Всё, о чём мы не задумываемся, кажется нам простым. Вот, например, цифры. Математика ещё может быть сложной, а цифры – это просто значки, которые обозначают числа от нуля до девяти. Нам кажется, что по-другому и быть не может! Но многие цивилизации считали иначе.

Двойная жизнь букв алфавита

У некоторых народов роль цифр традиционно исполняли буквы, каждая из которых обозначает или единицы, или десятки, или сотни и тысячи.

Например, у древних евреев

У древних греков

У средневековых арабов – абджадия

У древних армян

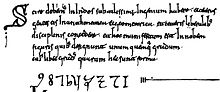

Немного тут отличилась допетровская Русь и эфиопы; чтобы показать, что буквы надо читать именно как цифры, к ним присоединялся специальный значок. У русских он назывался “титло”:

У эфиопов

У русских

Во всех этих системах записи чисел нет нуля, а многими из них нельзя записать числа больше 999. Насколько ими было удобно пользоваться для исчисления, говорит тот факт, что греческие математики записывали своими цифрами только “дано” и “ответ”, а решение выполняли пользуясь вавилонской клинописной системой. ВАВИЛОНСКОЙ КЛИНОПИСНОЙ СИСТЕМОЙ. Иначе было легче придумать новое философское учение, чем решить что-то сложнее, чем пятью пять.

Весёлые картинки древних египтян

У соплеменников Тутанхамона и Нефертити было очень развитое иероглифическое письмо – того требовала не менее развитая бюрократия, однако и они не стали выделять отдельных значков под цифры. Единица обозначалась тем же иероглифом, что черта, десятка – пяткой, сотня – петлёй верёвки, тысяча – лотосом. А вот десять тысяч для европейца особенно неожиданны, потому что именно эту часть тела мы ассоциируем с жалкими единицами – палец! Сто тысяч обозначались жабой, а вот значок миллиона был уникальным. Он изображал мужчину, преклонившего колено и поднявшего руки, как бы в потрясении перед таким числом. Хотя, если вдуматься, миллион – это ведь всего лишь сто жаб или тысяча пальцев.

Сложные числа обозначались просто: значок единицы, десятка, сотни и так далее повторялся нужное количество раз, поэтому некоторые числа выглядят утомительно длинными. Да, нуля египтяне тоже не знали, но, в отличие от греков, справлялись с вычислениями как-нибудь так. С другой стороны, им было намного легче: ведь проще сложить три пальца две пятки и жабу пять лотосов, расставив их в нужном порядке вместе, чем НБ (ню бета) с ТОД (тау омикрон дельта).

Смайлики от майя

А вот у майя было целых два способа записывать цифры. Наверное, для скучных людей и для весёлых. В системе для скучных ноль записывался ракушкой, единица – точкой, пятёрка – линией, и этих трёх значков хватало для обозначения любого числа. Тем более, что записывались числа примерно по тому же принципу, что у нас, только система была не десятеричной, а двадцатеричной. То есть, запись точка и ракушка (10) означала наши двадцать (20). А настоящая десять записывалась как две черты (5 и 5).

Второй способ записывать числа – иероглифы в виде голов, каждая из которых обозначает числа от 0 до 19. Причём эта система была наполовину десятеричной: начиная с 11, голова имеет чёткую приставную челюсть, как у 10.

Очевидно, для вычислений использовался первый тип записи, как более наглядный, а головоцифры были только для каллиграфии по камню. Почти как с греками, только возле майя не было своих вавилонцев, чьи цифры можно было бы использовать для математических операций, и им пришлось стать самим себе вавилонцами.

Вавилонская клинопись

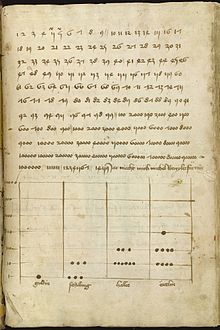

Вавилоняне пользовались шестидесятеричной системой счисления, но внутри каждой шестидесятки она, судя по способу записи, была обычной десятеричной. Вавилоняне пользовались нулём, хотя не рассматривали его как отдельное число. Что касается непосредственно записи чисел, то от её вида немедленно начинает рябить в глазах. Мы считаем, за такой неприятный эффект вавилонские математики должны были получать молоко, а лучше пиво, потому что иначе остаться в своём уме, целый день наблюдая ЭТО, невозможно:

Древние римляне: пятёрки и десятки

На первый взгляд, древние римляне так же, как греки, пользовались алфавитной записью чисел. На самом деле, они использовали только некоторые буквы для условного обозначения единиц и пятёрок в десятеричных разрядах. К слову, изначально часть этих цифробукв к буквам отношения не имели, это были похожие на римские буквы этрусские значки, условно обозначающие палец (I – единица), ладонь (V – пятёрка, только у этрусков она была углом кверху) и две ладони рядом (X – десять). Римляне также пользовались для обозначения чисел буквами L (50, пять десятков), C (100), D (500, пять сотен) и M (1000). Большие числа обозначали, ставя наверху буквы черту, означавшую умножение на 1000. Так, 5000 – это V (5) с чертой, 10 000 – X (10) с чертой, и так далее. 2015 год древний римлянин обозначил бы вот так: MMXV (1000+1000+10+5). При таком способе записей отдельная буквоцифра для нуля не нужна, так что и самого нуля как числа римляне не знали.

Инки: узелки на память

У инков было два типа письменности. Классическая, узелками (“кипу”) и двумерная, в виде записей на пергаменте, листьях и даже орнаментов на одежде (“килька”). Кипу имела несколько видов сложности. Числовой записью узелками владели все взрослые инки. Простым письмом владели образованные люди (например, чиновники – инки были очень бюрократической империей), и письмом сложным, необходимым для подробных и детальных записей – только учёные и хронисты. Килька по умолчанию считалась элитным видом письменности, простым людям запрещено было ею пользоваться. Числа, как и слова, в кипу обозначались узелками определённой формы. Учёные утверждают, что инки пользовались десятеричной системой счисления и записывали числа, как мы показываем их на счётах – только вместо рядов костяшек были ряды узлов. Надо сказать, европейские цифры инки выучивали от испанцев на раз, находили их такими простыми, что аж скучно и глупо, и откровенно высмеивали. В ответ оскорблённые испанцы занимались систематическим уничтожением кипу. Так пропали многие бесценные исторические хроники. К слову, инки были первым народом, который использовал двойной счёт в бухгалтерии (записывали дебет с кредитом). Для вычислений они использовали специфический вид счёт, юпану. Некоторые современные учёные полагают, что юпана работала на фибоначчиевой системе счисления, изобретённой инками, конечно же, задолго до Фибоначчи.

Слайд 1

ОБОЗНАЧЕНИЕ ЦИФР У разных народов Выполнила: ученица 5 «а»класса Скурихина Милана Руководитель: Калачева С.Ю. 2019 год

Слайд 2

Введение. ГИПОТЕЗА: Знакомые нам цифры и числа не всегда существовали в том виде, в котором мы их знаем. ОБЪЕКТ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ: Цифры разных народов в разные времена.

Слайд 3

Актуальность работы: С самого раннего возраста человек сталкивается с необходимостью считать. Однако, научившись считать, люди мало знают о том, откуда появились цифры, кто придумал использовать ту или иную форму записи числа, поэтому я решила расширить свой кругозор по этой теме и рассказать об этом одноклассникам.

Слайд 4

Цель: Изучить причины возникновения и способы записи цифр в разные времена Задачи: Совершить небольшой экскурс в историю происхождения цифр разных народов; Научиться с помощью цифр и чисел народов обозначать количество; Познакомить одноклассников с цифрами и записью народов мира.

Слайд 5

Обозначение чисел в Южной Америке. Система Майя включала позиционность и нуль . Оба этих понятия были полностью неизвестны европейцам в это время. Первые девятнадцать чисел системы счисления были представлены точками и черточками, согласно следующей таблице: Нуль записывался как символ, похожий на раковину (домик улитки). Многозначные числа большие 19 , записывались вертикально, начиная с единиц высшего разряда сверху вниз.

Слайд 7

Обозначение чисел в Египте. Первые написанные цифры, о которых мы имеем достоверные свидетельства, появились в Египте и Месопотамии около 5000 лет назад. Хотя эти две культуры находились очень далеко одна от другой, их числовые системы очень похожи: использование засечек на дереве или камне для записи прошедших дней. Египетские жрецы писали на папирусе, изготовленном из стеблей определенных сортов тростника, а в Месопотамии на мягкой глине. В египетской системе цифрами являлись иероглифические символы; они обозначали числа 1, 10, 100 и т. д. до миллиона.

Слайд 8

Египетская нумерация 1. Как и большинство людей для счета небольшого количества предметов Египтяне использовали палочки. Если палочек нужно изобразить несколько, то их изображали в два ряда, причем в нижнем должно быть столько же палочек сколько и в верхнем, или на одну больше. 10. Такими путами египтяне связывали коров Если нужно изобразить несколько десятков, то иероглиф повторяли нужное количество раз. Тоже самое относится и к остальным иероглифам. 100. Это мерная веревка, которой измеряли земельные участки после разлива Нила. 1 000. Вы когда-нибудь видели цветущий лотос? Если нет, то вам никогда не понять, почему Египтяне присвоили такое значение изображению этого цветка. 10 000. «В больших числах будь внимателен!» — говорит поднятый вверх указательный палец. 100 000. Это головастик. Обычный лягушачий головастик. 1 000 000. Увидев такое число обычный человек очень удивится и возденет руки к небу. Это и изображает этот иероглиф 10 000 000. Египтяне поклонялись Амону Ра, богу Солнца, и, наверное, поэтому самое большое свое число они изобразили в виде восходящего солнца

Слайд 9

Обозначение чисел в Вавилоне В древнем Вавилоне примерно за 40 веков до нашего времени создалась позиционная нумерация , то есть такой способ записи чисел, при котором одна и та же цифра может обозначать разные числа, смотря по месту, занимаемому этой цифрой.

Слайд 10

Вавилонская нумерация В вавилонской поместной нумерации ту роль, которую у нас играет число 10, играет число 60, и потому эту нумерацию называют шестидесятиричной. Числа менее 60 обозначались с помощью двух знаков для единицы, и для десятка

Слайд 11

Вавилонскую систему мы считаем лишь относительно позиционной, ибо самый правый знак мог означать либо единицы, либо кратные какой-нибудь степени числа 60 . Тем не менее изобретение вавилонянами позиционной системы счисления с нулем представляло собой огромное достижение, по своему революционному значению для математики сопоставимое разве лишь с более поздней гипотезой Коперника в астрономии.

Слайд 12

Обозначение чисел у арабов. До хиджры арабы записывали числа словами, но затем, как это делали ранее греки, они стали обозначать числа буквами своего алфавита. В 772 индийский трактат «Сидданта» был привезен в Багдад и переведен на арабский, после чего стали использоваться две системы записи чисел: 1. В астрономии по-прежнему употребляли алфавитную систему, 2. В торговых расчетах купцы стали применять систему, заимствованную из Индии. Но даже среди тех, кто пользовался индийской системой, начертания цифр, как и в Индии, сильно варьировали

Слайд 13

Из арабского языка заимствовано и слово «цифра» (по-арабски «сыфр»), означающее буквально «пустое место» (перевод санскритского слова «сунья», имеющего тот же смысл). Это слово применялось для названия знака пустого разряда, и этот смысл сохраняло до XVIII века, хотя еще в XV веке появился латинский термин «нуль» (nullum — ничто).

Слайд 14

Обозначение чисел у римлян. Древние римляне изобрели систему исчисление, основанную на использовании букв для отображения цифр. Каждая буква имела различное значение, каждая цифра соответствовала номеру положения буквы. Для того чтобы прочесть римскую цифру, следует следовать пяти основным правилам: Буквы пишутся слева направо, начиная с самого большого значения. Например: X V (15), CCXLIII (243), ZCXV (2115). Буквы I, X, C и M могут повторяться до трёх раз подряд, например: III (3), XX (20), ССC (300), MCCXXX (1320). Буквы V, L, D не могут повторяться. Цифры 6, 8, 40, 80, 800 следует писать, комбинируя буквы: VII (6), VIII (8), XL (40), LXXX (80), CD (400), DCCC (800). Например, 48 следует писать, комбинируя буквы XLVIII, 449 – CDXLIX _ Горизонтальная линия над буквой увеличивает её значение в 1000 раз.

Слайд 15

Латинская (Римская) нумерация I 1 V 5 X 10 L 50 C 100 D 500 M 1 000 Возникла эта нумерация в древнем Риме. Использовалась она для аддитивной алфавитной системы счисления

Слайд 16

Славянская кириллическая нумерация

Слайд 17

Читаем дословно «четырнадцать» — «четыре на десять». Как слышим, так и пишем: не 10+4, а 4+10, — четыре на десять. И так для всех чисел от 11 до 19. Таким образом у славян мы прослеживаем десятеричную систему счисления. Запись числа, использованная славянами аддитивная, то есть в ней используется только сложение: 800+60+3

Слайд 18

Обозначение чисел у китайцев. Эта нумерация одна из старейших и самых прогрессивных, поскольку в нее заложены такие же принципы, как и в современную арабскую, которой мы с Вами пользуемся. Возникла эта нумерация около 4 000 тысяч лет тому назад в Китае.

Слайд 19

10 100 100 1 000; 548 Такая запись числа мультипликативна, то есть в ней используется умножение: 10+8 100+4 1 000 и 5 1

Слайд 20

Вавилонская нумерация В вавилонской поместной нумерации ту роль, которую у нас играет число 10, играет число 60, и потому эту нумерацию называют шестидесятиричной. Числа менее 60 обозначались с помощью двух знаков для единицы, и для десятка

Слайд 21

Число-это сложная, но очень интересная загадка. Итак, наиболее древними являются вавилонские и египетские цифры. Записи чисел были громоздкими, и лишь с изобретением позиционной системы счисления запись и вычисления упростились.

Слайд 22

Вывод: Проведенное мною исследование не исчерпывает всех аспектов истории возникновения цифр, но поиск и обобщение информации, позволяющее раскрыть данную тему, а также подбор интересных фактов расширили мой кругозор, усилили мотивацию изучения предмета.

Слайд 23

Числа Древней Руси Римские числа

Слайд 24

Древнеегипетские обозначения Вавилонская система счисления

Слайд 25

Обозначение чисел.

Arabic numerals are the ten symbols most commonly used to write decimal numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as computer symbols, trademarks, or license plates. The term often implies a decimal number, in particular when contrasted with Roman numerals.

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals, Hindu-Arabic numerals,[1] Western digits, Latin digits, or European digits.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary differentiates them with the fully capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[3] The term numbers or numerals or digits often implies only these symbols, however this can only be inferred from context.

Europeans learned of Arabic numerals about the 10th century, though their spread was a gradual process. Two centuries later, in the Algerian city of Béjaïa, the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, and have become common in the writing systems where other numeral systems existed previously, such as Chinese and Japanese numerals.

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

Evolution of Indian numerals into Arabic numerals and their adoption in Europe

The reason the digits are more commonly known as «Arabic numerals» in Europe and the Americas is that they were introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, who were then using the digits from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of Arabic Peninsula, Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or «Mashriki» numerals: ٠ ١ ٢ ٣ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ٨ ٩[a][4]

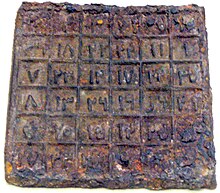

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early 11th century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[5] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 CE. They show three forms of the numeral «2» and two forms of the numeral «3», and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[6] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the 10th century onward.[7] Some amount of consistency in the Western Arabic numeral forms endured from the 10th century, found in a Latin manuscript of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae from 976 and the Gerbertian abacus, into the 12th and 13th centuries, in early manuscripts of translations from the city of Toledo.[4]

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, «calculation with dust»).[8] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār («dust figures») or qalam al-ghubår («dust letters»).[9] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper «without board and erasing» (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[10]

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but no evidence exists of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[11]

Adoption and spread[edit]

The first mentions of the numerals from 1 to 9 in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus of 976, an illuminated collection of various historical documents covering a period from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania.[12] Other texts show that numbers from 1 to 9 were occasionally supplemented by a placeholder known as sipos, represented as a circle or wheel, reminiscent of the eventual symbol for zero. The Arabic term for zero is sifr (صفر), transliterated into Latin as cifra, and the origin of the English word cipher.

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[12]

The reception of Arabic numerals in the West was gradual and lukewarm, as other numeral systems circulated in addition to the older Roman numbers. As a discipline, the first to adopt Arabic numerals as part of their own writings were astronomers and astrologists, evidenced from manuscripts surviving from mid-12th-century Bavaria. Reinher of Paderborn (1140–1190) used the numerals in his calendrical tables to calculate the dates of Easter more easily in his text Compotus emendatus.[13]

Italy[edit]

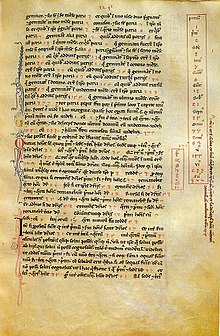

A page of the Liber Abaci. The list on the right shows the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377. The 2, 8, and 9 resemble Arabic numerals more than Eastern Arabic numerals or Indian numerals

Fibonacci, a mathematician from the Republic of Pisa who had studied in Béjaïa (Bugia), Algeria, promoted the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians’ nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

The Liber Abaci introduced the huge advantages of a positional numeric system, and was widely influential. As Fibonacci used the symbols from Béjaïa for the digits, these symbols were also introduced in the same instruction, ultimately leading to their widespread adoption.[14]

Fibonacci’s introduction coincided with Europe’s commercial revolution of the 12th and 13th centuries, centered in Italy. Positional notation could be used for quicker and more complex mathematical operations (such as currency conversion) than Roman and other numeric systems could. They could also handle larger numbers, did not require a separate reckoning tool, and allowed the user to check a calculation without repeating the entire procedure.[14] Although positional notation opened possibilities that were hampered by previous systems, late medieval Italian merchants did not stop using Roman numerals (or other reckoning tools). Rather, Arabic numerals became an additional tool that could be used alongside others.[14]

Europe[edit]

A German manuscript page teaching use of Arabic numerals (Talhoffer Thott, 1459). At this time, knowledge of the numerals was still widely seen as esoteric, and Talhoffer presents them with the Hebrew alphabet and astrology.

In the late 14th century only a few texts using Arabic numerals appeared outside of Italy. This suggests that the use of Arabic numerals in commercial practice, and the significant advantage they conferred, remained a virtual Italian monopoly until the late 15th century.[14] This may in part have been due to language – although Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci was written in Latin, the Italian abacus traditions was predominantly written in Italian vernaculars that circulated in the private collections of abacus schools or individuals. It was likely difficult for non-Italian merchant bankers to access comprehensive information.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Their use grew steadily in other centers of finance and trade such as Lyon.[15] Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[16] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[17] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[18]

By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe. Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of Anno Domini years, and for numbers on clock faces.[citation needed] Other digits (such as Eastern Arabic) were virtually unknown.[citation needed]

Russia[edit]

Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals, Cyrillic numerals, derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, were used by South and East Slavic peoples. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century, although it was formally replaced in official use by Peter the Great in 1699.[19] Reasons for Peter’s switch from the alphanumerical system are believed to go beyond his desire to imitate the West. Historian Peter Brown makes arguments for sociological, militaristic, and pedagogical reasons for the change. At a broad, societal level, Russian merchants, soldiers, and officials increasingly came into contact with counterparts from the West and became familiar with the communal use of Arabic numerals. Peter the Great also travelled incognito throughout Northern Europe from 1697 to 1698 during his Grand Embassy and was likely exposed to Western mathematics, if informally, during this time.[20] The Cyrillic numeric system was also inferior in terms of calculating properties of objects in motions, such as the trajectories and parabolic flight patterns of artillery. It was unable to keep pace with Arabic numerals in the growing science of ballistics, whereas Western mathematicians such as John Napier had been publishing on the topic since 1614.[21]

China[edit]

Chinese numeral systems that used positional notation (such as the counting rod system and Suzhou numerals) were in use in China preior to the introduction of Arabic numerals,[22][23] and some were introduced to medieval China by the Muslim Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[24][25][26]

Encoding[edit]

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code.

They are encoded in ASCII at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking to the lower four binary bits (or taking the last hexadecimal digit) gives the value of the digit, a great help in converting text to numbers on early computers. These positions were inherited in Unicode.[27] EBCDIC used different values, but also had the lower 4 bits equal to the digit value.

| ASCII Binary | ASCII Octal | ASCII Decimal | ASCII Hex | Unicode | EBCDIC Hex |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 1 | 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 2 | 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 3 | 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 4 | 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 5 | 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 6 | 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 7 | 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 8 | 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 9 | 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison with other digits[edit]

| Symbol | Used with scripts | Numerals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | many | Arabic numerals |

| 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 | Brahmi | Brahmi numerals |

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ | Devanagari | Devanagari numerals |

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | Bengali–Assamese | Bengali numerals |

| ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | Gurmukhi | Gurmukhi numerals |

| ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | Gujarati | Gujarati numerals |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ | Odia | Odia numerals |

| ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ | Santali | Santali numerals |

| 𑇐 | 𑇑 | 𑇒 | 𑇓 | 𑇔 | 𑇕 | 𑇖 | 𑇗 | 𑇘 | 𑇙 | Sharada | Sharada numerals |

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | Tamil | Tamil numerals |

| ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ | Telugu | Telugu script § Numerals |

| ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ | Kannada | Kannada script § Numerals |

| ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ | Malayalam | Malayalam numerals |

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | Sinhala | Sinhala numerals |

| ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | Burmese | Burmese numerals |

| ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | Tibetan | Tibetan numerals |

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | Mongolian | Mongolian numerals |

| ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ | Khmer | Khmer numerals |

| ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ | Thai | Thai numerals |

| ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ | Lao | Lao script § Numerals |

| ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ | Sundanese | Sundanese numerals |

| ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | Javanese | Javanese numerals |

| ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ | Balinese | Balinese numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Arabic | Eastern Arabic numerals |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Persian / Dari / Pashto | |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Urdu / Shahmukhi | |

| — | ፩ | ፪ | ፫ | ፬ | ፭ | ፮ | ፯ | ፰ | ፱ | Ethio-Semitic | Ge’ez numerals |

| 〇 | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | East Asia | Chinese numerals |

See also[edit]

- Arabic numeral variations

- Regional variations in modern handwritten Arabic numerals

- Seven-segment display

- Text figures

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Shown right-to-left, zero is on the right, nine on the left.

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Arabic numeral». American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Terminology for Digits Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Unicode Consortium.

- ^ «Arabic», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles (2002). Dold-Samplonius, Yvonne; Van Dalen, Benno; Dauben, Joseph; Folkerts, Menso (eds.). From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-3-515-08223-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 7: «Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n’ont pas été d’accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d’entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit.»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 12–13: «While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the 10th century onward…»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- ^ a b Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (3 May 2020). «Medieval Europe’s satanic ciphers: on the genesis of a modern myth». British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 35 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/26375451.2020.1726050. ISSN 2637-5451. S2CID 213113566.

- ^ Herold, Werner (2005). «Der «computus emendatus» des Reinher von Paderborn». ixtheo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Danna, Raffaele (12 July 2021). The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Arithmetic: a Socio-Economic Perspective (13th–16th centuries) (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.72497. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Danna, Raffaele; Iori, Martina; Mina, Andrea (22 June 2022). «A Numerical Revolution: The Diffusion of Practical Mathematics and the Growth of Pre-modern European Economies». SSRN 4143442.

- ^ «14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed». ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- ^ Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918.

- ^ Conatser Segura, Sylvia (26 May 2020). Orthographic Reform and Language Planning in Russian History (Honors thesis). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Brown, Peter B. (2012). «Muscovite Arithmetic in Seventeenth-Century Russian Civilization: Is It Not Time to Discard the «Backwardness» Label?». Russian History. 39 (4): 393–459. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904001. ISSN 0094-288X. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Lockwood, E. H. (October 1978). «Mathematical discoveries 1600-1750, by P. L. Griffiths. Pp 121. £2·75. 1977. ISBN 0 7223 1006 4 (Stockwell)». The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 219. doi:10.2307/3616704. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3616704. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Shell-Gellasch, Amy (2015). Algebra in context : introductory algebra from origins to applications. J. B. Thoo. Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1728-8. OCLC 907657424.

- ^ Uy, Frederick L. (January 2003). «The Chinese Numeration System and Place Value». Teaching Children Mathematics. 9 (5): 243–247. doi:10.5951/tcm.9.5.0243. ISSN 1073-5836. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0» (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003). «The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered». In J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Burnett, Charles (2006). «The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin». Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer-Netherlands. 34 (1–2): 15–30. doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z. S2CID 170783929.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995). The Bakhshālī Manuscript: An Ancient Indian Mathematical Treatise. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten. ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000). A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691114859.

- «Mathematics in South Asia». Nature. 189 (4761): 273. 1961. Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273.. doi:10.1038/189273c0. S2CID 4288165.

- Ore, Oystein (1988). «Hindu-Arabic numerals». Number Theory and Its History. Dover. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0486656209.

External links[edit]

- Lam Lay Yong, «Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic», Chinese Science 13 (1996): 35–54.

- «Counting Systems and Numerals», Historyworld. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O’Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson, Indian numerals Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. November 2000.

- History of the numerals

- Arabic numerals

- Hindu-Arabic numerals

- Numeral & Numbers’ history and curiosities

- Gerbert d’Aurillac’s early use of Hindu-Arabic numerals at Convergence

Arabic numerals are the ten symbols most commonly used to write decimal numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as computer symbols, trademarks, or license plates. The term often implies a decimal number, in particular when contrasted with Roman numerals.

They are also called Western Arabic numerals, Ghubār numerals, Hindu-Arabic numerals,[1] Western digits, Latin digits, or European digits.[2] The Oxford English Dictionary differentiates them with the fully capitalized Arabic Numerals to refer to the Eastern digits.[3] The term numbers or numerals or digits often implies only these symbols, however this can only be inferred from context.

Europeans learned of Arabic numerals about the 10th century, though their spread was a gradual process. Two centuries later, in the Algerian city of Béjaïa, the Italian scholar Fibonacci first encountered the numerals; his work was crucial in making them known throughout Europe. European trade, books, and colonialism helped popularize the adoption of Arabic numerals around the world. The numerals have found worldwide use significantly beyond the contemporary spread of the Latin alphabet, and have become common in the writing systems where other numeral systems existed previously, such as Chinese and Japanese numerals.

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

Evolution of Indian numerals into Arabic numerals and their adoption in Europe

The reason the digits are more commonly known as «Arabic numerals» in Europe and the Americas is that they were introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Arabic speakers of Spain and North Africa, who were then using the digits from Libya to Morocco. In the eastern part of Arabic Peninsula, Arabs were using the Eastern Arabic numerals or «Mashriki» numerals: ٠ ١ ٢ ٣ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ٨ ٩[a][4]

Al-Nasawi wrote in the early 11th century that mathematicians had not agreed on the form of the numerals, but most of them had agreed to train themselves with the forms now known as Eastern Arabic numerals.[5] The oldest specimens of the written numerals available are from Egypt and date to 873–874 CE. They show three forms of the numeral «2» and two forms of the numeral «3», and these variations indicate the divergence between what later became known as the Eastern Arabic numerals and the Western Arabic numerals.[6] The Western Arabic numerals came to be used in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus from the 10th century onward.[7] Some amount of consistency in the Western Arabic numeral forms endured from the 10th century, found in a Latin manuscript of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae from 976 and the Gerbertian abacus, into the 12th and 13th centuries, in early manuscripts of translations from the city of Toledo.[4]

Calculations were originally performed using a dust board (takht, Latin: tabula), which involved writing symbols with a stylus and erasing them. The use of the dust board appears to have introduced a divergence in terminology as well: whereas the Hindu reckoning was called ḥisāb al-hindī in the east, it was called ḥisāb al-ghubār in the west (literally, «calculation with dust»).[8] The numerals themselves were referred to in the west as ashkāl al‐ghubār («dust figures») or qalam al-ghubår («dust letters»).[9] Al-Uqlidisi later invented a system of calculations with ink and paper «without board and erasing» (bi-ghayr takht wa-lā maḥw bal bi-dawāt wa-qirṭās).[10]

A popular myth claims that the symbols were designed to indicate their numeric value through the number of angles they contained, but no evidence exists of this, and the myth is difficult to reconcile with any digits past 4.[11]

Adoption and spread[edit]

The first mentions of the numerals from 1 to 9 in the West are found in the Codex Vigilanus of 976, an illuminated collection of various historical documents covering a period from antiquity to the 10th century in Hispania.[12] Other texts show that numbers from 1 to 9 were occasionally supplemented by a placeholder known as sipos, represented as a circle or wheel, reminiscent of the eventual symbol for zero. The Arabic term for zero is sifr (صفر), transliterated into Latin as cifra, and the origin of the English word cipher.

From the 980s, Gerbert of Aurillac (later, Pope Sylvester II) used his position to spread knowledge of the numerals in Europe. Gerbert studied in Barcelona in his youth. He was known to have requested mathematical treatises concerning the astrolabe from Lupitus of Barcelona after he had returned to France.[12]

The reception of Arabic numerals in the West was gradual and lukewarm, as other numeral systems circulated in addition to the older Roman numbers. As a discipline, the first to adopt Arabic numerals as part of their own writings were astronomers and astrologists, evidenced from manuscripts surviving from mid-12th-century Bavaria. Reinher of Paderborn (1140–1190) used the numerals in his calendrical tables to calculate the dates of Easter more easily in his text Compotus emendatus.[13]

Italy[edit]

A page of the Liber Abaci. The list on the right shows the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377. The 2, 8, and 9 resemble Arabic numerals more than Eastern Arabic numerals or Indian numerals

Fibonacci, a mathematician from the Republic of Pisa who had studied in Béjaïa (Bugia), Algeria, promoted the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Europe with his 1202 book Liber Abaci:

When my father, who had been appointed by his country as public notary in the customs at Bugia acting for the Pisan merchants going there, was in charge, he summoned me to him while I was still a child, and having an eye to usefulness and future convenience, desired me to stay there and receive instruction in the school of accounting. There, when I had been introduced to the art of the Indians’ nine symbols through remarkable teaching, knowledge of the art very soon pleased me above all else and I came to understand it.

The Liber Abaci introduced the huge advantages of a positional numeric system, and was widely influential. As Fibonacci used the symbols from Béjaïa for the digits, these symbols were also introduced in the same instruction, ultimately leading to their widespread adoption.[14]

Fibonacci’s introduction coincided with Europe’s commercial revolution of the 12th and 13th centuries, centered in Italy. Positional notation could be used for quicker and more complex mathematical operations (such as currency conversion) than Roman and other numeric systems could. They could also handle larger numbers, did not require a separate reckoning tool, and allowed the user to check a calculation without repeating the entire procedure.[14] Although positional notation opened possibilities that were hampered by previous systems, late medieval Italian merchants did not stop using Roman numerals (or other reckoning tools). Rather, Arabic numerals became an additional tool that could be used alongside others.[14]

Europe[edit]

A German manuscript page teaching use of Arabic numerals (Talhoffer Thott, 1459). At this time, knowledge of the numerals was still widely seen as esoteric, and Talhoffer presents them with the Hebrew alphabet and astrology.

In the late 14th century only a few texts using Arabic numerals appeared outside of Italy. This suggests that the use of Arabic numerals in commercial practice, and the significant advantage they conferred, remained a virtual Italian monopoly until the late 15th century.[14] This may in part have been due to language – although Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci was written in Latin, the Italian abacus traditions was predominantly written in Italian vernaculars that circulated in the private collections of abacus schools or individuals. It was likely difficult for non-Italian merchant bankers to access comprehensive information.

The European acceptance of the numerals was accelerated by the invention of the printing press, and they became widely known during the 15th century. Their use grew steadily in other centers of finance and trade such as Lyon.[15] Early evidence of their use in Britain includes: an equal hour horary quadrant from 1396,[16] in England, a 1445 inscription on the tower of Heathfield Church, Sussex; a 1448 inscription on a wooden lych-gate of Bray Church, Berkshire; and a 1487 inscription on the belfry door at Piddletrenthide church, Dorset; and in Scotland a 1470 inscription on the tomb of the first Earl of Huntly in Elgin Cathedral.[17] In central Europe, the King of Hungary Ladislaus the Posthumous, started the use of Arabic numerals, which appear for the first time in a royal document of 1456.[18]

By the mid-16th century, they were in common use in most of Europe. Roman numerals remained in use mostly for the notation of Anno Domini years, and for numbers on clock faces.[citation needed] Other digits (such as Eastern Arabic) were virtually unknown.[citation needed]

Russia[edit]

Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals, Cyrillic numerals, derived from the Cyrillic alphabet, were used by South and East Slavic peoples. The system was used in Russia as late as the early 18th century, although it was formally replaced in official use by Peter the Great in 1699.[19] Reasons for Peter’s switch from the alphanumerical system are believed to go beyond his desire to imitate the West. Historian Peter Brown makes arguments for sociological, militaristic, and pedagogical reasons for the change. At a broad, societal level, Russian merchants, soldiers, and officials increasingly came into contact with counterparts from the West and became familiar with the communal use of Arabic numerals. Peter the Great also travelled incognito throughout Northern Europe from 1697 to 1698 during his Grand Embassy and was likely exposed to Western mathematics, if informally, during this time.[20] The Cyrillic numeric system was also inferior in terms of calculating properties of objects in motions, such as the trajectories and parabolic flight patterns of artillery. It was unable to keep pace with Arabic numerals in the growing science of ballistics, whereas Western mathematicians such as John Napier had been publishing on the topic since 1614.[21]

China[edit]

Chinese numeral systems that used positional notation (such as the counting rod system and Suzhou numerals) were in use in China preior to the introduction of Arabic numerals,[22][23] and some were introduced to medieval China by the Muslim Hui people. In the early 17th century, European-style Arabic numerals were introduced by Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits.[24][25][26]

Encoding[edit]

The ten Arabic numerals are encoded in virtually every character set designed for electric, radio, and digital communication, such as Morse code.

They are encoded in ASCII at positions 0x30 to 0x39. Masking to the lower four binary bits (or taking the last hexadecimal digit) gives the value of the digit, a great help in converting text to numbers on early computers. These positions were inherited in Unicode.[27] EBCDIC used different values, but also had the lower 4 bits equal to the digit value.

| ASCII Binary | ASCII Octal | ASCII Decimal | ASCII Hex | Unicode | EBCDIC Hex |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0011 0000 | 060 | 48 | 30 | U+0030 DIGIT ZERO | F0 |

| 1 | 0011 0001 | 061 | 49 | 31 | U+0031 DIGIT ONE | F1 |

| 2 | 0011 0010 | 062 | 50 | 32 | U+0032 DIGIT TWO | F2 |

| 3 | 0011 0011 | 063 | 51 | 33 | U+0033 DIGIT THREE | F3 |

| 4 | 0011 0100 | 064 | 52 | 34 | U+0034 DIGIT FOUR | F4 |

| 5 | 0011 0101 | 065 | 53 | 35 | U+0035 DIGIT FIVE | F5 |

| 6 | 0011 0110 | 066 | 54 | 36 | U+0036 DIGIT SIX | F6 |

| 7 | 0011 0111 | 067 | 55 | 37 | U+0037 DIGIT SEVEN | F7 |

| 8 | 0011 1000 | 070 | 56 | 38 | U+0038 DIGIT EIGHT | F8 |

| 9 | 0011 1001 | 071 | 57 | 39 | U+0039 DIGIT NINE | F9 |

Comparison with other digits[edit]

| Symbol | Used with scripts | Numerals | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | many | Arabic numerals |

| 𑁦 | 𑁧 | 𑁨 | 𑁩 | 𑁪 | 𑁫 | 𑁬 | 𑁭 | 𑁮 | 𑁯 | Brahmi | Brahmi numerals |

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ | Devanagari | Devanagari numerals |

| ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ | Bengali–Assamese | Bengali numerals |

| ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ | Gurmukhi | Gurmukhi numerals |

| ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ | Gujarati | Gujarati numerals |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ | Odia | Odia numerals |

| ᱐ | ᱑ | ᱒ | ᱓ | ᱔ | ᱕ | ᱖ | ᱗ | ᱘ | ᱙ | Santali | Santali numerals |

| 𑇐 | 𑇑 | 𑇒 | 𑇓 | 𑇔 | 𑇕 | 𑇖 | 𑇗 | 𑇘 | 𑇙 | Sharada | Sharada numerals |

| ௦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ | Tamil | Tamil numerals |

| ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ | Telugu | Telugu script § Numerals |

| ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ | Kannada | Kannada script § Numerals |

| ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ | Malayalam | Malayalam numerals |

| ෦ | ෧ | ෨ | ෩ | ෪ | ෫ | ෬ | ෭ | ෮ | ෯ | Sinhala | Sinhala numerals |

| ၀ | ၁ | ၂ | ၃ | ၄ | ၅ | ၆ | ၇ | ၈ | ၉ | Burmese | Burmese numerals |

| ༠ | ༡ | ༢ | ༣ | ༤ | ༥ | ༦ | ༧ | ༨ | ༩ | Tibetan | Tibetan numerals |

| ᠐ | ᠑ | ᠒ | ᠓ | ᠔ | ᠕ | ᠖ | ᠗ | ᠘ | ᠙ | Mongolian | Mongolian numerals |

| ០ | ១ | ២ | ៣ | ៤ | ៥ | ៦ | ៧ | ៨ | ៩ | Khmer | Khmer numerals |

| ๐ | ๑ | ๒ | ๓ | ๔ | ๕ | ๖ | ๗ | ๘ | ๙ | Thai | Thai numerals |

| ໐ | ໑ | ໒ | ໓ | ໔ | ໕ | ໖ | ໗ | ໘ | ໙ | Lao | Lao script § Numerals |

| ᮰ | ᮱ | ᮲ | ᮳ | ᮴ | ᮵ | ᮶ | ᮷ | ᮸ | ᮹ | Sundanese | Sundanese numerals |

| ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | Javanese | Javanese numerals |

| ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ | Balinese | Balinese numerals |

| ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ | Arabic | Eastern Arabic numerals |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Persian / Dari / Pashto | |

| ۰ | ۱ | ۲ | ۳ | ۴ | ۵ | ۶ | ۷ | ۸ | ۹ | Urdu / Shahmukhi | |

| — | ፩ | ፪ | ፫ | ፬ | ፭ | ፮ | ፯ | ፰ | ፱ | Ethio-Semitic | Ge’ez numerals |

| 〇 | 一 | 二 | 三 | 四 | 五 | 六 | 七 | 八 | 九 | East Asia | Chinese numerals |

See also[edit]

- Arabic numeral variations

- Regional variations in modern handwritten Arabic numerals

- Seven-segment display

- Text figures

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Shown right-to-left, zero is on the right, nine on the left.

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Arabic numeral». American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2020. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Terminology for Digits Archived 26 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Unicode Consortium.

- ^ «Arabic», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles (2002). Dold-Samplonius, Yvonne; Van Dalen, Benno; Dauben, Joseph; Folkerts, Menso (eds.). From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 237–288. ISBN 978-3-515-08223-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 7: «Les personnes qui se sont occupées de la science du calcul n’ont pas été d’accord sur une partie des formes de ces neuf signes; mais la plupart d’entre elles sont convenues de les former comme il suit.»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 12–13: «While specimens of Western Arabic numerals from the early period—the tenth to thirteenth centuries—are still not available, we know at least that Hindu reckoning (called ḥisāb al-ghubār) was known in the West from the 10th century onward…»

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Kunitzsch 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Ifrah, Georges (1998). The universal history of numbers: from prehistory to the invention of the computer. Translated by David Bellos (from the French). London: Harvill Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9781860463242.

- ^ a b Nothaft, C. Philipp E. (3 May 2020). «Medieval Europe’s satanic ciphers: on the genesis of a modern myth». British Journal for the History of Mathematics. 35 (2): 107–136. doi:10.1080/26375451.2020.1726050. ISSN 2637-5451. S2CID 213113566.

- ^ Herold, Werner (2005). «Der «computus emendatus» des Reinher von Paderborn». ixtheo.de (in German). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Danna, Raffaele (12 July 2021). The Spread of Hindu-Arabic Numerals in the European Tradition of Practical Arithmetic: a Socio-Economic Perspective (13th–16th centuries) (Doctoral thesis). University of Cambridge. doi:10.17863/cam.72497. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Danna, Raffaele; Iori, Martina; Mina, Andrea (22 June 2022). «A Numerical Revolution: The Diffusion of Practical Mathematics and the Growth of Pre-modern European Economies». SSRN 4143442.

- ^ «14th century timepiece unearthed in Qld farm shed». ABC News. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ See G. F. Hill, The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, for more examples.

- ^ Erdélyi: Magyar művelődéstörténet 1-2. kötet. Kolozsvár, 1913, 1918.

- ^ Conatser Segura, Sylvia (26 May 2020). Orthographic Reform and Language Planning in Russian History (Honors thesis). Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Brown, Peter B. (2012). «Muscovite Arithmetic in Seventeenth-Century Russian Civilization: Is It Not Time to Discard the «Backwardness» Label?». Russian History. 39 (4): 393–459. doi:10.1163/48763316-03904001. ISSN 0094-288X. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Lockwood, E. H. (October 1978). «Mathematical discoveries 1600-1750, by P. L. Griffiths. Pp 121. £2·75. 1977. ISBN 0 7223 1006 4 (Stockwell)». The Mathematical Gazette. 62 (421): 219. doi:10.2307/3616704. ISSN 0025-5572. JSTOR 3616704. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Shell-Gellasch, Amy (2015). Algebra in context : introductory algebra from origins to applications. J. B. Thoo. Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-1728-8. OCLC 907657424.

- ^ Uy, Frederick L. (January 2003). «The Chinese Numeration System and Place Value». Teaching Children Mathematics. 9 (5): 243–247. doi:10.5951/tcm.9.5.0243. ISSN 1073-5836. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Helaine Selin, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Meuleman, Johan H. (2002). Islam in the era of globalization: Muslim attitudes towards modernity and identity. Psychology Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7007-1691-3. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ Peng Yoke Ho (2000). Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-486-41445-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 13.0» (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2001. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2003). «The Transmission of Hindu-Arabic Numerals Reconsidered». In J. P. Hogendijk; A. I. Sabra (eds.). The Enterprise of Science in Islam: New Perspectives. MIT Press. pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-0-262-19482-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Burnett, Charles (2006). «The Semantics of Indian Numerals in Arabic, Greek and Latin». Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer-Netherlands. 34 (1–2): 15–30. doi:10.1007/s10781-005-8153-z. S2CID 170783929.

- Hayashi, Takao (1995). The Bakhshālī Manuscript: An Ancient Indian Mathematical Treatise. Groningen, Netherlands: Egbert Forsten. ISBN 906980087X.

- Ifrah, Georges (2000). A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to Computers. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471393401.

- Katz, Victor J., ed. (20 July 2007). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691114859.

- «Mathematics in South Asia». Nature. 189 (4761): 273. 1961. Bibcode:1961Natur.189S.273.. doi:10.1038/189273c0. S2CID 4288165.

- Ore, Oystein (1988). «Hindu-Arabic numerals». Number Theory and Its History. Dover. pp. 19–24. ISBN 0486656209.

External links[edit]

- Lam Lay Yong, «Development of Hindu Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic», Chinese Science 13 (1996): 35–54.

- «Counting Systems and Numerals», Historyworld. Retrieved 11 December 2005.

- The Evolution of Numbers. 16 April 2005.

- O’Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson, Indian numerals Archived 6 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. November 2000.

- History of the numerals

- Arabic numerals

- Hindu-Arabic numerals

- Numeral & Numbers’ history and curiosities

- Gerbert d’Aurillac’s early use of Hindu-Arabic numerals at Convergence

Цифры и числа разных народов мира

- Авторы

- Руководители

- Файлы работы

- Наградные документы

Амирова А.Н. 1

1Муниципальное автономное общеобразовательное учреждение «Ухтинский технический лицей им. Г.В.Рассохина»

Фролова Г.А. 1

1Муниципальное автономное общеобразовательное учреждение «Ухтинский технический лицей им. Г.В.Рассохина»

Текст работы размещён без изображений и формул.

Полная версия работы доступна во вкладке «Файлы работы» в формате PDF

Введение.

Я нашла в одной из книг примеры с непонятными для меня числами. Я не смогла решить их. Мне захотелось узнать об этих числах. Когда я нашла литературу по данному вопросу оказалось, что непонятных мне цифр очень много и созданы они разными народами мира. Считать люди научились еще в незапамятные времена. Сначала люди просто различали один предмет перед ними или нет. Если предмет был не один, то говорили «много». Первыми понятиями математики были «меньше», «больше» и «столько же».

Я поставила перед собой цель:

изучение цифр и запись чисел разных народов мира.

Задачи:

1.Узнать об истории происхождения цифр и чисел разных народов мира;

2.Научиться с помощью цифр и чисел народов обозначать количество;

3.Познакомить одноклассников с цифрами и записью чисел народов мира;

4.Решить задачу, которая мне непонятна.

3

Основная часть.

Современному человеку трудно представить себе математику без обозначений чисел и арифметических действий. Тем не менее, когда-то этих обозначений не существовало. Древние культуры вообще были в большей степени ориентированы на устную речь, на устное обучение, чем современная. Постепенно люди сталкивались с необходимостью сооружать постройки, делить землю на участки, подсчитывать собранный урожай, вести календарь. Человек учился считать, выполнять действия над числами. Запоминать все вычисления становилось трудно и поэтому возникает необходимость в записи чисел. Цифры – условные знаки для обозначения чисел. Человечество выработало целый ряд различных систем записи чисел – различных нумераций.

Народы Древней Азии: при счете завязывали узелки на шнурках разной длины и цвета. Узелки называли вспоминателем.

Китай: люди, живущие в Китае придумали цифры на пальцах.

Так они могли показать числа и цифры. Например: указательный палец правой руки означает цифру 1, а если приставить на него указательный палец левой руки, то это будет число 10. А чтобы показать цифру 6 нужно загнуть три пальца. В древние времена люди ходили босиком. Поэтому они могли пользоваться для счета пальцами как рук, так и ног. Таким образом они могли, казалось бы, считать лишь до двадцати.

Но с помощью этой «босоногой машины» люди могли достигать значительно больших чисел, 1 человек — это 20, 2 человека — это два раза по 20 и т.д.

При письме китайцы обозначали цифры и числа иероглифами.

Записывались цифры, начиная с больших значений и заканчивая меньшими. Если десятков, единиц, или какого-то другого разряда не было, то сначала ничего не ставили и переходили к следующему разряду. (Во времена династии Мин был 4 введен знак для пустого разряда — кружок — аналог нашего нуля). Чтобы не перепутать разряды использовали несколько служебных иероглифов, писавшихся после основного иероглифа, и показывающих какое значение принимает иероглиф-цифра в данном разряде. Вот несколько служебных иероглифов:

|

100 |

1000 |

|

|

10 |

Цифры народов Майя:

1 вариант: древние индейцы вместо самих цифр рисовали страшные головы, как у пришельцев.

2 вариант: при письме о 1 до 4 цифры обозначались точками, а горизонтальная линия обозначала цифру 5.Остальные же цифры до 10 обозначались точками над цифрой 5. Овал, разделённый на 3 части обозначал число 20. А дальше происходило совсем интересное: овалы умножались на количество точек, поставленных над овалом. Например: овал, умноженный на две точки = 40, а на горизонтальную линию = 100 .

Египетские цифры: до нас дошли надписи, сохранившиеся внутри пирамид, на плитах и обелисках. Они состоят из картинок — иероглифов, которые изображают птиц, зверей, людей, части человеческого тела (глаза, ноги) и различные неодушевленные предметы.

5

|

1 |

Как и большинство людей для счета небольшого количества предметов Египтяне использовали палочки. |

|

|

5 |

Если палочек нужно изобразить несколько, то их изображали в два ряда, причем в нижнем должно быть столько же палочек, сколько и в верхнем, или на одну больше. |

|

|

10 |

Такими путами египтяне связывали коров. |

|

|

30 |

Если нужно изобразить несколько десятков, то иероглиф повторяли нужное количество раз. Тоже самое относится и к остальным иероглифам. |

|

|

100 |

Это мерная веревка, которой измеряли земельные участки после разлива Нила. |

|

|

1 000 |

Вы когда-нибудь видели цветущий лотос? Если нет, то вам никогда не понять, почему Египтяне присвоили такое значение изображению этого цветка. |

|

|

10 000 |

«В больших числах будь внимателен!» — говорит поднятый вверх указательный палец. |

|

|

100 000 |

Это головастик. Обычный лягушачий головастик. |

|

|

1 000 000 |

Увидев такое число обычный человек очень удивится и возденет руки к небу. Это и изображает этот иероглиф. |

|

|

10 000 000 |

Египтяне поклонялись Амону Ра, богу Солнца, и, наверное, поэтому самое большое свое число они изобразили в виде восходящего солнца. |

Египтяне придумали эту систему около 5 000 лет тому назад. Это одна из древнейших систем записи чисел, известная человеку.

Славянские цифры:

Алфавитная система была принята и в Древней Руси. Это форма записи чисел имела полное сходство с греческой. Славяне в качестве цифр использовали 6

буквы, но чтобы не перепутать буквы и цифры ставили над ней значок, который назывался – титло. Такая нумерация сохранялась при Иване Грозном и называлась цифирь, и была заимствована от средневековых греков – византийцев. Поэтому цифры обозначались только теми буквами, для которых были соответствия в греческом алфавите ( например ж и б не использовались для нумерации, их просто не было в греческом алфавите ). Для обозначения больших чисел славяне придумали свой оригинальный способ : 10 000 – тьма, 10 тем – легион, 10 легионов – леодр, 10 леодров – ворон, 10 воронов – колода.

|

(Тьма) |

(Легион) |

(Леодр) |

(Ворон) |

(Колода) |

Такой способ обозначения чисел был неудобен. Поэтому Пётр 1 ввел в России привычные для нас 10 цифр, которыми мы пользуемся до сих пор.

Вавилон:

В древнем Вавилоне записывали числа, выдавливая значки палочкой на глиняной дощечке. Все числа у них составлялись из сочетаний клинышков. Запись чисел в древнем Вавилоне назывались клинописью. В основе клинописи лежало не число 10, а число 60. Вавилонская шестидесятеричная система счисления оставила важный след в истории. Именно от вавилонян пошло деление окружности на 360 частей, которые мы сейчас называем градусами, а градусов (как и часов) – на 60 минут, которые, в свою очередь, делятся на 60 секунд.

Цифры древнего Рима: римская нумерация чисел сохранилась и до наших дней. Эти цифры знакомы всем, хотя им уже около 2,5 тысячелетий. 7

Они встречаются на циферблатах часов, фронтонах старинных и современных зданий, памятниках, страницах книг.

Запись чисел римскими цифрами менее удобна, чем общепринятая. Такая запись громоздка и требует значительно большего времени для написания, она осложняет выполнение письменных действий.

8

Заключение.

В работе рассмотрены условные знаки — цифры разных народов, представлены 7 различных нумераций. По каждой нумерации подобран иллюстративный материал, позволяющий обеспечить наглядность рассматриваемых систем записи чисел.

Материал данной работы можно рекомендовать к использованию на уроках математики или на занятиях школьного математического кружка в качестве дополнительного материала с целью появления заинтересованности к учебному предмету и пробуждения желания к изучению математики у учеников, а также для расширения их кругозора.

На уроке математики я предложила своим одноклассникам задания по римской и славянской нумерации (был предоставлен справочный материал).

Результаты на диаграмме:

И в ходе изучения различных записей цифр, я смогла решить задачу, которая мне была непонятна:

1)22 2)176 3)1002

9

Литература

1.Акимова С. Занимательная математика.–Тригон.–Санкт-Петербург, 1997

2.Я познаю мир: Детская энциклопедия: Математика/ Сост. А.П.Савин,

В.В. Станцо, А.Ю. Котова, М.: ООО «Фирма «Издательстово АСТ»,199-480с.

3.Шейнина О.С., Соловьева Г.М. Математика. Занятия школьного кружка.5-6 кл.–М.: Изд-во НЦ ЭНАС,2003.

4. Башмакова И.Г. Числа /Детская энциклопедия.–М.:Педагогика,1972.

5. http://files.school-collection.edu.ru

10

Просмотров работы: 18411