| Mona Lisa | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Gioconda, Monna Lisa | |

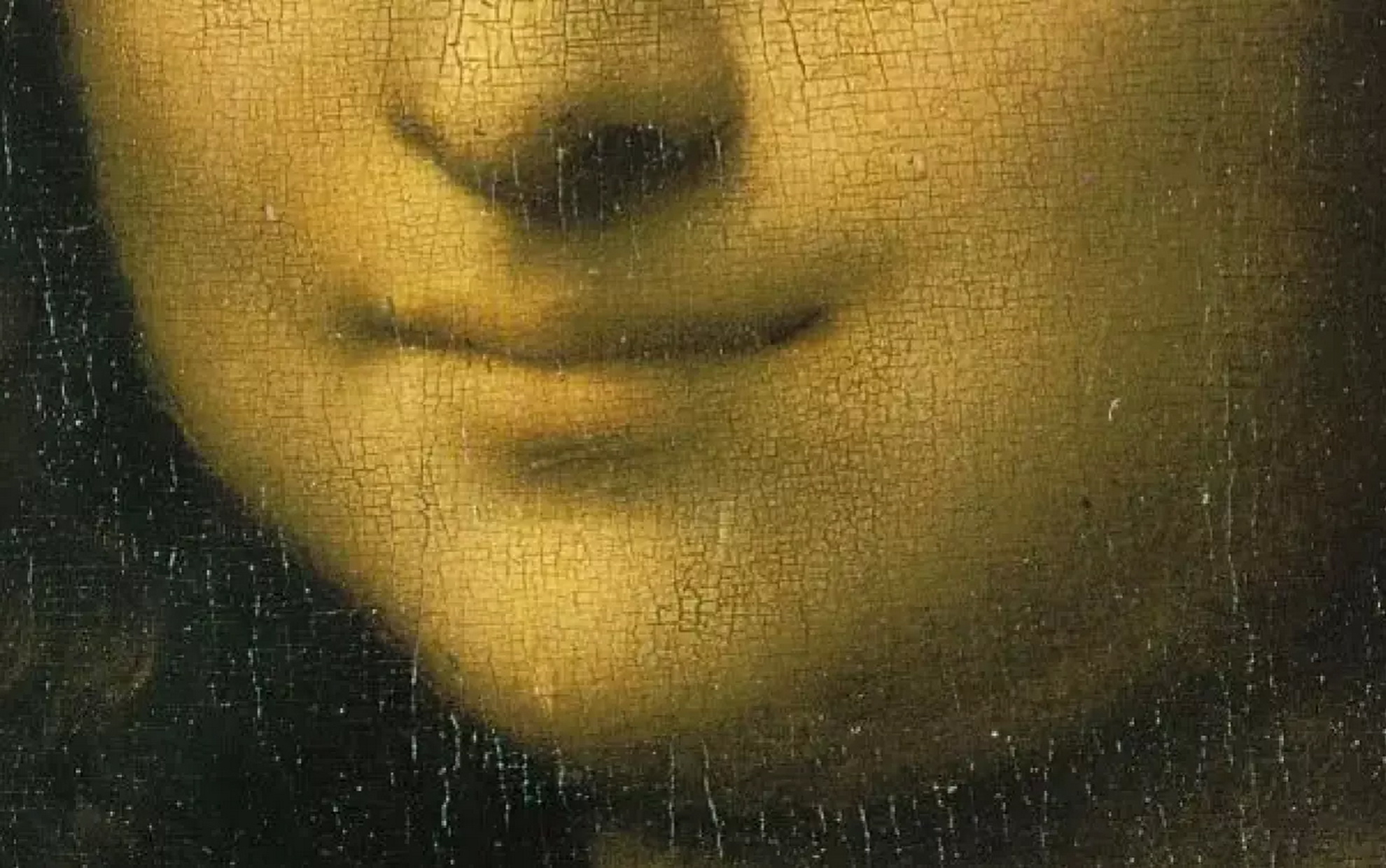

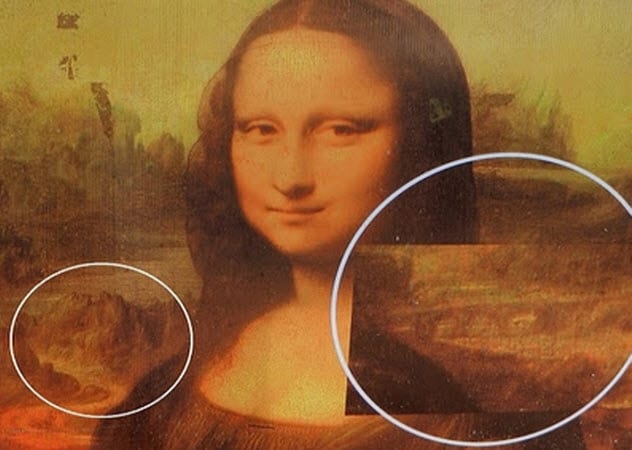

The Mona Lisa digitally retouched to reduce the effects of aging. The unretouched image is darker.[1][2][3] |

|

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1503–1506, perhaps continuing until c. 1517 |

| Medium | Oil on poplar panel |

| Subject | Lisa Gherardini |

| Dimensions | 77 cm × 53 cm (30 in × 21 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

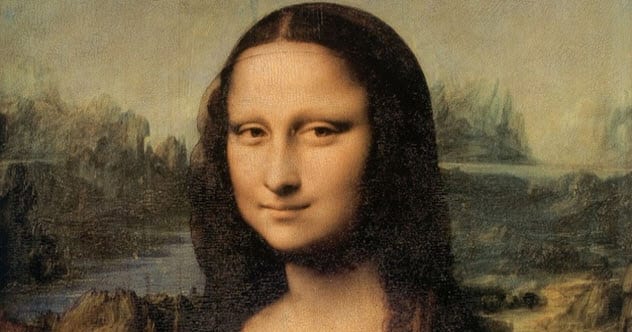

The Mona Lisa ( MOH-nə LEE-sə; Italian: Gioconda [dʒoˈkonda] or Monna Lisa [ˈmɔnna ˈliːza]; French: Joconde [ʒɔkɔ̃d]) is a half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance,[4][5] it has been described as «the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world».[6] The painting’s novel qualities include the subject’s enigmatic expression,[7] the monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism.[8]

The painting has been definitively identified to depict Italian noblewoman Lisa Gherardini,[9] the wife of Francesco del Giocondo. It is painted in oil on a white Lombardy poplar panel. Leonardo never gave the painting to the Giocondo family, and later it is believed he left it in his will to his favored apprentice Salaì.[10] It had been believed to have been painted between 1503 and 1506; however, Leonardo may have continued working on it as late as 1517. It was acquired by King Francis I of France and is now the property of the French Republic. It has been on permanent display at the Louvre in Paris since 1797.[11]

The painting’s global fame and popularity stem from its 1911 theft by Vincenzo Peruggia, who attributed his actions to Italian patriotism – a belief that the painting should belong to Italy. The theft and subsequent recovery in 1914 generated unprecedented publicity for an art theft, and led to the publication of numerous cultural depictions such as the 1915 opera Mona Lisa, two early 1930s films about the theft (The Theft of the Mona Lisa and Arsène Lupin) and the popular song Mona Lisa recorded by Nat King Cole – one of the most successful songs of the 1950s.[12]

The Mona Lisa is one of the most valuable paintings in the world. It holds the Guinness World Record for the highest-known painting insurance valuation in history at US$100 million in 1962[13] (equivalent to $870 million in 2021).

Title and subject

The title of the painting, which is known in English as Mona Lisa, is based on the presumption that it depicts Lisa del Giocondo, although her likeness is uncertain. Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote that «Leonardo undertook to paint, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife.»[16][17][18][19] Monna in Italian is a polite form of address originating as ma donna—similar to Ma’am, Madam, or my lady in English. This became madonna, and its contraction monna. The title of the painting, though traditionally spelled Mona in English, is spelled in Italian as Monna Lisa (mona being a vulgarity in Italian), but this is rare in English.[20][21]

Lisa del Giocondo was a member of the Gherardini family of Florence and Tuscany, and the wife of wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo.[22] The painting is thought to have been commissioned for their new home, and to celebrate the birth of their second son, Andrea.[23] The Italian name for the painting, La Gioconda, means ‘jocund’ (‘happy’ or ‘jovial’) or, literally, ‘the jocund one’, a pun on the feminine form of Lisa’s married name, Giocondo.[22][24] In French, the title La Joconde has the same meaning.

Vasari’s account of the Mona Lisa comes from his biography of Leonardo published in 1550, 31 years after the artist’s death. It has long been the best-known source of information on the provenance of the work and identity of the sitter. Leonardo’s assistant Salaì, at his death in 1524, owned a portrait which in his personal papers was named la Gioconda, a painting bequeathed to him by Leonardo.[citation needed]

That Leonardo painted such a work, and its date, were confirmed in 2005 when a scholar at Heidelberg University discovered a marginal note in a 1477 printing of a volume by ancient Roman philosopher Cicero. Dated October 1503, the note was written by Leonardo’s contemporary Agostino Vespucci. This note likens Leonardo to renowned Greek painter Apelles, who is mentioned in the text, and states that Leonardo was at that time working on a painting of Lisa del Giocondo.[25]

In response to the announcement of the discovery of this document, Vincent Delieuvin, the Louvre representative, stated «Leonardo da Vinci was painting, in 1503, the portrait of a Florentine lady by the name of Lisa del Giocondo. About this we are now certain. Unfortunately, we cannot be absolutely certain that this portrait of Lisa del Giocondo is the painting of the Louvre.»[26]

The catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci (2019) confirms that the painting probably depicts Lisa del Giocondo, with Isabella d’Este being the only plausible alternative.[27] Scholars have developed several alternative views, arguing that Lisa del Giocondo was the subject of a different portrait, and identifying at least four other paintings referred to by Vasari as the Mona Lisa.[28] Several other people have been proposed as the subject of the painting,[29] including Isabella of Aragon,[30] Cecilia Gallerani,[31] Costanza d’Avalos, Duchess of Francavilla,[29] Pacifica Brandano/Brandino, Isabela Gualanda, Caterina Sforza, Bianca Giovanna Sforza, Salaì, and even Leonardo himself.[32][33][34] Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud theorized that Leonardo imparted an approving smile from his mother, Caterina, onto the Mona Lisa and other works.[35][36]

Description

Detail of the background (right side)

The Mona Lisa bears a strong resemblance to many Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary, who was at that time seen as an ideal for womanhood.[37] The woman sits markedly upright in a «pozzetto» armchair with her arms folded, a sign of her reserved posture. Her gaze is fixed on the observer. The woman appears alive to an unusual extent, which Leonardo achieved by his method of not drawing outlines (sfumato). The soft blending creates an ambiguous mood «mainly in two features: the corners of the mouth, and the corners of the eyes».[38]

The depiction of the sitter in three-quarter profile is similar to late 15th-century works by Lorenzo di Credi and Agnolo di Domenico del Mazziere.[37] Zöllner notes that the sitter’s general position can be traced back to Flemish models and that «in particular the vertical slices of columns at both sides of the panel had precedents in Flemish portraiture.»[39] Woods-Marsden cites Hans Memling’s portrait of Benedetto Portinari (1487) or Italian imitations such as Sebastiano Mainardi’s pendant portraits for the use of a loggia, which has the effect of mediating between the sitter and the distant landscape, a feature missing from Leonardo’s earlier portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci.[40]

Detail of Lisa’s hands, her right hand resting on her left. Leonardo chose this gesture rather than a wedding ring to depict Lisa as a virtuous woman and faithful wife.[41]

The painting was one of the first portraits to depict the sitter in front of an imaginary landscape, and Leonardo was one of the first painters to use aerial perspective.[42] The enigmatic woman is portrayed seated in what appears to be an open loggia with dark pillar bases on either side. Behind her, a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains. Winding paths and a distant bridge give only the slightest indications of human presence. Leonardo has chosen to place the horizon line not at the neck, as he did with Ginevra de’ Benci, but on a level with the eyes, thus linking the figure with the landscape and emphasizing the mysterious nature of the painting.[40]

Mona Lisa has no clearly visible eyebrows or eyelashes, although Vasari describes the eyebrows in detail.[43][a] In 2007, French engineer Pascal Cotte announced that his ultra-high resolution scans of the painting provide evidence that Mona Lisa was originally painted with eyelashes and eyebrows, but that these had gradually disappeared over time, perhaps as a result of overcleaning.[46] Cotte discovered the painting had been reworked several times, with changes made to the size of the Mona Lisa’s face and the direction of her gaze. He also found that in one layer the subject was depicted wearing numerous hairpins and a headdress adorned with pearls which was later scrubbed out and overpainted.[47]

There has been much speculation regarding the painting’s model and landscape. For example, Leonardo probably painted his model faithfully since her beauty is not seen as being among the best, «even when measured by late quattrocento (15th century) or even twenty-first century standards.»[48] Some art historians in Eastern art, such as Yukio Yashiro, argue that the landscape in the background of the picture was influenced by Chinese paintings,[49] but this thesis has been contested for lack of clear evidence.[49]

Research in 2003 by Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University said that Mona Lisa’s smile disappears when observed with direct vision, known as foveal. Because of the way the human eye processes visual information, it is less suited to pick up shadows directly; however, peripheral vision can pick up shadows well.[50]

Research in 2008 by a geomorphology professor at Urbino University and an artist-photographer revealed likenesses of Mona Lisa‘s landscapes to some views in the Montefeltro region in the Italian provinces of Pesaro and Urbino, and Rimini.[51][52]

History

Creation and date

Of Leonardo da Vinci’s works, the Mona Lisa is the only portrait whose authenticity has never been seriously questioned,[53] and one of four works – the others being Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, Adoration of the Magi and The Last Supper – whose attribution has avoided controversy.[54] He had begun working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model of the Mona Lisa, by October 1503.[25][26] It is believed by some that the Mona Lisa was begun in 1503 or 1504 in Florence.[55] Although the Louvre states that it was «doubtless painted between 1503 and 1506»,[8] art historian Martin Kemp says that there are some difficulties in confirming the dates with certainty.[22] Alessandro Vezzosi believes that the painting is characteristic of Leonardo’s style in the final years of his life, post-1513.[56] Other academics argue that, given the historical documentation, Leonardo would have painted the work from 1513.[57] According to Vasari, «after he had lingered over it four years, [he] left it unfinished».[17] In 1516, Leonardo was invited by King Francis I to work at the Clos Lucé near the Château d’Amboise; it is believed that he took the Mona Lisa with him and continued to work on it after he moved to France.[32] Art historian Carmen C. Bambach has concluded that Leonardo probably continued refining the work until 1516 or 1517.[58] Leonardo’s right hand was paralytic circa 1517,[59] which may indicate why he left the Mona Lisa unfinished.[60][61][62][b]

Raphael’s drawing (c. 1505), after Leonardo; today in the Louvre along with the Mona Lisa[64]

Circa 1505,[64] Raphael executed a pen-and-ink sketch, in which the columns flanking the subject are more apparent. Experts universally agree that it is based on Leonardo’s portrait.[65][66][67] Other later copies of the Mona Lisa, such as those in the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design and The Walters Art Museum, also display large flanking columns. As a result, it was thought that the Mona Lisa had been trimmed.[68][69][70][71] However, by 1993, Frank Zöllner observed that the painting surface had never been trimmed;[72] this was confirmed through a series of tests in 2004.[73] In view of this, Vincent Delieuvin, curator of 16th-century Italian painting at the Louvre, states that the sketch and these other copies must have been inspired by another version,[74] while Zöllner states that the sketch may be after another Leonardo portrait of the same subject.[72]

The record of an October 1517 visit by Louis d’Aragon states that the Mona Lisa was executed for the deceased Giuliano de’ Medici, Leonardo’s steward at Belvedere, Vienna, between 1513 and 1516[75][76][c]—but this was likely an error.[77][d] According to Vasari, the painting was created for the model’s husband, Francesco del Giocondo.[78] A number of experts have argued that Leonardo made two versions (because of the uncertainty concerning its dating and commissioner, as well as its fate following Leonardo’s death in 1519, and the difference of details in Raphael’s sketch—which may be explained by the possibility that he made the sketch from memory).[64][67][66][79] The hypothetical first portrait, displaying prominent columns, would have been commissioned by Giocondo circa 1503, and left unfinished in Leonardo’s pupil and assistant Salaì’s possession until his death in 1524. The second, commissioned by Giuliano de’ Medici circa 1513, would have been sold by Salaì to Francis I in 1518[e] and is the one in the Louvre today.[67][66][79][80] Others believe that there was only one true Mona Lisa, but are divided as to the two aforementioned fates.[22][81][82] At some point in the 16th century, a varnish was applied to the painting.[3] It was kept at the Palace of Fontainebleau until Louis XIV moved it to the Palace of Versailles, where it remained until the French Revolution.[83] In 1797, it went on permanent display at the Louvre.[11]

Refuge, theft, and vandalism

Louis Béroud’s 1911 painting depicting Mona Lisa displayed in the Louvre before the theft, which Béroud discovered and reported to the guards

After the French Revolution, the painting was moved to the Louvre, but spent a brief period in the bedroom of Napoleon (d. 1821) in the Tuileries Palace.[83] The Mona Lisa was not widely known outside the art world, but in the 1860s, a portion of the French intelligentsia began to hail it as a masterwork of Renaissance painting.[84]

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), the painting was moved from the Louvre to the Brest Arsenal.[85]

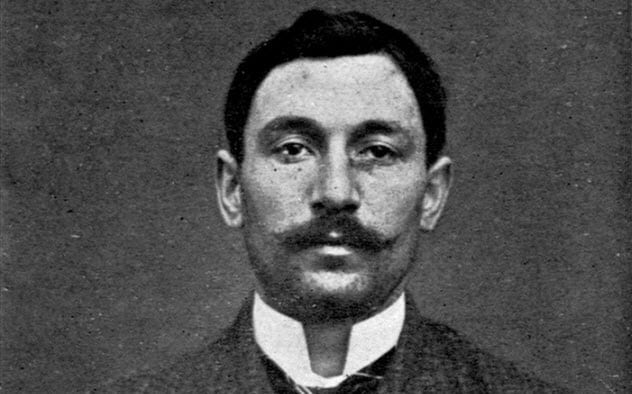

In 1911, the painting was still not popular among the lay-public.[86] On 21 August 1911, the painting was stolen from the Louvre.[87] The painting was first missed the next day by painter Louis Béroud. After some confusion as to whether the painting was being photographed somewhere, the Louvre was closed for a week for investigation. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire came under suspicion and was arrested and imprisoned. Apollinaire implicated his friend Pablo Picasso, who was brought in for questioning. Both were later exonerated.[88][89] The real culprit was Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia, who had helped construct the painting’s glass case.[90] He carried out the theft by entering the building during regular hours, hiding in a broom closet, and walking out with the painting hidden under his coat after the museum had closed.[24]

Vacant wall in the Louvre’s Salon Carré after the painting was stolen in 1911

«La Joconde est Retrouvée» («Mona Lisa is Found»), Le Petit Parisien, 13 December 1913

The Mona Lisa in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, 1913. Museum director Giovanni Poggi (right) inspects the painting.

Excelsior, «La Joconde est Revenue» («The Mona Lisa has returned»), 1 January 1914

Peruggia was an Italian patriot who believed that Leonardo’s painting should have been returned to an Italian museum.[91] Peruggia may have been motivated by an associate whose copies of the original would significantly rise in value after the painting’s theft.[92] After having kept the Mona Lisa in his apartment for two years, Peruggia grew impatient and was caught when he attempted to sell it to Giovanni Poggi, director of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It was exhibited in the Uffizi Gallery for over two weeks and returned to the Louvre on 4 January 1914.[93] Peruggia served six months in prison for the crime and was hailed for his patriotism in Italy.[89] A year after the theft, Saturday Evening Post journalist Karl Decker wrote that he met an alleged accomplice named Eduardo de Valfierno, who claimed to have masterminded the theft. Forger Yves Chaudron was to have created six copies of the painting to sell in the US while concealing the location of the original.[92] Decker published this account of the theft in 1932.[94]

During World War II, it was again removed from the Louvre and taken first to the Château d’Amboise, then to the Loc-Dieu Abbey and Château de Chambord, then finally to the Ingres Museum in Montauban.

On 30 December 1956, Bolivian Ugo Ungaza Villegas threw a rock at the Mona Lisa while it was on display at the Louvre. He did so with such force that it shattered the glass case and dislodged a speck of pigment near the left elbow.[95] The painting was protected by glass because a few years earlier a man who claimed to be in love with the painting had cut it with a razor blade and tried to steal it.[96]

Since then, bulletproof glass has been used to shield the painting from any further attacks. Subsequently, on 21 April 1974, while the painting was on display at the Tokyo National Museum, a woman sprayed it with red paint as a protest against that museum’s failure to provide access for disabled people.[97] On 2 August 2009, a Russian woman, distraught over being denied French citizenship, threw a ceramic teacup purchased at the Louvre; the vessel shattered against the glass enclosure.[98][99] In both cases, the painting was undamaged.

In recent decades, the painting has been temporarily moved to accommodate renovations to the Louvre on three occasions: between 1992 and 1995, from 2001 to 2005, and again in 2019.[100] A new queuing system introduced in 2019 reduces the amount of time museum visitors have to wait in line to see the painting. After going through the queue, a group has about 30 seconds to see the painting.[101]

On 29 May 2022, a male activist, disguised as a woman in a wheelchair, threw cake at the protective glass covering the painting in an apparent attempt to raise awareness for climate change.[102] The painting was not damaged.[103] The man was arrested and placed in psychiatric care in the police headquarters.[104] An investigation was opened after the Louvre filed a complaint.[105]

Modern analysis

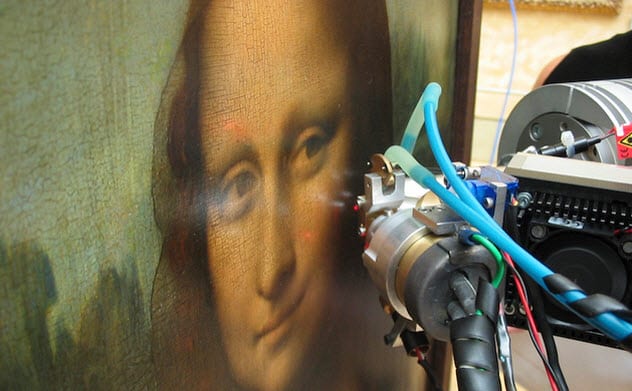

In the early 21st century, French scientist Pascal Cotte hypothesized a hidden portrait underneath the surface of the painting. He analyzed the painting in the Louvre with reflective light technology beginning in 2004, and produced circumstantial evidence for his theory.[106][107][108] Cotte admits that his investigation was carried out only in support of his hypotheses and should not be considered as definitive proof.[107][81] The underlying portrait appears to be of a model looking to the side, and lacks flanking columns,[109] but does not fit with historical descriptions of the painting. Both Vasari and Gian Paolo Lomazzo describe the subject as smiling,[16][110] unlike the subject in Cotte’s supposed portrait.[107][81] In 2020, Cotte published a study alleging that the painting has an underdrawing, transferred from a preparatory drawing via the spolvero technique.[111]

Conservation

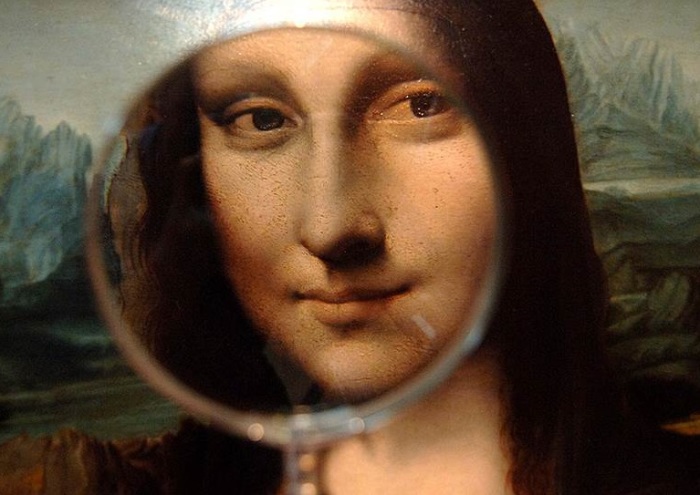

The tourist’s view in 2015

The Mona Lisa has survived for more than 500 years, and an international commission convened in 1952 noted that «the picture is in a remarkable state of preservation.»[73] It has never been fully restored,[112] so the current condition is partly due to a variety of conservation treatments the painting has undergone. A detailed analysis in 1933 by Madame de Gironde revealed that earlier restorers had «acted with a great deal of restraint.»[73] Nevertheless, applications of varnish made to the painting had darkened even by the end of the 16th century, and an aggressive 1809 cleaning and revarnishing removed some of the uppermost portion of the paint layer, resulting in a washed-out appearance to the face of the figure. Despite the treatments, the Mona Lisa has been well cared for throughout its history, and although the panel’s warping caused the curators «some worry»,[113] the 2004–05 conservation team was optimistic about the future of the work.[73]

Poplar panel

At some point, the Mona Lisa was removed from its original frame. The unconstrained poplar panel warped freely with changes in humidity, and as a result, a crack developed near the top of the panel, extending down to the hairline of the figure. In the mid-18th century to early 19th century, two butterfly-shaped walnut braces were inserted into the back of the panel to a depth of about one third the thickness of the panel. This intervention was skilfully executed, and successfully stabilized the crack. Sometime between 1888 and 1905, or perhaps during the picture’s theft, the upper brace fell out. A later restorer glued and lined the resulting socket and crack with cloth.[114][115]

The picture is kept under strict, climate-controlled conditions in its bulletproof glass case. The humidity is maintained at 50% ±10%, and the temperature is maintained between 18 and 21 °C. To compensate for fluctuations in relative humidity, the case is supplemented with a bed of silica gel treated to provide 55% relative humidity.[73]

Frame

Because the Mona Lisa‘s poplar support expands and contracts with changes in humidity, the picture has experienced some warping. In response to warping and swelling experienced during its storage during World War II, and to prepare the picture for an exhibit to honour the anniversary of Leonardo’s 500th birthday, the Mona Lisa was fitted in 1951 with a flexible oak frame with beech crosspieces. This flexible frame, which is used in addition to the decorative frame described below, exerts pressure on the panel to keep it from warping further. In 1970, the beech crosspieces were switched to maple after it was found that the beechwood had been infested with insects. In 2004–05, a conservation and study team replaced the maple crosspieces with sycamore ones, and an additional metal crosspiece was added for scientific measurement of the panel’s warp.[citation needed]

The Mona Lisa has had many different decorative frames in its history, owing to changes in taste over the centuries. In 1909, the art collector Comtesse de Béhague gave the portrait its current frame,[116] a Renaissance-era work consistent with the historical period of the Mona Lisa. The edges of the painting have been trimmed at least once in its history to fit the picture into various frames, but no part of the original paint layer has been trimmed.[73]

Cleaning and touch-up

The first and most extensive recorded cleaning, revarnishing, and touch-up of the Mona Lisa was an 1809 wash and revarnishing undertaken by Jean-Marie Hooghstoel, who was responsible for restoration of paintings for the galleries of the Musée Napoléon. The work involved cleaning with spirits, touch-up of colour, and revarnishing the painting. In 1906, Louvre restorer Eugène Denizard performed watercolour retouches on areas of the paint layer disturbed by the crack in the panel. Denizard also retouched the edges of the picture with varnish, to mask areas that had been covered initially by an older frame. In 1913, when the painting was recovered after its theft, Denizard was again called upon to work on the Mona Lisa. Denizard was directed to clean the picture without solvent, and to lightly touch up several scratches to the painting with watercolour. In 1952, the varnish layer over the background in the painting was evened out. After the second 1956 attack, restorer Jean-Gabriel Goulinat was directed to touch up the damage to Mona Lisa‘s left elbow with watercolour.[73]

In 1977, a new insect infestation was discovered in the back of the panel as a result of crosspieces installed to keep the painting from warping. This was treated on the spot with carbon tetrachloride, and later with an ethylene oxide treatment. In 1985, the spot was again treated with carbon tetrachloride as a preventive measure.[73]

Using modern digital filters and advanced AI methods original features of Monalisa’s portrait are being restored as close as possible to the original painting as shown on the right.

The white patches are removed from the facial portion of the original digital image with the help of advanced digital filters.

Digital restoration of Monalisa’s face using modern AI and signal processing algorithms

Display

On 6 April 2005—following a period of curatorial maintenance, recording, and analysis—the painting was moved to a new location within the museum’s Salle des États. It is displayed in a purpose-built, climate-controlled enclosure behind bulletproof glass.[117] Since 2005 the painting has been illuminated by an LED lamp, and in 2013 a new 20 watt LED lamp was installed, specially designed for this painting. The lamp has a Colour Rendering Index up to 98, and minimizes infrared and ultraviolet radiation which could otherwise degrade the painting.[118] The renovation of the gallery where the painting now resides was financed by the Japanese broadcaster Nippon Television.[119] As of 2019, about 10.2 million people view the painting at the Louvre each year.[120]

On the 500th anniversary of the master’s death, the Louvre held the largest ever single exhibit of Leonardo works, from 24 October 2019 to 24 February 2020. The Mona Lisa was not included because it is in such great demand among visitors to the museum; the painting remained on display in its gallery.[121][122]

Legacy

The Mona Lisa began influencing contemporary Florentine painting even before its completion. Raphael, who had been to Leonardo’s workshop several times, promptly used elements of the portrait’s composition and format in several of his works, such as Young Woman with Unicorn (c. 1506),[123] and Portrait of Maddalena Doni (c. 1506).[64] Later paintings by Raphael, such as La velata (1515–16) and Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (c. 1514–15), continued to borrow from Leonardo’s painting. Zollner states that «None of Leonardo’s works would exert more influence upon the evolution of the genre than the Mona Lisa. It became the definitive example of the Renaissance portrait and perhaps for this reason is seen not just as the likeness of a real person, but also as the embodiment of an ideal.»[124]

Early commentators such as Vasari and André Félibien praised the picture for its realism, but by the Victorian era, writers began to regard the Mona Lisa as imbued with a sense of mystery and romance. In 1859, Théophile Gautier wrote that the Mona Lisa was a «sphinx of beauty who smiles so mysteriously» and that «Beneath the form expressed one feels a thought that is vague, infinite, inexpressible. One is moved, troubled … repressed desires, hopes that drive one to despair, stir painfully.» Walter Pater’s famous essay of 1869 described the sitter as «older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in the deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her.»[125]

By the early 20th century, some critics started to feel the painting had become a repository for subjective exegeses and theories.[126] Upon the painting’s theft in 1911, Renaissance historian Bernard Berenson admitted that it had «simply become an incubus, and [he] was glad to be rid of her.»[126][127] Jean Metzinger’s Le goûter (Tea Time) was exhibited at the 1911 Salon d’Automne and was sarcastically described as «la Joconde à la cuiller» (Mona Lisa with a spoon) by art critic Louis Vauxcelles on the front page of Gil Blas.[128] André Salmon subsequently described the painting as «The Mona Lisa of Cubism».[129][130]

The avant-garde art world has made note of the Mona Lisa‘s undeniable popularity. Because of the painting’s overwhelming stature, Dadaists and Surrealists often produce modifications and caricatures. In 1883, Le rire, an image of a Mona Lisa smoking a pipe, by Sapeck (Eugène Bataille), was shown at the «Incoherents» show in Paris. In 1919, Marcel Duchamp, one of the most influential modern artists, created L.H.O.O.Q., a Mona Lisa parody made by adorning a cheap reproduction with a moustache and goatee. Duchamp added an inscription, which when read out loud in French sounds like «Elle a chaud au cul» meaning: «she has a hot ass», implying the woman in the painting is in a state of sexual excitement and intended as a Freudian joke.[131] According to Rhonda R. Shearer, the apparent reproduction is in fact a copy partly modelled on Duchamp’s own face.[132]

Salvador Dalí, famous for his surrealist work, painted Self portrait as Mona Lisa in 1954.[133] Andy Warhol created serigraph prints of multiple Mona Lisas, called Thirty Are Better than One, following the painting’s visit to the United States in 1963.[134] The French urban artist known pseudonymously as Invader has created versions of the Mona Lisa on city walls in Paris and Tokyo using a mosaic style.[135] A 2014 New Yorker magazine cartoon parodies the supposed enigma of the Mona Lisa smile in an animation showing progressively more maniacal smiles.

-

-

-

Le rire (The Laugh) by Eugène Bataille, or Sapeck (1883)

-

-

Fame

2014: Mona Lisa is among the greatest attractions in the Louvre.

Today the Mona Lisa is considered the most famous painting in the world, a destination painting, but until the 20th century it was simply one among many highly regarded artworks.[136]

Once part of King Francis I of France’s collection, the Mona Lisa was among the first artworks to be exhibited in the Louvre, which became a national museum after the French Revolution. Leonardo began to be revered as a genius, and the painting’s popularity grew in the mid-19th century when French intelligentsia praised it as mysterious and a representation of the femme fatale.[137] The Baedeker guide in 1878 called it «the most celebrated work of Leonardo in the Louvre»,[138] but the painting was known more by the intelligentsia than the general public.[139]

The 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa and its subsequent return was reported worldwide, leading to a massive increase in public recognition of the painting. During the 20th century it was an object for mass reproduction, merchandising, lampooning and speculation, and was claimed to have been reproduced in «300 paintings and 2,000 advertisements».[138] The Mona Lisa was regarded as «just another Leonardo until early last century, when the scandal of the painting’s theft from the Louvre and subsequent return kept a spotlight on it over several years.»[140]

From December 1962 to March 1963, the French government lent it to the United States to be displayed in New York City and Washington, D.C.[141][142] It was shipped on the new ocean liner SS France.[143] In New York, an estimated 1.7 million people queued «in order to cast a glance at the Mona Lisa for 20 seconds or so.»[138] While exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the painting was nearly drenched in water because of a faulty sprinkler, but the painting’s bullet-proof glass case protected it.[144]

In 1974, the painting was exhibited in Tokyo and Moscow.[145]

In 2014, 9.3 million people visited the Louvre.[146] Former director Henri Loyrette reckoned that «80 percent of the people only want to see the Mona Lisa.»[147]

Financial worth

Before the 1962–1963 tour, the painting was assessed for insurance at $100 million (equivalent to $700 million in 2021), making it, in practice, the most highly-valued painting in the world. The insurance was not purchased; instead, more was spent on security.[148]

In 2014, a France 24 article suggested that the painting could be sold to help ease the national debt, although it was observed that the Mona Lisa and other such art works were prohibited from being sold by French heritage law, which states that «Collections held in museums that belong to public bodies are considered public property and cannot be otherwise.»[149]

Cultural depictions

Cultural depictions of the Mona Lisa include:

- The 1915 Mona Lisa by German composer Max von Schillings.

- Two 1930s films written about the theft, (The Theft of the Mona Lisa and Arsène Lupin).

- The 1950 song «Mona Lisa» recorded by Nat King Cole.

- The 2011 song «The Ballad of Mona Lisa» by American rock band Panic! at the Disco.

- The 2022 mystery film Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery depicts the destruction of the Mona Lisa, which has been borrowed from its location by a rich billionaire.

Early versions and copies

Prado Museum La Gioconda

A version of Mona Lisa known as Mujer de mano de Leonardo Abince («Woman by Leonardo da Vinci’s hand», Museo del Prado, Madrid) was for centuries considered to be a work by Leonardo. However, since its restoration in 2012, it is now thought to have been executed by one of Leonardo’s pupils in his studio at the same time as Mona Lisa was being painted.[150] The Prado’s conclusion that the painting is probably by Salaì (1480–1524) or by Melzi (1493–1572) has been called into question by others.[151]

The restored painting is from a slightly different perspective than the original Mona Lisa, leading to the speculation that it is part of the world’s first stereoscopic pair.[152][153][154] However, a more recent report has demonstrated that this stereoscopic pair in fact gives no reliable stereoscopic depth.[155]

Isleworth Mona Lisa

A version of the Mona Lisa known as the Isleworth Mona Lisa was first bought by an English nobleman in 1778 and was rediscovered in 1913 by Hugh Blaker, an art connoisseur. The painting was presented to the media in 2012 by the Mona Lisa Foundation.[156] It is a painting of the same subject as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The current scholarly consensus on attribution is unclear.[157] Some experts, including Frank Zöllner, Martin Kemp and Luke Syson denied the attribution to Leonardo;[158][159] professors such as Salvatore Lorusso, Andrea Natali,[160] and John F Asmus supported it;[161] others like Alessandro Vezzosi and Carlo Pedretti were uncertain.[162]

Hermitage Mona Lisa

A version known as the Hermitage Mona Lisa is in the Hermitage Museum and it was made by an unknown 16th-century artist. [163][164]

-

Copy of Mona Lisa commonly attributed to Salaì

-

The Prado Museum La Gioconda

-

-

The Mona Lisa Illusion

If a person being photographed looks into the camera lens the image produced provides an illusion that viewers perceive as the subject looking at them, irrespective of the photographs’ position. Presumably it is for this reason that many people, while taking photographs, ask subjects to look at the camera rather than anywhere else. In psychology, this is known as «the Mona Lisa illusion» after the famous painting which also presents the same illusion.[165]

See also

- List of most expensive paintings

- List of stolen paintings

- Speculations about Mona Lisa

- Male Mona Lisa theories

- Two-Mona Lisa theory

References

Footnotes

- ^ Some researchers claim that it was common at this time for genteel women to pluck these hairs, as they were considered unsightly.[44][45]

- ^ Leonardo, later in his life, is said to have regretted «never having completed a single work».[63]

- ^ «… Messer Lunardo Vinci [sic] … showed His Excellency three pictures, one of a certain Florentine lady done from life at the instance of the late Magnificent, Giuliano de’ Medici.»[77]

- ^ «Possibly it was another portrait of which no record and no copies exist—Giuliano de’ Medici surely had nothing to do with the Mona Lisa—the probability is that the secretary, overwhelmed as he must have been at the time, inadvertently dropped the Medici name in the wrong place.»[77]

- ^ Along with The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist

Citations

- ^ «The Mona Lisa’s Twin Painting Discovered». All Things Considered. 2 February 2012. National Public Radio.

The original Mona Lisa in the Louvre is difficult to see — it’s covered with layers of varnish, which has darkened over the decades and the centuries, and even cracked’, Bailey says

- ^ «Theft of the Mona Lisa». Treasures of the World. PBS.

time has aged and darkened her complexion.

- ^ a b Sassoon, Donald (2001). Mona Lisa: The History of the World’s Most Famous Painting. HarperCollins. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-00-710614-1.

It is actually quite dirty, partly due to age and partly to the darkening of a varnish applied in the sixteenth century.

- ^ «The Theft That Made Mona Lisa a Masterpiece». All Things Considered. 30 July 2011. NPR. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (21 September 2001). «Why I think Mona Lisa became an icon». Times Higher Education.

- ^ Lichfield, John (1 April 2005). «The Moving of the Mona Lisa». The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Philip (23 June 2004). «Noisy secret of Mona Lisa’s». New Scientist. Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ a b «Mona Lisa – Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo». Musée du Louvre. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ «Mona Lisa – Heidelberger find clarifies identity». University Library Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 8 May 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ «Was the ‘Mona Lisa’ Leonardo’s Male Lover?». Artnet News. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b Carrier, David (31 May 2006). Museum Skepticism: A History of the Display of Art in Public Galleries. Duke University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8223-3694-5.

- ^ Charney, N.; Fincham, D.; Charney, U. (2011). The Thefts of the Mona Lisa: On Stealing the World’s Most Famous Painting. Arca Publications. ISBN 978-0-615-51902-9. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ «Highest insurance valuation for a painting». Guinness World Records. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ «German experts crack the ID of ‘Mona Lisa’«. Today. Reuters. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Nizza, Mike (15 January 2008). «Mona Lisa’s Identity, Solved for Good?». The New York Times. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ a b Italian: Prese Lionardo a fare per Francesco del Giocondo il ritratto di monna Lisa sua moglie Vasari 1879, p. 39

- ^ a b Clark, Kenneth (March 1973). «Mona Lisa». The Burlington Magazine. 115 (840): 144–151. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 877242.

- ^ «Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori (1568)/Lionardo da Vinci — Wikisource». it.wikisource.org (in Italian). Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ «Giorgio Vasari — Leonardo e la Gioconda». Libriantichionline.com (in Italian). Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ «Ricerca | Garzanti Linguistica». www.garzantilinguistica.it. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ «Dizionario Italiano online Hoepli — Parola, significato e traduzione». dizionari.hoepli.it/. Retrieved 15 November 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Kemp 2006, pp. 261–262

- ^ Farago 1999, p. 123

- ^ a b Bartz & König 2001, p. 626.

- ^ a b «Mona Lisa – Heidelberg discovery confirms identity». University of Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ a b Delieuvin, Vincent (15 January 2008). «Télématin». Journal Télévisé. France 2 Télévision.

- ^ Zöllner 2019, p. 241

- ^ Stites, Raymond S. (January 1936). «Mona Lisa—Monna Bella». Parnassus. 8 (1): 7–10, 22–23. doi:10.2307/771197. JSTOR 771197.

- ^ a b Wilson 2000, pp. 364–366

- ^ Debelle, Penelope (25 June 2004). «Behind that secret smile». The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ Johnston, Bruce (8 January 2004). «Riddle of Mona Lisa is finally solved: she was the mother of five». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ a b Chaundy, Bob (29 September 2006). «Faces of the Week». BBC. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Nicholl, Charles (28 March 2002). «The myth of the Mona Lisa». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ Kington, Tom (9 January 2011). «Mona Lisa backdrop depicts Italian town of Bobbio, claims art historian». The Guardian. London.

- ^ Kobbé, Gustav (1916). «The Smile of the «Mona Lisa»«. The Lotus Magazine. 8 (2): 67–74. ISSN 2150-5977. JSTOR 20543781.

- ^ «Opinion | Couldn’t ‘Mona Lisa’ Just Stay a Mystery?». The New York Times. 9 January 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ a b Zöllner, Frank (2000). Leonardo Da Vinci, 1452–1519. ISBN 978-3-8228-5979-7.

- ^ «E.H. Gombrich, The Story of Art«. Artchive.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ Zöllner, Frank. «Leonardo’s Portrait of Mona Lisa del Giocondo» (PDF). p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2014.

- ^ a b Woods-Marsden p. 77 n. 100

- ^ Farago 1999, p. 372

- ^ «The Mona Lisa (La Gioconda)». BBC. 25 October 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1991) [1568]. The Lives of the Artists. Oxford World’s Classics. Translated by Bondanella, Peter; Bondanella, Julia Conway. Oxford University Press. p. 294. ISBN 0-19-283410-X.

The eyebrows could not be more natural, for they represent the way the hair grows in the skin—thicker in some places and thinner in others, following the pores of the skin.

- ^ Turudich 2003, p. 198

- ^ McMullen, Roy (1976). Mona Lisa: The Picture and the Myth. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-333-19169-9.

- ^ Holt, Richard (22 October 2007). «Solved: Why Mona Lisa doesn’t have eyebrows». The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (9 December 2015). «Lurking Beneath the ‘Mona Lisa’ May Be the Real One». Livescience.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015.

- ^ Irene Earls, Artists of the Renaissance, Greenwood Press, 2004, p. 113. ISBN 0-313-31937-5

- ^ a b Salgueiro, Heliana Angotti (2000). Paisaje y art. University of São Paulo. p. 74. ISBN 978-85-901430-1-7.

- ^ «BBC NEWS – Entertainment – Mona Lisa smile secrets revealed». 18 February 2003. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007.

- ^ Rosetta Borchia and Olivia Nesci, Codice P. Atlante illustrato del reale paesaggio della Gioconda, Mondadori Electa, 2012, ISBN 978-88-370-9277-1

- ^ «Researchers identify landscape behind the Mona Lisa». The Times. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ Chiesa 1967, p. 103.

- ^ Chiesa 1967, p. 87.

- ^ Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2005). An Age of Voyages, 1350–1600. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-517672-8.

- ^ Vezzosi, Alessandro (2007). «The Gioconda mystery – Leonardo and the ‘common vice of painters’«. In Vezzosi; Schwarz; Manetti (eds.). Mona Lisa: Leonardo’s hidden face. Polistampa. ISBN 978-88-596-0258-3.

- ^ Asmus, John F.; Parfenov, Vadim; Elford, Jessie (28 November 2016). «Seeing double: Leonardo’s Mona Lisa twin». Optical and Quantum Electronics. 48 (12): 555. doi:10.1007/s11082-016-0799-0. S2CID 125226212.

- ^ Leonardo, Carmen Bambach, Rachel Stern, and Alison Manges (2003). Leonardo da Vinci, master draftsman. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 234. ISBN 1-58839-033-0

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella (10 May 2016). «Did a Stroke Kill Leonardo da Vinci?». Seeker. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ McMahon, Barbara (1 May 2005). «Da Vinci ‘paralysis left Mona Lisa unfinished’«. The Guardian. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Saplakoglu, Yasemin (4 May 2019). «A Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci May Reveal Why He Never Finished the Mona Lisa». Live Science. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Bodkin, Henry (4 May 2019). «Leonardo da Vinci never finished the Mona Lisa because he injured his arm while fainting, experts say». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Henry; Lee Thomas, Dana (1940). Living biographies of great painters. Garden City Publishing Co., Inc. p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Becherucci, Luisa (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 50.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (March 1973). «Mona Lisa». Burlington Magazine. Vol. 115.

- ^ a b c Lorusso, Salvatore; Natali, Andrea (2015). «Mona Lisa: A comparative evaluation of the different versions and copies». Conservation Science. 15: 57–84. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ a b c Isbouts, Jean-Pierre; Heath-Brown, Christopher (2013). The Mona Lisa Myth. Santa Monica, California: Pantheon Press. ISBN 978-1-4922-8949-4.

- ^ Friedenthal, Richard (1959). Leonardo da Vinci: a pictorial biography. New York: Viking Press.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (1981). Leonardo: The marvelous works of nature and man. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-52460-6.

- ^ Bramly, Serge (1995). Leonardo: The artist and the man. London: Penguin books. ISBN 978-0-14-023175-5.

- ^ Marani, Pietro (2003). Leonardo: The complete paintings. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-9159-0.

- ^ a b Zollner, Frank (1993). «Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait of Mona Lisa de Giocondo» (PDF). Gazette des Beaux Arts. 121: 115–138. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mohen, Jean-Pierre (2006). Mona Lisa: inside the Painting. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8109-4315-5.

- ^ Delieuvin, Vincent; Tallec, Olivier (2017). What’s so special about Mona Lisa. Paris: Editions du musée du Louvre. ISBN 978-2-35031-564-5.

- ^ De Beatis, Antonio (1979) [1st pub.:1517]. Hale, J.R.; Lindon, J.M.A. (eds.). The travel journal of Antonio de Beatis: Germany, Switzerland, the Low Countries, France and Italy 1517–1518. London, England: Haklyut Society.

- ^ Bacci, Mina (1978) [1963]. The Great Artists: Da Vinci. Translated by Tanguy, J. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ a b c Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 163–64.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1550). Le Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori. Florence, Italy: Lorenzo Torrentino.

- ^ a b Boudin de l’Arche, Gerard (2017). A la recherche de Monna Lisa. Cannes, France: Edition de l’Omnibus. ISBN 979-10-95833-01-7.

- ^ Louvre Museum. «Mona Lisa». louvre.fr. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Kemp, Martin; Pallanti, Giuseppe (2017). Mona Lisa: The people and the painting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874990-5.

- ^ Jestaz, Bertrand (1999). «Francois 1er, Salai, et les tableaux de Léonard». Revue de l’Art (in French). 76: 68–72. doi:10.3406/rvart.1999.348476.

- ^ a b Classics, Delphi; Russell, Peter (7 April 2017). The History of Art in 50 Paintings (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-78656-508-2.

- ^ «The Theft That Made The ‘Mona Lisa’ A Masterpiece». NPR. 30 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ Bohm-Duchen, Monica (2001). The private life of a masterpiece. University of California Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-520-23378-2. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Halpern, Jack (9 January 2019). «The French Burglar Who Pulled Off His Generation’s Biggest Art Heist». The New Yorker. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ «Theft of the Mona Lisa». Stoner Productions via Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ R. A. Scotti (April 2010). Vanished Smile: The Mysterious Theft of the Mona Lisa. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-307-27838-8. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ a b «Top 25 Crimes of the Century: Stealing the Mona Lisa, 1911». TIME. 2 December 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ Sale, Jonathan (8 May 2009). «Review: The Lost Mona Lisa: The Extraordinary True Story of the Greatest Art Theft in History by RA Scotti». The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Iqbal, Nosheen; Jonze, Tim (22 January 2020). «In pictures: The greatest art heists in history». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b The Lost Mona Lisa by R. A. Scotti (Random House, 2010)[page needed]

- ^ «Noah Charney, Chronology of the Mona Lisa: History and Thefts, The Secret History of Art, Blouin Artinfo Blogs». Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Nilsson, Jeff (7 December 2013). «100 Years Ago: The Mastermind Behind the Mona Lisa Heist | The Saturday Evening Post». Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ «Mona FAQ». Mona Lisa Mania. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ «Tourist Damages the ‘Mona Lisa’«. The New York Times. 31 December 1956.

- ^ «‘Mona Lisa’ Still Smiling, Undamaged After Woman’s Spray Attack in Tokyo». Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 21 April 1974. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ «Mona Lisa attacked by Russian woman». Xinhua News Agency. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ^ «Russian tourist hurls mug at Mona Lisa in Louvre». Associated Press. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Guenfoud, Ibtissem (17 July 2019). «‘Mona Lisa’ relocated within Louvre for 1st time since 2005″. ABC News. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Samuel, Henry (7 October 2019). «Will new Mona Lisa queuing system in restored Louvre gallery bring a smile back to visitors’ faces?». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ «Man in wig throws cake at glass protecting Mona Lisa». ABC News. Associated Press. 30 May 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Hummel, Tassilo (30 May 2022). Stonestreet, John (ed.). «Mona Lisa left unharmed but smeared in cream in climate protest stunt». Reuters. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ «Man arrested after Mona Lisa smeared with cake». The Guardian. 30 May 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ Palumbo, Jacqui (31 May 2022). «The ‘Mona Lisa’ has been caked in attempted vandalism stunt». CNN. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ «Hidden portrait ‘found under Mona Lisa’, says French scientist». BBC News. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Cotte, Pascal (2015). Lumiere on the Mona Lisa: Hidden portraits. Paris: Vinci Editions. ISBN 978-2-9548-2584-7.

- ^ McAloon, Jonathan (10 December 2015). «The Missing Mona Lisa». Apollo. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015.

- ^ «Secret Portrait Hidden Under Mona Lisa, Claims French Scientist». Newsweek. 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Lomazzo, Gian Paolo (1584). Treatise on the art of painting. Milan.

- ^ Cotte, Pascal; Simonot, Lionel (1 September 2020). «Mona Lisa’s spolvero revealed». Journal of Cultural Heritage. 45: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2020.08.004. ISSN 1296-2074. S2CID 225304838.

- ^ Kalb, Claudia (1 May 2019). «Why Leonardo da Vinci’s brilliance endures, 500 years after his death». National Geographic. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ «Ageing Mona Lisa worries Louvre». BBC News. 26 April 2004. Archived from the original on 16 August 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Bramly, Serge (1996). Mona Lisa. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23717-5.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (2006). Leonardo and the Mona Lisa Story: The History of a Painting Told in Pictures. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-902-9.

- ^ «Biographical index of collectors of pastels». Pastellists.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ «Mona Lisa gains new Louvre home». BBC. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Fontoynont, Marc et al. «Lighting Mona Lisa with LEDs Archived 8 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine» Note Archived 29 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. SBI / Aalborg University, June 2013.

- ^ «Nippon Television Network Corporation». Ntv.co.jp. 6 April 2005. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ «Mona Lisa fans decry brief encounter with their idol in Paris». The Guardian. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Leonardo da Vinci’s Unexamined Life as a Painter». The Atlantic. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ «Louvre exhibit has most da Vinci paintings ever assembled». Aleteia. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- ^ Zollner gives a date of c. 1504, most others say c. 1506

- ^ Zöllner, Frank. Leonardo Da Vinci, 1452–1519. p. 161.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1999). «Mona Lisa». In Farago, Claire J. (ed.). Leonardo Da Vinci, Selected Scholarship: Leonardo’s projects, c. 1500–1519. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8153-2935-0.

- ^ a b «The myth of the Mona Lisa». The Guardian. 28 March 2002. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017.

- ^ Samuels, Ernest; Samuels, Jayne (1987). Bernard Berenson, the Making of a Legend. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-674-06779-0.

- ^ «Gil Blas / dir. A. Dumont». Gallica. 30 September 1911.

- ^ Salmon, André (15 September 1920). «L’Art vivant». Paris : G. Crès – via Internet Archive.

- ^ «Philadelphia Museum of Art – Collections Object : Tea Time (Woman with a Teaspoon)». www.philamuseum.org.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (26 May 2001). «L.H.O.O.Q., Marcel Duchamp (1919)». The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ Marting, Marco De (2003). «Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache?». Art Science Research Laboratory. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ^ Dalí, Salvador. «Self Portrait as Mona Lisa». Mona Lisa Images for a Modern World by Robert A. Baron (from the catalog of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, p. 195). Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald (2003). Becoming Mona Lisa. Harvest Books via Amazon Search Inside. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-15-602711-3.

- ^ «The £20,000 Rubik’s Cube Mona Lisa». metro.co.uk. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Riding, Alan (6 April 2005). «In Louvre, New Room With View of ‘Mona Lisa’«. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ Sassoon, Donald. «Why is the Mona Lisa Famous?». La Trobe University Podcast. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Sassoon, Donald (2001). «Mona Lisa: the Best-Known Girl in the Whole Wide World». History Workshop Journal (vol 2001 ed.). 2001 (51): 1. doi:10.1093/hwj/2001.51.1. ISSN 1477-4569.

- ^ «The Theft That Made The ‘Mona Lisa’ A Masterpiece». All Things Considered. NPR. 30 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Gopnik, Blake (7 May 2004). «A Record Picasso and the Hype Price of Status Objects». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ «The Mona Lisa» (PDF). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Stolow, Nathan (1987). Conservation and exhibitions: packing, transport, storage, and environmental consideration. Butterworths. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-408-01434-2. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ «Today in Met History: February 4». Metropolitan Museum of Art. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ «Another art anniversary: Mona Lisa comes to New York! And she’s almost drowned in a sprinkler malfunction». boweryboyshistory.com. 13 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Bohm-Duchen, Monica (2001). The private life of a masterpiece. University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-520-23378-2. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ The French Ministry of Foreign affairs. «The Louvre, the most visited museum in the world (01.15)». France Diplomatie :: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- ^ «On a Mission to Loosen Up the Louvre». The New York Times. 11 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016.

- ^ Young, Mark, ed. (1999). The Guinness Book of World Records 1999. Bantam Books. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-553-58075-4.

- ^ «Culture – Could France sell the Mona Lisa to pay off its debts?». France 24. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015.

- ^ «La Gioconda, Leonardo’s atelier». Museo Nacional del Prado. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ «The ‘Prado Mona Lisa’ – The Mona Lisa Foundation». The Mona Lisa Foundation. 11 September 2012. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Carbon, C. C.; Hesslinger, V. M. (August 2013). «Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa Entering the Next Dimension». Perception. 42 (8): 887–893. doi:10.1068/p7524. PMID 24303752.

- ^ Carbon, Claus-Christian; Hesslinger, Vera M. (2015). «Restoring Depth to Leonardo’s Mona Lisa». American Scientist. 103 (6): 404–409. doi:10.1511/2015.117.1.(subscription required)

- ^ Tweened animated gif of Mona Lisa and Prado version Archived 7 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine by Carbon and Hesslinger

- ^ Brooks, K. R. (1 January 2017). «Depth Perception and the History of Three-Dimensional Art: Who Produced the First Stereoscopic Images?». i-Perception. 8 (1): 204166951668011. doi:10.1177/2041669516680114. PMC 5298491. PMID 28203349.

- ^ Dutta, Kunal (15 December 2014). «‘Early Mona Lisa’: Unveiling the one-in-a-million identical twin to Leonardo da Vinci painting». Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Matthew (27 September 2012). «Second Mona Lisa Unveiled for First Time in 40 Years». ABC News. ABC News Internet Ventures. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Alastair Sooke. «The Isleworth Mona Lisa: A second Leonardo masterpiece?». BBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

- ^ «New proof said found for «original» Mona Lisa –». Reuters.com. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Lorusso, Salvatore; Natali, Andrea (January 2015). «Mona Lisa: A Comparative Evaluation of the Different Versions and Their Copies». Conservation Science in Cultural Heritage. 15: 80. doi:10.6092/issn.1973-9494/6168.

- ^ Asmus, John F. (1 July 1989). «Computer Studies of the Isleworth and Louvre Mona Lisas». Optical Engineering. 28 (7): 800–804. Bibcode:1989OptEn..28..800A. doi:10.1117/12.7977036. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Kemp 2018: «Alessandro Vezzosi, who spoke at the launch in Geneva, and Carlo Pedretti, the great Leonardo specialist, made encouraging but noncommittal statements about the picture being of high quality and worthy of further research.»

- ^ Portrait of Gioconda (copy), hermitagemuseum.org.

- ^ Mastromattei, Dario (16 February 2016). «La Gioconda (o Monna Lisa) di Leonardo da Vinci: analisi».

- ^ Horstmann G, Loth S (2019). «The Mona Lisa Illusion-Scientists See Her Looking at Them Though She Isn’t». Iperception. 10 (1). doi:10.1177/2041669518821702. PMC 6327345. PMID 30671222.

Sources

- Bartz, Gabriele; König, Eberhard (2001). Art and architecture, Louvre. New York, New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-2577-1.

- Bohm-Duchen, Monica (2001). The private life of a masterpiece. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23378-2.

- Chiesa, Angela Ottino della (1967). The Complete Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. Penguin Classics of World Art. London, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-008649-2.

- Farago, Claire J. (1999). Leonardo’s projects, c. 1500–1519. Oxford, England: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-2935-0.

- Kemp, Martin (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvelous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280725-0.

- Kemp, Martin (2018). Living with Leonardo: Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond. London, England: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-77423-6.

- Kemp, Martin (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The 100 Milestones. New York City, New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4549-304-26.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2003) [2000]. Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings. New York City, New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3581-5.

- Turudich, Daniela (2003). Plucked, Shaved & Braided: Medieval and Renaissance Beauty and Grooming Practices 1000–1600. North Branford, Connecticut: Streamline Press. ISBN 978-1-930064-08-9.

- Vasari, Giorgio (1879) [1550]. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori (in Italian). Vol. 4. Florence: G.C. Sansoni.

- Wilson, Colin (2000). The Mammoth Encyclopedia of the Unsolved. New York, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-0793-5.

- Woods-Marsden, Joanna (2001). «Portrait of the Lady, 1430–1520». In Brown, David Alan (ed.). Virtue & Beauty. London: Princeton University Press. pp. 64–87. ISBN 978-0-691-09057-3.

- Zöllner, Frank (2015). Leonardo (2nd ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-0215-3.

- Zöllner, Frank (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings (Anniversary ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-7625-3.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mona Lisa.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Mona Lisa.

- Sassoon, Donald, Prof. (21 January 2014). #26: Why is the Mona Lisa Famous?. La Trobe University podcast blog. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) of the podcast audio. - «Mona Lisa, Leonardo’s Earlier Version». Zürich, Switzerland: The Mona Lisa Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- «True Colors of the Mona Lisa Revealed» (Press release). Paris: Lumiere Technology. 19 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Scientific analyses conducted by the Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France (C2RMF) Compare layers of the painting as revealed by x-radiography, infrared reflectographya and ultraviolet fluorescence

- «Stealing Mona Lisa«. Dorothy & Thomas Hoobler. May 2009. excerpt of book. Vanity Fair

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Martin Kemp: Art Detective Podcast, 18 Jan 2017

- Leonardo’s Mona Lisa Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Smarthistory (video)

- Secrets of the Mona Lisa, Discovery Channel documentary on YouTube

| Mona Lisa | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Gioconda, Monna Lisa | |

The Mona Lisa digitally retouched to reduce the effects of aging. The unretouched image is darker.[1][2][3] |

|

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1503–1506, perhaps continuing until c. 1517 |

| Medium | Oil on poplar panel |

| Subject | Lisa Gherardini |

| Dimensions | 77 cm × 53 cm (30 in × 21 in) |

| Location | Louvre, Paris |

The Mona Lisa ( MOH-nə LEE-sə; Italian: Gioconda [dʒoˈkonda] or Monna Lisa [ˈmɔnna ˈliːza]; French: Joconde [ʒɔkɔ̃d]) is a half-length portrait painting by Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. Considered an archetypal masterpiece of the Italian Renaissance,[4][5] it has been described as «the best known, the most visited, the most written about, the most sung about, the most parodied work of art in the world».[6] The painting’s novel qualities include the subject’s enigmatic expression,[7] the monumentality of the composition, the subtle modelling of forms, and the atmospheric illusionism.[8]

The painting has been definitively identified to depict Italian noblewoman Lisa Gherardini,[9] the wife of Francesco del Giocondo. It is painted in oil on a white Lombardy poplar panel. Leonardo never gave the painting to the Giocondo family, and later it is believed he left it in his will to his favored apprentice Salaì.[10] It had been believed to have been painted between 1503 and 1506; however, Leonardo may have continued working on it as late as 1517. It was acquired by King Francis I of France and is now the property of the French Republic. It has been on permanent display at the Louvre in Paris since 1797.[11]

The painting’s global fame and popularity stem from its 1911 theft by Vincenzo Peruggia, who attributed his actions to Italian patriotism – a belief that the painting should belong to Italy. The theft and subsequent recovery in 1914 generated unprecedented publicity for an art theft, and led to the publication of numerous cultural depictions such as the 1915 opera Mona Lisa, two early 1930s films about the theft (The Theft of the Mona Lisa and Arsène Lupin) and the popular song Mona Lisa recorded by Nat King Cole – one of the most successful songs of the 1950s.[12]

The Mona Lisa is one of the most valuable paintings in the world. It holds the Guinness World Record for the highest-known painting insurance valuation in history at US$100 million in 1962[13] (equivalent to $870 million in 2021).

Title and subject

The title of the painting, which is known in English as Mona Lisa, is based on the presumption that it depicts Lisa del Giocondo, although her likeness is uncertain. Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote that «Leonardo undertook to paint, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife.»[16][17][18][19] Monna in Italian is a polite form of address originating as ma donna—similar to Ma’am, Madam, or my lady in English. This became madonna, and its contraction monna. The title of the painting, though traditionally spelled Mona in English, is spelled in Italian as Monna Lisa (mona being a vulgarity in Italian), but this is rare in English.[20][21]

Lisa del Giocondo was a member of the Gherardini family of Florence and Tuscany, and the wife of wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo.[22] The painting is thought to have been commissioned for their new home, and to celebrate the birth of their second son, Andrea.[23] The Italian name for the painting, La Gioconda, means ‘jocund’ (‘happy’ or ‘jovial’) or, literally, ‘the jocund one’, a pun on the feminine form of Lisa’s married name, Giocondo.[22][24] In French, the title La Joconde has the same meaning.

Vasari’s account of the Mona Lisa comes from his biography of Leonardo published in 1550, 31 years after the artist’s death. It has long been the best-known source of information on the provenance of the work and identity of the sitter. Leonardo’s assistant Salaì, at his death in 1524, owned a portrait which in his personal papers was named la Gioconda, a painting bequeathed to him by Leonardo.[citation needed]

That Leonardo painted such a work, and its date, were confirmed in 2005 when a scholar at Heidelberg University discovered a marginal note in a 1477 printing of a volume by ancient Roman philosopher Cicero. Dated October 1503, the note was written by Leonardo’s contemporary Agostino Vespucci. This note likens Leonardo to renowned Greek painter Apelles, who is mentioned in the text, and states that Leonardo was at that time working on a painting of Lisa del Giocondo.[25]

In response to the announcement of the discovery of this document, Vincent Delieuvin, the Louvre representative, stated «Leonardo da Vinci was painting, in 1503, the portrait of a Florentine lady by the name of Lisa del Giocondo. About this we are now certain. Unfortunately, we cannot be absolutely certain that this portrait of Lisa del Giocondo is the painting of the Louvre.»[26]

The catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci (2019) confirms that the painting probably depicts Lisa del Giocondo, with Isabella d’Este being the only plausible alternative.[27] Scholars have developed several alternative views, arguing that Lisa del Giocondo was the subject of a different portrait, and identifying at least four other paintings referred to by Vasari as the Mona Lisa.[28] Several other people have been proposed as the subject of the painting,[29] including Isabella of Aragon,[30] Cecilia Gallerani,[31] Costanza d’Avalos, Duchess of Francavilla,[29] Pacifica Brandano/Brandino, Isabela Gualanda, Caterina Sforza, Bianca Giovanna Sforza, Salaì, and even Leonardo himself.[32][33][34] Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud theorized that Leonardo imparted an approving smile from his mother, Caterina, onto the Mona Lisa and other works.[35][36]

Description

Detail of the background (right side)

The Mona Lisa bears a strong resemblance to many Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary, who was at that time seen as an ideal for womanhood.[37] The woman sits markedly upright in a «pozzetto» armchair with her arms folded, a sign of her reserved posture. Her gaze is fixed on the observer. The woman appears alive to an unusual extent, which Leonardo achieved by his method of not drawing outlines (sfumato). The soft blending creates an ambiguous mood «mainly in two features: the corners of the mouth, and the corners of the eyes».[38]

The depiction of the sitter in three-quarter profile is similar to late 15th-century works by Lorenzo di Credi and Agnolo di Domenico del Mazziere.[37] Zöllner notes that the sitter’s general position can be traced back to Flemish models and that «in particular the vertical slices of columns at both sides of the panel had precedents in Flemish portraiture.»[39] Woods-Marsden cites Hans Memling’s portrait of Benedetto Portinari (1487) or Italian imitations such as Sebastiano Mainardi’s pendant portraits for the use of a loggia, which has the effect of mediating between the sitter and the distant landscape, a feature missing from Leonardo’s earlier portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci.[40]

Detail of Lisa’s hands, her right hand resting on her left. Leonardo chose this gesture rather than a wedding ring to depict Lisa as a virtuous woman and faithful wife.[41]

The painting was one of the first portraits to depict the sitter in front of an imaginary landscape, and Leonardo was one of the first painters to use aerial perspective.[42] The enigmatic woman is portrayed seated in what appears to be an open loggia with dark pillar bases on either side. Behind her, a vast landscape recedes to icy mountains. Winding paths and a distant bridge give only the slightest indications of human presence. Leonardo has chosen to place the horizon line not at the neck, as he did with Ginevra de’ Benci, but on a level with the eyes, thus linking the figure with the landscape and emphasizing the mysterious nature of the painting.[40]

Mona Lisa has no clearly visible eyebrows or eyelashes, although Vasari describes the eyebrows in detail.[43][a] In 2007, French engineer Pascal Cotte announced that his ultra-high resolution scans of the painting provide evidence that Mona Lisa was originally painted with eyelashes and eyebrows, but that these had gradually disappeared over time, perhaps as a result of overcleaning.[46] Cotte discovered the painting had been reworked several times, with changes made to the size of the Mona Lisa’s face and the direction of her gaze. He also found that in one layer the subject was depicted wearing numerous hairpins and a headdress adorned with pearls which was later scrubbed out and overpainted.[47]

There has been much speculation regarding the painting’s model and landscape. For example, Leonardo probably painted his model faithfully since her beauty is not seen as being among the best, «even when measured by late quattrocento (15th century) or even twenty-first century standards.»[48] Some art historians in Eastern art, such as Yukio Yashiro, argue that the landscape in the background of the picture was influenced by Chinese paintings,[49] but this thesis has been contested for lack of clear evidence.[49]

Research in 2003 by Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University said that Mona Lisa’s smile disappears when observed with direct vision, known as foveal. Because of the way the human eye processes visual information, it is less suited to pick up shadows directly; however, peripheral vision can pick up shadows well.[50]

Research in 2008 by a geomorphology professor at Urbino University and an artist-photographer revealed likenesses of Mona Lisa‘s landscapes to some views in the Montefeltro region in the Italian provinces of Pesaro and Urbino, and Rimini.[51][52]

History

Creation and date

Of Leonardo da Vinci’s works, the Mona Lisa is the only portrait whose authenticity has never been seriously questioned,[53] and one of four works – the others being Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, Adoration of the Magi and The Last Supper – whose attribution has avoided controversy.[54] He had begun working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model of the Mona Lisa, by October 1503.[25][26] It is believed by some that the Mona Lisa was begun in 1503 or 1504 in Florence.[55] Although the Louvre states that it was «doubtless painted between 1503 and 1506»,[8] art historian Martin Kemp says that there are some difficulties in confirming the dates with certainty.[22] Alessandro Vezzosi believes that the painting is characteristic of Leonardo’s style in the final years of his life, post-1513.[56] Other academics argue that, given the historical documentation, Leonardo would have painted the work from 1513.[57] According to Vasari, «after he had lingered over it four years, [he] left it unfinished».[17] In 1516, Leonardo was invited by King Francis I to work at the Clos Lucé near the Château d’Amboise; it is believed that he took the Mona Lisa with him and continued to work on it after he moved to France.[32] Art historian Carmen C. Bambach has concluded that Leonardo probably continued refining the work until 1516 or 1517.[58] Leonardo’s right hand was paralytic circa 1517,[59] which may indicate why he left the Mona Lisa unfinished.[60][61][62][b]

Raphael’s drawing (c. 1505), after Leonardo; today in the Louvre along with the Mona Lisa[64]

Circa 1505,[64] Raphael executed a pen-and-ink sketch, in which the columns flanking the subject are more apparent. Experts universally agree that it is based on Leonardo’s portrait.[65][66][67] Other later copies of the Mona Lisa, such as those in the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design and The Walters Art Museum, also display large flanking columns. As a result, it was thought that the Mona Lisa had been trimmed.[68][69][70][71] However, by 1993, Frank Zöllner observed that the painting surface had never been trimmed;[72] this was confirmed through a series of tests in 2004.[73] In view of this, Vincent Delieuvin, curator of 16th-century Italian painting at the Louvre, states that the sketch and these other copies must have been inspired by another version,[74] while Zöllner states that the sketch may be after another Leonardo portrait of the same subject.[72]

The record of an October 1517 visit by Louis d’Aragon states that the Mona Lisa was executed for the deceased Giuliano de’ Medici, Leonardo’s steward at Belvedere, Vienna, between 1513 and 1516[75][76][c]—but this was likely an error.[77][d] According to Vasari, the painting was created for the model’s husband, Francesco del Giocondo.[78] A number of experts have argued that Leonardo made two versions (because of the uncertainty concerning its dating and commissioner, as well as its fate following Leonardo’s death in 1519, and the difference of details in Raphael’s sketch—which may be explained by the possibility that he made the sketch from memory).[64][67][66][79] The hypothetical first portrait, displaying prominent columns, would have been commissioned by Giocondo circa 1503, and left unfinished in Leonardo’s pupil and assistant Salaì’s possession until his death in 1524. The second, commissioned by Giuliano de’ Medici circa 1513, would have been sold by Salaì to Francis I in 1518[e] and is the one in the Louvre today.[67][66][79][80] Others believe that there was only one true Mona Lisa, but are divided as to the two aforementioned fates.[22][81][82] At some point in the 16th century, a varnish was applied to the painting.[3] It was kept at the Palace of Fontainebleau until Louis XIV moved it to the Palace of Versailles, where it remained until the French Revolution.[83] In 1797, it went on permanent display at the Louvre.[11]

Refuge, theft, and vandalism

Louis Béroud’s 1911 painting depicting Mona Lisa displayed in the Louvre before the theft, which Béroud discovered and reported to the guards

After the French Revolution, the painting was moved to the Louvre, but spent a brief period in the bedroom of Napoleon (d. 1821) in the Tuileries Palace.[83] The Mona Lisa was not widely known outside the art world, but in the 1860s, a portion of the French intelligentsia began to hail it as a masterwork of Renaissance painting.[84]

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), the painting was moved from the Louvre to the Brest Arsenal.[85]

In 1911, the painting was still not popular among the lay-public.[86] On 21 August 1911, the painting was stolen from the Louvre.[87] The painting was first missed the next day by painter Louis Béroud. After some confusion as to whether the painting was being photographed somewhere, the Louvre was closed for a week for investigation. French poet Guillaume Apollinaire came under suspicion and was arrested and imprisoned. Apollinaire implicated his friend Pablo Picasso, who was brought in for questioning. Both were later exonerated.[88][89] The real culprit was Louvre employee Vincenzo Peruggia, who had helped construct the painting’s glass case.[90] He carried out the theft by entering the building during regular hours, hiding in a broom closet, and walking out with the painting hidden under his coat after the museum had closed.[24]

Vacant wall in the Louvre’s Salon Carré after the painting was stolen in 1911

«La Joconde est Retrouvée» («Mona Lisa is Found»), Le Petit Parisien, 13 December 1913

The Mona Lisa in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence, 1913. Museum director Giovanni Poggi (right) inspects the painting.

Excelsior, «La Joconde est Revenue» («The Mona Lisa has returned»), 1 January 1914