Что такое целые числа

Здравствуйте, уважаемые читатели блога KtoNaNovenkogo.ru. Сегодня мы поговорим о ЦЕЛЫХ ЧИСЛАХ.

Это весьма обширное понятие из математики, с которым школьники сталкиваются уже в 5 классе. Быстрее разобраться помогут репетиторы по математике онлайн: объяснят тему понятным языком и дадут интерактивные задания для закрепления новых знаний.

Целые числа — это…

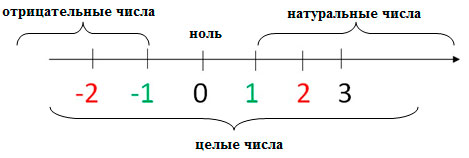

Целые числа – это все положительные, все отрицательные числа и ноль. Главное, чтобы они не содержали дробной части.

Согласно этому определению, к целым числам можно отнести:

-1256, -35, -9, 0, 14, 95, 2020

и так далее. Ведь у них нет дробной части. А вот числа:

0.5, 13.1319, ½, -¾, — 237.3

и так далее не могут считаться целыми, так как у них есть какие-то цифры после запятой или они являются дробью.

Все многообразие целых чисел называется множеством целых чисел. Это официальный математический термин. И обозначается он буквой Z.

В это множество входят и так называемые натуральные числа (это что?). Это все те, которые имеют положительное значение, но опять же без дробной части. Проще говоря, все числа, которые мы используем при счете. Например, 1, 2, 5, 10, 100 и так далее.

Множество натуральных чисел обознается буквой N. И зависимость его и множества целых чисел наглядно показана на следующем рисунке.

Отсюда можно сделать важный вывод:

Любое натуральное число автоматически является еще и целым. Но при этом далеко не каждое целое число является еще и натуральным.

А можно представить это и в таком варианте. Целые числа — это:

- Натуральные числа;

- Ноль;

- Отрицательные числа.

Каким бы определением вы не пользовались, главное, чтобы было все понятно.

История изучения целых чисел

Опять же эту историю нужно разделить на три части. Ведь изучение натуральных чисел, а также открытие нуля и отрицательных чисел происходило независимо друг от друга. Да еще и в разных странах.

Изучение натуральных чисел

Тут все максимально просто. Эти числа возникли, как только человеку понадобилось считать – будь то куски мяса или количество бревен для дома.

Более точное изучение натуральных чисел начинается в Древнем Египте и Древней Месопотамии, а это более 6 тысяч лет назад.

А современные математики опираются на то, что после себя оставил древнегреческий ученый Пифагор. Он как раз активно собирал египетские и вавилонские данные, а после отразил их в своих трудах.

Открытие нуля

Конечно, египтяне, вавилоняне и даже греки знали о существовании нуля. Но не считали его числом, а потому не пользовались им. Это, кстати, приносило им немало сложностей. Они порой часами решали задачки, которые нынешний школьник посчитает за минуту.

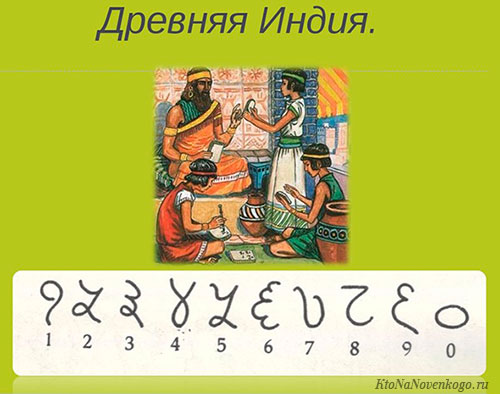

Но официально число ноль появилось в 5-м веке. И «изобрели» его в Индии. Дело в том, что у местных жителей всегда существовало убеждение, что «ничто – это тоже что-то». Даже понятие Нирвана, которое обозначает состояние небытие, зародилось именно в Индии.

Потому-то там и придумали символ, который обозначал бы «ничто». Авторами его стали математики Брахмагупта и Ариабхата.

Как видите, индийский символ нуля очень похож на современный. Ну, разве что приплюснут и больше напоминает правильную окружность. Форма выбрана не случайно. По индийским поверьям, ноль символизирует круговорот жизни и мироздания. Его еще называют «змея вечности».

Когда арабы завоевали часть Индии, они переняли все математические знания. А во время крестовых походов многое, в том числе и цифры, перекочевали в Европу. Хотя потребовалось еще несколько сотен лет, чтобы «ноль» стал неотъемлемой частью европейской науки.

Открытие отрицательных чисел

Отрицательные числа первыми начали изучать китайцы во 2 веке до нашей эры. Их использовали в торговле и называли «долгами». А обычные числа – «имуществом». А для записи отрицательных чисел использовали перевернутый вид.

А вот в Европе к ним очень долго относились пренебрежительно, считая «несуществующими» и «абсурдными». Лишь в 12 веке математик Леонардо Фибоначчи (автор знаменитого числового ряда) описал их в своей книге «Книга Абака».

В середине 16 века математик Михаил Штифель посвятил им целый раздел в своей книге «Полная арифметика».

Но признание они получили лишь в 17 веке, после того как известный Рене Декарт создал свою систему координат.

В ней он также использовал нуль, привязав к нему положительные и отрицательные числа. Одни находились справа от него, а другие – слева.

Свойства целых чисел

Всем целым числам свойственны следующие характеристики:

- Замкнутость. При математических действиях с целыми числами, за исключением деления, получаются только целые числа.

Если А и В – целые, то А+В=целое, А-В=целое и А*В=целое

- Ассоциативность. При сложении или умножении трех и более целых чисел их можно менять местами, и результат не изменится.

(А + В) + С = А + (В + С)

- Коммутативность. При перестановке мест слагаемых (множителей) – сумма (произведение) не меняется.

А + В = В + А, А * В = В * А

- Если ноль участвует в сложении или вычитании, то значение остается неизменным.

А + 0 = 0, А – 0 = 0

- Противоположность. При сложении одинаковых чисел с разными знаками, получается всегда ноль.

А + (-А) = 0

- Разность знаков. При умножении чисел с разными знаками, результат всегда отрицательный. Если знаки одинаковые, то результат всегда положительный.

А * А = АА, А * (-А) = -АА, (-А) * (-А) = АА

Добавим: точно такое же правило действует и при делении. Минус на минус дают плюс. А минус на плюс или плюс на минус всегда дают минус.

Вместо заключения

Мы уже рассказали, с каким трудом в нашу жизнь попали отрицательные числа. Но сегодня они широко используются не только в математике.

- География. Высоту гор измеряют положительными значениями, а вот глубину водоемов – отрицательными. А уровень моря является нулем.

- История. Понятие «наша эра» разделила историю на положительное летоисчисление и отрицательное. Все, что происходило, более 2 тысяч лет назад можно описать как «в минус 125 году» или «в -3000 лет». Хотя больше принято говорить «125 год до н.э» и «3000 лет до н.э.».

- Медицина. Для определения остроты зрения врачи используют понятия отрицательных и положительных диоптрий. Идеальное зрение – это ноль. Минус – близорукость (не видит вдалеке), а плюс – дальнозоркость (не видит вблизи).

- Физика. Есть такие понятия, как положительно и отрицательно заряженные частицы. Одни называются протонами, а другие – электронами.

Ну и, наконец, слова положительный и отрицательный используются и в более разговорном смысле, как синонимы хорошего и плохого.

Например, в книгах и фильмах обязательно есть положительные и отрицательные герои. Также и наши черты характера, эмоции и поступки можно разделить на эти две категории.

The double-struck symbol, often used to denote the set of all integers (see ℤ)

An integer is the number zero (0), a positive natural number (1, 2, 3, etc.) or a negative integer with a minus sign (−1, −2, −3, etc.).[1] The negative numbers are the additive inverses of the corresponding positive numbers.[2] In the language of mathematics, the set of integers is often denoted by the boldface Z or blackboard bold

The set of natural numbers

The integers form the smallest group and the smallest ring containing the natural numbers. In algebraic number theory, the integers are sometimes qualified as rational integers to distinguish them from the more general algebraic integers. In fact, (rational) integers are algebraic integers that are also rational numbers.

History

The word integer comes from the Latin integer meaning «whole» or (literally) «untouched», from in («not») plus tangere («to touch»). «Entire» derives from the same origin via the French word entier, which means both entire and integer.[10] Historically the term was used for a number that was a multiple of 1,[11][12] or to the whole part of a mixed number.[13][14] Only positive integers were considered, making the term synonymous with the natural numbers. The definition of integer expanded over time to include negative numbers as their usefulness was recognized.[15] For example Leonhard Euler in his 1765 Elements of Algebra defined integers to include both positive and negative numbers.[16] However, European mathematicians, for the most part, resisted the concept of negative numbers until the middle of the 19th century.[15]

The use of the letter Z to denote the set of integers comes from the German word Zahlen («number»)[4][5] and has been attributed to David Hilbert.[17] The earliest known use of the notation in a textbook occurs in Algébre written by the collective Nicolas Bourbaki, dating to 1947.[4][18] The notation was not adopted immediately, for example another textbook used the letter J[19] and a 1960 paper used Z to denote the non-negative integers.[20] But by 1961, Z was generally used by modern algebra texts to denote the positive and negative integers.[21]

The symbol

The whole numbers were synonymous with the integers up until the early 1950s.[24][25][26] In the late 1950s, as part of the New Math movement,[27] American elementary school teachers began teaching that «whole numbers» referred to the natural numbers, excluding negative numbers, while «integer» included the negative numbers.[28][29] «Whole number» remains ambiguous to the present day.[30]

Algebraic properties

Integers can be thought of as discrete, equally spaced points on an infinitely long number line. In the above, non-negative integers are shown in blue and negative integers in red.

Like the natural numbers,

The integers form a unital ring which is the most basic one, in the following sense: for any unital ring, there is a unique ring homomorphism from the integers into this ring. This universal property, namely to be an initial object in the category of rings, characterizes the ring

The following table lists some of the basic properties of addition and multiplication for any integers a, b and c:

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Closure: | a + b is an integer | a × b is an integer |

| Associativity: | a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c | a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c |

| Commutativity: | a + b = b + a | a × b = b × a |

| Existence of an identity element: | a + 0 = a | a × 1 = a |

| Existence of inverse elements: | a + (−a) = 0 | The only invertible integers (called units) are −1 and 1. |

| Distributivity: | a × (b + c) = (a × b) + (a × c) and (a + b) × c = (a × c) + (b × c) | |

| No zero divisors: | If a × b = 0, then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both) |

The first five properties listed above for addition say that

The first four properties listed above for multiplication say that

All the rules from the above property table (except for the last), when taken together, say that

The lack of zero divisors in the integers (last property in the table) means that the commutative ring

The lack of multiplicative inverses, which is equivalent to the fact that

Although ordinary division is not defined on

The above says that

Order-theoretic properties

:… −3 < −2 < −1 < 0 < 1 < 2 < 3 < …

An integer is positive if it is greater than zero, and negative if it is less than zero. Zero is defined as neither negative nor positive.

The ordering of integers is compatible with the algebraic operations in the following way:

- if a < b and c < d, then a + c < b + d

- if a < b and 0 < c, then ac < bc.

Thus it follows that

The integers are the only nontrivial totally ordered abelian group whose positive elements are well-ordered.[33] This is equivalent to the statement that any Noetherian valuation ring is either a field—or a discrete valuation ring.

Construction

Traditional development

In elementary school teaching, integers are often intuitively defined as the union of the (positive) natural numbers, zero, and the negations of the natural numbers. This can be formalized as follows.[34] First construct the set of natural numbers according to the Peano axioms, call this

The traditional arithmetic operations can then be defined on the integers in a piecewise fashion, for each of positive numbers, negative numbers, and zero. For example negation is defined as follows:

The traditional style of definition leads to many different cases (each arithmetic operation needs to be defined on each combination of types of integer) and makes it tedious to prove that integers obey the various laws of arithmetic.[35]

Equivalence classes of ordered pairs

Red points represent ordered pairs of natural numbers. Linked red points are equivalence classes representing the blue integers at the end of the line.

In modern set-theoretic mathematics, a more abstract construction[36][37] allowing one to define arithmetical operations without any case distinction is often used instead.[38] The integers can thus be formally constructed as the equivalence classes of ordered pairs of natural numbers (a,b).[39]

The intuition is that (a,b) stands for the result of subtracting b from a.[39] To confirm our expectation that 1 − 2 and 4 − 5 denote the same number, we define an equivalence relation ~ on these pairs with the following rule:

precisely when

Addition and multiplication of integers can be defined in terms of the equivalent operations on the natural numbers;[39] by using [(a,b)] to denote the equivalence class having (a,b) as a member, one has:

The negation (or additive inverse) of an integer is obtained by reversing the order of the pair:

Hence subtraction can be defined as the addition of the additive inverse:

The standard ordering on the integers is given by:

if and only if

It is easily verified that these definitions are independent of the choice of representatives of the equivalence classes.

Every equivalence class has a unique member that is of the form (n,0) or (0,n) (or both at once). The natural number n is identified with the class [(n,0)] (i.e., the natural numbers are embedded into the integers by map sending n to [(n,0)]), and the class [(0,n)] is denoted −n (this covers all remaining classes, and gives the class [(0,0)] a second time since −0 = 0.

Thus, [(a,b)] is denoted by

If the natural numbers are identified with the corresponding integers (using the embedding mentioned above), this convention creates no ambiguity.

This notation recovers the familiar representation of the integers as {…, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, …} .

Some examples are:

Other approaches

In theoretical computer science, other approaches for the construction of integers are used by automated theorem provers and term rewrite engines.

Integers are represented as algebraic terms built using a few basic operations (e.g., zero, succ, pred) and, possibly, using natural numbers, which are assumed to be already constructed (using, say, the Peano approach).

There exist at least ten such constructions of signed integers.[40] These constructions differ in several ways: the number of basic operations used for the construction, the number (usually, between 0 and 2) and the types of arguments accepted by these operations; the presence or absence of natural numbers as arguments of some of these operations, and the fact that these operations are free constructors or not, i.e., that the same integer can be represented using only one or many algebraic terms.

The technique for the construction of integers presented in the previous section corresponds to the particular case where there is a single basic operation pair

Computer science

An integer is often a primitive data type in computer languages. However, integer data types can only represent a subset of all integers, since practical computers are of finite capacity. Also, in the common two’s complement representation, the inherent definition of sign distinguishes between «negative» and «non-negative» rather than «negative, positive, and 0». (It is, however, certainly possible for a computer to determine whether an integer value is truly positive.) Fixed length integer approximation data types (or subsets) are denoted int or Integer in several programming languages (such as Algol68, C, Java, Delphi, etc.).

Variable-length representations of integers, such as bignums, can store any integer that fits in the computer’s memory. Other integer data types are implemented with a fixed size, usually a number of bits which is a power of 2 (4, 8, 16, etc.) or a memorable number of decimal digits (e.g., 9 or 10).

Cardinality

The cardinality of the set of integers is equal to ℵ0 (aleph-null). This is readily demonstrated by the construction of a bijection, that is, a function that is injective and surjective from

with graph (set of the pairs

- {… (−4,8), (−3,6), (−2,4), (−1,2), (0,0), (1,1), (2,3), (3,5), …}.

Its inverse function is defined by

with graph

- {(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, −1), (3, 2), (4, −2), (5, −3), …}.

See also

- Canonical factorization of a positive integer

- Hyperinteger

- Integer complexity

- Integer lattice

- Integer part

- Integer sequence

- Integer-valued function

- Mathematical symbols

- Parity (mathematics)

- Profinite integer

Complex

|

|

Footnotes

- ^ More precisely, each system is embedded in the next, isomorphically mapped to an subset.[6] The commonly-assumed set-theoretic containment may be obtained by constructing the reals, discarding any earlier constructions, and defining the other sets as subsets of the reals.[7] Such a convention is «a matter of choice», yet not.[8]

References

- ^ Science and Technology Encyclopedia. University of Chicago Press. September 2000. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-226-74267-0.

- ^ «Integers: Introduction to the concept, with activities comparing temperatures and money. | Unit 1». OER Commons.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Integer». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Miller, Jeff (29 August 2010). «Earliest Uses of Symbols of Number Theory». Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ a b Peter Jephson Cameron (1998). Introduction to Algebra. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-850195-4. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Partee, Barbara H.; Meulen, Alice ter; Wall, Robert E. (30 April 1990). Mathematical Methods in Linguistics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-90-277-2245-4.

The natural numbers are not themselves a subset of this set-theoretic representation of the integers. Rather, the set of all integers contains a subset consisting of the positive integers and zero which is isomorphic to the set of natural numbers.

- ^ Wohlgemuth, Andrew (10 June 2014). Introduction to Proof in Abstract Mathematics. Courier Corporation. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-486-14168-8.

- ^ Polkinghorne, John (19 May 2011). Meaning in Mathematics. OUP Oxford. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-162189-5.

- ^ Prep, Kaplan Test (4 June 2019). GMAT Complete 2020: The Ultimate in Comprehensive Self-Study for GMAT. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5062-4844-8.

- ^ Evans, Nick (1995). «A-Quantifiers and Scope». In Bach, Emmon W. (ed.). Quantification in Natural Languages. Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7923-3352-4.

- ^ Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopædia Metropolitana. B. Fellowes. p. 537.

An integer is a multiple of unity

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 367

- ^ Pisano, Leonardo; Boncompagni, Baldassarre (transliteration) (1202). Incipit liber Abbaci compositus to Lionardo filio Bonaccii Pisano in year Mccij [The Book of Calculation] (Manuscript) (in Latin). Translated by Sigler, Laurence E. Museo Galileo. p. 30.

Nam rupti uel fracti semper ponendi sunt post integra, quamuis prius integra quam rupti pronuntiari debeant.

[And the fractions are always put after the whole, thus first the integer is written, and then the fraction] - ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 83

- ^ a b Martinez, Alberto (2014). Negative Math. Princeton University Press. pp. 80–109.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1771). Vollstandige Anleitung Zur Algebra [Complete Introduction to Algebra] (in German). Vol. 1. p. 10.

Alle diese Zahlen, so wohl positive als negative, führen den bekannten Nahmen der gantzen Zahlen, welche also entweder größer oder kleiner sind als nichts. Man nennt dieselbe gantze Zahlen, um sie von den gebrochenen, und noch vielerley andern Zahlen, wovon unten gehandelt werden wird, zu unterscheiden.

[All these numbers, both positive and negative, are called whole numbers, which are either greater or lesser than nothing. We call them whole numbers, to distinguish them from fractions, and from several other kinds of numbers of which we shall hereafter speak.] - ^ The University of Leeds Review. Vol. 31–32. University of Leeds. 1989. p. 46.

Incidentally, Z comes from «Zahl»: the notation was created by Hilbert.

- ^ Bourbaki, Nicolas (1951). Algèbre, Chapter 1 (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Hermann. p. 27.

Le symétrisé de N se note Z; ses éléments sont appelés entiers rationnels.

[The group of differences of N is denoted by Z; its elements are called the rational integers.] - ^ Birkhoff, Garrett (1948). Lattice Theory (Revised ed.). American Mathematical Society. p. 63.

the set J of all integers

- ^ Society, Canadian Mathematical (1960). Canadian Journal of Mathematics. Canadian Mathematical Society. p. 374.

Consider the set Z of non-negative integers

- ^ Bezuszka, Stanley (1961). Contemporary Progress in Mathematics: Teacher Supplement [to] Part 1 and Part 2. Boston College. p. 69.

Modern Algebra texts generally designate the set of integers by the capital letter Z.

- ^ Keith Pledger and Dave Wilkins, «Edexcel AS and A Level Modular Mathematics: Core Mathematics 1» Pearson 2008

- ^ LK Turner, FJ BUdden, D Knighton, «Advanced Mathematics», Book 2, Longman 1975.

- ^ Mathews, George Ballard (1892). Theory of Numbers. Deighton, Bell and Company. p. 2.

- ^ Betz, William (1934). Junior Mathematics for Today. Ginn.

The whole numbers, or integers, when arranged in their natural order, such as 1, 2, 3, are called consecutive integers.

- ^ Peck, Lyman C. (1950). Elements of Algebra. McGraw-Hill. p. 3.

The numbers which so arise are called positive whole numbers, or positive integers.

- ^ Hayden, Robert (1981). A history of the «new math» movement in the United States (PhD). Iowa State University. p. 145. doi:10.31274/rtd-180813-5631.

A much more influential force in bringing news of the «new math» to high school teachers and administrators was the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).

- ^ The Growth of Mathematical Ideas, Grades K-12: 24th Yearbook. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. 1959. p. 14. ISBN 9780608166186.

- ^ Deans, Edwina (1963). Elementary School Mathematics: New Directions. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education. p. 42.

- ^ «entry: whole number». The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins.

- ^ «Integer | mathematics». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Lang, Serge (1993). Algebra (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-201-55540-0.

- ^ Warner, Seth (2012). Modern Algebra. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Corporation. Theorem 20.14, p. 185. ISBN 978-0-486-13709-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015..

- ^ Mendelson, Elliott (1985). Number systems and the foundations of analysis. Malabar, Fla. : R.E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-89874-818-5.

- ^ Mendelson, Elliott (2008). Number Systems and the Foundations of Analysis. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-486-45792-5. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016..

- ^ Ivorra Castillo: Álgebra

- ^ Kramer, Jürg; von Pippich, Anna-Maria (2017). From Natural Numbers to Quaternions (1st ed.). Switzerland: Springer Cham. pp. 78–81. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69429-0. ISBN 978-3-319-69427-6.

- ^ Frobisher, Len (1999). Learning to Teach Number: A Handbook for Students and Teachers in the Primary School. The Stanley Thornes Teaching Primary Maths Series. Nelson Thornes. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7487-3515-0. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016..

- ^ a b c Campbell, Howard E. (1970). The structure of arithmetic. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-390-16895-5.

- ^ Garavel, Hubert (2017). On the Most Suitable Axiomatization of Signed Integers. Post-proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Algebraic Development Techniques (WADT’2016). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10644. Springer. pp. 120–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72044-9_9. ISBN 978-3-319-72043-2. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

Sources

- Bell, E.T. (1986). Men of Mathematics. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46400-0.)

- Herstein, I.N. (1975). Topics in Algebra (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-01090-1.

- Mac Lane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1999). Algebra (3rd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

- A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland (1771). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh.

External links

Look up integer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Integer», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- The Positive Integers – divisor tables and numeral representation tools

- On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences cf OEIS

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Integer». MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Integer on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

The double-struck symbol, often used to denote the set of all integers (see ℤ)

An integer is the number zero (0), a positive natural number (1, 2, 3, etc.) or a negative integer with a minus sign (−1, −2, −3, etc.).[1] The negative numbers are the additive inverses of the corresponding positive numbers.[2] In the language of mathematics, the set of integers is often denoted by the boldface Z or blackboard bold

The set of natural numbers

The integers form the smallest group and the smallest ring containing the natural numbers. In algebraic number theory, the integers are sometimes qualified as rational integers to distinguish them from the more general algebraic integers. In fact, (rational) integers are algebraic integers that are also rational numbers.

History

The word integer comes from the Latin integer meaning «whole» or (literally) «untouched», from in («not») plus tangere («to touch»). «Entire» derives from the same origin via the French word entier, which means both entire and integer.[10] Historically the term was used for a number that was a multiple of 1,[11][12] or to the whole part of a mixed number.[13][14] Only positive integers were considered, making the term synonymous with the natural numbers. The definition of integer expanded over time to include negative numbers as their usefulness was recognized.[15] For example Leonhard Euler in his 1765 Elements of Algebra defined integers to include both positive and negative numbers.[16] However, European mathematicians, for the most part, resisted the concept of negative numbers until the middle of the 19th century.[15]

The use of the letter Z to denote the set of integers comes from the German word Zahlen («number»)[4][5] and has been attributed to David Hilbert.[17] The earliest known use of the notation in a textbook occurs in Algébre written by the collective Nicolas Bourbaki, dating to 1947.[4][18] The notation was not adopted immediately, for example another textbook used the letter J[19] and a 1960 paper used Z to denote the non-negative integers.[20] But by 1961, Z was generally used by modern algebra texts to denote the positive and negative integers.[21]

The symbol

The whole numbers were synonymous with the integers up until the early 1950s.[24][25][26] In the late 1950s, as part of the New Math movement,[27] American elementary school teachers began teaching that «whole numbers» referred to the natural numbers, excluding negative numbers, while «integer» included the negative numbers.[28][29] «Whole number» remains ambiguous to the present day.[30]

Algebraic properties

Integers can be thought of as discrete, equally spaced points on an infinitely long number line. In the above, non-negative integers are shown in blue and negative integers in red.

Like the natural numbers,

The integers form a unital ring which is the most basic one, in the following sense: for any unital ring, there is a unique ring homomorphism from the integers into this ring. This universal property, namely to be an initial object in the category of rings, characterizes the ring

The following table lists some of the basic properties of addition and multiplication for any integers a, b and c:

| Addition | Multiplication | |

|---|---|---|

| Closure: | a + b is an integer | a × b is an integer |

| Associativity: | a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c | a × (b × c) = (a × b) × c |

| Commutativity: | a + b = b + a | a × b = b × a |

| Existence of an identity element: | a + 0 = a | a × 1 = a |

| Existence of inverse elements: | a + (−a) = 0 | The only invertible integers (called units) are −1 and 1. |

| Distributivity: | a × (b + c) = (a × b) + (a × c) and (a + b) × c = (a × c) + (b × c) | |

| No zero divisors: | If a × b = 0, then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both) |

The first five properties listed above for addition say that

The first four properties listed above for multiplication say that

All the rules from the above property table (except for the last), when taken together, say that

The lack of zero divisors in the integers (last property in the table) means that the commutative ring

The lack of multiplicative inverses, which is equivalent to the fact that

Although ordinary division is not defined on

The above says that

Order-theoretic properties

:… −3 < −2 < −1 < 0 < 1 < 2 < 3 < …

An integer is positive if it is greater than zero, and negative if it is less than zero. Zero is defined as neither negative nor positive.

The ordering of integers is compatible with the algebraic operations in the following way:

- if a < b and c < d, then a + c < b + d

- if a < b and 0 < c, then ac < bc.

Thus it follows that

The integers are the only nontrivial totally ordered abelian group whose positive elements are well-ordered.[33] This is equivalent to the statement that any Noetherian valuation ring is either a field—or a discrete valuation ring.

Construction

Traditional development

In elementary school teaching, integers are often intuitively defined as the union of the (positive) natural numbers, zero, and the negations of the natural numbers. This can be formalized as follows.[34] First construct the set of natural numbers according to the Peano axioms, call this

The traditional arithmetic operations can then be defined on the integers in a piecewise fashion, for each of positive numbers, negative numbers, and zero. For example negation is defined as follows:

The traditional style of definition leads to many different cases (each arithmetic operation needs to be defined on each combination of types of integer) and makes it tedious to prove that integers obey the various laws of arithmetic.[35]

Equivalence classes of ordered pairs

Red points represent ordered pairs of natural numbers. Linked red points are equivalence classes representing the blue integers at the end of the line.

In modern set-theoretic mathematics, a more abstract construction[36][37] allowing one to define arithmetical operations without any case distinction is often used instead.[38] The integers can thus be formally constructed as the equivalence classes of ordered pairs of natural numbers (a,b).[39]

The intuition is that (a,b) stands for the result of subtracting b from a.[39] To confirm our expectation that 1 − 2 and 4 − 5 denote the same number, we define an equivalence relation ~ on these pairs with the following rule:

precisely when

Addition and multiplication of integers can be defined in terms of the equivalent operations on the natural numbers;[39] by using [(a,b)] to denote the equivalence class having (a,b) as a member, one has:

The negation (or additive inverse) of an integer is obtained by reversing the order of the pair:

Hence subtraction can be defined as the addition of the additive inverse:

The standard ordering on the integers is given by:

if and only if

It is easily verified that these definitions are independent of the choice of representatives of the equivalence classes.

Every equivalence class has a unique member that is of the form (n,0) or (0,n) (or both at once). The natural number n is identified with the class [(n,0)] (i.e., the natural numbers are embedded into the integers by map sending n to [(n,0)]), and the class [(0,n)] is denoted −n (this covers all remaining classes, and gives the class [(0,0)] a second time since −0 = 0.

Thus, [(a,b)] is denoted by

If the natural numbers are identified with the corresponding integers (using the embedding mentioned above), this convention creates no ambiguity.

This notation recovers the familiar representation of the integers as {…, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, …} .

Some examples are:

Other approaches

In theoretical computer science, other approaches for the construction of integers are used by automated theorem provers and term rewrite engines.

Integers are represented as algebraic terms built using a few basic operations (e.g., zero, succ, pred) and, possibly, using natural numbers, which are assumed to be already constructed (using, say, the Peano approach).

There exist at least ten such constructions of signed integers.[40] These constructions differ in several ways: the number of basic operations used for the construction, the number (usually, between 0 and 2) and the types of arguments accepted by these operations; the presence or absence of natural numbers as arguments of some of these operations, and the fact that these operations are free constructors or not, i.e., that the same integer can be represented using only one or many algebraic terms.

The technique for the construction of integers presented in the previous section corresponds to the particular case where there is a single basic operation pair

Computer science

An integer is often a primitive data type in computer languages. However, integer data types can only represent a subset of all integers, since practical computers are of finite capacity. Also, in the common two’s complement representation, the inherent definition of sign distinguishes between «negative» and «non-negative» rather than «negative, positive, and 0». (It is, however, certainly possible for a computer to determine whether an integer value is truly positive.) Fixed length integer approximation data types (or subsets) are denoted int or Integer in several programming languages (such as Algol68, C, Java, Delphi, etc.).

Variable-length representations of integers, such as bignums, can store any integer that fits in the computer’s memory. Other integer data types are implemented with a fixed size, usually a number of bits which is a power of 2 (4, 8, 16, etc.) or a memorable number of decimal digits (e.g., 9 or 10).

Cardinality

The cardinality of the set of integers is equal to ℵ0 (aleph-null). This is readily demonstrated by the construction of a bijection, that is, a function that is injective and surjective from

with graph (set of the pairs

- {… (−4,8), (−3,6), (−2,4), (−1,2), (0,0), (1,1), (2,3), (3,5), …}.

Its inverse function is defined by

with graph

- {(0, 0), (1, 1), (2, −1), (3, 2), (4, −2), (5, −3), …}.

See also

- Canonical factorization of a positive integer

- Hyperinteger

- Integer complexity

- Integer lattice

- Integer part

- Integer sequence

- Integer-valued function

- Mathematical symbols

- Parity (mathematics)

- Profinite integer

Complex

|

|

Footnotes

- ^ More precisely, each system is embedded in the next, isomorphically mapped to an subset.[6] The commonly-assumed set-theoretic containment may be obtained by constructing the reals, discarding any earlier constructions, and defining the other sets as subsets of the reals.[7] Such a convention is «a matter of choice», yet not.[8]

References

- ^ Science and Technology Encyclopedia. University of Chicago Press. September 2000. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-226-74267-0.

- ^ «Integers: Introduction to the concept, with activities comparing temperatures and money. | Unit 1». OER Commons.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Integer». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Miller, Jeff (29 August 2010). «Earliest Uses of Symbols of Number Theory». Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ a b Peter Jephson Cameron (1998). Introduction to Algebra. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-850195-4. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Partee, Barbara H.; Meulen, Alice ter; Wall, Robert E. (30 April 1990). Mathematical Methods in Linguistics. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 78–82. ISBN 978-90-277-2245-4.

The natural numbers are not themselves a subset of this set-theoretic representation of the integers. Rather, the set of all integers contains a subset consisting of the positive integers and zero which is isomorphic to the set of natural numbers.

- ^ Wohlgemuth, Andrew (10 June 2014). Introduction to Proof in Abstract Mathematics. Courier Corporation. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-486-14168-8.

- ^ Polkinghorne, John (19 May 2011). Meaning in Mathematics. OUP Oxford. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-19-162189-5.

- ^ Prep, Kaplan Test (4 June 2019). GMAT Complete 2020: The Ultimate in Comprehensive Self-Study for GMAT. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5062-4844-8.

- ^ Evans, Nick (1995). «A-Quantifiers and Scope». In Bach, Emmon W. (ed.). Quantification in Natural Languages. Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7923-3352-4.

- ^ Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopædia Metropolitana. B. Fellowes. p. 537.

An integer is a multiple of unity

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 367

- ^ Pisano, Leonardo; Boncompagni, Baldassarre (transliteration) (1202). Incipit liber Abbaci compositus to Lionardo filio Bonaccii Pisano in year Mccij [The Book of Calculation] (Manuscript) (in Latin). Translated by Sigler, Laurence E. Museo Galileo. p. 30.

Nam rupti uel fracti semper ponendi sunt post integra, quamuis prius integra quam rupti pronuntiari debeant.

[And the fractions are always put after the whole, thus first the integer is written, and then the fraction] - ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica 1771, p. 83

- ^ a b Martinez, Alberto (2014). Negative Math. Princeton University Press. pp. 80–109.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard (1771). Vollstandige Anleitung Zur Algebra [Complete Introduction to Algebra] (in German). Vol. 1. p. 10.

Alle diese Zahlen, so wohl positive als negative, führen den bekannten Nahmen der gantzen Zahlen, welche also entweder größer oder kleiner sind als nichts. Man nennt dieselbe gantze Zahlen, um sie von den gebrochenen, und noch vielerley andern Zahlen, wovon unten gehandelt werden wird, zu unterscheiden.

[All these numbers, both positive and negative, are called whole numbers, which are either greater or lesser than nothing. We call them whole numbers, to distinguish them from fractions, and from several other kinds of numbers of which we shall hereafter speak.] - ^ The University of Leeds Review. Vol. 31–32. University of Leeds. 1989. p. 46.

Incidentally, Z comes from «Zahl»: the notation was created by Hilbert.

- ^ Bourbaki, Nicolas (1951). Algèbre, Chapter 1 (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Hermann. p. 27.

Le symétrisé de N se note Z; ses éléments sont appelés entiers rationnels.

[The group of differences of N is denoted by Z; its elements are called the rational integers.] - ^ Birkhoff, Garrett (1948). Lattice Theory (Revised ed.). American Mathematical Society. p. 63.

the set J of all integers

- ^ Society, Canadian Mathematical (1960). Canadian Journal of Mathematics. Canadian Mathematical Society. p. 374.

Consider the set Z of non-negative integers

- ^ Bezuszka, Stanley (1961). Contemporary Progress in Mathematics: Teacher Supplement [to] Part 1 and Part 2. Boston College. p. 69.

Modern Algebra texts generally designate the set of integers by the capital letter Z.

- ^ Keith Pledger and Dave Wilkins, «Edexcel AS and A Level Modular Mathematics: Core Mathematics 1» Pearson 2008

- ^ LK Turner, FJ BUdden, D Knighton, «Advanced Mathematics», Book 2, Longman 1975.

- ^ Mathews, George Ballard (1892). Theory of Numbers. Deighton, Bell and Company. p. 2.

- ^ Betz, William (1934). Junior Mathematics for Today. Ginn.

The whole numbers, or integers, when arranged in their natural order, such as 1, 2, 3, are called consecutive integers.

- ^ Peck, Lyman C. (1950). Elements of Algebra. McGraw-Hill. p. 3.

The numbers which so arise are called positive whole numbers, or positive integers.

- ^ Hayden, Robert (1981). A history of the «new math» movement in the United States (PhD). Iowa State University. p. 145. doi:10.31274/rtd-180813-5631.

A much more influential force in bringing news of the «new math» to high school teachers and administrators was the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM).

- ^ The Growth of Mathematical Ideas, Grades K-12: 24th Yearbook. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. 1959. p. 14. ISBN 9780608166186.

- ^ Deans, Edwina (1963). Elementary School Mathematics: New Directions. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education. p. 42.

- ^ «entry: whole number». The American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins.

- ^ «Integer | mathematics». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Lang, Serge (1993). Algebra (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-201-55540-0.

- ^ Warner, Seth (2012). Modern Algebra. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Corporation. Theorem 20.14, p. 185. ISBN 978-0-486-13709-4. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015..

- ^ Mendelson, Elliott (1985). Number systems and the foundations of analysis. Malabar, Fla. : R.E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-89874-818-5.

- ^ Mendelson, Elliott (2008). Number Systems and the Foundations of Analysis. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-486-45792-5. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016..

- ^ Ivorra Castillo: Álgebra

- ^ Kramer, Jürg; von Pippich, Anna-Maria (2017). From Natural Numbers to Quaternions (1st ed.). Switzerland: Springer Cham. pp. 78–81. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69429-0. ISBN 978-3-319-69427-6.

- ^ Frobisher, Len (1999). Learning to Teach Number: A Handbook for Students and Teachers in the Primary School. The Stanley Thornes Teaching Primary Maths Series. Nelson Thornes. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7487-3515-0. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016..

- ^ a b c Campbell, Howard E. (1970). The structure of arithmetic. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-390-16895-5.

- ^ Garavel, Hubert (2017). On the Most Suitable Axiomatization of Signed Integers. Post-proceedings of the 23rd International Workshop on Algebraic Development Techniques (WADT’2016). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 10644. Springer. pp. 120–134. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72044-9_9. ISBN 978-3-319-72043-2. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

Sources

- Bell, E.T. (1986). Men of Mathematics. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-46400-0.)

- Herstein, I.N. (1975). Topics in Algebra (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-01090-1.

- Mac Lane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1999). Algebra (3rd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-1646-2.

- A Society of Gentlemen in Scotland (1771). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edinburgh.

External links

Look up integer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- «Integer», Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- The Positive Integers – divisor tables and numeral representation tools

- On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences cf OEIS

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Integer». MathWorld.

This article incorporates material from Integer on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Целые числа — это множество чисел, которые состоят из натуральных чисел, целых отрицательных чисел и нуля. Отрицательные целые числа — это целые числа со знаком «минус». Они всегда меньше нуля. Примеры целых отрицательных чисел: -944, -1287, -1, -19.

Как найти целые числа?

Вещественное число является целым, если его десятичное представление не содержит дробной части (но может содержать знак). Примеры вещественных чисел: Числа 142857; 0; −273 являются целыми. Числа 5½; 9,75 не являются целыми.

Как называются целые положительные числа?

Целые неположительные и целые неотрицательные числа

Определение. Все целые положительные числа вместе с числом нуль называют целыми неотрицательными числами.

Как писать целые числа?

Целые числа — это натуральные числа, числа, противоположные им, и число нуль. Множество целых чисел обозначается буквой Z .

Как называются целые числа?

мадина и. Целые числа это — множество натуральных чисел (1,2,3,4,…n); чисел, противоположных натуральным (-1,-2,-3,-4,… -n) и ноль (0). Иными словами, это числа, не имеющие дробную часть.

Как выглядит целые числа?

Целые числа — это множество чисел, которые состоят из натуральных чисел, целых отрицательных чисел и нуля. Отрицательные целые числа — это целые числа со знаком «минус». Они всегда меньше нуля. Примеры целых отрицательных чисел: -944, -1287, -1, -19.

Как находить целые числа в дробях?

Если известно сколько составляет часть от целого, то по известной части можно «восстановить» целое. Для этого пользуемся правилом нахождения целого (числа) по его дроби (части). Чтобы найти число по его части, выраженной дробью, нужно данное число разделить на дробь.

Какие числа принадлежат Z?

Натуральные числа, противоположные им и ноль называют целыми числами. Множество целых чисел обозначают символом Z.

Какие существуют множества чисел?

Множества чисел. Законы действий над различными числами

- Множество натуральных чисел

- Множество целых чисел

- Множество рациональных чисел

- Множество действительных чисел

- Множество комплексных чисел

Какое число является положительным?

Числа со знаком плюс называют положительными, а со знаком минус – отрицательными. … Положительные числа – это числа, которые больше нуля, а отрицательные числа – это числа, меньшие нуля. Таким образом, нуль как бы отделяет положительные числа от отрицательных.

Как правильно писать многозначные числа?

Оно звучит так «Чтобы прочитать многозначное число, его разбивают на классы, отсчитывая справа по три цифры, затем считают, сколько единиц каждого класса, начиная с высшего». Повторим это правило. Например: записано число 253 400. В нем 253 единицы класса тысяч и 400 единиц класса единиц.

Как целые числа отличаются от натуральных?

Натуральные числа, это часть понятия «целые числа» -только положительные числа. А целые числа, это и ноль, и отрицательные числа.

Как правильно писать цифры в тексте?

Цифра или слово: общее правило

- Для упрощения восприятия текста двузначные и многозначные числа пишутся цифрами.

- А числа от одного до девяти пишем словом, если они не в именительном падеже. …

- А в именительном падеже можно и так, и так:

- В начале предложения, пункта списка пишется слово.

5 июн. 2019 г.

Какие бывают числа?

Числа

- Натуральные числа N.

- Целые числа Z.

- Рациональные числа Q.

- Иррациональные числа I.

- Действительные числа R.

- Комплексные числа C.

Какие числа называют целыми 6 класс?

Натуральные числа, числа им противоположные и число 0 называют целыми числами.

Какие числа относятся к натуральным?

naturalis «естественный») — числа, возникающие естественным образом при счёте (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 и так далее…). Последовательность всех натуральных чисел, расположенных в порядке возрастания, называется натуральным рядом. . Отрицательные и нецелые числа к натуральным не относят.

Интересные материалы:

Как вырезать и вставить объект в фотошопе?

Как вырезать объект в GIMP?

Как вырезать отверстие в металлочерепице?

Как выровнять бумагу после гуаши?

Как высчитать процент износа оборудования?

Как выселить другую семью в Симс 4?

Как высказать свою точку зрения?

Как выставить смарт часы?

Как выставить цену номенклатуры в 1с?

Как высушить грецкие орехи в скорлупе?

![{displaystyle [(a,b)]+[(c,d)]:=[(a+c,b+d)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ada63de55374aa09013be65caa1c33aa0164ecb3)

![{displaystyle [(a,b)]cdot [(c,d)]:=[(ac+bd,ad+bc)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6ea8c51ad5f2968fcf5788eb220d4f4463b28588)

![{displaystyle -[(a,b)]:=[(b,a)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/951d0171ed1edf705e70392352f3d07b94ed4c74)

![{displaystyle [(a,b)]-[(c,d)]:=[(a+d,b+c)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ef8af489c7cff40fe4cfe66d5a706837fc0a6df6)

![{displaystyle [(a,b)]<[(c,d)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5f5d9d3f2ef39e8cf90692589f0b97945454536)

![{begin{aligned}0&=[(0,0)]&=[(1,1)]&=cdots &&=[(k,k)]\1&=[(1,0)]&=[(2,1)]&=cdots &&=[(k+1,k)]\-1&=[(0,1)]&=[(1,2)]&=cdots &&=[(k,k+1)]\2&=[(2,0)]&=[(3,1)]&=cdots &&=[(k+2,k)]\-2&=[(0,2)]&=[(1,3)]&=cdots &&=[(k,k+2)].end{aligned}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/325c6a83a84e4fe08bac03e453f674b1ff83eac1)