This article is about the Italian language. For the regional varieties of standard Italian, see Regional Italian.

| Italian | |

|---|---|

| italiano, lingua italiana | |

| Pronunciation | [itaˈljaːno] |

| Native to | Italy, San Marino, Vatican City, Switzerland |

| Region | Italian Peninsula, Ticino and Italian Grisons, Slovenian Littoral, Western Istria |

| Ethnicity | Italians |

| Speakers | Native: 65 million (2012)[1] L2: 3.1 million[1] Total: 68 million[1] |

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Old Latin

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

Latin (Italian alphabet) Italian Braille |

|

Signed forms |

Italiano segnato «(Signed Italian)»[2] italiano segnato esatto «(Signed Exact Italian)»[3] |

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

4 countries

2 regions

An order and various organisations

|

|

Recognised minority |

Bosnia and Herzegovina[a] |

| Regulated by | Accademia della Crusca (de facto) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | it |

| ISO 639-2 | ita |

| ISO 639-3 | ita |

| Glottolog | ital1282 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-q |

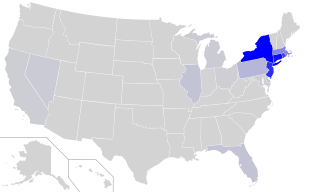

Official language Former co-official language Presence of Italian-speaking communities |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

Italian (italiano [itaˈljaːno] (listen) or lingua italiana [ˈliŋɡwa itaˈljaːna]) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin.[6][7][8][9] Spoken by about 85 million people (2022), Italian is an official language in Italy, Switzerland (Ticino and the Grisons), San Marino, and Vatican City. It has an official minority status in western Istria (Croatia and Slovenia).

Italian is also spoken by large immigrant and expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia.[1] Italian is included under the languages covered by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Romania, although Italian is neither a co-official nor a protected language in these countries.[5][10] Many speakers of Italian are native bilinguals of both Italian (either in its standard form or regional varieties) and another regional language of Italy.[1]

Italian is a major language in Europe, being one of the official languages of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and one of the working languages of the Council of Europe. It is the second-most-widely spoken native language in the European Union with 67 million speakers (15% of the EU population) and it is spoken as a second language by 13.4 million EU citizens (3%).[11][12] Including Italian speakers in non-EU European countries (such as Switzerland, Albania and the United Kingdom) and on other continents, the total number of speakers is approximately 85 million.[13] Italian is the main working language of the Holy See, serving as the lingua franca (common language) in the Roman Catholic hierarchy as well as the official language of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. Italian has a significant use in musical terminology and opera with numerous Italian words referring to music that have become international terms taken into various languages worldwide.[14] Italian was adopted by the state after the Unification of Italy, having previously been a literary language based on Tuscan as spoken mostly by the upper class of Florentine society.[15] Almost all native Italian words end with vowels and has a 7-vowel sound system (‘e’ and ‘o’ have mid-low and mid-high sounds). Italian has contrast between short and long consonants and gemination (doubling) of consonants.

History[edit]

«History of Italian» redirects here. For the history of the Italian people, see Italians. For the history of the Italian culture, see culture of Italy.

Origins[edit]

During the Middle Ages, the established written language in Europe was Latin, though the great majority of people were illiterate, and only a handful were well versed in the language. In the Italian Peninsula, as in most of Europe, most would instead speak a local vernacular. These dialects, as they are commonly referred to, evolved from Vulgar Latin over the course of centuries, unaffected by formal standards and teachings. They are not in any sense «dialects» of standard Italian, which itself started off as one of these local tongues, but sister languages of Italian. Mutual intelligibility with Italian varies widely, as it does with Romance languages in general. The Romance languages of Italy can differ greatly from Italian at all levels (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicon, pragmatics) and are classified typologically as distinct languages.[16][17]

The standard Italian language has a poetic and literary origin in the writings of Tuscan and Sicilian writers of the 12th century, and, even though the grammar and core lexicon are basically unchanged from those used in Florence in the 13th century,[18] the modern standard of the language was largely shaped by relatively recent events. However, Romance vernacular as language spoken in the Italian Peninsula has a longer history. In fact, the earliest surviving texts that can definitely be called vernacular (as distinct from its predecessor Vulgar Latin) are legal formulae known as the Placiti Cassinesi from the Province of Benevento that date from 960 to 963, although the Veronese Riddle, probably from the 8th or early 9th century, contains a late form of Vulgar Latin that can be seen as a very early sample of a vernacular dialect of Italy. The Commodilla catacomb inscription is also a similar case.

The Italian language has progressed through a long and slow process, which started after the Western Roman Empire’s fall in the 5th century.[19]

The language that came to be thought of as Italian developed in central Tuscany and was first formalized in the early 14th century through the works of Tuscan writer Dante Alighieri, written in his native Florentine. Dante’s epic poems, known collectively as the Commedia, to which another Tuscan poet Giovanni Boccaccio later affixed the title Divina, were read throughout the peninsula and his written dialect became the «canonical standard» that all educated Italians could understand. Dante is still credited with standardizing the Italian language. In addition to the widespread exposure gained through literature, the Florentine dialect also gained prestige due to the political and cultural significance of Florence at the time and the fact that it was linguistically an intermediate between the northern and the southern Italian dialects.[16]: 22 Thus the dialect of Florence became the basis for what would become the official language of Italy.

Italian was progressively made an official language of most of the Italian states predating unification, slowly replacing Latin, even when ruled by foreign powers (like Spain in the Kingdom of Naples, or Austria in the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia), even though the masses kept speaking primarily their local vernaculars. Italian was also one of the many recognised languages in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Italy has always had a distinctive dialect for each city because the cities, until recently, were thought of as city-states. Those dialects now have considerable variety. As Tuscan-derived Italian came to be used throughout Italy, features of local speech were naturally adopted, producing various versions of Regional Italian. The most characteristic differences, for instance, between Roman Italian and Milanese Italian are syntactic gemination of initial consonants in some contexts and the pronunciation of stressed «e», and of «s» between vowels in many words: e.g. va bene «all right» is pronounced [vabˈbɛːne] by a Roman (and by any standard Italian speaker), [vaˈbeːne] by a Milanese (and by any speaker whose native dialect lies to the north of the La Spezia–Rimini Line); a casa «at home» is [akˈkaːsa] for Roman, [akˈkaːsa] or [akˈkaːza] for standard, [aˈkaːza] for Milanese and generally northern.[20]

In contrast to the Gallo-Italic linguistic panorama of Northern Italy, the Italo-Dalmatian, Neapolitan and its related dialects were largely unaffected by the Franco-Occitan influences introduced to Italy mainly by bards from France during the Middle Ages, but after the Norman conquest of southern Italy, Sicily became the first Italian land to adopt Occitan lyric moods (and words) in poetry. Even in the case of Northern Italian languages, however, scholars are careful not to overstate the effects of outsiders on the natural indigenous developments of the languages.

The economic might and relatively advanced development of Tuscany at the time (Late Middle Ages) gave its language weight, though Venetian remained widespread in medieval Italian commercial life, and Ligurian (or Genoese) remained in use in maritime trade alongside the Mediterranean. The increasing political and cultural relevance of Florence during the periods of the rise of the Medici Bank, humanism, and the Renaissance made its dialect, or rather a refined version of it, a standard in the arts.

Renaissance[edit]

The Renaissance era, known as il Rinascimento in Italian, was seen as a time of rebirth, which is the literal meaning of both renaissance (from French) and rinascimento (Italian).

Pietro Bembo was an influential figure in the development of the Italian language from the Tuscan dialect, as a literary medium, codifying the language for standard modern usage.

During this time, long-existing beliefs stemming from the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church began to be understood from new perspectives as humanists—individuals who placed emphasis on the human body and its full potential—began to shift focus from the church to human beings themselves.[21] The continual advancements in technology play a crucial role in the diffusion of languages. After the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century, the number of printing presses in Italy grew rapidly and by the year 1500 reached a total of 56, the biggest number of printing presses in all of Europe. This enabled the production of more pieces of literature at a lower cost and as the dominant language, Italian, spread.[22]

Italian became the language used in the courts of every state in the Italian Peninsula, as well as the prestige variety used on the island of Corsica[23] (but not in the neighboring Sardinia, which on the contrary underwent Italianization well into the late 18th century, under Savoyard sway: the island’s linguistic composition, roofed by the prestige of Spanish among the Sardinians, would therein make for a rather slow process of assimilation to the Italian cultural sphere[24][25]). The rediscovery of Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia, as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. This discussion, known as questione della lingua (i. e., the problem of the language), ran through the Italian culture until the end of the 19th century, often linked to the political debate on achieving a united Italian state. Renaissance scholars divided into three main factions:

- The purists, headed by Venetian Pietro Bembo (who, in his Gli Asolani, claimed the language might be based only on the great literary classics, such as Petrarch and some part of Boccaccio). The purists thought the Divine Comedy was not dignified enough because it used elements from non-lyric registers of the language.

- Niccolò Machiavelli and other Florentines preferred the version spoken by ordinary people in their own times.

- The courtiers, like Baldassare Castiglione and Gian Giorgio Trissino, insisted that each local vernacular contribute to the new standard.

A fourth faction claimed that the best Italian was the one that the papal court adopted, which was a mixture of the Tuscan and Roman dialects.[26] Eventually, Bembo’s ideas prevailed, and the foundation of the Accademia della Crusca in Florence (1582–1583), the official legislative body of the Italian language, led to publication of Agnolo Monosini’s Latin tome Floris italicae linguae libri novem in 1604 followed by the first Italian dictionary in 1612.

Modern era[edit]

An important event that helped the diffusion of Italian was the conquest and occupation of Italy by Napoleon in the early 19th century (who was himself of Italian-Corsican descent). This conquest propelled the unification of Italy some decades after and pushed the Italian language into a lingua franca used not only among clerks, nobility, and functionaries in the Italian courts but also by the bourgeoisie.

Contemporary times[edit]

Alessandro Manzoni set the basis for the modern Italian language and helping create linguistic unity throughout Italy.[27]

Italian literature’s first modern novel, I promessi sposi (The Betrothed) by Alessandro Manzoni, further defined the standard by «rinsing» his Milanese «in the waters of the Arno» (Florence’s river), as he states in the preface to his 1840 edition.

After unification, a huge number of civil servants and soldiers recruited from all over the country introduced many more words and idioms from their home languages—ciao is derived from the Venetian word s-cia[v]o («slave», that is «your servant»), panettone comes from the Lombard word panetton, etc. Only 2.5% of Italy’s population could speak the Italian standardized language properly when the nation was unified in 1861.[1]

Classification[edit]

Italian is a Romance language, a descendant of Vulgar Latin (colloquial spoken Latin). Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, especially its Florentine dialect, and is therefore an Italo-Dalmatian language, a classification that includes most other central and southern Italian languages and the extinct Dalmatian.

According to Ethnologue, lexical similarity is 89% with French, 87% with Catalan, 85% with Sardinian, 82% with Spanish, 80% with Portuguese, 78% with Ladin, 77% with Romanian.[1] Estimates may differ according to sources.[28][29]

One study (analyzing the degree of differentiation of Romance languages in comparison to Latin (comparing phonology, inflection, discourse, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation) estimated that distance between Italian and Latin is higher than that between Sardinian and Latin.[30] In particular, its vowels are the second-closest to Latin after Sardinian.[31][32] As in most Romance languages, stress is distinctive.[33]

Geographic distribution[edit]

A map showing the Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland: darker areas indicate where Italian is most prominent

Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries’ populations. Italian is the third most spoken language in Switzerland (after German and French), though its use there has moderately declined since the 1970s.[34] It is official both on the national level and on regional level in two cantons: Ticino and the Grisons. In the latter canton, however, it is only spoken by a small minority, in the Italian Grisons.[b] Ticino, which includes Lugano, the largest Italian-speaking city outside Italy, is the only canton where Italian is predominant.[35] Italian is also used in administration and official documents in Vatican City.[36]

Italian is also spoken by a minority in Monaco and France, especially in the southeastern part of the country.[37][1] Italian was the official language in Savoy and in Nice until 1860, when they were both annexed by France under the Treaty of Turin, a development that triggered the «Niçard exodus», the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.[38] Italian was the official language of Corsica until 1859.[39] Italian is generally understood in Corsica by the population resident therein who speak Corsican, which is an Italo-Romance idiom similar to Tuscan.[40] Italian was the official language in Monaco until 1860, when it was replaced by the French.[41] This was due to the annexation of the surrounding County of Nice to France following the Treaty of Turin (1860).[41]

It formerly had official status in Montenegro (because of the Venetian Albania), parts of Slovenia and Croatia (because of the Venetian Istria and Venetian Dalmatia), parts of Greece (because of the Venetian rule in the Ionian Islands and by the Kingdom of Italy in the Dodecanese). Italian is widely spoken in Malta, where nearly two-thirds of the population can speak it fluently.[42] Italian served as Malta’s official language until 1934, when it was abolished by the British colonial administration amid strong local opposition.[43] Italian language in Slovenia is an officially recognized minority language in the country.[44] The official census, carried out in 2002, reported 2,258 ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians) in Slovenia (0.11% of the total population).[45] Italian language in Croatia is an official minority language in the country, with many schools and public announcements published in both languages.[44] The 2001 census in Croatia reported 19,636 ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) in the country (some 0.42% of the total population).[46] Their numbers dropped dramatically after World War II following the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, which caused the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians.[47][48] Italian was the official language of the Republic of Ragusa from 1492 to 1807.[49]

It formerly had official status in Albania due to the annexation of the country to the Kingdom of Italy (1939–1943). Albania has a large population of non-native speakers, with over half of the population having some knowledge of the Italian language.[50] The Albanian government has pushed to make Italian a compulsory second language in schools.[51] The Italian language is well-known and studied in Albania,[52] due to its historical ties and geographical proximity to Italy and to the diffusion of Italian television in the country.[53]

Due to heavy Italian influence during the Italian colonial period, Italian is still understood by some in former colonies such as in Libya.[1] Although it was the primary language in Libya since colonial rule, Italian greatly declined under the rule of Muammar Gaddafi, who expelled the Italian Libyan population and made Arabic the sole official language of the country.[54] A few hundred Italian settlers returned to Libya in the 2000s.

Italian was the official language of Eritrea during Italian colonisation. Italian is today used in commerce, and it is still spoken especially among elders; besides that, Italian words are incorporated as loan words in the main language spoken in the country (Tigrinya). The capital city of Eritrea, Asmara, still has several Italian schools, established during the colonial period. In the early 19th century, Eritrea was the country with the highest number of Italians abroad, and the Italian Eritreans grew from 4,000 during World War I to nearly 100,000 at the beginning of World War II.[55] In Asmara there are two Italian schools, the Italian School of Asmara (Italian primary school with a Montessori department) and the Liceo Sperimentale «G. Marconi» (Italian international senior high school).

Italian was also introduced to Somalia through colonialism and was the sole official language of administration and education during the colonial period but fell out of use after government, educational and economic infrastructure were destroyed in the Somali Civil War.

Italian is also spoken by large immigrant and expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia.[1] Although over 17 million Americans are of Italian descent, only a little over one million people in the United States speak Italian at home.[56] Nevertheless, an Italian language media market does exist in the country.[57] In Canada, Italian is the second most spoken non-official language when varieties of Chinese are not grouped together, with 375,645 claiming Italian as their mother tongue in 2016.[58]

Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. According to some sources, Italian is the second most spoken language in Argentina[59] after the official language of Spanish, although its number of speakers, mainly of the older generation, is decreasing. Italian bilingual speakers can be found scattered across the Southeast of Brazil as well as in the South,[1] In Venezuela, Italian is the most spoken language after Spanish and Portuguese, with around 200,000 speakers.[60] In Uruguay, people that speak Italian as their home language is 1.1% of the total population of the country.[61] In Australia, Italian is the second most spoken foreign language after Chinese, with 1.4% of the population speaking it as their home language.[62]

The main Italian-language newspapers published outside Italy are the L’Osservatore Romano (Vatican City), the L’Informazione di San Marino (San Marino), the Corriere del Ticino and the laRegione Ticino (Switzerland), the La Voce del Popolo (Croatia), the Corriere d’Italia (Germany), the L’italoeuropeo (United Kingdom), the Passaparola (Luxembourg), the America Oggi (United States), the Corriere Canadese and the Corriere Italiano (Canada), the Il punto d’incontro (Mexico), the L’Italia del Popolo (Argentina), the Fanfulla (Brazil), the Gente d’Italia (Uruguay), the La Voce d’Italia (Venezuela), the Il Globo (Australia) and the La gazzetta del Sud Africa (South Africa).[63][64][65]

Education[edit]

Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In the 21st century, technology also allows for the continual spread of the Italian language, as people have new ways to learn how to speak, read, and write languages at their own pace and at any given time. For example, the free website and application Duolingo has 4.94 million English speakers learning the Italian language.[66]

According to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, every year there are more than 200,000 foreign students who study the Italian language; they are distributed among the 90 Institutes of Italian Culture that are located around the world, in the 179 Italian schools located abroad, or in the 111 Italian lecturer sections belonging to foreign schools where Italian is taught as a language of culture.[67]

Influence and derived languages[edit]

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, thousands of Italians settled in Argentina, Uruguay, Southern Brazil and Venezuela, as well as in Canada and the United States, where they formed a physical and cultural presence.

In some cases, colonies were established where variants of regional languages of Italy were used, and some continue to use this regional language. Examples are Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where Talian is used, and the town of Chipilo near Puebla, Mexico; each continues to use a derived form of Venetian dating back to the nineteenth century. Another example is Cocoliche, an Italian–Spanish pidgin once spoken in Argentina and especially in Buenos Aires, and Lunfardo.

Lingua franca[edit]

Starting in late medieval times in much of Europe and the Mediterranean, Latin was replaced as the primary commercial language by Italian language variants (especially Tuscan and Venetian). These variants were consolidated during the Renaissance with the strength of Italy and the rise of humanism and the arts.

During that period, Italy held artistic sway over the rest of Europe. It was the norm for all educated gentlemen to make the Grand Tour, visiting Italy to see its great historical monuments and works of art. It thus became expected to learn at least some Italian. In England, while the classical languages Latin and Greek were the first to be learned, Italian became the second most common modern language after French, a position it held until the late 18th century when it tended to be replaced by German. John Milton, for instance, wrote some of his early poetry in Italian.

Within the Catholic Church, Italian is known by a large part of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and is used in substitution for Latin in some official documents.

Italian loanwords continue to be used in most languages in matters of art and music (especially classical music including opera), in the design and fashion industries, in some sports like football[68] and especially in culinary terms.

Languages and dialects[edit]

Linguistic map of Italy according to Clemente Merlo and Carlo Tagliavini (1937)

Italy’s ethno-linguistic minorities.[69]

In Italy, almost all the other languages spoken as the vernacular—other than standard Italian and some languages spoken among immigrant communities—are often called «Italian dialects», a label that can be very misleading if it is understood to mean «dialects of Italian». The Romance dialects of Italy are local evolutions of spoken Latin that pre-date the establishment of Italian, and as such are sister languages to the Tuscan that was the historical source of Italian. They can be quite different from Italian and from each other, with some belonging to different linguistic branches of Romance. The only exceptions to this are twelve groups considered «historical language minorities», which are officially recognized as distinct minority languages by the law. On the other hand, Corsican (a language spoken on the French island of Corsica) is closely related to medieval Tuscan, from which Standard Italian derives and evolved.

The differences in the evolution of Latin in the different regions of Italy can be attributed to the natural changes that all languages in regular use are subject to, and to some extent to the presence of three other types of languages: substrata, superstrata, and adstrata. The most prevalent were substrata (the language of the original inhabitants), as the Italian dialects were most likely simply Latin as spoken by native cultural groups. Superstrata and adstrata were both less important. Foreign conquerors of Italy that dominated different regions at different times left behind little to no influence on the dialects. Foreign cultures with which Italy engaged in peaceful relations with, such as trade, had no significant influence either.[16]: 19-20

Throughout Italy, regional variations of Standard Italian, called Regional Italian, are spoken. Regional differences can be recognized by various factors: the openness of vowels, the length of the consonants, and influence of the local language (for example, in informal situations andà, annà and nare replace the standard Italian andare in the area of Tuscany, Rome and Venice respectively for the infinitive «to go»).

There is no definitive date when the various Italian variants of Latin—including varieties that contributed to modern Standard Italian—began to be distinct enough from Latin to be considered separate languages. One criterion for determining that two language variants are to be considered separate languages rather than variants of a single language is that they have evolved so that they are no longer mutually intelligible; this diagnostic is effective if mutual intelligibility is minimal or absent (e.g. in Romance, Romanian and Portuguese), but it fails in cases such as Spanish-Portuguese or Spanish-Italian, as educated native speakers of either pairing can understand each other well if they choose to do so; however, the level of intelligibility is markedly lower between Italian-Spanish, and considerably higher between the Iberian sister languages of Portuguese-Spanish. Speakers of this latter pair can communicate with one another with remarkable ease, each speaking to the other in his own native language without slang/jargon. Nevertheless, on the basis of accumulated differences in morphology, syntax, phonology, and to some extent lexicon, it is not difficult to identify that for the Romance varieties of Italy, the first extant written evidence of languages that can no longer be considered Latin comes from the ninth and tenth centuries C.E. These written sources demonstrate certain vernacular characteristics and sometimes explicitly mention the use of the vernacular in Italy. Full literary manifestations of the vernacular began to surface around the 13th century in the form of various religious texts and poetry.[16]: 21 Although these are the first written records of Italian varieties separate from Latin, the spoken language had likely diverged long before the first written records appear, since those who were literate generally wrote in Latin even if they spoke other Romance varieties in person.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of Standard Italian became increasingly widespread and was mirrored by a decline in the use of the dialects. An increase in literacy was one of the main driving factors (one can assume that only literates were capable of learning Standard Italian, whereas those who were illiterate had access only to their native dialect). The percentage of literates rose from 25% in 1861 to 60% in 1911, and then on to 78.1% in 1951. Tullio De Mauro, an Italian linguist, has asserted that in 1861 only 2.5% of the population of Italy could speak Standard Italian. He reports that in 1951 that percentage had risen to 87%. The ability to speak Italian did not necessarily mean it was in everyday use, and most people (63.5%) still usually spoke their native dialects. In addition, other factors such as mass emigration, industrialization, and urbanization, and internal migrations after World War II, contributed to the proliferation of Standard Italian. The Italians who emigrated during the Italian diaspora beginning in 1861 were often of the uneducated lower class, and thus the emigration had the effect of increasing the percentage of literates, who often knew and understood the importance of Standard Italian, back home in Italy. A large percentage of those who had emigrated also eventually returned to Italy, often more educated than when they had left.[16]: 35

The Italian dialects have declined in the modern era, as Italy unified under Standard Italian and continues to do so aided by mass media, from newspapers to radio to television.[16]: 37

Phonology[edit]

Luke 2, 1–7 of the Bible being read by a speaker of Italian from Milan

Consonant phonemes

Labial Dental/

alveolarPost-

alveolar/

palatalVelar Nasal m n ɲ Stop p b t d k ɡ Affricate t͡s d͡z t͡ʃ d͡ʒ Fricative f v s z ʃ (ʒ) Approximant j w Lateral l ʎ Trill r Notes:

- Between two vowels, or between a vowel and an approximant (/j, w/) or a liquid (/l, r/), consonants can be both singleton or geminated. Geminated consonants shorten the preceding vowel (or block phonetic lengthening) and the first geminated element is unreleased. For example, compare /fato/ [ˈfaːto] (‘fate’) with /fatto/ [ˈfatto] (‘fact’).[70] However, /ɲ/, /ʃ/, /ʎ/, /dz/, /ts/ are always geminated intervocalically.[71] Similarly, nasals, liquids, and sibilants are pronounced slightly longer in medial consonant clusters.[72]

- /j/, /w/, and /z/ are the only consonants that cannot be geminated.

- /t, d/ are laminal denti-alveolar [t̪, d̪],[73][74][71] commonly called «dental» for simplicity.

- /k, ɡ/ are pre-velar before /i, e, ɛ, j/.[74]

- /t͡s, d͡z, s, z/ have two variants:

- Dentalized laminal alveolar [t̪͡s̪, d̪͡z̪, s̪, z̪][73][75] (commonly called «dental» for simplicity), pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the upper front teeth, with the tip of the tongue resting behind lower front teeth.[75]

- Non-retracted apical alveolar [t͡s̺, d͡z̺, s̺, z̺].[75] The stop component of the «apical» affricates is actually laminal denti-alveolar.[75]

- /n, l, r/ are apical alveolar [n̺, l̺, r̺] in most environments.[73][71][76] /n, l/ are laminal denti-alveolar [n̪, l̪] before /t, d, t͡s, d͡z, s, z/[71][77][78] and palatalized laminal postalveolar [n̠ʲ, l̠ʲ] before /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ, ʃ/.[79][80][dubious – discuss] /n/ is velar [ŋ] before /k, ɡ/.[81][82]

- /m/ and /n/ do not contrast before /p, b/ and /f, v/, where they are pronounced [m] and [ɱ], respectively.[81][83]

- /ɲ/ and /ʎ/ are alveolo-palatal.[84] In a large number of accents, /ʎ/ is a fricative [ʎ̝].[85]

- Intervocalically, single /r/ is realised as a trill with one or two contacts.[86] Some literature treats the single-contact trill as a tap [ɾ].[87][88] Single-contact trills can also occur elsewhere, particularly in unstressed syllables.[89] Geminate /rr/ manifests as a trill with three to seven contacts.[86]

- The phonetic distinction between [s] and [z] is neutralized before consonants and at the beginning of words: the former is used before voiceless consonants and before vowels at the beginning of words; the latter is used before voiced consonants. The two can contrast only between vowels within a word, e.g. [ˈfuːzo] ‘melted’ vs. [ˈfuːso] ‘spindle’. According to Canepari,[88] though, the traditional standard has been replaced by a modern neutral pronunciation which always prefers /z/ when intervocalic, except when the intervocalic s is the initial sound of a word, if the compound is still felt as such: for example, presento /preˈsɛnto/[90] (‘I foresee’, with pre meaning ‘before’ and sento meaning ‘I perceive’) vs presento /preˈzɛnto/[91] (‘I present’). There are many words for which dictionaries now indicate that both pronunciations, either [z] or [s], are acceptable. Word-internally between vowels, both phonemes have merged in many regional varieties of Italian, as either /z/ (Northern-Central) or /s/ (Southern-Central).

Italian has a seven-vowel system, consisting of /a, ɛ, e, i, ɔ, o, u/, as well as 23 consonants. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian phonology is conservative, preserving many words nearly unchanged from Vulgar Latin. Some examples:

- Italian quattordici «fourteen» < Latin quattuordecim (cf. Spanish catorce, French quatorze /katɔʁz/, Catalan and Portuguese catorze)

- Italian settimana «week» < Latin septimāna (cf. Romanian săptămână, Spanish and Portuguese semana, French semaine /səmɛn/, Catalan setmana)

- Italian medesimo «same» < Vulgar Latin *medi(p)simum (cf. Spanish mismo, Portuguese mesmo, French même /mɛm/, Catalan mateix; note that Italian usually prefers the shorter stesso)

- Italian guadagnare «to win, earn, gain» < Vulgar Latin *guadaniāre < Germanic /waidanjan/ (cf. Spanish ganar, Portuguese ganhar, French gagner /ɡaɲe/, Catalan guanyar)

The conservative nature of Italian phonology is partly explained by its origin. Italian stems from a literary language that is derived from the 13th-century speech of the city of Florence in the region of Tuscany, and has changed little in the last 700 years or so. Furthermore, the Tuscan dialect is the most conservative of all Italian dialects, radically different from the Gallo-Italian languages less than 160 kilometres (100 mi) to the north (across the La Spezia–Rimini Line).

The following are some of the conservative phonological features of Italian, as compared with the common Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese, Galician, Catalan). Some of these features are also present in Romanian.

- Little or no phonemic lenition of consonants between vowels, e.g. vīta > vita «life» (cf. Romanian viață, Spanish vida [ˈbiða], French vie), pedem > piede «foot» (cf. Spanish pie, French pied /pje/).

- Preservation of geminate consonants, e.g. annum > /ˈan.no/ anno «year» (cf. Spanish año /ˈaɲo/, French an /ɑ̃/, Romanian an, Portuguese ano /ˈɐnu/).

- Preservation of all Proto-Romance final vowels, e.g. pacem > pace «peace» (cf. Romanian pace, Spanish paz, French paix /pɛ/), octō > otto «eight» (cf. Romanian opt, Spanish ocho, French huit /ɥi(t)/), fēcī > feci «I did» (cf. Romanian dialectal feci, Spanish hice, French fis /fi/).

- Preservation of most intertonic vowels (those between the stressed syllable and either the beginning or ending syllable). This accounts for some of the most noticeable differences, as in the forms quattordici and settimana given above.

- Slower consonant development, e.g. folia > Italo-Western /fɔʎʎa/ > foglia /ˈfɔʎʎa/ «leaf» (cf. Romanian foaie /ˈfo̯aje/, Spanish hoja /ˈoxa/, French feuille /fœj/; but note Portuguese folha /ˈfoʎɐ/).

Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has many inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e.g. laxāre > lasciare and lassare, captiāre > cacciare and cazzare, (ex)dēroteolāre > sdrucciolare, druzzolare and ruzzolare, rēgīna > regina and reina. Although in all these examples the second form has fallen out of usage, the dimorphism is thought to reflect the several-hundred-year period during which Italian developed as a literary language divorced from any native-speaking population, with an origin in 12th/13th-century Tuscan but with many words borrowed from languages farther to the north, with different sound outcomes. (The La Spezia–Rimini Line, the most important isogloss in the entire Romance-language area, passes only about 30 kilometres or 20 miles north of Florence.) Dual outcomes of Latin /p t k/ between vowels, such as lŏcum > luogo but fŏcum > fuoco, was once thought to be due to borrowing of northern voiced forms, but is now generally viewed as the result of early phonetic variation within Tuscany.

Some other features that distinguish Italian from the Western Romance languages:

- Latin ce-,ci- becomes /tʃe, tʃi/ rather than /(t)se, (t)si/.

- Latin -ct- becomes /tt/ rather than /jt/ or /tʃ/: octō > otto «eight» (cf. Spanish ocho, French huit, Portuguese oito).

- Vulgar Latin -cl- becomes cchi /kkj/ rather than /ʎ/: oclum > occhio «eye» (cf. Portuguese olho /ˈoʎu/, French œil /œj/ < /œʎ/); but Romanian ochi /okʲ/.

- Final /s/ is not preserved, and vowel changes rather than /s/ are used to mark the plural: amico, amici «male friend(s)», amica, amiche «female friend(s)» (cf. Romanian amic, amici and amică, amice; Spanish amigo(s) «male friend(s)», amiga(s) «female friend(s)»); trēs, sex → tre, sei «three, six» (cf. Romanian trei, șase; Spanish tres, seis).

Standard Italian also differs in some respects from most nearby Italian languages:

- Perhaps most noticeable is the total lack of metaphony, though metaphony is a feature characterizing nearly every other Italian language.

- No simplification of original /nd/, /mb/ (which often became /nn/, /mm/ elsewhere).

Assimilation[edit]

Italian phonotactics do not usually permit verbs and polysyllabic nouns to end with consonants, except in poetry and song, so foreign words may receive extra terminal vowel sounds.

Writing system[edit]

Italian has a shallow orthography, meaning very regular spelling with an almost one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. The most important of the few exceptions are the following (see below for more details):

- The letter c represents the sound /k/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /tʃ/ (as the first sound in the English word chair) before the letters e and i.

- The letter g represents the sound /ɡ/ at the end of words and before the letters a, o, and u but represents the sound /dʒ/ (as the first sound in the English word gem) before the letters e and i.

- The letter n represents the phoneme /n/, which is pronounced [ŋ] (as in the English word sink or the name Ringo) before the letters c and g when these represent velar plosives /k/ or /g/, as in banco [ˈbaŋko], fungo [ˈfuŋɡo]. The letter q represents /k/ pronounced [k], thus n also represents [ŋ] in the position preceding it: cinque [ˈt͡ʃiŋkwe]. Elsewhere the letter n represents /n/ pronounced [n], including before the affricates /t͡ʃ/ or /d͡ʒ/ (equivalent to the consonants of English church and judge) spelled with c or g before the letters i and e : mancia [ˈmant͡ʃa], mangia [ˈmand͡ʒa].

- The letter h is always silent: hotel /oˈtɛl/; hanno ‘they have’ and anno ‘year’ both represent /ˈanno/. It is used to form a digraph with c or g to represent /k/ or /g/ before i or e: chi /ki/ ‘who’, che /ke/ ‘what’; aghi /ˈagi/ ‘needles’, ghetto /ˈgetto/.

- The spellings ci and gi represent only /tʃ/ (as in English church) or /dʒ/ (as in English judge) with no /i/ sound before another vowel (ciuccio /ˈtʃuttʃo/ ‘pacifier’, Giorgio /ˈdʒɔrdʒo/) unless c or g precede stressed /i/ (farmacia /farmaˈtʃia/ ‘pharmacy’, biologia /bioloˈdʒia/ ‘biology’). Elsewhere ci and gi represent /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ followed by /i/: cibo /ˈtʃibo/ ‘food’, baci /ˈbatʃi/ ‘kisses’; gita /ˈdʒita/ ‘trip’, Tamigi /taˈmidʒi/ ‘Thames’.*

The Italian alphabet is typically considered to consist of 21 letters. The letters j, k, w, x, y are traditionally excluded, though they appear in loanwords such as jeans, whisky, taxi, xenofobo, xilofono. The letter ⟨x⟩ has become common in standard Italian with the prefix extra-, although (e)stra- is traditionally used; it is also common to use the Latin particle ex(-) to mean «former(ly)» as in: la mia ex («my ex-girlfriend»), «Ex-Jugoslavia» («Former Yugoslavia»). The letter ⟨j⟩ appears in the first name Jacopo and in some Italian place-names, such as Bajardo, Bojano, Joppolo, Jerzu, Jesolo, Jesi, Ajaccio, among others, and in Mar Jonio, an alternative spelling of Mar Ionio (the Ionian Sea). The letter ⟨j⟩ may appear in dialectal words, but its use is discouraged in contemporary standard Italian.[92] Letters used in foreign words can be replaced with phonetically equivalent native Italian letters and digraphs: ⟨gi⟩, ⟨ge⟩, or ⟨i⟩ for ⟨j⟩; ⟨c⟩ or ⟨ch⟩ for ⟨k⟩ (including in the standard prefix kilo-); ⟨o⟩, ⟨u⟩ or ⟨v⟩ for ⟨w⟩; ⟨s⟩, ⟨ss⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨zz⟩ or ⟨cs⟩ for ⟨x⟩; and ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ for ⟨y⟩.

- The acute accent is used over word-final ⟨e⟩ to indicate a stressed front close-mid vowel, as in perché «why, because». In dictionaries, it is also used over ⟨o⟩ to indicate a stressed back close-mid vowel (azióne). The grave accent is used over word-final ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ to indicate a front open-mid vowel and a back open-mid vowel respectively, as in tè «tea» and può «(he) can». The grave accent is used over any vowel to indicate word-final stress, as in gioventù «youth». Unlike ⟨é⟩, which is a close-mid vowel, a stressed final ⟨o⟩ is almost always a back open-mid vowel (andrò), with a few exceptions, like metró, with a stressed final back close-mid vowel, making ⟨ó⟩ for the most part unnecessary outside of dictionaries. Most of the time, the penultimate syllable is stressed. But if the stressed vowel is the final letter of the word, the accent is mandatory, otherwise it is virtually always omitted. Exceptions are typically either in dictionaries, where all or most stressed vowels are commonly marked. Accents can optionally be used to disambiguate words that differ only by stress, as for prìncipi «princes» and princìpi «principles», or àncora «anchor» and ancóra «still/yet». For monosyllabic words, the rule is different: when two orthographically identical monosyllabic words with different meanings exist, one is accented and the other is not (example: è «is», e «and»).

- The letter ⟨h⟩ distinguishes ho, hai, ha, hanno (present indicative of avere «to have») from o («or»), ai («to the»), a («to»), anno («year»). In the spoken language, the letter is always silent. The ⟨h⟩ in ho additionally marks the contrasting open pronunciation of the ⟨o⟩. The letter ⟨h⟩ is also used in combinations with other letters. No phoneme /h/ exists in Italian. In nativized foreign words, the ⟨h⟩ is silent. For example, hotel and hovercraft are pronounced /oˈtɛl/ and /ˈɔverkraft/ respectively. (Where ⟨h⟩ existed in Latin, it either disappeared or, in a few cases before a back vowel, changed to [ɡ]: traggo «I pull» ← Lat. trahō.)

- The letters ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ can symbolize voiced or voiceless consonants. ⟨z⟩ symbolizes /dz/ or /ts/ depending on context, with few minimal pairs. For example: zanzara /dzanˈdzara/ «mosquito» and nazione /natˈtsjone/ «nation». ⟨s⟩ symbolizes /s/ word-initially before a vowel, when clustered with a voiceless consonant (⟨p, f, c, ch⟩), and when doubled; it symbolizes /z/ when between vowels and when clustered with voiced consonants. Intervocalic ⟨s⟩ varies regionally between /s/ and /z/, with /z/ being more dominant in northern Italy and /s/ in the south.

- The letters ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ vary in pronunciation between plosives and affricates depending on following vowels. The letter ⟨c⟩ symbolizes /k/ when word-final and before the back vowels ⟨a, o, u⟩. It symbolizes /tʃ/ as in chair before the front vowels ⟨e, i⟩. The letter ⟨g⟩ symbolizes /ɡ/ when word-final and before the back vowels ⟨a, o, u⟩. It symbolizes /dʒ/ as in gem before the front vowels ⟨e, i⟩. Other Romance languages and, to an extent, English have similar variations for ⟨c, g⟩. Compare hard and soft C, hard and soft G. (See also palatalization.)

- The digraphs ⟨ch⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ indicate (/k/ and /ɡ/) before ⟨i, e⟩. The digraphs ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ indicate «softness» (/tʃ/ and /dʒ/, the affricate consonants of English church and judge) before ⟨a, o, u⟩. For example:

-

Before back vowel (A, O, U) Before front vowel (I, E) Plosive C caramella /karaˈmɛlla/ candy CH china /ˈkina/ India ink G gallo /ˈɡallo/ rooster GH ghiro /ˈɡiro/ edible dormouse Affricate CI ciambella /tʃamˈbɛlla/ donut C Cina /ˈtʃina/ China GI giallo /ˈdʒallo/ yellow G giro /ˈdʒiro/ round, tour

- Note: ⟨h⟩ is silent in the digraphs ⟨ch⟩, ⟨gh⟩; and ⟨i⟩ is silent in the digraphs ⟨ci⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ before ⟨a, o, u⟩ unless the ⟨i⟩ is stressed. For example, it is silent in ciao /ˈtʃa.o/ and cielo /ˈtʃɛ.lo/, but it is pronounced in farmacia /ˌfar.maˈtʃi.a/ and farmacie /ˌfar.maˈtʃi.e/.[20]

Italian has geminate, or double, consonants, which are distinguished by length and intensity. Length is distinctive for all consonants except for /ʃ/, /dz/, /ts/, /ʎ/, /ɲ/, which are always geminate when between vowels, and /z/, which is always single.

Geminate plosives and affricates are realized as lengthened closures. Geminate fricatives, nasals, and /l/ are realized as lengthened continuants. There is only one vibrant phoneme /r/ but the actual pronunciation depends on context and regional accent. Generally one can find a flap consonant [ɾ] in unstressed position whereas [r] is more common in stressed syllables, but there may be exceptions. Especially people from the Northern part of Italy (Parma, Aosta Valley, South Tyrol) may pronounce /r/ as [ʀ], [ʁ], or [ʋ].[93]

Of special interest to the linguistic study of Regional Italian is the gorgia toscana, or «Tuscan Throat», the weakening or lenition of intervocalic /p/, /t/, and /k/ in the Tuscan language.

The voiced postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ is present as a phoneme only in loanwords: for example, garage [ɡaˈraːʒ]. Phonetic [ʒ] is common in Central and Southern Italy as an intervocalic allophone of /dʒ/: gente [ˈdʒɛnte] ‘people’ but la gente [laˈʒɛnte] ‘the people’, ragione [raˈʒoːne] ‘reason’.

Grammar[edit]

Italian grammar is typical of the grammar of Romance languages in general. Cases exist for personal pronouns (nominative, oblique, accusative, dative), but not for nouns.

There are two basic classes of nouns in Italian, referred to as genders, masculine and feminine. Gender may be natural (ragazzo ‘boy’, ragazza ‘girl’) or simply grammatical with no possible reference to biological gender (masculine costo ‘cost’, feminine costa ‘coast’). Masculine nouns typically end in -o (ragazzo ‘boy’), with plural marked by -i (ragazzi ‘boys’), and feminine nouns typically end in -a, with plural marked by -e (ragazza ‘girl’, ragazze ‘girls’). For a group composed of boys and girls, ragazzi is the plural, suggesting that -i is a general neutral plural. A third category of nouns is unmarked for gender, ending in -e in the singular and -i in the plural: legge ‘law, f. sg.’, leggi ‘laws, f. pl.’; fiume ‘river, m. sg.’, fiumi ‘rivers, m. pl.’, thus assignment of gender is arbitrary in terms of form, enough so that terms may be identical but of distinct genders: fine meaning ‘aim’, ‘purpose’ is masculine, while fine meaning ‘end, ending’ (e.g. of a movie) is feminine, and both are fini in the plural, a clear instance of -i as a non-gendered default plural marker. These nouns often, but not always, denote inanimates. There are a number of nouns that have a masculine singular and a feminine plural, most commonly of the pattern m. sg. -o, f. pl. -a (miglio ‘mile, m. sg.’, miglia ‘miles, f. pl.’; paio ‘pair, m. sg., paia ‘pairs, f. pl.’), and thus are sometimes considered neuter (these are usually derived from neuter Latin nouns). An instance of neuter gender also exists in pronouns of the third person singular.[94]

Examples:[95]

| Definition | Gender | Singular Form | Plural Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Son | Masculine | Figlio | Figli |

| House | Feminine | Casa | Case |

| Love | Masculine | Amore | Amori |

| Art | Feminine | Arte | Arti |

Nouns, adjectives, and articles inflect for gender and number (singular and plural).

Like in English, common nouns are capitalized when occurring at the beginning of a sentence. Unlike English, nouns referring to languages (e.g. Italian), speakers of languages, or inhabitants of an area (e.g. Italians) are not capitalized.[96]

There are three types of adjectives: descriptive, invariable and form-changing. Descriptive adjectives are the most common, and their endings change to match the number and gender of the noun they modify. Invariable adjectives are adjectives whose endings do not change. The form changing adjectives «buono (good), bello (beautiful), grande (big), and santo (saint)» change in form when placed before different types of nouns. Italian has three degrees for comparison of adjectives: positive, comparative, and superlative.[96]

The order of words in the phrase is relatively free compared to most European languages.[92] The position of the verb in the phrase is highly mobile. Word order often has a lesser grammatical function in Italian than in English. Adjectives are sometimes placed before their noun and sometimes after. Subject nouns generally come before the verb. Italian is a null-subject language, so that nominative pronouns are usually absent, with subject indicated by verbal inflections (e.g. amo ‘I love’, ama ‘(s)he loves’, amano ‘they love’). Noun objects normally come after the verb, as do pronoun objects after imperative verbs, infinitives and gerunds, but otherwise pronoun objects come before the verb.

There are both indefinite and definite articles in Italian. There are four indefinite articles, selected by the gender of the noun they modify and by the phonological structure of the word that immediately follows the article. Uno is masculine singular, used before z (/ts/ or /dz/), s+consonant, gn (/ɲ/), or ps, while masculine singular un is used before a word beginning with any other sound. The noun zio ‘uncle’ selects masculine singular, thus uno zio ‘an uncle’ or uno zio anziano ‘an old uncle,’ but un mio zio ‘an uncle of mine’. The feminine singular indefinite articles are una, used before any consonant sound, and its abbreviated form, written un’, used before vowels: una camicia ‘a shirt’, una camicia bianca ‘a white shirt’, un’altra camicia ‘a different shirt’. There are seven forms for definite articles, both singular and plural. In the singular: lo, which corresponds to the uses of uno; il, which corresponds to the uses with consonant of un; la, which corresponds to the uses of una; l’, used for both masculine and feminine singular before vowels. In the plural: gli is the masculine plural of lo and l’; i is the plural of il; and le is the plural of feminine la and l‘.[96]

There are numerous contractions of prepositions with subsequent articles. There are numerous productive suffixes for diminutive, augmentative, pejorative, attenuating, etc., which are also used to create neologisms.

There are 27 pronouns, grouped in clitic and tonic pronouns. Personal pronouns are separated into three groups: subject, object (which take the place of both direct and indirect objects), and reflexive. Second person subject pronouns have both a polite and a familiar form. These two different types of address are very important in Italian social distinctions. All object pronouns have two forms: stressed and unstressed (clitics). Unstressed object pronouns are much more frequently used, and come before a verb conjugated for subject verb (La vedi. ‘You see her.’), after (in writing, attached to) non-conjugated verbs (vendendola ‘seeing her’). Stressed object pronouns come after the verb, and are used when emphasis is required, for contrast, or to avoid ambiguity (Vedo lui, ma non lei. ‘I see him, but not her’). Aside from personal pronouns, Italian also has demonstrative, interrogative, possessive, and relative pronouns. There are two types of demonstrative pronouns: relatively near (this) and relatively far (that). Demonstratives in Italian are repeated before each noun, unlike in English.[96]

There are three regular sets of verbal conjugations, and various verbs are irregularly conjugated. Within each of these sets of conjugations, there are four simple (one-word) verbal conjugations by person/number in the indicative mood (present tense; past tense with imperfective aspect, past tense with perfective aspect, and future tense), two simple conjugations in the subjunctive mood (present tense and past tense), one simple conjugation in the conditional mood, and one simple conjugation in the imperative mood. Corresponding to each of the simple conjugations, there is a compound conjugation involving a simple conjugation of «to be» or «to have» followed by a past participle. «To have» is used to form compound conjugation when the verb is transitive («Ha detto», «ha fatto»: he/she has said, he/she has made/done), while «to be» is used in the case of verbs of motion and some other intransitive verbs («È andato», «è stato»: he has gone, he has been). «To be» may be used with transitive verbs, but in such a case it makes the verb passive («È detto», «è fatto»: it is said, it is made/done). This rule is not absolute, and some exceptions do exist.

Words[edit]

Conversation[edit]

Note: the plural form of verbs could also be used as an extremely formal (for example to noble people in monarchies) singular form (see royal we).

| English (inglese) | Italian (italiano) | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | Sì | (listen) /ˈsi/ |

| No | No | (listen) /ˈnɔ/ |

| Of course! | Certo! / Certamente! / Naturalmente! | /ˈtʃɛrto/ /ˌtʃertaˈmente/ /naturalˈmente/ |

| Hello! | Ciao! (informal) / Salve! (semi-formal) | /ˈtʃao/ |

| Cheers! | Salute! | /saˈlute/ |

| How are you? | Come stai? (informal) / Come sta? (formal) / Come state? (plural) / Come va? (general, informal) | /ˌkomeˈstai/; /ˌkomeˈsta/ /ˌkome ˈstate/ /ˌkome va/ |

| Good morning! | Buongiorno! (= Good day!) | /ˌbwɔnˈdʒorno/ |

| Good evening! | Buonasera! | /ˌbwɔnaˈsera/ |

| Good night! | Buonanotte! (for a good night sleeping) / Buona serata! (for a good night awake) | /ˌbwɔnaˈnɔtte/ /ˌbwɔna seˈrata/ |

| Have a nice day! | Buona giornata! (formal) | /ˌbwɔna dʒorˈnata/ |

| Enjoy the meal! | Buon appetito! | /ˌbwɔn‿appeˈtito/ |

| Goodbye! | Arrivederci (general) / Arrivederla (formal) / Ciao! (informal) | (listen) /arriveˈdertʃi/ |

| Good luck! | Buona fortuna! (general) | /ˌbwɔna forˈtuna/ |

| I love you | Ti amo (between lovers only) / Ti voglio bene (in the sense of «I am fond of you», between lovers, friends, relatives etc.) | /ti ˈamo/; /ti ˌvɔʎʎo ˈbɛne/ |

| Welcome [to…] | Benvenuto/-i (for male/males or mixed) / Benvenuta/-e (for female/females) [a / in…] | /benveˈnuto//benveˈnuti//benveˈnuta/ /benveˈnute/ |

| Please | Per favore / Per piacere / Per cortesia | (listen) /per faˈvore/ /per pjaˈtʃere/ /per korteˈzia/ |

| Thank you! | Grazie! (general) / Ti ringrazio! (informal) / La ringrazio! (formal) / Vi ringrazio! (plural) | /ˈɡrattsje/ /ti rinˈɡrattsjo/ |

| You are welcome! | Prego! | /ˈprɛɡo/ |

| Excuse me / I am sorry | Mi dispiace (only «I am sorry») / Scusa(mi) (informal) / Mi scusi (formal) / Scusatemi (plural) / Sono desolato («I am sorry», if male) / Sono desolata («I am sorry», if female) | /ˈskuzi/; /ˈskuza/; /mi disˈpjatʃe/ |

| Who? | Chi? | /ki/ |

| What? | Che cosa? / Cosa? / Che? | /kekˈkɔza/ or /kekˈkɔsa/ /ˈkɔza/ or /kɔsa/ /ˈke/ |

| When? | Quando? | /ˈkwando/ |

| Where? | Dove? | /ˈdove/ |

| How? | Come? | /ˈkome/ |

| Why / Because | Perché | /perˈke/ |

| Again | Di nuovo / Ancora | /di ˈnwɔvo/; /anˈkora/ |

| How much? / How many? | Quanto? / Quanta? / Quanti? / Quante? | /ˈkwanto/ |

| What is your name? | Come ti chiami? (informal) / Qual è il suo nome? (formal) / Come si chiama? (formal) | /ˌkome tiˈkjami/ /kwal ˈɛ il ˌsu.o ˈnome/ |

| My name is… | Mi chiamo… | /mi ˈkjamo/ |

| This is… | Questo è… (masculine) / Questa è… (feminine) | /ˌkwesto ˈɛ/ /ˌkwesta ˈɛ/ |

| Yes, I understand. | Sì, capisco. / Ho capito. | /si kaˈpisko/ /ɔkkaˈpito/ |

| I do not understand. | Non capisco. / Non ho capito. | (listen) /non kaˈpisko/ /nonˌɔkkaˈpito/ |

| Do you speak English? | Parli inglese? (informal) / Parla inglese? (formal) / Parlate inglese? (plural) | (listen) /parˌlate inˈɡleːse/ (listen) /ˌparla inˈɡlese/ |

| I do not understand Italian. | Non capisco l’italiano. | /non kaˌpisko litaˈljano/ |

| Help me! | Aiutami! (informal) / Mi aiuti! (formal) / Aiutatemi! (plural) / Aiuto! (general) | /aˈjutami/ /ajuˈtatemi/ /aˈjuto/ |

| You are right/wrong! | (Tu) hai ragione/torto! (informal) / (Lei) ha ragione/torto! (formal) / (Voi) avete ragione/torto! (plural) | |

| What time is it? | Che ora è? / Che ore sono? | /ke ˌora ˈɛ/ /ke ˌore ˈsono/ |

| Where is the bathroom? | Dov’è il bagno? | (listen) /doˌvɛ il ˈbaɲɲo/ |

| How much is it? | Quanto costa? | /ˌkwanto ˈkɔsta/ |

| The bill, please. | Il conto, per favore. | /il ˌkonto per faˈvore/ |

| The study of Italian sharpens the mind. | Lo studio dell’italiano aguzza l’ingegno. | /loˈstudjo dellitaˈljano aˈɡuttsa linˈdʒeɲɲo/ |

| Where are you from? | Di dove sei? (general, informal)/ Di dove è? (formal) | /di dove ssˈɛi/ /di dove ˈɛ/ |

| I like | Mi piace (for one object) / Mi piacciono (for multiple objects) | /mi pjatʃe/ /mi pjattʃono/ |

Question words[edit]

| English | Italian[96][95] | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| what (adj.) | che | /ke/ |

| what (standalone) | cosa | /ˈkɔza/, /ˈkɔsa/ |

| who | chi | /ki/ |

| how | come | /ˈkome/ |

| where | dove | /ˈdove/ |

| why, because | perché | /perˈke/ |

| which | quale | /ˈkwale/ |

| when | quando | /ˈkwando/ |

| how much | quanto | /ˈkwanto/ |

Time[edit]

| English | Italian[96][95] | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| today | oggi | /ˈɔddʒi/ |

| yesterday | ieri | /ˈjɛri/ |

| tomorrow | domani | /doˈmani/ |

| second | secondo | /seˈkondo/ |

| minute | minuto | /miˈnuto/ |

| hour | ora | /ˈora/ |

| day | giorno | /ˈdʒorno/ |

| week | settimana | /settiˈmana/ |

| month | mese | /ˈmeze/, /ˈmese/ |

| year | anno | /ˈanno/ |

Numbers[edit]

|

|

|

| English | Italian | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| one hundred | cento | /ˈtʃɛnto/ |

| one thousand | mille | /ˈmille/ |

| two thousand | duemila | /ˌdueˈmila/ |

| two thousand (and) twenty (2020) | duemilaventi | /dueˌmilaˈventi/ |

| one million | un milione | /miˈljone/ |

| one billion | un miliardo | /miˈljardo/ |

| one trillion | mille miliardi | /ˈmilleˈmiˈljardi/ |

Days of the week[edit]

| English | Italian | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | lunedì | /luneˈdi/ |

| Tuesday | martedì | /marteˈdi/ |

| Wednesday | mercoledì | /ˌmerkoleˈdi/ |

| Thursday | giovedì | /dʒoveˈdi/ |

| Friday | venerdì | /venerˈdi/ |

| Saturday | sabato | /ˈsabato/ |

| Sunday | domenica | /doˈmenika/ |

Months of the year[edit]

| English | Italian | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| January | gennaio | /dʒenˈnajo/ |

| February | febbraio | /febˈbrajo/ |

| March | marzo | /ˈmartso/ |

| April | aprile | /aˈprile/ |

| May | maggio | /ˈmaddʒo/ |

| June | giugno | /ˈdʒuɲɲo/ |

| July | luglio | /ˈluʎʎo/ |

| August | agosto | /aˈɡosto/ |

| September | settembre | /setˈtɛmbre/ |

| October | ottobre | /otˈtobre/ |

| November | novembre | /noˈvɛmbre/ |

| December | dicembre | /diˈtʃɛmbre/[97] |

See also[edit]

- Languages of Italy (includes «Italian dialects», dialetti)

- Accademia della Crusca

- CELI

- CILS (Qualification)

- Enciclopedia Italiana

- Italian alphabet

- Regional Italian

- Italian exonyms

- Italian grammar

- Italian honorifics

- List of countries and territories where Italian is an official language

- The Italian Language Foundation (in the United States)

- Italian language in Croatia

- Italian language in Slovenia

- Italian language in the United States

- Italian language in Venezuela

- Italian literature

- Italian musical terms

- Italian phonology

- Italian profanity

- Italian Sign Language

- Italian Studies

- Italian Wikipedia

- Italian-language international radio stations

- Lessico etimologico italiano

- Sicilian School

- Veronese Riddle

- Languages of the Vatican City

- Talian

- List of English words of Italian origin

- List of Italian musical terms used in English

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Recognized as a minority language by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[5]

- ^ Italian is the main language of the valleys of Calanca, Mesolcina, Bregaglia and val Poschiavo. In the village of Maloja, it is spoken by about half the population. It is also spoken by a minority in the village of Bivio.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Italian at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ «Centro documentazione per l’integrazione». Cdila.it. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «Centro documentazione per l’integrazione». Cdila.it. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «Pope Francis to receive Knights of Malta grand master Thursday – English». ANSA.it. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ a b «Languages covered by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages» (PDF). (PDF)

- ^ «Romance languages». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

…if the Romance languages are compared with Latin, it is seen that by most measures Sardinian and Italian are least differentiated…

- ^ Fleure, H. J. The peoples of Europe. ISBN 9781176926981.

- ^ «Hermathena». 1942.

- ^ Winters, Margaret E. (8 May 2020). Historical Linguistics: A cognitive grammar introduction. ISBN 9789027261236.

- ^ «MULTILINGVISM ŞI LIMBI MINORITARE ÎN ROMÂNIA» (PDF) (in Romanian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Keating, Dave. «Despite Brexit, English Remains The EU’s Most Spoken Language By Far». Forbes. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Europeans and their Languages Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Data for EU27, published in 2012.

- ^ «Italian — University of Leicester». .le.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ See List of Italian musical terms used in English

- ^ [1] Archived 3 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Lepschy, Anna Laura; Lepschy, Giulio C. (1988). The Italian language today (2nd ed.). New York: New Amsterdam. pp. 13, 22, 19–20, 21, 35, 37. ISBN 978-0-941533-22-5. OCLC 17650220.

- ^ Andreose, Alvise; Renzi, Lorenzo (2013), «Geography and distribution of the Romance Languages in Europe», in Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.), The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages, vol. 2, Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 302–308

- ^ Coletti, Vittorio (2011). «Storia della lingua». Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

L’italiano di oggi ha ancora in gran parte la stessa grammatica e usa ancora lo stesso lessico del fiorentino letterario del Trecento.

- ^ «History of the Italian language». Italian-language.biz. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 24 September 2006.

- ^ a b Berloco 2018.

- ^ P., McKay, John (2006). A history of Western society. Hill, Bennett D., Buckler, John. (8th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-52273-6. OCLC 58837884.

- ^ Dittmar, Jeremiah (2011). «Information Technology and Economic Change: The Impact of the Printing Press». The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 126 (3): 1133–1172. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr035. S2CID 11701054.

- ^ Toso, Fiorenzo. Lo spazio linguistico corso tra insularità e destino di frontiera, in Linguistica, 43, pp. 79–80, 2003

- ^ Cardia, Amos. S’italianu in Sardìnnia candu, cumenti e poita d’ant impostu : 1720–1848; poderi e lìngua in Sardìnnia in edadi spanniola , pp. 80–93, Iskra, 2006.

- ^ «La dominazione sabauda in Sardegna può essere considerata come la fase iniziale di un lungo processo di italianizzazione dell’isola, con la capillare diffusione dell’italiano in quanto strumento per il superamento della frammentarietà tipica del contesto linguistico dell’isola e con il conseguente inserimento delle sue strutture economiche e culturali in un contesto internazionale più ampio e aperto ai contatti di più lato respiro. […] Proprio la variegata composizione linguistica della Sardegna fu considerata negativamente per qualunque tentativo di assorbimento dell’isola nella sfera culturale italiana.» Loi Corvetto, Ines. I Savoia e le «vie» dell’unificazione linguistica. Quoted in Putzu, Ignazio; Mazzon, Gabriella (2012). Lingue, letterature, nazioni. Centri e periferie tra Europa e Mediterraneo, p.488.

- ^ This faction was headed by Vincenzo Calmeta, Alessandro Tassoni, according to whom “the idiom of the Roman court was as good as the Florentine one, and better understood by all” (G. Rossi, ed. (1930). La secchia rapita, L’oceano e le rime. Bari. p. 235) and Francesco Sforza Pallavicino. See: Bellini, Eraldo (2022). «Language and Idiom in Sforza Pallavicino’s Trattato dello stile e del dialogo«. Sforza Pallavicino: A Jesuit Life in Baroque Rome. Brill Publishers: 126–172. ISBN 978-90-04-51724-0.

- ^ «I Promessi sposi or The Betrothed». Archived from the original on 18 July 2011.

- ^ Brincat (2005)

- ^ «Similar languages to Italian». ezglot.com.

- ^ Pei, Mario (1949). Story of Language. ISBN 978-0-397-00400-3.

- ^ See Italica 1950: 46 (cf. [2] and [3]): «Pei, Mario A. «A New Methodology for Romance Classification.» Word, v, 2 (Aug. 1949), 135–146. Demonstrates a comparative statistical method for determining the extent of change from the Latin for the free and checked stressed vowels of French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Rumanian, Old Provençal, and Logudorese Sardinian. By assigning 3½ change points per vowel (with 2 points for diphthongization, 1 point for modification in vowel quantity, ½ point for changes due to nasalization, palatalization or umlaut, and −½ point for failure to effect a normal change), there is a maximum of 77 change points for free and checked stressed vowel sounds (11×2×3½=77). According to this system (illustrated by seven charts at the end of the article), the percentage of change is greatest in French (44%) and least in Italian (12%) and Sardinian (8%). Prof. Pei suggests that this statistical method be extended not only to all other phonological but also to all morphological and syntactical, phenomena.».

- ^ See Koutna et al. (1990: 294): «In the late forties and in the fifties some new proposals for classification of the Romance languages appeared. A statistical method attempting to evaluate the evidence quantitatively was developed in order to provide not only a classification but at the same time a measure of the divergence among the languages. The earliest attempt was made in 1949 by Mario Pei (1901–1978), who measured the divergence of seven modern Romance languages from Classical Latin, taking as his criterion the evolution of stressed vowels. Pei’s results do not show the degree of contemporary divergence among the languages from each other but only the divergence of each one from Classical Latin. The closest language turned out to be Sardinian with 8% of change. Then followed Italian — 12%; Spanish — 20%; Romanian — 23,5%; Provençal — 25%; Portuguese — 31%; French — 44%.»

- ^ «Portland State Multicultural Topics in Communications Sciences & Disorders | Italian». www.pdx.edu. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ Lüdi, Georges; Werlen, Iwar (April 2005). «Recensement Fédéral de la Population 2000 — Le Paysage Linguistique en Suisse» (PDF) (in French, German, and Italian). Neuchâtel: Office fédéral de la statistique. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2006.

- ^ Marc-Christian Riebe, Retail Market Study 2015, p. 36. «the largest city in Ticino, and the largest Italian-speaking city outside of Italy.«

- ^ The Vatican City State appendix to the Acta Apostolicae Sedis is entirely in Italian.

- ^ «Society». Monaco-IQ Business Intelligence. Lydia Porter. 2007–2013. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ ««Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell’esilio» in seguito all’unità d’Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi» (in Italian). 28 August 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Abalain, Hervé, (2007) Le français et les langues historiques de la France, Éditions Jean-Paul Gisserot, p.113

- ^ «Sardinian language, Encyclopedia Britannica».

- ^ a b «Il monegasco, una lingua che si studia a scuola ed è obbligatoria» (in Italian). 15 September 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ «Europeans and their Languages» (PDF). European Commission: Directorate General for Education and Culture and Directorate General Press and Communication. February 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ Hull, Geoffrey, The Malta Language Question: A Case Study in Cultural Imperialism, Valletta: Said International, 1993.

- ^ a b «La tutela delle minoranze linguistiche in Slovenia» (in Italian). 22 April 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ «Popis 2002». Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ «Državni Zavod za Statistiku» (in Croatian). Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ Thammy Evans & Rudolf Abraham (2013). Istria. p. 11. ISBN 9781841624457.

- ^ James M. Markham (6 June 1987). «Election Opens Old Wounds in Trieste». The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Lodge, R. Anthony; Pugh, Stefan (2007). Language contact and minority languages on the littorals of Europe. Logos Verlag. pp. 235–238. ISBN 9783832516444.

- ^ Zonova, Tatiana. «The Italian language: soft power or dolce potere?.» Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali (2013): 227–231.

- ^ «Albanian government makes Italian an obligatory language in professional schools». balkaneu.com. February 2014. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Longo, Maurizio (2007). «La lingua italiana in Albania» (PDF). Education et Sociétés Plurilingues (in Italian) (22): 51–56. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

Today, even though for political reasons English is the most widely taught foreign language in Albanian schools, Italian is anyway the most widespread foreign language.

- ^ Longo, Maurizio; Ademi, Esmeralda; Bulija, Mirjana (June 2010). «Una quantificazione della penetrazione della lingua italiana in Albania tramite la televisione (III)» [A quantification of the diffusion of the Italian language in Albania via television] (PDF). Education et Sociétés Plurilingues (in Italian) (28): 53–63. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ [4] Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Podestà, Gian Luca. «L’emigrazione italiana in Africa orientale» (PDF). Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ «Language Spoken at Home: 2000». United States Bureau of the Census. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ «Newsletter». Netcapricorn.com. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «Data tables, 2016 Census». Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ «Los segundos idiomas más hablados de Sudamérica | AméricaEconomía – El sitio de los negocios globales de América Latina». Americaeconomia.com. 16 July 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ Bernasconi, Giulia (2012). «L’ITALIANO IN VENEZUELA». Italiano LinguaDue (in Italian). Università degli Studi di Milano. 3 (2): 20. doi:10.13130/2037-3597/1921. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

L’italiano come lingua acquisita o riacquisita è largamente diffuso in Venezuela: recenti studi stimano circa 200.000 studenti di italiano nel Paese

- ^ «Encuesta Telefónica de Idiomas (ETI) 2019». Instituto Nacional de Estadística Instituto Nacional de Estadística – Uruguay. 2019. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020.

- ^ «2011 Census QuickStats: Australia». Censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «QUOTIDIANI ITALIANI ALL’ESTERO» (in Italian). Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ «Come si informano gli italiani all’estero» (in Italian). Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ «Il giornale italo-brasiliano (Fanfulla)» (in Italian). Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ «duolingo». duolingo. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ «Dati e statistiche». Esteri.it. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «Italian Language». ilsonline.it. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ «Lingue di Minoranza e Scuola: Carta Generale». Minoranze-linguistiche-scuola.it. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Hall (1944), pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c d Rogers & d’Arcangeli (2004), p. 117.

- ^ Hall (1944), p. 78.

- ^ a b c Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 132.

- ^ a b Canepari (1992), p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Canepari (1992), pp. 68, 75–76.

- ^ Canepari (1992), pp. 57, 84, 88–89.

- ^ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 133.

- ^ Canepari (1992), pp. 58, 88–89.

- ^ Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), p. 134.

- ^ Canepari (1992), pp. 57–59, 88–89.

- ^ a b Bertinetto & Loporcaro (2005), pp. 134–135.

- ^ Canepari (1992), p. 59.

- ^ Canepari (1992), p. 58.

- ^ Recasens (2013), p. 13.

- ^ «(…) in a large number of Italian accents, there is considerable friction involved in the pronunciation of [ʎ], creating a voiced palatal lateral fricative (for which there is no established IPA symbol)» Ashby (2011:64).

- ^ a b Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996), p. 221.

- ^ Rogers & d’Arcangeli (2004), p. 118.

- ^ a b Luciano Canepari, A Handbook of Pronunciation, chapter 3: «Italian».

- ^ Romano, Antonio. «A preliminary contribution to the study of phonetic variation of /r/ in Italian and Italo-Romance.» Rhotics. New data and perspectives (Proc. of’r-atics-3, Libera Università di Bolzano (2011): 209–226, pp. 213–214.

- ^ «Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia».

- ^ «Dizionario d’ortografia e di pronunzia».

- ^ a b Clivio, Gianrenzo; Danesi, Marcel (2000). The Sounds, Forms, and Uses of Italian: An Introduction to Italian Linguistics. University of Toronto Press. pp. 21, 66.

- ^ Canepari, Luciano (January 1999). Il MªPI – Manuale di pronuncia italiana (second ed.). Bologna: Zanichelli. ISBN 978-88-08-24624-0.

- ^ Simone 2010.

- ^ a b c «Collins Italian Dictionary | Translations, Definitions and Pronunciations». www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Danesi, Marcel (2008). Practice Makes Perfect: Complete Italian Grammar, Premium Second Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-259-58772-6.

- ^ Kellogg, Michael. «Dizionario italiano-inglese WordReference». WordReference.com (in Italian and English). WordReference.com. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ashby, Patricia (2011), Understanding Phonetics, Understanding Language series, Routledge, ISBN 978-0340928271

- Bertinetto, Pier Marco; Loporcaro, Michele (2005). «The sound pattern of Standard Italian, as compared with the varieties spoken in Florence, Milan and Rome» (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 131–151. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002148. S2CID 6479830.

- Canepari, Luciano (1992), Il MªPi – Manuale di pronuncia italiana [Handbook of Italian Pronunciation] (in Italian), Bologna: Zanichelli, ISBN 978-88-08-24624-0

- Berloco, Fabrizio (2018). The Big Book of Italian Verbs: 900 Fully Conjugated Verbs in All Tenses. With IPA Transcription, 2nd Edition. Lengu. ISBN 978-8894034813.

- Palermo, Massimo (2015). Linguistica italiana. Il Mulino. ISBN 978-8815258847.

- Simone, Raffaele (2010). Enciclopedia dell’italiano. Treccani.

- Hall, Robert A. Jr. (1944). «Italian phonemes and orthography». Italica. American Association of Teachers of Italian. 21 (2): 72–82. doi:10.2307/475860. JSTOR 475860.

- Rogers, Derek; d’Arcangeli, Luciana (2004). «Italian». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 34 (1): 117–121. doi:10.1017/S0025100304001628.

- M. Vitale, Studi di Storia della Lingua Italiana, LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 1992, ISBN 88-7916-015-X

- S. Morgana, Capitoli di Storia Linguistica Italiana, LED Edizioni Universitarie, Milano, 2003, ISBN 88-7916-211-X

- J. Kinder, CLIC: Cultura e Lingua d’Italia in CD-ROM / Culture and Language of Italy on CD-ROM, Interlinea, Novara, 2008, ISBN 978-88-8212-637-7

- Treccani Italian Dictionary (iso). archive.org (in Italian). it. (with a similar list of other Italian-modern languages dictionaries)

External links[edit]

- Salvatore Battaglia (1961–2002). «Grande dizionario della lingua italiana. Prototipo edizione digitale». UTET.