Как назывался первый сборник рассказов Джека Лондона?

«Внук опоссума»? «Дочь обезьяны»? «Братец кролика»? «Сын волка»?

4

«Внук опоссума»

«Дочь обезьяны»

«Братец кролика»

«Сын волка»

#Литература

#Сложность: 20

#Пандарина

Похожие вопросы

Какое было прозвище у брата Волка Ларсена из романа Джека Лондона «Морской волк»?

#Литература

#Сложность: 1500

#Пандарина

Как назывался первый сборник рассказов А. П. Чехова, вышедший в свет в 1884 году?

#Сложность: 10000

#Пандарина

В каком рассказе Джека Лондона главный герой проводил эксперименты на собственном сыне?

#Сложность: 400

#Пандарина

Как назывался первый сборник рассказов А. П. Чехова, изданный в 1884 году?

#Сложность: 10000

#Пандарина

Случайные вопросы

Из чего состоят алмазы?

#Универ: Прокачай общагу!

Каким праздником на Руси заканчивался купальный сезон?

#Праздники

#Сложность: 400

#Пандарина

Самый известный фильм Джеймса Кэмерона?

#100 к 1

Какой марш есть среди произведений Моцарта?

#Сложность: 100

#Пандарина

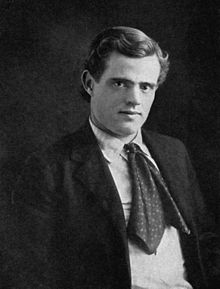

|

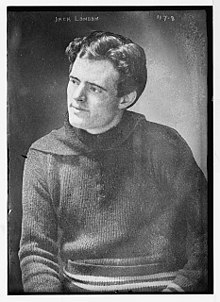

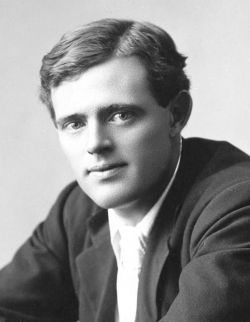

Jack London |

|

|---|---|

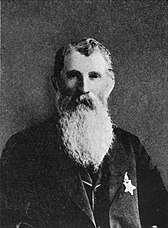

London in 1903 |

|

| Born | John Griffith Chaney January 12, 1876 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | November 22, 1916 (aged 40) Glen Ellen, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Literary movement | Realism, Naturalism |

| Notable works | The Call of the Wild White Fang |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Maddern (m. ; div. ) Charmian Kittredge (m. 1905) |

| Children | Joan London Bessie London |

| Signature | |

John Griffith Chaney[1] (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London,[2][3][4][5] was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to become an international celebrity and earn a large fortune from writing.[6] He was also an innovator in the genre that would later become known as science fiction.[7]

London was part of the radical literary group «The Crowd» in San Francisco and a passionate advocate of animal rights, workers’ rights and socialism.[8][9] London wrote several works dealing with these topics, such as his dystopian novel The Iron Heel, his non-fiction exposé The People of the Abyss, War of the Classes, and Before Adam.

His most famous works include The Call of the Wild and White Fang, both set in Alaska and the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush, as well as the short stories «To Build a Fire», «An Odyssey of the North», and «Love of Life». He also wrote about the South Pacific in stories such as «The Pearls of Parlay», and «The Heathen».

Family

Flora and John London, Jack’s mother and stepfather

Jack London was born January 12, 1876.[10] His mother, Flora Wellman, was the fifth and youngest child of Pennsylvania Canal builder Marshall Wellman and his first wife, Eleanor Garrett Jones. Marshall Wellman was descended from Thomas Wellman, an early Puritan settler in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[11] Flora left Ohio and moved to the Pacific coast when her father remarried after her mother died. In San Francisco, Flora worked as a music teacher and spiritualist, claiming to channel the spirit of a Sauk chief, Black Hawk.[12][clarification needed]

Biographer Clarice Stasz and others believe London’s father was astrologer William Chaney.[13] Flora Wellman was living with Chaney in San Francisco when she became pregnant. Whether Wellman and Chaney were legally married is unknown. Stasz notes that in his memoirs, Chaney refers to London’s mother Flora Wellman as having been «his wife»; he also cites an advertisement in which Flora called herself «Florence Wellman Chaney».[14]

According to Flora Wellman’s account, as recorded in the San Francisco Chronicle of June 4, 1875, Chaney demanded that she have an abortion. When she refused, he disclaimed responsibility for the child. In desperation, she shot herself. She was not seriously wounded, but she was temporarily deranged. After giving birth, Flora sent the baby for wet-nursing to Virginia (Jennie) Prentiss, a formerly enslaved African-American woman and a neighbor. Prentiss was an important maternal figure throughout London’s life, and he would later refer to her as his primary source of love and affection as a child.[15]

Late in 1876, Flora Wellman married John London, a partially disabled Civil War veteran, and brought her baby John, later known as Jack, to live with the newly married couple. The family moved around the San Francisco Bay Area before settling in Oakland, where London completed public grade school. The Prentiss family moved with the Londons, and remained a stable source of care for the young Jack.[15]

In 1897, when he was 21 and a student at the University of California, Berkeley, London searched for and read the newspaper accounts of his mother’s suicide attempt and the name of his biological father. He wrote to William Chaney, then living in Chicago. Chaney responded that he could not be London’s father because he was impotent; he casually asserted that London’s mother had relations with other men and averred that she had slandered him when she said he insisted on an abortion. Chaney concluded by saying that he was more to be pitied than London.[16] London was devastated by his father’s letter; in the months following, he quit school at Berkeley and went to the Klondike during the gold rush boom.

Early life

London at the age of nine with his dog Rollo, 1885

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; the California Historical Society placed a plaque at the site in 1953. Although the family was working class, it was not as impoverished as London’s later accounts claimed.[citation needed] London was largely self-educated.[citation needed]

In 1885, London found and read Ouida’s long Victorian novel Signa.[17][18] He credited this as the seed of his literary success.[19] In 1886, he went to the Oakland Public Library and found a sympathetic librarian, Ina Coolbrith, who encouraged his learning. (She later became California’s first poet laureate and an important figure in the San Francisco literary community).[20]

In 1889, London began working 12 to 18 hours a day at Hickmott’s Cannery. Seeking a way out, he borrowed money from his foster mother Virginia Prentiss, bought the sloop Razzle-Dazzle from an oyster pirate named French Frank, and became an oyster pirate himself. In his memoir, John Barleycorn, he claims also to have stolen French Frank’s mistress Mamie.[21][22][23] After a few months, his sloop became damaged beyond repair. London hired on as a member of the California Fish Patrol.

In 1893, he signed on to the sealing schooner Sophie Sutherland, bound for the coast of Japan. When he returned, the country was in the grip of the panic of ’93 and Oakland was swept by labor unrest. After grueling jobs in a jute mill and a street-railway power plant, London joined Coxey’s Army and began his career as a tramp. In 1894, he spent 30 days for vagrancy in the Erie County Penitentiary at Buffalo, New York. In The Road, he wrote:

Man-handling was merely one of the very minor unprintable horrors of the Erie County Pen. I say ‘unprintable’; and in justice I must also say undescribable. They were unthinkable to me until I saw them, and I was no spring chicken in the ways of the world and the awful abysses of human degradation. It would take a deep plummet to reach bottom in the Erie County Pen, and I do but skim lightly and facetiously the surface of things as I there saw them.

— Jack London, The Road

After many experiences as a hobo and a sailor, he returned to Oakland and attended Oakland High School. He contributed a number of articles to the high school’s magazine, The Aegis. His first published work was «Typhoon off the Coast of Japan», an account of his sailing experiences.[24]

Jack London studying at Heinold’s First and Last Chance in 1886

As a schoolboy, London often studied at Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon, a port-side bar in Oakland. At 17, he confessed to the bar’s owner, John Heinold, his desire to attend university and pursue a career as a writer. Heinold lent London tuition money to attend college.

London desperately wanted to attend the University of California, located in Berkeley. In 1896, after a summer of intense studying to pass certification exams, he was admitted. Financial circumstances forced him to leave in 1897, and he never graduated. No evidence has surfaced that he ever wrote for student publications while studying at Berkeley.[25]

Heinold’s First and Last Chance, «Jack London’s Rendezvous»

While at Berkeley, London continued to study and spend time at Heinold’s saloon, where he was introduced to the sailors and adventurers who would influence his writing. In his autobiographical novel, John Barleycorn, London mentioned the pub’s likeness seventeen times. Heinold’s was the place where London met Alexander McLean, a captain known for his cruelty at sea.[26] London based his protagonist Wolf Larsen, in the novel The Sea-Wolf, on McLean.[27]

Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon is now unofficially named Jack London’s Rendezvous in his honor.[28]

Gold rush and first success

On July 12, 1897, London (age 21) and his sister’s husband Captain Shepard sailed to join the Klondike Gold Rush. This was the setting for some of his first successful stories. London’s time in the harsh Klondike, however, was detrimental to his health. Like so many other men who were malnourished in the goldfields, London developed scurvy. His gums became swollen, leading to the loss of his four front teeth. A constant gnawing pain affected his hip and leg muscles, and his face was stricken with marks that always reminded him of the struggles he faced in the Klondike. Father William Judge, «The Saint of Dawson», had a facility in Dawson that provided shelter, food and any available medicine to London and others. His struggles there inspired London’s short story, «To Build a Fire» (1902, revised in 1908),[A] which many critics assess as his best.[citation needed]

His landlords in Dawson were mining engineers Marshall Latham Bond and Louis Whitford Bond, educated at the Bachelor’s level at the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale and at the Master’s level at Stanford, respectively. The brothers’ father, Judge Hiram Bond, was a wealthy mining investor. While the Bond brothers were at Stanford, Hiram at the suggestion of his brother bought the New Park Estate at Santa Clara as well as a local bank. The Bonds, especially Hiram, were active Republicans. Marshall Bond’s diary mentions friendly sparring with London on political issues as a camp pastime.[citation needed]

London left Oakland with a social conscience and socialist leanings; he returned to become an activist for socialism. He concluded that his only hope of escaping the work «trap» was to get an education and «sell his brains». He saw his writing as a business, his ticket out of poverty and, he hoped, as a means of beating the wealthy at their own game.

On returning to California in 1898, London began working to get published, a struggle described in his novel Martin Eden (serialized in 1908, published in 1909). His first published story since high school was «To the Man On Trail», which has frequently been collected in anthologies.[citation needed] When The Overland Monthly offered him only five dollars for it—and was slow paying—London came close to abandoning his writing career. In his words, «literally and literarily I was saved» when The Black Cat accepted his story «A Thousand Deaths» and paid him $40—the «first money I ever received for a story».[citation needed]

London began his writing career just as new printing technologies enabled lower-cost production of magazines. This resulted in a boom in popular magazines aimed at a wide public audience and a strong market for short fiction.[citation needed] In 1900, he made $2,500 in writing, about $81,000 in today’s currency.[citation needed]

Among the works he sold to magazines was a short story known as either «Diable» (1902) or «Bâtard» (1904), two editions of the same basic story. London received $141.25 for this story on May 27, 1902.[29] In the text, a cruel French Canadian brutalizes his dog, and the dog retaliates and kills the man. London told some of his critics that man’s actions are the main cause of the behavior of their animals, and he would show this famously in another story, The Call of the Wild.[30]

In early 1903, London sold The Call of the Wild to The Saturday Evening Post for $750 and the book rights to Macmillan. Macmillan’s promotional campaign propelled it to swift success.[31]

While living at his rented villa on Lake Merritt in Oakland, California, London met poet George Sterling; in time they became best friends. In 1902, Sterling helped London find a home closer to his own in nearby Piedmont. In his letters London addressed Sterling as «Greek», owing to Sterling’s aquiline nose and classical profile, and he signed them as «Wolf». London was later to depict Sterling as Russ Brissenden in his autobiographical novel Martin Eden (1910) and as Mark Hall in The Valley of the Moon (1913).[citation needed]

In later life London indulged his wide-ranging interests by accumulating a personal library of 15,000 volumes. He referred to his books as «the tools of my trade».[32]

First marriage (1900–1904)

Jack with daughters Becky (left) and Joan (right)

Bessie Maddern London and daughters, Joan and Becky

London married Elizabeth Mae (or May) «Bessie» Maddern on April 7, 1900, the same day The Son of the Wolf was published. Bess had been part of his circle of friends for a number of years. She was related to stage actresses Minnie Maddern Fiske and Emily Stevens. Stasz says, «Both acknowledged publicly that they were not marrying out of love, but from friendship and a belief that they would produce sturdy children.»[33] Kingman says, «they were comfortable together… Jack had made it clear to Bessie that he did not love her, but that he liked her enough to make a successful marriage.»[34]

London met Bessie through his friend at Oakland High School, Fred Jacobs; she was Fred’s fiancée. Bessie, who tutored at Anderson’s University Academy in Alameda California, tutored Jack in preparation for his entrance exams for the University of California at Berkeley in 1896. Jacobs was killed aboard the Scandia in 1897, but Jack and Bessie continued their friendship, which included taking photos and developing the film together.[35] This was the beginning of Jack’s passion for photography.

During the marriage, London continued his friendship with Anna Strunsky, co-authoring The Kempton-Wace Letters, an epistolary novel contrasting two philosophies of love. Anna, writing «Dane Kempton’s» letters, arguing for a romantic view of marriage, while London, writing «Herbert Wace’s» letters, argued for a scientific view, based on Darwinism and eugenics. In the novel, his fictional character contrasted two women he had known.[citation needed]

London’s pet name for Bess was «Mother-Girl» and Bess’s for London was «Daddy-Boy».[36] Their first child, Joan, was born on January 15, 1901, and their second, Bessie «Becky» (also reported as Bess), on October 20, 1902. Both children were born in Piedmont, California. Here London wrote one of his most celebrated works, The Call of the Wild.

While London had pride in his children, the marriage was strained. Kingman says that by 1903 the couple were close to separation as they were «extremely incompatible». «Jack was still so kind and gentle with Bessie that when Cloudsley Johns was a house guest in February 1903 he didn’t suspect a breakup of their marriage.»[37]

London reportedly complained to friends Joseph Noel and George Sterling:

[Bessie] is devoted to purity. When I tell her morality is only evidence of low blood pressure, she hates me. She’d sell me and the children out for her damned purity. It’s terrible. Every time I come back after being away from home for a night she won’t let me be in the same room with her if she can help it.[38]

Stasz writes that these were «code words for [Bess’s] fear that [Jack] was consorting with prostitutes and might bring home venereal disease.»[39]

On July 24, 1903, London told Bessie he was leaving and moved out. During 1904, London and Bess negotiated the terms of a divorce, and the decree was granted on November 11, 1904.[40]

War correspondent (1904)

London accepted an assignment of the San Francisco Examiner to cover the Russo-Japanese War in early 1904, arriving in Yokohama on January 25, 1904. He was arrested by Japanese authorities in Shimonoseki, but released through the intervention of American ambassador Lloyd Griscom. After travelling to Korea, he was again arrested by Japanese authorities for straying too close to the border with Manchuria without official permission, and was sent back to Seoul. Released again, London was permitted to travel with the Imperial Japanese Army to the border, and to observe the Battle of the Yalu.

London asked William Randolph Hearst, the owner of the San Francisco Examiner, to be allowed to transfer to the Imperial Russian Army, where he felt that restrictions on his reporting and his movements would be less severe. However, before this could be arranged, he was arrested for a third time in four months, this time for assaulting his Japanese assistants, whom he accused of stealing the fodder for his horse. Released through the personal intervention of President Theodore Roosevelt, London departed the front in June 1904.[41]

Bohemian Club

On August 18, 1904, London went with his close friend, the poet George Sterling, to «Summer High Jinks» at the Bohemian Grove. London was elected to honorary membership in the Bohemian Club and took part in many activities. Other noted members of the Bohemian Club during this time included Ambrose Bierce, Gelett Burgess, Allan Dunn, John Muir, Frank Norris,[citation needed] and Herman George Scheffauer.

Beginning in December 1914, London worked on The Acorn Planter, A California Forest Play, to be performed as one of the annual Grove Plays, but it was never selected. It was described as too difficult to set to music.[42] London published The Acorn Planter in 1916.[43]

Second marriage

Jack and Charmian London (c. 1915) at Waikiki

After divorcing Maddern, London married Charmian Kittredge in 1905. London had been introduced to Kittredge in 1900 by her aunt Netta Eames, who was an editor at Overland Monthly magazine in San Francisco. The two met prior to his first marriage but became lovers years later after Jack and Bessie London visited Wake Robin, Netta Eames’ Sonoma County resort, in 1903. London was injured when he fell from a buggy, and Netta arranged for Charmian to care for him. The two developed a friendship, as Charmian, Netta, her husband Roscoe, and London were politically aligned with socialist causes. At some point the relationship became romantic, and Jack divorced his wife to marry Charmian, who was five years his senior.[44]

Biographer Russ Kingman called Charmian «Jack’s soul-mate, always at his side, and a perfect match.» Their time together included numerous trips, including a 1907 cruise on the yacht Snark to Hawaii and Australia.[45] Many of London’s stories are based on his visits to Hawaii, the last one for 10 months beginning in December 1915.[46]

The couple also visited Goldfield, Nevada, in 1907, where they were guests of the Bond brothers, London’s Dawson City landlords. The Bond brothers were working in Nevada as mining engineers.

London had contrasted the concepts of the «Mother Girl» and the «Mate Woman» in The Kempton-Wace Letters. His pet name for Bess had been «Mother-Girl;» his pet name for Charmian was «Mate-Woman.»[47] Charmian’s aunt and foster mother, a disciple of Victoria Woodhull, had raised her without prudishness.[48] Every biographer alludes to Charmian’s uninhibited sexuality.[49][50]

The Snark in Australia, 1921

Joseph Noel calls the events from 1903 to 1905 «a domestic drama that would have intrigued the pen of an Ibsen…. London’s had comedy relief in it and a sort of easy-going romance.»[51] In broad outline, London was restless in his first marriage, sought extramarital sexual affairs, and found, in Charmian Kittredge, not only a sexually active and adventurous partner, but his future life-companion. They attempted to have children; one child died at birth, and another pregnancy ended in a miscarriage.[52]

In 1906, London published in Collier’s magazine his eye-witness report of the San Francisco earthquake.[53]

Beauty Ranch (1905–1916)

In 1905, London purchased a 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) ranch in Glen Ellen, Sonoma County, California, on the eastern slope of Sonoma Mountain.[54] He wrote: «Next to my wife, the ranch is the dearest thing in the world to me.» He desperately wanted the ranch to become a successful business enterprise. Writing, always a commercial enterprise with London, now became even more a means to an end: «I write for no other purpose than to add to the beauty that now belongs to me. I write a book for no other reason than to add three or four hundred acres to my magnificent estate.»

Stasz writes that London «had taken fully to heart the vision, expressed in his agrarian fiction, of the land as the closest earthly version of Eden … he educated himself through the study of agricultural manuals and scientific tomes. He conceived of a system of ranching that today would be praised for its ecological wisdom.»[citation needed] He was proud to own the first concrete silo in California. He hoped to adapt the wisdom of Asian sustainable agriculture to the United States. He hired both Italian and Chinese stonemasons, whose distinctly different styles are obvious.

The ranch was an economic failure. Sympathetic observers such as Stasz treat his projects as potentially feasible, and ascribe their failure to bad luck or to being ahead of their time. Unsympathetic historians such as Kevin Starr suggest that he was a bad manager, distracted by other concerns and impaired by his alcoholism. Starr notes that London was absent from his ranch about six months a year between 1910 and 1916 and says, «He liked the show of managerial power, but not grinding attention to detail …. London’s workers laughed at his efforts to play big-time rancher [and considered] the operation a rich man’s hobby.»[55]

London spent $80,000 ($2,410,000 in current value) to build a 15,000-square-foot (1,400 m2) stone mansion called Wolf House on the property. Just as the mansion was nearing completion, two weeks before the Londons planned to move in, it was destroyed by fire.

London’s last visit to Hawaii,[56] beginning in December 1915, lasted eight months. He met with Duke Kahanamoku, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana’ole, Queen Lili’uokalani and many others, before returning to his ranch in July 1916.[46] He was suffering from kidney failure, but he continued to work.

The ranch (abutting stone remnants of Wolf House) is now a National Historic Landmark and is protected in Jack London State Historic Park.

Animal activism

London witnessed animal cruelty in the training of circus animals, and his subsequent novels Jerry of the Islands and Michael, Brother of Jerry included a foreword entreating the public to become more informed about this practice.[57] In 1918, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the American Humane Education Society teamed up to create the Jack London Club, which sought to inform the public about cruelty to circus animals and encourage them to protest this establishment.[58] Support from Club members led to a temporary cessation of trained animal acts at Ringling-Barnum and Bailey in 1925.[59]

Death

Grave of Jack and Charmian London

London died November 22, 1916, in a sleeping porch in a cottage on his ranch. London had been a robust man but had suffered several serious illnesses, including scurvy in the Klondike.[60] Additionally, during travels on the Snark, he and Charmian picked up unspecified tropical infections and diseases, including yaws.[61] At the time of his death, he suffered from dysentery, late-stage alcoholism, and uremia;[62] he was in extreme pain and taking morphine and opium, both common, over-the-counter drugs at the time.[63]

London’s ashes were buried on his property not far from the Wolf House. London’s funeral took place on November 26, 1916, attended only by close friends, relatives, and workers of the property. In accordance with his wishes, he was cremated and buried next to some pioneer children, under a rock that belonged to the Wolf House. After Charmian’s death in 1955, she was also cremated and then buried with her husband in the same spot that her husband chose. The grave is marked by a mossy boulder. The buildings and property were later preserved as Jack London State Historic Park, in Glen Ellen, California.

Suicide debate

Because he was using morphine, many older sources describe London’s death as a suicide, and some still do.[64] This conjecture appears to be a rumor, or speculation based on incidents in his fiction writings. His death certificate[65] gives the cause as uremia, following acute renal colic.

The biographer Stasz writes, «Following London’s death, for a number of reasons, a biographical myth developed in which he has been portrayed as an alcoholic womanizer who committed suicide. Recent scholarship based upon firsthand documents challenges this caricature.»[66] Most biographers, including Russ Kingman, now agree he died of uremia aggravated by an accidental morphine overdose.[67]

London’s fiction featured several suicides. In his autobiographical memoir John Barleycorn, he claims, as a youth, to have drunkenly stumbled overboard into the San Francisco Bay, «some maundering fancy of going out with the tide suddenly obsessed me». He said he drifted and nearly succeeded in drowning before sobering up and being rescued by fishermen. In the dénouement of The Little Lady of the Big House, the heroine, confronted by the pain of a mortal gunshot wound, undergoes a physician-assisted suicide by morphine. Also, in Martin Eden, the principal protagonist, who shares certain characteristics with London,[68] drowns himself.[69][citation needed]

Plagiarism accusations

London in his office, 1916

London was vulnerable to accusations of plagiarism, both because he was such a conspicuous, prolific, and successful writer and because of his methods of working. He wrote in a letter to Elwyn Hoffman, «expression, you see—with me—is far easier than invention.» He purchased plots and novels from the young Sinclair Lewis[70] and used incidents from newspaper clippings as writing material.[citation needed]

In July 1901, two pieces of fiction appeared within the same month: London’s «Moon-Face», in the San Francisco Argonaut, and Frank Norris’ «The Passing of Cock-eye Blacklock», in Century Magazine. Newspapers showed the similarities between the stories, which London said were «quite different in manner of treatment, [but] patently the same in foundation and motive.»[71] London explained both writers based their stories on the same newspaper account. A year later, it was discovered that Charles Forrest McLean had published a fictional story also based on the same incident.[72]

Egerton Ryerson Young[73][74] claimed The Call of the Wild (1903) was taken from Young’s book My Dogs in the Northland (1902). London acknowledged using it as a source and claimed to have written a letter to Young thanking him.[75]

In 1906, the New York World published «deadly parallel» columns showing eighteen passages from London’s short story «Love of Life» side by side with similar passages from a nonfiction article by Augustus Biddle and J. K. Macdonald, titled «Lost in the Land of the Midnight Sun».[76] London noted the World did not accuse him of «plagiarism», but only of «identity of time and situation», to which he defiantly «pled guilty».[77]

The most serious charge of plagiarism was based on London’s «The Bishop’s Vision», Chapter 7 of his novel The Iron Heel (1908). The chapter is nearly identical to an ironic essay that Frank Harris published in 1901, titled «The Bishop of London and Public Morality».[78] Harris was incensed and suggested he should receive 1/60th of the royalties from The Iron Heel, the disputed material constituting about that fraction of the whole novel. London insisted he had clipped a reprint of the article, which had appeared in an American newspaper, and believed it to be a genuine speech delivered by the Bishop of London.[citation needed]

Views

Atheism

London was an atheist.[79] He is quoted as saying, «I believe that when I am dead, I am dead. I believe that with my death I am just as much obliterated as the last mosquito you and I squashed.»[80]

London wrote from a socialist viewpoint, which is evident in his novel The Iron Heel. Neither a theorist nor an intellectual socialist, London’s socialism grew out of his life experience. As London explained in his essay, «How I Became a Socialist»,[81] his views were influenced by his experience with people at the bottom of the social pit. His optimism and individualism faded, and he vowed never to do more hard physical work than necessary. He wrote that his individualism was hammered out of him, and he was politically reborn. He often closed his letters «Yours for the Revolution.»[82]

London joined the Socialist Labor Party in April 1896. In the same year, the San Francisco Chronicle published a story about the twenty-year-old London’s giving nightly speeches in Oakland’s City Hall Park, an activity he was arrested for a year later. In 1901, he left the Socialist Labor Party and joined the new Socialist Party of America. He ran unsuccessfully as the high-profile Socialist candidate for mayor of Oakland in 1901 (receiving 245 votes) and 1905 (improving to 981 votes), toured the country lecturing on socialism in 1906, and published two collections of essays about socialism: War of the Classes (1905) and Revolution, and other Essays (1906).

Stasz notes that «London regarded the Wobblies as a welcome addition to the Socialist cause, although he never joined them in going so far as to recommend sabotage.»[83] Stasz mentions a personal meeting between London and Big Bill Haywood in 1912.[84]

In his late (1913) book The Cruise of the Snark, London writes about appeals to him for membership of the Snark’s crew from office workers and other «toilers» who longed for escape from the cities, and of being cheated by workmen.

In his Glen Ellen ranch years, London felt some ambivalence toward socialism and complained about the «inefficient Italian labourers» in his employ.[85] In 1916, he resigned from the Glen Ellen chapter of the Socialist Party, but stated emphatically he did so «because of its lack of fire and fight, and its loss of emphasis on the class struggle.» In an unflattering portrait of London’s ranch days, California cultural historian Kevin Starr refers to this period as «post-socialist» and says «… by 1911 … London was more bored by the class struggle than he cared to admit.»[86]

Race

Jeffries (left) vs. Johnson, 1910

London shared common concerns among many European Americans in California about Asian immigration, described as «the yellow peril»; he used the latter term as the title of a 1904 essay.[87] This theme was also the subject of a story he wrote in 1910 called «The Unparalleled Invasion». Presented as an historical essay set in the future, the story narrates events between 1976 and 1987, in which China, with an ever-increasing population, is taking over and colonizing its neighbors with the intention of taking over the entire Earth. The western nations respond with biological warfare and bombard China with dozens of the most infectious diseases.[88] On his fears about China, he admits (at the end of «The Yellow Peril»), «it must be taken into consideration that the above postulate is itself a product of Western race-egotism, urged by our belief in our own righteousness and fostered by a faith in ourselves which may be as erroneous as are most fond race fancies.»

By contrast, many of London’s short stories are notable for their empathetic portrayal of Mexican («The Mexican»), Asian («The Chinago»), and Hawaiian («Koolau the Leper») characters. London’s war correspondence from the Russo-Japanese War, as well as his unfinished novel Cherry, show he admired much about Japanese customs and capabilities.[89] London’s writings have been popular among the Japanese, who believe he portrayed them positively.[15]

In «Koolau the Leper», London describes Koolau, who is a Hawaiian leper—and thus a very different sort of «superman» than Martin Eden—and who fights off an entire cavalry troop to elude capture, as «indomitable spiritually—a … magnificent rebel». This character is based on Hawaiian leper Kaluaikoolau, who in 1893 revolted and resisted capture from forces of the Provisional Government of Hawaii in the Kalalau Valley.

Those who defend London against charges of racism cite the letter he wrote to the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly in 1913:

In reply to yours of August 16, 1913. First of all, I should say by stopping the stupid newspaper from always fomenting race prejudice. This of course, being impossible, I would say, next, by educating the people of Japan so that they will be too intelligently tolerant to respond to any call to race prejudice. And, finally, by realizing, in industry and government, of socialism—which last word is merely a word that stands for the actual application of in the affairs of men of the theory of the Brotherhood of Man.

In the meantime the nations and races are only unruly boys who have not yet grown to the stature of men. So we must expect them to do unruly and boisterous things at times. And, just as boys grow up, so the races of mankind will grow up and laugh when they look back upon their childish quarrels.[90]

In 1996, after the City of Whitehorse, Yukon, renamed a street in honor of London, protests over London’s alleged racism forced the city to change the name of «Jack London Boulevard»[failed verification] back to «Two-mile Hill».[91]

Shortly after boxer Jack Johnson was crowned the first black world heavyweight champ in 1908, London pleaded for a «great white hope» to come forward to defeat Johnson, writing: «Jim Jeffries must now emerge from his Alfalfa farm and remove that golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you. The White Man must be rescued.»[92]

Eugenics

With other modernist writers of the day,[93] London supported eugenics.[8] The notion of «good breeding» complemented the Progressive era scientism, the belief that humans assort along a hierarchy by race, religion, and ethnicity. The Progressive Era catalog of inferiority offered basis for threats to American Anglo-Saxon racial integrity. London wrote to Frederick H. Robinson of the periodical Medical Review of Reviews, stating, «I believe the future belongs to eugenics, and will be determined by the practice of eugenics.»[94] Although this led some to argue for forced sterilization of criminals or those deemed feeble-minded.,[95] London did not express this extreme. His short story «Told in the Drooling Ward» is from the viewpoint of a surprisingly astute «feebled-minded» person.

Hensley argues that London’s novel Before Adam (1906–07) reveals pro-eugenic themes.[9] London advised his collaborator Anna Strunsky during preparation of The Kempton-Wace Letters that he would take the role of eugenics in mating, while she would argue on behalf of romantic love. (Love won the argument.) [96] The Valley of the Moon emphasizes the theme of «real Americans,» the Anglo Saxon, yet in Little Lady of the Big House, London is more nuanced. The protagonist’s argument is not that all white men are superior, but that there are more superior ones among whites than in other races. By encouraging the best in any race to mate will improve its population qualities.[97] Living in Hawaii challenged his orthodoxy. In «My Hawaiian Aloha,» London noted the liberal intermarrying of races, concluding how «little Hawaii, with its hotch potch races, is making a better demonstration than the United States.»[98]

Works

Short stories

Jack London (date unknown)

Western writer and historian Dale L. Walker writes:[99]

London’s true métier was the short story … London’s true genius lay in the short form, 7,500 words and under, where the flood of images in his teeming brain and the innate power of his narrative gift were at once constrained and freed. His stories that run longer than the magic 7,500 generally—but certainly not always—could have benefited from self-editing.

London’s «strength of utterance» is at its height in his stories, and they are painstakingly well-constructed.[citation needed] «To Build a Fire» is the best known of all his stories. Set in the harsh Klondike, it recounts the haphazard trek of a new arrival who has ignored an old-timer’s warning about the risks of traveling alone. Falling through the ice into a creek in seventy-five-below weather, the unnamed man is keenly aware that survival depends on his untested skills at quickly building a fire to dry his clothes and warm his extremities. After publishing a tame version of this story—with a sunny outcome—in The Youth’s Companion in 1902, London offered a second, more severe take on the man’s predicament in The Century Magazine in 1908. Reading both provides an illustration of London’s growth and maturation as a writer. As Labor (1994) observes: «To compare the two versions is itself an instructive lesson in what distinguished a great work of literary art from a good children’s story.»[A]

Other stories from the Klondike period include: «All Gold Canyon», about a battle between a gold prospector and a claim jumper; «The Law of Life», about an aging American Indian man abandoned by his tribe and left to die; «Love of Life», about a trek by a prospector across the Canadian tundra; «To the Man on Trail,» which tells the story of a prospector fleeing the Mounted Police in a sled race, and raises the question of the contrast between written law and morality; and «An Odyssey of the North,» which raises questions of conditional morality, and paints a sympathetic portrait of a man of mixed White and Aleut ancestry.

London was a boxing fan and an avid amateur boxer. «A Piece of Steak» is a tale about a match between older and younger boxers. It contrasts the differing experiences of youth and age but also raises the social question of the treatment of aging workers. «The Mexican» combines boxing with a social theme, as a young Mexican endures an unfair fight and ethnic prejudice to earn money with which to aid the revolution.

Several of London’s stories would today be classified as science fiction. «The Unparalleled Invasion» describes germ warfare against China; «Goliath» is about an irresistible energy weapon; «The Shadow and the Flash» is a tale about two brothers who take different routes to achieving invisibility; «A Relic of the Pliocene» is a tall tale about an encounter of a modern-day man with a mammoth. «The Red One» is a late story from a period when London was intrigued by the theories of the psychiatrist and writer Jung. It tells of an island tribe held in thrall by an extraterrestrial object.

Some nineteen original collections of short stories were published during London’s brief life or shortly after his death. There have been several posthumous anthologies drawn from this pool of stories. Many of these stories were located in the Klondike and the Pacific. A collection of Jack London’s San Francisco Stories was published in October 2010 by Sydney Samizdat Press.[100]

Novels

London’s most famous novels are The Call of the Wild, White Fang, The Sea-Wolf, The Iron Heel, and Martin Eden.[101]

In a letter dated December 27, 1901, London’s Macmillan publisher George Platt Brett, Sr., said «he believed Jack’s fiction represented ‘the very best kind of work’ done in America.»[94]

Critic Maxwell Geismar called The Call of the Wild «a beautiful prose poem»; editor Franklin Walker said that it «belongs on a shelf with Walden and Huckleberry Finn«; and novelist E.L. Doctorow called it «a mordant parable … his masterpiece.»[citation needed]

The historian Dale L. Walker[99] commented:

Jack London was an uncomfortable novelist, that form too long for his natural impatience and the quickness of his mind. His novels, even the best of them, are hugely flawed.

Some critics have said that his novels are episodic and resemble linked short stories. Dale L. Walker writes:

The Star Rover, that magnificent experiment, is actually a series of short stories connected by a unifying device … Smoke Bellew is a series of stories bound together in a novel-like form by their reappearing protagonist, Kit Bellew; and John Barleycorn … is a synoptic series of short episodes.[99]

Ambrose Bierce said of The Sea-Wolf that «the great thing—and it is among the greatest of things—is that tremendous creation, Wolf Larsen … the hewing out and setting up of such a figure is enough for a man to do in one lifetime.» However, he noted, «The love element, with its absurd suppressions, and impossible proprieties, is awful.»[102]

The Iron Heel is an example of a dystopian novel that anticipates and influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.[103] London’s socialist politics are explicitly on display here. The Iron Heel meets the contemporary definition of soft science fiction. The Star Rover (1915) is also science fiction.

Apocrypha

Jack London Credo

London’s literary executor, Irving Shepard, quoted a Jack London Credo in an introduction to a 1956 collection of London stories:

I would rather be ashes than dust!

I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry-rot.

I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet.

The function of man is to live, not to exist.

I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them.

I shall use my time.

The biographer Stasz notes that the passage «has many marks of London’s style» but the only line that could be safely attributed to London was the first.[104] The words Shepard quoted were from a story in the San Francisco Bulletin, December 2, 1916, by journalist Ernest J. Hopkins, who visited the ranch just weeks before London’s death. Stasz notes, «Even more so than today journalists’ quotes were unreliable or even sheer inventions,» and says no direct source in London’s writings has been found. However, at least one line, according to Stasz, is authentic, being referenced by London and written in his own hand in the autograph book of Australian suffragette Vida Goldstein:

Dear Miss Goldstein:–

Seven years ago I wrote you that I’d rather be ashes than dust. I still subscribe to that sentiment.

Sincerely yours,

Jack London

Jan. 13, 1909[105]

In his short story «By The Turtles of Tasman», a character, defending her «ne’er-do-well grasshopperish father» to her «antlike uncle», says: «… my father has been a king. He has lived …. Have you lived merely to live? Are you afraid to die? I’d rather sing one wild song and burst my heart with it, than live a thousand years watching my digestion and being afraid of the wet. When you are dust, my father will be ashes.»

«The Scab»

A short diatribe on «The Scab» is often quoted within the U.S. labor movement and frequently attributed to London. It opens:

After God had finished the rattlesnake, the toad, and the vampire, he had some awful substance left with which he made a scab. A scab is a two-legged animal with a corkscrew soul, a water brain, a combination backbone of jelly and glue. Where others have hearts, he carries a tumor of rotten principles. When a scab comes down the street, men turn their backs and Angels weep in Heaven, and the Devil shuts the gates of hell to keep him out….[106]

In 1913 and 1914, a number of newspapers printed the first three sentences with varying terms used instead of «scab», such as

«knocker»,[107][108]

«stool pigeon»[109]

or «scandal monger».[110]

This passage as given above was the subject of a 1974 Supreme Court case, Letter Carriers v. Austin,[111] in which Justice Thurgood Marshall referred to it as «a well-known piece of trade union literature, generally attributed to author Jack London». A union newsletter had published a «list of scabs,» which was granted to be factual and therefore not libelous, but then went on to quote the passage as the «definition of a scab». The case turned on the question of whether the «definition» was defamatory. The court ruled that «Jack London’s… ‘definition of a scab’ is merely rhetorical hyperbole, a lusty and imaginative expression of the contempt felt by union members towards those who refuse to join», and as such was not libelous and was protected under the First Amendment.[106]

Despite being frequently attributed to London, the passage does not appear at all in the extensive collection of his writings at Sonoma State University’s website. However, in his book War of the Classes he published a 1903 speech titled «The Scab»,[112] which gave a much more balanced view of the topic:

The laborer who gives more time or strength or skill for the same wage than another, or equal time or strength or skill for a less wage, is a scab. The generousness on his part is hurtful to his fellow-laborers, for it compels them to an equal generousness which is not to their liking, and which gives them less of food and shelter. But a word may be said for the scab. Just as his act makes his rivals compulsorily generous, so do they, by fortune of birth and training, make compulsory his act of generousness.

[…]

Nobody desires to scab, to give most for least. The ambition of every individual is quite the opposite, to give least for most; and, as a result, living in a tooth-and-nail society, battle royal is waged by the ambitious individuals. But in its most salient aspect, that of the struggle over the division of the joint product, it is no longer a battle between individuals, but between groups of individuals. Capital and labor apply themselves to raw material, make something useful out of it, add to its value, and then proceed to quarrel over the division of the added value. Neither cares to give most for least. Each is intent on giving less than the other and on receiving more.

Publications

Source unless otherwise specified: Williams

Novels

Short story collections

Autobiographical memoirs

Non-fiction and essays

Plays

Poetry

|

Short stories

|

|

Legacy and honors

- Mount London, also known as Boundary Peak 100, on the Alaska-British Columbia boundary, in the Boundary Ranges of the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, is named for him.[118]

- Jack London Square on the waterfront of Oakland, California was named for him.

- He was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 25¢ Great Americans series postage stamp released on January 11, 1986.

- Jack London Lake (Russian: Озеро Джека Лондона), a mountain lake located in the upper reaches of the Kolyma River in Yagodninsky district of Magadan Oblast.

- Fictional portrayals of London include Michael O’Shea in the 1943 film Jack London, Jeff East in the 1980 film Klondike Fever, Michael Aron in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Time’s Arrow from 1992, Aaron Ashmore in the Murdoch Mysteries episode «Murdoch of the Klondike» from 2012, and Johnny Simmons in the 2014 miniseries Klondike.

See also

- List of celebrities who own wineries and vineyards

Notes

- ^ a b The 1908 version of «To Build a Fire» is available on Wikisource in two places: «To Build a Fire» (Century Magazine) and «To Build a Fire» (in Lost Face – 1910). The 1902 version may be found at the following external link: To Build a Fire (The Jean and Charles Schulz Information Center, Sonoma State University).

References

- ^ Reesman 2009, p. 23.

- ^ «London, Jack». Encyclopædia Britannica Library Edition. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ^ Dictionary of American Biography Base Set. American Council of Learned Societies, 1928–1936. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2006.

- ^ London 1939, p. 12.

- ^ New York Times November 23, 1916.

- ^ Haley, James (October 4, 2011). Wolf: The Lives of Jack London. Basic Books. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0465025039.

- ^ (1910) «Specialty of Short-story Writing,» The Writer, XXII, January–December 1910, p. 9: «There are eight American writers who can get $1000 for a short story—Robert W. Chambers, Richard Harding Davis, Jack London, O. Henry, Booth Tarkington, John Fox, Jr., Owen Wister, and Mrs. Burnett.» $1,000 in 1910 dollars is roughly equivalent to $29,000 today

- ^ a b Swift, John N. «Jack London’s ‘The Unparalleled Invasion’: Germ Warfare, Eugenics, and Cultural Hygiene.» American Literary Realism, vol. 35, no. 1, 2002, pp. 59–71. JSTOR 27747084.

- ^ a b Hensley, John R. «Eugenics and Social Darwinism in Stanley Waterloo’s ‘The Story of Ab’ and Jack London’s ‘Before Adam.’» Studies in Popular Culture, vol. 25, no. 1, 2002, pp. 23–37. JSTOR 23415006.

- ^ «UPI Almanac for Tuesday, Jan. 12, 2021». United Press International. January 12, 2021. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

…novelist Jack London in 1876…

- ^ Wellman, Joshua Wyman Descendants of Thomas Wellman (1918) Arthur Holbrook Wellman, Boston, p. 227

- ^ «The Book of Jack London». The World of Jack London. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 14: «What supports Flora’s naming Chaney as the father of her son are, first, the indisputable fact of their cohabiting at the time of his conception, and second, the absence of any suggestion on the part of her associates that another man could have been responsible… [but] unless DNA evidence is introduced, whether or not William Chaney was the biological father of Jack London cannot be decided…. Chaney would, however, be considered by her son and his children as their ancestor.»

- ^ «Before Adam (Paperback) | The Book Table». www.booktable.net. Retrieved February 12, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Jeanne Campbell Reesman, Jack London’s Racial Lives: A Critical Biography, University of Georgia Press, 2009, pp. 323–24

- ^ Kershaw 1999, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Ouida (July 26, 1875). «Signa. A story». London : Chapman & Hall – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Ouida (July 26, 1875). «Signa. A story». London : Chapman & Hall – via Internet Archive.

- ^ London, Jack (1917) «Eight Factors of Literary Success», in Labor (1994), p. 512. «In answer to your question as to the greatest factors of my literary success, I will state that I consider them to be: Vast good luck. Good health; good brain; good mental and muscular correlation. Poverty. Reading Ouida’s Signa at eight years of age. The influence of Herbert Spencer’s Philosophy of Style. Because I got started twenty years before the fellows who are trying to start today.»

- ^ «State’s first poet laureate remembered at Jack London». Sonoma Index Tribune. August 22, 2016. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^

- Jack London. John Barleycorn at Project Gutenberg Chapters VII, VIII describe his stealing of Mamie, the «Queen of the Oyster Pirates»: «The Queen asked me to row her ashore in my skiff…Nor did I understand Spider’s grinning side-remark to me: «Gee! There’s nothin’ slow about YOU.» How could it possibly enter my boy’s head that a grizzled man of fifty should be jealous of me?» «And how was I to guess that the story of how the Queen had thrown him down on his own boat, the moment I hove in sight, was already the gleeful gossip of the water-front?

- ^ London 1939, p. 41.

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 37: «It was said on the waterfront that Jack had taken on a mistress… Evidently Jack believed the myth himself at times… Jack met Mamie aboard the Razzle-Dazzle when he first approached French Frank about its purchase. Mamie was aboard on a visit with her sister Tess and her chaperone, Miss Hadley. It hardly seems likely that someone who required a chaperone on Saturday would move aboard as mistress on Monday.»

- ^ Charmian K. London (August 1, 1922). «The First Story Written for Publication». Sonoma County, California: JackLondons.net. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013.

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 67.

- ^ MacGillivray, Don (2009). Captain Alex MacLean. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0774814713. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ MacGillivray, Don (2008). Captain Alex MacLean (PDF). ISBN 978-0774814713. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ «The legends of Oakland’s oldest bar, Heinold’s First and Last Chance Saloon». Oakland North. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ «Footnote 55 to «Bâtard»«. JackLondons.net. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2013. First published as «Diable – A Dog». The Cosmopolitan, v. 33 (June 1902), pp. 218–26. [FM]

This tale was titled «Bâtard» in 1904 when included in FM. The same story, with minor changes, was also called «Bâtard» when it appeared in the Sunday Illustrated Magazine of the Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tenn.), September 28, 1913, pp. 7–11. London received $141.25 for this story on May 27, 1902. - ^ «The 100 best novels: No 35 – The Call of the Wild by Jack London (1903)» Retrieved July 22, 2015

- ^ «Best Dog Story Ever Written: Call of the Wild» Archived April 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, excerpted from Kingman 1979

- ^ Hamilton (1986) (as cited by other sources)

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 61: «Both acknowledged… that they were not marrying out of love»

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 98.

- ^ Reesman 2010, p 12

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 66: «Mommy Girl and Daddy Boy»

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 121.

- ^ Noel 1940, p. 150, «She’s devoted to purity…»

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 80 («devoted to purity… code words…»)

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 139.

- ^ Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- ^ London & Taylor 1987, p. 394.

- ^ Wichlan 2007, p. 131.

- ^ Labor 2013

- ^ «The Sailing of the Snark», by Allan Dunn, Sunset, May 1907.

- ^ a b Day 1996, pp. 113–19.

- ^ London 2003, p. 59: copy of «John Barleycorn» inscribed «Dear Mate-Woman: You know. You have helped me bury the Long Sickness and the White Logic.» Numerous other examples in same source.

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 124.

- ^ Stasz 1999, p. 112.

- ^ Kershaw 1999, p. 133.

- ^ Noel 1940, p. 146.

- ^ Walker, Dale; Reesman, Jeanne, eds. (1999). «A Selection of Letters to Charmain Kittredge». No Mentor But Myself: Jack London on Writers and Writing. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804736367. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Jack London «Story Of An Eyewitness». California Department of Parks & Recreation.

- ^ Stasz, Clarice (2013). Jack London’s Women. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1625340658. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream, 1850–1915. Oxford University, 1986.

- ^ Joseph Theroux. «They Came to Write in Hawai’i». Spirit of Aloha (Aloha Airlines) March/April 2007. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008.

He said, «Life’s not a matter of holding good cards, but sometimes playing a poor hand well.» …His last magazine piece was titled «My Hawaiian Aloha»* [and] his final, unfinished novel, Eyes of Asia, was set in Hawai’i.

(Jack London. «My Hawaiian Aloha». *From Stories of Hawai’i, Mutual Publishing, Honolulu, 1916. Reprinted with permission in Spirit of Aloha, November/December 2006. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008.) - ^ Beers, Diane L. (2006). For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States. Athens: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press. pp. 105–06. ISBN 0804010870.

- ^ Beers, Diane L. (2006). For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States. Athens: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press. pp. 106–07. ISBN 0804010870.

- ^ Beers, Diane L. (2006). For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States. Athens: Swallow Press/Ohio University Press. p. 107. ISBN 0804010870.

- ^ «On This Day: November 23, 1916: Obituary – Jack London Dies Suddenly On Ranch». The New York Times. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Jack London (1911). The Cruise of the Snark. Macmillan.

- ^ «Marin County Tocsin». contentdm.marinlibrary.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ McConahey, Meg (July 22, 2022). «Was Jack London a drug addict? New technology examines old mysteries». Santa Rosa Press Democrat. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia «Jack London», «Beset in his later years by alcoholism and financial difficulties, London committed suicide at the age of 40.»

- ^ The Jack London Online Collection: Jack London’s death certificate.

- ^ The Jack London Online Collection: Biography.

- ^ «Did Jack London Commit Suicide?» Archived September 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The World of Jack London

- ^ «Martin Eden by Jack London | Goodreads». Goodreads: Martin Eden.

- ^ admin (June 5, 2019). «Jack London: Martin Eden — by Franklin Walker». Scraps from the loft. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ «Jack London letters to Sinclair Lewis, dated September through December 1910» (PDF). Utah State University University Libraries Digital Exhibits. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ «The Literary Zoo». Life. Vol. 49. January–June 1907. p. 130.

- ^ «The Retriever and the Dynamite Stick — A Remarkable Coincidence». The New York Times. The New York Times Company. August 16, 1902. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ «Young, Everton Ryerson». Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ «Memorable Manitobans: Egerton Ryerson Young (1840–1909)». The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ «Is Jack London a Plagiarist?». The Literary Digest. 34: 337. 1907.

- ^ Kingman 1979, p. 118.

- ^ Letter to «The Bookman,» April 10, 1906, quoted in full in Jack London; Dale L. Walker; Jeanne Campbell Reesman (2000). No mentor but myself: Jack London on writing and writers. Stanford University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0804736350. «The World, however, did not charge me with plagiarism. It charged me with identity of time and situation. Certainly I plead guilty, and I am glad that the World was intelligent enough not to charge me with identity of language.»

- ^ Jack London; Dale L. Walker; Jeanne Campbell Reesman (2000). No mentor but myself: Jack London on writing and writers. Stanford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0804736350. «The controversy with Frank Harris began in the Vanity Fair issue of April 14, 1909, in an article by Harris entitled ‘How Mr. Jack London Writes a Novel.’ Using parallel columns, Harris demonstrated that a portion of his article, ‘The Bishop of London and Public Morality,’ which appeared in a British periodical, The Candid Friend, on May 25, 1901, had been used almost word-for-word in his 1908 novel, The Iron Heel.»

- ^ Stewart Gabel (2012). Jack London: a Man in Search of Meaning: A Jungian Perspective. AuthorHouse. p. 14. ISBN 978-1477283332.

When he was tramping, arrested and jailed for one month for vagrancy at about 19 years of age, he listed «atheist» as his religion on the necessary forms (Kershaw, 1997).

- ^ Who’s Who in Hell: A Handbook and International Directory for Humanists, Freethinkers, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-Theists. Barricade Books (2000), ISBN 978-1569801581

- ^ «War of the Classes: How I Became a Socialist». london.sonoma.edu. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ See Labor (1994) p. 546 for one example, a letter from London to William E. Walling dated November 30, 1909.

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Stasz 2001, p. 156.

- ^ Kershaw 1999, p. 245.

- ^ Starr, Kevin (1973). Americans and the California Dream. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195016440. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ The Jack London Online Collection: The Yellow Peril.

- ^ The Jack London Online Collection: The Unparalleled Invasion.

- ^ «Jack London’s War» Archived October 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Dale L. Walker, The World of Jack London. «According to London’s reportage, the Russians were «sluggish» in battle, while «The Japanese understand the utility of things. Reserves they consider should be used not only to strengthen the line…but in the moment of victory to clinch victory hard and fast…Verily, nothing short of a miracle can wreck a plan they have once started and put into execution.»»

- ^ Labor, Earle, Robert C. Leitz, III, and I. Milo Shepard: The Letters of Jack London: Volume Three: 1913–1916, Stanford University Press 1988, p. 1219, Letter to Japanese-American Commercial Weekly, August 25, 1913: «the races of mankind will grow up and laugh [at] their childish quarrels…»

- ^ Lundberg.

- ^ «A True Champion Vs. The ‘Great White Hope’«. NPR. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C., Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era, Princeton University Press, Princeton Univ. Press, 2016, p. 114

- ^ a b Kershaw 1999, p. 109.

- ^ Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck V. Bell, JHU Press, October 6, 2008, p. 55.

- ^ Williams, Jay, Author Under Sail, Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1014, p. 294.

- ^ Craid, Layne Parish, «Sex and Science in London’s America,» in Williams, Jay, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Jack London, Oxford Univ. Press, 2017, pp. 340–41.

- ^ London, Charmian, Our Hawaii: Islands and Islanders, Macmillan, 1922, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Dale L. Walker, «Jack London: The Stories» Archived October 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, The World of Jack London

- ^ Jack London: San Francisco Stories (Edited by Matthew Asprey; Preface by Rodger Jacobs)

- ^ These are the five novels selected by editor Donald Pizer for inclusion in the Library of America series.

- ^ Letters of Ambrose Bierce, ed. S. T. Joshi, Tryambak Sunand Joshi, David E. Schultz, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2003

- ^ Orwell: the Authorized Biography by Michael Shelden, HarperCollins ISBN 978-0060921613

- ^ Jack London Online: FAQ, Credo.

- ^ The Jack London Online Collection: Credo.

- ^ a b Thurgood Marshall (June 25, 1974). «Letter Carriers v. Austin, 418 U.S. 264 (1974)». Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ Callan, Claude, 1913, «Cracks at the Crowd», Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 30, 1913, p. 6: «Saith the Rule Review: ‘After God had finished making the rattlesnake, the toad and the vampire, He had some awful substance left, with which he made the knocker.’ Were it not for being irreverent, we would suggest that He was hard up for something to do when He made any of those pests you call his handiwork.»

- ^ «The Food for Your Think Tank», The Macon Daily Telegraph, August 23, 1914, p. 3

- ^ » Madame Gain is Found Guilty. Jury Decides Woman Conducted House of Ill Fame at the Clifton Hotel,» The Duluth News Tribune, February 5, 1914, p. 12.

- ^ «T. W. H.», (1914), «Review of the Masonic ‘Country’ Press: The Eastern Star» The New Age Magazine: A Monthly Publication Devoted to Freemasonry and Its Relation to Present Day Problems, published by the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry for the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States; June 1917, p. 283: «Scandal Monger: After God had finished making the rattlesnake, the toad and the vampire, He had some awful substance left, with which He made a scandal monger. A scandal monger is a two-legged animal with a cork-screw soul, a water-sogged brain and a combination backbone made of jelly and glue. Where other men have their hearts he carries a tumor of decayed principles. When the scandal monger comes down the street honest men turn their backs, the angels weep tears in heaven, and the devil shuts the gates of hell to keep him out. —Anon»

- ^ Letter Carriers v. Austin, 418 U.S. 264 (1974).

- ^ «War of the Classes: The Scab». london.sonoma.edu. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l The Jack London Online Collection: Writings.

- ^ «How I Became a Socialist. The Comrade: An illustrated socialist monthly. Volume II, No. 6, March, 1903: Jack London: Books». Amazon. September 9, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ London, Jack (1908). «The Lepers of Molokai». Woman’s Home Companion. 35 (1): 6–7. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ London, Jack (1908). «The Nature Man». Woman’s Home Companion. 35 (9): 21–22. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ London, Jack (1908). «The High Seat of Abundance». Woman’s Home Companion. 35 (11): 13–14, 70. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ «London, Mount». BC Geographical Names.

Bibliography

- Day, A. Grove (1996) [1984]. «Jack London and Hawaii». In Dye, Bob (ed.). Hawaiʻi Chronicles. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 113–19. ISBN 0824818296.

- Kershaw, Alex (1999). Jack London. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 031219904X.

- Kingman, Russ (1979). A Pictorial Life of Jack London. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. (original); also «Published for Jack London Research Center by David Rejl, California» (same ISBN). ISBN 0517540932.

- London, Charmian (2003) [1921]. The Book of Jack London, Volume II. Kessinger. ISBN 0766161889.

- London, Jack; Taylor, J. Golden (1987). A Literary history of the American West. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press. ISBN 087565021X.

- London, Joan (1939). Jack London and His Times. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. LCCN 39-33408.

- Lundberg, Murray. «The Life of Jack London as Reflected in his Works». Explore North. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008.

- Noel, Joseph (1940). Footloose in Arcadia: A Personal Record of Jack London, George Sterling, Ambrose Bierce. New York: Carrick and Evans.

- Reesman, Jeanne Campbell (2009). Jack London’s Racial Lives: A Critical Biography. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0820327891.

- Stasz, Clarice (1999) [1988]. American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London. toExcel (iUniverse, Lincoln, Nebraska). ISBN 0595000029.

- Stasz, Clarice (2001). Jack London’s Women. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1558493018.

- Wichlan, Daniel J. (2007). The Complete Poetry of Jack London. Waterford, CT: Little Red Tree Publishing. ISBN 978-0978944629.

- Reesman, Jeanne; Hodson, Sara; Adam, Philip (2010). Jack London Photographer. Athens and London: University of Georgia Press.

- «Jack London Dies Suddenly On Ranch». The New York Times. November 23, 1916. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

Novelist is Found Unconscious from Uremia, and Expires after Eleven Hours. Wrote His Life of Toil—His Experience as Sailor Reflected in His Fiction—’Call of the Wild’ Gave Him His Fame.» ‘The New York Times,’ story datelined Santa Rosa, Cal., Nov. 22; appeared November 24, 1916, p. 13. States he died ‘at 7:45 o’clock tonight,’ and says he was ‘born in San Francisco on January 12, 1876.’

The Jack London Online Collection

- «Jack London’s death certificate, from County Record’s Office, Sonoma Co., Nov. 22, 1916». The Jack London Online Collection. November 22, 1916. Archived from the original on April 27, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Stasz, Clarice (2001). «Jack [John Griffith] London». The Jack London Online Collection. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- «Revolution and Other Essays: The Yellow Peril». The Jack London Online Collection. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- «The Unparalleled Invasion». The Jack London Online Collection. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- «Jack London’s «Credo», Commentary by Clarice Stasz». The Jack London Online Collection. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Roy Tennant and Clarice Stasz. «Jack London’s Writings». The Jack London Online Collection. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Jacobs, Rodger (July 1999). «Running with the Wolves: Jack London, the Cult of Masculinity, and «Might is Right»«. Panik. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- Williams, James. «Jack London’s Works by Date of Composition». The Jack London Online Collection. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

Further reading

- Jacobs, Rodger (preface) (2010). Asprey, Matthew (ed.). Jack London: San Francisco Stories. Sydney: Sydney Samizdat Press. ISBN 978-1453840504.

- Haley, James L. (2010). Wolf: The Lives of Jack London. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465004782.

- Hamilton, David (1986). The Tools of My Trade: Annotated Books in Jack London’s Library. University of Washington. ISBN 0295961570.

- Herron, Don (2004). The Barbaric Triumph: A Critical Anthology on the Writings of Robert E. Howard. Wildside Press. ISBN 0809515660.

- Howard, Robert E. (1989). Robert E. Howard Selected Letters 1923–1930. West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN 0940884267.

- Labor, Earle (2013). Jack London: An American Life. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374178482.

- Labor, Earle, ed. (1994). The Portable Jack London. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0140179690.

- London, Jack; Strunsky, Anna (2000) [1903]. The Kempton-Wace Letters. Czech Republic: Triality. ISBN 8090187684.

- Lord, Glenn (1976). The Last Celt: A Bio-Bibliography of Robert E. Howard. West Kingston, RI: Donald M. Grant, Publisher.

- Oates, Joyce Carol (2013). The Accursed. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0062231703.

- Pizer, Donald, ed. (1982). Jack London: Novels and Stories. Library of America. ISBN 978-0940450059.

- Pizer, Donald, ed. (1982). Jack London: Novels and Social Writing. Library of America. ISBN 978-0940450066.

- Raskin, Jonah, ed. (2008). The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520255463.

- Sinclair, Andrew (1977). Jack: A Biography of Jack London. United States: HarperCollins. ISBN 0060138998.

- Starr, Kevin (1986) [1973]. Americans and the California Dream 1850–1915. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195042336.

- Stasz, Clarice (1988). American Dreamers: Charmian and Jack London. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0312021603.

- Wichlan, Daniel (2014). The Complete Poetry of Jack London. 2nd. ed. New London, CT: Little Tree.

- Williams, Jay (2014). Author Under Sail: The Imagination of Jack London, 1893–1902. Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska.

- Williams, Jay, ed. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Jack London. Oxford Univ. Press.

External links

|

Jack London |

|

|---|---|

London in 1903 |

|

| Born | John Griffith Chaney January 12, 1876 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | November 22, 1916 (aged 40) Glen Ellen, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Literary movement | Realism, Naturalism |

| Notable works | The Call of the Wild White Fang |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Maddern (m. ; div. ) Charmian Kittredge (m. 1905) |

| Children | Joan London Bessie London |

| Signature | |

John Griffith Chaney[1] (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London,[2][3][4][5] was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to become an international celebrity and earn a large fortune from writing.[6] He was also an innovator in the genre that would later become known as science fiction.[7]

London was part of the radical literary group «The Crowd» in San Francisco and a passionate advocate of animal rights, workers’ rights and socialism.[8][9] London wrote several works dealing with these topics, such as his dystopian novel The Iron Heel, his non-fiction exposé The People of the Abyss, War of the Classes, and Before Adam.

His most famous works include The Call of the Wild and White Fang, both set in Alaska and the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush, as well as the short stories «To Build a Fire», «An Odyssey of the North», and «Love of Life». He also wrote about the South Pacific in stories such as «The Pearls of Parlay», and «The Heathen».

Family

Flora and John London, Jack’s mother and stepfather

Jack London was born January 12, 1876.[10] His mother, Flora Wellman, was the fifth and youngest child of Pennsylvania Canal builder Marshall Wellman and his first wife, Eleanor Garrett Jones. Marshall Wellman was descended from Thomas Wellman, an early Puritan settler in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[11] Flora left Ohio and moved to the Pacific coast when her father remarried after her mother died. In San Francisco, Flora worked as a music teacher and spiritualist, claiming to channel the spirit of a Sauk chief, Black Hawk.[12][clarification needed]

Biographer Clarice Stasz and others believe London’s father was astrologer William Chaney.[13] Flora Wellman was living with Chaney in San Francisco when she became pregnant. Whether Wellman and Chaney were legally married is unknown. Stasz notes that in his memoirs, Chaney refers to London’s mother Flora Wellman as having been «his wife»; he also cites an advertisement in which Flora called herself «Florence Wellman Chaney».[14]

According to Flora Wellman’s account, as recorded in the San Francisco Chronicle of June 4, 1875, Chaney demanded that she have an abortion. When she refused, he disclaimed responsibility for the child. In desperation, she shot herself. She was not seriously wounded, but she was temporarily deranged. After giving birth, Flora sent the baby for wet-nursing to Virginia (Jennie) Prentiss, a formerly enslaved African-American woman and a neighbor. Prentiss was an important maternal figure throughout London’s life, and he would later refer to her as his primary source of love and affection as a child.[15]

Late in 1876, Flora Wellman married John London, a partially disabled Civil War veteran, and brought her baby John, later known as Jack, to live with the newly married couple. The family moved around the San Francisco Bay Area before settling in Oakland, where London completed public grade school. The Prentiss family moved with the Londons, and remained a stable source of care for the young Jack.[15]

In 1897, when he was 21 and a student at the University of California, Berkeley, London searched for and read the newspaper accounts of his mother’s suicide attempt and the name of his biological father. He wrote to William Chaney, then living in Chicago. Chaney responded that he could not be London’s father because he was impotent; he casually asserted that London’s mother had relations with other men and averred that she had slandered him when she said he insisted on an abortion. Chaney concluded by saying that he was more to be pitied than London.[16] London was devastated by his father’s letter; in the months following, he quit school at Berkeley and went to the Klondike during the gold rush boom.

Early life

London at the age of nine with his dog Rollo, 1885

London was born near Third and Brannan Streets in San Francisco. The house burned down in the fire after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; the California Historical Society placed a plaque at the site in 1953. Although the family was working class, it was not as impoverished as London’s later accounts claimed.[citation needed] London was largely self-educated.[citation needed]

In 1885, London found and read Ouida’s long Victorian novel Signa.[17][18] He credited this as the seed of his literary success.[19] In 1886, he went to the Oakland Public Library and found a sympathetic librarian, Ina Coolbrith, who encouraged his learning. (She later became California’s first poet laureate and an important figure in the San Francisco literary community).[20]

In 1889, London began working 12 to 18 hours a day at Hickmott’s Cannery. Seeking a way out, he borrowed money from his foster mother Virginia Prentiss, bought the sloop Razzle-Dazzle from an oyster pirate named French Frank, and became an oyster pirate himself. In his memoir, John Barleycorn, he claims also to have stolen French Frank’s mistress Mamie.[21][22][23] After a few months, his sloop became damaged beyond repair. London hired on as a member of the California Fish Patrol.

In 1893, he signed on to the sealing schooner Sophie Sutherland, bound for the coast of Japan. When he returned, the country was in the grip of the panic of ’93 and Oakland was swept by labor unrest. After grueling jobs in a jute mill and a street-railway power plant, London joined Coxey’s Army and began his career as a tramp. In 1894, he spent 30 days for vagrancy in the Erie County Penitentiary at Buffalo, New York. In The Road, he wrote:

Man-handling was merely one of the very minor unprintable horrors of the Erie County Pen. I say ‘unprintable’; and in justice I must also say undescribable. They were unthinkable to me until I saw them, and I was no spring chicken in the ways of the world and the awful abysses of human degradation. It would take a deep plummet to reach bottom in the Erie County Pen, and I do but skim lightly and facetiously the surface of things as I there saw them.

— Jack London, The Road

After many experiences as a hobo and a sailor, he returned to Oakland and attended Oakland High School. He contributed a number of articles to the high school’s magazine, The Aegis. His first published work was «Typhoon off the Coast of Japan», an account of his sailing experiences.[24]