Ночной режим

Новинки

Пропавшая грамота

Красный цветок

Трусишка Вася (М. Зощенко)

Критики (В. Шукшин)

Отчего у верблюда горб (Р. Киплинг)

Стрижонок Скрип

Популярное

Сказка Гулливер в стране лилипутов — Джонатан Свифт

Сказка Чудесное путешествие Нильса с дикими гусями — Сельма Лагерлеф

Сказки про драконов

Миф о рождении Зевса

Домовёнок Кузя — Татьяна Александрова

Сказки про кошек

Сказки для детей любого возраста →

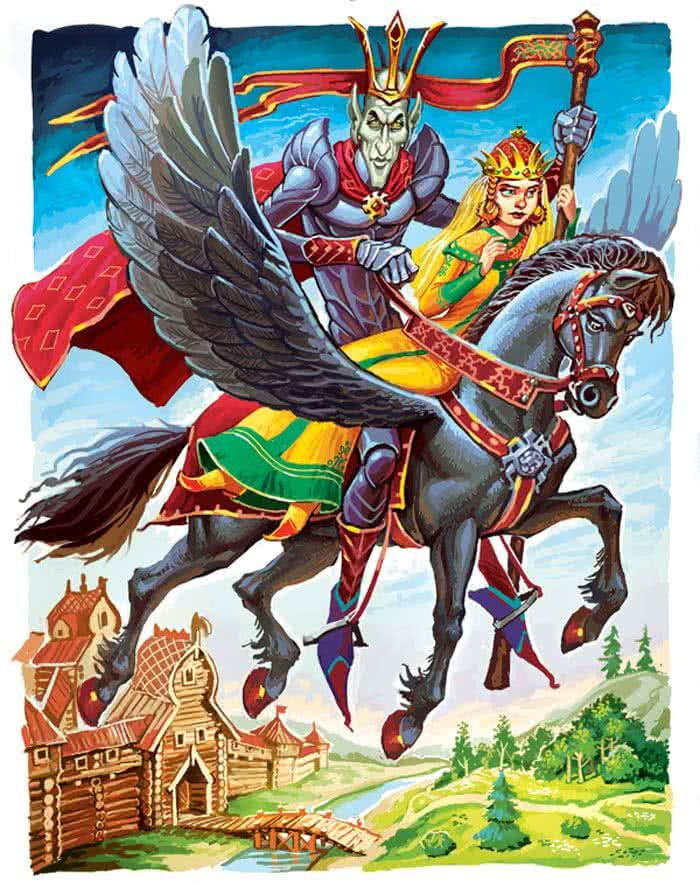

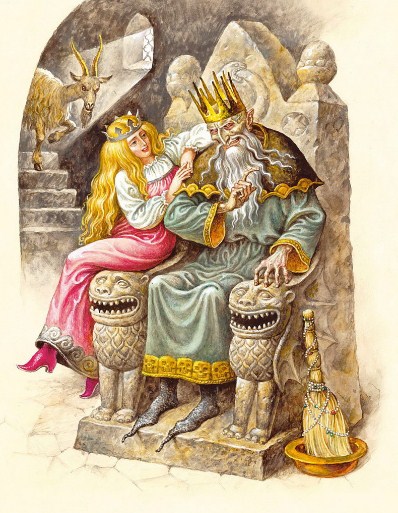

Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного

Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного

Иван Соснович

Пеппи Длинный чулок

Один из могущественных персонажей эпоса всех времен является Кощей Бессмертный, сказки про которого отличаются атмосферой, магией и его всесилием. Мы собрали в отличную подборку интересные сказки про Кощея, которые познакомят вашего ребенка с данным персонажем и его силами.

- Сказка Про славного царя Гороха;

- Сказка о царе Берендее, о сыне его Иване-царевиче, о хитростях Кощея Бессмертного и о премудрости Марьи-царевны, Кощеевой дочери;

- Царевна-лягушка;

- Марья Моревна;

- Руслан и Людмила;

- Иван Утреник;

- Булат-молодец;

- Сказка про чудную игру;

- Кощей-Бессмертный;

- Царевна-змея;

- День рождения Кощея;

- Иван Соснович.

Facebook

ВКонтакте

Комментарии

Рпапм

Абвнвочтвьяьчьвьчьвьчьвовововововововововрврврврврврвововоаалалал

10.10.2022

Ответить

Ночной режим

Категории

Аудиосказки для детей слушать онлайн

— Арабские аудиосказки

— Аудио повести для детей и подростков

— Аудио рассказы Виталия Бианки

— Аудиокниги Андрея Платонова

— Аудиокниги Аркадия Гайдара

— Аудиокниги Бориса Житкова

— Аудиокниги Драгунского

— Аудиокниги Марка Твена

— Аудиокниги Пришвина для детей

— Аудиосказки Аксакова

— Аудиосказки Александра Волкова

— Аудиосказки Андерсена

— Аудиосказки Андрея Усачева

— Аудиосказки Астрид Линдгрен

— Аудиосказки Бажова

— Аудиосказки братьев Гримм

— Аудиосказки Владимира Сутеева

— Аудиосказки Гаршина

— Аудиосказки Гауфа

— Аудиосказки Гофмана

— Аудиосказки Джанни Родари

— Аудиосказки Киплинга

— Аудиосказки Мамина-Сибиряка

— Аудиосказки Маршака

— Аудиосказки Михалкова

— Аудиосказки на ночь

— Аудиосказки Одоевского

— Аудиосказки Остера

— Аудиосказки по мультфильмам

— Аудиосказки Пушкина

— Аудиосказки Салтыкова-Щедрина

— Аудиосказки Толстого

— Аудиосказки Успенского

— Аудиосказки Чуковского

— Аудиосказки Шарля Перро

— Аудиосказки Шварца

— Аудиосказки Юрия Дружкова и Валентина Постникова

— Детская Библия

— Русские народные

— Сборник аудиосказок

— Советские аудиосказки

Басни для детей

— Басни Крылова

— Басни Лафонтена

— Басни Михалкова

— Басни Толстого

— Басни Эзопа

Блог

Диафильмы

Загадки для детей

— Загадки для родителей

— Сборник загадок

Мифы

— Мифы Древнего Китая

— Мифы Древнего Рима

— Мифы Древней Греции

— Мифы Древней Руси

— Мифы и легенды Индии

— Скандинавские мифы

Песни для детей

— Детские песни из мультфильмов

— Звуки природы для детей

— Колыбельные для малышей

— Музыка Моцарта для детей

— Песни для малышей

— Песни про маму

Поделки для детей

Пословицы и поговорки

Раскраски для детей

— Вокруг света

— Времена года

— Развивающие раскраски

— Раскраски Винкс

— Раскраски для взрослых

— Раскраски для девочек

— Раскраски для малышей

— Раскраски для мальчишек

— Раскраски животных

— Раскраски игр и игрушек

— Раскраски из мультфильмов

— Раскраски к праздникам

Сказки для детей любого возраста

— Анализ произведений

— Арабские сказки

— Денискины рассказы Драгунского

— Краткие содержания

— Повести для детей и подростков

— Рассказы Бориса Житкова

— Рассказы Виталия Бианки

— Рассказы Гайдара

— Рассказы Зощенко

— Рассказы Николая Носова

— Рассказы Платонова

— Рассказы Пришвина для детей

— Романы Марка Твена

— Русские народные сказки

— Сказки Аксакова

— Сказки Александра Волкова

— Сказки Алексея Николаевича Толстого

— Сказки Андерсена

— Сказки Андрея Усачева

— Сказки Астрид Линдгрен

— Сказки Бажова

— Сказки братьев Гримм

— Сказки Вильгельма Гауфа

— Сказки Владимира Сутеева

— Сказки Гаршина

— Сказки Гофмана

— Сказки Джанни Родари

— Сказки Евгения Шварца

— Сказки Киплинга

— Сказки Льва Николаевича Толстого

— Сказки Мамин-Сибиряк

— Сказки Маршака

— Сказки народов мира

— Сказки Одоевского

— Сказки Остера

— Сказки Пушкина

— Сказки Салтыкова-Щедрина

— Сказки Чуковского

— Сказки Шарля Перро

— Советские сказки

Стихи для детей

— Анализ стихотворений

— Детские стихи для заучивания

— Сказки в стихах

— Стихи Агнии Барто

— Стихи Берестова для детей

— Стихи Бориса Заходера

— Стихи Бунина

— Стихи Генриха Сапгира

— Стихи для детей 1, 2, 3 лет

— Стихи для детей 10, 11 лет и старше

— Стихи для детей 4, 5, 6 лет

— Стихи для детей 7, 8, 9 лет

— Стихи Елены Благининой для детей

— Стихи Есенина для детей

— Стихи Мандельштама

— Стихи Маршака

— Стихи Маяковского

— Стихи Мецгера

— Стихи Михалкова

— Стихи о девочках

— Стихи о мальчиках

— Стихи про быка

— Стихи про пословицы

— Стихи Пушкина

— Стихи Сурикова для детей

— Стихи Татьяны Гусаровой

— Стихи Успенского для детей

— Стихи Хармса

Мы используем файлы cookies для улучшения работы сайта. Оставаясь на нашем сайте, вы соглашаетесь с условиями использования файлов cookies.

Мы используем файлы cookies для улучшения работы сайта. Оставаясь на нашем сайте, вы соглашаетесь с условиями использования файлов cookies.

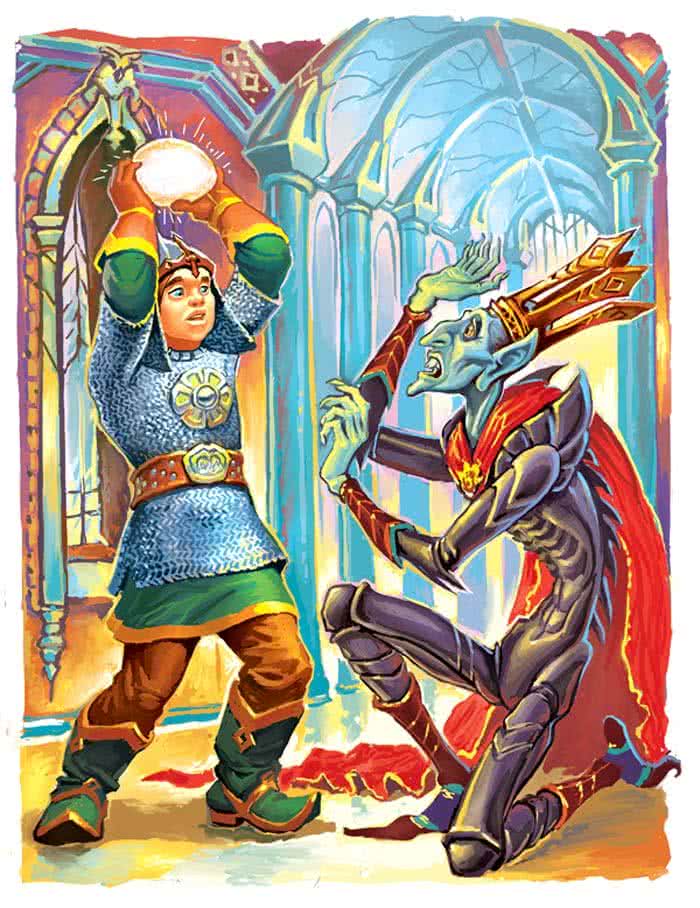

Сказка о Иване-царевиче, который пошел вызволять свою мать из плена Кощея Бессметного. Сила великая, храбрость и везение помогли Ивану найти смерть Кощея. А ум и хитрость помогли пресечь лукавство братьев…

Кощей Бессмертный читать

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был царь; у этого царя было три сына, все они были на возрасте. Только мать их вдруг унёс Кощей Бессмертный.

Старший сын и просит у отца благословенье искать мать. Отец благословил; он уехал и без вести пропал.

Средний сын пождал-пождал, тоже выпросился у отца, уехал, — и этот без вести пропал.

Малый сын, Иван-царевич, говорит отцу:

— Батюшка! Благословляй меня искать матушку.

Отец не пускает, говорит:

— Тех нет братовей, да и ты уедешь: я с кручины умру!

— Нет, батюшка, благословишь — поеду, и не благословишь — поеду.

Отец благословил.

Иван-царевич пошел выбирать себе коня; на которого руку положит, тот и падет; не мог выбрать себе коня, идет дорогой по городу, повесил голову. Неоткуда взялась старуха, спрашивает:

— Что, Иван-царевич, повесил голову?

— Уйди, старуха! На руку положу, другой пришлепну — мокренько будет.

Старуха обежала другим переулком, идет опять навстречу, говорит:

— Здравствуй, Иван-царевич! Что повесил голову?

Он и думает: «Что же старуха меня спрашивает? Не поможет ли мне она?»

И говорит ей:

— Вот, бабушка, не могу найти себе доброго коня.

— Дурашка, мучишься, а старухе не кучишься! — отвечает старуха. — Пойдем со мной.

Привела его к горе, указала место:

— Скапывай эту землю.

Иван-царевич скопал, видит чугунную доску на двенадцати замках; замки он тотчас же сорвал и двери отворил, вошел под землю: тут прикован на двенадцати цепях богатырский конь; он, видно, услышал ездока по себе, заржал, забился, все двенадцать цепей порвал.

Иван-царевич надел на себя богатырские доспехи, надел на коня узду, черкасское седло, дал старухе денег и сказал:

— Благословляй и прощай, бабушка!

Сам сел и поехал.

Долго ездил, наконец доехал до горы; пребольшущая гора, крутая, взъехать на нее никак нельзя. Тут и братья его ездят возле горы; поздоровались, поехали вместе; доезжают до чугунного камня пудов в полтораста, на камне надпись: кто этот камень бросит на гору, тому и ход будет.

Старшие братья не могли поднять камень, а Иван-царевич с одного маху забросил на гору — и тотчас в горе показалась лестница.

Он оставил коня, наточил из мизинца в стакан крови, подает братьям и говорит:

— Ежели в стакане кровь почернеет, не ждите меня: значит, я умру!

Простился и пошел. Зашел на гору; чего он не насмотрелся! Всяки тут леса, всяки ягоды, всяки птицы!

Долго шел Иван-царевич, дошел до дому: огромный дом! В нем жила царская дочь, утащена Кощеем Бессмертным.

Иван-царевич кругом ограды ходит, а дверей не видит. Царская дочь увидела человека, вышла на балкон, кричит ему:

— Тут, смотри, у ограды есть щель, тронь ее мизинцем, и будут двери.

Так и сделалось. Иван-царевич вошел в дом. Девица его приняла, напоила-накормила и расспросила. Он ей рассказал, что пошел доставать мать от Кощея Бессмертного. Девица говорит ему на это:

— Трудно будет достать тебе мать, Иван-царевич! Он ведь бессмертный — убьет тебя. Ко мне он часто ездит… вон у него меч в пятьсот пудов, поднимешь ли его? Тогда ступай!

Иван-царевич не только поднял меч, еще бросил кверху; сам пошел дальше.

Приходит к другому дому; двери знает как искать; вошел в дом, а тут его мать, обнялись, поплакали.

Он и здесь испытал свои силы, бросил какой-то шарик в полторы тысячи пудов. Время приходит быть Кощею Бессмертному; мать спрятала его. Вдруг Кощей Бессмертный входит в дом и говорит:

— Фу, фу! Русской костки слыхом не слыхать, видом не видать, а русская костка сама на двор пришла! Кто у тебя был? Не сын ли?

— Что ты, бог с тобой! Сам летал по Руси, нахватался русского духу, тебе и мерещится, — ответила мать Ивана-царевича. А сама поближе с ласковыми словами к Кощею Бессмертному, выспрашивает то-другое и говорит:

— Где же у тебя смерть, Кош Бессмертный?

— У меня смерть, — говорит он, — в таком-то месте; там стоит дуб, под дубом ящик, в ящике заяц, в зайце утка, в утке яйцо, в яйце моя смерть.

Сказал это Кощей Бессмертный, побыл немного и улетел.

Пришло время — Иван-царевич благословился у матери, отправился по смерть Коша Бессмертного.

Идет дорогой много время, не пивал, не едал, хочет есть до смерти и думает: кто бы на это время попался! Вдруг — волчонок; он хочет его убить. Выскакивает из норы волчиха и говорит:

— Не тронь моего детища; я тебе пригожусь.

— Быть так!

Иван-царевич отпустил волка; идет дальше, видит ворону.

«Постой, — думает, — здесь я закушу!» Зарядил ружье, хочет стрелять, ворона и говорит:

— Не тронь меня, я тебе пригожусь.

Иван-царевич подумал и отпустил ворону.

Идет дальше, доходит до моря, остановился на берегу. В это время вдруг взметался щучонок и выпал на берег, он его схватил, есть хочет смертно — думает: «Вот теперь поем!»

Неоткуда взялась щука, говорит:

— Не тронь, Иван-царевич, моего детища, я тебе пригожусь.

Он и щучонка отпустил.

Как пройти море? Сидит на берегу да думает; щука словно знала его думу, легла поперек моря. Иван-царевич прошел по ней, как по мосту; доходит до дуба, где была смерть Кощея Бессмертного, достал ящик, отворил — заяц выскочил и побежал. Где тут удержать зайца!

Испугался Иван-царевич, что отпустил зайца, призадумался, а волк, которого не убил он, кинулся за зайцем, поймал и несет к Ивану-царевичу. Он обрадовался, схватил зайца, распорол его и как-то оробел: утка спорхнула и полетела. Он пострелял, пострелял — мимо! Задумался опять.

Неоткуда взялась ворона с воронятами и ступай за уткой, поймала утку, принесла Ивану-царевичу. Царевич обрадовался, достал яйцо, пошел, доходит до моря, стал мыть яичко, да и выронил в воду. Как достать из моря? Безмерна глубь! Закручинился опять царевич.

Вдруг море встрепенулось — и щука принесла ему яйцо, потом легла поперек моря. Иван-царевич прошел по ней и отправился к матери; приходит, поздоровались, и она его опять спрятала.

В то время прилетел Кощей Бессмертный и говорит:

— Фу, фу! Русской костки слыхом не слыхать, видом не видать, а здесь Русью несет!

— Что ты, Кош? У меня никого нет, — отвечала мать Ивана-царевича.

Кощей опять и говорит:

— Я что-то не могу!

А Иван-царевич пожимал яичко: Кощея Бессмертного от того коробило. Наконец Иван-царевич вышел, кажет яйцо и говорит:

— Вот, Кощей Бессмертный, твоя смерть!

Тот на коленки против него встал и говорит:

— Не бей меня, Иван-царевич, станем жить дружно; нам весь мир будет покорен.

Иван-царевич не обольстился его словами, раздавил яичко — и Кощей Бессмертный умер.

Взяли они, Иван-царевич с матерью, что было нужно, пошли на родную сторону; по пути зашли за царской дочерью, к которой Иван-царевич заходил, взяли и ее с собой; пошли дальше, доходят до горы, где братья Ивана-царевича все ждут. Девица говорит:

— Иван-царевич! Воротись ко мне в дом; я забыла подвенечное платье, брильянтовый перстень и нешитые башмаки.

Между тем он спустил мать и царскую дочь, с коей они условились дома обвенчаться; братья приняли их, да взяли спуск и перерезали, чтобы Ивану-царевичу нельзя было спуститься, мать и девицу как-то угрозами уговорили, чтобы дома про Ивана-царевича не сказывали. Прибыли в свое царство; отец обрадовался детям и жене, только печалился об одном Иване-царевиче.

А Иван-царевич воротился в дом своей невесты, взял обручальный перстень, подвенечное платье и нешитые башмаки; приходит на гору, метнул с руки на руку перстень. Явилось двенадцать молодцов, спрашивают:

— Что прикажете?

— Перенесите меня вот с этой горы.

Молодцы тотчас его спустили. Иван-царевич надел перстень — их не стало; пошел в свое царство, приходит в тот город, где жил его отец и братья, остановился у одной старушки и спрашивает:

— Что, бабушка, нового в вашем царстве?

— Да чего, дитятко! Вот наша царица была в плену у Кощея Бессмертного; ее искали три сына, двое нашли и воротились, а третьего, Ивана-царевича, нет, и не знают, где. Царь кручинится об нем. А эти царевичи с матерью привезли какую-то царскую дочь, большак жениться на ней хочет, да она посылает наперед куда-то за обручальным перстнем или вели сделать такое же кольцо, какое ей надо; колдася уж кличут клич, да никто не выискивается.

— Ступай, бабушка, скажи царю, что ты сделаешь; а я пособлю, — говорит Иван-царевич.

Старуха прибежала к царю и говорит:

— Ваше царское величество! Обручальный перстень я сделаю.

— Сделай, сделай, бабушка! Мы таким людям рады, — говорит царь, — а если не сделаешь, то голову на плаху.

Старуха перепугалась, пришла домой, заставляет Ивана-царевича делать перстень, а Иван-царевич спит, мало думает, перстень готов. Он шутит над старухой, а старуха трясется вся, плачет, ругает его:

— Вот ты, — говорит, — сам-то в стороне, а меня, дуру, подвел под смерть.

Плакала, плакала старуха и уснула.

Иван-царевич встал поутру рано, будит старуху:

— Вставай, бабушка, да ступай неси перстень, да смотри: больше одного червонца за него не бери. Если спросят, кто сделал перстень, скажи: сама; на меня не сказывай!

Старуха обрадовалась, снесла перстень; невесте понравился.

— Такой, — говорит, — и надо!

Вынесла ей полно блюдо золота; она взяла один только червонец. Царь говорит:

— Что, бабушка, мало берешь?

— На что мне много-то, ваше царское величество! После понадобятся — ты же мне дашь.

Сказала это старуха и ушла.

Прошло какое-то время — вести носятся, что невеста посылает жениха за подвенечным платьем или велит сшить такое же, какое ей надо. Старуха и тут успела (Иван-царевич помог), снесла подвенечное платье.

После снесла нешитые башмаки, а червонцев брала по одному и сказывала: эти вещи сама делает.

Слышат люди, что у царя в такой-то день свадьба; дождались и того дня. А Иван-царевич старухе наказал:

— Смотри, бабушка, как невесту привезут под венец, ты скажи мне.

Старуха время не пропустила. Иван-царевич тотчас оделся в царское платье, выходит:

— Вот, бабушка, я какой!

Старуха в ноги ему.

— Батюшка, прости, я тебя ругала!

— Бог простит.

Приходит в церковь. Брата его еще не было. Он стал в ряд с невестой; их обвенчали и повели во дворец.

На дороге попадается навстречу жених, большой брат, увидал, что невесту ведут с Иваном-царевичем, и пошел со стыдом обратно.

Отец обрадовался Ивану-царевичу, узнал о лукавстве братьев и, как отпировали свадьбу, больших сыновей разослал в ссылку, а Ивана-царевича сделал наследником.

(Афанасьев, т.1, записано в Щадринском округе Пермской губернии, илл. В.Служаева)

❤️ 216

🔥 163

😁 159

😢 113

👎 103

🥱 123

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит

Рубрика «Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного»

Самый главный злодей множества сказок, страшный и коварный Кощей Бессмертный часто пугает детей. Но зато как приятно, дослушав сказку до конца, узнавать, что и на такого сильного злодея найдется управа! Переживание чувства страха в некоторой мере полезно для ребенка, переживая его при чтении сказок он становится более подготовлен к реальным неприятным ситуациям. Безусловно, увлекаться страшными историями не стоит, но и полностью отказываться от них психологи не советуют. Тем более, что в сказке добро обязательно победит зло!

Булат-молодец4.4 (7)

Жил-был царь, у него был один сын. Когда царевич был мал, то мамки и няньки его прибаюкивали: — Баю-баю, Иван-царевич! Вырастешь большой, найдешь себе невесту: за тридевять земель, в тридесятом государстве сидит в башне Василиса. Минуло царевичу пятнадцать лет, стал у отца проситься поехать поискать свою невесту. — Куда ты поедешь? Ты еще слишком мал! …

Читать далее

Марья Моревна5 (1)

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был Иван-царевич; у него было три сестры: одна Марья-царевна, другая Ольга-царевна, третья — Анна-царевна. Отец и мать у них померли; умирая, они сыну наказывали: — Кто первый за твоих сестер станет свататься, за того и отдавай — при себе не держи долго! Царевич похоронил родителей и с горя пошел …

Читать далее

Царевна-лягушка5 (2)

В старые годы у одного царя было три сына. Вот, когда сыновья стали на возрасте, царь собрал их и говорит: — Сынки, мои любезные, покуда я ещё не стар, мне охота бы вас женить, посмотреть на ваших деточек, на моих внучат. Сыновья отцу отвечают: — Так что ж, батюшка, благослови. На ком тебе желательно нас …

Читать далее

Кощей-Бессмертный4 (6)

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был царь; у этого царя было три сына, все они были на возрасте. Только мать их вдруг унёс Кощей Бессмертный. Старший сын и просит у отца благословенье искать мать. Отец благословил; он уехал и без вести пропал. Средний сын пождал-пождал, тоже выпросился у отца, уехал, — и этот без …

Читать далее

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был царь; у этого царя было три сына, все они были на возрасте. Только мать их вдруг унёс Кощей Бессмертный.

Старший сын и просит у отца благословенье искать мать. Отец благословил; он уехал и без вести пропал.

Средний сын пождал-пождал, тоже выпросился у отца, уехал, — и этот без вести пропал.

Малый сын, Иван-царевич, говорит отцу:

— Батюшка! Благословляй меня искать матушку.

Отец не пускает, говорит:

— Тех нет братовей, да и ты уедешь: я с кручины умру!

— Нет, батюшка, благословишь — поеду, и не благословишь — поеду.

Отец благословил.

Иван-царевич пошел выбирать себе коня; на которого руку положит, тот и падет; не мог выбрать себе коня, идет дорогой по городу, повесил голову. Неоткуда взялась старуха, спрашивает:

— Что, Иван-царевич, повесил голову?

— Уйди, старуха! На руку положу, другой пришлепну — мокренько будет.

Старуха обежала другим переулком, идет опять навстречу, говорит:

— Здравствуй, Иван-царевич! Что повесил голову?

Он и думает: «Что же старуха меня спрашивает? Не поможет ли мне она?»

И говорит ей:

— Вот, бабушка, не могу найти себе доброго коня.

— Дурашка, мучишься, а старухе не кучишься! — отвечает старуха. — Пойдем со мной.

Привела его к горе, указала место:

— Скапывай эту землю.

Иван-царевич скопал, видит чугунную доску на двенадцати замках; замки он тотчас же сорвал и двери отворил, вошел под землю: тут прикован на двенадцати цепях богатырский конь; он, видно, услышал ездока по себе, заржал, забился, все двенадцать цепей порвал.

Иван-царевич надел на себя богатырские доспехи, надел на коня узду, черкасское седло, дал старухе денег и сказал:

— Благословляй и прощай, бабушка!

Сам сел и поехал.

Долго ездил, наконец доехал до горы; пребольшущая гора, крутая, взъехать на нее никак нельзя. Тут и братья его ездят возле горы; поздоровались, поехали вместе; доезжают до чугунного камня пудов в полтораста, на камне надпись: кто этот камень бросит на гору, тому и ход будет.

Старшие братовья не могли поднять камень, а Иван-царевич с одного маху забросил на гору — и тотчас в горе показалась лестница.

Он оставил коня, наточил из мизинца в стакан крови, подает братьям и говорит:

— Ежели в стакане кровь почернеет, не ждите меня: значит, я умру!

Простился и пошел. Зашел на гору; чего он не насмотрелся! Всяки тут леса, всяки ягоды, всяки птицы!

Долго шел Иван-царевич, дошел до дому: огромный дом! В нем жила царская дочь, утащена Кощеем Бессмертным.

Иван-царевич кругом ограды ходит, а дверей не видит. Царская дочь увидела человека, вышла на балкон, кричит ему:

— Тут, смотри, у ограды есть щель, тронь ее мизинцем, и будут двери.

Так и сделалось. Иван-царевич вошел в дом. Девица его приняла, напоила-накормила и расспросила. Он ей рассказал, что пошел доставать мать от Кощея Бессмертного. Девица говорит ему на это:

— Трудно будет достать тебе мать, Иван-царевич! Он ведь бессмертный — убьет тебя. Ко мне он часто ездит… вон у него меч в пятьсот пудов, поднимешь ли его? Тогда ступай!

Иван-царевич не только поднял меч, еще бросил кверху; сам пошел дальше.

Приходит к другому дому; двери знает как искать; вошел в дом, а тут его мать, обнялись, поплакали.

Он и здесь испытал свои силы, бросил какой-то шарик в полторы тысячи пудов. Время приходит быть Кощею Бессмертному; мать спрятала его. Вдруг Кощей Бессмертный входит в дом и говорит:

— Фу, фу! Русской коски слыхом не слыхать, видом не видать, а русская коска сама на двор пришла! Кто у тебя был? Не сын ли?

— Что ты, бог с тобой! Сам летал по Руси, нахватался русского духу, тебе и мерещится, — ответила мать Ивана-царевича. А сама поближе с ласковыми словами к Кощею Бессмертному, выспрашивает то-другое и говорит:

— Где же у тебя смерть, Кош Бессмертный?

— У меня смерть, — говорит он, — в таком-то месте; там стоит дуб, под дубом ящик, в ящике заяц, в зайце утка, в утке яйцо, в яйце моя смерть.

Сказал это Кощей Бессмертный, побыл немного и улетел.

Пришло время — Иван-царевич благословился у матери, отправился по смерть Коша Бессмертного.

Идет дорогой много время, не пивал, не едал, хочет есть до смерти и думает: кто бы на это время попался! Вдруг — волчонок; он хочет его убить. Выскакивает из норы волчиха и говорит:

— Не тронь моего детища; я тебе пригожусь.

— Быть так!

Иван-царевич отпустил волка; идет дальше, видит ворону.

«Постой, — думает, — здесь я закушу!» Зарядил ружье, хочет стрелять, ворона и говорит:

— Не тронь меня, я тебе пригожусь.

Иван-царевич подумал и отпустил ворону.

Идет дальше, доходит до моря, остановился на берегу. В это время вдруг взметался щучонок и выпал на берег, он его схватил, есть хочет смертно — думает: «Вот теперь поем!»

Неоткуда взялась щука, говорит:

— Не тронь, Иван-царевич, моего детища, я тебе пригожусь.

Он и щучонка отпустил.

Как пройти море? Сидит на берегу да думает; щука словно знала его думу, легла поперек моря. Иван-царевич прошел по ней, как по мосту; доходит до дуба, где была смерть Кощея Бессмертного, достал ящик, отворил — заяц выскочил и побежал. Где тут удержать зайца!

Испугался Иван-царевич, что отпустил зайца, призадумался, а волк, которого не убил он, кинулся за зайцем, поймал и несет к Ивану-царевичу. Он обрадовался, схватил зайца, распорол его и как-то оробел: утка спорхнула и полетела. Он пострелял, пострелял — мимо! Задумался опять.

Неоткуда взялась ворона с воронятами и ступай за уткой, поймала утку, принесла Ивану-царевичу. Царевич обрадовался, достал яйцо, пошел, доходит до моря, стал мыть яичко, да и выронил в воду. Как достать из моря? Безмерна глубь! Закручинился опять царевич.

Вдруг море встрепенулось — и щука принесла ему яйцо, потом легла поперек моря. Иван-царевич прошел по ней и отправился к матери; приходит, поздоровались, и она его опять спрятала.

В то время прилетел Кощей Бессмертный и говорит:

— Фу, фу! Русской коски слыхом не слыхать, видом не видать, а здесь Русью несет!

— Что ты, Кош? У меня никого нет, — отвечала мать Ивана-царевича.

Кощей опять и говорит:

— Я что-то не могу!

А Иван-царевич пожимал яичко: Кощея Бессмертного от того коробило. Наконец Иван-царевич вышел, кажет яйцо и говорит:

— Вот, Кощей Бессмертный, твоя смерть!

Тот на коленки против него встал и говорит:

— Не бей меня, Иван-царевич, станем жить дружно; нам весь мир будет покорен.

Иван-царевич не обольстился его словами, раздавил яичко — и Кощей Бессмертный умер.

Взяли они, Иван-царевич с матерью, что было нужно, пошли на родиму сторону; по пути зашли за царской дочерью, к которой Иван-царевич заходил, взяли и ее с собой; пошли дальше, доходят до горы, где братья Ивана-царевича все ждут. Девица говорит:

— Иван-царевич! Воротись ко мне в дом; я забыла подвенечное платье, брильянтовый перстень и нешитые башмаки.

Между тем он спустил мать и царскую дочь, с коей они условились дома обвенчаться; братья приняли их, да взяли спуск и перерезали, чтобы Ивану-царевичу нельзя было спуститься, мать и девицу как-то угрозами уговорили, чтобы дома про Ивана-царевича не сказывали. Прибыли в свое царство; отец обрадовался детям и жене, только печалился об одном Иване-царевиче.

А Иван-царевич воротился в дом своей невесты, взял обручальный перстень, подвенечное платье и нешитые башмаки; приходит на гору, метнул с руки на руку перстень. Явилось двенадцать молодцов, спрашивают:

— Что прикажете?

— Перенесите меня вот с этой горы.

Молодцы тотчас его спустили. Иван-царевич надел перстень — их не стало; пошел в свое царство, приходит в тот город, где жил его отец и братья, остановился у одной старушки и спрашивает:

— Что, бабушка, нового в вашем царстве?

— Да чего, дитятко! Вот наша царица была в плену у Кощея Бессмертного; ее искали три сына, двое нашли и воротились, а третьего, Ивана-царевича, нет, и не знают, где. Царь кручинится об нем. А эти царевичи с матерью привезли какую-то царскую дочь, большак жениться на ней хочет, да она посылает наперед куда-то за обручальным перстнем или вели сделать такое же кольцо, какое ей надо; колдася уж кличут клич, да никто не выискивается.

— Ступай, бабушка, скажи царю, что ты сделаешь; а я пособлю, — говорит Иван-царевич.

Старуха в кою пору скрутилась, побежала к царю и говорит:

— Ваше царское величество! Обручальный перстень я сделаю.

— Сделай, сделай, бабушка! Мы таким людям рады, — говорит царь, — а если не сделаешь, то голову на плаху.

Старуха перепугалась, пришла домой, заставляет Ивана-царевича делать перстень, а Иван-царевич спит, мало думает, перстень готов. Он шутит над старухой, а старуха трясется вся, плачет, ругает его:

— Вот ты, — говорит, — сам-то в стороне, а меня, дуру, подвел под смерть.

Плакала, плакала старуха и уснула.

Иван-царевич встал поутру рано, будит старуху:

— Вставай, бабушка, да ступай неси перстень, да смотри: больше одного червонца за него не бери. Если спросят, кто сделал перстень, скажи: сама; на меня не сказывай!

Старуха обрадовалась, снесла перстень; невесте понравился.

— Такой, — говорит, — и надо!

Вынесла ей полно блюдо золота; она взяла один только червонец. Царь говорит:

— Что, бабушка, мало берешь?

— На что мне много-то, ваше царское величество! После понадобятся — ты же мне дашь.

Пробаяла это старуха и ушла.

Прошло какое-то время — вести носятся, что невеста посылает жениха за подвенечным платьем или велит сшить такое же, какое ей надо. Старуха и тут успела (Иван-царевич помог), снесла подвенечное платье.

После снесла нешитые башмаки, а червонцев брала по одному и сказывала: эти вещи сама делает.

Слышат люди, что у царя в такой-то день свадьба; дождались и того дня. А Иван-царевич старухе наказал:

— Смотри, бабушка, как невесту привезут под венец, ты скажи мне.

Старуха время не пропустила. Иван-царевич тотчас оделся в царское платье, выходит:

— Вот, бабушка, я какой!

Старуха в ноги ему.

— Батюшка, прости, я тебя ругала!

— Бог простит.

Приходит в церковь. Брата его еще не было. Он стал в ряд с невестой; их обвенчали и повели во дворец.

На дороге попадается навстречу жених, большой брат, увидал, что невесту ведут с Иваном-царевичем, и пошел со стыдом обратно.

Отец обрадовался Ивану-царевичу, узнал о лукавстве братьев и, как отпировали свадьбу, больших сыновей разослал в ссылку, а Ивана-царевича сделал наследником.

Иллюстрации Игоря Егунова.

| The Death of Koschei the Deathless | |

|---|---|

Sorcerer Koschei the Deathless abducts Marya Morevna. Illustration by Zvorykin. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Death of Koschei the Deathless |

| Also known as | Marya Morevna |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping |

|

| Region | Russia |

| Published in | Narodnye russkie skazki, by Alexander Afanasyev |

The Death of Koschei the Deathless or Marya Morevna (Russian: Марья Моревна) is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki and included by Andrew Lang in The Red Fairy Book.[1] The character Koschei is an evil immortal man who menaces young women with his magic.

Plot[edit]

Ivan Tsarevitch had three sisters, the first was Princess Maria, the second was Princess Olga, the third was Princess Anna. After his parents die and his sisters marry three wizards, he leaves his home in search of his sisters. He meets Marya Morevna, a beautiful warrior princess, and marries her. After a while she announces she is going to go to war and tells Ivan not to open the door of the dungeon in the castle they live in while she will be away. Overcome by the desire to know what the dungeon holds, he opens the door soon after her departure and finds Koschei, chained and emaciated. Koschei asks Ivan to bring him some water; Ivan does so. After Koschei drinks twelve buckets of water, his magic powers return to him, he breaks his chains and disappears. Soon after Ivan finds out that Koschei has captured Marya Morevna, and pursues him. When Ivan catches up with Koschei, Koschei tells Ivan to let him go, but Ivan does not give in, and Koschei kills him, puts his remains into a barrel and throws it into the sea. Ivan is revived by his sisters’ husbands – powerful wizards who can transform into birds of prey. They tell him that Koschei has a magic horse and that Ivan should go to Baba Yaga to get one too, or else he will not be able to defeat Koschei. After Ivan survives Yaga’s tests and gets the horse, he fights with Koschei, kills him and burns his body. Marya Morevna returns to Ivan, and they celebrate his victory with his sisters and their husbands.

Translations[edit]

A translation of the tale by Irina Zheleznova was Marya Morevna The Lovely Tsarevna.[2]

Analysis[edit]

Classification[edit]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 552 (The Girls who Married Animals),[3] with an episode of type ATU 302 (The Giant/Ogre who had no heart in his body). In fact, this tale, also known as The Death of Koschei in the Egg, is one of «the most popular Russian folktales».[4]

On the other hand, slavicist Karel Horálek cited that a 1959 Russian edition of Afanasyev’s Russian Fairy Tales indicated that the tale «Mar’ja Morevna» was a combination of types: AaTh 552, 400 («The Quest for the Lost Wife») and 554 («The Grateful Animals»).[5] In the same vein, professor Jack Haney also stated that the sequence of tale types AT 552A, AT 400/1, AT 554 and AT 302/2 was «the traditional combination of tale types» for the story.[6]

The forbidden room[edit]

Czech scholar Karel Horálek [cs] mentioned that tale type AaTh 552 («specially in Slavic variants») shows the motif of the hero opening, against his wife’s orders, a door or the dungeon and liberating a Giant or Ogre that kills him.[7]

According to professor Andreas Johns, scholar Carl Wilhelm von Sydow distinguished a Slavic oikotype of the narrative (also present in Hungarian variants): the hero is warned against opening a door, which he does anyway. The hero sees an imprisoned ogre to whom he gives water and releases him. The ogre’s next act is to kidnap the hero’s wife.[8]

The hero’s horse helper[edit]

In several variants, the hero manages to defeat the villain with the help of a magical horse he tamed while working for Baba Yaga or other supernatural creature. As such, these tales can also be classified as ATU 302C, «The Magical Horse».[9][10][a] The episode of taming the horse of the wizard/sorcerer fits tale type ATU 556F*, «Herding the Wizard’s Horses».[12] The tale is classified as subtype AaTh 302C because in the international index of folktypes both subtypes AaTh 302A and AaTh 302B were previously occupied by other stories.[13]

Hungarian-American scholar Linda Degh stated that the tale type 302 was «extended … through addition» of the type 556F*, a combination she claimed was «little known in Europe … except in mostly Slavic, Rumanian, and Hungarian language areas».[14][b] Professor Andreas Johns corroborates Degh’s analysis. He states that this subtype 302/2, «Koschei’s Death from a Horse», occurs in the «Slavic and Hungarian folk repertoire»: after the hero acquires the powerful horse, it either tramples the sorcerer with its hooves or influences Koschei’s mount to drop its rider to his death.[16]

Estonian scholarship also locates type 302 with the witch’s magical horse in Central and Eastern Europe.[17]

The animal suitors[edit]

The tale of Marya Morevna and Koschei the Deathless (both in the same variant) is considered the most representative version of the ATU 552 tale type in Russia.[18] The tale type is characterized by the hero’s sisters marrying animals. In some versions, the suitors are wizards or anthropomorphizations of forces of nature, like Wind, Thunder and Rain, or natural features, like the Sun and the Moon.[19][20] Richard MacGillivray Dawkins also noted that in some variants, the suitors are «persons of great and magical potency», but appear to court the princesses under shaggy and ragged disguises.[21]

Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev, based on comparative analysis of Slavic folkloric traditions, stated that the eagle, the falcon and the raven (or crow) are connected to weather phenomena, like storm, rain, wind. He also saw a parallel between the avian suitors from the tale Marya Morevna with the suitors from other Slavic folktales, where they are the Sun, the Moon, the Thunder and the Wind.[22] In a comparative study, Karelian scholarship noted that, in Russian variants, there are three brothers-in-law, the most common are three ornitomorphic characters: the eagle (named Orel Orlovich), the falcon (named Sokol Sokolovich) and the raven (almost always the third suitor, called Voron Voronovich). They sometimes may be replaced — depending on the location — by another bird (the dove or the magpie) or by a mammal (the bear, the wolf, the seal or the deer).[23]

It has been suggested that the tale type ATU 552 may have been derived from an original form that closely resembles ATU 554, «The Grateful Animals», and, in turn, ATU 554 and ATU 302, «Devil’s Heart in the Egg», would show a deeper connection due to the presence of animal helpers. Further relations are seen between both tale types, type ATU 301 and its subtypes, «Three Stolen Princesses» and «Jean de l’Ours», and ATU 650, «Strong Hans»/»Strong John».[24][c][d]

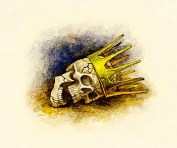

The Life (Heart) in the Egg[edit]

The tale type ATU 302, «The Giant (Ogre) who had no heart in his body» or «Ogre’s Heart in the Egg», is a «world folklore tale type». These stories tell of a villain who hides his life force or «heart» in a place outside his body, in a box or inside a series of animals, like a Russian matryoshka. The hero must seek and destroy the heart to vanquish the villain. With the help of the villain’s wife or female prisoner (a princess), he locates the ogre’s weakness and, aided by grateful animals or his animal brothers-in-law,[28] destroys the heart.[29]

According to professor Stith Thompson, the tale is very popular «in the whole area from Ireland to India», with different locations of the giant’s heart: in Asian variants, it is hidden in a bird or insect, while in European tales it is guarded in an egg.[30]

Scholarship acknowledges the considerable antiquity and wide diffusion of the motif of the «external soul» (or life, «death», heart). For instance, folklorist Sir James George Frazer, in his book The Golden Bough, listed and compared several stories found across Eurasia and North Africa where the villain of the tale (ogres, witches and giants) willingly extracts their soul, hides it in an animal or in a box (casket) and therefore becomes unkillable, unless the hero destroys the recipient of their soul.[31]

According to Andreas Johns, Carl von Sydow estimated that the tale type 302 dated back thousand years BCE. Although the earliest printed version appears in a 1702 Swedish manuscript, Johns admitted that the oral tale may be, in fact, quite old.[32]

Variants[edit]

Koschey revived by Ivan with water, in the tale Marya Morevna. Illustration from The Red Fairy Book (1890).

Eastern Europe[edit]

In the Eastern European tale of The Story of Argilius and the Flame-King[33] (Zauberhelene,[34][35][36] or Trold-Helene[37]) after his sisters are married to the Sun-king, the Wind-king (or Storm-king) and the Moon-king, Prince Argilius (hu) journeys to find his own bride, Kavadiska (or Zauberhelene). They marry and his wife warns not to open the last chamber in their castle while she is away. Argilius disobeys and releases Holofernes, the Flame-King.

Linda Degh stated that «in Hungarian variants [the imprisoned villain] is often named Holofernus, Hollóferjös, Hollófernyiges», a name she believed to refer to the biblical king Holofernes and to the Hungarian word holló «raven».[38]

Central Europe[edit]

In a tale from Drava, Az acélember («The Man of Steel»), a father’s dying wish is for his brothers to marry off their sisters to anyone who passes by. The first to pass is the eagle king, the second the falcon king and the third the buzzard king. On their way to their sisters, they camp out in the woods. While his elder brothers are sleeping, the youngest kills the dragons that emerge from the lake. Later, he meets giants who want to kidnap a princess. The youth tricks them and decapitates their heads. His brothers wake up and go to the neighbouring castle. The king learns of the youth’s bravery and rewards him with his daughter’s hand in marriage. The king also gives him a set of keys and tells his son-in-law never to open the ninth door. He does and releases «The Steel Man», who kidnaps his wife as soon as she leaves the emperor’s church. In the last part of the tale, with the help of his avian brothers-in-law, he finds the Steel Man’s strength: inside a butterfly, inside a bird, inside a fox.[39]

Russia[edit]

In another Russian tale, Prince Egor and the Raven, a friendly Raven points prince Egor to a powerful warrior monarch, Queen Agraphiana the Fair, which the prince intends to make as his wife. After they meet, the Queen departs for war and Prince Egor explores her palace. He soon finds a forbidden chamber where a talking skeleton is imprisoned. The Prince naïvely helps the skeleton, it escapes and captures Queen Agraphiana.[40]

In another Russian variant, «Иванъ царевичъ и Марья Маревна» («Ivan Tsarevich and Marya Marevna»), collected by Ivan Khudyakov (ru), the young Ivan Tsarevich takes his sisters for a walk in the garden, when, suddenly, three whirlwinds capture the ladies. Three years later, the Tsarevich intends to court princess Marya Morevna, when, in his travels, he finds three old men, who reveal themselves as the whirlwinds and assume an avian form (the first a raven, the second an eagle and the third a falcon). After a series of adventures, Ivan Tsarevich and Marya Moreva marry and she gives his a silver key and warns him never to open its respective door. He does so and finds a giant snake chained to the wall.[41]

In a third Russian variant, «Анастасья Прекрасная и Иванъ Русский Богатырь» («The Beautiful Anastasia and Ivan, the Russian Bogatyr»), collected by Ivan Khudyakov (ru), the father of Ivan, the Russian Bogatyr, orders him, as a last wish, to marry his sister off to whomever appears at the castle. Three people appear and request Ivan to deliver them his sisters. Some time later, Ivan sees that three armies have been defeated by a warrior queen named Marya Marevna. Ivan invades her white tent and they face in combat. Ivan defeats her and she reveals she is not Marya Marevna, but a princess named Anastasia, the Beautiful. They yield and marry. Anastasia gives him the keys to her castle and warns him never to open a certain door. He does and meets Koshey, prisoner of Anastasia’s castle for 15 years. Ivan unwittingly helps the villain and he kidnaps his wife. The bogatyr, then, journeys through the world and visits his sisters, married to the Raven King, the Hawk King and the Eagle King. They advise him to find a mare that comes from the sea to vanquish Koschey.[42]

Professor Jack V. Haney also translated a variant[43] from storyteller Fedor Kabrenov (1895-?), from Pudozh.[44] In this tale, titled Ivan Tsarevich and Koshchei the Deathless, the sisters of prince Ivan Tsarevich decide to take a walk «in the open steppe», when three strange storms appear and seize each one of the maidens. After he goes in search of his sisters, he discovers them married to three men equally named Raven Ravenson, Talon Talonson (albeit with different physical characteristics: one with «brass nose, lead tail», the second with «brass nose, cast iron tail», and the third with «golden nose, steel tail»). He tells them he wants to court Maria Tsarevna, the princess of a foreign land. He visits her court but is locked up in prison. He trades three magical objects for a night with Maria Tsarevna. They marry, and Ivan Tsarevich releases Koschei the Deathless from his captivity «with the press of a button». Ivan is killed, but his avian brothers-in-law resurrect him with the living and dead waters, and tell him to seek a magical colt from the stables of Koschei’s mother.[45]

In another Russian variant translated by professor Jack Haney as The Three Sons-in-Law, the hero Ivan marries his three sisters to an eagle, a falcon and another man, then goes to find Marya Morevna, «The Princess with the Pouch». He opens the forbidden door to the castle and releases Kaschei the Immortal, who kidnaps his wife. Ivan summons his fiery horse «Sivko-Burko» and visits his sisters. When Ivan reaches Kaschei’s lair, Marya Morevna obtains a valuable information: the location of Kaschei’s external soul. She also finds out that the villain’s magical horse he obtained from herding Yega Yegishna’s twelve mares, in her abode across a fiery river.[46]

Mari people[edit]

In a tale from the Mari people titled «Ивук» («Ivuk»), in a certain village an old couple lives with his two beautiful daughters. One day, a stranger comes to court the elder. They are quite taken with one another and she vanishes overnight. The same thing happens to her sister. Years later, a boy named Ivuk is born to them. Ivuk decides to look for his two sisters. After tricking a group of demons, he gains some magical objects and teleports to the palace of Yorok Yorovich, who married his sister Myra. He later visits Orel Orlovich, the lord of the birds, and his wife Anna, Ivuk’s sister. Orel tells of a beautiful princess that lives in a Dark City, ruled by an evil sorceress queen. Both Orel and Yorok each give a strand of their hair to Ivuk to summon them, in case they need their help. Some time later, he defeats the sorceress queen and marries the princess. One day, he wanders through the forest and sees a huge rock with a door. He opens the door and a prisoner is chained inside. The prisoner begs Ivuk to give him deer meat. Ivuk obeys, the prisoner escapes, kills him and abducts his wife. Orel and Yorok appear and revive Ivuk with the water of death and the water of life, and tell him he must seek a wonderful horse that can defeat the prisoner’s. The only place he can find one is in the stables of the witch. He can gain the horse if he herds the witch’s horses for three days.[47]

Komi people[edit]

Linguist Paul Ariste collected a tale from tje Komi people with the title Ivan’s Life. In this tale, on his deathbed, Ivan’s father asks his son to marry his three sisters to rich men. After he dies, three old men appear at different times to take Ivan’s sisters as wives. Some time later, Ivan learns that the tsar will marry his daughter to whoever makes her laugh. Ivan also visits his sister and her husband, and is given three magic bottles. His brother-in-law also advises hm to plucks three hairs from a lion, before he arrives at the princess’s castle, surrounded by suitors’ heads on spike. Once there, he is arrested and thrown in prison. In his cell, Ivan opens the bottles, one at a time, and a small group of men appear. Ivan orders the man go fetch him vodkas, foods and a musical instrumentl. With the commotion in his cell, he is brought to the princess’s presence and trades the musical instrument each time. The third time, Ivan proposes to marry her, and she accepts. After her father dies, the princess inherits the entire castle and gives Ivan a set of keys, forbidding him to open the twelfth door. Ivan disobeys and opens a door; inside, a twelve-headed dragon chained to the wall. The dragon orders Ivan to bring him two kegs of vodka; he regains his strength and captures Ivan’s wife. Ivan manages to find her twice, but after the second time, the dragon chops his head off. His brother-in-law comes to his aid and revives him. The man advises Ivan to find an old woman’s hut whose mare is about to foal, and he should choose the 13th foal, after working for the old woman. On the way there, Ivan settles a quarrel between three crows and another between three mosquitoes, and puts a pike back into the water. At the end of the tale, Ivan’s foal grows into a large horse with 13 wings. Ivna rescues his wife and throws the dragon off his horse to kill him.[48]

Chuvash people[edit]

In a tale from the Chuvash people translated into Hungarian with the title Az asszony-padisah leánya («The Daughter of the Female Padishah»), an old woman on her deathbed begs her son, Jivan, to marry his sisters to whoever passes by their house. The son follows his mother’s last wish and marries his three sisters to three beggars. One day, he decides to visit each of his sisters. The first sister welcomes him and they have dinner. Then, a great storm rages outside the house, but the sister reveals it is her husband — a multiheaded dragon — that is coming home. The dragon changes into human form and joins the pair. Before the Jivan departs, he is given a chest by the dragon brother-in-law and a hair from his beard. The same event happens with the other two sisters. Then, the youth reaches the castle of the titular Daughter of the Female Padishah and opens one of the chests: a regiment appears. The guards detain Jivan and he is imprisoned by a warrior queen, in her dungeon. However, the youth takes out the three chests, opens one at a time, and delights the prisoners with the finest food, drinks and music. The guards take Jivan to the presence of the female padishah three times and she wants to buy his three chests, but Jivan refuses. Instead, he opens the third chest in front of the female padishah for her to see the wonders from the chest. The next day, the female padishah sees her daughter in Jivan’s arms and threatens to kill the youth, but her daughter says she may as well not spare her. The female padishah accepts Jivan as her son-in-law. The youth is told not to open a certain door, but he does and finds an imprisoned dragon. Jivan gives him a bit of water and he breaks off from his chains. The dragon threatens Jivan with kidnapping his wife, and that the youth shall try to rescue her three times. Jivan fails and is killed. By burning the hairs from his brothers-in-law, they appear to his aid: they resurrect him with the water of death and the water of life. Jivan goes to the dragon’s lair and tells his wife — now a prisoner of the creature — to get the dragon drunk to reveal the location of his weakness. He reveals his «life» is hidden in an egg inside a duck, inside a bull, by the sea. The dragon, in its inebriated state, also lets it escape that his own mount is part of a breed that belongs to a witch. Jivan goes next to the witch to herd her horses, gains one as reward for a job well done and uses it to get the egg containing the dragon’s life.[49]

In another Chuvash tale, titled «Мамалдык» («Mamaldyk»), a man named Tungyldyk has three daughters (Chagak, Cheges, and Cheppy) and a son named Mamaldyk. On his deathbed, the man asks his son to marry his three sisters to whomever passes by first. After he dies, Mamaldyk is visited by a wolf, a fish and a hawk, who each transform into men to court his three sisters. He marries them off. Later, Mamaldyk visits his three brothers-in-law and is given three hairs from the wolf, three scales from the fish and three feathers from the hawk. Then he marries the daughter of a man named Arsyuri. After Arsyuri dies, Mamaldyk’s wife gives him a set of keys, and forbids him from opening the 12th door. He disobeys the prohibition and opens the last door: inside, a trapped Serpent named Vereselen. Vereselen escapes and takes Mamaldyk’s wife with him. Mamaldyk gathers his brothers-in-law to help him. The youth reaches Vereselen’s lair, where Mamaldyk’s wife discovers that the serpent’s life is located in three eggs inside a duck, inside a bull, inside an oak tree, on an island in the middle of the ocean.[50]

Belarus[edit]

In a Belarusian variant (summarized by Slavicist Karel Horálek), «Прекрасная девица Алена» («Beautiful Girl Alena»),[51] one of the tsar’s sons marries his sisters to the Thunder, the Frost and the Rain. On his wanderings, he learns the titular Beautiful Alena is his destined bride. They marry, he releases a dragon that kidnaps his wife and discovers the dragon’s weakness lies within an egg inside a duck, inside a hare, inside an ox.[52]

In a second variant from Belarus, «Иван Иванович—римский царевич» (also cited by Horálek),[53] the hero, Ivan Tsarevich, marries his sisters to the Wind, the Storm and the King of the Birds. He also learns from an old woman of a beautiful warrior princess. He journeys to this warrior princess and wants to fight her (she is disguised as a man). They marry soon after. She gives him the keys to the castle and warns him never to enter a certain chamber. He opens it and releases a human-looking youth (the villain of the tale). The prince vanquishes this foe with the help of a horse.[54]

In a Belarusian tale published by folklorist Lev Barag [ru] and translated as Janko und die Königstochter («Janko and the King’s Daughter»), a dying king makes his son, Janko, promise to marry his three sisters to whomever appears after he dies. Some time later, three men, Raven Ravenson, Eagle Eagleson and Zander Zanderson, come to take the princesses as wives. Later, Janko steals items from quarrelling peoples and visits his three sisters. He rides his horse to a king and courts its princess with the magical objects he stole from the three man. They marry and she gives him a set of keys, forbidding him to open a certain door. Janko does and releases a dragon who kidnaps his wife. The dragon warns that Janko has three tries (or «lives») to follow him and try to regain his wife. After the third attempt, the dragon kills Janko. Janko’s brothers-in-law find his corpse and restore him to life with the water of life and the water of death. Janko is advised by his brothers-in-law to find a horse from a witch, which he does by herding her horses. At last, Janko rides the horse into battle, and his horse convinces the dragon’s mount — his brother — to drop the villain to the ground.[55]

Lithuania[edit]

In a Lithuanian variant, collected by Carl Cappeller [sv] with the title Kaiser Ohneseele («King With-no-Soul»), the protagonist weds his three sisters to the bird griffin, an eagle, and the king of nightingales.[56] The tale continues as his brothers-in-law help him to rescue his beloved princess, captured by Kaiser Ohneseele. The prince also helps three animals, an elk, an eagle and a crab, which will help him in finding the villain’s external heart.[57]

August Leskien collected another variant, Von dem Königssohn, der auszog, um seine drei Schwestern zu suchen, wherein the animals are a falcon, a griffin and an eagle. After their marriages to the hero’s sisters, the avian brothers-in-law gather to find a bride for him. They tell of a maiden the hero must defeat in combat before he marries her. He does, and, after the hero and the warrior maiden marry, she gives him a set of keys. The hero uses the keys to open a chamber in her castle and releases an enemy king.[58]

Latvia[edit]

In a Latvian tale, sourced as from the collection of Latvian lawyer Arveds Švābe (lv), «Три сестры, брат да яйцо бессмертия» («Three Sisters, A Brother, and the Egg of Immortality»), a dying king begs his only son to look after his three sisters. One day, while they are strolling in the garden, the three princess vanish with a srong gust of wind. Their brother goes after them, and, on the way, helps a hare, a wolf, a crab, a nest of wasps, mosquitoes and an eagle. He reaches three witches who live in houses that gyrate on chicken legs. He learns from them that his sisters are now married to a pike, an eagle and a bear — who are cursed princes — , and that to reach them, he must first seek an equine mount by taking up work with a witch. After he works with the witch, he flies on the horse to each of his sisters, and confirms the princes’ story: they are brothers who were cursed by a dragon whose life lies outside his body. Vowing to break their curse, the prince flies to the dragon’s palace, and meets a princess — the dragon’s prisoner.[59]

Hungary[edit]

In a Hungarian variant, Fekete saskirály («Black Eagle King»), a prince and his wife move to her father’s castle. When the prince explores the castle, he opens a door and finds a man nailed to a cross. The prisoner introduces himself as «Black Eagle King» and begs for water to drink. The prince helps him, and he escapes, taking the princess with him.[60]

In another Hungarian tale, Királyfi Jankó («The King’s Son, Jankó»), Jankó journeys with a talking horse to visit his brothers-in-law: a toad, the «saskirá» (Eagle King) and the «hollókirá» (Raven King). They advice Jankó on how to find «the world’s most beautiful woman», who Jankó intends to marry. He finds her, they marry, and he moves to her kingdom. When Jankó explores the castle, he finds a room where a many-headed dragon is imprisoned with golden chains. The prince helps the dragon regain his strength and it escapes, taking the prince’s wife with him.[61]

In another Hungarian variant, A Szélördög («The Wind Devil»), a dying king’s last wish is for his sons to wed their sisters to whoever passes by their castle. The youngest prince fulfills his father’s wishes by marrying his sisters to a beggar, a wolf, a serpent and a gerbil. Later on, the prince marries a foreign princess, opens a door in her palace and releases the Wind Devil.[62]

In a Hungarian tale published by Nándor Pogány, The Magic Cherry-Tree, a king is dying and only the cherries that grow on the top of a huge tree can cure him. A shepherd volunteers to climb up the tree to get them. After a while, he arrives at a diamond meadow and meets a princess sitting on a throne of opal and gems. After several adventures, they marry and she gives him the keys to the rooms in her castle. When he opens a door, he finds a twelve-headed dragon chained to the wall. The dragon asks the shepherd to release him, which the human does. After this, the dragon kidnaps the princess and the shepherd goes after him with the help of a golden-maned horse.[63]

Czech Republic[edit]

Author Božena Němcová collected a Czech fairy tale, O Slunečníku, Měsíčníku a Větrníku, where the prince’s sisters are married to the Sun, the Moon and the Wind.[64][65] A retelling of Nemcova’s version, titled O slunečníkovi, měsíčníkovi a větrníkovi, named the prince Silomil, who marries the unnamed warrior princess and frees a king with magical powers from his wife’s dungeon.[66]

Slovenia[edit]

Author Bozena Nemcova also collected a very similar Slovenian variant of the Czech fairy tale, titled O Slunečníku, Měsíčníku, Větrníku, o krásné Ulianě a dvou tátošíkách («About the Sun, the Moon, the Wind, the Beautiful Uliane and the Two Tátos«). The princesses are married to the Sun, the Moon and the Wind, and prince journeys until he finds the beautiful warrior princess Uliane. They marry. Later, she gives him the keys to her castle and tells him not to open the thirteenth door. He disobeys her orders and opens the door: there he finds a giant serpent named Šarkan.[67][68]

A second Slovenian variant, from Porabje (Rába Valley) was collected by Károly Krajczár (Karel Krajcar), with the title Lepi Miklavž or Leipe Miklauž. In this story, a youth that works in the stables wishes to impress the queen. With the help of an old, lame horse, the youth summons three magnificent horses and wonderful garments, which he uses to crash three royal appointments. The queen becomes fascinated with the splendid youth and discovers his identity. They marry. Soon after, while the queen is away, the youth opens a door in her castle and finds a creature chained to the wall, named šarkan. The youth gives him three drinks of water, he escapes and captures the queen.[69]

Croatia[edit]

Karel Jaromír Erben collected a Croatian variant titled Kraljević i vila («The King’s Son and the fairy»). In this tale, the Wind-King, the Sun-King and the Moon-King (in that order) wish to marry the king’s daughters. After that, the Kraljević visits his brothers-in-law and is gifted a bottle of «water of death» and a bottle of «water of life». In his travels, Kraljević comes across a trench full of soldiers’ heads. He uses the bottles on a head to discover what happened and learns it was the working of a fairy. Later, he meets the fairy and falls in love with her. They marry and she gives the keys to her palace and a warning: never to open the last door. Kraljević disobeys and meets a dangerous prisoner: Kralj Ognjen, the King of Fire, who escapes and captures the fairy.[70]

Serbia[edit]

In a Serbian variant, Bash Tchelik, or Real Steel, the prince accidentally releases Bash Tchelik from his prison, who kidnaps the prince’s wife. He later travels to his sisters’ kingdoms and discovers them married, respectively, to the king of dragons, the king of eagles and the king of falcons.[71] The tale was translated into English, first collected by British author Elodie Lawton Mijatovich with the name Bash-Chalek, or, True Steel,[72] and later as Steelpacha.[73]

In another Serbian variant published by Serbian educator Atanasije Nikolić, Путник и црвени ветар or Der Wanderer und der Rote Wind («The Wanderer and the Red Wind»), at their father’s dying request, three brothers marry their three sisters to the first passers-by (in this case, three animals). The brothers then camp out in the woods and kill three dragons. The youngest finds a man in the woods rising the sun and moon with a ball of yarn. He finds a group of robbers who want to invade the tsar’s palace. The prince goes on first, kills the robbers and saves a princess from a dragon. They marry and he opens a forbidden room where «The Red Wind» is imprisoned. The Red Wind kidnaps his wife and he goes after her, with the help of his animal brothers-in-law.[74][75] Slavicist Karel Horálek indicated it was a variant of the Turkish tale Der Windteufel («The Wind Devil»).[76]

Slavicist Karel Horálek also mentioned a variant from Serbia, titled «Атеш-Периша» («Atesh-Perisha»), published in newspaper Босанска вила (sr) (Bosanska vila).[77] This variant also begins with as the Tierschwäger («Animal Brothers-in-Law») tale type.[78]

Greece[edit]

In the context of Greek variants, Richard MacGillivray Dawkins identified two forms of the type, a simpler and a longer one. In the simple form, the protagonist receives help from the magic brothers-in-law in courting the «Fair One of the World». In the longer form, after the sisters’ marriages, the three brothers enter a forest and are attacked by three enemies, usually killed by the third brother. Later, the youngest brother finds a person who alternates day and night by manipulating balls of white and black yarn or skeins, whom he ties up a tree, and later finds a cadre of robbers or giants who intend to invade a nearby king’s castle. The tale also continues as the hero’s wife is abducted by an enemy creature whose soul lies in a external place.[79]

Albania[edit]

In an Albanian variant collected by Auguste Dozon and translated by Lucy Garnett as The Three Brothers and the Three Sisters, three brothers marry their sisters to the Sun, the Moon and the South Wind. One time, on their way to their sisters, the brothers camp out at night and each of them, on consecutive nights, stand vigil and kill a «Koutchédra» (Kulshedra) that came to devour them. On the youngest’s turn, the koutchédra snuffes out their light, and he has to get fire. He meets the «Mother of the Night», who alternates the day and night cycle, and ties her, so the day may be delayed. The youngest brother meets a band of brigands, lures them to the king’s palace and decapitates one by one. He loosens the Mother of Night and returns to his brothers. Meanwhile, the king sees the brigands’ corpses and decides to build a khan where everyone is to tell their story, in hopes of finding the person responsible. He discovers the youngest brother and marries him to his daughter. One day, the king says he will free some prisoner due to the upcoming eedding, and his soon-to-be son-in-law insists that he freed a «one half iron and half man» too. He does, and the prisoner escapes with the princess. The youth visits his brothers-in-law, takes a ride on an eagle’s back and reaches the villain’s hideout. He meets his wife and they conspire with each other to ask «Half-man-half-iron» where his strength was hidden: outside his body, in three pigeons inside a hare inside a boar’s silver tusk.[80]

Georgia[edit]

In a Georgian variant, sourced as Mingrelian, Kazha-ndii, the youngest prince gives his sisters as brides to three «demis». They later help him to rescue his bride from the antagonist.[81][82]

Armenia[edit]

Armenian scholarship lists 16 versions of type ATU 302 in Armenia, some with the character Ջանփոլադ (‘Ĵanp‘olad’, Corps d’acier or «Steel Body»), and in five variants of type ATU 552 (of 13 registered), the hero defeats the antagonist by locating his external soul.[83] According to researcher Tamar Hayrapetyan, in the Armenian variants, the villain of the tale sends the hero to find a bride for him. The girl then betrays the villain and tells the hero the location of his weakness.[84]

In an Armenian tale published originally by Bishop Garegin Srvandztiants in Hamov-Hotov with the name Patikan and Khan Boghou and translated by author Leon Surmelian as Jan-Polad: Steel Monster, the fortieth son of a king, named Patikan, desirous to prove his strength, fights all sorts of devs and giants in his wanderings. One day, he reaches the castle of a being named Jan-Polad, who is «sword-proof, arrow-proof, death-proof». Though the world may fear him, Jan-Polad still longs for a woman’s companionship, and tasks Patikan with getting the being the daughter of the King of the East. Patikan rides to the Kingdom of the East and convinces the monarch he is the one to court his daughter, by performing three difficult tasks. Once he gains the princess, the youth reveals to her she is destined to become Jan-Polad’s wife, but she confesses she has fallen in love with the prince. So, they concoct a plan: the princess shall string along Jan-Polad until he tells her where his true weakness lies. The duo discovers it is in seven little birds, inside a mother-of-pearl box, inside a fox, inside a white bull that grazes in the mountains.[85]

Literary versions[edit]

In a tale titled The Prince and the Silver Rabbit, a king has three daughters. One day, the court astrologer predicts they shall be in great danger, so he orders the building of a wall around the palace. However, in the next weeks, the three princesses disappear one by one, which greatly affects the king and his queen, and they die of grief. The princesses’ brother also falls into a sorrowful state, until he leaves the empty palace one day in pursuit of a silver rabbit. Following the little animal, he is guided to his elder sister’s castle. He is welcomed by her and says her husband is a giant who rules over the antlered creatures of the woods. His first brother-in-law comes and greets him, giving him an ivory horn. The prince follows the rabbit again and visits his middle sister’s castle, where she lives with the giant who ruled the birds of the air. The giant greets him and gives him a bird’s beak as a token. Lastly, he visits his youngest sister and her husband, the ruler of the furry beasts of the forest. He gives him a lock of golden hair. The prince follows the rabbit to a hut, where lives a shoemaker and he learns that the rabbit is the daughter of the Persian King. With the help of the shoemaker, the prince marries the Persian princess, and is given the keys to the palace, with an express order not to open a certain door. Driven by curiosity, he opens the forbidden door and a demon escapes, threatening to take the prince’s wife with him. The next day, the demon comes to take the princess, but the prince tries to delay him enough time to summon his brothers-in-law to help him chain the demon again.[86]

Adaptations[edit]

Peter Morwood wrote an expanded version of this tale in the novel Prince Ivan, the first volume of his Russian Tales series.

Gene Wolfe retold this as «The Death of Koshchei the Deathless», published in the anthology Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears and reprinted in his collection Strange Travelers.

Catherynne M. Valente released a novel based on the story, titled «Deathless» in 2011.

In the 7th Sea tabletop role-playing game setting, Koshchei Molhynia Pietrov, aka Koshchei the Undying is an enigmatic Boyar who entered into a strange contract with the Baba-Yaga-esque Ussuran patron spirit in order to receive a form of immortality. In contrast to the usual myth, he is portrayed in a sympathetic light and seems to be intended to serve (similarly to the Kami, Togashi in the Legend of the Five Rings RPG by the same publishers) as a source of adventure hooks and occasionally a Donor (fairy tale) to whom it is perilous in the extreme to apply.

The Morevna Project, an open-source, free culture film project, is currently[when?] working on an anime-style adaptation of this story set in a cyberpunk science-fiction future[87]

The story was combined with Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf as the plot of Mercedes Lackey’s Firebird, wherein Ilya Ivanovich (son of self-styled Tsar Ivan) encounters Koschei the Deathless and, with the assistance of the titular Firebird, manages to slay him and free the maidens that the sorcerer had kept trapped.

Studio Myrà released a webtoon «Marya Morevna» based on the story in 2021.[88]

See also[edit]

- Bash Chelik

- Bluebeard

- The Fair Fiorita

- The Flower Queen’s Daughter

- The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples

- The Three Enchanted Princes

- The Young King Of Easaidh Ruadh

- Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf

- What Came of Picking Flowers

References[edit]

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Red Fairy Book, «The Death of Koschei the Deathless»

- ^ Vasilisa the Beautiful: Russian Fairytales. Edited by Irina Zheleznova. Moscow: Raduga Publishers. 1984. pp. 152-168.

- ^ Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 55-56. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Anglickienė, Laima. Slavic Folklore: DIDACTICAL GUIDELINES. Kaunas: Vytautas Magnus University, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Cultural Studies and Ethnology. 2013. p. 125. ISBN 978-9955-21-352-9.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Ein Beitrag zur volkskundlichen Balkanologie». In: Fabula 7, no. Jahresband (1965): 8 (footnote nr. 17). https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1965.7.1.1

- ^ The Complete Folktales of A. N. Afanas’ev: Volume I. Edited by Haney Jack V. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. pp. 491-510. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qhm7n.115.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Ein Beitrag zur volkskundlichen Balkanologie». In: Fabula 7, no. Jahresband (1965): 25. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1965.7.1.1

- ^ Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA — Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 8. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Kabakova, Galina. «Baba Yaga dans les louboks». In: Revue Sciences/Lettres [En ligne], 4 | 2016, §30. Mis en ligne le 16 janvier 2016, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rsl/1000 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rsl.1000

- ^ Eesti Muinajutud 1:2 Imemuinasjutud. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeosorglaan. Eesti, Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teadus Kirjastus. 2009. p. 591. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Der Märchentypus AaTh 302 (302 C*) in Mittel- und Osteuropa». In: Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967), pp. 262.

- ^ Eesti Muinajutud 1:2 Imemuinasjutud. Koostanud Risto Järv, Mairi Kaasik, Kärri Toomeosorglaan. Eesti, Tartu: Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Teadus Kirjastus. 2014. p. 719. ISBN 978-9949-544-19-6.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Der Märchentypus AaTh 302 (302 C*) in Mittel- und Osteuropa». In: Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967), pp. 262.

- ^ Degh, Linda. Folktales and Society: Story-telling in a Hungarian Peasant Community. Translated by Emily M. Schossberger. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 1989. p. 352. ISBN 9780253316790.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. «Indexing Folktales: A Critical Survey». In: Journal of Folklore Research 34, no. 3 (1997): 213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3814887.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. 2001. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA — Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 9-10. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Järv, Risto; Kaasik, Mairi; Toomeos-Orglaan, Kärri. Monumenta Estoniae antiquae V. Eesti muinasjutud. I: 1. Imemuinasjutud. Tekstid redigeerinud: Paul Hagu, Kanni Labi. Tartu Ülikooli eesti ja võrdleva rahvaluule osakond, Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Eesti Rahvaluule Arhiiv, 2009. p. 526. ISBN 978-9949-446-47-6.

- ^ Haney, Jack, V. An Anthology of Russian Folktales. London and New York: Routledge. 2015 [2009]. pp. 119-126. ISBN 978-0-7656-2305-8.

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Der Märchentypus AaTh 302 (302 C*) in Mittel- und Osteuropa». In: Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967), pp. 265.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard McGillivray. Modern Greek folktales. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1953. p. 121.

- ^ Афанасьев, А.Н. Поэтические воззрения славян на природу: Опыт сравнительного изучения славянских преданий и верований в связи с мифическими сказаниями других родственных народов. Том 1. Moskva: Izd. K. Soldatenkova 1865. pp. 506-508. (In Russian)

- ^ Дюжев, Ю. И. «Зооморфные персонажи – похитители женщин в русских и прибалтийско-финских волшебных сказках». In: Межкультурные взаимодействия в полиэтничном пространстве пограничного региона: Сборник материалов международной научной конференции. Петрозаводск, 2005. pp. 202-205. ISBN 5-9274-0188-0.

- ^ Frank, R. M. (2019). «Translating a Worldview in the longue durée: The Tale of “The Bear’s Son”». In: Głaz A. (eds). Languages – Cultures – Worldviews. Palgrave Studies in Translating and Interpreting. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp. 68-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28509-8_3

- ^ Матвеева, Р. П. (2013). Русские сказки на сюжет «Три подземных царства» в сибирском репертуаре. Вестник Бурятского государственного университета. Педагогика. Филология. Философия, (10), 170-175. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/russkie-skazki-na-syuzhet-tri-podzemnyh-tsarstva-v-sibirskom-repertuare (дата обращения: 17.02.2021).

- ^ «ИВАН ВДОВИН» [Ivan, Widow’s Son]. In: Бурятские волшебные сказки / Отв. ред. тома А. Б. Соктоев. Новосибирск: Наука, 1993. pp. 116-124, 288. (Памятники фольклора народов Сибири и Дальнего Востока; Т. 5).

- ^ Ting, Nai-tung. «AT Type 301 in China and Some Countries Adjacent to China: A Study of a Regional Group and its Significance in World Tradition». In: Fabula 11, no. Jahresband (1970): 57, 60-61. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1970.11.1.54

- ^ Johns, Andreas. Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. 2010 [2004]. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6

- ^ Sherman, Josepha (2008). Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. Sharpe Reference. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7656-8047-1

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- ^ Frazer, James George, Sir. The Golden Bough: a Study In Comparative Religion. Vol. II. London: Macmillan, 1890. pp. 296-326. [1]

- ^ Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA — Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 9. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

- ^ Montalba, Anthony Reubens. Fairy Tales From All Nations. New York: Harper, 1850. pp. 20-37.

- ^ Mailath, Johann Grafen. Magyarische Sagen, Mährchen und Erzählungen. Zweiter Band. Stuttgart und Tübingen: Verlag der J. G. Cotta’schen Buchhandlung. 1837. pp. 23-37. [2]

- ^ Mailáth, Johann. Magyarische Sagen und Mährchen. Trassler. 1825. pp. 257-272.

- ^ Jones, W. Henry; Kropf, Lajos L.; Kriza, János. The folk-tales of the Magyars. London: Pub. for the Folk-lore society by E. Stock. 1889. pp. 345-346.

- ^ Molbech, Christian. Udvalgte Eventyr Eller Folkedigtninger: En Bog for Ungdommen, Folket Og Skolen. 2., giennemseete og forøgede udgave. Unden Deel. Kiøbenhavn: Reitzel, 1854. pp. 200-213. [3]

- ^ Degh, Linda. Folktales and Society: Story-telling in a Hungarian Peasant Community. Translated by Emily M. Schossberger. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 1989. p. 353. ISBN 9780253316790.

- ^ Kovács Attila Zoltán. A gyöngyszemet hullató leány. Budapest: Móra Ferenc Könyvkiadó. 2004. pp. 53-61.

- ^ The Ruby fairy book. Comprising stories by Jules Le Maitre, J. Wenzig, Flora Schmals, F.C. Younger, Luigi Capuani, John C. Winder, Canning Williams, Daniel Riche and others; with 78 illustrations by H.R. Millar. London: Hutchinson & Co. [1900] pp. 209-223.

- ^ Худяков, Иван Александрович. «Великорусскія сказки». Вып. 1. М.: Издание К. Солдатенкова и Н. Щепкина, 1860. pp. 77—89. [4]

- ^ Худяков, Иван Александрович. «Великорусскія сказки». Вып. 2. М.: Издание К. Солдатенкова и Н. Щепкина, 1861. pp. 87—100.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. Long, Long Tales from the Russian North. University Press of Mississippi, 2013. p. 298. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/23487.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. Long, Long Tales from the Russian North. University Press of Mississippi, 2013. p. xxi. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/23487.

- ^ Haney, Jack V. Long, Long Tales from the Russian North. University Press of Mississippi, 2013. pp. 281-296. DOI: 10.14325/mississippi/9781617037306.003.0017

- ^ Haney, Jack, V. An Anthology of Russian Folktales. London and New York: Routledge. 2015 [2009]. pp. 119-126. ISBN 978-0-7656-2305-8.

- ^ Акцорин, Виталий. «Марийские народные сказки» [Mari Folk Tales]. Йошкар-Ола: Марийское книжное издательство, 1984. pp. 55-66.

- ^ Ariste, Paul (2005). Komi Folklore. Collected by P. Ariste. Vol. 1. Edited by Nikolay Kuznetsov. Tartu: Dept. of Folkloristics, Estonian Literary Museum. pp. 134-149 (entry nr. 121). Available at: http://www.folklore.ee/rl/pubte/ee/ariste/komi.

- ^ Karig Sára. Mese a tölgyfa tetején: Csuvas mesék. Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó, 1977. pp. 46-56.

- ^ «Чувашские легенды и сказки» [Chuvash legends and fairy tales]. Chuvashskoe knizh. izd-vo, 1979. pp. 133-137.

- ^ Романов, Е. Р. Белорусский сборник. Вып. 6: Сказки. Е. Р. Романов. Могилев: Типография Губернского правления, 1901. pp. 213-224.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Der Märchentypus AaTh 302 (302 C*) in Mittel- und Osteuropa». In: Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967), pp. 267.

- ^ Романов, Е. Р. Белорусский сборник. Вып. 6: Сказки. Е. Р. Романов. Могилев: Типография Губернского правления, 1901. pp. 233-244.

- ^ Horálek, Karel. «Der Märchentypus AaTh 302 (302 C*) in Mittel- und Osteuropa». In: Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967), pp. 267.

- ^ Barag, Lev. Belorussische Volksmärchen. Akademie-Verlag, 1966. pp. 264-273.