Все главные и второстепенные герои «Путешествий Гулливера» Джонатана Свифта олицетворяют собой те или иные черты человеческого общества. Глазами самого Лемюэля Гулливера, судового врача, автор раскрывает читателям глаза на пороки человеческого общества, беспощадно их высмеивая. В этой книге досталось всем – и политическим партиям XVIII века, и религиозным распрям, хотя в целом «Путешествие Гулливера» не только обличает пороки, но и учит доброте, мудрости и уважению.

Главные герои «Путешествий Гулливера»

Лемюэль Гулливер

Судовый врач, хирург, которого судьба постоянно кидает то туда, то сюда. Именно он является главным героем «Путешествий Гулливера» Джонатана Свифта, и через его глаза автор даёт читателям возможность смотреть на мир таким, каким его видит этот персонаж. Лемюэль Гулливер – человек добрый и честный, его до глубины души возмущает любая несправедливость. Однако, чем больше он узнает о людях, тем больше разочаровывается в человечестве, проявляя черты настоящего мизантропа.

Король Лилипутии

Высокомерный император ростом около шести дюймов (порядка 15 см), которого его подданные почтительно называют «отрадой и ужасом Вселенной». Обладает чрезмерно раздутым самомнением, и, как и почти все жители Лилипутии, является карикатурой на чванливое человеческое общество. Сперва принимает от Гулливера клятву вассальной верности, но потом решает ослепить его и убить. Как и большинство других героев «Путешествий Гулливера», является отрицательным персонажем, которому дать положительную характеристику нельзя при всём желании.

Флимнап

Лорд-канцлер казначейства Лилипутии, злобный и завистливый человечек, который ненавидит Гулливера и плетёт против него интриги. На суде именно он выступает против него, ярко демонстрируя свою отталкивающую натуру. Является смертельным врагом главного героя, хотя тот не причинил ему никакого зла.

Рельдресель

Ещё один государственный деятель Лилипутии, секретарь по тайным делам. Однако, в отличие от большинства своих соотечественников, является честным человеком, и вообще в целом неплохим. Подружившись с Гулливером, именно он позднее предупреждает его о том, что император намеревается его убить, и тем самым спасает ему жизнь. По задумке Джонатана Свифта Рельдресель олицетворяет надежду на то, что даже в насквозь порочном обществе можно найти достойного человека.

Король великанов

Один из немногих положительных главных героев «Путешествий Гулливера», благородный и честный правитель своей страны. Выше среднего человека в 12 раз, как и все остальные великаны. Старается мудро руководить своей страной, делает всё возможное для мирного развития и старается избежать войн. Услышав от Гулливера предложение об использовании неизвестного великанам пороха в военных целях, король приходит в ужас, и под страхом смерти запрещает даже упоминать об этом «дьявольском изобретении». Устами короля великанов Джонатан Свифт озвучивает главную мысль, в которую верит сам – любой человек, который сумеет вырастить на том же поле два колоска вместо одного, сделает для мира больше добра, чем все политики, вместе взятые. Во время бесед с главным героем король обсуждает политику стран Европы, насмешливо её критикуя, причём открыто, а не аллегорически, как в случае с обитателями Лилипутии.

Глюмдальклич

Добрая дочь великана-фермера, который становится первым владельцем Гулливера в стране великанов. Фермер считает его забавной диковинкой и показывает за деньги, беспощадно эксплуатируя его на потеху публике, и только Глюмдальклич относится к нему бережно и заботливо. Она – положительный герой «Путешествий Гулливера», в отличие от её отца и других великанов, которых забавляют кривляния маленького человечка, являющегося в их глазах чем-то вроде забавной дрессированной зверушки.

Лорд Мьюноди

Образец здравомыслия. Проживает в королевстве Бальнибарби, которое находится в состоянии разрухи из-за того, что правительство поддерживает нереалистичные проекты неких «прожектёров», которые отнимают все силы и не приводят ни к каким положительным результатам. Сановник Мьюноди, однако, придерживается старых принципов ведения сельского хозяйства, а потому его имение процветает в то время, как вся страна лежит в руинах. Мьюноди олицетворяет собой здравомыслие в обществе, в котором некомпетентность и порочность власти является причиной коллапса общества и бедствий основной массы населения. Из-за своей позиции и несогласия с властями Мьюноди подвергается нападкам «прожектёров» и представителей власти.

Струльдбруги

Раса бессмертных, которые, однако, при всей своей невозможности умереть страдают от старости, немощности и многочисленных болезней. Они несчастны, и всё, чего они хотят – это возможности умереть. Струльдбруги в целом являются скорее не главными героями «Путешествий Гулливера», а жертвами. Через их трагедию Джонатан Свифт показывает своё отрицательное отношение к техническому прогрессу, которое, по его мнению, не принесёт людям ничего хорошего.

Гуигнгнмы

Разумные лошади, воплощение практически всех добродетелей, какие только есть в мире. Наряду с королём великанов гуигнгнмов можно назвать самыми благородными героями «Путешествий Гулливера». Соседствуют с расой людей, еху, которые являются их полной противоположностью, а потому находятся на положении рабов. Сам Гулливер тоже принимается ими за еху, но ввиду его личных качестве гуигнгнмы относятся к нему не как к рабу, а скорее как к почётному пленнику.

Еху

Мерзкие и отвратительные создания. Являются людьми, олицетворяют все пороки человечества сразу – жадность, подлость, злобу и так далее. Находятся на положении рабов у мудрых и добрых гуигнгнмов. У Гулливера еху не вызывают ничего, кроме отвращения, в то время как гуигнгнмов он описывает восторженно, и невероятно печалится, когда его изгоняют. После возвращения в Англию он начинает испытывать непреодолимое отвращение ко всем людям (то есть еху), за редким исключением.

Педро де Мендес

Капитан корабля, португалец по происхождению, который волей случая знакомится с Гулливером. Также относится к положительным главным героям «Путешествий Гулливера» Джонатана Свифта – он опечален тем, что Гулливер стал ненавидеть человечество, в котором он больше не видит ничего хорошего. Педро де Мендес, человек добрый и отзывчивый, пытается переубедить его, чтобы избавить от этой ненависти к людям, но практически не достигает успеха.

«Путешествия Гулливера» читательский дневник

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 387.

Обновлено 4 Августа, 2021

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 387.

Обновлено 4 Августа, 2021

«Путешествия Гулливера» – история об увлекательных приключениях судового врача Гулливера, которому удалось побывать в странах с самыми удивительными существами.

Краткое содержание «Путешествия Гулливера» для читательского дневника

ФИО автора: Джонатан Свифт

Название: Путешествия Гулливера

Число страниц: 560. Джонатан Свифт. «Все путешествия Гулливера». Издательство «ЭКСМО». 2016 год

Жанр: Роман

Год написания: 1726 год

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 36 лет.

Главные герои

Лемюэль Гулливер – судовой врач, путешественник, которому удалось побывать в самых удивительных странах.

Обратите внимание, ещё у нас есть:

Сюжет

После кораблекрушения в сильный шторм судовой врач Лемюэль Гулливер оказался на земле, населённой лилипутами. Несмотря на свое превосходство в росте, он оказался пленником крошечных жителей. Чтобы получить некоторую свободу, Гулливер был вынужден дать клятву верности Императору Лилипутов. Герой помог правителю выиграть морской бой и тем самым решить исход давней войны между соседними государствами. Осознав, насколько мощным орудием может стать Гулливер, император приказал ему захватить оставшиеся корабли неприятеля, но великан отказался. За неповиновение Император Лилипутов приказал ослепить Гулливера, но тот успел скрыться.

Далее судовой врач оказался в стране, населённой великанами. Из-за своих крошечных размеров Гулливер выступил в роли диковинной зверюшки, которую можно показывать за деньги. Узнав о существовании Гулливера, его выкупила королева, которая постаралась сделать жизнь крошечного человечка более-менее сносной. Однако Гулливер стал объектом неприкрытой зависти и злобы придворного карлика, который видел в нём опасного соперника. Гулливеру довелось пережить немало неприятных минут, когда он оказался во власти обезьяны. Покинуть страну великанов ему удалось благодаря случаю – орёл схватил его домик и выбросил в открытое море, где путешественника подобрал британский корабль.

Следующей страной, в которой удалось побывать Гулливеру, оказалось королевство, населённое рассеянными академиками. Они были настолько увлечены наукой, что не обращали никакого внимания на окружающую действительность. Их беда заключалась в том, что все их научные открытия никогда не воплощались в жизнь, и страна находилась в глубоком упадке.

Гулливер, набрав собственную команду, отправился в очередное плавание. Однако новый экипаж сплошь состоял из преступников, которые бросили капитана на одиноком острове. Вскоре Гулливер выяснил, что его населяли разумные лошади – умные и благородные создания, по сравнению с которыми человек выглядел как дикое животное. В итоге Гулливера изгнали с острова, и он вернулся на родину.

План пересказа

- Кораблекрушение.

- Страна лилипутов.

- Гулливер помогает императору одолеть противника.

- Неповиновение и побег.

- Страна великанов.

- Добрая королева.

- Карлик и обезьяна.

- Путешествие с орлом.

- Королевство академиков.

- Причины упадка королевства.

- Новый экипаж.

- Благородные лошади.

- Возвращение на родину.

Главная мысль

Находчивый, умный, думающий человек не пропадёт ни при каких обстоятельствах.

Чему учит

Произведение учит быть честным, справедливым, добрым. Учит не бояться трудностей и никогда не сдаваться, защищать слабых и помогать тем, кто нуждается в помощи.

Отзыв

Испытания, выпавшие на долю Гулливера, способны сломить кого угодно. Однако главный герой доказал, что является очень умным, находчивым и смелым человеком, который в трудной ситуации не намерен сидеть сложа руки.

Пословицы

- Не на внешность смотри, по делам суди.

- Не смотри, что небольшой, зато с головой.

- Завистливый по чужому счастью сохнет.

- Всё хорошо, что хорошо кончается.

Что понравилось

Понравилось, что Гулливер, куда бы его ни забрасывала судьба, не вешал нос и неизменно находил выход даже из самых сложных и запутанных ситуаций.

Тест по роману

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Екатерина Николова

13/13

-

Лев Воронов

13/13

-

Никита Мешков

13/13

-

Евгений Коржиков

8/13

-

Динар Керженов

8/13

-

Лия Ким

12/13

-

Жанна Андреева

12/13

-

Анастасия Жульцова

12/13

-

Алина Шабунина

13/13

-

Александр Лис

13/13

Рейтинг читательского дневника

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 387.

А какую оценку поставите вы?

На чтение 26 мин Просмотров 12.7к. Опубликовано 07.06.2022

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ «Путешествия Гулливера» за 1 минуту и подробно по главам за 24 минуты.

Очень краткий пересказ романа «Путешествия Гулливера»

Лемюэль Гулливер описывает четыре путешествия, совершенные им в течение шестнадцати лет.

Сначала Гулливер побывал на острове лилипутов — крохотных человечков. Он помог им одержать победу над соседней державой, но впал в немилость короля и был вынужден вернуться на родину.

Затем путешественник попал в страну великанов и сам ощутил себя лилипутом. Долгое время Лемюэль прожил при королевском дворе, пока гигантская птица не унесла его в ящике в море.

В ходе третьего путешествия Гулливер посетил несколько стран, где увидел немало диковинок: летающий остров; полоумных ученых, занимающихся бесполезными проектами; волшебника, способного вызывать духов мертвецов; бессмертных людей.

Последнее путешествие Лемюэль совершил в страну гуигнгнмов — обладающих разумом коней. Там он увидел йеху — человекообразных мерзких существ и проникся презрением ко всему человеческому роду. Гулливер хотел навсегда остаться жить у добродетельных гуигнгнмов, но те вежливо попросили его покинуть их земли.

Главный герой и его характеристика:

- Лемюэль Гулливер — английский врач, испытывающий тягу к морским путешествиям. Лемюэль долгие годы проводит вдали от родины, переживает множество приключений и пишет подробный отчет о своих похождениях.

Второстепенные герои и их характеристика:

- Ричард Симпсон — издатель рукописи о путешествиях Гулливера.

- Бетс — лондонский хирург, учитель Гулливера.

- Лилипуты — крохотные люди, в страну которых Гулливер попал во время первого путешествия.

- Император Лилипутии — повелитель маленьких человечков (лилипутов), в образе которого автор высмеивает пороки европейских монархов (захватническая политика, страсть к военным парадам, вероломство и др.).

- Флимнап — лорд-канцлер Лилипутии, устроивший заговор против Гулливера.

- Скайреш Болголам — адмирал в Лилипутии, поддержавший заговор Флимнапа.

- Рельдресель — секретарь по тайным делам в Лилипутии.

- Великаны — жители Бробдингнега.

- Фермер-великан — житель Бробдингнега, который нашел Гулливера и повез его по стране, устраивая представления.

- Глюмдальклич — дочка фермера-великана, ставшая для Гулливера «нянюшкой».

- Король и королева Бробдингнега — повелители в стране великанов, проявившие большую заботу по отношению к Гулливеру.

- Лапутяне — жители летающего острова Лапута.

- Король Лапуты — повелитель летающего острова.

- Мьюноди — сановник в королевстве Бальнибарби; противник «прогрессивных» проектов.

- Король Лаггнегга — повелитель королевства Лаггнегг.

- Струльдбруги — бессмертные люди в королевстве Лаггнегг.

- Гуигнгнмы — обладающие разумом кони.

- Йеху — человекоподобные скоты в стране гуигнгнмов.

- Серый конь в яблоках — гуигнгнм, приютивший у себя Гулливера.

- Педро де Мендес — капитан португальского судна, нашедший Гулливера на побережье Австралии и оказавший ему помощь в возвращении на родину.

Краткое содержание романа «Путешествия Гулливера» подробно по главам

Издатель к читателю

Ричард Симпсон сообщает читателям, что автором публикуемой рукописи является его друг и дальний родственник — Лемюэль Гулливер, описавший свои невероятные путешествия. Гулливер — очень честный и правдивый человек. Нет никаких сомнений в том, что все описанное им — чистая правда.

Симпсон замечает, что позволил себе сократить рукопись наполовину, изъяв из нее подробные технические описания (показания компаса, направление ветров и течений, координаты широты и долготы и т. п.). Все желающие могут обратиться к нему и прочесть оригинал.

Письмо капитана Гулливера к своему родственнику Ричарду Симпсону

Гулливер упрекает Симпсона в многочисленных искажениях своей рукописи, допущенных в печатном издании. Он указывает на пропуски, ошибки и вставки и просит опубликовать исправленный вариант.

Часть первая. Путешествие в Лилипутию

Глава I

В юности Гулливер три года проучился в университете, но из-за недостатка средств был вынужден бросить учебу и поступить в ученики к лондонскому хирургу Бетсу. Затем около двух лет он изучал медицину в Лейдене.

Гулливер женился, поселился в Лондоне и занялся частной практикой. После смерти Бетса его дела сильно пошатнулись. Лемюэль решил поправить материальное положение, нанявшись хирургом на какое-нибудь судно. Он провел несколько лет в продолжительных морских путешествиях.

В 1699 г. Гулливер отправился в очередное плавание на корабле «Антилопа». Судно потерпело кораблекрушение. Из всей команды уцелел лишь один Лемюэль. Он кое-как добрался до земли и в изнеможении уснул.

Проснувшись, Гулливер обнаружил, что не может пошевелиться. Все его тело было опутано веревками, привязанными к вбитым в землю колышкам.

Путешественник увидел, что по нему ходят маленькие человечки ростом около десяти сантиметров. Он стал яростно дергаться и сумел освободить одну руку. Тут же на пленника посыпалось множество крошечных стрел. Одежду они пробить не могли, но поранили лицо.

Гулливер покорился и перестал вырываться. Рядом с ним был возведен большой помост, на который взобрался человек знатного происхождения. Он обратился к пленнику с речью на незнакомом языке. Лемюэль ничего не понял. Он показал знаками, что хочет есть.

К Гулливеру поднесли множество мелких жареных туш и две бочки вина. Утолив голод и жажду, он вновь заснул. Позже Лемюэль узнал, что в вино было подмешано снотворное.

Пока Гулливер спал, лилипуты погрузили его на большую повозку и перевезли поближе к городу. Там его приковали на цепь в просторном здании пустующего храма.

Глава II

На следующий день посмотреть на великана приехал император Лилипутии и члены его семьи. Прямо на их глазах Гулливер съел несколько повозок доставленной ему провизии. Император попробовал поговорить с пленником, но оба не поняли друг друга.

Лилипутские мастера сшили гигантское постельное белье и приступили к изготовлению одежды для «Человека-Горы» (так можно перевести слово, которым Гулливера называли в Лилипутии).

По приказу императора Лемюэля начали обучать лилипутскому языку. Очень скоро он уже мог поддерживать несложный разговор.

Император попросил Гулливера показать содержимое своих карманов и сдать вещи, которые могут представлять опасность. Лемюэль отдал шпагу, пистолеты, пули и порох.

Глава III

Гулливер вел себя очень смирно и постоянно просил императора даровать ему свободу. Лилипуты перестали бояться великана и даже пускали детей поиграть на его громадном теле в прятки.

Однажды император показал Гулливеру главное лилипутское развлечение. Кандидаты на высшие государственные должности должны были, стоя на канате, прыгнуть как можно выше. Назначение на должность получал самый лучший прыгун.

Гулливер, в свою очередь, тоже сделал императору приятный сюрприз. Он смастерил из жердей и своего носового платка высокую площадку, на которой лилипутские всадники могли проводить военные учения и парады.

Доверие императора к пленнику росло день ото дня. Наконец, он собрал государственный совет по вопросу об освобождении «Человека- Горы». На совете было установлено несколько условий. Гулливер должен соблюдать крайнюю осторожность, прогуливаясь по острову. Ему запрещалось без разрешения посещать столицу. Великан должен помочь императору в войне против острова Блефуску.

Когда Гулливер в торжественной обстановке подписал условия и поклялся их соблюдать, с него сняли цепь.

Глава IV

Получив свободу, Лемюэль первым делом попросил разрешения осмотреть столицу лилипутов — Мильдендо. Очень осторожно он прошел по маленькому городу, отметив красоту императорского дворца, прочность крепостных стен и достаток жителей столицы.

Гулливер прожил в Лилипутии уже около девяти месяцев. Однажды к нему приехал главный секретарь по тайным делам Рельдресель. Он по секрету рассказал, что стране угрожают две серьезные опасности.

За власть в Лилипутии уже много лет ведут борьбу две политические партии: сторонники высоких и низких каблуков (Тремексены и Слемексены). Нынешний император поддерживает Тремексенов. Есть основания полагать, что наследник благоволит к представителям враждебной партии.

Политическая борьба ослабляет Лилипутию. Между тем ей грозит вторжение флота острова Блефуску. Две державы уже давно находятся в состоянии войны. Причиной конфликта стал вопрос о том, с какой стороны нужно разбивать яйцо. В Лилипутии императорским указом постановлено делать это с острого конца. «Тупоконечники» бежали в Блефуску и нашли там поддержку. Это и стало основанием для многолетней войны.

Рельдресель добавил, что сообщил Гулливеру сведения государственной важности по личному указанию императора.

Глава V

Гулливер придумал хитроумный способ одержать победу над Блефуску. С помощью лилипутских мастеров он изготовил прочные канаты, к концам которых привязал стальные крючки.

Переплыв пролив между островами, Лемюэль отрезал ножом якоря у неприятельских кораблей и зацепил за них крючки. Осыпаемый тучей стрел, «Человек-Гора» утащил за собой весь вражеский флот.

За этот подвиг Гулливер получил титул нардака — наивысший в Лилипутии. Воодушевленный победой император хотел окончательно покорить Блефуску и присоединить остров к своим владениям. Гулливер отказался участвовать в этом и предлагал заключить мир. Под давлением здравомыслящих министров император был вынужден согласиться. Этот инцидент стал началом роста неприязни к великану.

Императору также не понравилось, что Гулливер общался с послами Блефуску и изъявил желание посетить их остров.

Глава VI

Гулливер многое узнал об образе жизни, нравах и обычаях жителей острова.

В Лилипутии смертной казнью карались доносчики и мошенники. Соблюдающим законы людям оказывалось поощрение.

Детей из семей дворян, купцов и ремесленников в раннем возрасте забирали у родителей и помещали в специальные заведения, где в них воспитывались самые лучшие качества: любовь к отечеству, справедливость, честность и т. д. Представители средних сословий обучались практическим наукам и ремеслам.

Воспитательные заведения делились на мужские и женские. Дети рабочих и крестьян никакого образования не получали.

Лилипутские портные и швеи изготовили для Гулливера одежду. К его услугам было триста поваров.

У «Человека-Горы» уже давно появился недруг — лорд-канцлер казначейства Флимнап. Он настраивал императора против Гулливера, указывая, в частности, на огромные расходы, связанные с его содержанием.

Глава VII

Однажды к Гулливеру тайно приехал один знатный человек, который рассказал, что ему грозит опасность. Флимнап, адмирал Болголам и еще несколько вельмож добились проведения нескольких секретных совещаний. На них Человеку-Горе было вынесено обвинение в государственной измене.

Было решено ослепить Гулливера, а затем заморить его голодом. Официальное обвинение будет предъявлено Лемюэлю через три дня.

Не дожидаясь предъявления обвинения, Гулливер отправился на Блефуску и был радушно встречен императором и всеми жителями острова.

Глава VIII

На третий день проживания на Блефуску Гулливер заметил недалеко от берега перевернутую лодку. С помощью флота блефускианцев он вытащил ее на сушу и занялся ремонтом.

Спустя месяц лодка была готова для плавания. Гулливер простился с жителями Блефуску и покинул остров. На второй день его подобрал английский корабль.

Невероятному рассказу Гулливера о лилипутах поверили лишь тогда, когда он показал взятых с собой крохотных коров и овец.

Лемюэль благополучно добрался до Англии, но прожил с семьей лишь два месяца. Гулливера вновь потянуло к путешествиям. Летом 1702 г. на корабле «Адвенчер» он отправился в Индию.

Часть вторая. Путешествие в Бробдингнег

Глава I

Обогнув мыс Доброй Надежды, «Адвенчер» миновал Мадагаскарский пролив и попал в сильнейшую бурю. Ураган угнал судно далеко на восток. Капитан мог лишь предполагать, что они находятся неподалеку от дальневосточного побережья Тихого океана.

Заметив землю, капитан отправил на баркасе несколько человек с целью добыть пресной воды. Гулливер тоже захотел высадиться на сушу.

Моряки разошлись в разные стороны. Гуляя по бесплодной равнине, Лемюэль с ужасом заметил, что его спутники сели в баркас и изо всех сил гребут к кораблю. Их преследовал какой-то великан.

Охваченный диким страхом Гулливер побежал прочь от берега и оказался на поле, где рос гигантский ячмень. Вскоре он увидел работников с серпами — таких же великанов.

Когда один из исполинов приблизился, Лемюэль громко закричал. Работник увидел его и позвал хозяина. Великаны долго с изумлением рассматривали крохотного человечка. Наконец, фермер завернул его в платок и отнес домой.

Гулливер оказался в ситуации, полностью противоположной прошлому путешествию. Теперь его окружали великаны, а он был лилипутом.

Лемюэль поставили на стол, за который сел хозяин и вся его семья. Ему накрошили мяса и хлеба и налили в наперсток вина. За обедом Гулливера испугали собаки и кошка хозяев, который были в несколько раз больше слона.

После обеда хозяйка уложила Гулливера спать на гигантской кровати. Проснувшись через пару часов он увидел двух подкрадывающихся к нему гигантских крыс. Достав тесак, Лемюэль убил одну, а вторую ранил и заставил убежать.

Глава II

Подругой Гулливера стала Глюмдальклич — дочь фермера. Девочка заботилась о маленьком человечке, уберегала его от опасностей и стала учить местному языку.

Вскоре по всей окрестности разошлись слухи о найденном необычном «зверьке». Один сосед, взглянув на Гулливера, посоветовал фермеру отвезти его в город и показать эту диковинку публике за деньги.

Показ человечка в городе пользовался огромным успехом. Люди толпой шли посмотреть, как Гулливер размахивает тесаком, произносит несложные фразы, кланяется, пьет вино и т. п.

Фермер решил отвезти находку в столицу. По дороге он заезжал в города и села, устраивал представление с Гулливером и лопатой греб деньги.

Глава III

После представления в столице слухи о маленьком человечке дошли до королевы. Она велела доставить к ней это чудо. Королева купила у фермера Гулливера. По его просьбе Глюмдальклич в качестве «нянюшки» тоже осталась при дворе.

Королевский столяр изготовил для Гулливера дом с мебелью — ящик, который Глюмдальклич могла носить с собой. Для человечка был сшит костюм.

Королева относилась к Гулливеру очень хорошо. Король часто беседовал с ним, расспрашивая о жизни в Европе. В целом, Лемюэлю жилось неплохо, если не считать неприятностей, связанных с разницей в размерах. Человечку нередко приходилось отбиваться тесаком от мух и пчел, которые были размером с птиц.

Глава IV

Королевство великанов называлось Бробдингнег. Оно было расположено на большом полуострове, выход с которого закрывали неприступные горы.

Столица королевства насчитывала 600 тыс. жителей. В стране было еще около пятидесяти крупных городов и много крепостей.

Гулливер часто выезжал из дворца вместе с королевой или Глюмдальклич. Специально для этих прогулок для него был изготовлен «походный» ящик, в котором находился гамак и привинченная к полу мебель.

Глава V

Из-за своего крохотного размера Гулливер часто попадал в очень неприятные ситуации, вызывавшие у великанов лишь смех. Однажды, например, его чуть было не убил град.

Королева велела соорудить для человечка бассейн и лодку, чтобы он продемонстрировал свое умение владеть веслами и парусом. Один раз слуга, наполнявший бассейн водой, случайно принес в ведре лягушку. Гулливеру пришлось отбиваться веслом от этого чудища.

В другой раз Гулливера схватила королевская обезьяна. Она утащила его на крышу и стала кормить пережеванной пищей из своего рта. К счастью, один из слуг забрался на крышу и спас Лемюэля.

Глава VI

Во время частых бесед с королем Гулливер подробно рассказал ему об Англии: о ее географическом положении, политическом устройстве, истории, обычаях и нравах жителей и т. д. Король высказал целый ряд критических замечаний относительно честности членов парламента, справедливости английской судебной системы, необходимости постоянно воевать с другими державами.

В итоге король заключил, что англичане — «порода маленьких отвратительных гадов», подверженных всевозможным порокам.

Глава VII

Гулливер с гордостью рассказал об изобретении пороха и предложил передать секрет его изготовления. Король наотрез отказался, когда узнал о последствиях применения огнестрельного оружия.

По мнению Гулливера, бробдингнежцы значительно уступали европейцам по уровню научного и умственного развития. У них не было отвлеченных наук. Законы были сформулированы очень кратко и не допускали различных толкований. Армия представляла собой народное ополчение.

Глава VIII

На третий год пребывания в стране великанов Гулливер отправился вместе с королем и королевой в поездку на южное побережье. Однажды он попросил слугу отнести его в «походном» ящике на берег.

Лемюэль прилег отдохнуть в гамаке. Внезапно он услышал какие-то удары по крыше ящика, а затем почувствовал, что поднимается в воздух. По шуму крыльев Гулливер понял, что его жилище схватил орел.

Через некоторое время орла атаковали собратья. Он выпустил ящик, который упал в море. Самостоятельно выбраться из ящика Гулливер не мог. Несколько часов он провел в тоске, пока вновь не услышал какие-то звуки снаружи.

Странный ящик заметили с английского корабля. Пропилив в крыше дыру, Гулливера освободили. Он рассказал капитану о стране великанов и показал некоторые вещи, подтверждающие его слова (огромные иголки, подаренное королевой кольцо и др.).

Лемюэль благополучно вернулся в Англию к своей семье. Он еще долгое время не мог привыкнуть к тому, что находится среди людей обычного размера.

Часть третья. Путешествие в Лапуту, Бальнибарби, Лаггнегг, Глаббдобдриб и Японию

Глава I

Несмотря на данную жене клятву оставаться дома, спустя два месяца Гулливер отправился в новое путешествие со знакомым капитаном. Покинув Англию, корабль через полгода прибыл в Тонкин.

По поручению капитана Гулливер нагрузил шлюп товарами и отправился торговать с туземцами. Судно взяли на абордаж два пиратских корабля. Лемюэлю сохранили жизнь, но посадили в челнок и пустили в открытое море.

Гулливер добрался до группы безлюдных островов и стал перебираться с одного на другой. Однажды он увидел высоко в небе какой-то огромный странный предмет. Вооружившись подзорной трубой, путешественник разглядел, что это — летающий остров, населенный людьми.

Гулливер стал кричать и размахивать руками. Остров снизился. Лемюэля на веревке подняли наверх.

Глава II

Летающий остров назывался Лапута. Гулливера сразу же поразили его жители. Они были настолько погружены в размышления, что имели при себе специальных слуг — «хлопальщиков». Эти слуги носили палки с привязанными пузырями, наполненными камешками. В их обязанности входило хлопать хозяев этими пузырями по губам и ушам, чтобы напомнить о необходимости говорить или слушать.

Гулливер был представлен королю Лапуты, после чего приступил к изучению местного языка.

Остров направился к находящейся на земле столице королевства — Лагадо. Перелет занял четыре с половиной дня. За это время Гулливер многое узнал о лапутянах.

Жители острова интересовались только чистой (отвлеченной) математикой и музыкой. Применять математические знания на практике они не умели и не хотели. Дома, одежда и вообще все изготовленные лапутянами вещи были кривыми, кособокими и крайне неудобными.

Глава III

Остров приводился в движение большим магнитом, расположенным в его центре. Положительный и отрицательный полюса взаимодействовали с железной рудой, залегающей под землей. Поворот магнита позволял изменять направление и скорость движения острова в воздухе.

Летающий остров позволял королю держать живущих на земле подданных в абсолютном повиновении. В случае бунта остров зависал над мятежным городом, лишая его солнечного света и дождей. Если бунтовщики упорствовали, король приказывал сбрасывать на них огромные камни. В крайних и очень редких случаях остров мог просто опуститься вниз, разрушив город и задавив всех его жителей.

Глава IV

Проведя на Лапуте два месяца и овладев местным языком, Гулливер попросил у короля позволения посетить столицу. Ему смертельно надоели жители острова, с которыми нельзя было общаться без помощи «хлопальщиков».

Лемюэля спустили в Лагадо — столицу королевства Бальнибарби. Он имел рекомендательное письмо к одному сановнику (Мьюноди), у которого и остановился погостить.

Осматривая город и его окрестности, Гулливер был поражен полуразрушенными домами, людьми в лохмотьях и незасеянными полями. При этом хозяйство сановника содержалось в идеальном порядке.

В ответ на недоумение Гулливера Мьюноди рассказал, что несколько десятилетий назад на Лупуте побывала часть жителей столицы. Вернувшись назад, они с восторгом описывали мудрость обитателей острова и вознамерились подражать им.

В королевстве появилась Академия прожектеров, занимающаяся изобретением более эффективных методов производства, новых орудий труда и т. д. Повальное увлечение изобретательством привело хозяйство страны в полный упадок. Ни один проект пока еще не был реализован.

Мьюноди до сих пор вел хозяйство старыми методами, вызывая этим упреки сограждан в ретроградстве и препятствии прогрессу. Он предложил Гулливеру самому посетить Академию и оценить ее работу.

Глава V

Академия занимал несколько строений. Гулливер познакомился с работами около пятисот прожектеров. Они разрабатывали самые немыслимые проекты по переработке нечистот в пищу, пережигании льда в порох, изготовлению пряжи из паутины и т. п.

Никакого практического результата проекты пока что не принесли.

Глава VI

Гулливер сам предложил одному ученому из Академии некоторые усовершенствования для раскрытия заговоров, состоящие в тщательном анализе и расшифровке писем подозреваемых лиц.

Глава VII

Покинув Лагадо, путешественник посетил остров Глаббдобдриб, название которого можно перевести как «Остров волшебников». Его повелитель с помощью магических чар мог вызывать духи умерших людей.

Гулливер получил возможность побеседовать с великими деятелями прошлых веков. По его просьбе властитель острова вызвал духи многих прославленных политических деятелей, полководцев и мыслителей.

Глава VIII

На протяжении нескольких дней Лемюэль встречался и беседовал с учеными, королями, политиками, представителями знатных родов. Духи умерших не могли врать. Благодаря этому Гулливер узнал, насколько искажены знаменитые исторические события и какую огромную роль в истории играли ложь, предательство, вероломство, измена и бесчестие.

Глава IX

Гулливер отправился на остров Лаггнегг, где был сначала арестован таможенником, а затем приглашен к королю. Путешественник был милостиво принят повелителем, совершив при этом довольно-таки унизительный обряд. Допущенные к аудиенции лица должны были ползти к трону, слизывая языком пыль с пола.

Глава X

Лемюэль узнал, что на Лаггнегге живут струльдбруги — бессмертные люди. В столетие на острове рождается два-три таких человека.

Гулливер пришел в восторг и сказал, что мог бы принести огромную пользу отечеству, если бы родился бессмертным. Эти слова вызвали улыбки у лаггнежцев.

Путешественнику рассказали о жизни и судьбе струльдбругов. Бессмертие не сохраняет здоровье и силу человека. К восьмидесяти годам струльдбруг, как и обычные люди, превращается в дряхлого старика. Он становится жадным, завистливым, теряет память и ясность ума. В восемьдесят лет закон лишает бессмертного всех гражданских прав. Он живет лишь на небольшое государственное пособие и обречен вечно влачить жалкое нищенское существование.

Гулливер увидел нескольких струльдбругов, вызвавших в нем отвращение.

Глава XI

Чтобы вернуться на родину, Гулливер, выдав себя за голландца, отправился в Японию. Там он устроился хирургом на голландский корабль и через Амстердам добрался до Англии.

Часть четвертая. Путешествие в страну гуигнгнмов

Глава I

Спустя пять месяцев Гулливер получил приглашение стать капитаном купеческого корабля, отправлявшегося в Индийский океан. Лемюэль принял приглашение и вновь покинул Англию.

Неподалеку от Мадагаскара команда взбунтовалась и арестовала Гулливера, намереваясь заняться пиратством. Пленника высадили на каком-то острове.

Гулливер пошел вглубь неизвестной земли и вскоре увидел несколько отвратительных существ, напоминающих одновременно обезьяну и человека. Толпа этих мерзких полулюдей окружила путешественника, вынудив его отбиваться тесаком.

Внезапно существа с криками разбежались. Гулливер заметил приближающегося к нему серого коня в яблоках. Он долго с интересом разглядывал человека. Затем подошел еще один конь. В их ржании можно было различить членораздельные звуки.

Кони с удивлением рассматривали Гулливера и дотрагивались копытами до его одежды. Затем они сделали человеку знак проследовать за собой.

Глава II

Кони привели Гулливера к длинному строению и знаками пригласили войти. Путешественник увидел внутри несколько кобылиц и жеребят, ведущих себя, как люди в собственном доме. Лемюэль ничего не мог понять. Он думал, что сошел с ума или стал жертвой какого-то колдовства.

Серый конь-хозяин, глядя на человека, часто повторял слово «йеху». Он подвел Гулливера к человекообразному существу и стал их сравнивать. Судя по всему, коня удивляла одежда.

Лемюэль внимательно прислушивался к ржанию и вскоре запомнил несколько слов «лошадиного языка». Он смог попросить молока и ячменя, зерна которого истолок в муку и испек лепешку.

Глава III

Гулливер понял, что в этих землях господствующими существами являются кони, называющие себя гуигнгнами. Человекообразные скоты (йеху) прислуживают им в качестве рабов.

С помощью коня-хозяина Лемюэль стал энергично изучать местный язык и спустя три месяца уже мог довольно-таки сносно говорить на нем.

Гулливер рассказал о себе и о том, как попал в страну гуигнгнмов, вызвав у хозяина сильнейшее недоверие. Конь не мог поверить, что где-то далеко живут йеху, обладающие разумом.

Глава IV

Попросив хозяина не сердиться, Гулливер рассказал, как у него на родине обходятся с лошадьми. Конь пришел в негодование, узнав о верховой езде и наказаниях, которым подвергают йеху гуигнгнмов.

С трудом подбирая нужные слова и используя сравнения, Гулливер вкратце описал нравы и обычаи своих соплеменников. Конь был поражен тем, на какие ужасные поступки способны обладающие разумом существа. У гуигнгнмов даже не было терминов, обозначающих такие понятия, как властолюбие, жадность, обман и т. п.

Глава V

Гулливер рассказал о бесконечных кровопролитных войнах, ведущихся европейскими странами и о применяющимся при этом смертоносном оружии.

Гуигнгнм узнал, что на родине путешественника законы не защищают человека, а скорее направлены против него. Лемюэль подробно описал многолетние судебные процессы, приводящие к разорению обеих тяжущихся сторон. В выигрыше всегда оказываются лишь алчные и лживые судьи.

Глава VI

Гулливер сообщил хозяину о значении денег, ради обладания которыми многие люди идут на обман и преступление. Ему с трудом удалось объяснить гуигнгнму, что такое роскошные вещи, изысканная еда и алкогольные напитки.

Лемюэль весьма критически оценил деятельность европейских политиков, в среде которых царит «наглость, ложь и подкуп». Представителей высшего сословия он назвал «смесью хандры, тупоумия, невежества… и спеси».

Глава VII

Подробный рассказ Гулливера о своем отечестве и соплеменниках занял несколько дней. Когда он закончил, хозяин высказал свое заключение.

Конь обнаружил множество сходных черт между людьми и йеху. Мерзкие скоты отличаются прожорливостью, жадностью, ленью, хитростью и склонностью к обману. Среди йеху ценятся совершенно бесполезные блестящие камни, которые они собирают и прячут в тайниках. Из-за этих камней между ними постоянно происходят ожесточенные драки.

Гуигнгнм привел еще несколько примеров поведения йеху (подобострастие, ненависть к чужакам, разврат и др.), которые в точности повторяли описание Гулливером нравов своих соотечественников.

Глава VIII

Путешественник прожил в стране гуигнгнмов три года и за это время оценил, насколько их порядки и нравы превосходят человеческие.

Гуигнгнмы ведут самый добродетельный образ жизни. Превыше всего они ценят дружбу. Разумные кони не имеют никакого понятия об обмане, ревности, жадности, воровстве. В своих детях они воспитывают умеренность и трудолюбие.

Для решения важных вопросов, касающихся всей страны, раз в четыре года собирается всеобщее собрание гуигнгнмов, которое продолжается несколько дней.

Глава IX

Одно из таких собраний прошло незадолго до того, как Гулливер покинул земли гуигнгнмов. На нем решался вопрос о полном уничтожении мерзких йеху. Позже Лемюэль узнал, что на этом собрании обсуждалась и его дальнейшая судьба.

Гулливер отметил как достоинства, так и недостатки в жизни разумных коней. Гуигнгнмы не занимались науками и не были знакомы с письменностью. В различных работах они использовали каменные орудия; умели строить жилища и изготовлять глиняную и деревянную посуду.

Глава X

Лемюэль наслаждался спокойной и безмятежной жизнью среди гуигнгнмов. Он соорудил себе жилище, сшил одежду, питался простой и здоровой пищей.

Почитая разумных коней за образец всех добродетелей, Гулливер стал подражать им. Он с отвращением вспоминал о своих соотечественниках и даже не задумывался о возвращении в Англию.

Однажды хозяин позвал путешественника к себе и признался, что на последнем всеобщем собрании было принято решение отправить «разумного йеху» на родину. Он пообещал Гулливеру помочь изготовить лодку.

Услышав это решение, Лемюэль лишился чувств. Придя в себя, он сказал, что подчинится собранию, хотя мечтал бы навсегда остаться среди гуигнгнмов.

За полтора месяца Гулливер сделал большую прочную лодку и заготовил припасы для плавания. Простившись с хозяином, он вышел в море.

Глава XI

Взяв курс строго на восток, путешественник добрался до побережья Новой Голландии (Австралии). Там он чуть не попал в плен к дикарям, а затем был найден матросами с португальского корабля.

Гулливер испытывал отвращение к людям, в которых он видел мерзких йеху. Капитану судна даже пришлось применить силу, чтобы не дать ему сбежать.

Лемюэля привезли в Лиссабон, где он провел несколько дней, привыкая к человеческому обществу. Затем капитан посадил путешественника на английский корабль, который доставил его на родину.

С момента возвращения Гулливера прошло уже пять лет, но он до сих пор запрещает членам семьи прикасаться к нему. Он предпочитает подолгу разговаривать с двумя купленными жеребцами, которые напоминают ему о жизни среди гуигнгнмов.

Глава XII

В заключение Гулливер, обращаясь к читателям, заверяет, что описанные им путешествия — чистая правда. Он уверен, что когда-нибудь это подтвердят другие путешественники.

Лемюэль не советует соотечественникам пытаться захватить и превратить в колонии земли, на которых он побывал. Остров лилипутов слишком мал. Великанов не сможет одолеть никакая армия. Совершенно бесполезно сражаться против летающего острова. Даже не имеющие оружия гуигнгнмы окажут захватчикам яростное сопротивление.

Кратко об истории создания произведения

Замысел романа возник у Свифта в 1713-1714 гг., когда он и его близкие друзья решили написать сатиру на невежество и псевдоученость в жанре путешествий.

Работу над книгой писатель начал в 1720 г. и закончил ее в 1725 г. Опасаясь преследований цензуры, Свифт скрыл свое авторство.

Роман был опубликован в 1726 г. с сокращением наиболее резких высказываний. На протяжении двух столетий «Путешествия Гулливера» издавались с пропусками и поправками. Оригинальная авторская рукопись без сокращений впервые была издана в 1922 г.

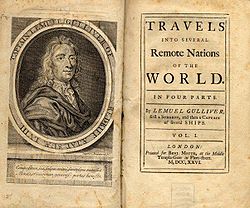

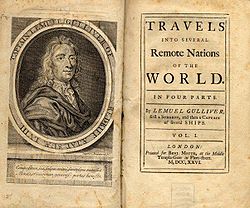

First edition of Gulliver’s Travels |

|

| Author | Jonathan Swift |

|---|---|

| Original title | Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Satire, fantasy |

| Publisher | Benjamin Motte |

|

Publication date |

28 October 1726 (296 years ago) |

| Media type | |

|

Dewey Decimal |

823.5 |

| Text | Gulliver’s Travels at Wikisource |

Gulliver’s Travels, or Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships is a 1726 prose satire[1][2] by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift, satirising both human nature and the «travellers’ tales» literary subgenre. It is Swift’s best known full-length work, and a classic of English literature. Swift claimed that he wrote Gulliver’s Travels «to vex the world rather than divert it».

The book was an immediate success. The English dramatist John Gay remarked: «It is universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery.»[3] In 2015, Robert McCrum released his selection list of 100 best novels of all time, where he called Gulliver’s Travels «a satirical masterpiece».[4]

Plot[edit]

Locations visited by Gulliver, according to Arthur Ellicott Case. Case contends that the maps in the published text were drawn by someone who did not follow Swift’s geographical descriptions; to correct this, he makes changes such as placing Lilliput to the east of Australia instead of the west. [5]

Part I: A Voyage to Lilliput[edit]

Mural depicting Gulliver surrounded by citizens of Lilliput.

The travel begins with a short preamble in which Lemuel Gulliver gives a brief outline of his life and history before his voyages.

- 4 May 1699 – 13 April 1702

During his first voyage, Gulliver is washed ashore after a shipwreck and finds himself a prisoner of a race of tiny people, less than 6 inches (15 cm) tall, who are inhabitants of the island country of Lilliput. After giving assurances of his good behaviour, he is given a residence in Lilliput and becomes a favourite of the Lilliput Royal Court. He is also given permission by the King of Lilliput to go around the city on condition that he must not hurt their subjects.

At first, the Lilliputians are hospitable to Gulliver, but they are also wary of the threat that his size poses to them. The Lilliputians reveal themselves to be a people who put great emphasis on trivial matters. For example, which end of an egg a person cracks becomes the basis of a deep political rift within that nation. They are a people who revel in displays of authority and performances of power. Gulliver assists the Lilliputians to subdue their neighbours the Blefuscudians by stealing their fleet. However, he refuses to reduce the island nation of Blefuscu to a province of Lilliput, displeasing the King and the royal court.

Gulliver is charged with treason for, among other crimes, urinating in the capital though he was putting out a fire. He is convicted and sentenced to be blinded. With the assistance of a kind friend, «a considerable person at court», he escapes to Blefuscu. Here, he spots and retrieves an abandoned boat and sails out to be rescued by a passing ship, which safely takes him back home with some Lilliputian animals he carries with him.

Part II: A Voyage to Brobdingnag[edit]

- 20 June 1702 – 3 June 1706

Gulliver soon sets out again. When the sailing ship Adventure is blown off course by storms and forced to sail for land in search of fresh water, Gulliver is abandoned by his companions and left on a peninsula on the western coast of the North American continent.

The grass of Brobdingnag is as tall as a tree. He is then found by a farmer who is about 72 ft (22 m) tall, judging from Gulliver estimating the man’s step being 10 yards (9 m). The giant farmer brings Gulliver home, and his daughter Glumdalclitch cares for Gulliver. The farmer treats him as a curiosity and exhibits him for money. After a while the constant display makes Gulliver sick, and the farmer sells him to the queen of the realm. Glumdalclitch (who accompanied her father while exhibiting Gulliver) is taken into the queen’s service to take care of the tiny man. Since Gulliver is too small to use their huge chairs, beds, knives and forks, the queen commissions a small house to be built for him so that he can be carried around in it; this is referred to as his «travelling box».

Between small adventures such as fighting giant wasps and being carried to the roof by a monkey, he discusses the state of Europe with the King of Brobdingnag. The king is not happy with Gulliver’s accounts of Europe, especially upon learning of the use of guns and cannon. On a trip to the seaside, his traveling box is seized by a giant eagle which drops Gulliver and his box into the sea where he is picked up by sailors who return him to England.

Part III: A Voyage to Laputa, Balnibarbi, Luggnagg, Glubbdubdrib and Japan[edit]

Gulliver discovers Laputa, the floating/flying island (illustration by J. J. Grandville)

- 5 August 1706 – 16 April 1710

Setting out again, Gulliver’s ship is attacked by pirates, and he is marooned close to a desolate rocky island near India. He is rescued by the flying island of Laputa, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music, mathematics, and astronomy but unable to use them for practical ends. Rather than using armies, Laputa has a custom of throwing rocks down at rebellious cities on the ground.

Gulliver tours Balnibarbi, the kingdom ruled from Laputa, as the guest of a low-ranking courtier and sees the ruin brought about by the blind pursuit of science without practical results, in a satire on bureaucracy and on the Royal Society and its experiments. At the Grand Academy of Lagado in Balnibarbi, great resources and manpower are employed on researching preposterous schemes such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers, softening marble for use in pillows, learning how to mix paint by smell, and uncovering political conspiracies by examining the excrement of suspicious persons (see muckraking). Gulliver is then taken to Maldonada, the main port of Balnibarbi, to await a trader who can take him on to Japan.

While waiting for a passage, Gulliver takes a short side-trip to the island of Glubbdubdrib which is southwest of Balnibarbi. On Glubbdubdrib, he visits a magician’s dwelling and discusses history with the ghosts of historical figures, the most obvious restatement of the «ancients versus moderns» theme in the book. The ghosts include Julius Caesar, Brutus, Homer, Aristotle, René Descartes, and Pierre Gassendi.

On the island of Luggnagg, he encounters the struldbrugs, people who are immortal. They do not have the gift of eternal youth, but suffer the infirmities of old age and are considered legally dead at the age of eighty.

After reaching Japan, Gulliver asks the Emperor «to excuse my performing the ceremony imposed upon my countrymen of trampling upon the crucifix», which the Emperor does. Gulliver returns home, determined to stay there for the rest of his days.

Part IV: A Voyage to the Land of the Houyhnhnms[edit]

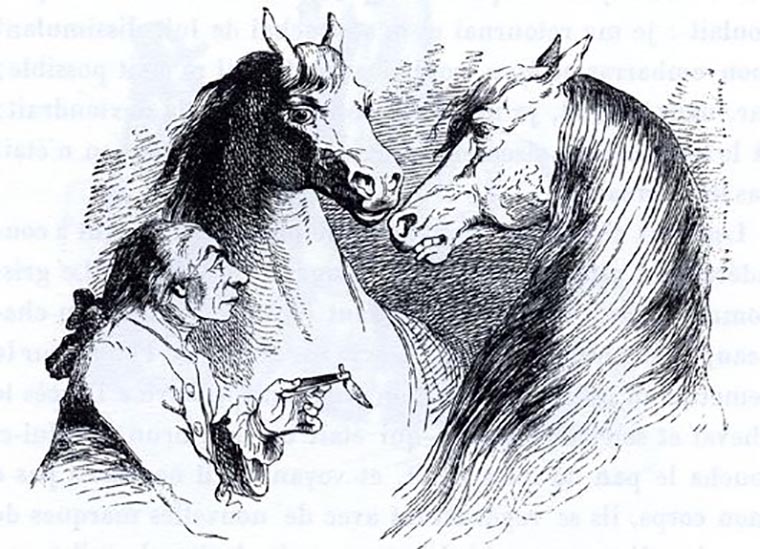

Gulliver in discussion with Houyhnhnms (1856 illustration by J.J. Grandville).

- 7 September 1710 – 5 December 1715

Despite his earlier intention of remaining at home, Gulliver returns to sea as the captain of a merchantman, as he is bored with his employment as a surgeon. On this voyage, he is forced to find new additions to his crew who, he believes, have turned against him. His crew then commits mutiny. After keeping him contained for some time, they resolve to leave him on the first piece of land they come across, and continue as pirates. He is abandoned in a landing boat and comes upon a race of deformed savage humanoid creatures to which he conceives a violent antipathy. Shortly afterwards, he meets the Houyhnhnms, a race of talking horses. They are the rulers while the deformed creatures that resemble human beings are called Yahoos.

Some scholars have identified the relationship between the Houyhnhnms and Yahoos as a master/ slave dynamic.[6]

Gulliver becomes a member of a horse’s household and comes to both admire and emulate the Houyhnhnms and their way of life, rejecting his fellow humans as merely Yahoos endowed with some semblance of reason which they only use to exacerbate and add to the vices Nature gave them. However, an Assembly of the Houyhnhnms rules that Gulliver, a Yahoo with some semblance of reason, is a danger to their civilization and commands him to swim back to the land that he came from. Gulliver’s «Master,» the Houyhnhnm who took him into his household, buys him time to create a canoe to make his departure easier. After another disastrous voyage, he is rescued against his will by a Portuguese ship. He is disgusted to see that Captain Pedro de Mendez, whom he considers a Yahoo, is a wise, courteous, and generous person.

He returns to his home in England, but is unable to reconcile himself to living among «Yahoos» and becomes a recluse, remaining in his house, avoiding his family and his wife, and spending several hours a day speaking with the horses in his stables.

Composition and history[edit]

It is uncertain exactly when Swift started writing Gulliver’s Travels. (Much of the writing was done at Loughry Manor in Cookstown, County Tyrone, whilst Swift stayed there.) Some sources[which?] suggest as early as 1713 when Swift, Gay, Pope, Arbuthnot and others formed the Scriblerus Club with the aim of satirising popular literary genres.[7] According to these accounts, Swift was charged with writing the memoirs of the club’s imaginary author, Martinus Scriblerus, and also with satirising the «travellers’ tales» literary subgenre. It is known from Swift’s correspondence that the composition proper began in 1720 with the mirror-themed Parts I and II written first, Part IV next in 1723 and Part III written in 1724; but amendments were made even while Swift was writing Drapier’s Letters. By August 1725 the book was complete; and as Gulliver’s Travels was a transparently anti-Whig satire, it is likely that Swift had the manuscript copied so that his handwriting could not be used as evidence if a prosecution should arise, as had happened in the case of some of his Irish pamphlets (the Drapier’s Letters). In March 1726 Swift travelled to London to have his work published; the manuscript was secretly delivered to the publisher Benjamin Motte, who used five printing houses to speed production and avoid piracy.[8] Motte, recognising a best-seller but fearing prosecution, cut or altered the worst offending passages (such as the descriptions of the court contests in Lilliput and the rebellion of Lindalino), added some material in defence of Queen Anne to Part II, and published it. The first edition was released in two volumes on 28 October 1726, priced at 8s. 6d.[9]

Motte published Gulliver’s Travels anonymously, and as was often the way with fashionable works, several follow-ups (Memoirs of the Court of Lilliput), parodies (Two Lilliputian Odes, The first on the Famous Engine With Which Captain Gulliver extinguish’d the Palace Fire…) and «keys» (Gulliver Decipher’d and Lemuel Gulliver’s Travels into Several Remote Regions of the World Compendiously Methodiz’d, the second by Edmund Curll who had similarly written a «key» to Swift’s Tale of a Tub in 1705) were swiftly produced. These were mostly printed anonymously (or occasionally pseudonymously) and were quickly forgotten. Swift had nothing to do with them and disavowed them in Faulkner’s edition of 1735. Swift’s friend Alexander Pope wrote a set of five Verses on Gulliver’s Travels, which Swift liked so much that he added them to the second edition of the book, though they are rarely included.

Faulkner’s 1735 edition[edit]

In 1735 an Irish publisher, George Faulkner, printed a set of Swift’s works, Volume III of which was Gulliver’s Travels. As revealed in Faulkner’s «Advertisement to the Reader», Faulkner had access to an annotated copy of Motte’s work by «a friend of the author» (generally believed to be Swift’s friend Charles Ford) which reproduced most of the manuscript without Motte’s amendments, the original manuscript having been destroyed. It is also believed that Swift at least reviewed proofs of Faulkner’s edition before printing, but this cannot be proved. Generally, this is regarded as the Editio Princeps of Gulliver’s Travels with one small exception. This edition had an added piece by Swift, A letter from Capt. Gulliver to his Cousin Sympson, which complained of Motte’s alterations to the original text, saying he had so much altered it that «I do hardly know mine own work» and repudiating all of Motte’s changes as well as all the keys, libels, parodies, second parts and continuations that had appeared in the intervening years. This letter now forms part of many standard texts.

Lindalino[edit]

The five-paragraph episode in Part III, telling of the rebellion of the surface city of Lindalino against the flying island of Laputa, was an allegory of the affair of Drapier’s Letters of which Swift was proud. Lindalino represented Dublin and the impositions of Laputa represented the British imposition of William Wood’s poor-quality copper currency. Faulkner had omitted this passage, either because of political sensitivities raised by an Irish publisher printing an anti-British satire, or possibly because the text he worked from did not include the passage. In 1899 the passage was included in a new edition of the Collected Works. Modern editions derive from the Faulkner edition with the inclusion of this 1899 addendum.

Isaac Asimov notes in The Annotated Gulliver that Lindalino is generally taken to be Dublin, being composed of double lins; hence, Dublin.[10]

Major themes[edit]

Gulliver’s Travels has been described as a Menippean satire, a children’s story, proto-science fiction and a forerunner of the modern novel.

Published seven years after Daniel Defoe’s successful Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels may be read as a systematic rebuttal of Defoe’s optimistic account of human capability. In The Unthinkable Swift: The Spontaneous Philosophy of a Church of England Man, Warren Montag argues that Swift was concerned to refute the notion that the individual precedes society, as Defoe’s work seems to suggest. Swift regarded such thought as a dangerous endorsement of Thomas Hobbes’ radical political philosophy and for this reason Gulliver repeatedly encounters established societies rather than desolate islands. The captain who invites Gulliver to serve as a surgeon aboard his ship on the disastrous third voyage is named Robinson.

Allan Bloom asserts that Swift’s lampooning of the experiments of Laputa is the first questioning by a modern liberal democrat of the effects and cost on a society which embraces and celebrates policies pursuing scientific progress.[11] Swift wrote:

The first man I saw was of a meagre aspect, with sooty hands and face, his hair and beard long, ragged, and singed in several places. His clothes, shirt, and skin, were all of the same colour. He has been eight years upon a project for extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, which were to be put in phials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw inclement summers. He told me, he did not doubt, that, in eight years more, he should be able to supply the governor’s gardens with sunshine, at a reasonable rate: but he complained that his stock was low, and entreated me «to give him something as an encouragement to ingenuity, especially since this had been a very dear season for cucumbers». I made him a small present, for my lord had furnished me with money on purpose, because he knew their practice of begging from all who go to see them.

A possible reason for the book’s classic status is that it can be seen as many things to many people. Broadly, the book has three themes:

- A satirical view of the state of European government, and of petty differences between religions

- An inquiry into whether people are inherently corrupt or whether they become corrupted

- A restatement of the older «ancients versus moderns» controversy previously addressed by Swift in The Battle of the Books

In storytelling and construction the parts follow a pattern:

- The causes of Gulliver’s misadventures become more malignant as time goes on—he is first shipwrecked, then abandoned, then attacked by strangers, then attacked by his own crew.

- Gulliver’s attitude hardens as the book progresses—he is genuinely surprised by the viciousness and politicking of the Lilliputians but finds the behaviour of the Yahoos in the fourth part reflective of the behaviour of people.

- Each part is the reverse of the preceding part—Gulliver is big/small/wise/ignorant, the countries are complex/simple/scientific/natural, and Gulliver perceives the forms of government as worse/better/worse/better than Britain’s (although Swift’s opinions on this matter are unclear).

- Gulliver’s viewpoint between parts is mirrored by that of his antagonists in the contrasting part—Gulliver sees the tiny Lilliputians as being vicious and unscrupulous, and then the king of Brobdingnag sees Europe in exactly the same light; Gulliver sees the Laputians as unreasonable, and his Houyhnhnm master sees humanity as equally so.

- No form of government is ideal—the simplistic Brobdingnagians enjoy public executions and have streets infested with beggars, the honest and upright Houyhnhnms who have no word for lying are happy to suppress the true nature of Gulliver as a Yahoo and are equally unconcerned about his reaction to being expelled.

- Specific individuals may be good even where the race is bad—Gulliver finds a friend in each of his travels and, despite Gulliver’s rejection and horror toward all Yahoos, is treated very well by the Portuguese captain, Don Pedro, who returns him to England at the book’s end.

Of equal interest is the character of Gulliver himself—he progresses from a cheery optimist at the start of the first part to the pompous misanthrope of the book’s conclusion and we may well have to filter our understanding of the work if we are to believe the final misanthrope wrote the whole work. In this sense, Gulliver’s Travels is a very modern and complex work. There are subtle shifts throughout the book, such as when Gulliver begins to see all humans, not just those in Houyhnhnm-land, as Yahoos.[12]

Throughout, Gulliver is presented as being gullible. He generally accepts what he is told at face value; he rarely perceives deeper meanings; and he is an honest man who expects others to be honest. This makes for fun and irony: what Gulliver says can be trusted to be accurate, and he does not always understand the meaning of what he perceives.

Also, although Gulliver is presented as a commonplace «everyman» with only a basic education, he possesses a remarkable natural gift for language. He quickly becomes fluent in the native tongues of the strange lands in which he finds himself, a literary device that adds verisimilitude and humour to Swift’s work.

Despite the depth and subtlety of the book, as well as frequent off-colour and black humour, it is often classified as a children’s story because of the popularity of the Lilliput section (frequently bowdlerised) as a book for children. Indeed, many adaptations of the story are squarely aimed at a young audience, and one can still buy books entitled Gulliver’s Travels which contain only parts of the Lilliput voyage, and occasionally the Brobdingnag section.

Misogyny[edit]

Although Swift is often accused of misogyny in this work, many scholars believe Gulliver’s blatant misogyny to be intentional, and that Swift uses satire to openly mock misogyny throughout the book. One of the most cited examples of this comes from Gulliver’s description of a Brobdingnagian woman:

I must confess no Object ever disgusted me so much as the Sight of her monstrous Breast, which I cannot tell what to compare with, so as to give the curious Reader an Idea of its Bulk, Shape, and Colour…. This made me reflect upon the fair Skins of our English Ladies, who appear so beautiful to us, only because they are of our own Size, and their Defects not to be seen but through a magnifying glass….

This open critique towards aspects of the female body is something that Swift often brings up in other works of his, particularly in poems such as The Lady’s Dressing Room and A Beautiful Young Nymph Going To Bed.[13]

A criticism of Swift’s use of misogyny by Felicity A. Nussbaum proposes the idea that «Gulliver himself is a gendered object of satire, and his antifeminist sentiments may be among those mocked». Gulliver’s own masculinity is often mocked, seen in how he is made to be a coward among the Brobdingnag people, repressed by the people of Lilliput, and viewed as an inferior Yahoo among the Houyhnhnms.[12]

Nussbaum goes on to say in her analysis of the misogyny of the stories that in the adventures, particularly in the first story, the satire isn’t singularly focused on satirizing women, but to satirize Gulliver himself as a politically naive and inept giant whose masculine authority comically seems to be in jeopardy.[14]

Another criticism of Swift’s use of misogyny delves into Gulliver’s repeated use of the word ‘nauseous’, and the way that Gulliver is fighting his emasculation by commenting on how he thinks the women of Brobdingnag are disgusting.

Swift has Gulliver frequently invoke the sensory (as opposed to reflective) word «nauseous» to describe this and other magnified images in Brobdingnag not only to reveal the neurotic depths of Gulliver’s misogyny, but also to show how male nausea can be used as a pathetic countermeasure against the perceived threat of female consumption. Swift has Gulliver associate these magnified acts of female consumption with the act of «throwing-up»—the opposite of and antidote to the act of gastronomic consumption.[15]

This commentary of Deborah Needleman Armintor relies upon the way that the giant women do with Gulliver as they please, in much the same way as one might play with a toy, and get it to do everything one can think of. Armintor’s comparison focuses on the pocket microscopes that were popular in Swift’s time. She talks about how this instrument of science was transitioned to something toy-like and accessible, so it shifted into something that women favored, and thus men lost interest. This is similar to the progression of Gulliver’s time in Brobdingnag, from man of science to women’s plaything.

Comic misanthropy[edit]

Misanthropy is a theme that scholars have identified in Gulliver’s Travels. Arthur Case, R.S. Crane, and Edward Stone discuss Gulliver’s development of misanthropy and come to the consensus that this theme ought to be viewed as comical rather than cynical.[16][17][18]

In terms of Gulliver’s development of misanthropy, these three scholars point to the fourth voyage. According to Case, Gulliver is at first averse to identifying with the Yahoos, but, after he deems the Houyhnhnms superior, he comes to believe that humans (including his fellow Europeans) are Yahoos due to their shortcomings. Perceiving the Houyhnhnms as perfect, Gulliver thus begins to perceive himself and the rest of humanity as imperfect.[16] According to Crane, when Gulliver develops his misanthropic mindset, he becomes ashamed of humans and views them more in line with animals.[17] This new perception of Gulliver’s, Stone claims, comes about because the Houyhnhnms’ judgement pushes Gulliver to identify with the Yahoos.[18] Along similar lines, Crane holds that Gulliver’s misanthropy is developed in part when he talks to the Houyhnhnms about mankind because the discussions lead him to reflect on his previously held notion of humanity. Specifically, Gulliver’s master, who is a Houyhnhnm, provides questions and commentary that contribute to Gulliver’s reflectiveness and subsequent development of misanthropy.[17] However, Case points out that Gulliver’s dwindling opinion of humans may be blown out of proportion due to the fact that he is no longer able to see the good qualities that humans are capable of possessing. Gulliver’s new view of humanity, then, creates his repulsive attitude towards his fellow humans after leaving Houyhnhnmland.[16] But in Stone’s view, Gulliver’s actions and attitude upon his return can be interpreted as misanthropy that is exaggerated for comic effect rather than for a cynical effect. Stone further suggests that Gulliver goes mentally mad and believes that this is what leads Gulliver to exaggerate the shortcomings of humankind.[18]

Another aspect that Crane attributes to Gulliver’s development of misanthropy is that when in Houyhnhnmland, it is the animal-like beings (the Houyhnhnms) who exhibit reason and the human-like beings (the Yahoos) who seem devoid of reason; Crane argues that it is this switch from Gulliver’s perceived norm that leads the way for him to question his view of humanity. As a result, Gulliver begins to identify humans as a type of Yahoo. To this point, Crane brings up the fact that a traditional definition of man—Homo est animal rationale (Humans are rational animals)—was prominent in academia around Swift’s time. Furthermore, Crane argues that Swift had to study this type of logic (see Porphyrian Tree) in college, so it is highly likely that he intentionally inverted this logic by placing the typically given example of irrational beings—horses—in the place of humans and vice versa.[17]

Stone points out that Gulliver’s Travels takes a cue from the genre of the travel book, which was popular during Swift’s time period. From reading travel books, Swift’s contemporaries were accustomed to beast-like figures of foreign places; thus, Stone holds that the creation of the Yahoos was not out of the ordinary for the time period. From this playing off of familiar genre expectations, Stone deduces that the parallels that Swift draws between the Yahoos and humans is meant to be humorous rather than cynical. Even though Gulliver sees Yahoos and humans as if they are one and the same, Stone argues that Swift did not intend for readers to take on Gulliver’s view; Stone states that the Yahoos’ behaviors and characteristics that set them apart from humans further supports the notion that Gulliver’s identification with Yahoos is not meant to be taken to heart. Thus, Stone sees Gulliver’s perceived superiority of the Houyhnhnms and subsequent misanthropy as features that Swift used to employ the satirical and humorous elements characteristic of the Beast Fables of travel books that were popular with his contemporaries; as Swift did, these Beast Fables placed animals above humans in terms of morals and reason, but they were not meant to be taken literally.[18]

Character analysis[edit]

Pedro de Mendez is the name of the Portuguese captain who rescues Gulliver in Book IV. When Gulliver is forced to leave the Island of the Houyhnhnms, his plan is «to discover some small Island uninhabited» where he can live in solitude. Instead, he is picked up by Don Pedro’s crew. Despite Gulliver’s appearance—he is dressed in skins and speaks like a horse—Don Pedro treats him compassionately and returns him to Lisbon.

Though Don Pedro appears only briefly, he has become an important figure in the debate between so-called soft school and hard school readers of Gulliver’s Travels. Some critics contend that Gulliver is a target of Swift’s satire and that Don Pedro represents an ideal of human kindness and generosity. Gulliver believes humans are similar to Yahoos in the sense that they make «no other use of reason, than to improve and multiply … vices».[19] Captain Pedro provides a contrast to Gulliver’s reasoning, proving humans are able to reason, be kind, and most of all: civilized. Gulliver sees the bleak fallenness at the center of human nature, and Don Pedro is merely a minor character who, in Gulliver’s words, is «an Animal which had some little Portion of Reason».[20]

Political allusions[edit]

While we cannot make assumptions about Swift’s intentions, part of what makes his writing so engaging throughout time is speculating the various political allusions within it. These allusions tend to go in and out of style, but here are some of the common (or merely interesting) allusions asserted by Swiftian scholars. Part I is probably responsible for the greatest number of political allusions, ranging from consistent allegory to minute comparisons. One of the most commonly noted parallels is that the wars between Lilliput and Blefuscu resemble those between England and France.[21] The enmity between the low heels and the high heels is often interpreted as a parody of the Whigs and Tories, and the character referred to as Flimnap is often interpreted as an allusion to Sir Robert Walpole, a British statesman and Whig politician who Swift had a personally turbulent relationship with.

In Part III, the grand Academy of Lagado in Balnibarbi resembles and satirizes the Royal Society, which Swift was openly critical of. Furthermore, «A. E. Case, acting on a tipoff offered by the word ‘projectors,’ found [the Academy] to be the hiding place of many of those speculators implicated in the South Sea Bubble.»[22] According to Treadwell, however, these implications extend beyond the speculators of the South Sea Bubble to include the many projectors of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century England, including Swift himself. Not only is Swift satirizing the role of the projector in contemporary English politics, which he dabbled in during his younger years, but the role of the satirist, whose goals align with that of a projector: «The less obvious corollary of that word [projector] is that it must include the poor deluded satirist himself, since satire is, in its very essence, the wildest of all projects — a scheme to reform the world.»[22]

Ann Kelly describes Part IV of The Travels and the Yahoo-Houyhnhnm relationship as an allusion to that of the Irish and the British: «The term that Swift uses to describe the oppression in both Ireland and Houyhnhnmland is ‘slavery’; this is not an accidental word choice, for Swift was well aware of the complicated moral and philosophical questions raised by the emotional designation ‘slavery.’ The misery of the Irish in the early eighteenth century shocked Swift and all others who witnessed it; the hopeless passivity of the people in this desolate land made it seem as if both the minds and bodies of the Irish were enslaved.»[23] Kelly goes on to write: «Throughout the Irish tracts and poems, Swift continually vacillates as to whether the Irish are servile because of some defect within their character or whether their sordid condition is the result of a calculated policy from without to reduce them to brutishness. Although no one has done so, similar questions could be asked about the Yahoos, who are slaves to the Houyhnhnms.» However, Kelly does not suggest a wholesale equivalence between Irish and Yahoos, which would be reductive and omit the various other layers of satire at work in this section.

Language[edit]

In his annotated edition of the book published in 1980, Isaac Asimov claims that «making sense out of the words and phrases introduced by Swift…is a waste of time,» and these words were invented nonsense. However, Irving Rothman, a professor at University of Houston, points out that the language may have been derived from Hebrew, which Swift had studied at Trinity College Dublin.[24]

Reception[edit]

The book was very popular upon release and was commonly discussed within social circles.[25] Public reception widely varied, with the book receiving an initially enthusiastic reaction with readers praising its satire, and some reporting that the satire’s cleverness sounded like a realistic account of a man’s travels.[26] James Beattie commended Swift’s work for its «truth» regarding the narration and claims that «the statesman, the philosopher, and the critick, will admire his keenness of satire, energy of description, and vivacity of language», noting that even children can enjoy the novel.[27] As popularity increased, critics came to appreciate the deeper aspects of Gulliver’s Travels. It became known for its insightful take on morality, expanding its reputation beyond just humorous satire.[26]

Despite its initial positive reception, the book faced backlash. Viscount Bolingbroke, a friend of Swift and one of the first critics of the book, criticised the author for his overt use of misanthropy.[26] Other negative responses to the book also looked towards its portrayal of humanity, which was considered inaccurate. Swifts’s peers rejected the book on claims that its themes of misanthropy were harmful and offensive. They criticized its satire for exceeding what was deemed acceptable and appropriate, including the Houyhnhnms and Yahoos’s similarities to humans.[27] There was also controversy surrounding the political allegories. Readers enjoyed the political references, finding them humorous. However, members of the Whig party were offended, believing that Swift mocked their politics.[26]

British novelist and journalist William Makepeace Thackeray described Swift’s work as «blasphemous», saying its critical view of mankind was ludicrous and overly harsh. He concluded that he could not understand the origins of Swift’s critiques on humanity.[27]

Cultural influences[edit]

The term Lilliputian has entered many languages as an adjective meaning «small and delicate». There is a brand of small cigar called Lilliput, and a series of collectable model houses known as «Lilliput Lane». The smallest light bulb fitting (5 mm diameter) in the Edison screw series is called the «Lilliput Edison screw». In Dutch and Czech, the words Lilliputter and lilipután, respectively, are used for adults shorter than 1.30 meters. Conversely, Brobdingnagian appears in the Oxford English Dictionary as a synonym for very large or gigantic.

In like vein, the term yahoo is often encountered as a synonym for ruffian or thug. In the Oxford English Dictionary it is defined as «a rude, noisy, or violent person» and its origins attributed to Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.[28]

In the discipline of computer architecture, the terms big-endian and little-endian are used to describe two possible ways of laying out bytes of data in computer memory. The terms derive from one of the satirical conflicts in the book, in which two religious sects of Lilliputians are divided between those who crack open their soft-boiled eggs from the little end, the «Little-endians», and those who use the big end, the «Big-endians». The nomenclature was chosen as an irony, since the choice of which byte-order method to use is technically trivial (both are equally good), but actually still important: systems which do it one way are thus incompatible with those that do it the other way, and so it shouldn’t be left to each individual designer’s choice, resulting in a «holy war» over a triviality.[29]

It has been pointed out that the long and vicious war which started after a disagreement about which was the best end to break an egg is an example of the narcissism of small differences, a term Sigmund Freud coined in the early 1900s.[30]

In other works[edit]