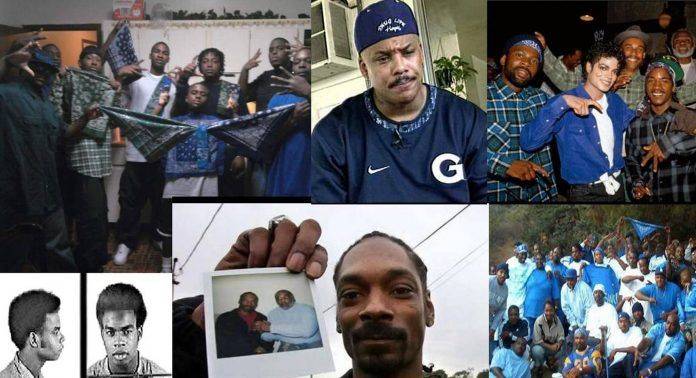

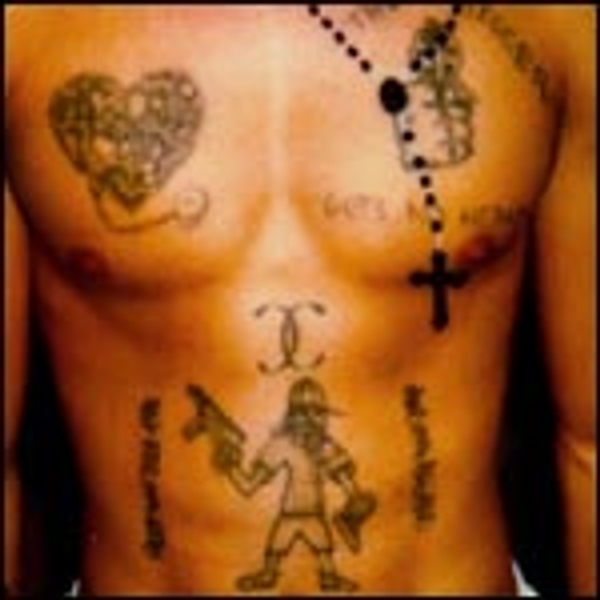

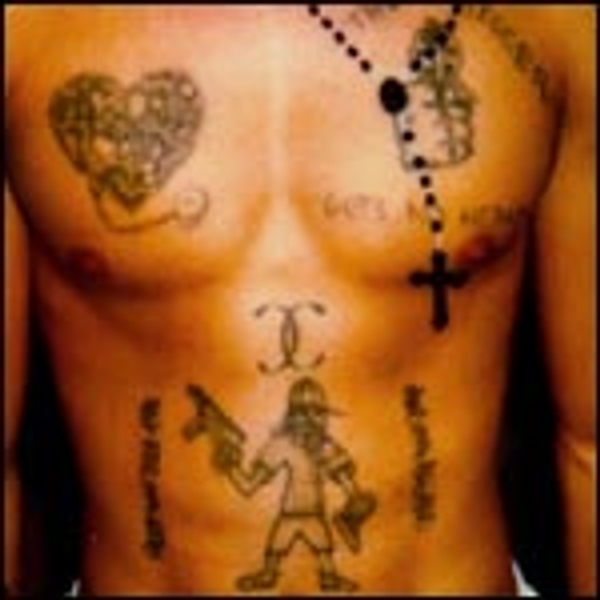

Crips tattoos |

|

| Founded | 1969; 54 years ago |

|---|---|

| Founders | Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams |

| Founding location | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Territory | 41 U.S. states[1] and Canada[2] |

| Ethnicity | Predominately African American[1] |

| Membership (est.) | 30,000–35,000[3] |

| Activities | Drug trafficking, murder, assault, auto theft, burglary, extortion, fraud, robbery[1] |

| Allies |

|

| Rivals |

|

| Notable members |

|

The Crips is an alliance of street gangs that is based in the coastal regions of Southern California. Founded in Los Angeles, California, in 1969, mainly by Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams, the Crips were initially a single alliance between two autonomous gangs; it is now a loosely-connected network of individual «sets», often engaged in open warfare with one another. Traditionally, since around 1973, its members have worn blue clothing.

The Crips are one of the largest and most violent associations of street gangs in the United States.[22] With an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 members in 2008,[3] the gangs’ members have been involved in murders, robberies and drug dealing, among other crimes. They have a long and bitter rivalry with the Bloods.

Some self-identified Crips have been convicted of federal racketeering.[23][24]

Etymology

Some sources suggest that the original name for the alliance, «Cribs», was narrowed down from a list of many options and chosen unanimously from three final choices, over the Black Overlords and the Assassins. Cribs was chosen to reflect the young age of the majority of the gang members. The name evolved into «Crips» when gang members began carrying around canes to display their «pimp» status. People in the neighborhood then began calling them cripples, or «Crips» for short.[25] In February 1972 the Los Angeles Times used the term.[22] Another source suggests «Crips» may have evolved from «Cripplers», a 1970s street gang in Watts, of which Washington was a member.[26] The name had no political, organizational, cryptic, or acronymic meaning, though some have suggested it stands for «Common Revolution In Progress», a backronym. According to the film Bastards of the Party, directed by a member of the Bloods, the name represented «Community Revolutionary Interparty Service» or «Community Reform Interparty Service».

History

Gang activity in South Central Los Angeles has its roots in a variety of factors dating to the 1950s, including: post-World War II economic decline leading to joblessness and poverty; racial segregation of young African American men, who were excluded from organizations such as the Boy Scouts, leading to the formation of black «street clubs»; and the waning of black nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and the Black Power Movement.[27][28][29][30]

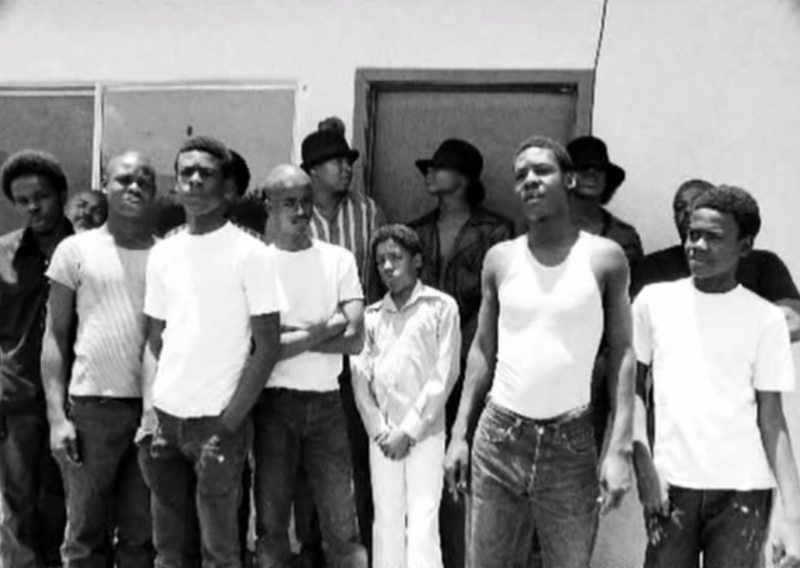

Stanley Tookie Williams met Raymond Lee Washington in 1969, and the two decided to unite their local gang members from the west and east sides of South Central Los Angeles in order to battle neighboring street gangs. Most of the members were 17 years old.[31] Williams however appears to discount the sometimes-cited founding date of 1969 in his memoir, Blue Rage, Black Redemption.[31]

In his memoir, Williams also refuted claims that the group was a spin-off of the Black Panther Party or formed for a community agenda, writing that it «depicted a fighting alliance against street gangs—nothing more, nothing less.»[31] Washington, who attended Fremont High School, was the leader of the East Side Crips, and Williams, who attended Washington High School, led the West Side Crips.

Williams recalled that a blue bandana was first worn by Crips founding member Curtis «Buddha» Morrow, as a part of his color-coordinated clothing of blue Levis, a blue shirt, and dark blue suspenders. A blue bandana was worn in tribute to Morrow after he was shot and killed on February 23, 1973. The color then became associated with Crips.[31]

By 1978, there were 45 Crip gangs, called sets, in Los Angeles. They were heavily involved in the production of PCP,[32] marijuana and amphetamines.[33][34] On March 11, 1979, Williams, a member of the Westside Crips, was arrested for four murders and on August 9, 1979, Washington was gunned down. Washington had been against Crip infighting and after his death several Crip sets started fighting against each other. The Crips’ leadership was dismantled, prompting a deadly gang war between the Rollin’ 60 Neighborhood Crips and Eight Tray Gangster Crips that led nearby Crip sets to choose sides and align themselves with either the Neighborhood Crips or the Gangster Crips, waging large-scale war in South Central and other cities. The East Coast Crips (from East Los Angeles) and the Hoover Crips directly severed their alliance after Washington’s death. By 1980, the Crips were in turmoil, warring with the Bloods and against each other. The gang’s growth and influence increased significantly in the early 1980s when crack cocaine hit the streets and Crip sets began distributing the drug. Large profits induced many Crips to establish new markets in other cities and states. As a result, Crips membership grew steadily and the street gang was one of the nation’s largest by the late 1980s.[35][36] In 1999, there were at least 600 Crip sets with more than 30,000 members transporting drugs in the United States.[22]

Membership

As of 2015, the Crips gang consists of between approximately 30,000 and 35,000 members and 800 sets, active in 221 cities and 41 U.S. states.[1] The states with the highest estimated number of Crip sets are California, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Members typically consist of young African American men, but can be white, Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander.[22] The gang also began to establish a presence in Canada in the early 1990s;[37] Crip sets are active in the Canadian cities of Montreal and Toronto.[38][39]

In 1992 the LAPD estimated 15,742 Crips in 108 sets; other source estimates were 30,000 to 35,000 in 600 sets in California.[40]

Crips have served in the United States armed forces and on military bases in the United States and abroad.[41]

Practices

Language

Some practices of Crip gang life include graffiti and substitutions and deletions of particular letters of the alphabet. The letter «b» in the word «blood» is «disrespected» among certain Crip sets and written with a cross inside it because of its association with the enemy. The letters «CK», which are interpreted to stand for «Crip killer», are avoided and replaced by «cc». For example, the words «kick back» are written «kicc bacc», and block is written as «blocc». Many other words and letters are also altered due to symbolic associations.[42] Crips traditionally refer to each other as «Cuz» or «Cuzz», which itself is sometimes used as a moniker for a Crip. «Crab» is the most disrespectful epithet to call a Crip, and can warrant fatal retaliation.[43] Crips in prison modules in the 1970s and 1980s sometimes spoke Swahili to maintain privacy from guards and rival gangs.[44]

Criminal rackets and street activities

As with most criminal street gangs, Crips have traditionally benefited monetarily from illicit activities such as illegal gambling, drug-dealing, pimping, larceny, and robbery.[1] Crips also profit from extorting local drug dealers who are not members of the gang. Along with profitable rackets such as these, they have also been known to participate in vandalism and property crime, often for gang-pride reasons or simply enjoyment. This can include public graffiti (tagging) and «joyriding» in stolen vehicles.

The gang’s current primary illicit source of income is presumably in street-level drug distribution, however many Crip members may also make notable amounts of illegal funds from the black market sale of illicit firearms. Historically, the gang’s size and power was largely augmented by the profits from the street sale of crack cocaine throughout the 1980s showing that PCP, amphetamines and other drugs were not as lucrative for them and thus did not have as direct of an effect on the group’s increase in influence. Therefore, the gang’s initial phase of growth and popularity can, in some way, be directly traced back to the explosion crack cocaine in the United States during the 1980s.[citation needed]

Crip-on-Crip rivalries

The Crips became popular throughout southern Los Angeles as more youth gangs joined; at one point they outnumbered non-Crip gangs by 3 to 1, sparking disputes with non-Crip gangs, including the L.A. Brims, Athens Park Boys, the Bishops, The Drill Company, and the Denver Lanes. By 1971 the gang’s notoriety had spread across Los Angeles.

By 1971, a gang on Piru Street in Compton, California, known as the Piru Street Boys, formed and associated itself with the Crips as a set. After two years of peace, a feud began between the Pirus and the other Crip sets. It later turned violent as gang warfare ensued between former allies. This battle continued and by 1973, the Pirus wanted to end the violence and called a meeting with other gangs targeted by the Crips. After a long discussion, the Pirus broke all connections to the Crips and started an organization that would later be called the Bloods,[45] a street gang infamous for its rivalry with the Crips.

Since then, other conflicts and feuds were started between many of the remaining Crip sets. It is a common misconception that Crip sets feud only with Bloods. In reality, they also fight each other—for example, the Rolling 60s Neighborhood Crips and 83 Gangster Crips have been rivals since 1979. In Watts, the Grape Street Crips and the PJ Watts Crips have feuded so much that the PJ Watts Crips even teamed up with a local Blood set, the Bounty Hunter Bloods, to fight the Grape Street Crips.[46] In the mid-1990s, the Hoover Crips rivalries and wars with other Crip sets caused them to become independent and drop the Crip name, calling themselves the Hoover Criminals.

Alliances and rivalries

Rivalry with the Bloods

The Bloods are the Crips’ main stereotypical rival. The Bloods initially formed to provide Piru Street Gang members protection from the Crips. The rivalry started in the 1960s when Washington and other Crip members attacked Sylvester Scott and Benson Owens, two students at Centennial High School. After the incident, Scott formed the Pirus, while Owens established the West Piru gang.[47] In late 1972, several gangs that felt victimized by the Crips due to their escalating attacks joined the Pirus to create a new federation of non-Crip gangs that later became known as Bloods. Between 1972 and 1979, the rivalry between the Crips and Bloods grew, accounting for a majority of the gang-related murders in southern Los Angeles. Members of the Bloods and Crips occasionally fight each other and, as of 2010, are responsible for a significant portion of gang-related murders in Los Angeles.[48] This rivalry is also believed to be behind the 2022 Sacramento shooting, where 6 people were killed.[49]

Alliance with the Folk Nation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as many Crip gang members were being sent to various prisons across the country, an alliance was formed between the Crips and the Folk Nation in Midwest and Southern U.S. prisons. This alliance was established to protect gang members incarcerated in state and federal prison. It is strongest within the prisons, and less effective outside. The alliance between the Crips and Folks is known as «8-ball». A broken 8-ball indicates a disagreement or «beef» between Folks and Crips.[35]

See also

- African-American organized crime

- Gangs in Los Angeles

- List of California street gangs

- Crip Walk

- Crips and Bloods: Made in America

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e «Criminal Street Gangs», United States Department of Justice (May 12, 2015)

- ^ Matt Kwong (January 19, 2015), «Canada’s gang hotspots — are you in one?», Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ a b «Appendix B. National-Level Street, Prison, and Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Profiles – Attorney General’s Report to Congress on the Growth of Violent Street Gangs in Suburban Areas (UNCLASSIFIED)». www.justice.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ «In our world, killing is easy’: Latin Kings part of a web of organized crime alliances, say former gangsters and law enforcement officials». MassLive. December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ «Major Prison Gangs(continued)». Gangs and Security Threat Group Awareness. Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/9400/gilbert_thesis.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ «Los Angeles-based Gangs — Bloods and Crips». Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on October 27, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Echo Day (December 12, 2019), «Here’s what we know about the Gangster Disciple governor who was sentenced to 10 years in prison», The Leader

- ^ «Juggalos: Emerging Gang Trends and Criminal Activity Intelligence Report» (PDF). Info.publicintelligence.net. February 15, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Michael Roberts (July 10, 2015), «Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Recruiting Military? Report Cites Colorado Murder», Westword

- ^ «Los Angeles Gangs and Hate Crimes», Police Law Enforcement Magazine, February 29, 2008

- ^ Montaldo, Charles (2014). «The Aryan Brotherhood: Profile of One of the Most Notorious Prison Gangs». About.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Rhian Daly (May 1, 2019), Rival gangs Crips And Bloods talk «historic» coming together following Nipsey Hussle’s murder», NME

- ^ Sam Quinones (October 18, 2007), «Gang rivalry grows into race war», Los Angeles Times

- ^ Brad Hamilton (October 28, 2007), «Gangs of New York», New York Post

- ^ «Gang Information», bethlehem-pa.gov (2019)

- ^ People v. Parsley, Court Listener (August 11, 2016)

- ^ Herbert C. Covey (2015), Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture

- ^ «Not on our turf: California gangs create havoc here»,[permanent dead link], Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 28, 1994.

- ^ «Bloods Gang Members Sentenced to Life in Prison for Racketeering Conspiracy Involving Murder and Other Crimes», United States Department of Justice (October 27, 2020)

- ^ Ben Ehrenreich (July 21, 1999), «Ganging up in Venice», LA Weekly

- ^ a b c d U.S. Department of Justice, Crips.

- ^ Failla, Zak (September 9, 2022). «Maryland Gang Member Who Goes By ‘Crazy’ Sentenced For Assaulting Fellow ‘Crip’ Behind Bars». Daily Voice. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Meghann, Cuniff (August 8, 2022). «‘Boss of Bosses’ Crips Gang Leader Sentenced to Decades in Federal Prison for Racketeering Murder Conspiracy». Law & Crime. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ «Los Angeles». Inside. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Dunn, William (2008). Boot: An LAPD Officer’s Rookie Year in South Central Los Angeles. iUniverse. p. 76. ISBN 9780595468782.

- ^ Stacy Peralta (Director), Stacy Peralta & Sam George (writers), Baron Davis et al. (producer), Steve Luczo, Quincy «QD3» Jones III (executive producer) (2009). Crips and Bloods: Made in America (TV-Documentary). PBS Independent Lens series. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ «Timeline: South Central Los Angeles». PBS (part of the «Crips and Bloods: Made in America» TV documentary). April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^

Sharkey, Betsy (February 6, 2009). «Review: ‘Crips and Bloods: Made in America’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009. - ^

Cle Sloan (Director), Antoine Fuqua and Cle Sloan (producer), Jack Gulick (executive producer) (2009). Keith Salmon (ed.). Bastards of the Party (TV-Documentary). HBO. Retrieved May 15, 2009. - ^ a b c d Williams, Stanley Tookie; Smiley, Tavis (2007). Blue Rage, Black Redemption. Simon & Schuster. pp. xvii–xix, 91–92, 136. ISBN 1-4165-4449-6.

- ^ Leonard, Barry (November 2009). National Drug Threat Assessment 2008. DIANE Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4379-1565-5.

- ^ Finley, Laura L. (October 1, 2018). Gangland: An Encyclopedia of Gang Life from Cradle to Grave [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4408-4474-4.

- ^ Vigil, James Diego (November 3, 2021). The Projects: Gang and Non-gang Families in East Los Angeles. University of Texas Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-292-79509-9.

- ^ a b Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ «The Crips: Prison Gang Profile».

- ^ =Alliances, Conflicts, and Contradictions in Montreal’s Street Gang Landscape, Karine Descormiers and Carlo Morselli, International Criminal Justice Review (October 17, 2020)

- ^ Toronto police, numerous other forces, dismantle ‘violent street gang’ known as Eglinton West Crips Jessica Patton, Global News (October 29, 2020)

- ^ Covey, Herbert. Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture: A Guide to an American Subculture. p. 9.

- ^ «Gangs Increasing in Military, FBI Says». Military.com. McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. June 30, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Capozzoli, Thomas and McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, p. 72. ISBN 1-57444-283-X.

- ^ «War and Peace in Watts» Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (July 14, 2005). LA Weekly. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Garrison, Jessica; Mejia, Brittany; Chabria, Anita (April 6, 2022). «At least five shooters involved in Sacramento massacre, gang ties likely, police say». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

General

- Leon Bing (1991). Do or Die: America’s Most Notorious Gangs Speak for Themselves. Sagebrush. ISBN 0-8335-8499-5

- Yusuf Jah, Sister Shah’keyah, Ice-T, UPRISING : Crips and Bloods Tell the Story of America’s Youth In The Crossfire, ISBN 0-684-80460-3

- Capozzoli, Thomas og McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, side. 72 ISBN 1-57444-283-X

- National Drug Intelligence Center (2002). Drugs and Crime: Gang Profile: Crips (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved June 21, 2009. Product no. 2002-M0465-001.

- Shakur, Sanyika (1993). Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member, Atlantic Monthly Pr, ISBN 0-87113-535-3

- Colton Simpson, Ann Pearlman, Ice-T (Foreword) (2005). Inside the Crips : Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang (HB) ISBN 0-312-32929-6

- Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- Stanley Tookie Williams (2005). Blue Rage, Black Redemption: A Memoir (PB) ISBN 0-9753584-0-5

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crips.

- PBS Independent Lens program on South Los Angeles gangs

- Snopes Urban Legend – The origin of the name Crips

Crips tattoos |

|

| Founded | 1969; 54 years ago |

|---|---|

| Founders | Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams |

| Founding location | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Territory | 41 U.S. states[1] and Canada[2] |

| Ethnicity | Predominately African American[1] |

| Membership (est.) | 30,000–35,000[3] |

| Activities | Drug trafficking, murder, assault, auto theft, burglary, extortion, fraud, robbery[1] |

| Allies |

|

| Rivals |

|

| Notable members |

|

The Crips is an alliance of street gangs that is based in the coastal regions of Southern California. Founded in Los Angeles, California, in 1969, mainly by Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams, the Crips were initially a single alliance between two autonomous gangs; it is now a loosely-connected network of individual «sets», often engaged in open warfare with one another. Traditionally, since around 1973, its members have worn blue clothing.

The Crips are one of the largest and most violent associations of street gangs in the United States.[22] With an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 members in 2008,[3] the gangs’ members have been involved in murders, robberies and drug dealing, among other crimes. They have a long and bitter rivalry with the Bloods.

Some self-identified Crips have been convicted of federal racketeering.[23][24]

Etymology

Some sources suggest that the original name for the alliance, «Cribs», was narrowed down from a list of many options and chosen unanimously from three final choices, over the Black Overlords and the Assassins. Cribs was chosen to reflect the young age of the majority of the gang members. The name evolved into «Crips» when gang members began carrying around canes to display their «pimp» status. People in the neighborhood then began calling them cripples, or «Crips» for short.[25] In February 1972 the Los Angeles Times used the term.[22] Another source suggests «Crips» may have evolved from «Cripplers», a 1970s street gang in Watts, of which Washington was a member.[26] The name had no political, organizational, cryptic, or acronymic meaning, though some have suggested it stands for «Common Revolution In Progress», a backronym. According to the film Bastards of the Party, directed by a member of the Bloods, the name represented «Community Revolutionary Interparty Service» or «Community Reform Interparty Service».

History

Gang activity in South Central Los Angeles has its roots in a variety of factors dating to the 1950s, including: post-World War II economic decline leading to joblessness and poverty; racial segregation of young African American men, who were excluded from organizations such as the Boy Scouts, leading to the formation of black «street clubs»; and the waning of black nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and the Black Power Movement.[27][28][29][30]

Stanley Tookie Williams met Raymond Lee Washington in 1969, and the two decided to unite their local gang members from the west and east sides of South Central Los Angeles in order to battle neighboring street gangs. Most of the members were 17 years old.[31] Williams however appears to discount the sometimes-cited founding date of 1969 in his memoir, Blue Rage, Black Redemption.[31]

In his memoir, Williams also refuted claims that the group was a spin-off of the Black Panther Party or formed for a community agenda, writing that it «depicted a fighting alliance against street gangs—nothing more, nothing less.»[31] Washington, who attended Fremont High School, was the leader of the East Side Crips, and Williams, who attended Washington High School, led the West Side Crips.

Williams recalled that a blue bandana was first worn by Crips founding member Curtis «Buddha» Morrow, as a part of his color-coordinated clothing of blue Levis, a blue shirt, and dark blue suspenders. A blue bandana was worn in tribute to Morrow after he was shot and killed on February 23, 1973. The color then became associated with Crips.[31]

By 1978, there were 45 Crip gangs, called sets, in Los Angeles. They were heavily involved in the production of PCP,[32] marijuana and amphetamines.[33][34] On March 11, 1979, Williams, a member of the Westside Crips, was arrested for four murders and on August 9, 1979, Washington was gunned down. Washington had been against Crip infighting and after his death several Crip sets started fighting against each other. The Crips’ leadership was dismantled, prompting a deadly gang war between the Rollin’ 60 Neighborhood Crips and Eight Tray Gangster Crips that led nearby Crip sets to choose sides and align themselves with either the Neighborhood Crips or the Gangster Crips, waging large-scale war in South Central and other cities. The East Coast Crips (from East Los Angeles) and the Hoover Crips directly severed their alliance after Washington’s death. By 1980, the Crips were in turmoil, warring with the Bloods and against each other. The gang’s growth and influence increased significantly in the early 1980s when crack cocaine hit the streets and Crip sets began distributing the drug. Large profits induced many Crips to establish new markets in other cities and states. As a result, Crips membership grew steadily and the street gang was one of the nation’s largest by the late 1980s.[35][36] In 1999, there were at least 600 Crip sets with more than 30,000 members transporting drugs in the United States.[22]

Membership

As of 2015, the Crips gang consists of between approximately 30,000 and 35,000 members and 800 sets, active in 221 cities and 41 U.S. states.[1] The states with the highest estimated number of Crip sets are California, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Members typically consist of young African American men, but can be white, Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander.[22] The gang also began to establish a presence in Canada in the early 1990s;[37] Crip sets are active in the Canadian cities of Montreal and Toronto.[38][39]

In 1992 the LAPD estimated 15,742 Crips in 108 sets; other source estimates were 30,000 to 35,000 in 600 sets in California.[40]

Crips have served in the United States armed forces and on military bases in the United States and abroad.[41]

Practices

Language

Some practices of Crip gang life include graffiti and substitutions and deletions of particular letters of the alphabet. The letter «b» in the word «blood» is «disrespected» among certain Crip sets and written with a cross inside it because of its association with the enemy. The letters «CK», which are interpreted to stand for «Crip killer», are avoided and replaced by «cc». For example, the words «kick back» are written «kicc bacc», and block is written as «blocc». Many other words and letters are also altered due to symbolic associations.[42] Crips traditionally refer to each other as «Cuz» or «Cuzz», which itself is sometimes used as a moniker for a Crip. «Crab» is the most disrespectful epithet to call a Crip, and can warrant fatal retaliation.[43] Crips in prison modules in the 1970s and 1980s sometimes spoke Swahili to maintain privacy from guards and rival gangs.[44]

Criminal rackets and street activities

As with most criminal street gangs, Crips have traditionally benefited monetarily from illicit activities such as illegal gambling, drug-dealing, pimping, larceny, and robbery.[1] Crips also profit from extorting local drug dealers who are not members of the gang. Along with profitable rackets such as these, they have also been known to participate in vandalism and property crime, often for gang-pride reasons or simply enjoyment. This can include public graffiti (tagging) and «joyriding» in stolen vehicles.

The gang’s current primary illicit source of income is presumably in street-level drug distribution, however many Crip members may also make notable amounts of illegal funds from the black market sale of illicit firearms. Historically, the gang’s size and power was largely augmented by the profits from the street sale of crack cocaine throughout the 1980s showing that PCP, amphetamines and other drugs were not as lucrative for them and thus did not have as direct of an effect on the group’s increase in influence. Therefore, the gang’s initial phase of growth and popularity can, in some way, be directly traced back to the explosion crack cocaine in the United States during the 1980s.[citation needed]

Crip-on-Crip rivalries

The Crips became popular throughout southern Los Angeles as more youth gangs joined; at one point they outnumbered non-Crip gangs by 3 to 1, sparking disputes with non-Crip gangs, including the L.A. Brims, Athens Park Boys, the Bishops, The Drill Company, and the Denver Lanes. By 1971 the gang’s notoriety had spread across Los Angeles.

By 1971, a gang on Piru Street in Compton, California, known as the Piru Street Boys, formed and associated itself with the Crips as a set. After two years of peace, a feud began between the Pirus and the other Crip sets. It later turned violent as gang warfare ensued between former allies. This battle continued and by 1973, the Pirus wanted to end the violence and called a meeting with other gangs targeted by the Crips. After a long discussion, the Pirus broke all connections to the Crips and started an organization that would later be called the Bloods,[45] a street gang infamous for its rivalry with the Crips.

Since then, other conflicts and feuds were started between many of the remaining Crip sets. It is a common misconception that Crip sets feud only with Bloods. In reality, they also fight each other—for example, the Rolling 60s Neighborhood Crips and 83 Gangster Crips have been rivals since 1979. In Watts, the Grape Street Crips and the PJ Watts Crips have feuded so much that the PJ Watts Crips even teamed up with a local Blood set, the Bounty Hunter Bloods, to fight the Grape Street Crips.[46] In the mid-1990s, the Hoover Crips rivalries and wars with other Crip sets caused them to become independent and drop the Crip name, calling themselves the Hoover Criminals.

Alliances and rivalries

Rivalry with the Bloods

The Bloods are the Crips’ main stereotypical rival. The Bloods initially formed to provide Piru Street Gang members protection from the Crips. The rivalry started in the 1960s when Washington and other Crip members attacked Sylvester Scott and Benson Owens, two students at Centennial High School. After the incident, Scott formed the Pirus, while Owens established the West Piru gang.[47] In late 1972, several gangs that felt victimized by the Crips due to their escalating attacks joined the Pirus to create a new federation of non-Crip gangs that later became known as Bloods. Between 1972 and 1979, the rivalry between the Crips and Bloods grew, accounting for a majority of the gang-related murders in southern Los Angeles. Members of the Bloods and Crips occasionally fight each other and, as of 2010, are responsible for a significant portion of gang-related murders in Los Angeles.[48] This rivalry is also believed to be behind the 2022 Sacramento shooting, where 6 people were killed.[49]

Alliance with the Folk Nation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as many Crip gang members were being sent to various prisons across the country, an alliance was formed between the Crips and the Folk Nation in Midwest and Southern U.S. prisons. This alliance was established to protect gang members incarcerated in state and federal prison. It is strongest within the prisons, and less effective outside. The alliance between the Crips and Folks is known as «8-ball». A broken 8-ball indicates a disagreement or «beef» between Folks and Crips.[35]

See also

- African-American organized crime

- Gangs in Los Angeles

- List of California street gangs

- Crip Walk

- Crips and Bloods: Made in America

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e «Criminal Street Gangs», United States Department of Justice (May 12, 2015)

- ^ Matt Kwong (January 19, 2015), «Canada’s gang hotspots — are you in one?», Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ a b «Appendix B. National-Level Street, Prison, and Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Profiles – Attorney General’s Report to Congress on the Growth of Violent Street Gangs in Suburban Areas (UNCLASSIFIED)». www.justice.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ «In our world, killing is easy’: Latin Kings part of a web of organized crime alliances, say former gangsters and law enforcement officials». MassLive. December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ «Major Prison Gangs(continued)». Gangs and Security Threat Group Awareness. Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/9400/gilbert_thesis.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ «Los Angeles-based Gangs — Bloods and Crips». Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on October 27, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Echo Day (December 12, 2019), «Here’s what we know about the Gangster Disciple governor who was sentenced to 10 years in prison», The Leader

- ^ «Juggalos: Emerging Gang Trends and Criminal Activity Intelligence Report» (PDF). Info.publicintelligence.net. February 15, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Michael Roberts (July 10, 2015), «Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Recruiting Military? Report Cites Colorado Murder», Westword

- ^ «Los Angeles Gangs and Hate Crimes», Police Law Enforcement Magazine, February 29, 2008

- ^ Montaldo, Charles (2014). «The Aryan Brotherhood: Profile of One of the Most Notorious Prison Gangs». About.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Rhian Daly (May 1, 2019), Rival gangs Crips And Bloods talk «historic» coming together following Nipsey Hussle’s murder», NME

- ^ Sam Quinones (October 18, 2007), «Gang rivalry grows into race war», Los Angeles Times

- ^ Brad Hamilton (October 28, 2007), «Gangs of New York», New York Post

- ^ «Gang Information», bethlehem-pa.gov (2019)

- ^ People v. Parsley, Court Listener (August 11, 2016)

- ^ Herbert C. Covey (2015), Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture

- ^ «Not on our turf: California gangs create havoc here»,[permanent dead link], Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 28, 1994.

- ^ «Bloods Gang Members Sentenced to Life in Prison for Racketeering Conspiracy Involving Murder and Other Crimes», United States Department of Justice (October 27, 2020)

- ^ Ben Ehrenreich (July 21, 1999), «Ganging up in Venice», LA Weekly

- ^ a b c d U.S. Department of Justice, Crips.

- ^ Failla, Zak (September 9, 2022). «Maryland Gang Member Who Goes By ‘Crazy’ Sentenced For Assaulting Fellow ‘Crip’ Behind Bars». Daily Voice. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Meghann, Cuniff (August 8, 2022). «‘Boss of Bosses’ Crips Gang Leader Sentenced to Decades in Federal Prison for Racketeering Murder Conspiracy». Law & Crime. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ «Los Angeles». Inside. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Dunn, William (2008). Boot: An LAPD Officer’s Rookie Year in South Central Los Angeles. iUniverse. p. 76. ISBN 9780595468782.

- ^ Stacy Peralta (Director), Stacy Peralta & Sam George (writers), Baron Davis et al. (producer), Steve Luczo, Quincy «QD3» Jones III (executive producer) (2009). Crips and Bloods: Made in America (TV-Documentary). PBS Independent Lens series. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ «Timeline: South Central Los Angeles». PBS (part of the «Crips and Bloods: Made in America» TV documentary). April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^

Sharkey, Betsy (February 6, 2009). «Review: ‘Crips and Bloods: Made in America’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009. - ^

Cle Sloan (Director), Antoine Fuqua and Cle Sloan (producer), Jack Gulick (executive producer) (2009). Keith Salmon (ed.). Bastards of the Party (TV-Documentary). HBO. Retrieved May 15, 2009. - ^ a b c d Williams, Stanley Tookie; Smiley, Tavis (2007). Blue Rage, Black Redemption. Simon & Schuster. pp. xvii–xix, 91–92, 136. ISBN 1-4165-4449-6.

- ^ Leonard, Barry (November 2009). National Drug Threat Assessment 2008. DIANE Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4379-1565-5.

- ^ Finley, Laura L. (October 1, 2018). Gangland: An Encyclopedia of Gang Life from Cradle to Grave [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4408-4474-4.

- ^ Vigil, James Diego (November 3, 2021). The Projects: Gang and Non-gang Families in East Los Angeles. University of Texas Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-292-79509-9.

- ^ a b Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ «The Crips: Prison Gang Profile».

- ^ =Alliances, Conflicts, and Contradictions in Montreal’s Street Gang Landscape, Karine Descormiers and Carlo Morselli, International Criminal Justice Review (October 17, 2020)

- ^ Toronto police, numerous other forces, dismantle ‘violent street gang’ known as Eglinton West Crips Jessica Patton, Global News (October 29, 2020)

- ^ Covey, Herbert. Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture: A Guide to an American Subculture. p. 9.

- ^ «Gangs Increasing in Military, FBI Says». Military.com. McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. June 30, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Capozzoli, Thomas and McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, p. 72. ISBN 1-57444-283-X.

- ^ «War and Peace in Watts» Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (July 14, 2005). LA Weekly. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Garrison, Jessica; Mejia, Brittany; Chabria, Anita (April 6, 2022). «At least five shooters involved in Sacramento massacre, gang ties likely, police say». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

General

- Leon Bing (1991). Do or Die: America’s Most Notorious Gangs Speak for Themselves. Sagebrush. ISBN 0-8335-8499-5

- Yusuf Jah, Sister Shah’keyah, Ice-T, UPRISING : Crips and Bloods Tell the Story of America’s Youth In The Crossfire, ISBN 0-684-80460-3

- Capozzoli, Thomas og McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, side. 72 ISBN 1-57444-283-X

- National Drug Intelligence Center (2002). Drugs and Crime: Gang Profile: Crips (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved June 21, 2009. Product no. 2002-M0465-001.

- Shakur, Sanyika (1993). Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member, Atlantic Monthly Pr, ISBN 0-87113-535-3

- Colton Simpson, Ann Pearlman, Ice-T (Foreword) (2005). Inside the Crips : Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang (HB) ISBN 0-312-32929-6

- Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- Stanley Tookie Williams (2005). Blue Rage, Black Redemption: A Memoir (PB) ISBN 0-9753584-0-5

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crips.

- PBS Independent Lens program on South Los Angeles gangs

- Snopes Urban Legend – The origin of the name Crips

Состоящая из афроамериканцев банда Crips считается одной из самых крупных в США. В настоящий момент ее членами являются около 60 000 человек, и численность постепенно растет. Банда Crips и ее противостояние с другой черной группировкой Bloods уже стала частью американской культуры.

Содержание

- Появление

- Война синих и красных

- Устройство и традиции банды

История появления

В 1960-е годы в Лос-Анджелесе у чернокожего подростка из небогатой семьи перспектив в жизни практически не было. Люди массово сидели без работы и не могли получить качественного образования. Из-за сохранившейся расовой дискриминации цветная молодежь оказывалась улице, где и пыталась найти способы подняться по социальной лестнице.

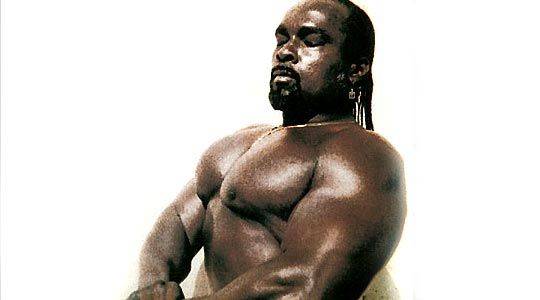

Банда Crips появилась в 1969 году. У ее истоков стояли два человека: Стэнли «Туки» Уильямс и Рэймонд Вашингтон. Уильямсу в тот момент было 16 лет, он заканчивал школу, занимался бодибилдингом и руководил небольшой бандой. Авторитета «Туки» добавляло то, что он недавно вышел из тюрьмы, в которую ненадолго попал за угон машины.

Вашингтон тогда тоже был главой местной молодежной банды, и он предложил Стэнли объединить силы для борьбы с другими группировками. Так появился новый альянс под названием Crips.

«Крипы» сразу же начали создавать себе романтический образ – они хотели, чтобы их видели в качестве Робин Гудов, которые борются за права черных. Позже Уильямс говорил, что он представлял себе Crips в виде наследников дела знаменитых «Черных пантер» – чернокожих левых радикалов из США.

Версий появления названия банды две.

- Банда Рэймонда Вашингтона до объединения называлась Avenue Cribs. Журналисты вполне могли неправильно транскрибировать это название, и меткое слово закрепилось в уличном лексиконе.

- Членов преступной группировки местное население называло «cripples», то есть «калеки». Причиной этого стала характерная для бандитов шаркающая походка вразвалку.

С политической борьбой у Crips не вышло. В отличие от «Черных пантер», вкладывавших в свои действия немалый идеологический заряд, «калеки» просто стремились к тому, чтобы установить контроль над улицами Лос-Анджелеса.

Война синих и красных

Crips в борьбе с конкурентами действовали очень жестко, не гнушаясь убийств. Мелкие банды боялись оказаться уничтоженными под этим катком, поэтому они собрали собственный альянс под названием Bloods. Летом 1972 года после серии перестрелок с трупами с обеих сторон между бандами началась война.

Синий стал отличительным цветом группировки после убийства в 1973 году 16-летнего Кертисса Морроу, который был правой рукой «Туки» и имел прозвище «Будда». Убитый всегда носил голубую бандану, и на его похороны тысячи «крипов» пришли именно в таком головном уборе. «Блады» взяли себе хорошо сочетающийся с их названием красный цвет.

В Bloods членов всегда было меньше, чем в Crips. Чтобы выжить, «красные» в основу своей тактики положили максимальную агрессивность – они жестоко атаковали противника при любом удобном случае.

Устройство и традиции банды

Crips – классическая зонтичная структура из множества мелких банд, объединенных в «сеты». У группировок внутри таких объединений зачастую немало противоречий, и они враждуют между собой, объединяясь только для ведения общей войны «синих» и «красных».

Для вступления в ряды «калек» парню необходимо показать, насколько он смел и лоялен банде. Лучший способ этого – нападение на члена конкурирующей группировки. Для девушек инициация выглядит иначе – им нужно переспать с кем-то из старших членов банды.

В рядах Crips поддерживается мнение о превосходстве черной расы. В связи с этим бандиты активно пользуются словами на суахили. Способы заработка у «крипов» традиционные: убийства, грабежи, сутенерство, сбыт краденого. Главной золотой жилой, как и для многих других группировок, является наркоторговля.

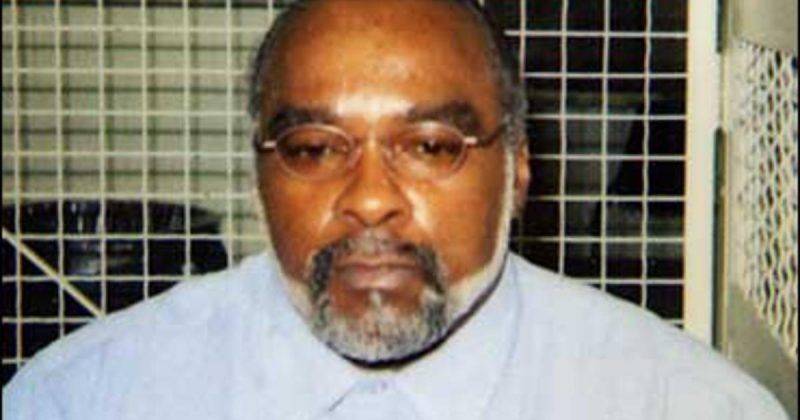

Лидеры первой волны Crips уже мертвы. Рэймонда Вашингтона застрелили в 1979 году, когда ему было 26 лет. Стэнли «Туки» Уильямса тогда же арестовали за убийство 4 человек и приговорили к смертной казни. Уильямс просидел за решеткой около четверти века, где стал писателем, убеждавшим в своих произведениях подростков из гетто не становиться преступниками. «Туки» получил премию президента США, он 9 раз выдвигался на Нобелевскую премию (4 как литератор и 5 за мир). В 2004 году вышел фильм «Искупление» от режиссера Вонди Куртис-Холла, рассказывающий о судьбе Уильямса.

Когда «Туки» подал очередное прошение о помиловании, руководивший в тот момент Калифорнией Арнольд Шварценеггер отказал в его удовлетворении. 13 декабря 2005 года, несмотря на слабые протесты общественности, Стэнли Уильямса казнили путем введения смертельной инъекции. За процессом приведения приговора в исполнение наблюдали около 50 человек.

Больше всего членов банды Crips живет на их родине – в Калифорнии. Через какое-то время после появления группировки «крипов» начали замечать и на противоположном берегу Штатов. Бандиты не могли обойти своим вниманием Нью-Йорк, который многие считают главным городом планеты. За пределами США тоже появляются группировки, копирующие стилистику «калек».

Кроме Bloods к основным врагам банды Crips также относятся американские белые нацисты («Арийское братство», «Нацистские бунтари») и латиносы из Mara Salvatrucha. А в состав банды в разное время входили следующие хип-хоп исполнители: Eazy-E, Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg, WC (Dub-C), Kurupt, MC Ren, OG Lim,Mc Eiht. и другие.

Crips (с англ. «Калеки») — уличная банда, преступное сообщество в США, состоящее преимущественно из афроамериканцев. Свое название банда получила после случая, в 1971 году члены банды напали на пожилых японок, которые затем описали преступников как хромых (cripple), так как все участники нападения были с тросточками. Об этом происшествии написали местные газеты, и за бандой закрепилось название — Crips.

Отличительный знак участников банды — ношение бандан (и одежды в общем) в синих оттенках, иногда — ношение тросточек, своя распальцовка и свой алфавит. В среде банды также возник знаменитый танец C-walk.

Создание Крипс

В 1969 году житель Лос-Анджелеса Рэймонд Вашингтон собрал группу живущих по соседству чернокожих подростков в банду, названную Baby Avenues. Рэй и его друг Стэнли «Tookie» Уильямс находились под впечатлением славы Черных Пантер. Юнцы (вожакам было по 15 лет, надо полагать и остальные участники банды были приблизительно того же возраста) стремились превратить Baby Avenues в серьезную силу. Участники банды называли себя Avenues Cribs, (crib – лачуга, «хата») поскольку проживали в районе Central Avenue. Но в отличии от своих предшественников, новое поколение «политику не хавало». Идеи Пантер об общественном контроле над улицами они поняли превратно, а их деятельность свелась к банальному криминалу.

Крипс не сумели распространить революционные идеи 60-х, зато преуспели в вопросах моды. Военный стиль и черные кожаные куртки – вот и все, что они позаимствовали у Черных Пантер. В качестве опознавательного знака Cribs носили синие платки (тогда их еще не называли банданнами), повязывая их на голову или на шею. Синий цвет становится их отличительным знаком, их торговой маркой. Отдельные щеголи разгуливали по улицам Лос-Анджелеса с тросточками, которые и принесли им название, известное сегодня всему миру.

В 1971 году несколько участников Cribs напали на группу пожилых японок. Жертвы ограбления, будучи несведущими в моде бедных кварталов, описали нападавших как инвалидов (cripple – калека, инвалид, особенно часто – хромой), поскольку все они были с тросточками. Местная пресса написала об инциденте, видоизменив название банды в Crips, и оно прижилось именно в таком виде. Существует также версия о происхождении слова Crips от местного сленгового термина crippin (красть, грабить). Но так или иначе, группировка заслужила известность и начала вовлекать в свои ряды все новых и новых подростков.

Количество преступлений, совершаемых ребятами в черных кожаных куртках (видимо что-то есть в черной коже, если советский рэкет конца 80-х неосознанно скопировал имидж заокеанской шпаны) росло в геометрической прогрессии, газеты пестрели криминальными сводками. Пресса даже придумала термин «Крипмания», обозначавший эпидемию драк и перестрелок между темнокожими школьниками из южной части Лос-Анджелеса. Появившись в окрестностях 78-ой улицы на востоке мегаполиса, за три года своего существования Crips распространили свое влияние на западные и южные районы Лос-Анджелеса, а также на его пригороды Комптон и Инглвуд. В 1972 году с деятельностью crips было связано 29 убийств в Лос-Анджелесе, 17 – в его пригородах, еще 9 – в одном только Комптоне.

Банда Bloods

Между 1973 и 1975 агрессивная экспансия Crips на все новые и новые районы Лос-Анджелеса начинает вызывать противодействие со стороны других криминальных группировок. Чтобы противостоять превосходящим силам, противники Crips создают коалицию, которая получает название Bloods. Их символом становится кровь, красный цвет платков; говорят, что уже в 90-х в домах самых авторитетных участников Bloods (таких, например, как Suge Knight) даже стены были выкрашены в алый.

Считается, что создание Bloods произошло после того, как небольшая банда из Комптона Piru Street Boys (известная тем, что взрастила рэппера Game) не нашла понимания со значительно превосходящей ее количественно Compton Crips и вступила с ней в открытый конфликт. Стремясь заручиться поддержкой других группировок, лидеры Piru Street Boys собрали весь хардкор других не входящих в Crips уличных банд Лос-Анджелеса, таких как L.A. Brims, чьи участники были виновны в убийстве нескольких «синих». На этой встрече в Комптоне, на Piru Street, и было принято решение о создании альянса Bloods.

Чтобы легче понять принципиальную разницу между Crips и Bloods, необходимо вспомнить блестящий советский фильм «Кин-Дза-Дза». Действующие лица фильма четко делятся на две группы – пацаки и четлане. Разница между ними заключалась в реакции на специальную черную коробочку с двумя лампочками. Когда коробочку подносили к пацаку загоралась красная, к четланину – зеленая. А когда дотошный землянин потребовал подробностей, получил ответ, не ручаюсь за точность цитаты, «Ты что, тупой? Красное от зеленого отличить не можешь?». Ровно такая же ситуация с Crips и Bloods. Одни синие, хоть и не алкоголики, другие красные, хотя и не коммунисты. Торгуют наркотиками, занимаются мелким рэкетом, мочат врагов и полицейских и смертно ненавидят друг друга.

Банда Крипс

Обе группировки быстро обросли целой системой символов и обрядов. В их числе посвящение в участники банды, заключавшееся в совершении преступления в присутствии свидетелей из числа банды. Девушки становились участницами группировки после совершения полового акта с несколькими старшими участниками. Появились специальные гангстерские граффити, как просто «метившие» территорию, так и имевшие чисто прикладное значение: специальные знаки и символы для посвященных, передающие в зашифрованном виде информацию для участников банды, своеобразное средство оповещения. Появились и особые криминальные тату.

United Blood Nation

В 1980-х Crips и Bloods активно включаются в торговлю новым для США наркотиком – крэком. Банды Лос-Анджелеса налаживают связи с криминальными группировками Центральной и Южной Америки, вовлеченными в наркотраффик. Crips и Bloods дотягиваются и до противоположного побережья Америки – свои «синие» и «красные» появляются в Нью-Йорке.

Восточные Crips в большинстве своем состояли из иммигрантов, приехавших в США из Центральной Америки. Там с середины 80-х активно действовали подразделения «синих». Перебираясь в США, они селились на всем правом берегу от Нью-Джерси до Флориды. В Нью-Йорке они создали Harlem Mafia Crips, 92 Hoover Crips, Rollin 30’s Crips и еще несколько группировок.

Нью-Йоркские Bloods сформировались начале 90-х в тюрьме С-73 на Rikers Island. В этом исправительном учреждении содержали тех, кого у нас в стране назвали бы «отрицалами». Из других тюрем на Rikers Island свозили самых необузданных заключенных. В то время большинство заключенных C-73 были участниками латиноамериканской банды Latin Kings. Латиносы были многочисленны и хорошо организованы, они унижали афроамериканских заключенных, заставляли их выполнять наиболее грязную работу. Вокруг наиболее жесткоих и волевых афроамериканцев, имевших отношение к Bloods, сплотилась группа, назвавшая себя United Blood Nation, призванная давать отпор Латинским Королям.

Тюремная банда United Blood Nation скопировала правила и обычаи калифорнийских Bloods. Впоследствие лидеры UBN сформировали в Нью-Йорке и его пригородах около десятка группировок «красных», таких как Mad Stone Villains (MSV), Valentine Bloods (VB), Gangster Killer Bloods (GKB), Hit Squad Brims (HSB), Sex, Money and Murder (SMM). Из Нью-Йорка они распространились по всему восточному побережью США.

Только Fuckты

Bloods зачастую называют себя Damu («кровь» на африканском языке суахили) или Dawg (DOGS). Участники Bloods украшают себя татуировками с изображением собаки, как правило бульдога. Bloods также используют аббревиатуру M.O.B. (Member of Blood или Money Over Bitches).

В 1972-ом В Лос-Анджелесе насчитывали 11 гангстерских группировок. Еще 4 действовали в Комптоне, по одной – в Афинах и Инглвуде. Через 25 лет в Лос-Анджелесе их было 138, в Комптоне – 36, в Инглвуде – 14, в Лонг-Бич – 10. Всего в Лос-Анджелесе и его окрестностях насчитывают свыше 300 банд.

Большинство калифорнийских Crips и Bloods афро-американцы. Исключение составляют действующие в Лонг-Бич Samoan Crip, Samoan Blood из Карсон-Сити, в составе которой самоанцы, а также Inglewood Crip, состоящая из уроженцев тихоокеанского островного государства Тонга.

Главными соперниками «красных» и «синих» в Калифорнии являются Latin Kings – испаноязычные банды, состоящие из потомков мексиканских и южноамериканских иммигрантов. Latin Kings приблизительно равны по численности и степени влияния и Bloods, и Crips, они также действуют по всей территории страны, хотя традиционной их территорией считаются южные и западные штаты, и в первую очередь Калифорния. В последнее время наметился рост азиатских криминальных группировок.

Наиболее известные участники Bloods: Suge Knight, Game, B-Real (Cypress Hill). Suge вовсю использовал свои криминальные связи для устранения конкурентов. Game рос в семье участников Crips, но вслед за своим старшим братом Big Fase, авторитетным участником Bloods, вошел в ряды красных. B-Real завязал с гангбангингом после того, как чуть не погиб в перестрелке. В рядах Crips состоял Snoop Dogg, но это не мешало ему работать на Death Row, лейбле Suge Knight-а. Sen Dog, еще один участник Cypress Hill, появлялся перед публикой в майке «Latin King».

Рэй Вашингтон, основатель первой банды Crips, был убит в 1979 году в возрасте 26 лет. Его компаньон Туки Уильямс еще жив – пока. Он находится в одном из исправительных заведений Калифорнии, в камере смертников. Темнокожий продавец винила в английском фильме «Human Traffic» говорил покупателям, что «когда рэппер попадает за решетку, его пластинки дорожают на 10 фунтов, а если его сажают на электрический стул, цены вообще взлетают в стратосферу». Если это так, то стоимость книги «Original Gangster», автором которой является Стэнли «Туки» Уильямс уже в поднебесье.

Источник

|

|

В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации.

Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

Crips (с англ. «Калеки») — уличная банда, преступное сообщество в США, состоящее преимущественно из афроамериканцев. Входит в крупнейшую бандитскую систему США — Folk Nation. По состоянию на 2007 год численность членов Crips оценивается примерно в 40 тысяч человек. Известна противостоянием с другими преступными группировками, входящими в альянс Bloods, и хотя у Bloods в данный момент намного больше членов, чем у Crips, «синие» дают хороший отпор Bloods. «Красные» до сегодняшнего времени не могут отобрать у Crips ни одной территории. Crips cостоит из множества группировок, большинство из которых находится в Лос-Анджелесе.

Отличительный знак участников банды — ношение бандан (и одежды в общем) в синих оттенках, иногда — ношение тросточек. Для того чтобы вступить в банду, парню нужно совершить преступление при свидетелях, а девушке вступить в половое сношение со старшими членами банды. В среде банды также возник знаменитый танец c-walk (англ.). Развит собственный жаргон и алфавит.

Основана в Лос-Анджелесе в 1969 году 15-летним подростком Рэймондом Вашингтоном и его другом Стэнли «Туки» Уильямсом. Первоначально Рэймонд Вашингтон назвал свою банду Baby Avenues, находясь под впечатлением от движения «Чёрные пантеры». Позднее они стали называть себя Avenues Cribs (англ. crib — лачуга) или Cribs.

В 1971 году члены банды напали на пожилых японок, которые затем описали преступников как хромых (англ. cripple), так как все участники нападения были с тросточками. Об этом происшествии написали местные газеты, и за бандой закрепилось новое название — Crips. В 1979 году Вашингтон был застрелен в возрасте 26 лет. Личность его убийцы не установлена до сих пор.

В том же году другой создатель банды Стэнли «Туки» Уильямс был арестован за убийство четырёх человек (продавца, супружеской пары и их дочери). Он был приговорён к смертной казни. Находясь в заключении около 25 лет, Уильямс занимался литературной деятельностью, в своих произведениях он убеждал детей из гетто не участвовать в преступных группах. Уильямс девять раз выдвигался на Нобелевскую премию (пять за мир и четыре за его литературные произведения), был награждён премией президента США, в Голливуде был снят фильм о его жизни. Несмотря на немногочисленные протесты общественности, губернатор Калифорнии Арнольд Шварценеггер отказался удовлетворить прошение о его помиловании, и 13 декабря 2005 года Уильямс был казнён посредством введения смертельной инъекции.

В настоящее время банда Crips считается одной из крупнейших в США. Её членам инкриминируются убийства, грабежи, торговля наркотиками и другие преступления. Больше всего Crips в Калифорнии, откуда она начала развиваться. Позже свои «синие» появились и на противоположном берегу США. В настоящее время даже вне США появляются группировки, копирующие культуру «Калек». Также, стоит рассказать об Эрике Вульферте, одного из самых ярких представителей банды, в 1989 году на Вульферта было совершенно покушение вражеской банды Bloods, в него стреляли шесть раз, и ни одна пуля так и не задела жизненно важные органы.

Прочие факты

- В 7 сезоне 2 серии «Сумасшедшие калеки» сериала South Park сюжет основан на конфликте банд Crips и Bloods.

См. также

- Asian Boyz — союзники Crips

- Bloods — враги Crips

Ссылки

- Побоище в Лос-Анджелесе (статья об уличной преступности в Лос-Анджелесе)

- History of Crip Gangs in LA

- The origin of the name Crips

- L.A.-based gangs

- Crips and Blood Alphabet

- [1]

- [2]

Crips tattoos |

|

| Founded | 1969; 54 years ago |

|---|---|

| Founders | Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams |

| Founding location | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Territory | 41 U.S. states[1] and Canada[2] |

| Ethnicity | Predominately African American[1] |

| Membership (est.) | 30,000–35,000[3] |

| Activities | Drug trafficking, murder, assault, auto theft, burglary, extortion, fraud, robbery[1] |

| Allies |

|

| Rivals |

|

| Notable members |

|

The Crips is an alliance of street gangs that is based in the coastal regions of Southern California. Founded in Los Angeles, California, in 1969, mainly by Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams, the Crips were initially a single alliance between two autonomous gangs; it is now a loosely-connected network of individual «sets», often engaged in open warfare with one another. Traditionally, since around 1973, its members have worn blue clothing.

The Crips are one of the largest and most violent associations of street gangs in the United States.[22] With an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 members in 2008,[3] the gangs’ members have been involved in murders, robberies and drug dealing, among other crimes. They have a long and bitter rivalry with the Bloods.

Some self-identified Crips have been convicted of federal racketeering.[23][24]

Etymology

Some sources suggest that the original name for the alliance, «Cribs», was narrowed down from a list of many options and chosen unanimously from three final choices, over the Black Overlords and the Assassins. Cribs was chosen to reflect the young age of the majority of the gang members. The name evolved into «Crips» when gang members began carrying around canes to display their «pimp» status. People in the neighborhood then began calling them cripples, or «Crips» for short.[25] In February 1972 the Los Angeles Times used the term.[22] Another source suggests «Crips» may have evolved from «Cripplers», a 1970s street gang in Watts, of which Washington was a member.[26] The name had no political, organizational, cryptic, or acronymic meaning, though some have suggested it stands for «Common Revolution In Progress», a backronym. According to the film Bastards of the Party, directed by a member of the Bloods, the name represented «Community Revolutionary Interparty Service» or «Community Reform Interparty Service».

History

Gang activity in South Central Los Angeles has its roots in a variety of factors dating to the 1950s, including: post-World War II economic decline leading to joblessness and poverty; racial segregation of young African American men, who were excluded from organizations such as the Boy Scouts, leading to the formation of black «street clubs»; and the waning of black nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and the Black Power Movement.[27][28][29][30]

Stanley Tookie Williams met Raymond Lee Washington in 1969, and the two decided to unite their local gang members from the west and east sides of South Central Los Angeles in order to battle neighboring street gangs. Most of the members were 17 years old.[31] Williams however appears to discount the sometimes-cited founding date of 1969 in his memoir, Blue Rage, Black Redemption.[31]

In his memoir, Williams also refuted claims that the group was a spin-off of the Black Panther Party or formed for a community agenda, writing that it «depicted a fighting alliance against street gangs—nothing more, nothing less.»[31] Washington, who attended Fremont High School, was the leader of the East Side Crips, and Williams, who attended Washington High School, led the West Side Crips.

Williams recalled that a blue bandana was first worn by Crips founding member Curtis «Buddha» Morrow, as a part of his color-coordinated clothing of blue Levis, a blue shirt, and dark blue suspenders. A blue bandana was worn in tribute to Morrow after he was shot and killed on February 23, 1973. The color then became associated with Crips.[31]

By 1978, there were 45 Crip gangs, called sets, in Los Angeles. They were heavily involved in the production of PCP,[32] marijuana and amphetamines.[33][34] On March 11, 1979, Williams, a member of the Westside Crips, was arrested for four murders and on August 9, 1979, Washington was gunned down. Washington had been against Crip infighting and after his death several Crip sets started fighting against each other. The Crips’ leadership was dismantled, prompting a deadly gang war between the Rollin’ 60 Neighborhood Crips and Eight Tray Gangster Crips that led nearby Crip sets to choose sides and align themselves with either the Neighborhood Crips or the Gangster Crips, waging large-scale war in South Central and other cities. The East Coast Crips (from East Los Angeles) and the Hoover Crips directly severed their alliance after Washington’s death. By 1980, the Crips were in turmoil, warring with the Bloods and against each other. The gang’s growth and influence increased significantly in the early 1980s when crack cocaine hit the streets and Crip sets began distributing the drug. Large profits induced many Crips to establish new markets in other cities and states. As a result, Crips membership grew steadily and the street gang was one of the nation’s largest by the late 1980s.[35][36] In 1999, there were at least 600 Crip sets with more than 30,000 members transporting drugs in the United States.[22]

Membership

As of 2015, the Crips gang consists of between approximately 30,000 and 35,000 members and 800 sets, active in 221 cities and 41 U.S. states.[1] The states with the highest estimated number of Crip sets are California, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Members typically consist of young African American men, but can be white, Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander.[22] The gang also began to establish a presence in Canada in the early 1990s;[37] Crip sets are active in the Canadian cities of Montreal and Toronto.[38][39]

In 1992 the LAPD estimated 15,742 Crips in 108 sets; other source estimates were 30,000 to 35,000 in 600 sets in California.[40]

Crips have served in the United States armed forces and on military bases in the United States and abroad.[41]

Practices

Language

Some practices of Crip gang life include graffiti and substitutions and deletions of particular letters of the alphabet. The letter «b» in the word «blood» is «disrespected» among certain Crip sets and written with a cross inside it because of its association with the enemy. The letters «CK», which are interpreted to stand for «Crip killer», are avoided and replaced by «cc». For example, the words «kick back» are written «kicc bacc», and block is written as «blocc». Many other words and letters are also altered due to symbolic associations.[42] Crips traditionally refer to each other as «Cuz» or «Cuzz», which itself is sometimes used as a moniker for a Crip. «Crab» is the most disrespectful epithet to call a Crip, and can warrant fatal retaliation.[43] Crips in prison modules in the 1970s and 1980s sometimes spoke Swahili to maintain privacy from guards and rival gangs.[44]

Criminal rackets and street activities

As with most criminal street gangs, Crips have traditionally benefited monetarily from illicit activities such as illegal gambling, drug-dealing, pimping, larceny, and robbery.[1] Crips also profit from extorting local drug dealers who are not members of the gang. Along with profitable rackets such as these, they have also been known to participate in vandalism and property crime, often for gang-pride reasons or simply enjoyment. This can include public graffiti (tagging) and «joyriding» in stolen vehicles.

The gang’s current primary illicit source of income is presumably in street-level drug distribution, however many Crip members may also make notable amounts of illegal funds from the black market sale of illicit firearms. Historically, the gang’s size and power was largely augmented by the profits from the street sale of crack cocaine throughout the 1980s showing that PCP, amphetamines and other drugs were not as lucrative for them and thus did not have as direct of an effect on the group’s increase in influence. Therefore, the gang’s initial phase of growth and popularity can, in some way, be directly traced back to the explosion crack cocaine in the United States during the 1980s.[citation needed]

Crip-on-Crip rivalries

The Crips became popular throughout southern Los Angeles as more youth gangs joined; at one point they outnumbered non-Crip gangs by 3 to 1, sparking disputes with non-Crip gangs, including the L.A. Brims, Athens Park Boys, the Bishops, The Drill Company, and the Denver Lanes. By 1971 the gang’s notoriety had spread across Los Angeles.

By 1971, a gang on Piru Street in Compton, California, known as the Piru Street Boys, formed and associated itself with the Crips as a set. After two years of peace, a feud began between the Pirus and the other Crip sets. It later turned violent as gang warfare ensued between former allies. This battle continued and by 1973, the Pirus wanted to end the violence and called a meeting with other gangs targeted by the Crips. After a long discussion, the Pirus broke all connections to the Crips and started an organization that would later be called the Bloods,[45] a street gang infamous for its rivalry with the Crips.

Since then, other conflicts and feuds were started between many of the remaining Crip sets. It is a common misconception that Crip sets feud only with Bloods. In reality, they also fight each other—for example, the Rolling 60s Neighborhood Crips and 83 Gangster Crips have been rivals since 1979. In Watts, the Grape Street Crips and the PJ Watts Crips have feuded so much that the PJ Watts Crips even teamed up with a local Blood set, the Bounty Hunter Bloods, to fight the Grape Street Crips.[46] In the mid-1990s, the Hoover Crips rivalries and wars with other Crip sets caused them to become independent and drop the Crip name, calling themselves the Hoover Criminals.

Alliances and rivalries

Rivalry with the Bloods

The Bloods are the Crips’ main stereotypical rival. The Bloods initially formed to provide Piru Street Gang members protection from the Crips. The rivalry started in the 1960s when Washington and other Crip members attacked Sylvester Scott and Benson Owens, two students at Centennial High School. After the incident, Scott formed the Pirus, while Owens established the West Piru gang.[47] In late 1972, several gangs that felt victimized by the Crips due to their escalating attacks joined the Pirus to create a new federation of non-Crip gangs that later became known as Bloods. Between 1972 and 1979, the rivalry between the Crips and Bloods grew, accounting for a majority of the gang-related murders in southern Los Angeles. Members of the Bloods and Crips occasionally fight each other and, as of 2010, are responsible for a significant portion of gang-related murders in Los Angeles.[48] This rivalry is also believed to be behind the 2022 Sacramento shooting, where 6 people were killed.[49]

Alliance with the Folk Nation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as many Crip gang members were being sent to various prisons across the country, an alliance was formed between the Crips and the Folk Nation in Midwest and Southern U.S. prisons. This alliance was established to protect gang members incarcerated in state and federal prison. It is strongest within the prisons, and less effective outside. The alliance between the Crips and Folks is known as «8-ball». A broken 8-ball indicates a disagreement or «beef» between Folks and Crips.[35]

See also

- African-American organized crime

- Gangs in Los Angeles

- List of California street gangs

- Crip Walk

- Crips and Bloods: Made in America

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e «Criminal Street Gangs», United States Department of Justice (May 12, 2015)

- ^ Matt Kwong (January 19, 2015), «Canada’s gang hotspots — are you in one?», Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ a b «Appendix B. National-Level Street, Prison, and Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Profiles – Attorney General’s Report to Congress on the Growth of Violent Street Gangs in Suburban Areas (UNCLASSIFIED)». www.justice.gov. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ «In our world, killing is easy’: Latin Kings part of a web of organized crime alliances, say former gangsters and law enforcement officials». MassLive. December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ «Major Prison Gangs(continued)». Gangs and Security Threat Group Awareness. Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/9400/gilbert_thesis.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ «Los Angeles-based Gangs — Bloods and Crips». Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on October 27, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Echo Day (December 12, 2019), «Here’s what we know about the Gangster Disciple governor who was sentenced to 10 years in prison», The Leader

- ^ «Juggalos: Emerging Gang Trends and Criminal Activity Intelligence Report» (PDF). Info.publicintelligence.net. February 15, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Michael Roberts (July 10, 2015), «Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Recruiting Military? Report Cites Colorado Murder», Westword

- ^ «Los Angeles Gangs and Hate Crimes», Police Law Enforcement Magazine, February 29, 2008

- ^ Montaldo, Charles (2014). «The Aryan Brotherhood: Profile of One of the Most Notorious Prison Gangs». About.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Rhian Daly (May 1, 2019), Rival gangs Crips And Bloods talk «historic» coming together following Nipsey Hussle’s murder», NME

- ^ Sam Quinones (October 18, 2007), «Gang rivalry grows into race war», Los Angeles Times

- ^ Brad Hamilton (October 28, 2007), «Gangs of New York», New York Post

- ^ «Gang Information», bethlehem-pa.gov (2019)

- ^ People v. Parsley, Court Listener (August 11, 2016)

- ^ Herbert C. Covey (2015), Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture

- ^ «Not on our turf: California gangs create havoc here»,[permanent dead link], Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 28, 1994.

- ^ «Bloods Gang Members Sentenced to Life in Prison for Racketeering Conspiracy Involving Murder and Other Crimes», United States Department of Justice (October 27, 2020)

- ^ Ben Ehrenreich (July 21, 1999), «Ganging up in Venice», LA Weekly

- ^ a b c d U.S. Department of Justice, Crips.

- ^ Failla, Zak (September 9, 2022). «Maryland Gang Member Who Goes By ‘Crazy’ Sentenced For Assaulting Fellow ‘Crip’ Behind Bars». Daily Voice. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Meghann, Cuniff (August 8, 2022). «‘Boss of Bosses’ Crips Gang Leader Sentenced to Decades in Federal Prison for Racketeering Murder Conspiracy». Law & Crime. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ «Los Angeles». Inside. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Dunn, William (2008). Boot: An LAPD Officer’s Rookie Year in South Central Los Angeles. iUniverse. p. 76. ISBN 9780595468782.

- ^ Stacy Peralta (Director), Stacy Peralta & Sam George (writers), Baron Davis et al. (producer), Steve Luczo, Quincy «QD3» Jones III (executive producer) (2009). Crips and Bloods: Made in America (TV-Documentary). PBS Independent Lens series. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ «Timeline: South Central Los Angeles». PBS (part of the «Crips and Bloods: Made in America» TV documentary). April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^

Sharkey, Betsy (February 6, 2009). «Review: ‘Crips and Bloods: Made in America’«. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2009. - ^

Cle Sloan (Director), Antoine Fuqua and Cle Sloan (producer), Jack Gulick (executive producer) (2009). Keith Salmon (ed.). Bastards of the Party (TV-Documentary). HBO. Retrieved May 15, 2009. - ^ a b c d Williams, Stanley Tookie; Smiley, Tavis (2007). Blue Rage, Black Redemption. Simon & Schuster. pp. xvii–xix, 91–92, 136. ISBN 1-4165-4449-6.

- ^ Leonard, Barry (November 2009). National Drug Threat Assessment 2008. DIANE Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4379-1565-5.

- ^ Finley, Laura L. (October 1, 2018). Gangland: An Encyclopedia of Gang Life from Cradle to Grave [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4408-4474-4.

- ^ Vigil, James Diego (November 3, 2021). The Projects: Gang and Non-gang Families in East Los Angeles. University of Texas Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-292-79509-9.

- ^ a b Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ «The Crips: Prison Gang Profile».

- ^ =Alliances, Conflicts, and Contradictions in Montreal’s Street Gang Landscape, Karine Descormiers and Carlo Morselli, International Criminal Justice Review (October 17, 2020)

- ^ Toronto police, numerous other forces, dismantle ‘violent street gang’ known as Eglinton West Crips Jessica Patton, Global News (October 29, 2020)

- ^ Covey, Herbert. Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture: A Guide to an American Subculture. p. 9.

- ^ «Gangs Increasing in Military, FBI Says». Military.com. McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. June 30, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin’s Press. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Capozzoli, Thomas and McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, p. 72. ISBN 1-57444-283-X.

- ^ «War and Peace in Watts» Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (July 14, 2005). LA Weekly. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Garrison, Jessica; Mejia, Brittany; Chabria, Anita (April 6, 2022). «At least five shooters involved in Sacramento massacre, gang ties likely, police say». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

General

- Leon Bing (1991). Do or Die: America’s Most Notorious Gangs Speak for Themselves. Sagebrush. ISBN 0-8335-8499-5

- Yusuf Jah, Sister Shah’keyah, Ice-T, UPRISING : Crips and Bloods Tell the Story of America’s Youth In The Crossfire, ISBN 0-684-80460-3

- Capozzoli, Thomas og McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, side. 72 ISBN 1-57444-283-X

- National Drug Intelligence Center (2002). Drugs and Crime: Gang Profile: Crips (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved June 21, 2009. Product no. 2002-M0465-001.

- Shakur, Sanyika (1993). Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member, Atlantic Monthly Pr, ISBN 0-87113-535-3

- Colton Simpson, Ann Pearlman, Ice-T (Foreword) (2005). Inside the Crips : Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang (HB) ISBN 0-312-32929-6