|

The Holy Prophet Muhammad |

|

|---|---|

|

مُحَمَّد |

|

«Muhammad, the Messenger of God.» |

|

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 570 CE (53 BH)[1]

Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Died | 8 June 632 (11 AH) (aged 61–62)

Taybah, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Resting place |

Green Dome at al-Masjid an-Nabawi, Medina, Arabia 24°28′03″N 39°36′41″E / 24.46750°N 39.61139°E |

| Spouse | See Muhammad’s wives |

| Children | See Muhammad’s children |

| Parent(s) | Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib (father) Amina bint Wahb (mother) |

| Known for | Founding Islam |

| Other names |

|

| Relatives | Family tree of Muhammad, Ahl al-Bayt («Family of the House») |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Muḥammad |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭālib ibn Hāshim ibn ʿAbd Manāf ibn Quṣayy ibn Kilāb |

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | ʾAbu al-Qāsim |

| Epithet (Laqab) | Ḵātam an-Nabiyyīn (Seal of the Prophets) |

Muhammad[a] (Arabic: مُحَمَّد; c. 570 – 8 June 632 CE)[b] was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam.[c] According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and other prophets.[2][3][4] He is believed to be the Seal of the Prophets within Islam. Muhammad united Arabia into a single Muslim polity, with the Quran as well as his teachings and practices forming the basis of Islamic religious belief.

Muhammad was born approximately 570 CE in Mecca.[1] He was the son of Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib and Amina bint Wahb. His father Abdullah was the son of Quraysh tribal leader Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim, and he died a few months before Muhammad’s birth. His mother Amina died when he was six, leaving Muhammad an orphan.[5] He was raised under the care of his grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, and paternal uncle, Abu Talib.[6] In later years, he would periodically seclude himself in a mountain cave named Hira for several nights of prayer. When he was 40, Muhammad reported being visited by Gabriel in the cave[1] and receiving his first revelation from God. In 613,[7] Muhammad started preaching these revelations publicly,[8] proclaiming that «God is One», that complete «submission» (islām) to God is the right way of life (dīn),[9] and that he was a prophet and messenger of God, similar to the other prophets in Islam.[10][3][11]

Muhammad’s followers were initially few in number, and experienced hostility from Meccan polytheists for 13 years. To escape ongoing persecution, he sent some of his followers to Abyssinia in 615, before he and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina (then known as Yathrib) later in 622. This event, the Hijra, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar, also known as the Hijri Calendar. In Medina, Muhammad united the tribes under the Constitution of Medina. In December 629, after eight years of intermittent fighting with Meccan tribes, Muhammad gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and marched on the city of Mecca. The conquest went largely uncontested and Muhammad seized the city with little bloodshed. In 632, a few months after returning from the Farewell Pilgrimage, he fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam.[12][13]

The revelations (each known as Ayah — literally, «Sign [of God]») that Muhammad reported receiving until his death form the verses of the Quran, regarded by Muslims as the verbatim «Word of God» on which the religion is based. Besides the Quran, Muhammad’s teachings and practices (sunnah), found in the Hadith and sira (biography) literature, are also upheld and used as sources of Islamic law (see Sharia).

Names and appellations

The name Muhammad ([14]) means «praiseworthy» in Arabic. It appears four times in the Quran.[15] The Quran also addresses Muhammad in the second person by various appellations; prophet, messenger, servant of God (‘abd), announcer (bashir),[16] witness (shahid),[17] bearer of good tidings (mubashshir), warner (nathir),[18] reminder (mudhakkir),[19] one who calls [unto God] (dā’ī),[20] light personified (noor),[21] and the light-giving lamp (siraj munir).[22]

Sources of biographical information

Quran

A folio from an early Quran, written in Kufic script (Abbasid period, 8th–9th centuries)

The Quran is the central religious text of Islam. Muslims believe it represents the words of God revealed by the archangel Gabriel to Muhammad.[23][24][25] The Quran, however, provides minimal assistance for Muhammad’s chronological biography; most Quranic verses do not provide significant historical context.[26][27]

Early biographies

Important sources regarding Muhammad’s life may be found in the historic works by writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Muslim era (AH – 8th and 9th century CE).[28] These include traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad, which provide additional information about Muhammad’s life.[29]

The earliest written sira (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) is Ibn Ishaq’s Life of God’s Messenger written c. 767 CE (150 AH). Although the original work was lost, this sira survives as extensive excerpts in works by Ibn Hisham and to a lesser extent by Al-Tabari.[30][31] However, Ibn Hisham wrote in the preface to his biography of Muhammad that he omitted matters from Ibn Ishaq’s biography that «would distress certain people».[32] Another early history source is the history of Muhammad’s campaigns by al-Waqidi (death 207 AH), and the work of Waqidi’s secretary Ibn Sa’d al-Baghdadi (death 230 AH).[28]

Many scholars accept these early biographies as authentic, though their accuracy is unascertainable.[30] Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between traditions touching legal matters and purely historical events. In the legal group, traditions could have been subject to invention while historic events, aside from exceptional cases, may have been only subject to «tendential shaping».[33]

Hadith

Other important sources include the hadith collections, accounts of verbal and physical teachings and traditions attributed to Muhammad. Hadiths were compiled several generations after his death by Muslims including Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi, Abd ar-Rahman al-Nasai, Abu Dawood, Ibn Majah, Malik ibn Anas, al-Daraqutni.[34][35]

Some Western academics cautiously view the hadith collections as accurate historical sources.[34] Scholars such as Madelung do not reject the narrations which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.[36] Muslim scholars on the other hand typically place a greater emphasis on the hadith literature instead of the biographical literature, since hadiths maintain a traditional chain of transmission (isnad); the lack of such a chain for the biographical literature makes it unverifiable in their eyes.[37]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Main tribes and settlements of Arabia in Muhammad’s lifetime

The Arabian Peninsula was, and still is, largely arid with volcanic soil, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. Towns and cities dotted the landscape, two of the most prominent being Mecca and Yathrib. Yathrib was a large flourishing agricultural settlement, while Mecca was an important financial center for many surrounding tribes.[38] Communal life was essential for survival in the desert conditions, supporting indigenous tribes against the harsh environment and lifestyle. Tribal affiliation, whether based on kinship or alliances, was an important source of social cohesion.[39] Indigenous Arabs were either nomadic or sedentary. Nomadic groups constantly traveled seeking water and pasture for their flocks, while the sedentary settled and focused on trade and agriculture. Nomadic survival also depended on raiding caravans or oases; nomads did not view this as a crime.[40]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, gods or goddesses were viewed as protectors of individual tribes, their spirits associated with sacred trees, stones, springs and wells. As well as being the site of an annual pilgrimage, the Kaaba shrine in Mecca housed 360 idols of tribal patron deities. Three goddesses were worshipped, in some places as daughters of Allah: Allāt, Manāt and al-‘Uzzá. Monotheistic communities existed in Arabia, including Christians and Jews.[d] Hanifs – native pre-Islamic Arabs who «professed a rigid monotheism»[41] – are also sometimes listed alongside Jews and Christians in pre-Islamic Arabia, although scholars dispute their historicity.[42][43] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad himself was a Hanif and one of the descendants of Ishmael, son of Abraham,[e] although no known evidence exists for a historical Abraham or Ishmael, and the links are based solely on tradition instead of historical records.[44]

The second half of the sixth century was a period of political disorder in Arabia and communication routes were no longer secure.[45] Religious divisions were an important cause of the crisis.[46] Judaism became the dominant religion in Yemen while Christianity took root in the Persian Gulf area.[46] In line with broader trends of the ancient world, the region witnessed a decline in the practice of polytheistic cults and a growing interest in a more spiritual form of religion. While many were reluctant to convert to a foreign faith, those faiths provided intellectual and spiritual reference points.[46]

During the early years of Muhammad’s life, the Quraysh tribe to which he belonged became a dominant force in western Arabia.[47] They formed the cult association of hums, which tied members of many tribes in western Arabia to the Kaaba and reinforced the prestige of the Meccan sanctuary.[48] To counter the effects of anarchy, Quraysh upheld the institution of sacred months during which all violence was forbidden, and it was possible to participate in pilgrimages and fairs without danger.[48] Thus, although the association of hums was primarily religious, it also had important economic consequences for the city.[48]

Life

Childhood and early life

| Timeline of Muhammad’s life | ||

|---|---|---|

| Important dates and locations in the life of Muhammad | ||

| Date | Age | Event |

| c. 570 | – | Death of his father, Abdullah |

| c. 570 | 0 | Possible date of birth: 12 or 17 Rabi al Awal: in Mecca, Arabia |

| c. 577 | 6 | Death of his mother, Amina |

| c. 583 | 12–13 | His grandfather transfers him to Syria |

| c. 595 | 24–25 | Meets and marries Khadijah |

| c. 599 | 28–29 | Birth of Zainab, his first daughter, followed by: Ruqayyah, Umm Kulthum, and Fatima Zahra |

| 610 | 40 | Qur’anic revelation begins in the Cave of Hira on the Jabal an-Nour, the «Mountain of Light» near Mecca. At age 40, Angel Jebreel (Gabriel) was said to appear to Muhammad on the mountain and call him «the Prophet of Allah» |

| Begins in secret to gather followers in Mecca | ||

| c. 613 | 43 | Begins spreading message of Islam publicly to all Meccans |

| c. 614 | 43–44 | Heavy persecution of Muslims begins |

| c. 615 | 44–45 | Emigration of a group of Muslims to Ethiopia |

| c. 616 | 45–46 | Banu Hashim clan boycott begins |

| 619 | 49 | Banu Hashim clan boycott ends |

| The year of sorrows: Khadija (his wife) and Abu Talib (his uncle) die | ||

| c. 620 | 49–50 | Isra and Mi’raj (reported ascension to heaven to meet God) |

| 622 | 51–52 | Hijra, emigration to Medina (called Yathrib) |

| 624 | 53–54 | Battle of Badr |

| 625 | 54–55 | Battle of Uhud |

| 627 | 56–57 | Battle of the Trench (also known as the siege of Medina) |

| 628 | 57–58 | The Meccan tribe of Quraysh and the Muslim community in Medina sign a 10-year truce called the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah |

| 630 | 59–60 | Conquest of Mecca |

| 632 | 61–62 | Farewell pilgrimage, event of Ghadir Khumm, and death, in what is now Saudi Arabia |

|

This box:

|

Abu al-Qasim Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim[49] was born in Mecca[50] about the year 570[1] and his birthday is believed to be in the month of Rabi’ al-awwal.[51] He belonged to the Banu Hashim clan, part of the Quraysh tribe, which was one of Mecca’s prominent families, although it appears less prosperous during Muhammad’s early lifetime.[11][f] Tradition places the year of Muhammad’s birth as corresponding with the Year of the Elephant, which is named after the failed destruction of Mecca that year by the Abraha, Yemen’s king, who supplemented his army with elephants.[52][53][54]

Alternatively some 20th century scholars have suggested different years, such as 568 or 569.[6]

Muhammad’s father, Abdullah, died almost six months before he was born.[56] According to Islamic tradition, soon after birth he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert, as desert life was considered healthier for infants; some western scholars reject this tradition’s historicity.[57] Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, and her husband until he was two years old. At the age of six, Muhammad lost his biological mother Amina to illness and became an orphan.[57][58] For the next two years, until he was eight years old, Muhammad was under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, of the Banu Hashim clan until his death. He then came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib, the new leader of the Banu Hashim.[6] According to Islamic historian William Montgomery Watt there was a general disregard by guardians in taking care of weaker members of the tribes in Mecca during the 6th century, «Muhammad’s guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seem to have been declining at that time.»[59]

In his teens, Muhammad accompanied his uncle on Syrian trading journeys to gain experience in commercial trade.[59] Islamic tradition states that when Muhammad was either nine or twelve while accompanying the Meccans’ caravan to Syria, he met a Christian monk or hermit named Bahira who is said to have foreseen Muhammad’s career as a prophet of God.[60]

Little is known of Muhammad during his later youth as available information is fragmented, making it difficult to separate history from legend.[59] It is known that he became a merchant and «was involved in trade between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.»[61] Due to his upright character he acquired the nickname «al-Amin» (Arabic: الامين), meaning «faithful, trustworthy» and «al-Sadiq» meaning «truthful»[62] and was sought out as an impartial arbitrator.[11][63] His reputation attracted a proposal in 595 from Khadijah, a successful businesswoman. Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.[61]

Several years later, according to a narration collected by historian Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad was involved with a well-known story about setting the Black Stone in place in the wall of the Kaaba in 605 CE. The Black Stone, a sacred object, was removed during renovations to the Kaaba. The Meccan leaders could not agree which clan should return the Black Stone to its place. They decided to ask the next man who came through the gate to make that decision; that man was the 35-year-old Muhammad. This event happened five years before the first revelation by Gabriel to him. He asked for a cloth and laid the Black Stone in its center. The clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and together carried the Black Stone to the right spot, then Muhammad laid the stone, satisfying the honor of all.[64][65]

Beginnings of the Quran

Recite in the name of your Lord who created—Created man from a clinging substance. Recite, and your Lord is the most Generous—Who taught by the pen—Taught man that which he knew not.

— Quran 96:1–5

Muhammad began to pray alone in a cave named Hira on Mount Jabal al-Nour, near Mecca for several weeks every year.[66][67] Islamic tradition holds that during one of his visits to that cave, in the year 610 the angel Gabriel appeared to him and commanded Muhammad to recite verses that would be included in the Quran.[68] Consensus exists that the first Quranic words revealed were the beginning of Quran 96:1.[69]

Muhammad was deeply distressed upon receiving his first revelations. After returning home, Muhammad was consoled and reassured by Khadijah and her Christian cousin, Waraqah ibn Nawfal.[70] He also feared that others would dismiss his claims as being possessed. Shi’a tradition states Muhammad was not surprised or frightened at Gabriel’s appearance; rather he welcomed the angel, as if he was expected.[g] The initial revelation was followed by a three-year pause (a period known as fatra) during which Muhammad felt depressed and further gave himself to prayers and spiritual practices.[69] When the revelations resumed he was reassured and commanded to begin preaching: «Thy Guardian-Lord hath not forsaken thee, nor is He displeased.»[71][72][73]

The cave Hira in the mountain Jabal al-Nour where, according to Muslim belief, Muhammad received his first revelation

Sahih Bukhari narrates Muhammad describing his revelations as «sometimes it is (revealed) like the ringing of a bell». Aisha reported, «I saw the Prophet being inspired Divinely on a very cold day and noticed the sweat dropping from his forehead (as the Inspiration was over)».[74] According to Welch these descriptions may be considered genuine, since they are unlikely to have been forged by later Muslims.[11] Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages.[75] According to the Quran, one of the main roles of Muhammad is to warn the unbelievers of their eschatological punishment (Quran 38:70,[76] Quran 6:19).[77] Occasionally the Quran did not explicitly refer to Judgment day but provided examples from the history of extinct communities and warns Muhammad’s contemporaries of similar calamities.[78] Muhammad did not only warn those who rejected God’s revelation, but also dispensed good news for those who abandoned evil, listening to the divine words and serving God. Muhammad’s mission also involves preaching monotheism: The Quran commands Muhammad to proclaim and praise the name of his Lord and instructs him not to worship idols or associate other deities with God.[78]

The key themes of the early Quranic verses included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of the dead, God’s final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in Hell and pleasures in Paradise, and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not committing female infanticide.[11]

Opposition

The last verse from An-Najm: «So prostrate to Allah and worship.» Muhammad’s message of monotheism challenged the traditional order.

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad’s wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.[79] She was followed by Muhammad’s ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zaid.[79] Around 613, Muhammad began to preach to the public.[8][80] Most Meccans ignored and mocked him, though a few became his followers. There were three main groups of early converts to Islam: younger brothers and sons of great merchants; people who had fallen out of the first rank in their tribe or failed to attain it; and the weak, mostly unprotected foreigners.[81]

According to Ibn Saad, opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that condemned idol worship and the polytheism practiced by the Meccan forefathers.[82] However, the Quranic exegesis maintains that it began as Muhammad started public preaching.[83] As his followers increased, Muhammad became a threat to the local tribes and rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life that Muhammad threatened to overthrow. Muhammad’s denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, the Quraysh, as they were the guardians of the Kaaba.[81] Powerful merchants attempted to convince Muhammad to abandon his preaching; he was offered admission to the inner circle of merchants, as well as an advantageous marriage. He refused both of these offers.[81]

Have We not made for him two eyes? And a tongue and two lips? And have shown him the two ways? But he has not broken through the difficult pass. And what can make you know what is the difficult pass? It is the freeing of a slave. Or feeding on a day of severe hunger; an orphan of near relationship, or a needy person in misery. And then being among those who believed and advised one another to patience and advised one another to mercy.

— Quran (90:8–17)

Tradition records at great length the persecution and ill-treatment towards Muhammad and his followers.[11] Sumayyah bint Khayyat, a slave of a prominent Meccan leader Abu Jahl, is famous as the first martyr of Islam; killed with a spear by her master when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal, another Muslim slave, was tortured by Umayyah ibn Khalaf who placed a heavy rock on his chest to force his conversion.[84][85]

In 615, some of Muhammad’s followers emigrated to the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum and founded a small colony under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[11] Ibn Sa’ad mentions two separate migrations. According to him, most of the Muslims returned to Mecca prior to Hijra, while a second group rejoined them in Yathrib. Ibn Hisham and Tabari, however, only talk about one migration to Ethiopia. These accounts agree that Meccan persecution played a major role in Muhammad’s decision to suggest that a number of his followers seek refuge among the Christians in Abyssinia. According to the famous letter of ʿUrwa preserved in al-Tabari, the majority of Muslims returned to their native town as Islam gained strength and as high ranking Meccans, such as Umar and Hamzah, converted.[86]

However, there is a completely different story on the reason why the Muslims returned from Ethiopia to Mecca. According to this account—initially mentioned by Al-Waqidi then rehashed by Ibn Sa’ad and Tabari, but not by Ibn Hisham and not by Ibn Ishaq.[11] Muhammad, desperately hoping for an accommodation with his tribe, pronounced a verse acknowledging the existence of three Meccan goddesses considered to be the daughters of Allah. Muhammad retracted the verses the next day at the behest of Gabriel, claiming that the verses were whispered by the devil himself. Instead, a ridicule of these gods was offered.[87][h][i] This episode, known as «The Story of the Cranes,» is also known as «Satanic Verses». According to the story, this led to a general reconciliation between Muhammad and the Meccans, and the Abyssinia Muslims began to return home. When they arrived Gabriel had informed Muhammad that the two verses were not part of the revelation, but had been inserted by Satan. Notable scholars at the time argued against the historic authenticity of these verses and the story itself on various grounds.[88][11][j] Al-Waqidi was severely criticized by Islamic scholars such as Malik ibn Anas, al-Shafi’i, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Al-Nasa’i, al-Bukhari, Abu Dawood, Al-Nawawi and others as a liar and forger.[89][90][91][92] Later, the incident received some acceptance among certain groups, though strong objections to it continued onwards past the tenth century. The objections continued until rejection of these verses and the story itself eventually became the only acceptable orthodox Muslim position.[93]

In 616 (or 617), the leaders of Makhzum and Banu Abd-Shams, two important Quraysh clans, declared a public boycott against Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, to pressure it into withdrawing its protection of Muhammad. The boycott lasted three years but eventually collapsed as it failed in its objective.[94][95] During this time, Muhammad was able to preach only during the holy pilgrimage months in which all hostilities between Arabs were suspended.

Isra and Mi’raj

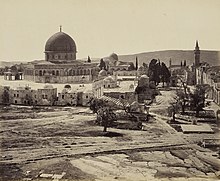

The Masjid Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem, also known as the Haram ash-Sharif or the Temple Mount, takes its name from the «farthest mosque» described in Surah 17, where Muhammad travelled in his night journey.[96]

Islamic tradition states that in 620, Muhammad experienced the Isra and Mi’raj, a miraculous night-long journey said to have occurred with the angel Gabriel. At the journey’s beginning, the Isra, he is said to have traveled from Mecca on a winged steed to «the farthest mosque.» Later, during the Mi’raj, Muhammad is said to have toured heaven and hell, and spoke with earlier prophets, such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.[citation needed] Ibn Ishaq, author of the first biography of Muhammad, presents the event as a spiritual experience; later historians, such as Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir, present it as a physical journey.[citation needed]

Some western scholars[who?] hold that the Isra and Mi’raj journey traveled through the heavens from the sacred enclosure at Mecca to the celestial al-Baytu l-Maʿmur (heavenly prototype of the Kaaba); later traditions indicate Muhammad’s journey as having been from Mecca to Jerusalem.[97][page needed]

Last years before Hijra

Quranic inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock. It marks the spot Muhammad is believed by Muslims to have ascended to heaven.[98]

Muhammad’s wife Khadijah and uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the «Year of Sorrow». With the death of Abu Talib, leadership of the Banu Hashim clan passed to Abu Lahab, a tenacious enemy of Muhammad. Soon afterward, Abu Lahab withdrew the clan’s protection over Muhammad. This placed Muhammad in danger; the withdrawal of clan protection implied that blood revenge for his killing would not be exacted. Muhammad then visited Ta’if, another important city in Arabia, and tried to find a protector, but his effort failed and further brought him into physical danger.[11][95] Muhammad was forced to return to Mecca. A Meccan man named Mut’im ibn Adi (and the protection of the tribe of Banu Nawfal) made it possible for him to safely re-enter his native city.[11][95]

Many people visited Mecca on business or as pilgrims to the Kaaba. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina).[11] The Arab population of Yathrib were familiar with monotheism and were prepared for the appearance of a prophet because a Jewish community existed there.[11] They also hoped, by the means of Muhammad and the new faith, to gain supremacy over Mecca; the Yathrib were jealous of its importance as the place of pilgrimage. Converts to Islam came from nearly all Arab tribes in Yathrib; by June of the subsequent year, seventy-five Muslims came to Mecca for pilgrimage and to meet Muhammad. Meeting him secretly by night, the group made what is known as the «Second Pledge of al-‘Aqaba«, or, in Orientalists’ view, the «Pledge of War«.[99] Following the pledges at Aqabah, Muhammad encouraged his followers to emigrate to Yathrib. As with the migration to Abyssinia, the Quraysh attempted to stop the emigration. However, almost all Muslims managed to leave.[100]

Hijra

The Hijra is the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Yathrib in 622 CE. In June 622, warned of a plot to assassinate him, Muhammad secretly slipped out of Mecca and moved his followers to Yathrib,[101] 450 kilometres (280 miles) north of Mecca.[102]

Migration to Medina

| Timeline of Muhammad in Medina | ||

|---|---|---|

| 624 | 53–54 | Invasion of Sawiq |

| Al Kudr Invasion | ||

| Raid on Dhu Amarr, Muhammad raids Ghatafan tribes | ||

| 625 | 54–55 | Battle of Uhud: Meccans defeat Muslims |

| Invasion of Hamra al-Asad, successfully terrifies the enemy to cause a retreat | ||

| Assassination of Khaled b. Sufyan | ||

| Tragedy of al Raji and Bir Maona | ||

| Banu Nadir expelled after Invasion | ||

| 626 | 55–56 | Expedition of Badr al-Maw’id, Dhat al-Riqa and Dumat al-Jandal |

| 627 | 56–57 | Battle of the Trench |

| Invasion of Banu Qurayza, successful siege | ||

| 628 | 57–58 | Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, gains access to Kaaba |

| Conquest of the Khaybar oasis | ||

| 629 | 58–59 | First hajj pilgrimage |

| Attack on Byzantine Empire fails: Battle of Mu’tah | ||

| 630 | 59–60 | Bloodless conquest of Mecca |

| Battle of Hunayn | ||

| Siege of Ta’if | ||

| Attack on Byzantine Empire successful: Expedition of Tabuk | ||

| 631 | 60–61 | Rules most of the Arabian peninsula |

| 632 | 61–62 | Farewell hajj pilgrimage |

| Death, on June 8 in Medina | ||

|

This box:

|

A delegation, consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Yathrib, invited Muhammad to serve as chief arbitrator for the entire community; due to his status as a neutral outsider.[103][104] There was fighting in Yathrib: primarily the dispute involved its Arab and Jewish inhabitants, and was estimated to have lasted for around a hundred years before 620.[103] The recurring slaughters and disagreements over the resulting claims, especially after the Battle of Bu’ath in which all clans were involved, made it obvious to them that the tribal concept of blood-feud and an eye for an eye were no longer workable unless there was one man with authority to adjudicate in disputed cases.[103] The delegation from Yathrib pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.[11]

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Yathrib, until nearly all his followers left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure, according to tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate Muhammad. With the help of Ali, Muhammad fooled the Meccans watching him, and secretly slipped away from the town with Abu Bakr.[105] By 622, Muhammad emigrated to Yathrib, a large agricultural oasis. Those who migrated from Mecca along with Muhammad became known as muhajirun (emigrants).[11]

Establishment of a new polity

Among the first things Muhammad did to ease the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Yathrib was to draft a document known as the Constitution of Medina, «establishing a kind of alliance or federation» among the eight Yathrib tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca; this specified rights and duties of all citizens, and the relationship of the different communities in Yathrib (including the Muslim community to other communities, specifically the Jews and other «Peoples of the Book»).[103][104] The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, Ummah, had a religious outlook, also shaped by practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes.[11]

The first group of converts to Islam in Yathrib were the clans without great leaders; these clans had been subjugated by hostile leaders from outside.[106] This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Yathrib, with some exceptions. According to Ibn Ishaq, this was influenced by the conversion of Sa’d ibn Mu’adh (a prominent Yathrib leader) to Islam.[107] People of Yathrib who converted to Islam and helped the Muslim emigrants find shelter became known as the ansar (supporters).[11] Then Muhammad instituted brotherhood between the emigrants and the supporters and he chose Ali as his own brother.[108]

Beginning of armed conflict

Following the emigration, the people of Mecca seized property of Muslim emigrants to Yathrib.[109] War would later break out between the people of Mecca and the Muslims. Muhammad delivered Quranic verses permitting Muslims to fight the Meccans.[110] According to the traditional account, on 11 February 624, while praying in the Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Yathrib, Muhammad received revelations from God that he should be facing Mecca rather than Jerusalem during prayer. Muhammad adjusted to the new direction, and his companions praying with him followed his lead, beginning the tradition of facing Mecca during prayer.[111]

Permission has been given to those who are being fought, because they were wronged. And indeed, Allah is competent to give them victory. Those who have been evicted from their homes without right—only because they say, «Our Lord is Allah.» And were it not that Allah checks the people, some by means of others, there would have been demolished monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques in which the name of Allah is much mentioned. And Allah will surely support those who support Him. Indeed, Allah is Powerful and Exalted in Might.

— Quran (22:39–40)

Muhammad ordered a number of raids to capture Meccan caravans, but only the 8th of them, the Raid of Nakhla, resulted in actual fighting and capture of booty and prisoners.[112] In March 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the caravan at Badr.[113] Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. A Meccan force was sent to protect the caravan and went on to confront the Muslims upon receiving word that the caravan was safe. The Battle of Badr commenced.[114] Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans with fourteen Muslims dead. They also succeeded in killing many Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl.[115] Seventy prisoners had been acquired, many of whom were ransomed.[116][117][118] Muhammad and his followers saw the victory as confirmation of their faith[11] and Muhammad ascribed the victory to the assistance of an invisible host of angels. The Quranic verses of this period, unlike the Meccan verses, dealt with practical problems of government and issues like the distribution of spoils.[119]

The victory strengthened Muhammad’s position in Yathrib and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers.[120] As a result, the opposition to him became less vocal. Pagans who had not yet converted were very bitter about the advance of Islam. Two pagans, Asma bint Marwan of the Aws Manat tribe and Abu ‘Afak of the ‘Amr b. ‘Awf tribe, had composed verses taunting and insulting the Muslims.[121] They were killed by people belonging to their own or related clans, and Muhammad did not disapprove of the killings.[121] This report, however, is considered by some to be a fabrication.[122] Most members of those tribes converted to Islam, and little pagan opposition remained.[123]

Muhammad expelled from Yathrib the Banu Qaynuqa, one of three main Jewish tribes,[11] but some historians contend that the expulsion happened after Muhammad’s death.[124] According to al-Waqidi, after Abd-Allah ibn Ubaiy spoke for them, Muhammad refrained from executing them and commanded that they be exiled from Yathrib.[125] Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hejaz.[11]

Conflict with Mecca

The Meccans were eager to avenge their defeat. To maintain economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been reduced at Badr.[126] In the ensuing months, the Meccans sent ambush parties to Yathrib while Muhammad led expeditions against tribes allied with Mecca and sent raiders onto a Meccan caravan.[127] Abu Sufyan gathered an army of 3000 men and set out for an attack on Yathrib.[128]

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army’s presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, a dispute arose over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many senior figures suggested it would be safer to fight within Yathrib and take advantage of the heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying crops, and huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the younger Muslims and readied the Muslim force for battle. Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (the location of the Meccan camp) and fought the Battle of Uhud on 23 March 625.[129][130] Although the Muslim army had the advantage in early encounters, lack of discipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat; 75 Muslims were killed, including Hamza, Muhammad’s uncle who became one of the best known martyrs in the Muslim tradition. The Meccans did not pursue the Muslims; instead, they marched back to Mecca declaring victory. The announcement is probably because Muhammad was wounded and thought dead. When they discovered that Muhammad lived, the Meccans did not return due to false information about new forces coming to his aid. The attack had failed to achieve their aim of completely destroying the Muslims.[131][132] The Muslims buried the dead and returned to Yathrib that evening. Questions accumulated about the reasons for the loss; Muhammad delivered Quranic verses 3:152 indicating that the defeat was twofold: partly a punishment for disobedience, partly a test for steadfastness.[133]

Abu Sufyan directed his effort towards another attack on Yathrib. He gained support from the nomadic tribes to the north and east of Yathrib; using propaganda about Muhammad’s weakness, promises of booty, memories of Quraysh prestige and through bribery.[134] Muhammad’s new policy was to prevent alliances against him. Whenever alliances against Yathrib were formed, he sent out expeditions to break them up.[134] Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Yathrib, and reacted in a severe manner.[135] One example is the assassination of Ka’b ibn al-Ashraf, a chieftain of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir. Al-Ashraf went to Mecca and wrote poems that roused the Meccans’ grief, anger and desire for revenge after the Battle of Badr.[136][137] Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Banu Nadir from Yathrib[138] forcing their emigration to Syria; he allowed them to take some possessions, as he was unable to subdue the Banu Nadir in their strongholds. The rest of their property was claimed by Muhammad in the name of God as it was not gained with bloodshed. Muhammad surprised various Arab tribes, individually, with overwhelming force, causing his enemies to unite to annihilate him. Muhammad’s attempts to prevent a confederation against him were unsuccessful, though he was able to increase his own forces and stopped many potential tribes from joining his enemies.[139]

Battle of the Trench

With the help of the exiled Banu Nadir, the Quraysh military leader Abu Sufyan mustered a force of 10,000 men. Muhammad prepared a force of about 3,000 men and adopted a form of defense unknown in Arabia at that time; the Muslims dug a trench wherever Yathrib lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman the Persian. The siege of Yathrib began on 31 March 627 and lasted two weeks.[140] Abu Sufyan’s troops were unprepared for the fortifications, and after an ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to return home.[k] The Quran discusses this battle in sura Al-Ahzab, in verses 33:9–27.[83]

During the battle, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, located to the south of Yathrib, entered into negotiations with Meccan forces to revolt against Muhammad. Although the Meccan forces were swayed by suggestions that Muhammad was sure to be overwhelmed, they desired reassurance in case the confederacy was unable to destroy him. No agreement was reached after prolonged negotiations, partly due to sabotage attempts by Muhammad’s scouts.[141] After the coalition’s retreat, the Muslims accused the Banu Qurayza of treachery and besieged them in their forts for 25 days. The Banu Qurayza eventually surrendered; according to Ibn Ishaq, all the men apart from a few converts to Islam were beheaded, while the women and children were enslaved.[142][143] Walid N. Arafat and Barakat Ahmad have disputed the accuracy of Ibn Ishaq’s narrative.[144] Arafat believes that Ibn Ishaq’s Jewish sources, speaking over 100 years after the event, conflated this account with memories of earlier massacres in Jewish history; he notes that Ibn Ishaq was considered an unreliable historian by his contemporary Malik ibn Anas, and a transmitter of «odd tales» by the later Ibn Hajar.[145] Ahmad argues that only some of the tribe were killed, while some of the fighters were merely enslaved.[146][147] Watt finds Arafat’s arguments «not entirely convincing», while Meir J. Kister has contradicted[clarification needed] the arguments of Arafat and Ahmad.[148]

In the siege of Yathrib, the Meccans exerted the available strength to destroy the Muslim community. The failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria vanished.[149] Following the Battle of the Trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north, both ended without any fighting.[11] While returning from one of these journeys (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad’s wife. Aisha was exonerated from accusations when Muhammad announced he had received a revelation confirming Aisha’s innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses (sura 24, An-Nur).[150] Following the battle, Muhammad renamed Yathrib to Taybah.[151][152]

Truce of Hudaybiyyah

«In your name, O God!

This is the treaty of peace between Muhammad Ibn Abdullah and Suhayl Ibn Amr. They have agreed to allow their arms to rest for ten years. During this time each party shall be secure, and neither shall injure the other; no secret damage shall be inflicted, but honesty and honour shall prevail between them. Whoever in Arabia wishes to enter into a treaty or covenant with Muhammad can do so, and whoever wishes to enter into a treaty or covenant with the Quraysh can do so. And if a Qurayshite comes without the permission of his guardian to Muhammad, he shall be delivered up to the Quraysh; but if, on the other hand, one of Muhammad’s people comes to the Quraysh, he shall not be delivered up to Muhammad. This year, Muhammad, with his companions, must withdraw from Mecca, but next year, he may come to Mecca and remain for three days, yet without their weapons except those of a traveller; the swords remaining in their sheaths.»

—The statement of the treaty of Hudaybiyyah[153]

Although Muhammad had delivered Quranic verses commanding the Hajj,[154] the Muslims had not performed it due to Quraysh enmity. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to prepare for a pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision when he was shaving his head after completion of the Hajj.[155] Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh dispatched 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, enabling his followers to reach al-Hudaybiyya just outside Mecca.[156] According to Watt, although Muhammad’s decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream, he was also demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam did not threaten the prestige of the sanctuaries, that Islam was an Arabian religion.[156]

The Kaaba in Mecca long held a major economic and religious role for the area. Seventeen months after Muhammad’s arrival in Medina, it became the Muslim Qibla, or direction for prayer (salat). The Kaaba has been rebuilt several times; the present structure, built in 1629, is a reconstruction of an earlier building dating to 683.[157]

Negotiations commenced with emissaries traveling to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad called upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the «Pledge of Acceptance» or the «Pledge under the Tree». News of Uthman’s safety allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh.[156][158] The main points of the treaty included: cessation of hostilities, the deferral of Muhammad’s pilgrimage to the following year, and agreement to send back any Meccan who emigrated to Taybah without permission from their protector.[156]

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the treaty. However, the Quranic sura «Al-Fath» (The Victory) assured them that the expedition must be considered a victorious one.[159] It was later that Muhammad’s followers realized the benefit behind the treaty. These benefits included the requirement of the Meccans to identify Muhammad as an equal, cessation of military activity allowing Taybah to gain strength, and the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the pilgrimage rituals.[11]

After signing the truce, Muhammad assembled an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar, known as the Battle of Khaybar. This was possibly due to housing the Banu Nadir who were inciting hostilities against Muhammad, or to regain prestige from what appeared as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya.[128][160] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date is given variously in the sources).[11][161][162] He sent messengers (with letters) to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Khosrau of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others.[161][162] In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad directed his forces against the Arabs on Transjordanian Byzantine soil in the Battle of Mu’tah.[163]

Final years

Conquest of Mecca

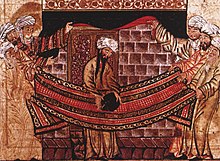

A depiction of Muhammad (with veiled face) advancing on Mecca from Siyer-i Nebi, a 16th-century Ottoman manuscript. The angels Gabriel, Michael, Israfil and Azrail, are also shown.

The truce of Hudaybiyyah was enforced for two years.[164][165] The tribe of Banu Khuza’a had good relations with Muhammad, whereas their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had allied with the Meccans.[164][165] A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuza’a, killing a few of them.[164][165] The Meccans helped the Banu Bakr with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting.[164] After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were: either the Meccans would pay blood money for the slain among the Khuza’ah tribe, they disavow themselves of the Banu Bakr, or they should declare the truce of Hudaybiyyah null.[166]

The Meccans replied that they accepted the last condition.[166] Soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Sufyan to renew the Hudaybiyyah treaty, a request that was declined by Muhammad.

Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[167] In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with 10,000 Muslim converts. With minimal casualties, Muhammad seized control of Mecca.[168] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who were «guilty of murder or other offences or had sparked off the war and disrupted the peace».[169] Some of these were later pardoned.[170] Most Meccans converted to Islam and Muhammad proceeded to destroy all the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba.[171] According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad personally spared paintings or frescos of Mary and Jesus, but other traditions suggest that all pictures were erased.[172] The Quran discusses the conquest of Mecca.[83][173]

Conquest of Arabia

Conquests of Muhammad (green lines) and the Rashidun caliphs (black lines). Shown: Byzantine empire (North and West) & Sassanid-Persian empire (Northeast).

Following the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were raising an army double the size of Muhammad’s. The Banu Hawazin were old enemies of the Meccans. They were joined by the Banu Thaqif (inhabiting the city of Ta’if) who adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans.[174] Muhammad defeated the Hawazin and Thaqif tribes in the Battle of Hunayn.[11]

In the same year, Muhammad organized an attack against northern Arabia because of their previous defeat at the Battle of Mu’tah and reports of hostility adopted against Muslims. With great difficulty he assembled 30,000 men; half of whom on the second day returned with Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy, untroubled by the damning verses which Muhammad hurled at them. Although Muhammad did not engage with hostile forces at Tabuk, he received the submission of some local chiefs of the region.[11][175]

He also ordered the destruction of any remaining pagan idols in Eastern Arabia. The last city to hold out against the Muslims in Western Arabia was Taif. Muhammad refused to accept the city’s surrender until they agreed to convert to Islam and allowed men to destroy the statue of their goddess Al-Lat.[112][176][177]

A year after the Battle of Tabuk, the Banu Thaqif sent emissaries to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many bedouins submitted to Muhammad to safeguard against his attacks and to benefit from the spoils of war.[11] However, the bedouins were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain independence: namely their code of virtue and ancestral traditions. Muhammad required a military and political agreement according to which they «acknowledge the suzerainty of Medina, to refrain from attack on the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religious levy.»[178]

Farewell pilgrimage

In 632, at the end of the tenth year after migration to Yathrib, Muhammad completed his first true Islamic pilgrimage, setting precedent for the annual Great Pilgrimage, known as Hajj.[11] On the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah Muhammad delivered his Farewell Sermon, at Mount Arafat east of Mecca. In this sermon, Muhammad advised his followers not to follow certain pre-Islamic customs. For instance, he said a white has no superiority over a black, nor a black any superiority over a white except by piety and good action.[179] He abolished old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system and asked for old pledges to be returned as implications of the creation of the new Islamic community. Commenting on the vulnerability of women in his society, Muhammad asked his male followers to «be good to women, for they are powerless captives (awan) in your households. You took them in God’s trust, and legitimated your sexual relations with the Word of God, so come to your senses people, and hear my words …» He told them that they were entitled to discipline their wives but should do so with kindness. He addressed the issue of inheritance by forbidding false claims of paternity or of a client relationship to the deceased and forbade his followers to leave their wealth to a testamentary heir. He also upheld the sacredness of four lunar months in each year.[180][181] According to Sunni tafsir, the following Quranic verse was delivered during this event: «Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you».[182][11] According to Shia tafsir, it refers to the appointment of Ali ibn Abi Talib at the pond of Khumm as Muhammad’s successor, this occurring a few days later when Muslims were returning from Mecca to Taybah.[l]

Death and tomb

A few months after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with fever, head pain, and weakness. He died on Monday, 8 June 632, in Taybah, at the age of 62 or 63, in the house of his wife Aisha.[183] With his head resting on Aisha’s lap, he asked her to dispose of his last worldly goods (seven coins), then spoke his final words:

O Allah, to Ar-Rafiq Al-A’la (exalted friend, highest Friend or the uppermost, highest Friend in heaven).[184][185][186]

— Muhammad

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, Muhammad’s death may be presumed to have been caused by Medinan fever exacerbated by physical and mental fatigue.[187] Academics Reşit Haylamaz and Fatih Harpci say that Ar-Rafiq Al-A’la is referring to God.[188]

Muhammad was buried where he died in Aisha’s house.[11][189][190] During the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, al-Masjid an-Nabawi (the Mosque of the Prophet) was expanded to include the site of Muhammad’s tomb.[191] The Green Dome above the tomb was built by the Mamluk sultan Al Mansur Qalawun in the 13th century, although the green color was added in the 16th century, under the reign of Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[192] Among tombs adjacent to that of Muhammad are those of his companions (Sahabah), the first two Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar, and an empty one that Muslims believe awaits Jesus.[190][193][194]

When Saud bin Abdul-Aziz took Medina in 1805, Muhammad’s tomb was stripped of its gold and jewel ornamentation.[195] Adherents to Wahhabism, Saud’s followers, destroyed nearly every tomb dome in Medina in order to prevent their veneration,[195] and the one of Muhammad is reported to have narrowly escaped.[196] Similar events took place in 1925, when the Saudi militias retook—and this time managed to keep—the city.[197][198][199] In the Wahhabi interpretation of Islam, burial is to take place in unmarked graves.[196] Although the practice is frowned upon by the Saudis, many pilgrims continue to practice a ziyarat—a ritual visit—to the tomb.[200][201]

After Muhammad

Expansion of the caliphate, 622–750 CE:

Muhammad, 622–632 CE.

Rashidun caliphate, 632–661 CE.

Umayyad caliphate, 661–750 CE.

Muhammad united several of the tribes of Arabia into a single Arab Muslim religious polity in the last years of his life. With Muhammad’s death, disagreement broke out over who his successor would be.[12][13] Umar ibn al-Khattab, a prominent companion of Muhammad, nominated Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s friend and collaborator. With additional support Abu Bakr was confirmed as the first caliph. This choice was disputed by some of Muhammad’s companions, who held that Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, had been designated the successor by Muhammad at Ghadir Khumm. Abu Bakr immediately moved to strike against the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman Empire) forces because of the previous defeat, although he first had to put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in an event that Muslim historians later referred to as the Ridda wars, or «Wars of Apostasy».[m]

The pre-Islamic Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sassanian empires. The Roman–Persian Wars between the two had devastated the region, making the empires unpopular amongst local tribes. Furthermore, in the lands that would be conquered by Muslims many Christians (Nestorians, Monophysites, Jacobites and Copts) were disaffected from the Eastern Orthodox Church which deemed them heretics. Within a decade Muslims conquered Mesopotamia, Byzantine Syria, Byzantine Egypt,[202] large parts of Persia, and established the Rashidun Caliphate.

According to William Montgomery Watt, religion for Muhammad was not a private and individual matter but «the total response of his personality to the total situation in which he found himself. He was responding [not only]… to the religious and intellectual aspects of the situation but also to the economic, social, and political pressures to which contemporary Mecca was subject.»[203] Bernard Lewis says there are two important political traditions in Islam—Muhammad as a statesman in Medina, and Muhammad as a rebel in Mecca. In his view, Islam is a great change, akin to a revolution, when introduced to new societies.[204]

Historians generally agree that Islamic social changes in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery and the rights of women and children improved on the status quo of Arab society.[204][n] For example, according to Lewis, Islam «from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents».[which?][204] Muhammad’s message transformed society and moral orders of life in the Arabian Peninsula; society focused on the changes to perceived identity, world view, and the hierarchy of values.[205][page needed]

Economic reforms addressed the plight of the poor, which was becoming an issue in pre-Islamic Mecca.[206] The Quran requires payment of an alms tax (zakat) for the benefit of the poor; as Muhammad’s power grew he demanded that tribes who wished to ally with him implement the zakat in particular.[207][208]

Appearance

In Muhammad al-Bukhari’s book Sahih al-Bukhari, in Chapter 61, Hadith 57[209] & Hadith 60,[210] Muhammad is depicted by two of his companions thus:

God’s Messenger was neither very tall nor short, neither absolutely white nor deep brown. His hair was neither curly nor lank. God sent him (as a Messenger) when he was forty years old. Afterwards he resided in Mecca for ten years and in Medina for ten more years. When God took him unto Him, there was scarcely twenty white hairs in his head and beard.

— Anas

The Prophet was of moderate height having broad shoulders (long) hair reaching his ear-lobes. Once I saw him in a red cloak and I had never seen anyone more handsome than him.

— Al-Bara

The description given in Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi’s book Shama’il al-Mustafa, attributed to Ali ibn Abi Talib and Hind ibn Abi Hala is as follows:[211][212][213]

Muhammad was middle-sized, did not have lank or crisp hair, was not fat, had a white circular face, wide black eyes, and long eye-lashes. When he walked, he walked as though he went down a declivity. He had the «seal of prophecy» between his shoulder blades … He was bulky. His face shone like the moon. He was taller than middling stature but shorter than conspicuous tallness. He had thick, curly hair. The plaits of his hair were parted. His hair reached beyond the lobe of his ear. His complexion was azhar [bright, luminous]. Muhammad had a wide forehead, and fine, long, arched eyebrows which did not meet. Between his eyebrows there was a vein which distended when he was angry. The upper part of his nose was hooked; he was thick bearded, had smooth cheeks, a strong mouth, and his teeth were set apart. He had thin hair on his chest. His neck was like the neck of an ivory statue, with the purity of silver. Muhammad was proportionate, stout, firm-gripped, even of belly and chest, broad-chested and broad-shouldered.

The «seal of prophecy» between Muhammad’s shoulders is generally described as having been a type of raised mole the size of a pigeon’s egg.[212] Another description of Muhammad was provided by Umm Ma’bad, a woman he met on his journey to Medina:[214][215]

I saw a man, pure and clean, with a handsome face and a fine figure. He was not marred by a skinny body, nor was he overly small in the head and neck. He was graceful and elegant, with intensely black eyes and thick eyelashes. There was a huskiness in his voice, and his neck was long. His beard was thick, and his eyebrows were finely arched and joined together.

When silent, he was grave and dignified, and when he spoke, glory rose up and overcame him. He was from afar the most beautiful of men and the most glorious, and close up he was the sweetest and the loveliest. He was sweet of speech and articulate, but not petty or trifling. His speech was a string of cascading pearls, measured so that none despaired of its length, and no eye challenged him because of brevity. In company he is like a branch between two other branches, but he is the most flourishing of the three in appearance, and the loveliest in power. He has friends surrounding him, who listen to his words. If he commands, they obey implicitly, with eagerness and haste, without frown or complaint.

Descriptions like these were often reproduced in calligraphic panels (Turkish: hilye), which in the 17th century developed into an art form of their own in the Ottoman Empire.[214]

Household

Muhammad’s life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca (from 570 to 622), and post-hijra in Yathrib/Taybah (from 622 until 632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives in total (although two have ambiguous accounts, Rayhana bint Zayd and Maria al-Qibtiyya, as wife or concubine[o][216]). Eleven of the thirteen marriages occurred after the migration to Yathrib.

At the age of 25, Muhammad married the wealthy Khadijah bint Khuwaylid who was 40 years old.[217] The marriage lasted for 25 years and was a happy one.[218] Muhammad did not enter into marriage with another woman during this marriage.[219][220] After Khadijah’s death, Khawla bint Hakim suggested to Muhammad that he should marry Sawda bint Zama, a Muslim widow, or Aisha, daughter of Um Ruman and Abu Bakr of Mecca. Muhammad is said to have asked for arrangements to marry both.[150] Muhammad’s marriages after the death of Khadijah were contracted mostly for political or humanitarian reasons. The women were either widows of Muslims killed in battle and had been left without a protector, or belonged to important families or clans with whom it was necessary to honor and strengthen alliances.[221]

According to traditional sources, Aisha was six or seven years old when betrothed to Muhammad,[150][222][223] with the marriage not being consummated until she reached the age of nine or ten years old.[p] She was therefore a virgin at marriage.[222] Modern Muslim authors who calculate Aisha’s age based on other sources of information, such as a hadith about the age difference between Aisha and her sister Asma, estimate that she was over thirteen and perhaps in her late teens at the time of her marriage.[q]

After migration to Yathrib, Muhammad, who was then in his fifties, married several more women.

Muhammad performed household chores such as preparing food, sewing clothes, and repairing shoes. He is also said to have had accustomed his wives to dialogue; he listened to their advice, and the wives debated and even argued with him.[235][236][237]

Khadijah is said to have had four daughters with Muhammad (Ruqayyah bint Muhammad, Umm Kulthum bint Muhammad, Zainab bint Muhammad, Fatimah Zahra) and two sons (Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad and Qasim ibn Muhammad, who both died in childhood). All but one of his daughters, Fatimah, died before him.[238] Some Shi’a scholars contend that Fatimah was Muhammad’s only daughter.[239] Maria al-Qibtiyya bore him a son named Ibrahim ibn Muhammad, but the child died when he was two years old.[238]

Nine of Muhammad’s wives survived him.[216] Aisha, who became known as Muhammad’s favourite wife in Sunni tradition, survived him by decades and was instrumental in helping assemble the scattered sayings of Muhammad that form the Hadith literature for the Sunni branch of Islam.[150]

Muhammad’s descendants through Fatimah are known as sharifs, syeds or sayyids. These are honorific titles in Arabic, sharif meaning ‘noble’ and sayed or sayyid meaning ‘lord’ or ‘sir’. As Muhammad’s only descendants, they are respected by both Sunni and Shi’a, though the Shi’a place much more emphasis and value on their distinction.[240]

Zayd ibn Haritha was a slave that Muhammad bought, freed, and then adopted as his son. He also had a wetnurse.[241] According to a BBC summary, «the Prophet Muhammad did not try to abolish slavery, and bought, sold, captured, and owned slaves himself. But he insisted that slave owners treat their slaves well and stressed the virtue of freeing slaves. Muhammad treated slaves as human beings and clearly held some in the highest esteem».[242]

Legacy

Islamic tradition

Following the attestation to the oneness of God, the belief in Muhammad’s prophethood is the main aspect of the Islamic faith. Every Muslim proclaims in Shahadah: «I testify that there is no god but God, and I testify that Muhammad is a Messenger of God.» The Shahadah is the basic creed or tenet of Islam. Islamic belief is that ideally the Shahadah is the first words a newborn will hear; children are taught it immediately and it will be recited upon death. Muslims repeat the shahadah in the call to prayer (adhan) and the prayer itself. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.[243]

In Islamic belief, Muhammad is regarded as the last prophet sent by God.[244][245] Qur’an 10:37 states that «…it (the Quran) is a confirmation of (revelations) that went before it, and a fuller explanation of the Book—wherein there is no doubt—from The Lord of the Worlds.» Similarly, 46:12 states «…And before this was the book of Moses, as a guide and a mercy. And this Book confirms (it)…», while Quran 2:136 commands the believers of Islam to «Say: we believe in God and that which is revealed unto us, and that which was revealed unto Abraham and Ishmael and Isaac and Jacob and the tribes, and that which Moses and Jesus received, and which the prophets received from their Lord. We make no distinction between any of them, and unto Him we have surrendered.»

Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several miracles or supernatural events.[246] For example, many Muslim commentators and some Western scholars have interpreted the Surah 54:1–2 as referring to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh when they began persecuting his followers.[247][248] Western historian of Islam Denis Gril believes the Quran does not overtly describe Muhammad performing miracles, and the supreme miracle of Muhammad is identified with the Quran itself.[247]

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad was attacked by the people of Ta’if and was badly injured. The tradition also describes an angel appearing to him and offering retribution against the assailants. It is said that Muhammad rejected the offer and prayed for the guidance of the people of Ta’if.[249]

Calligraphic rendering of «may God honor him and grant him peace», customarily added after Muhammad’s name, encoded as a ligature at Unicode code point U+FDFA.[250] ﷺ.

The Sunnah represents actions and sayings of Muhammad (preserved in reports known as Hadith) and covers a broad array of activities and beliefs ranging from religious rituals, personal hygiene, and burial of the dead to the mystical questions involving the love between humans and God. The Sunnah is considered a model of emulation for pious Muslims and has to a great degree influenced the Muslim culture. The greeting that Muhammad taught Muslims to offer each other, «may peace be upon you» (Arabic: as-salamu ‘alaykum) is used by Muslims throughout the world. Many details of major Islamic rituals such as daily prayers, the fasting and the annual pilgrimage are only found in the Sunnah and not the Quran.[251]

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad’s life, his intercession and of his miracles have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry. Among Arabic odes to Muhammad, Qasidat al-Burda («Poem of the Mantle») by the Egyptian Sufi al-Busiri (1211–1294) is particularly well-known, and widely held to possess a healing, spiritual power.[252] The Quran refers to Muhammad as «a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds»[253][11] The association of rain with mercy in Oriental countries has led to imagining Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessings and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth.[r][11] Muhammad’s birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Islamic world, excluding Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged.[254] When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad, they usually follow it with the Arabic phrase ṣallā llahu ʿalayhi wa-sallam (may God honor him and grant him peace) or the English phrase peace be upon him.[255] In casual writing, the abbreviations SAW (for the Arabic phrase) or PBUH (for the English phrase) are sometimes used; in printed matter, a small calligraphic rendition is commonly used (ﷺ).

Sufism

The Sunnah contributed much to the development of Islamic law, particularly from the end of the first Islamic century.[256]

Muslim mystics, known as sufis, who were seeking for the inner meaning of the Quran and the inner nature of Muhammad, viewed the prophet of Islam not only as a prophet but also as a perfect human being. All Sufi orders trace their chain of spiritual descent back to Muhammad.[257]

Depictions

In line with the hadith’s prohibition against creating images of sentient living beings, which is particularly strictly observed with respect to God and Muhammad, Islamic religious art is focused on the word.[258][259] Muslims generally avoid depictions of Muhammad, and mosques are decorated with calligraphy and Quranic inscriptions or geometrical designs, not images or sculptures.[258][260] Today, the interdiction against images of Muhammad—designed to prevent worship of Muhammad, rather than God—is much more strictly observed in Sunni Islam (85%–90% of Muslims) and Ahmadiyya Islam (1%) than among Shias (10%–15%).[261] While both Sunnis and Shias have created images of Muhammad in the past,[262] Islamic depictions of Muhammad are rare.[258] They have mostly been limited to the private and elite medium of the miniature, and since about 1500 most depictions show Muhammad with his face veiled, or symbolically represent him as a flame.[260][263]

Muhammad’s entry into Mecca and the destruction of idols. Muhammad is shown as a flame in this manuscript. Found in Bazil’s Hamla-i Haydari, Jammu and Kashmir, India, 1808.

The earliest extant depictions come from 13th century Anatolian Seljuk and Ilkhanid Persian miniatures, typically in literary genres describing the life and deeds of Muhammad.[263][264] During the Ilkhanid period, when Persia’s Mongol rulers converted to Islam, competing Sunni and Shi’a groups used visual imagery, including images of Muhammad, to promote their particular interpretation of Islam’s key events.[265] Influenced by the Buddhist tradition of representational religious art predating the Mongol elite’s conversion, this innovation was unprecedented in the Islamic world, and accompanied by a «broader shift in Islamic artistic culture away from abstraction toward representation» in «mosques, on tapestries, silks, ceramics, and in glass and metalwork» besides books.[266] In the Persian lands, this tradition of realistic depictions lasted through the Timurid dynasty until the Safavids took power in the early 16th century.[265] The Safavaids, who made Shi’i Islam the state religion, initiated a departure from the traditional Ilkhanid and Timurid artistic style by covering Muhammad’s face with a veil to obscure his features and at the same time represent his luminous essence.[267] Concomitantly, some of the unveiled images from earlier periods were defaced.[265][268][269] Later images were produced in Ottoman Turkey and elsewhere, but mosques were never decorated with images of Muhammad.[262] Illustrated accounts of the night journey (mi’raj) were particularly popular from the Ilkhanid period through the Safavid era.[270] During the 19th century, Iran saw a boom of printed and illustrated mi’raj books, with Muhammad’s face veiled, aimed in particular at illiterates and children in the manner of graphic novels. Reproduced through lithography, these were essentially «printed manuscripts».[270] Today, millions of historical reproductions and modern images are available in some Muslim-majority countries, especially Turkey and Iran, on posters, postcards, and even in coffee-table books, but are unknown in most other parts of the Islamic world, and when encountered by Muslims from other countries, they can cause considerable consternation and offense.[262][263]

European appreciation

Muhammad in La vie de Mahomet by M. Prideaux (1699). He holds a sword and a crescent while trampling on a globe, a cross, and the Ten Commandments.

After the Reformation, Muhammad was often portrayed in a similar way.[11][271] Guillaume Postel was among the first to present a more positive view of Muhammad when he argued that Muhammad should be esteemed by Christians as a valid prophet.[11][272] Gottfried Leibniz praised Muhammad because «he did not deviate from the natural religion».[11] Henri de Boulainvilliers, in his Vie de Mahomed which was published posthumously in 1730, described Muhammad as a gifted political leader and a just lawmaker.[11] He presents him as a divinely inspired messenger whom God employed to confound the bickering Oriental Christians, to liberate the Orient from the despotic rule of the Romans and Persians, and to spread the knowledge of the unity of God from India to Spain.[273] Voltaire had a somewhat mixed opinion on Muhammad: in his play Le fanatisme, ou Mahomet le Prophète he vilifies Muhammad as a symbol of fanaticism, and in a published essay in 1748 he calls him «a sublime and hearty charlatan», but in his historical survey Essai sur les mœurs, he presents him as legislator and a conqueror and calls him an «enthusiast.»[273] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Social Contract (1762), «brushing aside hostile legends of Muhammad as a trickster and impostor, presents him as a sage legislator who wisely fused religious and political powers.»[273] Emmanuel Pastoret published in 1787 his Zoroaster, Confucius and Muhammad, in which he presents the lives of these three «great men», «the greatest legislators of the universe», and compares their careers as religious reformers and lawgivers. He rejects the common view that Muhammad is an impostor and argues that the Quran proffers «the most sublime truths of cult and morals»; it defines the unity of God with an «admirable concision.» Pastoret writes that the common accusations of his immorality are unfounded: on the contrary, his law enjoins sobriety, generosity, and compassion on his followers: the «legislator of Arabia» was «a great man.»[273] Napoleon Bonaparte admired Muhammad and Islam,[274] and described him as a model lawmaker and a great man.[275][276] Thomas Carlyle in his book On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History (1841) describes «Mahomet» as «A silent great soul; he was one of those who cannot but be in earnest».[277] Carlyle’s interpretation has been widely cited by Muslim scholars as a demonstration that Western scholarship validates Muhammad’s status as a great man in history.[278]

Ian Almond says that German Romantic writers generally held positive views of Muhammad: «Goethe’s ‘extraordinary’ poet-prophet, Herder’s nation builder (…) Schlegel’s admiration for Islam as an aesthetic product, enviably authentic, radiantly holistic, played such a central role in his view of Mohammed as an exemplary world-fashioner that he even used it as a scale of judgement for the classical (the dithyramb, we are told, has to radiate pure beauty if it is to resemble ‘a Koran of poetry’).»[279] After quoting Heinrich Heine, who said in a letter to some friend that «I must admit that you, great prophet of Mecca, are the greatest poet and that your Quran… will not easily escape my memory», John Tolan goes on to show how Jews in Europe in particular held more nuanced views about Muhammad and Islam, being an ethnoreligious minority feeling discriminated, they specifically lauded Al-Andalus, and thus, «writing about Islam was for Jews a way of indulging in a fantasy world, far from the persecution and pogroms of nineteenth-century Europe, where Jews could live in harmony with their non-Jewish neighbors.»[280]

Recent writers such as William Montgomery Watt and Richard Bell dismiss the idea that Muhammad deliberately deceived his followers, arguing that Muhammad «was absolutely sincere and acted in complete good faith»[281] and Muhammad’s readiness to endure hardship for his cause, with what seemed to be no rational basis for hope, shows his sincerity.[282] Watt, however, says that sincerity does not directly imply correctness: in contemporary terms, Muhammad might have mistaken his subconscious for divine revelation.[283] Watt and Bernard Lewis argue that viewing Muhammad as a self-seeking impostor makes it impossible to understand Islam’s development.[284][285] Alford T. Welch holds that Muhammad was able to be so influential and successful because of his firm belief in his vocation.[11]

Other religions

Followers of the Baháʼí Faith venerate Muhammad as one of a number of prophets or «Manifestations of God». He is thought to be the final manifestation, or seal of the Adamic cycle, but consider his teachings to have been superseded by those of Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí faith, and the first manifestation of the current cycle.[286][287]

Druze tradition honors several «mentors» and «prophets»,[288] and Muhammad is considered an important prophet of God in the Druze faith, being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[289][290]

Criticism

Criticism of Muhammad has existed since the 7th century, when Muhammad was decried by his non-Muslim Arab contemporaries for preaching monotheism, and by the Jewish tribes of Arabia for his perceived appropriation of Biblical narratives and figures and proclamation of himself as the «Seal of the Prophets».[291][292]

During the Middle Ages, various Western and Byzantine Christian thinkers criticized Muhammad’s morality, and labelled him a false prophet or even the Antichrist, and he was frequently portrayed in Christendom as being either a heretic or as being possessed by demons.[293][294][295][296]

Modern religious and secular criticism of Islam has concerned Muhammad’s sincerity in claiming to be a prophet, his morality, his marriages, his ownership of slaves, his treatment of his enemies, his handling of doctrinal matters and his psychological condition.[293][297][298][299]

See also

- Ashtiname of Muhammad

- Arabian tribes that interacted with Muhammad

- Diplomatic career of Muhammad

- Glossary of Islam

- List of founders of religious traditions

- List of notable Hijazis

- Muhammad and the Bible

- Muhammad in film

- Muhammad’s views on Christians

- Possessions of Muhammad

- Relics of Muhammad

Notes