Базовым понятием и одним из наиболее интересных и полезных объектов школьной математики является биссектриса. С её помощью доказываются многие положения планиметрии, упрощается решение задач.

Известные свойства позволяют рассматривать геометрические фигуры с разных точек зрения. Появляется вариативность при выборе пути доказательств.

Становится возможным использование инструмента алгебры, например, свойство пропорции, нахождение неизвестных величин, решение алгебраических уравнений при рассмотрении геометрических вопросов.

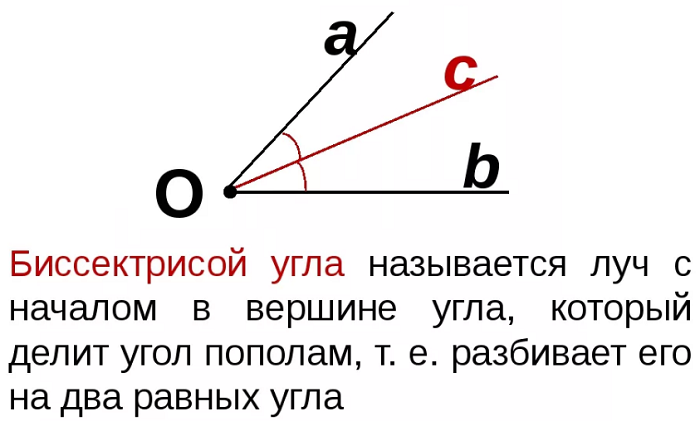

Что такое биссектриса в геометрии

Рассматривают луч, выходящий из вершины угла или его часть (отрезок), который делит угол пополам. Такой луч (или, соответственно, отрезок) называется биссектрисой.

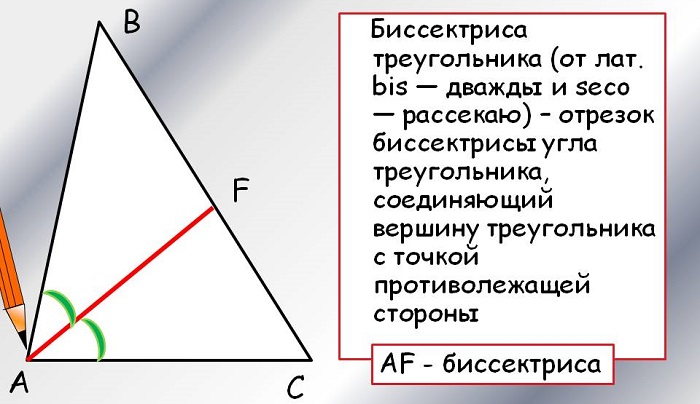

Часто для треугольников определение немного сужают, говоря об отрезке, соединяющем вершину угла, делящем его пополам, с точкой на противолежащей стороне. При этом рассматривается внутренняя область фигуры.

В то же время, часто при решении задач используются прямые, делящие внешние углы на два равных.

Биссектриса прямоугольного треугольника

Для прямоугольного треугольника одна из биссектрис образует равные углы, величины которых хорошо просчитываются (45 градусов).

Это помогает вычислять углы при решении задач, связанных с фигурами, которые можно представить в виде прямоугольных треугольников или прямоугольников.

В тупоугольном треугольнике биссектриса делит больший угол на равные части, величина которых меньше 900.

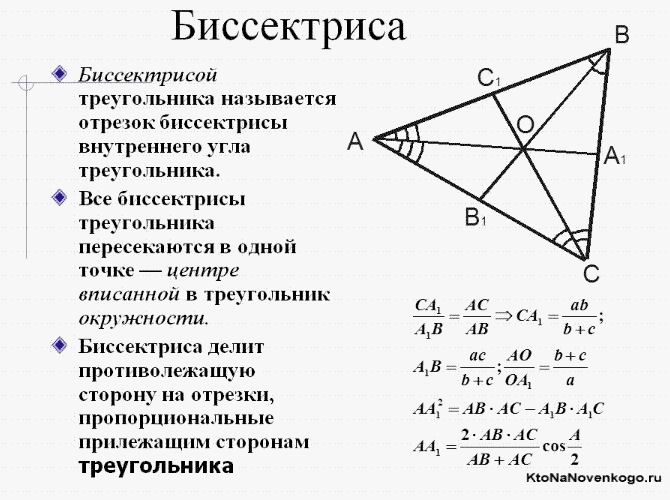

Свойства биссектрисы треугольника

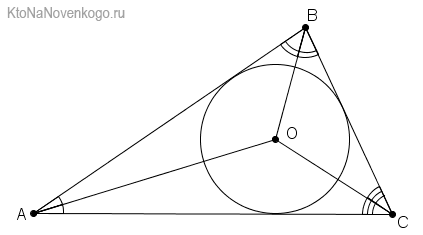

1. Каждая точка этой линии равноудалена от сторон угла. Часто эту характеристику выбирают в качестве определения, поскольку верно и обратное утверждение для любого произвольного треугольника. Это позволяет находить и радиус вписанной окружности.

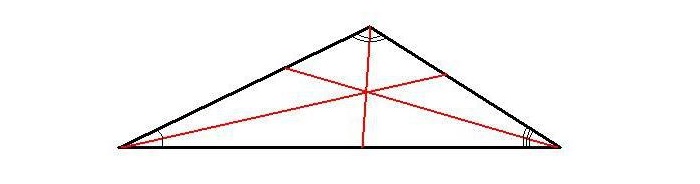

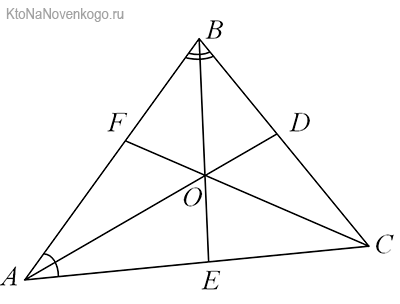

2. Все внутренние отрезки, делящие углы пополам, пересекаются в одной точке, которая является центром окружности, вписанной в фигуру, т. е. точка пересечения находится на равных расстояниях от сторон.

Данное свойство позволяет решать целый класс разнообразных задач, выводить формулы для радиусов вписанных окружностей правильных многоугольников.

Благодаря этому утверждению, легко доказывается следующее правило:

Площадь описанного многоугольника равна:

S = p∗r

где p – полупериметр, а r – радиус вписанной окружности.

Это позволяет находить решение не только планиметрических, но и стереометрических задач.

Важную роль играют внешние биссектрисы треугольника. Вместе с внутренними они образуют прямые углы;

3. Сумма величин двух прилежащих сторон, делённая на длину противолежащей стороны, задаёт отношение частей биссектрисы (считая от вершины), полученных точкой пересечения всех трёх соответствующих линий.

Некоторые виды геометрических фигур, в силу своих особенностей, порождают особые примечательные характеристики;

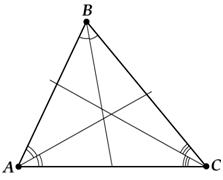

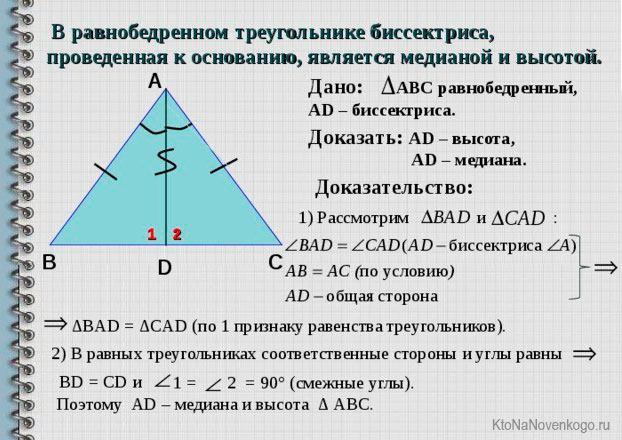

4. В равнобедренном треугольнике биссектриса, проведённая к основанию, одновременно является медианой и высотой. Две другие – равны между собой.

В этом случае основание параллельно внешней биссектрисе.

Обратное положение также имеет место. Если прямая проведена параллельно основанию равнобедренного треугольника через некоторую вершину, то внешняя биссектриса при этой вершине является частью этой линии;

5. Для равностороннего многоугольника важной характеристикой считается равенство всех биссектрис;

6. У правильного треугольника все внешние биссектрисы параллельны сторонам;

7. Выделяют несколько особенностей, среди которых есть следующая теорема:

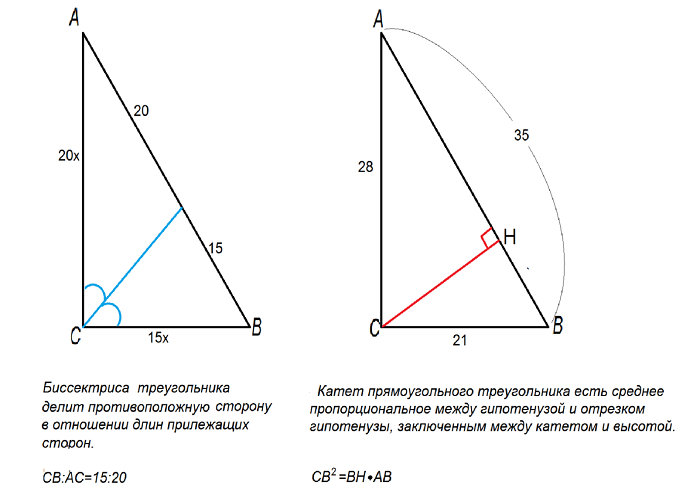

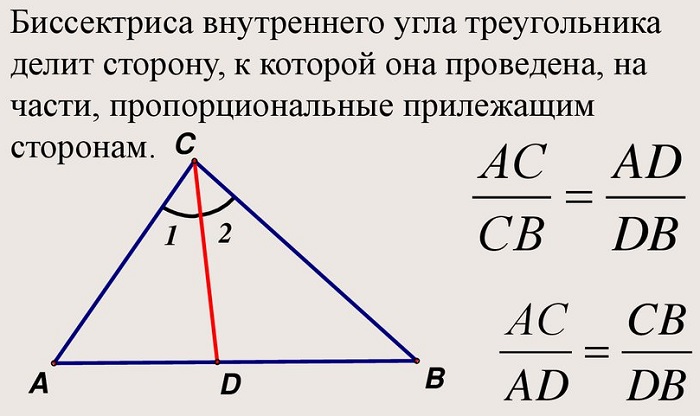

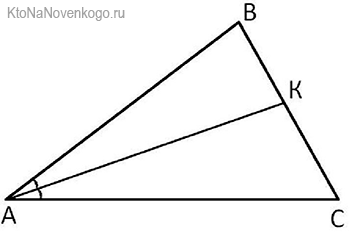

«Биссектриса треугольника делит противолежащую сторону на отрезки, пропорциональные двум другим сторонам».

Обратное утверждение («Прямая делит сторону на отрезки, пропорциональные двум другим сторонам») выражает признаки того, что рассматриваемая линия является внутренней биссектрисой;

8. Разносторонний треугольник позволяет определить взаимное расположение его высоты, медианы и биссектрисы, проведённых из одной точки. В частности, медиана и высота располагаются по разные стороны от третьей линии.

Все формулы биссектрисы в треугольнике

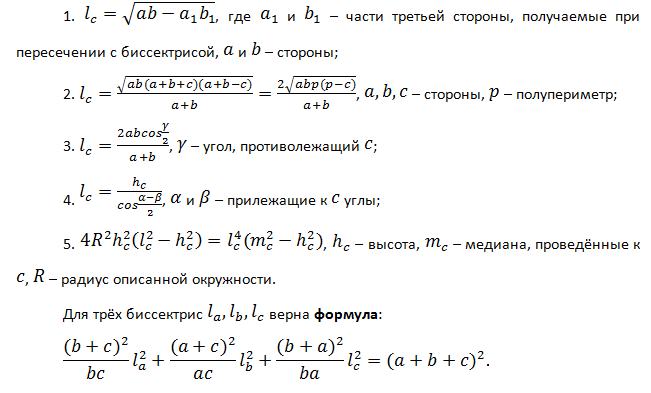

В зависимости от исходных данных, длина биссектрисы, проведённой к стороне C, lc, равна:

Примеры решения задач

Задача №1

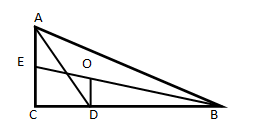

В ΔABC ∠C = 90°, проведена биссектриса острого угла. Отрезок, соединяющий её основание с точкой пересечения медиан, перпендикулярен катету. Найти углы заданной фигуры.

Решение.

Пусть ∠ACB = 90°, AD – биссектриса, BE – медиана, O – точка пересечения медиан, OD⊥BC.

Тогда OE : OB = 1 : 2по свойству медиан.

Так как OD⊥BC, то ODIIOC, следовательно, ΔBOD ∼ ΔBEC по второму признаку подобия, поэтому, по свойству подобных фигур, CD : DB = 1 : 2.

Это означает, что CA : AB = 1 : 2.

Так как катет равен половине гипотенузы, то ∠ABC = 30°, откуда ∠CAB = 60°.

Ответ: 90°, 60°, 30°.

Задача №2

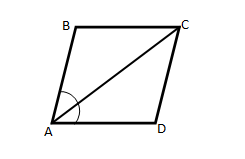

Диагональ параллелограмма делит его острый угол пополам. Доказать, что этот параллелограмм является ромбом.

Доказательство.

Так как ABCD – параллелограмм, то ∠DAC = ∠ACB, как накрест лежащие при параллельных прямых AD, BC и секущей AC.

По условию, ∠DAC = ∠ACB = ∠BAC, поэтому ΔACB равнобедренный, то есть AB = BC, следовательно, ABCD – ромб.

Доказано.

-

Как обозначается биссектриса. И обозначается ли она вообще?

-

Предмет:

Геометрия

-

Автор:

nicolestevenson744

-

Создано:

3 года назад

Ответы

Знаешь ответ? Добавь его сюда!

-

-

Русский язык25 секунд назад

Найдите и исправьте ошибки:

-

Химия5 минут назад

Помогите пожалуйста даю 100 баллов(задание на скрине)

-

Математика10 минут назад

ДОПОМОЖІТЬ ВИРІШИТИ ЛОГАРИФМ

lg ( — 1) + lg ( — 3) = lg (1,5 — 3) -

История10 минут назад

Міні твірна тему: як жили скіфійці: від 1 лиця: ДАЮ 100 БАЛОВ!

-

Алгебра10 минут назад

-1^2+1*1+1^2≥2;

Истина или ложь.

+ расписать как мы к этому дошли поэтапно.

Информация

Посетители, находящиеся в группе Гости, не могут оставлять комментарии к данной публикации.

Вы не можете общаться в чате, вы забанены.

Чтобы общаться в чате подтвердите вашу почту

Отправить письмо повторно

Вопросы без ответа

-

Математика2 часа назад

Помогите пожалуйста !!!!

Вычислите площадь плоской области D , ограниченной заданными линиями. 3x^2-2y=0; 2x-2y+1=0

-

Алгебра4 часа назад

При каком значении a система имеет бесконечно много решений?

{x+y-2z=7

{x+ay+4z=3

{2x+y+az=12a^2

Топ пользователей

-

Fedoseewa27

20458

-

Sofka

7417

-

vov4ik329

5115

-

DobriyChelovek

4631

-

olpopovich

3446

-

dobriykaban

2374

-

zlatikaziatik

2275

-

Udachnick

1867

-

Zowe

1683

-

NikitaAVGN

1210

Войти через Google

или

Запомнить меня

Забыли пароль?

У меня нет аккаунта, я хочу Зарегистрироваться

Выберите язык и регион

Русский

Россия

English

United States

How much to ban the user?

1 hour

1 day

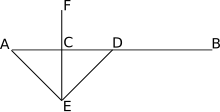

Line DE bisects line AB at D, line EF is a perpendicular bisector of segment AD at C, and line EF is the interior bisector of right angle AED

In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts, usually by a line, which is then called a bisector. The most often considered types of bisectors are the segment bisector (a line that passes through the midpoint of a given segment) and the angle bisector (a line that passes through the apex of an angle, that divides it into two equal angles).

In three-dimensional space, bisection is usually done by a plane, also called the bisector or bisecting plane.

Perpendicular line segment bisector[edit]

Definition[edit]

Perpendicular bisector of a line segment

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a line, which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

The Horizontal intersector of a segment

(D)

The proof follows from

Property (D) is usually used for the construction of a perpendicular bisector:

Construction by straight edge and compass[edit]

Construction by straight edge and compass

In classical geometry, the bisection is a simple compass and straightedge construction, whose possibility depends on the ability to draw arcs of equal radii and different centers:

The segment

Because the construction of the bisector is done without the knowledge of the segment’s midpoint

This construction is in fact used when constructing a line perpendicular to a given line

Equations[edit]

If

(V)

With

(C)

Or explicitly:

(E)

where

Applications[edit]

Perpendicular line segment bisectors were used solving various geometric problems:

- Construction of the center of a Thales’ circle,

- Construction of the center of the Excircle of a triangle,

- Voronoi diagram boundaries consist of segments of such lines or planes.

Perpendicular line segment bisectors in space[edit]

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a plane, which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

Its vector equation is literally the same as in the plane case:

(V)

With

(C3)

Property (D) (see above) is literally true in space, too:

(D) The perpendicular bisector plane of a segment

Angle bisector[edit]

Bisection of an angle using a compass and straightedge

An angle bisector divides the angle into two angles with equal measures. An angle only has one bisector. Each point of an angle bisector is equidistant from the sides of the angle.

The interior or internal bisector of an angle is the line, half-line, or line segment that divides an angle of less than 180° into two equal angles. The exterior or external bisector is the line that divides the supplementary angle (of 180° minus the original angle), formed by one side forming the original angle and the extension of the other side, into two equal angles.[1]

To bisect an angle with straightedge and compass, one draws a circle whose center is the vertex. The circle meets the angle at two points: one on each leg. Using each of these points as a center, draw two circles of the same size. The intersection of the circles (two points) determines a line that is the angle bisector.

The proof of the correctness of this construction is fairly intuitive, relying on the symmetry of the problem. The trisection of an angle (dividing it into three equal parts) cannot be achieved with the compass and ruler alone (this was first proved by Pierre Wantzel).

The internal and external bisectors of an angle are perpendicular. If the angle is formed by the two lines given algebraically as

Triangle[edit]

Concurrencies and collinearities[edit]

The bisectors of two exterior angles and the bisector of the other interior angle are concurrent.[3]: p.149

Three intersection points, each of an external angle bisector with the opposite extended side, are collinear (fall on the same line as each other).[3]: p. 149

Three intersection points, two of them between an interior angle bisector and the opposite side, and the third between the other exterior angle bisector and the opposite side extended, are collinear.[3]: p. 149

Angle bisector theorem[edit]

In this diagram, BD:DC = AB:AC.

The angle bisector theorem is concerned with the relative lengths of the two segments that a triangle’s side is divided into by a line that bisects the opposite angle. It equates their relative lengths to the relative lengths of the other two sides of the triangle.

Lengths[edit]

If the side lengths of a triangle are

or in trigonometric terms,[4]

If the internal bisector of angle A in triangle ABC has length

where b and c are the side lengths opposite vertices B and C; and the side opposite A is divided in the proportion b:c.

If the internal bisectors of angles A, B, and C have lengths

No two non-congruent triangles share the same set of three internal angle bisector lengths.[6][7]

Integer triangles[edit]

There exist integer triangles with a rational angle bisector.

Quadrilateral[edit]

The internal angle bisectors of a convex quadrilateral either form a cyclic quadrilateral (that is, the four intersection points of adjacent angle bisectors are concyclic),[8] or they are concurrent. In the latter case the quadrilateral is a tangential quadrilateral.

Rhombus[edit]

Each diagonal of a rhombus bisects opposite angles.

Ex-tangential quadrilateral[edit]

The excenter of an ex-tangential quadrilateral lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors (supplementary angle bisectors) at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect.

Parabola[edit]

The tangent to a parabola at any point bisects the angle between the line joining the point to the focus and the line from the point and perpendicular to the directrix.

Bisectors of the sides of a polygon[edit]

Triangle[edit]

Medians[edit]

Each of the three medians of a triangle is a line segment going through one vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, so it bisects that side (though not in general perpendicularly). The three medians intersect each other at a point which is called the centroid of the triangle, which is its center of mass if it has uniform density; thus any line through a triangle’s centroid and one of its vertices bisects the opposite side. The centroid is twice as close to the midpoint of any one side as it is to the opposite vertex.

Perpendicular bisectors[edit]

The interior perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is the segment, falling entirely on and inside the triangle, of the line that perpendicularly bisects that side. The three perpendicular bisectors of a triangle’s three sides intersect at the circumcenter (the center of the circle through the three vertices). Thus any line through a triangle’s circumcenter and perpendicular to a side bisects that side.

In an acute triangle the circumcenter divides the interior perpendicular bisectors of the two shortest sides in equal proportions. In an obtuse triangle the two shortest sides’ perpendicular bisectors (extended beyond their opposite triangle sides to the circumcenter) are divided by their respective intersecting triangle sides in equal proportions.[9]: Corollaries 5 and 6

For any triangle the interior perpendicular bisectors are given by

Quadrilateral[edit]

The two bimedians of a convex quadrilateral are the line segments that connect the midpoints of opposite sides, hence each bisecting two sides. The two bimedians and the line segment joining the midpoints of the diagonals are concurrent at a point called the «vertex centroid» and are all bisected by this point.[10]: p.125

The four «maltitudes» of a convex quadrilateral are the perpendiculars to a side through the midpoint of the opposite side, hence bisecting the latter side. If the quadrilateral is cyclic (inscribed in a circle), these maltitudes are concurrent at (all meet at) a common point called the «anticenter».

Brahmagupta’s theorem states that if a cyclic quadrilateral is orthodiagonal (that is, has perpendicular diagonals), then the perpendicular to a side from the point of intersection of the diagonals always bisects the opposite side.

The perpendicular bisector construction forms a quadrilateral from the perpendicular bisectors of the sides of another quadrilateral.

Area bisectors and perimeter bisectors[edit]

Triangle[edit]

There are an infinitude of lines that bisect the area of a triangle. Three of them are the medians of the triangle (which connect the sides’ midpoints with the opposite vertices), and these are concurrent at the triangle’s centroid; indeed, they are the only area bisectors that go through the centroid. Three other area bisectors are parallel to the triangle’s sides; each of these intersects the other two sides so as to divide them into segments with the proportions

The envelope of the infinitude of area bisectors is a deltoid (broadly defined as a figure with three vertices connected by curves that are concave to the exterior of the deltoid, making the interior points a non-convex set).[11] The vertices of the deltoid are at the midpoints of the medians; all points inside the deltoid are on three different area bisectors, while all points outside it are on just one. [1]

The sides of the deltoid are arcs of hyperbolas that are asymptotic to the extended sides of the triangle.[11] The ratio of the area of the envelope of area bisectors to the area of the triangle is invariant for all triangles, and equals

A cleaver of a triangle is a line segment that bisects the perimeter of the triangle and has one endpoint at the midpoint of one of the three sides. The three cleavers concur at (all pass through) the center of the Spieker circle, which is the incircle of the medial triangle. The cleavers are parallel to the angle bisectors.

A splitter of a triangle is a line segment having one endpoint at one of the three vertices of the triangle and bisecting the perimeter. The three splitters concur at the Nagel point of the triangle.

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle’s area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle’s incenter (the center of its incircle). There are either one, two, or three of these for any given triangle. A line through the incenter bisects one of the area or perimeter if and only if it also bisects the other.[12]

Parallelogram[edit]

Any line through the midpoint of a parallelogram bisects the area[11] and the perimeter.

Circle and ellipse[edit]

All area bisectors and perimeter bisectors of a circle or other ellipse go through the center, and any chords through the center bisect the area and perimeter. In the case of a circle they are the diameters of the circle.

Bisectors of diagonals[edit]

Parallelogram[edit]

The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

Quadrilateral[edit]

If a line segment connecting the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisects both diagonals, then this line segment (the Newton Line) is itself bisected by the vertex centroid.

Volume bisectors[edit]

A plane that divides two opposite edges of a tetrahedron in a given ratio also divides the volume of the tetrahedron in the same ratio. Thus any plane containing a bimedian (connector of opposite edges’ midpoints) of a tetrahedron bisects the volume of the tetrahedron[13][14]: pp.89–90

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Exterior Angle Bisector.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Spain, Barry. Analytical Conics, Dover Publications, 2007 (orig. 1957).

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007 (orig. 1929).

- ^ Oxman, Victor. «On the existence of triangles with given lengths of one side and two adjacent angle bisectors», Forum Geometricorum 4, 2004, 215–218. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2004volume4/FG200425.pdf

- ^ Simons, Stuart. Mathematical Gazette 93, March 2009, 115-116.

- ^ Mironescu, P., and Panaitopol, L., «The existence of a triangle with prescribed angle bisector lengths», American Mathematical Monthly 101 (1994): 58–60.

- ^ Oxman, Victor, «A purely geometric proof of the uniqueness of a triangle with prescribed angle bisectors», Forum Geometricorum 8 (2008): 197–200.

- ^

Weisstein, Eric W. «Quadrilateral.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Quadrilateral.html

- ^ a b Mitchell, Douglas W. (2013), «Perpendicular Bisectors of Triangle Sides», Forum Geometricorum 13, 53-59. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2013volume13/FG201307.pdf

- ^ Altshiller-Court, Nathan, College Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007.

- ^ a b c d Dunn, Jas. A.; Pretty, Jas. E. (May 1972). «Halving a triangle». The Mathematical Gazette. 56 (396): 105–108. doi:10.2307/3615256. JSTOR 3615256.

- ^ Kodokostas, Dimitrios, «Triangle Equalizers,» Mathematics Magazine 83, April 2010, pp. 141-146.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Tetrahedron.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Tetrahedron.html

- ^ Altshiller-Court, N. «The tetrahedron.» Ch. 4 in Modern Pure Solid Geometry: Chelsea, 1979.

External links[edit]

- The Angle Bisector at cut-the-knot

- Angle Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Line Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Perpendicular Line Bisector. With interactive applet

- Animated instructions for bisecting an angle and bisecting a line Using a compass and straightedge

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Line Bisector». MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Angle bisector on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Line DE bisects line AB at D, line EF is a perpendicular bisector of segment AD at C, and line EF is the interior bisector of right angle AED

In geometry, bisection is the division of something into two equal or congruent parts, usually by a line, which is then called a bisector. The most often considered types of bisectors are the segment bisector (a line that passes through the midpoint of a given segment) and the angle bisector (a line that passes through the apex of an angle, that divides it into two equal angles).

In three-dimensional space, bisection is usually done by a plane, also called the bisector or bisecting plane.

Perpendicular line segment bisector[edit]

Definition[edit]

Perpendicular bisector of a line segment

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a line, which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

The Horizontal intersector of a segment

(D)

The proof follows from

Property (D) is usually used for the construction of a perpendicular bisector:

Construction by straight edge and compass[edit]

Construction by straight edge and compass

In classical geometry, the bisection is a simple compass and straightedge construction, whose possibility depends on the ability to draw arcs of equal radii and different centers:

The segment

Because the construction of the bisector is done without the knowledge of the segment’s midpoint

This construction is in fact used when constructing a line perpendicular to a given line

Equations[edit]

If

(V)

With

(C)

Or explicitly:

(E)

where

Applications[edit]

Perpendicular line segment bisectors were used solving various geometric problems:

- Construction of the center of a Thales’ circle,

- Construction of the center of the Excircle of a triangle,

- Voronoi diagram boundaries consist of segments of such lines or planes.

Perpendicular line segment bisectors in space[edit]

- The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a plane, which meets the segment at its midpoint perpendicularly.

Its vector equation is literally the same as in the plane case:

(V)

With

(C3)

Property (D) (see above) is literally true in space, too:

(D) The perpendicular bisector plane of a segment

Angle bisector[edit]

Bisection of an angle using a compass and straightedge

An angle bisector divides the angle into two angles with equal measures. An angle only has one bisector. Each point of an angle bisector is equidistant from the sides of the angle.

The interior or internal bisector of an angle is the line, half-line, or line segment that divides an angle of less than 180° into two equal angles. The exterior or external bisector is the line that divides the supplementary angle (of 180° minus the original angle), formed by one side forming the original angle and the extension of the other side, into two equal angles.[1]

To bisect an angle with straightedge and compass, one draws a circle whose center is the vertex. The circle meets the angle at two points: one on each leg. Using each of these points as a center, draw two circles of the same size. The intersection of the circles (two points) determines a line that is the angle bisector.

The proof of the correctness of this construction is fairly intuitive, relying on the symmetry of the problem. The trisection of an angle (dividing it into three equal parts) cannot be achieved with the compass and ruler alone (this was first proved by Pierre Wantzel).

The internal and external bisectors of an angle are perpendicular. If the angle is formed by the two lines given algebraically as

Triangle[edit]

Concurrencies and collinearities[edit]

The bisectors of two exterior angles and the bisector of the other interior angle are concurrent.[3]: p.149

Three intersection points, each of an external angle bisector with the opposite extended side, are collinear (fall on the same line as each other).[3]: p. 149

Three intersection points, two of them between an interior angle bisector and the opposite side, and the third between the other exterior angle bisector and the opposite side extended, are collinear.[3]: p. 149

Angle bisector theorem[edit]

In this diagram, BD:DC = AB:AC.

The angle bisector theorem is concerned with the relative lengths of the two segments that a triangle’s side is divided into by a line that bisects the opposite angle. It equates their relative lengths to the relative lengths of the other two sides of the triangle.

Lengths[edit]

If the side lengths of a triangle are

or in trigonometric terms,[4]

If the internal bisector of angle A in triangle ABC has length

where b and c are the side lengths opposite vertices B and C; and the side opposite A is divided in the proportion b:c.

If the internal bisectors of angles A, B, and C have lengths

No two non-congruent triangles share the same set of three internal angle bisector lengths.[6][7]

Integer triangles[edit]

There exist integer triangles with a rational angle bisector.

Quadrilateral[edit]

The internal angle bisectors of a convex quadrilateral either form a cyclic quadrilateral (that is, the four intersection points of adjacent angle bisectors are concyclic),[8] or they are concurrent. In the latter case the quadrilateral is a tangential quadrilateral.

Rhombus[edit]

Each diagonal of a rhombus bisects opposite angles.

Ex-tangential quadrilateral[edit]

The excenter of an ex-tangential quadrilateral lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors (supplementary angle bisectors) at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect.

Parabola[edit]

The tangent to a parabola at any point bisects the angle between the line joining the point to the focus and the line from the point and perpendicular to the directrix.

Bisectors of the sides of a polygon[edit]

Triangle[edit]

Medians[edit]

Each of the three medians of a triangle is a line segment going through one vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, so it bisects that side (though not in general perpendicularly). The three medians intersect each other at a point which is called the centroid of the triangle, which is its center of mass if it has uniform density; thus any line through a triangle’s centroid and one of its vertices bisects the opposite side. The centroid is twice as close to the midpoint of any one side as it is to the opposite vertex.

Perpendicular bisectors[edit]

The interior perpendicular bisector of a side of a triangle is the segment, falling entirely on and inside the triangle, of the line that perpendicularly bisects that side. The three perpendicular bisectors of a triangle’s three sides intersect at the circumcenter (the center of the circle through the three vertices). Thus any line through a triangle’s circumcenter and perpendicular to a side bisects that side.

In an acute triangle the circumcenter divides the interior perpendicular bisectors of the two shortest sides in equal proportions. In an obtuse triangle the two shortest sides’ perpendicular bisectors (extended beyond their opposite triangle sides to the circumcenter) are divided by their respective intersecting triangle sides in equal proportions.[9]: Corollaries 5 and 6

For any triangle the interior perpendicular bisectors are given by

Quadrilateral[edit]

The two bimedians of a convex quadrilateral are the line segments that connect the midpoints of opposite sides, hence each bisecting two sides. The two bimedians and the line segment joining the midpoints of the diagonals are concurrent at a point called the «vertex centroid» and are all bisected by this point.[10]: p.125

The four «maltitudes» of a convex quadrilateral are the perpendiculars to a side through the midpoint of the opposite side, hence bisecting the latter side. If the quadrilateral is cyclic (inscribed in a circle), these maltitudes are concurrent at (all meet at) a common point called the «anticenter».

Brahmagupta’s theorem states that if a cyclic quadrilateral is orthodiagonal (that is, has perpendicular diagonals), then the perpendicular to a side from the point of intersection of the diagonals always bisects the opposite side.

The perpendicular bisector construction forms a quadrilateral from the perpendicular bisectors of the sides of another quadrilateral.

Area bisectors and perimeter bisectors[edit]

Triangle[edit]

There are an infinitude of lines that bisect the area of a triangle. Three of them are the medians of the triangle (which connect the sides’ midpoints with the opposite vertices), and these are concurrent at the triangle’s centroid; indeed, they are the only area bisectors that go through the centroid. Three other area bisectors are parallel to the triangle’s sides; each of these intersects the other two sides so as to divide them into segments with the proportions

The envelope of the infinitude of area bisectors is a deltoid (broadly defined as a figure with three vertices connected by curves that are concave to the exterior of the deltoid, making the interior points a non-convex set).[11] The vertices of the deltoid are at the midpoints of the medians; all points inside the deltoid are on three different area bisectors, while all points outside it are on just one. [1]

The sides of the deltoid are arcs of hyperbolas that are asymptotic to the extended sides of the triangle.[11] The ratio of the area of the envelope of area bisectors to the area of the triangle is invariant for all triangles, and equals

A cleaver of a triangle is a line segment that bisects the perimeter of the triangle and has one endpoint at the midpoint of one of the three sides. The three cleavers concur at (all pass through) the center of the Spieker circle, which is the incircle of the medial triangle. The cleavers are parallel to the angle bisectors.

A splitter of a triangle is a line segment having one endpoint at one of the three vertices of the triangle and bisecting the perimeter. The three splitters concur at the Nagel point of the triangle.

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle’s area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle’s incenter (the center of its incircle). There are either one, two, or three of these for any given triangle. A line through the incenter bisects one of the area or perimeter if and only if it also bisects the other.[12]

Parallelogram[edit]

Any line through the midpoint of a parallelogram bisects the area[11] and the perimeter.

Circle and ellipse[edit]

All area bisectors and perimeter bisectors of a circle or other ellipse go through the center, and any chords through the center bisect the area and perimeter. In the case of a circle they are the diameters of the circle.

Bisectors of diagonals[edit]

Parallelogram[edit]

The diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other.

Quadrilateral[edit]

If a line segment connecting the diagonals of a quadrilateral bisects both diagonals, then this line segment (the Newton Line) is itself bisected by the vertex centroid.

Volume bisectors[edit]

A plane that divides two opposite edges of a tetrahedron in a given ratio also divides the volume of the tetrahedron in the same ratio. Thus any plane containing a bimedian (connector of opposite edges’ midpoints) of a tetrahedron bisects the volume of the tetrahedron[13][14]: pp.89–90

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Exterior Angle Bisector.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- ^ Spain, Barry. Analytical Conics, Dover Publications, 2007 (orig. 1957).

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007 (orig. 1929).

- ^ Oxman, Victor. «On the existence of triangles with given lengths of one side and two adjacent angle bisectors», Forum Geometricorum 4, 2004, 215–218. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2004volume4/FG200425.pdf

- ^ Simons, Stuart. Mathematical Gazette 93, March 2009, 115-116.

- ^ Mironescu, P., and Panaitopol, L., «The existence of a triangle with prescribed angle bisector lengths», American Mathematical Monthly 101 (1994): 58–60.

- ^ Oxman, Victor, «A purely geometric proof of the uniqueness of a triangle with prescribed angle bisectors», Forum Geometricorum 8 (2008): 197–200.

- ^

Weisstein, Eric W. «Quadrilateral.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Quadrilateral.html

- ^ a b Mitchell, Douglas W. (2013), «Perpendicular Bisectors of Triangle Sides», Forum Geometricorum 13, 53-59. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2013volume13/FG201307.pdf

- ^ Altshiller-Court, Nathan, College Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007.

- ^ a b c d Dunn, Jas. A.; Pretty, Jas. E. (May 1972). «Halving a triangle». The Mathematical Gazette. 56 (396): 105–108. doi:10.2307/3615256. JSTOR 3615256.

- ^ Kodokostas, Dimitrios, «Triangle Equalizers,» Mathematics Magazine 83, April 2010, pp. 141-146.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Tetrahedron.» From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Tetrahedron.html

- ^ Altshiller-Court, N. «The tetrahedron.» Ch. 4 in Modern Pure Solid Geometry: Chelsea, 1979.

External links[edit]

- The Angle Bisector at cut-the-knot

- Angle Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Line Bisector definition. Math Open Reference With interactive applet

- Perpendicular Line Bisector. With interactive applet

- Animated instructions for bisecting an angle and bisecting a line Using a compass and straightedge

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Line Bisector». MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Angle bisector on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Биссектриса (от лат. bi- «двойное», и sectio «разрезание») угла — луч с началом в вершине угла, делящий угол на два равных угла[1]. Биссектриса угла — геометрическое место точек внутри угла, равноудалённых от сторон угла.

В треугольнике под биссектрисой угла может также пониматься отрезок биссектрисы этого угла до её пересечения с противолежащей стороной треугольника.

Свойства

- Теорема о биссектрисе: Биссектриса внутреннего угла треугольника делит противоположную сторону в отношении, равном отношению двух прилежащих сторон

- Биссектрисы внутренних углов треугольника пересекаются в одной точке — инцентре — центре вписанной в этот треугольник окружности.

- Биссектрисы одного внутреннего и двух внешних углов треугольника пересекаются в одной точке. Эта точка — центр одной из трёх вневписанных окружностей этого треугольника.

- Основания биссектрис двух внутренних и одного внешнего углов треугольника лежат на одной прямой, если биссектриса внешнего угла не параллельна противоположной стороне треугольника.

- Если биссектрисы внешних углов треугольника не параллельны противоположным сторонам, то их основания лежат на одной прямой.

- Если в треугольнике две биссектрисы равны, то треугольник — равнобедренный (теорема Штейнера — Лемуса).

- Построение треугольника по трем заданным биссектрисам с помощью циркуля и линейки невозможно,[2] причём даже при наличии трисектора.[3]

Длина биссектрис в треугольнике

Для выведения нижеприведённых формул можно воспользоваться теоремой Стюарта.

где:

Мнемоническое правило

Биссектриса — это крыса, которая бегает по углам и делит угол пополам[4].

Облегчает запоминание формулировки. Чаще всего употребляется детьми.

Примечания

- ↑ Биссектриса // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: В 86 томах (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- ↑ Кто и когда доказал невозможность построения треугольника по трем биссектрисам?. Дистанционный консультационный пункт по математике МЦНМО.

- ↑ Можно ли построить треугольник по трем биссектрисам, если кроме циркуля и линейки разрешается использовать трисектор. Дистанционный консультационный пункт по математике МЦНМО.

- ↑ Учебные трудности пятиклассников

Литература

| Биссектриса на Викискладе? |

- Коган Б. Ю. Приложение механики к геометрии. М.: Наука. 1965. 56 с.

- Понарин Я. П. Элементарная геометрия. В 2 тт. — М.: МЦНМО, 2004. — С. 30-31. — ISBN 5-94057-170-0

Биссектриса — это луч разрезающий угол пополам, а также отрезок в треугольнике обладающий рядом свойств

Здравствуйте, уважаемые читатели блога KtoNaNovenkogo.ru. Сегодня мы поговорим о таком термине, как БИССЕКТРИСА.

Это понятие широко применяется в геометрии. И каждый школьник в России знакомится с ним уже в 5 классе. А после эта величина часто используется для решения различных задач.

Биссектриса — это…

Итак,

Биссектриса – это луч, который выходит из вершины треугольника и делит ее ровно на две части.

Также под биссектрисой принято понимать и длину отрезка (что это?), который начинается в вершине треугольника, а заканчивается на противоположной от этой вершины стороне.

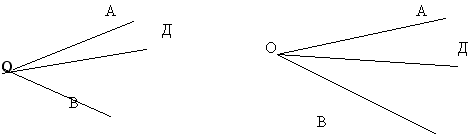

Есть еще понятие «биссектриса угла», которая является лучом и точно так же делит угол (любой, не обязательно треугольника) пополам:

Само понятие БИССЕКТРИСА пришло к нам из латинского языка. И название это весьма говорящее. Оно состоит из двух слов – «bi» означает «двойное, пара», а «sectio» можно дословно перевести, как «разрезать, поделить».

Вот и получается, что само слово БИССЕКТРИСА – это «разрезание пополам», что собственно и отражается в определении термина, который мы только что привели.

А сейчас задачка на закрепление материала. Посмотрите на эти рисунки и скажите, на каком изображена биссектриса. Подумали? Правильно, на втором.

На первом луч, выходящий из угла АОВ, явно не делит его пополам. На втором это соотношение углов более очевидно, а потому можно предположить, что луч ОД является БИССЕКТРИСОЙ. Хотя, конечно, на сто процентов это утверждать сложно.

Для более точного определения используют специальные инструменты. Например, транспортир. Это такой инструмент в виде полусферы из металла или пластмассы. Вот как он выглядит:

Хотя есть еще вот такие варианты:

Наверняка у каждого такие были в школе. И пользоваться ими весьма просто. Надо только ровненько совместить основание транспортира (прямоугольная линейка) с основанием треугольника, а после на полусфере отметить значение, которое соответствует размеру угла.

И точно по такой же схеме можно поступить наоборот – имея транспортир, начертить угол необходимого размера. Чаще всего – от 0 до 180 градусов. Но на втором рисунке у нас транспортир, который помогает начертить градусы от 0 до 360.

Количество биссектрис в треугольнике

Но вернемся к нашей главной теме. И ответим на вопрос – сколько БИССЕКТРИС есть в треугольнике?

Ответ в общем-то логичен, и он заложен в самом названии нашей геометрической фигуры. Треугольник – три угла. А соответственно, и биссектрис в нем будет тоже три – по одной на каждую вершину.

Снова посмотрим на наши рисунки. В данном случае наглядно видно, что у треугольника АВС (именно так в геометрии обозначается эта фигура – по наименованию ее вершин) три БИССЕКТРИСЫ. Это отрезки AD, BE и CF.

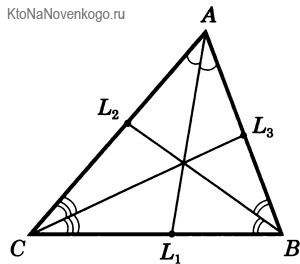

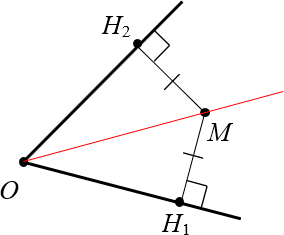

На чертежах БИССЕКТРИСЫ обозначатся следующим образом. Видите одинарные выгнутые черточки между отрезками АС /AL1 и АВ/AL1? Так обозначаются углы. А то, что они оба обозначены одинаковыми черточками, говорит о том, что углы равны. А значит, отрезок AL1 является БИССЕКТРИСОЙ.

То же самое относится и к углам между АВ/DL2 и ВС/BL2. Они обозначены одинаковыми двойными черточками. А значит, отрезок BL2 – биссектриса. А углы АС/CL3 и ВС/CL3 обозначены тройными черточками. Соответственно, это показывает, что отрезок CL3 также является биссектрисой.

Пересечение биссектрис треугольника

Как можно было заметить по приведенным выше рисункам, у биссектрис треугольника есть одно важное свойство. А именно:

Биссектрисы треугольника всегда пересекаются в одной точке, называемой инцентром!

Это правило является аксиомой (что это такое?) и не допускает никаких исключений. Другими словами, вот такого быть не может:

Если вы видите такую картину, то перед вами точно не БИССЕКТРИСЫ. Во всяком случае, минимум один отрезок таковой не является. А может и все три.

А есть еще один интересный факт, связанный с пересечением биссектрис треугольника.

Центр пересечения биссектрис в треугольнике является центром окружности, который списан в эту фигуру.

Это свойство биссектрис на самом деле не только выглядит интересно на чертежах. Оно часто помогает в решение сложных задач.

Свойство основания биссектрисы

У каждой БИССЕКТРИСЫ есть основание. Так называют точку пересечения со стороной треугольника. Например, в нашем случае это будет точка К.

И с этим основанием связана одна весьма интересная теорема. Она гласит, что

Биссектриса треугольника делит противоположную сторону, то есть точкой основания, на два отрезка. И их отношение равно отношению двух прилежащих сторон.

Звучит несколько тяжеловато, но на деле выглядит весьма просто. Отношение отрезков на основании биссектрисы – это ВК/КС. А отношение прилежащих сторон – это АВ/АС. И получается, что в нашем случае теорема выглядит вот так:

ВК/КС = АВ/АС

Интересно, что для данной теоремы будет справедливо и другое утверждение:

ВК/АВ = КС/АС

Ну, как часто бывает в математике – это правило работает и в обратном направлении. То есть, если вы знаете длины все сторон и их соотношения равны, то можно сделать вывод, что перед нами БИССЕКТРИСА, А соответственно, будет проще рассчитать размер угла треугольника.

Биссектриса равнобедренного треугольника

Для начала напомним, что такое равнобедренный треугольник.

Это такой треугольник, у которого две стороны абсолютно равны (то есть имеет равные «бедра»).

Так вот в таком треугольнике БИССЕКТРИСА имеет весьма интересные свойства.

Она одновременно является еще и медианой (что это?), и высотой.

Эти понятия нам также знакомы по школьному курсу. Но если кто забыл, мы обязательно напомним:

- Высота – линия, которая выходит из вершины треугольника и опускается на противоположную сторону под прямым углом.

- Медиана – линия, которая выходит из вершины треугольника, и делит противоположную сторону на две ровные части.

А в равностороннем треугольнике или как его еще называют правильном (у которого все стороны и все углы равны) все три биссектрисы являются высотами и медианами. И плюс ко всему, их длины равны.

Вот и все, что нужно знать о таком понятии, как БИССЕКТРИСА. До новых встреч на страницах нашего блога.

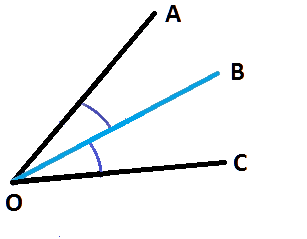

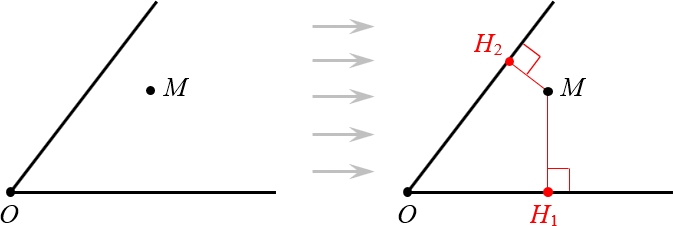

Напомним, что углом называют два луча, которые исходят из одной точки O. Для конкретики будем называть их лучами OA и OC. Из точки можно провести бесчисленное количество лучей, но среди них есть один особенный, именуемый биссектрисой угла.

Понятие биссектрисы угла

Определения 1 — 2

Биссектрисой угла в геометрии называют луч, начинающийся в его вершине и делящий указанный угол на две равные части (сектора). Сказанное хорошо видно на рисунке ниже. Для указания равенства двух углов, их отмечают одинаковым количеством дуг.

Определить биссектрису угла можно и по-другому, воспользовавшись одним из основных её свойств – все точки биссектрисы угла всегда, во всех случаях, равноудалены от сторон того угла, в котором она проведена.

Биссектрисой угла принято считать геометрическое место точек плоскости, находящихся на равном удалении от его сторон.

Свойства точки биссектрисы угла

Из определения 2 можно сделать два вывода:

- Любая из точек биссектрисы угла находится на одинаковом удалении от его сторон;

- Если точка имеет равные расстояния от двух сторон угла, то она непременно лежит среди точек его биссектрисы и принадлежит к их множеству.

Докажем эти два утверждения.

Определения 3 — 4

Расстоянием от точки M до проходящей в их общей плоскости прямой принято считать длину перпендикуляра, проведённого к M.

Т. к. луч является частью прямой, а угол создан двумя лучами, из определения выше очень легко понять, что является расстоянием от точки до сторон угла.

Расстоянием от точки до сторон угла называют длину перпендикуляров к лучам, которые образуют указанный угол.

Доказательство первого утверждения – расстояния от биссектрисы до сторон угла между собой всегда равны.

Проведём из М перпендикуляры к сторонам угла:

Так перед нами оказалось два прямоугольных треугольника, у которых имеется общая гипотенуза и равные углы.

- Угол MOH1 равен углу MOH2.

- Углы MH1O и MH2O являются прямыми. Это следует из построения.

- Углы OMH1 и OMH2 тоже прямые, ведь сумма углов в любом прямоугольном треугольнике за вычетом прямого всегда равняется 90 градусам.

Из сказанного следует, что треугольники равны по одной их стороне и прилежащим углам, а значит MH1 = MH2. Это нам и требовалось доказать.

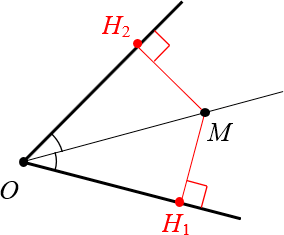

Доказательство второго утверждения – если расстояния до M численно одинаковы, то она принадлежит биссектрисе.

Мы опять имеем прямоугольные треугольники. У них, как видно из рисунка, имеется общая гипотенуза OM. Стороны MH1 и MH2 одинаковы по условию. Оставшиеся катеты тоже равны. Их легко вычислить, как OH12 = OH22= OM2 – MH12. Получается, что треугольники равны по всем трём сторонам. Это значит, что равны и углы. Доказательство завершено.

Нет времени решать самому?

Наши эксперты помогут!

Некоторые свойства биссектрисы угла

Точка, в которой сходятся биссектрис углов треугольника представляет собой центр вписанной в эту геометрическую фигуру окружности.

Угол между двумя биссектрисами смежных углов всегда равняется 90 градусам.