Всего найдено: 5

Прописная или строчная первая буква в словах «герб», «флаг», «гимн», др.официальных символах, относящихся к конкретному субъекту — краю, городу? Употребление в официальных документах? Например, «герб (или Герб) Красноярского края».

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Эти слова пишутся строчными (в т. ч. в официальных документах): герб Красноярского края. Если речь идет о государственном гербе, гимне, флаге России, то с большой буквы пишется только прилагательное (и только в официальных документах): Государственный герб РФ, Государственный гимн РФ, Государственный флаг РФ.

Как правильно сказать, флаг развевался на здании или над зданием?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Оба варианта возможны.

как правильно пишется:развивается флаг, объясните правописание

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Флаг развЕвается.

Орфографический словарь

развеваться, —ается (к веять)

развиваться, —аюсь, —ается (к развить)

Большой толковый словарь

РАЗВЕВАТЬСЯ, —ается; нсв.

Колыхаться, колебаться в воздухе. Развеваются знамёна. Волосы развеваются на ветру.1. РАЗВИВАТЬСЯ см. 1. Развить.

2. РАЗВИВАТЬСЯ, —аюсь, —аешься; нсв.

1.

Протекать, происходить. Действие романа развивается медленно. События развивались стремительно.

3.

Находиться в процессе перехода из одного состояния в другое, более совершенное. Все развивается от низших форм к высшим. Образ божества развивался от животного к человеку. Дружба часто развивается в любовь.

Слова Храм и Государственный пишутся в тексте с заглавных или с прописных букв?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Заглавная и прописная буква – это одно и то же (большая буква). Маленькая буква называется строчная.

Слово храм ‘архитектурное сооружение’ пишется со строчной, например: храм Всех Святых, храм Христа Спасителя. Прописная буква – в таком контексте: орден рыцарей Храма.

Слово государственный пишется с прописной буквы, если является первым словом в названии органов власти, учреждений, организаций, научных, учебных, зрелищных заведений; наград, символов и т. п, например: Государственная Дума, Государственная Третьяковская галерея, Государственный фонд кинофильмов РФ, Государственный институт русского языка им. А. С. Пушкина, Государственный флаг РФ (в офиц. текстах), Государственная премия. В остальных случаях правильно написание со строчной, например: Единый государственный экзамен, Московский государственный лингвистический университет, государственное унитарное предприятие, органы государственной власти.

Закон «О Государственном Флаге Украины»,и «О Государственном Гимне Украины». Почему флаг со строчной, а Гимн с прописной?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В наименованиях _Государственный флаг РФ_ и _Государственный гимн РФ_ корректно написание со строчной.

| English: State Anthem of the Russian Federation | |

|---|---|

| Госуда́рственный гимн Росси́йской Федера́ции | |

The official arrangement of the Russian national anthem, completed in 2001 |

|

|

National anthem of Russia |

|

| Lyrics | Sergei Mikhalkov, 2000 |

| Music | Alexander Alexandrov, 1939 |

| Adopted | December 25, 2000 (music)[1] December 30, 2000 (lyrics)[2] |

| Preceded by | «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» |

| Audio sample | |

|

Official orchestral vocal recording by the Russian Presidential Orchestra and the Moscow Kremlin Choir

|

Performed by the Russian Presidential Orchestra

Performed by the Russian Presidential Orchestra

The «State Anthem of the Russian Federation«[a] is the national anthem of Russia. It uses the same melody as the «State Anthem of the Soviet Union», composed by Alexander Alexandrov, and new lyrics by Sergey Mikhalkov, who had collaborated with Gabriel El-Registan on the original anthem.[3] From 1944, that earliest version replaced «The Internationale» as a new, more Soviet-centric and Russia-centric Soviet anthem. The same melody, but without any lyrics, was used after 1956. A second version of the lyrics was written by Mikhalkov in 1970 and adopted in 1977, placing less emphasis on World War II and more on the victory of communism, and without mentioning the denounced Stalin by name.

The Russian SFSR was the only constituent republic of the Soviet Union without its own regional anthem. The lyric-free «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya», composed by Mikhail Glinka, was officially adopted in 1990 by the Supreme Soviet of Russia,[4] and confirmed in 1993,[5] after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, by the President of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin. This anthem proved to be unpopular with the Russian public and with many politicians and public figures, because of its tune and lack of lyrics, and consequently its inability to inspire Russian athletes during international competitions.[6] The government sponsored contests to create lyrics for the unpopular anthem, but none of the entries were adopted.

Glinka’s anthem was replaced soon after Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, first took office on 7 May 2000. The federal legislature established and approved the music of the National Anthem of the Soviet Union, with newly written lyrics, in December 2000, and it became the second anthem used by Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The government sponsored a contest to find lyrics, eventually settling upon a new composition by Mikhalkov; according to the government, the lyrics were selected to evoke and eulogize the history and traditions of Russia.[6] Yeltsin criticized Putin for supporting the reintroduction of the Soviet-era national anthem even though opinion polls showed that many Russians favored this decision.[7]

Public perception of the anthem is mixed among Russians. A 2009 poll showed that 56% of respondents felt proud when hearing the national anthem, and that 25% liked it.[8]

Historical anthems

Before «The Prayer of the Russians» (Russian: Моли́тва ру́сских, tr. Molitva russkikh) was chosen as the national anthem of Imperial Russia in 1816,[9] various church hymns and military marches were used to honor the country and the Tsars. Songs used include «Let the Thunder of Victory Rumble!» (Russian: Гром побе́ды, раздава́йся!, tr. Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!) and «How Glorious is our Lord» (Russian: Коль сла́вен, tr. Kol’ slaven). «The Prayer of the Russians» was adopted around 1816, and used lyrics by Vasily Zhukovsky set to the music of the British anthem, «God Save the King».[10] Russia’s anthem was also influenced by the anthems of France and the Netherlands, and by the British patriotic song «Rule, Britannia!».[11]

In 1833, Zhukovsky was asked to set lyrics to a musical composition by Prince Alexei Lvov called «The Russian People’s Prayer», known more commonly as «God Save the Tsar!» (Russian: Бо́же, Царя́ храни́!, tr. Bozhe, Tsarya khrani!). It was well received by Nicholas I, who chose the song to be the next anthem of Imperial Russia. The song resembled a hymn, and its musical style was similar to that of other anthems used by European monarchs. «God Save the Tsar!» was performed for the first time on 8 December 1833, at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. It was later played at the Winter Palace on Christmas Day, by order of Nicholas I. Public singing of the anthem began at opera houses in 1834, but it was not widely known across the Russian Empire until 1837.[12]

«God Save the Tsar!» was used until the February Revolution, when the Russian monarchy was overthrown.[13] Upon the overthrow, in March 1917, the «Worker’s Marseillaise» (Russian: Рабо́чая Марселье́за, tr. Rabochaya Marselyeza), Pyotr Lavrov’s modification of the French anthem «La Marseillaise», was used as an unofficial anthem by the Russian Provisional Government. The modifications Lavrov made to «La Marseillaise» included a change in meter from 2/2 to 4/4 and music harmonization to make it sound more Russian. It was used at governmental meetings, welcoming ceremonies for diplomats and state funerals.[14]

After the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government in the 1917 October Revolution, the anthem of international revolutionary socialism, «L’Internationale» (usually known as «The Internationale» in English), was adopted as the new anthem. The lyrics had been written by Eugène Pottier, and Pierre Degeyter had composed the music in 1871 to honor the creation of the Second Socialist International organization; in 1902, Arkadij Jakovlevich Kots translated Pottier’s lyrics into Russian. Kots also changed the grammatical tense of the song, to make it more decisive in nature.[15] The first major use of the song was at the funeral of victims of the February Revolution in Petrograd. Lenin also wanted «The Internationale» to be played more often because it was more socialist, and could not be confused with the French anthem;[14] other persons in the new Soviet government believed «La Marseillaise» to be too bourgeois.[16] «The Internationale» was used as the state anthem of Soviet Russia from 1918, adopted by the newly created Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, and was used until 1944.[17]

Post-1944 Soviet anthem

Music

1983 Soviet stamp honoring the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Alexandrov

The music of the national anthem, created by Alexander Alexandrov, had previously been incorporated in several hymns and compositions. The music was first used in the Hymn of the Bolshevik Party, created in 1939. When the Comintern was dissolved in 1943, the government argued that «The Internationale», which was historically associated with the Comintern, should be replaced as the National Anthem of the Soviet Union. Alexandrov’s music was chosen as the new anthem by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin after a contest in 1943. Stalin praised the song for fulfilling what a national anthem should be, though he criticized the song’s orchestration.[18]

In response, Alexandrov blamed the problems on Viktor Knushevitsky, who was responsible for orchestrating the entries for the final contest rounds.[18][19] When writing the Bolshevik party anthem, Alexandrov incorporated pieces from the song «Life Has Become Better» (Russian: Жить Ста́ло Лу́чше, tr. Zhit Stálo Lúshe), a musical comedy that he composed.[20] This comedy was based on a slogan Stalin first used in 1935.[21] Over 200 entries were submitted for the anthem contest, including some by famous Soviet composers Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian and Iona Tuskiya.[19] Later, the rejected joint entry by Khachaturian and Shostakovich became Song of the Red Army,[19] and Khachaturian went on to compose the Anthem of the Armenian SSR.[22][23] There was also an entry from Boris Alexandrov, the son of Alexander. His rejected entry, «Long Live our State» (Russian: Да здравствует наша держава), became a popular patriotic song and was adopted as the anthem of Transnistria.[24][25]

During the 2000 debate on the anthem, Boris Gryzlov, the leader of the Unity faction in the Duma, noted that the music which Alexandrov wrote for the Soviet anthem was similar to Vasily Kalinnikov’s 1892 overture, «Bylina».[26] Supporters of the Soviet anthem mentioned this in the various debates held in the Duma on the change of anthem,[27] but there is no evidence that Alexandrov consciously used parts of «Bylina» in his composition.

Lyrics

Lyric writer Sergey Mikhalkov in 2002 meeting President Putin

After selecting the music by Alexandrov for the national anthem, Stalin needed new lyrics. He thought that the song was short and, because of the Great Patriotic War, that it needed a statement about the impending defeat of Germany by the Red Army. The poets Sergey Mikhalkov and Gabriel El-Registan were called to Moscow by one of Stalin’s staffers, and were told to fix the lyrics to Alexandrov’s music. They were instructed to keep the verses the same, but to find a way to change the refrains which described «a Country of Soviets». Because of the difficulty of expressing the concepts of the Great Patriotic War in song, that idea was dropped from the version which El-Registan and Mikhalkov completed overnight. After a few minor changes to emphasize the Soviet Fatherland, Stalin approved the anthem and had it published on 7 November 1943,[28][29] including a line about Stalin «inspir[ing] us to keep the faith with the people».[30] The revised anthem was announced to all of the USSR on January 1, 1944 and became official on March 15, 1944.[31][32]

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet government examined his legacy. The government began the de-Stalinization process, which included downplaying the role of Stalin and moving his corpse from Lenin’s Mausoleum to the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.[33] In addition, the anthem lyrics composed by Mikhalkov and El-Registan were officially scrapped by the Soviet government in 1956.[34] The anthem was still used by the Soviet government, but without any official lyrics. In private, this anthem became known the «Song Without Words».[35] Mikhalkov wrote a new set of lyrics in 1970, but they were not submitted to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet until May 27, 1977. The new lyrics, which eliminated any mention of Stalin, were approved on 1 September, and were made official with the printing of the new Soviet Constitution in October 1977.[32] In the credits for the 1977 lyrics, Mikhalkov was mentioned, but references to El-Registan, who died in 1945, were dropped for unknown reasons.[35]

«Patrioticheskaya Pesnya»

| Anthem of Russia |

|---|

| (1990–2000) |

With the impending collapse of the Soviet Union in early 1990, a new national anthem was needed to help define the reorganized nation and to reject the Soviet past.[36][37] The Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin, was advised to revive «God Save The Tsar» with modifications to the lyrics. However, he instead selected a piece composed by Mikhail Glinka. The piece, known as «Patriotícheskaya Pésnya» (Russian: Патриоти́ческая пе́сня, lit. ‘The Patriotic Song’), was a wordless piano composition discovered after Glinka’s death. «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» was performed in front of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR on November 23, 1990.[38] The song was decreed by the Supreme Soviet to be the new Russian anthem that same day.[4] This anthem was intended to be permanent, which can be seen from the parliamentary draft of the Constitution, approved and drafted by Supreme Soviet, Congress of People’s Deputies and its Constitutional Commission (with latter formally headed by President of Russia). The draft, among other things, reads that:

The National Anthem of the Russian Federation is the Patriotic Song composed by Mikhail Glinka. The text of the National Anthem of the Russian Federation shall be endorsed by the federal law.[39]

However, conflict between President and Congress made passage of that draft less likely: the Congress shifted onto more and more rewriting of the 1978 Russian Constitution, while President pushed forward with new draft Constitution, which doesn’t define state symbols. After 1993 Russian constitutional crisis and just one day before the constitutional referendum (i.e. on December 11, 1993) Yeltsin, then President of the Russian Federation, issued a presidential decree on December 11, 1993, retaining «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» the official anthem for Russia,[32][40] but this decree was provisional, since the draft Constitution (which was passed a day later) explicitly referred this matter to legislation, enacted by parliament. According to Article 70 of the Constitution, state symbols (which are an anthem, flag and coat of arms) required further definition by future legislation.[41] As it was a constitutional matter, it had to be passed by a two-thirds majority in the Duma.[42]

Between 1994 and 1999, many votes were called for in the State Duma to retain «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» as the official anthem of Russia. However, it faced stiff opposition from members of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, who wanted the Soviet anthem restored.[38] Because any anthem had to be approved by a two-thirds supermajority, this disagreement between Duma factions for nearly a decade prevented passage of an anthem.

Call for lyrics

When «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» was used as the national anthem, it had official lyrics but was not accepted.[43] The anthem struck a positive chord for some people because it did not contain elements from the Soviet past, and because the public considered Glinka to be a patriot and a true Russian.[38] However, the lack of lyrics doomed «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya».[44] Various attempts were made to compose lyrics for the anthem, including a contest that allowed any Russian citizen to participate. A committee set up by the government looked at over 6000 entries, and 20 were recorded by an orchestra for a final vote.[45]

The eventual winner was Viktor Radugin’s «Be glorious, Russia!» (Russian: Сла́вься, Росси́я!, tr. Slávsya, Rossíya!).[46] However, none of the lyrics were officially adopted by Yeltsin or the Russian government. One of the reasons that partially explained the lack of lyrics was the original use of Glinka’s composition: the praise of the Tsar and of the Russian Orthodox Church.[47] Other complaints raised about the song were that it was hard to remember, uninspiring, and musically complicated.[48] It was one of the few national anthems that lacked official lyrics during this period.[49] The only other wordless national anthems in the period from 1990 to 2000 were «My Belarusy» of Belarus[50] (until 2002),[51] «Marcha Real» of Spain,[52] and «Intermeco» of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[53]

Modern adoption

The anthem debate intensified in October 2000 when Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, commented that Russian athletes had no words to sing for the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games. Putin brought public attention to the issue and put it before the State Council.[48] CNN also reported that members of the Spartak Moscow football club complained that the wordless anthem «affected their morale and performance».[54] Two years earlier, during the 1998 World Cup, members of the Russian team commented that the wordless anthem failed to inspire «great patriotic effort».[43]

In a November session of the Federation Council, Putin stated that establishing the national symbols (anthem, flag and coat of arms) should be a top priority for the country.[55] Putin pressed for the former Soviet anthem to be selected as the new Russian anthem, but strongly suggested that new lyrics be written. He did not say how much of the old Soviet lyrics should be retained for the new anthem.[43] Putin submitted the bill «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation» to the Duma for their consideration on 4 December.[45] The Duma voted 381–51–1 in favor of adopting Alexandrov’s music as the national anthem on 8 December 2000.[56] Following the vote, a committee was formed and tasked with exploring lyrics for the national anthem. After receiving over 6,000 manuscripts from all sectors of Russian society,[57] the committee selected lyrics by Mikhalkov for the anthem.[45]

Before the official adoption of the lyrics, the Kremlin released a section of the anthem, which made a reference to the flag and coat of arms:

His mighty wings spread above us

The Russian eagle is hovering high

The Fatherland’s tricolor symbol

Is leading Russia’s peoples to victory— Kremlin source[58]

The above lines were omitted from the final version of the lyrics. After the bill was approved by the Federation Council on 20 December,[59] «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation» was signed into law by President Putin on 25 December, officially making Alexandrov’s music the national anthem of Russia. The law was published two days later in the official government gazette Rossiyskaya Gazeta.[60] The new anthem was first performed on 30 December, during a ceremony at the Great Kremlin Palace in Moscow at which Mikhalkov’s lyrics were officially made part of the national anthem.[61][62]

Not everyone agreed with the adoption of the new anthem. Yeltsin argued that Putin should not have changed the anthem merely to «follow blindly the mood of the people».[63] Yeltsin also felt that the restoration of the Soviet anthem was part of a move to reject post-communist reforms that had taken place since Russian independence and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[44] This was one of Yeltsin’s few public criticisms of Putin.[64]

The liberal political party Yabloko stated that the re-adoption of the Soviet anthem «deepened the schism in Russian society».[63] The Soviet anthem was supported by the Communist Party and by Putin himself. The other national symbols used by Russia in 1990, the white-blue-red flag and the double-headed eagle coat of arms, were also given legal approval by Putin in December, thus ending the debate over the national symbols.[65] After all of the symbols were adopted, Putin said on television that this move was needed to heal Russia’s past and to fuse the period of the Soviet Union with Russia’s history. He also stated that, while Russia’s march towards democracy would not be stopped,[66] the rejection of the Soviet era would have left the lives of their mothers and fathers bereft of meaning.[67] It took some time for the Russian people to familiarize themselves with the anthem’s lyrics; athletes were only able to hum along with the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2002 Winter Olympics.[44]

Public perception

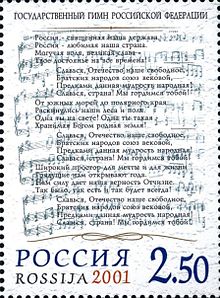

A 2001 stamp released by Russian Post with the lyrics of the new anthem

The Russian national anthem is set to the melody of the Soviet anthem (used since 1944). As a result, there have been several controversies related to its use. Some such as cellist Mstislav Rostropovich vowed not to stand during the anthem.[68][69] Russian cultural figures and government officials were also troubled by Putin’s restoration of the Soviet anthem, even with different lyrics. A former adviser to both Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last President of the Soviet Union, stated that, when «Stalin’s hymn» was used as the national anthem of the Soviet Union, horrific crimes took place.[69]

At the 2007 funeral of Yeltsin, the Russian state anthem was played as his coffin was laid to rest at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow.[64] While it was common to hear the state anthem during state funerals for Soviet civil and military officials,[70] honored citizens of the nation,[71] and Soviet leaders, as was the case for Alexei Kosygin, Leonid Brezhnev,[72] Yuri Andropov[73] and Konstantin Chernenko,[74] Boris Berezovsky, writing in The Daily Telegraph, felt that playing the anthem at Yeltsin’s funeral «abused the man who brought freedom» to the Russian people.[75] The Russian government states that the «solemn music and poetic work» of the anthem, despite its history, is a symbol of unity for the Russian people. Mikhalkov’s words evoke «feelings of patriotism, respect for the history of the country and its system of government.»[60]

In a 2009 poll conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center and publicized just two days before Russia’s flag day (22 August), 56% of respondents stated that they felt proud when hearing the national anthem. However, only 39% could recall the words of the first line of the anthem. This was an increase from 33% in 2007. According to the survey, between 34 and 36% could not identify the anthem’s first line. Overall, only 25% of respondents said they liked the anthem.[8]

In the previous year, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center found out that 56% of Russians felt pride and admiration at the anthem, even though only 40% (up from 19% in 2004) knew the first words of the anthem. It was also noted in the survey that the younger generation was the most familiar with the words.[8]

In September 2009, a line from the lyrics used during Stalin’s rule reappeared at the Moscow Metro station Kurskaya-Koltsevaya: «We were raised by Stalin to be true to the people, inspiring us to feats of labour and heroism.» While groups have threatened legal action to reverse the re-addition of this phrase on a stone banner at the vestibule’s rotunda, it was part of the original design of Kurskaya station and had been removed during de-Stalinization. Most of the commentary surrounding this event focused on the Kremlin’s attempt to «rehabilitate the image» of Stalin by using symbolism sympathetic to or created by him.[76]

The Communist Party strongly supported the restoration of Alexandrov’s melody, but some members proposed other changes to the anthem. In March 2010, Boris Kashin, a CPRF member of the Duma, advocated for the removal of any reference to God in the anthem. Kashin’s suggestion was also supported by Alexander Nikonov, a journalist with SPID-INFO and an avowed atheist. Nikonov argued that religion should be a private matter and should not be used by the state.[77] Kashin found that the cost for making a new anthem recording will be about 120,000 rubles. The Russian Government quickly rejected the request because it lacked statistical data and other findings.[78] Nikonov asked the Constitutional Court of Russia in 2005 if the lyrics were compatible with Russian law.[77]

Regulations

Federal law of 25 December 2000 on the national anthem of Russia

Regulations for the performance of the national anthem are set forth in the law signed by President Putin on 25 December 2000. While a performance of the anthem may include only music, only words, or a combination of both, the anthem must be performed using the official music and words prescribed by law. During official performances of the national anthem, everyone present listens to it standing, and men remove their hats. If the National Anthem is played whilst the flag of the Russian Federation is being raised, the audience will face the flag.[79]

Once a performance has been recorded, it may be used for any purpose, such as in a radio or television broadcast. The anthem may be played for solemn or celebratory occasions, such as the annual Victory Day parade in Moscow,[80] or the funerals of heads of state and other significant figures. When asked about playing the anthem during the Victory Day parades, Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov stated that because of the acoustics of the Red Square, only an orchestra would be used because voices would be swallowed by the echo.[81]

The anthem is mandatory at the swearing-in of the President of Russia, for opening and closing sessions of the Duma and the Federation Council, and for official state ceremonies. It is played on television and radio at the beginning and end of the broadcast day. If programming is continuous, the anthem is played once at 0600 hours, or slightly earlier at 0458 hours. The anthem is also played on New Year’s Eve after the New Year Address by the President. It is played at sporting events in Russia and abroad, according to the protocol of the organisation hosting the games. According to the law, when the anthem is played officially, everybody must stand up (in case the national flag is raising, facing to the flag), men must remove their headgear (in practice, excluding those in military uniform and clergymen). Uniformed personnel must give a military salute when the anthem plays.[1]

The anthem is performed in 4/4 (common time) or in 2/4 in the key of C major, and has a tempo of 76 beats per minute. Using either time signature, the anthem must be played in a solemn and singing manner (Russian: Торжественно and Распевно). The government has released arrangements for orchestras, brass bands and wind bands.[82][83]

According to Russian copyright law, state symbols and signs are not protected by copyright.[84] As such, the anthem’s music and lyrics may be used and modified freely. Although the law calls for the anthem to be performed respectfully and for performers to avoid causing offence, it does not define what constitutes offensive acts or penalties.[1] Standing for the anthem is required by law but the law does not specify a penalty for refusing to stand.[85]

Official lyrics

| Russian original[86][87] (Cyrillic) | Russian Romanization[88] | IPA transcription as sung[b] | English translation[89] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I Припев: II Припев III Припев |

I Pripev: II Pripev III Pripev

|

1 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf]: 2 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf] 3 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf]

|

I Chorus: II Chorus III Chorus |

Notes

- ^ Russian: Госуда́рственный гимн Росси́йской Федера́ции, tr. Gosudárstvennyy gimn Rossíyskoy Federátsii, IPA: [ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ˈɡʲimn rɐˈsʲijskəj fʲɪdʲɪˈratsɨɪ]

- ^ See File:Russian Anthem chorus.ogg, Help:IPA/Russian and Russian phonology.

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Federal Constitutional Law on the National Anthem of the Russian Federation

- ^ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 30.12.2000 N 2110

- ^ «Russia — National Anthem of the Russian Federation». NationalAnthems.me. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ a b «On the National Anthem of the Russian SFSR». Decree of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR. pravo.levonevsky.org. November 23, 1990. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation». Ukase of the President of the Russian Federation. infopravo.by.ru. December 11, 1993.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b «The Russian National Anthem and the problem of National Identity in the 21st Century». The Great Britain – Russia Society. gbrussia.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016.

- ^ «EUROPE – Yeltsin attacks Putin over anthem». BBC News. England, United Kingdom: British Broadcasting Corporation. December 7, 2000. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c «RUSSIAN STATE SYMBOLS: KNOWLEDGE & FEELINGS». Russian Public Opinion Research Center. August 20, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 138

- ^ Bohlman 2004, pp. 157

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 127–130

- ^ Wortman 2006, pp. 158–160

- ^ Studwell 1996, pp. 75

- ^ a b Stites 1991, pp. 87

- ^ Gasparov 2005, pp. 209–210

- ^ Figes & Kolonitskii 1999, pp. 62–63

- ^ Volkov 2008, pp. 34

- ^ a b Fey 2005, pp. 139

- ^ a b c Shostakovich & Volkov 2002, pp. 261–262

- ^ Haynes 2003, pp. 70

- ^ Kubik 1994, pp. 48

- ^ «List of Works». Virtual Museum of Aram Khachaturian. «Aram Khachaturian» International Enlightenment-Cultural Association. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Sandved 1963, pp. 690

- ^ Константинов, С. (June 30, 2001). «Гимн — дело серьёзное». Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ^ «National Anthem». Government of the Pridnestrovskaia Moldavskaia Respublica. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ «Гимн СССР написан в XIX веке Василием Калинниковым и Робертом Шуманом». Лента.Ру (in Russian). Rambler Media Group. December 8, 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Резепов, Олег (December 8, 2000). Выступление Бориса Грызлова при обсуждении законопроекта о государственной символике Российской Федерации (in Russian). Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Montefiore 2005, pp. 460–461

- ^ Volkov, Solomon (December 16, 2000). «Stalin’s Best Tune». The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Keep & Litvin 2004, pp. 41–42

- ^ Soviet Union. PosolʹStvo (U.S) (1944). «USSR Information Bulletin». Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Embassy of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics. 4: 13. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 150

- ^ Brackman 2000, pp. 412

- ^ Wesson 1978, pp. 265

- ^ a b Ioffe 1988, pp. 331

- ^ Kuhlmann 2003, pp. 162–163

- ^ Eckel, Mike (April 26, 2007). «Yeltsin Laid To Rest In Elite Moscow Cemetery». KSDK NBC. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c Service 2006, pp. 198–199

- ^ «Draft Constitution of the Russian Federation» (PDF). Venice Commission. November 13, 1992(as CDL(92)52). Article 130 (3)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 11.12.93 N 2127

- ^ «Constitution of the Russian Federation». Government of the Russian Federation. December 12, 1993. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ «Russians to hail their ‘holy country’«. CNN.com. CNN. December 30, 2000. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c Franklin et al. 2004, pp. 116

- ^ a b c Sakwa 2008, pp. 224

- ^ a b c «National Anthem». Russia’s State Symbols. RIA Novosti. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Владимирова, Бориса (January 23, 2002). «Неудавшийся гимн: Имя страны – Россия!» [Unsuccessful Anthem: Our State — Russia!]. Московской правде (in Russian). Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Khazanov 1998, pp. 131

- ^ a b Zolotov, Andrei (December 1, 2000). «Russian Orthodox Church Approves as Putin Decides to Sing to a Soviet Tune». Christianity Today Magazine. Christianity Today International. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Waxman, Ginor & Ginor 1998, pp. 170

- ^ Korosteleva, Lawson & Marsh 2002, pp. 118

- ^ «Указ № 350 ад 2 ліпеня 2002 г. «Аб Дзяржаўным гімне Рэспублікі Беларусь»» [Decree No. 350 of July 2nd, 2002 «On the National Anthem of the Republic of Belarus»]. Указу Прэзідэнта Рэспублікі Беларусь (in Belarusian). Пресс-служба Президента Республики Беларусь. July 2, 2002. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Spain: National Symbols: National Anthem». Spain Today. Government of Spain. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Himna Bosne i Hercegovine» (in Bosnian). Ministarstvo vanjskih poslova Bosne i Hercegovine. 2001. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Duma approves old Soviet anthem». CNN.com. CNN. December 8, 2000. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Shevtsova 2005, pp. 123

- ^ «Russian Duma Approves National Anthem Bill». People’s Daily Online. People’s Daily. December 8, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ «Guide to Russia – National Anthem of the Russian Federation». Russia Today. Strana.ru. September 18, 2002. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Shukshin, Andrei (November 30, 2000). «Putin Sings Praises of Old-New Russian Anthem». ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. p. 2. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 152

- ^ a b Государственный гимн России (in Russian). Администрация Приморского края. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ «State Insignia -The National Anthem». President of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Russia Unveils New National Anthem Joining the Old Soviet Tune to the Older, Unsoviet God». The New York Times. December 31, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ a b «Duma approves Soviet anthem». BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. December 8, 2000. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Blomfield, Adrian (April 26, 2007). «In death, Yeltsin scorns symbols of Soviet era». Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Bova 2003, pp. 24

- ^ Nichols 2001, pp. 158

- ^ Hunter 2004, pp. 195

- ^ The Jamestown Foundation (December 7, 2000). «Yeltsin «Categorically Against» Restoring Soviet Anthem». Monitor. 6 (228).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Banerji 2008, pp. 275–276

- ^ Embassy of the USSR (1945). «Last Honors Paid Marshal Shaposhnikov». USSR Information Bulletin. Embassy of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics. 5: 5. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Condee 1995, pp. 44

- ^ Scoon 2003, pp. 77

- ^

- ^ «Soviets: Ending an Era of Drift». Time. Time Magazine. March 25, 1985. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Berezovsky, Boris (May 15, 2007). «Why modern Russia is a state of denial». Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (September 5, 2009). «Josef Stalin ‘returns’ to Moscow metro». Telegraph.co.uk. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- ^ a b «Notorious journalist backs up the idea to take out word «God» from Russian anthem». Interfax-Religion. Interfax. March 30, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ «God Beats Communists in Russian National Anthem». Komsomolskaya Pravda. PRAVDA.Ru. March 30, 2010. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ «State Insignia». State Insignia. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ «Russia marks Victory Day with parade on Red Square». People’s Daily. People’s Daily Online. May 9, 2005. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ «Defence Minister Commands ‘Onwards to Victory!’«. Rossiiskaya Gazeta. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Гимн Российской Федерации [National anthem of the Russian Federation] (in Russian). Official Site of the President of Russia. 2009. Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Музыкальная редакция: Государственного гимна Российской Федерации [Musical Notation — National Anthem of the Russian Federation] (in Russian). Government of the Russian Federation. 2000. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ Part IV of Civil Code No. 230-FZ of the Russian Federation. Article 1259. Objects of Copyright

- ^ Shevtsova 2005, pp. 144

- ^ «Государственные символы России». www.gov.ru. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ «Государственная символика». flag.kremlin.ru (in Russian). Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, T. Pedersen. «Transliteration of Russian» (PDF). transliteration.eki.ee.

- ^ «State Symbols of the Russian Federation». Consulate-General of the Russian Federation in Montreal, Canada. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

Bibliography

- Banerji, Arup (2008). Writing History in the Soviet Union: Making the Past Work. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-81-87358-37-4.

- Bohlman, Philip Vilas (2004). The Music of European Nationalism: Cultural Identity and Modern History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-363-2.

- Bova, Russell (2003). Russia and Western Civilization. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0977-9.

- Brackman, Roman (2000). The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5050-0.

- Condee, Nancy (1995). Soviet Hieroglyphics: Visual Culture in Late Twentieth-Century Russia. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31402-X.

- Fey, Laurel E. (2005). Shostakovich: A Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518251-4.

- Figes, Orlando; Kolonitskii, Boris (1999). Interpreting the Russian Revolution: the language and symbols of 1917. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08106-0.

- Franklin, Simon; Widdis, Emma; Jahn, Hubertus; Cross, Anthony; Frolova-Walker, Marina; Gasparov, Boris; Kelly, Catriona; Hughes, Lindsey; Sandler, Stephanie (2004). National identity in Russian culture: an introduction. University of Cambridge Press. ISBN 0-521-83926-2.

- Gasparov, Boris (2005). Five Operas and a Symphony: Word and Music in Russian Culture. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10650-3.

- Голованова, Марина П.; Шергин, В. С. (2003). Государственные символы России (State Symbols of Russia) (in Russian). Росмэн-Пресс. ISBN 5-353-01286-0.

- Haynes, John (2003). New Soviet Man. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6238-1.

- Hunter, Shireen (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1283-0.

- Ioffe, Olimpiad Solomonovich (1988). «Chapter IV: Law of Creative Activity». Soviet Civil Law. BRILL. 36 (36). ISBN 90-247-3676-5. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Keep, John; Litvin, Alter (2004). Stalinism: Russian and Western Views at the Turn of the Millennium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35109-6.

- Khazanov, Anatoly M. (1998). «Ethnic Nationalism in the Russian Federation». In Graubard, Stephen (ed.). A New Europe for the Old?. Transaction Publishers. pp. 121–142. doi:10.4324/9781351308809-6. ISBN 0-7658-0465-4. Originally published as a special issue of Daedalus. 126 (3): 121–142. 1997. ISSN 0011-5266 JSTOR 20027444

- Korosteleva, Elena; Lawson, Colin; Marsh, Rosalind (2002). Contemporary Belarus Between Democracy and Dictatorship. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1613-5.

- Kubik, Jan (1994). The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01084-7.

- Kuhlmann, Jurgen (2003). Military and Society in 21st Century Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Lit Verlag. ISBN 3-8258-4449-8.

- Montefiore, Simon (2005). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-7678-9.

- Nichols, Thomas (2001). The Russian Presidency: Society and Politics in the Second Russian Republic. Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. ISBN 0-312-29337-2.

- Sandved, Kjell Bloch (1963). The World of Music, Volume 2. Abradale Press.

- Sakwa, Richard (2008). Russian Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41528-6.

- Scoon, Paul (2003). Survival for Service: My Experiences as Governor General of Grenada. Macmillan Caribbean. ISBN 0-333-97064-0.

- Service, Robert (2006). Russia: Experiment with a People. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02108-8.

- Shevtsova, Lilia (2005). Putin’s Russia. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. ISBN 0-87003-213-5.

- Shostakovich, Dimitri; Volkov, Solomon (2002). Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-87910-998-1.

- Соболева, Надежда; Казакевич, А. Н (2006). Символы и святыни Российской державы [The Symbols and Shrines of Russian Power] (in Russian). ОЛМА Медиа Групп. ISBN 5-373-00604-1.

- Stites, Richard (1991). Revolutionary Dreams: Utopian Vision and Experimental Life in the Russian Revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505537-3.

- Studwell, William Emmett (1996). The National and Religious Song Reader: Patriotic, Traditional, and Sacred Songs from Around the World. Routledge. ISBN 0-7890-0099-7.

- Volkov, Solomon (2008). The Magical Chorus: A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn. tr. Antonina W. Bouis. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-4272-2.

- Wesson, Robert (1978). Lenin’s Legacy. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-6922-6.

- Waxman, Mordecai; Ginor, Tseviyah Ben-Yosef; Ginor, Zvia (1998). Yakar le’Mordecai. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 0-88125-632-3.

- Wortman, Richard (2006). Scenarios of Power: Myth and Ceremony in Russian Monarchy from Peter the Great to the Abdication of Nicholas II. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12374-5.

Legislation

- «Указ Президента РФ от 11.12.93 N 2127 «О Государственном гимне Российской Федерации»» [Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 11.12.1993, Number 2127 «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation»]. Указ Президента Российской Федерации (in Russian). Правительство Российской Федерации. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011.

- «Federal Constitutional Law of the Russian Federation – About the National Anthem of the Russian Federation». Government of the Russian Federation. December 25, 2000. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- «Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 30.12.2000 N 2110» [Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 30.12.2000] (in Russian). Kremlin.ru. December 30, 2000. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- «Part IV of Civil Code No. 230-FZ of the Russian Federation. Article 1259. Objects of Copyright» (in Russian). Правительство Российской Федерации. December 18, 2006. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- (in Russian) Download at Government of Russia’s website

- President of Russia State Insignia – National Anthem

- Download Arrangement for symphony orchestra and mixed choir

- Download Arrangement for wind orchestra

- Музыкальное обеспечение парада на Красной площади возложено на не имеющий мировых аналогов Сводный военный оркестр

- Военные песни и Гимны

- Музыка парада 1945 г.

- Александров А.В. — Гимн Российской Федерации (Сводный оркестр Министерства обороны), First Link

- Александров А.В. — Гимн Российской Федерации (Сводный оркестр Министерства обороны), Second Link

- Russian Anthems museum – an extensive collection of audio recordings including some 30 recordings of the current anthem and recordings of other works mentioned in this article

- Haunting Europe – an overview, with audio, of the history of the Russian and Soviet national anthems throughout the twentieth century

- Streaming audio, lyrics and information about the National Anthem of Russia

- The National Anthem of Russia – Rock Version

- The National Anthem of Russia – Soul Version

| English: State Anthem of the Russian Federation | |

|---|---|

| Госуда́рственный гимн Росси́йской Федера́ции | |

The official arrangement of the Russian national anthem, completed in 2001 |

|

|

National anthem of Russia |

|

| Lyrics | Sergei Mikhalkov, 2000 |

| Music | Alexander Alexandrov, 1939 |

| Adopted | December 25, 2000 (music)[1] December 30, 2000 (lyrics)[2] |

| Preceded by | «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» |

| Audio sample | |

|

Official orchestral vocal recording by the Russian Presidential Orchestra and the Moscow Kremlin Choir

|

Performed by the Russian Presidential Orchestra

Performed by the Russian Presidential Orchestra

The «State Anthem of the Russian Federation«[a] is the national anthem of Russia. It uses the same melody as the «State Anthem of the Soviet Union», composed by Alexander Alexandrov, and new lyrics by Sergey Mikhalkov, who had collaborated with Gabriel El-Registan on the original anthem.[3] From 1944, that earliest version replaced «The Internationale» as a new, more Soviet-centric and Russia-centric Soviet anthem. The same melody, but without any lyrics, was used after 1956. A second version of the lyrics was written by Mikhalkov in 1970 and adopted in 1977, placing less emphasis on World War II and more on the victory of communism, and without mentioning the denounced Stalin by name.

The Russian SFSR was the only constituent republic of the Soviet Union without its own regional anthem. The lyric-free «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya», composed by Mikhail Glinka, was officially adopted in 1990 by the Supreme Soviet of Russia,[4] and confirmed in 1993,[5] after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, by the President of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin. This anthem proved to be unpopular with the Russian public and with many politicians and public figures, because of its tune and lack of lyrics, and consequently its inability to inspire Russian athletes during international competitions.[6] The government sponsored contests to create lyrics for the unpopular anthem, but none of the entries were adopted.

Glinka’s anthem was replaced soon after Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, first took office on 7 May 2000. The federal legislature established and approved the music of the National Anthem of the Soviet Union, with newly written lyrics, in December 2000, and it became the second anthem used by Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The government sponsored a contest to find lyrics, eventually settling upon a new composition by Mikhalkov; according to the government, the lyrics were selected to evoke and eulogize the history and traditions of Russia.[6] Yeltsin criticized Putin for supporting the reintroduction of the Soviet-era national anthem even though opinion polls showed that many Russians favored this decision.[7]

Public perception of the anthem is mixed among Russians. A 2009 poll showed that 56% of respondents felt proud when hearing the national anthem, and that 25% liked it.[8]

Historical anthems

Before «The Prayer of the Russians» (Russian: Моли́тва ру́сских, tr. Molitva russkikh) was chosen as the national anthem of Imperial Russia in 1816,[9] various church hymns and military marches were used to honor the country and the Tsars. Songs used include «Let the Thunder of Victory Rumble!» (Russian: Гром побе́ды, раздава́йся!, tr. Grom pobedy, razdavaysya!) and «How Glorious is our Lord» (Russian: Коль сла́вен, tr. Kol’ slaven). «The Prayer of the Russians» was adopted around 1816, and used lyrics by Vasily Zhukovsky set to the music of the British anthem, «God Save the King».[10] Russia’s anthem was also influenced by the anthems of France and the Netherlands, and by the British patriotic song «Rule, Britannia!».[11]

In 1833, Zhukovsky was asked to set lyrics to a musical composition by Prince Alexei Lvov called «The Russian People’s Prayer», known more commonly as «God Save the Tsar!» (Russian: Бо́же, Царя́ храни́!, tr. Bozhe, Tsarya khrani!). It was well received by Nicholas I, who chose the song to be the next anthem of Imperial Russia. The song resembled a hymn, and its musical style was similar to that of other anthems used by European monarchs. «God Save the Tsar!» was performed for the first time on 8 December 1833, at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow. It was later played at the Winter Palace on Christmas Day, by order of Nicholas I. Public singing of the anthem began at opera houses in 1834, but it was not widely known across the Russian Empire until 1837.[12]

«God Save the Tsar!» was used until the February Revolution, when the Russian monarchy was overthrown.[13] Upon the overthrow, in March 1917, the «Worker’s Marseillaise» (Russian: Рабо́чая Марселье́за, tr. Rabochaya Marselyeza), Pyotr Lavrov’s modification of the French anthem «La Marseillaise», was used as an unofficial anthem by the Russian Provisional Government. The modifications Lavrov made to «La Marseillaise» included a change in meter from 2/2 to 4/4 and music harmonization to make it sound more Russian. It was used at governmental meetings, welcoming ceremonies for diplomats and state funerals.[14]

After the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government in the 1917 October Revolution, the anthem of international revolutionary socialism, «L’Internationale» (usually known as «The Internationale» in English), was adopted as the new anthem. The lyrics had been written by Eugène Pottier, and Pierre Degeyter had composed the music in 1871 to honor the creation of the Second Socialist International organization; in 1902, Arkadij Jakovlevich Kots translated Pottier’s lyrics into Russian. Kots also changed the grammatical tense of the song, to make it more decisive in nature.[15] The first major use of the song was at the funeral of victims of the February Revolution in Petrograd. Lenin also wanted «The Internationale» to be played more often because it was more socialist, and could not be confused with the French anthem;[14] other persons in the new Soviet government believed «La Marseillaise» to be too bourgeois.[16] «The Internationale» was used as the state anthem of Soviet Russia from 1918, adopted by the newly created Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922, and was used until 1944.[17]

Post-1944 Soviet anthem

Music

1983 Soviet stamp honoring the 100th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Alexandrov

The music of the national anthem, created by Alexander Alexandrov, had previously been incorporated in several hymns and compositions. The music was first used in the Hymn of the Bolshevik Party, created in 1939. When the Comintern was dissolved in 1943, the government argued that «The Internationale», which was historically associated with the Comintern, should be replaced as the National Anthem of the Soviet Union. Alexandrov’s music was chosen as the new anthem by the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin after a contest in 1943. Stalin praised the song for fulfilling what a national anthem should be, though he criticized the song’s orchestration.[18]

In response, Alexandrov blamed the problems on Viktor Knushevitsky, who was responsible for orchestrating the entries for the final contest rounds.[18][19] When writing the Bolshevik party anthem, Alexandrov incorporated pieces from the song «Life Has Become Better» (Russian: Жить Ста́ло Лу́чше, tr. Zhit Stálo Lúshe), a musical comedy that he composed.[20] This comedy was based on a slogan Stalin first used in 1935.[21] Over 200 entries were submitted for the anthem contest, including some by famous Soviet composers Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian and Iona Tuskiya.[19] Later, the rejected joint entry by Khachaturian and Shostakovich became Song of the Red Army,[19] and Khachaturian went on to compose the Anthem of the Armenian SSR.[22][23] There was also an entry from Boris Alexandrov, the son of Alexander. His rejected entry, «Long Live our State» (Russian: Да здравствует наша держава), became a popular patriotic song and was adopted as the anthem of Transnistria.[24][25]

During the 2000 debate on the anthem, Boris Gryzlov, the leader of the Unity faction in the Duma, noted that the music which Alexandrov wrote for the Soviet anthem was similar to Vasily Kalinnikov’s 1892 overture, «Bylina».[26] Supporters of the Soviet anthem mentioned this in the various debates held in the Duma on the change of anthem,[27] but there is no evidence that Alexandrov consciously used parts of «Bylina» in his composition.

Lyrics

Lyric writer Sergey Mikhalkov in 2002 meeting President Putin

After selecting the music by Alexandrov for the national anthem, Stalin needed new lyrics. He thought that the song was short and, because of the Great Patriotic War, that it needed a statement about the impending defeat of Germany by the Red Army. The poets Sergey Mikhalkov and Gabriel El-Registan were called to Moscow by one of Stalin’s staffers, and were told to fix the lyrics to Alexandrov’s music. They were instructed to keep the verses the same, but to find a way to change the refrains which described «a Country of Soviets». Because of the difficulty of expressing the concepts of the Great Patriotic War in song, that idea was dropped from the version which El-Registan and Mikhalkov completed overnight. After a few minor changes to emphasize the Soviet Fatherland, Stalin approved the anthem and had it published on 7 November 1943,[28][29] including a line about Stalin «inspir[ing] us to keep the faith with the people».[30] The revised anthem was announced to all of the USSR on January 1, 1944 and became official on March 15, 1944.[31][32]

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet government examined his legacy. The government began the de-Stalinization process, which included downplaying the role of Stalin and moving his corpse from Lenin’s Mausoleum to the Kremlin Wall Necropolis.[33] In addition, the anthem lyrics composed by Mikhalkov and El-Registan were officially scrapped by the Soviet government in 1956.[34] The anthem was still used by the Soviet government, but without any official lyrics. In private, this anthem became known the «Song Without Words».[35] Mikhalkov wrote a new set of lyrics in 1970, but they were not submitted to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet until May 27, 1977. The new lyrics, which eliminated any mention of Stalin, were approved on 1 September, and were made official with the printing of the new Soviet Constitution in October 1977.[32] In the credits for the 1977 lyrics, Mikhalkov was mentioned, but references to El-Registan, who died in 1945, were dropped for unknown reasons.[35]

«Patrioticheskaya Pesnya»

| Anthem of Russia |

|---|

| (1990–2000) |

With the impending collapse of the Soviet Union in early 1990, a new national anthem was needed to help define the reorganized nation and to reject the Soviet past.[36][37] The Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin, was advised to revive «God Save The Tsar» with modifications to the lyrics. However, he instead selected a piece composed by Mikhail Glinka. The piece, known as «Patriotícheskaya Pésnya» (Russian: Патриоти́ческая пе́сня, lit. ‘The Patriotic Song’), was a wordless piano composition discovered after Glinka’s death. «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» was performed in front of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR on November 23, 1990.[38] The song was decreed by the Supreme Soviet to be the new Russian anthem that same day.[4] This anthem was intended to be permanent, which can be seen from the parliamentary draft of the Constitution, approved and drafted by Supreme Soviet, Congress of People’s Deputies and its Constitutional Commission (with latter formally headed by President of Russia). The draft, among other things, reads that:

The National Anthem of the Russian Federation is the Patriotic Song composed by Mikhail Glinka. The text of the National Anthem of the Russian Federation shall be endorsed by the federal law.[39]

However, conflict between President and Congress made passage of that draft less likely: the Congress shifted onto more and more rewriting of the 1978 Russian Constitution, while President pushed forward with new draft Constitution, which doesn’t define state symbols. After 1993 Russian constitutional crisis and just one day before the constitutional referendum (i.e. on December 11, 1993) Yeltsin, then President of the Russian Federation, issued a presidential decree on December 11, 1993, retaining «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» the official anthem for Russia,[32][40] but this decree was provisional, since the draft Constitution (which was passed a day later) explicitly referred this matter to legislation, enacted by parliament. According to Article 70 of the Constitution, state symbols (which are an anthem, flag and coat of arms) required further definition by future legislation.[41] As it was a constitutional matter, it had to be passed by a two-thirds majority in the Duma.[42]

Between 1994 and 1999, many votes were called for in the State Duma to retain «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» as the official anthem of Russia. However, it faced stiff opposition from members of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, who wanted the Soviet anthem restored.[38] Because any anthem had to be approved by a two-thirds supermajority, this disagreement between Duma factions for nearly a decade prevented passage of an anthem.

Call for lyrics

When «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya» was used as the national anthem, it had official lyrics but was not accepted.[43] The anthem struck a positive chord for some people because it did not contain elements from the Soviet past, and because the public considered Glinka to be a patriot and a true Russian.[38] However, the lack of lyrics doomed «Patrioticheskaya Pesnya».[44] Various attempts were made to compose lyrics for the anthem, including a contest that allowed any Russian citizen to participate. A committee set up by the government looked at over 6000 entries, and 20 were recorded by an orchestra for a final vote.[45]

The eventual winner was Viktor Radugin’s «Be glorious, Russia!» (Russian: Сла́вься, Росси́я!, tr. Slávsya, Rossíya!).[46] However, none of the lyrics were officially adopted by Yeltsin or the Russian government. One of the reasons that partially explained the lack of lyrics was the original use of Glinka’s composition: the praise of the Tsar and of the Russian Orthodox Church.[47] Other complaints raised about the song were that it was hard to remember, uninspiring, and musically complicated.[48] It was one of the few national anthems that lacked official lyrics during this period.[49] The only other wordless national anthems in the period from 1990 to 2000 were «My Belarusy» of Belarus[50] (until 2002),[51] «Marcha Real» of Spain,[52] and «Intermeco» of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[53]

Modern adoption

The anthem debate intensified in October 2000 when Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, commented that Russian athletes had no words to sing for the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games. Putin brought public attention to the issue and put it before the State Council.[48] CNN also reported that members of the Spartak Moscow football club complained that the wordless anthem «affected their morale and performance».[54] Two years earlier, during the 1998 World Cup, members of the Russian team commented that the wordless anthem failed to inspire «great patriotic effort».[43]

In a November session of the Federation Council, Putin stated that establishing the national symbols (anthem, flag and coat of arms) should be a top priority for the country.[55] Putin pressed for the former Soviet anthem to be selected as the new Russian anthem, but strongly suggested that new lyrics be written. He did not say how much of the old Soviet lyrics should be retained for the new anthem.[43] Putin submitted the bill «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation» to the Duma for their consideration on 4 December.[45] The Duma voted 381–51–1 in favor of adopting Alexandrov’s music as the national anthem on 8 December 2000.[56] Following the vote, a committee was formed and tasked with exploring lyrics for the national anthem. After receiving over 6,000 manuscripts from all sectors of Russian society,[57] the committee selected lyrics by Mikhalkov for the anthem.[45]

Before the official adoption of the lyrics, the Kremlin released a section of the anthem, which made a reference to the flag and coat of arms:

His mighty wings spread above us

The Russian eagle is hovering high

The Fatherland’s tricolor symbol

Is leading Russia’s peoples to victory— Kremlin source[58]

The above lines were omitted from the final version of the lyrics. After the bill was approved by the Federation Council on 20 December,[59] «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation» was signed into law by President Putin on 25 December, officially making Alexandrov’s music the national anthem of Russia. The law was published two days later in the official government gazette Rossiyskaya Gazeta.[60] The new anthem was first performed on 30 December, during a ceremony at the Great Kremlin Palace in Moscow at which Mikhalkov’s lyrics were officially made part of the national anthem.[61][62]

Not everyone agreed with the adoption of the new anthem. Yeltsin argued that Putin should not have changed the anthem merely to «follow blindly the mood of the people».[63] Yeltsin also felt that the restoration of the Soviet anthem was part of a move to reject post-communist reforms that had taken place since Russian independence and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[44] This was one of Yeltsin’s few public criticisms of Putin.[64]

The liberal political party Yabloko stated that the re-adoption of the Soviet anthem «deepened the schism in Russian society».[63] The Soviet anthem was supported by the Communist Party and by Putin himself. The other national symbols used by Russia in 1990, the white-blue-red flag and the double-headed eagle coat of arms, were also given legal approval by Putin in December, thus ending the debate over the national symbols.[65] After all of the symbols were adopted, Putin said on television that this move was needed to heal Russia’s past and to fuse the period of the Soviet Union with Russia’s history. He also stated that, while Russia’s march towards democracy would not be stopped,[66] the rejection of the Soviet era would have left the lives of their mothers and fathers bereft of meaning.[67] It took some time for the Russian people to familiarize themselves with the anthem’s lyrics; athletes were only able to hum along with the anthem during the medal ceremonies at the 2002 Winter Olympics.[44]

Public perception

A 2001 stamp released by Russian Post with the lyrics of the new anthem

The Russian national anthem is set to the melody of the Soviet anthem (used since 1944). As a result, there have been several controversies related to its use. Some such as cellist Mstislav Rostropovich vowed not to stand during the anthem.[68][69] Russian cultural figures and government officials were also troubled by Putin’s restoration of the Soviet anthem, even with different lyrics. A former adviser to both Yeltsin and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last President of the Soviet Union, stated that, when «Stalin’s hymn» was used as the national anthem of the Soviet Union, horrific crimes took place.[69]

At the 2007 funeral of Yeltsin, the Russian state anthem was played as his coffin was laid to rest at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow.[64] While it was common to hear the state anthem during state funerals for Soviet civil and military officials,[70] honored citizens of the nation,[71] and Soviet leaders, as was the case for Alexei Kosygin, Leonid Brezhnev,[72] Yuri Andropov[73] and Konstantin Chernenko,[74] Boris Berezovsky, writing in The Daily Telegraph, felt that playing the anthem at Yeltsin’s funeral «abused the man who brought freedom» to the Russian people.[75] The Russian government states that the «solemn music and poetic work» of the anthem, despite its history, is a symbol of unity for the Russian people. Mikhalkov’s words evoke «feelings of patriotism, respect for the history of the country and its system of government.»[60]

In a 2009 poll conducted by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center and publicized just two days before Russia’s flag day (22 August), 56% of respondents stated that they felt proud when hearing the national anthem. However, only 39% could recall the words of the first line of the anthem. This was an increase from 33% in 2007. According to the survey, between 34 and 36% could not identify the anthem’s first line. Overall, only 25% of respondents said they liked the anthem.[8]

In the previous year, the Russian Public Opinion Research Center found out that 56% of Russians felt pride and admiration at the anthem, even though only 40% (up from 19% in 2004) knew the first words of the anthem. It was also noted in the survey that the younger generation was the most familiar with the words.[8]

In September 2009, a line from the lyrics used during Stalin’s rule reappeared at the Moscow Metro station Kurskaya-Koltsevaya: «We were raised by Stalin to be true to the people, inspiring us to feats of labour and heroism.» While groups have threatened legal action to reverse the re-addition of this phrase on a stone banner at the vestibule’s rotunda, it was part of the original design of Kurskaya station and had been removed during de-Stalinization. Most of the commentary surrounding this event focused on the Kremlin’s attempt to «rehabilitate the image» of Stalin by using symbolism sympathetic to or created by him.[76]

The Communist Party strongly supported the restoration of Alexandrov’s melody, but some members proposed other changes to the anthem. In March 2010, Boris Kashin, a CPRF member of the Duma, advocated for the removal of any reference to God in the anthem. Kashin’s suggestion was also supported by Alexander Nikonov, a journalist with SPID-INFO and an avowed atheist. Nikonov argued that religion should be a private matter and should not be used by the state.[77] Kashin found that the cost for making a new anthem recording will be about 120,000 rubles. The Russian Government quickly rejected the request because it lacked statistical data and other findings.[78] Nikonov asked the Constitutional Court of Russia in 2005 if the lyrics were compatible with Russian law.[77]

Regulations

Federal law of 25 December 2000 on the national anthem of Russia

Regulations for the performance of the national anthem are set forth in the law signed by President Putin on 25 December 2000. While a performance of the anthem may include only music, only words, or a combination of both, the anthem must be performed using the official music and words prescribed by law. During official performances of the national anthem, everyone present listens to it standing, and men remove their hats. If the National Anthem is played whilst the flag of the Russian Federation is being raised, the audience will face the flag.[79]

Once a performance has been recorded, it may be used for any purpose, such as in a radio or television broadcast. The anthem may be played for solemn or celebratory occasions, such as the annual Victory Day parade in Moscow,[80] or the funerals of heads of state and other significant figures. When asked about playing the anthem during the Victory Day parades, Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov stated that because of the acoustics of the Red Square, only an orchestra would be used because voices would be swallowed by the echo.[81]

The anthem is mandatory at the swearing-in of the President of Russia, for opening and closing sessions of the Duma and the Federation Council, and for official state ceremonies. It is played on television and radio at the beginning and end of the broadcast day. If programming is continuous, the anthem is played once at 0600 hours, or slightly earlier at 0458 hours. The anthem is also played on New Year’s Eve after the New Year Address by the President. It is played at sporting events in Russia and abroad, according to the protocol of the organisation hosting the games. According to the law, when the anthem is played officially, everybody must stand up (in case the national flag is raising, facing to the flag), men must remove their headgear (in practice, excluding those in military uniform and clergymen). Uniformed personnel must give a military salute when the anthem plays.[1]

The anthem is performed in 4/4 (common time) or in 2/4 in the key of C major, and has a tempo of 76 beats per minute. Using either time signature, the anthem must be played in a solemn and singing manner (Russian: Торжественно and Распевно). The government has released arrangements for orchestras, brass bands and wind bands.[82][83]

According to Russian copyright law, state symbols and signs are not protected by copyright.[84] As such, the anthem’s music and lyrics may be used and modified freely. Although the law calls for the anthem to be performed respectfully and for performers to avoid causing offence, it does not define what constitutes offensive acts or penalties.[1] Standing for the anthem is required by law but the law does not specify a penalty for refusing to stand.[85]

Official lyrics

| Russian original[86][87] (Cyrillic) | Russian Romanization[88] | IPA transcription as sung[b] | English translation[89] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I Припев: II Припев III Припев |

I Pripev: II Pripev III Pripev

|

1 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf]: 2 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf] 3 [prʲɪ.ˈpʲɛf]

|

I Chorus: II Chorus III Chorus |

Notes

- ^ Russian: Госуда́рственный гимн Росси́йской Федера́ции, tr. Gosudárstvennyy gimn Rossíyskoy Federátsii, IPA: [ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)ɨj ˈɡʲimn rɐˈsʲijskəj fʲɪdʲɪˈratsɨɪ]

- ^ See File:Russian Anthem chorus.ogg, Help:IPA/Russian and Russian phonology.

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Federal Constitutional Law on the National Anthem of the Russian Federation

- ^ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 30.12.2000 N 2110

- ^ «Russia — National Anthem of the Russian Federation». NationalAnthems.me. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ a b «On the National Anthem of the Russian SFSR». Decree of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR. pravo.levonevsky.org. November 23, 1990. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ «On the National Anthem of the Russian Federation». Ukase of the President of the Russian Federation. infopravo.by.ru. December 11, 1993.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b «The Russian National Anthem and the problem of National Identity in the 21st Century». The Great Britain – Russia Society. gbrussia.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2016.

- ^ «EUROPE – Yeltsin attacks Putin over anthem». BBC News. England, United Kingdom: British Broadcasting Corporation. December 7, 2000. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c «RUSSIAN STATE SYMBOLS: KNOWLEDGE & FEELINGS». Russian Public Opinion Research Center. August 20, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 138

- ^ Bohlman 2004, pp. 157

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 127–130

- ^ Wortman 2006, pp. 158–160

- ^ Studwell 1996, pp. 75

- ^ a b Stites 1991, pp. 87

- ^ Gasparov 2005, pp. 209–210

- ^ Figes & Kolonitskii 1999, pp. 62–63

- ^ Volkov 2008, pp. 34

- ^ a b Fey 2005, pp. 139

- ^ a b c Shostakovich & Volkov 2002, pp. 261–262

- ^ Haynes 2003, pp. 70

- ^ Kubik 1994, pp. 48

- ^ «List of Works». Virtual Museum of Aram Khachaturian. «Aram Khachaturian» International Enlightenment-Cultural Association. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Sandved 1963, pp. 690

- ^ Константинов, С. (June 30, 2001). «Гимн — дело серьёзное». Nezavisimaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ^ «National Anthem». Government of the Pridnestrovskaia Moldavskaia Respublica. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ «Гимн СССР написан в XIX веке Василием Калинниковым и Робертом Шуманом». Лента.Ру (in Russian). Rambler Media Group. December 8, 2000. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Резепов, Олег (December 8, 2000). Выступление Бориса Грызлова при обсуждении законопроекта о государственной символике Российской Федерации (in Russian). Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Montefiore 2005, pp. 460–461

- ^ Volkov, Solomon (December 16, 2000). «Stalin’s Best Tune». The New York Times. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Keep & Litvin 2004, pp. 41–42

- ^ Soviet Union. PosolʹStvo (U.S) (1944). «USSR Information Bulletin». Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Embassy of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics. 4: 13. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 150

- ^ Brackman 2000, pp. 412

- ^ Wesson 1978, pp. 265

- ^ a b Ioffe 1988, pp. 331

- ^ Kuhlmann 2003, pp. 162–163

- ^ Eckel, Mike (April 26, 2007). «Yeltsin Laid To Rest In Elite Moscow Cemetery». KSDK NBC. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c Service 2006, pp. 198–199

- ^ «Draft Constitution of the Russian Federation» (PDF). Venice Commission. November 13, 1992(as CDL(92)52). Article 130 (3)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 11.12.93 N 2127

- ^ «Constitution of the Russian Federation». Government of the Russian Federation. December 12, 1993. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ «Russians to hail their ‘holy country’«. CNN.com. CNN. December 30, 2000. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c Franklin et al. 2004, pp. 116

- ^ a b c Sakwa 2008, pp. 224

- ^ a b c «National Anthem». Russia’s State Symbols. RIA Novosti. June 7, 2007. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Владимирова, Бориса (January 23, 2002). «Неудавшийся гимн: Имя страны – Россия!» [Unsuccessful Anthem: Our State — Russia!]. Московской правде (in Russian). Archived from the original on June 1, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Khazanov 1998, pp. 131

- ^ a b Zolotov, Andrei (December 1, 2000). «Russian Orthodox Church Approves as Putin Decides to Sing to a Soviet Tune». Christianity Today Magazine. Christianity Today International. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Waxman, Ginor & Ginor 1998, pp. 170

- ^ Korosteleva, Lawson & Marsh 2002, pp. 118

- ^ «Указ № 350 ад 2 ліпеня 2002 г. «Аб Дзяржаўным гімне Рэспублікі Беларусь»» [Decree No. 350 of July 2nd, 2002 «On the National Anthem of the Republic of Belarus»]. Указу Прэзідэнта Рэспублікі Беларусь (in Belarusian). Пресс-служба Президента Республики Беларусь. July 2, 2002. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Spain: National Symbols: National Anthem». Spain Today. Government of Spain. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Himna Bosne i Hercegovine» (in Bosnian). Ministarstvo vanjskih poslova Bosne i Hercegovine. 2001. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Duma approves old Soviet anthem». CNN.com. CNN. December 8, 2000. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Shevtsova 2005, pp. 123

- ^ «Russian Duma Approves National Anthem Bill». People’s Daily Online. People’s Daily. December 8, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ «Guide to Russia – National Anthem of the Russian Federation». Russia Today. Strana.ru. September 18, 2002. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ Shukshin, Andrei (November 30, 2000). «Putin Sings Praises of Old-New Russian Anthem». ABC News. American Broadcasting Company. p. 2. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ Голованова & Шергин 2003, pp. 152

- ^ a b Государственный гимн России (in Russian). Администрация Приморского края. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ^ «State Insignia -The National Anthem». President of the Russian Federation. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ «Russia Unveils New National Anthem Joining the Old Soviet Tune to the Older, Unsoviet God». The New York Times. December 31, 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2009.

- ^ a b «Duma approves Soviet anthem». BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. December 8, 2000. Retrieved December 19, 2009.