|

Vladimir Propp |

|

|---|---|

Vladimir Propp in 1928 |

|

| Born | Hermann Waldemar Propp 29 April 1895 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 22 August 1970 (aged 75) Leningrad, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Occupation | Folklorist, scholar |

| Nationality | Russian, Soviet |

| Subject | Folklore of Russia, folklore |

Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp (Russian: Владимир Яковлевич Пропп; 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1895 – 22 August 1970) was a Soviet folklorist and scholar who analysed the basic structural elements of Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible structural units.

Biography[edit]

Vladimir Propp was born on 29 April 1895 in Saint Petersburg to an assimilated Russian family of German descent. His parents, Yakov Philippovich Propp and Anna-Elizaveta Fridrikhovna Propp (née Beisel), were Volga German wealthy peasants from Saratov Governorate. He attended Saint Petersburg University (1913–1918), majoring in Russian and German philology.[1] Upon graduation he taught Russian and German at a secondary school and then became a college teacher of German.

His Morphology of the Folktale was published in Russian in 1928. Although it represented a breakthrough in both folkloristics and morphology and influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, it was generally unnoticed in the West until it was translated in 1958. His morphology is used in media education and has been applied to other types of narrative, be it in literature, theatre, film, television series, games, etc., although Propp applied it specifically to the wonder of fairy tale.

In 1932, Propp became a member of Leningrad University (formerly St. Petersburg University) faculty. After 1938, he chaired the Department of Folklore until it became part of the Department of Russian Literature. Propp remained a faculty member until his death in 1970.[1]

Works in Russian[edit]

His main books are:

- Morphology of the tale, Leningrad 1928

- Historical Roots of the wonder tale, Leningrad 1946

- Russian Epic Song, Leningrad 1955–1958

- Popular Lyric Songs, Leningrad 1961

- Russian Agrarian Feasts, Leningrad 1963

He also published some articles, the most important are:

- The Magical Tree on the tomb

- Wonderful Childbirth

- Ritual Laughter in folklore

- Oedipus in the light of folklore

First printed in specialized reviews, they were republished in Folklore and Reality, Leningrad 1976

Two books were published posthumously:

- Problems of comedy and laughter, Leningrad 1983

- The Russian Folktale, Leningrad 1984

The first book remained unfinished, the second one is the edition of the course he gave in Leningrad university.

Translations into English and other languages[edit]

- Morphology of the Tale was translated into English in 1958 and 1968. It was also translated into Italian and Polish in 1966, French and Romanian in 1970, Spanish in 1971, and German in 1972.

- Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale was translated into Italian in 1949 and 1972, Spanish in 1974, and French, Romanian and Japanese in 1983.

- Oedipus in the light of folklore was translated into Italian in 1975.

- Russian Agrarian Feasts was translated into French in 1987.

Narrative structure[edit]

According to Propp, based on his analysis of 100 folktales from the corpus of Alexander Fyodorovich Afanasyev, there were 31 basic structural elements (or ‘functions’) that typically occurred within Russian fairy tales. He identified these 31 functions as typical of all fairy tales, or wonder tales [skazka] in Russian folklore. These functions occurred in a specific, ascending order (1-31, although not inclusive of all functions within any tale) within each story. This type of structural analysis of folklore is referred to as «syntagmatic». This focus on the events of a story and the order in which they occur is in contrast to another form of analysis, the «paradigmatic» which is more typical of Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist theory of mythology. Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover a narrative’s underlying pattern, regardless of the linear, superficial syntagm, and his structure is usually rendered as a binary oppositional structure. For paradigmatic analysis, the syntagm, or the linear structural arrangement of narratives is irrelevant to their underlying meaning.

Functions[edit]

After the initial situation is depicted, any wonder tale will be composed of a selection of the following 31 functions, in a fixed, consecutive order:[2]

1. ABSENTATION: A member of the hero’s community or family leaves the security of the home environment. This may be the hero themselves, or some other relation that the hero must later rescue. This division of the cohesive family injects initial tension into the storyline. This may serve as the hero’s introduction, typically portraying them as an ordinary person.

2. INTERDICTION: A forbidding edict or command is passed upon the hero (‘don’t go there’, ‘don’t do this’). The hero is warned against some action.

3. VIOLATION of INTERDICTION. The prior rule is violated. Therefore, the hero did not listen to the command or forbidding edict. Whether committed by the Hero by accident or temper, a third party or a foe, this generally leads to negative consequences. The villain enters the story via this event, although not necessarily confronting the hero. They may be a lurking and manipulative presence, or might act against the hero’s family in his absence.

4. RECONNAISSANCE: The villain makes an effort to attain knowledge needed to fulfill their plot. Disguises are often invoked as the villain actively probes for information, perhaps for a valuable item or to abduct someone. They may speak with a family member who innocently divulges a crucial insight. The villain may also seek out the hero in their reconnaissance, perhaps to gauge their strengths in response to learning of their special nature.

5. DELIVERY: The villain succeeds at recon and gains a lead on their intended victim. A map is often involved in some level of the event.

6. TRICKERY: The villain attempts to deceive the victim to acquire something valuable. They press further, aiming to con the protagonists and earn their trust. Sometimes the villain makes little or no deception and instead ransoms one valuable thing for another.

7. COMPLICITY: The victim is fooled or forced to concede and unwittingly or unwillingly helps the villain, who is now free to access somewhere previously off-limits, like the privacy of the hero’s home or a treasure vault, acting without restraint in their ploy.

8. VILLAINY or LACKING: The villain harms a family member, including but not limited to abduction, theft, spoiling crops, plundering, banishment or expulsion of one or more protagonists, murder, threatening a forced marriage, inflicting nightly torments and so on. Simultaneously or alternatively, a protagonist finds they desire or require something lacking from the home environment (potion, artifact, etc.). The villain may still be indirectly involved, perhaps fooling the family member into believing they need such an item.

9. MEDIATION: One or more of the negative factors covered above comes to the attention of the Hero, who uncovers the deceit/perceives the lacking/learns of the villainous acts that have transpired.

10. BEGINNING COUNTERACTION: The hero considers ways to resolve the issues, by seeking a needed magical item, rescuing those who are captured or otherwise thwarting the villain. This is a defining moment for the hero, one that shapes their further actions and marks the point when they begin to fit their noble mantle.

11. DEPARTURE: The hero leaves the home environment, this time with a sense of purpose. Here begins their adventure.

12. FIRST FUNCTION OF THE DONOR: The hero encounters a magical agent or helper (donor) on their path, and is tested in some manner through interrogation, combat, puzzles or more.

13. HERO’S REACTION: The hero responds to the actions of their future donor; perhaps withstanding the rigours of a test and/or failing in some manner, freeing a captive, reconciles disputing parties or otherwise performing good services. This may also be the first time the hero comes to understand the villain’s skills and powers, and uses them for good.

14. RECEIPT OF A MAGICAL AGENT: The hero acquires use of a magical agent as a consequence of their good actions. This may be a directly acquired item, something located after navigating a tough environment, a good purchased or bartered with a hard-earned resource or fashioned from parts and ingredients prepared by the hero, spontaneously summoned from another world, a magical food that is consumed, or even the earned loyalty and aid of another.

15. GUIDANCE: The hero is transferred, delivered or somehow led to a vital location, perhaps related to one of the above functions such as the home of the donor or the location of the magical agent or its parts, or to the villain.

16. STRUGGLE: The hero and villain meet and engage in conflict directly, either in battle or some nature of contest.

17. BRANDING: The hero is marked in some manner, perhaps receiving a distinctive scar or granted a cosmetic item like a ring or scarf.

18. VICTORY: The villain is defeated by the hero – killed in combat, outperformed in a contest, struck when vulnerable, banished, and so on.

19. LIQUIDATION: The earlier misfortunes or issues of the story are resolved; objects of search are distributed, spells broken, captives freed.

20. RETURN: The hero travels back to their home.

21. PURSUIT: The hero is pursued by some threatening adversary, who perhaps seek to capture or eat them.

22. RESCUE: The hero is saved from a chase. Something may act as an obstacle to delay the pursuer, or the hero may find or be shown a way to hide, up to and including transformation unrecognisably. The hero’s life may be saved by another.

23. UNRECOGNIZED ARRIVAL: The hero arrives, whether in a location along their journey or in their destination, and is unrecognised or unacknowledged.

24. UNFOUNDED CLAIMS: A false hero presents unfounded claims or performs some other form of deceit. This may be the villain, one of the villain’s underlings or an unrelated party. It may even be some form of future donor for the hero, once they’ve faced their actions.

25. DIFFICULT TASK: A trial is proposed to the hero – riddles, test of strength or endurance, acrobatics and other ordeals.

26. SOLUTION: The hero accomplishes a difficult task.

27. RECOGNITION: The hero is given due recognition – usually by means of their prior branding.

28. EXPOSURE: The false hero and/or villain is exposed to all and sundry.

29. TRANSFIGURATION: The hero gains a new appearance. This may reflect aging and/or the benefits of labour and health, or it may constitute a magical remembering after a limb or digit was lost (as a part of the branding or from failing a trial). Regardless, it serves to improve their looks.

30. PUNISHMENT: The villain suffers the consequences of their actions, perhaps at the hands of the hero, the avenged victims, or as a direct result of their own ploy.

31. WEDDING: The hero marries and is rewarded or promoted by the family or community, typically ascending to a throne.

Some of these functions may be inverted, such as the hero receives an artifact of power whilst still at home, thus fulfilling the donor function early. Typically such functions are negated twice, so that it must be repeated three times in Western cultures.[3]

Characters[edit]

He also concluded that all the characters in tales could be resolved into 7 abstract character functions

- The villain — an evil character that creates struggles for the hero.

- The dispatcher — any character who illustrates the need for the hero’s quest and sends the hero off. This often overlaps with the princess’s father.

- The helper — a typically magical entity that comes to help the hero in their quest.

- The princess or prize, and often her father — the hero deserves her throughout the story but is unable to marry her as a consequence of some evil or injustice, perhaps the work of the villain. The hero’s journey is often ended when he marries the princess, which constitutes the villain’s defeat.

- The donor — a character that prepares the hero or gives the hero some magical object, sometimes after testing them.

- The hero — the character who reacts to the dispatcher and donor characters, thwarts the villain, resolves any lacking or wronghoods and weds the princess.

- The false hero — a Miles Gloriosus figure who takes credit for the hero’s actions or tries to marry the princess.[4]

These roles could sometimes be distributed among various characters, as the hero kills the villain dragon, and the dragon’s sisters take on the villainous role of chasing him. Conversely, one character could engage in acts as more than one role, as a father could send his son on the quest and give him a sword, acting as both dispatcher and donor.[5]

Criticism[edit]

Propp’s approach has been criticized for its excessive formalism (a major critique of the Soviets). One of the most prominent critics of Propp was structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, in dialogue with Propp, argued for the superiority of the paradigmatic over syntagmatic approach.[6] Propp responded to this criticism in a sharply-worded rebuttal: he wrote that Lévi-Strauss showed no interest in empirical investigation.[7]

See also[edit]

- Aarne–Thompson classification system

References[edit]

- ^ a b Propp, Vladimir. «Introduction.» Theory and History of Folklore. Ed. Anatoly Liberman. University of Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. pg ix

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 25, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 74, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 79-80, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 81, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Dundes, Alan. «Binary Opposition in Myth: The Propp/Levi-Strauss Debate in Retrospect,» Western Folklore, 56.1 (Winter 1997)

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Theory and History of Folklore (Theory and History of Literature #5)

by Vladimir Propp, Ariadna Y. Martin (Translator), Richard P. Martin (Translator), Anatoly Liberman

External links[edit]

- The Functions of the Dramatis Personae

- The 31 narrative units of Propp’s formula — Jerry Everard

- The Birth of Structuralism from the Analysis of Fairy-Tales – Dmitry Olshansky / Toronto Slavic Quarterly, No. 25

- The Fairy Tale Generator: generate your own Inaccessible as of 12 Oct 2012, but available via«Proppian Fairy Tale Generator v1.0». Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Criticism

- Vladimir Propp (1895-1970) / The Literary Encyclopedia (2008)

- Assessment of Propp (in German)

- A Folktale Outline Generator: based on Propp’s Morphology

- The Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale Propp’s examination of the origin of specific folktale motifs in customs and beliefs, initiation rites. (in Russian)

- Linguistic Formalists by C. John Holcombe An interesting essay through the story of Russian Formalism.

- Biography of Vladimir Propp at the Gallery of Russian Thinkers

- An XML Markup language based on Propp at the University of Pittsburgh

|

Vladimir Propp |

|

|---|---|

Vladimir Propp in 1928 |

|

| Born | Hermann Waldemar Propp 29 April 1895 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 22 August 1970 (aged 75) Leningrad, Russian SFSR, USSR |

| Occupation | Folklorist, scholar |

| Nationality | Russian, Soviet |

| Subject | Folklore of Russia, folklore |

Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp (Russian: Владимир Яковлевич Пропп; 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1895 – 22 August 1970) was a Soviet folklorist and scholar who analysed the basic structural elements of Russian folk tales to identify their simplest irreducible structural units.

Biography[edit]

Vladimir Propp was born on 29 April 1895 in Saint Petersburg to an assimilated Russian family of German descent. His parents, Yakov Philippovich Propp and Anna-Elizaveta Fridrikhovna Propp (née Beisel), were Volga German wealthy peasants from Saratov Governorate. He attended Saint Petersburg University (1913–1918), majoring in Russian and German philology.[1] Upon graduation he taught Russian and German at a secondary school and then became a college teacher of German.

His Morphology of the Folktale was published in Russian in 1928. Although it represented a breakthrough in both folkloristics and morphology and influenced Claude Lévi-Strauss and Roland Barthes, it was generally unnoticed in the West until it was translated in 1958. His morphology is used in media education and has been applied to other types of narrative, be it in literature, theatre, film, television series, games, etc., although Propp applied it specifically to the wonder of fairy tale.

In 1932, Propp became a member of Leningrad University (formerly St. Petersburg University) faculty. After 1938, he chaired the Department of Folklore until it became part of the Department of Russian Literature. Propp remained a faculty member until his death in 1970.[1]

Works in Russian[edit]

His main books are:

- Morphology of the tale, Leningrad 1928

- Historical Roots of the wonder tale, Leningrad 1946

- Russian Epic Song, Leningrad 1955–1958

- Popular Lyric Songs, Leningrad 1961

- Russian Agrarian Feasts, Leningrad 1963

He also published some articles, the most important are:

- The Magical Tree on the tomb

- Wonderful Childbirth

- Ritual Laughter in folklore

- Oedipus in the light of folklore

First printed in specialized reviews, they were republished in Folklore and Reality, Leningrad 1976

Two books were published posthumously:

- Problems of comedy and laughter, Leningrad 1983

- The Russian Folktale, Leningrad 1984

The first book remained unfinished, the second one is the edition of the course he gave in Leningrad university.

Translations into English and other languages[edit]

- Morphology of the Tale was translated into English in 1958 and 1968. It was also translated into Italian and Polish in 1966, French and Romanian in 1970, Spanish in 1971, and German in 1972.

- Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale was translated into Italian in 1949 and 1972, Spanish in 1974, and French, Romanian and Japanese in 1983.

- Oedipus in the light of folklore was translated into Italian in 1975.

- Russian Agrarian Feasts was translated into French in 1987.

Narrative structure[edit]

According to Propp, based on his analysis of 100 folktales from the corpus of Alexander Fyodorovich Afanasyev, there were 31 basic structural elements (or ‘functions’) that typically occurred within Russian fairy tales. He identified these 31 functions as typical of all fairy tales, or wonder tales [skazka] in Russian folklore. These functions occurred in a specific, ascending order (1-31, although not inclusive of all functions within any tale) within each story. This type of structural analysis of folklore is referred to as «syntagmatic». This focus on the events of a story and the order in which they occur is in contrast to another form of analysis, the «paradigmatic» which is more typical of Lévi-Strauss’s structuralist theory of mythology. Lévi-Strauss sought to uncover a narrative’s underlying pattern, regardless of the linear, superficial syntagm, and his structure is usually rendered as a binary oppositional structure. For paradigmatic analysis, the syntagm, or the linear structural arrangement of narratives is irrelevant to their underlying meaning.

Functions[edit]

After the initial situation is depicted, any wonder tale will be composed of a selection of the following 31 functions, in a fixed, consecutive order:[2]

1. ABSENTATION: A member of the hero’s community or family leaves the security of the home environment. This may be the hero themselves, or some other relation that the hero must later rescue. This division of the cohesive family injects initial tension into the storyline. This may serve as the hero’s introduction, typically portraying them as an ordinary person.

2. INTERDICTION: A forbidding edict or command is passed upon the hero (‘don’t go there’, ‘don’t do this’). The hero is warned against some action.

3. VIOLATION of INTERDICTION. The prior rule is violated. Therefore, the hero did not listen to the command or forbidding edict. Whether committed by the Hero by accident or temper, a third party or a foe, this generally leads to negative consequences. The villain enters the story via this event, although not necessarily confronting the hero. They may be a lurking and manipulative presence, or might act against the hero’s family in his absence.

4. RECONNAISSANCE: The villain makes an effort to attain knowledge needed to fulfill their plot. Disguises are often invoked as the villain actively probes for information, perhaps for a valuable item or to abduct someone. They may speak with a family member who innocently divulges a crucial insight. The villain may also seek out the hero in their reconnaissance, perhaps to gauge their strengths in response to learning of their special nature.

5. DELIVERY: The villain succeeds at recon and gains a lead on their intended victim. A map is often involved in some level of the event.

6. TRICKERY: The villain attempts to deceive the victim to acquire something valuable. They press further, aiming to con the protagonists and earn their trust. Sometimes the villain makes little or no deception and instead ransoms one valuable thing for another.

7. COMPLICITY: The victim is fooled or forced to concede and unwittingly or unwillingly helps the villain, who is now free to access somewhere previously off-limits, like the privacy of the hero’s home or a treasure vault, acting without restraint in their ploy.

8. VILLAINY or LACKING: The villain harms a family member, including but not limited to abduction, theft, spoiling crops, plundering, banishment or expulsion of one or more protagonists, murder, threatening a forced marriage, inflicting nightly torments and so on. Simultaneously or alternatively, a protagonist finds they desire or require something lacking from the home environment (potion, artifact, etc.). The villain may still be indirectly involved, perhaps fooling the family member into believing they need such an item.

9. MEDIATION: One or more of the negative factors covered above comes to the attention of the Hero, who uncovers the deceit/perceives the lacking/learns of the villainous acts that have transpired.

10. BEGINNING COUNTERACTION: The hero considers ways to resolve the issues, by seeking a needed magical item, rescuing those who are captured or otherwise thwarting the villain. This is a defining moment for the hero, one that shapes their further actions and marks the point when they begin to fit their noble mantle.

11. DEPARTURE: The hero leaves the home environment, this time with a sense of purpose. Here begins their adventure.

12. FIRST FUNCTION OF THE DONOR: The hero encounters a magical agent or helper (donor) on their path, and is tested in some manner through interrogation, combat, puzzles or more.

13. HERO’S REACTION: The hero responds to the actions of their future donor; perhaps withstanding the rigours of a test and/or failing in some manner, freeing a captive, reconciles disputing parties or otherwise performing good services. This may also be the first time the hero comes to understand the villain’s skills and powers, and uses them for good.

14. RECEIPT OF A MAGICAL AGENT: The hero acquires use of a magical agent as a consequence of their good actions. This may be a directly acquired item, something located after navigating a tough environment, a good purchased or bartered with a hard-earned resource or fashioned from parts and ingredients prepared by the hero, spontaneously summoned from another world, a magical food that is consumed, or even the earned loyalty and aid of another.

15. GUIDANCE: The hero is transferred, delivered or somehow led to a vital location, perhaps related to one of the above functions such as the home of the donor or the location of the magical agent or its parts, or to the villain.

16. STRUGGLE: The hero and villain meet and engage in conflict directly, either in battle or some nature of contest.

17. BRANDING: The hero is marked in some manner, perhaps receiving a distinctive scar or granted a cosmetic item like a ring or scarf.

18. VICTORY: The villain is defeated by the hero – killed in combat, outperformed in a contest, struck when vulnerable, banished, and so on.

19. LIQUIDATION: The earlier misfortunes or issues of the story are resolved; objects of search are distributed, spells broken, captives freed.

20. RETURN: The hero travels back to their home.

21. PURSUIT: The hero is pursued by some threatening adversary, who perhaps seek to capture or eat them.

22. RESCUE: The hero is saved from a chase. Something may act as an obstacle to delay the pursuer, or the hero may find or be shown a way to hide, up to and including transformation unrecognisably. The hero’s life may be saved by another.

23. UNRECOGNIZED ARRIVAL: The hero arrives, whether in a location along their journey or in their destination, and is unrecognised or unacknowledged.

24. UNFOUNDED CLAIMS: A false hero presents unfounded claims or performs some other form of deceit. This may be the villain, one of the villain’s underlings or an unrelated party. It may even be some form of future donor for the hero, once they’ve faced their actions.

25. DIFFICULT TASK: A trial is proposed to the hero – riddles, test of strength or endurance, acrobatics and other ordeals.

26. SOLUTION: The hero accomplishes a difficult task.

27. RECOGNITION: The hero is given due recognition – usually by means of their prior branding.

28. EXPOSURE: The false hero and/or villain is exposed to all and sundry.

29. TRANSFIGURATION: The hero gains a new appearance. This may reflect aging and/or the benefits of labour and health, or it may constitute a magical remembering after a limb or digit was lost (as a part of the branding or from failing a trial). Regardless, it serves to improve their looks.

30. PUNISHMENT: The villain suffers the consequences of their actions, perhaps at the hands of the hero, the avenged victims, or as a direct result of their own ploy.

31. WEDDING: The hero marries and is rewarded or promoted by the family or community, typically ascending to a throne.

Some of these functions may be inverted, such as the hero receives an artifact of power whilst still at home, thus fulfilling the donor function early. Typically such functions are negated twice, so that it must be repeated three times in Western cultures.[3]

Characters[edit]

He also concluded that all the characters in tales could be resolved into 7 abstract character functions

- The villain — an evil character that creates struggles for the hero.

- The dispatcher — any character who illustrates the need for the hero’s quest and sends the hero off. This often overlaps with the princess’s father.

- The helper — a typically magical entity that comes to help the hero in their quest.

- The princess or prize, and often her father — the hero deserves her throughout the story but is unable to marry her as a consequence of some evil or injustice, perhaps the work of the villain. The hero’s journey is often ended when he marries the princess, which constitutes the villain’s defeat.

- The donor — a character that prepares the hero or gives the hero some magical object, sometimes after testing them.

- The hero — the character who reacts to the dispatcher and donor characters, thwarts the villain, resolves any lacking or wronghoods and weds the princess.

- The false hero — a Miles Gloriosus figure who takes credit for the hero’s actions or tries to marry the princess.[4]

These roles could sometimes be distributed among various characters, as the hero kills the villain dragon, and the dragon’s sisters take on the villainous role of chasing him. Conversely, one character could engage in acts as more than one role, as a father could send his son on the quest and give him a sword, acting as both dispatcher and donor.[5]

Criticism[edit]

Propp’s approach has been criticized for its excessive formalism (a major critique of the Soviets). One of the most prominent critics of Propp was structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who, in dialogue with Propp, argued for the superiority of the paradigmatic over syntagmatic approach.[6] Propp responded to this criticism in a sharply-worded rebuttal: he wrote that Lévi-Strauss showed no interest in empirical investigation.[7]

See also[edit]

- Aarne–Thompson classification system

References[edit]

- ^ a b Propp, Vladimir. «Introduction.» Theory and History of Folklore. Ed. Anatoly Liberman. University of Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. pg ix

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 25, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 74, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 79-80, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p 81, ISBN 0-292-78376-0

- ^ Dundes, Alan. «Binary Opposition in Myth: The Propp/Levi-Strauss Debate in Retrospect,» Western Folklore, 56.1 (Winter 1997)

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Theory and History of Folklore (Theory and History of Literature #5)

by Vladimir Propp, Ariadna Y. Martin (Translator), Richard P. Martin (Translator), Anatoly Liberman

External links[edit]

- The Functions of the Dramatis Personae

- The 31 narrative units of Propp’s formula — Jerry Everard

- The Birth of Structuralism from the Analysis of Fairy-Tales – Dmitry Olshansky / Toronto Slavic Quarterly, No. 25

- The Fairy Tale Generator: generate your own Inaccessible as of 12 Oct 2012, but available via«Proppian Fairy Tale Generator v1.0». Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Criticism

- Vladimir Propp (1895-1970) / The Literary Encyclopedia (2008)

- Assessment of Propp (in German)

- A Folktale Outline Generator: based on Propp’s Morphology

- The Historical Roots of the Wonder Tale Propp’s examination of the origin of specific folktale motifs in customs and beliefs, initiation rites. (in Russian)

- Linguistic Formalists by C. John Holcombe An interesting essay through the story of Russian Formalism.

- Biography of Vladimir Propp at the Gallery of Russian Thinkers

- An XML Markup language based on Propp at the University of Pittsburgh

Одним из выдающихся

исследователей фольклора, и в особенности,

сказки, был отечественный ученый Владимир

Яковлевич Пропп (1895-1970 гг.). На материале

исследования структуры волшебной сказки

он впервые в гуманитарных науках применил

точные методы анализа для выявления

единой схемы, лежащей в основе фольклорных

текстов.

В.Я. Пропп показал,

что во всех русских волшебных сказках

обнаруживается одинаковый набор

персонажей, связанных между собой

однотипными сюжетными отношениями

(функциями), благодаря чему сюжетная

схема для всех сказок единообразна (но

возможен либо пропуск некоторых

необязательных отношений, или их

циклическое повторение). Для выражения

установленной им на основе индуктивной

обработки материала схемы В.Я. Пропп

ввел формальную запись.

Его труд «Морфология

сказки» (1928 г.), получил мировое признание

как первый опыт структурного анализа

художественных текстов. Историческую

интерпретацию выявленной им морфологической

структуры сказки он дал позднее на

основе идеи об отражении в ней древнего

обряда инициации (посвящения юноши в

тайны племени).

Продолжение и

развитие разработки В.Я. Проппа нашли

в исследованиях других ученых, применявших

те же или сходные методы (К. Леви-Стросс),

и не только для анализа фольклора, но и

для иных типов художественных текстов.

В.Я. Пропп привлек

фольклорный материал и типологические

сопоставления с архаическими обрядами

для объяснения мифологических сюжетов

древней литературы (в частности,

древнегреческого мифа об Эдипе).

Предложенное им истолкование ритуального

смеха над смертью оказало влияние на

разработку эстетической теории карнавала.

Представляет интерес его исследование

о мотиве змееборства в изобразительном

искусстве Ладоги в сопоставлении с

фольклорными стихами.

Труды В.Я. Проппа:

«Морфология сказки» (1928), «Исторические

корни волшебной сказки» (1946). «Русский

героический эпос» (1955); «Русские аграрные

праздники», «Фольклор и действительность»

(1976), «Проблемы комизма и смеха» (1976).

Литература:

1. Мелетинский,

Е.М. Герой волшебной сказки / Е.М.

Мелетинский. Москва —

Санкт-Петербург : Академия исследований

культуры, 2005. —

240 с.

3. Пропп, В.Я.

Морфология сказки / В.Я. Пропп.

— Москва

: Лабиринт, 1998.

— 154 с.

4. Пропп, В.Я.

Исторические корни волшебной сказки /

В.Я. Пропп.

— Москва

: Лабиринт, 2002.

— 333 с.

5. Русские народные

сказки / сост и вст. ст. В.П. Аникина. —

Москва : Худ. лит., 2000. —

560 с.

Тема 2.10. Народный героический эпос

Древнегреческий

эпос : Илиада, Одиссея. Проблема авторства

Гомера (Вольф, 1795), как проблема фольклорного

творчества. Средневековый рыцарско-дружинный

эпос : Песнь о Роланде, Песнь о Сиде.

Древнегерманский эпос: Песнь о Нибелунгах.

Исландские саги. Слово о полку Игореве

—

древнерусский эпический памятник.

Калевала —

карело-финский эпос.

Русские былины.

Определение

жанра.

Собиратели

русских былин

(Рыбников, Гильфердинг).

Время

и

место

записи.

Исполнители былин (Трофимов, Крюкова и

др.).

Мифологическая,

заимствования,

историческая

школы

в изучении

русских былин.

Многослойность

художественного текста былин.

Характер

бытования

былин.

Распевность русских

былин. Поэтика

былин. Композиция. Общие места. Повторения.

Типизация и гипербола. Система

художественно-выразительных средств.

Сравнения. Эпитеты.

Циклизация былин.

Былины «киевского» и «новгородского»

циклов. Своеобразие мифологических и

классических былин. Проблема

их

исторической

периодизации.

Взаимодействие

былин с другими жанрами фольклора.

Разграничение былины, сказки и исторической

песни.

Литература:

1. Русские былины

// Древние славяне : сборник / Мифы и

легенды народов мира. —

Москва : Литература, Мир книги, 2004. —

С. 151-326.

2. Устное народное

творчество // Народная художественная

культура : учебник. / под общ. ред. Т.И.

Баклановой, Е.Ю. Стрельцовой. —

Москва : МГУКИ, 2000. —

С. 160-176.

3. Новиков, В.С.

Феноменология фольклора : монография

/ В.С. Новиков. —

Тюмень : РИЦ ТГАКИ, 2007. —

132 с.

4. Родная старина.

Слова, термины, образы / сост. Е.А. Князев.

—

Москва : Остожье, 2006. —164

с.

Соседние файлы в папке СКД.НХК

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Слайд 1

Игра в карты Проппа

как средство развития речи

старших дошкольников.

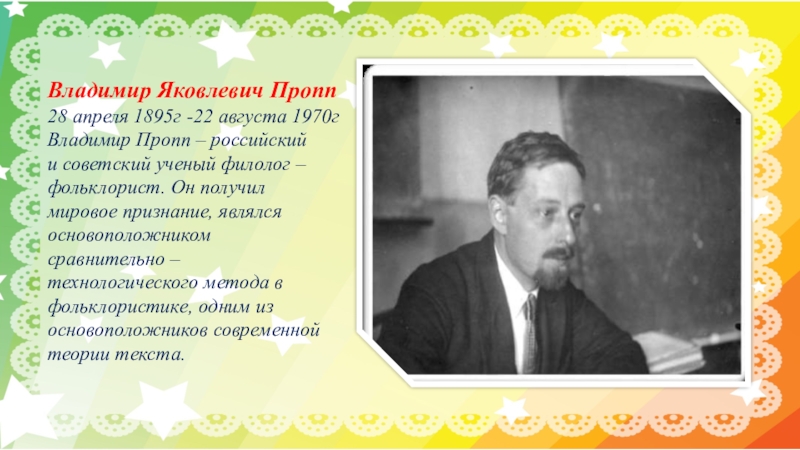

Слайд 2Владимир Яковлевич Пропп

28 апреля 1895г -22 августа 1970г

Владимир Пропп – российский

и

советский ученый филолог –

фольклорист. Он получил

мировое признание, являлся

основоположником

сравнительно –

технологического метода в

фольклористике, одним из

основоположников современной

теории текста.

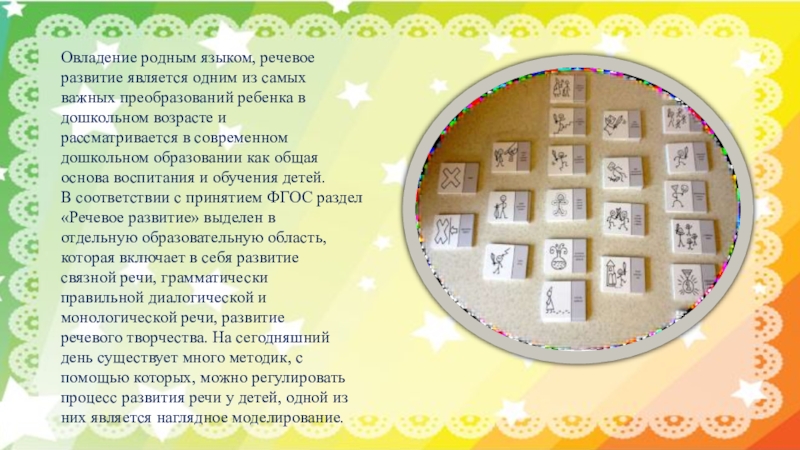

Слайд 3Овладение родным языком, речевое

развитие является одним из самых

важных преобразований ребенка в

дошкольном

возрасте и

рассматривается в современном

дошкольном образовании как общая

основа воспитания и обучения детей.

В соответствии с принятием ФГОС раздел

«Речевое развитие» выделен в

отдельную образовательную область,

которая включает в себя развитие

связной речи, грамматически

правильной диалогической и

монологической речи, развитие

речевого творчества. На сегодняшний

день существует много методик, с

помощью которых, можно регулировать

процесс развития речи у детей, одной из

них является наглядное моделирование.

Слайд 4

Что такое карты ПРОППА?

Известный исследователь сказок В.Я. Пропп проанализировал структуру

русских народных

сказок и выделил в них набор постоянных

структурных элементов, или функций. При помощи карт Проппа

можно легко проанализировать структуру сказки, разбив ее на

функции. Это поможет ребенку лучше усвоить содержание сказки и

облегчит пересказ.

Каждая из представленных в сказке функций помогает ребенку

разобраться в самом себе, и в окружающем его мире людей.

Целесообразность карт Проппа состоит в том, что ребенок выступает

не просто в роли пассивного наблюдателя, слушателя, а является

энергетическим центом творческой деятельности, создателям

оригинальных литературных произведений.

Так как Пропп был фольклорист, то он рекомендовал работать с

волшебными сказками.

Слайд 5Развитие связной речи у дошкольников через моделирование с использованием карт Проппа

решает следующие задачи:

Расширяется и активизируется словарный запас детей,

совершенствуется диалогическая и монологическая речь.

Развивается наглядно-образное и формируется словесно-логическое

мышление.

Развивается интерес к художественной литературе, как образцу

речи

Способствует повышению поисковой активности.

Воспитывается человечность: способность переживать судьбу

сказочных героев

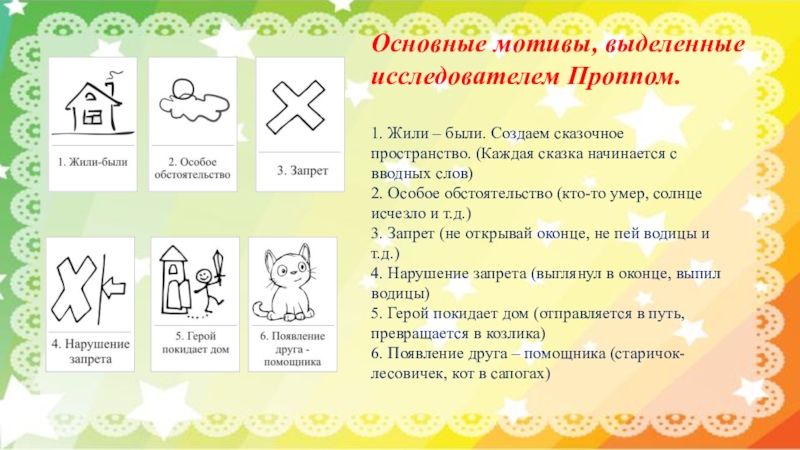

Слайд 6Основные мотивы, выделенные

исследователем Проппом.

1. Жили – были. Создаем сказочное

пространство. (Каждая сказка

начинается с

вводных слов)

2. Особое обстоятельство (кто-то умер, солнце

исчезло и т.д.)

3. Запрет (не открывай оконце, не пей водицы и

т.д.)

4. Нарушение запрета (выглянул в оконце, выпил

водицы)

5. Герой покидает дом (отправляется в путь,

превращается в козлика)

6. Появление друга – помощника (старичок-

лесовичек, кот в сапогах)

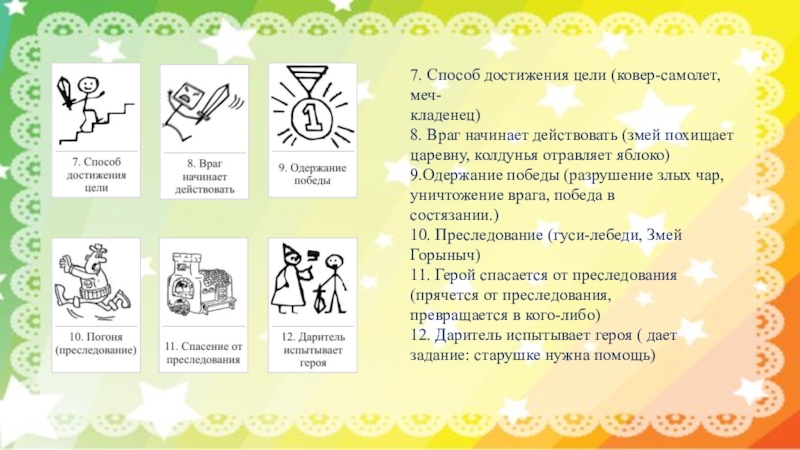

Слайд 7

7. Способ достижения цели (ковер-самолет,меч-

кладенец)

8. Враг начинает действовать (змей похищает

царевну, колдунья

отравляет яблоко)

9.Одержание победы (разрушение злых чар,

уничтожение врага, победа в

состязании.)

10. Преследование (гуси-лебеди, Змей

Горыныч)

11. Герой спасается от преследования

(прячется от преследования,

превращается в кого-либо)

12. Даритель испытывает героя ( дает

задание: старушке нужна помощь)

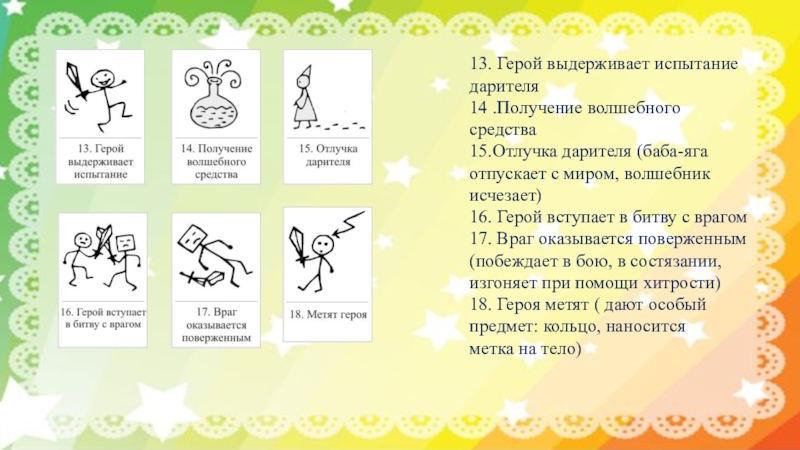

Слайд 813. Герой выдерживает испытание

дарителя

14 .Получение волшебного средства

15.Отлучка дарителя (баба-яга отпускает с

миром, волшебник исчезает)

16. Герой вступает в битву с врагом

17. Враг оказывается поверженным (побеждает в бою, в состязании,

изгоняет при помощи хитрости)

18. Героя метят ( дают особый

предмет: кольцо, наносится

метка на тело)

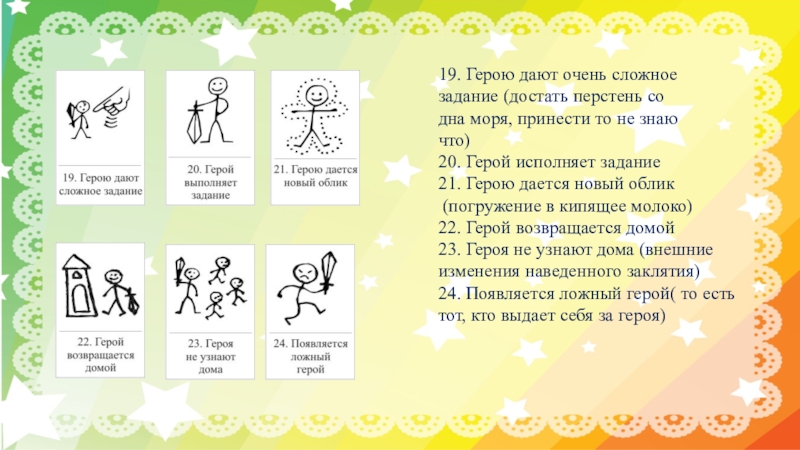

Слайд 919. Герою дают очень сложное

задание (достать перстень со

дна моря, принести то

не знаю

что)

20. Герой исполняет задание

21. Герою дается новый облик

(погружение в кипящее молоко)

22. Герой возвращается домой

23. Героя не узнают дома (внешние изменения наведенного заклятия)

24. Появляется ложный герой( то есть тот, кто выдает себя за героя)

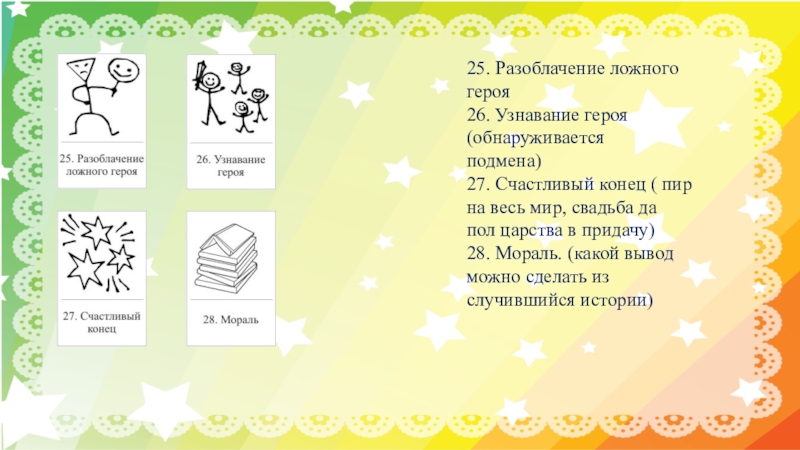

Слайд 1025. Разоблачение ложного

героя

26. Узнавание героя

(обнаруживается

подмена)

27. Счастливый конец ( пир

на весь мир,

свадьба да

пол царства в придачу)

28. Мораль. (какой вывод

можно сделать из

случившийся истории)

Слайд 11Целесообразность карт Проппа

Наглядность позволяет ребенку удерживать в памяти гораздо большее количество

информации.

Представленные в картах функции являются обобщенными действиями, что позволяет ребенку абстрагироваться от конкретного поступка героя, а, следовательно, у ребенка развивается абстрактное, логическое мышление.

Карты стимулируют развитие внимания, восприятия, фантазии, творческого воображения, волевых качеств; обогащают эмоциональную сферу, активизируют связную речь, обогащают словарь; способствуют повышению поисковой активности.

Слайд 12

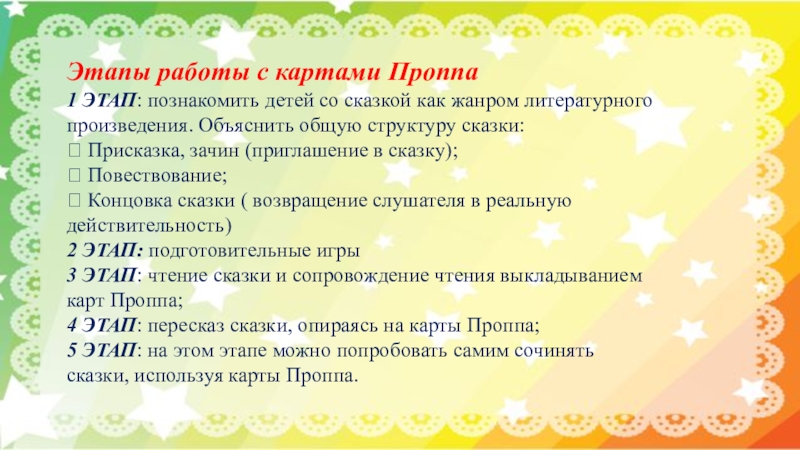

Этапы работы с картами Проппа

1 ЭТАП: познакомить детей со сказкой как

жанром литературного

произведения. Объяснить общую структуру сказки:

Присказка, зачин (приглашение в сказку);

Повествование;

Концовка сказки ( возвращение слушателя в реальную

действительность)

2 ЭТАП: подготовительные игры

3 ЭТАП: чтение сказки и сопровождение чтения выкладыванием

карт Проппа;

4 ЭТАП: пересказ сказки, опираясь на карты Проппа;

5 ЭТАП: на этом этапе можно попробовать самим сочинять

сказки, используя карты Проппа.

Слайд 13«Чудеса в решете» — выявление различных чудес: как и с помощью

чего осуществляется превращение, волшебство.

«Волшебные слова» или сказочные приговоры, несущие основную смысловую нагрузку.

« Что в дороге пригодится»-основные волшебные средства сказки (скатерть-самобранка, аленький цветочек)

«Узнай героя» — выявление позитивных и негативных черт характера героев.

«Что общего» — сравнительный анализ сказок с точки зрения сходства и различий между ними

« Четвертый лишний» — определение лишнего предмета.

«Решение сказочных задач»

«Бюро находок» — найден золотой инкубатор для золотых яиц; утеряна трехворотниковая кольчуга и т.д.

«Сказочный словарь» — придумайте новое небывалое слово и по возможности объясните его или нарисуйте: сапоги-скороходы, ковер-самолет, шапка-невидимка.

2 этап: Подготовительные игры

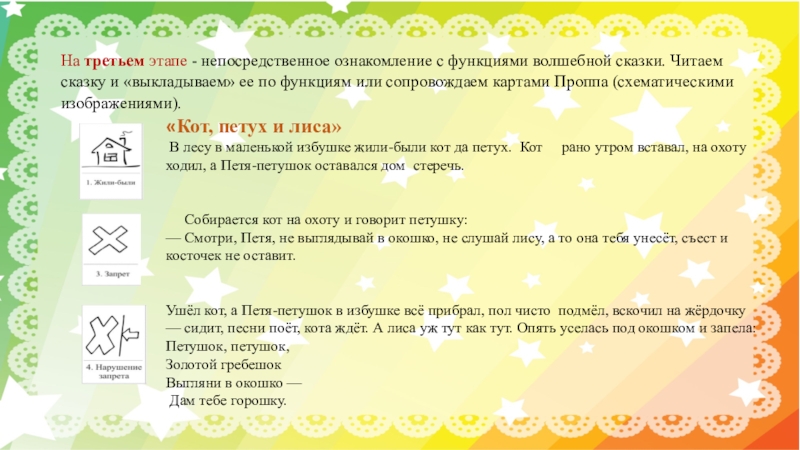

Слайд 14На третьем этапе — непосредственное ознакомление с функциями волшебной сказки. Читаем сказку и

«выкладываем» ее по функциям или сопровождаем картами Проппа (схематическими изображениями).

«Кот, петух и лиса»

В лесу в маленькой избушке жили-были кот да петух. Кот рано утром вставал, на охоту ходил, а Петя-петушок оставался дом стеречь.

Cобирается кот на охоту и говорит петушку:

— Смотри, Петя, не выглядывай в окошко, не слушай лису, а то она тебя унесёт, съест и косточек не оставит.

Ушёл кот, а Петя-петушок в избушке всё прибрал, пол чисто подмёл, вскочил на жёрдочку — сидит, песни поёт, кота ждёт. А лиса уж тут как тут. Опять уселась под окошком и запела:

Петушок, петушок,

Золотой гребешок

Выгляни в окошко —

Дам тебе горошку.

Слайд 15

Петя выглянул, а лиса его — цап-царап — схватила

и понесла. Петушок испугался, закричал:

— Несёт меня лиса за тёмные леса, за высокие горы. Котик- братик, выручи меня.

Кот хоть далеко был, а услыхал петушка. Погнался за лисой что было духу, догнал её, отнял петушка и принёс его домой.

С тех пор опять кот да петух живут вместе, а лиса уж больше к ним не показывается.

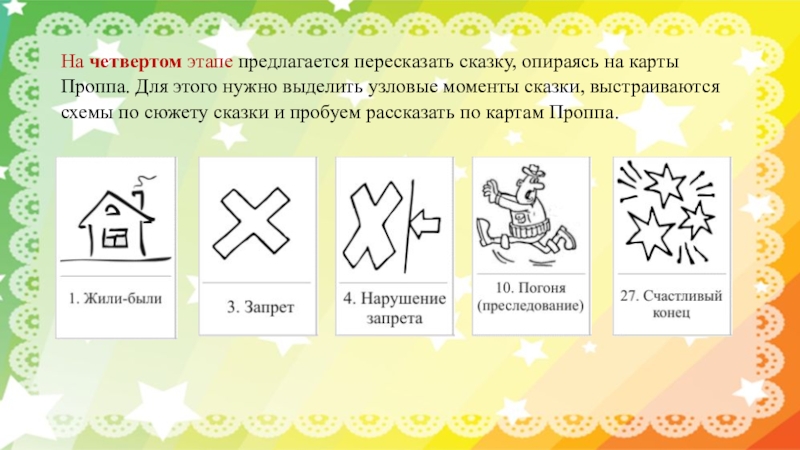

Слайд 16На четвертом этапе предлагается пересказать сказку, опираясь на карты Проппа. Для этого нужно

выделить узловые моменты сказки, выстраиваются схемы по сюжету сказки и пробуем рассказать по картам Проппа.

Слайд 17На пятом этапе происходит сочинение собственных сказок — предлагается набор из 5-6 карт,

заранее оговаривается кто будет главным героем, кто или что будет мешать герою, какие волшебные средства будут у героя, какой будет зачин и концовка ,какие сказочные слова будут в сказке и т.д. Можно также использовать такие игры, как: «Салат из сказок», «Опорные слова», «Добавление», «Сказочный треугольник (разделение на три группы, где у каждой свое задание), «Сказочная путаница». Затем вводятся новые характеристики антигероев и рассмотрение их с другой стороны (Баба Яга как даритель) и т. д. В конце — концов, дети приходят к сочинению своей неповторимой волшебной сказки.

Слайд 18Последовательность знакомства с картами

Изготовление карт. Карты, используемые в начале работы, должны

быть выполнены в сюжетной манере и красочно. В дальнейшем, пользуются картами с довольно схематичным изображением каждой функции смысл, которой был бы понятен детям, или вместе с ними оговорите каждое изображение.

Воспроизведение знакомой сказки, дифференциация: посмысловые части и соотношения с определенной функцией.

Совместный поиск и нахождение обозначенных функций в новых сказках (на протяжении одного занятия используется 3-5 карт).

Самостоятельный поиск функций детьми на материале знакомых, затем новых сказок.

Целостное освоение сказочных функций (используется весь комплект карт).

Сочинение сказок (сначала коллективно и используя ограниченный набор карт, постепенно добавляя по 3 — 4 карты).

Работа с индивидуальным набором карт (вначале детям можно предлагать готовое название сказки, оговорить только место действия, количество персонажей). А вот, как вы это обозначите ту или иную функцию, и каким символом, совсем не важно, главное, чтобы ребенок понимал, что если «запрет» обозначается перечеркнутый круг или замок на двери или как в знаках дорожного движения — въезд запрещен, то это надо запомнить. Или знак «даритель, волшебный дар»- можно волшебной палочкой обозначить, можно, как коробка с подарком, это, как решит воспитатель.

Слайд 19 Результат:

– умение определять жанр произведения;

– запоминать последовательность событий;

– выделять основное содержание сказки;

– выстраивать схему содержания, опираясь, на карты Проппа;

– уверенно манипулировать картами;

– чувствовать красоту и образность родного языка.