This is a list of characters in One Thousand and One Nights (aka The Arabian Nights), the classic, medieval collection of Middle-Eastern folk tales.

Characters in the frame story[edit]

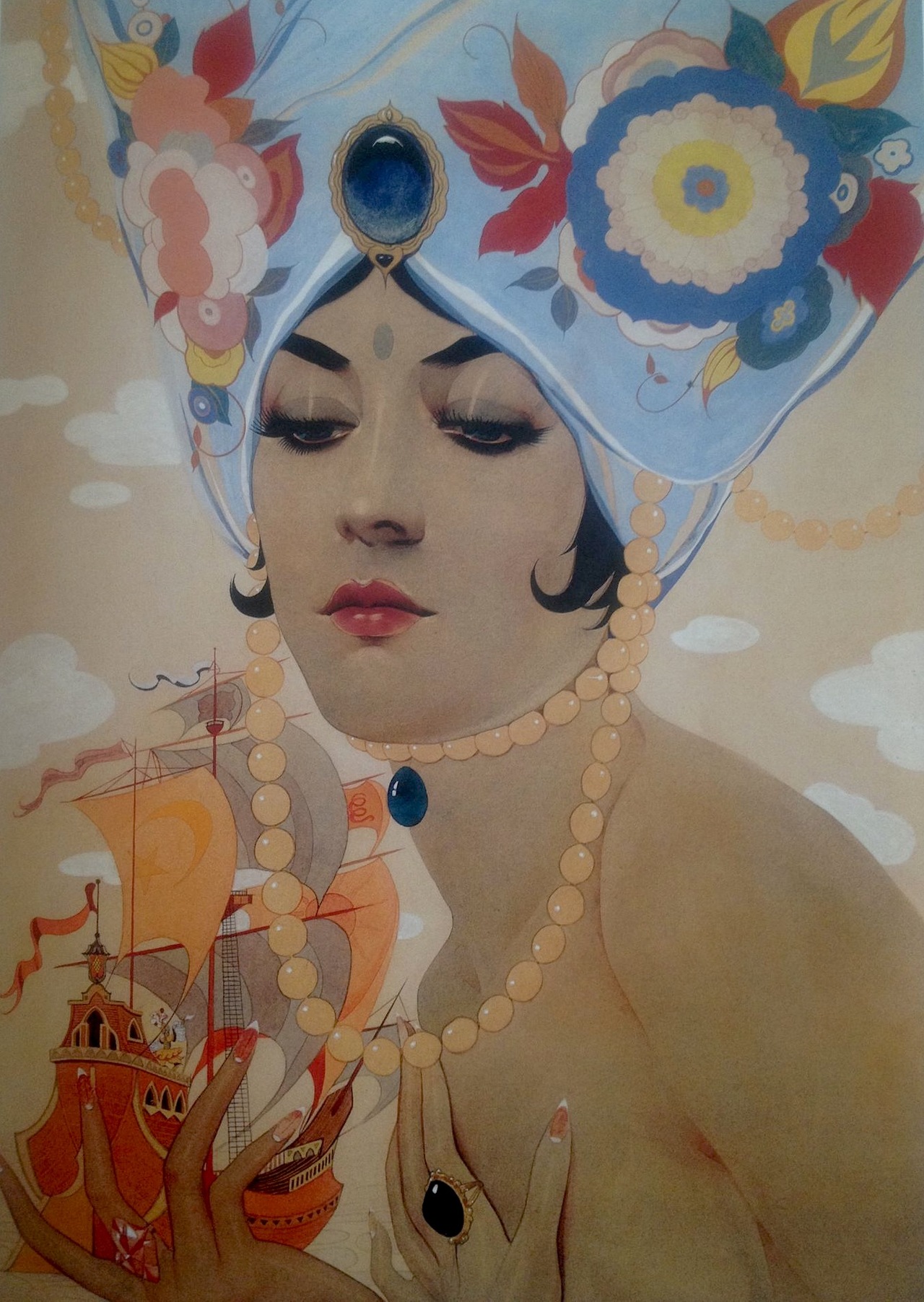

Scheherazade[edit]

Scheherazade in the palace of her husband, Shahryar

Scheherazade or Shahrazad (Persian: شهرزاد, Šahrzād, or شهرزاد, Šahrāzād, lit. ‘child of the city’)[1][2] is the legendary Persian queen who is the storyteller and narrator of The Nights. She is the daughter of the kingdom’s vizier and the older sister of Dunyazad.

Against her father’s wishes, she marries King Shahryar, who has vowed that he will execute a new bride every morning. For 1,001 nights, Scheherazade tells her husband a story, stopping at dawn with a cliffhanger. This forces the King to keep her alive for another day so that she could resume the tale at night.

The name derives from the Persian šahr (شهر, ‘city’) and -zâd (زاد, ‘child of’); or from the Middle-Persian čehrāzād, wherein čehr means ‘lineage’ and āzād, ‘noble’ or ‘exalted’ (i.e. ‘of noble or exalted lineage’ or ‘of noble appearance/origin’),[1][2]

Dunyazad[edit]

Dunyazad (Persian: دنیازاد, Dunyāzād; aka Dunyazade, Dunyazatde, Dinazade, or Dinarzad) is the younger sister of Queen Scheherazade. In the story cycle, it is she who—at Scheherazade’s instruction—initiates the tactic of cliffhanger storytelling to prevent her sister’s execution by Shahryar. Dunyazad, brought to her sister’s bedchamber so that she could say farewell before Scheherazade’s execution the next morning, asks her sister to tell one last story. At the successful conclusion of the tales, Dunyazad marries Shah Zaman, Shahryar’s younger brother.

She is recast as a major character as the narrator of the «Dunyazadiad» segment of John Barth’s novel Chimera.

Scheherazade’s father[edit]

Scheherazade’s father, sometimes called Jafar (Persian: جعفر; Arabic: جَعْفَر, jaʿfar), is the vizier of King Shahryar. Every day, on the king’s order, he beheads the brides of Shahryar. He does this for many years until all the unmarried women in the kingdom have either been killed or run away, at which point his own daughter Scheherazade offers to marry the king.

The vizier tells Scheherazade the Tale of the Bull and the Ass, in an attempt to discourage his daughter from marrying the king. It does not work, and she marries Shahryar anyway. At the end of the 1,001 nights, Scheherazade’s father goes to Samarkand where he replaces Shah Zaman as sultan.

The treacherous sorcerer in Disney’s Aladdin, Jafar, is named after this character.

Shahryar[edit]

Shahryar (Persian: شهریار, Šahryār; also spelt Shahriar, Shariar, Shahriyar, Schahryar, Sheharyar, Shaheryar, Shahrayar, Shaharyar, or Shahrear),[1] which is pronounced /Sha ree yaar/ in Persian, is the fictional Persian Sassanid King of kings who is told stories by his wife, Scheherazade. He ruled over a Persian Empire extended to India, over all the adjacent islands and a great way beyond the Ganges as far as China, while Shahryar’s younger brother, Shah Zaman ruled over Samarkand.

In the frame-story, Shahryar is betrayed by his wife, which makes him believe that all women will, in the end, betray him. So every night for three years, he takes a wife and has her executed the next morning, until he marries Scheherazade, his vizier’s beautiful and clever daughter. For 1,001 nights in a row, Scheherazade tells Shahryar a story, each time stopping at dawn with a cliffhanger, thus forcing him to keep her alive for another day so that she can complete the tale the next night. After 1,001 stories, Scheherazade tells Shahryar that she has no more stories for him. Fortunately, during the telling of the stories, Shahryar has grown into a wise ruler and rekindles his trust in women.

The word šahryâr (Persian: شهریار) derives from the Middle Persian šahr-dār, ‘holder of a kingdom’ (i.e. ‘lord, sovereign, king’).[1]

Shah Zaman[edit]

Shah Zaman or Schazzenan (Persian: شاهزمان, Šāhzamān) is the Sultan of Samarkand (aka Samarcande) and brother of Shahryar. Shah Zaman catches his first wife in bed with a cook and cuts them both in two. Then, while staying with his brother, he discovers that Shahryar’s wife is unfaithful. At this point, Shah Zaman comes to believe that all women are untrustworthy and he returns to Samarkand where, as his brother does, he marries a new bride every day and has her executed before morning.

At the end of the story, Shahryār calls for his brother and tells him of Scheherazade’s fascinating, moral tales. Shah Zaman decides to stay with his brother and marries Scheherazade’s beautiful younger maiden sister, Dunyazad, with whom he has fallen in love. He is the ruler of Tartary from its capital Samarkand.

Characters in Scheherazade’s stories[edit]

Ahmed[edit]

Prince Ahmed (Arabic: أحمد, ʾaḥmad, ‘thank, praise’) is the youngest of three sons of the Sultan of the Indies. He is noted for having a magic tent that would expand so as to shelter an army, and contract so that it could go into one’s pocket. Ahmed travels to Samarkand city and buys an apple that can cure any disease if the sick person smells it.

Ahmed rescues the Princess Paribanou (Persian: پریبانو, Parībānū; also spelled Paribanon or Peri Banu), a peri (female jinn).

Aladdin[edit]

Aladdin (Arabic: علاء الدين, ʿalāʾ ad-dīn) is one of the most famous characters from One Thousand and One Nights and appears in the famous tale of Aladdin and The Wonderful Lamp. Despite not being part of the original Arabic text of The Arabian Nights, the story of Aladdin is one of the best known tales associated with that collection, especially following the eponymous 1992 Disney film.[3]

Composed of the words ʿalāʾ (عَلَاء, ‘exaltation (of)’) and ad-dīn (الدِّين, ‘the religion’), the name Aladdin essentially means ‘nobility of the religion’.

Ali Baba[edit]

The Forty Thieves attack greedy Cassim when they find him in their secret magic cave.

Ali Baba (Arabic: علي بابا, ʿaliy bābā) is a poor wood cutter who becomes rich after discovering a vast cache of treasure, hidden by evil bandits.

Ali Shar[edit]

Ali Shar (Arabic: علي شار) is a character from Ali Shar and Zumurrud who inherits a large fortune on the death of his father but very quickly squanders it all. He goes hungry for many months until he sees Zumurrud on sale in a slave market. Zumurrud gives Ali the money to buy her and the two live together and fall in love. A year later Zumurrud is kidnapped by a Christian and Ali spends the rest of the story finding her.

Ali[edit]

Prince Ali (Arabic: علي, ʿalīy; Persian: علی) is a son of the Sultan of the Indies. He travels to Shiraz, the capital of Persia, and buys a magic perspective glass that can see for hundreds of miles.

Badroulbadour[edit]

Princess Badroulbadour (Arabic: الأميرة بدر البدور) is the only daughter of the Emperor of China in the folktale, Aladdin, and whom Aladdin falls in love with after seeing her in the city with a crowd of her attendants. Aladdin uses the genie of the lamp to foil the Princess’s arranged marriage to the Grand Vizier’s son, and marries her himself. The Princess is described as being somewhat spoiled and vain. Her name is often changed in many retellings to make it easier to pronounce.

The Barber of Baghdad[edit]

The Barber of Baghdad (Arabic: المزين البغدادي) is wrongly accused of smuggling and in order to save his life, he tells Caliph Mustensir Billah of his six brothers in order:

- Al-Bakbuk, who was a hunchback

- Al-Haddar (also known as Alnaschar), who was paralytic

- Al-Fakik, who was blind

- Al-Kuz, who lost one of his eyes

- Al-Nashshár, who was “cropped of both ears”

- Shakashik, who had a harelip

Cassim[edit]

Cassim (Arabic: قاسم, qāsim, ‘divider, distributor’) is the rich and greedy brother of Ali Baba who is killed by the Forty Thieves when he is caught stealing treasure from their magic cave.

Duban[edit]

Duban or Douban (Arabic: ذُؤْبَان, ḏuʾbān, ‘golden jackal’ or ‘wolves’), who appears in The Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban, is a man of extraordinary talent with the ability to read Arabic, Greek, Persian, Turkish, Byzantine, Syriac, Hebrew, and Sanskrit, as well as a deep understanding of botany, philosophy, and natural history to name a few.

Duban works his medicine in an unusual way: he creates a mallet and ball to match, filling the handle of the mallet with his medicine. With this, he cures King Yunan from leprosy; when the king plays with the ball and mallet, he perspires, thus absorbing the medicine through the sweat from his hand into his bloodstream. After a short bath and a sleep, the King is cured, and rewards Duban with wealth and royal honor.

The King’s vizier, however, becomes jealous of Duban, and persuades Yunan into believing that Duban will later produce a medicine to kill him. The king eventually decides to punish Duban for his alleged treachery, and summons him to be beheaded. After unsuccessfully pleading for his life, Duban offers one of his prized books to Yunan to impart the rest of his wisdom. Yunan agrees, and the next day, Duban is beheaded, and Yunan begins to open the book, finding that no printing exists on the paper. After paging through for a time, separating the stuck leaves each time by first wetting his finger in his mouth, he begins to feel ill. Yunan realises that the leaves of the book were poisoned, and as he dies, the king understands that this was his punishment for betraying the one that once saved his life.

Hussain[edit]

Prince Hussain (Arabic: الأمير حسين), the eldest son of the Sultan of the Indies, travels to Bisnagar (Vijayanagara) in India and buys a magic teleporting tapestry, also known as a magic carpet.

Maruf the Cobbler[edit]

Maruf (Arabic: معروف, maʿrūf, ‘known, recognized’) is a diligent and hardworking cobbler in the city of Cairo.

In the story, he is married to a mendacious and pestering woman named Fatimah. Due to the ensuing quarrel between him and his wife, Maruf flees Cairo and enters the ancient ruins of Adiliyah. There, he takes refuge from the winter rains. After sunset, he meets a very powerful Jinni, who then transports Maruf to a distant land known as Ikhtiyan al-Khatan.

Morgiana[edit]

Morgiana (Arabic: مرجانة, marjāna or murjāna, ‘small pearl’) is a clever slave girl from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

She is initially in Cassim’s household but on his death she joins his brother, Ali Baba, and through her quick-wittedness she saves Ali’s life many times, eventually killing his worst enemy, the leader of the Forty Thieves. Afterward, Ali Baba marries his son with her.

Sinbad the Porter and Sinbad the Sailor[edit]

Sinbad the Porter (Arabic: السندباد الحمال) is a poor man who one day pauses to rest on a bench outside the gate of a rich merchant’s house in Baghdad. The owner of the house is Sinbad the Sailor, who hears the porter’s lament and sends for him. Amused by the fact that they share a name, Sinbad the Sailor relates the tales of his seven wondrous voyages to his namesake.[4]

Sinbad the Sailor (Arabic: السندباد البحري; or As-Sindibād) is perhaps one of the most famous characters from the Arabian Nights. He is from Basra, but in his old age, he lives in Baghdad. He recounts the tales of his seven voyages to Sinbad the Porter.

Sinbad (Persian: سنباد, sambâd) is sometimes spelled as Sindbad, from the Arabic sindibād (سِنْدِبَاد).

Sultan of the Indies[edit]

Sultan of the Indies (Arabic: سلطان جزر الهند) has three sons—Hussain, Ali and Ahmed—all of whom wish to marry their cousin Princess Nouronnihar (Arabic: الأميرة نور النهار). To his sons, the Sultan says he will give her to the prince who brings back the most extraordinary rare object.

Yunan[edit]

King Yunan (Arabic: الملك يونان, al-malik Yunān, lit. ‘Yunanistan [Greece]’), or King Greece, is a fictional king of one of the ancient Persian cities in the province of Zuman, who appears in The Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban.

Suffering from leprosy at the beginning of the story, Yunan is cured by Duban, the physician whom he rewards greatly. Jealous of Duban’s praises, Yunan’s vizier becomes jealous and persuades the King that Duban wants to overthrow him. At first, Yunan does not believe this and tells his vizier the Tale of the Husband and the Parrot, to which the vizier responds by telling the Tale of the Prince and the Ogress. This convinces Yunan that Duban is guilty, having him executed. Yunan later dies after reading a book of Duban’s, the pages of which had been poisoned.

Zayn Al-Asnam[edit]

Prince Zayn Al-Asnam or Zeyn Alasnam (Arabic: زين الأصنام, zayn al-aṣnām), son of the Sultan of Basra (or Bassorah), is the eponymous character in The Tale of Zayn Al-Asnam.

After his father’s death, al-Asnam wastes his inheritance and neglects his duties, until the people revolt and he narrowly escapes death. In a dream, a sheikh tells the Prince to go to Egypt. A second dream tells him to go home, directing him to a hidden chamber in the palace, where he finds 8 statues made of gold (or diamond). He also finds a key and a message telling him to visit Mubarak, a slave in Cairo. Mubarak takes the Prince to a paradise island, where he meets the King of the Jinns.

The King gives Zayn a mirror, called the touchstone of virtue, which, upon looking into it, would inform Zayn whether a damsel was pure/faithful or not. If the mirror remained unsullied, so was the maiden; if it clouded, the maiden had been unfaithful. The King tells Zayn that he will give him the 9th statue that he is looking for in return for a beautiful 15-year-old virgin. Zayn finds the daughter of the vizier of Baghdad, but marries her himself, making her no longer a virgin. The King, however, forgives Zayn’s broken promise, as the young lady herself is revealed to be the ninth statue promised to Zayn by the King. The jinn bestows the Prince with the young bride on the sole condition that Zayn remains loving and faithful to her and her only.[5]

The Prince’s name comes from Arabic zayn (زين), meaning ‘beautiful, pretty’, and aṣnām (أصنام), meaning ‘idols’.

Zumurrud[edit]

Zumurrud the Smaragdine (Persian: زمرد سمرقندی, Zumurrud-i Samarqandi, ’emerald of Samarkand’) is a slave girl who appears in Ali Shar and Zumurrud. She is named after Samarkand, the city well known at the time of the story for its emeralds.

She is bought by, and falls in love with, Ali Shar with whom she lives until she is kidnapped by a Christian. Zumurrud escapes from the Christian only to be found and taken by Javan (Juvenile) the Kurd. Again, Zumurrud manages to get away from her captor, this time by dressing up as a man. On her way back to Ali Shar, Zumurrud is mistaken for a noble Turk and made Queen of an entire kingdom. Eventually, Zumurrud is reunited with Ali Shar.

Real people[edit]

| Person | Description | Appears in |

|---|---|---|

| Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali

(Arabic: أبو الأسود الدؤلي) |

an Arab linguist, a companion of Ali bin Abu Talib, and the father of Arabic grammar. | Abu al-Aswad and His Slave-girl |

| Abu Nuwas

(Arabic: أبو نواس) |

a renowned, hedonistic poet at the court of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. | several tales |

| Abu Yusuf

(Arabic: أبو يوسف) |

a famous legal scholar and judge during the reign of Harun al-Rashid. Abu Yusuf was also one of the founders of the Hanafi school of islamic law. |

|

| Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

(Arabic: عبد الملك ابن مروان) |

the most celebrated Umayyad Caliph, ruling from 685 to 705, and a frequent character in The Nights |

|

| Adi ibn Zayd

(Arabic: عدي بن زيد) |

a 6th-century Arab Christian poet from al-Hirah | ‘Adî ibn Zayd and the Princess Hind |

| Al-Amin

(Arabic: الأمين) |

the sixth Abbasid Caliph. He succeeded his father, Harun al-Rashid, in 809, ruling until he was deposed and killed in 813 during the civil war with his half-brother, al-Ma’mun. |

|

| Al-Asmaʿi

(Arabic: الأصمعي) |

a celebrated Arabic grammarian and a scholar of poetry at the court of the Hārūn al-Rashīd. | Al-Asma‘î and the Girls of Basra (in which Al-Asmaʿi tells a story about himself during the 216th night) |

| Al-Hadi

(Arabic: الهادي) |

the fourth Abbasid caliph who succeeded his father Al-Mahdi and ruled from 785 until his death in 786 AD. |

|

| Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah

(Arabic: الحاكم بأمر الله) |

the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili imam (996–1021). | The Caliph Al-Hâkim and the Merchant |

| Al-Ma’mun

(Arabic: المأمون) |

the seventh Abbasid caliph, reigning from 813 until his death in 833. He succeeded his half-brother al-Amin after a civil war. Al-Ma’mun is one of the most frequently mentioned characters in the nights. |

|

| Al-Mahdi

(Arabic: المهدي) |

the third Abbasid Caliph, reigning from 775 to his death in 785. He succeeded his father, al-Mansur. |

|

| Al-Mu’tadid

(Arabic: المعتضد بالله) |

the Abbasid Caliph from 892 until his death in 902. |

|

| Al-Mutawakkil

(Arabic: المتوكل على الله) |

an Abbasid caliph who reigned in Samarra from 847 until 861. |

|

| Mustensir Billah (or Al-Mustansir)

(Arabic: المستنصر بالله) |

the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad from 1226 to 1242. | (The Barber of Baghdad tells Mustensir stories of his six brothers) |

| Al-Mustazi

(aka Az-Zahir) |

the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad from 1225 to 1226. | The Hunchback’s Tale |

| Al-Walid II

(Arabic: الوليد بن يزيد) |

an Umayyad Caliph, ruling from 743 until his assassination in the year 744. | Yûnus the Scribe and Walîd ibn Sahl (appears spuriously) |

| Baibars

(Arabic: الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس) |

the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and the real founder of the Bahri dynasty. He was one of the commanders of the Egyptian forces that inflicted a defeat on the Seventh Crusade. He also led the vanguard of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

In The Nights, Baibars is the main protagonist of The Adventures of Sultan Baybars, a romance focusing on his life; he also features as a main character in Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari and the Sixteen Captains of Police, the frame story of one cycle. |

|

| David IV of Georgia

(appears as ‘Sword of the Messiah’) |

Portrayed as having a cross carved onto his face. Sharkan kills him in this story, weakening the Christian army. | story of Sharkan |

| Harun al-Rashid

(Arabic: هارون الرشيد) |

fifth Abbasid Caliph, ruling from 786 until 809. The wise Caliph serves as an important character in many of the stories set in Baghdad, frequently in connection with his vizier, Ja’far, with whom he roams in disguise through the streets of the city to observe the lives of the ordinary people. | several tales |

| Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik

(Arabic: هشام ابن عبد الملك) |

the 10th Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until 743. |

|

| Ibrahim al-Mawsili

(Arabic: إبراهيم الموصلي) |

a Persian singer and Arabic-language poet, appearing in several stories |

|

| Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi

(Arabic: إبراهيم بن المهدي) |

an Abbasid prince, singer, composer, and poet, featuring in several tales. |

|

| Ishaq al-Mawsili

(Arabic: إسحاق الموصلي) |

a Persian musician and a boon companion in the Abbasid court at the time of Harun al-Rashid. Ishaq appears in several tales. |

|

| Ja’far ibn Yahya

(Arabic: جعفر البرمكي) (aka Ja’far or Ja’afar the Barmecide) |

Harun al-Rashid’s Persian vizier who appears in many stories, normally accompanying Harun. In at least one of these stories, The Three Apples, Ja’far is the protagonist, depicted in a role similar to a detective. In another story, The Tale of Attaf, he is also a protagonist, depicted as an adventurer alongside the protagonist Attaf. |

|

|

Khusrau Parviz (New Persian: خسرو پرویز; Arabic: كسرى الثاني) (aka Khosrow II, Kisra the Second) |

the King of Persia from 590 to 628. He appears in a story with his wife, Shirin on the 391st night. | Khusrau and Shirin and the Fisherman (391st night) |

| Ma’n ibn Za’ida (Arabic: معن بن زائدة) | an 8th-century Arab general of the Shayban tribe, who served both the Umayyads and the Abbasids. He acquired a legendary reputation as a fierce warrior and also for his extreme generosity. Ma’n appears as a main character in four tales in The Arabian Nights. |

|

| Moses | the Biblical prophet appears in one story recited on the 82nd night by one of the girls trained by Dahat al-Dawahi in order to infiltrate the Sultan’s court. In the story, Moses helps the daughter of Shu’aib fill her jar of water. Shu’aib tells them to fetch Moses to thank him but Moses must avert his eyes from the woman’s exposed buttocks, showing his mastery of his sexual urges. | story on the 82nd night |

| Muawiyah I

(Arabic: معاوية بن أبي سفيان) |

the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate. |

|

| Roderic | the Visigothic King appears in a story recited on the 272nd and 273rd night. In the story, he opens a mysterious door in his castle that was locked and sealed shut by the previous kings. He discovers paintings of Muslim soldiers in the room and a note saying that the city of Toledo will fall to the soldiers in the paintings if the room is ever opened. This coincides with the fall of Toledo in 711. | story on the 272nd and 273rd night |

| Shirin

(Persian: شيرين, Šīrīn) |

the wife of Sassanid King Khosrow II (Khusrau), with whom she appears in a story on the 391st night. | Khusrau and Shirin and the Fisherman (391st night) |

| Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik

(Arabic: سليمان ابن عبد الملك) |

the seventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 715 until 717. | Khuzaymaibn Bishr and ‘Ikrima al-Fayyâd |

See also[edit]

- List of stories within One Thousand and One Nights

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ch. Pellat (2011). «ALF LAYLA WA LAYLA». Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b Hamori, A. (2012). «S̲h̲ahrazād». In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6771.

- ^ Razzaque, Arafat A. 10 August 2017. «Who wrote Aladdin?» Ajam Media Collective.

- ^ «Sindbad the Seaman and Sindbad the Landsman — The Arabian Nights — The Thousand and One Nights — Sir Richard Burton translator». Classiclit.about.com. 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Burton, Richard F. «When it was the Five Hundred and Thirteenth Night,.» Supplemental Nights To The Book Of The Thousand And One Nights With Notes Anthropological And Explanatory, vol. 3. The Burton Club.

External links[edit]

- The Thousand Nights and a Night in several classic translations, including unexpurgated version by Sir Richard Francis Burton, and John Payne translation, with additional material.

- Stories From One Thousand and One Nights, (Lane and Poole translation): Project Bartleby edition

- The Arabian Nights (includes Lang and (expurgated) Burton translations): Electronic Literature Foundation editions

- Jonathan Scott translation of Arabian Nights

- Notes on the influences and context of the Thousand and One Nights

- The Book of the Thousand and One Nights by John Crocker

- (expurgated) Sir Burton’s c.1885 translation, annotated for English study.

- The Arabian Nights by Andrew Lang at Project Gutenberg

- 1001 Nights, Representative of eastern literature (in Persian)

- «The Thousand-And-Second Tale of Scheherazade» by Edgar Allan Poe (Wikisource)

- Arabian Nights Six full-color plates of illustrations from the 1001 Nights which are in the public domain

- (in Arabic) The Tales in Arabic on Wikisource

Prince Ahmed and The Fairy. A poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon from Forget Me Not, 1826.

This is a list of characters in One Thousand and One Nights (aka The Arabian Nights), the classic, medieval collection of Middle-Eastern folk tales.

Characters in the frame story[edit]

Scheherazade[edit]

Scheherazade in the palace of her husband, Shahryar

Scheherazade or Shahrazad (Persian: شهرزاد, Šahrzād, or شهرزاد, Šahrāzād, lit. ‘child of the city’)[1][2] is the legendary Persian queen who is the storyteller and narrator of The Nights. She is the daughter of the kingdom’s vizier and the older sister of Dunyazad.

Against her father’s wishes, she marries King Shahryar, who has vowed that he will execute a new bride every morning. For 1,001 nights, Scheherazade tells her husband a story, stopping at dawn with a cliffhanger. This forces the King to keep her alive for another day so that she could resume the tale at night.

The name derives from the Persian šahr (شهر, ‘city’) and -zâd (زاد, ‘child of’); or from the Middle-Persian čehrāzād, wherein čehr means ‘lineage’ and āzād, ‘noble’ or ‘exalted’ (i.e. ‘of noble or exalted lineage’ or ‘of noble appearance/origin’),[1][2]

Dunyazad[edit]

Dunyazad (Persian: دنیازاد, Dunyāzād; aka Dunyazade, Dunyazatde, Dinazade, or Dinarzad) is the younger sister of Queen Scheherazade. In the story cycle, it is she who—at Scheherazade’s instruction—initiates the tactic of cliffhanger storytelling to prevent her sister’s execution by Shahryar. Dunyazad, brought to her sister’s bedchamber so that she could say farewell before Scheherazade’s execution the next morning, asks her sister to tell one last story. At the successful conclusion of the tales, Dunyazad marries Shah Zaman, Shahryar’s younger brother.

She is recast as a major character as the narrator of the «Dunyazadiad» segment of John Barth’s novel Chimera.

Scheherazade’s father[edit]

Scheherazade’s father, sometimes called Jafar (Persian: جعفر; Arabic: جَعْفَر, jaʿfar), is the vizier of King Shahryar. Every day, on the king’s order, he beheads the brides of Shahryar. He does this for many years until all the unmarried women in the kingdom have either been killed or run away, at which point his own daughter Scheherazade offers to marry the king.

The vizier tells Scheherazade the Tale of the Bull and the Ass, in an attempt to discourage his daughter from marrying the king. It does not work, and she marries Shahryar anyway. At the end of the 1,001 nights, Scheherazade’s father goes to Samarkand where he replaces Shah Zaman as sultan.

The treacherous sorcerer in Disney’s Aladdin, Jafar, is named after this character.

Shahryar[edit]

Shahryar (Persian: شهریار, Šahryār; also spelt Shahriar, Shariar, Shahriyar, Schahryar, Sheharyar, Shaheryar, Shahrayar, Shaharyar, or Shahrear),[1] which is pronounced /Sha ree yaar/ in Persian, is the fictional Persian Sassanid King of kings who is told stories by his wife, Scheherazade. He ruled over a Persian Empire extended to India, over all the adjacent islands and a great way beyond the Ganges as far as China, while Shahryar’s younger brother, Shah Zaman ruled over Samarkand.

In the frame-story, Shahryar is betrayed by his wife, which makes him believe that all women will, in the end, betray him. So every night for three years, he takes a wife and has her executed the next morning, until he marries Scheherazade, his vizier’s beautiful and clever daughter. For 1,001 nights in a row, Scheherazade tells Shahryar a story, each time stopping at dawn with a cliffhanger, thus forcing him to keep her alive for another day so that she can complete the tale the next night. After 1,001 stories, Scheherazade tells Shahryar that she has no more stories for him. Fortunately, during the telling of the stories, Shahryar has grown into a wise ruler and rekindles his trust in women.

The word šahryâr (Persian: شهریار) derives from the Middle Persian šahr-dār, ‘holder of a kingdom’ (i.e. ‘lord, sovereign, king’).[1]

Shah Zaman[edit]

Shah Zaman or Schazzenan (Persian: شاهزمان, Šāhzamān) is the Sultan of Samarkand (aka Samarcande) and brother of Shahryar. Shah Zaman catches his first wife in bed with a cook and cuts them both in two. Then, while staying with his brother, he discovers that Shahryar’s wife is unfaithful. At this point, Shah Zaman comes to believe that all women are untrustworthy and he returns to Samarkand where, as his brother does, he marries a new bride every day and has her executed before morning.

At the end of the story, Shahryār calls for his brother and tells him of Scheherazade’s fascinating, moral tales. Shah Zaman decides to stay with his brother and marries Scheherazade’s beautiful younger maiden sister, Dunyazad, with whom he has fallen in love. He is the ruler of Tartary from its capital Samarkand.

Characters in Scheherazade’s stories[edit]

Ahmed[edit]

Prince Ahmed (Arabic: أحمد, ʾaḥmad, ‘thank, praise’) is the youngest of three sons of the Sultan of the Indies. He is noted for having a magic tent that would expand so as to shelter an army, and contract so that it could go into one’s pocket. Ahmed travels to Samarkand city and buys an apple that can cure any disease if the sick person smells it.

Ahmed rescues the Princess Paribanou (Persian: پریبانو, Parībānū; also spelled Paribanon or Peri Banu), a peri (female jinn).

Aladdin[edit]

Aladdin (Arabic: علاء الدين, ʿalāʾ ad-dīn) is one of the most famous characters from One Thousand and One Nights and appears in the famous tale of Aladdin and The Wonderful Lamp. Despite not being part of the original Arabic text of The Arabian Nights, the story of Aladdin is one of the best known tales associated with that collection, especially following the eponymous 1992 Disney film.[3]

Composed of the words ʿalāʾ (عَلَاء, ‘exaltation (of)’) and ad-dīn (الدِّين, ‘the religion’), the name Aladdin essentially means ‘nobility of the religion’.

Ali Baba[edit]

The Forty Thieves attack greedy Cassim when they find him in their secret magic cave.

Ali Baba (Arabic: علي بابا, ʿaliy bābā) is a poor wood cutter who becomes rich after discovering a vast cache of treasure, hidden by evil bandits.

Ali Shar[edit]

Ali Shar (Arabic: علي شار) is a character from Ali Shar and Zumurrud who inherits a large fortune on the death of his father but very quickly squanders it all. He goes hungry for many months until he sees Zumurrud on sale in a slave market. Zumurrud gives Ali the money to buy her and the two live together and fall in love. A year later Zumurrud is kidnapped by a Christian and Ali spends the rest of the story finding her.

Ali[edit]

Prince Ali (Arabic: علي, ʿalīy; Persian: علی) is a son of the Sultan of the Indies. He travels to Shiraz, the capital of Persia, and buys a magic perspective glass that can see for hundreds of miles.

Badroulbadour[edit]

Princess Badroulbadour (Arabic: الأميرة بدر البدور) is the only daughter of the Emperor of China in the folktale, Aladdin, and whom Aladdin falls in love with after seeing her in the city with a crowd of her attendants. Aladdin uses the genie of the lamp to foil the Princess’s arranged marriage to the Grand Vizier’s son, and marries her himself. The Princess is described as being somewhat spoiled and vain. Her name is often changed in many retellings to make it easier to pronounce.

The Barber of Baghdad[edit]

The Barber of Baghdad (Arabic: المزين البغدادي) is wrongly accused of smuggling and in order to save his life, he tells Caliph Mustensir Billah of his six brothers in order:

- Al-Bakbuk, who was a hunchback

- Al-Haddar (also known as Alnaschar), who was paralytic

- Al-Fakik, who was blind

- Al-Kuz, who lost one of his eyes

- Al-Nashshár, who was “cropped of both ears”

- Shakashik, who had a harelip

Cassim[edit]

Cassim (Arabic: قاسم, qāsim, ‘divider, distributor’) is the rich and greedy brother of Ali Baba who is killed by the Forty Thieves when he is caught stealing treasure from their magic cave.

Duban[edit]

Duban or Douban (Arabic: ذُؤْبَان, ḏuʾbān, ‘golden jackal’ or ‘wolves’), who appears in The Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban, is a man of extraordinary talent with the ability to read Arabic, Greek, Persian, Turkish, Byzantine, Syriac, Hebrew, and Sanskrit, as well as a deep understanding of botany, philosophy, and natural history to name a few.

Duban works his medicine in an unusual way: he creates a mallet and ball to match, filling the handle of the mallet with his medicine. With this, he cures King Yunan from leprosy; when the king plays with the ball and mallet, he perspires, thus absorbing the medicine through the sweat from his hand into his bloodstream. After a short bath and a sleep, the King is cured, and rewards Duban with wealth and royal honor.

The King’s vizier, however, becomes jealous of Duban, and persuades Yunan into believing that Duban will later produce a medicine to kill him. The king eventually decides to punish Duban for his alleged treachery, and summons him to be beheaded. After unsuccessfully pleading for his life, Duban offers one of his prized books to Yunan to impart the rest of his wisdom. Yunan agrees, and the next day, Duban is beheaded, and Yunan begins to open the book, finding that no printing exists on the paper. After paging through for a time, separating the stuck leaves each time by first wetting his finger in his mouth, he begins to feel ill. Yunan realises that the leaves of the book were poisoned, and as he dies, the king understands that this was his punishment for betraying the one that once saved his life.

Hussain[edit]

Prince Hussain (Arabic: الأمير حسين), the eldest son of the Sultan of the Indies, travels to Bisnagar (Vijayanagara) in India and buys a magic teleporting tapestry, also known as a magic carpet.

Maruf the Cobbler[edit]

Maruf (Arabic: معروف, maʿrūf, ‘known, recognized’) is a diligent and hardworking cobbler in the city of Cairo.

In the story, he is married to a mendacious and pestering woman named Fatimah. Due to the ensuing quarrel between him and his wife, Maruf flees Cairo and enters the ancient ruins of Adiliyah. There, he takes refuge from the winter rains. After sunset, he meets a very powerful Jinni, who then transports Maruf to a distant land known as Ikhtiyan al-Khatan.

Morgiana[edit]

Morgiana (Arabic: مرجانة, marjāna or murjāna, ‘small pearl’) is a clever slave girl from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

She is initially in Cassim’s household but on his death she joins his brother, Ali Baba, and through her quick-wittedness she saves Ali’s life many times, eventually killing his worst enemy, the leader of the Forty Thieves. Afterward, Ali Baba marries his son with her.

Sinbad the Porter and Sinbad the Sailor[edit]

Sinbad the Porter (Arabic: السندباد الحمال) is a poor man who one day pauses to rest on a bench outside the gate of a rich merchant’s house in Baghdad. The owner of the house is Sinbad the Sailor, who hears the porter’s lament and sends for him. Amused by the fact that they share a name, Sinbad the Sailor relates the tales of his seven wondrous voyages to his namesake.[4]

Sinbad the Sailor (Arabic: السندباد البحري; or As-Sindibād) is perhaps one of the most famous characters from the Arabian Nights. He is from Basra, but in his old age, he lives in Baghdad. He recounts the tales of his seven voyages to Sinbad the Porter.

Sinbad (Persian: سنباد, sambâd) is sometimes spelled as Sindbad, from the Arabic sindibād (سِنْدِبَاد).

Sultan of the Indies[edit]

Sultan of the Indies (Arabic: سلطان جزر الهند) has three sons—Hussain, Ali and Ahmed—all of whom wish to marry their cousin Princess Nouronnihar (Arabic: الأميرة نور النهار). To his sons, the Sultan says he will give her to the prince who brings back the most extraordinary rare object.

Yunan[edit]

King Yunan (Arabic: الملك يونان, al-malik Yunān, lit. ‘Yunanistan [Greece]’), or King Greece, is a fictional king of one of the ancient Persian cities in the province of Zuman, who appears in The Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban.

Suffering from leprosy at the beginning of the story, Yunan is cured by Duban, the physician whom he rewards greatly. Jealous of Duban’s praises, Yunan’s vizier becomes jealous and persuades the King that Duban wants to overthrow him. At first, Yunan does not believe this and tells his vizier the Tale of the Husband and the Parrot, to which the vizier responds by telling the Tale of the Prince and the Ogress. This convinces Yunan that Duban is guilty, having him executed. Yunan later dies after reading a book of Duban’s, the pages of which had been poisoned.

Zayn Al-Asnam[edit]

Prince Zayn Al-Asnam or Zeyn Alasnam (Arabic: زين الأصنام, zayn al-aṣnām), son of the Sultan of Basra (or Bassorah), is the eponymous character in The Tale of Zayn Al-Asnam.

After his father’s death, al-Asnam wastes his inheritance and neglects his duties, until the people revolt and he narrowly escapes death. In a dream, a sheikh tells the Prince to go to Egypt. A second dream tells him to go home, directing him to a hidden chamber in the palace, where he finds 8 statues made of gold (or diamond). He also finds a key and a message telling him to visit Mubarak, a slave in Cairo. Mubarak takes the Prince to a paradise island, where he meets the King of the Jinns.

The King gives Zayn a mirror, called the touchstone of virtue, which, upon looking into it, would inform Zayn whether a damsel was pure/faithful or not. If the mirror remained unsullied, so was the maiden; if it clouded, the maiden had been unfaithful. The King tells Zayn that he will give him the 9th statue that he is looking for in return for a beautiful 15-year-old virgin. Zayn finds the daughter of the vizier of Baghdad, but marries her himself, making her no longer a virgin. The King, however, forgives Zayn’s broken promise, as the young lady herself is revealed to be the ninth statue promised to Zayn by the King. The jinn bestows the Prince with the young bride on the sole condition that Zayn remains loving and faithful to her and her only.[5]

The Prince’s name comes from Arabic zayn (زين), meaning ‘beautiful, pretty’, and aṣnām (أصنام), meaning ‘idols’.

Zumurrud[edit]

Zumurrud the Smaragdine (Persian: زمرد سمرقندی, Zumurrud-i Samarqandi, ’emerald of Samarkand’) is a slave girl who appears in Ali Shar and Zumurrud. She is named after Samarkand, the city well known at the time of the story for its emeralds.

She is bought by, and falls in love with, Ali Shar with whom she lives until she is kidnapped by a Christian. Zumurrud escapes from the Christian only to be found and taken by Javan (Juvenile) the Kurd. Again, Zumurrud manages to get away from her captor, this time by dressing up as a man. On her way back to Ali Shar, Zumurrud is mistaken for a noble Turk and made Queen of an entire kingdom. Eventually, Zumurrud is reunited with Ali Shar.

Real people[edit]

| Person | Description | Appears in |

|---|---|---|

| Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali

(Arabic: أبو الأسود الدؤلي) |

an Arab linguist, a companion of Ali bin Abu Talib, and the father of Arabic grammar. | Abu al-Aswad and His Slave-girl |

| Abu Nuwas

(Arabic: أبو نواس) |

a renowned, hedonistic poet at the court of the Caliph Harun al-Rashid. | several tales |

| Abu Yusuf

(Arabic: أبو يوسف) |

a famous legal scholar and judge during the reign of Harun al-Rashid. Abu Yusuf was also one of the founders of the Hanafi school of islamic law. |

|

| Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

(Arabic: عبد الملك ابن مروان) |

the most celebrated Umayyad Caliph, ruling from 685 to 705, and a frequent character in The Nights |

|

| Adi ibn Zayd

(Arabic: عدي بن زيد) |

a 6th-century Arab Christian poet from al-Hirah | ‘Adî ibn Zayd and the Princess Hind |

| Al-Amin

(Arabic: الأمين) |

the sixth Abbasid Caliph. He succeeded his father, Harun al-Rashid, in 809, ruling until he was deposed and killed in 813 during the civil war with his half-brother, al-Ma’mun. |

|

| Al-Asmaʿi

(Arabic: الأصمعي) |

a celebrated Arabic grammarian and a scholar of poetry at the court of the Hārūn al-Rashīd. | Al-Asma‘î and the Girls of Basra (in which Al-Asmaʿi tells a story about himself during the 216th night) |

| Al-Hadi

(Arabic: الهادي) |

the fourth Abbasid caliph who succeeded his father Al-Mahdi and ruled from 785 until his death in 786 AD. |

|

| Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah

(Arabic: الحاكم بأمر الله) |

the sixth Fatimid caliph and 16th Ismaili imam (996–1021). | The Caliph Al-Hâkim and the Merchant |

| Al-Ma’mun

(Arabic: المأمون) |

the seventh Abbasid caliph, reigning from 813 until his death in 833. He succeeded his half-brother al-Amin after a civil war. Al-Ma’mun is one of the most frequently mentioned characters in the nights. |

|

| Al-Mahdi

(Arabic: المهدي) |

the third Abbasid Caliph, reigning from 775 to his death in 785. He succeeded his father, al-Mansur. |

|

| Al-Mu’tadid

(Arabic: المعتضد بالله) |

the Abbasid Caliph from 892 until his death in 902. |

|

| Al-Mutawakkil

(Arabic: المتوكل على الله) |

an Abbasid caliph who reigned in Samarra from 847 until 861. |

|

| Mustensir Billah (or Al-Mustansir)

(Arabic: المستنصر بالله) |

the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad from 1226 to 1242. | (The Barber of Baghdad tells Mustensir stories of his six brothers) |

| Al-Mustazi

(aka Az-Zahir) |

the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad from 1225 to 1226. | The Hunchback’s Tale |

| Al-Walid II

(Arabic: الوليد بن يزيد) |

an Umayyad Caliph, ruling from 743 until his assassination in the year 744. | Yûnus the Scribe and Walîd ibn Sahl (appears spuriously) |

| Baibars

(Arabic: الملك الظاهر ركن الدين بيبرس) |

the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and the real founder of the Bahri dynasty. He was one of the commanders of the Egyptian forces that inflicted a defeat on the Seventh Crusade. He also led the vanguard of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

In The Nights, Baibars is the main protagonist of The Adventures of Sultan Baybars, a romance focusing on his life; he also features as a main character in Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari and the Sixteen Captains of Police, the frame story of one cycle. |

|

| David IV of Georgia

(appears as ‘Sword of the Messiah’) |

Portrayed as having a cross carved onto his face. Sharkan kills him in this story, weakening the Christian army. | story of Sharkan |

| Harun al-Rashid

(Arabic: هارون الرشيد) |

fifth Abbasid Caliph, ruling from 786 until 809. The wise Caliph serves as an important character in many of the stories set in Baghdad, frequently in connection with his vizier, Ja’far, with whom he roams in disguise through the streets of the city to observe the lives of the ordinary people. | several tales |

| Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik

(Arabic: هشام ابن عبد الملك) |

the 10th Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until 743. |

|

| Ibrahim al-Mawsili

(Arabic: إبراهيم الموصلي) |

a Persian singer and Arabic-language poet, appearing in several stories |

|

| Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi

(Arabic: إبراهيم بن المهدي) |

an Abbasid prince, singer, composer, and poet, featuring in several tales. |

|

| Ishaq al-Mawsili

(Arabic: إسحاق الموصلي) |

a Persian musician and a boon companion in the Abbasid court at the time of Harun al-Rashid. Ishaq appears in several tales. |

|

| Ja’far ibn Yahya

(Arabic: جعفر البرمكي) (aka Ja’far or Ja’afar the Barmecide) |

Harun al-Rashid’s Persian vizier who appears in many stories, normally accompanying Harun. In at least one of these stories, The Three Apples, Ja’far is the protagonist, depicted in a role similar to a detective. In another story, The Tale of Attaf, he is also a protagonist, depicted as an adventurer alongside the protagonist Attaf. |

|

|

Khusrau Parviz (New Persian: خسرو پرویز; Arabic: كسرى الثاني) (aka Khosrow II, Kisra the Second) |

the King of Persia from 590 to 628. He appears in a story with his wife, Shirin on the 391st night. | Khusrau and Shirin and the Fisherman (391st night) |

| Ma’n ibn Za’ida (Arabic: معن بن زائدة) | an 8th-century Arab general of the Shayban tribe, who served both the Umayyads and the Abbasids. He acquired a legendary reputation as a fierce warrior and also for his extreme generosity. Ma’n appears as a main character in four tales in The Arabian Nights. |

|

| Moses | the Biblical prophet appears in one story recited on the 82nd night by one of the girls trained by Dahat al-Dawahi in order to infiltrate the Sultan’s court. In the story, Moses helps the daughter of Shu’aib fill her jar of water. Shu’aib tells them to fetch Moses to thank him but Moses must avert his eyes from the woman’s exposed buttocks, showing his mastery of his sexual urges. | story on the 82nd night |

| Muawiyah I

(Arabic: معاوية بن أبي سفيان) |

the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate. |

|

| Roderic | the Visigothic King appears in a story recited on the 272nd and 273rd night. In the story, he opens a mysterious door in his castle that was locked and sealed shut by the previous kings. He discovers paintings of Muslim soldiers in the room and a note saying that the city of Toledo will fall to the soldiers in the paintings if the room is ever opened. This coincides with the fall of Toledo in 711. | story on the 272nd and 273rd night |

| Shirin

(Persian: شيرين, Šīrīn) |

the wife of Sassanid King Khosrow II (Khusrau), with whom she appears in a story on the 391st night. | Khusrau and Shirin and the Fisherman (391st night) |

| Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik

(Arabic: سليمان ابن عبد الملك) |

the seventh Umayyad caliph, ruling from 715 until 717. | Khuzaymaibn Bishr and ‘Ikrima al-Fayyâd |

See also[edit]

- List of stories within One Thousand and One Nights

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Ch. Pellat (2011). «ALF LAYLA WA LAYLA». Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b Hamori, A. (2012). «S̲h̲ahrazād». In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6771.

- ^ Razzaque, Arafat A. 10 August 2017. «Who wrote Aladdin?» Ajam Media Collective.

- ^ «Sindbad the Seaman and Sindbad the Landsman — The Arabian Nights — The Thousand and One Nights — Sir Richard Burton translator». Classiclit.about.com. 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Burton, Richard F. «When it was the Five Hundred and Thirteenth Night,.» Supplemental Nights To The Book Of The Thousand And One Nights With Notes Anthropological And Explanatory, vol. 3. The Burton Club.

External links[edit]

- The Thousand Nights and a Night in several classic translations, including unexpurgated version by Sir Richard Francis Burton, and John Payne translation, with additional material.

- Stories From One Thousand and One Nights, (Lane and Poole translation): Project Bartleby edition

- The Arabian Nights (includes Lang and (expurgated) Burton translations): Electronic Literature Foundation editions

- Jonathan Scott translation of Arabian Nights

- Notes on the influences and context of the Thousand and One Nights

- The Book of the Thousand and One Nights by John Crocker

- (expurgated) Sir Burton’s c.1885 translation, annotated for English study.

- The Arabian Nights by Andrew Lang at Project Gutenberg

- 1001 Nights, Representative of eastern literature (in Persian)

- «The Thousand-And-Second Tale of Scheherazade» by Edgar Allan Poe (Wikisource)

- Arabian Nights Six full-color plates of illustrations from the 1001 Nights which are in the public domain

- (in Arabic) The Tales in Arabic on Wikisource

Prince Ahmed and The Fairy. A poem by Letitia Elizabeth Landon from Forget Me Not, 1826.

?

Log in

If this type of authorization does not work for you, convert your account using the link

-

-

November 23 2015, 18:54

- Литература

- История

- Cancel

«Тысяча и одна ночь»

Шахерезада и Султан Шахрияр.1880.Ferdinand Keller

Шахерезада — легендарная главная героиня «Рассказа о царе Шахрияре и его брате»,

окаймляющего персидский сказочный цикл «Тысяча и одна ночь» и служащего связующей нитью между другими рассказами.

Шехерезада. Sophie Gengembre Anderson.

Шахерезада – легендарный персонаж ‘Тысячи и одной ночи’, девушка удивительной красоты в сочетании с острым умом и редкостным красноречием.

Она является символом женского коварства и изобретательности, и даже те, кто точно не знает, кем же на самом деле является Шахерезада, так или иначе слышали о ней как об искусной обольстительнице.

Шехерезада Альберто Варгас. 1921

Шахерезада была дочерью визиря грозного и деспотичного персидского царя Шахрияра .

Известно, что был Шахрияр очень немилостив к женщинам.

William Clarke Wontner

Так, уличив однажды в неверности свою жену, он в ярости приказал немедленно убить ее, но и этого ему показалось мало.

И тогда Шахрияр задумал новую месть – каждую ночь он требовал в свою опочивальню новую молодую женщину,

а наутро неизменно приказывал убивать своих ночных любовниц.

Любимицы эмира.1879 Benjamin-Constant

Таким образом грозный правитель мстил всем женщинам за измену жены.

Так продолжалось несколько лет.

В то время у его визиря подросла дочь по имени Шахерезада, девушка необычайной красоты и острого ума.

Энгр. «Большая одалиска».

Так, в один из дней она попросила отца сосватать ее в жены Шахрияру.

Визирь пришел в ужас от такого предложения – отдавать собственную красавицу-дочь деспоту казалось ему полным безрассудством, ведь все, что ждало ее впереди – неминуемая смерть.

Но Шахерезада умела настоять на своем, и вскоре Шахрияр уже призвал к себе в спальню новую молодую жену.

Одалиска.Joseph Severn (1793 – 1879)

В отличие от всех предыдущих девушек Шахерезада не удовольствовалась одной лишь функцией любовницы,

но начала рассказывать царю сказку.

Edouard Richter

Сюжет этой сказки оказался настолько захватывающим, что когда наступил рассвет, царь пожелал услышать его продолжение.

И тогда-то Шахерезада пообещала ему, что если доживет до следующей ночи, Шахрияр непременно услышит продолжение сказки.

Karel Ooms — Dreaming in the harem

Так ей удалось уцелеть после ночи с грозным правителем, что, увы, не удавалось до нее еще ни одной девушке. Вероятно, Шахерезаде удалось произвести на правителя немалое впечатление, и когда пришла следующая ночь, он, вопреки своим правилам, велел позвать снова ее.

Léon-François Comerre -Одалиска с бубном

Шахерезада снова рассказывала свою сказку – и ночи едва хватило на то, чтобы дойти до конца, а когда сказка закончилась, владыка немедленно потребовал новую сказку, и в результате ей снова удалось остаться живой,

а Шахрияр снова ждал наступления следующего вечера.

Harem Orientalism.

Так продолжалось тысячу и одну ночь, и за эти годы Шахерезада успела не только рассказать Шахрияру огромное количество сказок, но и родить троих сыновей.

Чарльз Folkard, «Тысяча и одна ночь» . (Шехерезада)

Шахрияр просто обожал свою красноречивую жену, требуя от нее все новых и новых сказок,

на которые Шахерезада была большая мастерица.

Тысяча и одна ночь.Эндрю Лэнга

Когда по истечение тысячи и одной ночи все сказки Шахерезады закончились, грозный правитель уже любил ее

так сильно, что и подумать не мог об ее казни.

Фредерик Лейтон, Свет гарема, 1880.(деталь)

Образ прекрасной и одновременно хитрой и обольстительной Шахерезады множество раз вдохновлял композиторов и поэтов.

Так, под впечатлением ‘Арабских сказок’ написал свою знаменитую симфоническую сюиту Н. А. Римский-Корсаков, существует и классический балет с одноименным названием, а также несколько кинофильмов.

An Oriental Flower Girl

История Шахрияра и Шахерезады – одна из самых глубоких и удивительных историй в литературе.

Известно, что первоначально в арабских сказках эту женщину звали Ширазад (Šīrāzād), но сегодня все знают ее как Шахерезаду.

Лейла ( Страсть) .1892.Сэр Фрэнк Бернард Дикси (1853-1928)

Образ рассказчицы Шахерезады связан прежде всего с восточной красавицей, обольстительной и желанной, сдадкозвучной и красноречивой.

текст Полина Челпанова

Бисмиллях-и р-Рахман-и р-Рахим.

Более трёх столетий прошло с тех пор, как в Европе впервые познакомились со сказками “1000 и 1 ночи”, но они и доныне сохранили своё обаяние. В мировой литературе не много найдётся книг, столь же любимых читателями, как знаменитые сказки Шахерезады. Мы с детства помним её героев – веселого, предприимчивого Ала-ад-Дина (“Вера Аллаха”), отважного, ненасытно-любознательного Синдбада (“Властелин моря”), пронырливую Далилу; в более зрелом возрасте нас пленяет образ кроткой, любящей Азизы (“Красавица”), до смерти сохранившей верность своему чувству, смешит “молчаливый” цирюльник. Трудно сказать, что больше всего привлекает в лучших сказках “1001 ночи” – занимательность сюжета, причудливое сплетение фантастического и реального, живые картины городской жизни средневекового мусульманского Востока, описание удивительных стран или живость и яркость переживаний героев, действующих в сказках, психологическая оправданность ситуаций, ясная и определённая мораль. Великолепен и язык сказок – яркий, образный и сочный, чуждый обиняков и недомолвок. Речь героев лучших сказок “1001 ночи” ярко индивидуальна, у каждого из них свой стиль и лексика, характерные для той социальной среды, из которой они происходят. Родившиеся в народе наиболее ценные сказки ”1001 ночи”, как всякий плод подлинно народного творчества, отражают чаяния трудящихся масс, их стремления и идеалы. Сочетания всех этих достоинств и обеспечило этим сказкам немеркнущую славу, обусловило их влияние на творчество многих писателей и поэтов. И в России, и в Европе “1001 ночь” нашла себе множество почитателей и подражателей. Высоко ценил арабские сказки Пушкин Александр Сергеевич.

Что же такое “1001 ночь”, как и когда она создавалась?

“Тысяча и одна ночь” – собрание сказок на арабском языке, объединённых обрамляющим рассказом о жестоком правителе на островах Индии и Китая падишахе Шахрияре, который каждую ночь брал себе новую жену и наутро убивал её. И когда в падишахстве Шахрияра не осталось больше молодых девушек, кроме Шахерезады, дочери его вазира (вазир или визирь = “нести ношу”), настал её час предстать перед падишахом. Чтобы спасти себя, Шахерезада начала рассказывать падишаху сказку и к утру обрывала её на самом интересном месте. Шахрияр, желая дослушать интересный рассказ, отложил казнь Шахерезады. Вечером, окончив эту сказку, дочь вазира принялась за другую и опять остановилась на середине. Так продолжалось тысяча и одну ночь. За это время Шахерезада подарила падишаху троих сыновей, и Шахрияр решил помиловать Шахерезаду. Такова сказка, открывающая и завершающая сборник рассказов “1001 ночи” в том виде, в каком он дошёл до нас.

Первые письменные сведения о книге сказок, обрамлённых повестью о Шахерезаде и Шахрияре, исследователи находят в сочинении арабского библиографа X века ан-Надима, который говорит о ней как о давно и хорошо известном произведении. Уже в те времена история возникновения сборника на арабской почве была забыта, и считалось, что это перевод с фарси. Состав и содержание сборника, о котором говорит вышеупомянутый библиограф, носившего название “Тысяча ночей”, учёным неизвестны, но обрамляющая сказка в нём присутствовала. В дальнейшем эволюция сборника продолжалась. В разные времена в его удобную рамку вкладывались всё новые и новые сказки разных жанров и разного социального происхождения. Под названием “1001 ночь” имело хождение большое количество сборников повестей, составителями и собирателями которых были записывавшие их профессиональные сказочники, а в дальнейшем – книготорговцы. Свой окончательный вид сборник получил в XV веке в Египте, а литературная редакция его, по-видимому, относится к более позднему времени. Поэтому попытки определить точно время и место возникновения той или иной сказки в её первоначальном виде обречены на неудачу. Таким образом, сказки “1001 ночи” не является произведением отдельного автора или составителя; её творец – народ. Сюжеты сказок известны с глубокой древности и давно стали достоянием арабского фольклора. При исследовании “1001 ночи” каждую сказку приходится рассматривать отдельно, так как по содержанию они между собою не связаны. Однако у некоторых сказок можно заметить общие черты, позволяющие хотя бы условно объединить их в группы, как по времени создания, так и в отношении породившей их социальной среды.

К древнейшим сказкам “1001 ночи” следует отнести те рассказы, в которых наиболее сильно проявляется элемент фантастики и действуют фантастические существа,принимающие активное участие в делах людей. Таковы, например, сказки “О рыбаке и духе”, “О коне из чёрного дерева”.

И, наконец, самыми поздними по времени создания “Тысяча и одной ночи” являются сказки плутовского жанра, включённые в сборник в Египте, в последние его редакции. Рассказы эти тоже сложились в среде городского населения, но отражают жизнь мелких ремесленников, подённых рабочих и бедняков, перебивающихся случайными заработками. В них наиболее ярко выражен протест угнетённых слоёв феодального восточного города. Для плутовских сказок характерны едкая ирония, показ в самом неприглядном виде представителей светской власти и духовенства. Сюжетом большинства таких повестей является сложное мошенничество, преследующее цель не столько ограбить, сколько одурачить потерпевшего. Блестящий образец плутовских сказок – “Повесть о Далиле-Хитрице и Али-Зейбаке Каирском”, изобилующая самыми запутанными и невероятными приключениями,

Совершенно иной характер носят сказки литературного происхождения, нередко весьма объёмистые, которые нельзя отнести ни к одной из перечисленных групп. Лучшим образцом их может служить “Сказка о Синдбаде-мореходе”. (Персидское имя Синдбад происходит от санскритского Сиддхупати, т. е. “Властелин моря”. Эти рассказы пользовались большим успехом). В своей книге «По следам Синдбада-морехода» Шумовский Т. А. подробно разбирает плавания Синдбада, купца из Басры, чьей родиной был Оман.

Сказки той или иной группы рождались в определённой социальной среде и имели в ней наибольшее распространение. Об этом, между прочим, свидетельствует и пометка переписчика на одной из рукописей “1001 ночи”. Рассказчику надлежит рассказать в соответствии с тем, кто его слушает. Если это простолюдины, пусть он передаёт им рассказы о простых, — это повести плутовского жанра, а если эти люди относятся к правителям, то надлежит им рассказывать повести о царях и сражениях между витязями. Именно средой, в которой сложилась и для которой предназначалась сказка, определяется не только тема, но и стиль, и словесное оформление повествования. Длиннейшие рыцарские романы и фантастические сказки, которые могли много дней подряд слушаться в палатах правителей и вельмож, отвечая вкусам такой аудитории, выдержаны в напыщенно-приподнятом тоне, изобилуют обширными отступлениями и поэтическими цитатами, по большей части наставительного содержания. Немало стихотворных отступлений и в городских новеллах, имевших наибольший успех среди богатых торговцев и ремесленников, но характер их уже несколько иной – скорее эротический, чем морализирующий. Не чужда таким сказкам и непристойность, отсутствующая, как правило, в первой группе повестей.

Совершенно в ином духе выдержаны плутовские сказки. Длинные периоды любовных эпизодов городских новелл сменяются в плутовских сказках сжатыми, меткими диалогами. Стихотворных цитат в них почти нет, — отступления в область поэзии, видимо, были не по вкусу беднякам, теснившимся на базарах, в дешёвых кофейнях. Они любили весёлые, озорные сказки.

Таковы основные группы сказок, составляющих собрание “1001 ночи”. У себя на родине сказки Шахерезады в различных социальных слоях встречали разное отношение. В то время как в народе и в кругах передовой, мыслящей интеллигенции они и доныне пользуются большой любовью, мусульманские учёные-филологи всегда относились к ним резко отрицательно. Уже в X столетии упомянутый выше библиограф ан-Надим с презрением пишет, что сказки “1001 ночи” написаны “жидко и нудно”, а позднейшие хулители считали их безнравственными и вредными, и предрекали тем, кто их читал или рассказывал, всевозможные несчастья. Однако это не помешало арабским сказкам приобрести мировую известность. Начиная с XVII века они неоднократно переводятся на многие языки мира, и пользуются неизменным успехом у читателя. Им, сказкам “1001 ночи”, подражают европейские писатели, Гауф, например. Композиторы Римский-Корсаков и Равель, например, написали соответствующие симфонии — «Шахерезада», живописец Энгр, тоже например, создал целую серию полотен о гаремных женщинах, одалисках (турецкое слово). В кинематографе сколько было экранизаций даже трудно написать, например «Багдадский вор».

Иншаалла.

Главные герои: как не странно, именно халиф-аббасид Гарун ар-Рашид (763-809), герой многих сказок «Тысячи и одной ночи», — реально существовал. При нём арабы были оттеснены на третье место после персов и сирийцев. При нём в 799 первая редакция сказок.

Шахрияр – потомок мифического шах-ин-шаха Сасана. Справедливый и добрый царь. (шах = “царь”).

Шахерезада – старшая дочь вазира падишаха Шахрияра, Шамс-ад-Дина, супруга падишаха Шахрияра. Шахерезада была девушкой умной и начитанной, играла на ситаре и дутаре, знала астрологию и иностранные языки, фарси, например, играла в шахматы. (Заде или зоде = “принц”, “принцесса”. Составная часть персидских имён, Шахзаде, Амирзода, например).

Шахземан – младший брат, единородный, падишаха Шархрияра, амир Самарканда.

Дуньязаде – младшая, единородная, сестра Шахерезады. (Заде или зоде = принц, принцесса. Составная часть персидских имён, Шахзаде, Амирзода, например).

Симург – мифическая царь-птица;

Гурии – “чёрноокие”; непорочные красавицы, обещанные правоверным в раю;

Хумаюн (Хума) – птица-феникс. Тот, на кого упадёт тень Хумаюна, обретает благодать и власть;

Гуль – враждебная человеку демоница. Гули сбивали человека с пути, нападали на него и пожирали;

Дервиш – член религиозного общества, приверженцев суфизма. Дервиши стремятся к мистическому единению с богом;

Див (дэв) – злой дух;

Ифрит – злой дух;

Азраил – ангел смерти;

Пэри – добрая фея, символ красавицы, всегда помогает сказочному герою.

- 1-Как зовут единородную сестру Шахерезады?

- 2-Где Родина прототипа Синдбада-морехода?

- 3-Входят ли сказки о Ходже Наср-ад-Дине в общий cвод “Ночей”?

![[ G ] Oliver Dennett Grover - Harem scene (1889) by Cea., via Flickr:](https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/736x/19/8d/b6/198db610216e02ec32db78cd2b1f2e6c.jpg)