Харуна ар-Рашида, так как старший сын пытался вести самостоятельную политику. С восшествием на престол Харуна ар-Рашида Хайзуран стала почти полновластной правительницей. Главной её опорой был персидский род Бармакидов.

Халид из династии Бармакидов был советником халифа аль-Махди, а его сын Яхья ибн Халид был главой дивана (правительства) принца Харуна, который в то время был наместником запада (всех провинций к западу от Евфрата) с Сирией, Арменией и Азербайджаном. После вступления на престол Харун ар-Рашида Яхья (Йахья) Бармакид, которого халиф называл «отцом», был назначен визирем с неограниченными полномочиями и в течение 17 лет (786—803) правил державой с помощью своих сыновей Фадла и Джафара. Однако после смерти Хайзуран род Бармакидов стал постепенно утрачивать былое могущество. Освободившись от опеки матери, честолюбивый и хитрый халиф стремился сосредоточить в своих руках всю полноту власти. При этом он старался опираться на таких вольноотпущенников (мавали), которые не проявляли бы самостоятельности, полностью зависели бы от его воли и, естественно, были ему полностью преданы. В 803 г. Харун сверг могущественный род. Джафар был убит по приказу халифа. А Яхья с остальными тремя его сыновьями был арестован, их имения были конфискованы.

Таким образом, в первые годы своего правления Харун во всем полагался на Яхью, которого назначил своим визирем, а также мать. Халиф преимущественно занимался искусствами, особенно поэзией и музыкой. Двор Харуна ар-Рашида был центром традиционных арабских искусств, а о роскоши придворной жизни ходили легенды. Согласно одной из них, только свадьба Харуна стоила казне 50 млн. дирхемов.

Общая же ситуация в халифате постепенно ухудшалась. Арабская империя начала путь к своему закату. Годы правления Харуна ознаменовались многочисленными волнениями и мятежами, вспыхивавшими в разных областях империи.

Процесс развала начался в наиболее удаленных, западных областях империи еще с установления власти Омейядов в Испании (Андалусии) в 756 г. Дважды, в 788 и в 794 гг., вспыхивали восстания в Египте. Народ был недоволен следствие высоких налогов и многочисленных повинностей, которыми была обременена эта богатейшая провинция Арабского халифата. Она была обязана снабжать всем необходимым аббасидскую армию, направляемую в Ифрикию (современный Тунис). Военачальник и наместник Аббасидов Харсама ибн Айан жестоко подавил восстания и принудил египтян к повиновению. Более сложной оказалась ситуация с сепаратистскими устремлениями берберского населения Северной Африки. Эти области были удалены от центра империи, и из-за условий местности аббасидской армии трудно было справиться с мятежниками. В 789 г. в Марокко установилась власть местной династии Идрисидов, а через год — в Ифрикии и Алжире — Аглабидов. Харсама сумел подавить мятеж Абдаллаха ибн Джаруда в Кайраване в 794-795 гг. Но в 797 году в Северной Африке вновь вспыхнуло восстание. Харун вынужден был примириться с частичной утратой власти в этом регионе и возложить правление Ифрикией на местного эмира Ибрахима ибн аль-Аглаба в обмен на ежегодную дань в размере 40 тыс. динаров.

В отдаленном от центров империи Йемене также было неспокойно. Жестокая политика наместника Хаммада аль-Барбари привела к восстанию в 795 г. под руководством Хайсама аль-Хамдани. Восстание продолжалось девять лет и закончилось высылкой его лидеров в Багдад и их казнью. Сирия, населенная непокорными, враждующими между собой арабскими племенами, которые были настроены в пользу Омейядов, пребывала в состоянии почти непрерывных мятежей. В 796 г. положение в Сирии оказалось настолько серьезным, что халифу пришлось направить в нее войско во главе со своим любимцем Джафаром из рода Бармакидов. Правительственной армии удалось подавить мятеж. Возможно, что волнения в Сирии были одной из причин переезда Харуна из Багдада в Ракку на Евфрате, где он проводил большую часть времени и откуда направлялся в походы против Византии и в паломничество в Мекку.

Кроме того, Харун столицу империи не любил, жителей города опасался и предпочитал появляться в Багдаде не слишком часто. Возможно, это было связано с тем, что расточительный, когда дело шло о придворных развлечениях, халиф был весьма прижимист и беспощаден при сборе налогов, и поэтому у жителей Багдада и других городов, не пользовался симпатией. В 800 г. халиф специально приехал из своей резиденции в Багдад, чтобы взыскать недоимки при уплате податей, причем недоимщиков беспощадно били и сажали в тюрьму.

На востоке империи ситуация также была нестабильной. Причём постоянные волнения на востоке Арабского халифата были связаны не столько с экономическими предпосылками, сколько с особенностями культурно-религиозных традиций местного населения (в основном — персов-иранцев). Жители восточных провинций были в большей мере привязаны к собственным старинным верованиям и традициям, чем к исламу, а иногда, как это было в провинциях Дайлам и Табаристан, вовсе чужды ему. Кроме того, обращение жителей этих провинций в ислам к VIII в. еще не завершилось полностью, и Харун лично занимался в Табаристане исламизацией. В результате недовольство жителей восточных провинций действиями центрального правительства приводило к волнениям.

Иногда местные жители выступали за династию Алидов. Алиды — потомки Али ибн Аби Талиба — двоюродного брата и зятя пророка Мухаммада, мужа дочери пророка Фатимы. Они считали себя единственными законными преемниками пророка и претендовали на политическую власть в империи. Согласно религиозно-политической концепции шиитов (партия сторонников Али) верховная власть (имамат), подобно пророчеству, рассматривается как «божественная благодать». В силу «божественного предписания» право на имамат принадлежит только Али и его потомкам и должно переходить по наследству. С точки зрения шиитов, Аббасиды были узурпаторами, и Алиды вели с ними постоянную борьбу за власть. Так, в 792 году один из алидов, Яхья ибн Абдаллах, поднял восстание в Дайламе и получил поддержку со стороны местных феодалов. Харун отправил в Дайлам аль-Фадла, который при помощи дипломатии и обещаний амнистии участникам восстания добился сдачи Яхьи. Харун коварно нарушил слово и нашел предлог, чтобы отменить амнистию и бросить лидера восставших в тюрьму.

Иногда это были восстания хариджитов — религиозно-политической группировки, обособившаяся от основной части мусульман. Хариджиты признавали законными только двух первых халифов и выступали за равенство всех мусульман (арабов и неарабов) внутри общины. Считали, что халиф должен быть выборным и обладать только исполнительной властью, а судебная и законодательная власть должна быть у совета (шура). Хариджиты имели сильную социальную базу в Ираке, Иране, Аравии, да и в Северной Африке. Кроме того, существовали различные персидские секты радикальных направлений.

Наиболее опасными для единства империи во времена халифа Харуна ар-Рашида были выступления хариджитов в провинциях Северной Африки, Северной Месопотамии и в Сиджистане. Руководитель восстания в Месопотамии аль-Валид аш-Шари в 794 году захватил власть в Нисибине, привлек на свою сторону племена аль-Джазиры. Харуну пришлось отправить против повстанцев войско во главе с Иазидом аш-Шайбани, который сумел подавить восстание. Другое восстание вспыхнуло в Сиджистане. Его вождь Хамза аш-Шари в 795 году захватил Харат и распространил свою власть на иранские провинции Кирман и Фарс. Харуну так и не удалось справиться с хариджитами до самого конца его царствования. В последние годы VIII и в начале IX в. Хорасан и отдельные области Средней Азии также были охвачены волнениями. 807-808 гг. Хорасан фактически перестал подчиняться Багдаду.

При этом Харун проводил жесткую религиозную политику. Он постоянно подчеркивал религиозный характер своей власти и жестоко наказывал за всякое проявление ереси. По отношению к иноверцам политика Харуна также отличалась крайней нетерпимостью. В 806 г. он распорядился разрушить все церкви вдоль византийской границы. В 807 г. Харун приказал возобновить старинные ограничения для иноверцев в отношении одежды и поведения. Иноверцы должны были подпоясываться веревками, голову покрывать стегаными шапками, туфли носить не такие, какие носили правоверные, ездить не на лошадях, а на ослах и т. д.

Несмотря на постоянные внутренние мятежи, волнения, восстания неповиновения эмиров отдельных областей, Арабский халифат продолжал войну с Византией. Пограничные рейды арабских и византийских отрядов происходили почти ежегодно, и во многих военных экспедициях Харун лично принимал участие. При нем была выделена в административном отношении особая пограничная область с укрепленными городами-крепостями, сыгравшими в войнах последующих столетий важную роль. В 797 году, воспользовавшись внутренними проблемами Византийской империи и её войной с болгарами, Харун проник с армией далеко в глубь Византии. Императрица Ирина, регентша малолетнего сына (позднее самостоятельная правительница), вынуждена была заключить с арабами мирный договор. Однако сменивший её в 802 году византийский император Никифор возобновил военные действия. Харун отправил против Византии сына Касима с войском, а позднее и лично возглавил поход. В 803-806 гг. арабская армия захватила множество городов и селении на территории Византии, в том числе Геракл и Тиану. Атакуемый болгарами с Балкан и терпящий поражение в войне с арабами, Никифор вынужден был заключить унизительный мир и обязался выплачивать Багдаду дань.

Кроме того, Харун обратил внимание на Средиземное море. В 805 г. арабы предприняли успешный морской поход против Кипра. А в 807 г. по приказу Харуна арабский полководец Хумайд совершил набег на остров Родос.

Фигура Харуна ар-Рашида была идеализирована в арабском фольклоре. Мнения современников и исследователей о его роли сильно отличаются. Одни считают, что правление халифа Харуна ар-Рашида привело к экономическому и культурному расцвету арабской империи и было «золотым веком» Багдадского халифата. Харуна называют благочестивым человеком. Другие, наоборот, критикуют Харуна, называют его беспутным и некомпетентным правителем. Считают, что всё полезное в империи было сделано при Бармакидах. Историк аль-Масуди писал, что «процветание империи уменьшилось после падения Бармакидов, и все убедились, насколько несовершенными были действия и решения Харуна ар-Рашида и дурным его правление».

Последний период царствования Харуна действительно не свидетельствует о его дальновидности и некоторые из его решений в итоге способствовали усилению внутреннего противостояния и последующему распаду империи. Так, в конце своей жизни Харун совершил большую ошибку, когда разделил империю между наследниками, сыновьями от разных жен — Мамуном и Амином. Это привело после смерти Харуна к гражданской войне, во время которой сильно пострадали центральные провинции Халифата и особенно Багдад. Халифат перестал быть единым государством, в разных областях стали возникать династии местных крупных феодалов, только номинально признававших власть «повелителя правоверных».

This article is about an Abbasid caliph. For other uses, see Haroon Rashid.

| Harun al-Rashid هَارُون الرَشِيد |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Gold dinar of Harun al-Rashid[b] |

||

| 5th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | ||

| Reign | 14 September 786 – 24 March 809 | |

| Predecessor | Al-Hadi | |

| Successor | Al-Amin | |

| Born | 17 March 763 or February 766 Ray, Jibal, Abbasid Caliphate (in present-day Tehran Province, Iran) |

|

| Died | 24 March 809 (aged 43) Tus, Khorasan, Abbasid Caliphate (in present-day Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran) |

|

| Burial |

Tomb of Harun al-Rashid in Imam Reza Mosque, Mashhad, Iran |

|

| Spouse |

|

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | |

| Father | Al-Mahdi | |

| Mother | Al-Khayzuran | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Abu Ja’far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi (Arabic: أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (Arabic: هَارُون ابْنِ ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, romanized: Hārūn ibn al-Mahdī; c. 763 or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid (Arabic: هَارُون الرَشِيد, romanized: Hārūn al-Rashīd)[h] was the fifth Abbasid caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, reigning from September 786 until his death. His reign is traditionally regarded to be the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age. His epithet «al-Rashid» translates to «the Orthodox», «the Just», «the Upright», or «the Rightly-Guided».

Harun established the legendary library Bayt al-Hikma («House of Wisdom») in Baghdad in present-day Iraq, and during his rule Baghdad began to flourish as a world center of knowledge, culture and trade.[1] During his rule, the family of Barmakids, which played a deciding role in establishing the Abbasid Caliphate, declined gradually. In 796, he moved his court and government to Raqqa in present-day Syria.

A Frankish mission came to offer Harun friendship in 799. Harun sent various presents with the emissaries on their return to Charlemagne’s court, including a clock that Charlemagne and his retinue deemed to be a conjuration because of the sounds it emanated and the tricks it displayed every time an hour ticked.[2][3][4] Portions of the fictional One Thousand and One Nights are set in Harun’s court and some of its stories involve Harun himself.[5] Harun’s life and court have been the subject of many other tales, both factual and fictitious.

Early life[edit]

Hārūn was born in Rey, then part of Jibal in the Abbasid Caliphate, in present-day Tehran Province, Iran. He was the son of al-Mahdi, the third Abbasid caliph (r. 775–786), and his wife al-Khayzuran, (a former slave girl from Yemen) who was a woman of strong and independent personality who greatly and determinedly influenced affairs of state in the reigns of her husband and sons. Growing up Harun studied history, geography, rhetoric, music, poetry, and economics. However, most of his time was dedicated to mastering hadith and the Quran. In addition, he underwent advanced physical education as a future mujahid, and as a result, he practiced swordplay, archery, and learned the art of war.[6] His birth date is debated, with various sources giving dates from 763 to 766.[7]

Before becoming a caliph, in 780 and again in 782, Hārūn had already nominally led campaigns against the Caliphate’s traditional enemy, the Eastern Roman Empire, ruled by Empress Irene. The latter expedition was a huge undertaking, and even reached the Asian suburbs of Constantinople. According to the Muslim chronicler Al-Tabari, the Byzantines had lost tens of thousands of soldiers during Harun’s campaign, and Harun employed 20,000 mules to carry the booty back. Upon his return to the Abbasid realm, the cost of a sword fell to one dirham and the price of a horse to a single gold Byzantine dinar.[8]

Harun’s raids against the Byzantines elevated his political image and once he returned, he was given the alias «al-Rashid», meaning «the Rightly-Guided One». He was promoted to crown prince and given the responsibility of governing the empire’s western territories, from Syria to Azerbaijan.[9]

Caliphate[edit]

Hārūn became caliph in 786 when he was in his early twenties. At the time, he was tall, good looking, and slim but strongly built, with wavy hair and olive skin.[10] On the day of accession, his son al-Ma’mun was born, and al-Amin some little time later: the latter was the son of Zubaida, a granddaughter of al-Mansur (founder of the city of Baghdad); so he took precedence over the former, whose mother was a Persian. Upon his accession, Harun led Friday prayers in Baghdad’s Great Mosque and then sat publicly as officials and the layman alike lined up to swear allegiance and declare their happiness at his ascent to Amir al-Mu’minin.[11] He began his reign by appointing very able ministers, who carried on the work of the government so well that they greatly improved the condition of the people.[12]

Under Hārūn al-Rashīd’s rule, Baghdad flourished into the most splendid city of its period. Tribute paid by many rulers to the caliph funded architecture, the arts and court luxuries.

In 796, Hārūn moved the entire court to Raqqa on the middle Euphrates, where he spent 12 years, most of his reign. He appointed the Hanafi jurist Muhammad al-Shaybani as qadi (judge), but dismissed him in 803. He visited Baghdad only once. Several reasons may have influenced the decision to move to Raqqa: its closeness to the Byzantine border, its excellent communication lines via the Euphrates to Baghdad and via the Balikh river to the north and via Palmyra to Damascus, rich agricultural land, and the strategic advantage over any rebellion which might arise in Syria and the middle Euphrates area. Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, in his anthology of poems, depicts the splendid life in his court. In Raqqa the Barmakids managed the fate of the empire, and both heirs, al-Amin and al-Ma’mun, grew up there. At some point the royal court relocated again to Al-Rayy, the capital city of Khorasan, where the famous philologist and leader of the Kufan school, Al-Kisa’i, accompanied the caliph with his entourage. When al-Kisa’i became ill while in Al-Rayy, it is said that Harun visited him daily. It seems al-Shaybani and al-Kisa’i both died there on the same day in 804. Harun is quoted as saying: «Today Law and Language have died».

For the administration of the whole empire, he fell back on his mentor and longtime associate Yahya bin Khalid bin Barmak. Rashid appointed him as his vizier with full executive powers, and, for seventeen years, Yahya and his sons served Rashid faithfully in whatever assignment he entrusted to them.[13]

Harun made pilgrimages to Mecca by camel (2,820 km or 1,750 mi from Baghdad) several times, e.g., 793, 795, 797, 802 and last in 803. Tabari concludes his account of Harun’s reign with these words: «It has been said that when Harun ar-Rashid died, there were nine hundred million odd (dirhams) in the state treasury.»[14]

According to Shia belief, Harun imprisoned and poisoned Musa ibn Ja’far, the 7th Imam, in Baghdad.

Under al-Rashid, each city had its own law enforcement, which besides keeping order was supposed to examine the public markets in order to ensure, for instance, that proper scales and measures were used; enforce the payment of debts; and clamp down on illegal activities such as gambling, usury, and sales of alcohol.[15]

Harun was a great patron of art and learning, and is best known for the unsurpassed splendor of his court and lifestyle. Some of the stories, perhaps the earliest, of «The Thousand and One Nights» were inspired by the glittering Baghdad court. The character King Shahryar (whose wife, Scheherazade, tells the tales) may have been based on Harun himself.[16]

Advisors[edit]

A silver dirham minted in Madinat al-Salam (Bagdad) in 170 AH (786 CE). At the reverse, the inner marginal inscription says: «By order of the slave of God, Harun, Commander of the Faithful»

Hārūn was influenced by the full will of his powerful and influential mother in the governance of the empire until her death in 789. His vizier (chief minister) Yahya the Barmakid, Yahya’s sons (especially Ja’far ibn Yahya), and other Barmakids generally controlled the administration. The position of Persians in the Abbasid caliphal court reached its peak during al-Rashid’s reign.[17]

The Barmakids were an Iranian family (from Balkh) that dated back to the Barmak, a hereditary Buddhist priest of Nava Vihara, who converted after the Islamic conquest of Balkh and became very powerful under al-Mahdi. Yahya had helped Hārūn to obtain the caliphate, and he and his sons were in high favor until 798, when the caliph threw them in prison and confiscated their land. Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari dates this event to 803 and lists various reasons for it: Yahya’s entering the Caliph’s presence without permission; Yahya’s opposition to Muhammad ibn al Layth, who later gained Harun’s favour; and Ja’far’s release of Yahya ibn Abdallah ibn Hasan, whom Harun had imprisoned.

The fall of the Barmakids is far more likely due to their behaving in a manner that Harun found disrespectful (such as entering his court unannounced) and making decisions in matters of state without first consulting him.[citation needed] Al-Fadl ibn al-Rabi succeeded Yahya the Barmakid as Harun’s chief minister.

Diplomacy[edit]

Harun al-Rashid at left receiving a delegation sent by Charlemagne to his court in Baghdad.

1864 painting by Julius Köckert.

Both Einhard and Notker the Stammerer refer to envoys traveling between the courts of Harun and Charlemagne, king of the Franks, and entering friendly discussions about Christian access to holy sites and gift exchanges. Notker mentions Charlemagne sent Harun Spanish horses, colorful Frisian cloaks and impressive hunting dogs. In 802 Harun sent Charlemagne a present consisting of silks, brass candelabra, perfume, balsam, ivory chessmen, a colossal tent with many-colored curtains, an elephant named Abul-Abbas, and a water clock that marked the hours by dropping bronze balls into a bowl, as mechanical knights – one for each hour – emerged from little doors which shut behind them. The presents were unprecedented in Western Europe and may have influenced Carolingian art.[18] This exchange of embassies was due to the fact that Harun was interested, like Charlemagne, in subduing the Umayyad emirs of Córdoba. Also, the common enmity against the Byzantines was what brought Harun closer to the contemporary Charlemagne.

When the Byzantine empress Irene was deposed in 802, Nikephoros I became emperor and refused to pay tribute to Harun, saying that Irene should have been receiving the tribute the whole time. News of this angered Harun, who wrote a message on the back of the Byzantine emperor’s letter and said, «In the name of God the most merciful, From Amir al-Mu’minin Harun ar-Rashid, commander of the faithful, to Nikephoros, dog of the Romans. Thou shalt not hear, thou shalt behold my reply». After campaigns in Asia Minor, Nikephoros was forced to conclude a treaty, with humiliating terms.[19][20] According to Dr Ahmad Mukhtar al-Abadi, it is due to the particularly fierce second retribution campaign against Nikephoros, that the Byzantine practically ceased any attempt to incite any conflict against the Abbasid again until the rule of Al-Ma’mun.[21][22]

An alliance was established with the Chinese Tang dynasty by Ar-Rashid after he sent embassies to China.[23][24] He was called «A-lun» in the Chinese Tang Annals.[25] The alliance was aimed against the Tibetans.[26][27][28][29][30]

When diplomats and messengers visited Harun in his palace, he was screened behind a curtain. No visitor or petitioner could speak first, interrupt, or oppose the caliph. They were expected to give their undivided attention to the caliph and calculate their responses with great care.[31]

Rebellions[edit]

Because of the Thousand and One Nights tales, Harun al-Rashid turned into a legendary figure obscuring his true historic personality. In fact, his reign initiated the political disintegration of the Abbasid caliphate. Syria was inhabited by tribes with Umayyad sympathies and remained the bitter enemy of the Abbasids, while Egypt witnessed uprisings against Abbasids due to maladministration and arbitrary taxation. The Umayyads had been established in Spain in 755, the Idrisids in Morocco in 788, and the Aghlabids in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia) in 800. Besides, unrest flared up in Yemen, and the Kharijites rose in rebellion in Daylam, Kerman, Fars and Sistan. Revolts also broke out in Khorasan, and al-Rashid waged many campaigns against the Byzantines.

Al-Rashid appointed Ali bin Isa bin Mahan as the governor of Khorasan, who tried to bring to heel the princes and chieftains of the region, and to reimpose the full authority of the central government on them. This new policy met with fierce resistance and provoked numerous uprisings in the region.

Family[edit]

Harun’s first wife was Zubaidah. She was the daughter of his paternal uncle, Ja’far and maternal aunt Salsal, sister of Al-Khayzuran.[32] They married in 781–82, at the residence of Muhammad bin Sulayman in Baghdad. She had one son, Caliph Al-Amin.[33] She died in 831.[34] Another of his wives was Azizah, daughter of Ghitrif, brother of Al-Khayzuran.[35] She had been formerly married to Sulayman bin Abi Ja’far, who had divorced her.[34] Another was Amat-al-Aziz Ghadir, who had been formerly a concubine of his brother al-Hadi.[35] She had one son Ali.[33] She died in 789.[35] Another wife was Umm Muhammad, the daughter of Salih al-Miskin and Umm Abdullah, the daughter of Isa bin Ali. They married in November-December 803 in Al-Raqqah. She had been formerly been married to Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi, who had repudiated her.[34] Another wife married around the same year was Abbassah, daughter of Sulayman ibn Abi Ja’far.[34] Another wife was Jurashiyyah al-Uthmanniyah. She was the daughter of Abdullah bin Muhammad, and had descended from Uthman, the third Caliph of the Rashidun.[34]

Harun’s earliest known concubine was Hailanah. She had been a slave girl of Yahya ibn Khalid, the Barmakid. It was she who begged him, while he was yet a prince, to take her away from the elderly Yahya. Harun then approached Yahya, who presented him with the girl. She died three years later[36] in 789–90,[37] and Harun mourned her deeply.[36] Another concubine was Dananir. She was a Barmakid, and had been formerly a slave girl of Yahya ibn Khalid. She had been educated at Medina and had studied instrumental and vocal music.[38] Another concubine was Marajil. She was a Persian, and came from distant Badhaghis in Persia. She was one of the ten maids presented to Harun. She gave birth to Abdullah (future caliph Al-Ma’mun) on the night of Harun’s accession to the throne, in September 786, in whose birth she died. Her son was then adopted by Zubaidah.[33] Another concubine was Qasif, mother of Al-Qasim. He was Harun’s second son, born to a concubine mother. Harun’s eldest daughter Sukaynah was also born to her.[39]

Another concubine was Maridah. Her father was Shabib.[40] She was a Sogdian, and was born in Kufah. She was one of the ten maids presented to Harun by Zubaidah. She had five children. These were Abu Ishaq (future Caliph Al-Mu’tasim), Abu Isma’il, Umm Habib, and two others whose names are unknown. She was Harun’s favourite concubine.[41] Some other favourite concubines were, Dhat al-Khal, Sihr, and Diya. Diya passed away, much to Harun’s sorrow.[42] Dhat al-Khal also known as Khubth[43] was a songstress, belonging to a slave-dealer who was himself a freedman of Abbasah, the sister of Al-Rashid. She caught the fancy of Ibrahim al-Mausili, whose songs in praise of her soon reached Harun’s attention, who bought her for the enormous sum of 70,000 dinars.[44] She was the mother of Harun’s son, Abu al-Abbas Muhammad.[43][44] Sihr was mother of Harun’s daughters, Khadijah[44] and Karib.[45] Another concubine was Inan. Her father was Abdullah.[46] She was born and brought up in the Yamamah in central Arabia. She was a songstress and a poet, and had been a slave girl of Abu Khalid al-Natifi.[47] She bore Harun two sons, both of whom died young. She accompanied him to Khurasan where he, and, soon after, she died.[48] Another was Ghadid, also known as Musaffa, and she was mother of Harun’s daughters, Hamdunah[49] and Fatimah.[45] She was his favourite concubine.[49] Hamdunah and Fatimah married Al-Hadi’s sons, Isma’il and Ja’far respectively.[50]

Another of Harun’s concubines was the captive daughter of a Greek churchman of Heraclea acquired with the fall of that city in 806. Zubaidah once more presented him with one of her personal maids who had caught his fancy. Harun’s half-brother, while governor of Egypt from 795 to 797, also sent the him an Egyptian maid who immediately won his favour.[51] Some other concubines were namely: Ri’m, mother of Salih; Irbah, mother of Abu Isa Muhammad; Sahdhrah, mother of Abu Yaqub Muhammad; Rawah, mother of Abu Sulayman Muhammad; Dawaj, mother of Abu Ali Muhammad; Kitman, mother of Abu Ahmad Muhammad; Hulab, mother of Arwa; Irabah, mother of Umm al-Hassan; Sukkar, mother of Umm Abiha; Rahiq, mother of Umm Salamah; Khzq, mother of Umm al-Qasim; Haly, mother of Umm Ja’far Ramlah; Aniq, mother of Umm Ali; Samandal, mother of Umm al-Ghaliyah; Zinah, mother of Raytah.[52]

Anecdotes[edit]

Many anecdotes attached themselves to the person of Harun al-Rashid in the centuries following his rule. Saadi of Shiraz inserted a number of them into his Gulistan.

Al-Masudi relates a number of interesting anecdotes in The Meadows of Gold that illuminate the caliph’s character. For example, he recounts Harun’s delight when his horse came in first, closely followed by al-Ma’mun’s, at a race that Harun held at Raqqa. Al-Masudi tells the story of Harun setting his poets a challenging task. When others failed to please him, Miskin of Medina succeeded superbly well. The poet then launched into a moving account of how much it had cost him to learn that song. Harun laughed and said that he did not know which was more entertaining, the song or the story. He rewarded the poet.[53]

There is also the tale of Harun asking Ishaq ibn Ibrahim to keep singing. The musician did so until the caliph fell asleep. Then, strangely, a handsome young man appeared, snatched the musician’s lute, sang a very moving piece (al-Masudi quotes it) and left. On awakening and being informed of that, Harun said Ishaq ibn Ibrahim had received a supernatural visitation.

Shortly before he died, Harun is said to have been reading some lines by Abu al-Atahiya about the transitory nature of the power and pleasures of this world, an anecdote related to other caliphs as well.

Every morning, Harun gave one thousand dirhams to charity and made one hundred prostrations a day.[14] Harun famously used to look up at rain clouds in the sky and said: «rain where you like, but I will get the land tax!»[54]

Harun was terrified for his soul in the afterlife. It was reported that he quickly cried when he thought of God and read poems about the briefness of life.[55]

Soon after he became caliph, Harun asked his servant to bring him Ibn al-Sammak, a renowned scholar, to obtain wisdom from him. Harun asked al-Sammak what he would like to tell him. Al-Sammak replied, «I would like you always to remember that one day you will stand alone before your God. You will then be consigned either to Heaven or to Hell.» That was too harsh for Harun’s liking, and he was obviously disturbed. His servant cried out in protest that the Prince of the Faithful will definitely go to heaven after he has ruled justly on earth. However, al-Sammak ignored the interruption and looked straight into the eyes of Harun and said that «you will not have this man to defend you on that day.»[55]

An official, Maan ibn Zaidah, had fallen out of favor with Harun. When Harun saw him in court, he said that «you have grown old.» The elderly man responded, «Yes, O Commander of the Faithful in your service.» Harun replied, «But you have still some energy left.» The old man replied that “what I have, is yours to dispose of as you wish… and I am bold in opposing your foes.» Harun was satisfied with the encounter and made the man governor of Basra for his final years.[56]

On hajj, he distributed large amounts of money to the people of Mecca and Medina and to poor pilgrims en route. He always took a number of ascetics with him, and whenever he was unable to go on pilgrimage, he sent dignitaries and three hundred clerics at his own expense.[57]

One day, Harun was visiting a dignitary when he was struck by his beautiful slave. Harun asked the man to give her to him. The man obliged but was visibly disturbed by the loss. Afterward, Harun felt sorry for what he had done and gave her back.[58]

Harun was an excellent horseman, enjoyed hunting (with Salukis, falcons, and hawks) and was fond of military exercises such as charging dummies with his sword. Harun was also the first Abbasid caliph to have played and promoted chess.[59]

Harun desired a slave girl that was owned by an official named Isa who refused to give her to Harun, despite threats. Isa explained that he swore (in the middle of a sex act) that if he ever gave away or sold her, he would divorce his wife, free his slaves, and give all of his possessions to the impoverished. Yusuf, a judge and advisor to Harun, was called to arbitrate the case and to figure out a legal way for Isa to maintain his belongings even if Harun walked away with the girl. Yusuf decided that if Isa gave half of the girl to Harun and sold him the other half, it could not be said that Isa had either given her away or sold her, keeping his promise.[60]

Harun had an anxious soul and supposedly was prone to walk the streets of Baghdad at night. At times Ja’far ibn Yahya accompanied him. The night-time tours likely arose from a genuine and sympathetic concern in the well-being of his people, for it is said that he was assiduous to relieve any of their trials and tend to their needs.[56]

Death[edit]

Abbasid Dinar minted in Baghdad 184 AH (800 CE) with the name of Commander of the Faithful Harun al-Rashid and his first Heir, prince al-Amin (Al-Amin was nominated first heir, Al-Ma’mun second and Al-Qasim was third heir.) After Harun’s death in 809 he was succeeded by Al-Amin.

A major revolt led by Rafi ibn al-Layth was started in Samarqand which forced Harun al-Rashid to move to Khorasan. He first removed and arrested Ali bin Isa bin Mahan but the revolt continued unchecked. (Harun had dismissed Ali and replaced him with Harthama ibn A’yan, and in 808 marched himself east to deal with the rebel Rafi ibn al-Layth, but died in March 809 while at Tus).[61][62] Harun al-Rashid became ill and died very soon after when he reached Sanabad village in Tus and was buried in Dar al-Imarah, the summer palace of Humayd ibn Qahtaba, the Abbasid governor of Khorasan. Due to this historical event, the Dar al-Imarah was known as the Mausoleum of Haruniyyeh. The location later became known as Mashhad («The Place of Martyrdom») because of the martyrdom of Imam al-Ridha in 818.

Legacy[edit]

Al-Rashid become a prominent figure in the Islamic and Arab culture, he has been described as one of the most famous Arabs in history. All the abbassid caliphs after him were his descendants.

About his accession famous scholar Mosuli said:

Did you not see how the sun came out of hiding on Harun’s accession and flooded the world with light[63]

About his reign, Famous Arab historian Al-Masudi said:

So great were the Splendour and riches of his reign, such was its prosperity, that this period has been called «the Honeymoon».[64]

Al-Rashid become the progenitor of subsequent Abbasid caliphs. Al-Rashid nominated his son Muhammad al-Amin as his first heir. Muhammad had an elder half-brother, Abdallah, the future al-Ma’mun (r. 813–833), who had been born in September 786 (six months older than him) However, Abdallah’s mother was a Persian concubine, and his pure Abbasid lineage gave Muhammad seniority over his half-brother.[65][66] Indeed, he was the only Abbasid caliph to claim such descent.[66] Already in 792, Harun had Muhammad receive the oath of allegiance (bay’ah) with the name of al-Amīn («The Trustworthy»), effectively marking him out as his main heir, while Abdallah was not named second heir, under the name al-Maʾmūn («The Trusted One») until 799.[65][66] and his third son Qasim was nominated third heir, however he never became caliph.

Among his sons, al-Amin became caliph after his death in 809. Al-Amin ruled from 809 to 813, until a civil war broke between him and his brother Abdallah al-Ma’mun (Governor of Khorasan). The reason of war were that caliph al-Amin tried to remove al-Ma’mun as his heir. Al-Ma’mun became caliph in 813 and ruled the caliphate for two decades until 833. He was succeeded by another of Harun’s son Abu Ishaq Muhammad (better known as Al-Mu’tasim), his mother was Marida, a concubine.[67][68]

In popular culture[edit]

- In Shinobu Ohtaka’s Magi: The Labyrinth of Magic, the former king of Balbadd is called Rashid Saluja. In the spin-off Adventure of Sinbad, Rashid’s alias is Harun.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a short poem titled «Haroun Al Raschid».

- O. Henry uses the character in his story «The Caliph And The Cad». The theme of the story is «turning the tables on Haroun al Raschid».

- Alfred Tennyson wrote a poem in his youth entitled «Recollections Of The Arabian Nights». Every stanza (except the last one) ends with «of good Haroun Alraschid».

- Harun al-Rashid was a main figure and character in several of the stories in some of the oldest versions of the One Thousand and One Nights.

Harun al-Rashid from the book Kitab khizanat al-ayyam fī tarajim al-ʻizam, first published in New york in 1899

- The Indian television series Alif Laila (1993–1997), an adaptation of the Arabian Nights, features several tales involving the caliph from the classic collection of stories.[69]

- Hārūn ar-Rashīd figures throughout James Joyce’s Ulysses, in a dream of Stephen Dedalus, one of the protagonists. Stephen’s efforts to recall this dream continue throughout the novel, culminating in the novel’s fifteenth episode, wherein some characters also take on the guise of Hārūn.

- Harun al-Rashid is celebrated in a 1923 poem by W. B. Yeats, «The Gift of Harun al-Rashid».[70][71]

- A story of one of Harun’s wanderings provides the climax to the narrative game of titles at the end of Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler (1979). In Calvino’s story, Harun wanders at night, only to be drawn into a conspiracy in which he is selected to assassinate the Caliph Harun-al-Rashid.

- In Charles Dickens’ 1842 travelogue, American Notes for General Circulation, he compares American supporters of slavery to the «Caliph Harun al-Rashid in his angry robe of scarlet».

- The two protagonists of Salman Rushdie’s 1990 novel Haroun and the Sea of Stories are Haroun and his father Rashid Khalifa.

An imaginary sketch representing Hārūn al-Rashid from a book entitled Sayr Mulhimah: Min al-Sharq wa-al-Gharb, first translated into Arabic and published in Egypt, 1381 AH/1961

- In the Sten science fiction novels by Allan Cole and Chris Bunch, the character of the Eternal Emperor uses the name «H. E. Raschid» when incognito; this is confirmed, in the final book of the series, as a reference to the character from Burton’s translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night.

- The movie The Golden Blade (1952), starring Rock Hudson and Piper Laurie depicts the adventures of Harun who uses a magic sword to free a fairy-tale Baghdad from Jafar, the evil usurper of the throne. After he finally wins the hand of princess Khairuzan she awards him the title Al-Rashid («the righteous»).

- The comic book The Sandman features a story (issue 50, «Ramadan») set in the world of the One Thousand and One Nights, with Hārūn ar-Rashīd as the protagonist. It highlights his historical and mythical role as well as his discussion of the transitory nature of power. The story is included in the collection The Sandman: Fables and Reflections.

- Haroun El Poussah in the French comic strip Iznogoud is a satirical version of Hārūn ar-Rashīd.

- In Quest for Glory II, the sultan who adopts the Hero as his son is named Hārūn ar-Rashīd. He is often seen prophesying on the streets of Shapeir as The Poet Omar.

- Harun al-Rashid appears as the leader of Arabia in the video game Civilization V.[72]

- Future US President Theodore Roosevelt, when he was a New York Police Department Commissioner, was called in the local newspapers «Haroun-al-Roosevelt».

- In The Master and Margarita, by novelist Mikhail Bulgakov, Harun al-Rashid is referenced by the character Korovyev in which he warns a door man not to judge him «by [his] suit», and to reference the story of «the famous caliph, Harun al-Rashid».

Sketch drawing of Harun al-Rashid by poet and visual artist Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931)

- In the 1924 film Waxworks, a poet is hired by a wax museum proprietor to write back-stories for three wax models. Among these wax models is Harun al-Rashid, played by Emil Jannings.

- In the 2006 novel Variable Star by Robert Heinlein and Spider Robinson, chapter 1 is prefaced with a quotation from Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s «Recollections of the Arabian Nights» regarding «good Harun Alrashid», the relevance of which becomes apparent in chapter 2 when one character relates stories (probably apocryphal and presumably drawn from Tennyson) of Harun al-Rahsid to another character in order to use them as an analogy.

- The second chapter in the novel Prince Otto by Robert Louis Stevenson has the title «In which the Prince Plays Haroun al-Raschid».

- Haroun al-Rashid has a character page in the video game Crusader Kings II, and it is possible to play as his descendants of the Abbasid dynasty.

- Harun al-Rashid appears in the children’s comic book Mampato, in the stories «Bromiznar de Bagdad» and «Ábrete Sesamo», by the Chilean author Themo Lobos. In this story, al-Rashid is shown at first as lazy and indolent, but after a series of adventures he decides to take the leading role against an evil vizier and help the main character, Mampato.

- Frank Lloyd Wright designed a monument to al-Rashid as part of his proposed 1957 urban renewal plan for Baghdad, Iraq.[73]

- In his book The Power Broker, Robert Caro compares New York City mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia to Harun al-Rashid in the way each «roam[ed] his domain.»[74]

- The Syrian television series Harun Al-Rashid (2018), starring Kosai Khauli, Karis Bashar, and Yasser Al-Masri focuses on Harun and his relation with his brother Caliph Al-Hadi, and that preceded Harun’s ascent to the Caliphate. It also focuses on his relations with his elder sons and nomination of Al-Amin and Al-Ma’mun as heir.

See also[edit]

- Isma’il ibn Salih ibn Ali al-Hashimi

- Abd al-Malik ibn Salih

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Audun Holme, Geometry: Our Cultural Heritage p. 150.

- ^ André Clot, Harun al-Rashid and the world of the thousand and one nights, p. 97.

- ^ Royal Frankish Annals, DCCCVII.

- ^ Charlemagne: Translated sources, p. 98.

- ^ André Clot, Harun al-Rashid and the world of the thousand and one nights.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 38.

- ^ Watt, William Montgomery (20 March 2022). Hārūn al-Rashīd. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 36.

- ^ New Arabian nights’ entertainments, Volume 3

- ^ Masʻūdī, Paul Lunde, Caroline Stone, The meadows of gold: the Abbasids page 62

- ^ a b Bobrick 2012, p. 42.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 46.

- ^ «Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid Caliph Who Inspired the ‘Arabian Nights’«. ThoughtCo. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G.; Sabagh, Georges (19 November 1998). The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521591850.

- ^ Lodovico Antonio Muratori, Giuseppe Catalani (1742),Annali d’Italia: Dall’anno 601 dell’era volare fino all’anno 840, Monaco, page 465. Muratori describes only some of these gifts.

- ^ Tarikh ath-Thabari 4/668–669

- ^ Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidaya wa’l-Nihaya v 13 p. 650

- ^ Mukhtar al-Abadi, Ahmad (14 September 2019). In Abbasid and Andalusian History. Ain University Library. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ C.E, Bosworth (January 1989). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30: The ‘Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid A.D. 785-809/A.H. 169-193. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-88706-564-4. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Dennis Bloodworth, Ching Ping Bloodworth (2004). The Chinese Machiavelli: 3000 years of Chinese statecraft. Transaction Publishers. p. 214. ISBN 0-7658-0568-5. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Herbert Allen Giles (1926). Confucianism and its rivals. Forgotten Books. p. 139. ISBN 1-60680-248-8. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ^ Marshall Broomhall (1910). Islam in China: a neglected problem. London: Morgan & Scott, ltd. pp. 25, 26. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ^ Bajpai 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Bajpai 1981, p. 55.

- ^ Chaliand, Gérard (1970). Nomadic Empires: From Mongolia to the Danube. Transaction Publishers. Retrieved 1 September 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Luciano Petech, A Study of the Chronicles of Ladakh (Calcutta, 1939), pp. 73–73.

- ^ Luciano Petech, A Study of the Chronicles of Ladakh (Calcutta, 1939), pp. 55–85.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 40.

- ^ Abbott 1946, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Abbott 1946, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e al-Tabari & Bosworth 1989, p. 326.

- ^ a b c Abbott 1946, p. 137.

- ^ a b Abbott 1946, p. 138.

- ^ al-Sāʿī, Toorawa & Bray 2017, p. 14.

- ^ Abbott 1946, pp. 138–39.

- ^ al-Tabari & Bosworth 1989, p. 327.

- ^ Meadows Of Gold. Taylor & Francis. 2013. p. 462. ISBN 978-1-136-14522-3.

- ^ Abbott 1946, pp. 141–42.

- ^ Abbott 1946, p. 143.

- ^ a b al-Tabari & Bosworth 1989, p. 327.

- ^ a b c Abbott 1946, p. 144.

- ^ a b al-Tabari & Bosworth 1989, p. 328.

- ^ al-Sāʿī, Toorawa & Bray 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Abbott 1946, p. 146.

- ^ Caswell, Fuad Matthew (2011). The Slave Girls of Baghdad: The Qiyan in the Early Abbasid Era. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 73–81. ISBN 978-1-78672-959-0.

- ^ a b al-Sāʿī, Toorawa & Bray 2017, p. 13.

- ^ Abbott 1946, pp. 157.

- ^ Abbott 1946, pp. 149–50.

- ^ al-Tabari & Bosworth 1989, pp. 327–28.

- ^ Al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold, p. 94.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 45.

- ^ a b Bobrick 2012, p. 62.

- ^ a b Bobrick 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 42

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Bobrick 2012, p. 57.

- ^ Bosworth 1995, pp. 385–386.

- ^ «Hārūn al-Rashīd | ʿAbbāsid caliph | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- ^ «Harun al-Rashid: and the World of the Thousand and One Nights». Youth and Splendour of the Well-Guided One, part 2. André Clot. 2014. ISBN 9780863565588.

- ^ «Harun al-Rashid: and the World of the Thousand and One Nights». The Horsemen of Allah, part 1. André Clot. 2014. ISBN 9780863565588.

- ^ a b Gabrieli 1960, p. 437.

- ^ a b c Rekaya 1991, p. 331.

- ^ Bosworth 1993, p. 776.

- ^ Masudi 2010, p. 222.

- ^ «Alif Laila DVD [20 Disc Set]». Induna.com.

- ^ «Yeats Poems Titles». Csun.edu. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Zacny, Rob (24 December 2010). «Civilization V Field Report 2». GamePro. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011.

- ^ Levine, Neil (1 December 2015). The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691167534.

- ^ Caro, Robert (1974). The Power Broker. New York: Vintage Books. p. 444.

Notes[edit]

- ^ English: Commander of the Faithful

- ^ Dinar of Harun al-Rashid dated AH 171 (787–788 CE)

- ^ 20 more known concubines

- ^ First heir-apparent

- ^ Second heir-apparent

- ^ Al-Qasim was the third heir, however, he was removed by his elder brothers

- ^ Al-Ma’mun had made no official provisions for his succession during his reign. According to the account of al-Tabari, on his deathbed al-Ma’mun dictated a letter nominating his brother Abu Ishaq Muhammad as his successor, He was acclaimed as caliph on 9 August, with the regnal title of al-Mu’tasim bi’llah

- ^

Sources[edit]

- Abbott, Nabia (1946). Two Queens of Baghdad: Mother and Wife of Hārūn Al Rashīd. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-86356-031-6.

- al-Sāʿī, Ibn; Toorawa, Shawkat M.; Bray, Julia (2017). كتاب جهات الأئمة الخلفاء من الحرائر والإماء المسمى نساء الخلفاء: Women and the Court of Baghdad. Library of Arabic Literature. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-6679-3.

- al-Tabari, Muhammad Ibn Yarir (1989). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30: The ‘Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid A.D. 785-809/A.H. 169-193. Bibliotheca Persica. Translated by C. E. Bosworth. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-564-4.

- Bobrick, Benson (2012). The Caliph’s Splendor: Islam and the West in the Golden Age of Baghdad. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1416567622.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1995). «Rāfiʿ b. al- Layt̲h̲ b. Naṣr b. Sayyār». In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1993). «al-Muʿtaṣim Bi’llāh». In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 776. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Gabrieli, F. (1960). «al-Amīn». In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 437–438. OCLC 495469456.

- Masudi (2010) [1989]. The Meadows of Gold: The Abbasids. Translated by Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0246-5.

- Rekaya, M. (1991). «al-Maʾmūn». In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 331–339. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

Further reading[edit]

- al-Masudi, The Meadows of Gold, The Abbasids, transl. Paul Lunde and Caroline Stone, Kegan paul, London and New York, 1989

- al-Tabari «The History of al-Tabari» volume XXX «The ‘Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium» transl. C.E. Bosworth, SUNY, Albany, 1989.

- Clot, André (1990). Harun Al-Rashid and the Age of a Thousand and One Nights. New Amsterdam Books. ISBN 0-941533-65-4.

- St John Philby. Harun al Rashid (London: P. Davies) 1933.

- Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, «Two Lives of Charlemagne,» transl. Lewis Thorpe, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1977 (1969)

- John H. Haaren, Famous Men of the Middle Ages [1]

- William Muir, K.C.S.I., The Caliphate, its rise, decline, and fall [2]

- Theophanes, «The Chronicle of Theophanes,» transl. Harry Turtledove, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1982

- Norwich, John J. (1991). Byzantium: The Apogee. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-53779-3.

- Zabeth, Hyder Reza (1999). Landmarks of Mashhad. Alhoda UK. ISBN 964-444-221-0.

External links[edit]

- Brentjes, Sonja (2007). «Hārūn al‐Rashīd». In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 474–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

|

Harun al-Rashid Abbasid dynasty Born: 763 Died: 809 |

||

| Sunni Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Al-Hadi |

Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate 14 September 786 – 24 March 809 |

Succeeded by

Al-Amin |

This article is about an Abbasid caliph. For other uses, see Haroon Rashid.

| Harun al-Rashid هَارُون الرَشِيد |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Gold dinar of Harun al-Rashid[b] |

||

| 5th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | ||

| Reign | 14 September 786 – 24 March 809 | |

| Predecessor | Al-Hadi | |

| Successor | Al-Amin | |

| Born | 17 March 763 or February 766 Ray, Jibal, Abbasid Caliphate (in present-day Tehran Province, Iran) |

|

| Died | 24 March 809 (aged 43) Tus, Khorasan, Abbasid Caliphate (in present-day Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran) |

|

| Burial |

Tomb of Harun al-Rashid in Imam Reza Mosque, Mashhad, Iran |

|

| Spouse |

|

|

| Issue |

|

|

|

||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | |

| Father | Al-Mahdi | |

| Mother | Al-Khayzuran | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Abu Ja’far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi (Arabic: أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (Arabic: هَارُون ابْنِ ٱلْمَهْدِيّ, romanized: Hārūn ibn al-Mahdī; c. 763 or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid (Arabic: هَارُون الرَشِيد, romanized: Hārūn al-Rashīd)[h] was the fifth Abbasid caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, reigning from September 786 until his death. His reign is traditionally regarded to be the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age. His epithet «al-Rashid» translates to «the Orthodox», «the Just», «the Upright», or «the Rightly-Guided».

Harun established the legendary library Bayt al-Hikma («House of Wisdom») in Baghdad in present-day Iraq, and during his rule Baghdad began to flourish as a world center of knowledge, culture and trade.[1] During his rule, the family of Barmakids, which played a deciding role in establishing the Abbasid Caliphate, declined gradually. In 796, he moved his court and government to Raqqa in present-day Syria.

A Frankish mission came to offer Harun friendship in 799. Harun sent various presents with the emissaries on their return to Charlemagne’s court, including a clock that Charlemagne and his retinue deemed to be a conjuration because of the sounds it emanated and the tricks it displayed every time an hour ticked.[2][3][4] Portions of the fictional One Thousand and One Nights are set in Harun’s court and some of its stories involve Harun himself.[5] Harun’s life and court have been the subject of many other tales, both factual and fictitious.

Early life[edit]

Hārūn was born in Rey, then part of Jibal in the Abbasid Caliphate, in present-day Tehran Province, Iran. He was the son of al-Mahdi, the third Abbasid caliph (r. 775–786), and his wife al-Khayzuran, (a former slave girl from Yemen) who was a woman of strong and independent personality who greatly and determinedly influenced affairs of state in the reigns of her husband and sons. Growing up Harun studied history, geography, rhetoric, music, poetry, and economics. However, most of his time was dedicated to mastering hadith and the Quran. In addition, he underwent advanced physical education as a future mujahid, and as a result, he practiced swordplay, archery, and learned the art of war.[6] His birth date is debated, with various sources giving dates from 763 to 766.[7]

Before becoming a caliph, in 780 and again in 782, Hārūn had already nominally led campaigns against the Caliphate’s traditional enemy, the Eastern Roman Empire, ruled by Empress Irene. The latter expedition was a huge undertaking, and even reached the Asian suburbs of Constantinople. According to the Muslim chronicler Al-Tabari, the Byzantines had lost tens of thousands of soldiers during Harun’s campaign, and Harun employed 20,000 mules to carry the booty back. Upon his return to the Abbasid realm, the cost of a sword fell to one dirham and the price of a horse to a single gold Byzantine dinar.[8]

Harun’s raids against the Byzantines elevated his political image and once he returned, he was given the alias «al-Rashid», meaning «the Rightly-Guided One». He was promoted to crown prince and given the responsibility of governing the empire’s western territories, from Syria to Azerbaijan.[9]

Caliphate[edit]

Hārūn became caliph in 786 when he was in his early twenties. At the time, he was tall, good looking, and slim but strongly built, with wavy hair and olive skin.[10] On the day of accession, his son al-Ma’mun was born, and al-Amin some little time later: the latter was the son of Zubaida, a granddaughter of al-Mansur (founder of the city of Baghdad); so he took precedence over the former, whose mother was a Persian. Upon his accession, Harun led Friday prayers in Baghdad’s Great Mosque and then sat publicly as officials and the layman alike lined up to swear allegiance and declare their happiness at his ascent to Amir al-Mu’minin.[11] He began his reign by appointing very able ministers, who carried on the work of the government so well that they greatly improved the condition of the people.[12]

Under Hārūn al-Rashīd’s rule, Baghdad flourished into the most splendid city of its period. Tribute paid by many rulers to the caliph funded architecture, the arts and court luxuries.

In 796, Hārūn moved the entire court to Raqqa on the middle Euphrates, where he spent 12 years, most of his reign. He appointed the Hanafi jurist Muhammad al-Shaybani as qadi (judge), but dismissed him in 803. He visited Baghdad only once. Several reasons may have influenced the decision to move to Raqqa: its closeness to the Byzantine border, its excellent communication lines via the Euphrates to Baghdad and via the Balikh river to the north and via Palmyra to Damascus, rich agricultural land, and the strategic advantage over any rebellion which might arise in Syria and the middle Euphrates area. Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, in his anthology of poems, depicts the splendid life in his court. In Raqqa the Barmakids managed the fate of the empire, and both heirs, al-Amin and al-Ma’mun, grew up there. At some point the royal court relocated again to Al-Rayy, the capital city of Khorasan, where the famous philologist and leader of the Kufan school, Al-Kisa’i, accompanied the caliph with his entourage. When al-Kisa’i became ill while in Al-Rayy, it is said that Harun visited him daily. It seems al-Shaybani and al-Kisa’i both died there on the same day in 804. Harun is quoted as saying: «Today Law and Language have died».

For the administration of the whole empire, he fell back on his mentor and longtime associate Yahya bin Khalid bin Barmak. Rashid appointed him as his vizier with full executive powers, and, for seventeen years, Yahya and his sons served Rashid faithfully in whatever assignment he entrusted to them.[13]

Harun made pilgrimages to Mecca by camel (2,820 km or 1,750 mi from Baghdad) several times, e.g., 793, 795, 797, 802 and last in 803. Tabari concludes his account of Harun’s reign with these words: «It has been said that when Harun ar-Rashid died, there were nine hundred million odd (dirhams) in the state treasury.»[14]

According to Shia belief, Harun imprisoned and poisoned Musa ibn Ja’far, the 7th Imam, in Baghdad.

Under al-Rashid, each city had its own law enforcement, which besides keeping order was supposed to examine the public markets in order to ensure, for instance, that proper scales and measures were used; enforce the payment of debts; and clamp down on illegal activities such as gambling, usury, and sales of alcohol.[15]

Harun was a great patron of art and learning, and is best known for the unsurpassed splendor of his court and lifestyle. Some of the stories, perhaps the earliest, of «The Thousand and One Nights» were inspired by the glittering Baghdad court. The character King Shahryar (whose wife, Scheherazade, tells the tales) may have been based on Harun himself.[16]

Advisors[edit]

A silver dirham minted in Madinat al-Salam (Bagdad) in 170 AH (786 CE). At the reverse, the inner marginal inscription says: «By order of the slave of God, Harun, Commander of the Faithful»

Hārūn was influenced by the full will of his powerful and influential mother in the governance of the empire until her death in 789. His vizier (chief minister) Yahya the Barmakid, Yahya’s sons (especially Ja’far ibn Yahya), and other Barmakids generally controlled the administration. The position of Persians in the Abbasid caliphal court reached its peak during al-Rashid’s reign.[17]

The Barmakids were an Iranian family (from Balkh) that dated back to the Barmak, a hereditary Buddhist priest of Nava Vihara, who converted after the Islamic conquest of Balkh and became very powerful under al-Mahdi. Yahya had helped Hārūn to obtain the caliphate, and he and his sons were in high favor until 798, when the caliph threw them in prison and confiscated their land. Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari dates this event to 803 and lists various reasons for it: Yahya’s entering the Caliph’s presence without permission; Yahya’s opposition to Muhammad ibn al Layth, who later gained Harun’s favour; and Ja’far’s release of Yahya ibn Abdallah ibn Hasan, whom Harun had imprisoned.

The fall of the Barmakids is far more likely due to their behaving in a manner that Harun found disrespectful (such as entering his court unannounced) and making decisions in matters of state without first consulting him.[citation needed] Al-Fadl ibn al-Rabi succeeded Yahya the Barmakid as Harun’s chief minister.

Diplomacy[edit]

Harun al-Rashid at left receiving a delegation sent by Charlemagne to his court in Baghdad.

1864 painting by Julius Köckert.

Both Einhard and Notker the Stammerer refer to envoys traveling between the courts of Harun and Charlemagne, king of the Franks, and entering friendly discussions about Christian access to holy sites and gift exchanges. Notker mentions Charlemagne sent Harun Spanish horses, colorful Frisian cloaks and impressive hunting dogs. In 802 Harun sent Charlemagne a present consisting of silks, brass candelabra, perfume, balsam, ivory chessmen, a colossal tent with many-colored curtains, an elephant named Abul-Abbas, and a water clock that marked the hours by dropping bronze balls into a bowl, as mechanical knights – one for each hour – emerged from little doors which shut behind them. The presents were unprecedented in Western Europe and may have influenced Carolingian art.[18] This exchange of embassies was due to the fact that Harun was interested, like Charlemagne, in subduing the Umayyad emirs of Córdoba. Also, the common enmity against the Byzantines was what brought Harun closer to the contemporary Charlemagne.

When the Byzantine empress Irene was deposed in 802, Nikephoros I became emperor and refused to pay tribute to Harun, saying that Irene should have been receiving the tribute the whole time. News of this angered Harun, who wrote a message on the back of the Byzantine emperor’s letter and said, «In the name of God the most merciful, From Amir al-Mu’minin Harun ar-Rashid, commander of the faithful, to Nikephoros, dog of the Romans. Thou shalt not hear, thou shalt behold my reply». After campaigns in Asia Minor, Nikephoros was forced to conclude a treaty, with humiliating terms.[19][20] According to Dr Ahmad Mukhtar al-Abadi, it is due to the particularly fierce second retribution campaign against Nikephoros, that the Byzantine practically ceased any attempt to incite any conflict against the Abbasid again until the rule of Al-Ma’mun.[21][22]

An alliance was established with the Chinese Tang dynasty by Ar-Rashid after he sent embassies to China.[23][24] He was called «A-lun» in the Chinese Tang Annals.[25] The alliance was aimed against the Tibetans.[26][27][28][29][30]

When diplomats and messengers visited Harun in his palace, he was screened behind a curtain. No visitor or petitioner could speak first, interrupt, or oppose the caliph. They were expected to give their undivided attention to the caliph and calculate their responses with great care.[31]

Rebellions[edit]

Because of the Thousand and One Nights tales, Harun al-Rashid turned into a legendary figure obscuring his true historic personality. In fact, his reign initiated the political disintegration of the Abbasid caliphate. Syria was inhabited by tribes with Umayyad sympathies and remained the bitter enemy of the Abbasids, while Egypt witnessed uprisings against Abbasids due to maladministration and arbitrary taxation. The Umayyads had been established in Spain in 755, the Idrisids in Morocco in 788, and the Aghlabids in Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia) in 800. Besides, unrest flared up in Yemen, and the Kharijites rose in rebellion in Daylam, Kerman, Fars and Sistan. Revolts also broke out in Khorasan, and al-Rashid waged many campaigns against the Byzantines.

Al-Rashid appointed Ali bin Isa bin Mahan as the governor of Khorasan, who tried to bring to heel the princes and chieftains of the region, and to reimpose the full authority of the central government on them. This new policy met with fierce resistance and provoked numerous uprisings in the region.

Family[edit]

Harun’s first wife was Zubaidah. She was the daughter of his paternal uncle, Ja’far and maternal aunt Salsal, sister of Al-Khayzuran.[32] They married in 781–82, at the residence of Muhammad bin Sulayman in Baghdad. She had one son, Caliph Al-Amin.[33] She died in 831.[34] Another of his wives was Azizah, daughter of Ghitrif, brother of Al-Khayzuran.[35] She had been formerly married to Sulayman bin Abi Ja’far, who had divorced her.[34] Another was Amat-al-Aziz Ghadir, who had been formerly a concubine of his brother al-Hadi.[35] She had one son Ali.[33] She died in 789.[35] Another wife was Umm Muhammad, the daughter of Salih al-Miskin and Umm Abdullah, the daughter of Isa bin Ali. They married in November-December 803 in Al-Raqqah. She had been formerly been married to Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi, who had repudiated her.[34] Another wife married around the same year was Abbassah, daughter of Sulayman ibn Abi Ja’far.[34] Another wife was Jurashiyyah al-Uthmanniyah. She was the daughter of Abdullah bin Muhammad, and had descended from Uthman, the third Caliph of the Rashidun.[34]

Harun’s earliest known concubine was Hailanah. She had been a slave girl of Yahya ibn Khalid, the Barmakid. It was she who begged him, while he was yet a prince, to take her away from the elderly Yahya. Harun then approached Yahya, who presented him with the girl. She died three years later[36] in 789–90,[37] and Harun mourned her deeply.[36] Another concubine was Dananir. She was a Barmakid, and had been formerly a slave girl of Yahya ibn Khalid. She had been educated at Medina and had studied instrumental and vocal music.[38] Another concubine was Marajil. She was a Persian, and came from distant Badhaghis in Persia. She was one of the ten maids presented to Harun. She gave birth to Abdullah (future caliph Al-Ma’mun) on the night of Harun’s accession to the throne, in September 786, in whose birth she died. Her son was then adopted by Zubaidah.[33] Another concubine was Qasif, mother of Al-Qasim. He was Harun’s second son, born to a concubine mother. Harun’s eldest daughter Sukaynah was also born to her.[39]

Another concubine was Maridah. Her father was Shabib.[40] She was a Sogdian, and was born in Kufah. She was one of the ten maids presented to Harun by Zubaidah. She had five children. These were Abu Ishaq (future Caliph Al-Mu’tasim), Abu Isma’il, Umm Habib, and two others whose names are unknown. She was Harun’s favourite concubine.[41] Some other favourite concubines were, Dhat al-Khal, Sihr, and Diya. Diya passed away, much to Harun’s sorrow.[42] Dhat al-Khal also known as Khubth[43] was a songstress, belonging to a slave-dealer who was himself a freedman of Abbasah, the sister of Al-Rashid. She caught the fancy of Ibrahim al-Mausili, whose songs in praise of her soon reached Harun’s attention, who bought her for the enormous sum of 70,000 dinars.[44] She was the mother of Harun’s son, Abu al-Abbas Muhammad.[43][44] Sihr was mother of Harun’s daughters, Khadijah[44] and Karib.[45] Another concubine was Inan. Her father was Abdullah.[46] She was born and brought up in the Yamamah in central Arabia. She was a songstress and a poet, and had been a slave girl of Abu Khalid al-Natifi.[47] She bore Harun two sons, both of whom died young. She accompanied him to Khurasan where he, and, soon after, she died.[48] Another was Ghadid, also known as Musaffa, and she was mother of Harun’s daughters, Hamdunah[49] and Fatimah.[45] She was his favourite concubine.[49] Hamdunah and Fatimah married Al-Hadi’s sons, Isma’il and Ja’far respectively.[50]

Another of Harun’s concubines was the captive daughter of a Greek churchman of Heraclea acquired with the fall of that city in 806. Zubaidah once more presented him with one of her personal maids who had caught his fancy. Harun’s half-brother, while governor of Egypt from 795 to 797, also sent the him an Egyptian maid who immediately won his favour.[51] Some other concubines were namely: Ri’m, mother of Salih; Irbah, mother of Abu Isa Muhammad; Sahdhrah, mother of Abu Yaqub Muhammad; Rawah, mother of Abu Sulayman Muhammad; Dawaj, mother of Abu Ali Muhammad; Kitman, mother of Abu Ahmad Muhammad; Hulab, mother of Arwa; Irabah, mother of Umm al-Hassan; Sukkar, mother of Umm Abiha; Rahiq, mother of Umm Salamah; Khzq, mother of Umm al-Qasim; Haly, mother of Umm Ja’far Ramlah; Aniq, mother of Umm Ali; Samandal, mother of Umm al-Ghaliyah; Zinah, mother of Raytah.[52]

Anecdotes[edit]

Many anecdotes attached themselves to the person of Harun al-Rashid in the centuries following his rule. Saadi of Shiraz inserted a number of them into his Gulistan.

Al-Masudi relates a number of interesting anecdotes in The Meadows of Gold that illuminate the caliph’s character. For example, he recounts Harun’s delight when his horse came in first, closely followed by al-Ma’mun’s, at a race that Harun held at Raqqa. Al-Masudi tells the story of Harun setting his poets a challenging task. When others failed to please him, Miskin of Medina succeeded superbly well. The poet then launched into a moving account of how much it had cost him to learn that song. Harun laughed and said that he did not know which was more entertaining, the song or the story. He rewarded the poet.[53]

There is also the tale of Harun asking Ishaq ibn Ibrahim to keep singing. The musician did so until the caliph fell asleep. Then, strangely, a handsome young man appeared, snatched the musician’s lute, sang a very moving piece (al-Masudi quotes it) and left. On awakening and being informed of that, Harun said Ishaq ibn Ibrahim had received a supernatural visitation.

Shortly before he died, Harun is said to have been reading some lines by Abu al-Atahiya about the transitory nature of the power and pleasures of this world, an anecdote related to other caliphs as well.

Every morning, Harun gave one thousand dirhams to charity and made one hundred prostrations a day.[14] Harun famously used to look up at rain clouds in the sky and said: «rain where you like, but I will get the land tax!»[54]

Harun was terrified for his soul in the afterlife. It was reported that he quickly cried when he thought of God and read poems about the briefness of life.[55]

Soon after he became caliph, Harun asked his servant to bring him Ibn al-Sammak, a renowned scholar, to obtain wisdom from him. Harun asked al-Sammak what he would like to tell him. Al-Sammak replied, «I would like you always to remember that one day you will stand alone before your God. You will then be consigned either to Heaven or to Hell.» That was too harsh for Harun’s liking, and he was obviously disturbed. His servant cried out in protest that the Prince of the Faithful will definitely go to heaven after he has ruled justly on earth. However, al-Sammak ignored the interruption and looked straight into the eyes of Harun and said that «you will not have this man to defend you on that day.»[55]