Русская народная сказка «По щучьему велению» была и остается любима во все времена. В ней много добра, шуток и волшебства. Больше всего читателя привлекает комический персонаж, над которым все смеялись, а он стал царским зятем. Краткое содержание «По щучьему велению» подойдет для работы с читательским дневником в 3 классе.

Оглавление:

- Герои и их характеристика

- Сюжет в сокращении

- Основная мысль

Герои и их характеристика

Сказка о парне, который все время лежал на печи, а потом взял в жены царскую дочь, —воображение народного творчества. Автор этого сказания остался неизвестным. На момент первого издания уже имелось 3 разных варианта произведения. В самой популярной версии фигурируют 4 героя:

- Емеля.

- Щука.

- Царь.

- Марья-царевна.

Главным персонажем произведения является Емеля. Характеристика этого героя сказки «По щучьему велению» противоречива. Его не относят к отрицательному лицу, но и не считают классическим положительным образом. Он простодушный, ленивый, ведомый и смекалистый парень.

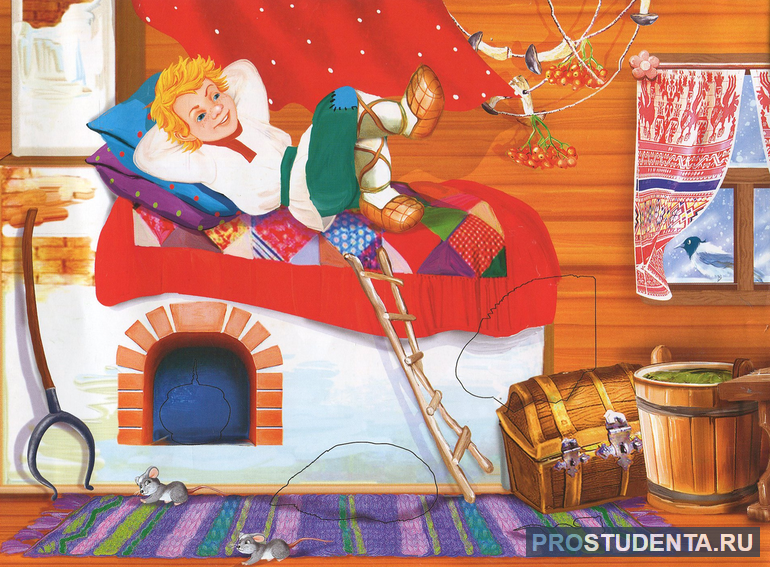

Емеля родился в семье обычного крестьянина и был младшим сыном. Старшие братья много трудились для того, чтобы обеспечить свои семьи. А Емеля совсем не вставал с печи и вел себя, как ребенок. Но ему в жизни повезло больше, чем старшим братьям. Он поймал волшебную рыбу и обеспечил себе беззаботную жизнь.

Главный герой не был жестоким. Он не стал мучить бедную щуку, а отпустил ее в воду. В знак благодарности она сообщила рыбаку заветные слова, которые помогли лежебоке исполнять все желания. В славянской мифологии образ щуки символизирует благополучие и удачу. Двух героев связывает между собой целый мир эмоций. Емеля — человек с сильным эмоциональным фоном, и говорящая щука, которая является представителем водной стихии. А вода — символ чувствительности.

Другие персонажи сказки старались скрыть свои эмоции. Так, царь был человеком хорошим, но умственным потенциалом не отличался. Не сразу в его голову пришла мысль о том, как использовать одаренного парня. Но он точно знал, что такой зять в хозяйстве определенно может пригодиться. Как отец он повел себя бессердечно и жестоко по отношению к дочке. Ведь Емеля был совсем некрасивым молодым человеком.

Марья-царевна по-настоящему влюбилась в главного героя из сказки «По щучьему веленью». Она как натура романтическая назло отцу сбежала с любимым. Царская дочь была красивой барышней и в будущем стала верной женой.

Сюжет в сокращении

В одной деревушке жил старик, и было у него три сына: два умных, а третий — дурачок. Отец умер, и братьям пришлось самим зарабатывать на жизнь. Старшие сыновья женились и стали каждый день трудиться на полях. А Емеля лежал на теплой печке и вел пассивный образ жизни. Никакой работы ему делать не приходилось, и к этому уже все привыкли.

Однажды братья уехали торговать собранным урожаем, а младшего лежебоку с невестками оставили дома заниматься хозяйством. За это Емеле пообещали привезти с ярмарки красный кафтан. Пришлось ему в один из морозных дней по просьбам невесток отправиться за водой.

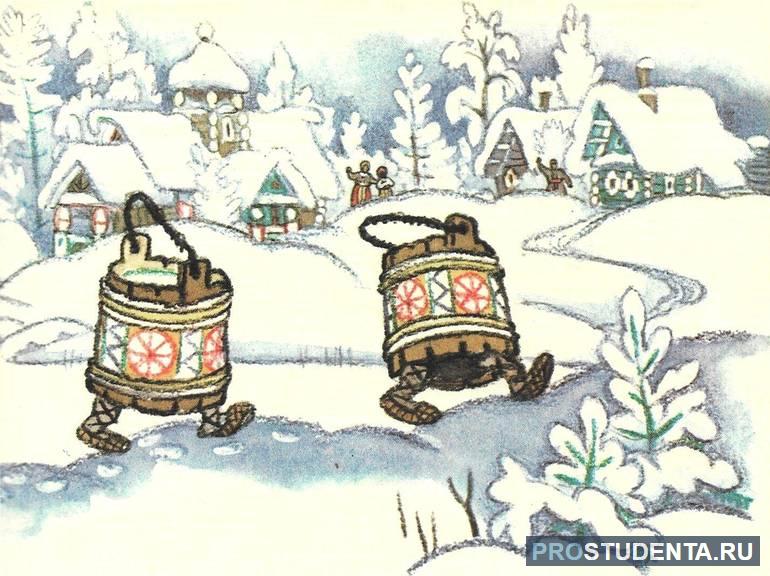

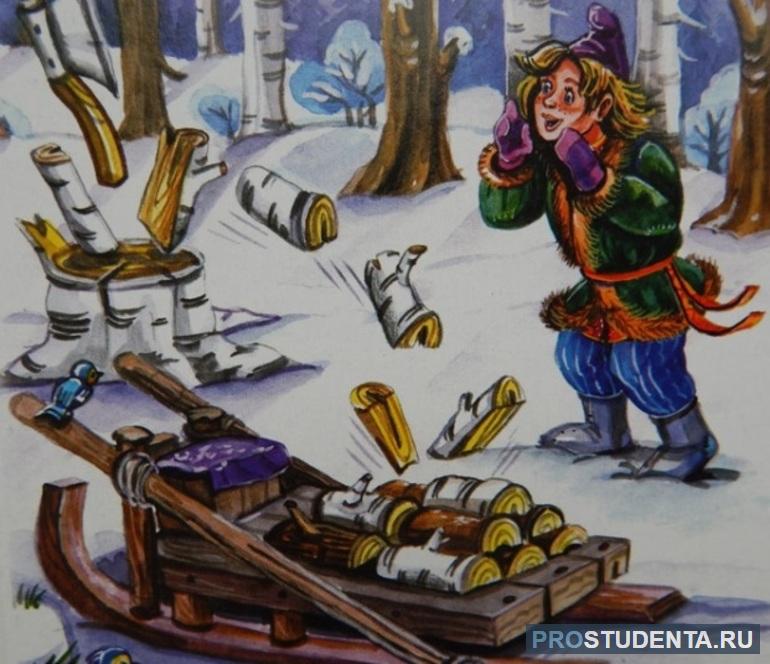

Набрав целое ведро, увидел парень в проруби щуку и поймал ее. Щука человеческим языком попросила отпустить ее, а взамен пообещала исполнить любое желание. Довольный юноша попросил, чтобы ведра сами в дом пошли. Все так и произошло. Удивлённые невестки на следующее утро отправили парня дров нарубить. Емеля произнес волшебную фразу: «По щучьему велению, по моему хотению» — и сани сами без лошадей поехали в лес.

Как люди ни пытались поймать чудака, ничего у них не вышло. В лесу дрова сами рубились и складывались в телегу. На обратном пути толпа снова предприняла попытки поймать парня, но дубинки спасли Емелю от обидчиков, и он спокойно добрался до дома.

По приказу короля воевода хотел забрать дурачка и отвезти Его Величеству. Но у него ничего вышло. Рассердился король и пригрозил офицеру: если не доставит к нему парня, то лишится головы. Отправился боярин к юноше и хитростью выманил его из дома. Решил Емеля к королю на печке своей ехать. Увидя в окне принцессу, он наколдовал, чтобы она в него влюбилась.

Когда Емеля покинул дворец, королевская дочь стала уговаривать отца выдать ее замуж за чудака. Но царь решает посадить обоих в бочку и сбросить в море. Проснувшись в заточении, хлопец произнес волшебную фразу, и море выкинуло бочку на берег. Сосуд рассыпался, и молодые оказались на красивом полуострове.

Емеля построил роскошный дворец и хрустальный мост до королевского замка. А сам дурачок превратился в умного и красивого молодца. По приглашению приехал король и не узнал главного героя. Сам правитель дал согласие на брак молодых. Закончилась сказка тем, что царь попросил у Емели прощения за свою жестокость по отношению к нему.

В обычном волшебном сюжете русской сказки заложена мудрость и глубина народной мысли. Ее можно читать не только детям, но и взрослым. Для описания краткого содержания сказки «По щучьему велению» необходимо составить план пересказа:

- Жизнь братьев.

- Емеля поймал щуку.

- Первые желания.

- Похождения Емели в городе.

- Как вельможа хотел доставить лентяя к царю.

- Хитрость офицера.

- Любовь.

- Как царь обманул Емелю.

- Чудесное спасение влюбленных.

- Новая жизнь.

- Извинения царя.

Не стоит останавливаться на прочтении аннотации. Сказка про Емелю в кратко изложенном содержании поможет не только ознакомиться с главными героями и их поступками, но и понять основную мысль повествования.

Основная мысль

Произведение учит читателя тому, что если жизнь преподносит хорошие подарки, то от них не стоит отказываться. Но и нужно уметь распоряжаться теми ресурсами, которыми человек владеет. По счастливому случаю Емеле просто повезло. Если бы он был невнимательным, то ему не удалось бы поймать щуку в проруби.

Кроме этого, главный герой обладал ловкостью и находчивостью. Он сумел изловить рыбу голыми руками зимой в промерзшей реке. В этот день удача повернулась к нему лицом, а он не упустил своей возможности. Многие в наше время попросили бы у рыбы чего-то необычного, но желание Емели было простым, как и его русская душа.

Современники утверждают, что подобная воля — признак не дурости и лени, а наоборот, креативности и смышлёности. Ведь он устроил себе беззаботную жизнь и при этом не вышел из зоны комфорта. Это говорит о том, что главной мыслью сказки является то, что человек сам решает, будет он счастливым или нет.

Необходимо знать, чего на самом деле человек желает, без этого ничего не получится. Емеля знал, что до поры до времени может находиться в расслабленном состоянии и отлеживаться на печи. Мудрые невестки смогли сдвинуть парня с мертвой точки, и он интуитивно поддался им и получил выгоду.

Конечно, в настоящей жизни нельзя поймать волшебную рыбу, но творить добро человек сможет. И тогда даже за самые крошечные поступки можно поймать удачу и стать по-настоящему счастливым.

| At the Pike’s Behest! | |

|---|---|

Emelian rides on the horseless sled. Illustration by Valery Kurdyumov, 1913. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | At the Pike’s Behest! |

| Also known as | Emelian, the Fool Emelya the Simpleton |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 675 (The Lazy Boy) |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Narodnye russkie skazki by Alexander Afanasyev |

| Related | Peruonto The Dolphin Half-Man Foolish Hans (de) Peter the Fool (fr) |

Emelya the Simpleton (Russian: Емеля-дурак) or At the Pike’s Behest (Russian: По щучьему веленью) is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis[edit]

Emelya lived in a village on the shore of the Volga River with his two brothers and their wives. Although he was good-looking, he was also foolish, lazy, and despised work. He spent his days sitting on the clay stove in the kitchen. His brothers ran a trading business left to them by their dead father. The brothers left Emelya one day, to sell their wares along the river, leaving Emelya with the wives, promising to return with a kaftan, red boots, and a red hat for their brother.

During the days and weeks the brothers were gone, the wives tried unsuccessfully to get Emelya to do work, until one day, they left Emelya with a choice: get water from the frozen river, or no dinner and no kaftan, red boots and red hat. At that threat, Emelya hurried on his way, and on reaching the river, he grumbled about his problems while hacking away at the thick ice. As he scooped water into the buckets, he noticed he had caught a fish: a large pike. Emelya was going to take it home for supper, but the pike pleaded with him, promising that if Emelya were to let him go, that Emelya would never need to work again, which was a tempting offer for lazy Emelya. All he would need to say, was “By the Pike’s command, and at my desire-(command)“ and his will would be done. Emelya agreed, and to his surprise, the commands worked.

Emelya was not careful to conceal his new talent for work, and soon the tsar heard about it, and ordered this ‘magician’ to appear before him at his palace by the Caspian Sea. Emelya, being foolish and lazy, ordered his stove to take him to the tsar, using the Pike’s command. He arrived instantly at the palace before the tsar, still lying on his stove, where he looked down on the tsar and was not acting the way a subject should towards his superior. The tsar would have ordered his head cut off, had he not wanted the secret to the boy’s power. However, he could not extract the secret from Emelya, so he tried to use his daughter to get the secret. After three days of teaching each other games, the princess had learned only that Emelya was handsome, fun, and charming. She wanted to marry him. The tsar was at first angry, then decided that Emelya would perhaps give up his secret to his wife, if he became married. So he arranged for a wedding.

At first, Emelya was horrified at the idea, believing a wife to be more trouble than it was worth. He agreed, though, and the wedding feast was held soon after, at which Emelya finally got down from his stove. During the feast, Emelya had terrible table manners, which convinced the tsar to finally rid himself of the obnoxious boy. A sleeping potion was added to Emelya’s wine, he was thrown in a barrel and tossed into the sea, and his bride banished to an island in the sea opposite the palace. While floating in the waves, Emelya encountered his friend the pike, who allowed Emilyan to wish for anything his heart desired, since he had not abused his power. Emelya wished for wisdom, and when the pike pushed him to the island, Emelya fell in love with his wife. He had the hut on the island transformed into a beautiful palace, with a crystal bridge connecting to the mainland, so that his wife could visit her father, the tsar. With his new-found wisdom, he made amends with everyone, and thereafter lived happily and ruled well.

Translations[edit]

The tale was translated into English as Emelyan, the Fool,[1][2][3] Emilian the Fool,[4] Emelya and the Pike[5] and At the Behest of the Pike.[6]

The tale was also translated as By the Will of the Pike, by Irina Zheleznova.[7]

The tale can also be known as At the Wish of the Fish.[8]

English versions[edit]

The story was retold and translated into English by Lee Wyndham in «Russian Tales of Fabulous Beasts and Marvels», illustrated by Charles Mikolaycak. Other Russian tales told by Lee Wyndham include Ivashko and the Witch, Kuzenko Sudden-Wealthy, The Magic Acorn, and The Firebird.

The tale was also published as a standalone book titled The Fool and the Fish, with illustrations by artist Gennady Spirin.

The tale was retold as Ivan the Fool and the Magic Pike by James Riordan.[9]

Analysis[edit]

The tale first appeared in a German language compilation of fairy tales, published by Anton Dietrich in 1831, in Leipzig. Its name was Märchen von Emeljan, dem Narren.[10] Jacob Grimm, of his famed collection, noted its great resemblance with Peruonto.[11] The similarity was also noted by mythologist Thomas Keightley, in the 19th century, in his book Tales and Popular Fictions.[12]

19th century Portuguese folklorist Consiglieri Pedroso claimed that the tale is a popular one, specially «in the East of Europe». Its name in Russian compilations are Emilian the Fool or By the Pike’s Will.[13]

Jack Haney stated that the tale is «common throughout the Eastern Slavic world».[14]

Portuguese author José Teixeira Rêgo suggested that the story of Emiliano Parvo («The Foolish Emelian») was «a deformed [narrative] of the flood myth». He also considered the text of Emelian the Fool as a more complete version of the story, which would allow him to formulate his hypothesis. For instance, he compared the episode of Emelyan meeting the pike in the ocean and its help to Matsya, pisciform avatara of Vishnu, being released by king Manu and, in turn, alerting the human about the upcoming great deluge and helping him reach terra firma.[15] He also compared the crystal bridge the pike produces with his magic to a rainbow the gods send the survivors of the flood.[16]

Variants[edit]

Folklorist Alexander Afanasyev compiled two variants of the tale about the magic pike wherein the protagonist is the foolish character.[17][18][19]

He also collected another version about the magic pike, but the protagonist is simply a humble man, instead of a stupid and lazy boy.[20][21][22]

Cultural legacy[edit]

The tale was adapted into the 1938 film Wish upon a Pike and four Soviet animated films (1938, 1957, 1970, 1984).

See also[edit]

- The Fisherman and His Wife (German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm)

- The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Alexander Pushkin’s fairy tale in verse)

References[edit]

- ^ Steele, Robert. The Russian garland: being Russian folk tales. London: A.M. Philpot. [1916?] pp. 166-182.

- ^ Tibbitts, Charles John. Folk-Lore and Legends: Russian and Polish. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1891. pp. 58-75.

- ^ Dietrich, Anton, and Jacob Grimm. Russian Popular Tales: Tr. From the German Version of Anton Dietrich. London: Chapman and Hall, 1857. pp. 152-.168 [1]

- ^ Ralston, William Ralston Shedden. Russian Folk-tales. New York: R. Worthington, 1878. pp. 269-272.

- ^ The Three Kingdoms: Russian Folk Tales From Alexander Afanasiev’s Collection. Illustrated by A. Kurkin. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. 1985. Tale nr. 17.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. Russian Folk-Tales. Edited and Translated by Leonard A. Magnus. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. 1915. pp. 274-280.

- ^ Vasilisa the Beautiful: Russian Fairytales. Edited by Irina Zheleznova. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. 1984. pp. 124-134.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 128. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9

- ^ Riordan, James. Russian Folk-Tales. Oxford University Press. 2000. pp. 18-26. ISBN 0 19 274536 0.

- ^ Dietrich, Anton. Russische Volksmärchen in den Urschriften gesammelt und ins Deutsche übersetzt. Leipzig: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung. 1831. pp. 171-186. [2]

- ^ Dietrich, Anton, and Jacob Grimm. Russian Popular Tales: Tr. From the German Version of Anton Dietrich’. London: Chapman and Hall, 1857. p. viii. [3]

- ^ Keightley, Thomas. Tales And Popular Fictions: Their Resemblance, And Transmission From Country to Country. London: Whittaker. 1834. pp. 303-336. [4]

- ^ Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society. 1882. pp. vii.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2019 [2001]. p. 437. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ Leeming, David Adams. A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-512052-3.

- ^ Rego, José Teixeira. «Os animais agradecidos nos contos populares e o dilúvio». In: Revista de Estudos Históricos, v. 1 (1924), pp. 8-23.

- ^ Tales nr. 165-166: «Емеля-дурак». In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume I, Volume 1. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2014. ISBN 978-1-62846-093-3

- ^ «Emelia the Fool.» In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I, edited by Haney Jack V., 429-38. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. Accessed November 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qhm7n.110.

- ^ Народные русские сказки (Афанасьев)/Емеля-дурак

- ^ Tale nr. 167: «По щучьему веленью». In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume I, Volume 1. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2014. ISBN 978-1-62846-093-3

- ^ «At the Pike’s Command.» In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I, edited by Haney Jack V., 439-42. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. Accessed November 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qhm7n.111.

- ^ Народные русские сказки (Афанасьев)/По щучьему веленью

Bibliography[edit]

- Lee Wyndham, Russian Tales of Fabulous Beasts and Marvels, “Foolish Emilyan and the Talking Fish”

- Thomas P. Whitney (transl.), In a Certain Kingdom: Twelve Russian Fairy Tales

- Moura Budberg and Amabel Williams-Ellis, Russian Fairy Tales

| At the Pike’s Behest! | |

|---|---|

Emelian rides on the horseless sled. Illustration by Valery Kurdyumov, 1913. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | At the Pike’s Behest! |

| Also known as | Emelian, the Fool Emelya the Simpleton |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 675 (The Lazy Boy) |

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Narodnye russkie skazki by Alexander Afanasyev |

| Related | Peruonto The Dolphin Half-Man Foolish Hans (de) Peter the Fool (fr) |

Emelya the Simpleton (Russian: Емеля-дурак) or At the Pike’s Behest (Russian: По щучьему веленью) is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis[edit]

Emelya lived in a village on the shore of the Volga River with his two brothers and their wives. Although he was good-looking, he was also foolish, lazy, and despised work. He spent his days sitting on the clay stove in the kitchen. His brothers ran a trading business left to them by their dead father. The brothers left Emelya one day, to sell their wares along the river, leaving Emelya with the wives, promising to return with a kaftan, red boots, and a red hat for their brother.

During the days and weeks the brothers were gone, the wives tried unsuccessfully to get Emelya to do work, until one day, they left Emelya with a choice: get water from the frozen river, or no dinner and no kaftan, red boots and red hat. At that threat, Emelya hurried on his way, and on reaching the river, he grumbled about his problems while hacking away at the thick ice. As he scooped water into the buckets, he noticed he had caught a fish: a large pike. Emelya was going to take it home for supper, but the pike pleaded with him, promising that if Emelya were to let him go, that Emelya would never need to work again, which was a tempting offer for lazy Emelya. All he would need to say, was “By the Pike’s command, and at my desire-(command)“ and his will would be done. Emelya agreed, and to his surprise, the commands worked.

Emelya was not careful to conceal his new talent for work, and soon the tsar heard about it, and ordered this ‘magician’ to appear before him at his palace by the Caspian Sea. Emelya, being foolish and lazy, ordered his stove to take him to the tsar, using the Pike’s command. He arrived instantly at the palace before the tsar, still lying on his stove, where he looked down on the tsar and was not acting the way a subject should towards his superior. The tsar would have ordered his head cut off, had he not wanted the secret to the boy’s power. However, he could not extract the secret from Emelya, so he tried to use his daughter to get the secret. After three days of teaching each other games, the princess had learned only that Emelya was handsome, fun, and charming. She wanted to marry him. The tsar was at first angry, then decided that Emelya would perhaps give up his secret to his wife, if he became married. So he arranged for a wedding.

At first, Emelya was horrified at the idea, believing a wife to be more trouble than it was worth. He agreed, though, and the wedding feast was held soon after, at which Emelya finally got down from his stove. During the feast, Emelya had terrible table manners, which convinced the tsar to finally rid himself of the obnoxious boy. A sleeping potion was added to Emelya’s wine, he was thrown in a barrel and tossed into the sea, and his bride banished to an island in the sea opposite the palace. While floating in the waves, Emelya encountered his friend the pike, who allowed Emilyan to wish for anything his heart desired, since he had not abused his power. Emelya wished for wisdom, and when the pike pushed him to the island, Emelya fell in love with his wife. He had the hut on the island transformed into a beautiful palace, with a crystal bridge connecting to the mainland, so that his wife could visit her father, the tsar. With his new-found wisdom, he made amends with everyone, and thereafter lived happily and ruled well.

Translations[edit]

The tale was translated into English as Emelyan, the Fool,[1][2][3] Emilian the Fool,[4] Emelya and the Pike[5] and At the Behest of the Pike.[6]

The tale was also translated as By the Will of the Pike, by Irina Zheleznova.[7]

The tale can also be known as At the Wish of the Fish.[8]

English versions[edit]

The story was retold and translated into English by Lee Wyndham in «Russian Tales of Fabulous Beasts and Marvels», illustrated by Charles Mikolaycak. Other Russian tales told by Lee Wyndham include Ivashko and the Witch, Kuzenko Sudden-Wealthy, The Magic Acorn, and The Firebird.

The tale was also published as a standalone book titled The Fool and the Fish, with illustrations by artist Gennady Spirin.

The tale was retold as Ivan the Fool and the Magic Pike by James Riordan.[9]

Analysis[edit]

The tale first appeared in a German language compilation of fairy tales, published by Anton Dietrich in 1831, in Leipzig. Its name was Märchen von Emeljan, dem Narren.[10] Jacob Grimm, of his famed collection, noted its great resemblance with Peruonto.[11] The similarity was also noted by mythologist Thomas Keightley, in the 19th century, in his book Tales and Popular Fictions.[12]

19th century Portuguese folklorist Consiglieri Pedroso claimed that the tale is a popular one, specially «in the East of Europe». Its name in Russian compilations are Emilian the Fool or By the Pike’s Will.[13]

Jack Haney stated that the tale is «common throughout the Eastern Slavic world».[14]

Portuguese author José Teixeira Rêgo suggested that the story of Emiliano Parvo («The Foolish Emelian») was «a deformed [narrative] of the flood myth». He also considered the text of Emelian the Fool as a more complete version of the story, which would allow him to formulate his hypothesis. For instance, he compared the episode of Emelyan meeting the pike in the ocean and its help to Matsya, pisciform avatara of Vishnu, being released by king Manu and, in turn, alerting the human about the upcoming great deluge and helping him reach terra firma.[15] He also compared the crystal bridge the pike produces with his magic to a rainbow the gods send the survivors of the flood.[16]

Variants[edit]

Folklorist Alexander Afanasyev compiled two variants of the tale about the magic pike wherein the protagonist is the foolish character.[17][18][19]

He also collected another version about the magic pike, but the protagonist is simply a humble man, instead of a stupid and lazy boy.[20][21][22]

Cultural legacy[edit]

The tale was adapted into the 1938 film Wish upon a Pike and four Soviet animated films (1938, 1957, 1970, 1984).

See also[edit]

- The Fisherman and His Wife (German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm)

- The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish (Alexander Pushkin’s fairy tale in verse)

References[edit]

- ^ Steele, Robert. The Russian garland: being Russian folk tales. London: A.M. Philpot. [1916?] pp. 166-182.

- ^ Tibbitts, Charles John. Folk-Lore and Legends: Russian and Polish. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1891. pp. 58-75.

- ^ Dietrich, Anton, and Jacob Grimm. Russian Popular Tales: Tr. From the German Version of Anton Dietrich. London: Chapman and Hall, 1857. pp. 152-.168 [1]

- ^ Ralston, William Ralston Shedden. Russian Folk-tales. New York: R. Worthington, 1878. pp. 269-272.

- ^ The Three Kingdoms: Russian Folk Tales From Alexander Afanasiev’s Collection. Illustrated by A. Kurkin. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. 1985. Tale nr. 17.

- ^ Afanasyev, Alexander. Russian Folk-Tales. Edited and Translated by Leonard A. Magnus. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co. 1915. pp. 274-280.

- ^ Vasilisa the Beautiful: Russian Fairytales. Edited by Irina Zheleznova. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. 1984. pp. 124-134.

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 128. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9

- ^ Riordan, James. Russian Folk-Tales. Oxford University Press. 2000. pp. 18-26. ISBN 0 19 274536 0.

- ^ Dietrich, Anton. Russische Volksmärchen in den Urschriften gesammelt und ins Deutsche übersetzt. Leipzig: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung. 1831. pp. 171-186. [2]

- ^ Dietrich, Anton, and Jacob Grimm. Russian Popular Tales: Tr. From the German Version of Anton Dietrich’. London: Chapman and Hall, 1857. p. viii. [3]

- ^ Keightley, Thomas. Tales And Popular Fictions: Their Resemblance, And Transmission From Country to Country. London: Whittaker. 1834. pp. 303-336. [4]

- ^ Pedroso, Consiglieri. Portuguese Folk-Tales. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society. 1882. pp. vii.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. The Complete Russian Folktale: v. 4: Russian Wondertales 2 — Tales of Magic and the Supernatural. New York: Routledge. 2019 [2001]. p. 437. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315700076

- ^ Leeming, David Adams. A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-512052-3.

- ^ Rego, José Teixeira. «Os animais agradecidos nos contos populares e o dilúvio». In: Revista de Estudos Históricos, v. 1 (1924), pp. 8-23.

- ^ Tales nr. 165-166: «Емеля-дурак». In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume I, Volume 1. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2014. ISBN 978-1-62846-093-3

- ^ «Emelia the Fool.» In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I, edited by Haney Jack V., 429-38. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. Accessed November 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qhm7n.110.

- ^ Народные русские сказки (Афанасьев)/Емеля-дурак

- ^ Tale nr. 167: «По щучьему веленью». In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev, Volume I, Volume 1. Edited by Jack V. Haney. University Press of Mississippi. 2014. ISBN 978-1-62846-093-3

- ^ «At the Pike’s Command.» In: The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I, edited by Haney Jack V., 439-42. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. Accessed November 17, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qhm7n.111.

- ^ Народные русские сказки (Афанасьев)/По щучьему веленью

Bibliography[edit]

- Lee Wyndham, Russian Tales of Fabulous Beasts and Marvels, “Foolish Emilyan and the Talking Fish”

- Thomas P. Whitney (transl.), In a Certain Kingdom: Twelve Russian Fairy Tales

- Moura Budberg and Amabel Williams-Ellis, Russian Fairy Tales