Всего столетие тому назад люди еще не имели такого подробного представления о составе кровяного русла и тем более, сколько групп крови существует, какое может сейчас получить любой интересующийся. Открытие всех групп крови принадлежит нобелевскому лауреату австрийскому ученому Карлу Ландштейнеру и его коллеге по исследовательской лаборатории. Группа крови как понятие стало употребляться с 1900 года. Разберемся, какие группы крови существуют и их характеристика.

Классификация по системе АВ0

Что такое группа крови? У каждого индивидуума в плазматической мембране эритроцитов есть около 300 различных антигенных элементов. Агглютиногенные частицы на молекулярном уровне по своей структуре закодированы посредством определенных форм одного и того же гена (аллеля) в одинаковых хромосомных участках (локусах).

Чем отличаются группы крови? Любая группа кровотока определяется специфическими системами антигенов эритроцитов, контролируемыми установленными локусами. И от того какие аллельные гены (обозначается буквами), в идентичных хромосомных участках находятся, и будет зависеть категория кровяной субстанции.

Точная численность локусов и аллелей к нынешнему моменту еще не имеет точных данных.

Какие бывают группы крови? Достоверно установлены около 50 разновидностей антигенов, но наиболее часто встречаются такие типы аллельных генов, как А и В. Поэтому именно они используются для обозначения групп плазмы. Особенности типа кровяной субстанции определяются объединением антигенных свойств кровотока, то есть унаследованных и переданных с кровью совокупностей генов. Каждое обозначение группы крови соответствует антигенным качествам красных кровяных телец, содержащихся в клеточной мембране.

Основная классификация групп крови по системе АВ0:

| Группы | Описание |

|---|---|

| I (0) | Отсутствие эритроцитарных антигенных свойств. |

| II (А) | Наличие в эритроцитарной оболочке антигена типа А. |

| III (В) | Присутствие в клеточной мембране эритроцитов антигена типа В. |

| IV (АВ) | Нахождение в плазматической оболочке красных кровяных телец антигенов обоих типов А и В. |

Виды групп крови различаются не только по категориям, есть еще такое понятие, как резус-фактор. Серологическая диагностика и обозначения группы крови и резус фактора всегда делаются одновременно. Потому как для переливания кровяной массы, например, жизненно важным значением является как группа кровяной субстанции, так и ее резус-фактор. И если группе крови свойственно иметь буквенное выражение, то резусные показатели всегда обозначались математическими символами такими как (+) и (−), что значит положительный или отрицательный резус-фактор.

Сочетаемость групп крови и резус-фактора

Резусной совместимости и по группам кровотока придается большое значение при переливании и планировании беременности, во избежание конфликтности эритроцитарной массы. Что касается переливания крови, особенно в экстренных ситуациях, эта процедура способна подарить пострадавшему жизнь. Только возможно это при идеальном совпадении всех компонентов крови. При малейшем несоответствии по группе либо резусу, может произойти склеивание эритроцитов, что влечет за собой, как правило, гемолитическую анемию или почечную недостаточность.

При таких обстоятельствах реципиента может постичь шоковое состояние, что нередко заканчивается летально.

Дабы исключить критические последствия гемотрансфузии, непосредственно перед вливанием крови медики проводят биологическую пробу на совместимость. Для этого реципиенту вливается небольшое количество цельной крови или отмытых эритроцитов и анализируется его самочувствие. Если отсутствуют симптомы, свидетельствующие о неприятии кровяной массы, то кровь можно вливать в полном, необходимом объеме.

Признаками отторжения кровяной жидкости (гемотрансфузионного шока) служат:

- озноб с выраженным ощущением холода;

- посинение кожи и слизистых;

- повышение температуры;

- появление судорог;

- тяжесть при дыхании, одышка;

- перевозбужденное состояние;

- снижение артериального давления;

- боли в поясничной области, в районе груди и живота, а также в мышцах.

Приведены наиболее характерные симптомы, которые возможны при вливании образца неподходящей кровяной субстанции. Внутрисосудистое введение кровяного вещества осуществляется под непрестанным контролем медицинского персонала, который при первых признаках шока должен приступить к реанимационным действиям в отношении реципиента. Гемотрансфузия требует высокого профессионализма, поэтому проводится строго в условиях стационара. Как влияют показатели кровяной жидкости на совместимость наглядно показано в таблице групп крови и резус-факторов.

Группы крови таблица:

| Группы крови обозначение и резус-фактор | Распространенность среди людей планеты | Для каких групп может быть донором | Какие категории кровотока подходят реципиенту |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (0) Rh «+» | 40–50% | 0, А, В, АВ с «+» и «−» | 0 с «+» и «−» |

| I (0) Rh «−» | 7–10% | 0, А, В, АВ с «−» | 0 с «−» |

| II (A) Rh «+» | 30–35% | А, АВ с «+» | 0, А с «+» и «−» |

| II (A) Rh «−» | 6–8% | А, АВ с «−» | 0, А с «−» |

| III (B) Rh «+» | 8–12% | В, АВ с «+» | 0, В с «+» и «−» |

| III (B) Rh «−» | 1–2% | В, АВ с «−» | 0, В с «−» |

| IV (AB) Rh «+» | 5–7% | АВ с «+» | 0, А, В, АВ с «+» |

| IV (AB) Rh «−» | менее 1% | АВ с «−» | АВ с «−» |

Схема, приведенная в таблице гипотетическая. На практике врачи отдают предпочтение классической гемотрансфузии ― это полное совпадение кровяной жидкости донора и реципиента. И лишь при крайней необходимости медицинский персонал решается на переливание допустимой крови.

Методы определения категорий крови

Диагностика на вычисление групп крови проводится после получения венозного или кровяного материала пациента. Чтобы установить резус-фактор понадобится кровь из вены, которую соединяют с двумя сыворотками (положительная и отрицательная).

О наличии у пациента того или иного резус-фактора свидетельствует образец, где нет агглютинации (склеивания эритроцитов).

Для определения группы кровяной массы используют следующие способы:

- Экспресс-диагностика применяется в экстренных случаях, ответ можно получить уже спустя три минуты. Осуществляется она с использованием пластиковых карточек с нанесенными на дно высушенными реактивами. Показывает одновременно группу и резус.

- Двойная перекрестная реакция используется для уточнения сомнительного результата исследования. Оценивают результат после смешивания сыворотки пациента с эритроцитарным материалом. Сведения доступны для интерпретации уже спустя 5 минут.

- Цоликлонирования при этом способе диагностики натуральные сыворотки подменяются искусственными цоликлонами (анти-А и -В).

- Стандартное определение категории кровотока выполняется путем соединения нескольких капель крови пациента с образцами сыворотки с четырьмя экземплярами известных антигенных фенотипов. Результат доступен в течение пяти минут.

Если агглютинация отсутствует во всех четырех образцах, то такой признак говорит, что перед вами первая группа. И в противоположность этому, когда во всех пробах происходит слипание эритроцитов, то этот факт указывает на четвертую группу. Касаемо второй и третьей категории крови, о каждой из них можно судить, в случае отсутствия агглютинации в биологическом образце сыворотки определяемой группы.

Отличительные свойства четырех групп крови

Характеристика групп крови позволяет судить не только о состоянии организма, физиологических особенностях и предпочтениях в пище. Вдобавок ко всем перечисленным сведениям, благодаря группам крови у человека, легко получить психологический портрет. Удивительно, но людьми давно подмечено, а учеными научно обосновано, что категории кровяной жидкости способны повлиять на личностные качества своих обладателей. Итак, рассмотрим описание группы крови и их характеристики.

Первая группа биологической среды человека принадлежит к самым истокам цивилизации и является самой многочисленной. Принято считать, что изначально 1 группа кровотока, свободная от агглютиногенных свойств эритроцитов, была у всех жителей Земли. Самые древние прародители выживали за счет охоты, ― это обстоятельство наложило свой отпечаток на их черты личности.

Психологический тип людей с «охотничьей» категорией крови:

- Целеустремленность.

- Лидерские качества.

- Уверенность в собственных силах.

К негативным аспектам личности относятся такие черты, как суетливость, ревность, чрезмерная амбициозность. Вполне естественно, что именно волевые качества характера и мощный инстинкт самосохранения способствовали выживанию предков и, тем самым сбережению расы доныне. Чтобы отлично себя чувствовать, представителям первого типа крови требуется преобладание белков в рационе и сбалансированное количество жиров и углеводов.

Формирование второй группы биологической жидкости начало происходить спустя примерно несколько десятков тысячелетий после первой. Состав крови стал претерпевать изменения из-за постепенного перехода многих общин на растительный вид питания, выращенный в процессе земледелия. Активное обрабатывание земли для культивирования различных злаков, плодовых и ягодных растений, привело к тому, что люди стали обосновываться в общины. Образ жизни в обществе и совместная трудовая занятость сказались как на изменении компонентов кровеносной системы, так и на личности индивидуумов.

Качества личности людей с «земледельческим» видом крови:

- Добросовестность и трудолюбие.

- Дисциплинированность, надежность, предусмотрительность.

- Доброжелательность, общительность и дипломатичность.

- Спокойный нрав и терпеливое отношение к окружающим.

- Организаторский талант.

- Быстрое приспособление к новой обстановке.

- Настойчивость в достижении намеченных целей.

В числе столь ценных качеств существовали и негативные черты характера, которые обозначим как чрезмерная осторожность и напряженность. Но это не перекрывает общего благоприятного впечатления от того, как на человечество повлияло разнообразие в питании и изменения в образе жизни. Особое внимание обладателям второй группы кровяного русла стоит уделить умению расслабляться. А насчет питания, то для них предпочтительна пища с преобладанием овощей, фруктов и злаков.

Мясо допускается белое лучше выбирать для питания легко усваиваемые белки.

Третья группа начала образовываться в результате волнообразного переселения жителей африканской местности на территории Европы, Америки, Азии. Особенности непривычного климата, другие продукты питания, развитие животноводства и прочие факторы стали причиной изменений, произошедших в кровеносной системе. Для людей этого типа крови, кроме мясных, полезны к тому же и молочные продукты животноводства. А также зерновые, бобовые, овощные, фруктовые и ягодные культуры.

Третья группа кровеносного русла говорит о своем владельце, что он:

- Выдающийся индивидуалист.

- Терпеливый и уравновешенный.

- Гибкий в партнерских отношениях.

- Сильный духом и оптимистично настроен.

- Слегка сумасбродный и непредсказуемый.

- Способный к оригинальному образу мыслей.

- Творческая личность с развитым воображением.

Среди такого количества полезных личностных качеств, неблагоприятно отличается только независимость «кочевников-скотоводов» и нежелание подчиняться сложившимся устоям. Хотя это почти не влияет на их взаимоотношения в обществе. Потому как эти люди, отличающиеся коммуникабельностью, легко найдут подход к любому человеку.

Особенности крови человека наложили свой отпечаток и на представителей земной расы с самой редкой группой кровяной субстанции ― четвертой.

Неординарная индивидуальность обладателей редчайшей четвертой категории крови:

- Творческое восприятие окружающего мира.

- Пристрастие ко всему прекрасному.

- Ярко выраженные интуитивные способности.

- Альтруисты по натуре, склонные к состраданию.

- Изысканный вкус.

В общем, носители четвертого типа крови отличаются уравновешенностью, чуткостью и врожденным чувством такта. Но иногда им свойственна резкость в высказываниях, что может создать неблагоприятное впечатление. Тонкая душевная организация и отсутствие напористости нередко вынуждают колебаться в принятии решения. Перечень разрешенных продуктов очень разнообразный, среди которого присутствуют продукты животного и растительного происхождения. Интересно отметить, что многие черты личности, которые люди приписывают обычно своим заслугам, оказываются всего лишь особенностями группы крови.

Blood type (or blood group) is determined, in part, by the ABO blood group antigens present on red blood cells.

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is a classification of blood, based on the presence and absence of antibodies and inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system. Some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of cells of various tissues. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens can stem from one allele (or an alternative version of a gene) and collectively form a blood group system.[1]

Blood types are inherited and represent contributions from both parents of an individual. As of September 2022, a total of 43 human blood group systems are recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT).[2] The two most important blood group systems are ABO and Rh; they determine someone’s blood type (A, B, AB, and O, with + or − denoting RhD status) for suitability in blood transfusion.

Blood group systems[edit]

A complete blood type would describe each of the 43 blood groups, and an individual’s blood type is one of many possible combinations of blood-group antigens.[2] Almost always, an individual has the same blood group for life, but very rarely an individual’s blood type changes through addition or suppression of an antigen in infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.[3][4][5][6] Another more common cause of blood type change is a bone marrow transplant. Bone-marrow transplants are performed for many leukemias and lymphomas, among other diseases. If a person receives bone marrow from someone of a different ABO type (e.g., a type A patient receives a type O bone marrow), the patient’s blood type should eventually become the donor’s type, as the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are destroyed, either by ablation of the bone marrow or by the donor’s T-cells. Once all the patient’s original red blood cells have died, they will have been fully replaced by new cells derived from the donor HSCs. Provided the donor had a different ABO type, the new cells’ surface antigens will be different from those on the surface of the patient’s original red blood cells.[citation needed]

Some blood types are associated with inheritance of other diseases; for example, the Kell antigen is sometimes associated with McLeod syndrome.[7] Certain blood types may affect susceptibility to infections, an example being the resistance to specific malaria species seen in individuals lacking the Duffy antigen.[8] The Duffy antigen, presumably as a result of natural selection, is less common in population groups from areas having a high incidence of malaria.[9]

ABO blood group system[edit]

ABO blood group system: diagram showing the carbohydrate chains that determine the ABO blood group

The ABO blood group system involves two antigens and two antibodies found in human blood. The two antigens are antigen A and antigen B. The two antibodies are antibody A and antibody B. The antigens are present on the red blood cells and the antibodies in the serum. Regarding the antigen property of the blood all human beings can be classified into four groups, those with antigen A (group A), those with antigen B (group B), those with both antigen A and B (group AB) and those with neither antigen (group O). The antibodies present together with the antigens are found as follows:[citation needed]

- Antigen A with antibody B

- Antigen B with antibody A

- Antigen AB with neither antibody A nor B

- Antigen null (group O) with both antibody A and B

There is an agglutination reaction between similar antigen and antibody (for example, antigen A agglutinates the antibody A and antigen B agglutinates the antibody B). Thus, transfusion can be considered safe as long as the serum of the recipient does not contain antibodies for the blood cell antigens of the donor.[citation needed]

The ABO system is the most important blood-group system in human-blood transfusion. The associated anti-A and anti-B antibodies are usually immunoglobulin M, abbreviated IgM, antibodies. It has been hypothesized that ABO IgM antibodies are produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, bacteria, and viruses, although blood group compatibility rules are applied to newborn and infants as a matter of practice.[10] The original terminology used by Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification was A/B/C; in later publications «C» became «O».[11] Type O is often called 0 (zero, or null) in other languages.[11][12]

Rh blood group system[edit]

The Rh system (Rh meaning Rhesus) is the second most significant blood-group system in human-blood transfusion with currently 50 antigens. The most significant Rh antigen is the D antigen, because it is the most likely to provoke an immune system response of the five main Rh antigens. It is common for D-negative individuals not to have any anti-D IgG or IgM antibodies, because anti-D antibodies are not usually produced by sensitization against environmental substances. However, D-negative individuals can produce IgG anti-D antibodies following a sensitizing event: possibly a fetomaternal transfusion of blood from a fetus in pregnancy or occasionally a blood transfusion with D positive RBCs.[13] Rh disease can develop in these cases.[14] Rh negative blood types are much less common in Asian populations (0.3%) than they are in European populations (15%).[15]

The presence or absence of the Rh(D) antigen is signified by the + or − sign, so that, for example, the A− group is ABO type A and does not have the Rh (D) antigen.[citation needed]

ABO and Rh distribution by country[edit]

As with many other genetic traits, the distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups varies significantly between populations.[citation needed]

Other blood group systems[edit]

As of September 2022, 41 blood-group systems have been identified by the International Society for Blood Transfusion in addition to the ABO and Rh systems.[2] Thus, in addition to the ABO antigens and Rh antigens, many other antigens are expressed on the RBC surface membrane. For example, an individual can be AB, D positive, and at the same time M and N positive (MNS system), K positive (Kell system), Lea or Leb negative (Lewis system), and so on, being positive or negative for each blood group system antigen. Many of the blood group systems were named after the patients in whom the corresponding antibodies were initially encountered. Blood group systems other than ABO and Rh pose a potential, yet relatively low, risk of complications upon mixing of blood from different people.[16]

Following is a comparison of clinically relevant characteristics of antibodies against the main human blood group systems:[17]

| ABO | Rh | Kell | Duffy | Kidd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturally occurring | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Most common in immediate hemolytic transfusion reactions | A | Yes | Fya | Jka | |

| Most common in delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions | E,D,C | Jka | |||

| Most common in hemolytic disease of the newborn | Yes | D,C | Yes | ||

| Commonly produce intravascular hemolysis | Yes | Yes |

Clinical significance[edit]

Blood transfusion[edit]

Transfusion medicine is a specialized branch of hematology that is concerned with the study of blood groups, along with the work of a blood bank to provide a transfusion service for blood and other blood products. Across the world, blood products must be prescribed by a medical doctor (licensed physician or surgeon) in a similar way as medicines.[citation needed]

Much of the routine work of a blood bank involves testing blood from both donors and recipients to ensure that every individual recipient is given blood that is compatible and is as safe as possible. If a unit of incompatible blood is transfused between a donor and recipient, a severe acute hemolytic reaction with hemolysis (RBC destruction), kidney failure and shock is likely to occur, and death is a possibility. Antibodies can be highly active and can attack RBCs and bind components of the complement system to cause massive hemolysis of the transfused blood.[citation needed]

Patients should ideally receive their own blood or type-specific blood products to minimize the chance of a transfusion reaction. It is also possible to use the patient’s own blood for transfusion. This is called autologous blood transfusion, which is always compatible with the patient. The procedure of washing a patient’s own red blood cells goes as follows: The patient’s lost blood is collected and washed with a saline solution. The washing procedure yields concentrated washed red blood cells. The last step is reinfusing the packed red blood cells into the patient. There are multiple ways to wash red blood cells. The two main ways are centrifugation and filtration methods. This procedure can be performed with microfiltration devices like the Hemoclear filter. Risks can be further reduced by cross-matching blood, but this may be skipped when blood is required for an emergency. Cross-matching involves mixing a sample of the recipient’s serum with a sample of the donor’s red blood cells and checking if the mixture agglutinates, or forms clumps. If agglutination is not obvious by direct vision, blood bank technologist usually check for agglutination with a microscope. If agglutination occurs, that particular donor’s blood cannot be transfused to that particular recipient. In a blood bank it is vital that all blood specimens are correctly identified, so labelling has been standardized using a barcode system known as ISBT 128.

The blood group may be included on identification tags or on tattoos worn by military personnel, in case they should need an emergency blood transfusion. Frontline German Waffen-SS had blood group tattoos during World War II.

Rare blood types can cause supply problems for blood banks and hospitals. For example, Duffy-negative blood occurs much more frequently in people of African origin,[20] and the rarity of this blood type in the rest of the population can result in a shortage of Duffy-negative blood for these patients. Similarly, for RhD negative people there is a risk associated with travelling to parts of the world where supplies of RhD negative blood are rare, particularly East Asia, where blood services may endeavor to encourage Westerners to donate blood.[21]

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)[edit]

A pregnant woman may carry a fetus with a blood type which is different from her own. Typically, this is an issue if a Rh- mother has a child with a Rh+ father, and the fetus ends up being Rh+ like the father.[22] In those cases, the mother can make IgG blood group antibodies. This can happen if some of the fetus’ blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation (e.g. a small fetomaternal hemorrhage at the time of childbirth or obstetric intervention), or sometimes after a therapeutic blood transfusion. This can cause Rh disease or other forms of hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. Sometimes this is lethal for the fetus; in these cases it is called hydrops fetalis.[23] If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-D antibodies, the Rh blood type of a fetus can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease.[24] One of the major advances of twentieth century medicine was to prevent this disease by stopping the formation of Anti-D antibodies by D negative mothers with an injectable medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.[25][26] Antibodies associated with some blood groups can cause severe HDN, others can only cause mild HDN and others are not known to cause HDN.[23]

Blood products[edit]

To provide maximum benefit from each blood donation and to extend shelf-life, blood banks fractionate some whole blood into several products. The most common of these products are packed RBCs, plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP). FFP is quick-frozen to retain the labile clotting factors V and VIII, which are usually administered to patients who have a potentially fatal clotting problem caused by a condition such as advanced liver disease, overdose of anticoagulant, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).[citation needed]

Units of packed red cells are made by removing as much of the plasma as possible from whole blood units.

Clotting factors synthesized by modern recombinant methods are now in routine clinical use for hemophilia, as the risks of infection transmission that occur with pooled blood products are avoided.

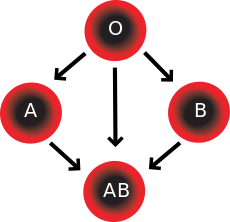

Red blood cell compatibility[edit]

- Blood group AB individuals have both A and B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood plasma does not contain any antibodies against either A or B antigen. Therefore, an individual with type AB blood can receive blood from any group (with AB being preferable), but cannot donate blood to any group other than AB. They are known as universal recipients.

- Blood group A individuals have the A antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the B antigen. Therefore, a group A individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups A or O (with A being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type A or AB.

- Blood group B individuals have the B antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the A antigen. Therefore, a group B individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups B or O (with B being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type B or AB.

- Blood group O (or blood group zero in some countries) individuals do not have either A or B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood serum contains IgM anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Therefore, a group O individual can receive blood only from a group O individual, but can donate blood to individuals of any ABO blood group (i.e., A, B, O or AB). If a patient needs an urgent blood transfusion, and if the time taken to process the recipient’s blood would cause a detrimental delay, O negative blood can be issued. Because it is compatible with anyone, O negative blood is often overused and consequently is always in short supply.[27] According to the American Association of Blood Banks and the British Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee, the use of group O RhD negative red cells should be restricted to persons with O negative blood, women who might be pregnant, and emergency cases in which blood-group testing is genuinely impracticable.[27]

Red blood cell compatibility chart

In addition to donating to the same blood group; type O blood donors can give to A, B and AB; blood donors of types A and B can give to AB.

| Recipient[1] | Donor[1] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O− | O+ | A− | A+ | B− | B+ | AB− | AB+ | |

| O− | ||||||||

| O+ | ||||||||

| A− | ||||||||

| A+ | ||||||||

| B− | ||||||||

| B+ | ||||||||

| AB− | ||||||||

| AB+ |

Table note

1. Assumes absence of atypical antibodies that would cause an incompatibility between donor and recipient blood, as is usual for blood selected by cross matching.

An Rh D-negative patient who does not have any anti-D antibodies (never being previously sensitized to D-positive RBCs) can receive a transfusion of D-positive blood once, but this would cause sensitization to the D antigen, and a female patient would become at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn. If a D-negative patient has developed anti-D antibodies, a subsequent exposure to D-positive blood would lead to a potentially dangerous transfusion reaction. Rh D-positive blood should never be given to D-negative women of child-bearing age or to patients with D antibodies, so blood banks must conserve Rh-negative blood for these patients. In extreme circumstances, such as for a major bleed when stocks of D-negative blood units are very low at the blood bank, D-positive blood might be given to D-negative females above child-bearing age or to Rh-negative males, providing that they did not have anti-D antibodies, to conserve D-negative blood stock in the blood bank. The converse is not true; Rh D-positive patients do not react to D negative blood.

This same matching is done for other antigens of the Rh system as C, c, E and e and for other blood group systems with a known risk for immunization such as the Kell system in particular for females of child-bearing age or patients with known need for many transfusions.

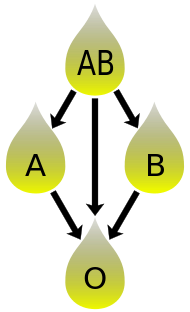

Plasma compatibility[edit]

Plasma compatibility chart

In addition to donating to the same blood group; plasma from type AB can be given to A, B and O; plasma from types A, B and AB can be given to O.

Blood plasma compatibility is the inverse of red blood cell compatibility.[30] Type AB plasma carries neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies and can be transfused to individuals of any blood group; but type AB patients can only receive type AB plasma. Type O carries both antibodies, so individuals of blood group O can receive plasma from any blood group, but type O plasma can be used only by type O recipients.

| Recipient | Donor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | A | B | AB | |

| O | ||||

| A | ||||

| B | ||||

| AB |

Table note

1. Assuming absence of strong atypical antibodies in donor plasma

Rh D antibodies are uncommon, so generally neither D negative nor D positive blood contain anti-D antibodies. If a potential donor is found to have anti-D antibodies or any strong atypical blood group antibody by antibody screening in the blood bank, they would not be accepted as a donor (or in some blood banks the blood would be drawn but the product would need to be appropriately labeled); therefore, donor blood plasma issued by a blood bank can be selected to be free of D antibodies and free of other atypical antibodies, and such donor plasma issued from a blood bank would be suitable for a recipient who may be D positive or D negative, as long as blood plasma and the recipient are ABO compatible.[citation needed]

Universal donors and universal recipients[edit]

A hospital worker takes samples of blood from a donor for testing

In transfusions of packed red blood cells, individuals with type O Rh D negative blood are often called universal donors. Those with type AB Rh D positive blood are called universal recipients. However, these terms are only generally true with respect to possible reactions of the recipient’s anti-A and anti-B antibodies to transfused red blood cells, and also possible sensitization to Rh D antigens. One exception is individuals with hh antigen system (also known as the Bombay phenotype) who can only receive blood safely from other hh donors, because they form antibodies against the H antigen present on all red blood cells.[32][33]

Blood donors with exceptionally strong anti-A, anti-B or any atypical blood group antibody may be excluded from blood donation. In general, while the plasma fraction of a blood transfusion may carry donor antibodies not found in the recipient, a significant reaction is unlikely because of dilution.

Additionally, red blood cell surface antigens other than A, B and Rh D, might cause adverse reactions and sensitization, if they can bind to the corresponding antibodies to generate an immune response. Transfusions are further complicated because platelets and white blood cells (WBCs) have their own systems of surface antigens, and sensitization to platelet or WBC antigens can occur as a result of transfusion.

For transfusions of plasma, this situation is reversed. Type O plasma, containing both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, can only be given to O recipients. The antibodies will attack the antigens on any other blood type. Conversely, AB plasma can be given to patients of any ABO blood group, because it does not contain any anti-A or anti-B antibodies.

Blood typing[edit]

Typically, blood type tests are performed through addition of a blood sample to a solution containing antibodies corresponding to each antigen. The presence of an antigen on the surface of the blood cells is indicated by agglutination.

Blood group genotyping[edit]

In addition to the current practice of serologic testing of blood types, the progress in molecular diagnostics allows the increasing use of blood group genotyping. In contrast to serologic tests reporting a direct blood type phenotype, genotyping allows the prediction of a phenotype based on the knowledge of the molecular basis of the currently known antigens. This allows a more detailed determination of the blood type and therefore a better match for transfusion, which can be crucial in particular for patients with needs for many transfusions to prevent allo-immunization.[34][35]

History[edit]

Blood types were first discovered by an Austrian physician, Karl Landsteiner, working at the Pathological-Anatomical Institute of the University of Vienna (now Medical University of Vienna). In 1900, he found that blood sera from different persons would clump together (agglutinate) when mixed in test tubes, and not only that, some human blood also agglutinated with animal blood.[36] He wrote a two-sentence footnote:

The serum of healthy human beings not only agglutinates animal red cells, but also often those of human origin, from other individuals. It remains to be seen whether this appearance is related to inborn differences between individuals or it is the result of some damage of bacterial kind.[37]

This was the first evidence that blood variation exists in humans. The next year, in 1901, he made a definitive observation that blood serum of an individual would agglutinate with only those of certain individuals. Based on this he classified human bloods into three groups, namely group A, group B, and group C. He defined that group A blood agglutinates with group B, but never with its own type. Similarly, group B blood agglutinates with group A. Group C blood is different in that it agglutinates with both A and B.[38] This was the discovery of blood groups for which Landsteiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930. (C was later renamed to O after the German Ohne, meaning without, or zero, or null.[39]) Another group (later named AB) was discovered a year later by Landsteiner’s students Adriano Sturli and Alfred von Decastello without designating the name (simply referring it to as «no particular type»).[40][41] Thus, after Landsteiner, three blood types were initially recognised, namely A, B, and C.[41]

Czech serologist Jan Janský was the first to recognise and designate four blood types in 1907 that he published in a local journal,[42] using the Roman numerical I, II, III, and IV (corresponding to modern O, A, B, and AB respectively).[43] Unknown to Janský, an American physician William L. Moss introduced almost identical classification in 1910;[44] but his I and IV corresponding Janský’s IV and I.[45] Moss came across Janský’s paper as his was being printed, mentioned it in a footnote.[41] Thus the existence of two systems immediately created confusion and potential danger in medical practice. Moss’s system was adopted in Britain, France, and the US, while Janský’s was preferred in most other European countries and some parts of the US. It was reported that «The practically universal use of the Moss classification at that time was completely and purposely cast aside. Therefore in place of bringing order out of chaos, chaos was increased in the larger cities.»[46] To resolve the confusion, the American Association of Immunologists, the Society of American Bacteriologists, and the Association of Pathologists and Bacteriologists made a joint recommendation in 1921 that the Jansky classification be adopted based on priority.[47] But it was not followed particularly where Moss’s system had been used.[48]

In 1927, Landsteiner, who had moved to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York, and as a member of a committee of the National Research Council concerned with blood grouping suggested to substitute Janský’s and Moss’s systems with the letters O, A, B, and AB. There was another confusion on the use of O which was introduced by Polish physicians Ludwik Hirszfeld and German physician Emil von Dungern in 1910.[49] It was never clear whether it was meant for the figure 0, German null for zero or the upper case letter O for ohne, meaning without; Landsteiner chose the latter.[50]

In 1928 the Permanent Commission on Biological Standardization adopted Landsteiner’s proposal and stated:

The Commission learns with satisfaction that, on the initiative of the Health Organization of the League of Nations, the nomenclature proposed by von Dungern and Hirszfeld for the classification of blood groups has been generally accepted, and recommends that this nomenclature shall be adopted for international use as follows: 0 A B AB. To facilitate the change from the nomenclature hitherto employed the following is suggested:

- Jansky ….0(I) A(II) B(III) AB(IV)

- Moss … O(IV) A(II) B(III) AB(I)[51]

This classification became widely accepted and after the early 1950s it was universally followed.[52]

Hirszfeld and Dungern discovered the inheritance of blood types as Mendelian genetics in 1910 and the existence of sub-types of A in 1911.[49][53] In 1927, Landsteiner, with Philip Levine, discovered the MN blood group system,[54] and the P system.[55] Development of the Coombs test in 1945,[56] the advent of transfusion medicine, and the understanding of ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn led to discovery of more blood groups. As of September 2022, the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) recognizes 43 blood groups.[2]

Society and culture[edit]

A popular pseudoscientific belief in Eastern Asian countries (especially in Japan and South Korea[57]) known as 血液型 ketsuekigata / hyeoraekhyeong is that a person’s ABO blood type is predictive of their personality, character, and compatibility with others.[58] Researchers have established no scientific basis exists for blood type personality categorization, and studies have found no «significant relationship between personality and blood type, rendering the theory «obsolete» and concluding that no basis exists to assume that personality is anything more than randomly associated with blood type.»[57]

See also[edit]

- Blood type (non-human)

- Human leukocyte antigen

- hh blood group

References[edit]

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ a b c d «Red Cell Immunogenetics and Blood Group Terminology». International Society of Blood Transfusion. 2022. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Dean 2005, The ABO blood group «… A number of illnesses may alter a person’s ABO phenotype …»

- ^ Stayboldt C, Rearden A, Lane TA (1987). «B antigen acquired by normal A1 red cells exposed to a patient’s serum». Transfusion. 27 (1): 41–4. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1987.27187121471.x. PMID 3810822. S2CID 38436810.

- ^ Matsushita S, Imamura T, Mizuta T, Hanada M (November 1983). «Acquired B antigen and polyagglutination in a patient with gastric cancer». The Japanese Journal of Surgery. 13 (6): 540–2. doi:10.1007/BF02469500. PMID 6672386. S2CID 6018274.

- ^ Kremer Hovinga I, Koopmans M, de Heer E, Bruijn J, Bajema I (2007). «Change in blood group in systemic lupus erythematosus». Lancet. 369 (9557): 186–7, author reply 187. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60099-3. PMID 17240276. S2CID 1150239.

- ^ Chown B.; Lewis M.; Kaita K. (October 1957). «A new Kell blood-group phenotype». Nature. 180 (4588): 711. Bibcode:1957Natur.180..711C. doi:10.1038/180711a0. PMID 13477267.

- ^ Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH (August 1976). «The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy». The New England Journal of Medicine. 295 (6): 302–4. doi:10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. PMID 778616.

- ^ Kwiatkowski DP (August 2005). «How Malaria Has Affected the Human Genome and What Human Genetics Can Teach Us about Malaria». American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (2): 171–92. doi:10.1086/432519. PMC 1224522. PMID 16001361.

The different geographic distributions of α thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, ovalocytosis, and the Duffy-negative blood group are further examples of the general principle that different populations have evolved different genetic variants to protect against malaria

- ^ «Position statement: Red blood cell transfusion in newborn infants». Canadian Pediatric Society. April 14, 2014. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018.

- ^ a b Schmidt, P; Okroi, M (2001), «Also sprach Landsteiner – Blood Group ‘O’ or Blood Group ‘NULL’«, Infus Ther Transfus Med, 28 (4): 206–8, doi:10.1159/000050239, S2CID 57677644

- ^ «Your blood – a textbook about blood and blood donation» (PDF). p. 63. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Talaro, Kathleen P. (2005). Foundations in microbiology (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 510–1. ISBN 0-07-111203-0.

- ^ Moise KJ (July 2008). «Management of rhesus alloimmunization in pregnancy». Obstetrics and Gynecology. 112 (1): 164–76. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817d453c. PMID 18591322. S2CID 1997656.

- ^ «Rh血型的由來». Hospital.kingnet.com.tw. Archived from the original on 2009-12-11. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Goodell, Pamela P.; Uhl, Lynne; Mohammed, Monique; Powers, Amy A. (2010). «Risk of Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions Following Emergency-Release RBC Transfusion». American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 134 (2): 202–206. doi:10.1309/AJCP9OFJN7FLTXDB. ISSN 0002-9173. PMID 20660321.

- ^ Mais, Daniel (2014). Quick compendium of clinical pathology. United States: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-615-9. OCLC 895712380.

- ^ Possible Risks of Blood Product Transfusions Archived 2009-11-05 at the Wayback Machine from American Cancer Society. Last Medical Review: 03/08/2008. Last Revised: 01/13/2009

- ^ 7 adverse reactions to transfusion Archived 2015-11-07 at the Wayback Machine Pathology Department at University of Michigan. Version July 2004, Revised 11/5/08

- ^ Nickel RG; Willadsen SA; Freidhoff LR; et al. (August 1999). «Determination of Duffy genotypes in three populations of African descent using PCR and sequence-specific oligonucleotides». Human Immunology. 60 (8): 738–42. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00039-7. PMID 10439320.

- ^ Bruce, MG (May 2002). «BCF – Members – Chairman’s Annual Report». The Blood Care Foundation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

As Rhesus Negative blood is rare amongst local nationals, this Agreement will be of particular value to Rhesus Negative expatriates and travellers

- ^ Freeborn, Donna. «Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn (HDN)». University of Rochester Medical Center. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ a b E.A. Letsky; I. Leck; J.M. Bowman (2000). «Chapter 12: Rhesus and other haemolytic diseases». Antenatal & neonatal screening (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-262826-8.

- ^ Daniels G, Finning K, Martin P, Summers J (September 2006). «Fetal blood group genotyping: present and future». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1075 (1): 88–95. Bibcode:2006NYASA1075…88D. doi:10.1196/annals.1368.011. PMID 17108196. S2CID 23230655.

- ^ «Use of Anti-D Immunoglobulin for Rh Prophylaxis». Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. May 2002. Archived from the original on December 30, 2008.

- ^ «Pregnancy – routine anti-D prophylaxis for D-negative women». NICE. May 2002. Archived from the original on 2022-02-05. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ a b American Association of Blood Banks (24 April 2014), «Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question», Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Association of Blood Banks, archived from the original on 24 September 2014, retrieved 25 July 2014, which cites

- The Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee (c. 2008). «The appropriate use of group O RhD negative red cells» (PDF). National Health Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ «RBC compatibility table». American National Red Cross. December 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Blood types and compatibility Archived 2010-04-19 at the Wayback Machine bloodbook.com

- ^ «Blood Component ABO Compatibility Chart Red Blood Cells and Plasma». Blood Bank Labsite. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ «Plasma Compatibility». Matching Blood Groups. Australian Red Cross. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S.; Eugene Braunwald; Kurt J. Isselbacher; Jean D. Wilson; Joseph B. Martin; Dennis L. Kasper; Stephen L. Hauser; Dan L. Longo (1998). Harrison’s Principals of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill. p. 719. ISBN 0-07-020291-5.

- ^ «Universal acceptor and donor groups». Webmd.com. 2008-06-12. Archived from the original on 2010-07-22. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ^ Anstee DJ (2009). «Red cell genotyping and the future of pretransfusion testing». Blood. 114 (2): 248–56. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-11-146860. PMID 19411635. S2CID 6896382.

- ^ Avent ND (2009). «Large-scale blood group genotyping: clinical implications». Br J Haematol. 144 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07285.x. PMID 19016734.

- ^ Landsteiner K (1900). «Zur Kenntnis der antifermentativen, lytischen und agglutinierenden Wirkungen des Blutserums und der Lymphe». Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde und Infektionskrankheiten. 27: 357–362.

- ^ Kantha, S.S. (1995). «The blood revolution initiated by the famous footnote of Karl Landsteiner’s 1900 paper» (PDF). The Ceylon Medical Journal. 40 (3): 123–125. PMID 8536328. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- ^ Landsteiner, Karl (1961) [1901]. «On Agglutination of Normal Human Blood». Transfusion. 1 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.1961.tb00005.x. PMID 13758692. S2CID 40158397Originally published in German in Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 46, 1132–1134

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Farhud, D.D.; Zarif Yeganeh, M. (2013). «A brief history of human blood groups». Iranian Journal of Public Health. 42 (1): 1–6. PMC 3595629. PMID 23514954.

- ^ Von Decastello, A.; Sturli, A. (1902). «Concerning isoagglutinins in serum of healthy and sick humans». Munchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 26: 1090–1095.

- ^ a b c Farr AD (April 1979). «Blood group serology—the first four decades (1900–1939)». Medical History. 23 (2): 215–26. doi:10.1017/s0025727300051383. PMC 1082436. PMID 381816.

- ^ Janský J. (1907). «Haematologick studie u. psychotiku». Sborn. Klinick (in Czech). 8: 85–139.

- ^ Garratty, G.; Dzik, W.; Issitt, P.D.; Lublin, D.M.; Reid, M.E.; Zelinski, T. (2000). «Terminology for blood group antigens and genes-historical origins and guidelines in the new millennium». Transfusion. 40 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40040477.x. PMID 10773062. S2CID 23291031. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ Moss W.L. (1910). «Studies on isoagglutinins and isohemolysins». Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 21: 63–70.

- ^ Farr AD (April 1979). «Blood group serology—the first four decades (1900–1939)». Medical History. 23 (2): 215–26. doi:10.1017/S0025727300051383. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1082436. PMID 381816.

- ^ Kennedy, James A. (1929-02-23). «Blood group classifications used in hospitals in the United States and Canada: Final Report». Journal of the American Medical Association. 92 (8): 610. doi:10.1001/jama.1929.02700340010005. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ Garratty, G.; Dzik, W.; Issitt, P. D.; Lublin, D. M.; Reid, M. E.; Zelinski, T. (2000). «Terminology for blood group antigens and genes-historical origins and guidelines in the new millennium». Transfusion. 40 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40040477.x. PMID 10773062. S2CID 23291031. Archived from the original on 2021-08-30. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ Doan, C.A. (1927). «The Transfusion problem». Physiological Reviews. 7 (1): 1–84. doi:10.1152/physrev.1927.7.1.1. ISSN 0031-9333.

- ^ a b Okroi, Mathias; McCarthy, Leo J. (July 2010). «The original blood group pioneers: the Hirszfelds». Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 24 (3): 244–246. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2010.03.006. ISSN 1532-9496. PMID 20656191. Archived from the original on 2021-08-30. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ Schmidt, P.; Okroi, M. (2001). «Also sprach Landsteiner – Blood Group ‘O’ or Blood Group ‘NULL’«. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 28 (4): 206–208. doi:10.1159/000050239. ISSN 1660-3796. S2CID 57677644.

- ^ Goodman, Neville M. (1940). «Nomenclature of Blood Groups». British Medical Journal. 1 (4123): 73. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4123.73-a. PMC 2176232.

- ^ Garratty, G.; Dzik, W.; Issitt, P.D.; Lublin, D.M.; Reid, M.E.; Zelinski, T. (2000). «Terminology for blood group antigens and genes-historical origins and guidelines in the new millennium». Transfusion. 40 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40040477.x. ISSN 0041-1132. PMID 10773062. S2CID 23291031.

- ^ Dungern, E.; Hirschfeld, L. (1911). «Über Vererbung gruppenspezifischer Strukturen des Blutes». Zeitschrift für Induktive Abstammungs- und Vererbungslehre (in German). 5 (1): 196–197. doi:10.1007/BF01798027. S2CID 3184525. Archived from the original on 2022-02-15. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ Landsteiner, K.; Levine, P. (1927). «A New Agglutinable Factor Differentiating Individual Human Bloods». Experimental Biology and Medicine. 24 (6): 600–602. doi:10.3181/00379727-24-3483. S2CID 87597493.

- ^ Landsteiner, K.; Levine, P. (1927). «Further Observations on Individual Differences of Human Blood». Experimental Biology and Medicine. 24 (9): 941–942. doi:10.3181/00379727-24-3649. S2CID 88119106.

- ^ Coombs RR, Mourant AE, Race RR (1945). «A new test for the detection of weak and incomplete Rh agglutinins». Br J Exp Pathol. 26: 255–66. PMC 2065689. PMID 21006651.

- ^ a b «Despite scientific debunking, in Japan you are what your blood type is». MediResource Inc. Associated Press. 2009-02-01. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel. «You are what you bleed: In Japan and other east Asian countries some believe blood type dictates personality». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 16 Feb 2011.

Further reading[edit]

- Dean, Laura (2005). Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens, a guide to the differences in our blood types that complicate blood transfusions and pregnancy. Bethesda MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. ISBN 1-932811-05-2. NBK2261.

- Mollison PL, Engelfriet CP, Contreras M (1997). Blood Transfusion in Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Oxford UK: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-86542-881-6.

External links[edit]

- BGMUT Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database at NCBI, NIH has details of genes and proteins, and variations thereof, that are responsible for blood types

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): ABO Glycosyltransferase; ABO — 110300

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): Rhesus Blood Group, D Antigen; RHD — 111680

- «Blood group test». Gentest.ch GmbH. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- «Blood Facts – Rare Traits». LifeShare Blood Centers. Archived from the original on September 26, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- «Modern Human Variation: Distribution of Blood Types». Dr. Dennis O’Neil, Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College, San Marcos, California. 2001-06-06. Archived from the original on 2001-06-06. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- «Racial and Ethnic Distribution of ABO Blood Types – BloodBook.com, Blood Information for Life». bloodbook.com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved September 15, 2006.

- «Molecular Genetic Basis of ABO». Retrieved July 31, 2008.

Blood type (or blood group) is determined, in part, by the ABO blood group antigens present on red blood cells.

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is a classification of blood, based on the presence and absence of antibodies and inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins, or glycolipids, depending on the blood group system. Some of these antigens are also present on the surface of other types of cells of various tissues. Several of these red blood cell surface antigens can stem from one allele (or an alternative version of a gene) and collectively form a blood group system.[1]

Blood types are inherited and represent contributions from both parents of an individual. As of September 2022, a total of 43 human blood group systems are recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT).[2] The two most important blood group systems are ABO and Rh; they determine someone’s blood type (A, B, AB, and O, with + or − denoting RhD status) for suitability in blood transfusion.

Blood group systems[edit]

A complete blood type would describe each of the 43 blood groups, and an individual’s blood type is one of many possible combinations of blood-group antigens.[2] Almost always, an individual has the same blood group for life, but very rarely an individual’s blood type changes through addition or suppression of an antigen in infection, malignancy, or autoimmune disease.[3][4][5][6] Another more common cause of blood type change is a bone marrow transplant. Bone-marrow transplants are performed for many leukemias and lymphomas, among other diseases. If a person receives bone marrow from someone of a different ABO type (e.g., a type A patient receives a type O bone marrow), the patient’s blood type should eventually become the donor’s type, as the patient’s hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are destroyed, either by ablation of the bone marrow or by the donor’s T-cells. Once all the patient’s original red blood cells have died, they will have been fully replaced by new cells derived from the donor HSCs. Provided the donor had a different ABO type, the new cells’ surface antigens will be different from those on the surface of the patient’s original red blood cells.[citation needed]

Some blood types are associated with inheritance of other diseases; for example, the Kell antigen is sometimes associated with McLeod syndrome.[7] Certain blood types may affect susceptibility to infections, an example being the resistance to specific malaria species seen in individuals lacking the Duffy antigen.[8] The Duffy antigen, presumably as a result of natural selection, is less common in population groups from areas having a high incidence of malaria.[9]

ABO blood group system[edit]

ABO blood group system: diagram showing the carbohydrate chains that determine the ABO blood group

The ABO blood group system involves two antigens and two antibodies found in human blood. The two antigens are antigen A and antigen B. The two antibodies are antibody A and antibody B. The antigens are present on the red blood cells and the antibodies in the serum. Regarding the antigen property of the blood all human beings can be classified into four groups, those with antigen A (group A), those with antigen B (group B), those with both antigen A and B (group AB) and those with neither antigen (group O). The antibodies present together with the antigens are found as follows:[citation needed]

- Antigen A with antibody B

- Antigen B with antibody A

- Antigen AB with neither antibody A nor B

- Antigen null (group O) with both antibody A and B

There is an agglutination reaction between similar antigen and antibody (for example, antigen A agglutinates the antibody A and antigen B agglutinates the antibody B). Thus, transfusion can be considered safe as long as the serum of the recipient does not contain antibodies for the blood cell antigens of the donor.[citation needed]

The ABO system is the most important blood-group system in human-blood transfusion. The associated anti-A and anti-B antibodies are usually immunoglobulin M, abbreviated IgM, antibodies. It has been hypothesized that ABO IgM antibodies are produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, bacteria, and viruses, although blood group compatibility rules are applied to newborn and infants as a matter of practice.[10] The original terminology used by Karl Landsteiner in 1901 for the classification was A/B/C; in later publications «C» became «O».[11] Type O is often called 0 (zero, or null) in other languages.[11][12]

Rh blood group system[edit]

The Rh system (Rh meaning Rhesus) is the second most significant blood-group system in human-blood transfusion with currently 50 antigens. The most significant Rh antigen is the D antigen, because it is the most likely to provoke an immune system response of the five main Rh antigens. It is common for D-negative individuals not to have any anti-D IgG or IgM antibodies, because anti-D antibodies are not usually produced by sensitization against environmental substances. However, D-negative individuals can produce IgG anti-D antibodies following a sensitizing event: possibly a fetomaternal transfusion of blood from a fetus in pregnancy or occasionally a blood transfusion with D positive RBCs.[13] Rh disease can develop in these cases.[14] Rh negative blood types are much less common in Asian populations (0.3%) than they are in European populations (15%).[15]

The presence or absence of the Rh(D) antigen is signified by the + or − sign, so that, for example, the A− group is ABO type A and does not have the Rh (D) antigen.[citation needed]

ABO and Rh distribution by country[edit]

As with many other genetic traits, the distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups varies significantly between populations.[citation needed]

Other blood group systems[edit]

As of September 2022, 41 blood-group systems have been identified by the International Society for Blood Transfusion in addition to the ABO and Rh systems.[2] Thus, in addition to the ABO antigens and Rh antigens, many other antigens are expressed on the RBC surface membrane. For example, an individual can be AB, D positive, and at the same time M and N positive (MNS system), K positive (Kell system), Lea or Leb negative (Lewis system), and so on, being positive or negative for each blood group system antigen. Many of the blood group systems were named after the patients in whom the corresponding antibodies were initially encountered. Blood group systems other than ABO and Rh pose a potential, yet relatively low, risk of complications upon mixing of blood from different people.[16]

Following is a comparison of clinically relevant characteristics of antibodies against the main human blood group systems:[17]

| ABO | Rh | Kell | Duffy | Kidd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturally occurring | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Most common in immediate hemolytic transfusion reactions | A | Yes | Fya | Jka | |

| Most common in delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions | E,D,C | Jka | |||

| Most common in hemolytic disease of the newborn | Yes | D,C | Yes | ||

| Commonly produce intravascular hemolysis | Yes | Yes |

Clinical significance[edit]

Blood transfusion[edit]

Transfusion medicine is a specialized branch of hematology that is concerned with the study of blood groups, along with the work of a blood bank to provide a transfusion service for blood and other blood products. Across the world, blood products must be prescribed by a medical doctor (licensed physician or surgeon) in a similar way as medicines.[citation needed]

Much of the routine work of a blood bank involves testing blood from both donors and recipients to ensure that every individual recipient is given blood that is compatible and is as safe as possible. If a unit of incompatible blood is transfused between a donor and recipient, a severe acute hemolytic reaction with hemolysis (RBC destruction), kidney failure and shock is likely to occur, and death is a possibility. Antibodies can be highly active and can attack RBCs and bind components of the complement system to cause massive hemolysis of the transfused blood.[citation needed]

Patients should ideally receive their own blood or type-specific blood products to minimize the chance of a transfusion reaction. It is also possible to use the patient’s own blood for transfusion. This is called autologous blood transfusion, which is always compatible with the patient. The procedure of washing a patient’s own red blood cells goes as follows: The patient’s lost blood is collected and washed with a saline solution. The washing procedure yields concentrated washed red blood cells. The last step is reinfusing the packed red blood cells into the patient. There are multiple ways to wash red blood cells. The two main ways are centrifugation and filtration methods. This procedure can be performed with microfiltration devices like the Hemoclear filter. Risks can be further reduced by cross-matching blood, but this may be skipped when blood is required for an emergency. Cross-matching involves mixing a sample of the recipient’s serum with a sample of the donor’s red blood cells and checking if the mixture agglutinates, or forms clumps. If agglutination is not obvious by direct vision, blood bank technologist usually check for agglutination with a microscope. If agglutination occurs, that particular donor’s blood cannot be transfused to that particular recipient. In a blood bank it is vital that all blood specimens are correctly identified, so labelling has been standardized using a barcode system known as ISBT 128.

The blood group may be included on identification tags or on tattoos worn by military personnel, in case they should need an emergency blood transfusion. Frontline German Waffen-SS had blood group tattoos during World War II.

Rare blood types can cause supply problems for blood banks and hospitals. For example, Duffy-negative blood occurs much more frequently in people of African origin,[20] and the rarity of this blood type in the rest of the population can result in a shortage of Duffy-negative blood for these patients. Similarly, for RhD negative people there is a risk associated with travelling to parts of the world where supplies of RhD negative blood are rare, particularly East Asia, where blood services may endeavor to encourage Westerners to donate blood.[21]

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN)[edit]

A pregnant woman may carry a fetus with a blood type which is different from her own. Typically, this is an issue if a Rh- mother has a child with a Rh+ father, and the fetus ends up being Rh+ like the father.[22] In those cases, the mother can make IgG blood group antibodies. This can happen if some of the fetus’ blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation (e.g. a small fetomaternal hemorrhage at the time of childbirth or obstetric intervention), or sometimes after a therapeutic blood transfusion. This can cause Rh disease or other forms of hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) in the current pregnancy and/or subsequent pregnancies. Sometimes this is lethal for the fetus; in these cases it is called hydrops fetalis.[23] If a pregnant woman is known to have anti-D antibodies, the Rh blood type of a fetus can be tested by analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma to assess the risk to the fetus of Rh disease.[24] One of the major advances of twentieth century medicine was to prevent this disease by stopping the formation of Anti-D antibodies by D negative mothers with an injectable medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.[25][26] Antibodies associated with some blood groups can cause severe HDN, others can only cause mild HDN and others are not known to cause HDN.[23]

Blood products[edit]

To provide maximum benefit from each blood donation and to extend shelf-life, blood banks fractionate some whole blood into several products. The most common of these products are packed RBCs, plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma (FFP). FFP is quick-frozen to retain the labile clotting factors V and VIII, which are usually administered to patients who have a potentially fatal clotting problem caused by a condition such as advanced liver disease, overdose of anticoagulant, or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).[citation needed]

Units of packed red cells are made by removing as much of the plasma as possible from whole blood units.

Clotting factors synthesized by modern recombinant methods are now in routine clinical use for hemophilia, as the risks of infection transmission that occur with pooled blood products are avoided.

Red blood cell compatibility[edit]

- Blood group AB individuals have both A and B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood plasma does not contain any antibodies against either A or B antigen. Therefore, an individual with type AB blood can receive blood from any group (with AB being preferable), but cannot donate blood to any group other than AB. They are known as universal recipients.

- Blood group A individuals have the A antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the B antigen. Therefore, a group A individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups A or O (with A being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type A or AB.

- Blood group B individuals have the B antigen on the surface of their RBCs, and blood serum containing IgM antibodies against the A antigen. Therefore, a group B individual can receive blood only from individuals of groups B or O (with B being preferable), and can donate blood to individuals with type B or AB.

- Blood group O (or blood group zero in some countries) individuals do not have either A or B antigens on the surface of their RBCs, and their blood serum contains IgM anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Therefore, a group O individual can receive blood only from a group O individual, but can donate blood to individuals of any ABO blood group (i.e., A, B, O or AB). If a patient needs an urgent blood transfusion, and if the time taken to process the recipient’s blood would cause a detrimental delay, O negative blood can be issued. Because it is compatible with anyone, O negative blood is often overused and consequently is always in short supply.[27] According to the American Association of Blood Banks and the British Chief Medical Officer’s National Blood Transfusion Committee, the use of group O RhD negative red cells should be restricted to persons with O negative blood, women who might be pregnant, and emergency cases in which blood-group testing is genuinely impracticable.[27]

Red blood cell compatibility chart

In addition to donating to the same blood group; type O blood donors can give to A, B and AB; blood donors of types A and B can give to AB.

| Recipient[1] | Donor[1] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O− | O+ | A− | A+ | B− | B+ | AB− | AB+ | |

| O− | ||||||||

| O+ | ||||||||

| A− | ||||||||

| A+ | ||||||||

| B− | ||||||||

| B+ | ||||||||

| AB− | ||||||||

| AB+ |

Table note

1. Assumes absence of atypical antibodies that would cause an incompatibility between donor and recipient blood, as is usual for blood selected by cross matching.

An Rh D-negative patient who does not have any anti-D antibodies (never being previously sensitized to D-positive RBCs) can receive a transfusion of D-positive blood once, but this would cause sensitization to the D antigen, and a female patient would become at risk for hemolytic disease of the newborn. If a D-negative patient has developed anti-D antibodies, a subsequent exposure to D-positive blood would lead to a potentially dangerous transfusion reaction. Rh D-positive blood should never be given to D-negative women of child-bearing age or to patients with D antibodies, so blood banks must conserve Rh-negative blood for these patients. In extreme circumstances, such as for a major bleed when stocks of D-negative blood units are very low at the blood bank, D-positive blood might be given to D-negative females above child-bearing age or to Rh-negative males, providing that they did not have anti-D antibodies, to conserve D-negative blood stock in the blood bank. The converse is not true; Rh D-positive patients do not react to D negative blood.

This same matching is done for other antigens of the Rh system as C, c, E and e and for other blood group systems with a known risk for immunization such as the Kell system in particular for females of child-bearing age or patients with known need for many transfusions.

Plasma compatibility[edit]

Plasma compatibility chart

In addition to donating to the same blood group; plasma from type AB can be given to A, B and O; plasma from types A, B and AB can be given to O.

Blood plasma compatibility is the inverse of red blood cell compatibility.[30] Type AB plasma carries neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies and can be transfused to individuals of any blood group; but type AB patients can only receive type AB plasma. Type O carries both antibodies, so individuals of blood group O can receive plasma from any blood group, but type O plasma can be used only by type O recipients.

| Recipient | Donor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | A | B | AB | |

| O | ||||

| A | ||||

| B | ||||

| AB |

Table note

1. Assuming absence of strong atypical antibodies in donor plasma

Rh D antibodies are uncommon, so generally neither D negative nor D positive blood contain anti-D antibodies. If a potential donor is found to have anti-D antibodies or any strong atypical blood group antibody by antibody screening in the blood bank, they would not be accepted as a donor (or in some blood banks the blood would be drawn but the product would need to be appropriately labeled); therefore, donor blood plasma issued by a blood bank can be selected to be free of D antibodies and free of other atypical antibodies, and such donor plasma issued from a blood bank would be suitable for a recipient who may be D positive or D negative, as long as blood plasma and the recipient are ABO compatible.[citation needed]

Universal donors and universal recipients[edit]

A hospital worker takes samples of blood from a donor for testing

In transfusions of packed red blood cells, individuals with type O Rh D negative blood are often called universal donors. Those with type AB Rh D positive blood are called universal recipients. However, these terms are only generally true with respect to possible reactions of the recipient’s anti-A and anti-B antibodies to transfused red blood cells, and also possible sensitization to Rh D antigens. One exception is individuals with hh antigen system (also known as the Bombay phenotype) who can only receive blood safely from other hh donors, because they form antibodies against the H antigen present on all red blood cells.[32][33]

Blood donors with exceptionally strong anti-A, anti-B or any atypical blood group antibody may be excluded from blood donation. In general, while the plasma fraction of a blood transfusion may carry donor antibodies not found in the recipient, a significant reaction is unlikely because of dilution.

Additionally, red blood cell surface antigens other than A, B and Rh D, might cause adverse reactions and sensitization, if they can bind to the corresponding antibodies to generate an immune response. Transfusions are further complicated because platelets and white blood cells (WBCs) have their own systems of surface antigens, and sensitization to platelet or WBC antigens can occur as a result of transfusion.

For transfusions of plasma, this situation is reversed. Type O plasma, containing both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, can only be given to O recipients. The antibodies will attack the antigens on any other blood type. Conversely, AB plasma can be given to patients of any ABO blood group, because it does not contain any anti-A or anti-B antibodies.

Blood typing[edit]

Typically, blood type tests are performed through addition of a blood sample to a solution containing antibodies corresponding to each antigen. The presence of an antigen on the surface of the blood cells is indicated by agglutination.

Blood group genotyping[edit]

In addition to the current practice of serologic testing of blood types, the progress in molecular diagnostics allows the increasing use of blood group genotyping. In contrast to serologic tests reporting a direct blood type phenotype, genotyping allows the prediction of a phenotype based on the knowledge of the molecular basis of the currently known antigens. This allows a more detailed determination of the blood type and therefore a better match for transfusion, which can be crucial in particular for patients with needs for many transfusions to prevent allo-immunization.[34][35]

History[edit]

Blood types were first discovered by an Austrian physician, Karl Landsteiner, working at the Pathological-Anatomical Institute of the University of Vienna (now Medical University of Vienna). In 1900, he found that blood sera from different persons would clump together (agglutinate) when mixed in test tubes, and not only that, some human blood also agglutinated with animal blood.[36] He wrote a two-sentence footnote:

The serum of healthy human beings not only agglutinates animal red cells, but also often those of human origin, from other individuals. It remains to be seen whether this appearance is related to inborn differences between individuals or it is the result of some damage of bacterial kind.[37]

This was the first evidence that blood variation exists in humans. The next year, in 1901, he made a definitive observation that blood serum of an individual would agglutinate with only those of certain individuals. Based on this he classified human bloods into three groups, namely group A, group B, and group C. He defined that group A blood agglutinates with group B, but never with its own type. Similarly, group B blood agglutinates with group A. Group C blood is different in that it agglutinates with both A and B.[38] This was the discovery of blood groups for which Landsteiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930. (C was later renamed to O after the German Ohne, meaning without, or zero, or null.[39]) Another group (later named AB) was discovered a year later by Landsteiner’s students Adriano Sturli and Alfred von Decastello without designating the name (simply referring it to as «no particular type»).[40][41] Thus, after Landsteiner, three blood types were initially recognised, namely A, B, and C.[41]

Czech serologist Jan Janský was the first to recognise and designate four blood types in 1907 that he published in a local journal,[42] using the Roman numerical I, II, III, and IV (corresponding to modern O, A, B, and AB respectively).[43] Unknown to Janský, an American physician William L. Moss introduced almost identical classification in 1910;[44] but his I and IV corresponding Janský’s IV and I.[45] Moss came across Janský’s paper as his was being printed, mentioned it in a footnote.[41] Thus the existence of two systems immediately created confusion and potential danger in medical practice. Moss’s system was adopted in Britain, France, and the US, while Janský’s was preferred in most other European countries and some parts of the US. It was reported that «The practically universal use of the Moss classification at that time was completely and purposely cast aside. Therefore in place of bringing order out of chaos, chaos was increased in the larger cities.»[46] To resolve the confusion, the American Association of Immunologists, the Society of American Bacteriologists, and the Association of Pathologists and Bacteriologists made a joint recommendation in 1921 that the Jansky classification be adopted based on priority.[47] But it was not followed particularly where Moss’s system had been used.[48]

In 1927, Landsteiner, who had moved to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York, and as a member of a committee of the National Research Council concerned with blood grouping suggested to substitute Janský’s and Moss’s systems with the letters O, A, B, and AB. There was another confusion on the use of O which was introduced by Polish physicians Ludwik Hirszfeld and German physician Emil von Dungern in 1910.[49] It was never clear whether it was meant for the figure 0, German null for zero or the upper case letter O for ohne, meaning without; Landsteiner chose the latter.[50]

In 1928 the Permanent Commission on Biological Standardization adopted Landsteiner’s proposal and stated:

The Commission learns with satisfaction that, on the initiative of the Health Organization of the League of Nations, the nomenclature proposed by von Dungern and Hirszfeld for the classification of blood groups has been generally accepted, and recommends that this nomenclature shall be adopted for international use as follows: 0 A B AB. To facilitate the change from the nomenclature hitherto employed the following is suggested:

- Jansky ….0(I) A(II) B(III) AB(IV)

- Moss … O(IV) A(II) B(III) AB(I)[51]

This classification became widely accepted and after the early 1950s it was universally followed.[52]