This article is about the tenth letter of the Latin alphabet. For other uses, see J (disambiguation).

| J | |

|---|---|

| J j ȷ | |

| (See below) | |

|

|

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage | [j] [dʒ]~[tʃ] [x~h] [ʒ] [ɟ] [ʝ] [dz] [tɕ] [gʱ] [t]~[dʑ] [ʐ] [ʃ] [c̬] [i] |

| Unicode codepoint | U+004A, U+006A, U+0237 |

| Alphabetical position | 10 |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Time period | 1524 to present |

| Descendants | • Ɉ • Tittle • J |

| Sisters | І Ј י ي ܝ ی ࠉ 𐎊 ዪ Ⴢ ⴢ ჲ ☞ ☚ |

| Variations | (See below) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | j(x), ij |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

J, or j, is the tenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its usual name in English is jay (pronounced ), with a now-uncommon variant jy .[1][2] When used in the International Phonetic Alphabet for the y sound, it may be called yod or jod (pronounced or ).[3]

History[edit]

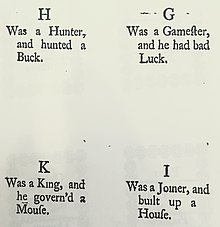

Children’s book from 1743, showing I and J considered as the same letter

The letter J used to be used as the swash letter I, used for the letter I at the end of Roman numerals when following another I, as in XXIIJ or xxiij instead of XXIII or xxiii for the Roman numeral twenty-three. A distinctive usage emerged in Middle High German.[4] Gian Giorgio Trissino (1478–1550) was the first to explicitly distinguish I and J as representing separate sounds, in his Ɛpistola del Trissino de le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua italiana («Trissino’s epistle about the letters recently added in the Italian language») of 1524.[5] Originally, ‘I’ and ‘J’ were different shapes for the same letter, both equally representing /i/, /iː/, and /j/; however, Romance languages developed new sounds (from former /j/ and /ɡ/) that came to be represented as ‘I’ and ‘J’; therefore, English J, acquired from the French J, has a sound value quite different from /j/ (which represents the initial sound in the English language word «yet»).

Pronunciation and use[edit]

| Most common pronunciation: /j/ Languages in italics do not use the Latin alphabet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation

(IPA) |

Environment | Notes |

| Afrikaans | /j/ | |||

| Albanian | /j/ | |||

| Arabic | Standard; most dialects | /dʒ/ | Latinization | |

| Gulf | /j/ | Latinization | ||

| Sudanese, Omani, Yemeni | /ɟ/ | Latinization | ||

| Levantine, Maghrebi | /ʒ/ | Latinization | ||

| Azeri | /ʒ/ | |||

| Basque[6] | Bizkaian | /dʒ/ | ||

| Lapurdian | /j/ | also used in southwest Bizkaian | ||

| Low Navarrese | /ɟ/ | also used in south Lapurdian | ||

| High Navarrese | /ʃ/ | |||

| Gipuzkoan | /x/ | also used in east Bizkaian | ||

| Zuberoan | /ʒ/ | |||

| Catalan | /ʒ/ or /dʒ/ | |||

| Czech | /j/ | |||

| Danish | /j/ | |||

| Dutch | /j/ | |||

| English | /dʒ/ | |||

| Esperanto | /j/ | |||

| Estonian | /j/ | |||

| Filipino | /dʒ/ | English loan words | ||

| /h/ | Spanish loan words | |||

| Finnish | /j/ | |||

| French | /ʒ/ | |||

| German | /j/ | |||

| Greenlandic | /j/ | |||

| Hindi | /dʒ/ | |||

| Hokkien | /dz/~/dʑ/ | |||

| /z/~/ʑ/ | ||||

| Hungarian | /j/ | |||

| Icelandic | /j/ | |||

| Igbo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Indonesian | /dʒ/ | |||

| Italian | /j/ | |||

| Japanese | /dʑ/~/ʑ/ | /ʑ/ and /dʑ/ distinct in some dialects, see Yotsugana | ||

| Khmer | /c/ | ALA-LC latinization | ||

| Kiowa | /t/ | |||

| Konkani | /ɟ/ | |||

| Korean | North | /ts/ | ||

| /dz/ | after vowels | |||

| South | /tɕ/ | |||

| /dʑ/ | after vowels | |||

| Kurdish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Luxembourgish | /j/ | |||

| /ʒ/ | Some loan words | |||

| Latvian | /j/ | |||

| Lithuanian | /j/ | |||

| Malay | /dʒ/ | |||

| Maltese | /j/ | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /tɕ/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| /ʐ/ | Wade–Giles latinization | |||

| Manx | /dʒ/ | |||

| Norwegian | /j/ | |||

| Oromo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Pashto | /dz/ | |||

| Polish | /j/ | |||

| Portuguese | /ʒ/ | |||

| Romanian | /ʒ/ | |||

| Scots | /dʒ/ | |||

| Serbo-Croatian | /j/ | |||

| Shona | /dʒ/ | |||

| Slovak | /j/ | |||

| Slovenian | /j/ | |||

| Somali | /dʒ/ | |||

| Spanish | Standard | /x/ | ||

| Some dialects | /h/ | |||

| Swahili | /ɟ/ | |||

| Swedish | /j/ | |||

| Tamil | /dʑ/ | |||

| Tatar | /ʐ/ | |||

| Telugu | /dʒ/ | |||

| Turkish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Turkmen | /dʒ/ | |||

| Yoruba | /ɟ/ | |||

| Zulu | /dʒ/ |

English[edit]

In English, ⟨j⟩ most commonly represents the affricate /dʒ/. In Old English, /dʒ/ was represented orthographically with ⟨cg⟩ and ⟨cȝ⟩.[7] Middle English scribes began to use ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) to represent word-initial /dʒ/ under the influence of Old French, which had a similar phoneme deriving from Latin /j/ (for example, iest and, later jest); the same sound in other positions could be spelled as ⟨dg⟩ (for example, hedge).[7] The first English language book to make a clear distinction in writing between ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩ was the King James Bible 1st Revision Cambridge 1629 and an English grammar book published in 1633.[8]

Later, many other uses of ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) were added in loanwords from French and other languages (e.g. adjoin, junta). In loanwords such as bijou or Dijon, ⟨j⟩ may represent /ʒ/, as in modern French. In some loanwords, including raj, Azerbaijan, Taj Mahal, and Beijing, the regular pronunciation /dʒ/ is actually closer to the native pronunciation, making the use of /ʒ/ an instance of hyperforeignism, a type of hypercorrection.[9] Occasionally, ⟨j⟩ represents the original /j/ sound, as in Hallelujah and fjord (see Yodh for details). In words of Spanish origin, such as jalapeño, English speakers usually pronounce ⟨j⟩ as the voiceless glottal fricative , an approximation of the Spanish pronunciation of ⟨j⟩ as the voiceless velar fricative [x] (some varieties of Spanish also use glottal [h]).

In English, ⟨j⟩ is the fourth least frequently used letter in words, being more frequent only than ⟨z⟩, ⟨q⟩, and ⟨x⟩. It is, however, quite common in proper nouns, especially personal names.

Other languages[edit]

Germanic and Eastern-European languages[edit]

The great majority of Germanic languages, such as German, Dutch, Icelandic, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian, use ⟨j⟩ for the palatal approximant /j/, which is usually represented by the letter ⟨y⟩ in English. Notable exceptions are English, Scots and (to a lesser degree) Luxembourgish. ⟨j⟩ also represents /j/ in Albanian, and those Uralic, Slavic and Baltic languages that use the Latin alphabet, such as Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian, Polish, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak, Slovenian, Latvian and Lithuanian. Some related languages, such as Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian, also adopted ⟨j⟩ into the Cyrillic alphabet for the same purpose. Because of this standard, the lower case letter was chosen to be used in the IPA as the phonetic symbol for the sound.

Romance languages[edit]

In the Romance languages, ⟨j⟩ has generally developed from its original palatal approximant value in Latin to some kind of fricative. In French, Portuguese, Catalan (except Valencian), and Romanian it has been fronted to the postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ (like ⟨s⟩ in English measure). In Valencian and Occitan it has the same sound as in English, /dʒ/. In Spanish, by contrast, it has been both devoiced and backed from an earlier /ʝ/ to a present-day /x/ or /h/,[10] with the actual phonetic realization depending on the speaker’s dialect.

Generally, ⟨j⟩ is not commonly present in modern standard Italian spelling. Only proper nouns (such as Jesi and Letojanni), Latin words (Juventus), or those borrowed from foreign languages have ⟨j⟩. The proper nouns and Latin words are pronounced as the palatal approximant /j/, while words borrowed from foreign languages tend to follow that language’s pronunciation of ⟨j⟩. Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used instead of ⟨i⟩ in diphthongs, as a replacement for final -ii, and in vowel groups (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing. ⟨j⟩ is also used to render /j/ in dialectal spelling, e.g. Romanesco dialect ⟨ajo⟩ [ajo] (garlic; cf. Italian aglio [aʎo]). The Italian novelist Luigi Pirandello used ⟨j⟩ in vowel groups in his works written in Italian; he also wrote in his native Sicilian language, which still uses the letter ⟨j⟩ to represent /j/ (and sometimes also [dʒ] or [gj], depending on its environment).[11]

Other European Languages[edit]

The Maltese language is a Semitic language, not a Romance language; but has been deeply influenced by them (especially Sicilian) and it uses ⟨j⟩ for the sound /j/ (cognate of the Semitic yod).

In Basque, the diaphoneme represented by ⟨j⟩ has a variety of realizations according to the regional dialect: [j, ʝ, ɟ, ʒ, ʃ, x] (the last one is typical of Gipuzkoa).

Non-European languages[edit]

Among non-European languages that have adopted the Latin script, ⟨j⟩ stands for /ʒ/ in Turkish and Azerbaijani, for /ʐ/ in Tatar. ⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in Indonesian, Somali, Malay, Igbo, Shona, Oromo, Turkmen, and Zulu. It represents a voiced palatal plosive /ɟ/ in Konkani, Yoruba, and Swahili. In Kiowa, ⟨j⟩ stands for a voiceless alveolar plosive, /t/.

⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in the romanization systems of most of the Languages of India such as Hindi and Telugu and stands for /dʑ/ in the Romanization of Japanese and Korean.

For Chinese languages, ⟨j⟩ stands for /t͡ɕ/ in Mandarin Chinese Pinyin system, the unaspirated equivalent of ⟨q⟩ (/t͡ɕʰ/). In Wade–Giles, ⟨j⟩ stands for Mandarin Chinese /ʐ/. Pe̍h-ōe-jī of Hokkien and Tâi-lô for Taiwanese Hokkien, ⟨j⟩ stands for /z/ and /ʑ/, or /d͡z/ and /d͡ʑ/, depending on accents. In Jyutping for Cantonese, ⟨j⟩ stands for /j/.

The Royal Thai General System of Transcription does not use the letter ⟨j⟩, although it is used in some proper names and non-standard transcriptions to represent either จ [tɕ] or ช [tɕʰ] (the latter following Pali/Sanskrit root equivalents).

In romanized Pashto, ⟨j⟩ represents ځ, pronounced [dz].

In Greenlandic and in the Qaniujaaqpait spelling of the Inuktitut language, ⟨j⟩ is used to transcribe /j/.

Following Spanish usage, ⟨j⟩ represents [x] or similar sounds in many Latin-alphabet-based writing systems for indigenous languages of the Americas, such as [χ] in Mayan languages (ALMG alphabet) and a glottal fricative [h] in some spelling systems used for Aymara.

[edit]

- 𐤉 : Semitic letter Yodh, from which the following symbols originally derive

- I i : Latin letter I, from which J derives

- ȷ : Dotless j

- ᶡ : Modifier letter small dotless j with stroke[12]

- ᶨ : Modifier letter small j with crossed-tail[12]

- IPA-specific symbols related to J: ʝ ɟ ʲ ʄ 𐞘[13]

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet-specific symbols related to J:

- U+1D0A ᴊ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL J[14]

- U+1D36 ᴶ MODIFIER LETTER CAPITAL J[14]

- U+2C7C ⱼ LATIN SUBSCRIPT SMALL LETTER J[15]

- J with diacritics: Ĵ ĵ J̌ ǰ Ɉ ɉ J̃ j̇̃

Computing codes[edit]

| Preview | J | j | ȷ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS J | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 74 | U+004A | 106 | U+006A | 567 | U+0237 |

| UTF-8 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A | 200 183 | C8 B7 |

| Numeric character reference | J | J | j | j | ȷ | ȷ |

| Named character reference | ȷ | |||||

| EBCDIC family | 209 | D1 | 145 | 91 | ||

| ASCII 1 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Unicode also has a dotless variant, ȷ (U+0237). It is primarily used in Landsmålsalfabet and in mathematics. It is not intended to be used with diacritics since the normal j is softdotted in Unicode (that is, the dot is removed if a diacritic is to be placed above; Unicode further states that, for example i+ ¨ ≠ ı+¨ and the same holds true for j and ȷ).[16]

In Unicode, a duplicate of ‘J’ for use as a special phonetic character in historical Greek linguistics is encoded in the Greek script block as ϳ (Unicode U+03F3). It is used to denote the palatal glide /j/ in the context of Greek script. It is called «Yot» in the Unicode standard, after the German name of the letter J.[17][18] An uppercase version of this letter was added to the Unicode Standard at U+037F with the release of version 7.0 in June 2014.[19][20]

Wingdings smiley issue[edit]

In the Wingdings font by Microsoft, the letter «J» is rendered as a smiley face (this is distinct from the Unicode code point U+263A, which renders as ☺︎). In Microsoft applications, «:)» is automatically replaced by a smiley rendered in a specific font face when composing rich text documents or HTML email. This autocorrection feature can be switched off or changed to a Unicode smiley.[21]

[22]

Other uses[edit]

- In international licence plate codes, J stands for Japan.

- In mathematics, j is one of the three imaginary units of quaternions.

- Also in mathematics, j is one of the three unit vectors.

- In the Metric system, J is the symbol for the joule, the SI derived unit for energy.

- In some areas of physics, electrical engineering and related fields, j is the symbol for the imaginary unit (the square root of −1) (in other fields the letter i is used, but this would be ambiguous as it is also the symbol for current).

- A J can be a slang term for a joint (marijuana cigarette)

- In the United Kingdom under the old system (before 2001), a licence plate that begins with «J» for example «J123 XYZ» would correspond to a vehicle registered between August 1, 1991 and July 31, 1992. Again under the old system, a licence plate that ends with «J» for example «ABC 123J» would correspond to a vehicle that was registered between August 1, 1970 and July 31, 1971.[23]

Other representations[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ «J», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989)

- ^ «J» and «jay», Merriam-Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993)

- ^ «yod». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Wörterbuchnetz». Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ De le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua Italiana in Italian Wikisource.

- ^ Trask, R. L. (Robert Lawrence), 1944-2004. (1997). The history of Basque. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2. OCLC 34514667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hogg, Richard M.; Norman Francis Blake; Roger Lass; Suzanne Romaine; R. W. Burchfield; John Algeo (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-521-26476-6.

- ^ English Grammar, Charles Butler, 1633

- ^ Wells, John (1982). Accents of English 1: An Introduction. Cambridge, UN: Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-521-29719-2.

- ^ Penny, Ralph John (2002). A History of the Spanish Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01184-1.

- ^ Cipolla, Gaetano (2007). The Sounds of Sicilian: A Pronunciation Guide. Mineola, NY: Legas. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9781881901518. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ a b Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). «L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS» (PDF).

- ^ Miller, Kirk; Ashby, Michael (2020-11-08). «L2/20-252R: Unicode request for IPA modifier-letters (a), pulmonic» (PDF).

- ^ a b Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). «L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS» (PDF).

- ^ Ruppel, Klaas; Rueter, Jack; Kolehmainen, Erkki I. (2006-04-07). «L2/06-215: Proposal for Encoding 3 Additional Characters of the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet» (PDF).

- ^ The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0, p. 293 (at the very bottom)

- ^ Nick Nicholas, «Yot» Archived 2012-08-05 at archive.today

- ^ «Unicode Character ‘GREEK LETTER YOT’ (U+03F3)». Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ «Unicode: Greek and Coptic» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ^ «Unicode 7.0.0». Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ^ Pirillo, Chris (26 June 2010). «J Smiley Outlook Email: Problem and Fix!». Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (23 May 2006). «That mysterious J». The Old New Thing. MSDN Blogs. Retrieved 2011-04-01.

- ^ «Car Registration Years | Suffix Number Plates | Platehunter». www.platehunter.com. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to J.

This article is about the tenth letter of the Latin alphabet. For other uses, see J (disambiguation).

| J | |

|---|---|

| J j ȷ | |

| (See below) | |

|

|

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage | [j] [dʒ]~[tʃ] [x~h] [ʒ] [ɟ] [ʝ] [dz] [tɕ] [gʱ] [t]~[dʑ] [ʐ] [ʃ] [c̬] [i] |

| Unicode codepoint | U+004A, U+006A, U+0237 |

| Alphabetical position | 10 |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Time period | 1524 to present |

| Descendants | • Ɉ • Tittle • J |

| Sisters | І Ј י ي ܝ ی ࠉ 𐎊 ዪ Ⴢ ⴢ ჲ ☞ ☚ |

| Variations | (See below) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | j(x), ij |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

J, or j, is the tenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its usual name in English is jay (pronounced ), with a now-uncommon variant jy .[1][2] When used in the International Phonetic Alphabet for the y sound, it may be called yod or jod (pronounced or ).[3]

History[edit]

Children’s book from 1743, showing I and J considered as the same letter

The letter J used to be used as the swash letter I, used for the letter I at the end of Roman numerals when following another I, as in XXIIJ or xxiij instead of XXIII or xxiii for the Roman numeral twenty-three. A distinctive usage emerged in Middle High German.[4] Gian Giorgio Trissino (1478–1550) was the first to explicitly distinguish I and J as representing separate sounds, in his Ɛpistola del Trissino de le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua italiana («Trissino’s epistle about the letters recently added in the Italian language») of 1524.[5] Originally, ‘I’ and ‘J’ were different shapes for the same letter, both equally representing /i/, /iː/, and /j/; however, Romance languages developed new sounds (from former /j/ and /ɡ/) that came to be represented as ‘I’ and ‘J’; therefore, English J, acquired from the French J, has a sound value quite different from /j/ (which represents the initial sound in the English language word «yet»).

Pronunciation and use[edit]

| Most common pronunciation: /j/ Languages in italics do not use the Latin alphabet | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation

(IPA) |

Environment | Notes |

| Afrikaans | /j/ | |||

| Albanian | /j/ | |||

| Arabic | Standard; most dialects | /dʒ/ | Latinization | |

| Gulf | /j/ | Latinization | ||

| Sudanese, Omani, Yemeni | /ɟ/ | Latinization | ||

| Levantine, Maghrebi | /ʒ/ | Latinization | ||

| Azeri | /ʒ/ | |||

| Basque[6] | Bizkaian | /dʒ/ | ||

| Lapurdian | /j/ | also used in southwest Bizkaian | ||

| Low Navarrese | /ɟ/ | also used in south Lapurdian | ||

| High Navarrese | /ʃ/ | |||

| Gipuzkoan | /x/ | also used in east Bizkaian | ||

| Zuberoan | /ʒ/ | |||

| Catalan | /ʒ/ or /dʒ/ | |||

| Czech | /j/ | |||

| Danish | /j/ | |||

| Dutch | /j/ | |||

| English | /dʒ/ | |||

| Esperanto | /j/ | |||

| Estonian | /j/ | |||

| Filipino | /dʒ/ | English loan words | ||

| /h/ | Spanish loan words | |||

| Finnish | /j/ | |||

| French | /ʒ/ | |||

| German | /j/ | |||

| Greenlandic | /j/ | |||

| Hindi | /dʒ/ | |||

| Hokkien | /dz/~/dʑ/ | |||

| /z/~/ʑ/ | ||||

| Hungarian | /j/ | |||

| Icelandic | /j/ | |||

| Igbo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Indonesian | /dʒ/ | |||

| Italian | /j/ | |||

| Japanese | /dʑ/~/ʑ/ | /ʑ/ and /dʑ/ distinct in some dialects, see Yotsugana | ||

| Khmer | /c/ | ALA-LC latinization | ||

| Kiowa | /t/ | |||

| Konkani | /ɟ/ | |||

| Korean | North | /ts/ | ||

| /dz/ | after vowels | |||

| South | /tɕ/ | |||

| /dʑ/ | after vowels | |||

| Kurdish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Luxembourgish | /j/ | |||

| /ʒ/ | Some loan words | |||

| Latvian | /j/ | |||

| Lithuanian | /j/ | |||

| Malay | /dʒ/ | |||

| Maltese | /j/ | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /tɕ/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| /ʐ/ | Wade–Giles latinization | |||

| Manx | /dʒ/ | |||

| Norwegian | /j/ | |||

| Oromo | /dʒ/ | |||

| Pashto | /dz/ | |||

| Polish | /j/ | |||

| Portuguese | /ʒ/ | |||

| Romanian | /ʒ/ | |||

| Scots | /dʒ/ | |||

| Serbo-Croatian | /j/ | |||

| Shona | /dʒ/ | |||

| Slovak | /j/ | |||

| Slovenian | /j/ | |||

| Somali | /dʒ/ | |||

| Spanish | Standard | /x/ | ||

| Some dialects | /h/ | |||

| Swahili | /ɟ/ | |||

| Swedish | /j/ | |||

| Tamil | /dʑ/ | |||

| Tatar | /ʐ/ | |||

| Telugu | /dʒ/ | |||

| Turkish | /ʒ/ | |||

| Turkmen | /dʒ/ | |||

| Yoruba | /ɟ/ | |||

| Zulu | /dʒ/ |

English[edit]

In English, ⟨j⟩ most commonly represents the affricate /dʒ/. In Old English, /dʒ/ was represented orthographically with ⟨cg⟩ and ⟨cȝ⟩.[7] Middle English scribes began to use ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) to represent word-initial /dʒ/ under the influence of Old French, which had a similar phoneme deriving from Latin /j/ (for example, iest and, later jest); the same sound in other positions could be spelled as ⟨dg⟩ (for example, hedge).[7] The first English language book to make a clear distinction in writing between ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩ was the King James Bible 1st Revision Cambridge 1629 and an English grammar book published in 1633.[8]

Later, many other uses of ⟨i⟩ (later ⟨j⟩) were added in loanwords from French and other languages (e.g. adjoin, junta). In loanwords such as bijou or Dijon, ⟨j⟩ may represent /ʒ/, as in modern French. In some loanwords, including raj, Azerbaijan, Taj Mahal, and Beijing, the regular pronunciation /dʒ/ is actually closer to the native pronunciation, making the use of /ʒ/ an instance of hyperforeignism, a type of hypercorrection.[9] Occasionally, ⟨j⟩ represents the original /j/ sound, as in Hallelujah and fjord (see Yodh for details). In words of Spanish origin, such as jalapeño, English speakers usually pronounce ⟨j⟩ as the voiceless glottal fricative , an approximation of the Spanish pronunciation of ⟨j⟩ as the voiceless velar fricative [x] (some varieties of Spanish also use glottal [h]).

In English, ⟨j⟩ is the fourth least frequently used letter in words, being more frequent only than ⟨z⟩, ⟨q⟩, and ⟨x⟩. It is, however, quite common in proper nouns, especially personal names.

Other languages[edit]

Germanic and Eastern-European languages[edit]

The great majority of Germanic languages, such as German, Dutch, Icelandic, Swedish, Danish and Norwegian, use ⟨j⟩ for the palatal approximant /j/, which is usually represented by the letter ⟨y⟩ in English. Notable exceptions are English, Scots and (to a lesser degree) Luxembourgish. ⟨j⟩ also represents /j/ in Albanian, and those Uralic, Slavic and Baltic languages that use the Latin alphabet, such as Hungarian, Finnish, Estonian, Polish, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Slovak, Slovenian, Latvian and Lithuanian. Some related languages, such as Serbo-Croatian and Macedonian, also adopted ⟨j⟩ into the Cyrillic alphabet for the same purpose. Because of this standard, the lower case letter was chosen to be used in the IPA as the phonetic symbol for the sound.

Romance languages[edit]

In the Romance languages, ⟨j⟩ has generally developed from its original palatal approximant value in Latin to some kind of fricative. In French, Portuguese, Catalan (except Valencian), and Romanian it has been fronted to the postalveolar fricative /ʒ/ (like ⟨s⟩ in English measure). In Valencian and Occitan it has the same sound as in English, /dʒ/. In Spanish, by contrast, it has been both devoiced and backed from an earlier /ʝ/ to a present-day /x/ or /h/,[10] with the actual phonetic realization depending on the speaker’s dialect.

Generally, ⟨j⟩ is not commonly present in modern standard Italian spelling. Only proper nouns (such as Jesi and Letojanni), Latin words (Juventus), or those borrowed from foreign languages have ⟨j⟩. The proper nouns and Latin words are pronounced as the palatal approximant /j/, while words borrowed from foreign languages tend to follow that language’s pronunciation of ⟨j⟩. Until the 19th century, ⟨j⟩ was used instead of ⟨i⟩ in diphthongs, as a replacement for final -ii, and in vowel groups (as in Savoja); this rule was quite strict in official writing. ⟨j⟩ is also used to render /j/ in dialectal spelling, e.g. Romanesco dialect ⟨ajo⟩ [ajo] (garlic; cf. Italian aglio [aʎo]). The Italian novelist Luigi Pirandello used ⟨j⟩ in vowel groups in his works written in Italian; he also wrote in his native Sicilian language, which still uses the letter ⟨j⟩ to represent /j/ (and sometimes also [dʒ] or [gj], depending on its environment).[11]

Other European Languages[edit]

The Maltese language is a Semitic language, not a Romance language; but has been deeply influenced by them (especially Sicilian) and it uses ⟨j⟩ for the sound /j/ (cognate of the Semitic yod).

In Basque, the diaphoneme represented by ⟨j⟩ has a variety of realizations according to the regional dialect: [j, ʝ, ɟ, ʒ, ʃ, x] (the last one is typical of Gipuzkoa).

Non-European languages[edit]

Among non-European languages that have adopted the Latin script, ⟨j⟩ stands for /ʒ/ in Turkish and Azerbaijani, for /ʐ/ in Tatar. ⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in Indonesian, Somali, Malay, Igbo, Shona, Oromo, Turkmen, and Zulu. It represents a voiced palatal plosive /ɟ/ in Konkani, Yoruba, and Swahili. In Kiowa, ⟨j⟩ stands for a voiceless alveolar plosive, /t/.

⟨j⟩ stands for /dʒ/ in the romanization systems of most of the Languages of India such as Hindi and Telugu and stands for /dʑ/ in the Romanization of Japanese and Korean.

For Chinese languages, ⟨j⟩ stands for /t͡ɕ/ in Mandarin Chinese Pinyin system, the unaspirated equivalent of ⟨q⟩ (/t͡ɕʰ/). In Wade–Giles, ⟨j⟩ stands for Mandarin Chinese /ʐ/. Pe̍h-ōe-jī of Hokkien and Tâi-lô for Taiwanese Hokkien, ⟨j⟩ stands for /z/ and /ʑ/, or /d͡z/ and /d͡ʑ/, depending on accents. In Jyutping for Cantonese, ⟨j⟩ stands for /j/.

The Royal Thai General System of Transcription does not use the letter ⟨j⟩, although it is used in some proper names and non-standard transcriptions to represent either จ [tɕ] or ช [tɕʰ] (the latter following Pali/Sanskrit root equivalents).

In romanized Pashto, ⟨j⟩ represents ځ, pronounced [dz].

In Greenlandic and in the Qaniujaaqpait spelling of the Inuktitut language, ⟨j⟩ is used to transcribe /j/.

Following Spanish usage, ⟨j⟩ represents [x] or similar sounds in many Latin-alphabet-based writing systems for indigenous languages of the Americas, such as [χ] in Mayan languages (ALMG alphabet) and a glottal fricative [h] in some spelling systems used for Aymara.

[edit]

- 𐤉 : Semitic letter Yodh, from which the following symbols originally derive

- I i : Latin letter I, from which J derives

- ȷ : Dotless j

- ᶡ : Modifier letter small dotless j with stroke[12]

- ᶨ : Modifier letter small j with crossed-tail[12]

- IPA-specific symbols related to J: ʝ ɟ ʲ ʄ 𐞘[13]

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet-specific symbols related to J:

- U+1D0A ᴊ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL J[14]

- U+1D36 ᴶ MODIFIER LETTER CAPITAL J[14]

- U+2C7C ⱼ LATIN SUBSCRIPT SMALL LETTER J[15]

- J with diacritics: Ĵ ĵ J̌ ǰ Ɉ ɉ J̃ j̇̃

Computing codes[edit]

| Preview | J | j | ȷ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER J | LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS J | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 74 | U+004A | 106 | U+006A | 567 | U+0237 |

| UTF-8 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A | 200 183 | C8 B7 |

| Numeric character reference | J | J | j | j | ȷ | ȷ |

| Named character reference | ȷ | |||||

| EBCDIC family | 209 | D1 | 145 | 91 | ||

| ASCII 1 | 74 | 4A | 106 | 6A |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Unicode also has a dotless variant, ȷ (U+0237). It is primarily used in Landsmålsalfabet and in mathematics. It is not intended to be used with diacritics since the normal j is softdotted in Unicode (that is, the dot is removed if a diacritic is to be placed above; Unicode further states that, for example i+ ¨ ≠ ı+¨ and the same holds true for j and ȷ).[16]

In Unicode, a duplicate of ‘J’ for use as a special phonetic character in historical Greek linguistics is encoded in the Greek script block as ϳ (Unicode U+03F3). It is used to denote the palatal glide /j/ in the context of Greek script. It is called «Yot» in the Unicode standard, after the German name of the letter J.[17][18] An uppercase version of this letter was added to the Unicode Standard at U+037F with the release of version 7.0 in June 2014.[19][20]

Wingdings smiley issue[edit]

In the Wingdings font by Microsoft, the letter «J» is rendered as a smiley face (this is distinct from the Unicode code point U+263A, which renders as ☺︎). In Microsoft applications, «:)» is automatically replaced by a smiley rendered in a specific font face when composing rich text documents or HTML email. This autocorrection feature can be switched off or changed to a Unicode smiley.[21]

[22]

Other uses[edit]

- In international licence plate codes, J stands for Japan.

- In mathematics, j is one of the three imaginary units of quaternions.

- Also in mathematics, j is one of the three unit vectors.

- In the Metric system, J is the symbol for the joule, the SI derived unit for energy.

- In some areas of physics, electrical engineering and related fields, j is the symbol for the imaginary unit (the square root of −1) (in other fields the letter i is used, but this would be ambiguous as it is also the symbol for current).

- A J can be a slang term for a joint (marijuana cigarette)

- In the United Kingdom under the old system (before 2001), a licence plate that begins with «J» for example «J123 XYZ» would correspond to a vehicle registered between August 1, 1991 and July 31, 1992. Again under the old system, a licence plate that ends with «J» for example «ABC 123J» would correspond to a vehicle that was registered between August 1, 1970 and July 31, 1971.[23]

Other representations[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ «J», Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989)

- ^ «J» and «jay», Merriam-Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993)

- ^ «yod». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ «Wörterbuchnetz». Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ De le lettere nuωvamente aggiunte ne la lingua Italiana in Italian Wikisource.

- ^ Trask, R. L. (Robert Lawrence), 1944-2004. (1997). The history of Basque. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2. OCLC 34514667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hogg, Richard M.; Norman Francis Blake; Roger Lass; Suzanne Romaine; R. W. Burchfield; John Algeo (1992). The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-521-26476-6.

- ^ English Grammar, Charles Butler, 1633

- ^ Wells, John (1982). Accents of English 1: An Introduction. Cambridge, UN: Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-521-29719-2.

- ^ Penny, Ralph John (2002). A History of the Spanish Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01184-1.

- ^ Cipolla, Gaetano (2007). The Sounds of Sicilian: A Pronunciation Guide. Mineola, NY: Legas. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9781881901518. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ a b Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). «L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS» (PDF).

- ^ Miller, Kirk; Ashby, Michael (2020-11-08). «L2/20-252R: Unicode request for IPA modifier-letters (a), pulmonic» (PDF).

- ^ a b Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). «L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS» (PDF).

- ^ Ruppel, Klaas; Rueter, Jack; Kolehmainen, Erkki I. (2006-04-07). «L2/06-215: Proposal for Encoding 3 Additional Characters of the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet» (PDF).

- ^ The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0, p. 293 (at the very bottom)

- ^ Nick Nicholas, «Yot» Archived 2012-08-05 at archive.today

- ^ «Unicode Character ‘GREEK LETTER YOT’ (U+03F3)». Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ «Unicode: Greek and Coptic» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ^ «Unicode 7.0.0». Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- ^ Pirillo, Chris (26 June 2010). «J Smiley Outlook Email: Problem and Fix!». Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (23 May 2006). «That mysterious J». The Old New Thing. MSDN Blogs. Retrieved 2011-04-01.

- ^ «Car Registration Years | Suffix Number Plates | Platehunter». www.platehunter.com. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to J.

Английская буква джи — написание и произношение

G – седьмая буква английского алфавита. Она имеет несколько вариантов написания, техника зависит от шрифта (печатный/рукописный) и типа символа (заглавная/строчная).

Техника написания

Для написания буквы «G» предпочтительно взять лист разлинованной бумаги, чтобы видеть разницу между прописными и строчными буквами.

Печатная заглавная «G»

- Написать заглавную букву «С»:

- начертить полумесяц с отверстием справа

- От нижней точки буквы «С» добавить горизонтальную линию влево, внутрь буквы наполовину

Печатная строчная «g»

- Написать строчную букву «с».

- Единственное отличие от заглавной буквы «С»: строчная меньше почти в два раза.

- От верхней точки буквы «с» провести вертикальную линию вниз, переходящую в крючок в левую сторону.

Печатная строчная «g»

- В верхней части строки изобразить букву «о» размером 7/8 от строчной буквы.

- От нижней правой точки нарисовать овальную петлю вправо и вниз.

- К верхней правой точке добавить «ушко».

Рукописная заглавная

- От левой нижней точки строки начертить наклонную линию, ведущую вправо вверх.

- Развернуть петлей влево и вниз. Вывести петлю крючком вправо до самого верха строки.

- Начертить наклонную линию, идущую влево вниз. Вывести ее крючком влево. Крючок должен пересечь первую линию (шаг 1).

- Провести горизонтальную линию вправо, внутрь наполовину буквы.

Рукописная строчная «g»

- Нарисовать о образную форму с наклоном.

- От нижней правой точки добавить наклонную линию, ведущую влево вниз.

- Развернуть ее влево петлей и вывести наверх.

Произношение буквы «G»

Буква «G» имеет два основных правила чтения и несколько второстепенных.

g = [г]

- перед гласными a, o, u.

legacy [‘legəsi] – наследство, наследие

go [gou] – идти

regulate [‘regjuleit] – регулировать

- перед любой согласной.

ingredient [in’gri:diənt] – компонент

- в конце слова.

leg [leg] – нога

g = [дж]

- перед гласными e, i, y.

page [peidʒ] – страница

giant [‘dʒaiənt] – гигант

gym [dʒim] – тренажерный зал

Исключения:

- g = [г] перед окончаниями -er и -est прилагательных и наречий.

big [big] – большой / bigger [‘bigə] – больше / biggest [‘bigəst] – самый большой

g = [г] в следующих словах:

begin – начинать(ся) anger – гнев

gift – подарок

forget – забывать

get – получать

target – цель, мишень

girl – девушка

together – вместе

give – давать

forgive – прощать

geese – гуси

finger – палец

tiger – тигр

hunger – голод

- g = [ж] в словах французского происхождения.

garage [gə’raʒ] – гараж

- gn = [-] в начале и конце слов.

gnome [noum] – гном

sign [sain] – символ; подпись

ng = [ŋ]

Язык располагается у основания нижних зубов. Рот открыт широко. Задняя часть языка прижата к опущенному мягкому нёбу, воздушная струя следует через полость носа. Для носового звука требуется не поднимать к альвеолам кончик языка.

kingdom [‘kiŋdəm] – королевство

gh = [г], [ф], [-]

Чтение слов с буквосочетанием «gh» необходимо проверять по словарю в связи с вариациями произношения и отсутствием правил.

ghost [gəust] – приведение

tough [tʌf] – жесткий

high [hai] – высоко

This article is about the letter of the alphabet. For other uses, see G (disambiguation).

| G | |

|---|---|

| G g | |

| (See below, Typographic) | |

|

|

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage |

|

| Unicode codepoint | U+0047, U+0067, U+0261 |

| Alphabetical position | 7 |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Time period | ~-300 to present |

| Descendants |

|

| Sisters |

|

| Transliteration equivalents | C |

| Variations | (See below, Typographic) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | gh, g(x) |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

G, or g, is the seventh letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is gee (pronounced ), plural gees.[1]

History

The letter ‘G’ was introduced in the Old Latin period as a variant of ‘C’ to distinguish voiced /ɡ/ from voiceless /k/.

The recorded originator of ‘G’ is freedman Spurius Carvilius Ruga, who added letter G to the teaching of the Roman alphabet during the 3rd century BC:[2] he was the first Roman to open a fee-paying school, around 230 BCE. At this time, ‘K’ had fallen out of favor, and ‘C’, which had formerly represented both /ɡ/ and /k/ before open vowels, had come to express /k/ in all environments.

Ruga’s positioning of ‘G’ shows that alphabetic order related to the letters’ values as Greek numerals was a concern even in the 3rd century BC. According to some records, the original seventh letter, ‘Z’, had been purged from the Latin alphabet somewhat earlier in the 3rd century BC by the Roman censor Appius Claudius, who found it distasteful and foreign.[3] Sampson (1985) suggests that: «Evidently the order of the alphabet was felt to be such a concrete thing that a new letter could be added in the middle only if a ‘space’ was created by the dropping of an old letter.»[4]

George Hempl proposed in 1899 that there never was such a «space» in the alphabet and that in fact ‘G’ was a direct descendant of zeta. Zeta took shapes like ⊏ in some of the Old Italic scripts; the development of the monumental form ‘G’ from this shape would be exactly parallel to the development of ‘C’ from gamma. He suggests that the pronunciation /k/ > /ɡ/ was due to contamination from the also similar-looking ‘K’.[5]

Eventually, both velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ developed palatalized allophones before front vowels; consequently in today’s Romance languages, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ have different sound values depending on context (known as hard and soft C and hard and soft G). Because of French influence, English language orthography shares this feature.

Typographic variants

The modern lowercase ‘g’ has two typographic variants: the single-storey (sometimes opentail) ‘‘ and the double-storey (sometimes looptail) ‘

‘. The single-storey form derives from the majuscule (uppercase) form by raising the serif that distinguishes it from ‘c’ to the top of the loop, thus closing the loop and extending the vertical stroke downward and to the left. The double-storey form (

) had developed similarly, except that some ornate forms then extended the tail back to the right, and to the left again, forming a closed bowl or loop. The initial extension to the left was absorbed into the upper closed bowl. The double-storey version became popular when printing switched to «Roman type» because the tail was effectively shorter, making it possible to put more lines on a page. In the double-storey version, a small top stroke in the upper-right, often terminating in an orb shape, is called an «ear».

Generally, the two forms are complementary, but occasionally the difference has been exploited to provide contrast. In the International Phonetic Alphabet, opentail ⟨ɡ⟩ has always represented a voiced velar plosive, while ⟨⟩ was distinguished from ⟨ɡ⟩ and represented a voiced velar fricative from 1895 to 1900.[6][7] In 1948, the Council of the International Phonetic Association recognized ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨

⟩ as typographic equivalents,[8] and this decision was reaffirmed in 1993.[9] While the 1949 Principles of the International Phonetic Association recommended the use of ⟨

⟩ for a velar plosive and ⟨ɡ⟩ for an advanced one for languages where it is preferable to distinguish the two, such as Russian,[10] this practice never caught on.[11] The 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, the successor to the Principles, abandoned the recommendation and acknowledged both shapes as acceptable variants.[12]

Wong et al. (2018) found that native English speakers have little conscious awareness of the looptail ‘g’ ().[13][14] They write: «Despite being questioned repeatedly, and despite being informed directly that G has two lowercase print forms, nearly half of the participants failed to reveal any knowledge of the looptail ‘g’, and only 1 of the 38 participants was able to write looptail ‘g’ correctly.»

In Unicode, the two appearances are generally treated as glyph variants with no semantic difference. For applications where the single-storey variant must be distinguished (such as strict IPA in a typeface where the usual g character is double-storey), the character U+0261 ɡ LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G is available, as well as an upper case version, U+A7AC Ɡ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SCRIPT G.

Pronunciation and use

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) | Environment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | /x/ | |||

| Arabic | /ɡ/ | Latinization; corresponding to ⟨ق⟩ or ⟨ج⟩ in Arabic | ||

| Azeri | /ɟ/ | |||

| Catalan | /(d)ʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Danish | /ɡ/ | Word-initially | ||

| /k/ | Usually | |||

| Dutch | Standard | /ɣ/ | ||

| Southern dialects | /ɣ̟/ | |||

| Northern dialects | /χ/ | |||

| English | /dʒ/ | Before e, i, y (see exceptions below) | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i in «modern» loanwords from French | |||

| silent | Some words, initial <gn>, and word-finally before a consonant | |||

| Faroese | /j/ | soft, lenited; see Faroese phonology | ||

| /k/ | hard | |||

| /tʃ/ | soft | |||

| /v/ | after a, æ, á, e, o, ø and before u | |||

| /w/ | after ó, u, ú and before a, i, or u | |||

| silent | after a, æ, á, e, o, ø and before a | |||

| Fijian | /ŋ/ | |||

| French | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i, y | |||

| Galician | /ɡ/~/ħ/ | Usually | See Gheada for consonant variation | |

| /ʃ/ | Before e, i | obsolete spelling, replaced by the letter x | ||

| Greek | /ɡ/ | Usually | Latinization | |

| /ɟ/ | Before ai, e, i, oi, y | Latinization | ||

| Icelandic | /c/ | soft | ||

| /k/ | hard | |||

| /ɣ/ | hard, lenited; see Icelandic phonology | |||

| /j/ | soft, lenited | |||

| Irish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ɟ/ | After i or before e, i | |||

| Italian | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /dʒ/ | Before e, i | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /k/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| Norman | /dʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Norwegian | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /j/ | Before ei, i, j, øy, y | |||

| Portuguese | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i, y | |||

| Romanian | /dʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Romansh | /dʑ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Samoan | /ŋ/ | |||

| Scottish Gaelic | /k/ | Usually | ||

| /kʲ/ | After i or before e, i | |||

| Spanish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /x/ or /h/ | Before e, i, y | Variation between velar and glottal realizations depends on dialect | ||

| Swedish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /j/ | Before ä, e, i, ö, y | |||

| Turkish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ɟ/ | Before e, i, ö, ü | |||

| Vietnamese | Standard | /ɣ/ | ||

| Northern | /z/ | Before i | ||

| Southern | /j/ | Before i |

English

In English, the letter appears either alone or in some digraphs. Alone, it represents

- a voiced velar plosive (/ɡ/ or «hard» ⟨g⟩), as in goose, gargoyle, and game;

- a voiced palato-alveolar affricate (/d͡ʒ/ or «soft» ⟨g⟩), predominates before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩, as in giant, ginger, and geology; or

- a voiced palato-alveolar sibilant (/ʒ/) in post-medieval loanwords from French, such as rouge, beige, genre (often), and margarine (rarely)

⟨g⟩ is predominantly soft before ⟨e⟩ (including the digraphs ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩), ⟨i⟩, or ⟨y⟩, and hard otherwise. It is hard in those derivations from γυνή (gynḗ) meaning woman where initial-worded as such. Soft ⟨g⟩ is also used in many words that came into English from medieval church/academic use, French, Spanish, Italian or Portuguese – these tend to, in other ways in English, closely align to their Ancient Latin and Greek roots (such as fragile, logic or magic).

There remain widely used a few English words of non-Romance origin where ⟨g⟩ is hard followed by ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ (get, give, gift), and very few in which ⟨g⟩ is soft though followed by ⟨a⟩ such as gaol, which since the 20th century is almost always written as «jail».

The double consonant ⟨gg⟩ has the value /ɡ/ (hard ⟨g⟩) as in nugget, with very few exceptions: /d͡ʒ/ in exaggerate and veggies and dialectally /ɡd͡ʒ/ in suggest.

The digraph ⟨dg⟩ has the value /d͡ʒ/ (soft ⟨g⟩), as in badger. Non-digraph ⟨dg⟩ can also occur, in compounds like floodgate and headgear.

The digraph ⟨ng⟩ may represent:

- a velar nasal () as in length, singer

- the latter followed by hard ⟨g⟩ (/ŋɡ/) as in jungle, finger, longest

Non-digraph ⟨ng⟩ also occurs, with possible values

- /nɡ/ as in engulf, ungainly

- /nd͡ʒ/ as in sponge, angel

- /nʒ/ as in melange

The digraph ⟨gh⟩ (in many cases a replacement for the obsolete letter yogh, which took various values including /ɡ/, /ɣ/, /x/ and /j/) may represent:

- /ɡ/ as in ghost, aghast, burgher, spaghetti

- /f/ as in cough, laugh, roughage

- Ø (no sound) as in through, neighbor, night

- /x/ in ugh

- (rarely) /p/ in hiccough

- (rarely) /k/ in s’ghetti

Non-digraph ⟨gh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like foghorn, pigheaded

The digraph ⟨gn⟩ may represent:

- /n/ as in gnostic, deign, foreigner, signage

- /nj/ in loanwords like champignon, lasagna

Non-digraph ⟨gn⟩ also occurs, as in signature, agnostic

The trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ has the value /ŋ/ as in gingham or dinghy. Non-trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like stronghold and dunghill.

G is the tenth least frequently used letter in the English language (after Y, P, B, V, K, J, X, Q, and Z), with a frequency of about 2.02% in words.

Other languages

Most Romance languages and some Nordic languages also have two main pronunciations for ⟨g⟩, hard and soft. While the soft value of ⟨g⟩ varies in different Romance languages (/ʒ/ in French and Portuguese, [(d)ʒ] in Catalan, /d͡ʒ/ in Italian and Romanian, and /x/ in most dialects of Spanish), in all except Romanian and Italian, soft ⟨g⟩ has the same pronunciation as the ⟨j⟩.

In Italian and Romanian, ⟨gh⟩ is used to represent /ɡ/ before front vowels where ⟨g⟩ would otherwise represent a soft value. In Italian and French, ⟨gn⟩ is used to represent the palatal nasal /ɲ/, a sound somewhat similar to the ⟨ny⟩ in English canyon. In Italian, the trigraph ⟨gli⟩, when appearing before a vowel or as the article and pronoun gli, represents the palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/.

Other languages typically use ⟨g⟩ to represent /ɡ/ regardless of position.

Amongst European languages, Czech, Dutch, Estonian and Finnish are an exception as they do not have /ɡ/ in their native words. In Dutch, ⟨g⟩ represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ instead, a sound that does not occur in modern English, but there is a dialectal variation: many Netherlandic dialects use a voiceless fricative ([x] or [χ]) instead, and in southern dialects it may be palatal [ʝ]. Nevertheless, word-finally it is always voiceless in all dialects, including the standard Dutch of Belgium and the Netherlands. On the other hand, some dialects (like Amelands) may have a phonemic /ɡ/.

Faroese uses ⟨g⟩ to represent /dʒ/, in addition to /ɡ/, and also uses it to indicate a glide.

In Māori, ⟨g⟩ is used in the digraph ⟨ng⟩ which represents the velar nasal /ŋ/ and is pronounced like the ⟨ng⟩ in singer.

The Samoan and Fijian languages use the letter ⟨g⟩ by itself for /ŋ/.

In older Czech and Slovak orthographies, ⟨g⟩ was used to represent /j/, while /ɡ/ was written as ⟨ǧ⟩ (⟨g⟩ with caron).

The Azerbaijani Latin alphabet uses ⟨g⟩ exclusively for the «soft» sound, namely /ɟ/. The sound /ɡ/ is written as ⟨q⟩. This leads to unusual spellings of loanwords: qram ‘gram’, qrup ‘group’, qaraj ‘garage’, qallium ‘gallium’.

Ancestors, descendants and siblings

- 𐤂 : Semitic letter Gimel, from which the following symbols originally derive

- C c : Latin letter C, from which G derives

- Γ γ : Greek letter Gamma, from which C derives in turn

- ɡ : Latin letter script small G

- ᶢ : Modifier letter small script g is used for phonetic transcription[15]

- 𝼁 : Latin small letter reversed script g, an extension to IPA for disordered speech (extIPA)[16][17]

- ᵷ : Turned g

- 𝼂 : Latin letter small capital turned g, an extension to IPA for disordered speech (extIPA)[16][17]

- Г г : Cyrillic letter Ge

- Ȝ ȝ : Latin letter Yogh

- Ɣ ɣ : Latin letter Gamma

- Ᵹ ᵹ : Insular g

- ᫌ : Combining insular g, used in the Ormulum[18]

- Ꝿ ꝿ : Turned insular g

- Ꟑ ꟑ : Closed insular g, used in the Ormulum[18]

- ɢ : Latin letter small capital G, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular stop

- 𐞒 : Modifier letter small capital G, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- ʛ : Latin letter small capital G with hook, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular implosive

- 𐞔 : Modifier letter small capital G with hook, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- 𐞓 : Modifier letter small g with hook, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- ᴳ ᵍ : Modifier letters are used in the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet[20]

- ꬶ : Used for the Teuthonista phonetic transcription system[21]

- G with diacritics: Ǵ ǵ Ǥ ǥ Ĝ ĝ Ǧ ǧ Ğ ğ Ģ ģ Ɠ ɠ Ġ ġ Ḡ ḡ Ꞡ ꞡ ᶃ

- ց : Armenian alphabet Tso

Ligatures and abbreviations

- ₲ : Paraguayan guaraní

Computing codes

| Preview | G | g | Ɡ | ɡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G | LATIN SMALL LETTER G | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SCRIPT G | LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G | ||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 71 | U+0047 | 103 | U+0067 | 42924 | U+A7AC | 609 | U+0261 |

| UTF-8 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 | 234 158 172 | EA 9E AC | 201 161 | C9 A1 |

| Numeric character reference | G | G | g | g | Ɡ | Ɡ | ɡ | ɡ |

| EBCDIC family | 199 | C7 | 135 | 87 | ||||

| ASCII 1 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Other representations

See also

- Carolingian G

- Hard and soft G

- Latin letters used in mathematics § Gg

References

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 1976.

- ^ Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2011-09-13). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444359855.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Romana

- ^ Everson, Michael; Sigurðsson, Baldur; Málstöð, Íslensk. «Sorting the letter ÞORN». Evertype. ISO CEN/TC304. Archived from the original on 2018-09-24. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

- ^ Hempl, George (1899). «The Origin of the Latin Letters G and Z». Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 30: 24–41. doi:10.2307/282560. JSTOR 282560.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (January 1895). «vɔt syr l alfabɛ» [Votes sur l’alphabet]. Le Maître Phonétique. 10 (1): 16–17. JSTOR 44707535.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (February–March 1900). «akt ɔfisjɛl» [Acte officiel]. Le Maître Phonétique. 15 (2/3): 20. JSTOR 44701257.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (July–December 1948). «desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl» [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. 26 (63) (90): 28–30. JSTOR 44705217.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1993). «Council actions on revisions of the IPA». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 32–34. doi:10.1017/S002510030000476X. S2CID 249420050.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1949). The Principles of the International Phonetic Association. Department of Phonetics, University College, London. Supplement to Le Maître Phonétique 91, January–June 1949. JSTOR i40200179.

- Reprinted in Journal of the International Phonetic Association 40 (3), December 2010, pp. 299–358, doi:10.1017/S0025100311000089.

- ^ Wells, John C. (6 November 2006). «Scenes from IPA history». John Wells’s phonetic blog. Department of Phonetics and Linguistics, University College London. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- ^ Wong, Kimberly; Wadee, Frempongma; Ellenblum, Gali; McCloskey, Michael (2 April 2018). «The Devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 44 (9): 1324–1335. doi:10.1037/xhp0000532. PMID 29608074. S2CID 4571477.

- ^ Dean, Signe (4 April 2018). «Most People Don’t Know What Lowercase ‘G’ Looks Like And We’re Not Even Kidding». Science Alert. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). «L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ a b Miller, Kirk; Ball, Martin (2020-07-11). «L2/20-116R: Expansion of the extIPA and VoQS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24.

- ^ a b Anderson, Deborah (2020-12-07). «L2/21-021: Reference doc numbers for L2/20-266R «Consolidated code chart of proposed phonetic characters» and IPA etc. code point and name changes» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-08.

- ^ a b Everson, Michael; West, Andrew (2020-10-05). «L2/20-268: Revised proposal to add ten characters for Middle English to the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24.

- ^ a b c Miller, Kirk; Ashby, Michael (2020-11-08). «L2/20-252R: Unicode request for IPA modifier-letters (a), pulmonic» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-30.

- ^ Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). «L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ Everson, Michael; Dicklberger, Alois; Pentzlin, Karl; Wandl-Vogt, Eveline (2011-06-02). «L2/11-202: Revised proposal to encode «Teuthonista» phonetic characters in the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

External links

This article is about the letter of the alphabet. For other uses, see G (disambiguation).

| G | |

|---|---|

| G g | |

| (See below, Typographic) | |

|

|

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic |

| Language of origin | Latin language |

| Phonetic usage |

|

| Unicode codepoint | U+0047, U+0067, U+0261 |

| Alphabetical position | 7 |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Time period | ~-300 to present |

| Descendants |

|

| Sisters |

|

| Transliteration equivalents | C |

| Variations | (See below, Typographic) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | gh, g(x) |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

G, or g, is the seventh letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is gee (pronounced ), plural gees.[1]

History

The letter ‘G’ was introduced in the Old Latin period as a variant of ‘C’ to distinguish voiced /ɡ/ from voiceless /k/.

The recorded originator of ‘G’ is freedman Spurius Carvilius Ruga, who added letter G to the teaching of the Roman alphabet during the 3rd century BC:[2] he was the first Roman to open a fee-paying school, around 230 BCE. At this time, ‘K’ had fallen out of favor, and ‘C’, which had formerly represented both /ɡ/ and /k/ before open vowels, had come to express /k/ in all environments.

Ruga’s positioning of ‘G’ shows that alphabetic order related to the letters’ values as Greek numerals was a concern even in the 3rd century BC. According to some records, the original seventh letter, ‘Z’, had been purged from the Latin alphabet somewhat earlier in the 3rd century BC by the Roman censor Appius Claudius, who found it distasteful and foreign.[3] Sampson (1985) suggests that: «Evidently the order of the alphabet was felt to be such a concrete thing that a new letter could be added in the middle only if a ‘space’ was created by the dropping of an old letter.»[4]

George Hempl proposed in 1899 that there never was such a «space» in the alphabet and that in fact ‘G’ was a direct descendant of zeta. Zeta took shapes like ⊏ in some of the Old Italic scripts; the development of the monumental form ‘G’ from this shape would be exactly parallel to the development of ‘C’ from gamma. He suggests that the pronunciation /k/ > /ɡ/ was due to contamination from the also similar-looking ‘K’.[5]

Eventually, both velar consonants /k/ and /ɡ/ developed palatalized allophones before front vowels; consequently in today’s Romance languages, ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ have different sound values depending on context (known as hard and soft C and hard and soft G). Because of French influence, English language orthography shares this feature.

Typographic variants

The modern lowercase ‘g’ has two typographic variants: the single-storey (sometimes opentail) ‘‘ and the double-storey (sometimes looptail) ‘

‘. The single-storey form derives from the majuscule (uppercase) form by raising the serif that distinguishes it from ‘c’ to the top of the loop, thus closing the loop and extending the vertical stroke downward and to the left. The double-storey form (

) had developed similarly, except that some ornate forms then extended the tail back to the right, and to the left again, forming a closed bowl or loop. The initial extension to the left was absorbed into the upper closed bowl. The double-storey version became popular when printing switched to «Roman type» because the tail was effectively shorter, making it possible to put more lines on a page. In the double-storey version, a small top stroke in the upper-right, often terminating in an orb shape, is called an «ear».

Generally, the two forms are complementary, but occasionally the difference has been exploited to provide contrast. In the International Phonetic Alphabet, opentail ⟨ɡ⟩ has always represented a voiced velar plosive, while ⟨⟩ was distinguished from ⟨ɡ⟩ and represented a voiced velar fricative from 1895 to 1900.[6][7] In 1948, the Council of the International Phonetic Association recognized ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨

⟩ as typographic equivalents,[8] and this decision was reaffirmed in 1993.[9] While the 1949 Principles of the International Phonetic Association recommended the use of ⟨

⟩ for a velar plosive and ⟨ɡ⟩ for an advanced one for languages where it is preferable to distinguish the two, such as Russian,[10] this practice never caught on.[11] The 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, the successor to the Principles, abandoned the recommendation and acknowledged both shapes as acceptable variants.[12]

Wong et al. (2018) found that native English speakers have little conscious awareness of the looptail ‘g’ ().[13][14] They write: «Despite being questioned repeatedly, and despite being informed directly that G has two lowercase print forms, nearly half of the participants failed to reveal any knowledge of the looptail ‘g’, and only 1 of the 38 participants was able to write looptail ‘g’ correctly.»

In Unicode, the two appearances are generally treated as glyph variants with no semantic difference. For applications where the single-storey variant must be distinguished (such as strict IPA in a typeface where the usual g character is double-storey), the character U+0261 ɡ LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G is available, as well as an upper case version, U+A7AC Ɡ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SCRIPT G.

Pronunciation and use

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) | Environment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | /x/ | |||

| Arabic | /ɡ/ | Latinization; corresponding to ⟨ق⟩ or ⟨ج⟩ in Arabic | ||

| Azeri | /ɟ/ | |||

| Catalan | /(d)ʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Danish | /ɡ/ | Word-initially | ||

| /k/ | Usually | |||

| Dutch | Standard | /ɣ/ | ||

| Southern dialects | /ɣ̟/ | |||

| Northern dialects | /χ/ | |||

| English | /dʒ/ | Before e, i, y (see exceptions below) | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i in «modern» loanwords from French | |||

| silent | Some words, initial <gn>, and word-finally before a consonant | |||

| Faroese | /j/ | soft, lenited; see Faroese phonology | ||

| /k/ | hard | |||

| /tʃ/ | soft | |||

| /v/ | after a, æ, á, e, o, ø and before u | |||

| /w/ | after ó, u, ú and before a, i, or u | |||

| silent | after a, æ, á, e, o, ø and before a | |||

| Fijian | /ŋ/ | |||

| French | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i, y | |||

| Galician | /ɡ/~/ħ/ | Usually | See Gheada for consonant variation | |

| /ʃ/ | Before e, i | obsolete spelling, replaced by the letter x | ||

| Greek | /ɡ/ | Usually | Latinization | |

| /ɟ/ | Before ai, e, i, oi, y | Latinization | ||

| Icelandic | /c/ | soft | ||

| /k/ | hard | |||

| /ɣ/ | hard, lenited; see Icelandic phonology | |||

| /j/ | soft, lenited | |||

| Irish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ɟ/ | After i or before e, i | |||

| Italian | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /dʒ/ | Before e, i | |||

| Mandarin | Standard | /k/ | Pinyin latinization | |

| Norman | /dʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Norwegian | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /j/ | Before ei, i, j, øy, y | |||

| Portuguese | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ʒ/ | Before e, i, y | |||

| Romanian | /dʒ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Romansh | /dʑ/ | Before e, i | ||

| /ɡ/ | Usually | |||

| Samoan | /ŋ/ | |||

| Scottish Gaelic | /k/ | Usually | ||

| /kʲ/ | After i or before e, i | |||

| Spanish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /x/ or /h/ | Before e, i, y | Variation between velar and glottal realizations depends on dialect | ||

| Swedish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /j/ | Before ä, e, i, ö, y | |||

| Turkish | /ɡ/ | Usually | ||

| /ɟ/ | Before e, i, ö, ü | |||

| Vietnamese | Standard | /ɣ/ | ||

| Northern | /z/ | Before i | ||

| Southern | /j/ | Before i |

English

In English, the letter appears either alone or in some digraphs. Alone, it represents

- a voiced velar plosive (/ɡ/ or «hard» ⟨g⟩), as in goose, gargoyle, and game;

- a voiced palato-alveolar affricate (/d͡ʒ/ or «soft» ⟨g⟩), predominates before ⟨i⟩ or ⟨e⟩, as in giant, ginger, and geology; or

- a voiced palato-alveolar sibilant (/ʒ/) in post-medieval loanwords from French, such as rouge, beige, genre (often), and margarine (rarely)

⟨g⟩ is predominantly soft before ⟨e⟩ (including the digraphs ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨oe⟩), ⟨i⟩, or ⟨y⟩, and hard otherwise. It is hard in those derivations from γυνή (gynḗ) meaning woman where initial-worded as such. Soft ⟨g⟩ is also used in many words that came into English from medieval church/academic use, French, Spanish, Italian or Portuguese – these tend to, in other ways in English, closely align to their Ancient Latin and Greek roots (such as fragile, logic or magic).

There remain widely used a few English words of non-Romance origin where ⟨g⟩ is hard followed by ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ (get, give, gift), and very few in which ⟨g⟩ is soft though followed by ⟨a⟩ such as gaol, which since the 20th century is almost always written as «jail».

The double consonant ⟨gg⟩ has the value /ɡ/ (hard ⟨g⟩) as in nugget, with very few exceptions: /d͡ʒ/ in exaggerate and veggies and dialectally /ɡd͡ʒ/ in suggest.

The digraph ⟨dg⟩ has the value /d͡ʒ/ (soft ⟨g⟩), as in badger. Non-digraph ⟨dg⟩ can also occur, in compounds like floodgate and headgear.

The digraph ⟨ng⟩ may represent:

- a velar nasal () as in length, singer

- the latter followed by hard ⟨g⟩ (/ŋɡ/) as in jungle, finger, longest

Non-digraph ⟨ng⟩ also occurs, with possible values

- /nɡ/ as in engulf, ungainly

- /nd͡ʒ/ as in sponge, angel

- /nʒ/ as in melange

The digraph ⟨gh⟩ (in many cases a replacement for the obsolete letter yogh, which took various values including /ɡ/, /ɣ/, /x/ and /j/) may represent:

- /ɡ/ as in ghost, aghast, burgher, spaghetti

- /f/ as in cough, laugh, roughage

- Ø (no sound) as in through, neighbor, night

- /x/ in ugh

- (rarely) /p/ in hiccough

- (rarely) /k/ in s’ghetti

Non-digraph ⟨gh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like foghorn, pigheaded

The digraph ⟨gn⟩ may represent:

- /n/ as in gnostic, deign, foreigner, signage

- /nj/ in loanwords like champignon, lasagna

Non-digraph ⟨gn⟩ also occurs, as in signature, agnostic

The trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ has the value /ŋ/ as in gingham or dinghy. Non-trigraph ⟨ngh⟩ also occurs, in compounds like stronghold and dunghill.

G is the tenth least frequently used letter in the English language (after Y, P, B, V, K, J, X, Q, and Z), with a frequency of about 2.02% in words.

Other languages

Most Romance languages and some Nordic languages also have two main pronunciations for ⟨g⟩, hard and soft. While the soft value of ⟨g⟩ varies in different Romance languages (/ʒ/ in French and Portuguese, [(d)ʒ] in Catalan, /d͡ʒ/ in Italian and Romanian, and /x/ in most dialects of Spanish), in all except Romanian and Italian, soft ⟨g⟩ has the same pronunciation as the ⟨j⟩.

In Italian and Romanian, ⟨gh⟩ is used to represent /ɡ/ before front vowels where ⟨g⟩ would otherwise represent a soft value. In Italian and French, ⟨gn⟩ is used to represent the palatal nasal /ɲ/, a sound somewhat similar to the ⟨ny⟩ in English canyon. In Italian, the trigraph ⟨gli⟩, when appearing before a vowel or as the article and pronoun gli, represents the palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/.

Other languages typically use ⟨g⟩ to represent /ɡ/ regardless of position.

Amongst European languages, Czech, Dutch, Estonian and Finnish are an exception as they do not have /ɡ/ in their native words. In Dutch, ⟨g⟩ represents a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ instead, a sound that does not occur in modern English, but there is a dialectal variation: many Netherlandic dialects use a voiceless fricative ([x] or [χ]) instead, and in southern dialects it may be palatal [ʝ]. Nevertheless, word-finally it is always voiceless in all dialects, including the standard Dutch of Belgium and the Netherlands. On the other hand, some dialects (like Amelands) may have a phonemic /ɡ/.

Faroese uses ⟨g⟩ to represent /dʒ/, in addition to /ɡ/, and also uses it to indicate a glide.

In Māori, ⟨g⟩ is used in the digraph ⟨ng⟩ which represents the velar nasal /ŋ/ and is pronounced like the ⟨ng⟩ in singer.

The Samoan and Fijian languages use the letter ⟨g⟩ by itself for /ŋ/.

In older Czech and Slovak orthographies, ⟨g⟩ was used to represent /j/, while /ɡ/ was written as ⟨ǧ⟩ (⟨g⟩ with caron).

The Azerbaijani Latin alphabet uses ⟨g⟩ exclusively for the «soft» sound, namely /ɟ/. The sound /ɡ/ is written as ⟨q⟩. This leads to unusual spellings of loanwords: qram ‘gram’, qrup ‘group’, qaraj ‘garage’, qallium ‘gallium’.

Ancestors, descendants and siblings

- 𐤂 : Semitic letter Gimel, from which the following symbols originally derive

- C c : Latin letter C, from which G derives

- Γ γ : Greek letter Gamma, from which C derives in turn

- ɡ : Latin letter script small G

- ᶢ : Modifier letter small script g is used for phonetic transcription[15]

- 𝼁 : Latin small letter reversed script g, an extension to IPA for disordered speech (extIPA)[16][17]

- ᵷ : Turned g

- 𝼂 : Latin letter small capital turned g, an extension to IPA for disordered speech (extIPA)[16][17]

- Г г : Cyrillic letter Ge

- Ȝ ȝ : Latin letter Yogh

- Ɣ ɣ : Latin letter Gamma

- Ᵹ ᵹ : Insular g

- ᫌ : Combining insular g, used in the Ormulum[18]

- Ꝿ ꝿ : Turned insular g

- Ꟑ ꟑ : Closed insular g, used in the Ormulum[18]

- ɢ : Latin letter small capital G, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular stop

- 𐞒 : Modifier letter small capital G, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- ʛ : Latin letter small capital G with hook, used in the International Phonetic Alphabet to represent a voiced uvular implosive

- 𐞔 : Modifier letter small capital G with hook, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- 𐞓 : Modifier letter small g with hook, used as a superscript IPA letter[19]

- ᴳ ᵍ : Modifier letters are used in the Uralic Phonetic Alphabet[20]

- ꬶ : Used for the Teuthonista phonetic transcription system[21]

- G with diacritics: Ǵ ǵ Ǥ ǥ Ĝ ĝ Ǧ ǧ Ğ ğ Ģ ģ Ɠ ɠ Ġ ġ Ḡ ḡ Ꞡ ꞡ ᶃ

- ց : Armenian alphabet Tso

Ligatures and abbreviations

- ₲ : Paraguayan guaraní

Computing codes

| Preview | G | g | Ɡ | ɡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G | LATIN SMALL LETTER G | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SCRIPT G | LATIN SMALL LETTER SCRIPT G | ||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 71 | U+0047 | 103 | U+0067 | 42924 | U+A7AC | 609 | U+0261 |

| UTF-8 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 | 234 158 172 | EA 9E AC | 201 161 | C9 A1 |

| Numeric character reference | G | G | g | g | Ɡ | Ɡ | ɡ | ɡ |

| EBCDIC family | 199 | C7 | 135 | 87 | ||||

| ASCII 1 | 71 | 47 | 103 | 67 |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Other representations

See also

- Carolingian G

- Hard and soft G

- Latin letters used in mathematics § Gg

References

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. 1976.

- ^ Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2011-09-13). The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444359855.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Romana

- ^ Everson, Michael; Sigurðsson, Baldur; Málstöð, Íslensk. «Sorting the letter ÞORN». Evertype. ISO CEN/TC304. Archived from the original on 2018-09-24. Retrieved 2018-11-01.

- ^ Hempl, George (1899). «The Origin of the Latin Letters G and Z». Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 30: 24–41. doi:10.2307/282560. JSTOR 282560.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (January 1895). «vɔt syr l alfabɛ» [Votes sur l’alphabet]. Le Maître Phonétique. 10 (1): 16–17. JSTOR 44707535.

- ^ Association phonétique internationale (February–March 1900). «akt ɔfisjɛl» [Acte officiel]. Le Maître Phonétique. 15 (2/3): 20. JSTOR 44701257.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (July–December 1948). «desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl» [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. 26 (63) (90): 28–30. JSTOR 44705217.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1993). «Council actions on revisions of the IPA». Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 32–34. doi:10.1017/S002510030000476X. S2CID 249420050.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1949). The Principles of the International Phonetic Association. Department of Phonetics, University College, London. Supplement to Le Maître Phonétique 91, January–June 1949. JSTOR i40200179.

- Reprinted in Journal of the International Phonetic Association 40 (3), December 2010, pp. 299–358, doi:10.1017/S0025100311000089.

- ^ Wells, John C. (6 November 2006). «Scenes from IPA history». John Wells’s phonetic blog. Department of Phonetics and Linguistics, University College London. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- ^ Wong, Kimberly; Wadee, Frempongma; Ellenblum, Gali; McCloskey, Michael (2 April 2018). «The Devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience». Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 44 (9): 1324–1335. doi:10.1037/xhp0000532. PMID 29608074. S2CID 4571477.

- ^ Dean, Signe (4 April 2018). «Most People Don’t Know What Lowercase ‘G’ Looks Like And We’re Not Even Kidding». Science Alert. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Constable, Peter (2004-04-19). «L2/04-132 Proposal to add additional phonetic characters to the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ a b Miller, Kirk; Ball, Martin (2020-07-11). «L2/20-116R: Expansion of the extIPA and VoQS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24.

- ^ a b Anderson, Deborah (2020-12-07). «L2/21-021: Reference doc numbers for L2/20-266R «Consolidated code chart of proposed phonetic characters» and IPA etc. code point and name changes» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-01-08.

- ^ a b Everson, Michael; West, Andrew (2020-10-05). «L2/20-268: Revised proposal to add ten characters for Middle English to the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24.

- ^ a b c Miller, Kirk; Ashby, Michael (2020-11-08). «L2/20-252R: Unicode request for IPA modifier-letters (a), pulmonic» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-07-30.

- ^ Everson, Michael; et al. (2002-03-20). «L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-19. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ Everson, Michael; Dicklberger, Alois; Pentzlin, Karl; Wandl-Vogt, Eveline (2011-06-02). «L2/11-202: Revised proposal to encode «Teuthonista» phonetic characters in the UCS» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

External links

Самое первое с чего стоит начинать изучение языка это английский алфавит (English Alphabet). Вам не обязательно учить его в порядке следования букв, как на уроках в школе. Но знать, как правильно читаются и пишутся буквы английского языка просто необходимо.

Современные реалии таковы, что с буквами английского алфавита мы сталкиваемся каждый день. Читать английские слова сегодня, может даже ребенок, но делают это многие люди, как правило, с ошибками в произношении.