| Rumpelstiltskin | |

|---|---|

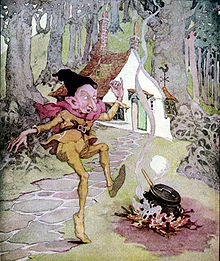

Illustration from Andrew Lang’s The Blue Fairy Book (1889) |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Rumpelstiltskin |

| Also known as |

|

| Country |

|

| Published in |

|

«Rumpelstiltskin» ( RUMP-əl-STILT-skin;[1] German: Rumpelstilzchen) is a German fairy tale.[2] It was collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Children’s and Household Tales.[2] The story is about a little imp who spins straw into gold in exchange for a girl’s firstborn child.[2]

Plot[edit]

In order to appear superior, a miller brags to the king and people of the kingdom he lives in by claiming his daughter can spin straw into gold.[note 1] The king calls for the girl, locks her up in a tower room filled with straw and a spinning wheel, and demands she spin the straw into gold by morning or he will have her killed.[note 2] When she has given up all hope, a little imp-like man appears in the room and spins the straw into gold in return for her necklace. The next morning the king takes the girl to a larger room filled with straw to repeat the feat, the imp once again spins, in return for the girl’s ring. On the third day, when the girl has been taken to an even larger room filled with straw and told by the king that he will marry her if she can fill this room with gold or execute her if she cannot, the girl has nothing left with which she can pay the strange creature. He extracts a promise from her that she will give him her firstborn child, and so he spins the straw into gold a final time.[note 3]

Illustration by Anne Anderson from Grimm’s Fairy Tales (London and Glasgow 1922)

The king keeps his promise to marry the miller’s daughter. But when their first child is born, the imp returns to claim his payment. She offers him all the wealth she has to keep the child, but the imp has no interest in her riches. He finally agrees to give up his claim to the child if she can guess the imp’s name within three days.[note 4]

The queen’s many guesses fail. But before the final night, she wanders into the woods[note 5] searching for him and comes across his remote mountain cottage and watches, unseen, as he hops about his fire and sings. In his song’s lyrics—»tonight tonight, my plans I make, tomorrow tomorrow, the baby I take. The queen will never win the game, for Rumpelstiltskin is my name»—he reveals his name.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day, after first feigning ignorance, she reveals his name, Rumpelstiltskin, and he loses his temper at the loss of their bargain. Versions vary about whether he accuses the devil or witches of having revealed his name to the queen. In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then «ran away angrily, and never came back.» The ending was revised in an 1857 edition to a more gruesome ending wherein Rumpelstiltskin «in his rage drove his right foot so far into the ground that it sank in up to his waist; then in a passion he seized the left foot with both hands and tore himself in two.» Other versions have Rumpelstiltskin driving his right foot so far into the ground that he creates a chasm and falls into it, never to be seen again. In the oral version originally collected by the Brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle.

- Notes

- ^ Some versions make the miller’s daughter blonde and describe the «straw-into-gold» claim as a careless boast the miller makes about the way his daughter’s straw-like blond hair takes on a gold-like lustre when sunshine strikes it.

- ^ Other versions have the king threatening to lock her up in a dungeon forever, or to punish her father for lying.

- ^ In some versions, the imp appears and begins to turn the straw into gold, paying no heed to the girl’s protests that she has nothing to pay him with; when he finishes the task, he states that the price is her first child, and the horrified girl objects because she never agreed to this arrangement.

- ^ Some versions have the imp limiting the number of daily guesses to three and hence the total number of guesses allowed to a maximum of nine.

- ^ In some versions, she sends a servant into the woods instead of going herself, in order to keep the king’s suspicions at bay.

History[edit]

According to researchers at Durham University and the NOVA University Lisbon, the origins of the story can be traced back to around 4,000 years ago.[undue weight? – discuss][3][4] A possible early literary reference to the tale appears in Dio of Halicarnassus’ Roman Antiquities, in the 1st century CE.[5]

Variants[edit]

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Tom Tit Tot[6] in United Kingdom (from English Fairy Tales, 1890, by Joseph Jacobs); The Lazy Beauty and her Aunts in Ireland (from The Fireside Stories of Ireland, 1870 by Patrick Kennedy); Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers’s Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 1826); Gilitrutt in Iceland;[7][8] جعيدان (Joaidane «He who talks too much») in Arabic; Хламушка (Khlamushka «Junker») in Russia; Rumplcimprcampr, Rampelník or Martin Zvonek in the Czech Republic; Martinko Klingáč in Slovakia; «Cvilidreta» in Croatia; Ruidoquedito («Little noise») in South America; Pancimanci in Hungary (from 1862 folktale collection by László Arany[9]); Daiku to Oniroku (大工と鬼六 «The carpenter and the ogre») in Japan and Myrmidon in France.

An earlier literary variant in French was penned by Mme. L’Héritier, titled Ricdin-Ricdon.[10] A version of it exists in the compilation Le Cabinet des Fées, Vol. XII. pp. 125-131.

The Cornish tale of Duffy and the Devil plays out an essentially similar plot featuring a «devil» named Terry-top.[11]

All these tales are classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 500, «The Name of the Supernatural Helper».[12][13] According to scholarship, it is popular in «Denmark, Finland, Germany and Ireland».[14]

Name[edit]

Illustration by Walter Crane from Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm (1886)

The name Rumpelstilzchen in German (IPA: /ʀʊmpl̩ʃtiːlt͡sçn̩/) means literally «little rattle stilt», a stilt being a post or pole that provides support for a structure. A rumpelstilt or rumpelstilz was consequently the name of a type of goblin, also called a pophart or poppart, that makes noises by rattling posts and rapping on planks. The meaning is similar to rumpelgeist («rattle ghost») or poltergeist, a mischievous spirit that clatters and moves household objects. (Other related concepts are mummarts or boggarts and hobs, which are mischievous household spirits that disguise themselves.) The ending -chen is a German diminutive cognate to English -kin.

The name is believed to be derived from Johann Fischart’s Geschichtklitterung, or Gargantua of 1577 (a loose adaptation of Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel), which refers to an «amusement» for children, a children’s game named «Rumpele stilt oder der Poppart».[15][unreliable source]

Translations[edit]

Illustration for the tale of «Rumpel-stilt-skin» from The heart of oak books (Boston 1910)

Translations of the original Grimm fairy tale (KHM 55) into various languages have generally substituted different names for the dwarf whose name is Rumpelstilzchen. For some languages, a name was chosen that comes close in sound to the German name: Rumpelstiltskin or Rumplestiltskin in English, Repelsteeltje in Dutch, Rumpelstichen in Brazilian Portuguese, Rumpelstinski, Rumpelestíjeles, Trasgolisto, Jasil el Trasgu, Barabay, Rompelimbrá, Barrabás, Ruidoquedito, Rompeltisquillo, Tiribilitín, Tremolín, El enano saltarín y el duende saltarín in Spanish, Rumplcimprcampr or Rampelník in Czech. In Japanese, it is called ルンペルシュティルツキン (Runperushutirutsukin). Russian might have the most accomplished imitation of the German name with Румпельшти́льцхен (Rumpelʹshtílʹtskhen).

In other languages, the name was translated in a poetic and approximate way. Thus Rumpelstilzchen is known as Päronskaft (literally «Pear-stalk») in Swedish,[16] where the sense of stilt or stalk of the second part is retained.

Slovak translations use Martinko Klingáč. Polish translations use Titelitury (or Rumpelsztyk) and Finnish ones Tittelintuure, Rompanruoja or Hopskukkeli. The Hungarian name is Tűzmanócska and in Serbo-Croatian Cvilidreta («Whine-screamer»). The Slovenian translation uses «Špicparkeljc» (pointy-hoof). For Hebrew the poet Avraham Shlonsky composed the name עוץ לי גוץ לי (Ootz-li Gootz-li, a compact and rhymy touch to the original sentence and meaning of the story, «My adviser my midget»), when using the fairy tale as the basis of a children’s musical, now a classic among Hebrew children’s plays. Greek translations have used Ρουμπελστίλτσκιν (from the English) or Κουτσοκαλιγέρης (Koutsokaliyéris), which could figure as a Greek surname, formed with the particle κούτσο- (koútso- «limping»), and is perhaps derived from the Hebrew name. In Italian, the creature is usually called Tremotino, which is probably formed from the world tremoto, which means «earthquake» in Tuscan dialect, and the suffix «-ino», which generally indicates a small and/or sly character. The first Italian edition of the fables was published in 1897, and the books in those years were all written in Tuscan. Urdu versions of the tale used the name Tees Mar Khan for the imp.

Rumpelstiltskin principle[edit]

The value and power of using personal names and titles is well established in psychology, management, teaching and trial law. It is often referred to as the «Rumpelstiltskin principle». It derives from a very ancient belief that to give or know the true name of a being is to have power over it, for which compare Adam’s naming of the animals in Genesis 2:19-20.

- Brodsky, Stanley (2013). «The Rumpelstiltskin Principle». APA.org. American Psychological Association.

- Winston, Patrick (2009-08-16). «The Rumpelstiltskin Principle». MIT.edu.

- van der Geest, Sjak (2010). «Rumpelstiltskin: The magic of the right word». In Oderwald, Arko; van Tilburg, Willem; Neuvel, Koos (eds.). Unfamiliar knowledge: Psychiatric disorders in literature. academia.edu. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom.

Media and popular culture[edit]

Film adaptations[edit]

- Rumpelstiltskin (1915 film), an American silent film, directed by Raymond B. West

- Rumpelstiltskin (1940 film), a German fantasy film, directed by Alf Zengerling

- Rumpelstiltskin (1955 film), a German fantasy film, directed by Herbert B. Fredersdorf

- Rumpelstiltskin (1985 film), a twenty-four-minute animated feature

- Rumpelstiltskin (1987 film), an American-Israeli film

- Rumpelstiltskin (1995 film), an American horror film, loosely based on the Grimm fairy tale

- Rumpelstilzchen (2009 film), a German TV adaptation starring Gottfried John and Julie Engelbrecht

Ensemble media[edit]

- «Rumpelstiltskin», a 1995 episode from Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears as a figment of Chief O’Brien’s imagination in the 16th episode If Wishes Were Horses of season 1 in the Star Trek series Deep Space Nine.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears as a villainous character in the Shrek franchise, first voiced by Conrad Vernon in a minor role in Shrek the Third. In Shrek Forever After, the character’s appearance and persona are significantly altered to become the main villain of the film, now voiced by Walt Dohrn. A diminutive, evil con man who deals in magical contracts, this version of the character has a personal vendetta against the ogre Shrek, as his plot to take over Far Far Away was foiled by Shrek’s rescue of Princess Fiona in the first film. Rumpel manipulates Shrek into signing a deal that creates an alternate reality where Fiona was never rescued and Rumpel ascended to power with the help of an army of witches, a giant goose named Fifi, and the Pied Piper. Dohrn’s version of the character also appears in various spin-offs.

- In Once Upon a Time, Rumplestiltskin is one of the integral characters, portrayed by Robert Carlyle. In the Enchanted Forest, Rumplestiltskin was a cowardly peasant who ascended to power by killing the «Dark One» and gaining his dark magic to protect his son Baelfire. However, the darkness causes him to grow increasingly twisted and violent. While attempting to eliminate his father’s curse, Baelfire is lost to a land without magic. Ultimately aiming to save his son, Rumplestiltskin orchestrates a complex series of events, establishing himself as a dark sorcerer who strikes magical deals with various individuals in the fairy tale world, and manipulating the Evil Queen into cursing the land by transporting everyone to the Land Without Magic, while implementing failsafes to break the Dark Curse and maintain his powers. Throughout the series, he wrestles with the conflict between his dark nature and the call to use his power for good.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears in Ever After High as an infamous professor known for making students spin straw into gold as a form of extra credit and detention. He purposely gives his students bad grades in such a way they are forced to ask for extra credit.

Theater[edit]

- Utz-li-Gutz-li, a 1965 Israeli stage musical written by Avraham Shlonsky

- Rumpelstiltskin, a 2011 American stage musical

See also[edit]

- True name

References[edit]

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c «Rumpelstiltskin». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ BBC (2016-01-20). «Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say». BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ da Silva, Sara Graça; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (January 2016). «Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales». Royal Society Open Science. 3 (1): 150645. Bibcode:2016RSOS….350645D. doi:10.1098/rsos.150645. PMC 4736946. PMID 26909191.

- ^ Anderson, Graham (2000). Fairytale in the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 9780415237031.

- ^ ««The Story of Tom Tit Tot» | Stories from Around the World | Traditional | Lit2Go ETC». etc.usf.edu.

- ^ Grímsson, Magnús; Árnason, Jon. Íslensk ævintýri. Reykjavik: 1852. pp. 123-126. [1]

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline (2004). Icelandic folktales & legends (2nd ed.). Stroud: Tempus. pp. 86–89. ISBN 0752430459.

- ^ László Arany: Eredeti népmesék (folktale collection, Pest, 1862, in Hungarian)

- ^ Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier: La Tour ténébreuse et les Jours lumineux: Contes Anglois, 1705. In French

- ^ Hunt, Robert (1871). Popular Romances of the West of England; or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall. London: John Camden Hotten. pp. 239–247.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Animal tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 285 — 286.

- ^ «Name of the Helper». D. L. Ashliman. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ Christiansen, Reidar Thorwalf. Folktales of Norway. Chicago: University of Chicago press by 1994

. pp. 5-6.

- ^ Wiktionary article on Rumpelstilzchen.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Wilhelm (2008). Bröderna Grimms sagovärld (in Swedish). Bonnier Carlsen. p. 72. ISBN 978-91-638-2435-7.

Selected bibliography[edit]

- Bergler, Edmund (1961). «The Clinical Importance of «Rumpelstiltskin» As Anti-Male Manifesto». American Imago. 18 (1): 65–70. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26301733.

- Marshall, Howard W. (1973). «‘Tom Tit Tot’. A Comparative Essay on Aarne-Thompson Type 500. The Name of the Helper». Folklore. 84 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1973.9716495. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1260436.

- Ní Dhuibhne, Éilis (2012). «The Name of the Helper: «Kinder- und Hausmärchen» and Ireland». Béaloideas. 80: 1–22. ISSN 0332-270X. JSTOR 24862867.

- Rand, Harry (2000). «Who was Rupelstiltskin?». The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 81 (5): 943–962. doi:10.1516/0020757001600309. PMID 11109578.

- von Sydow, Carl W. (1909). Två spinnsagor: en studie i jämförande folksagoforskning (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt. [Analysis of Aarne-Thompson-Uther tale types 500 and 501]

- Yolen, Jane (1993). «Foreword: The Rumpelstiltskin Factor». Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 5 (2 (18)): 11–13. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 43308148.

- Zipes, Jack (1993). «Spinning with Fate: Rumpelstiltskin and the Decline of Female Productivity». Western Folklore. 52 (1): 43–60. doi:10.2307/1499492. ISSN 0043-373X. JSTOR 1499492.

- T., A. W.; Clodd, Edward (1889). «The Philosophy of Rumpelstilt-Skin». The Folk-Lore Journal. 7 (2): 135–163. ISSN 1744-2524. JSTOR 1252656.

Further reading[edit]

- Cambon, Fernand (1976). «La fileuse. Remarques psychanalytiques sur le motif de la «fileuse» et du «filage» dans quelques poèmes et contes allemands». Littérature. 23 (3): 56–74. doi:10.3406/litt.1976.1122.

- Dvořák, Karel. (1967). «AaTh 500 in deutschen Varianten aus der Tschechoslowakei». In: Fabula. 9: 100-104. 10.1515/fabl.1967.9.1-3.100.

- Paulme, Denise. «Thème et variations: l’épreuve du «nom inconnu» dans les contes d’Afrique noire». In: Cahiers d’études africaines, vol. 11, n°42, 1971. pp. 189-205. DOI: Thème et variations : l’épreuve du « nom inconnu » dans les contes d’Afrique noire.; www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1971_num_11_42_2800

External links[edit]

| Rumpelstiltskin | |

|---|---|

Illustration from Andrew Lang’s The Blue Fairy Book (1889) |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Rumpelstiltskin |

| Also known as |

|

| Country |

|

| Published in |

|

«Rumpelstiltskin» ( RUMP-əl-STILT-skin;[1] German: Rumpelstilzchen) is a German fairy tale.[2] It was collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Children’s and Household Tales.[2] The story is about a little imp who spins straw into gold in exchange for a girl’s firstborn child.[2]

Plot[edit]

In order to appear superior, a miller brags to the king and people of the kingdom he lives in by claiming his daughter can spin straw into gold.[note 1] The king calls for the girl, locks her up in a tower room filled with straw and a spinning wheel, and demands she spin the straw into gold by morning or he will have her killed.[note 2] When she has given up all hope, a little imp-like man appears in the room and spins the straw into gold in return for her necklace. The next morning the king takes the girl to a larger room filled with straw to repeat the feat, the imp once again spins, in return for the girl’s ring. On the third day, when the girl has been taken to an even larger room filled with straw and told by the king that he will marry her if she can fill this room with gold or execute her if she cannot, the girl has nothing left with which she can pay the strange creature. He extracts a promise from her that she will give him her firstborn child, and so he spins the straw into gold a final time.[note 3]

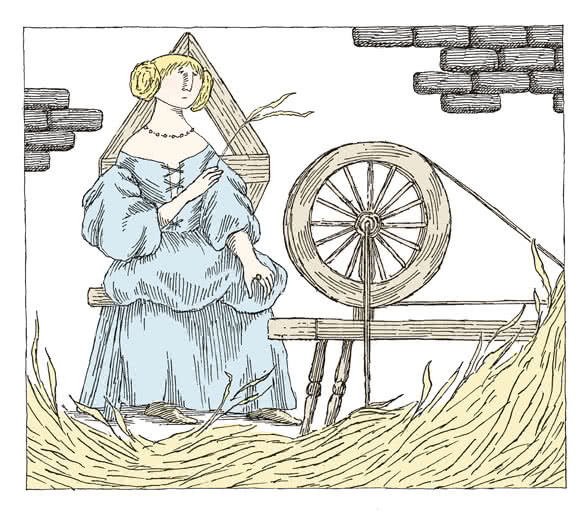

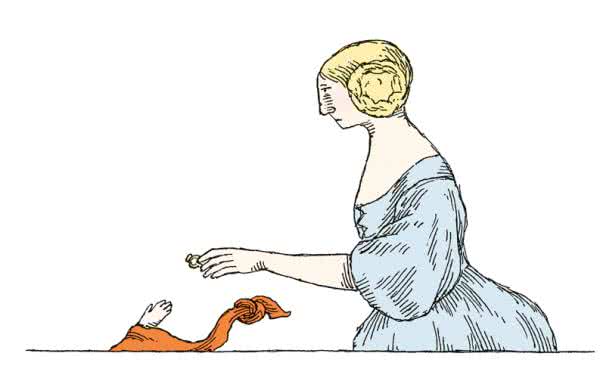

Illustration by Anne Anderson from Grimm’s Fairy Tales (London and Glasgow 1922)

The king keeps his promise to marry the miller’s daughter. But when their first child is born, the imp returns to claim his payment. She offers him all the wealth she has to keep the child, but the imp has no interest in her riches. He finally agrees to give up his claim to the child if she can guess the imp’s name within three days.[note 4]

The queen’s many guesses fail. But before the final night, she wanders into the woods[note 5] searching for him and comes across his remote mountain cottage and watches, unseen, as he hops about his fire and sings. In his song’s lyrics—»tonight tonight, my plans I make, tomorrow tomorrow, the baby I take. The queen will never win the game, for Rumpelstiltskin is my name»—he reveals his name.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day, after first feigning ignorance, she reveals his name, Rumpelstiltskin, and he loses his temper at the loss of their bargain. Versions vary about whether he accuses the devil or witches of having revealed his name to the queen. In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then «ran away angrily, and never came back.» The ending was revised in an 1857 edition to a more gruesome ending wherein Rumpelstiltskin «in his rage drove his right foot so far into the ground that it sank in up to his waist; then in a passion he seized the left foot with both hands and tore himself in two.» Other versions have Rumpelstiltskin driving his right foot so far into the ground that he creates a chasm and falls into it, never to be seen again. In the oral version originally collected by the Brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle.

- Notes

- ^ Some versions make the miller’s daughter blonde and describe the «straw-into-gold» claim as a careless boast the miller makes about the way his daughter’s straw-like blond hair takes on a gold-like lustre when sunshine strikes it.

- ^ Other versions have the king threatening to lock her up in a dungeon forever, or to punish her father for lying.

- ^ In some versions, the imp appears and begins to turn the straw into gold, paying no heed to the girl’s protests that she has nothing to pay him with; when he finishes the task, he states that the price is her first child, and the horrified girl objects because she never agreed to this arrangement.

- ^ Some versions have the imp limiting the number of daily guesses to three and hence the total number of guesses allowed to a maximum of nine.

- ^ In some versions, she sends a servant into the woods instead of going herself, in order to keep the king’s suspicions at bay.

History[edit]

According to researchers at Durham University and the NOVA University Lisbon, the origins of the story can be traced back to around 4,000 years ago.[undue weight? – discuss][3][4] A possible early literary reference to the tale appears in Dio of Halicarnassus’ Roman Antiquities, in the 1st century CE.[5]

Variants[edit]

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Tom Tit Tot[6] in United Kingdom (from English Fairy Tales, 1890, by Joseph Jacobs); The Lazy Beauty and her Aunts in Ireland (from The Fireside Stories of Ireland, 1870 by Patrick Kennedy); Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers’s Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 1826); Gilitrutt in Iceland;[7][8] جعيدان (Joaidane «He who talks too much») in Arabic; Хламушка (Khlamushka «Junker») in Russia; Rumplcimprcampr, Rampelník or Martin Zvonek in the Czech Republic; Martinko Klingáč in Slovakia; «Cvilidreta» in Croatia; Ruidoquedito («Little noise») in South America; Pancimanci in Hungary (from 1862 folktale collection by László Arany[9]); Daiku to Oniroku (大工と鬼六 «The carpenter and the ogre») in Japan and Myrmidon in France.

An earlier literary variant in French was penned by Mme. L’Héritier, titled Ricdin-Ricdon.[10] A version of it exists in the compilation Le Cabinet des Fées, Vol. XII. pp. 125-131.

The Cornish tale of Duffy and the Devil plays out an essentially similar plot featuring a «devil» named Terry-top.[11]

All these tales are classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as tale type ATU 500, «The Name of the Supernatural Helper».[12][13] According to scholarship, it is popular in «Denmark, Finland, Germany and Ireland».[14]

Name[edit]

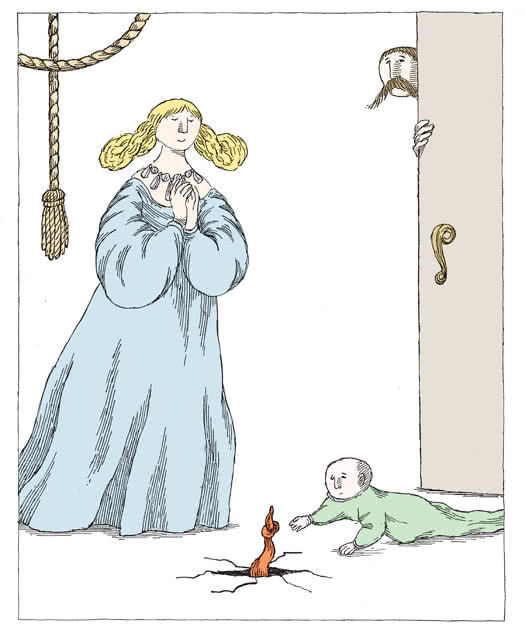

Illustration by Walter Crane from Household Stories by the Brothers Grimm (1886)

The name Rumpelstilzchen in German (IPA: /ʀʊmpl̩ʃtiːlt͡sçn̩/) means literally «little rattle stilt», a stilt being a post or pole that provides support for a structure. A rumpelstilt or rumpelstilz was consequently the name of a type of goblin, also called a pophart or poppart, that makes noises by rattling posts and rapping on planks. The meaning is similar to rumpelgeist («rattle ghost») or poltergeist, a mischievous spirit that clatters and moves household objects. (Other related concepts are mummarts or boggarts and hobs, which are mischievous household spirits that disguise themselves.) The ending -chen is a German diminutive cognate to English -kin.

The name is believed to be derived from Johann Fischart’s Geschichtklitterung, or Gargantua of 1577 (a loose adaptation of Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel), which refers to an «amusement» for children, a children’s game named «Rumpele stilt oder der Poppart».[15][unreliable source]

Translations[edit]

Illustration for the tale of «Rumpel-stilt-skin» from The heart of oak books (Boston 1910)

Translations of the original Grimm fairy tale (KHM 55) into various languages have generally substituted different names for the dwarf whose name is Rumpelstilzchen. For some languages, a name was chosen that comes close in sound to the German name: Rumpelstiltskin or Rumplestiltskin in English, Repelsteeltje in Dutch, Rumpelstichen in Brazilian Portuguese, Rumpelstinski, Rumpelestíjeles, Trasgolisto, Jasil el Trasgu, Barabay, Rompelimbrá, Barrabás, Ruidoquedito, Rompeltisquillo, Tiribilitín, Tremolín, El enano saltarín y el duende saltarín in Spanish, Rumplcimprcampr or Rampelník in Czech. In Japanese, it is called ルンペルシュティルツキン (Runperushutirutsukin). Russian might have the most accomplished imitation of the German name with Румпельшти́льцхен (Rumpelʹshtílʹtskhen).

In other languages, the name was translated in a poetic and approximate way. Thus Rumpelstilzchen is known as Päronskaft (literally «Pear-stalk») in Swedish,[16] where the sense of stilt or stalk of the second part is retained.

Slovak translations use Martinko Klingáč. Polish translations use Titelitury (or Rumpelsztyk) and Finnish ones Tittelintuure, Rompanruoja or Hopskukkeli. The Hungarian name is Tűzmanócska and in Serbo-Croatian Cvilidreta («Whine-screamer»). The Slovenian translation uses «Špicparkeljc» (pointy-hoof). For Hebrew the poet Avraham Shlonsky composed the name עוץ לי גוץ לי (Ootz-li Gootz-li, a compact and rhymy touch to the original sentence and meaning of the story, «My adviser my midget»), when using the fairy tale as the basis of a children’s musical, now a classic among Hebrew children’s plays. Greek translations have used Ρουμπελστίλτσκιν (from the English) or Κουτσοκαλιγέρης (Koutsokaliyéris), which could figure as a Greek surname, formed with the particle κούτσο- (koútso- «limping»), and is perhaps derived from the Hebrew name. In Italian, the creature is usually called Tremotino, which is probably formed from the world tremoto, which means «earthquake» in Tuscan dialect, and the suffix «-ino», which generally indicates a small and/or sly character. The first Italian edition of the fables was published in 1897, and the books in those years were all written in Tuscan. Urdu versions of the tale used the name Tees Mar Khan for the imp.

Rumpelstiltskin principle[edit]

The value and power of using personal names and titles is well established in psychology, management, teaching and trial law. It is often referred to as the «Rumpelstiltskin principle». It derives from a very ancient belief that to give or know the true name of a being is to have power over it, for which compare Adam’s naming of the animals in Genesis 2:19-20.

- Brodsky, Stanley (2013). «The Rumpelstiltskin Principle». APA.org. American Psychological Association.

- Winston, Patrick (2009-08-16). «The Rumpelstiltskin Principle». MIT.edu.

- van der Geest, Sjak (2010). «Rumpelstiltskin: The magic of the right word». In Oderwald, Arko; van Tilburg, Willem; Neuvel, Koos (eds.). Unfamiliar knowledge: Psychiatric disorders in literature. academia.edu. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom.

Media and popular culture[edit]

Film adaptations[edit]

- Rumpelstiltskin (1915 film), an American silent film, directed by Raymond B. West

- Rumpelstiltskin (1940 film), a German fantasy film, directed by Alf Zengerling

- Rumpelstiltskin (1955 film), a German fantasy film, directed by Herbert B. Fredersdorf

- Rumpelstiltskin (1985 film), a twenty-four-minute animated feature

- Rumpelstiltskin (1987 film), an American-Israeli film

- Rumpelstiltskin (1995 film), an American horror film, loosely based on the Grimm fairy tale

- Rumpelstilzchen (2009 film), a German TV adaptation starring Gottfried John and Julie Engelbrecht

Ensemble media[edit]

- «Rumpelstiltskin», a 1995 episode from Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears as a figment of Chief O’Brien’s imagination in the 16th episode If Wishes Were Horses of season 1 in the Star Trek series Deep Space Nine.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears as a villainous character in the Shrek franchise, first voiced by Conrad Vernon in a minor role in Shrek the Third. In Shrek Forever After, the character’s appearance and persona are significantly altered to become the main villain of the film, now voiced by Walt Dohrn. A diminutive, evil con man who deals in magical contracts, this version of the character has a personal vendetta against the ogre Shrek, as his plot to take over Far Far Away was foiled by Shrek’s rescue of Princess Fiona in the first film. Rumpel manipulates Shrek into signing a deal that creates an alternate reality where Fiona was never rescued and Rumpel ascended to power with the help of an army of witches, a giant goose named Fifi, and the Pied Piper. Dohrn’s version of the character also appears in various spin-offs.

- In Once Upon a Time, Rumplestiltskin is one of the integral characters, portrayed by Robert Carlyle. In the Enchanted Forest, Rumplestiltskin was a cowardly peasant who ascended to power by killing the «Dark One» and gaining his dark magic to protect his son Baelfire. However, the darkness causes him to grow increasingly twisted and violent. While attempting to eliminate his father’s curse, Baelfire is lost to a land without magic. Ultimately aiming to save his son, Rumplestiltskin orchestrates a complex series of events, establishing himself as a dark sorcerer who strikes magical deals with various individuals in the fairy tale world, and manipulating the Evil Queen into cursing the land by transporting everyone to the Land Without Magic, while implementing failsafes to break the Dark Curse and maintain his powers. Throughout the series, he wrestles with the conflict between his dark nature and the call to use his power for good.

- Rumpelstiltskin appears in Ever After High as an infamous professor known for making students spin straw into gold as a form of extra credit and detention. He purposely gives his students bad grades in such a way they are forced to ask for extra credit.

Theater[edit]

- Utz-li-Gutz-li, a 1965 Israeli stage musical written by Avraham Shlonsky

- Rumpelstiltskin, a 2011 American stage musical

See also[edit]

- True name

References[edit]

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b c «Rumpelstiltskin». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ BBC (2016-01-20). «Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say». BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ da Silva, Sara Graça; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (January 2016). «Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales». Royal Society Open Science. 3 (1): 150645. Bibcode:2016RSOS….350645D. doi:10.1098/rsos.150645. PMC 4736946. PMID 26909191.

- ^ Anderson, Graham (2000). Fairytale in the Ancient World. Routledge. ISBN 9780415237031.

- ^ ««The Story of Tom Tit Tot» | Stories from Around the World | Traditional | Lit2Go ETC». etc.usf.edu.

- ^ Grímsson, Magnús; Árnason, Jon. Íslensk ævintýri. Reykjavik: 1852. pp. 123-126. [1]

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline (2004). Icelandic folktales & legends (2nd ed.). Stroud: Tempus. pp. 86–89. ISBN 0752430459.

- ^ László Arany: Eredeti népmesék (folktale collection, Pest, 1862, in Hungarian)

- ^ Marie-Jeanne L’Héritier: La Tour ténébreuse et les Jours lumineux: Contes Anglois, 1705. In French

- ^ Hunt, Robert (1871). Popular Romances of the West of England; or, The Drolls, Traditions, and Superstitions of Old Cornwall. London: John Camden Hotten. pp. 239–247.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg (2004). The Types of International Folktales: Animal tales, tales of magic, religious tales, and realistic tales, with an introduction. FF Communications. p. 285 — 286.

- ^ «Name of the Helper». D. L. Ashliman. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ Christiansen, Reidar Thorwalf. Folktales of Norway. Chicago: University of Chicago press by 1994

. pp. 5-6.

- ^ Wiktionary article on Rumpelstilzchen.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Wilhelm (2008). Bröderna Grimms sagovärld (in Swedish). Bonnier Carlsen. p. 72. ISBN 978-91-638-2435-7.

Selected bibliography[edit]

- Bergler, Edmund (1961). «The Clinical Importance of «Rumpelstiltskin» As Anti-Male Manifesto». American Imago. 18 (1): 65–70. ISSN 0065-860X. JSTOR 26301733.

- Marshall, Howard W. (1973). «‘Tom Tit Tot’. A Comparative Essay on Aarne-Thompson Type 500. The Name of the Helper». Folklore. 84 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1973.9716495. ISSN 0015-587X. JSTOR 1260436.

- Ní Dhuibhne, Éilis (2012). «The Name of the Helper: «Kinder- und Hausmärchen» and Ireland». Béaloideas. 80: 1–22. ISSN 0332-270X. JSTOR 24862867.

- Rand, Harry (2000). «Who was Rupelstiltskin?». The International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 81 (5): 943–962. doi:10.1516/0020757001600309. PMID 11109578.

- von Sydow, Carl W. (1909). Två spinnsagor: en studie i jämförande folksagoforskning (in Swedish). Stockholm: P.A. Norstedt. [Analysis of Aarne-Thompson-Uther tale types 500 and 501]

- Yolen, Jane (1993). «Foreword: The Rumpelstiltskin Factor». Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 5 (2 (18)): 11–13. ISSN 0897-0521. JSTOR 43308148.

- Zipes, Jack (1993). «Spinning with Fate: Rumpelstiltskin and the Decline of Female Productivity». Western Folklore. 52 (1): 43–60. doi:10.2307/1499492. ISSN 0043-373X. JSTOR 1499492.

- T., A. W.; Clodd, Edward (1889). «The Philosophy of Rumpelstilt-Skin». The Folk-Lore Journal. 7 (2): 135–163. ISSN 1744-2524. JSTOR 1252656.

Further reading[edit]

- Cambon, Fernand (1976). «La fileuse. Remarques psychanalytiques sur le motif de la «fileuse» et du «filage» dans quelques poèmes et contes allemands». Littérature. 23 (3): 56–74. doi:10.3406/litt.1976.1122.

- Dvořák, Karel. (1967). «AaTh 500 in deutschen Varianten aus der Tschechoslowakei». In: Fabula. 9: 100-104. 10.1515/fabl.1967.9.1-3.100.

- Paulme, Denise. «Thème et variations: l’épreuve du «nom inconnu» dans les contes d’Afrique noire». In: Cahiers d’études africaines, vol. 11, n°42, 1971. pp. 189-205. DOI: Thème et variations : l’épreuve du « nom inconnu » dans les contes d’Afrique noire.; www.persee.fr/doc/cea_0008-0055_1971_num_11_42_2800

External links[edit]

Время чтения: 7 мин.

Много-много лет назад жил да был мельник, бедный-пребедный, а дочь у него была красавица. Случилось как-то однажды, что пришлось ему говорить с королем, и вот он, чтобы придать себе побольше весу, сказал ему: «Есть у меня дочка, такая-то искусница, что вот и солому тебе в золото перепрясть сумеет». Король сказал мельнику: «Это искусство недурное, и если твоя дочь точно уж такая искусница, как ты говоришь, то приведи ее завтра ко мне в замок, я ее испытаю».

Когда мельник привел свою дочь, король отвел ее в особую каморку, битком набитую соломой, дал ей самопрялку и мотовило и сказал: «Садись-ка за работу; если ты в течение этой ночи до завтрашнего раннего утра не перепрядешь всю эту солому в золото, то велю тебя казнить».

Затем он своими руками запер каморку, и она осталась там одна.

Так и сидела там бедняжка Мельникова дочь и придумать не могла, как ей спастись от лютой смерти. Она и понятия не имела о том, как солому перепрясть в золотые нити, и так пугалась ожидавшей ее участи, что наконец залилась слезами.

Вдруг дверь приотворилась, и к ней в каморку вошел маленький человечек и сказал: «Добрый вечер, Мельникова дочка, о чем ты так плачешь?» — «Ах, ты не знаешь моего горя! — отвечала ему девушка. — Вот всю эту солому я должна перепрясть в золотые нити, а я этого совсем не умею!»

Человечек сказал: «А ты что же мне дашь, если я тебе все это перепряду?» — «Ленточку у меня на шее», — отвечала девушка. Тот взял у нее ленточку, присел за самопрялку да — шур, шур, шур! — три раза обернет, и шпулька намотана золота. Он вставил другую, опять — шур, шур, шур! — три раза обернет, и вторая готова. И так продолжалась работа до самого утра, и вся солома была перепрядена, и все шпульки намотаны золотом.

При восходе солнца пришел король, и когда увидел столько золота, то и удивился, и обрадовался; но сердце его еще сильнее прежнего жаждало золота и золота. Он велел перевести Мельникову дочку в другой покойник, значительно побольше этого, тоже наполненный соломою, и приказал ей всю эту солому также перепрясть в одну ночь, если ей жизнь дорога.

Девушка не знала, как ей быть, и стала плакать, и вновь открылась дверь, явился тот же маленький человечек и сказал: «А что ты мне дашь, если я и эту солому возьмусь тебе перепрясть в золото?» — «С пальчика колечко», — отвечала девушка. Человечек взял колечко, стал опять поскрипывать колесиком самопрялки и к утру успел перепрясть всю солому в блестящее золото.

Король, увидев это, чрезвычайно обрадовался, но ему все еще не довольно было золота; он велел переместить Мельникову дочку в третий покой, еще больше двух первых, битком набитый соломой, и сказал: «И эту ты должна также перепрясть в одну ночь, и если это тебе удастся, я возьму тебя в, супруги себе». А сам про себя подумал: «Хоть она и Мельникова дочь, а все же я и в целом свете не найду себе жены богаче ее!»

Как только девушка осталась одна в своем покое, человечек и в третий раз к ней явился и сказал: «Что мне дашь, если я тебе и в этот раз перепряду всю солому?» — «У меня нет ничего, что бы я могла тебе дать», — отвечала девушка. «Так обещай же, когда будешь королевой, отдать мне первого твоего ребенка».

«Кто знает еще, как оно будет?» — подумала Мельникова дочка и, не зная, чем помочь себе в беде, пообещала человечку, что она исполнит его желание, а человечек за это еще раз перепрял ей всю солому в золото.

И когда на другое утро король пришел и все нашел в том виде, как он желал, то он с ней обвенчался и красавица Мельникова дочь стала королевой.

Год спустя королева родила очень красивого ребенка и совсем позабыла думать о человечке, помогавшем ей в беде, как вдруг он вступил в ее комнату и сказал: «Ну, теперь отдай же мне обещанное».

Королева перепугалась и предлагала ему все сокровища королевства, если только он оставит ей ребенка; но человечек отвечал: «Нет, мне живое существо милее всех сокровищ в мире».

Тогда королева стала так горько плакать и жаловаться на свою участь, что человечек над нею сжалился: «Я тебе даю три дня сроку, — сказал он, — если тебе в течение этого времени удастся узнать мое имя, то ребенок останется при тебе».

Вот и стала королева в течение ночи припоминать все имена, какие ей когда-либо приходилось слышать, и сверх того послала гонца от себя по всей стране и поручила ему всюду справляться, какие еще есть имена.

Когда к ней на другой день пришел человечек, она начала перечислять все известные ей имена, начиная с Каспара, Мельхиора, Бальцера, и перечислила по порядку все, какие знала; но после каждого имени человечек говорил ей: «Нет, меня не так зовут».

На второй день королева приказала разузнавать по соседству, какие еще у людей имена бывают, и стала человечку называть самые необычайные и диковинные имена, говоря: «Может быть, тебя зовут Риннебист или Гаммельсваде, или Шнюрбейн?» — но он на все это отвечал: «Нет, меня так не зовут».

На третий день вернулся гонец и рассказал королеве следующее: «Я не мог отыскать ни одного нового имени, но когда я из-за леса вышел на вершину высокой горы, куда разве только лиса да заяц заглядывают, то я там увидел маленькую хижину, а перед нею разведен был огонек, и около него поскакивал пресмешной человечек, приплясывая на одной ножке и припевая:

Сегодня пеку, завтра пиво варю я,

А затем и дитя королевы беру я;

Хорошо, что не знают — в том я поручусь —

Что Румпельштильцхен я от рожденья зовусь».

Можете себе представить, как была рада королева, когда услышала это имя, и как только вскоре после того человечек вошел к ней с вопросом: «Ну, государыня-королева, как же зовут меня»? — королева спросила сначала: «Может быть, тебя зовут Кунц?» — «Нет». — «Или Гейнц?» — «Нет». — «Так, может быть, Румпельштильцхен?» — «О! Это сам дьявол тебя надоумил, сам дьявол!» — вскричал человечек и со злости так топнул правою ногою в землю, что ушел в нее по пояс, а за левую ногу в ярости ухватился обеими руками и сам себя разорвал пополам.

Сказка о девушке, которую король закрыл в комнате, набитой соломой, и приказал превратить солому в золото. На помощь приходит волшебный гном и помогает девушке выполнить непосильное задание в обмен на ожерелье, кольцо и обещание отдать ему первенца. Когда появляется малыш, девушка просит не забирать его. Гном дает ей три дня, чтобы угадать его имя. Тогда он не станет забирать ребенка. На третий день появляется гонец и сообщает девушке имя гнома – Румпельштильцхен…

Сказка Румпельштильцхен читать

Жил когда-то на свете мельник. Был он беден, но была у него красавица-дочь. Случилось ему однажды вести с королем беседу; и вот, чтоб вызвать к себе уважение, говорит он королю:

— Есть у меня дочка, такая, что умеет прясть из соломы золотую пряжу.

Говорит король мельнику:

— Это дело мне очень нравится. Если дочь у тебя такая искусница, как ты говоришь, то приведи ее завтра ко мне в замок, я посмотрю, как она это умеет делать.

Привел мельник девушку к королю, отвел ее король в комнату, полную соломы, дал ей прялку, веретено и сказал:

— А теперь принимайся за работу; но если ты за ночь к раннему утру не перепрядешь эту солому в золотую пряжу, то не миновать тебе смерти. — Затем он сам запер ее на ключ, и осталась она там одна.

Вот сидит бедная мельникова дочка, не знает, что ей придумать, как свою жизнь спасти, — не умела она из соломы прясть золотой пряжи; и стало ей так страшно, что она, наконец, заплакала. Вдруг открывается дверь, и входит к ней в комнату маленький человечек и говорит:

— Здравствуй, молодая мельничиха! Чего ты так горько плачешь?

— Ax, — ответила девушка, — я должна перепрясть солому в золотую пряжу, а я не знаю, как это сделать.

А человечек и говорит:

— Что ты мне дашь за то, если я тебе ее перепряду?

— Свое ожерелье, — ответила девушка.

Взял человечек у нее ожерелье, подсел к прялке, и — турр-турр-турр — три раза обернется веретено — вот и намотано полное мотовило золотой пряжи. Вставил он другое, и — турр-турр-турр — три раза обернется веретено — вот и второе мотовило полно золотой пряжи; и так работал он до самого утра и перепрял всю солому, и все мотовила были полны золотой пряжи.

Только начало солнце всходить, а король уже явился; как увидел он золотую пряжу, так диву и дался, обрадовался, но стало его сердце еще более жадным к золоту. И он велел отвести Мельникову дочку во вторую комнату, а была она побольше первой и тоже полна соломы, и приказал ей, если жизнь ей дорога, перепрясть всю солому за ночь.

Не знала девушка, как ей быть, как тут горю помочь; но снова открылась дверь, явился маленький человечек и спросил:

— Что ты дашь мне за то, если я перепряду тебе солому в золото?

— Дам тебе с пальца колечко, — ответила девушка.

Взял человечек кольцо, начал снова жужжать веретеном и к утру перепрял всю солому в блестящую золотую пряжу. Король, увидя целые вороха золотой пряжи, обрадовался, но ему и этого золота показалось мало, и он велел отвести мельникову дочку в комнату еще побольше, а было в ней полным-полно соломы, и сказал:

— Ты должна перепрясть все это за ночь. Если тебе это удастся, станешь моею женой. «Хоть она и дочь мельника, — подумал он, — но богаче жены, однако ж, не найти мне во всем свете».

Вот осталась девушка одна, и явился в третий раз маленький человечек и спрашивает:

— Что ты дашь мне за то, если я и на этот раз перепряду за тебя солому?

— У меня больше нет ничего, что я могла бы дать тебе.

— Тогда пообещай мне своего первенца, когда станешь королевой.

«Кто знает, как оно там еще будет!» — подумала Мельникова дочка. Да и как тут было горю помочь? Пришлось посулить человечку то, что он попросил; и за это человечек перепрял ей еще раз солому в золотую пряжу.

Приходит утром король, видит — все сделано, как он хотел. Устроил он тогда свадьбу, и красавица, дочь мельника, стала королевой.

Родила она спустя год прекрасное дитя, а о том человечке и думать позабыла. Как вдруг входит он к ней в комнату и говорит:

— А теперь отдай мне то, что пообещала.

Испугалась королева и стала ему предлагать богатства всего королевства, чтобы он только согласился оставить ей дитя. Но человечек сказал:

— Нет, мне живое милей всех сокровищ на свете.

Запечалилась королева, заплакала, и сжалился над ней человечек:

— Даю тебе три дня сроку, — сказал он, — если за это время ты узнаешь мое имя, то пускай дитя останется у тебя.

Всю ночь королева вспоминала разные имена, которые когда-либо слышала, и отправила гонца по всей стране разведать, какие существуют еще имена. На другое утро явился маленький человечек, и она начала перечислять имена, начиная с Каспара, Мельхиора, Бальцера, и назвала все по порядку, какие только знала, но на каждое имя человечек отвечал:

— Нет, меня зовут не так.

На другой день королева велела разузнать по соседям, как их зовут, и стала называть человечку необычные и редкие имена:

— А может, тебя зовут Риппенбист, или Гаммельсваде, или Шнюрбейн?

Но он всё отвечал:

— Нет, меня зовут не так.

На третий день вернулся гонец и сказал:

— Ни одного нового имени найти я не мог, а вот когда подошел я к высокой горе, покрытой густым лесом, где живут одни только лисы да зайцы, увидел я маленькую избушку, пылал перед нею костер, и скакал через него очень смешной, забавный человечек; он прыгал на одной ножке и кричал:

Нынче пеку, завтра пиво варю,

У королевы дитя отберу;

Ах, хорошо, что никто не знает,

Что Румпельштильцхен меня называют!

Можете себе представить, как обрадовалась королева, услыхав это имя! И вот, когда к ней в комнату вскоре явился человечек и спросил:

— Ну, госпожа королева, как же меня зовут? — она сначала спросила:

— Может быть, Кунц?

— Нет.

— А может быть, Гейнц?

— Нет.

— Так, пожалуй, ты Румпельштильцхен!

— Это тебе сам черт подсказал, сам черт подсказал! — завопил человечек и так сильно топнул в гневе правой ногой, что провалился в землю по самый пояс. А потом схватил в ярости обеими руками левую ногу и сам разорвал себя пополам.

(Илл. Edward Gorey)

❤️ 31

🔥 20

😁 21

😢 7

👎 7

🥱 9

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит

Румпельштильцхен:

Много-много лет назад жил да был мельник, бедный-пребедный, а дочь у него была красавица. Случилось как-то однажды, что пришлось ему говорить с королем, и вот он, чтобы придать себе побольше весу, сказал ему: «Есть у меня дочка, такая-то искусница, что вот и солому тебе в золото перепрясть сумеет». Король сказал мельнику: «Это искусство недурное, и если твоя дочь точно уж такая искусница, как ты говоришь, то приведи ее завтра ко мне в замок, я ее испытаю».

Когда мельник привел свою дочь, король отвел ее в особую каморку, битком набитую соломой, дал ей самопрялку и мотовило и сказал: «Садись-ка за работу; если ты в течение этой ночи до завтрашнего раннего утра не перепрядешь всю эту солому в золото, то велю тебя казнить».

Затем он своими руками запер каморку, и она осталась там одна.

Так и сидела там бедняжка Мельникова дочь и придумать не могла, как ей спастись от лютой смерти. Она и понятия не имела о том, как солому перепрясть в золотые нити, и так пугалась ожидавшей ее участи, что наконец залилась слезами.

Вдруг дверь приотворилась, и к ней в каморку вошел маленький человечек и сказал: «Добрый вечер, Мельникова дочка, о чем ты так плачешь?» — «Ах, ты не знаешь моего горя! — отвечала ему девушка. — Вот всю эту солому я должна перепрясть в золотые нити, а я этого совсем не умею!»

Человечек сказал: «А ты что же мне дашь, если я тебе все это перепряду?» — «Ленточку у меня на шее», — отвечала девушка. Тот взял у нее ленточку, присел за самопрялку да — шур, шур, шур! — три раза обернет, и шпулька намотана золота. Он вставил другую, опять — шур, шур, шур! — три раза обернет, и вторая готова. И так продолжалась работа до самого утра, и вся солома была перепрядена, и все шпульки намотаны золотом.

При восходе солнца пришел король, и когда увидел столько золота, то и удивился, и обрадовался; но сердце его еще сильнее прежнего жаждало золота и золота. Он велел перевести Мельникову дочку в другой покойник, значительно побольше этого, тоже наполненный соломою, и приказал ей всю эту солому также перепрясть в одну ночь, если ей жизнь дорога.

Девушка не знала, как ей быть, и стала плакать, и вновь открылась дверь, явился тот же маленький человечек и сказал: «А что ты мне дашь, если я и эту солому возьмусь тебе перепрясть в золото?» — «С пальчика колечко», — отвечала девушка. Человечек взял колечко, стал опять поскрипывать колесиком самопрялки и к утру успел перепрясть всю солому в блестящее золото.

Король, увидев это, чрезвычайно обрадовался, но ему все еще не довольно было золота; он велел переместить Мельникову дочку в третий покой, еще больше двух первых, битком набитый соломой, и сказал: «И эту ты должна также перепрясть в одну ночь, и если это тебе удастся, я возьму тебя в, супруги себе». А сам про себя подумал: «Хоть она и Мельникова дочь, а все же я и в целом свете не найду себе жены богаче ее!»

Как только девушка осталась одна в своем покое, человечек и в третий раз к ней явился и сказал: «Что мне дашь, если я тебе и в этот раз перепряду всю солому?» — «У меня нет ничего, что бы я могла тебе дать», — отвечала девушка. «Так обещай же, когда будешь королевой, отдать мне первого твоего ребенка».

«Кто знает еще, как оно будет?» — подумала Мельникова дочка и, не зная, чем помочь себе в беде, пообещала человечку, что она исполнит его желание, а человечек за это еще раз перепрял ей всю солому в золото.

И когда на другое утро король пришел и все нашел в том виде, как он желал, то он с ней обвенчался и красавица Мельникова дочь стала королевой.

Год спустя королева родила очень красивого ребенка и совсем позабыла думать о человечке, помогавшем ей в беде, как вдруг он вступил в ее комнату и сказал: «Ну, теперь отдай же мне обещанное».

Королева перепугалась и предлагала ему все сокровища королевства, если только он оставит ей ребенка; но человечек отвечал: «Нет, мне живое существо милее всех сокровищ в мире».

Тогда королева стала так горько плакать и жаловаться на свою участь, что человечек над нею сжалился: «Я тебе даю три дня сроку, — сказал он, — если тебе в течение этого времени удастся узнать мое имя, то ребенок останется при тебе».

Вот и стала королева в течение ночи припоминать все имена, какие ей когда-либо приходилось слышать, и сверх того послала гонца от себя по всей стране и поручила ему всюду справляться, какие еще есть имена.

Когда к ней на другой день пришел человечек, она начала перечислять все известные ей имена, начиная с Каспара, Мельхиора, Бальцера, и перечислила по порядку все, какие знала; но после каждого имени человечек говорил ей: «Нет, меня не так зовут».

На второй день королева приказала разузнавать по соседству, какие еще у людей имена бывают, и стала человечку называть самые необычайные и диковинные имена, говоря: «Может быть, тебя зовут Риннебист или Гаммельсваде, или Шнюрбейн?» — но он на все это отвечал: «Нет, меня так не зовут».

На третий день вернулся гонец и рассказал королеве следующее: «Я не мог отыскать ни одного нового имени, но когда я из-за леса вышел на вершину высокой горы, куда разве только лиса да заяц заглядывают, то я там увидел маленькую хижину, а перед нею разведен был огонек, и около него поскакивал пресмешной человечек, приплясывая на одной ножке и припевая:

Сегодня пеку, завтра пиво варю я,

А затем и дитя королевы беру я;

Хорошо, что не знают — в том я поручусь —

Что Румпельштильцхен я от рожденья зовусь».

Можете себе представить, как была рада королева, когда услышала это имя, и как только вскоре после того человечек вошел к ней с вопросом: «Ну, государыня-королева, как же зовут меня»? — королева спросила сначала: «Может быть, тебя зовут Кунц?» — «Нет». — «Или Гейнц?» — «Нет». — «Так, может быть, Румпельштильцхен?» — «О! Это сам дьявол тебя надоумил, сам дьявол!» — вскричал человечек и со злости так топнул правою ногою в землю, что ушел в нее по пояс, а за левую ногу в ярости ухватился обеими руками и сам себя разорвал пополам.

История персонажа

Немецкие романтики подарили миру незаурядные легенды, которыми до сих пор тешат детей. Братья Гримм были создателями собственной аутентичной мифологии. Каждая история, придуманная ими, помимо сказочного облачения имела страшную подоплеку, в которой замешана психология. Сказки братьев полны кровожадности и суровых расправ, которые становятся заметными при ближайшем рассмотрении. А герои повествований располагают мистической биографией и специфичным характером. Румпельштильцхен относится к их числу.

История создания

Авторы сказки описали злобного хромоногого карлика, обладающего магическими способностями, которые пропадают в том случае, если кто-то произнесет вслух полное имя существа. Поэтому в одиночестве карлик все время повторяет, как хорошо, что никто не знает, как его зовут. Герои произведения называют персонажа «маленьким человечком». Разгадать имя злодея получилось у королевы, чей ребенок подвергся опасности. Зловредный карлик в этот момент разорвал себя на куски.

Кровавая расправа над самим собой плохо сочетается с идеей о детской сказке, но правда такова, что во времена братьев Гримм жанр для детей не был проработан. Их произведения предназначались для взрослой аудитории.

Этимология имени Румпельштильцхен любопытна. Значение имени используется в журналистике, при этом сложно сказать, что оно значит точно. Это производное от глагола «громыхать» и прилагательного «хромающий». Выходит, что братья Гримм написали сказку о громыхающем хромоножке маленького роста.

Карлик обладает магическими навыками. Ловкими руками он прядет из соломы золотые нити и этими же руками может навлечь кошмары на неприятную ему личность. Примечательно, что он обладает нечеловеческой силой, ведь герой смог самостоятельно разорвать себя на куски. Румпельштильцхен – охотник за детьми, которого опасаются родители малышей. При этом карлик готов прийти на помощь. Правда, она окажется не безвозмездной, а плата за услуги будет расти с невероятной скоростью.

Сюжет

Сказка братьев Гримм затейлива и непредсказуема. Она рассказывает о мельнике, в семье которого была красавица дочь. Хвалясь ею перед королем, мельник невзначай сказал, что девушка такая дивная умелица, что может прясть из соломы золотую пряжу. Король запер девушку в дворцовых покоях и велел переработать солому.

Ничего не понимающая героиня находится в отчаянье. К ней на помощь приходит Румпельштильцхен, превративший сырье в золото. Король, понявший, что его не обманули, требует больших результатов производства. Второй раз гном готов оказать помощь за посильную плату – девичье кольцо. Третий раз после королевского требования гном берет с девушки клятву, что в обмен на помощь она отдаст ему будущего ребенка.

Судьба благоволит красавице, и король зовет ее замуж. В семье рождается наследник. Внезапно появившийся Румпельштильцхен напоминает о долге. Гном дает девушке возможность искупить ошибку: за три дня она должна угадать его имя, и в таком случае карлик забудет дорогу к ней. Секретным знанием с королевой делится гонец. Она выкрикивает имя карлика, и злобный хромоножка пропадает из ее жизни навсегда, оставив ребенка и семью в покое.

Вдохновленный историей злобного карлика, Арсений Тарковский посвятил ему одноименное стихотворение, опубликованное в 1957 году.

Экранизации

Первая видеоинтерпретация сказки появилась на больших экранах в 1960 году. Режиссер Кристоф Энгель, не отступая от сюжета легенды, преподнес на суд публике картину «Румпельштильцхен и золотой секрет». Роль карлика исполнил актер Зигфрид Зайбт.

Мрачноватое повествование сказки облек в формат кино режиссер Марк Джонс, выпустив полнометражную ленту «Румпельштильцхен» в 1995 году.

В 2009 году постановщики новой мистической ленты пригласили Роберта Штадлобера на роль Румпельштильцхена.

В 2011 году востребованный сюжет использовали создатели сериала «Однажды в сказке». Роберт Карлайл сыграл роль карлика, вторым именем которого стало Мистер Голд. Важным лейтмотивом в многосерийном фильме оказалась история Белль и Румпельштильцхена. В ленте он предстает магом, существующим в нескольких измерениях. Внешний вид мужчины намекает на то, что ему около 45 лет, хотя он живет на свете уже более трех столетий.

Карлайл сыграл героя, который ненавидит окружающих. В юности он не располагал большими возможностями, но, поднабравшись опыта, к зрелому возрасту обрел невиданную силу. Она позволяла наказать обидчиков, от которых раньше приходилось спасаться. Дружелюбный характер персонажа сломили люди, зарядив его ненавистью и желанием мести. Со временем Румпельштильцхен стал корыстолюбивым и проницательным. Он занимал пассивную выжидательную позицию и довольствовался личной выгодой.

Родители не любили сына. Мать-пьяница умерла, когда он был ребенком. Вскоре этот свет покинул и отец мальчика. Он жил в одиночестве, пока однажды из-за насмешек и стечения случайных обстоятельств не стал женихом первой красавицы в деревне.

Свадьба Румпеля и Белль стала началом новой жизни для парня. В картине девушку звали Мила, и дальнейшая история рассказывала о том, как Румпель и Белль будут вместе жить, преодолевая трудности и преграды.