В романе-антиутопии “451 градус по Фаренгейту” герои живут в американском городе будущего, где запрещены книги и чтение. Описание общественных порядков в городе, где проживают главные герои “451 градус по Фаренгейту”, шокирует простого читателя. Имя американского писателя входит в список гениальных антиутопистов. В своих книгах Рэй Брэдбери часто поднимает тему будущего человечества, неминуемой деградации из-за потери духовности. Произведение, как это случается с фантастикой, в чём-то предсказало будущее — от технических мелочей до моральных проблем.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 36 лет.

Характеристика героев “451 градус по Фаренгейту”

Главные герои

Гай Монтэг

Пожарный, мужчина средних лет.

Жизнь Гая ограничена работой и отдыхом, никаких мыслей и мечтаний, новые знания запрещены: они разрушают умы людей. Мир Гая динамичен и примитивен. Как-то он встречает соседку Клариссу, которая переворачивает его мировосприятие одним вопросом: счастлив ли он? На работе нервничают из-за его интереса к пожарным прошлого (которые тушили, а не устраивали пожары). Гай встречается с профессором Фабером, знакомится с литературой, и его жизнь обретает смысл. Преданный женой, он оказывается в розыске, бежит из города.

Милдред

Супруга Гая Монтэга, около 30 лет.

Человек без мыслей и эмоций, ограниченная, пустая. Живёт сериалами и телешоу, практически не вынимает наушники из ушей, из-за чего научилась читать по губам. Мечтает о четвёртом телевизоре-стене, чтобы постоянно смотреть его. Она абсолютно чужой человек для Гая, не понимает его, заботится о личном комфорте. У пары нет детей, потому что Милдред не хочет.

Кларисса Маклеллан

Молодая соседка семьи Монтэгов.

Девушка, непохожая на остальных. Не посещает школу (там не задают вопросов), боится беспорядков, из-за которых ученики стреляют друг в друга. Девушка никуда не спешит, умеет наслаждаться тишиной и окружающим миром. Они с Гаем часто беседуют о книгах, о природе. Девушка внезапно исчезает. Позже от жены Гай узнаёт, что она погибла в автокатастрофе и её семья переехала.

Фабер

Профессор, бывший преподаватель английского языка.

Тайно хранит литературу, изобретает книгопечатную технику. Находит в Монтэге единомышленника, они работают сообща. Перед началом войны, когда Гая объявляют в розыск, подсказывает, куда идти, чтобы спастись и встретить нужных людей.

Хитрый и начитанный человек. Несмотря на ум и рассудительность, считает, что книги вредны для людей. Он ближе к обществу потребителей. Выделяться из толпы — опасно, все должны быть равны, в этом состоит благо общества и счастье. Монтэгу приходится направить свой огнемёт на Битти, когда они сжигают дом Гая, так как из-за капитана может пострадать профессор.

Второстепенные персонажи

Подруги Милдред

В своей женской компании считают отсутствие мужа высшим благом. Находятся у неё в гостях, когда Гай предлагает им почитать книги и рассказывает о своих взглядах. Шокированные, женщины быстро покидают дом. Спустя какое-то время они или Милдред докладывают об инакомыслии Гая властям.

Посмотрите, что еще у нас есть:

Тест по произведению

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Renat Gasanov

11/12

-

Амелия Лисовая

10/12

-

Фатиме Халилова

12/12

-

Глеб Харисов

10/12

-

Ольга Коробкова

12/12

-

Александр Скрементов

11/12

-

Людмила Шулешко

8/12

-

Aybiyke Omurzakova

12/12

-

Алина Солодова

12/12

-

Anter Givemechese

12/12

История создания

Перед тем как изучать героев произведения, необходимо узнать, как именно появилась идея написать книгу, и почему оно имеет такое странное название. Американский писатель начал свою работу после просмотра нацистской кинохроники. В фильме демонстрировалось публичное сожжение книг авторов, которые своими строками противоречили социалистической идеологии.

Писателя возмущало такое обращение с книгами. По его словам, уничтожение литературы равно тому, как Гитлер убивал ни в чем не повинных людей в концлагерях. Автор еще с юношества считал, что человеческий разум и дух очень тесно связан с книгами. Именно поэтому он так относился к нацистскому произволу. Поскольку повлиять на это было невозможно, Брэдбери принялся за написание романа. Он хотел своими строками донести всю суть произвола, который длился не один год.

Основу произведения составляет рассказ «Пожарный», который, к сожалению, так и не был опубликован. Антиутопический роман Брэдбери писал, находясь в библиотеке Лос-Анджелеса. Впервые сочинение было опубликовано в 1953 году. Но перед тем как книга была издана, автору пришлось внести множество поправок. Критики утверждали, что произведение содержит ругательные слова, которые не пропускает цензура.

Смысл названия романа очень тесно связан с книгами. Дело в том, что 452 градус по Фаренгейту — это температура, при которой происходит возгорание бумаги.

Основные персонажи

Герои «451 градус по Фаренгейту» очень разные и имеют свою точку зрения. Только их характеристика дает читателю понять, какую роль они играют:

- Гай Монтэг (Montag) — мужчина сорока лет, пожарный. Вся его жизнь заключена только в работе и отдыхе. Он не умеет мечтать и фантазировать, из-за этого мир героя стал примитивным. Однажды он встретил свою соседку, которая перевернула его взгляды на жизнь одним незамысловатым вопросом, счастлив ли он. В произведении автор представил его как обиженного мужчину, которого предала жена, и он подался в бега.

- Милдред (Mildred) — женщина тридцати лет, жена Гая. Она живет только сериалами и обсуждениями телешоу. Ее разум не позволяет думать о прекрасном. Это пустая и ограниченная женщина, которая заботится только о себе. Между ними давно нет никакой связи. В браке детей они так и не нажили, так как героиня не хотела этого.

- Кларисса Макленанд — молодая девушка, живущая по соседству с семьей Монтэг. Она особенная и непохожа на других. Девушка не посещает школу и боится различного рода беспорядков. У героини очень тонкая душа, она любит наслаждаться тишиной и ценит каждую прожитую минуту. С Гаем она очень часто беседовала, рассуждая о литературе и природе. Вскоре она внезапно исчезла. Монтэг через время узнал, что она погибла в аварии, а ее семья переехала.

- Фабер — бывший учитель английского языка и профессор, положительный герой. Он втайне пытается создать книгопечатное оборудование. Кроме того, он незаконно хранит дома литературу. Познакомившись с Гаем, мужчина видит в нем единомышленника. Он помогает главному герою скрыться от преследования.

- Битти — начальник Монтэга, хитрый и опасный человек. Несмотря на свою воспитанность и образованность, он считает, что книги очень вредны и разрушают разум.

- Подруги Милдред — пустые и глупые женщины. Находясь в компании, они рассуждают о том, что если мужей не было, они были бы гораздо счастливее. Когда Гай начинает с ними беседовать и предлагает прочесть им несколько книг, они настораживаются и уходят. Вскоре женщины доложили властям о нарушениях героя.

Все персонажи романа имеют свои определенные черты характера, по которым можно оценить их внутренний мир. Нельзя говорить, что они все играют отрицательную роль в жизни друг друга.

Анализ текста

Произведение Брэдбери открывает острую проблему жизни общества, которая остается актуальной и по сегодняшний день. Основной темой романа является роль литературы в жизни человека. Автор без излишеств описал жизнь людей массового потребления, которые не способны самостоятельно мыслить, анализировать и делать соответствующие выводы.

Необразованными людьми легче всего управлять, и этот факт известен правительству, которое законом запрещает использовать литературу. Люди всю информацию узнают из новостей и телепередач, но, как известно, телепрограмма отупляет человека и преподносит все происходящее в выгодном ракурсе.

Описание книги «451 градус по Фаренгейту» дает возможность понять, что основной мыслью повествования является светлое будущее поколений, которое напрямую зависит от прошлого. Выбирая между книгами и телевизором, человек чаще всего предпочитает второе, тем самым подвергается деградации. Такое поведение чревато серьезными последствиями для всего народа, так как оно само себя уничтожает.

Кроме того, в тексте упоминаются следующие темы:

- Семья.

- Ценности.

- Отношения между людьми.

Замыкаясь в себе и не развиваясь духовно, человек лишает себя таких чувств, как сопереживание, любовь и уважение. Эмоциональное отступление от родных людей — это прямая дорога к одиночеству.

Проблематикой романа является манипуляция обществом при помощи СМИ. Своими строками Брэдбери пытался донести лишь одну незамысловатую мысль: при отказе от литературы у общества нет будущего.

- Сочинения

- По литературе

- Другие

- Главные герои романа 451 градус по Фаренгейту Брэдбери

В произведении речь идет о людях, проживающих в Америке, в городе будущего, там запрещается читать книги.

Гай Монтэнг

Мужчина среднего возраста, работает пожарным. В его обязанности входит сжигать все книги Он только и делает, что работает и отдыхает, он ни о чем не думает и не мечтает. Живет примитивно. Гай обрел смысл жизни после того, как встретился с неким ученым Фабером.

И в начале произведения Монтэнг убежден, что правильно поступает, но когда встречает героиню Клариссу, то полностью поменял свое решение и начал читать книги. Он начал стремиться к нравственности. Монтэнга предала супруга и после этого он был в розыске и сбежал.

Следующая героиня-тридцатилетняя жена Гая, по имени Милдрэд. Абсолютно пустая женщина, безэмоциональная. Она только смотрит по телевизору телесериалы и разные шоу. Ее мечта-приобрести очередной огромный телевизор. Она совсем не думает о супруге, а заботиться только о себе. А также не желает заводить ребенка. С супругом ни просто живут под одной крышей, у них давно уже нет никаких связей и абсолютно не интересны друг другу.

Кларисса

Следующая героиня являлась соседка супругов, молодая веселая девушка, которая не ходила в школу, так как у нее страхи из-за того, что учащиеся школы могут устроить стрельбу, либо погибнут в авариях. С Гаем они нашли общий язык и беседовали о природе и книгах. Именно она и подоткнула Гая на переосмысление своей жизни. Однажды Кларисса резко пропала, а позже узнается, что она погибла в аварии.

Фабер

Ученый, преклонного возраста, много повидавший в своей жизни, который хранил книги втайне, а также изобрел печатную машинку. Поддерживал людей, которые тайно хранили хоть часть книг, чтобы их не уничтожили. Он также помогал Гаю искать свой верный путь.

Битти

Хитрый, умный и рассудительный человек, являлся начальником Гая. Хотя сам и начитанный, но считает, что книги приносят вред человеку. Погиб от рук Гая, когда тот выпустил языки пламени и из огнемета.

Подруга Милдред

Незамужняя женщина, которая позже вместе с Милдред докладывают на Гая властям о его нарушениях.

В данном произведении весь мир погряз в каком-то безумии, где происходят странности. Здесь всему человечеству независимо от статуса, были запрещены не то, что читать книги, а даже брать их в руки, а тот, кто нарушит или попытается обойти этот закон, то будет наказан. Пожарные здесь сами устраивают пожары, и, в первую очередь, сжигают книги, чтобы те не попали в чьи-нибудь руки и не были прочитаны, вместо того, чтобы спасать людей и здания от огня. В произведении показан мир через сотни лет, где обладают абсурдные идеи и действия, и вообще происходят страшные вещи.

Характеристика персонажей (2 вариант)

Гай Монтэг

Главным героем является именно пожарный. Он зовется Гаем Монтэгом. Его обязанностью и работой является сжигание литературы, которую нельзя читать. В начале произведения герой предстает перед читателем человеком, который глубоко убежден в правильности того, что он делает. Но скоро он встречает девушку, которая кардинально помогает изменить ему свою жизнь, возможно, в лучшую сторону. Монтэг предпринимает действия, чтобы измениться к лучшему и начинает читать книги. Брэдбери на примере этого персонажа показал эволюцию нравственности.

Милдрет

Милдрет является женой главного героя. Они давно потеряли с мужем душевную связь. Женщина засыпает теперь только в том случае, если глотает таблетки. Иногда ее откачивают от передоза и выводят из комы. Она давно не интересна мужу, а он ей. Они просто существуют вместе в одном доме.

Кларисса

А вот девушка по имени Кларисса является очень молодой, жизнерадостной и веселой. Данный персонаж толкает Монтэга на перемены в жизни. Родители Клариссы – это люди, типа старых. То есть они читали книги, уважали образование. Именно это оказало на ее большое влияние.

Битти

Битти – это непосредственный начальник главного героя. Он начин, умен, но в целом поддерживает систему, которая установилась в данном обществе. Он прикладывает немалое количество усилий, дабы заставить главного героя стать на путь истины, ее читать книги и жить, наслаждаясь обществом потребления. В результате назойливый Битти был убит в порыве ярости главным героем с помощью струи огня.

Фабер

Ну и также еще один немало важный герой «451 градус по Фаренгейту» — это Фабер. Он достаточно стар и много увидел в этой жизни. Помогает тайным любителям книг. Сам является филологом.

О романе

Замечательное произведение, которое давно вошло в золотой фонд мировой фантастики, написано американским мастером слова Рэем Дугласом Брэдбери. Произведение под названием «451 градус по Фаренгейту» относится к жанру повести.

В данном произведении представлен мир через несколько сотен лет, который полностью поглотил не только научный и технический прогресс, но и сожрали абсурдные идее, порождающие не менее странные действия. В мире, представленном Рэем Брэдбери в этой повести, происходят страшные вещи. Мир погряз в безумии и абсурдизме.

Дело в том, что почти все механизировано. Книги запрещены. Категорически, всем людям. Их нельзя держать в руках, не то что бы читать. Тот, кто решит обойти этот закон, получит наказание от властей. Он может даже угодить в больницу для психически нездоровых людей. пожарные занимаются тем, что вместо спасения горящих зданий, библиотек, домов и вообще устранения огня, где он не должен быть, наоборот. Эти люди, которые в нашем понимании должны устранять пожары, разжигают их. Они палят книги в первую очередь, ведь недопустимо дать прочесть их людям.

Также читают:

Картинка к сочинению Главные герои романа 451 градус по Фаренгейту Брэдбери

Популярные сегодня темы

- Портрет Маруси в рассказе В дурном обществе

Девочка Маруся – одна из жительниц подземелья. Ей всего четыре года, но она так много уже настрадалась в жизни. У девочки нет мамы, о ней с братом заботится пан Тыбурций, которого они называют отцом

- Сочинение на тему Безответная любовь

Любовь не всегда дарит человеку ощущение радости. Порой она бывает безответной, и тогда влюблённый страдает от своих чувств. Он может продолжать стучаться в закрытые двери или радоваться за счастье любимого человека

- Можно ли оправдать месть? Итоговое сочинение

Месть – один из самых страшных грехов. Но бывают ли случаи, когда она может быть оправдана? Несмотря на то я считаю, что месть – это намеренное зло, причиненное

- Пушкин

В поэзии А. С. Пушкина отмечается наличие всех форм литературы: от драматических произведений, наполненных серьёзностью, до сказок. Часто и много поэт писал статьи, содержащие критику, занимался исследованиями

- Андрей Штольц как антипод Обломова сочинение

Суть произведения И.Гончарова «Обломов» во многом раскрывается благодаря антитезе, которая сталкивает друг с другом двух противоположных по своему характеру и взглядам на жизнь героев – Илью Ильича Обломова и Андрея Ивановича Штольца

По роману «Fahrenheit 451» Рэя Брэдбери, его экранизациям и комиксу

451º по Фаренгейту

По роману «Fahrenheit 451» Рэя Брэдбери, его экранизациям и комиксу

Персонажи

- Будем искать среди персонажей фандома

Битти

Beatty

0

1

0

Брандмейстер пожарной части, где работает Монтэг, его непосредственный начальник.

Блэк

Black

1

0

0

Пожарный, коллега Монтэга.

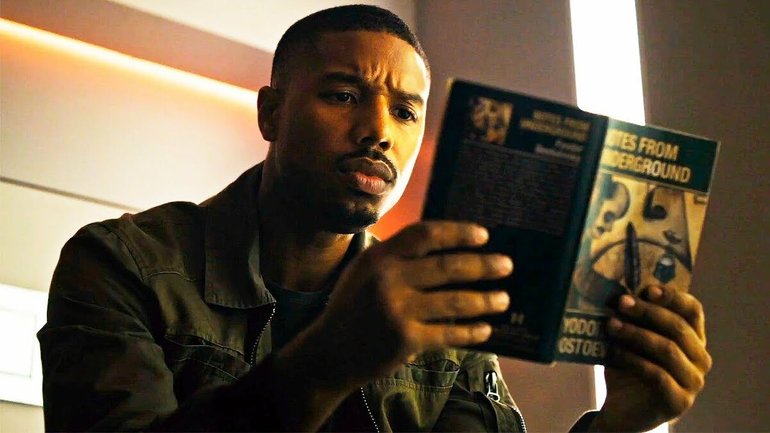

Гай Монтэг

Guy Montag

2

1

0

Главный герой, пожарный. Вначале предстает как обычный пожарный, который без лишних слов выполняет свою работу, но, познакомившись с Клариссой, он начинает воспринимать все по другому и в итоге присоединяется к повстанцам. В книге он белокожий, а в экранизации HBO его сделали темнокожим.

Грэнджер

Granger

1

0

0

Лидер повстанческой группировки, которая помогла Монтэгу сбежать.

Клара Фелпс

Clara Phelps

0

0

0

Подруга Милдред Монтэг, также помешана на телевизионных передачах. Сдала Монтэга властям.

Кларисса МакКлеллан

Clarisse McClellan

1

0

0

Семнадцатилетняя девушка, которую все считают ненормальной из-за того, что она мыслит иначе. Погибла в автокатастрофе.

Милдред Монтэг

Mildred Montag

0

0

0

Жена Гая, она помешана на снотворном и телевизионных передачах. Сдала Монтэга властям.

Стоунмэн

Stoneman

0

0

0

Пожарный, коллега Монтэга.

Фабер

Faber

1

0

0

Бывший профессор английского языка, друг Монтэга и повстанец.

Энн Боулс

Ann Bowles

0

0

0

Подруга Милдред Монтэг, также помешана на телевизионных передачах. Сдала Монтэга властям.

Роман «451 градус по Фаренгейту» Брэдбери написал в 1953 году. Произведение является одним из ярчайших примеров научно-фантастической антиутопии в мировой литературе. На нашем сайте вы можете прочитать краткое содержание «451 градус по Фаренгейту» по частям.

Расшифровку названия в эпиграфе дает сам Брэдбери: «451 градус по Фаренгейту — температура, при которой воспламеняется и горит бумага». В произведении автор размышляет над тем, есть ли у человечества будущее, изображая мир, в котором сжигаются книги, а люди живут только поверхностными, материальными ценностями.

Содержание

- Основные персонажи романа

- Брэдбери «451 градус по Фаренгейту» очень кратко

- Содержание романа «451 градус по Фаренгейту»

- Пересказ «451 градус по Фаренгейту» по частям

- Видео краткое содержание 451 градус по Фаренгейту Брэдбери

Основные персонажи романа

Главные герои:

- Гай Монтэг – пожарный, который сжигал книги; после знакомства с Клариссой пересмотрел свои взгляды на жизнь.

- Кларисса Маклеллан – девушка 17-ти лет, сильно отличалась от сверстников, была любопытной, интересовалась миром; подруга Монтэга.

Другие персонажи:

- Брандмейстер Битти – начальник Монтэга.

- Милред – женщина 30-ти лет, жена Монтэга.

- Фабер – бывший профессор английского языка.

Брэдбери «451 градус по Фаренгейту» очень кратко

Краткое содержание «451 градус по Фаренгейту» Брэдбери:

Государственная власть имеет отдел пожарной охраны с функцией полиции, чьей задачей является отыскивать и сжигать книги. Пожарная бригада используется огнемет, который генерируют тепло ровное 451 градусов по Фаренгейту (232 градусов по Цельсию) — температура, при которой горит бумага.

Все люди, в этом состоянии будущей жизни, не знают угрызений совести, и моральные сомнения полностью устранены в этом обществе.

Вместо этого, население все свое свободное время посвящает примитивным, бессмысленным передачам из негабаритных телевизионных экранов с «плоскими» фильмами и тупой рекламой или, листая бессмысленные журналы, которые не имеют информативного содержания. Целью этого бесчеловечного режима являлось оглупление людей, чтобы не дать им возможность самостоятельно и критически мыслить, не говоря уже о восстании против государственной власти.

Протагонистом в этой истории является пожарный Гай Монтэг, который полностью убежден в правильности этих взглядов и с большой страстью увлечен своей сомнительной деятельностью. Она дает ему ощущение силы на работе и оказывает определенное обаяние на него в течение длительного времени. Возможности для профессиональной карьеры, вдохновляют его.

Необразованный Гай представляет собой среднее население в процессе описываемого мрачного будущего. Тем не менее, он любопытен и скептически настроен. Полностью характеристикам среднего человека соответствует его жена Милдред. Система олицетворена руководителем Гая, капитаном Битти.

Но есть люди, которые находятся в оппозиции к правилам системы и пытаются сформировать свое собственное мнение, самостоятельно определить форму интеллектуальной рефлексии. Это бывший профессор литературы Фабер и Кларисса Мак-Клеллан.

Задачей Гая и его коллег, является поиск книг и уничтожение их огнеметами. Чтение и владение книг строго запрещено государством. За несоблюдение этого требования грозит суровое наказание.

Только тогда, когда он встречает, молодую, красивую Клариссу случайно на улице, он получает первый импульс, чтобы подумать о своих действиях. Она происходит из нетрадиционной семьи, где любят природу и не боготворят гипер технологии своего времени. Кларисса является одним из членов группы диссидентов, которые изучают наизусть целые книги, и компенсируют сгоревшую литературу, слушая друг друга.

Он понимает, что Кларисса — несмотря на свою молодость — более зрелая и умная, чем его тридцатилетняя жена Милдред. Отношения между ней и ее мужем бесстрастны и холодны и ограничиваются только просмотром телевизора. Когда его жена делает попытку покончить жизнь самоубийством, Гай понимает что это не результат внутренних переживаний, а просто она находилась под впечатлением от просмотра телевизора.

После дальнейших встреч с Клариссой он начинает догадываться, что встречается с убежденным противником системы. С другой стороны, он задается вопросом, не влюблен ли он в нее. В любом случае, Кларисса дает ему новую пищу для размышлений и оказывают все большее влияние на него.

Особенно на Гая произвел поступок женщины, уличённой в хранении книг, и которая отказалась покинуть жилище, предназначенное для сожжения. Женщина облила себя керосином и погибла вместе со своими книгами.

Постепенно ход его мыслей меняется, и он решает прочитать книгу, которую надо было сжечь Он начинает читать и в его голову вкрадываются сомнения о правильности его жизни. Его работа доставляет ему все меньше удовольствия, и он мысленно отдаляется все больше и больше от своего государства, и вскоре понимает, что это бесчеловечный режим.

Гай ищет свое место в жизни и встречает в парке старого человека по имени Фабер. Фабер становиться наставником Гая в его становлении как новой личности.

В это время, его жена сообщает о смерти Клариссы. Гай отказывается идти на работу, но его босс Битти навещает его и пытается внушить ему мысли о правильности существующей жизни и строя. После того, как Битти ушел, Гай принес домой несколько книг и попытался приобщить к ним жену и ее подруг, но безуспешно.

После того как Гай пришел на работу последовал вызов пожарной команды для того чтобы сжечь очередной дом. Когда они приезжают на вызов, то оказывается что нужно сжечь дом Гая. Его собственная жена предала его. Гай сжигает книги, и свой собственный дом, но начальник Битти находит рацию с помощью, которой Гай связывался с профессором. Что бы ни выдать профессора. Гай направляет огнемет против начальства Битти и убивает его. За ним начинается преследование как за государственным преступником.

Государство наказывает диссидентов безжалостно, сжигает их книги и дома. Пожарный отдел имеет в своем арсенале «механическую собаку» (искусственная форма жизни с полицейскими полномочиями) для погони за врагами государственной системы. Именно такую собаку и запускают в погоню за Гаем. Но собака убивает другого человека, которого принимают за Гая. По телевизору объявляют о смерти Гая, что дает ему возможность скрыться.

Он присоединяется к группе диссидентов. Грейнджер, начитанный человек, является лидером этих людей. Он сразу же интегрировал Гая в группу, и завязал с ним дружбу. Гай со своими новыми друзьями покидает город и надеются, что в будущем они будут иметь возможность построить новое общество после их возвращения.

В это время начинается война, и история заканчивается бомбардировками родного города ядерными бомбами, в результате чего он был полностью уничтожен.

Читайте также краткое содержание “Каникулы” Р. Брэдбери.

Содержание романа «451 градус по Фаренгейту»

«451 градус по Фаренгейту» Брэдбери краткое содержание:

Америка относительно недалёкого будущего, какой она виделась автору в начале пятидесятых годов, когда и писался этот роман-антиутопия.

Тридцатилетний Гай Монтэг — пожарник. Впрочем, в эти новейшие времена пожарные команды не сражаются с огнём. Совсем даже наоборот. Их задача отыскивать книги и предавать огню их, а также дома тех, кто осмелился держать в них такую крамолу. Вот уже десять лет Монтэг исправно выполняет свои обязанности, не задумываясь о смысле и причинах такого книгоненавистничества.

Встреча с юной и романтичной Клариссой Маклеланд выбивает героя из колеи привычного существования. Впервые за долгие годы Монтэг понимает, что человеческое общение есть нечто большее, нежели обмен заученными репликами. Кларисса резко выделяется из массы своих сверстников, помешанных на скоростной езде, спорте, примитивных развлечениях в «Луна-парках» и бесконечных телесериалах.

Она любит природу, склонна к рефлексиям и явно одинока. Вопрос Клариссы: «Счастливы ли вы?» заставляет Монтэга по-новому взглянуть на жизнь, которую ведёт он — а с ним и миллионы американцев. Довольно скоро он приходит к выводу, что, конечно же, счастливым это бездумное существование по инерции назвать нельзя. Он ощущает вокруг пустоту, отсутствие тепла, человечности.

Словно подтверждает его догадку о механическом, роботизированном существовании несчастный случай с его женой Милдред. Возвращаясь домой с работы, Монтэг застаёт жену без сознания. Она отравилась снотворным — не в результате отчаянного желания расстаться с жизнью, но машинально глотая таблетку за таблеткой.

Впрочем, все быстро встаёт на свои места. По вызову Монтэга быстро приезжает «скорая», и техники-медики оперативно проводят переливание крови с помощью новейшей аппаратуры, а затем, получив положенные пятьдесят долларов, удаляются на следующий вызов.

Монтэг и Милдред женаты уже давно, но их брак превратился в пустую фикцию. Детей у них нет — Милдред была против. Каждый существует сам по себе. Жена с головой погружена в мир телесериалов и теперь с восторгом рассказывает о новой затее телевизионщиков — ей прислали сценарий очередной «мыльной оперы» с пропущенными строчками, каковые должны восполнять сами телезрители.

Три стены гостиной дома Монтэгов являют собой огромные телеэкраны, и Милдред настаивает на том, чтобы они потратились и на установление четвёртой телестены, — тогда иллюзия общения с телеперсонажами будет полной.

Мимолётные встречи с Клариссой приводят к тому, что Монтэг из отлаженного автомата превращается в человека, который смущает своих коллег-пожарных неуместными вопросами и репликами, вроде того: «Были ведь времена, когда пожарники не сжигали дома, но наоборот, тушили пожары?»

Пожарная команда отправляется на очередной вызов, и на сей раз Монтэг испытывает потрясение. Хозяйка дома, уличённая в хранении запрещённой литературы, отказывается покинуть обречённое жилище и принимает смерть в огне вместе со своими любимыми книгами.

На следующий день Монтэг не может заставить себя пойти на работу. Он чувствует себя совершенно больным, но его жалобы на здоровье не находят отклика у Милдред, недовольной нарушением стереотипа. Кроме того, она сообщает мужу, что Клариссы Маклеланд нет в живых — несколько дней назад она попала под автомобиль, и её родители переехали в другое место.

В доме Монтэга появляется его начальник брандмейстер Битти.

Он почуял неладное и намерен привести в порядок забарахливший механизм Монтэга. Битти читает своему подчинённому небольшую лекцию, в которой содержатся принципы потребительского общества, какими видит их сам Брэдбери: «…Двадцатый век. Темп ускоряется. Книги уменьшаются в объёме. Сокращённое издание. Содержание. Экстракт. Не размазывать. Скорее к развязке!..

Произведения классиков сокращаются до пятнадцатиминутной передачи. Потом ещё больше: одна колонка текста, которую можно пробежать глазами за две минуты, потом ещё: десять — двадцать строк для энциклопедического словаря… Из детской прямо в колледж, а потом обратно в детскую».

Разумеется, такое отношение к печатной продукции — не цель, но средство, с помощью которого создаётся общество манипулируемых людей, где личности нет места.

«Мы все должны быть одинаковыми, — внушает брандмейстер Монтэгу. — Не свободными и равными от рождения, как сказано в Конституции, а… просто одинаковыми. Пусть все люди станут похожи друг на друга как две капли воды, тогда все будут счастливы, ибо не будет великанов, рядом с которыми другие почувствуют своё ничтожество».

Если принять такую модель общества, то опасность, исходящая от книг, становится самоочевидной: «Книга — это заряженное ружье в доме у соседа. Сжечь её. Разрядить ружье. Надо обуздать человеческий разум. Почём знать, кто завтра станет мишенью для начитанного человека».

До Монтэга доходит смысл предупреждения Битти, но он зашёл уже слишком далеко. Он хранит в доме книги, взятые им из обречённого на сожжение дома. Он признается в этом Милдред и предлагает вместе прочитать и обсудить их, но отклика не находит.

В поисках единомышленников Монтэг выходит на профессора Фабера, давно уже взятого на заметку пожарниками. Отринув первоначальные подозрения, Фабер понимает, что Монтэгу можно доверять. Он делится с ним своими планами по возобновлению книгопечатания, пока пусть в ничтожных дозах. Над Америкой нависла угроза войны — хотя страна уже дважды выходила победительницей в атомных конфликтах, — и Фабер полагает, что после третьего столкновения американцы одумаются и, по необходимости забыв о телевидении, испытают нужду в книгах.

На прощание Фабер даёт Монтэгу миниатюрный приёмник, помещающийся в ухе. Это не только обеспечивает связь между новыми союзниками, но и позволяет Фаберу получать информацию о том, что творится в мире пожарников, изучать его и анализировать сильные и слабые стороны противника.

Военная угроза становится все более реальной, по радио и ТВ сообщают о мобилизации миллионов. Но ещё раньше тучи сгущаются над домом Монтэга. Попытка заинтересовать жену и её подруг книгами оборачивается скандалом. Монтэг возвращается на службу, и команда отправляется на очередной вызов.

К своему удивлению, машина останавливается перед его собственным домом. Битти сообщает ему, что Милдред не вынесла и доложила насчёт книг куда нужно. Впрочем, её донос чуть опоздал: подруги проявили больше расторопности.

По распоряжению Битти Монтэг собственноручно предаёт огню и книги, и дом. Но затем Битти обнаруживает передатчик, которым пользовались для связи Фабер и Монтэг. Чтобы уберечь своего товарища от неприятностей, Монтэг направляет шланг огнемёта на Битти. Затем наступает черёд двух других пожарников.

С этих пор Монтэг становится особо опасным преступником. Организованное общество объявляет ему войну. Впрочем, тогда же начинается и та самая большая война, к которой уже давно готовились. Монтэгу удаётся спастись от погони.

По крайней мере, на какое-то время от него теперь отстанут: дабы убедить общественность, что ни один преступник не уходит от наказания, преследователи умерщвляют ни в чем не повинного прохожего, которого угораздило оказаться на пути страшного Механического Пса. Погоня транслировалась по телевидению, и теперь все добропорядочные граждане могут вздохнуть с облегчением.

Руководствуясь инструкциями Фабера, Монтэг уходит из города и встречается с представителями очень необычного сообщества. Оказывается, в стране давно уже существовало нечто вроде духовной оппозиции.

Видя, как уничтожаются книги, некоторые интеллектуалы нашли способ создания преграды на пути современного варварства. Они стали заучивать наизусть произведения, превращаясь в живые книги. Кто-то затвердил «Государство» Платона, кто-то «Путешествия Гулливера» Свифта, в одном городе «живёт» первая глава «Уолдена» Генри Дэвида Торо, в другом — вторая, и так по всей Америке.

Тысячи единомышленников делают своё дело и ждут, когда их драгоценные знания снова понадобятся обществу. Возможно, они дождутся своего. Страна переживает очередное потрясение, и над городом, который недавно покинул главный герой, возникают неприятельские бомбардировщики. Они сбрасывают на него свой смертоносный груз и превращают в руины это чудо технологической мысли XX столетия.

Читайте также краткое содержание “Все лето в один день” Р. Брэдбери.

Пересказ «451 градус по Фаренгейту» по частям

Р. Брэдбери «451 градус по Фаренгейту» краткое содержание с описанием каждой части:

Часть 1. Очаг и саламандра

«Жечь было наслаждением». Монтэг – пожарный, у него черный шлем с цифрой 451, он сжигает дома и книги. Возвращаясь домой, Монтэг встретил девушку. Мужчина догадался, что это его новая соседка. Девушка рассказала, что ее зовут Кларисса Маклеллан, ей семнадцать лет, и она «помешанная». Она призналась, что любит «смотреть на вещи, вдыхать их запах», бродить всю ночь на пролет до рассвета.

Монтэг рассказал девушке, что работает пожарником уже 10 лет, но не читает книг, которые сжигает, ведь это карается законом. Девушка спросила, правда ли, что раньше пожарники тушили пожары, а не разжигали их. Монтэг рассмеялся и ответил, что это неправда – дома всегда были несгораемыми.

Девушка поделилась, что ей кажется, словно те, кто ездит на ракетных автомобилях, «не знают, что такое трава и цветы», потому что проезжают мимо на слишком большой скорости. Сама же Кларисса очень редко смотрит телевизионные передачи и не ходит в парки развлечений.

Прощаясь Кларисса спросила у Монтэга, счастлив ли он, и убежала. Возвращаясь домой, мужчина думал над ее вопросом: «Конечно, я счастлив. Как же иначе? А она что думает — что я несчастлив?». Мужчина подумал, что лицо девушки похоже на зеркало. «Люди больше похожи <…> на факелы, которые полыхают во всю мочь, пока их не потушат. Но как редко на лице другого человека можно увидеть отражение <…> твоих сокровенных трепетных мыслей!».

Войдя в спальню, напоминавшую «облицованный мраморный склеп», Монтэг подумал, что на самом деле несчастен. Мужчина был женат, его жена Милред спала с наушниками в ушах – миниатюрными «Ракушками» – радиоприемниками-втулками.

Зацепив ногой пустой флакончик из-под снотворного, Монтэг понял, что жена выпила все таблетки. Он позвонил в больницу неотложной помощи. Милред промыли желудок, сделали переливание крови и плазмы. Санитар рассказал, что за последние годы подобные случаи сильно участились.

Утром Милред даже не поняла, что случилось. Женщина всегда ходила с «Ракушками» в ушах, поэтому за десять лет их знакомства научилась читать по губам. Она все дни проводит, смотря телешоу – в гостиной у них установлены три телевизорные стены, и она просит четвертую: «Если бы мы поставили четвёртую стену, эта комната была уже не только наша. В ней жили бы разные необыкновенные, занятые люди». Монтэг отмечает, что, хотя Милред 30 лет, Кларисса кажется ему гораздо старше жены.

У пожарников был механический пес с восемью лапами и высовывающейся стальной иглой с морфием или прокаином. Его обонятельную систему могли настроить на любую жертву. Монтэгу показалось, что пес пытался на него наброситься.

Монтэг и Кларисса виделись ежедневно. Мужчина поделился с девушкой, что у него нет детей, потому что Милред их не хотела. Кларисса не ходила в школу, потому что ученики там никогда не задают вопросов. Она призналась, что боится своих сверстников, которые убивают друг друга – в этом году 6 были застрелены, а 10 погибли в автокатастрофах.

Неожиданно Кларисса исчезла. Монтэг начинает думать о том, что было бы, если бы другие пожарные сожгли его дом и его книги. У него на работе висел список запрещенных книг, а также существовала «краткая история пожарных команд Америки», где было указано, что пожарные жгли книги с 1790 года.

Монтэг едет на очередной вызов – дневной. Его сильно впечатлило, когда хозяйка дома, пожилая женщина, не захотела бросать книги и сгорела вместе с ними. Незаметно для всех Монтэг украл одну книгу.

Ночью Монтэг спросил у жены, помнит ли, когда и где они встретились, но ни он, ни она не помнили. Впрочем, они мало общались – когда бы Монтэг не зашел в гостиную, «стены разговаривали с Милред».

Милред сказала, что семья Клариссы уехала, а сама девушка умерла – попала 4 дня назад под машину. С утра Монтэг понял, что заболел. Он поделился с женой тем, что случилось вчера: должно быть, в книгах было что-то важное, раз пожилая женщина пошла за них на смерть. Однако Милред попросила, чтобы муж оставил ее в покое.

К Монтэгу приехал брандмейстер Битти. Он рассказал, что с 19 века до реальных дней люди все меньше и меньше читали, так как темп жизни постоянно ускорялся. «Жизнь коротка. Что тебе нужно? Прежде всего работа, а после работы развлечения, а их кругом сколько угодно, на каждом шагу, наслаждайтесь».

«Больше фильмов. А пищи для ума всё меньше». «Книга — это заряженное ружьё в доме соседа. Сжечь её!». «Набивайте людям головы цифрами, начиняйте их безобидными фактами, пока их не затошнит, ничего, зато им будет казаться, что они очень образованные».

На прощание Брандмейстер отметил, что в книгах нет ничего такого, «чему стоило бы научить других». Битти сказал, что если пожарный случайно унесет с собой книгу, то ему ничего не будет, если он сожжет ее в течение суток.

Монтэг показал жене, что за вентиляционной решеткой уже год прятал книги. Испуганная Милред хотела их сжечь. Монтэг сказал, что хочет только заглянуть в книги, и если в них действительно ничего нет, то они сожгут их вместе.

Часть 2. Сито и песок

«Весь долгий день они читали». Милред не понравились книги – люди с экранов были для нее более реальными, объемными.

Монтэг вспомнил, как год назад встретил в парке старика Фабера. Тот читал Монтэгу наизусть стихи и написал свой адрес. Монтэг пришел к Фаберу. Он поделился со стариком своей надеждой, что книги помогут стать ему счастливым. Фабер ответил, что этого не будет: «книги — только одно из вместилищ, где мы храним то, что боимся забыть».

Фабер дал Монтэгу подслушивающий аппарат – зеленую втулку, которую сам изобрел.

«В ту ночь даже небо готовилось к войне». Монтэг вернулся домой. К ним пришли две женщины – подруги Милред. Неожиданно Гай выключил экраны и спросил у них о войне. Женщины ответили, что война будет короткой – всего 48 часов, а потом все будет как раньше. Не выдержав того, насколько поверхностно рассуждали обо всем женщины, Монтэг принес книгу и начал читать им стихи. Милред пыталась всех успокоить, но женщины быстро ушли.

Фабер уговорил Монтэга пойти на пожарную станцию на смену. Во время игры в карты Битти смеялся над Монтэгом, цитируя отрывки из произведений, чем сильно взволновал мужчину. Пожарные отправились на вызов. Монтэг всю дорогу был погружен в свои мысли и только когда они приехали, понял, что Битти привез их к дому Гая.

Часть 3. Огонь горит ярко

Из дома выбежала Милред с чемоданом. Монтэг догадался, что это она вызвала пожарных. Гай по приказу Битти сам начал сжигать свой дом. «И, как и прежде, жечь было наслаждением — приятно было дать волю своему гневу».

Битти заметил в ухе Монтэга зеленую пульку – наушник Фабера, и забрал ее. Тогда Гай, не раздумывая, направил дуло огнемета на брандмейстера и сжег его. Остальных пожарных Гай оглушил. Из темноты появился механический пес и прыгнул на Монтэга. Мужчина успел выпустить на него струю пламени. Пес зацепил иглой только ногу Монтэга. Мужчина забрал уцелевшие книги, и хромая пошел прочь. Гай понял, что Битти сам хотел умереть. Монтэг вставил в ухо «Ракушку» – его уже объявили в розыск.

Зайдя в уборную на заправке, Гай услышал, что началась война. Монтэг прячась добрался до дома Фабера. Фабер посоветовал Монтэгу найти лагерь бродяг, среди которых «немало бывших питомцев Гарвардского университета». Монтэг пробежал город, добрался до реки и переплыл ее. Выбравшись на берег, мужчина оказался в лесу.

Ориентируясь по железнодорожным рельсам, Монтэг вышел к поляне, где вокруг костра сидели люди – пять стариков. «Этот огонь ничего не сжигал — он согревал». Гая заметили и позвали к костру. По телевизору они увидели, как полиция вместо Монтэга поймала кого-то другого, так как иначе погоня была бы слишком затянутой и неинтересной зрителям.< Старики у костра представились – среди них были ученые из Кембриджского, Калифорнийского, Колумбийского университета, преподобный отец, писатель.

Мужчины рассказали Монтэгу, что в стране есть люди, которые хранят книги в своей памяти. Они прочитывают книги и после этого сжигают. «Все мы — обрывки и кусочки истории, литературы, международного права». «За двадцать или более лет мы создали нечто вроде организации и наметили план действий». Они надеялись, что после окончания войны книги снова разрешат, и тогда они соберут всех этих людей и по их словам напечатают произведения на бумаге.

«— Смотрите! — воскликнул вдруг Монтэг. В это мгновенье началась и окончилась война». «Спустя несколько секунд грохот далёкого взрыва принёс Монтэгу весть о гибели города». Лежа на земле, Монтэг вспомнил главы из Экклезиаста и Откровения. Один из мужчин отметил, что человек похож на птицу Феникс – «сгорев, она всякий раз снова возрождалась из пепла».

Мужчины отправились вверх по реке на север. Идя впереди, Гай «чувствовал, что и в нём пробуждаются и тихо оживают слова».

«Всему своё время. Время разрушать и время строить. Время молчать и время говорить».

«…И по ту и по другую сторону реки древо жизни, двенадцать раз приносящее плоды, дающее каждый месяц плод свой и листья древа — для исцеления народов».

Заключение

Роман «451 градус по Фаренгейту» Рэя Брэдбери был удостоен в 1954 году премии Американской академии искусств и литературы, а также золотой медали Клуба Содружества Калифорнии. Произведение было дважды экранизировано, по его мотивам были поставлены театральные спектакли, телеспектакль.

Читайте также краткое содержание “Вино из одуванчиков” Р. Брэдбери.

Видео краткое содержание 451 градус по Фаренгейту Брэдбери

Самая известная работа Рэя Брэдбери (1920 — 2012) «451 градуса по Фаренгейту» относится к направлению, указанному как пессимистические будущие идеи в подкатегории «антиутопия». Основной идеей романа Брэдбери, является предостережение от ожидаемых негативных последствий тогда еще такого нового в 1950‑х годах явления как просмотр телевизионных передач.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ieO3M7zRJVA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dpkp2u8Gx58

- Сочинения

- По литературе

- Другие

- Главные герои романа 451 градус по Фаренгейту Брэдбери

В произведении речь идет о людях, проживающих в Америке, в городе будущего, там запрещается читать книги.

Гай Монтэнг

Мужчина среднего возраста, работает пожарным. В его обязанности входит сжигать все книги Он только и делает, что работает и отдыхает, он ни о чем не думает и не мечтает. Живет примитивно. Гай обрел смысл жизни после того, как встретился с неким ученым Фабером.

И в начале произведения Монтэнг убежден, что правильно поступает, но когда встречает героиню Клариссу, то полностью поменял свое решение и начал читать книги. Он начал стремиться к нравственности. Монтэнга предала супруга и после этого он был в розыске и сбежал.

Следующая героиня-тридцатилетняя жена Гая, по имени Милдрэд. Абсолютно пустая женщина, безэмоциональная. Она только смотрит по телевизору телесериалы и разные шоу. Ее мечта-приобрести очередной огромный телевизор. Она совсем не думает о супруге, а заботиться только о себе. А также не желает заводить ребенка. С супругом ни просто живут под одной крышей, у них давно уже нет никаких связей и абсолютно не интересны друг другу.

Кларисса

Следующая героиня являлась соседка супругов, молодая веселая девушка, которая не ходила в школу, так как у нее страхи из-за того, что учащиеся школы могут устроить стрельбу, либо погибнут в авариях. С Гаем они нашли общий язык и беседовали о природе и книгах. Именно она и подоткнула Гая на переосмысление своей жизни. Однажды Кларисса резко пропала, а позже узнается, что она погибла в аварии.

Фабер

Ученый, преклонного возраста, много повидавший в своей жизни, который хранил книги втайне, а также изобрел печатную машинку. Поддерживал людей, которые тайно хранили хоть часть книг, чтобы их не уничтожили. Он также помогал Гаю искать свой верный путь.

Битти

Хитрый, умный и рассудительный человек, являлся начальником Гая. Хотя сам и начитанный, но считает, что книги приносят вред человеку. Погиб от рук Гая, когда тот выпустил языки пламени и из огнемета.

Подруга Милдред

Незамужняя женщина, которая позже вместе с Милдред докладывают на Гая властям о его нарушениях.

В данном произведении весь мир погряз в каком-то безумии, где происходят странности. Здесь всему человечеству независимо от статуса, были запрещены не то, что читать книги, а даже брать их в руки, а тот, кто нарушит или попытается обойти этот закон, то будет наказан. Пожарные здесь сами устраивают пожары, и, в первую очередь, сжигают книги, чтобы те не попали в чьи-нибудь руки и не были прочитаны, вместо того, чтобы спасать людей и здания от огня. В произведении показан мир через сотни лет, где обладают абсурдные идеи и действия, и вообще происходят страшные вещи.

Краткое содержание

Часть 1. Очаг и саламандра

«Жечь было наслаждением». Монтэг – пожарный, у него черный шлем с цифрой 451, он сжигает дома и книги. Возвращаясь домой, Монтэг встретил девушку. Мужчина догадался, что это его новая соседка. Девушка рассказала, что ее зовут Кларисса Маклеллан, ей семнадцать лет, и она «помешанная». Она призналась, что любит «смотреть на вещи, вдыхать их запах», бродить всю ночь на пролет до рассвета.

Монтэг рассказал девушке, что работает пожарником уже 10 лет, но не читает книг, которые сжигает, ведь это карается законом. Девушка спросила, правда ли, что раньше пожарники тушили пожары, а не разжигали их. Монтэг рассмеялся и ответил, что это неправда – дома всегда были несгораемыми.

Девушка поделилась, что ей кажется, словно те, кто ездит на ракетных автомобилях, «не знают, что такое трава и цветы», потому что проезжают мимо на слишком большой скорости. Сама же Кларисса очень редко смотрит телевизионные передачи и не ходит в парки развлечений.

Прощаясь Кларисса спросила у Монтэга, счастлив ли он, и убежала. Возвращаясь домой, мужчина думал над ее вопросом: «Конечно, я счастлив. Как же иначе? А она что думает — что я несчастлив?». Мужчина подумал, что лицо девушки похоже на зеркало. «Люди больше похожи <�…> на факелы, которые полыхают во всю мочь, пока их не потушат. Но как редко на лице другого человека можно увидеть отражение <�…> твоих сокровенных трепетных мыслей!».

Войдя в спальню, напоминавшую «облицованный мраморный склеп», Монтэг подумал, что на самом деле несчастен. Мужчина был женат, его жена Милред спала с наушниками в ушах – миниатюрными «Ракушками» – радиоприемниками-втулками.

Зацепив ногой пустой флакончик из-под снотворного, Монтэг понял, что жена выпила все таблетки. Он позвонил в больницу неотложной помощи. Милред промыли желудок, сделали переливание крови и плазмы. Санитар рассказал, что за последние годы подобные случаи сильно участились.

Утром Милред даже не поняла, что случилось. Женщина всегда ходила с «Ракушками» в ушах, поэтому за десять лет их знакомства научилась читать по губам. Она все дни проводит смотря телешоу – в гостиной у них установлены три телевизорные стены, и она просит четвертую: «Если бы мы поставили четвёртую стену, эта комната была уже не только наша. В ней жили бы разные необыкновенные, занятые люди». Монтэг отмечает, что хотя Милред 30 лет, Кларисса кажется ему гораздо старше жены.

У пожарников был механический пес с восемью лапами и высовывающейся стальной иглой с морфием или прокаином. Его обонятельную систему могли настроить на любую жертву. Монтэгу показалось, что пес пытался на него наброситься.

Монтэг и Кларисса виделись ежедневно. Мужчина поделился с девушкой, что у него нет детей, потому что Милред их не хотела. Кларисса не ходила в школу, потому что ученики там никогда не задают вопросов. Она призналась, что боится своих сверстников, которые убивают друг друга – в этом году 6 были застрелены, а 10 погибли в автокатастрофах.

Неожиданно Кларисса исчезла. Монтэг начинает думать о том, что было бы, если бы другие пожарные сожгли его дом и его книги. У него на работе висел список запрещенных книг, а также существовала «краткая история пожарных команд Америки», где было указано, что пожарные жгли книги с 1790 года.

Монтэг едет на очередной вызов – дневной. Его сильно впечатлило, когда хозяйка дома, пожилая женщина, не захотела бросать книги и сгорела вместе с ними. Незаметно для всех Монтэг украл одну книгу.

Ночью Монтэг спросил у жены, помнит ли, когда и где они встретились, но ни он, ни она не помнили. Впрочем, они мало общались – когда бы Монтэг не зашел в гостиную, «стены разговаривали с Милред».

Милред сказала, что семья Клариссы уехала, а сама девушка умерла – попала 4 дня назад под машину. С утра Монтэг понял, что заболел. Он поделился с женой тем, что случилось вчера: должно быть, в книгах было что-то важное, раз пожилая женщина пошла за них на смерть. Однако Милред попросила, чтобы муж оставил ее в покое.

К Монтэгу приехал брандмейстер Битти. Он рассказал, что с 19 века до реальных дней люди все меньше и меньше читали, так как темп жизни постоянно ускорялся. «Жизнь коротка. Что тебе нужно? Прежде всего работа, а после работы развлечения, а их кругом сколько угодно, на каждом шагу, наслаждайтесь». «Больше фильмов. А пищи для ума всё меньше». «Книга — это заряженное ружьё в доме соседа. Сжечь её!». «Набивайте людям головы цифрами, начиняйте их безобидными фактами, пока их не затошнит, ничего, зато им будет казаться, что они очень образованные».

На прощание Брандмейстер отметил, что в книгах нет ничего такого, «чему стоило бы научить других». Битти сказал, что если пожарный случайно унесет с собой книгу, то ему ничего не будет, если он сожжет ее в течение суток.

Монтэг показал жене, что за вентиляционной решеткой уже год прятал книги. Испуганная Милред хотела их сжечь. Монтэг сказал, что хочет только заглянуть в книги, и если в них действительно ничего нет, то они сожгут их вместе.

Часть 2. Сито и песок

«Весь долгий день они читали». Милред не понравились книги – люди с экранов были для нее более реальными, объемными.

Монтэг вспомнил, как год назад встретил в парке старика Фабера. Тот читал Монтэгу наизусть стихи и написал свой адрес. Монтэг пришел к Фаберу. Он поделился со стариком своей надеждой, что книги помогут стать ему счастливым. Фабер ответил, что этого не будет: «книги — только одно из вместилищ, где мы храним то, что боимся забыть».

Фабер дал Монтэгу подслушивающий аппарат – зеленую втулку, которую сам изобрел.

«В ту ночь даже небо готовилось к войне». Монтэг вернулся домой. К ним пришли две женщины – подруги Милред. Неожиданно Гай выключил экраны и спросил у них о войне. Женщины ответили, что война будет короткой – всего 48 часов, а потом все будет как раньше. Не выдержав того, насколько поверхностно рассуждали обо всем женщины, Монтэг принес книгу и начал читать им стихи. Милред пыталась всех успокоить, но женщины быстро ушли.

Фабер уговорил Монтэга пойти на пожарную станцию на смену. Во время игры в карты Битти смеялся над Монтэгом, цитируя отрывки из произведений, чем сильно взволновал мужчину. Пожарные отправились на вызов. Монтэг всю дорогу был погружен в свои мысли и только когда они приехали, понял, что Битти привез их к дому Гая.

Часть 3. Огонь горит ярко

Из дома выбежала Милред с чемоданом. Монтэг догадался, что это она вызвала пожарных. Гай по приказу Битти сам начал сжигать свой дом. «И, как и прежде, жечь было наслаждением — приятно было дать волю своему гневу».

Битти заметил в ухе Монтэга зеленую пульку – наушник Фабера, и забрал ее. Тогда Гай, не раздумывая, направил дуло огнемета на брандмейстера и сжег его. Остальных пожарных Гай оглушил. Из темноты появился механический пес и прыгнул на Монтэга. Мужчина успел выпустить на него струю пламени. Пес зацепил иглой только ногу Монтэга. Мужчина забрал уцелевшие книги и хромая пошел прочь. Гай понял, что Битти сам хотел умереть. Монтэг вставил в ухо «Ракушку» – его уже объявили в розыск.

Зайдя в уборную на заправке, Гай услышал, что началась война. Монтэг прячась добрался до дома Фабера. Фабер посоветовал Монтэгу найти лагерь бродяг, среди которых «немало бывших питомцев Гарвардского университета». Монтэг пробежал город, добрался до реки и переплыл ее. Выбравшись на берег, мужчина оказался в лесу.

Ориентируясь по железнодорожным рельсам, Монтэг вышел к поляне, где вокруг костра сидели люди – пять стариков. «Этот огонь ничего не сжигал — он согревал». Гая заметили и позвали к костру. По телевизору они увидели, как полиция вместо Монтэга поймала кого-то другого, так как иначе погоня была бы слишком затянутой и неинтересной зрителям.«Все мы — обрывки и кусочки истории, литературы, международного права». «За двадцать или более лет мы создали нечто вроде организации и наметили план действий». Они надеялись, что после окончания войны книги снова разрешат, и тогда они соберут всех этих людей и по их словам напечатают произведения на бумаге.

«— Смотрите! — воскликнул вдруг Монтэг. В это мгновенье началась и окончилась война». «Спустя несколько секунд грохот далёкого взрыва принёс Монтэгу весть о гибели города». Лежа на земле, Монтэг вспомнил главы из Экклезиаста и Откровения. Один из мужчин отметил, что человек похож на птицу Феникс – «сгорев, она всякий раз снова возрождалась из пепла».

Мужчины отправились вверх по реке на север. Идя впереди, Гай «чувствовал, что и в нём пробуждаются и тихо оживают слова».

«Всему своё время. Время разрушать и время строить. Время молчать и время говорить».

«…И по ту и по другую сторону реки древо жизни, двенадцать раз приносящее плоды, дающее каждый месяц плод свой и листья древа — для исцеления народов».

- Гай Монтэг — основной персонаж. Служит пожарным, как его дед и отец до него. Основная обязанность — жечь книги.

- Милдред — супруга Гая. Полностью увязшая в «современном образе жизни». Не работает, не учится, её занимает только «телестена» и сон в наушниках-ракушках.

- Кларисса — 17-я девушка, встреча с которой перевернула жизнь главного героя с ног на голову. Эта героиня любит размышлять, читать, вести беседы — всё то, что давно забыто миром людей.

- Битти — начальник главного героя, шеф пожарной станции «на новый лад».

- Фабер — профессор филологических наук, преподаватель, давно уволенный «за ненадобностью». Состоит в тайной организации группы людей, радеющих за сохранение литературного наследия.

Анализ романа

Структура и сюжет романа основаны на противопоставлениях: свет и тьма, суета и спокойствие.

Искренняя и живая Кларисса противопоставляется сухой, статичной Милдред. У жены главного героя даже лицо с застывшими чертами. Освещённый тёплым светом веранда Клариссы совсем непохожа на холодную спальню Монтега.

- В романе есть символ свечи как домашнего очага, даже лицо Клариссы кажется Монтегу освещённым пламенем свечи. Также свечу упоминает и женщина, которая решила сгореть вместе со своими книгами: Гай решил, что в других обстоятельствах она могла бы быть для него другом.

- Ещё один образ, присутствующий в романе – маска. Люди надевают маски и это считается неотъемлемым признаком агрессивной цивилизации. Гай всегда вежливо улыбается, и эта маска считается символом профессии пожарных.

Название второй главы «песо и сито» намекает на невозможность наполнения жизни смыслом. Когда Монтег в этой главе пытается прочесть в метро библию, он не может разобрать ни слова – все сознание забивает громкая музыка.

В конце книги мы видим, наконец, светлую сторону пламени: это утренние лучи солнца, освещающие вереницу людей. Ведёт просветителей, что символично, Монтег, ещё недавно сжигавший книги.

https://youtu.be/7SqKa0BTn4Q

Герои

- Гай Монтег – главный герой. Работает пожарным. В начале книги он всего лишь винтик в огромной машине государства, но стоит ему познакомиться с Клариссой, и мировоззрение меняется. К моменту завершения книги Гай окончательно становится личностью – а это как раз то, с чем борется государство.

- Кларисса Маклеланд – юная девушка. Простая, в чем-то наивная, воспитана в семье «старого типа». Она любит читать книги и природу, называет себя сумасшедшей. При этом Кларисса легка, беззаботна. Именно ей за несколько мимолётных встреч удаётся пробудить в Монтеге тягу к познаниям. Простой вопрос «Вы счастливы?» заставляет его переосмыслить жизнь. Она погибает под колёсами машины, и это сильно влияет на жизнь главного героя.

- Милдред – жена Гая. Эта героиня олицетворяет в своём лице общество потребления. Она не имеет собственного мнения, обожает телешоу и медиапространство. Милдред всего лишь винтик в механизме, у неё нет настоящих чувств. Все, о чём она мечтает – четвёртая стена с телевиизором. В разговоре с подругами Милдред рассуждает мужей: у кого-то муж умер, и это девушки считают великой благодатью. Милдред целыми днями смотрит телевизор, это единственная её страсть.

- Битти – начальник Монтега и брандмейстер пожарной части. Он начитан и хитер, но все равно разделяет принцип общества потребления. Битти искренне считает, что только в системе человек может быть счастлив. В этом начальник безуспешно пытается убедить Монтега. В итоге он погибает от рук Гая.

- Фабер – старик, бывший профессор. Он придерживается мнения тайного сообщества и мечтает возродить книгопечатание. Именно он внушает Монтегу идею, что третья война сможет вернуть людей к истокам, что они снова начнут читать. При этом Фабер очень боится за свою жизнь.

Часть вторая

Гай Монтэг в 451 градус по фаренгейту понимает, что Милдред не желает идти против системы. Тогда бунтарь вспоминает профессора Фабера. Герои случайно встретились год назад в парке. Тогда Фабер спрятал от своего собеседника книгу. Теперь Монтэг полон надежды найти спасение в его лице.

Поиск единомышленников

По дороге у Гая едва не случается нервный срыв в метро из-за навязчивой рекламы из динамиков и осознания всеобщей зомбированности. Фабер с недоверием относится к неожиданному гостю, но потом понимает, что он из своих.

Открывает отступнику секреты книг и объясняет, почему они не выгодны правительству. Фабер признаётся, что молчал, когда еще что-то можно было исправить.

Поэтому автоматически стал соучастником преступления. Фабер полон страха, но Гай вселяет в него веру. В «451 градус по Фаренгейту» дается описание основных постулатов:

- качество знаний;

- досуг;

- право действовать, руководствуясь предыдущими двумя.

Вместе персонажи «451 градус по Фаренгейту» планируют организовать подпольную печать книг с помощью старого знакомого — бывшего профессора. Кроме того, пожарник хочет организовать диверсию. План заключается в подбрасывании книг по домам коллег (адреса которых имеются у Монтэга), чтобы выявить союзников. Фабер дает Гаю специальный наушник, чтобы давать рекомендации и поддерживать связь. Также через него можно читать ночью книги.

Гай Монтэг возвращается домой и застает несколько подруг жены в гостях. Они ведут разговоры о мужьях, войне, детях. Все это крайне поверхностно и цинично.

Несмотря на многочисленные предупреждения Фабера, Гай раскрывает перед Феллс и Бауэллс наличие книги в доме. Более того он буквально заставляет прослушать их стихотворение, надеясь на понимание и возможное сотрудничество.

Википедия говорит о «451 градус по Фаренгейту», что это было Берег Дувра. Однако произведение не только не находит отклика в сердцах Феллс и Бауэллс, но и приводит их в состояние меланхолии. Описание жизненных проблем и размышление над ними – вот враг «счастливого» человека и причина самоубийств. Милдред постепенно избавляется от улик в доме.

Это интересно! Фонвизин – Недоросль: краткое содержание пьесы по действиям

Интересные факты из истории создания романа Рея Бредбери «451 градус по Фаренгейту»

- Роман был издан лишь после целого года подробнейшей редактуры, в 1953 году.

- Американский писатель набирал свою рукопись на пишущей машинке, арендованной в библиотеке.

- Роман был напечатан в первых выпусках мужского журнала «Плейбой».

- Роман был подвергнут бесконечной критике, но стал произведением, которое принесло автору мировую славу.

- В своей книге Рей Бредбери описал технические новшества, которые стали появляться лишь после издания романа: «Ракушки», изображение 3-д, стены-телевизоры, банкоматы с наличными деньгами.

В романе-антиутопии “451 градус по Фаренгейту” герои живут в американском городе будущего, где запрещены книги и чтение. Описание общественных порядков в городе, где проживают главные герои “451 градус по Фаренгейту” шокирует простого читателя. Имя американского писателя входит в список самых гениальных антиутопистов в мире. В своих книгах Рэй Брэдбери часто поднимает тему будущего человечества, неминуемой деградации из-за потери духовности. Произведение, как это случается с фантастикой, в чём-то предсказало будущее: от технических мелочей до моральной проблемы общества.

Содержание

- Характеристика героев “451 градус по Фаренгейту”

- Главные герои

- Гай Монтэг

- Милдред

- Кларисса Маклеланд

- Фабер

- Битти

- Второстепенные персонажи

- Подруги Милдред

Характеристика героев “451 градус по Фаренгейту”

Главные герои

Гай Монтэг |

Пожарный, мужчина средних лет. Его жизнь ограничена работой и отдыхом, никаких мыслей и мечтаний, новые знания запрещены, они разрушают умы людей. Мир Гая динамичен и примитивен. Как-то он встречает соседку Клариссу, которая переворачивает его мировосприятие одним вопросом: счастлив ли он? На работе нервничают из-за его интереса к пожарным прошлого (которые тушили, а не устраивали пожары). Гай встречается с профессором Фабером, знакомится с литературой, и его жизнь обретает смысл. Преданный женой, он оказывается в розыске, бежит из города. |

Милдред |

Супруга Гая Монтэга, около 30 лет. Человек без мыслей и эмоций, ограниченная, “пустая”. Живёт сериалами и телешоу, практически не достаёт наушники из ушей, из-за чего научилась читать по губам. Мечтает о четвёртом телевизоре в форме стены, чтобы постоянно смотреть его. Она абсолютно чужой человек для Гая, не понимает его, заботится о личном комфорте. У пары нет детей, потому что Милдред не хочет. |

Кларисса Маклеланд |

Соседка семьи Монтэгов, молодая девушка, непохожая на остальных. Не посещает школу (там не задают вопросов), боится беспорядков из-за которых ученики стреляют друг в друга, погибают в автокатастрофах. Девушка никуда не спешит, умеет наслаждаться тишиной и окружающим миром. Они с Гаем часто беседуют о книгах, о природе. Девушка внезапно исчезает. Позже от жены Гай узнаёт, что она погибла в автокатастрофе, и семья переехала. |

Фабер |

Профессор, бывший преподаватель английского языка. Тайно хранит литературу, изобретает книгопечатную технику. Находит в Монтэге однодумца, они работают сообща. Перед началом войны, когда Гая объявляют в розыск, подсказывает, куда идти, чтобы спастись и встретить нужных людей. |

Битти |

Начальник Гая, хитрый и начитанный человек. Несмотря на ум и рассудительность, считает, что книги вредны для людей. Он ближе к обществу потребителей. Выделяться из толпы – опасно, все должны быть равны, в этом состоит благо общества и счастье. Монтэгу приходится направить свой огнемёт на Битти, когда они сжигают дом Гая, так как из-за капитана может пострадать профессор. |

Второстепенные персонажи

Подруги Милдред |

В своей женской компании считают отсутствие мужа (к примеру – смерть) – высшим благом. Находятся у неё в гостях, когда Гай предлагает им почитать книги и рассказывает о своих взглядах. Шокированные женщины, быстро покидают дом. Спустя какое-то время они или Милдред докладывают о нарушениях мужа властям. |

Предыдущая

СочиненияГлавные герои «Темные аллеи» характеристика персонажей рассказа Бунина с описанием

Следующая

СочиненияГлавные герои «Сотников» характеристика персонажей повести Быкова списком

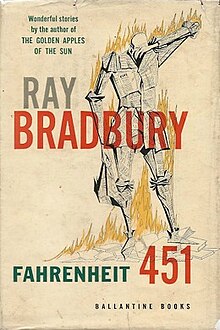

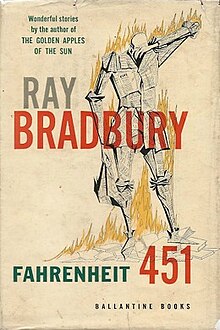

First edition cover (clothbound) |

|

| Author | Ray Bradbury |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joseph Mugnaini[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian[2] |

| Published | October 19, 1953 (Ballantine Books)[3] |

| Pages | 256 |

| ISBN | 978-0-7432-4722-1 (current cover edition) |

| OCLC | 53101079 |

|

Dewey Decimal |

813.54 22 |

| LC Class | PS3503.R167 F3 2003 |

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by American writer Ray Bradbury. Often regarded as one of his best works,[4] Fahrenheit 451 presents an American society where books have been personified and outlawed and «firemen» burn any that are found.[5] The novel follows Guy Montag, a fireman who becomes disillusioned with his role of censoring literature and destroying knowledge, eventually quitting his job and committing himself to the preservation of literary and cultural writings.

Fahrenheit 451 was written by Bradbury during the Second Red Scare and the McCarthy era, who was inspired by the book burnings in Nazi Germany and by ideological repression in the Soviet Union.[6] Bradbury’s claimed motivation for writing the novel has changed multiple times. In a 1956 radio interview, Bradbury said that he wrote the book because of his concerns about the threat of burning books in the United States.[7] In later years, he described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.[8] In a 1994 interview, Bradbury cited political correctness as an allegory for the censorship in the book, calling it «the real enemy these days … black groups want to control our thinking and you can’t say certain things. The homosexual groups don’t want you to criticize them. It’s thought control and

freedom of speech control.»[9]

The writing and theme within Fahrenheit 451 was explored by Bradbury in some of his previous short stories. Between 1947 and 1948, Bradbury wrote «Bright Phoenix», a short story about a librarian who confronts a «Chief Censor», who burns books. An encounter Bradbury had in 1949 with the police inspired him to write the short story «The Pedestrian» in 1951. In «The Pedestrian», a man going for a nighttime walk in his neighborhood is harassed and detained by the police. In the society of «The Pedestrian», citizens are expected to watch television as a leisurely activity, a detail that would be included in Fahrenheit 451. Elements of both «Bright Phoenix» and «The Pedestrian» would be combined into The Fireman, a novella published in 1951. Bradbury was urged by Stanley Kauffmann, a publisher at Ballantine Books, to make The Fireman into a full novel. Bradbury finished the manuscript for Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, and the novel was published later that year.

Upon its release, Fahrenheit 451 was a critical success, although polarized some critics. The novel’s subject matter led to its censorship in apartheid South Africa and various schools in the United States. In 1954, Fahrenheit 451 won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal.[10][11][12] It later won the Prometheus «Hall of Fame» Award in 1984[13] and a «Retro» Hugo Award in 2004.[14] Bradbury was honored with a Spoken Word Grammy nomination for his 1976 audiobook version.[15] The novel has also been adapted into films, stage plays, and video games. Film adaptations of the novel include a 1966 film directed by François Truffaut starring Oskar Werner as Guy Montag, an adaptation that was met with mixed critical reception, and a 2018 television film directed by Ramin Bahrani starring Michael B. Jordan as Montag that also received a mixed critical reception. Bradbury himself published a stage play version in 1979 and helped develop a 1984 interactive fiction video game of the same name, as well as a collection of his short stories titled A Pleasure to Burn.[16] Two BBC Radio dramatizations were also produced.

Historical and biographical context[edit]

Shortly after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the conclusion of World War II, the United States focused its concern on the Soviet atomic bomb project and the expansion of communism. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), formed in 1938 to investigate American citizens and organizations suspected of having communist ties, held hearings in 1947 to investigate alleged communist influence in Hollywood movie-making. These hearings resulted in the blacklisting of the so-called «Hollywood Ten»,[17] a group of influential screenwriters and directors.

The year HUAC began investigating Hollywood is often considered the beginning of the Cold War, as in March 1947, the Truman Doctrine was announced. By about 1950, the Cold War was in full swing, and the American public’s fear of nuclear warfare and communist influence was at a feverish level. The stage was set for Bradbury to write the dramatic nuclear holocaust ending of Fahrenheit 451, exemplifying the type of scenario feared by many Americans of the time.[18]

The government’s interference in the affairs of artists and creative types infuriated Bradbury;[19] Bradbury was bitter and concerned about the workings of his government, and a late 1949 nighttime encounter with an overzealous police officer would inspire Bradbury to write «The Pedestrian», a short story which would go on to become «The Fireman» and then Fahrenheit 451. The rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s hearings hostile to accused communists, beginning in 1950, deepened Bradbury’s contempt for government overreach.[20][21]

The Golden Age of Radio occurred between the early 1920s to the late 1950s, during Bradbury’s early life, while the transition to the Golden Age of Television began right around the time he started to work on the stories that would eventually lead to Fahrenheit 451. Bradbury saw these forms of media as a threat to the reading of books, indeed as a threat to society, as he believed they could act as a distraction from important affairs. This contempt for mass media and technology would express itself through Mildred and her friends and is an important theme in the book.[22]

Bradbury’s lifelong passion for books began at an early age. After he graduated from high school, his family could not afford for him to attend college, so Bradbury began spending time at the Los Angeles Public Library where he educated himself.[23] As a frequent visitor to his local libraries in the 1920s and 1930s, he recalls being disappointed because they did not stock popular science fiction novels, like those of H. G. Wells, because, at the time, they were not deemed literary enough. Between this and learning about the destruction of the Library of Alexandria,[24] a great impression was made on Bradbury about the vulnerability of books to censure and destruction. Later, as a teenager, Bradbury was horrified by the Nazi book burnings[25] and later by Joseph Stalin’s campaign of political repression, the «Great Purge», in which writers and poets, among many others, were arrested and often executed.[6]

Plot summary[edit]

Fahrenheit 451 is set in an unspecified city in the year 2049 (according to Ray Bradbury’s Coda), though it is written as if set in a distant future.[note 1][26] The earliest editions make clear that it takes place no earlier than the year 1960.[note 2][27]

The novel is divided into three parts: «The Hearth and the Salamander,» «The Sieve and the Sand,» and «Burning Bright.»

«The Hearth and the Salamander»[edit]

Guy Montag is a fireman employed to burn outlawed books, along with the houses they are hidden in. He is married but has no children. One fall night while returning from work, he meets his new neighbor, a teenage girl named Clarisse McClellan, whose free-thinking ideals and liberating spirit cause him to question his life and his own perceived happiness. Montag returns home to find that his wife Mildred has overdosed on sleeping pills, and he calls for medical attention. Two uncaring EMTs pump Mildred’s stomach, drain her poisoned blood, and fill her with new blood. After the EMTs leave to rescue another overdose victim, Montag goes outside and overhears Clarisse and her family talking about the way life is in this hedonistic, illiterate society. Montag’s mind is bombarded with Clarisse’s subversive thoughts and the memory of his wife’s near-death. Over the next few days, Clarisse faithfully meets Montag each night as he walks home. She tells him about how her simple pleasures and interests make her an outcast among her peers and how she is forced to go to therapy for her behavior and thoughts. Montag looks forward to these meetings, and just as he begins to expect them, Clarisse goes missing. He senses something is wrong.[28]

In the following days, while at work with the other firemen ransacking the book-filled house of an old woman and drenching it in kerosene before the inevitable burning, Montag steals a book before any of his coworkers notice. The woman refuses to leave her house and her books, choosing instead to light a match and burn herself alive. Jarred by the woman’s suicide, Montag returns home and hides the stolen book under his pillow. Later, Montag wakes Mildred from her sleep and asks her if she has seen or heard anything about Clarisse McClellan. She reveals that Clarisse’s family moved away after Clarisse was hit by a speeding car and died four days ago. Dismayed by her failure to mention this earlier, Montag uneasily tries to fall asleep. Outside he suspects the presence of «The Mechanical Hound», an eight-legged[29] robotic dog-like creature that resides in the firehouse and aids the firemen in hunting book hoarders.

Montag awakens ill the next morning. Mildred tries to care for her husband but finds herself more involved in the «parlor wall» entertainment in the living room – large televisions filling the walls. Montag suggests that maybe he should take a break from being a fireman after what happened last night, and Mildred panics over the thought of losing the house and her parlor wall «family.» Captain Beatty, Montag’s fire chief, personally visits Montag to see how he is doing. Sensing his concerns, Beatty recounts the history of how books lost their value and how the firemen were adapted for their current role: over the course of several decades, people began to embrace new media (in this case, film and television), sports, and an ever-quickening pace of life. Books were ruthlessly abridged or degraded to accommodate short attention spans. At the same time, advances in technology resulted in nearly all buildings being made out of fireproof materials, and the traditional role of firemen in preventing fires was no longer necessary. The government instead turned the firemen into officers of society’s peace of mind: instead of putting out fires, they became responsible for starting them, specifically for the purpose of burning books, which were condemned as sources of confusing and depressing thoughts that only complicated people’s lives. After an awkward exchange between Mildred and Montag over the book hidden under Montag’s pillow, Beatty becomes suspicious and casually adds a passing threat as he leaves, telling Montag that if a fireman had a book, he would be asked to burn it within the following twenty-four hours. If he refused, the other firemen would come and burn it for him. The encounter leaves Montag shaken.

After Beatty leaves, Montag reveals to Mildred that, over the last year, he has accumulated a stash of books that he has kept hidden in the air-conditioning duct in their ceiling. In a panic, Mildred grabs a book and rushes to throw it in the kitchen incinerator. Montag subdues her and tells her that the two of them are going to read the books to see if they have value. If they do not, he promises the books will be burned and all will return to normal.

«The Sieve and the Sand»[edit]

Montag and Mildred discuss the stolen books, and Mildred refuses to go along with it, questioning why she or anyone else should care about books. Montag goes on a rant about Mildred’s suicide attempt, Clarisse’s disappearance and death, the old woman who burned herself, and the imminent threat of war that goes ignored by the masses. He suggests that perhaps the books of the past have messages that can save society from its own destruction. The conversation is interrupted by a call from Mildred’s friend, Mrs. Bowles, and they set up a date to watch the «parlor walls» that night at Mildred’s house.

Montag concedes that Mildred is a lost cause and he will need help to understand the books. He remembers an old man named Faber, an English professor before books were banned, whom he once met in a park. Montag makes a subway trip to Faber’s home along with a rare copy of the Bible, the book he stole at the woman’s house. Once there, Montag forces the scared and reluctant Faber into helping him by methodically ripping pages from the Bible. Faber concedes and gives Montag a homemade earpiece communicator so that he can offer constant guidance.

At home, Mildred’s friends, Mrs. Bowles and Mrs. Phelps arrive to watch the «parlor walls.» Not interested in this insipid entertainment, Montag turns off the walls and tries to engage the women in meaningful conversation, only for them to reveal just how indifferent, ignorant, and callous they truly are. Enraged by their idiocy, Montag leaves momentarily and returns with a book of poetry. This confuses the women and alarms Faber, who is listening remotely. Mildred tries to dismiss Montag’s actions as a tradition firemen act out once a year: they find an old book and read it as a way to make fun of how silly the past is. Montag proceeds to recite the poem Dover Beach, causing Mrs. Phelps to cry. At the behest of Faber in the earpiece, Montag burns the book. Mildred’s friends leave in disgust, while Mildred locks herself in the bathroom and attempts to kill herself again by overdosing on sleeping pills.