|

Saint Paul the Apostle |

|

|---|---|

The Apostle Paul, c. 1657, Rembrandt |

|

| Apostle to the Gentiles, Martyr | |

| Born | Saul of Tarsus c. 5 AD[1] Tarsus, Cilicia, Roman Empire (in 21st-century Turkey) |

| Died | c. 64/65 AD[2][3] Rome, Italia, Roman Empire[2][4] |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations that venerate saints |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, Rome, Italy |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Christian martyrdom, sword, book |

| Patronage | Missionaries, theologians, evangelists, and Gentile Christians

Theology career |

| Education | School of Gamaliel[6] |

| Occupation | Christian missionary |

| Notable work |

|

| Theological work | |

| Era | Apostolic Age |

| Language | Koine Greek |

| Tradition or movement | Pauline Christianity |

| Main interests | Torah, Christology, eschatology, soteriology, ecclesiology |

| Notable ideas | Pauline privilege, Law of Christ, Holy Spirit, unknown God, divinity of Jesus, thorn in the flesh, Pauline mysticism, biblical inspiration, supersessionism, non-circumcision, salvation |

Paul[a] (previously called Saul of Tarsus;[b] c. 5 – c. 64/65 AD), commonly known as Paul the Apostle[7] and Saint Paul,[8] was a Christian apostle who spread the teachings of Jesus in the first-century world.[9] Generally regarded as one of the most important figures of the Apostolic Age,[8][10] he founded several Christian communities in Asia Minor and Europe from the mid-40s to the mid-50s AD.[11]

According to the New Testament book Acts of the Apostles, Paul lived as a Pharisee.[12] He participated in the persecution of early disciples of Jesus, possibly Hellenised diaspora Jews converted to Christianity,[13] in the area of Jerusalem, prior to his conversion.[note 1] Some time after having approved of the execution of Stephen,[14] Paul was traveling on the road to Damascus so that he might find any Christians there and bring them «bound to Jerusalem» (ESV).[15] At midday, a light brighter than the sun shone around both him and those with him, causing all to fall to the ground, with the risen Christ verbally addressing Paul regarding his persecution.[16][17] Having been made blind,[18] along with being commanded to enter the city, his sight was restored three days later by Ananias of Damascus. After these events, Paul was baptized, beginning immediately to proclaim that Jesus of Nazareth was the Jewish messiah and the Son of God.[19] Approximately half of the content in the book of Acts details the life and works of Paul.

Fourteen of the 27 books in the New Testament have traditionally been attributed to Paul.[20] Seven of the Pauline epistles are undisputed by scholars as being authentic, with varying degrees of argument about the remainder. Pauline authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews is not asserted in the Epistle itself and was already doubted in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.[note 2] It was almost unquestioningly accepted from the 5th to the 16th centuries that Paul was the author of Hebrews,[22] but that view is now almost universally rejected by scholars.[22][23] The other six are believed by some scholars to have come from followers writing in his name, using material from Paul’s surviving letters and letters written by him that no longer survive.[9][8][note 3] Other scholars argue that the idea of a pseudonymous author for the disputed epistles raises many problems.[25]

Today, Paul’s epistles continue to be vital roots of the theology, worship and pastoral life in the Latin and Protestant traditions of the West, as well as the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox traditions of the East.[26] Paul’s influence on Christian thought and practice has been characterized as being as «profound as it is pervasive», among that of many other apostles and missionaries involved in the spread of the Christian faith.[9]

Names

Paul’s Jewish name was «Saul» (Hebrew: שָׁאוּל, Modern: Sha’ûl, Tiberian: Šā’ûl), perhaps after the biblical King Saul, the first king of Israel and like Paul a member of the Tribe of Benjamin; the Latin name Paul, meaning small, was not a result of his conversion as it is commonly believed but a second name for use in communicating with a Greco-Roman audience.[27][28]

According to the Acts of the Apostles, he was a Roman citizen.[29] As such, he bore the Latin name «Paul» – in Latin Paulus and in biblical Greek Παῦλος (Paulos).[30][31] It was typical for the Jews of that time to have two names: one Hebrew, the other Latin or Greek.[32][33][34]

Jesus called him «Saul, Saul»[35] in «the Hebrew tongue» in the Acts of the Apostles, when he had the vision which led to his conversion on the road to Damascus.[36] Later, in a vision to Ananias of Damascus, «the Lord» referred to him as «Saul, of Tarsus».[37] When Ananias came to restore his sight, he called him «Brother Saul».[38]

In Acts 13:9, Saul is called «Paul» for the first time on the island of Cyprus – much later than the time of his conversion.[39] The author of Luke–Acts indicates that the names were interchangeable: «Saul, who also is called Paul.» He refers to him as Paul through the remainder of Acts. This was apparently Paul’s preference since he is called Paul in all other Bible books where he is mentioned, including those that he authored. Adopting his Roman name was typical of Paul’s missionary style. His method was to put people at their ease and to approach them with his message in a language and style to which they could relate, as in 1 Corinthians 9:19–23.[40][41]

Available sources

The main source for information about Paul’s life is the material found in his epistles and in the Acts of the Apostles.[42] However, the epistles contain little information about Paul’s pre-conversion past. The Acts of the Apostles recounts more information but leaves several parts of Paul’s life out of its narrative, such as his probable but undocumented execution in Rome.[43] The Acts of the Apostles also contradict Paul’s epistles on multiple accounts, in particular concerning the frequency of Paul’s visits to the church in Jerusalem.[44][45]

Sources outside the New Testament that mention Paul include:

- Clement of Rome’s epistle to the Corinthians (late 1st/early 2nd century);

- Ignatius of Antioch’s epistles to the Romans and to the Ephesians[46] (early 2nd century);

- Polycarp’s epistle to the Philippians (early 2nd century);

- Eusebius’s Historia Ecclesiae (early 4th century);

- The apocryphal Acts narrating the life of Paul (Acts of Paul, Acts of Paul and Thecla, Acts of Peter and Paul), the apocryphal epistles attributed to him (the Latin Epistle to the Laodiceans, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians, and the Correspondence of Paul and Seneca) and some apocalyptic texts attributed to him (Apocalypse of Paul and Coptic Apocalypse of Paul). These writings are all late (they are usually dated from the 2nd to the 4th century).

Biography

Early life

Geography relevant to Paul’s life, stretching from Jerusalem to Rome

The two main sources of information that give access to the earliest segments of Paul’s career are the Acts of the Apostles and the autobiographical elements of Paul’s letters to the early Christian communities.[42] Paul was likely born between the years of 5 BC and 5 AD.[47] The Acts of the Apostles indicates that Paul was a Roman citizen by birth, but Helmut Koester takes issue with the evidence presented by the text.[48][49]

He was from a devout Jewish family[50] based in the city of Tarsus.[27] One of the larger centers of trade on the Mediterranean coast and renowned for its university, Tarsus had been among the most influential cities in Asia Minor since the time of Alexander the Great, who died in 323 BC.[50]

Paul referred to himself as being «of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee».[51][52] The Bible reveals very little about Paul’s family. Acts quotes Paul referring to his family by saying he was «a Pharisee, born of Pharisees».[53][54] Paul’s nephew, his sister’s son, is mentioned in Acts 23:16.[55] In Romans 16:7, he states that his relatives, Andronicus and Junia, were Christians before he was and were prominent among the Apostles.[56]

The family had a history of religious piety.[57][note 4] Apparently, the family lineage had been very attached to Pharisaic traditions and observances for generations.[58] Acts says that he was an artisan involved in the leather crafting or tent-making profession.[59][60] This was to become an initial connection with Priscilla and Aquila, with whom he would partner in tentmaking[61] and later become very important teammates as fellow missionaries.[62]

While he was still fairly young, he was sent to Jerusalem to receive his education at the school of Gamaliel,[63][52] one of the most noted teachers of Jewish law in history. Although modern scholarship agrees that Paul was educated under the supervision of Gamaliel in Jerusalem,[52] he was not preparing to become a scholar of Jewish law, and probably never had any contact with the Hillelite school.[52] Some of his family may have resided in Jerusalem since later the son of one of his sisters saved his life there.[64][27] Nothing more is known of his biography until he takes an active part in the martyrdom of Stephen,[65] a Hellenised diaspora Jew.[66]

Although it is known (from his biography and from Acts) that Paul could and did speak Aramaic (then known as «Hebrew»),[27] modern scholarship suggests that Koine Greek was his first language.[67] In his letters, Paul drew heavily on his knowledge of Stoic philosophy, using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of the Gospel and to explain his Christology.[68][69]

Persecutor of early Christians

Paul says that prior to his conversion,[70] he persecuted early Christians «beyond measure», more specifically Hellenised diaspora Jewish members who had returned to the area of Jerusalem.[71][note 1] According to James Dunn, the Jerusalem community consisted of «Hebrews», Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and «Hellenists», Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.[72] Paul’s initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking «Hellenists» due to their anti-Temple attitude.[73] Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the «Hebrews» and their continuing participation in the Temple cult.[73]

Conversion

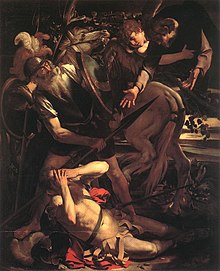

Paul’s conversion can be dated to 31–36 AD[74][75][76] by his reference to it in one of his letters. In Galatians 1:16, Paul writes that God «was pleased to reveal his son to me.»[77] In 1 Corinthians 15:8, as he lists the order in which Jesus appeared to his disciples after his resurrection, Paul writes, «last of all, as to one untimely born, He appeared to me also.»[78]

According to the account in the Acts of the Apostles, it took place on the road to Damascus, where he reported having experienced a vision of the ascended Jesus. The account says that «He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, ‘Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?’ He asked, ‘Who are you, Lord?’ The reply came, ‘I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting’.»[79]

According to the account in Acts 9:1–22, he was blinded for three days and had to be led into Damascus by the hand.[80] During these three days, Saul took no food or water and spent his time in prayer to God. When Ananias of Damascus arrived, he laid his hands on him and said: «Brother Saul, the Lord, [even] Jesus, that appeared unto thee in the way as thou camest, hath sent me, that thou mightest receive thy sight, and be filled with the Holy Ghost.»[81] His sight was restored, he got up and was baptized.[82] This story occurs only in Acts, not in the Pauline epistles.[83]

The author of the Acts of the Apostles may have learned of Paul’s conversion from the church in Jerusalem, or from the church in Antioch, or possibly from Paul himself.[84]

According to Timo Eskola, early Christian theology and discourse was influenced by the Jewish Merkabah tradition.[85] Similarly, Alan Segal and Daniel Boyarin regard Paul’s accounts of his conversion experience and his ascent to the heavens (in 2 Corinthians 12) as the earliest first-person accounts that are extant of a Merkabah mystic in Jewish or Christian literature. Conversely, Timothy Churchill has argued that Paul’s Damascus road encounter does not fit the pattern of Merkabah.[86]

Post-conversion

According to Acts:

And immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, «He is the Son of God.» And all who heard him were amazed and said, «Is not this the man who made havoc in Jerusalem of those who called upon this name? And has he not come here for this purpose, to bring them bound before the chief priests?» But Saul increased all the more in strength, and confounded the Jews who lived in Damascus by proving that Jesus was the Christ.

— Acts 9:20–22[87]

Early ministry

Bab Kisan, believed to be where Paul escaped from persecution in Damascus

After his conversion, Paul went to Damascus, where Acts 9 states he was healed of his blindness and baptized by Ananias of Damascus.[88] Paul says that it was in Damascus that he barely escaped death.[89] Paul also says that he then went first to Arabia, and then came back to Damascus.[90][91] Paul’s trip to Arabia is not mentioned anywhere else in the Bible, and some suppose he actually traveled to Mount Sinai for meditations in the desert.[92][93] He describes in Galatians how three years after his conversion he went to Jerusalem. There he met James and stayed with Simon Peter for 15 days.[94] Paul located Mount Sinai in Arabia in Galatians 4:24–25.[95]

Paul asserted that he received the Gospel not from man, but directly by «the revelation of Jesus Christ».[96] He claimed almost total independence from the Jerusalem community[97] (possibly in the Cenacle), but agreed with it on the nature and content of the gospel.[98] He appeared eager to bring material support to Jerusalem from the various growing Gentile churches that he started. In his writings, Paul used the persecutions he endured to avow proximity and union with Jesus and as a validation of his teaching.

Paul’s narrative in Galatians states that 14 years after his conversion he went again to Jerusalem.[99] It is not known what happened during this time, but both Acts and Galatians provide some details.[100] Though a view is held that Paul spent 14 years studying the scriptures and growing in the faith. At the end of this time, Barnabas went to find Paul and brought him to Antioch.[101][102] The Christian community at Antioch had been established by Hellenised diaspora Jews living in Jerusalem, who played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile «God-fearers.»[103] From Antioch the mission to the Gentiles started, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.[104]

When a famine occurred in Judea, around 45–46,[105] Paul and Barnabas journeyed to Jerusalem to deliver financial support from the Antioch community.[106] According to Acts, Antioch had become an alternative center for Christians following the dispersion of the believers after the death of Stephen. It was in Antioch that the followers of Jesus were first called «Christians».[107]

First missionary journey

The author of Acts arranges Paul’s travels into three separate journeys. The first journey,[108] for which Paul and Barnabas were commissioned by the Antioch community,[109] and led initially by Barnabas,[note 5] took Barnabas and Paul from Antioch to Cyprus then into southern Asia Minor, and finally returning to Antioch. In Cyprus, Paul rebukes and blinds Elymas the magician[110] who was criticizing their teachings.

They sailed to Perga in Pamphylia. John Mark left them and returned to Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas went on to Pisidian Antioch. On Sabbath they went to the synagogue. The leaders invited them to speak. Paul reviewed Israelite history from life in Egypt to King David. He introduced Jesus as a descendant of David brought to Israel by God. He said that his team came to town to bring the message of salvation. He recounted the story of Jesus’ death and resurrection. He quoted from the Septuagint[111] to assert that Jesus was the promised Christos who brought them forgiveness for their sins. Both the Jews and the «God-fearing» Gentiles invited them to talk more next Sabbath. At that time almost the whole city gathered. This upset some influential Jews who spoke against them. Paul used the occasion to announce a change in his mission which from then on would be to the Gentiles.[112]

Map of the missionary journeys of St. Paul

Antioch served as a major Christian home base for Paul’s early missionary activities,[4] and he remained there for «a long time with the disciples»[113] at the conclusion of his first journey. The exact duration of Paul’s stay in Antioch is unknown, with estimates ranging from nine months to as long as eight years.[114]

In Raymond Brown’s An Introduction to the New Testament (1997), a chronology of events in Paul’s life is presented, illustrated from later 20th-century writings of biblical scholars.[115] The first missionary journey of Paul is assigned a «traditional» (and majority) dating of 46–49 AD, compared to a «revisionist» (and minority) dating of after 37 AD.[116]

Council of Jerusalem

A vital meeting between Paul and the Jerusalem church took place in the year 49 AD by «traditional» (and majority) dating, compared to a «revisionist» (and minority) dating of 47/51 AD.[117] The meeting is described in Acts 15:2[118] and usually seen as the same event mentioned by Paul in Galatians 2:1.[119][43] The key question raised was whether Gentile converts needed to be circumcised.[120][121] At this meeting, Paul states in his letter to the Galatians, Peter, James, and John accepted Paul’s mission to the Gentiles.

The Jerusalem meetings are mentioned in Acts, and also in Paul’s letters.[122] For example, the Jerusalem visit for famine relief[123] apparently corresponds to the «first visit» (to Peter and James only).[124][122] F. F. Bruce suggested that the «fourteen years» could be from Paul’s conversion rather than from his first visit to Jerusalem.[125]

Incident at Antioch

Despite the agreement achieved at the Council of Jerusalem, Paul recounts how he later publicly confronted Peter in a dispute sometimes called the «Incident at Antioch», over Peter’s reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians in Antioch because they did not strictly adhere to Jewish customs.[120]

Writing later of the incident, Paul recounts, «I opposed [Peter] to his face, because he was clearly in the wrong», and says he told Peter, «You are a Jew, yet you live like a Gentile and not like a Jew. How is it, then, that you force Gentiles to follow Jewish customs?»[126] Paul also mentions that even Barnabas, his traveling companion and fellow apostle until that time, sided with Peter.[120]

The outcome of the incident remains uncertain. The Catholic Encyclopedia suggests that Paul won the argument, because «Paul’s account of the incident leaves no doubt that Peter saw the justice of the rebuke».[120] However, Paul himself never mentions a victory, and L. Michael White’s From Jesus to Christianity draws the opposite conclusion: «The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return».[127]

The primary source account of the Incident at Antioch is Paul’s letter to the Galatians.[126]

Second missionary journey

Paul left for his second missionary journey from Jerusalem, in late Autumn 49 AD,[130] after the meeting of the Council of Jerusalem where the circumcision question was debated. On their trip around the Mediterranean Sea, Paul and his companion Barnabas stopped in Antioch where they had a sharp argument about taking John Mark with them on their trips. The Acts of the Apostles said that John Mark had left them in a previous trip and gone home. Unable to resolve the dispute, Paul and Barnabas decided to separate; Barnabas took John Mark with him, while Silas joined Paul.

Paul and Silas initially visited Tarsus (Paul’s birthplace), Derbe and Lystra. In Lystra, they met Timothy, a disciple who was spoken well of, and decided to take him with them. Paul and his companions, Silas and Timothy, had plans to journey to the southwest portion of Asia Minor to preach the gospel but during the night, Paul had a vision of a man of Macedonia standing and begging him to go to Macedonia to help them. After seeing the vision, Paul and his companions left for Macedonia to preach the gospel to them.[131] The Church kept growing, adding believers, and strengthening in faith daily.[132]

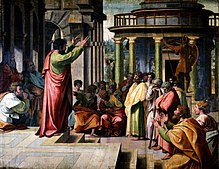

In Philippi, Paul cast a spirit of divination out of a servant girl, whose masters were then unhappy about the loss of income her soothsaying provided.[133] They seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities and Paul and Silas were put in jail. After a miraculous earthquake, the gates of the prison fell apart and Paul and Silas could have escaped but remained; this event led to the conversion of the jailor.[134] They continued traveling, going by Berea and then to Athens, where Paul preached to the Jews and God-fearing Greeks in the synagogue and to the Greek intellectuals in the Areopagus. Paul continued from Athens to Corinth.

Interval in Corinth

Around 50–52 AD, Paul spent 18 months in Corinth. The reference in Acts to Proconsul Gallio helps ascertain this date (cf. Gallio Inscription).[43] In Corinth, Paul met Priscilla and Aquila,[135] who became faithful believers and helped Paul through his other missionary journeys. The couple followed Paul and his companions to Ephesus, and stayed there to start one of the strongest and most faithful churches at that time.[136]

In 52, departing from Corinth, Paul stopped at the nearby village of Cenchreae to have his hair cut off, because of a vow he had earlier taken.[137] It is possible this was to be a final haircut prior to fulfilling his vow to become a Nazirite for a defined period of time.[138] With Priscilla and Aquila, the missionaries then sailed to Ephesus[139] and then Paul alone went on to Caesarea to greet the Church there. He then traveled north to Antioch, where he stayed for some time (Ancient Greek: ποιησας χρονον, «perhaps about a year»), before leaving again on a third missionary journey.[citation needed] Some New Testament texts[note 6] suggest that he also visited Jerusalem during this period for one of the Jewish feasts, possibly Pentecost.[140] Textual critic Henry Alford and others consider the reference to a Jerusalem visit to be genuine[141] and it accords with Acts 21:29,[142] according to which Paul and Trophimus the Ephesian had previously been seen in Jerusalem.

Third missionary journey

According to Acts, Paul began his third missionary journey by traveling all around the region of Galatia and Phrygia to strengthen, teach and rebuke the believers. Paul then traveled to Ephesus, an important center of early Christianity, and stayed there for almost three years, probably working there as a tentmaker,[144] as he had done when he stayed in Corinth. He is claimed to have performed numerous miracles, healing people and casting out demons, and he apparently organized missionary activity in other regions.[43] Paul left Ephesus after an attack from a local silversmith resulted in a pro-Artemis riot involving most of the city.[43] During his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote four letters to the church in Corinth.[145] The Jerusalem Bible suggests that the letter to the church in Philippi was also written from Ephesus.[146]

Paul went through Macedonia into Achaea[147] and stayed in Greece, probably Corinth, for three months[147] during 56–57 AD.[43] Commentators generally agree that Paul dictated his Epistle to the Romans during this period.[148] He then made ready to continue on to Syria, but he changed his plans and traveled back through Macedonia because of some Jews who had made a plot against him. In Romans 15:19,[149] Paul wrote that he visited Illyricum, but he may have meant what would now be called Illyria Graeca,[150] which was at that time a division of the Roman province of Macedonia.[151] On their way back to Jerusalem, Paul and his companions visited other cities such as Philippi, Troas, Miletus, Rhodes, and Tyre. Paul finished his trip with a stop in Caesarea, where he and his companions stayed with Philip the Evangelist before finally arriving at Jerusalem.[152]

Journey from Rome to Spain

Among the writings of the early Christians, Pope Clement I said that Paul was «Herald (of the Gospel of Christ) in the West», and that «he had gone to the extremity of the west».[153] John Chrysostom indicated that Paul preached in Spain: «For after he had been in Rome, he returned to Spain, but whether he came thence again into these parts, we know not».[154] Cyril of Jerusalem said that Paul, «fully preached the Gospel, and instructed even imperial Rome, and carried the earnestness of his preaching as far as Spain, undergoing conflicts innumerable, and performing Signs and wonders».[155] The Muratorian fragment mentions «the departure of Paul from the city [of Rome] [5a] (39) when he journeyed to Spain».[156]

Visits to Jerusalem in Acts and the epistles

This table is adapted from White, From Jesus to Christianity.[122] Note that the matching of Paul’s travels in the Acts and the travels in his Epistles is done for the reader’s convenience and is not approved of by all scholars.

| Acts | Epistles |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last visit to Jerusalem and arrest

Saint Paul arrested, early 1900s Bible illustration

In 57 AD, upon completion of his third missionary journey, Paul arrived in Jerusalem for his fifth and final visit with a collection of money for the local community. The Acts of the Apostles reports that he initially was warmly received. However, Acts goes on to recount how Paul was warned by James and the elders that he was gaining a reputation for being against the Law, saying «they have been told about you that you teach all the Jews living among the Gentiles to forsake Moses, and that you tell them not to circumcise their children or observe the customs.»[169] Paul underwent a purification ritual so that «all will know that there is nothing in what they have been told about you, but that you yourself observe and guard the law.»[170]

When the seven days of the purification ritual were almost completed, some «Jews from Asia» (most likely from Roman Asia) accused Paul of defiling the temple by bringing gentiles into it. He was seized and dragged out of the temple by an angry mob. When the tribune heard of the uproar, he and some centurions and soldiers rushed to the area. Unable to determine his identity and the cause of the uproar, they placed him in chains.[171] He was about to be taken into the barracks when he asked to speak to the people. He was given permission by the Romans and proceeded to tell his story. After a while, the crowd responded. «Up to this point they listened to him, but then they shouted, ‘Away with such a fellow from the earth! For he should not be allowed to live.'»[172] The tribune ordered that Paul be brought into the barracks and questioned by flogging. Paul asserted his Roman citizenship, which would prevent his flogging. The tribune «wanted to find out what Paul was being accused of by the Jews, the next day he released him and ordered the chief priests and the entire council to meet».[173] Paul spoke before the council and caused a disagreement between the Pharisees and the Sadducees. When this threatened to turn violent, the tribune ordered his soldiers to take Paul by force and return him to the barracks.[174]

The next morning, forty Jews «bound themselves by an oath neither to eat nor drink until they had killed Paul»,[175] but the son of Paul’s sister heard of the plot and notified Paul, who notified the tribune that the conspiracists were going to ambush him. The tribune ordered two centurions to «Get ready to leave by nine o’clock tonight for Caesarea with two hundred soldiers, seventy horsemen, and two hundred spearmen. Also provide mounts for Paul to ride, and take him safely to Felix the governor.»[176]

Paul was taken to Caesarea, where the governor ordered that he be kept under guard in Herod’s headquarters. «Five days later the high priest Ananias came down with some elders and an attorney, a certain Tertullus, and they reported their case against Paul to the governor.»[177] Both Paul and the Jewish authorities gave a statement «But Felix, who was rather well informed about the Way, adjourned the hearing with the comment, «When Lysias the tribune comes down, I will decide your case.»[178]

Marcus Antonius Felix then ordered the centurion to keep Paul in custody, but to «let him have some liberty and not to prevent any of his friends from taking care of his needs.»[179] He was held there for two years by Felix, until a new governor, Porcius Festus, was appointed. The «chief priests and the leaders of the Jews» requested that Festus return Paul to Jerusalem. After Festus had stayed in Jerusalem «not more than eight or ten days, he went down to Caesarea; the next day he took his seat on the tribunal and ordered Paul to be brought.» When Festus suggested that he be sent back to Jerusalem for further trial, Paul exercised his right as a Roman citizen to «appeal unto Caesar».[43] Finally, Paul and his companions sailed for Rome where Paul was to stand trial for his alleged crimes.[180]

St. Paul’s Grotto in Rabat, Malta

Acts recounts that on the way to Rome for his appeal as a Roman citizen to Caesar, Paul was shipwrecked on «Melita» (Malta),[181] where the islanders showed him «unusual kindness» and where he was met by Publius.[182] From Malta, he travelled to Rome via Syracuse, Rhegium and Puteoli.[183]

Two years in Rome

Paul finally arrived in Rome around 60 AD, where he spent another two years under house arrest.[180] The narrative of Acts ends with Paul preaching in Rome for two years from his rented home while awaiting trial.[184]

Irenaeus wrote in the 2nd century that Peter and Paul had been the founders of the church in Rome and had appointed Linus as succeeding bishop.[185] However, Paul was not a bishop of Rome, nor did he bring Christianity to Rome since there were already Christians in Rome when he arrived there;[186] Paul also wrote his letter to the church at Rome before he had visited Rome.[187] Paul only played a supporting part in the life of the church in Rome.[188]

Death

The date of Paul’s death is believed to have occurred after the Great Fire of Rome in July 64 AD, but before the last year of Nero’s reign, in 68 AD.[2]

The Second Epistle to Timothy states that Paul was arrested in Troad[189] and brought back to Rome, where he was imprisoned and put on trial; the Epistle was traditionally ascribed to Paul, but today many scholars considered it to be pseudepigrapha, perhaps written by one of Paul’s disciples.[190] Pope Clement I writes in his Epistle to the Corinthians that after Paul «had borne his testimony before the rulers», he «departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance.»[191] Ignatius of Antioch writes in his Epistle to the Ephesians that Paul was martyred, without giving any further information.[192]

Eusebius states that Paul was killed during the Neronian Persecution[193] and, quoting from Dionysius of Corinth, argues that Peter and Paul were martyred «at the same time».[194] Tertullian writes that Paul was beheaded like John the Baptist,[195] a detail also contained in Lactantius,[196]Jerome,[197] John Chrysostom[198] and Sulpicius Severus.[199][full citation needed]

A legend later developed that his martyrdom occurred at the Aquae Salviae, on the Via Laurentina. According to this legend, after Paul was decapitated, his severed head rebounded three times, giving rise to a source of water each time that it touched the ground, which is how the place earned the name «San Paolo alle Tre Fontane» («St Paul at the Three Fountains»).[200][201] The apocryphal Acts of Paul also describe the martyrdom and the burial of Paul, but their narrative is highly fanciful and largely unhistorical.[202]

Remains

According to the Liber Pontificalis, Paul’s body was buried outside the walls of Rome, at the second mile on the Via Ostiensis, on the estate owned by a Christian woman named Lucina.[203] It was here, in the fourth century, that the Emperor Constantine the Great built a first church. Then, between the fourth and fifth centuries, it was considerably enlarged by the Emperors Valentinian I, Valentinian II, Theodosius I, and Arcadius. The present-day Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls was built there in the early 19th century.[200]

Caius in his Disputation Against Proclus (198 AD) mentions this of the places in which the remains of the apostles Peter and Paul were deposited: «I can point out the trophies of the apostles. For if you are willing to go to the Vatican or to the Ostian Way, you will find the trophies of those who founded this Church».[204]

Jerome in his De Viris Illustribus (392 AD) writing on Paul’s biography, mentions that «Paul was buried in the Ostian Way at Rome».[205]

In 2002, an 8-foot (2.4 m)-long marble sarcophagus, inscribed with the words «PAULO APOSTOLO MART» («Paul apostle martyr») was discovered during excavations around the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls on the Via Ostiensis. Vatican archaeologists declared this to be the tomb of Paul the Apostle in 2005.[206] In June 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced excavation results concerning the tomb. The sarcophagus was not opened but was examined by means of a probe, which revealed pieces of incense, purple and blue linen, and small bone fragments. The bone was radiocarbon-dated to the 1st or 2nd century. According to the Vatican, these findings support the conclusion that the tomb is Paul’s.[207][208]

Church tradition

Various Christian writers have suggested more details about Paul’s life.

1 Clement, a letter written by the Roman bishop Clement of Rome around the year 90, reports this about Paul:

By reason of jealousy and strife Paul by his example pointed out the prize of patient endurance. After that he had been seven times in bonds, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached in the East and in the West, he won the noble renown which was the reward of his faith, having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the farthest bounds of the West; and when he had borne his testimony before the rulers, so he departed from the world and went unto the holy place, having been found a notable pattern of patient endurance.

— Lightfoot 1890, p. 274, The First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians, 5:5–6

Commenting on this passage, Raymond Brown writes that while it «does not explicitly say» that Paul was martyred in Rome, «such a martyrdom is the most reasonable interpretation».[209] Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote in the 4th century, states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero.[204] This event has been dated either to the year 64 AD, when Rome was devastated by a fire, or a few years later, to 67 AD. According to one tradition, the church of San Paolo alle Tre Fontane marks the place of Paul’s execution. A Roman Catholic liturgical solemnity of Peter and Paul, celebrated on 29 June, commemorates his martyrdom, and reflects a tradition (preserved by Eusebius) that Peter and Paul were martyred at the same time.[204] The Roman liturgical calendar for the following day now remembers all Christians martyred in these early persecutions; formerly, 30 June was the feast day for St. Paul.[210] Persons or religious orders with a special affinity for St. Paul can still celebrate their patron on 30 June.

The apocryphal Acts of Paul and the apocryphal Acts of Peter suggest that Paul survived Rome and traveled further west. Some think that Paul could have revisited Greece and Asia Minor after his trip to Spain, and might then have been arrested in Troas, and taken to Rome and executed.[211][note 4] A tradition holds that Paul was interred with Saint Peter ad Catacumbas by the via Appia until moved to what is now the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome. Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History, writes that Pope Vitalian in 665 gave Paul’s relics (including a cross made from his prison chains) from the crypts of Lucina to King Oswy of Northumbria, northern Britain. The skull of Saint Paul is claimed to reside in the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran since at least the ninth century, alongside the skull of Saint Peter.[212]

The Feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul is celebrated on 25 January.[213]

Paul is remembered (with Peter) in the Church of England with a Festival on 29 June.[214] Paul is considered the patron saint of London.

Physical appearance

Facial composite of Saint Paul, created by experts of the Landeskriminalamt of North Rhine-Westphalia using historical sources

The New Testament offers little if any information about the physical appearance of Paul, but several descriptions can be found in apocryphal texts. In the Acts of Paul[215] he is described as «A man of small stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked».[216] In the Latin version of the Acts of Paul and Thecla it is added that he had a red, florid face.

In The History of the Contending of Saint Paul, his countenance is described as «ruddy with the ruddiness of the skin of the pomegranate».[217] The Acts of Saint Peter confirms that Paul had a bald and shining head, with red hair.[218]

As summarised by Barnes,[219] Chrysostom records that Paul’s stature was low, his body crooked and his head bald. Lucian, in his Philopatris, describes Paul as «corpore erat parvo, contracto, incurvo, tricubitali» («he was small, contracted, crooked, of three cubits, or four feet six»).[32]

Nicephorus claims that Paul was a little man, crooked, and almost bent like a bow, with a pale countenance, long and wrinkled, and a bald head. Pseudo-Chrysostom echoes Lucian’s height of Paul, referring to him as «the man of three cubits».[32]

Writings

Of the 27 books in the New Testament, 13 identify Paul as the author; seven of these are widely considered authentic and Paul’s own, while the authorship of the other six is disputed.[220][221][222] The undisputed letters are considered the most important sources since they contain what is widely agreed to be Paul’s own statements about his life and thoughts. Theologian Mark Powell writes that Paul directed these seven letters to specific occasions at particular churches. As an example, if the Corinthian church had not experienced problems concerning its celebration of the Lord’s Supper,[223] today it would not be known that Paul even believed in that observance or had any opinions about it one way or the other. Powell comments that there may be other matters in the early church that have since gone unnoticed simply because no crises arose that prompted Paul to comment on them.[224]

In Paul’s writings, he provides the first written account of what it is to be a Christian and thus a description of Christian spirituality. His letters have been characterized as being the most influential books of the New Testament after the Gospels of Matthew and John.[8][note 9]

Date

Paul’s authentic letters are roughly dated to the years surrounding the mid-1st century. Placing Paul in this time period is done on the basis of his reported conflicts with other early contemporary figures in the Jesus movement including James and Peter,[225] the references to Paul and his letters by Clement of Rome writing in the late 1st century,[226] his reported issues in Damascus from 2 Corinthians 11:32 which he says took place while King Aretas IV was in power,[227] a possible reference to Erastus of Corinth in Romans 16:23,[228] his reference to preaching in the province of Illyricum (which dissolved in 80 AD),[229] the lack of any references to the Gospels indicating a pre-war time period, the chronology in the Acts of the Apostles placing Paul in this time, and the dependence on Paul’s letters by other 1st-century pseudo-Pauline epistles.[230]

Seven of the 13 letters that bear Paul’s name – Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians and Philemon – are almost universally accepted as being entirely authentic (dictated by Paul himself).[8][220][221][222] They are considered the best source of information on Paul’s life and especially his thought.[8]

Four of the letters (Ephesians, 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus) are widely considered pseudepigraphical, while the authorship of the other two is subject to debate.[220] Colossians and 2 Thessalonians are possibly «Deutero-Pauline» meaning they may have been written by Paul’s followers after his death. Similarly, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus may be «Trito-Pauline» meaning they may have been written by members of the Pauline school a generation after his death. According to their theories, these disputed letters may have come from followers writing in Paul’s name, often using material from his surviving letters. These scribes also may have had access to letters written by Paul that no longer survive.[8]

The authenticity of Colossians has been questioned on the grounds that it contains an otherwise unparalleled description (among his writings) of Jesus as «the image of the invisible God», a Christology found elsewhere only in the Gospel of John.[231] However, the personal notes in the letter connect it to Philemon, unquestionably the work of Paul. Internal evidence shows close connection with Philippians.[32]

Ephesians is a letter that is very similar to Colossians, but is almost entirely lacking in personal reminiscences. Its style is unique. It lacks the emphasis on the cross to be found in other Pauline writings, reference to the Second Coming is missing, and Christian marriage is exalted in a way that contrasts with the reference in 1 Corinthians.[232] Finally, according to R. E. Brown, it exalts the Church in a way suggestive of the second generation of Christians, «built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets» now past.[233]

The defenders of its Pauline authorship argue that it was intended to be read by a number of different churches and that it marks the final stage of the development of Paul’s thinking. It has been said, too, that the moral portion of the Epistle, consisting of the last two chapters, has the closest affinity with similar portions of other Epistles, while the whole admirably fits in with the known details of Paul’s life, and throws considerable light upon them.[234]

Three main reasons have been advanced by those who question Paul’s authorship of 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus, also known as the Pastoral Epistles:

- They have found a difference in these letters’ vocabulary, style, and theology from Paul’s acknowledged writings. Defenders of the authenticity say that they were probably written in the name and with the authority of the Apostle by one of his companions, to whom he distinctly explained what had to be written, or to whom he gave a written summary of the points to be developed, and that when the letters were finished, Paul read them through, approved them, and signed them.[234]

- There is a difficulty in fitting them into Paul’s biography as it is known.[235] They, like Colossians and Ephesians, were written from prison but suppose Paul’s release and travel thereafter.[32]

- 2 Thessalonians, like Colossians, is questioned on stylistic grounds with, among other peculiarities, a dependence on 1 Thessalonians—yet a distinctiveness in language from the Pauline corpus. This, again, is explainable by the possibility that Paul requested one of his companions to write the letter for him under his dictation.[32]

Acts

Although approximately half of the Acts of the Apostles deals with Paul’s life and works, Acts does not refer to Paul writing letters. Historians believe that the author of Acts did not have access to any of Paul’s letters. One piece of evidence suggesting this is that Acts never directly quotes from the Pauline epistles. Discrepancies between the Pauline epistles and Acts would further support the conclusion that the author of Acts did not have access to those epistles when composing Acts.[236][237]

British Jewish scholar Hyam Maccoby contended that Paul, as described in the Acts of the Apostles, is quite different from the view of Paul gleaned from his own writings. Some difficulties have been noted in the account of his life. Paul as described in the Acts of the Apostles is much more interested in factual history, less in theology; ideas such as justification by faith are absent as are references to the Spirit, according to Maccoby. He also pointed out that there are no references to John the Baptist in the Pauline Epistles, although Paul mentions him several times in the Acts of the Apostles.

Others have objected that the language of the speeches is too Lukan in style to reflect anyone else’s words. Moreover, George Shillington writes that the author of Acts most likely created the speeches accordingly and they bear his literary and theological marks.[238] Conversely, Howard Marshall writes that the speeches were not entirely the inventions of the author and while they may not be accurate word-for-word, the author nevertheless records the general idea of them.[239]

F. C. Baur (1792–1860), professor of theology at Tübingen in Germany, the first scholar to critique Acts and the Pauline Epistles, and founder of the Tübingen School of theology, argued that Paul, as the «Apostle to the Gentiles», was in violent opposition to the original 12 Apostles. Baur considers the Acts of the Apostles were late and unreliable. This debate has continued ever since, with Adolf Deissmann (1866–1937) and Richard Reitzenstein (1861–1931) emphasising Paul’s Greek inheritance and Albert Schweitzer stressing his dependence on Judaism.

Views

Self-view

In the opening verses of Romans 1,[240] Paul provides a litany of his own apostolic appointment to preach among the Gentiles[241] and his post-conversion convictions about the risen Christ.[8] Paul described himself as set apart for the gospel of God and called to be an apostle and a servant of Jesus Christ. Jesus had revealed himself to Paul, just as he had appeared to Peter, to James, and to the twelve disciples after his resurrection.[242] Paul experienced this as an unforeseen, sudden, startling change, due to all-powerful grace, not as the fruit of his reasoning or thoughts.[243]

Paul also describes himself as afflicted with «a thorn in the flesh»;[244] the nature of this «thorn» is unknown.[245]

There are debates as to whether Paul understood himself as commissioned to take the gospel to the gentiles at the moment of his conversion.[246] Before his conversion he believed his persecution of the church to be an indication of his zeal for his religion;[247] after his conversion he believed Jewish hostility toward the church was sinful opposition, that would incur God’s wrath.[248][249] Paul believed he was halted by Christ, when his fury was at its height.[250] It was «through zeal» that he persecuted the Church,[247] and he obtained mercy because he had «acted ignorantly in unbelief».[251][note 4]

Understanding of Jesus Christ

Paul’s writings emphasized the crucifixion, Christ’s resurrection and the Parousia or second coming of Christ.[74] Paul saw Jesus as Lord (kyrios), the true messiah and the Son of God, who was promised by God beforehand, through his prophets in the Holy Scriptures. While being a biological descendant from David («according to the flesh»),[252] he was declared to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead.

According to E. P. Sanders, Paul «preached the death, resurrection, and lordship of Jesus Christ, and he proclaimed that faith in Jesus guarantees a share in his life.»[8]

In Paul’s view, «Jesus’ death was not a defeat but was for the believers’ benefit,»[8] a sacrifice which substitutes for the lives of others, and frees them from the bondage of sin. Believers participate in Christ’s death and resurrection by their baptism. The resurrection of Jesus was of primary importance to Paul, bringing the promise of salvation to believers. Paul taught that, when Christ returned, «those who died in Christ would be raised when he returned», while those still alive would be «caught up in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air».[253][8]

Sanders concludes that Paul’s writings reveal what he calls the essence of the Christian message: «(1) God sent his Son; (2) the Son was crucified and resurrected for the benefit of humanity; (3) the Son would soon return; and (4) those who belonged to the Son would live with him forever. Paul’s gospel, like those of others, also included (5) the admonition to live by the highest moral standard: «May your spirit and soul and body be kept sound and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ».»[254][8]

In Paul’s writings, the public, corporate devotional patterns towards Jesus in the early Christian community are reflective of Paul’s perspective on the divine status of Jesus in what scholars have termed a «binitarian» pattern of devotion. For Paul, Jesus receives prayer,[255][256][257] the presence of Jesus is confessionally invoked by believers,[258][259][260] people are baptized in Jesus’ name,[261][262] Jesus is the reference in Christian fellowship for a religious ritual meal (the Lord’s Supper;[263] in pagan cults, the reference for ritual meals is always to a deity), and Jesus is the source of continuing prophetic oracles to believers.[264][265]

Atonement

Paul taught that Christians are redeemed from sin by Jesus’ death and resurrection. His death was an expiation as well as a propitiation, and by Christ’s blood peace is made between God and man.[266] By grace, through faith,[267] a Christian shares in Jesus’ death and in his victory over death, gaining as a free gift a new, justified status of sonship.[268]

According to Krister Stendahl, the main concern of Paul’s writings on Jesus’ role, and salvation by faith, is not the individual conscience of human sinners, and their doubts about being chosen by God or not, but the problem of the inclusion of gentile (Greek) Torah observers into God’s covenant.[269][270][271][272][note 10] «Dying for our sins» refers to the problem of gentile Torah-observers, who, despite their faithfulness, cannot fully observe commandments, including circumcision, and are therefore ‘sinners’, excluded from God’s covenant.[274] Jesus’ death and resurrection solved this problem of the exclusion of the gentiles from God’s covenant, as indicated by Romans 3:21–26.[275]

Paul’s conversion fundamentally changed his basic beliefs regarding God’s covenant and the inclusion of Gentiles into this covenant. Paul believed Jesus’ death was a voluntary sacrifice, that reconciled sinners with God.[276] The law only reveals the extent of people’s enslavement to the power of sin—a power that must be broken by Christ.[277] Before his conversion Paul believed Gentiles were outside the covenant that God made with Israel; after his conversion, he believed Gentiles and Jews were united as the people of God in Christ.[278] Before his conversion he believed circumcision was the rite through which males became part of Israel, an exclusive community of God’s chosen people;[279] after his conversion he believed that neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything, but that the new creation is what counts in the sight of God,[280] and that this new creation is a work of Christ in the life of believers, making them part of the church, an inclusive community of Jews and Gentiles reconciled with God through faith.[281]

According to E. P. Sanders, who initiated the New Perspective on Paul with his 1977 publication Paul and Palestinian Judaism, Paul saw the faithful redeemed by participation in Jesus’ death and rising. Though «Jesus’ death substituted for that of others and thereby freed believers from sin and guilt», a metaphor derived from «ancient sacrificial theology,»[8][note 11] the essence of Paul’s writing is not in the «legal terms» regarding the expiation of sin, but the act of «participation in Christ through dying and rising with him.»[citation needed] According to Sanders, «those who are baptized into Christ are baptized into his death, and thus they escape the power of sin […] he died so that the believers may die with him and consequently live with him.»[8] By this participation in Christ’s death and rising, «one receives forgiveness for past offences, is liberated from the powers of sin, and receives the Spirit.»

Relationship with Judaism

Some scholars see Paul as completely in line with 1st-century Judaism (a Pharisee and student of Gamaliel as presented by Acts),[284] others see him as opposed to 1st-century Judaism (see Marcionism), while the majority see him as somewhere in between these two extremes, opposed to insistence on keeping the «Ritual Laws» (for example the circumcision controversy in early Christianity) as necessary for entrance into God’s New Covenant,[285][286] but in full agreement on «Divine Law». These views of Paul are paralleled by the views of Biblical law in Christianity.

Paul redefined the people of Israel, those he calls the «true Israel» and the «true circumcision» as those who had faith in the heavenly Christ, thus excluding those he called «Israel after the flesh» from his new covenant.[287][288] He also held the view that the Torah given to Moses was valid «until Christ came,» so that even Jews are no longer «under the Torah,» nor obligated to follow the commandments or mitzvot as given to Moses.[289]

Tabor 2013

Paul is critical both theologically and empirically of claims of moral or lineal superiority[290] of Jews while conversely strongly sustaining the notion of a special place for the Children of Israel.[291] Paul’s theology of the gospel accelerated the separation of the messianic sect of Christians from Judaism, a development contrary to Paul’s own intent. He wrote that faith in Christ was alone decisive in salvation for Jews and Gentiles alike, making the schism between the followers of Christ and mainstream Jews inevitable and permanent. He argued that Gentile converts did not need to become Jews, get circumcised, follow Jewish dietary restrictions, or otherwise observe Mosaic laws to be saved.[43]

According to Paula Fredriksen, Paul’s opposition to male circumcision for Gentiles is in line with Old Testament predictions that «in the last days the gentile nations would come to the God of Israel, as gentiles (e.g., Zechariah 8:20–23),[292] not as proselytes to Israel.»[293] For Paul, Gentile male circumcision was therefore an affront to God’s intentions.[293] According to Hurtado, «Paul saw himself as what Munck called a salvation-historical figure in his own right,» who was «personally and singularly deputized by God to bring about the predicted ingathering (the «fullness») of the nations.»[294][293]

According to Sanders, Paul insists that salvation is received by the grace of God; according to Sanders, this insistence is in line with Judaism of c. 200 BC until 200 AD, which saw God’s covenant with Israel as an act of grace of God. Observance of the Law is needed to maintain the covenant, but the covenant is not earned by observing the Law, but by the grace of God.[295]

Sanders’ publications[285][296] have since been taken up by Professor James Dunn who coined the phrase «The New Perspective on Paul».[297] N.T. Wright,[298] the Anglican Bishop of Durham, notes a difference in emphasis between Galatians and Romans, the latter being much more positive about the continuing covenant between God and his ancient people than the former. Wright also contends that performing Christian works is not insignificant but rather proof of having attained the redemption of Jesus Christ by grace (free gift received by faith).[299] He concludes that Paul distinguishes between performing Christian works which are signs of ethnic identity and others which are a sign of obedience to Christ.[298]

World to come

According to Bart Ehrman, Paul believed that Jesus would return within his lifetime.[300] Paul expected that Christians who had died in the meantime would be resurrected to share in God’s kingdom, and he believed that the saved would be transformed, assuming heavenly, imperishable bodies.[301]

Paul’s teaching about the end of the world is expressed most clearly in his first and second letters to the Christian community of Thessalonica. He assures them that the dead will rise first and be followed by those left alive.[302] This suggests an imminent end but he is unspecific about times and seasons and encourages his hearers to expect a delay.[303] The form of the end will be a battle between Jesus and the man of lawlessness[304] whose conclusion is the triumph of Christ.

Before his conversion he believed God’s messiah would put an end to the old age of evil, and initiate a new age of righteousness; after his conversion, he believed this would happen in stages that had begun with the resurrection of Jesus, but the old age would continue until Jesus returns.[305][249]

Role of women

The second chapter of the first letter to Timothy—one of the six disputed letters—is used by many churches to deny women a vote in church affairs, reject women from serving as teachers of adult Bible classes, prevent them from serving as missionaries, and generally disenfranchise women from the duties and privileges of church leadership.[306]

9In like manner also, that women adorn themselves in modest apparel, with shamefacedness and sobriety; not with broided hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array;

10But (which becometh women professing godliness) with good works.

11Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection.

12But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.

13For Adam was first formed, then Eve.

14And Adam was not deceived, but the woman being deceived was in the transgression.

15Notwithstanding she shall be saved in childbearing, if they continue in faith and charity and holiness with sobriety.— 1 Timothy 2:9–15[307]

The King James Bible (Authorised Version) translation of this passage taken literally says that women in the churches are to have no leadership roles vis-à-vis men.[308]

Fuller Seminary theologian J. R. Daniel Kirk[309] finds evidence in Paul’s letters of a much more inclusive view of women. He writes that Romans 16 is a tremendously important witness to the important role of women in the early church. Paul praises Phoebe for her work as a deaconess and Junia who is described by Paul in Scripture as being respected among the Apostles.[56] It is Kirk’s observation that recent studies have led many scholars to conclude that the passage in 1 Corinthians 14 ordering women to «be silent» during worship[310] was a later addition, apparently by a different author, and not part of Paul’s original letter to the Corinthians.

Other scholars, such as Giancarlo Biguzzi, believe that Paul’s restriction on women speaking in 1 Corinthians 14 is genuine to Paul but applies to a particular case where there were local problems of women, who were not allowed in that culture to become educated, asking questions or chatting during worship services. He does not believe it to be a general prohibition on any woman speaking in worship settings since in 1 Corinthians Paul affirms the right (responsibility) of women to prophesy.[311][312]

Biblical prophecy is more than «fore-telling»: two-thirds of its inscripturated form involves «forth-telling», that is, setting the truth, justice, mercy, and righteousness of God against the backdrop of every form of denial of the same. Thus, to speak prophetically was to speak boldly against every form of moral, ethical, political, economic, and religious disenfranchisement observed in a culture that was intent on building its own pyramid of values vis-a-vis God’s established system of truth and ethics.

— Baker’s Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology[313]

There were women prophets in the highly patriarchal times throughout the Old Testament.[313] The most common term for prophet in the Old Testament is nabi in the masculine form, and nebiah in the Hebrew feminine form, is used six times of women who performed the same task of receiving and proclaiming the message given by God. These women include Miriam, Aaron and Moses’ sister,[314] Deborah,[315] the prophet Isaiah’s wife,[316] and Huldah, the one who interpreted the Book of the Law discovered in the temple during the days of Josiah.[317] There were false prophetesses just as there were false prophets. The prophetess Noadiah was among those who tried to intimidate Nehemiah.[318] Apparently they held equal rank in prophesying right along with Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Elisha, Aaron, and Samuel.[313]

Kirk’s third example of a more inclusive view is Galatians 3:28:

There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

— Galatians 3:28[319]

In pronouncing an end within the church to the divisions which are common in the world around it, he concludes by highlighting the fact that «there were New Testament women who taught and had authority in the early churches, that this teaching and authority was sanctioned by Paul, and that Paul himself offers a theological paradigm within which overcoming the subjugation of women is an anticipated outcome».[320]

Classicist Evelyn Stagg and theologian Frank Stagg believe that Paul was attempting to «Christianize» the societal household or domestic codes that significantly oppressed women and empowered men as the head of the household. The Staggs present a serious study of what has been termed the New Testament domestic code, also known as the Haustafel.[321] The two main passages that explain these «household duties» are Paul’s letters to the Ephesians[322] and to the Colossians.[323] An underlying Household Code is also reflected in four additional Pauline letters and 1 Peter: 1 Timothy 2:1ff, 8ff; 3:1ff, 8ff; 5:17ff; 6:1f; Titus 2:1–10[324] and 1 Peter.[325] Biblical scholars have typically treated the Haustafel in Ephesians as a resource in the debate over the role of women in ministry and in the home.[326]

Margaret MacDonald argues that the Haustafel, particularly as it appears in Ephesians, was aimed at «reducing the tension between community members and outsiders».[327]

E. P. Sanders has labeled Paul’s remark in 1 Corinthians[328] about women not making any sound during worship as «Paul’s intemperate outburst that women should be silent in the churches».[285][296] Women, in fact, played a very significant part in Paul’s missionary endeavors:

- He became a partner in ministry with the couple Priscilla and Aquila who are specifically named seven times in the New Testament—always by their couple name and never individually. Of the seven times they are named in the New Testament, Priscilla’s name appears first in five of those instances, suggesting to some scholars that she was the head of the family unit.[329] They lived, worked, and traveled with the Apostle Paul, becoming his honored, much-loved friends and coworkers in Jesus.[330] In Romans 16:3–4,[331] thought to have been written in 56 or 57, Paul sends his greetings to Priscilla and Aquila and proclaims that both of them «risked their necks» to save Paul’s life.

- Chloe was an important member of the church in Corinth.[332]

- Phoebe was a «deacon» and a «benefactor» of Paul and others[333]

- Romans 16[334] names eight other women active in the Christian movement, including Junia («prominent among the apostles»), Mary («who has worked very hard among you»), and Julia

- Women were frequently among the major supporters of the new Christian movement[8]

Views on homosexuality

Most Christian traditions[335][336][337] say Paul clearly portrays homosexuality as sinful in two specific locations: Romans 1:26–27,[338] and 1 Corinthians 6:9-10.[339] Another passage, 1 Timothy 1:8–11, addresses the topic more obliquely.[340] Since the 19th century, however, most scholars have concluded that 1 Timothy (along with 2 Timothy and Titus) is not original to Paul, but rather an unknown Christian writing in Paul’s name some time in the late-1st to mid-2nd century.[341][342]

Influence

Paul’s influence on Christian thinking arguably has been more significant than any other New Testament author.[8] Paul declared that «Christ is the end of the law»,[343] exalted the Christian church as the body of Christ, and depicted the world outside the Church as under judgment.[43] Paul’s writings include the earliest reference to the «Lord’s Supper»,[344] a rite traditionally identified as the Christian communion or Eucharist. In the East, church fathers attributed the element of election in Romans 9[345] to divine foreknowledge.[43] The themes of predestination found in Western Christianity do not appear in Eastern theology.

Pauline Christianity

Paul had a strong influence on early Christianity. Hurtado notes that Paul regarded his own Christological views and those of his predecessors and that of the Jerusalem Church as essentially similar. According to Hurtado, this «work[s] against the claims by some scholars that Pauline Christianity represents a sharp departure from the religiousness of Judean ‘Jesus movements’.»[346]

Marcion

Marcionism, regarded as heresy by contemporary mainstream Christianity, was an Early Christian dualist belief system that originated in the teachings of Marcion of Sinope at Rome around the year 144.[note 12] Marcion asserted that Paul was the only apostle who had rightly understood the new message of salvation as delivered by Christ.[347]

Marcion believed Jesus was the savior sent by God, and Paul the Apostle was his chief apostle, but he rejected the Hebrew Bible and the God of Israel. Marcionists believed that the wrathful Hebrew God was a separate and lower entity than the all-forgiving God of the New Testament.

Augustine

In his account of his conversion experience, Augustine of Hippo gave his life to Christ after reading Romans 13.[348][349] Augustine’s foundational work on the gospel as a gift (grace), on morality as life in the Spirit, on predestination, and on original sin all derives from Paul, especially Romans.[43]

Reformation

In his account of his conversion Martin Luther wrote about righteousness in Romans 1 praising Romans as the perfect gospel, in which the Reformation was birthed.[350] Martin Luther’s interpretation of Paul’s writings influenced Luther’s doctrine of sola fide.

John Calvin

John Calvin said the Book of Romans opens to anyone an understanding of the whole Scripture.[351]

Modern theology

Visit any church service, Roman Catholic, Protestant or Greek Orthodox, and it is the apostle Paul and his ideas that are central – in the hymns, the creeds, the sermons, the invocation and benediction, and of course, the rituals of baptism and the Holy Communion or Mass. Whether birth, baptism, confirmation, marriage or death, it is predominantly Paul who is evoked to express meaning and significance.

Professor James D. Tabor for the Huffington Post[352]

In his commentary The Epistle to the Romans (German: Der Römerbrief; particularly in the thoroughly re-written second edition of 1922), Karl Barth argued that the God who is revealed in the cross of Jesus challenges and overthrows any attempt to ally God with human cultures, achievements, or possessions.

In addition to the many questions about the true origins of some of Paul’s teachings posed by historical figures as noted above, some modern theologians also hold that the teachings of Paul differ markedly from those of Jesus as found in the Gospels.[353] Barrie Wilson states that Paul differs from Jesus in terms of the origin of his message, his teachings and his practices.[354] Some have even gone so far as to claim that, due to these apparent differences in teachings, that Paul was actually no less than the «second founder» of Christianity (Jesus being its first).[355][356]

As in the Eastern tradition in general, Western humanists interpret the reference to election in Romans 9 as reflecting divine foreknowledge.[43]

Views on Paul

Jewish views

A statue of Paul holding a scroll (symbolising the Scriptures) and the sword (symbolising his martyrdom)

Jewish interest in Paul is a recent phenomenon. Before the positive historical reevaluations of Jesus by some Jewish thinkers in the 18th and 19th centuries, he had hardly featured in the popular Jewish imagination and little had been written about him by the religious leaders and scholars. Arguably, he is absent from the Talmud and rabbinical literature, although he makes an appearance in some variants of the medieval polemic Toledot Yeshu (as a particularly effective spy for the rabbis).[357]

However, with Jesus no longer regarded as the paradigm of gentile Christianity, Paul’s position became more important in Jewish historical reconstructions of their religion’s relationship with Christianity. He has featured as the key to building barriers (e.g. Heinrich Graetz and Martin Buber) or bridges (e.g. Isaac Mayer Wise and Claude G. Montefiore) in interfaith relations,[358] as part of an intra-Jewish debate about what constitutes Jewish authenticity (e.g. Joseph Klausner and Hans Joachim Schoeps),[359] and on occasion as a dialogical partner (e.g. Richard L. Rubenstein and Daniel Boyarin).[360]

He features in an oratorio (by Felix Mendelssohn), a painting (by Ludwig Meidner) and a play (by Franz Werfel),[361] and there have been several novels about Paul (by Shalom Asch and Samuel Sandmel).[362] Jewish philosophers (including Baruch Spinoza, Leo Shestov, and Jacob Taubes)[363] and Jewish psychoanalysts (including Sigmund Freud and Hanns Sachs)[364] have engaged with the apostle as one of the most influential figures in Western thought. Scholarly surveys of Jewish interest in Paul include those by Hagner 1980, pp. 143–65, Meissner 1996, Langton 2010, Langton 2011a, pp. 55–72 and Langton 2011b, pp. 585–87.

Gnosticism

In the 2nd (and possibly late 1st) century, Gnosticism was a competing religious tradition to Christianity which shared some elements of theology.

Elaine Pagels concentrated on how the Gnostics interpreted Paul’s letters and how evidence from gnostic sources may challenge the assumption that Paul wrote his letters to combat «gnostic opponents» and to repudiate their statement that they possess secret wisdom.[365][page needed]

Muslim views

Muslims have long believed that Paul purposefully corrupted the original revealed teachings of Jesus,[366][367][368] through the introduction of such elements as paganism,[369] the making of Christianity into a theology of the cross,[370] and introducing original sin and the need for redemption.[371]

Sayf ibn Umar claimed that certain rabbis persuaded Paul to deliberately misguide early Christians by introducing what Ibn Hazm viewed as objectionable doctrines into Christianity.[372][373] Ibn Hazm repeated Sayf’s claims.[374] The Karaite scholar Jacob Qirqisani also believed that Paul created Christianity by introducing the doctrine of Trinity.[372] Paul has been criticized by some modern Muslim thinkers. Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas wrote that Paul misrepresented the message of Jesus,[368] and Rashid Rida accused Paul of introducing shirk (polytheism) into Christianity.[369] Mohammad Ali Jouhar quoted Adolf von Harnack’s critical writings of Paul.[370]

In Sunni Muslim polemics, Paul plays the same role (of deliberately corrupting the early teachings of Jesus) as a later Jew, Abdullah ibn Saba’, would play in seeking to destroy the message of Islam from within.[373][374][375] Among those who supported this view were scholars Ibn Taymiyyah (who believed while Paul ultimately succeeded, Ibn Saba failed) and Ibn Hazm (who claimed that the Jews even admitted to Paul’s sinister purpose).[372]

Other views

The critics of Paul the Apostle include US president Thomas Jefferson, a Deist, who wrote that Paul was the «first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus.»[376] Christian anarchists Leo Tolstoy and Ammon Hennacy took a similar view.[377][378]

In the Baha’i faith, scholars have various viewpoints on Paul. Discussions in Bahá’í scholarship have focused on whether Paul changed the original message of Christ or delivered the true Gospel, with proponents of both positions.[379]

See also

- Achaicus of Corinth

- Collegiate Parish Church of St Paul’s Shipwreck

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- New Perspective on Paul

- Old Testament: Christian views of the Law

- Paul, Apostle of Christ, 2018 film

- Pauline mysticism

- Pauline privilege

- Persecution of Christians in the New Testament

- Persecution of religion in ancient Rome

- Peter and Paul, 1981 miniseries

- Psychagogy

- St. Paul’s Cathedral

References

Notes

- ^ Latin: Paulus; Ancient Greek: Παῦλος, romanized: Paulos; Coptic: ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; Biblical Hebrew: פאולוס השליח

- ^ Biblical Hebrew: שאול התרסי, romanized: Sha’ūl ha-Tarsī; Arabic: بولس الطرسوسي; Ancient Greek: Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, romanized: Saũlos Tarseús; Turkish: Tarsuslu Pavlus; Latin: Paulus Tarsensis

- ^ a b Acts 8:1 «at Jerusalem»; Acts 9:13 «at Jerusalem»; Acts 9:21 «in Jerusalem»; Acts 26:10 «in Jerusalem». In Galatians 1:13, Paul states that he «persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it,» but does not specify where he persecuted the church. In Galatians 1:22 he states that more than three years after his conversion he was «still unknown by sight to the churches of Judea that are in Christ,» seemingly ruling out Jerusalem as the place he had persecuted Christians.[44]

- ^ Tertullian knew the Letter to the Hebrews as being «under the name of Barnabas» (De Pudicitia, chapter 20 where Tertullian quotes Hebrews 6:4–8); Origen, in his now lost Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, is reported by Eusebius[21] as having written «if any Church holds that this epistle is by Paul, let it be commended for this. For not without reason have the ancients handed it down as Paul’s. But who wrote the epistle, in truth, God knows. The statement of some who have gone before us is that Clement, bishop of the Romans, wrote the epistle, and of others, that Luke, the author of the Gospel and the Acts, wrote it

- ^ Paul’s undisputed epistles are 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Philippians, and Philemon. The six letters believed by some to have been written by Paul are Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus.[24]

- ^ a b c 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus may be «Trito-Pauline», meaning they may have been written by members of the Pauline school a generation after his death.

- ^ The only indication as to who is leading is in the order of names. At first, the two are referred to as Barnabas and Paul, in that order. Later in the same chapter, the team is referred to as Paul and his companions.

- ^ This clause is not found in some major sources: Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Alexandrinus, Codex Vaticanus or Codex Laudianus

- ^ Paul does not exactly say that this was his second visit. In Galatians, he lists three important meetings with Peter, and this was the second on his list. The third meeting took place in Antioch. He does not explicitly state that he did not visit Jerusalem in between this and his first visit.

- ^ Note that Paul only writes that he is on his way to Jerusalem, or just planning the visit. There might or might not have been additional visits before or after this visit, if he ever got to Jerusalem.

- ^ Sanders 2019: «Paul […] only occasionally had the opportunity to revisit his churches. He tried to keep up his converts’ spirit, answer their questions, and resolve their problems by letter and by sending one or more of his assistants (especially Timothy and Titus).

Paul’s letters reveal a remarkable human being: dedicated, compassionate, emotional, sometimes harsh and angry, clever and quick-witted, supple in argumentation, and above all possessing a soaring, passionate commitment to God, Jesus Christ, and his own mission. Fortunately, after his death one of his followers collected some of the letters, edited them very slightly, and published them. They constitute one of history’s most remarkable personal contributions to religious thought and practice.

- ^ Dunn 1982, p. n.49 quotes Stendahl 1976, p. 2 «… a doctrine of faith was hammered out by Paul for the very specific and limited purpose of defending the rights of Gentile converts to be full and genuine heirs to the promise of God to Israel»

Westerholm 2015, pp. 4–15: «For Paul, the question that ‘justification by faith’ was intended to answer was, ‘On what terms can Gentiles gain entrance to the people of God?» Bent on denying any suggestion that Gentiles must become Jews and keep the Jewish law, he answered, ‘By faith—and not by works of the (Jewish) law.'» Westerholm refers to: Stendahl 1963

Westerholm quotes Sanders: «Sanders noted that ‘the salvation of the Gentiles is essential to Paul’s preaching; and with it falls the law; for, as Paul says simply, Gentiles cannot live by the law’.[273] (496). On a similar note, Sanders suggested that the only Jewish ‘boasting’ to which Paul objected was that which exulted over the divine privileges granted to Israel and failed to acknowledge that God, in Christ, had opened the door of salvation to Gentiles.»