Liquid and gas bromine inside transparent cube |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bromine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (BROH-meen, -min, -myne) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | reddish-brown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Br) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

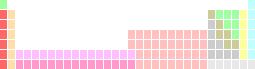

| Bromine in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 17 (halogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

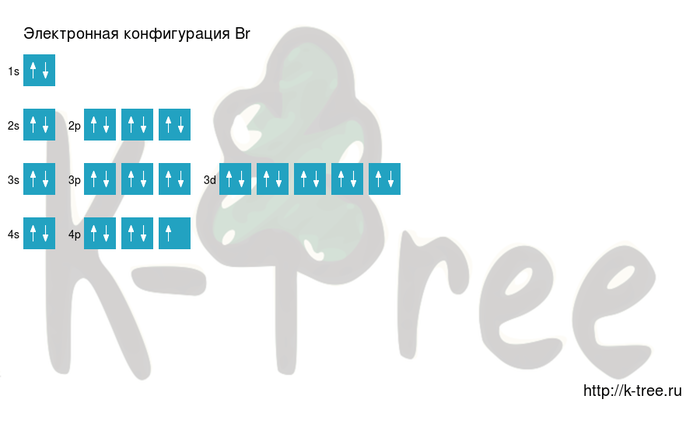

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

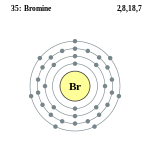

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | liquid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (Br2) 265.8 K (−7.2 °C, 19 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | (Br2) 332.0 K (58.8 °C, 137.8 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | Br2, liquid: 3.1028 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 265.90 K, 5.8 kPa[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 588 K, 10.34 MPa[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (Br2) 10.571 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | (Br2) 29.96 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (Br2) 75.69 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, +1, 2,[3] +3, +4, +5, +7 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.96 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 120 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 120±3 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 185 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of bromine |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | orthorhombic

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 206 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.122 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 7.8×1010 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −56.4×10−6 cm3/mol[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7726-95-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Antoine Jérôme Balard and Carl Jacob Löwig (1825) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of bromine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table (halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine. Isolated independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig (in 1825) and Antoine Jérôme Balard (in 1826), its name was derived from the Ancient Greek βρῶμος (bromos) meaning «stench», referring to its sharp and pungent smell.

Elemental bromine is very reactive and thus does not occur as a native element in nature but it occurs in colourless soluble crystalline mineral halide salts, analogous to table salt. In fact, bromine and all the halogens are so reactive that they form bonds in pairs—never in single atoms. While it is rather rare in the Earth’s crust, the high solubility of the bromide ion (Br−) has caused its accumulation in the oceans. Commercially the element is easily extracted from brine evaporation ponds, mostly in the United States and Israel. The mass of bromine in the oceans is about one three-hundredth that of chlorine.

At standard conditions for temperature and pressure it is a liquid; the only other element that is liquid under these conditions is mercury. At high temperatures, organobromine compounds readily dissociate to yield free bromine atoms, a process that stops free radical chemical chain reactions. This effect makes organobromine compounds useful as fire retardants, and more than half the bromine produced worldwide each year is put to this purpose. The same property causes ultraviolet sunlight to dissociate volatile organobromine compounds in the atmosphere to yield free bromine atoms, causing ozone depletion. As a result, many organobromine compounds—such as the pesticide methyl bromide—are no longer used. Bromine compounds are still used in well drilling fluids, in photographic film, and as an intermediate in the manufacture of organic chemicals.

Large amounts of bromide salts are toxic from the action of soluble bromide ions, causing bromism. However, a clear biological role for bromide ions and hypobromous acid has recently been elucidated, and it now appears that bromine is an essential trace element in humans. The role of biological organobromine compounds in sea life such as algae has been known for much longer. As a pharmaceutical, the simple bromide ion (Br−) has inhibitory effects on the central nervous system, and bromide salts were once a major medical sedative, before replacement by shorter-acting drugs. They retain niche uses as antiepileptics.

History[edit]

Bromine was discovered independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig[6] and Antoine Balard,[7][8] in 1825 and 1826, respectively.[9]

Löwig isolated bromine from a mineral water spring from his hometown Bad Kreuznach in 1825. Löwig used a solution of the mineral salt saturated with chlorine and extracted the bromine with diethyl ether. After evaporation of the ether, a brown liquid remained. With this liquid as a sample of his work he applied for a position in the laboratory of Leopold Gmelin in Heidelberg. The publication of the results was delayed and Balard published his results first.[10]

Balard found bromine chemicals in the ash of seaweed from the salt marshes of Montpellier. The seaweed was used to produce iodine, but also contained bromine. Balard distilled the bromine from a solution of seaweed ash saturated with chlorine. The properties of the resulting substance were intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine; thus he tried to prove that the substance was iodine monochloride (ICl), but after failing to do so he was sure that he had found a new element and named it muride, derived from the Latin word muria («brine»).[8][11][12]

After the French chemists Louis Nicolas Vauquelin, Louis Jacques Thénard, and Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac approved the experiments of the young pharmacist Balard, the results were presented at a lecture of the Académie des Sciences and published in Annales de Chimie et Physique.[7] In his publication, Balard stated that he changed the name from muride to brôme on the proposal of M. Anglada. The name brôme (bromine) derives from the Greek βρῶμος (brômos, «stench»).[7][13][11][14] Other sources claim that the French chemist and physicist Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac suggested the name brôme for the characteristic smell of the vapors.[15][16] Bromine was not produced in large quantities until 1858, when the discovery of salt deposits in Stassfurt enabled its production as a by-product of potash.[17]

Apart from some minor medical applications, the first commercial use was the daguerreotype. In 1840, bromine was discovered to have some advantages over the previously used iodine vapor to create the light sensitive silver halide layer in daguerreotypy.[18]

Potassium bromide and sodium bromide were used as anticonvulsants and sedatives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were gradually superseded by chloral hydrate and then by the barbiturates.[19] In the early years of the First World War, bromine compounds such as xylyl bromide were used as poison gas.[20]

Properties[edit]

Bromine is the third halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to those of fluorine, chlorine, and iodine, and tend to be intermediate between those of the two neighbouring halogens, chlorine, and iodine. Bromine has the electron configuration [Ar]4s23d104p5, with the seven electrons in the fourth and outermost shell acting as its valence electrons. Like all halogens, it is thus one electron short of a full octet, and is hence a strong oxidising agent, reacting with many elements in order to complete its outer shell.[21] Corresponding to periodic trends, it is intermediate in electronegativity between chlorine and iodine (F: 3.98, Cl: 3.16, Br: 2.96, I: 2.66), and is less reactive than chlorine and more reactive than iodine. It is also a weaker oxidising agent than chlorine, but a stronger one than iodine. Conversely, the bromide ion is a weaker reducing agent than iodide, but a stronger one than chloride.[21] These similarities led to chlorine, bromine, and iodine together being classified as one of the original triads of Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, whose work foreshadowed the periodic law for chemical elements.[22][23] It is intermediate in atomic radius between chlorine and iodine, and this leads to many of its atomic properties being similarly intermediate in value between chlorine and iodine, such as first ionisation energy, electron affinity, enthalpy of dissociation of the X2 molecule (X = Cl, Br, I), ionic radius, and X–X bond length.[21] The volatility of bromine accentuates its very penetrating, choking, and unpleasant odour.[24]

All four stable halogens experience intermolecular van der Waals forces of attraction, and their strength increases together with the number of electrons among all homonuclear diatomic halogen molecules. Thus, the melting and boiling points of bromine are intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine. As a result of the increasing molecular weight of the halogens down the group, the density and heats of fusion and vaporisation of bromine are again intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine, although all their heats of vaporisation are fairly low (leading to high volatility) thanks to their diatomic molecular structure.[21] The halogens darken in colour as the group is descended: fluorine is a very pale yellow gas, chlorine is greenish-yellow, and bromine is a reddish-brown volatile liquid that melts at −7.2 °C and boils at 58.8 °C. (Iodine is a shiny black solid.) This trend occurs because the wavelengths of visible light absorbed by the halogens increase down the group.[21] Specifically, the colour of a halogen, such as bromine, results from the electron transition between the highest occupied antibonding πg molecular orbital and the lowest vacant antibonding σu molecular orbital.[25] The colour fades at low temperatures so that solid bromine at −195 °C is pale yellow.[21]

Like solid chlorine and iodine, solid bromine crystallises in the orthorhombic crystal system, in a layered arrangement of Br2 molecules. The Br–Br distance is 227 pm (close to the gaseous Br–Br distance of 228 pm) and the Br···Br distance between molecules is 331 pm within a layer and 399 pm between layers (compare the van der Waals radius of bromine, 195 pm). This structure means that bromine is a very poor conductor of electricity, with a conductivity of around 5 × 10−13 Ω−1 cm−1 just below the melting point, although this is higher than the essentially undetectable conductivity of chlorine.[21]

At a pressure of 55 GPa (roughly 540,000 times atmospheric pressure) bromine undergoes an insulator-to-metal transition. At 75 GPa it changes to a face-centered orthorhombic structure. At 100 GPa it changes to a body centered orthorhombic monatomic form.[26]

Isotopes[edit]

Bromine has two stable isotopes, 79Br and 81Br. These are its only two natural isotopes, with 79Br making up 51% of natural bromine and 81Br making up the remaining 49%. Both have nuclear spin 3/2− and thus may be used for nuclear magnetic resonance, although 81Br is more favourable. The relatively 1:1 distribution of the two isotopes in nature is helpful in identification of bromine containing compounds using mass spectroscopy. Other bromine isotopes are all radioactive, with half-lives too short to occur in nature. Of these, the most important are 80Br (t1/2 = 17.7 min), 80mBr (t1/2 = 4.421 h), and 82Br (t1/2 = 35.28 h), which may be produced from the neutron activation of natural bromine.[21] The most stable bromine radioisotope is 77Br (t1/2 = 57.04 h). The primary decay mode of isotopes lighter than 79Br is electron capture to isotopes of selenium; that of isotopes heavier than 81Br is beta decay to isotopes of krypton; and 80Br may decay by either mode to stable 80Se or 80Kr.[27]

Chemistry and compounds[edit]

| X | XX | HX | BX3 | AlX3 | CX4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 159 | 574 | 645 | 582 | 456 |

| Cl | 243 | 428 | 444 | 427 | 327 |

| Br | 193 | 363 | 368 | 360 | 272 |

| I | 151 | 294 | 272 | 285 | 239 |

Bromine is intermediate in reactivity between chlorine and iodine, and is one of the most reactive elements. Bond energies to bromine tend to be lower than those to chlorine but higher than those to iodine, and bromine is a weaker oxidising agent than chlorine but a stronger one than iodine. This can be seen from the standard electrode potentials of the X2/X− couples (F, +2.866 V; Cl, +1.395 V; Br, +1.087 V; I, +0.615 V; At, approximately +0.3 V). Bromination often leads to higher oxidation states than iodination but lower or equal oxidation states to chlorination. Bromine tends to react with compounds including M–M, M–H, or M–C bonds to form M–Br bonds.[25]

Hydrogen bromide[edit]

The simplest compound of bromine is hydrogen bromide, HBr. It is mainly used in the production of inorganic bromides and alkyl bromides, and as a catalyst for many reactions in organic chemistry. Industrially, it is mainly produced by the reaction of hydrogen gas with bromine gas at 200–400 °C with a platinum catalyst. However, reduction of bromine with red phosphorus is a more practical way to produce hydrogen bromide in the laboratory:[28]

- 2 P + 6 H2O + 3 Br2 → 6 HBr + 2 H3PO3

- H3PO3 + H2O + Br2 → 2 HBr + H3PO4

At room temperature, hydrogen bromide is a colourless gas, like all the hydrogen halides apart from hydrogen fluoride, since hydrogen cannot form strong hydrogen bonds to the large and only mildly electronegative bromine atom; however, weak hydrogen bonding is present in solid crystalline hydrogen bromide at low temperatures, similar to the hydrogen fluoride structure, before disorder begins to prevail as the temperature is raised.[28] Aqueous hydrogen bromide is known as hydrobromic acid, which is a strong acid (pKa = −9) because the hydrogen bonds to bromine are too weak to inhibit dissociation. The HBr/H2O system also involves many hydrates HBr·nH2O for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6, which are essentially salts of bromine anions and hydronium cations. Hydrobromic acid forms an azeotrope with boiling point 124.3 °C at 47.63 g HBr per 100 g solution; thus hydrobromic acid cannot be concentrated beyond this point by distillation.[29]

Unlike hydrogen fluoride, anhydrous liquid hydrogen bromide is difficult to work with as a solvent, because its boiling point is low, it has a small liquid range, its dielectric constant is low and it does not dissociate appreciably into H2Br+ and HBr−

2 ions – the latter, in any case, are much less stable than the bifluoride ions (HF−

2) due to the very weak hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and bromine, though its salts with very large and weakly polarising cations such as Cs+ and NR+

4 (R = Me, Et, Bun) may still be isolated. Anhydrous hydrogen bromide is a poor solvent, only able to dissolve small molecular compounds such as nitrosyl chloride and phenol, or salts with very low lattice energies such as tetraalkylammonium halides.[29]

Other binary bromides[edit]

Nearly all elements in the periodic table form binary bromides. The exceptions are decidedly in the minority and stem in each case from one of three causes: extreme inertness and reluctance to participate in chemical reactions (the noble gases, with the exception of xenon in the very unstable XeBr2); extreme nuclear instability hampering chemical investigation before decay and transmutation (many of the heaviest elements beyond bismuth); and having an electronegativity higher than bromine’s (oxygen, nitrogen, fluorine, and chlorine), so that the resultant binary compounds are formally not bromides but rather oxides, nitrides, fluorides, or chlorides of bromine. (Nonetheless, nitrogen tribromide is named as a bromide as it is analogous to the other nitrogen trihalides.)[30]

Bromination of metals with Br2 tends to yield lower oxidation states than chlorination with Cl2 when a variety of oxidation states is available. Bromides can be made by reaction of an element or its oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate with hydrobromic acid, and then dehydrated by mildly high temperatures combined with either low pressure or anhydrous hydrogen bromide gas. These methods work best when the bromide product is stable to hydrolysis; otherwise, the possibilities include high-temperature oxidative bromination of the element with bromine or hydrogen bromide, high-temperature bromination of a metal oxide or other halide by bromine, a volatile metal bromide, carbon tetrabromide, or an organic bromide. For example, niobium(V) oxide reacts with carbon tetrabromide at 370 °C to form niobium(V) bromide.[30] Another method is halogen exchange in the presence of excess «halogenating reagent», for example:[30]

- FeCl3 + BBr3 (excess) → FeBr3 + BCl3

When a lower bromide is wanted, either a higher halide may be reduced using hydrogen or a metal as a reducing agent, or thermal decomposition or disproportionation may be used, as follows:[30]

- 3 WBr5 + Al thermal gradient→475 °C → 240 °C 3 WBr4 + AlBr3

- EuBr3 + 1/2 H2 → EuBr2 + HBr

- 2 TaBr4 500 °C→ TaBr3 + TaBr5

Most metal bromides with the metal in low oxidation states (+1 to +3) are ionic. Nonmetals tend to form covalent molecular bromides, as do metals in high oxidation states from +3 and above. Both ionic and covalent bromides are known for metals in oxidation state +3 (e.g. scandium bromide is mostly ionic, but aluminium bromide is not). Silver bromide is very insoluble in water and is thus often used as a qualitative test for bromine.[30]

Bromine halides[edit]

The halogens form many binary, diamagnetic interhalogen compounds with stoichiometries XY, XY3, XY5, and XY7 (where X is heavier than Y), and bromine is no exception. Bromine forms a monofluoride and monochloride, as well as a trifluoride and pentafluoride. Some cationic and anionic derivatives are also characterised, such as BrF−

2, BrCl−

2, BrF+

2, BrF+

4, and BrF+

6. Apart from these, some pseudohalides are also known, such as cyanogen bromide (BrCN), bromine thiocyanate (BrSCN), and bromine azide (BrN3).[31]

The pale-brown bromine monofluoride (BrF) is unstable at room temperature, disproportionating quickly and irreversibly into bromine, bromine trifluoride, and bromine pentafluoride. It thus cannot be obtained pure. It may be synthesised by the direct reaction of the elements, or by the comproportionation of bromine and bromine trifluoride at high temperatures.[31] Bromine monochloride (BrCl), a red-brown gas, quite readily dissociates reversibly into bromine and chlorine at room temperature and thus also cannot be obtained pure, though it can be made by the reversible direct reaction of its elements in the gas phase or in carbon tetrachloride.[30] Bromine monofluoride in ethanol readily leads to the monobromination of the aromatic compounds PhX (para-bromination occurs for X = Me, But, OMe, Br; meta-bromination occurs for the deactivating X = –CO2Et, –CHO, –NO2); this is due to heterolytic fission of the Br–F bond, leading to rapid electrophilic bromination by Br+.[30]

At room temperature, bromine trifluoride (BrF3) is a straw-coloured liquid. It may be formed by directly fluorinating bromine at room temperature and is purified through distillation. It reacts violently with water and explodes on contact with flammable materials, but is a less powerful fluorinating reagent than chlorine trifluoride. It reacts vigorously with boron, carbon, silicon, arsenic, antimony, iodine, and sulfur to give fluorides, and will also convert most metals and many metal compounds to fluorides; as such, it is used to oxidise uranium to uranium hexafluoride in the nuclear power industry. Refractory oxides tend to be only partially fluorinated, but here the derivatives KBrF4 and BrF2SbF6 remain reactive. Bromine trifluoride is a useful nonaqueous ionising solvent, since it readily dissociates to form BrF+

2 and BrF−

4 and thus conducts electricity.[32]

Bromine pentafluoride (BrF5) was first synthesised in 1930. It is produced on a large scale by direct reaction of bromine with excess fluorine at temperatures higher than 150 °C, and on a small scale by the fluorination of potassium bromide at 25 °C. It also reacts violently with water and is a very strong fluorinating agent, although chlorine trifluoride is still stronger.[33]

Polybromine compounds[edit]

Although dibromine is a strong oxidising agent with a high first ionisation energy, very strong oxidisers such as peroxydisulfuryl fluoride (S2O6F2) can oxidise it to form the cherry-red Br+

2 cation. A few other bromine cations are known, namely the brown Br+

3 and dark brown Br+

5.[34] The tribromide anion, Br−

3, has also been characterised; it is analogous to triiodide.[31]

Bromine oxides and oxoacids[edit]

| E°(couple) | a(H+) = 1 (acid) |

E°(couple) | a(OH−) = 1 (base) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Br2/Br− | +1.052 | Br2/Br− | +1.065 |

| HOBr/Br− | +1.341 | BrO−/Br− | +0.760 |

| BrO− 3/Br− |

+1.399 | BrO− 3/Br− |

+0.584 |

| HOBr/Br2 | +1.604 | BrO−/Br2 | +0.455 |

| BrO− 3/Br2 |

+1.478 | BrO− 3/Br2 |

+0.485 |

| BrO− 3/HOBr |

+1.447 | BrO− 3/BrO− |

+0.492 |

| BrO− 4/BrO− 3 |

+1.853 | BrO− 4/BrO− 3 |

+1.025 |

Bromine oxides are not as well-characterised as chlorine oxides or iodine oxides, as they are all fairly unstable: it was once thought that they could not exist at all. Dibromine monoxide is a dark-brown solid which, while reasonably stable at −60 °C, decomposes at its melting point of −17.5 °C; it is useful in bromination reactions[36] and may be made from the low-temperature decomposition of bromine dioxide in a vacuum. It oxidises iodine to iodine pentoxide and benzene to 1,4-benzoquinone; in alkaline solutions, it gives the hypobromite anion.[37]

So-called «bromine dioxide», a pale yellow crystalline solid, may be better formulated as bromine perbromate, BrOBrO3. It is thermally unstable above −40 °C, violently decomposing to its elements at 0 °C. Dibromine trioxide, syn-BrOBrO2, is also known; it is the anhydride of hypobromous acid and bromic acid. It is an orange crystalline solid which decomposes above −40 °C; if heated too rapidly, it explodes around 0 °C. A few other unstable radical oxides are also known, as are some poorly characterised oxides, such as dibromine pentoxide, tribromine octoxide, and bromine trioxide.[37]

The four oxoacids, hypobromous acid (HOBr), bromous acid (HOBrO), bromic acid (HOBrO2), and perbromic acid (HOBrO3), are better studied due to their greater stability, though they are only so in aqueous solution. When bromine dissolves in aqueous solution, the following reactions occur:[35]

-

Br2 + H2O ⇌ HOBr + H+ + Br− Kac = 7.2 × 10−9 mol2 l−2 Br2 + 2 OH− ⇌ OBr− + H2O + Br− Kalk = 2 × 108 mol−1 l

Hypobromous acid is unstable to disproportionation. The hypobromite ions thus formed disproportionate readily to give bromide and bromate:[35]

-

3 BrO− ⇌ 2 Br− + BrO−

3K = 1015

Bromous acids and bromites are very unstable, although the strontium and barium bromites are known.[38] More important are the bromates, which are prepared on a small scale by oxidation of bromide by aqueous hypochlorite, and are strong oxidising agents. Unlike chlorates, which very slowly disproportionate to chloride and perchlorate, the bromate anion is stable to disproportionation in both acidic and aqueous solutions. Bromic acid is a strong acid. Bromides and bromates may comproportionate to bromine as follows:[38]

- BrO−

3 + 5 Br− + 6 H+ → 3 Br2 + 3 H2O

There were many failed attempts to obtain perbromates and perbromic acid, leading to some rationalisations as to why they should not exist, until 1968 when the anion was first synthesised from the radioactive beta decay of unstable 83

SeO2−

4. Today, perbromates are produced by the oxidation of alkaline bromate solutions by fluorine gas. Excess bromate and fluoride are precipitated as silver bromate and calcium fluoride, and the perbromic acid solution may be purified. The perbromate ion is fairly inert at room temperature but is thermodynamically extremely oxidising, with extremely strong oxidising agents needed to produce it, such as fluorine or xenon difluoride. The Br–O bond in BrO−

4 is fairly weak, which corresponds to the general reluctance of the 4p elements arsenic, selenium, and bromine to attain their group oxidation state, as they come after the scandide contraction characterised by the poor shielding afforded by the radial-nodeless 3d orbitals.[39]

Organobromine compounds[edit]

Like the other carbon–halogen bonds, the C–Br bond is a common functional group that forms part of core organic chemistry. Formally, compounds with this functional group may be considered organic derivatives of the bromide anion. Due to the difference of electronegativity between bromine (2.96) and carbon (2.55), the carbon atom in a C–Br bond is electron-deficient and thus electrophilic. The reactivity of organobromine compounds resembles but is intermediate between the reactivity of organochlorine and organoiodine compounds. For many applications, organobromides represent a compromise of reactivity and cost.[40]

Organobromides are typically produced by additive or substitutive bromination of other organic precursors. Bromine itself can be used, but due to its toxicity and volatility, safer brominating reagents are normally used, such as N-bromosuccinimide. The principal reactions for organobromides include dehydrobromination, Grignard reactions, reductive coupling, and nucleophilic substitution.[40]

Organobromides are the most common organohalides in nature, even though the concentration of bromide is only 0.3% of that for chloride in sea water, because of the easy oxidation of bromide to the equivalent of Br+, a potent electrophile. The enzyme bromoperoxidase catalyzes this reaction.[41] The oceans are estimated to release 1–2 million tons of bromoform and 56,000 tons of bromomethane annually.[42]

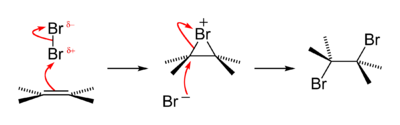

Bromine addition to alkene reaction mechanism

An old qualitative test for the presence of the alkene functional group is that alkenes turn brown aqueous bromine solutions colourless, forming a bromohydrin with some of the dibromoalkane also produced. The reaction passes through a short-lived strongly electrophilic bromonium intermediate. This is an example of a halogen addition reaction.[43]

Occurrence and production[edit]

View of salt evaporation pans on the Dead Sea, where Jordan (right) and Israel (left) produce salt and bromine

Bromine is significantly less abundant in the crust than fluorine or chlorine, comprising only 2.5 parts per million of the Earth’s crustal rocks, and then only as bromide salts. It is the forty-sixth most abundant element in Earth’s crust. It is significantly more abundant in the oceans, resulting from long-term leaching. There, it makes up 65 parts per million, corresponding to a ratio of about one bromine atom for every 660 chlorine atoms. Salt lakes and brine wells may have higher bromine concentrations: for example, the Dead Sea contains 0.4% bromide ions.[44] It is from these sources that bromine extraction is mostly economically feasible.[45][46][47]

The main sources of bromine are in the United States and Israel.[citation needed] The element is liberated by halogen exchange, using chlorine gas to oxidise Br− to Br2. This is then removed with a blast of steam or air, and is then condensed and purified.[48] Today, bromine is transported in large-capacity metal drums or lead-lined tanks that can hold hundreds of kilograms or even tonnes of bromine. The bromine industry is about one-hundredth the size of the chlorine industry. Laboratory production is unnecessary because bromine is commercially available and has a long shelf life.[49]

Applications[edit]

A wide variety of organobromine compounds are used in industry. Some are prepared from bromine and others are prepared from hydrogen bromide, which is obtained by burning hydrogen in bromine.[50]

Flame retardants[edit]

Brominated flame retardants represent a commodity of growing importance, and make up the largest commercial use of bromine. When the brominated material burns, the flame retardant produces hydrobromic acid which interferes in the radical chain reaction of the oxidation reaction of the fire. The mechanism is that the highly reactive hydrogen radicals, oxygen radicals, and hydroxy radicals react with hydrobromic acid to form less reactive bromine radicals (i.e., free bromine atoms). Bromine atoms may also react directly with other radicals to help terminate the free radical chain-reactions that characterise combustion.[51][52]

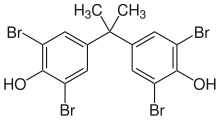

To make brominated polymers and plastics, bromine-containing compounds can be incorporated into the polymer during polymerisation. One method is to include a relatively small amount of brominated monomer during the polymerisation process. For example, vinyl bromide can be used in the production of polyethylene, polyvinyl chloride or polypropylene. Specific highly brominated molecules can also be added that participate in the polymerisation process For example, tetrabromobisphenol A can be added to polyesters or epoxy resins, where it becomes part of the polymer. Epoxies used in printed circuit boards are normally made from such flame retardant resins, indicated by the FR in the abbreviation of the products (FR-4 and FR-2). In some cases, the bromine-containing compound may be added after polymerisation. For example, decabromodiphenyl ether can be added to the final polymers.[53]

A number of gaseous or highly volatile brominated halomethane compounds are non-toxic and make superior fire suppressant agents by this same mechanism, and are particularly effective in enclosed spaces such as submarines, airplanes, and spacecraft. However, they are expensive and their production and use has been greatly curtailed due to their effect as ozone-depleting agents. They are no longer used in routine fire extinguishers, but retain niche uses in aerospace and military automatic fire suppression applications. They include bromochloromethane (Halon 1011, CH2BrCl), bromochlorodifluoromethane (Halon 1211, CBrClF2), and bromotrifluoromethane (Halon 1301, CBrF3).[54]

Other uses[edit]

Silver bromide is used, either alone or in combination with silver chloride and silver iodide, as the light sensitive constituent of photographic emulsions.[49]

Ethylene bromide was an additive in gasolines containing lead anti-engine knocking agents. It scavenges lead by forming volatile lead bromide, which is exhausted from the engine. This application accounted for 77% of the bromine use in 1966 in the US. This application has declined since the 1970s due to environmental regulations (see below).[55]

Brominated vegetable oil (BVO), a complex mixture of plant-derived triglycerides that have been reacted to contain atoms of the element bromine bonded to the molecules, is used primarily to help emulsify citrus-flavored soft drinks, preventing them from separating during distribution.

Poisonous bromomethane was widely used as pesticide to fumigate soil and to fumigate housing, by the tenting method. Ethylene bromide was similarly used.[56] These volatile organobromine compounds are all now regulated as ozone depletion agents. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer scheduled the phase out for the ozone depleting chemical by 2005, and organobromide pesticides are no longer used (in housing fumigation they have been replaced by such compounds as sulfuryl fluoride, which contain neither the chlorine or bromine organics which harm ozone). Before the Montreal protocol in 1991 (for example) an estimated 35,000 tonnes of the chemical were used to control nematodes, fungi, weeds and other soil-borne diseases.[57][58]

In pharmacology, inorganic bromide compounds, especially potassium bromide, were frequently used as general sedatives in the 19th and early 20th century. Bromides in the form of simple salts are still used as anticonvulsants in both veterinary and human medicine, although the latter use varies from country to country. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not approve bromide for the treatment of any disease, and it was removed from over-the-counter sedative products like Bromo-Seltzer, in 1975.[59] Commercially available organobromine pharmaceuticals include the vasodilator nicergoline, the sedative brotizolam, the anticancer agent pipobroman, and the antiseptic merbromin. Otherwise, organobromine compounds are rarely pharmaceutically useful, in contrast to the situation for organofluorine compounds. Several drugs are produced as the bromide (or equivalents, hydrobromide) salts, but in such cases bromide serves as an innocuous counterion of no biological significance.[40]

Other uses of organobromine compounds include high-density drilling fluids, dyes (such as Tyrian purple and the indicator bromothymol blue), and pharmaceuticals. Bromine itself, as well as some of its compounds, are used in water treatment, and is the precursor of a variety of inorganic compounds with an enormous number of applications (e.g. silver bromide for photography).[49] Zinc–bromine batteries are hybrid flow batteries used for stationary electrical power backup and storage; from household scale to industrial scale.

Bromine is used in cooling towers (in place of chlorine) for controlling bacteria, algae, fungi, and zebra mussels.[60]

Because it has similar antiseptic qualities to chlorine, bromine can be used in the same manner as chlorine as a disinfectant or antimicrobial in applications such as swimming pools. However, bromine is usually not used outside for these applications due to it being relatively more expensive than chlorine and the absence of a stabilizer to protect it from the sun. For indoor pools, it can be a good option as it is effective at a wider pH range. It is also more stable in a heated pool or hot tub.

Biological role and toxicity[edit]

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling:[61] | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H314, H330, H400 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P260, P273, P280, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340+P310, P305+P351+P338 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

[62] 3 0 0 |

A 2014 study suggests that bromine (in the form of bromide ion) is a necessary cofactor in the biosynthesis of collagen IV, making the element essential to basement membrane architecture and tissue development in animals.[63] Nevertheless, no clear deprivation symptoms or syndromes have been documented.[64] In other biological functions, bromine may be non-essential but still beneficial when it takes the place of chlorine. For example, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, formed by the eosinophil, and either chloride or bromide ions, eosinophil peroxidase provides a potent mechanism by which eosinophils kill multicellular parasites (such as the nematode worms involved in filariasis) and some bacteria (such as tuberculosis bacteria). Eosinophil peroxidase is a haloperoxidase that preferentially uses bromide over chloride for this purpose, generating hypobromite (hypobromous acid), although the use of chloride is possible.[65]

α-Haloesters are generally thought of as highly reactive and consequently toxic intermediates in organic synthesis. Nevertheless, mammals, including humans, cats, and rats, appear to biosynthesize traces of an α-bromoester, 2-octyl 4-bromo-3-oxobutanoate, which is found in their cerebrospinal fluid and appears to play a yet unclarified role in inducing REM sleep.[42] Neutrophil myeloperoxidase can use H2O2 and Br− to brominate deoxycytidine, which could result in DNA mutations.[66] Marine organisms are the main source of organobromine compounds, and it is in these organisms that bromine is more firmly shown to be essential. More than 1600 such organobromine compounds were identified by 1999. The most abundant is methyl bromide (CH3Br), of which an estimated 56,000 tonnes is produced by marine algae each year.[42] The essential oil of the Hawaiian alga Asparagopsis taxiformis consists of 80% bromoform.[67] Most of such organobromine compounds in the sea are made by the action of a unique algal enzyme, vanadium bromoperoxidase.[68]

The bromide anion is not very toxic: a normal daily intake is 2 to 8 milligrams.[64] However, high levels of bromide chronically impair the membrane of neurons, which progressively impairs neuronal transmission, leading to toxicity, known as bromism. Bromide has an elimination half-life of 9 to 12 days, which can lead to excessive accumulation. Doses of 0.5 to 1 gram per day of bromide can lead to bromism. Historically, the therapeutic dose of bromide is about 3 to 5 grams of bromide, thus explaining why chronic toxicity (bromism) was once so common. While significant and sometimes serious disturbances occur to neurologic, psychiatric, dermatological, and gastrointestinal functions, death from bromism is rare.[69] Bromism is caused by a neurotoxic effect on the brain which results in somnolence, psychosis, seizures and delirium.[70]

Elemental bromine is toxic and causes chemical burns on human flesh. Inhaling bromine gas results in similar irritation of the respiratory tract, causing coughing, choking, shortness of breath, and death if inhaled in large enough amounts. Chronic exposure may lead to frequent bronchial infections and a general deterioration of health. As a strong oxidising agent, bromine is incompatible with most organic and inorganic compounds.[71] Caution is required when transporting bromine; it is commonly carried in steel tanks lined with lead, supported by strong metal frames.[49] The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the United States has set a permissible exposure limit (PEL) for bromine at a time-weighted average (TWA) of 0.1 ppm. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of TWA 0.1 ppm and a short-term limit of 0.3 ppm. The exposure to bromine immediately dangerous to life and health (IDLH) is 3 ppm.[72] Bromine is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[73]

2-Octyl 4-bromo-3-oxobutanoate, an organobromine compound found in mammalian cerebrospinal fluid

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Bromine». CIAAW. 2011.

- ^ a b Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.121. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.

- ^ Br(II) is known to occur in bromine monoxide radical; see Kinetics of the bromine monoxide radical + bromine monoxide radical reaction

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). «Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds». CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^

Löwig, Carl Jacob (1829). Das Brom und seine chemischen Verhältnisse [Bromine and its chemical relationships] (in German). Heidelberg: Carl Winter. - ^ a b c Balard, A. J. (1826). «Mémoire sur une substance particulière contenue dans l’eau de la mer» [Memoir on a peculiar substance contained in sea water]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 2nd series (in French). 32: 337–381. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ a b Balard, Antoine (1826). «Memoir on a peculiar Substance contained in Sea Water». Annals of Philosophy. 28: 381–387 and 411–426. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements: XVII. The halogen family». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (11): 1915. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9.1915W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1915.

- ^ Landolt, Hans Heinrich (1890). «Nekrolog: Carl Löwig». Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 23 (3): 905–909. doi:10.1002/cber.18900230395. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. «bromine». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ muria. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ Vauquelin, L. N.; Thenard, L.J.; Gay-Lussac, J.L. (1826). «Rapport sur la Mémoire de M. Balard relatif à une nouvelle Substance» [Report on a memoir by Mr. Balard regarding a new substance]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 2nd series (in French). 32: 382–384. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ βρῶμος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ On page 341 of his article, A. J. Balard (1826) «Mémoire sur une substance particulière contenue dans l’eau de la mer» [Memoir on a peculiar substance contained in sea water], Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 2nd series, vol. 32, pp. 337–381 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Balard states that Mr. Anglada persuaded him to name his new element brôme. However, on page 382 of the same journal – «Rapport sur la Mémoire de M. Balard relatif à une nouvelle Substance» [Report on a memoir by Mr. Balard regarding a new substance], Annales de Chimie et de Physique, series 2, vol. 32, pp. 382–384. Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine – a committee of the French Academy of Sciences claimed that they had renamed the new element brôme.

- ^ Wisniak, Jaime (2004). «Antoine-Jerôme Balard. The discoverer of bromine» (PDF). Revista CENIC Ciencias Químicas. 35 (1): 35–40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 790

- ^ Barger, M. Susan; White, William Blaine (2000). «Technological Practice of Daguerreotypy». The Daguerreotype: Nineteenth-century Technology and Modern Science. JHU Press. pp. 31–35. ISBN 978-0-8018-6458-2.

- ^ Shorter, Edward (1997). A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac. John Wiley and Sons. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-471-24531-5.

- ^ Corey J Hilmas; Jeffery K Smart; Benjamin A Hill (2008). «Chapter 2: History of Chemical Warfare (pdf)» (PDF). Medical Aspects of Chemical Warfare. Borden Institute. pp. 12–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 800–4

- ^ «Johann Wolfgang Dobereiner». Purdue University. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ «A Historic Overview: Mendeleev and the Periodic Table» (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 793–4

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 804–9

- ^ Duan, Defang; et al. (26 September 2007). «Ab initio studies of solid bromine under high pressure». Physical Review B. 76 (10): 104113. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..76j4113D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.104113.

- ^ Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), «The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties», Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729….3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 809–12

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 812–6

- ^ a b c d e f g Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 821–4

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 824–8

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 828–31

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 832–5

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 842–4

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 853–9

- ^ Perry, Dale L.; Phillips, Sidney L. (1995), Handbook of Inorganic Compounds, CRC Press, p. 74, ISBN 978-0-8493-8671-8, archived from the original on 25 July 2021, retrieved 25 August 2015

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 850–1

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 862–5

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 871–2

- ^ a b c Ioffe, David and Kampf, Arieh (2002) «Bromine, Organic Compounds» in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0218151325150606.a01.

- ^ Carter-Franklin, Jayme N.; Butler, Alison (2004). «Vanadium Bromoperoxidase-Catalyzed Biosynthesis of Halogenated Marine Natural Products». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (46): 15060–6. doi:10.1021/ja047925p. PMID 15548002.

- ^ a b c Gribble, Gordon W. (1999). «The diversity of naturally occurring organobromine compounds». Chemical Society Reviews. 28 (5): 335–346. doi:10.1039/a900201d.

- ^ Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 427–9. ISBN 978-0-19-927029-3.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 795–6

- ^ Tallmadge, John A.; Butt, John B.; Solomon Herman J. (1964). «Minerals From Sea Salt». Ind. Eng. Chem. 56 (7): 44–65. doi:10.1021/ie50655a008.

- ^ Oumeish, Oumeish Youssef (1996). «Climatotherapy at the Dead Sea in Jordan». Clinics in Dermatology. 14 (6): 659–664. doi:10.1016/S0738-081X(96)00101-0. PMID 8960809.

- ^ Al-Weshah, Radwan A. (2008). «The water balance of the Dead Sea: an integrated approach». Hydrological Processes. 14 (1): 145–154. Bibcode:2000HyPr…14..145A. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1085(200001)14:1<145::AID-HYP916>3.0.CO;2-N.

- ^ «Process operations at Octel Amlwch». Octel Bromine Works. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 798–9

- ^ Mills, Jack F. (2002). «Bromine». Bromine: in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_391. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Green, Joseph (1996). «Mechanisms for Flame Retardancy and Smoke suppression – A Review». Journal of Fire Sciences. 14 (6): 426–442. doi:10.1177/073490419601400602. S2CID 95145090.

- ^ Kaspersma, Jelle; Doumena, Cindy; Munrob Sheilaand; Prinsa, Anne-Marie (2002). «Fire retardant mechanism of aliphatic bromine compounds in polystyrene and polypropylene». Polymer Degradation and Stability. 77 (2): 325–331. doi:10.1016/S0141-3910(02)00067-8.

- ^ Weil, Edward D.; Levchik, Sergei (2004). «A Review of Current Flame Retardant Systems for Epoxy Resins». Journal of Fire Sciences. 22: 25–40. doi:10.1177/0734904104038107. S2CID 95746728.

- ^ Günter Siegemund, Werner Schwertfeger, Andrew Feiring, Bruce Smart, Fred Behr, Herward Vogel, Blaine McKusick «Fluorine Compounds, Organic» Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_349

- ^ Alaeea, Mehran; Ariasb, Pedro; Sjödinc, Andreas; Bergman, Åke (2003). «An overview of commercially used brominated flame retardants, their applications, their use patterns in different countries/regions and possible modes of release». Environment International. 29 (6): 683–9. doi:10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00121-1. PMID 12850087.

- ^ Lyday, Phyllis A. «Mineral Yearbook 2007: Bromine» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Messenger, Belinda; Braun, Adolf (2000). «Alternatives to Methyl Bromide for the Control of Soil-Borne Diseases and Pests in California» (PDF). Pest Management Analysis and Planning Program. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Decanio, Stephen J.; Norman, Catherine S. (2008). «Economics of the «Critical Use» of Methyl bromide under the Montreal Protocol». Contemporary Economic Policy. 23 (3): 376–393. doi:10.1093/cep/byi028.

- ^ Samuel Hopkins Adams (1905). The Great American fraud. Press of the American Medical Association. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived 10 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine Choose the Right Cooling Tower Chemicals | Power Engineering |1998

- ^ «Bromine 207888». Sigma-Aldrich. 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ «Msds — 207888». Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ McCall AS; Cummings CF; Bhave G; Vanacore R; Page-McCaw A; et al. (2014). «Bromine Is an Essential Trace Element for Assembly of Collagen IV Scaffolds in Tissue Development and Architecture». Cell. 157 (6): 1380–92. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.009. PMC 4144415. PMID 24906154.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Forrest H. (2000). «Possibly Essential Trace Elements». Clinical nutrition of the essential trace elements and minerals : The guide for health professionals. Clinical Nutrition of the Essential Trace Elements and Minerals. pp. 11–36. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-040-7_2. ISBN 978-1-61737-090-8.

- ^ Mayeno AN; Curran AJ; Roberts RL; Foote CS (1989). «Eosinophils preferentially use bromide to generate halogenating agents». J. Biol. Chem. 264 (10): 5660–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83599-2. PMID 2538427.

- ^ Henderson JP; Byun J; Williams MV; Mueller DM (2001). «Production of brominating intermediates by myeloperoxidase». J. Biol. Chem. 276 (11): 7867–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M005379200. PMID 11096071.

- ^ Burreson, B. Jay; Moore, Richard E.; Roller, Peter P. (1976). «Volatile halogen compounds in the alga Asparagopsis taxiformis (Rhodophyta)». Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 24 (4): 856–861. doi:10.1021/jf60206a040.

- ^ Butler, Alison; Carter-Franklin, Jayme N. (2004). «The role of vanadium bromoperoxidase in the biosynthesis of halogenated marine natural products». Natural Product Reports. 21 (1): 180–8. doi:10.1039/b302337k. PMID 15039842. S2CID 19115256.

- ^ Olson, Kent R. (1 November 2003). Poisoning & drug overdose (4th ed.). Appleton & Lange. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-8385-8172-8. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Galanter, Marc; Kleber, Herbert D. (1 July 2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). United States of America: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ Science Lab.com. «Material Safety Data Sheet: Bromine MSDS». sciencelab.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. «#0064». National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ «40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities» (PDF). Federal Register (1 July 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

General and cited references[edit]

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

Liquid and gas bromine inside transparent cube |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bromine | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (BROH-meen, -min, -myne) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | reddish-brown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Br) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bromine in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 17 (halogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d10 4s2 4p5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | liquid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (Br2) 265.8 K (−7.2 °C, 19 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | (Br2) 332.0 K (58.8 °C, 137.8 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | Br2, liquid: 3.1028 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 265.90 K, 5.8 kPa[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 588 K, 10.34 MPa[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (Br2) 10.571 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporisation | (Br2) 29.96 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (Br2) 75.69 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapour pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, +1, 2,[3] +3, +4, +5, +7 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.96 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionisation energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 120 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 120±3 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 185 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of bromine |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | orthorhombic

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 206 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.122 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 7.8×1010 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −56.4×10−6 cm3/mol[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7726-95-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Antoine Jérôme Balard and Carl Jacob Löwig (1825) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of bromine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Bromine is a chemical element with the symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is the third-lightest element in group 17 of the periodic table (halogens) and is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine. Isolated independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig (in 1825) and Antoine Jérôme Balard (in 1826), its name was derived from the Ancient Greek βρῶμος (bromos) meaning «stench», referring to its sharp and pungent smell.

Elemental bromine is very reactive and thus does not occur as a native element in nature but it occurs in colourless soluble crystalline mineral halide salts, analogous to table salt. In fact, bromine and all the halogens are so reactive that they form bonds in pairs—never in single atoms. While it is rather rare in the Earth’s crust, the high solubility of the bromide ion (Br−) has caused its accumulation in the oceans. Commercially the element is easily extracted from brine evaporation ponds, mostly in the United States and Israel. The mass of bromine in the oceans is about one three-hundredth that of chlorine.

At standard conditions for temperature and pressure it is a liquid; the only other element that is liquid under these conditions is mercury. At high temperatures, organobromine compounds readily dissociate to yield free bromine atoms, a process that stops free radical chemical chain reactions. This effect makes organobromine compounds useful as fire retardants, and more than half the bromine produced worldwide each year is put to this purpose. The same property causes ultraviolet sunlight to dissociate volatile organobromine compounds in the atmosphere to yield free bromine atoms, causing ozone depletion. As a result, many organobromine compounds—such as the pesticide methyl bromide—are no longer used. Bromine compounds are still used in well drilling fluids, in photographic film, and as an intermediate in the manufacture of organic chemicals.

Large amounts of bromide salts are toxic from the action of soluble bromide ions, causing bromism. However, a clear biological role for bromide ions and hypobromous acid has recently been elucidated, and it now appears that bromine is an essential trace element in humans. The role of biological organobromine compounds in sea life such as algae has been known for much longer. As a pharmaceutical, the simple bromide ion (Br−) has inhibitory effects on the central nervous system, and bromide salts were once a major medical sedative, before replacement by shorter-acting drugs. They retain niche uses as antiepileptics.

History[edit]

Bromine was discovered independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig[6] and Antoine Balard,[7][8] in 1825 and 1826, respectively.[9]

Löwig isolated bromine from a mineral water spring from his hometown Bad Kreuznach in 1825. Löwig used a solution of the mineral salt saturated with chlorine and extracted the bromine with diethyl ether. After evaporation of the ether, a brown liquid remained. With this liquid as a sample of his work he applied for a position in the laboratory of Leopold Gmelin in Heidelberg. The publication of the results was delayed and Balard published his results first.[10]

Balard found bromine chemicals in the ash of seaweed from the salt marshes of Montpellier. The seaweed was used to produce iodine, but also contained bromine. Balard distilled the bromine from a solution of seaweed ash saturated with chlorine. The properties of the resulting substance were intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine; thus he tried to prove that the substance was iodine monochloride (ICl), but after failing to do so he was sure that he had found a new element and named it muride, derived from the Latin word muria («brine»).[8][11][12]

After the French chemists Louis Nicolas Vauquelin, Louis Jacques Thénard, and Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac approved the experiments of the young pharmacist Balard, the results were presented at a lecture of the Académie des Sciences and published in Annales de Chimie et Physique.[7] In his publication, Balard stated that he changed the name from muride to brôme on the proposal of M. Anglada. The name brôme (bromine) derives from the Greek βρῶμος (brômos, «stench»).[7][13][11][14] Other sources claim that the French chemist and physicist Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac suggested the name brôme for the characteristic smell of the vapors.[15][16] Bromine was not produced in large quantities until 1858, when the discovery of salt deposits in Stassfurt enabled its production as a by-product of potash.[17]

Apart from some minor medical applications, the first commercial use was the daguerreotype. In 1840, bromine was discovered to have some advantages over the previously used iodine vapor to create the light sensitive silver halide layer in daguerreotypy.[18]

Potassium bromide and sodium bromide were used as anticonvulsants and sedatives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but were gradually superseded by chloral hydrate and then by the barbiturates.[19] In the early years of the First World War, bromine compounds such as xylyl bromide were used as poison gas.[20]

Properties[edit]

Bromine is the third halogen, being a nonmetal in group 17 of the periodic table. Its properties are thus similar to those of fluorine, chlorine, and iodine, and tend to be intermediate between those of the two neighbouring halogens, chlorine, and iodine. Bromine has the electron configuration [Ar]4s23d104p5, with the seven electrons in the fourth and outermost shell acting as its valence electrons. Like all halogens, it is thus one electron short of a full octet, and is hence a strong oxidising agent, reacting with many elements in order to complete its outer shell.[21] Corresponding to periodic trends, it is intermediate in electronegativity between chlorine and iodine (F: 3.98, Cl: 3.16, Br: 2.96, I: 2.66), and is less reactive than chlorine and more reactive than iodine. It is also a weaker oxidising agent than chlorine, but a stronger one than iodine. Conversely, the bromide ion is a weaker reducing agent than iodide, but a stronger one than chloride.[21] These similarities led to chlorine, bromine, and iodine together being classified as one of the original triads of Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner, whose work foreshadowed the periodic law for chemical elements.[22][23] It is intermediate in atomic radius between chlorine and iodine, and this leads to many of its atomic properties being similarly intermediate in value between chlorine and iodine, such as first ionisation energy, electron affinity, enthalpy of dissociation of the X2 molecule (X = Cl, Br, I), ionic radius, and X–X bond length.[21] The volatility of bromine accentuates its very penetrating, choking, and unpleasant odour.[24]

All four stable halogens experience intermolecular van der Waals forces of attraction, and their strength increases together with the number of electrons among all homonuclear diatomic halogen molecules. Thus, the melting and boiling points of bromine are intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine. As a result of the increasing molecular weight of the halogens down the group, the density and heats of fusion and vaporisation of bromine are again intermediate between those of chlorine and iodine, although all their heats of vaporisation are fairly low (leading to high volatility) thanks to their diatomic molecular structure.[21] The halogens darken in colour as the group is descended: fluorine is a very pale yellow gas, chlorine is greenish-yellow, and bromine is a reddish-brown volatile liquid that melts at −7.2 °C and boils at 58.8 °C. (Iodine is a shiny black solid.) This trend occurs because the wavelengths of visible light absorbed by the halogens increase down the group.[21] Specifically, the colour of a halogen, such as bromine, results from the electron transition between the highest occupied antibonding πg molecular orbital and the lowest vacant antibonding σu molecular orbital.[25] The colour fades at low temperatures so that solid bromine at −195 °C is pale yellow.[21]

Like solid chlorine and iodine, solid bromine crystallises in the orthorhombic crystal system, in a layered arrangement of Br2 molecules. The Br–Br distance is 227 pm (close to the gaseous Br–Br distance of 228 pm) and the Br···Br distance between molecules is 331 pm within a layer and 399 pm between layers (compare the van der Waals radius of bromine, 195 pm). This structure means that bromine is a very poor conductor of electricity, with a conductivity of around 5 × 10−13 Ω−1 cm−1 just below the melting point, although this is higher than the essentially undetectable conductivity of chlorine.[21]

At a pressure of 55 GPa (roughly 540,000 times atmospheric pressure) bromine undergoes an insulator-to-metal transition. At 75 GPa it changes to a face-centered orthorhombic structure. At 100 GPa it changes to a body centered orthorhombic monatomic form.[26]

Isotopes[edit]

Bromine has two stable isotopes, 79Br and 81Br. These are its only two natural isotopes, with 79Br making up 51% of natural bromine and 81Br making up the remaining 49%. Both have nuclear spin 3/2− and thus may be used for nuclear magnetic resonance, although 81Br is more favourable. The relatively 1:1 distribution of the two isotopes in nature is helpful in identification of bromine containing compounds using mass spectroscopy. Other bromine isotopes are all radioactive, with half-lives too short to occur in nature. Of these, the most important are 80Br (t1/2 = 17.7 min), 80mBr (t1/2 = 4.421 h), and 82Br (t1/2 = 35.28 h), which may be produced from the neutron activation of natural bromine.[21] The most stable bromine radioisotope is 77Br (t1/2 = 57.04 h). The primary decay mode of isotopes lighter than 79Br is electron capture to isotopes of selenium; that of isotopes heavier than 81Br is beta decay to isotopes of krypton; and 80Br may decay by either mode to stable 80Se or 80Kr.[27]

Chemistry and compounds[edit]

| X | XX | HX | BX3 | AlX3 | CX4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 159 | 574 | 645 | 582 | 456 |

| Cl | 243 | 428 | 444 | 427 | 327 |

| Br | 193 | 363 | 368 | 360 | 272 |

| I | 151 | 294 | 272 | 285 | 239 |

Bromine is intermediate in reactivity between chlorine and iodine, and is one of the most reactive elements. Bond energies to bromine tend to be lower than those to chlorine but higher than those to iodine, and bromine is a weaker oxidising agent than chlorine but a stronger one than iodine. This can be seen from the standard electrode potentials of the X2/X− couples (F, +2.866 V; Cl, +1.395 V; Br, +1.087 V; I, +0.615 V; At, approximately +0.3 V). Bromination often leads to higher oxidation states than iodination but lower or equal oxidation states to chlorination. Bromine tends to react with compounds including M–M, M–H, or M–C bonds to form M–Br bonds.[25]

Hydrogen bromide[edit]

The simplest compound of bromine is hydrogen bromide, HBr. It is mainly used in the production of inorganic bromides and alkyl bromides, and as a catalyst for many reactions in organic chemistry. Industrially, it is mainly produced by the reaction of hydrogen gas with bromine gas at 200–400 °C with a platinum catalyst. However, reduction of bromine with red phosphorus is a more practical way to produce hydrogen bromide in the laboratory:[28]

- 2 P + 6 H2O + 3 Br2 → 6 HBr + 2 H3PO3

- H3PO3 + H2O + Br2 → 2 HBr + H3PO4

At room temperature, hydrogen bromide is a colourless gas, like all the hydrogen halides apart from hydrogen fluoride, since hydrogen cannot form strong hydrogen bonds to the large and only mildly electronegative bromine atom; however, weak hydrogen bonding is present in solid crystalline hydrogen bromide at low temperatures, similar to the hydrogen fluoride structure, before disorder begins to prevail as the temperature is raised.[28] Aqueous hydrogen bromide is known as hydrobromic acid, which is a strong acid (pKa = −9) because the hydrogen bonds to bromine are too weak to inhibit dissociation. The HBr/H2O system also involves many hydrates HBr·nH2O for n = 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6, which are essentially salts of bromine anions and hydronium cations. Hydrobromic acid forms an azeotrope with boiling point 124.3 °C at 47.63 g HBr per 100 g solution; thus hydrobromic acid cannot be concentrated beyond this point by distillation.[29]

Unlike hydrogen fluoride, anhydrous liquid hydrogen bromide is difficult to work with as a solvent, because its boiling point is low, it has a small liquid range, its dielectric constant is low and it does not dissociate appreciably into H2Br+ and HBr−

2 ions – the latter, in any case, are much less stable than the bifluoride ions (HF−

2) due to the very weak hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and bromine, though its salts with very large and weakly polarising cations such as Cs+ and NR+

4 (R = Me, Et, Bun) may still be isolated. Anhydrous hydrogen bromide is a poor solvent, only able to dissolve small molecular compounds such as nitrosyl chloride and phenol, or salts with very low lattice energies such as tetraalkylammonium halides.[29]

Other binary bromides[edit]