Добавлено в закладки: 42

Содержание

- Арабский алфавит с переводом и пояснениями к буквам.

- Буквы, не вошедшие в основной состав Алфавита и имеющие специфику письма и чтения

- Особенности арабского алфавита и письма.

- Почему арабский алфавит не содержит гласные буквы?

- История появления арабского алфавита и письменности

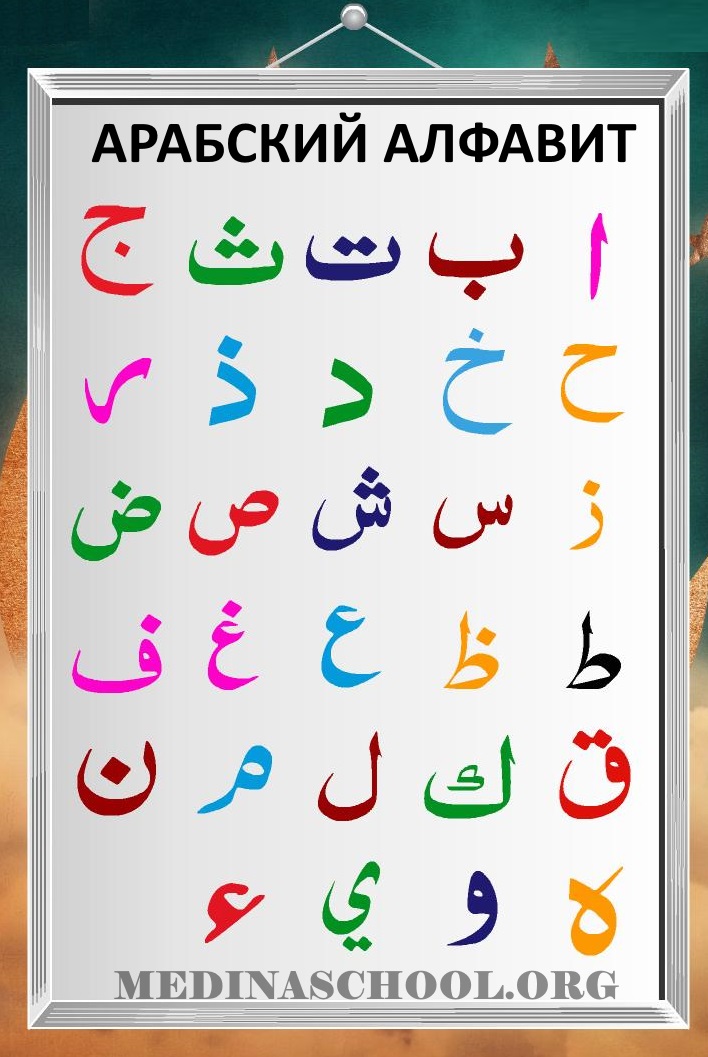

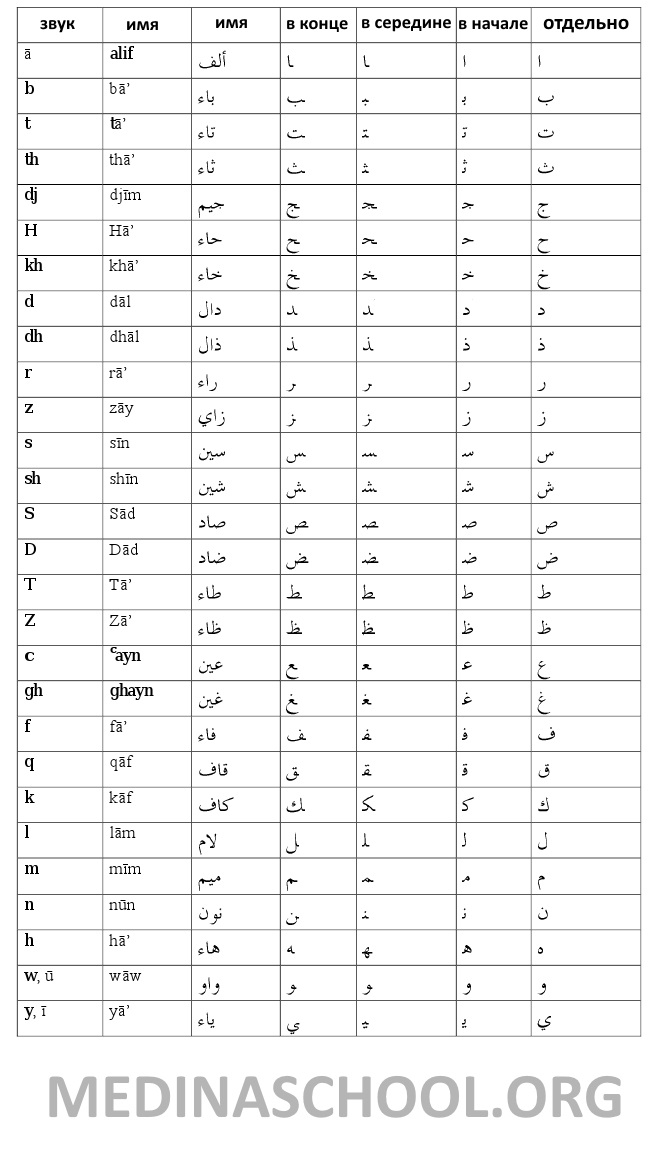

Арабский алфавит состоит из 28 букв. Одни буквы соединяются с соседними буквами в словах с обеих сторон, а другие соединяются только справа, поэтому их написание совпадает в начальном и обособленном вариантах, а также в срединном и конечном.

Так как арабское письмо образует «вязь», каждая буква арабского алфавита имеет четыре варианта написания: обособленный, начальный, срединный и конечный. В таблице ниже каждая буква арабского алфавита показана в нескольких вариантах написания.

Изучить все правила письма и чтения на основе арабского алфавита можно по видеокурсу бесплатно.

Арабский алфавит с переводом и пояснениями к буквам.

| № | название | отдельное написание | начальная позиция | срединная позиция | конечная позиция | транскрипция и произношение |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | أَلِفٌ Алиф | ا | ا | ـا | ـا | Не имеет собственного звучания! Произносится только в сочетании с огласовками: اَ — а; اِ — и; اُ — у. |

| 2 | بَاءٌ Ба:’ | ب | بـ | ـبـ | ـب | Как русский [б]. |

| 3 | تَاءٌ Та:’ | ت | تـ | ـتـ | ـت | Как русский [т]. |

| 4 | ثَاءٌ Tha:’ | ث | ثـ | ـثـ | ـث | [th] — межзубный «с», схож с произношением в слове think в английском языке. |

| 5 | جِيمٌ Джи:м | ج | جـ | ـجـ | ـج | [дж] — сочетание звуков «д» и «ж», с акцентом звучания на «ж», мягко. |

| 6 | حَاءٌХа:’ | ح | حـ | ـحـ | ـح | [х] — очень мягкий звук, произносится на выдохе из глубины гортани. |

| 7 | خَاءٌХo:’ | خ | خـ | ـخـ | ـخ | [х] — твердый скребущий звук, придает огласовке фатха [а] звучание «о». См. урок по арабскому алфавиту об огласовках. |

| 8 | دَالٌ Дэ:ль | د | د | ـد | ـد | Как русский [д]. |

| 9 | ذَالٌ Thэ:ль | ذ | ذ | ـذ | ـذ | [th] – межзубный [з], произносится схоже с английским в слове they. |

| 10 | رَاءٌ Ро:’ | ر | ر | ـر | ـر | Как русский [р], но тверже и энергичней. |

| 11 | زََايٌّ Зэ:йй | ز | ز | ـز | ـز | Как русский [з]. |

| 12 | سِينٌ Си:н | س | سـ | ـسـ | ـس | Как русский [с]. |

| 13 | شِينٌ Ши:н | ش | شـ | ـشـ | ـش | Как русский [ш], но мягче. |

| 14 | صَادٌ Со:д | ص | صـ | ـصـ | ـص | Твердый звук [c]. Огласовка фатха звучит о-образно. |

| 15 | ضَادٌ До:д | ض | ضـ | ـضـ | ـض | Твердый [д], который имеет двоякое звучание, похожее на [д] и [з] одновременно. Огласовка фатха звучит о-образно. |

| 16 | طَاءٌ То:’ | ط | طـ | ـطـ | ـط | Твердый звук [т]. Огласовка фатха звучит о-образно. |

| 17 | ظَاءٌ Зо:’ | ظ | ظـ | ـظـ | ـظ | Твердый межзубный звук [з]. Произносится, как ذ, но более твердо и энергично. Огласовка фатха звучит о-образно. |

| 18 | عَيْنٌЪайн | ع | عـ | ـعـ | ـع | Гортанный звук [Ъ], не имеет аналогов в европейских и русском языках. |

| 19 | غَيْنٌГЪайн | غ | غـ | ـغـ | ـغ | Гортанный звук [ГЪ]. Не имеет аналогов в европейских и русском языках. Отдаленно может напоминать французское произношение “р”. |

| 20 | فَاءٌ Фа:’ | ف | فـ | ـفـ | ـف | Как русский [ф]. |

| 21 | قَافٌ Ко:ф | ق | قـ | ـقـ | ـق | Твердый звук [к], огласовка фатха звучит о-образно. |

| 22 | كَافٌ Кя:ф | ك | كـ | ـكـ | ـك | Как русский [к], но более мягко. |

| 23 | لَامٌ Ля:м | ل | لـ | ـلـ | ـل | Как в русском [ль], мягко. |

| 24 | مِيمٌ Ми:м | م | مـ | ـمـ | ـم | Как русский [м]. |

| 25 | نُونٌ Ну:н | ن | نـ | ـنـ | ـن | Как русский звук [н]. |

| 26 | هَاءٌ ha:’ | ه | هـ | ـهـ | ـه | Очень похоже на украинскую/белорусскую [г]. |

| 27 | وَاوٌ Wа:w | و | و | ـو | ـو | Звук [w] произносится при скруглении губ, схоже с английским в слове white. |

| 28 | يَاءٌ Йа:’ | ي | يـ | ـيـ | ـي | Как русский [й], но более энергично. |

Буквы, не вошедшие в основной состав Алфавита и имеющие специфику письма и чтения

| конечная позиция | срединная позиция | начальная позиция | отдельное написание | название | транскрипция и произношение |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ـة | не существует | не существует | ة | تَاءٌ مَرْبُوطَةٌ Та’-марбута | Вспомогательная буква, которая пишется в конце слов и в большинстве случаев применяется для обозначения женского рода существительных и прилагательных. |

| ـى | ئـ ـئـ В таком виде только с «хамзой» ء |

не существует | ى | أَلِفٌ مَقْصُورَةٌ Алиф-максу:ра | Дословно с арабского – “сокращенный алиф”. Буква в исходном виде пишется только в конце слов. В срединном написании может употребляться только в качестве “подставки” для hамзы. Роль буквы в словах тесно связана с морфологией (арабск. сарф/тасриф) при образовании слов. |

| ـلا | ـلا | لا | لا | لَامٌ-أَلِفٌ Лям-Алиф | Сочетание букв Лям и Алиф идущих друг за другом: ل+ا. Читается по-разному, в зависомости от стоящих с буквами огласовок, как и во всех других случаях. |

| ء ؤ ـئ ـأ | ء ؤ ـئـ ـئ ـأ | ثـ | ء | ثَاءٌ Tha:’ | Знак, который имеет двоякую природу — может выступать в роли буквы, либо в виде знака в сопровождении букв ا، و ، ى Роль в чтении слов сводится к тому, что он отделяет гласные звуки друг от друга (например, как при отрывистом чтении “ко-ординация”). Однако главное назначение и роль hамза — в словообразовании (морфологии) арабского языка. |

Особенности арабского алфавита и письма.

- Система написания арабских букв, в отличие от подавляющего большинства других языков, представляет собой «вязь», где каждая буква соединяется с рядом стоящими буквами в словах. Как мы можем заметить, в русском и европейских языках буквы также могут соединяться между собой, но происходит это при написании от руки, тогда как буквы арабского алфавита составляют вязь при любом варианте написания, как при машинописном (печатном), так и при рукописном.

- Слова и предложения пишутся справа налево, как это было изначально в финикийском письме. Данное обстоятельство зачастую вызывает чувство дискомфорта и растерянности у начинающих изучать арабский язык. Однако не стоит сильно переживать по этому поводу: привыкнуть к письму справа налево не сложно, примерно через месяц изучения Вами арабского алфавита и тренировки письма этот дискомфорт исчезнет. Кстати сказать, владение письмом в обоих направлениях оказывает существенное положительное влияние на развитие обоих полушарий головного мозга, поэтому арабский язык учить полезно!

- Арабский алфавит состоит из 28 букв (по-арабски حُرُوفٌ — «буквы»), все они являются согласными. Каждая арабская буква обозначает один согласный звук. Что касается гласных звуков, то для их обозначения служат специальные знаки — огласовки (по-арабски حَرَكَاتٌ). Это три знака, служащие для отображения гласных «а», «и», «у». Однако произношением трех гласных арабский язык не ограничен. Если мы послушаем арабскую речь, то можем услышать и другие гласные звуки. Данное обстоятельство связано с тем, что произношение каждой из трех огласовок может варьироваться в пределах созвучных ей звуков. Так, произношение «а» в большинстве случаев имеет звучание, близкое к «э» при одновременном произношении с «мягкими» согласными, а также «о»-образное звучание вместе с согласными, которые произносятся твердо и слогах-дифтонгах с буквой وْ и знаком «сукун» (например, в слове رَوْحٌ [роух] — отдых, покой), ярко выраженное звучание «е» в слогах-дифтонгах, где есть буква يْ с знаком «сукун» (например, в слове بَيْتٌ [бейт] — дом). Звук «и» может преобразовываться в «ы» при употреблении с твердо произносимыми согласными, например, в слове طِفْلٌ [тыфль] — ребенок, где буква ط обозначает твердый согласный «т». Что касается огласовки «у», то ее звучание как правило остается неизменным в классическом арабском языке, но для полноты изложения, стоит сказать, что этот звук может меняться на звучание «о» в диалектах арабского языка.

- Помимо основных 3 огласовок существуют три их разновидности, называемые «танвины» (от арабск. تَنْوِينٌ). По сути, это те же огласовки, но пишутся они сдвоенно в конце слов и служат для грамматического определения падежей в словах в неопределенном состоянии. Кроме этого, есть еще три знака — «сукун», который обозначает отсутствие какого-либо гласного у буквы, знак «шадда» — обозначает удвоение согласного, а также знак «хамза», роль которого заключается в отделении двух гласных звуков друг от друга, например, как если бы мы прочитали слово «координация», разделяя две гласные «о» коротким смыканием горла, вот так: «ко-ординация».

Почему арабский алфавит не содержит гласные буквы?

Арабский язык, его алфавит и система письма во многом повторяют языки-предшественники (арамейский, финикийский), в том числе, в отсутствии гласных букв в алфавите. Вместо букв для отображения гласных звуков используются специальные диакретические знаки (огласовки), которые пишутся над и под буквами. В следующей таблице приведены все огласовки и некоторые знаки, а в качестве примера их использования показана буква Алиф.

| обозначение | название | звук | комментарий |

|---|---|---|---|

| اَ* | فَتْحَةٌ Фатха | [а] | гласный звук «а», пишется над буквами |

| اِ | كَسْرَةٌ Кясра | [и] | гласный звук «и», пишется под буквами |

| اُ | ضَمَّةٌ Дамма | [у] | гласный звук «у», пишется над буквами |

| اً | تَنْوِينُ الْفَتْحَةِ Танвин-фатха | [ан] | Употребляется только в конце существительных и прилагательных в неопределенном состоянии. Танвин-фатха и танвин-кясра также встречаются в наречиях. |

| اٍ | تَنْوِينُ الْكَسْرَةِ Танвин-кясра | [ин] | Употребляется только в конце существительных и прилагательных в неопределенном состоянии. Танвин-фатха и танвин-кясра также встречаются в наречиях. |

| اٌ | تَنْوِينُ الضَّمَّةِ Танвин-дамма | [ун] | Употребляется только в конце существительных и прилагательных в неопределенном состоянии. Танвин-фатха и танвин-кясра также встречаются в наречиях. |

| اْ | سُكُونٌ Сукун | — | Обозначает отсутствие гласного звука. |

| * Для наглядности расположения огласовок относительно букв показано сочетание огласовок совместно с Алифом. |

Подробно изучить написание и произношение каждой буквы как отдельно, так и в составе слов и в сочетании с другими буквами и огласовками, Вы можете в видеоуроках курса «Арабский алфавит. Правила письма и чтения». Уроки сопровождаются тестами, отвечая на вопросы которых Вы можете закреплять изученное и не упустите важные моменты.

Частой ошибкой начинающих изучать арабский язык является чтение арабских слов в русском или латинском написании (транслитерация), в то время как только изучение арабского алфавита и произношения каждой буквы гарантирует правильность чтения и произношения слов и фраз. Поэтому очень важно в самом начале обучение хорошо усвоить алфавит.

История появления арабского алфавита и письменности

Арабский алфавит считается одним из древнейших в мире, а регион Ближнего Востока находится среди тех первых регионов мира, где зародилась письменность. Письмо арабских букв берет свои истоки из системы набатейского письма (II век до н. э.), которое, в свою очередь, произошло от арамейского письма (с конца VIII века до н. э. являлся средством международного общения и переписки на Ближнем Востоке, а также языком дипломатических сношений в Персидской империи), берущего свои истоки в финикийской письменности (XV век до н. э.), являющейся одной из первых в истории человечества систем фонетического письма.

В данных видах письменности использовался консонантный принцип, при котором в словах пишутся только буквы, обозначающие согласные звуки, а чтение гласных звуков остается на понимание и знание читателя. В учебных целях арабские слова пишутся с огласовками — специальными знаками для отображения гласных и некоторых других звуков.

- Арабская письменность

- Буквы

- Звуки

- Знаки

- Задания

- Дополнительно

⊗ В этом уроке вы узнаете об арабской письменности, о количестве букв в арабском алфавите, о том как выглядят буквы и на какие категории они подразделяются. Также вы узнаете о том, что такое транскрипция и какие виды транскрипций бывают. Вы узнаете какие виды звуков есть в арабской речи, а также сколько и какие начертания бывают у букв. Вы ознакомитесь о специальными знаками в арабской письменности.

§1. Об арабском алфавите. Арабы пишут и читают справа налево. В арабском алфавите всего 28 букв. На письме отображаются согласные и три долгих гласных. Короткие гласные звуки, а их три, передаются путем специальных значков, так называемыми «огласовками», которые ставятся над или под буквой, (см. урок 2. Огласовки).

Посмотрите как вы выглядит и звучит арабский алфавит.

ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي

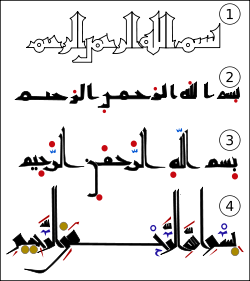

Каждая буква алфавита имеет несколько начертаний, в зависимости от их местоположения в слове. В письме не бывает заглавных букв и в нем существует несколько видов почерков. Одним из распространенных почерков является ʾан-насх̮. Внизу показан пример написания выражения «Во имя Аллаха Милостивого Милосердного» этим почерком.

§2. Как читать тексты без огласовок. В арабских изданиях и в СМИ тексты не сопровождаются огласовками, за исключением учебной и религиозной литературы. Арабы прекрасно читают и понимают тексты без огласовок. Сравнимо это с тем, когда мы читаем текст на русском языке где есть буква Ё без точек. Поэтому устанавливать и воспроизводить гласные в процессе чтения нужно самому читателю. Уверенное владение лексико-грамматическим материалом языка позволяет справится с этой задачей.

Далее переходите на вкладку БУКВЫ.

§1. Арабские буквы. Транскрипция. В арабском языке между системой изображения слов на письме и их звучанием есть разница, поэтому для практичности принято использовать транскрипцию. Транскрипция — это условные знаки или буквы латиницы либо кириллицы, путем которых на письме передаются те или иные звуки, при необходимости они снабжаются специальными значками.

Транскрипция делится на два вида, фонетическая и фонематическая. Фонетическая транскрипция показывает передачу реального произношения, произношение фонем с их оттенками и видами. Фонематическая транскрипция показывает упрощенную передачу лишь фонем того или иного слова, без учета вариантов фонем и их оттенков. При чтении фонематической транскрипции ученику самому придется произносить звуки правильно, основываясь на произношение звуков, услышанных им через аудио прослушивание.

В этом курсе мы будем использовать фонематическую транскрипцию, в качестве вспомогательного механизма для быстрого перехода к чтению текстов.

Ниже приведена таблица арабского алфавита, с указанием названий букв и их аудио звучаний.

№ — Порядковый номер; A — В конце слова; B — В середине слова; C — В начале слова; D — В обособленном виде; E — Название буквы; F — Транскрипция; G — Аудио звучание.

| № | А | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| 1 | ـا | ا | أَلِف

’алиф |

— | |||

| 2 | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب | بَاء

ба̄’ |

б | |

| 3 | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت | تَاء

та̄’ |

т | |

| 4 | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث | ثَاء

с̱а̄’ |

с̱ | |

| 5 | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج | جِيم

джӣм |

дж | |

| 6 | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح | حَاء

х̣а̄’ |

х̣ | |

| 7 | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ | خَاء

х̮а̄’ |

х̮ | |

| 8 | ـد | د | دَال

да̄ль |

д | |||

| 9 | ـذ | ذ | ذَال

з̱а̄ль |

з̱ | |||

| 10 | ـر | ر | رَاء

ра̄’ |

р | |||

| 11 | ـز | ز | زَاى

за̄й |

з | |||

| 12 | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س | سِين

сӣн |

с | |

| 13 | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش | شِين

шӣн |

ш | |

| 14 | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص | صَاد

с̣а̄д |

с̣ | |

| 15 | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض | ضَاد

д̣а̄д |

д̣ | |

| 16 | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط | طَاء

т̣а̄’ |

т̣ | |

| 17 | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ | ظَاء

з̣а̄’ |

з̣ | |

| 18 | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع | عَيْن

‘айн |

‘ | |

| 19 | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ | غَيْن

гайн |

г |

|

| 20 | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف | فَاء

фа̄’ |

ф | |

| 21 | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق | قَاف

к̣а̄ф |

к̣ | |

| 22 | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك | كَاف

ка̄ф |

к | |

| 23 | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل | لاَم

ля̄м |

ль | |

| 24 | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م | مِيم

мӣм |

м | |

| 25 | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن | نُون

нӯн |

н | |

| 26 | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه | هَاء

ха̄’ |

х | |

| 27 | ـو | و | وَاو

ва̄в |

в | |||

| 28 | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي | يَاء

йа̄’ |

й |

§2. Группы и категории букв и их начертания. Арабский алфавит, с точки зрения правописания, делится на две основные группы.

Первая группа — буквы, которые схожи между собой по форме и правописанию, но имеют отличия в дополнительных значках (точках)

ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ

Вторая группа — буквы, которые не имеют себе подобных

Большинство букв алфавита в зависимости от местоположения в слове имеют разные варианты написания, то есть имеют особые начертания в обособленном порядке, в начале, в середине и в конце слов, как показано в таблице. Исходя из этого, буквы можно разделить на две категории:

- Буквы, которые имеют все четыре начертания. Их двадцать две (см. таблицу алфавита). Буквы этой категории могут соединяться с обеих сторон с другими буквами при письме.

- Буквы, которые имеют только два вида начертаний (в таблице показаны на розовом фоне) :1- обособленное — начальное; 2- серединное — конечное. Их шесть. Буквы этой категории могут соединятся только спереди идущими буквами из первой категории, но после себя не дают возможности к без отрывному соединению.

Арабские буквы соединяются между собой соединительной линией ( _ ). Например:

| фан — искусство | ف + ـ + ن = فَــــن |

Слова оканчиваются на конечное начертание буквы. При этом есть буквы, которые полностью находятся над строчкой и есть буквы, половина которых может опускаться ниже строки.

С 4 -го по 12 -ый уроки этого курса мы разберем эти буквы отдельно.

Далее переходите на вкладку ЗВУКИ.

§1. Звуки. В арабском алфавите все 28 букв являются согласными. Однако говорить на арабском, как и на любом языке, не представляется возможным без гласных звуков. Роль гласных звуков выполняют специальные символы, которые называются огласовками, выступающие в качестве кратких гласных. Более подробнее об огласовках во 2-ом уроке курса.

Посмотрите примеры:

Арабский язык отличается сложной фонетической формой. В нем могут встречаться звуки, которые редки в других языках.

Например:

| х̣а̄сӯб компьютер |

حَــاسُوبٌ | ح | |

| ‘алам флаг |

عَــلَمٌ | ع |

Широко используются и горловые звуки.

Например:

| ’усра семья |

أُسْرَةٌ | أ | |

| ха̄тиф телефон |

هَــاتِفٌ | ه |

В примере выше показан знак хамза на букве ’алиф أ , он похож на лежачую цифру четыре ء . Этот знак выражает звук который производится коротким сокращением диафрагмы при произношении звука [а]. Данный звук можно услышать в слове «соавтор». Подробнее об этом звуке мы разберем в 17 уроке этого курса.

В арабской речи также встречаются эмфатические звуки, или как их еще называют «сложные». Эти звуки не встречаются ни в каких языках мира.

Произносятся эмфатические звуки гораздо напряженнее и интенсивнее, чем их соответствующие согласные звуки как сӣн س , да̄ль د , та̄’ ت , з̱а̄ль ذ . Посмотрите примеры:

| с̣а̄д | ص | |

| д̣а̄д | ض | |

| т̣а̄’ | ط | |

| з̣а̄’ | ظ |

Есть также в речи и межзубные звуки:

| с̱ауб одежда |

ثَــوْبٌ | ث | |

| з̱уба̄ба муха |

ذُبَابَةٌ | ذ |

Внимание! алиф ا не несет в себе самостоятельного звучания, он служит для обозначения долготы гласного звука а̄, а также служит подставкой для танвӣн (см. 14 урок курса) и знака хамза ء (см. 17 урок курса) .

Далее переходите на вкладку ЗНАКИ

§1. Знаки, не вошедшие в алфавит. Помимо 28 букв алфавита в арабском языке используются еще три специальных знака, которые по сути являются подобием букв. Некоторые из них несут смысловую нагрузку, а некоторые только выражают особый звук.

Каждый знак мы разберем в этом курсе по отдельности.

№ — Порядковый номер; A — В конце слова; B — В середине слова; C — В начале слова; D — В обособленном виде; E — Название знака; F — Транскрипция.

| № | А | B | C | D | E | F |

| 1 | ء | هَمْزَة хамза |

’ | |||

| ـأ | أ | |||||

| ـإ | إ | |||||

| ـؤ | ؤ | |||||

| ـئ | ـئـ | ئـ | ئ | |||

| 2 | ـة | — | ة | تَاء مَرْبُوطَة та̄’ марбӯт̣а |

— | |

| 3 | ـى | — | ى | أَلِفُ مَقصورة ’алиф мак̣с̣ӯра |

а̄ |

Итак, этом уроке Вы узнали об арабской письменности, о количестве букв в арабском алфавите, о том как выглядят буквы и на какие категории они подразделяются. Также Вы узнали о том, что такое транскрипция и какие виды транскрипций бывают. Вы узнали какие виды звуков есть в арабской речи, а также сколько и какие начертания бывают у букв. Также вы узнали что помимо букв в арабском языке используются букваподобные знаки.

Для закрепления пройденного материала переходите на вкладку ЗАДАНИЯ и выполните все упражнения.

≈1. Внимательно прослушайте каждую букву. Заучите алфавит.

| ث | ت | ب | ا |

| د | خ | ح | ج |

| س | ز | ر | ذ |

| ط | ض | ص | ش |

| ف | غ | ع | ظ |

| م | ل | ك | ق |

| ي | و | ه | ن |

ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي

Во вкладке ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНО распечатайте алфавит для наглядности.

≈2. Переместите букву на ее идентичный сектор.

≈3. Переместите букву к ее правильному названию.

≈4. Переместите букву на ее правильное аудио звучание.

≈5. Выстройте буквы в алфавитном порядке.

≈6. Пройдите ТЕСТ.

Внимание! Если Вы полностью освоили этот урок и выполнили все задания и тесты нажмите кнопку ОТМЕТИТЬ КАК ЗАВЕРШЕННЫЙ и переходите к изучению следующего урока.

Если у Вас возникли вопросы пишите в комментариях.

К какой языковой семье относится арабский язык?

Такие народности как арамейские, финикйские, еврейские, арабские, йеменские, вавилоно-ассирийские имеют общее название как «семитские народности».

Семитские языки в основе своей делятся на «западные» и «восточные». «Восточные» в свою очередь делятся на «северные» и «южные».

Что касается «северной» группы семитских языков, то к ней относятся «канаанейские» и «арамейские» языки. Одной из самых известных диалектов канаанейского языка является еврейский язык.

Что касается «южной» группы, то к ней относятся два больших арабских языка, (южный арабский язык) и (северный арабский язык).

Южный арабский язык называют как «йеменский древний» либо «кахтанейский».

Что касается арабского языка, которое имеет самое широкое распространение сегодня, то он имеет прямое отношение к одному из говоров «северной арабской языковой среды».

Скачайте материалы урока ⇓

| Текст |  |

К началу курса: Арабский Алфавит

Арабский алфавит

Арабский алфавит, арабское письмо, арабица — алфавит, используемый для записи арабского языка и (чаще всего в модифицированном виде) некоторых других языков, в частности фарси, пушту, урду и некоторых тюркских языков. Состоит из 28 букв и используется для письма справа налево. По-арабски называется хуруф (حُرُوف [ḥurūf]— мн.ч. от حَرْف [ḥar̊f]).

Каждая из 28 букв, кроме буквы алиф, обозначает один согласный. Буквы алиф, вав и йа также используются для обозначения долгих гласных: алиф — для обозначения долгого «а», вав — для обозначения долгого «у», йа — для обозначения долгого «и». Начертание букв меняется в зависимости от расположения внутри слова (в начале, в конце или в середине). Заглавных букв нет. Все буквы одного слова пишутся слитно, за исключением шести букв (алиф, даль, заль, ра, зайн, вав), которые не соединяются со следующей буквой.

| # | в конце | в середине | в начале | отдельно | название | транскрипция | числовое значение | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ـا | ا |

أَلِف

[ạảlif] |

алиф |

[ạ] |

1 | ||

| 2 | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب |

بَاء

[bāʾ] |

ба |

[b] |

2 |

| 3 | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت |

تَاء

[tāʾ] |

та |

[t] |

400 |

| 4 | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث |

ثَاء

[tẖāʾ] |

са |

[tẖ] |

500 |

| 5 | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج |

جِيم

[jīm] |

джим |

[j] |

3 |

| 6 | ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح |

حَاء

[ḥāʾ] |

ха |

[ḥ] |

8 |

| 7 | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ |

خَاء

[kẖāʾ] |

ха |

[kẖ] |

600 |

| 8 | ـد | د |

دَال

[dāl] |

даль |

[d] |

4 | ||

| 9 | ـذ | ذ |

ذَال

[dẖāl] |

заль |

[dẖ] |

700 | ||

| 10 | ـر | ر |

رَاء

[rāʾ] |

ра |

[r] |

200 | ||

| 11 | ـز | ز |

زَاى

[zāy̱] |

зайн |

[z] |

7 | ||

| 12 | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س |

سِين

[sīn] |

син |

[s] |

60 |

| 13 | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش |

شِين

[sẖīn] |

шин |

[sẖ] |

300 |

| 14 | ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص |

صَاد

[ṣād] |

сад |

[ṣ] |

90 |

| 15 | ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض |

ضَاد

[ḍād] |

дад |

[ḍ] |

800 |

| 16 | ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط |

طَاء

[ṭāʾ] |

та |

[ṭ] |

9 |

| 17 | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ |

ظَاء

[ẓāʾ] |

за |

[ẓ] |

900 |

| 18 | ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع |

عَيْن

[ʿaẙn] |

ʿайн |

[ʿ] |

70 |

| 19 | ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ |

غَيْن

[gẖaẙn] |

гайн |

[gẖ] |

1000 |

| 20 | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف |

فَاء

[fāʾ] |

фа |

[f] |

80 |

| 21 | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق |

قَاف

[qāf] |

каф |

[q] |

100 |

| 22 | ـك | ـكـ | كـ | ك |

كَاف

[kāf] |

кяф |

[k] |

20 |

| 23 | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل |

لاَم

[lạam] |

лям |

[l] |

30 |

| 24 | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م |

مِيم

[mīm] |

мим |

[m] |

40 |

| 25 | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن |

نُون

[nūn] |

нун |

[n] |

50 |

| 26 | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه |

هَاء

[hāʾ] |

ха |

[h] |

5 |

| 27 | ـو | و |

وَاو

[wāw] |

вав |

[w] |

6 | ||

| 28 | ـي | ـيـ | يـ | ي |

يَاء

[yāʾ] |

йа |

[y] |

10 |

Абджад

До перехода к индийским цифрам для обозначения чисел использовались буквы, и до сих пор они могут использоваться в качестве цифр при нумерации абзацев или параграфов текста. Счетный алфавит, в котором буквы следуют в порядке возрастания числового значения, называется абджад или абджадийа (أَبْجَدِيَّة [ạảb̊jadīãẗ]) — по первому слову мнемической фразы для запоминания порядка следования букв.

Дополнительные знаки

Кроме этих 28 букв в арабском письме используются еще три дополнительных знака, не являющихся самостоятельными буквами:

| # | в конце | в середине | в начале | отдельно | название | транскрипция |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ﺀ |

هَمْزَة

[ham̊zaẗ] |

хамза |

[ʾ] |

||

| ﺄ | ﺃ |

[ạ̉] |

||||

| ﺈ | ﺇ |

[ạ̹] |

||||

| ـﺆ | ﺅ |

[w̉] |

||||

| ﺊ | ـﺌـ | ﺋ | ﺉ |

[ỷ] |

||

| 2 | ﺔ | ﺓ |

تَاء مَرْبُوطَة

[tāʾ mar̊būṭaẗ] |

та марбута |

[ẗ] / [h] |

|

| 3 | ﻰ | ﻯ |

أَلِف مَقْصُورَة

[ạảlif maq̊ṣūraẗ] |

алиф максура |

[y̱] / [a] |

- Хамза (гортанная смычка) может писаться как отдельная буква, либо на букве-«подставке» (алиф, вав или йа). Способ написания хамзы определяется её контекстом в соответствии с рядом орфографических правил. Вне зависимости от способа написания, хамза всегда обозначает одинаковый звук.

- Та-марбута («завязанная та») является формой буквы та, хотя графически является буквой ха с двумя точками сверху. Служит для обозначения женского рода. Она пишется только в конце слова и только после огласовки фатха. Когда у буквы та-марбута нет огласовки (например, в конце фразы), она читается как буква ха, в остальных случаях — как т. Обычная форма буквы та называется та мафтуха (تاء مفتوحة, «открытая та»).

- Алиф-максура («укороченный алиф») является формой буквы алиф. Она пишется только в конце слова и сокращается до краткого звука а перед алиф-васла следующего слова (в частности, перед приставкой «аль»). Обычная форма буквы алиф называется алиф мамдуда (ألف ممدودة, «удлиненный алиф»).

Огласовки

Огласовки, харака, харакат (حَرَكَات [ḥarakāt] — мн.ч. от حَرَكَة [ḥarakaẗ]) — система надстрочных и подстрочных диакритических знаков, используемых в арабском письме для обозначения кратких гласных звуков и других особенностей произношения слова, не отображаемых буквами. Обычно в текстах огласовки не проставляются. Исключением являются Коран, случаи, когда это необходимо для различения смысла, детские и учебные книги, словари и т. д.

Гласные

Когда за согласным звуком следует гласный (краткий или долгий), над/под согласным ставится знак-огласовка, соответствующая следующему гласному. Если этот гласный долгий, то он дополнительно обозначается буквой алиф, вав или йа (т.н. харф мад — буква удлинения). Если после согласного звука нет гласного (перед следующим согласным либо в конце слова), то над ним ставится огласовка сукун.

- Фатха (فَتْحَة [fat̊ḥaẗ]) — черта над буквой, условно обозначает звук «а»: َ

- Дамма (ضَمَّة [ḍamãẗ]) — крючок над буквой, условно обозначает звук «у»: ُ

- Кясра (كَسْرَة [kas̊raẗ]) — черта под буквой, условно обозначает звук «и»: ِ

- Сукун (سُكُون [sukūn]) — кружок над буквой, обозначает отсутствие гласной: ْ

Русские обозначения звуков «а, и, у» условны, т.к. соответствующие огласовки могут также обозначать звуки «э», «о», или «ы».

Шадда

ّ — шадда (شَدَّة [sẖadãẗ]), или ташдид, представляет собой W-образный знак над буквой и обозначает удвоение буквы. Она ставится в двух случаях: для обозначения удвоенного согласного (то есть сочетания вида X-сукун-X), либо в сочетаниях из долгой гласной и согласной, обозначаемых одной и той же буквой (таких сочетаний два: ӣй и ӯв). Огласовка удвоенного согласного фатхой или даммой изображается над шаддой, кясрой — под буквой или под шаддой

Мадда

ٓ — мадда (مَدَّة [madãẗ]), представляет собой волнистую линию над буквой алиф и обозначает комбинацию хамза-алиф либо хамза-хамза, когда по правилам написания хамзы она пишется с подставкой алиф. Правила арабской орфографии запрещают следование в одном слове двух букв алиф подряд, поэтому в случаях, когда возникает такая комбинация букв, она заменяется буквой алиф-мадда.

Васла

Васла (وَصْلَة [waṣ̊laẗ]) представляет собой знак, похожий на букву сад. Ставится над алифом в начале слова (ٱ) и обозначает, что этот алиф не произносится, если предыдущее слово заканчивалось на гласный звук. Буква алиф-васла встречается в небольшом количестве слов, а также в приставке «аль» (ال).

Танвин

Танвин (تَنْوِين [tan̊wīn]) — удвоение в конце слова одной из трёх огласовок: ً или ٌ или ٍ . Образует падежное окончание, обозначающее неопределённое состояние.

Надстрочный алиф

ٰ — знак в форме буквы алиф над текстом, обозначает долгий звук а̄ в словах, где обычный алиф не пишется по орфографической традиции. Сюда относятся в основном имена собственные, а также несколько указательных местоимений. При полной огласовке надстрочный алиф ставится также над буквой алиф-максура, чтобы показать, что она читается как долгий а̄. Надстрочный алиф — очень редкий знак, и кроме как в Коране, он обычно не употребляется. В Коране же надстрочный алиф встречается иногда даже в тех словах, в которых по правилам пишется обычный алиф.

Цифры

В большинстве арабских стран используются индо-арабские цифры, которые сильно отличаются от известных нам арабских цифр. При этом цифры в числе пишутся, как и у нас, слева направо.

| Арабские цифры | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Индо-арабские цифры | ٠ | ١ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | ٦ | ٧ | ٨ | ٩ |

For the Arabic script as it is used by all languages, see Arabic script.

| Arabic alphabet | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

Abjad |

|

Time period |

3rd or 4th century CE to the present |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Arabic |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Arab (160), Arabic |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Arabic |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

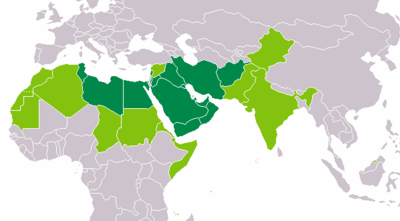

Countries that use the Arabic or Perso-Arabic script:

as the sole official script

as a co-official script

The Arabic alphabet (Arabic: الْأَبْجَدِيَّة الْعَرَبِيَّة, al-abjadīyah l-ʿarabīyah IPA: [ʔælʔæbʒædijːæ-lʕɑrɑbijːæ] or الْحُرُوف الْعَرَبِيَّة, al-ḥurūf l-ʿarabīyah), or Arabic abjad, is the Arabic script as it is codified for writing Arabic. It is written from right to left in a cursive style and includes 28 letters. Most letters have contextual letterforms.

The Arabic alphabet is considered an abjad, meaning it only uses consonants, but it is now considered an «impure abjad».[1] As with other impure abjads, such as the Hebrew alphabet, scribes later devised means of indicating vowel sounds by separate vowel diacritics.

Consonants[edit]

The basic Arabic alphabet contains 28 letters. Adaptations of the Arabic script for other languages added and removed some letters, as for example Persian, Ottoman Turkish, Kurdish, Urdu, Sindhi, Azerbaijani (in Iran), Malay, Pashto, Punjabi, Uyghur, Arwi and Arabi Malayalam, all of which have additional letters as shown below. There are no distinct upper and lower case letter forms.

Many letters look similar but are distinguished from one another by dots (ʾiʿjām) above or below their central part (rasm). These dots are an integral part of a letter, since they distinguish between letters that represent different sounds. For example, the Arabic letters ب (b), ت (t) and ث (th) have the same basic shape, but have one dot below, two dots above and three dots above, respectively. The letter ن (n) also has the same form in initial and medial forms, with one dot above, though it is somewhat different in isolated and final form.

Both printed and written Arabic are cursive, with most of the letters within a word directly connected to the adjacent letters.

Alphabetical order[edit]

There are two main collating sequences for the Arabic alphabet: abjad and hija.

The original ʾabjadīy order (أَبْجَدِيّ), used for lettering, derives from the order of the Phoenician alphabet, and is therefore similar to the order of other Phoenician-derived alphabets, such as the Hebrew alphabet. In this order, letters are also used as numbers, Abjad numerals, and possess the same alphanumeric code/cipher as Hebrew gematria and Greek isopsephy.

The hijā’ī (هِجَائِي) or alifbāʾī (أَلِفْبَائِي) order, used where lists of names and words are sorted, as in phonebooks, classroom lists, and dictionaries, groups letters by similarity of shape.

Abjadī[edit]

The ʾabjadī order is not a simple historical continuation of the earlier north Semitic alphabetic order, since it has a position corresponding to the Aramaic letter samekh/semkat ס, yet no letter of the Arabic alphabet historically derives from that letter. Loss of sameḵ was compensated for by the split of shin ש into two independent Arabic letters, ش (shīn) and ﺱ (sīn) which moved up to take the place of sameḵ. The six other letters that do not correspond to any north Semitic letter are placed at the end.

| ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي | ك | ل | م | ن | س | ع | ف | ص | ق | ر | ش | ت | ث | خ | ذ | ض | ظ | غ | ء |

| ʾ | b | j | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | s | ʿ | f | ṣ | q | r | sh | t | th | kh | dh | ḍ | ẓ | gh | ʾ |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 2000 |

This is commonly vocalized as follows:

- ʾabjad hawwaz ḥuṭṭī kalaman saʿfaṣ qarashat thakhadh ḍaẓagh.

Another vocalization is:

- ʾabujadin hawazin ḥuṭiya kalman saʿfaṣ qurishat thakhudh ḍaẓugh[citation needed]

| ا | ب | ج | د | ه | و | ز | ح | ط | ي | ك | ل | م | ن | ص | ع | ف | ض | ق | ر | س | ت | ث | خ | ذ | ظ | غ | ش | ء |

| ʾ | b | j | d | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | l | m | n | ṣ | ʿ | f | ḍ | q | r | s | t | th | kh | dh | ẓ | gh | sh | ʾ |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| The colors indicate which letters have different positions from the previous table |

This can be vocalized as:

- ʾabujadin hawazin ḥuṭiya kalman ṣaʿfaḍ qurisat thakhudh ẓaghush or *Abujadin hawazin h’ut(o)iya kalman s(w)åfad q(o)urisat t(s/h)akhudh z(h/w)ag(gh)ush

hijāʾī[edit]

Modern dictionaries and other reference books do not use the abjadī order to sort alphabetically; instead, the newer hijāʾī order is used wherein letters are partially grouped together by similarity of shape. The hijāʾī order is never used as numerals.

| ا | ب | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | ل | م | ن | ه | و | ي | ء |

| ʾ | b | t | th | j | ḥ | kh | d | dh | r | z | s | sh | ṣ | ḍ | ṭ | ẓ | ʿ | gh | f | q | k | l | m | n | h | w | y | ʾ |

Another kind of hijāʾī order was used widely in the Maghreb until recently[when?] when it was replaced by the Mashriqi order.[2]

| ا | ب | ت | ث | ج | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ط | ظ | ك | ل | م | ن | ص | ض | ع | غ | ف | ق | س | ش | ه | و | ي | ء |

| ʾ | b | t | th | j | ḥ | kh | d | dh | r | z | ṭ | ẓ | k | l | m | n | ṣ | ḍ | ʿ | gh | f | q | s | sh | h | w | y | ʾ |

| The colors indicate which letters have different positions from the previous table |

Letter forms[edit]

The Arabic alphabet is always cursive and letters vary in shape depending on their position within a word. Letters can exhibit up to four distinct forms corresponding to an initial, medial (middle), final, or isolated position (IMFI). While some letters show considerable variations, others remain almost identical across all four positions. Generally, letters in the same word are linked together on both sides by short horizontal lines, but six letters (و ,ز ,ر ,ذ ,د ,ا) can only be linked to their preceding letter. For example, أرارات (Ararat) has only isolated forms because each letter cannot be connected to its following one. In addition, some letter combinations are written as ligatures (special shapes), notably lām-alif لا,[3] which is the only mandatory ligature (the un-ligated combination لا is considered difficult to read).

Table of basic letters[edit]

| Common | Maghrebian | Letter name (Classical pronunciation) |

Letter name in Arabic script |

Trans- literation |

Value in Literary Arabic (IPA) | Closest English equivalent in pronunciation | Contextual forms | Isolated form |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾAbjadī | Hijāʾī | ʾAbjadī | Hijāʾī | Final | Medial | Initial | ||||||

| 1. | 1. | 1. | 1. | ʾalif | أَلِف | ʾ | /ʔ/[a] | car, cat | ـا | ا | ||

| 2. | 2. | 2. | 2. | bāʾ/bah | بَاء/بَه | b | /b/[b] | barn | ـب | ـبـ | بـ | ب |

| 22. | 3. | 22. | 3. | tāʾ/tah | تَاء/تَه | t | /t/ | table or stick | ـت | ـتـ | تـ | ت |

| 23. | 4. | 23. | 4. | thāʾ/thah | ثَاء/ثَه | th

(also ṯ ) |

/θ/ | think | ـث | ـثـ | ثـ | ث |

| 3. | 5. | 3. | 5. | jīm | جِيم | j

(also ǧ ) |

/d͡ʒ/[b][c] | gem | ـج | ـجـ | جـ | ج |

| 8. | 6. | 8. | 6. | ḥāʾ/ḥah | حَاء/حَه | ḥ

(also ḩ ) |

/ħ/ | no equivalent

(pharyngeal h, may be approximated as a whispered hat) |

ـح | ـحـ | حـ | ح |

| 24. | 7. | 24. | 7. | khāʾ/khah | خَاء/خَه | kh

(also ḫ, ḵ, ẖ ) |

/x/ | Scottish loch | ـخ | ـخـ | خـ | خ |

| 4. | 8. | 4. | 8. | dāl/dāʾ/dah | دَال/دَاء/دَه | d | /d/ | dear | ـد | د | ||

| 25. | 9. | 25. | 9. | dhāl/dhāʾ/dhah | ذَال/ذَاء/ذَه | dh

(also ḏ ) |

/ð/ | that | ـذ | ذ | ||

| 20. | 10. | 20. | 10. | rāʾ/rah | رَاء/رَه | r | /r/ | Scottish English curd, Spanish rolled r as in perro | ـر | ر | ||

| 7. | 11. | 7. | 11. | zāy/zayn/zāʾ/zah | زَاي/زَين/زَاء/زَه | z | /z/ | zebra | ـز | ز | ||

| 15. | 12. | 21. | 24. | sīn | سِين | s | /s/ | sin | ـس | ـسـ | سـ | س |

| 21. | 13. | 28. | 25. | shīn | شِين | sh

(also š ) |

/ʃ/ | shin | ـش | ـشـ | شـ | ش |

| 18. | 14. | 15. | 18. | ṣād | صَاد | ṣ

(also ş ) |

/sˤ/ | no equivalent

(can be approximated with sauce, but with the throat constricted) |

ـص | ـصـ | صـ | ص |

| 26. | 15. | 18. | 19. | ḍād/ḍāʾ/ḍah | ضَاد/ضَاء/ضَه | ḍ

(also ḑ ) |

/dˤ/ | no equivalent

(can be approximated with dawn, but with the throat constricted) |

ـض | ـضـ | ضـ | ض |

| 9. | 16. | 9. | 12. | ṭāʾ/ṭah | طَاء/طَه | ṭ

(also ţ ) |

/tˤ/ | no equivalent

(can be approximated with table, but with the throat constricted) |

ـط | ـطـ | طـ | ط |

| 27. | 17. | 26. | 13. | ẓāʾ/ẓah | ظَاء/ظَه | ẓ

(also z̧ ) |

/ðˤ/ | no equivalent

(can be approximated with either, but with the throat constricted) |

ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ | ظ |

| 16. | 18. | 16. | 20. | ʿayn | عَيْن | ʿ | /ʕ/ | no equivalent

(similar to ḥāʾ above, but voiced) |

ـع | ـعـ | عـ | ع |

| 28. | 19. | 27. | 21. | ghayn | غَيْن | gh

(also ġ, ḡ ) |

/ɣ/[b] | no equivalent

(Spanish abogado) |

ـغ | ـغـ | غـ | غ |

| 17. | 20. | 17. | 22. | fāʾ/fah | فَاء/فَه | f | /f/[b] | far | ـف | ـفـ | فـ | ف[d] |

| 19. | 21. | 19. | 23. | qāf | قَاف | q | /q/[b] | MLE cut | ـق | ـقـ | قـ | ق[d] |

| 11. | 22. | 11. | 14. | kāf/kāʾ/kah | كَاف/كَاء/كَه | k | /k/[b] | cap | ـك/ـڪ | ـكـ/ـڪـ | كـ/ڪـ | ك/ڪ[d] |

| 12. | 23. | 12. | 15. | lām | لاَم | l | /l/ | lamp | ـل | ـلـ | لـ | ل |

| 13. | 24. | 13. | 16. | mīm | مِيم | m | /m/ | me | ـم | ـمـ | مـ | م |

| 14. | 25. | 14. | 17. | nūn | نُون | n | /n/ | nun | ـن | ـنـ | نـ | ن |

| 5. | 26. | 5. | 26. | hāʾ/hah | هَاء/هَه | h | /h/ | hat | ـه | ـهـ | هـ | ه |

| 6. | 27. | 6. | 27. | wāw | وَاو | w / ū / ∅ | /w/, /uː/, ∅[b] | wet, pool | ـو | و | ||

| 10. | 28. | 10. | 28. | yāʾ/yah | يَاء/يَه | y / ī | /j/, /iː/[b] | Yoshi, meet | ـي/ـے | ـيـ | يـ | ي/ے[d] |

| 29. | 29. | 29. | 29. | hamzah | هَمْزة | ʾ | /ʔ/ | uh–oh | ء[e]

(used in medial and final positions as an unlinked letter) |

|||

| ʾalif hamzah | أَلِف هَمْزة | ـأ/ـٵ | أ/ٵ | |||||||||

| ـإ | إ | |||||||||||

| wāw hamzah | وَاو هَمْزة | ـؤ/ـٶ | ؤ/ٶ | |||||||||

| yāʾ hamzah/yah hamzah | يَاء هَمْزة/يَه هَمْزة | ئ/ـٸ/ـࢨ/ـۓ | ـئـ/ـٸـ/ـࢨـ | ئـ/ٸـ/ࢨـ | ئ/ٸ/ࢨ/ۓ | |||||||

| ʾalif maddah | أَلِف مَدَّة | ā | /aː/ | ـآ | آ | |||||||

| [f] | tāʾ marbūṭah/tah marbūṭah | تاء مربوطة/ته مربوطة | ـة | (end only)[citation needed] | ة | |||||||

| [g] | ʾalif maqṣūrah | الف مقصورة | ـى | ـىـ | ىـ | ى |

Notes

- ^ Alif can represent many phonemes. See the section on ʾalif.

- ^ a b c d e f g h See the section on non-native letters and sounds; the letters ⟨ك⟩ ,⟨ق⟩ ,⟨غ⟩ ,⟨ج⟩ are sometimes used to transcribe the phoneme /ɡ/ in loanwords, ⟨ب⟩ to transcribe /p/ and ⟨ف⟩ to transcribe /v/. Likewise the letters ⟨و⟩ and ⟨ي⟩ are used to transcribe the vowels /oː/ and /eː/ respectively in loanwords and dialects.

- ^ ج is pronounced differently depending on the region. See Arabic phonology#Consonants.

- ^ a b c d See the section on regional variations in letter form.

- ^ (counted as a letter in the alphabet and plays an important role in Arabic spelling) denoting most irregular female nouns[citation needed]

- ^ (not counted as a letter in the alphabet but plays an important role in Arabic grammar and lexicon, including indication [denoting most female nouns] and spelling) An alternative form of ت («bound tāʼ » / تاء مربوطة) is used at the end of words to mark feminine gender for nouns and adjectives. It denotes the final sound /-h/ or /-t/. Standard tāʼ, to distinguish it from tāʼ marbūṭah, is referred to as tāʼ maftūḥah (تاء مفتوحة, «open tāʼ «).

- ^ (not counted as a letter in the alphabet but plays an important role in Arabic grammar and lexicon, including indication [denotes verbs] and spelling). It is used at the end of words with the sound of /aː/ in Modern Standard Arabic that are not categorized in the use of tāʼ marbūṭah (ة) [mainly some verbs tenses and Arabic masculine names].

- See the article Romanization of Arabic for details on various transliteration schemes. Arabic language speakers may usually not follow a standardized scheme when transcribing words or names. Some Arabic letters which don’t have an equivalent in English (such as ق) are often spelled as numbers when Romanized. Also names are regularly transcribed as pronounced locally, not as pronounced in Literary Arabic (if they were of Arabic origin).

- Regarding pronunciation, the phonemic values given are those of Modern Standard Arabic, which is taught in schools and universities. In practice, pronunciation may vary considerably from region to region. For more details concerning the pronunciation of Arabic, consult the articles Arabic phonology and varieties of Arabic.

- The names of the Arabic letters can be thought of as abstractions of an older version where they were meaningful words in the Proto-Semitic language. Names of Arabic letters may have quite different names popularly.

- Six letters (و ز ر ذ د ا) do not have a distinct medial form and have to be written with their final form without being connected to the next letter. Their initial form matches the isolated form. The following letter is written in its initial form, or isolated form if it is the final letter in the word.

- The letter alif originated in the Phoenician alphabet as a consonant-sign indicating a glottal stop. Today it has lost its function as a consonant, and, together with ya’ and wāw, is a mater lectionis, a consonant sign standing in for a long vowel (see below), or as support for certain diacritics (maddah and hamzah).

- Arabic currently uses a diacritic sign, ء, called hamzah, to denote the glottal stop [ʔ], written alone or with a carrier:

- alone: ء

- with a carrier: إ أ (above or under an alif), ؤ (above a wāw), ئ (above a dotless yā’ or yā’ hamzah).

- In academic work, the hamzah (ء) is transliterated with the modifier letter right half ring (ʾ), while the modifier letter left half ring (ʿ) transliterates the letter ‘ayn (ع), which represents a different sound, not found in English.

-

- The hamzah has a single form, since it is never linked to a preceding or following letter. However, it is sometimes combined with a wāw, yā’, or alif, and in that case the carrier behaves like an ordinary wāw, yā’, or alif.

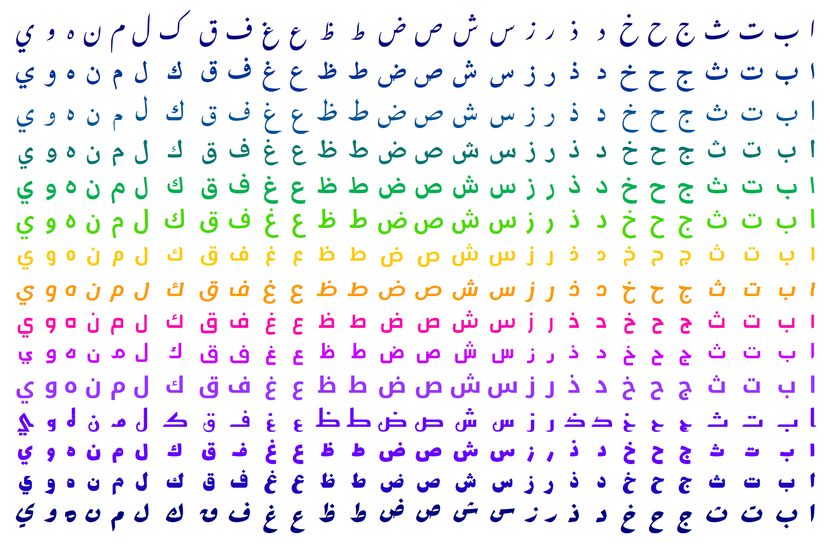

Variations[edit]

| ي و ه ن م ل ك ق ف غ ع ظ ط ض ص ش س ز ر ذ د خ ح ج ث ت ب ا | hijā’ī sequence | |

|

|

• | Noto Nastaliq Urdu |

| • | Scheherazade New | |

| • | Lateef | |

| • | Noto Naskh Arabic | |

| • | Markazi Text | |

| • | Noto Sans Arabic | |

| • | El Messiri | |

| • | Lemonada | |

| • | Changa | |

| • | Mada | |

| • | Noto Kufi Arabic | |

| • | Reem Kufi | |

| • | Lalezar | |

| • | Jomhuria | |

| • | Rakkas | |

| غ ظ ض ذ خ ث ت ش ر ق ص ف ع س ن م ل ك ي ط ح ز و ه د ج ب ا | abjadī sequence | |

|

|

• | Noto Nastaliq Urdu |

| • | Scheherazade New | |

| • | Lateef | |

| • | Noto Naskh Arabic | |

| • | Markazi Text | |

| • | Noto Sans Arabic | |

| • | El Messiri | |

| • | Lemonada | |

| • | Changa | |

| • | Mada | |

| • | Noto Kufi Arabic | |

| • | Reem Kufi | |

| • | Lalezar | |

| • | Jomhuria | |

| • | Rakkas |

Alif[edit]

| Context | Form | Value | Closest English Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without diacritics | ا |

|

|

| With hamzah over

(hamzah alif) |

أ/ٵ |

|

|

| With hamzah under

(hamzah alif) |

إ |

|

|

| With maddah | آ |

|

|

| With waslah | ٱ |

|

|

Modified letters[edit]

The following are not individual letters, but rather different contextual variants of some of the Arabic letters.

| Conditional forms | Name | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | |||

| آ | ـآ | ʾalif maddah

(أَلِفْ مَدَّة) |

ā | /ʔaː/(aka «lengthening/ stressing ‘alif«) | ||

| ة | ـة | tāʾ marbūṭah

(تَاءْ مَرْبُوطَة) |

h or t/ẗ |

(aka «correlated tā‘«)

used in final position only and for denoting the feminine noun/word or to make the noun/word feminine; however, in rare irregular noun/word cases, it appears to denote the «masculine»; plural nouns: āt (a preceding letter followed by a fatḥah alif + tāʾ = ـَات) |

||

| ى | ـى | ـىـ | ىـ | ʾalif maqṣūrah (أَلِفْ مَقْصُورَة) | á or y/ỳ |

Two uses:

1. The letter called أَلِفْ مَقْصُورَة alif maqṣūrah or ْأَلِف لَيِّنَة alif layyinah, pronounced /aː/ in Modern Standard Arabic. It is used only at the end of words in some special cases to denote the neuter/non-feminine aspect of the word (mainly verbs), where tā’ marbūṭah cannot be used. |

Ligatures[edit]

The use of ligature in Arabic is common. There is one compulsory ligature, that for lām ل + alif ا, which exists in two forms. All other ligatures, of which there are many,[4] are optional.

| Contextual forms | Name | Trans. | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final | Medial | Initial | Isolated | |||

| ﻼ | ﻻ | lām + alif | laa | /laː/ | ||

| ﲓ | ﳰ | ﳝ[5] | ﱘ | yāʾ + mīm | īm | /iːm/ |

| ﲅ | ﳭ | ﳌ | ﱂ | lam + mīm | lm | /lm/ |

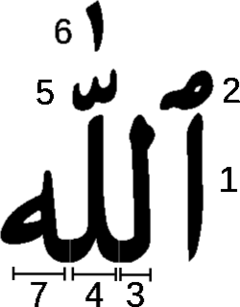

A more complex ligature that combines as many as seven distinct components is commonly used to represent the word Allāh.

The only ligature within the primary range of Arabic script in Unicode (U+06xx) is lām + alif. This is the only one compulsory for fonts and word-processing. Other ranges are for compatibility to older standards and contain other ligatures, which are optional.

- lām + alif

- لا

Note: Unicode also has in its Presentation Form B FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured correctly for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one, U+FEFB ARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF ISOLATED FORM:

-

- ﻻ

U+0640ARABIC TATWEEL + lām + alif- ـلا

Note: Unicode also has in its Presentation Form B U+FExx range a code for this ligature. If your browser and font are configured correctly for Arabic, the ligature displayed above should be identical to this one:

U+FEFCARABIC LIGATURE LAM WITH ALEF FINAL FORM- ﻼ

Another ligature in the Unicode Presentation Form A range U+FB50 to U+FDxx is the special code for glyph for the ligature Allāh («God»), U+FDF2 ARABIC LIGATURE ALLAH ISOLATED FORM:

-

- ﷲ

This is a work-around for the shortcomings of most text processors, which are incapable of displaying the correct vowel marks for the word Allāh in Koran. Because Arabic script is used to write other texts rather than Koran only, rendering lām + lām + hā’ as the previous ligature is considered faulty.

This simplified style is often preferred for clarity, especially in non-Arabic languages, but may not be considered appropriate in situations where a more elaborate style of calligraphy is preferred. –SIL International[6]

If one of a number of the fonts (Noto Naskh Arabic, mry_KacstQurn, KacstOne, Nadeem, DejaVu Sans, Harmattan, Scheherazade, Lateef, Iranian Sans, Baghdad, DecoType Naskh) is installed on a computer (Iranian Sans is supported by Wikimedia web-fonts), the word will appear without diacritics.

- lām + lām + hā’ = LILLĀH (meaning «to Allāh [only to God]»)

- لله or لله

- alif + lām + lām + hā’ = ALLĀH (the Arabic word for «god»)

- الله or الله

- alif + lām + lām +

U+0651ARABIC SHADDA +U+0670ARABIC LETTER SUPERSCRIPT ALEF + hā’- اللّٰه (DejaVu Sans and KacstOne don’t show the added superscript Alef)

An attempt to show them on the faulty fonts without automatically adding the gemination mark and the superscript alif, although may not display as desired on all browsers, is by adding the U+200d (Zero width joiner) after the first or second lām

- (alif +) lām + lām +

U+200dZERO WIDTH JOINER + hā’- الله لله

Gemination[edit]

Further information: Shadda

Gemination is the doubling of a consonant. Instead of writing the letter twice, Arabic places a W-shaped sign called shaddah, above it. Note that if a vowel occurs between the two consonants the letter will simply be written twice. The diacritic only appears where the consonant at the end of one syllable is identical to the initial consonant of the following syllable. (The generic term for such diacritical signs is ḥarakāt).

| General Unicode | Name | Name in Arabic script | Transliteration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0651 |

ــّـ |

shaddah | شَدَّة | (consonant doubled) |

Nunation[edit]

Nunation (Arabic: تنوين tanwīn) is the addition of a final -n to a noun or adjective. The vowel before it indicates grammatical case. In written Arabic nunation is indicated by doubling the vowel diacritic at the end of the word.

Vowels[edit]

Users of Arabic usually write long vowels but omit short ones, so readers must utilize their knowledge of the language in order to supply the missing vowels. However, in the education system and particularly in classes on Arabic grammar these vowels are used since they are crucial to the grammar. An Arabic sentence can have a completely different meaning by a subtle change of the vowels. This is why in an important text such as the Qur’ān the three basic vowel signs (see below) are mandated, like the ḥarakāt and all the other diacritics or other types of marks, for example the cantillation signs.

Short vowels[edit]

In the Arabic handwriting of everyday use, in general publications, and on street signs, short vowels are typically not written. On the other hand, copies of the Qur’ān cannot be endorsed by the religious institutes that review them unless the diacritics are included. Children’s books, elementary school texts, and Arabic-language grammars in general will include diacritics to some degree. These are known as «vocalized» texts.

Short vowels may be written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable, called ḥarakāt. All Arabic vowels, long and short, follow a consonant; in Arabic, words like «Ali» or «alif», for example, start with a consonant: ‘Aliyy, alif.

| Short vowels (fully vocalized text) |

Code | Name | Name in Arabic script | Trans. | Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ــَـ | 064E | fat·ḥah | فَتْحَة | a | /a/ | Ranges from [æ], [a], [ä], [ɑ], [ɐ], to [e], depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. |

| ــُـ | 064F | ḍammah | ضَمَّة | u | /u/ | Ranges from [ʊ], [o], to [u], depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. Approximated to English «OO» (as «boot» but shorter) |

|

ــِـ |

0650 | kasrah | كَسْرَة | i | /i/ | Ranges from [ɪ], [e], to [i], depending on the native dialect, position, and stress. Approximated to English «I» (as in «pick») |

Long vowels[edit]

In the fully vocalized Arabic text found in texts such as Quran, a long ā following a consonant other than a hamzah is written with a short a sign (fatḥah) on the consonant plus an ʾalif after it; long ī is written as a sign for short i (kasrah) plus a yāʾ; and long ū as a sign for short u (ḍammah) plus a wāw. Briefly, ᵃa = ā; ⁱy = ī; and ᵘw = ū. Long ā following a hamzah may be represented by an ʾalif maddah or by a free hamzah followed by an ʾalif (two consecutive ʾalifs are never allowed in Arabic).

The table below shows vowels placed above or below a dotted circle replacing a primary consonant letter or a shaddah sign. For clarity in the table, the primary letters on the left used to mark these long vowels are shown only in their isolated form. Most consonants do connect to the left with ʾalif, wāw and yāʾ written then with their medial or final form. Additionally, the letter yāʾ in the last row may connect to the letter on its left, and then will use a medial or initial form. Use the table of primary letters to look at their actual glyph and joining types.

| Unicode | Letter with diacritic | Name | Trans. | Variants | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 064E 0627 | ـَـا | fatḥah ʾalif | ā | aa | /aː/ |

| 064E 0649 | ـَـىٰ | fatḥah ʾalif maqṣūrah | ā | aa | |

| 0650 0649 | ـِـىٖ | kasrah ʾalif maqṣūrah | y | iy | /iː/ |

| 064F 0648 | ـُـو | ḍammah wāw | ū | uw/ ou | /uː/ |

| 0650 064A | ـِـي | kasrah yāʾ | ī | iy | /iː/ |

In unvocalized text (one in which the short vowels are not marked), the long vowels are represented by the vowel in question: ʾalif ṭawīlah/maqṣūrah, wāw, or yāʾ. Long vowels written in the middle of a word of unvocalized text are treated like consonants with a sukūn (see below) in a text that has full diacritics. Here also, the table shows long vowel letters only in isolated form for clarity.

Combinations وا and يا are always pronounced wā and yāʾ respectively. The exception is the suffix ـوا۟ in verb endings where ʾalif is silent, resulting in ū or aw.

| Long vowels (unvocalized text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0627 ا |

(implied fatḥah) ʾalif | ā | /aː/ |

| 0649 ى |

(implied fatḥah) ʾalif maqṣūrah | ā / y | |

| 0648 و |

(implied ḍammah) wāw | ū | /uː/ |

| 064A ي |

(implied kasrah) yāʾ | ī | /iː/ |

In addition, when transliterating names and loanwords, Arabic language speakers write out most or all the vowels as long (ā with ا ʾalif, ē and ī with ي yaʾ, and ō and ū with و wāw), meaning it approaches a true alphabet.

Diphthongs[edit]

The diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ are represented in vocalized text as follows:

| Diphthongs (fully vocalized text) |

Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 064A 064E ـَـي |

fatḥah yāʾ | ay | /aj/ |

| 0648 064E ـَـو |

fatḥah wāw | aw | /aw/ |

Vowel omission[edit]

An Arabic syllable can be open (ending with a vowel) or closed (ending with a consonant):

- open: CV [consonant-vowel] (long or short vowel)

- closed: CVC (short vowel only)

A normal text is composed only of a series of consonants plus vowel-lengthening letters; thus, the word qalb, «heart», is written qlb, and the word qalaba «he turned around», is also written qlb.

To write qalaba without this ambiguity, we could indicate that the l is followed by a short a by writing a fatḥah above it.

To write qalb, we would instead indicate that the l is followed by no vowel by marking it with a diacritic called sukūn ( ْ), like this: قلْب.

This is one step down from full vocalization, where the vowel after the q would also be indicated by a fatḥah: قَلْب.

The Qurʾān is traditionally written in full vocalization.

The long i sound in some editions of the Qur’ān is written with a kasrah followed by a diacritic-less y, and long u by a ḍammah followed by a bare w. In others, these y and w carry a sukūn. Outside of the Qur’ān, the latter convention is extremely rare, to the point that y with sukūn will be unambiguously read as the diphthong /aj/, and w with sukūn will be read /aw/.

For example, the letters m-y-l can be read like English meel or mail, or (theoretically) also like mayyal or mayil. But if a sukūn is added on the y then the m cannot have a sukūn (because two letters in a row cannot be sukūnated), cannot have a ḍammah (because there is never an uy sound in Arabic unless there is another vowel after the y), and cannot have a kasrah (because kasrah before sukūnated y is never found outside the Qur’ān), so it must have a fatḥah and the only possible pronunciation is /majl/ (meaning mile, or even e-mail). By the same token, m-y-t with a sukūn over the y can be mayt but not mayyit or meet, and m-w-t with a sukūn on the w can only be mawt, not moot (iw is impossible when the w closes the syllable).

Vowel marks are always written as if the i‘rāb vowels were in fact pronounced, even when they must be skipped in actual pronunciation. So, when writing the name Aḥmad, it is optional to place a sukūn on the ḥ, but a sukūn is forbidden on the d, because it would carry a ḍammah if any other word followed, as in Aḥmadu zawjī «Ahmad is my husband».

Another example: the sentence that in correct literary Arabic must be pronounced Aḥmadu zawjun shirrīr «Ahmad is a wicked husband», is usually mispronounced (due to influence from vernacular Arabic varieties) as Aḥmad zawj shirrīr. Yet, for the purposes of Arabic grammar and orthography, is treated as if it were not mispronounced and as if yet another word followed it, i.e., if adding any vowel marks, they must be added as if the pronunciation were Aḥmadu zawjun sharrīrun with a tanwīn ‘un’ at the end. So, it is correct to add an un tanwīn sign on the final r, but actually pronouncing it would be a hypercorrection. Also, it is never correct to write a sukūn on that r, even though in actual pronunciation it is (and in correct Arabic MUST be) sukūned.

Of course, if the correct i‘rāb is a sukūn, it may be optionally written.

| General Unicode | Name | Name in Arabic script | Translit. | Phonemic Value (IPA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0652 | ــْـ | sukūn | سُكُون | (no vowel with this consonant letter or diphthong with this long vowel letter) |

∅ |

| 0670 | ــٰـ | alif khanjariyyah [dagger ’alif — smaller ’alif written above consonant] | أَلِف خَنْجَرِيَّة | ā | /aː/ |

ٰٰ

The sukūn is also used for transliterating words into the Arabic script. The Persian word ماسک (mâsk, from the English word «mask»), for example, might be written with a sukūn above the ﺱ to signify that there is no vowel sound between that letter and the ک.

Additional letters[edit]

Regional variations[edit]

Some letters take a traditionally different form in specific regions:

| Letter | Explanation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial | |

| ڛ | ـڛ | ـڛـ | ڛـ | A traditional form to denotate the sīn س letter, used in areas influenced by Persian script and former Ottoman script, although rarely. Also used in older Pashto script.[7] |

| ڢ | ـڢ | ـڢـ | ڢـ | A traditional Maghrebi variant (except for Libya and Algeria) of fā’ ف. |

| ڧ/ٯ | ـڧ/ـٯ | ـڧـ/ـٯـ | ڧـ/ٯـ | A traditional Maghrebi variant (except for Libya and Algeria) of qāf ق. Generally dotless in isolated and final positions and dotted in the initial and medial forms. |

| ک | ـک | ـکـ | کـ | An alternative version of kāf ك used especially in Maghrebi under the influence of the Ottoman script or in Gulf script under the influence of the Persian script. |

| ی | ـی | ـیـ | یـ | The traditional style to write or print the letter, and remains so in the Nile Valley region (Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan… etc.) and sometimes Maghreb; yā’ ي is dotless in the isolated and final position. Visually identical to alif maqṣūrah ى; resembling the Perso-Arabic letter یـ ـیـ ـی ی which was also used in Ottoman Turkish. |

Non-native letters to Standard Arabic[edit]

Some modified letters are used to represent non-native sounds of Modern Standard Arabic. These letters are used in transliterated names, loanwords and dialectal words.

| Letter | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Foreign letters | ||

| پ | /p/ | It is a Persian letter. Sometimes used in Arabic as well when transliterating foreign names and loanwords. Can be substituted with bā’ ب and pronounced as such. |

| ڤ | /v/ | Used in loanwords and dialectal words instead of fā’ ف.[8] Not to be confused with ڨ. |

| ڥ | Used in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. | |

| چ | /t͡ʃ/1 | It is a Persian letter. Sometimes used in Arabic as well when transliterating foreign names and loanwords and in the Gulf and Arabic dialects. The sequence تش tāʼ-shīn is usually preferred (e.g. تشاد for «Chad»). |

| /ʒ/2 | Used in Egypt and can be a reduction of /d͡ʒ/, where ج is pronounced /ɡ/. | |

| /ɡ/3 | Used in Israel, for example on road signs. | |

| گ | It is a Persian letter. Sometimes used in Arabic as well. | |

| ڨ | Used in Tunisia and in Algeria for loanwords and for the dialectal pronunciation of qāf ق in some words. Not to be confused with ڤ. | |

| ڭ/ݣ | Used in Morocco. |

- /t͡ʃ/ is considered a native phoneme/allophone in some dialects, e.g. Kuwaiti and Iraqi dialects.

- /ʒ/ is considered a native phoneme in Levantine and North African dialects and as an allophone in others.

- /ɡ/ is considered a native phoneme/allophone in most modern Arabic dialects.

Used in languages other than Arabic[edit]

Numerals[edit]

| Western (Maghreb, Europe) |

Central (Mideast) |

Eastern | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persian | Urdu | ||

| 0 | ٠ | ۰ | ۰ |

| 1 | ١ | ۱ | ۱ |

| 2 | ٢ | ۲ | ۲ |

| 3 | ٣ | ۳ | ۳ |

| 4 | ٤ | ۴ | ۴ |

| 5 | ٥ | ۵ | ۵ |

| 6 | ٦ | ۶ | ۶ |

| 7 | ٧ | ۷ | ۷ |

| 8 | ٨ | ۸ | ۸ |

| 9 | ٩ | ۹ | ۹ |

| 10 | ١٠ | ۱۰ | ۱۰ |

There are two main kinds of numerals used along with Arabic text; Western Arabic numerals and Eastern Arabic numerals. In most of present-day North Africa, the usual Western Arabic numerals are used. Like Western Arabic numerals, in Eastern Arabic numerals, the units are always right-most, and the highest value left-most. Eastern Arabic numbers are written from left to right.

Letters as numerals[edit]

In addition, the Arabic alphabet can be used to represent numbers (Abjad numerals). This usage is based on the ʾabjadī order of the alphabet. أ ʾalif is 1, ب bāʾ is 2, ج jīm is 3, and so on until ي yāʾ = 10, ك kāf = 20, ل lām = 30, …, ر rāʾ = 200, …, غ ghayn = 1000. This is sometimes used to produce chronograms.

History[edit]

Evolution of early Arabic calligraphy (9th–11th century). The Basmala is taken as an example, from Kufic Qur’ān manuscripts. (1) Early 9th century script used no dots or diacritic marks;[9] (2) and (3) in the 9th–10th century during the Abbasid dynasty, Abu al-Aswad’s system used red dots with each arrangement or position indicating a different short vowel. Later, a second system of black dots was used to differentiate between letters like fā’ and qāf;[10] (4) in the 11th century (al-Farāhīdī’s system) dots were changed into shapes resembling the letters to transcribe the corresponding long vowels. This system is the one used today.[11]

The Arabic alphabet can be traced back to the Nabataean alphabet used to write Nabataean. The first known text in the Arabic alphabet is a late 4th-century inscription from Jabal Ramm (50 km east of ‘Aqabah) in Jordan, but the first dated one is a trilingual inscription at Zebed in Syria from 512.[citation needed] However, the epigraphic record is extremely sparse, with only five certainly pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions surviving, though some others may be pre-Islamic. Later, dots were added above and below the letters to differentiate them. (The Aramaic language had fewer phonemes than the Arabic, and some originally distinct Aramaic letters had become indistinguishable in shape, so that in the early writings 15 distinct letter-shapes had to do duty for 29 sounds; cf. the similarly ambiguous Pahlavi alphabet.) The first surviving document that definitely uses these dots is also the first surviving Arabic papyrus (PERF 558), dated April 643, although they did not become obligatory until much later. Important texts were and still are frequently memorized, especially in Qurʾan memorization.

Later still, vowel marks and the hamzah were introduced, beginning some time in the latter half of the 7th century, preceding the first invention of Syriac and Hebrew vocalization. Initially, this was done by a system of red dots, said to have been commissioned in the Umayyad era by Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali a dot above = a, a dot below = i, a dot on the line = u, and doubled dots indicated nunation. However, this was cumbersome and easily confusable with the letter-distinguishing dots, so about 100 years later, the modern system was adopted. The system was finalized around 786 by al-Farāhīdī.

Arabic printing[edit]

Medieval Arabic blockprinting flourished from the 10th century until the 14th. It was devoted only to very small texts, usually for use in amulets.

In 1514, following Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in 1450, Gregorio de Gregorii, a Venetian, published an entire prayer-book in Arabic script; it was entitled Kitab Salat al-Sawa’i and was intended for eastern Christian communities.[12]

Between 1580 and 1586, type designer Robert Granjon designed Arabic typefaces for Cardinal Ferdinando de’ Medici, and the Medici press published many Christian prayer and scholarly Arabic texts in the late 16th century.[13]

Maronite monks at the Maar Quzhayy Monastery in Mount Lebanon published the first Arabic books to use movable type in the Middle East. The monks transliterated the Arabic language using Syriac script.

Although Napoleon Bonaparte generally receives credit for introducing the printing press to Egypt during his invasion of that country in 1798, and though he did indeed bring printing presses and Arabic script presses to print the French occupation’s official newspaper Al-Tanbiyyah («The Courier»), printing in the Arabic language started several centuries earlier.

A goldsmith (like Gutenberg) designed and implemented an Arabic-script movable-type printing-press in the Middle East. The Greek Orthodox monk Abd Allah Zakhir set up an Arabic printing press using movable type at the monastery of Saint John at the town of Dhour El Shuwayr in Mount Lebanon, the first homemade press in Lebanon using Arabic script. He personally cut the type molds and did the founding of the typeface. The first book came off his press in 1734; this press continued in use until 1899.[14]

Computers[edit]

The Arabic alphabet can be encoded using several character sets, including ISO-8859-6, Windows-1256 and Unicode (see links in Infobox above), latter thanks to the «Arabic segment», entries U+0600 to U+06FF. However, none of the sets indicates the form that each character should take in context. It is left to the rendering engine to select the proper glyph to display for each character.

Each letter has a position-independent encoding in Unicode, and the rendering software can infer the correct glyph form (initial, medial, final or isolated) from its joining context. That is the current recommendation. However, for compatibility with previous standards, the initial, medial, final and isolated forms can also be encoded separately.

Unicode[edit]

As of Unicode 15.0, the Arabic script is contained in the following blocks:[15]

- Arabic (0600–06FF, 256 characters)

- Arabic Supplement (0750–077F, 48 characters)

- Arabic Extended-A (08A0–08FF, 96 characters)

- Arabic Extended-B (0870–089F, 41 characters)

- Arabic Extended-C (10EC0–10EFF, 3 characters)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-A (FB50–FDFF, 631 characters)

- Arabic Presentation Forms-B (FE70–FEFF, 141 characters)

- Rumi Numeral Symbols (10E60–10E7F, 31 characters)

- Indic Siyaq Numbers (1EC70–1ECBF, 68 characters)

- Ottoman Siyaq Numbers (1ED00–1ED4F, 61 characters)

- Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols (1EE00—1EEFF, 143 characters)

The basic Arabic range encodes the standard letters and diacritics but does not encode contextual forms (U+0621-U+0652 being directly based on ISO 8859-6). It also includes the most common diacritics and Arabic-Indic digits. U+06D6 to U+06ED encode Qur’anic annotation signs such as «end of ayah» ۖ and «start of rub el hizb» ۞. The Arabic supplement range encodes letter variants mostly used for writing African (non-Arabic) languages. The Arabic Extended-A range encodes additional Qur’anic annotations and letter variants used for various non-Arabic languages.

The Arabic Presentation Forms-A range encodes contextual forms and ligatures of letter variants needed for Persian, Urdu, Sindhi and Central Asian languages. The Arabic Presentation Forms-B range encodes spacing forms of Arabic diacritics, and more contextual letter forms. The Arabic Mathematical Alphabetical Symbols block encodes characters used in Arabic mathematical expressions.

See also the notes of the section on modified letters.

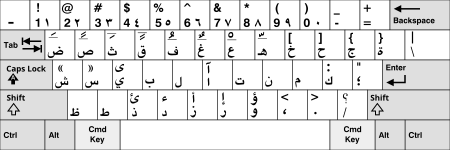

Keyboards[edit]

Arabic Mac keyboard layout

Arabic PC keyboard layout

Intellark imposed on a QWERTY keyboard layout

Keyboards designed for different nations have different layouts, so proficiency in one style of keyboard, such as Iraq’s, does not transfer to proficiency in another, such as Saudi Arabia’s. Differences can include the location of non-alphabetic characters.

All Arabic keyboards allow typing Roman characters, e.g., for the URL in a web browser. Thus, each Arabic keyboard has both Arabic and Roman characters marked on the keys. Usually, the Roman characters of an Arabic keyboard conform to the QWERTY layout, but in North Africa, where French is the most common language typed using the Roman characters, the Arabic keyboards are AZERTY.

To encode a particular written form of a character, there are extra code points provided in Unicode which can be used to express the exact written form desired. The range Arabic presentation forms A (U+FB50 to U+FDFF) contain ligatures while the range Arabic presentation forms B (U+FE70 to U+FEFF) contains the positional variants. These effects are better achieved in Unicode by using the zero-width joiner and zero-width non-joiner, as these presentation forms are deprecated in Unicode and should generally only be used within the internals of text-rendering software; when using Unicode as an intermediate form for conversion between character encodings; or for backwards compatibility with implementations that rely on the hard-coding of glyph forms.

Finally, the Unicode encoding of Arabic is in logical order, that is, the characters are entered, and stored in computer memory, in the order that they are written and pronounced without worrying about the direction in which they will be displayed on paper or on the screen. Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction, using Unicode’s bi-directional text features. In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out of date.[16][17]

There are competing online tools, e.g. Yamli editor, which allow entry of Arabic letters without having Arabic support installed on a PC, and without knowledge of the layout of the Arabic keyboard.[18]

Handwriting recognition[edit]

The first software program of its kind in the world that identifies Arabic handwriting in real time was developed by researchers at Ben-Gurion University (BGU).

The prototype enables the user to write Arabic words by hand on an electronic screen, which then analyzes the text and translates it into printed Arabic letters in a thousandth of a second. The error rate is less than three percent, according to Dr. Jihad El-Sana, from BGU’s department of computer sciences, who developed the system along with master’s degree student Fadi Biadsy.[19]

See also[edit]

- Abjad numerals

- Ancient South Arabian script

- Algerian braille

- Arabic braille

- Arabic calligraphy

- Arabic chat alphabet

- Arabic diacritics

- Arabic letter frequency

- Arabic Mathematical Alphabetic Symbols

- Arabic numerals

- Arabic phonology

- Arabic script – about other languages written in Arabic script

- ArabTeX – provides Arabic support for TeX and LaTeX

- Kufic

- Modern Arabic mathematical notation

- Perso-Arabic script

- Rasm

- Romanization of Arabic

References[edit]

- ^ Zitouni, Imed (2014). Natural Language Processing of Semitic Languages. Springer Science & Business. p. 15. ISBN 978-3642453588.

- ^ a b (in Arabic) Alyaseer.net ترتيب المداخل والبطاقات في القوائم والفهارس الموضوعية Ordering entries and cards in subject indexes Archived 23 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Discussion thread (Accessed 2009-October–06)

- ^ Rogers, Henry (2005). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Blackwell Publishing. p. 135.

- ^ «A list of Arabic ligature forms in Unicode».

- ^ Depending on fonts used for rendering, the form shown on-screen may or may not be the ligature form.

- ^ «Scheherazade New». SIL International. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Notice sur les divers genres d’écriture ancienne et moderne des arabes, des persans et des turcs / par A.-P. Pihan. 1856.

- ^ «Arabic Dialect Tutorial» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ File:Basmala kufi.svg — Wikimedia Commons

- ^ File:Kufi.jpg — Wikimedia Commons

- ^ File:Qur’an folio 11th century kufic.jpg — Wikimedia Commons

- ^ «294° anniversario della Biblioteca Federiciana: ricerche e curiosità sul Kitab Salat al-Sawai». Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Naghashian, Naghi (21 January 2013). Design and Structure of Arabic Script. epubli. ISBN 9783844245059.

- ^

Arabic and the Art of Printing – A Special Section Archived 29 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, by Paul Lunde - ^ «UAX #24: Script data file». Unicode Character Database. The Unicode Consortium.